Abstract

Background

Resection of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) offers a chance of cure, but recurrence is common and survival is often limited. The clinical and pathological characteristics of long-term survivors have not been well studied.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 212 patients who underwent partial hepatectomy for HCC with curative intent from 1992 to 2006. Fifty patients who survived beyond 10 years were compared with 109 patients who died of recurrence within 10 years.

Results

Multivariate analysis showed that tumors <5 cm (odds ratio [OR] 2.3, p = 0.04), solitary tumors (OR 3.2, p = 0.01), and absence of vascular invasion (OR 2.3, p = 0.04) were independently associated with actual 10-year survival. However, more than 20% of long-term survivors also possessed established poor prognostic factors, including α-fetoprotein >1000 ng/mL, unfavorable serum inflammatory indices, tumor size >10 cm, microvascular invasion, poor tumor differentiation, cirrhosis, and metabolic syndrome. None of the 10-year survivors had an R1 resection. While 77% of the short-term survivors developed recurrence within 2 years, 42% of the 10-year survivors developed recurrence during their decade of follow-up, although most of the recurrences among 10-year survivors were intrahepatic and amenable to further treatment. Among patients who survived beyond 10 years, 42% remained alive without recurrence.

Conclusions

In this largest Western series of actual 10-year survivors after HCC resection, almost one in four patients survived over a decade, even though nearly half of this subset had developed recurrence. While many well-known variables were associated with a poor outcome, only a positive microscopic margin precluded long-term survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide and its incidence has been increasing.1,2 While HCC resection may be curative for selected patients, there has been a paucity of reports on actual long-term survivors. Many studies have reported recurrence rates as high as 70–80% within 5 years of resection, with an overall survival rate of approximately 40–50% at 5 years.3–7 Most outcome studies present actuarial survival based on the Kaplan–Meier method, which often overestimates actual long-term survival. A systematic review of 303 actual 10-year survivors worldwide revealed that only 7% survived 10 years after resection, whereas some studies within the review have quoted actuarial survival as high as 27%.8 Of the few reports that have documented long-term survivors, the largest series in the US had only 28 actual 10-year survivors.9–13

Resection of HCC has been the mainstay of curative therapy, but only 20–30% of all patients presenting with HCC are eligible for resection.14 Liver transplantation is not a realistic option for many patients given the limited donor pool and stringent Milan criteria.3 Thus, eligibility for resection has broadened over the years, and resection is utilized when there is adequate liver remnant and metabolic function.15,16 In many centers, patients with large tumors, multinodular disease, and vascular invasion, among other well-established high-risk factors, still undergo resection for a chance of cure.4–7,17 Nomograms have been developed to calculate the probability of survival, but they should be interpreted with caution since they are inherently limited by being derived from actuarial data. Whether these risk factors preclude actual 10-year survival has not been well studied.

In this study, we present the largest Western experience of actual 10-year survivors. We aim to characterize the clinicopathological variables that are associated with long-term survival, with an emphasis on evaluating the impact of established high-risk factors on the potential curative intent of HCC resection.

Methods

Patients

With approval of the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, we retrospectively analyzed 212 consecutive patients who underwent resection of HCC with curative intent from 1992 to 2006. Of these patients, 13 (6%) died within 3 months of operation, 28 (13%) died of other or unknown causes, and 12 (6%) patients were lost to follow-up. These 53 patients were excluded in order to study cancer-related death, comparing those who died of recurrence within a decade with those who survived beyond 10 years (Fig. 1). All patients in this study had complete macroscopic resection. Patients with fibrolamellar HCC or combined HCC and cholangiocarcinoma were excluded.

Patients were considered for resection if they had resectable tumors, adequate liver remnant and metabolic function, and absence of any distant metastasis. Preoperative portal vein embolization was utilized if there was a concern of small future liver remnant, while preoperative artery embolization was utilized to stabilize patients with tumor rupture or to downstage tumor for subsequent resection. Involvement of the diaphragm or adrenal gland that could be resected with a gross negative margin was not considered a contraindication. Tumors with invasion of hepatic or portal vein branches were also resected in selected cases. Most patients were Child–Pugh class A, but selected patients with class B also underwent partial hepatectomy. Treatments were discussed at a weekly multidisciplinary disease management team conference. For follow-up, patients were evaluated in clinic within 2 weeks postoperatively, and then followed every 3 months in the first several years and then every 6 months thereafter. Patients were evaluated with history and physical examination, α-fetoprotein (AFP) and liver function tests, and serial abdominal computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans during surveillance. In addition, our institutional Cancer Registry conducts annual follow-up with our patients and their providers to obtain updated disease status.

