Abstract

Background

Cerebellar contusion accounts for 0.54% of traumatic brain injuries. They present with a variety of symptoms like ataxia, dysmetria, dysdiadokinesia, and vertigo. CT scan is the gold standard investigation for diagnosing acute cerebellar contusions. Due to the low incidence of this disease, there are no medical guidelines available for the management of cerebellar contusions.

Case report

A 2-year-old child presented to the emergency department with altered level of consciousness. Computed tomography scan of the brain showed midline cerebellar contusion. He was managed conservatively with the main focus on lowering intracranial pressure.

Result

Cerebellar contusion can be managed conservatively with close monitoring. However, more data is needed to study its behaviour and management.

Conclusions

The patient had an excellent response to treatment and was discharged within a few days further highlighting the role of medical management in the treatment of patients with cerebellar contusions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Contusions are defined as any injury to the body occurring following trauma that leads to blood vessel rupture and tissue destruction. Following contusions, the area is marked by active bleeding into the tissue [1]. This traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and affects up to 10 million individuals annually [2].

Tsai et al. state that only 3.3% of traumatic brain injuries involve the posterior fossa. These injuries include extra-dural hematomas, sub-dural hematomas, and rarely cerebellar contusions (which account for less than 1% of all head injuries) [3].

D’Avella et al. state that cerebellar contusions make up only 0.54% of all head injuries. He categorized the type of injuries causing cerebellar contusions into coup injuries (where the occiput is the area of impact), countercoup injuries (where the frontal or temporal area is targeted), and acceleration-deceleration injuries [4].

Cerebellar contusions present in a variety of ways. In adults, they will present with cerebellar signs like nystagmus, dysarthria, hypotonia, ataxia, dysmetria, tremor, dysdiadochokinesis, and vertigo [5]. In children, additional signs like cerebellar mutism have also been seen. One study by Braga et al. studied the neuropsychological sequelae in children with cerebellar trauma, according to the study, most children with cerebellar trauma develop dyscalculia and exhibit lower visual recognition memory [6].

Computed tomography scan is the gold standard investigation for evaluating cerebellar contusions. It shows the size of the contusion, its location, the status of fourth ventricles and cisterns, and any associated lesion like extra-dural or sub-dural hematomas.

Due to the rarity of traumatic intra cerebellar contusions, only case reports and case series are published detailing the presentation and the management of this disease with the management itself remaining quite controversial. Here, we present a case report of a male child with midline intra cerebellar contusion and his subsequent medical therapy. The management of our respective patient can help the greater scientific community in better understanding of the requisite treatment for this unique phenomenon.

Case report

A 2-year-old male child presented to the emergency department of Aga Khan University Hospital with a history of unwitnessed fall from height 12 h back. He presented with complaints of drowsiness and altered level of consciousness. On examination, he had a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 10/15 and was opening eyes to pain, crying on receiving painful stimuli while spontaneously moving all four limbs.

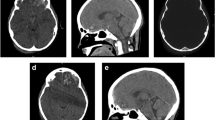

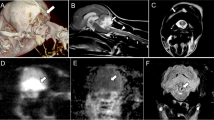

Immediately, his airway was protected and cervical spine was stabilized. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain showed midline cerebellar contusion with hydrocephalous and linear fracture of the occipital bone (Fig. 1).

Immediately, the patient was admitted to special care and was monitored hourly for drop in GCS. Nasogastric tube was inserted for feeding. Hyper-osmolar therapy was started to lower intracranial pressure. In few hours, the patient started showing improvement in Glasgow Coma score.

Eventually, the patient was shifted to general ward and was kept under observation. Within few days, the patient was discharged from the hospital with strict recommendations of continuous follow-up.

Discussion

The management of cerebellar confusion remains controversial owing to its very rare incidence. However, the conservative and surgical management remains the main treatment modalities.

According to Buczek et al., conservative management should be initiated in fully conscious patients in whom contusions lie superficially and are less than 3 cm in size [7]. D’Avella and Pollack et al. describes that surgical management of cerebellar contusion via a post occipital craniotomy is superior in comatose patients with larger contusions and associated hydrocephalus either associated with extra-dural or sub-dural hemorrhages [8, 9].

The results of these treatments are diverse depending on various factors. The most important of which is the initial Glasgow Coma score of the patients. D’Avella et al. [4] divided his patients into two groups on the basis of GCS score with group 1 having score of more than 9 and other group of less than 9 at the time of admission, 95% of cases in group 1 had a favorable outcome whereas only 19% of cases in group 2 had favorable outcomes.

