Abstract

Test anxiety is a major concern in education because it causes uncomfortable feelings in test-anxious students and may reduce the validity of exam scores as a measure of learning. As such, brief and cost-effective interventions are necessary to minimize the negative impact of test anxiety on students’ academic performance. In the present experiment, we examine two such interventions: expressive writing (Experiment 1) and an instructional intervention (Experiment 2), with the latter developed from a similar intervention for stereotype threat. Across four authentic exams in a psychology class, students alternated between completing the intervention and a control task immediately before completing the exams. Neither intervention was effective at reducing test anxiety or improving exam performance. The present results suggest that these interventions may not be successful in addressing the impacts of test anxiety in all classroom settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As tests continue to be a fundamental aspect of higher education, test anxiety remains a critical concern for both students and educators (Zeidner, 1998, 2007). Test anxiety refers to negative thoughts, emotions and bodily symptoms triggered by evaluative situations such as quizzes and exams. The problem of test anxiety is twofold: not only does test anxiety produce uncomfortable reactions in students, it can also reduce their test performance, thereby leading to an underestimation of these students’ academic aptitude. Thus, test results might not be a valid measure of ability for test-anxious students, making identification of interventions to reduce the impact of test anxiety on performance of paramount importance. Unfortunately, treatment options for test anxiety are still limited. Most effective interventions require long treatment plans and a substantial amount of effort and financial resources from students and healthcare providers. The primary goal of the present study was to examine the extent to which expressive writing and knowledge acquisition through an instructional intervention—two brief and cost-effective interventions that have demonstrated promise in laboratory settings—might reduce the negative impact of test anxiety on exam performance in an authentic upper-level college class.

Effects of test anxiety in education

A significant proportion (15–40%) of students report experiencing test anxiety (Cizek & Burg, 2006; Hill & Wigfield, 1984; McDonald, 2001; Spielberger, Anton, & Bedell, 1976; Zeidner, 1998). Test-anxious students report a range of severe negative thoughts and physiological reactions in evaluative situations (Zeidner, 1998). Beyond their psychological well-being, test anxiety also harms students’ performance during evaluative situations. Indeed, test-anxious students have lower scores on standardized intelligence and aptitude tests (Alpert & Haber, 1960) and lower GPAs (Chapell et al., 2005), even though they spend more time studying compared to their non-anxious counterparts (Culler & Hollahan, 1980; Hembree, 1988). Most importantly, test-anxious students often underperform relative to their true ability, as evidenced by the finding that students with high-test anxiety perform as well as or even better than those with low-test anxiety when the pressure of an evaluative situation is alleviated (Beilock, 2008; Deffenbacher, 1978; Ganzer, 1968; Hancock, 2001; Sarason, 1972, 1973). For example, Deffenbacher (1978) asked students with high- and low-test anxiety to solve difficult anagrams. Before the task, students received either high-stress instructions, which emphasized that their performance was a measure of intelligence, or low-stress instructions, which emphasized that this was a difficult task and they were not expected to perform perfectly. Students with high-test anxiety only performed worse than those with low-test anxiety under high-stress instructions, but not low-stress instructions. Consequently, test scores may have poor construct validity as a measure of student abilities because they tend to underestimate the true academic abilities of test-anxious students (Bonaccio, Reeve, & Winford, 2012; Meijer, 2001; Rocklin & Thompson, 1985; Spielberger, 1966; Zeidner, 1990, 1998). Nevertheless, many life-altering decisions such as college admission, scholarships and career opportunities are still influenced by test scores, to the detriment of test-anxious individuals.

Despite its serious implications for the fairness of exams, test anxiety is rarely addressed in student orientations or curricula. Instead, students must seek their own accommodations and treatment if they suffer from test anxiety. Although treatment options exist (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, study skills training, systematic desensitization), they often require substantial time and financial commitments, and they are not always effective (see Ergene, 2003; Von Der Embse, Barterian, & Segool, 2013, for reviews). With the high prevalence of test anxiety and difficulty in receiving long-term mental health treatments, a more realistic solution may be to administer short-term interventions to large groups of students aimed at allowing test-anxious students to perform to their true abilities on exams (i.e., reducing the negative effects of test anxiety on performance).

A thorough understanding of the components of test anxiety may allow such interventions to be developed. Liebert and Morris (1967) first proposed that test anxiety is composed of two main factors, worry and emotionality, and these factors have since received considerable support in the literature (e.g., Chapell et al., 2005; Sarason, 1974). Worry—the cognitive component—refers to intrusive thoughts that individuals experience during tests, such as the consequences of failure or concern about others’ performance (Zeidner, 1998). Emotionality—the physiological component—refers to the bodily changes that students experience in response to evaluative situations, such as an upset stomach or racing heart (Zeidner, 1998). Although test-anxious students report experiencing both components, research suggests that worry affects exam performance more than emotionality (e.g., Chapell et al., 2005; Hembree, 1988) because worrying thoughts occupy working memory resources. Consequently, those worrying thoughts might interfere with memory retrieval and other cognitive operations needed to perform well on exams (Culler & Holahan, 1980; Eysenck & Calvo, 1992; Eysenck, Derakshan, Santos, & Calvo, 2007; Sarason, 1980; Unsworth & Engle, 2007).

This working memory account has received broad empirical support. For example, test anxiety is more detrimental to students with lower working memory capacity (WMC) than students with higher WMC (Tse & Pu, 2012; see also Ansari & Derakshan, 2011a, 2011b; Calvo & Eysenck, 1998; Moran, 2016; Owens, Stevenson, Hadwin, & Norgate, 2014).Footnote 1 The idea is that students with higher WMC can use their more plentiful cognitive resources to buffer against the worrying thoughts that occupy their working memory. Based on these effects of test anxiety on cognitive resources, interventions aimed at alleviating intrusive thoughts should help relieve students from their negative impact. The current experiments examined the effectiveness of two such interventions.

Expressive writing

One intervention that has been proposed to reduce worrying thoughts is expressive writing, where writers freely write about their concerns, feelings or experiences associated with an undesirable situation (e.g., taking an exam in the present context). Expressive writing has been shown to reduce general anxiety (Alparone, Pagliaro, & Rizzo, 2015; Hines, Brown, & Myran, 2016; Smyth & Pennebaker, 2008; Van Emmerik, Kamphuis, & Emmelkamp, 2008), depression (Frattaroli, Thomas, & Lyubomirsky, 2011; Lepore, 1997) and ruminative thoughts (Gortner, Rude, & Pennebaker, 2006). Expressive writing has also been used successfully among college students. Specifically, asking students to write about their college concerns for several days led to an increase of their GPA the following semester (Lumley, & Provenzano, 2003; Pennebaker & Francis, 1996). These expressive-writing interventions are typically administered for long durations, with participants sometimes writing for multiple sessions across weeks or months. These longer interventions are thought to allow writers to better unpack and understand stressful experiences, eventually leading to changes in their thought patterns surrounding uncomfortable feelings (Pennebaker & Seagal, 1999).

However, some evidence suggests that even one short period of expressive writing can have positive effects on writers. With these short interventions, expressive writing is thought to allow an anxious writer to offload their worries onto paper, so that these worrying thoughts will no longer consume their working memory resources during an upcoming task (Schroder, Moran, & Moser, 2018). These benefits hold particular promise as an intervention for test anxiety because the negative impacts of test anxiety are thought to be driven by worrying thoughts consuming test-takers’ working memory resources (Alparone et al., 2015; Joormann & Tran, 2009; Kellogg, Mertz, & Morgan, 2010; Klein & Boals, 2001; Smyth & Pennebaker, 2008).

