Abstract

Background

Studies focusing on the impact of obesity on survival in endometrial cancer (EC) have reported controversial results and few data exist on the impact of obesity on recurrence rate and recurrence-free survival (RFS). The aim of this study was to assess the impact of obesity on surgical staging and RFS in EC according to the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) risk groups.

Methods

Data of 729 women with EC who received primary surgical treatment between January 2000 and December 2012 were abstracted from a multicenter database. RFS distributions according to body mass index (BMI) in each ESMO risk group were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Survival was evaluated using the log-rank test, and the Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine influence of multiple variables.

Results

Distribution of the 729 women with EC according to BMI was BMI < 30 (n = 442; 60.6 %), 30 ≤ BMI < 35 (n = 146; 20 %) and BMI ≥ 35 (n = 141; 19.4 %). Nodal staging was less likely to be performed in women with a BMI ≥ 35 (72 %) than for those with a BMI < 30 (90 %) (p < 0.0001). With a median follow-up of 27 months (interquartile range 13–52), the 3-year RFS was 84.5 %. BMI had no impact on RFS in obese women in the low-/intermediate-risk groups, but a BMI ≥ 35 was independently correlated to a poorer RFS (hazard ratio 12.5; 95 % confidence interval 3.1–51.3) for women in the high-risk group.

Conclusion

Severe obesity negatively impacts RFS in women with high-risk EC, underlining the importance of complete surgical staging and adapted adjuvant therapies in this subgroup of women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Obesity is a well-known risk factor for endometrial cancer (EC);1,2 women with a body mass index (BMI) > 30 have a relative risk of death from EC of 2.53 compared with women of normal weight.3 This increased risk particularly concerns type I ECs, which are associated with long duration, unopposed estrogenic stimulation, and emerge in a setting of endometrial hyperplasia.4

In Europe, surgical treatment of presumed early-stage EC is based on the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines, according to the presumed risk of recurrence. For women with low- or intermediate-risk EC, a total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is recommended. Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy is recommended for women of high-risk EC.5 Because of associated comorbidities or technical difficulties related to obesity, surgeons are sometimes reluctant to perform complete surgical staging, including lymphadenectomy. Moreover, difficulties are also encountered to adapt adjuvant treatment, either for radiotherapy6 or chemotherapy,7 with a potential impact on survival. However, studies focusing on the impact of obesity on survival in EC have reported controversial results,2,7–20 and few data exist on the impact of obesity on recurrence rate and recurrence-free survival (RFS) according to the ESMO risk groups.

Hence, the purpose of this multicenter study was to assess the impact of obesity on surgical staging and RFS in EC according to the ESMO risk groups.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Data of all women who received primary surgical treatment between January 2000 and December 2012 were abstracted from five institutions in France with maintained EC databases (Tenon University Hospital, Reims University Hospital, Dijon Cancer Center, Lille University Hospital, and Creteil University Hospital), and also from the Senti-Endo trial.21 All women had given written informed consent to participate in the study. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the French College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (CEROG 2014-GYN-020).

Clinical and pathologic variables included patient’s age, BMI, surgical procedure, 2009 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, final pathological analysis [histological type and grade, depth of myometrial invasion, lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) status] and adjuvant therapies. BMI was defined as weight (kg) divided by squared height (m2), both measured at the time of diagnosis, and expressed in kg/m2. Normal bodyweight was defined as a BMI < 25 kg/m2, obesity was defined as a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, and severe obesity was defined as a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2).22

Histological staging and grading was performed according to the 2009 FIGO classification system23 on the basis of the final evaluation of the pathological specimen. The risk of recurrence was defined according to the ESMO guidelines. Histological type I corresponds to endometrioid cancer, whatever the histological grade. Histological type 2 corresponds to clear-cell carcinomas, serous carcinomas, and carcinosarcomas. The three risk groups of EC are defined as follows: low-risk (type 1 EC FIGO stage IA grade 1 or 2); intermediate-risk (type 1 EC, FIGO stage IA grade 3, or FIGO stage IB grade 1 or 2); high-risk (type 1 EC, FIGO stage IB grade 3, and type 2 EC).5

Treatment and Follow-up

All women underwent primary surgical treatment, including at least total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Until 2010, systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy was recommended, and para-aortic lymphadenectomy was only performed in case of high-risk EC or metastatic pelvic lymph node. Since the publication of French guidelines in 2010,24 lymphadenectomy was no longer recommended for women with low-/intermediate-risk EC. Women with early-stage EC who were enrolled in the Senti-Endo trial21 from July 2007 to August 2009 underwent a pelvic sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy25 with systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy. When the pelvic SLN was found to be metastatic at intraoperative histology or after final histology, a para-aortic lymphadenectomy was recommended. Adjuvant therapy was administered according to multidisciplinary committees based on French guidelines.24

According to French guidelines,24 frequency of clinical follow-up was every 3–4 months for the first 2 years, and then with a 6-month interval until 5 years and every year thereafter. Further imaging investigations were carried out if clinically indicated.