Clinicopathologic Variables

We evaluated age at resection, gender, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, Child–Pugh classification, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, underlying liver diseases, and metabolic disorders. Patients with any three of the following risk factors met the criteria for metabolic syndrome: body mass index ≥25, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.18 We also obtained preoperative levels of AFP and serum inflammatory markers, which included neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), prognostic nutritional index (PNI), and aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI), as previously calculated and dichotomized.19–24

Operative details included the number of segments resected, concomitant extrahepatic tumor, tumor rupture, and operative blood loss. Major hepatectomy was defined as resection of 3 or more Couinaud segments. Pathological data included the number of tumors, largest tumor diameter, vascular invasion, differentiation, fibrosis and cirrhosis, steatosis as per the Kleiner–Brunt histologic scoring system, and margin status. The presence of microscopic tumor cells at the resection margin was considered an R1 resection. Recurrence and survival details were also documented.

Statistics

Continuous variables were presented as median and range, while categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage, and were compared using the Wilcoxon rank test and Fisher’s exact test, respectively. Multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression, and Kaplan–Meier curves were generated for overall and recurrence-free survival. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.2.2 (cran.r-project.org). A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

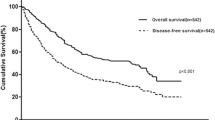

Of 212 patients who underwent curative-intent resection for HCC, the median overall survival was 4.2 years [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.3–5.5] (Fig. 2a) and median recurrence-free survival was 1.6 years (95% CI 1.1–2.4) (Fig. 2b). The median length of follow-up was 13 years for survivors. After excluding patients who died within 3 months of operation, died without recurrence, or were lost to follow-up, 159 patients were used for comparative analyses.

Clinicopathological variables of 50 patients who survived over a decade versus 109 patients who died of recurrence within a decade are shown in Table 1. By univariate analysis, 10-year survivors were significantly younger, female, had higher levels of LMR and PNI, had less operative blood loss, had tumors that were smaller, solitary, and lacked vascular invasion, and had an R0 resection.

However, poor prognostic factors were identified in more than 20% of actual 10-year survivors. This included preoperative levels of AFP> 1000 ng/mL, NLR > 2.81, PLR ≥ 190, LMR ≤ 3.77, and APRI ≥ 0.62. Other poor prognostic factors found among the 50 long-term survivors included 5 (10%) patients with preoperative tumor rupture, 2 (4%) patients with concomitantly resected extrahepatic disease, 16 (32%) patients with tumor size >10 cm, 8 (16%) patients with multiple nodules, 14 (28%) patients with vascular invasion, 16 (32%) patients with poor differentiation, 12 (24%) patients with cirrhosis, and 15 (30%) patients with steatosis. Among 14 long-term survivors with vascular invasion, 1 patient had hepatic vein thrombus known preoperatively and 13 had microvascular invasion identified only on pathology. In contrast, 17 (16%) short-term survivors had macrovascular invasion on preoperative scans. None of the long-term survivors had Child–Pugh class B liver function, combined hepatitis B and C, hemochromatosis, or an R1 resection.

In multivariate analysis, as shown in Table 2, factors independently associated with actual 10-year survival included smaller tumor size <5 cm [odds ratio (OR) 2.3, p = 0.04], solitary tumor (OR 3.2, p = 0.01), and absence of any vascular involvement (OR 2.3, p = 0.04).

Recurrence details of the two comparative groups are shown in Table 3. Almost half (n = 21, 42%) of the 10-year survivors developed recurrence within 10 years, whereas the majority (n = 84, 77%) of the short-term survivors developed recurrence within the first 2 years. Patients with early recurrence within 2 years had significantly shorter survival after recurrence compared with those who developed recurrence after 2 years (p = 0.003) [Fig. 3]. In 43 patients who recurred after 2 years, 18 (42%) survived beyond 10 years, indicating indolent tumor biology. The three patients who developed recurrence after 10 years had cirrhosis identified on initial hepatectomy and died shortly after recurrence. While the majority of recurrences occurred intrahepatically for both long-term (n = 17, 81%) and short-term (n = 70, 64%) survivors, one-third (n = 39, 36%) of short-term survivors developed extrahepatic recurrence.