One such intervention was used in a study by Ramirez and Beilock (2011), which showed that a brief expressive-writing exercise reduced the negative effects of test anxiety on test performance in high school and college students. This study was especially consequential because the intervention was much shorter than what has been used in previous expressive-writing interventions (on the order of minutes instead of days). In both laboratory and classroom settings, having students expressively write for only 10 min before a test improved test-anxious students’ performance, despite no changes to their level of test anxiety. Ramirez and Beilock (2011) argued that more intensive treatments may be required to reduce test anxiety, but expressive writing may break the link between test anxiety and lowered exam performance by freeing up cognitive resources. In other words, students may still have experienced test anxiety, but that experience no longer negatively impacted their performance.

Ramirez and Beilock’s (2011) expressive-writing intervention provides a promising option for a fast-acting, in-class intervention that could allow students’ exam scores to more closely reflect their true ability. However, a recent, widely-cited replication project by Camerer and others (2018, see also Buttrick et al., 2016) cast doubt on the reliability of this finding. Camerer et al. (2018) attempted twice to replicate Ramirez and Beilock’s study (Experiment 2), but both of their amply-powered experiments failed to find a benefit of expressive writing on test performance, with the resulting effect sizes being slightly negative (i.e., expressive writing non-significantly harmed performance). Indeed, closer scrutiny of other studies exploring the effects of expressive writing on test anxiety reveals that results are quite mixed. Some studies have found that expressive writing reduces test anxiety or at least improves test-anxious students’ performance (Allen, 2017; Clinton & Meester, 2019; Frattaroli et al., 2011; Harris et al., 2019; Rozek, Ramirez, Fine, & Beilock, 2019; Shen, Yang, Zhang, & Zhang, 2018; see Park, Ramirez, & Beilock, 2014 for math anxiety). However, a number of studies have not found evidence of these benefits (Allen, 2017; Blank-Spadoni, 2013; Ganley, Conlon, McGraw, Barroso, & Geer, 2021; Relojo-Howell & Stoyanova, 2019; Sefton, 2014; Spielberger, 2015; Walter, 2018; see also Wolitzky-Taylor & Telch, 2010). As one example, Spielberger (2015) tested 110 college students from six undergraduate psychology courses. Prior to a course exam, students either expressively wrote about their anxiety or wrote about what they did the previous day. Spielberger (2015) found that expressive writing did not improve participants’ exam performance compared to their previous course exam score. We were unable to identify any obvious systematic differences among existing studies that would reconcile these contradictory findings. Consequently, our approach is to examine whether expressive writing impacts feelings of test anxiety or performance on authentic college course exams in a high-powered study in Experiment 1.

Instructional intervention

In addition to the expressive-writing intervention, we also examined the efficacy of a novel instructional intervention. This intervention was developed from a similar intervention used to reduce stereotype threat effects (Johns, Schmader, & Martens, 2005).Footnote 2 Stereotype threat refers to the activation of a negative stereotype about one’s social group or identity, which then causes one to underperform on a task (for reviews, see Appel & Kronberger, 2012; Steele, 1998; Wheeler & Petty, 2001; but see Flore & Wicherts, 2015). For example, a common stereotype is that women perform worse in math than men. When this stereotype is brought to women’s attention before they complete a math task, their math performance is reduced compared to women who are not made aware of the stereotype. This is thought to occur because the added stress of needing to refute the stereotype co-opts cognitive resources, thus leading to lower performance (e.g., Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999; but see Flore & Wicherts, 2015; Stoet & Geary, 2012; Stricker & Ward, 2004).

In their instructional intervention against stereotype threat, Johns et al. (2005) gave men and women a brief essay explaining the impact of stereotype threat on performance, particularly focusing on the fact that lower performance in the face of stereotype threat is not an indicator of one’s true ability (see also Good, Aronson, & Inzlicht, 2003). Remarkably, simply giving students this knowledge allowed women to perform at a similar level as men on difficult math problems (materials for which women tend to perform worse than men under conditions that induce stereotype threat). The researchers theorized that the intervention provided students with an opportunity to reappraise the evaluative situation by attributing their negative thoughts and arousal to an external source (e.g., social pressure) instead of their own perceived incapabilities (see Ben-Zeev, Fein, & Inzlicht, 2005; McGlone & Aronson, 2007). Although Johns and associates’ results were promising, Tomasetto and Appoloni (2013) subsequently found that merely informing students about stereotype threat may not be enough to benefit students’ performance and may even harm performance. Instead, they argued that knowledge of stereotype threat needs to be combined with messages about how to address stereotype threat—a technique that we exercised in Experiment 2.

Although test anxiety and stereotype threat are different psychological constructs, both have been theorized to affect cognition through interfering thoughts and physiological arousal that deplete cognitive resources (Johns, Inzlicht, & Schmader, 2008; Schmader, Johns, & Forbes, 2008; see also Beilock & Ramirez, 2011). Therefore, if learning about stereotype threat allows one to externalize negative ruminations and free cognitive resources, then learning about the nature of and how to address test anxiety may have a similar effect for test-anxious students. Accordingly, we developed an instructional intervention that aimed to teach students about test anxiety, emphasizing the prevalence of test anxiety, the cause-and-effect relationship between anxiety and performance, and coping methods for test anxiety. We tested this intervention as a means to reduce the effects of test anxiety for college students in Experiment 2.

The current experiments

The two interventions, expressive writing and the instructional intervention, were administered in an upper-level cognitive psychology course at a large public university. As such, our participants were students taking authentic college exams with real stakes in a challenging course. Experiment 1 reports the efficacy of expressive writing for students who enrolled in the course in the fall of 2014, spring of 2015 and spring of 2016, whereas Experiment 2 reports the efficacy of the instructional intervention for students who enrolled between fall 2016 and spring 2017. A rigorous experimental design was used where students alternated between the intervention task and a control task for each of four exams. Thus, an A-B-A-B design was implemented, with the order of tasks counterbalanced across students within each class. For example, half of the students completed the expressive-writing task for Exam X and the control-writing task for Exam X + 1, with the reverse occurring for the remaining students. This design allows within-subject comparisons of exam scores after completing the intervention versus control task—which is statistically more powerful than between-subjects designs that have been used predominantly in the extant literature.

Experiment 1

In the first experiment, we sought to determine whether completing a brief expressive-writing exercise could reduce the negative effects of test anxiety on exam performance. Immediately prior to each of four course exams, students in a psychology course completed either an expressive-writing or a control-writing task. Note that neither the instructor nor the assigned textbook covered the topic of test anxiety during the semester, except when students were introduced to the experiment during the first class.

Method

Participants

Over three semesters, 195 undergraduate students who were enrolled in a 300-level cognitive psychology course at Iowa State University participated in the study. Twenty-two students were removed from data analysis: eight dropped the course, six took the exams in a different location so could not be monitored during the intervention tasks, seven did not complete Exams 2 and 3 (which were used in analyses), and one was retaking the course. The final analyses were completed using the 173 remaining participants. We did not conduct an a-priori power analysis to determine sample size, but based on the effect size reported in Ramirez and Beilock (2011, Experiment 1, d = 0.57),Footnote 3 our sample size would provide 0.999 power in a repeated-measures design. Demographic information was not collected.