Disease recurrence was diagnosed either by biopsy or imaging studies and defined as a relapse without differentiating between their local or distant nature. RFS was calculated in months from the date of surgery to recurrence. Any woman not presenting for scheduled follow-up visits was contacted.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was based on the Student’s t test or ANOVA test, as appropriate, for continuous variables, and the χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to denote significant differences.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the survival distribution, and comparisons of survival were made using the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to account for the influence of multiple variables.

Data were managed with an Excel database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and analyzed using R 3.0.1 software, available online.

Results

Characteristics of the Whole Population

A total of 729 women were included in the study. The median BMI was 28 kg/m2 [interquartile range (IQR) 24–33] and the distribution was as follows: BMI < 30 (n = 442; 60.6 %), 30 ≤ BMI < 35 (n = 146; 20 %) and BMI ≥ 35 (n = 141; 19.4 %) (Table 1).

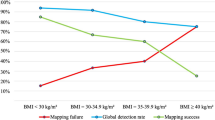

Women with severe obesity were more likely to be younger (63 years of age for women with a BMI ≥ 35 vs. 65.5 years for those with a BMI < 30; p = 0.000873). More women with severe obesity had grade 1 and type 1 EC compared with non-obese women (61 vs. 45 % and 96 vs. 84 %, respectively). A greater proportion of women with severe obesity met the criteria for the low risk of recurrence group (56 % with a BMI ≥ 35 vs. 40 % for a BMI < 30), while thinner women had high-risk EC (23 % for a BMI < 30 vs. 12 % for a BMI ≥ 35). However, depth of myometrial invasion, LVSI status, and nodal involvement did not differ according to BMI. All women underwent at least a hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Women with a higher BMI were less likely to undergo nodal staging—72 % of women with a BMI ≥ 35 compared with 90 % in women with a BMI < 30 (p < 0.0001). Among the 39 women with a BMI ≥ 35 who did not undergo lymphadenectomy, nodal staging was recommended in three cases (7.7 %) and was not performed due to severe comorbidity. Among the women who underwent nodal staging, no difference in the number of lymph nodes removed was found according to BMI.

Characteristics of Obese Women According to ESMO Risk of Recurrence Groups

The number of obese women with low-, intermediate-, or high-risk EC was 137/287 (48 %), 99/287 (34 %), and 51/287 (18 %), respectively. In the low- and intermediate-risk groups, a lower proportion of women with a BMI ≥ 35 had nodal staging compared with women with a BMI < 35 (p < 0.05). In the high-risk group, age, comorbidities (diabetes and hypertension), and histological and therapeutic characteristics did not differ according to BMI (Table 2).

Recurrence Rate and Recurrence-Free Survival

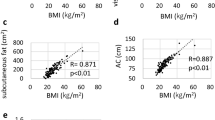

With a median follow-up of 27 months (IQR 13–52), 103 women (13.9 %) experienced a recurrence and 72 (9.7 %) died. The 3-year RFS was 84.5 %. We found no difference in RFS according to BMI subgroups (Fig. 1).

BMI had no impact on RFS in obese women in the low- and intermediate-risk groups.

In the high-risk group of obese women, a lower RFS was found for those with a BMI ≥ 35 compared with those with a BMI < 35 (Fig. 2). Among women in the high-risk group, multivariate analysis, including BMI (<35 or ≥35), age (<65 years or ≥65 years), histological type, LVSI status, adjuvant therapies (vaginal brachytherapy, external beam radiotherapy, and chemotherapy), and nodal staging, showed that a BMI ≥ 35 was independently correlated to a poorer RFS (hazard ratio [HR] 12.5; 95 % confidence interval [CI] 3.1–51.3).

Discussion

Our results show that women with severe obesity are more likely to have low-/intermediate- risk Ecs, with similar RFS than non-obese women. In contrast, among obese women with high-risk EC, those with severe obesity had a lower RFS.