Other determinants of patient prognosis included location of cerebellar contusion, its size, status of ventricle and associated cisterns, and presence or absence of associated lesions. Tekauchi et al. found out that contusions present in the inner part of the cerebellum (i.e., the midline and vermis) were associated with greater mortality and morbidity [10].

Nashimoto et al. further elaborated that lesions with concomitant supra-tentorial extension were associated with poorer prognosis and should ideally be managed with surgery (i.e., sub-occipital craniotomies and clot evacuation) [11].

Our patient showed improvement on conservative management only. The authors feel that is primarily due to the small size of his lesion and because his initial Glasgow Coma score was not very low. The authors further speculate that the patient’s excellent response to conservative treatment might also be due to his young age. A number of studies have already highlighted the positive correlation that exists between younger age group patients and their increased recovery rates following traumatic brain injuries [12, 13].

The major strength of our study lies in the establishment of conservative management as a valid and alternative treatment modality for the management of cerebellar contusions especially in younger individuals.

Conclusions

Cerebellar contusions can be treated via medical management in certain instances where the age of the patient is low and the Glasgow Coma Scale is high.

Abbreviations

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

- TBI:

-

Traumatic brain injury

References

Greve MW, Zink BJ. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Mount Sinai J Transl Personal Med. 2009;76(2):97–104.

Hyder AA, Wunderlich CA, Puvanachandra P, Gururaj G, Kobusingye OC. The impact of traumatic brain injuries: a global perspective. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22(5):341–53.

Tsai FY, Teal JS, Itabashi HH, Huprich JE, Hieshima GB, Segall HD. Computed tomography of posterior fossa trauma. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 1980;4(3):291–305.

D'Avella D, Cacciola F, Angileri FF, Cardali S. Traumatic intracerebellar hemorrhagic contusions and hematomas. J Neurosurg Sci. 2001;45(1):29.

van Gijn J. From the Archives. Brain. 2007;130(1):4–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl345.

Braga LW, Souza LN, Najjar YJ, Dellatolas G. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings and neuropsychological sequelae in children after severe traumatic brain injury: the role of cerebellar lesion. J Child Neurol. 2007;22(9):1084–9.

Buczek M, Jagodziński Z, Kopytek M, Dabrowska E. [Conservative treatment of post-traumatic intracerebellar hematoma]. Wiadomosci lekarskie (Warsaw, Poland: 1960). 1989;42(8):550–5.

Pollak L, Rabey JM, Gur R, Schiffer J. Indication to surgical management of cerebellar hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1998;100(2):99–103.

D’Avella D, Servadei F, Scerrati M, Tomei G, Brambilla G, Angileri FF, Massaro F, Cristofori L, Tartara F, Pozzati E, Delfini R. Traumatic intracerebellar hemorrhage: clinicoradiological analysis of 81 patients. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(1):16–27.

Takeuchi S, Takasato Y, Masaoka H, Hayakawa T. Traumatic intra-cerebellar haematoma: study of 17 cases. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25(1):62–7.

Nashimoto T1, Sasaki O, Nozawa T, Ando K, Kikuchi B, Watanabe M. Clinical Study on Cerebellar Contusion:A Report on 9 Cases and Literature Review. No Shinkei Geka. 2015;43(10):901–6.

Flanagan SR, Hibbard MR, Gordon WA. The impact of age on traumatic brain injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2005;16:163–77.

Mosenthal AC, Livingston DH, Lavery RF, et al. The effect of age on functional outcome in mild traumatic brain injury: 6-month report of a prospective multi-center trial. J Trauma. 2004;56:1042–8.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Dr. Maryam Tariq for the undue support and cooperation.

Availability of data and materials

Publication of patient’s data in this case report does not compromise anonymity or confidentiality or breach local data protection laws.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GJ supervised, corrected, and proof read the manuscript. He was involved in the identification of the uniqueness of the case and giving care to the patient. SB was involved in examining and managing the patient. He also wrote the case summary of the patient. YuI was involved in writing of the rest of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

I confirm that ethical approval was not required for reporting this case; informed written consent was taken from the child’s father.

Consent for publication

The father of the child was briefed in detail about the uniqueness of case and its management, risk, benefits, and alternate mode of treatment.

Written informed consent was taken to report and publish the case.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Javed, G., Bashir, S. & Islam, Y.u. Traumatic midline cerebellar contusion in 2-year-old male child—case report and review of literature. Egypt J Neurosurg 33, 6 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-018-0007-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-018-0007-6