Materials and procedure

On the first day of the course, the instructor introduced the research project on interventions for test anxiety. After this brief introduction, the instructor left the room and the experimenter gave all students more details about the project. Students were told they could choose to participate in the experiment in exchange for extra credit,Footnote 4 and those wishing to participate completed a consent form. Next, each student received a paper packet with the alpha span task (Craik, 1986), achievement goals survey (Elliot & Murayama, 2008), backward digit span task (Woodworth, 1938) and trait test anxiety inventory (T-TAI; Spielberger, 1980). All students completed these tasks at the same time in the classroom, with written or verbal instructions given by the experimenter.

The alpha-span task consisted of 14 lists of one-syllable words (Craik, 1986). The students’ task was to listen to the words of each list (e.g., “gulf, mud, corn”) and then recall them in alphabetical order (e.g., “corn, gulf, mud”). List length increased from two to eight words, with two lists for each length. The experimenter described this task and then read the lists one at a time at a rate of about 1 s per word. Immediately after each list was presented, students were given 5 s per word to recall each list. Words that sounded similar to the correct word were considered correct (e.g., “golf” instead of “gulf”) due to the nature of the oral presentation. Minor spelling errors were also accepted. Students’ total alpha span scores corresponded to the total number of lists for which a student recalled all of the presented words in the correct order, with no intrusions.

Following the alpha span task, students completed the achievement goals survey (Elliot & Murayama, 2008). Students read a series of statements (e.g., “My aim is to completely master the material presented in this class.”) and indicated their level of agreement on a five-point scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Scores were calculated as the sum of students’ responses to all survey questions, with a higher score indicating the student had higher motivation to achieve in the course.

Next, students completed the backward digit span task. In this task, students heard 16 lists of digits, one list at a time, and then recalled the digits of each list in the reversed order of how they were presented (Woodworth, 1938). For example, if the experimenter read 2, 5, 3, students should recall 3, 5, 2. List length increased from two to nine digits, with two lists of each length. Students were explicitly discouraged from cheating by recalling the digits in the forward order but simply writing from right to left. Students were given four seconds per digit during recall. Students’ backward digit span score corresponded to the total number of lists for which they recalled the correct digits in the correct order. In hindsight, given that we could not verify whether students cheated on this task, we opted to omit this task from analyses.

Lastly, students’ test anxiety was measured using the T-TAI (Spielberger, 1980). They read statements regarding test anxiety (e.g., “While taking examinations I have an uneasy, upset feeling”) and indicated how often they agreed with the statement on a 4-point scale (1 = almost never, 4 = almost always). T-TAI total, worry and emotionality scores were calculated following scoring methods detailed in Spielberger (1980). After students completed all four measures (alpha span, achievement goals survey, backward digit span and the T-TAI), their packets were collected, the experimenter left the classroom and the instructor returned.

Approximately 2 weeks later, students completed their first course exam without any experimental tasks. Exams 2–5 then served as the experimental blocks, and the instructor was not present for these exams. Immediately prior to Exams 2 through 5, participating students completed either the expressive-writing intervention task (Ramirez & Beilock, 2011) or the control-writing task in an A-B-A-B design (see Fig. 1). Students were randomly assigned to complete either expressive writing or control writing for Exam 2, and alternated thereafter so that each student completed the intervention task twice and control task twice. Students not participating in the study sat quietly while participants completed these tasks.

Students were provided with either an intervention task or control task packet when they arrived for their exam. The packets included instructions for the task, blank lines for students to write their responses, and the State-Test Anxiety Inventory (S-TAI; Spielberger, 1980). Our instructions for the writing tasks mirrored those in Ramirez and Beilock (2011). In the expressive-writing task, students were given the following instructions:

We would like you to take the next eight minutes to write as openly as possible about your thoughts and feelings regarding the exam you are about to take. In your writing, I want you to really let yourself go and explore your emotions and thoughts as you are getting ready to start the exam. You might relate your current thoughts to the way you have felt during other similar situations at school or in other situations in your life. Please try to be as open as possible as you write about your thoughts at this time.

In the control-writing task, students were given the following instructions:

We would like you to take the next eight minutes to write about how you spent your day yesterday. Describe how you spent your time as factually and unemotionally as possible.

All students were encouraged to write for the entire eight minutes. After the writing task, students completed the S-TAI, which asked students to indicate how well each of 27 statements regarding test anxiety described them on a four-point scale (1 = Not at all typical of me, 4 = Very typical of me). A total S-TAI score was calculated for each course exam by summing students’ responses.Footnote 5 S-TAIs were not completed for Exams 4 and 5 because relationships between state test anxiety and writing tasks were established in prior exams. We used both the T-TAI and S-TAI because test anxiety can be measured as both a trait and state (Zeidner, 1998). Trait test anxiety is a student’s overall tendency to experience test anxiety during evaluative situations. In contrast, state test anxiety is a student’s feelings of test anxiety for a specific exam.

Once students finished their pre-exam tasks, they completed the exams at their own pace during the remainder of the class (65 min). All exams used the same format, with 15 multiple-choice questions and three essay questions (they chose two to answer). When a student finished the exam, they turned in both the exam and the pre-exam task packet.

Results and discussion

For the focal analyses, we report the p-value, a standardized effect size measure (Pearson’s r or Cohen’s d), and the Bayes factor (BF). Bayes factors provide a ratio of the likelihood of the data given the alternative hypothesis (i.e., a difference between comparison groups) relative to the null hypothesis (i.e., no difference), expressed as BF10 (see Kruschke, 2013, for a discussion of Bayes factors). A Bayes factor of 1 means that the data are equally likely under the alternative and null hypotheses. Unlike null hypothesis significance testing, Bayes factors can indicate that the null hypothesis is more probable than the alternative hypothesis (i.e., when BF10 < 1). For results supporting the null hypothesis, we report the Bayes factors via the reciprocal ratio, denoted as BF01, such that a larger number provides more support for the null. In other words, a larger Bayes Factor always provides more support of the effect’s direction. Following Rouder, Speckman, Sun, Morey, and Iverson (2009), we used the JZS prior because it requires the fewest prior assumptions about the range of the true effect size. A correlation matrix of the key measures is included in the supplemental materials (Additional file 1: Table S1) available on OSF.

Test anxiety characteristics

The average T-TAI scores for our students (M = 44.04, SD = 12.74) were consistent with established norms (Szafranski, Barrera, & Norton, 2012). The two sub-scales, worry (M = 16.34, SD = 5.36) and emotionality (M = 18.73, SD = 5.50), were also similar to established norms. The average S-TAI score was in the middle of the range of possible scores (M = 66.19, SD = 16.29).

Writing analysis

The content of the writing tasks (both expressive and control) was analyzed using Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) software (Pennebaker, Booth, & Francis, 2007).Footnote 6 LIWC calculates the number of words in a piece of writing from different categories in the program’s corpus (e.g., anxious words – nervous, tense) as a function of the total number of words in the writing. Consistent with our expectation, participants used far more anxiety-related words when completing the expressive-writing task (M = 1.9%, SD = 1.41%) compared to the control-writing task (M = 0.2%, SD = 0.44%), t(158) = 14.94, p < 0.001, d = 1.18, BF10 = 5.90 × 1028. This confirmed that students were correctly writing down their worries about the upcoming exam in the expressive-writing task and were not writing about their anxiety during the control-writing task. Further confirming the validity of the expressive-writing task, higher T-TAI scores were associated with more frequent use of anxiety-related words in the expressive-writing task (r = 0.29, p < 0.001).