When considering the whole population of obese women with EC, regardless of the distribution according to the ESMO risk groups, no relation was observed between obesity and decrease in RFS. These data are in agreement with those of a review of 12 studies evaluating the relation between obesity and survival of patients with EC26 reporting no impact of obesity either on progression-free 7–9,13,17 or disease-specific survival.15,16 Similarly, in a study of 1,070 women with EC treated within the Medical Research Council A Study in the Treatment of Endometrial Cancer randomized trial with a median follow-up of 34.3 months, Crosbie et al. found no influence of obesity on RFS.27 More recently, in a study including 2,596 women with EC, Gunderson et al. found no association between obesity and disease-specific mortality;28 however, no attempt was made to evaluate the impact of obesity on RFS according to ESMO risk groups.

In the current study, when analyzing RFS in obese patients according to ESMO risk groups, we noted that patients with severe obesity were more likely to have low-grade tumors (1–2), type 1 EC, and limited myometrial infiltration corresponding to low/intermediate ESMO risk groups. Although obese patients had a lower rate of lymphadenectomy, no difference in RFS in patients with ESMO low-/intermediate-risk groups was observed between severely obese and obese patients. These results are in full agreement with those of the meta-analysis of May et al. underlining the absence of impact of lymphadenectomy on RFS.29 This absence of difference in RFS can be explained by the low incidence of lymph node metastases in this subgroup of patients. Moreover, patients with low/intermediate risk represented approximately three-quarters of the population in our study, as in previous reports, and this explains why no difference in survival according to BMI was found, taking into account the whole population.

For patients with severe obesity in the ESMO high-risk group, a decrease in RFS was observed. This is partly in accordance with Arem et al. who found that patients with poorly differentiated tumors had an EC-specific mortality HR of 1.39 (95 % CI 1.04–1.85) per five-unit BMI increase, whereas no differences were detected for well-differentiated or moderately-differentiated tumors.18 Using multivariable analysis, severe obesity emerged as an independent risk factor of decreased RFS. The difference in RFS was not related to epidemiological characteristics as no difference in co-morbidities such as hypertension and diabetes was noted between patients with a BMI < 35 and those with a higher BMI. Differences in survival in obese patients can be explained by various histological parameters. There is a trend for a higher incidence of LVSI in severely obese patients. Indeed, a recent study demonstrated that the recurrence rate for the high-risk group was 25.9 % in the case of negative LVSI and 45.1 % for those with positive LVSI.30 In addition, in a study collecting data of ten cohorts and 14 case–control studies from the Epidemiology of Endometrial Cancer Consortium, with a total of 14,069 EC cases and 35,312 controls, Setiawan et al. concluded that risk factors for high-grade endometrioid and type II cancer were similar.31 Specifically considering type II or high-grade EC groups, Ko et al.32 found that BMI was not associated with decreased RFS or OS, which is in contradiction with our results. However, in the latter study, little evidence was provided regarding the surgical management of patients according to BMI.

In the current study, decreased RFS was not explained by undertreatment of women with severe obesity. According to the current ESMO guidelines, women with high-risk EC should be treated by total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, pelvic radiotherapy, and adjuvant chemotherapy according to nodal status.5 Previous studies documented that increasing obesity significantly impacts the decision to perform lymphadenectomy in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, particularly because of a higher postoperative complication rate (i.e. wound infection and venous thrombophlebitis).28 However, in the present study, no difference in surgical management was noted, especially concerning the rate of pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. According to the literature, radiotherapy6 and chemotherapy procedures7 have been reported difficult to perform on obese women. However, no difference in adjuvant therapies was observed in our population of severely obese women in the high-risk group. Finally, biological changes associated with obesity could be another explanation for a lower RFS. Indeed, obesity is associated with low-grade chronic inflammation,33 chronic hyperinsulinemia, alterations in the production of peptide and steroid hormones, which are postulated mechanisms involved in cancer development.34 Previous studies have shown that the adipose tissue of obese women leads to the synthesis of high levels of estradiol, and that frequent anovulation among obese premenopausal women leads to progesterone deficiency and unopposed estrogen exposure.26,35 Thus, as emphasized by Akhmedkhanov et al., these biological changes are responsible for endometrial cell proliferation, inhibition of apoptosis, and an increased number of DNA replication errors and somatic mutations.36 These biological disturbances and an inflammatory environment promoted by obesity may lead to cancer development or recurrence.37