Among the long-term survivors, 21 were alive without recurrence. Another 21 patients had developed recurrence, of whom 11 remained alive with disease, and 10 died of disease after 10 years. Eight patients died of other causes as they had no evidence of disease during their last visit. While recurrence was generally associated with worse outcomes, 18 patients with recurrence within 10 years of resection survived beyond 10 years. The predominant treatments of these patients at the onset of recurrence are shown in Table 3. While selected patients with recurrence were eligible for second resection or salvage liver transplant, half of the patients with recurrence were treated with percutaneous interventions, including transarterial embolization and ethanol ablation. Of the three long-term survivors who had extrahepatic recurrence, two underwent resection of their metastasis (one in the peripancreatic lymph nodes and one in the lung) within 10 years, and one patient with cirrhosis developed multifocal HCC 15 years later, in the liver and adrenal, and died within a few months of recurrence.

Discussion

In this study, we compared 50 patients with HCC who survived beyond 10 years with 109 patients who died of disease within a decade. Known high-risk pathological variables such as large tumor size, multiple nodules or satellites, and vascular invasion were associated with worse outcome, similar to other studies.4–7 However, these risk factors did not preclude long-term survival. Eight patients (16%) with multiple nodules or satellites survived 10 years. None of these eight patients had macrovascular invasion, although two patients had microvascular invasion. Their median tumor size was 12 cm. Despite having these high-risk factors, these patients survived over 10 years. Furthermore, AFP levels >1000 ng/mL, preoperative tumor rupture, local extrahepatic disease, poor tumor differentiation, cirrhosis, and steatosis did not significantly distinguish short-term survivors from long-term survivors. These findings were consistent with some, but not all, prior studies.8,19–27 This is likely due to the heterogeneity of HCC patients, and thus it is difficult to identify prognostic factors that are widely applicable. In addition, serum inflammatory indices, which have not been previously studied in actual 10-year survivors, were not associated with outcome, in our analysis, when they were dichotomized. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that there are few absolute exceptions to having long-term survival when complete resection with adequate future liver remnant can be achieved.

Having a positive microscopic margin precluded 10-year survival in our experience. For patients with positive margins, only 1 of 28 patients in one study and 1 of 10 patients in another study survived beyond a decade, and one patient received adjuvant transarterial chemotherapy.13,28 Larger studies are needed to better characterize the impact of positive microscopic margins on long-term survival as only 11 patients had an R1 resection in our study. Additional therapies, such as re-resection or ablation to achieve negative margins, may confer improved survival similar to a study on hilar cholangiocarcinoma.29 The ability to achieve any margin clearance in HCC, even a 2-mm free margin, has yielded similar overall survival to those with larger clearance.30 Thus, while margin clearance may seem to be a result of surgical technique, it is likely to be a surrogate marker of tumor aggressiveness, similar to our findings with resection of colorectal liver metastasis.31 Diffuse infiltrative HCCs are less amenable to an R0 resection and have significantly worse outcomes compared with discrete, nodular HCCs.32,33

Short-term survivors had significantly shorter time to recurrence, with the majority (77%) developing recurrence within 2 years. Early recurrence is likely secondary to metastasis from primary tumors through microvascular invasion, which is often associated with larger tumors and those with multiple nodules and satellites.34–36 On the other hand, late recurrence is likely secondary to multicentric carcinogenesis that stems from cirrhosis.34–36 In our series, 48 (55%) patients with early recurrence within 2 years had microvascular invasion, and 23 (26%) had pathologic cirrhosis. However, all three of the patients who developed recurrence after 10 years had cirrhosis and lacked vascular invasion on their initial hepatectomy. It is likely these late recurrences were second primary tumors from their underlying cirrhosis rather than true recurrence. This is a stark contrast from patients with colorectal liver metastasis with no underlying liver disease, in which most patients (97%) who survived 10 years appeared to be cured.37 Thus, lifelong follow-up should be considered for patients after resection of HCC, especially in those with cirrhosis.