Working memory and achievement goals

Students’ working memory and achievement goals scores had only slight correlations with students’ exam scores and test anxiety (see Additional file 1: Table S1), and conclusions did not change when considering these variables. Therefore, neither measure will be discussed further. For interested readers, additional analyses with working memory are included in the Additional files.

Carryover effects

Given the nature of the within-subject design, the impact of the intervention could have carryover effects to subsequent exams (e.g., having done a prior expressive-writing task may reduce its future effectiveness or could lead students to implement the intervention on their own in the subsequent control task). Analyses that evaluate this possibility are reported in the supplemental materials and do not suggest that carryover effects impacted the main conclusions.

Did expressive writing reduce test anxiety?

A negative correlation was found between students’ exam performance and state test anxiety (S-TAI) scores when students completed the control-writing (r = −0.20, p = 0.01, BF10 = 2.91) and expressive-writing task (r = −0.20, p = 0.01, BF10 = 3.26). A t-test was conducted to compare average S-TAI scores after students completed the expressive-writing task compared to the control-writing task. This test indicated that, overall, students’ S-TAI scores did not differ after completing the expressive-writing or control-writing task, t(172) = 0.06, p = 0.95, d < 0.01, BF01 = 11.77. Thus, it does not appear that expressive writing reduced students’ feelings of test anxiety.

Did expressive writing improve exam scores?

Although we did not find effects of expressive writing on test anxiety levels, the expressive-writing session may have still reduced the impact of test anxiety on exam scores and allowed test-anxious students to perform to their true potential (Ramirez & Beilock, 2011). This is, in fact, the key question of the present investigation. Average exam scores for the four experimental exams are reported in Table 1. As can be seen, performance did not differ between the expressive writing and control conditions for either Block 1 or 2. To maximize our sample size (11% of students dropped the class or missed one or more exams during Block 2), we constrained our analyses to only Exams 2 and 3—the first time students completed the experimental tasks.Footnote 7 Overall, exam scores did not differ after students completed the expressive-writing (M = 73%) or control-writing task (M = 74%), t(172) = 0.37, p = 0.72, d = 0.03, BF01 = 11.04. Even among the participants who showed higher test anxiety (i.e., those in the top-half of the T-TAI score distribution, N = 87), expressive writing (M = 72%) did not improve exam performance relative to control writing (M = 72%), t(86) = 0.15, p = 0.89, d = 0.02, BF01 = 8.36.

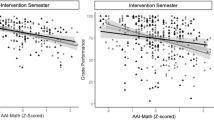

Next, we considered whether expressive writing changed the relationship between test anxiety and exam scores. The correlation between students’ T-TAI and exam score when they completed the control-writing task was small and non-significant (r = −0.07, p = 0.35, BF01 = 6.78), as was the correlation when they completed the expressive-writing task (r = −0.06, p = 0.41, BF01 = 7.55). The relationship between T-TAI and exam scores is shown in Fig. 2. As can be seen from the overlapping regression lines, writing task had essentially no effect on the relationship between test anxiety and exam performance. A z-test comparing the correlations when students completed the expressive-writing and control-writing task indicated that these correlations did not differ from one another,Footnote 8z(two-tailed) = −0.13, p = 0.90.

Worry sub-component

The T-TAI scale comprises two sub-components: worry and emotionality. Worry has been shown to correlate higher with exam scores than emotionality (Chapell et al., 2005; Hembree, 1988), so we also examined the effects of expressive writing based on students’ worry scores. Including the full sample of students, the correlation between worry and exam scores when students completed the control-writing task was weak but significant (r = −0.19, p = 0.01, BF10 = 1.76), as was the correlation when they completed the expressive-writing task (r = −0.18, p = 0.02, BF10 = 2.07). Contrary to the idea that expressive writing would weaken the negative effects of test anxiety on exam performance, these correlations did not differ from one another, z(two-tailed) = −0.07, p = 0.95.

Strengthening the test anxiety and exam performance relationship

We have reported several analyses above and in the supplemental materials that suggest that expressive writing did not alter the relationship between test anxiety and exam scores. However, one consideration remains: the correlation between test anxiety and exam performance was weak in the present experiment even without expressive writing (i.e., when participants completed the control writing task; r = −0.07). It might be difficult for any intervention to decrease such a small relationship. This weak relationship between test anxiety and exam performance was mainly due to many students with low-test anxiety performing poorly on exams and other students with the highest levels of test anxiety performing well on exams (thus not following the expected pattern). To further examine the effectiveness of expressive writing, we conducted an exploratory analysis using a multiverse analysis approach (see Steegen, Tuerlinckx, Gelman, & Vanpaemel, 2016). We selected a subset of participants who exhibited the predicted pattern between test anxiety and exam performance, thereby coercing a stronger negative correlation between test anxiety and exam performance when students completed the control-writing task.

To this end, we separated students using a median split into those with low-test anxiety (T-TAI scores below the median) and high-test anxiety (T-TAI scores above the median). Next, we removed the lowest-performing 25 students in the low-test anxiety group and the highest-performing 26 students in the high-test anxiety group based on their Exam 1 scores, which served as a baseline. This constitutes a removal of 30% of our sample, which is admittedly arbitrary, but we feel that this is a reasonable sacrifice in an exploratory analysis.

This subsample of 120 students produced a strong correlation between students’ T-TAI and exam scores in the “desired” direction (r = −0.60, p < 0.001, BF10 = 3.02 × 1010) on the baseline exam, thereby establishing a more favorable condition for us to investigate the influence of expressive writing on exam performance. Using this subsample, we examined whether expressive writing diminished the correlation between test anxiety and exam performance for Exams 2 and 3—it did not (as can be seen in Fig. 3). Specifically, participants who completed the control-writing task exhibited roughly the same correlation (r = −0.27, p = 0.02, BF10 = 13.70) as those who completed the expressive-writing task (r = −0.24, p = 0.01, BF10 = 4.14),Footnote 9z(two-tailed) = 0.33, p = 0.74. Moreover, across this subsample, expressive writing did not improve participants’ exam performance, Mcontrol = 73% vs. Mexpressive = 72%, t(119) = 0.21, p = 0.83, d = 0.02, BF01 = 9.65. In fact, expressive writing did not improve exam performance even when we restricted the comparison to just participants who exhibited high-test anxiety (i.e., the top-half of the distribution in terms of T-TAI) within the subsample, Mcontrol = 66% vs. Mexpressive = 67%, t(59) = 0.47, p = 0.64, d = 0.06, B01 = 6.36. Taken together, our results suggest that expressive writing had little to no effects on exam performance regardless of whether there was a strong or weak association between test anxiety and exam performance. In multiverse analyses, it is also important to show that results are not contingent upon the removal criteria used (c.f., Chalkia, Van Oudenhove, & Beckers, 2020a; Chalkia, Van Oudenhove, & Beckers, 2020b). Thus, we also conducted similar analyses after removing 20% and 40% of the sample, and the conclusions remained the same as those presented.

Experiment 2

Our first experiment showed that expressive writing was ineffective at reducing test anxiety or improving exam scores. In the second experiment, we determined whether an instructional intervention could alleviate the negative effects of test anxiety. Students alternated between reading an essay about test anxiety (instructional essay) and a control essay about an unrelated topic across four exams. Once again, neither the instructor nor the textbook covered the topic of test anxiety.