Some limitations of the present study deserve to be underlined. First, we cannot exclude bias linked to the retrospective nature of the study. Second, the long study period from 2000 to 2012 meant that the patients included underwent different surgical management (i.e. systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy before 2010, which was only recommended for high-risk ECs from 2010 according to the revised French guidelines).24 Another factor was the introduction of the SLN biopsy in 2004, resulting in the detection of occult lymph node metastasis. Indeed, Raimond et al. demonstrated the impact of SLN biopsy on indications of adjuvant therapies impacting recurrence rate.38 Third, we did not take into account physical activity and diet, although several authors have previously shown that these factors may normalize hormone receptor expression profiles in the endometrium and positively influence survival.39 However, a recent study concerning 983 postmenopausal women with EC found that physical activity was not associated with survival.18 Finally, we did not include for analysis the type of diabetes treatment. Zhang et al. recently showed that metformin could positively impact progression of EC, probably via induction of CGRRF1 (cell growth regulator with ring finger domain) gene expression.40

Conclusions

Our results support the fact that severe obesity negatively impacts RFS in women with high-risk EC, underlining the importance of complete surgical staging and adapted adjuvant therapies in this subgroup of women. This is of major importance as physicians might be tempted to undertreat severely obese women with EC to avoid complications related to lymphadenectomy and/or adjuvant therapies. Future studies should focus on this subgroup of obese women with high-risk EC and possibly include the evaluation of physical activity, diet, and comorbidities.

References

Reeves KW, Carter GC, Rodabough RJ, Lane D, McNeeley SG, Stefanick ML, et al. Obesity in relation to endometrial cancer risk and disease characteristics in the Women’s Health Initiative. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(2):376–82.

Jeong NH, Lee JM, Lee JK, Kim JW, Cho CH, Kim SM, et al. Role of body mass index as a risk and prognostic factor of endometrioid uterine cancer in Korean women. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;118(1):24–8.

Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1625–38.

Nagle CM, Marquart L, Bain CJ, O’Brien S, Lahmann PH, Quinn M, et al. Impact of weight change and weight cycling on risk of different subtypes of endometrial cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(12):2717–26.

Colombo N, Preti E, Landoni F, Carinelli S, Colombo A, Marini C, et al. Endometrial cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi33-8.

Lin LL, Hertan L, Rengan R, Teo BK. Effect of body mass index on magnitude of setup errors in patients treated with adjuvant radiotherapy for endometrial cancer with daily image guidance. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(2):670–5.

Modesitt SC, Tian C, Kryscio R, Thigpen JT, Randall ME, Gallion HH, et al. Impact of body mass index on treatment outcomes in endometrial cancer patients receiving doxorubicin and cisplatin: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105(1):59–65.

Anderson B, Connor JP, Andrews JI, Davis CS, Buller RE, Sorosky JI, et al. Obesity and prognosis in endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(4):1171–8; discussion 8–9.

Everett E, Tamimi H, Greer B, Swisher E, Paley P, Mandel L, et al. The effect of body mass index on clinical/pathologic features, surgical morbidity, and outcome in patients with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90(1):150–7.

Gates EJ, Hirschfield L, Matthews RP, Yap OW. Body mass index as a prognostic factor in endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(11):1814–22.

Munstedt K, Wagner M, Kullmer U, Hackethal A, Franke FE. Influence of body mass index on prognosis in gynecological malignancies. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(9):909–16.

Temkin SM, Pezzullo JC, Hellmann M, Lee YC, Abulafia O. Is body mass index an independent risk factor of survival among patients with endometrial cancer? Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30(1):8–14.

Kodama J, Seki N, Ojima Y, Nakamura K, Hongo A, Hiramatsu Y. Risk factors for early and late postoperative complications of patients with endometrial cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;124(2):222–6.

Studzijnski Z, Zajewski W. Factors affecting the survival of 121 patients treated for endometrial carcinoma at a Polish hospital. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;267(3):145–7.

Chia VM, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM. Obesity, diabetes, and other factors in relation to survival after endometrial cancer diagnosis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17(2):441–6.

Mauland KK, Trovik J, Wik E, Raeder MB, Njolstad TS, Stefansson IM, et al. High BMI is significantly associated with positive progesterone receptor status and clinico-pathological markers for non-aggressive disease in endometrial cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(6):921–6.

von Gruenigen VE, Tian C, Frasure H, Waggoner S, Keys H, Barakat RR. Treatment effects, disease recurrence, and survival in obese women with early endometrial carcinoma : a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2006;107(12):2786–91.