Of all centers that have documented actual 10-year survivors, only centers in China and Japan have published large series to date.9–12 It is important to note that the underlying liver diseases that promote HCC development vary in different parts of the world. The majority of patients with HCC in China have hepatitis B, while hepatitis C is more common in Japan, and whereas relatively more patients in the US have metabolic disorders.38–40 These varying liver diseases, along with their underlying genetic dispositions and tumor behavior, may lead to disparate surgical outcomes.41,42 Approximately 25% of our patients had pathologic cirrhosis, compared with 50–80% found in Asian countries where HCC is predominantly secondary to chronic viral hepatitis.4,7,43 Thus, findings in our 10-year survivors are likely more applicable to other Western institutions.

Conclusions

Actual 10-year survival after resection of HCC was associated with having a small, solitary tumor without vascular invasion. However, more than 20% of the 10-year survivors possessed many of the established poor prognostic factors. Only R1 resection precluded actual 10-year survival in our study. Our findings suggest that resection should be offered when tumor is resectable for a chance of long-term survival despite having individual poor prognostic factors, and that long-term surveillance should be considered, especially in those with cirrhosis.

References

Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1245–55.

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108.

Chapman WC, Klintmalm G, Hemming A, et al. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in North America: can hepatic resection still be justified? J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220(4):628–37.

Shim JH, Jun MJ, Han S, et al. Prognostic nomograms for prediction of recurrence and survival after curative liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2015;261(5):939–46.

Li Y, Xia Y, Li J, et al. Prognostic nomograms for pre- and postoperative predictions of long-term survival for patients who underwent liver resection for huge hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(5):962–74.

Ang SF, Ng ES, Li H, et al. The Singapore Liver Cancer Recurrence (SLICER) score for relapse prediction in patients with surgically resected hepatocellular carcinoma. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0118658.

Yang P, Qiu J, Li J, et al. Nomograms for pre- and postoperative prediction of long-term survival for patients who underwent hepatectomy for multiple hepatocellular carcinomas. Ann Surg. 2016;263(4):778–86.

Gluer AM, Cocco N, Laurence JM, et al. Systematic review of actual 10-year survival following resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2012;14(5):285–90.

Shimada K, Sano T, Sakamoto Y, Kosuge T. A long-term follow-up and management study of hepatocellular carcinoma patients surviving for 10 years or longer after curative hepatectomy. Cancer. 2005;104(9):1939–47.

Zhou XD, Tang ZY, Yang BH, et al. Experience of 1000 patients who underwent hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;91(8):1479–86.

Wu KT, Wang CC, Lu LG, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical study of long-term survival and choice of treatment modalities. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(23):3649–57.

Zhou XD, Tang ZY, Ma ZC, et al. Twenty-year survivors after resection for hepatocellular carcinoma-analysis of 53 cases. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135(8):1067–72.

Franssen B, Jibara G, Tabrizian P, Schwartz ME, Roayaie S. Actual 10-year survival following hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxf.). 2014;16(9):830–5.

She WH, Chok K. Strategies to increase the resectability of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(18):2147–54.

Ribero D, Curley SA, Imamura H, et al. Selection for resection of hepatocellular carcinoma and surgical strategy: indications for resection, evaluation of liver function, portal vein embolization, and resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(4):986–92.

Dhir M, Melin AA, Douaiher J, et al. A review and update of treatment options and controversies in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2016;263(6):1112–25.

Cho CS, Gonen M, Shia J, et al. A novel prognostic nomogram is more accurate than conventional staging systems for predicting survival after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(2):281–91.

Piscaglia F, Svegliati-Baroni G, Barchetti A, et al. Clinical patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a multicenter prospective study. Hepatology. 2016;63(3):827–38.

Mano Y, Shirabe K, Yamashita Y, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a predictor of survival after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective analysis. Ann Surg. 2013;258(2):301–5.

Spolverato G, Maqsood H, Kim Y, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratio in patients after resection for hepato-pancreatico-biliary malignancies. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111(7):868–74.

Wu SJ, Lin YX, Ye H, Li FY, Xiong XZ, Cheng NS. Lymphocyte to monocyte ratio and prognostic nutritional index predict survival outcomes of hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma patients after curative hepatectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114(2):202–10.