Method

Participants

Over two semesters, 132 students enrolled in a cognitive psychology course participated in the study. Twenty-one students were removed from Experiment 2: nine dropped the course, six were retaking the course, four took the exams in a different location, one worked in the research lab responsible for the project and one chose to stop participating. This left 111 students in the study. Again, we did not perform an a priori power analysis to determine sample size, but based on the effect size reported in Johns et al., (2005, d = 1.21),Footnote 10 our sample size would provide 0.997 power in a repeated-measures design.

Materials and procedure

The procedure was similar to Experiment 1 but with the following changes that we implemented to increase the likelihood of finding a successful intervention effect. First, we dropped the backward digit span task from the procedure due to the ease of cheating. Second, the S-TAI was administered after participants handed in their exams. We opted for this change because we hoped to find a stronger relationship between S-TAI and performance than that observed in Experiment 1, and state test anxiety has a stronger relationship with exam performance when it is administered after students are exposed to the exam than before (Seipp, 1991; Zeidner, 1998). Third, students completed the experimental tasks for Exams 1–4 instead of Exams 2–5 (see Fig. 4 for a diagram)—Exam 1 was not used as a baseline. This was due to the possibility that test anxiety might harm students’ first exam performance more than later exams. Thus, an intervention may be more impactful for the first course exam than for later ones. Fourth and most importantly, participants were given the instructional intervention rather than expressive writing. A different control task was also created for Experiment 2 to be analogous to the instructional intervention. For both tasks, participants read an essay, took a three-question multiple-choice quiz over the essay, and lastly reviewed written feedback of the quiz. The entire task took about 12 min.

The instructional intervention was a three-page essay (985 words) discussing the prevalence of test anxiety, how test anxiety can hinder performance via cognitive interference, and brain regions that are impacted by test anxiety (see Appendix 1). Lastly, the essay covered what students can do about test anxiety, including cognitive behavioral therapy, more frequent testing and expressive writing. Thus, our instructional intervention taught participants the nature of test anxiety (similar to Johns et al., 2005, but at a more extensive scale) and provided them with information on how to address test anxiety (thereby fulfilling the recommendation made by Tomasetto & Appoloni, 2013). We also included a brief quiz to check students’ understanding. For the control task, students read an essay (923 words) about handedness (see Appendix 2), which explained the genetic traits and cultural influences that determine handedness. Thus, we incorporated an active control condition that was absent in some prior studies (e.g., Johns et al., 2005).

Results and discussion

Data were analyzed using the same methods as Experiment 1. A correlation matrix of the key collected measures is included in the supplemental materials (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Test anxiety characteristics

The average T-TAI for this sample of students (M = 46.52, SD = 13.05) were again consistent with established norms (Szafranski et al., 2012), as were worry (M = 17.08, SD = 5.25) and emotionality (M = 19.79, SD = 5.83) averages. The average S-TAI score was in the middle of the range of possible scores (M = 70.42, SD = 16.44).

Working memory, achievement goals and carryover effects

Our conclusions of the study again did not change when considering the variables of WMC and achievement goals, so neither measure will be discussed further. Nonetheless, we reported data concerning working memory and possible carryover effects in the supplemental materials.

Essay quiz questions

Students answered a majority of the essay quiz questions correctly, although students scored better on the test anxiety quiz (M = 2.80, SD = 0.40) than the handedness, control quiz (M = 2.30, SD = 0.70), t(110) = 7.21, p < 0.001, d = 0.69, BF10 = 1.20 × 108. Note that due to disparities in both the content and the questions themselves, performance differences in the two quizzes are not interpretable. The correlations between students’ test anxiety (T-TAI) and their control essay quiz score (r = −0.18, p = 0.06, BF01 = 1.52) and instructional essay quiz score (r = −0.19, p = 0.04, BF01 = 1.07) were both near the threshold of statistical significance, suggesting that students’ test anxiety may even impact their performance on a low-stakes quiz. However, we caution against over-interpreting these results given their borderline effects.

Did the instructional intervention reduce test anxiety?

Negative correlations were found between students’ exam performance and S-TAI scores when they read the control essay (r = −0.23, p = 0.02, BF10 = 2.15) and the instructional essay (r = −0.32, p < 0.001, BF10 = 32.37), and these correlations did not differ from each other, z(two-tailed) = 0.94, p = 0.35, meaning that higher state test anxiety predicted lower exam performance regardless of the task students completed. Students’ average test anxiety on exam days after completing the instructional (M = 70.1) versus control essay (M = 70.7) also did not differ, t(110) = 0.80, p = 0.42, d = 0.08, BF01 = 6.94, suggesting that the instructional intervention did not reduce students’ feeling of test anxiety. However, note that because the S-TAI was administered after students completed the exam in Experiment 2, their S-TAI scores might have also been impacted by their experiences with the exam in addition to any impact of the intervention and control essays.

Did the instructional intervention improve students’ exam scores?

Average exam scores are reported in Table 2. Again, only data from the first exams for which students completed the instructional and control readings (Exams 1 and 2)Footnote 11 were analyzed. Overall, exam scores did not differ after students read the instructional (M = 69%) or control essays (M = 70%), t(110) = 0.42, p = 0.67, d = 0.04, BF01 = 8.71. The instructional intervention did not enhance exam performance even when we limited the analysis to only participants who reported higher test anxiety (i.e., top half of the distribution according to their T-TAI score, N = 55), Minstructional = 65%, Mcontrol = 69%, t(54) = 1.42, p = 0.16, d = 0.19, BF01 = 2.63.

The correlation between students’ T-TAI and exam scores when students read the control essay was numerically stronger than Experiment 1, but still non-significant (r = −0.13, p = 0.17, BF01 = 3.32). In contrast to our prediction, students exhibited a stronger negative association between T-TAI and exam score when they read the instructional essay (r = −0.22, p = 0.02, BF10 = 1.88). However, these correlations did not significantly differ from each other, z(two-tailed) = 1.03, p = 0.31. This again suggests that the intervention did not weaken the relationship between test anxiety and exam performance. Indeed, if anything, the instructional intervention exacerbated the association between test anxiety and exam performance. These associations are depicted in Fig. 5.

Worry sub-component

The correlation between worry scores and exam performance when students read the control essay was moderate and significant (r = −0.23, p = 0.01, BF10 = 2.45). Contrary to the hypothesis that the instructional intervention would weaken this relationship, the correlation between worry and exam performance when students read the instructional essay was numerically (r = −0.28, p = 0.003, BF10 = 9.83) but not significantly stronger, z(two-tailed) = 0.53, p = 0.60.

Strengthening the test anxiety and exam performance relationship

Although the relationship between test anxiety and exam performance was stronger than in Experiment 1, these correlations were still weak. Thus, we repeated the same procedure as Experiment 1 to select a group of participants who displayed a stronger correlation between T-TAI and exam score. Unlike Experiment 1, we did not administer a baseline exam for which participants did not complete any task beforehand. Therefore, we used participants’ control exam score in Exam 3 or 4 as the baseline performance and to establish its association with participants’ T-TAI score. We again separated students using a median split into those with low- and high-test anxiety and then removed the lowest-performing 15 students (based on their Exam 3 or 4 score) with low-test anxiety and the top-performing 15 students with high-test anxiety. This again constituted a removal of 30% of the sample, and we reached the same conclusions when we removed 20% and 40% of the sample. Nine additional participants did not complete the control Exam 3 or 4 and were removed from this analysis. This left a total of 71 participants in the subsample. This subsample exhibited a robust correlation between students’ T-TAI and exam scores (r = −0.61, p < 0.001, BF10 = 1.13 × 106). The results from this subsample echoed that from the full sample, such that students showed a numerically, but not significantly, stronger negative association between test anxiety and exam score when they completed the instructional intervention (r = −0.35, p = 0.003, BF10 = 10.99) than when students completed the control task (r = −0.22, p = 0.07, BF10 = 0.77), z(two-tailed) = 0.81, p = 0.42. See Fig. 6 for a scatterplot of these associations. Once again, if anything, the instructional intervention might have exacerbated the association between test anxiety and exam performance in this subsample.