Arem H, Chlebowski R, Stefanick ML, Anderson G, Wactawski-Wende J, Sims S, et al. Body mass index, physical activity, and survival after endometrial cancer diagnosis: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(2):181–6.

Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Cause-specific excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2007;298(17):2028–37.

Zanders MM, Boll D, van Steenbergen LN, van de Poll-Franse LV, Haak HR. Effect of diabetes on endometrial cancer recurrence and survival. Maturitas. 2013;74(1):37–43.

Ballester M, Dubernard G, Lecuru F, Heitz D, Mathevet P, Marret H, et al. Detection rate and diagnostic accuracy of sentinel-node biopsy in early stage endometrial cancer: a prospective multicentre study (SENTI-ENDO). Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(5):469–76.

Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6 Suppl 2:51S–209S.

Petru E, Luck HJ, Stuart G, Gaffney D, Millan D, Vergote I. Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup (GCIG) proposals for changes of the current FIGO staging system. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;143(2):69–74.

Cancer de l’endomètre, Collection Recommandations & référentiels, Boulogne-Billancourt: INCa; Nov 2010.

Delpech Y, Cortez A, Coutant C, Callard P, Uzan S, Darai E, et al. The sentinel node concept in endometrial cancer: histopathologic validation by serial section and immunohistochemistry. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(11):1799–803.

Arem H, Irwin ML. Obesity and endometrial cancer survival: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(5):634–9.

Crosbie EJ, Roberts C, Qian W, Swart AM, Kitchener HC, Renehan AG. Body mass index does not influence post-treatment survival in early stage endometrial cancer: results from the MRC ASTEC trial. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(6):853–64.

Gunderson CC, Java J, Moore KN, Walker JL. The impact of obesity on surgical staging, complications, and survival with uterine cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group LAP2 ancillary data study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133(1):23–7.

May K, Bryant A, Dickinson HO, Kehoe S, Morrison J. Lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD007585.

Bendifallah S, Canlorbe G, Raimond E, Hudry D, Coutant C, Graesslin O, et al. A clue towards improving the European Society of Medical Oncology risk group classification in apparent early stage endometrial cancer? Impact of lymphovascular space invasion. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(11):2640–6.

Setiawan VW, Yang HP, Pike MC, McCann SE, Yu H, Xiang YB, et al. Type I and II endometrial cancers: have they different risk factors? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(20):2607–18.

Ko EM, Walter P, Clark L, Jackson A, Franasiak J, Bolac C, et al. The complex triad of obesity, diabetes and race in type I and II endometrial cancers: prevalence and prognostic significance. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133(1):28–32.

Catalán V, Gómez-Ambrosi J, Rodríguez A, Frühbeck G. Adipose tissue immunity and cancer. Front Physiol. 2013;4:275.

Calle EE, Thun MJ. Obesity and cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23(38):6365–78.

Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(8):579-91.

Akhmedkhanov A, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Toniolo P. Role of exogenous and endogenous hormones in endometrial cancer: review of the evidence and research perspectives. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;943:296–315.

Dossus L, Rinaldi S, Becker S, Lukanova A, Tjonneland A, Olsen A, et al. Obesity, inflammatory markers, and endometrial cancer risk: a prospective case-control study. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(4):1007–19.

Raimond E, Ballester M, Hudry D, Bendifallah S, Darai E, Graesslin O, et al. Impact of sentinel lymph node biopsy on the therapeutic management of early-stage endometrial cancer: results of a retrospective multicenter study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133(3):506–11.

Pekmezi DW, Demark-Wahnefried W. Updated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(2):167–78.

Zhang Q, Schmandt R, Celestino J, McCampbell A, Yates MS, Urbauer DL, et al. CGRRF1 as a novel biomarker of tissue response to metformin in the context of obesity. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133(1):83–9.

Acknowledgment

None.

Disclosures

Geoffroy Canlorbe, Sofiane Bendifallah, Emilie Raimond, Olivier Graesslin, Delphine Hudry, Charles Coutant, Cyril Touboul, Géraldine Bleu, Pierre Collinet, Emile Darai, and Marcos Ballester have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence this work.

Funding

No external funding was used for this project. The authors volunteered their time and effort.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Canlorbe, G., Bendifallah, S., Raimond, E. et al. Severe Obesity Impacts Recurrence-Free Survival of Women with High-Risk Endometrial Cancer: Results of a French Multicenter Study. Ann Surg Oncol 22, 2714–2721 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4295-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4295-0