Chan AW, Chan SL, Wong GL, et al. Prognostic nutritional index (PNI) predicts tumor recurrence of very early/early stage hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(13):4138–48.

Shen SL, Fu SJ, Chen B, et al. Preoperative aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio is an independent prognostic factor for hepatitis B-induced hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(12):3802–9.

Ji F, Liang Y, Fu SJ, et al. A novel and accurate predictor of survival for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection: the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) combined with the aspartate aminotransferase/platelet count ratio index (APRI). BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):137.

Aoki T, Kokudo N, Matsuyama Y, et al. Prognostic impact of spontaneous tumor rupture in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: an analysis of 1160 cases from a nationwide survey. Ann Surg. 2014;259(3):532–42.

Uchiyama H, Minagawa R, Itoh S, et al. Favorable outcomes of hepatectomy for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma: retrospective analysis of primary R0-hepatectomized patients. Anticancer Res. 2016;36(1):379–85.

Nishio T, Hatano E, Sakurai T, et al. Impact of hepatic steatosis on disease-free survival in patients with non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatic resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(7):2226–34.

Poon RT, Ng IO, Fan ST, et al. Clinicopathologic features of long-term survivors and disease-free survivors after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a study of a prospective cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(12):3037–44.

Ribero D, Amisano M, Lo Tesoriere R, Rosso S, Ferrero A, Capussotti L. Additional resection of an intraoperative margin-positive proximal bile duct improves survival in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2011;254(5):776–81; discussion 781-773

Chen JH, Wei CK, Lee CH, Chang CM, Hsu TW, Yin WY. The safety and adequacy of resection on hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 10 cm: a retrospective study over 10 years. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2015;4(2):193–9.

Sadot E, Groot Koerkamp B, Leal JN, et al. Resection margin and survival in 2368 patients undergoing hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: surgical technique or biologic surrogate? Ann Surg. 2015;262(3):476–85; discussion 483-475.

Yopp AC, Mokdad A, Zhu H, et al. Infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma: natural history and comparison with multifocal, nodular hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22 Suppl 3:S1075–82.

Kneuertz PJ, Demirjian A, Firoozmand A, et al. Diffuse infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma: assessment of presentation, treatment, and outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(9):2897–907.

Hirokawa F, Hayashi M, Asakuma M, Shimizu T, Inoue Y, Uchiyama K. Risk factors and patterns of early recurrence after curative hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg Oncol. 2016;25(1):24–9.

Yamamoto Y, Ikoma H, Morimura R, et al. Optimal duration of the early and late recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(4):1207–15.

Huang ZY, Liang BY, Xiong M, et al. Long-term outcomes of repeat hepatic resection in patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma and analysis of recurrent types and their prognosis: a single-center experience in China. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(8):2515–25.

Tomlinson JS, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo RP, et al. Actual 10-year survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases defines cure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(29):4575–80.

Mittal S, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: consider the population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47 Suppl:S2–6.

El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: where are we? Where do we go? Hepatology. 2014;60(5):1767–75.

Makarova-Rusher OV, Altekruse SF, McNeel TS, et al. Population attributable fractions of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 2016;122(11):1757–65.

Utsunomiya T, Shimada M, Kudo M, et al. A comparison of the surgical outcomes among patients with HBV-positive, HCV-positive, and non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma: a nationwide study of 11,950 patients. Ann Surg. 2015;261(3):513–20.

Schulze K, Imbeaud S, Letouze E, et al. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):505–11.

Pawlik TM, Esnaola NF, Vauthey JN. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: similar long-term results despite geographic variations. Liver Transpl. 2004;10(2 Suppl 1):S74–80.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH/NCI P30 CA008748 Cancer Center Support Grant and NIH/NCAT UL1TR00457 Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical Center and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Conflict of interest

Jian Zheng, Deborah Kuk, Mithat Gönen, Vinod P. Balachandran, T. Peter Kingham, Peter J. Allen, Michael I. D’Angelica, William R. Jarnagin, and Ronald P. DeMatteo report no conflict of interest in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, J., Kuk, D., Gönen, M. et al. Actual 10-Year Survivors After Resection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 24, 1358–1366 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5713-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5713-2