General discussion

Test anxiety remains a major concern in education given the continued use of testing to inform life-changing decisions. Not only does test anxiety cause unpleasant physiological and psychological reactions in students, it has also been suggested that exams may underestimate the true academic ability of test-anxious students (Deffenbacher, 1978). This study examined two short, inexpensive interventions aimed to reduce these negative effects of test anxiety: expressive writing and an instructional intervention based on a similar intervention developed for stereotype threat (Johns et al., 2005). The current study did not find convincing support for either intervention. Neither expressive writing nor the instructional intervention reduced feelings of test anxiety (assessed via S-TAI scores) or improved exam scores, with Bayes factors indicating that the null hypothesis (i.e., no difference between scores after completing the intervention and control tasks) was much more likely than the alternative hypothesis. Most importantly, the two interventions did not reduce the detrimental effect of test anxiety on exam performance, even when we selected a sample of students who showed a strong test anxiety–exam score correlation or used the worry sub-component. Our conclusion is that expressive writing and an instructional intervention were not effective at addressing the impact of test anxiety in the present college class.

The main concern with the present study is that the relationship between students’ trait test anxiety and exam scores was weak. This suggests that, on average, students’ exam performance may not have been strongly influenced by their test anxiety in the course. Nevertheless, even though correlations were weak in the present study, they were not much lower than typical correlations between test anxiety and performance reported in large studies (r = −0.15 to −0.21; Chapell et al., 2005; Hembree, 1988; Schwarzer, 1990). After all, test anxiety is only one factor impacting students’ exam grades, and that relationship may be more complex than typically expected. Thus, it is important to consider other factors that can moderate the association between test anxiety and exam performance. For example, Culler and Holahan (1980) found that among students with high-test anxiety, better study habits were associated with higher test scores (see also Putwain & Daly, 2013, for impact of academic buoyancy; Rozek et al., 2019, for socioeconomic status).

One may wonder whether the weaker correlation between test anxiety and exam performance relative to some other studies (e.g., Ramirez & Beilock, 2011) was due to students in the cognitive psychology course experiencing lower test anxiety. We do not believe this is the case because our T-TAI scores were similar to other normative scores (Szafranski et al., 2010). Thus, the students in our samples appeared to experience similar levels of both trait- and state-level test anxiety to other large samples of college students with sufficient variability and a relatively normal distribution. We also conducted multiple analyses to determine whether the interventions impacted some students more than others. First, we examined whether our interventions improved exam performance for only participants who reported higher-than-average test anxiety. Second, we conducted analyses using students’ worry scores from the T-TAI subscale, which was more strongly correlated with exam performance than the overall T-TAI score which also includes an emotionality subscale (see Chapell et al., 2005; Hembree, 1988). Third, we determined whether the impacts of the interventions depended on students’ WMC (see supplemental materials). Lastly, we used multiverse analysis logic to conduct exploratory analyses in which we constrained our analysis to only a sample of participants who displayed a strong correlation between test anxiety and exam performance (i.e., higher test anxiety was associated with lower exam scores). All analyses converged on the same conclusion: the interventions (1) did not improve exam performance and (2) did not reduce the test anxiety–exam performance relationship.

It might also be argued that we have merely shown that an expressive-writing intervention and an instructional intervention were ineffective in a college-level cognitive psychology class taught at a large public university. This criticism is certainly justified given that we had only tested our intervention in this setting (although this is an argument that can be leveled at most studies), but it is important to note several positive aspects of the present experiments in terms of both internal and external validity. First, these experiments were conducted in an authentic college classroom, students were taking exams with real stakes, and their measured test anxiety was consistent with established norms. All of these conditions are precisely where educational researchers would want to test these interventions. Second, both of our experiments were well-powered and included much larger sample sizes than some previous studies, particularly in the classroom environment. Third, as we will discuss below, a number of other well-powered studies have also failed to demonstrate an effect with these and similar interventions.

Although our results were dissimilar to Ramirez and Beilock’s (2011), they are consistent with other studies that have also found no benefit of expressive writing for test anxiety (Allen, 2017; Blank-Spadoni, 2013; Camerer et al., 2018; Sefton, 2014; Spielberger, 2015; Walter, 2018). Thus, it appears that the benefits of expressive writing remain mixed, and this intervention might not be effective in all situations. In the present study, the intervention might not have been effective because students were not given enough time to expressively write. However, our time limit of eight minutes for expressive writing was comparable to other studies – Ramirez and Beilock (2011) gave participants ten minutes, and Park et al. (2014) gave participants seven minutes. Therefore, we do not believe that the short writing duration was responsible for our null effect. Nevertheless, there may be other methodological differences between the studies that could account for why expressive writing appears beneficial in some studies but not in others.

We also did not find a benefit for the instructional intervention, in which students read about causes and treatments of test anxiety. This was a novel intervention that had not previously been used to address test anxiety. Although it was developed based on a similar intervention to reduce the effects of stereotype threat (Johns et al., 2005) and both stereotype threat and test anxiety effects have been proposed to occur due to the same cognitive mechanisms, there could be key differences between stereotype threat and test anxiety which caused the interventions to have differing effects. Importantly, some studies indicate that an instructional intervention reduced stereotype threat effects because it allows students to attribute their stress to an external source, specifically social pressure to disprove the stereotype (Ben-Zeev et al., 2005; Johns et al., 2005; McGlone & Aronson, 2007). This social component might be less applicable to test anxiety. Consequently, learning about the causes and effects of test anxiety may ironically lead students to judge themselves for experiencing this anxiety rather than attributing their test anxiety to an outside source. Another possibility raised is that the impacts of the instructional intervention may depend on students’ motivation toward cognitive psychology. Stereotype threat research has shown that those most impacted by stereotype threat are ones who strongly feel that the test domain is important to them (e.g., women who want to do well in math; Spencer et al., 1999; Steele, 1997). Thus, it is possible that not all students in the present study found cognitive psychology important to their own identity. Nevertheless, we believe that the pressure students experienced in this authentic exam environment was likely to be as least as strong, if not stronger, than what participants would have experienced in a laboratory-based environment, given that students in the present study were taking a course that contributes to their college GPA. Moreover, it might be argued that the conditions of our experiments are exactly those that we wish the interventions to have a positive impact.

However, it is also important to note that some studies have not replicated the benefits of the instructional intervention developed by Johns et al. (2005) for reducing stereotype threat (Rivardo, Rhodes, Camaione, & Legg, 2011; see also Fuller, 2013). We could identify no systematic differences between studies that would account for these diverging results. Therefore, it is possible that instructional interventions are also not effective in all circumstances. In a meta-analysis of stereotype threat interventions, Liu, Liu, Wang, and Zhang (2020) found a moderate effect of reappraisal interventions (including the intervention used by Johns et al., 2005), but they noted that the studies were impacted by publication bias and thus may overestimate effect sizes. Most importantly, not all stereotype threat interventions appear to work in every context (e.g., Rivardo et al., 2011).

Conclusions and practical implications

Based on the present results, we cannot recommend the use of expressive writing or instructional essays as blanket interventions to reduce the effects of test anxiety among all college students. At the very least, the putative benefits of these interventions do not apply in all educational settings, and future research is needed to clarify what factors might moderate the relationship between these interventions, test anxiety and exam performance.

We end with a few recommendations about exams and test anxiety in the classroom. Given the negative effects of test anxiety, educators and policy-makers may argue for the removal of exams from curricula (see e.g., Buck, Ritter, Jensen, & Rose, 2010). However, this would not be the best solution for students; tests are not only a means of assessment but importantly are also a learning tool for students. Indeed, test taking, which requires memory retrieval, is a well-supported method to improve students’ long-term retention of the tested material and to learn new material (for reviews, see Chan, Meissner, & Davis, 2018; Rowland, 2014). More experience with retrieval practice has even been shown to reduce students’ feelings of test anxiety (Agarwal, D’Antonio, Roediger, McDermott, & McDaniel, 2014; see also Yang et al., 2020). Thus, we encourage educators to keep testing students within their classrooms. However, the negative impacts of test anxiety on some students’ performance should be considered when using exam performance to make life-changing decisions. As mentioned previously, exam performance often underestimates test-anxious students’ true ability. Thus, it is essential that decisions are made using a holistic approach of the student rather than any one test score (for other recommendations, see Zeidner, 2007).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available at https://osf.io/x5w8z/?view_only=979ade23442544a4bf0fba26420db517.

Notes

Note that these findings differ from interactions between WMC and math anxiety (see Beilock & Ramirez, 2011).

Note that Johns et al. referred to their intervention as a “teaching intervention.” We opted for the term “instructional intervention” because we thought a “teaching intervention” might lead some to believe that participants were asked to teach someone else, rather than being taught something.

The effect size is from the high anxiety students (based on a median split) from Ramirez and Beilock’s (2011) Experiments 3 and 4, during which students completed a biology exam. We opted to use these experiments because they were conducted in a classroom setting whereas Ramirez and Beilock’s other experiments were completed in a laboratory. The power analysis was conducted by dividing our sample size by 2 to match the median split design from Ramirez and Beilock (2011).

Students could earn the same amount of extra credit by reading a research article and completing a short quiz.

Note that the S-TAI does not include the same subscales (i.e., Worry, Emotionality) as the T-TAI.

Due to loss of data, 14 students’ writing tasks from the first semester were not available to analyze in the LIWC software.

Results did not differ when the data from Exams 4 and 5 were included.

To our knowledge, Bayes factors cannot be calculated for z-tests.

One might wonder why the correlations between the T-TAI and exam scores were substantially weaker when considering the data for Exams 2 and 3 than Exam 1. This is to be expected because the strong correlation between T-TAI and exam scores was produced based on the ranked scores of Exam 1. Therefore, the weaker correlations between T-TAI and exam scores under the control-writing and expressive-writing conditions relative to the Exam 1 baseline should not be taken as evidence that either control or expressive writing served to weaken the impact of test anxiety on exam performance.

The effect size is estimated by calculating the difference in effect size of gender between participants in the math test condition (i.e., participants under stereotype threat) and the teaching intervention condition (i.e., participants read a brief paragraph about stereotype threat). Johns et al. (2005) did not report the effect size for participants in the teaching intervention condition, so we used their reported means and standard errors from the figure to estimate the effect size in this condition based on the assumption that they had the same number of participants across the math test and teaching intervention condition (sample size was needed to estimate the standard deviation).

Results did not differ when data from Exam 3 and 4 were included.

References

Agarwal, P. K., D’Antonio, L., Roediger, H. L., III., McDermott, K. B., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Classroom-based programs of retrieval practice reduce middle school and high school students’ test anxiety. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3(3), 131–139.

Allen, E. (2017). Exploring Expressive Writing to Reduce Test Anxiety on an Introductory Psychology Exam. (Undergraduate thesis). Retrieved from https://kb.osu.edu/handle/1811/80696.

Alparone, F. R., Pagliaro, S., & Rizzo, I. (2015). The words to tell their own pain: Linguistic markers of cognitive reappraisal in mediating benefits of expressive writing. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(6), 495–507.

Alpert, R., & Haber, R. N. (1960). Anxiety in academic achievement situations. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 61(2), 207–215.

Ansari, T. L., & Derakshan, N. (2011a). The neural correlates of cognitive effort in anxiety: Effects on processing efficiency. Biological Psychology, 86(3), 337–348.

Ansari, T. L., & Derakshan, N. (2011b). The neural correlates of impaired inhibitory control in anxiety. Neuropsychologia, 49(5), 1146–1153.

Appel, M., & Kronberger, N. (2012). Stereotypes and the achievement gap: Stereotype threat prior to test taking. Educational Psychology Review, 24(4), 609–635.

Beilock, S. L. (2008). Math performance in stressful situations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(5), 339–343.

Beilock, S. L., & Ramirez, G. (2011). On the interplay of emotion and cognitive control: Implications for enhancing academic achievement. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 55, 137–169.

Ben-Zeev, T., Fein, S., & Inzlicht, M. (2005). Arousal and stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(2), 174–181.

Blank-Spadoni, N. (2013). Writing about worries as an intervention for test anxiety in undergraduates. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Bonaccio, S., Reeve, C. L., & Winford, E. C. (2012). Test anxiety on cognitive ability test can result in differential predictive validity of academic performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(4), 497–502.

Buck, S., Ritter, G. W., Jensen, N. C., & Rose, C. P. (2010). Teachers say the most interesting things: An alternative view of testing. Phi Delta Kappan, 91, 50–54.

Calvo, M. G., & Eysenck, M. W. (1998). Cognitive bias to internal sources of information in anxiety. International Journal of Psychology, 33(4), 287–299.

Camerer, C. F., Dreber, A., Holzmeister, F., Ho, T. H., Huber, J., Johannesson, M., & Altmejd, A. (2018). Evaluating the replicability of social science experiments in Nature and Science between 2010 and 2015. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(9), 637–644.

Chalkia, A., Schroyens, N., Leng, L., Vanhasbroeck, N., Zenses, A. K., Van Oudenhove, L., & Beckers, T. (2020a). No persistent attenuation of fear memories in humans: A registered replication of the reactivation-extinction effect. Cortex, 129, 496–509.

Chalkia, A., Van Oudenhove, L., & Beckers, T. (2020b). Preventing the return of fear in humans using reconsolidation update mechanisms: A verification report of Schiller et al. (2010). Cortex, 129, 510–525.

Chan, J. C. K., Meissner, C. A., & Davis, S. D. (2018). Retrieval potentiates new learning: A theoretical and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 144(11), 1111–1146.

Chapell, M. S., Blanding, Z. B., Silverstein, M. E., Takahashi, M., Newman, B., Gubi, A., & McCann, N. (2005). Test anxiety and academic performance in undergraduate and graduate students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(2), 268–274.

Cizek, G. J., & Burg, S. S. (2006). Addressing test anxiety in a high-stakes environment: Strategies for classrooms and schools. Corwin Press.

Clinton, V., & Meester, S. (2019). A comparison of two in-class anxiety reduction exercises before a final exam. Teaching of Psychology, 46(1), 92–95.

Craik, F. I. M. (1986). A functional account of age differences in memory. In F. Klix & H. Hagendorf (Eds.), Human memory and cognitive capabilities (pp. 409–422). Elsevier.

Culler, R. E., & Holahan, C. J. (1980). Test anxiety and academic performance: The effects of study-related behaviors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(1), 16–20.

Deffenbacher, J. L. (1978). Worry, emotionality, and task-generated interference in test anxiety: An empirical test of attentional theory. Journal of Educational Psychology, 70(2), 248.

Elliot, A. J., & Murayama, K. (2008). On the measurement of achievement goals: Critique, illustration, and application. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 613–628.

Ergene, T. (2003). Effective interventions on test anxiety reduction: A meta-analysis. School Psychology International, 24(3), 313–328.

Eysenck, M. W., & Calvo, M. G. (1992). Anxiety and performance: The processing efficiency theory. Cognition & Emotion, 6(6), 409–434.

Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336–353.

Flore, P. C., & Wicherts, J. M. (2015). Does stereotype threat influence performance of girls in stereotyped domains? A Meta-Analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 53(1), 25–44.

Frattaroli, J., Thomas, M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2011). Opening up in the classroom: Effects of expressive writing on graduate school entrance exam performance. Emotion, 11(3), 691–696.

Fuller, N. (2013). Does teaching women about stereotype threat reduce its effects on math performance?. (Unpublished honors thesis). The College at Brockport, Brockport, NY.

Ganley, C. M., Conlon, R. A., McGraw, A. L., Barroso, C., & Geer, E. A. (2021). The Effect of Brief Anxiety Interventions on Reported Anxiety and Math Test Performance. Journal of Numerical Cognition, 7(1), 4–19.

Ganzer, V. J. (1968). Effects of audience presence and test anxiety on learning and retention in a serial learning situation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(2), 194–199.

Good, C., Aronson, J., & Inzlicht, M. (2003). Improving adolescents’ standardized test performance: An intervention to reduce the effects of stereotype threat. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24(6), 645–662.

Gortner, E. M., Rude, S. S., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2006). Benefits of expressive writing in lowering rumination and depressive symptoms. Behavior Therapy, 37(3), 292–303.

Hancock, D. R. (2001). Effects of test anxiety and evaluative threat on students’ achievement and motivation. The Journal of Educational Research, 94(5), 284–290.

Harris, R. B., Grunspan, D. Z., Pelch, M. A., Fernandes, G., Ramirez, G., & Freeman, S. (2019). Can test anxiety interventions alleviate a gender gap in an undergraduate STEM course? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 18(3), 1–9.

Hembree, R. (1988). Correlates, causes, effects, and treatment of test anxiety. Review of Educational Research, 58(1), 47–77.

Hill, K. T., & Wigfield, A. (1984). Test anxiety: A major educational problem and what can be done about it. The Elementary School Journal, 85(1), 105–126.

Hines, C. L., Brown, N. W., & Myran, S. (2016). The effects of expressive writing on general and mathematics anxiety for a sample of high school students. Education, 137(1), 39–45.

Johns, M., Inzlicht, M., & Schmader, T. (2008). Stereotype threat and executive resource depletion: Examining the influence of emotion regulation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 137(4), 691–705.

Johns, M., Schmader, T., & Martens, A. (2005). Knowing is half the battle: Teaching stereotype threat as a means of improving women’s math performance. Psychological Science, 16, 175–179.

Joormann, J., & Tran, T. B. (2009). Rumination and intentional forgetting of emotional material. Cognition and Emotion, 23(6), 1233–1246.

Kellogg, R. T., Mertz, H. K., & Morgan, M. (2010). Do gains in working memory capacity explain the written self-disclosure effect? Cognition and Emotion, 24(1), 86–93.

Klein, K., & Boals, A. (2001). Expressive writing can increase working memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(3), 520–533.

Kruschke, J. K. (2013). Bayesian estimation supersedes the t test. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(2), 573–603.

Lepore, S. J. (1997). Expressive writing moderates the relation between intrusive thoughts and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(5), 1030–1037.

Liebert, R. M., & Morris, L. W. (1967). Cognitive and emotional components of test anxiety: A distinction and some initial data. Psychological Reports, 20(3), 975–978.

Liu, S., Liu, P., Wang, M., & Zhang, B. (2020). Effectiveness of stereotype threat interventions: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000770

Lumley, M. A., & Provenzano, K. M. (2003). Stress management through written emotional disclosure improves academic performance among college students with physical symptoms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(3), 641–649.

McGlone, M. S., & Aronson, J. (2007). Forewarning and forearming stereotype-threatened students. Communication Education, 56(2), 119–133.

Meijer, J. (2001). Learning potential and anxious tendency: Test anxiety as a bias factor in educational testing. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 14(3), 337–362.

Moran, T. P. (2016). Anxiety and working memory capacity: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 142(8), 1–34.

Owens, M., Stevenson, J., Hadwin, J. A., & Norgate, R. (2014). When does anxiety help or hinder cognitive test performance? The role of working memory capacity. British Journal of Psychology, 105(1), 92–101.

Park, D., Ramirez, G., & Beilock, S. L. (2014). The role of expressive writing in math anxiety. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 20(2), 103–111.

Pennebaker, J. W., Booth, R. J., & Francis, M. E. (2007). Linguistic inquiry and word count: LIWC [Computer software]. Austin, TX: liwc. net, 135.

Pennebaker, J. W., & Francis, M. E. (1996). Cognitive, emotional, and language processes in disclosure. Cognition & Emotion, 10(6), 601–626.

Pennebaker, J. W., & Seagal, J. D. (1999). Forming a story: The health benefits of narrative. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55(10), 1243–1254.

Putwain, D. W., & Daly, A. L. (2013). Do clusters of test anxiety and academic buoyancy differentially predict academic performance? Learning and Individual Differences, 27, 157–162.

Ramirez, G., & Beilock, S. L. (2011). Writing about testing worries boosts exam performance in the classroom. Science, 331, 211–213.

Relojo-Howell, D., & Stoyanova, S. (2019). Expressive writing as an anxiety-reduction intervention on test anxiety and the mediating role of first language and self-criticism in a Bulgarian sample. Journal of Educational Sciences & Psychology, 9(1), 121–130.

Rivardo, M. G., Rhodes, M. E., Camaione, T. C., & Legg, J. M. (2011). Stereotype threat leads to reduction in number of math problems women attempt. North American Journal of Psychology, 13(1), 5–16.

Rocklin, T., & Thompson, J. M. (1985). Interactive effects of test anxiety, test difficulty, and feedback. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(3), 368–372.

Rouder, J. N., Speckman, P. L., Sun, D., Morey, R. D., & Iverson, G. (2009). Bayesian t tests for accepting and rejecting the null hypothesis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16(2), 225–237.

Rowland, C. A. (2014). The effect of testing versus restudy on retention: A meta-analytic review of the testing effect. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1–32.

Rozek, C. S., Ramirez, G., Fine, R. D., & Beilock, S. L. (2019). Reducing socioeconomic disparities in the STEM pipeline through student emotion regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(5), 1553–1558.

Sarason, I. G. (1972). Experimental approaches to test anxiety: Attention and the uses of information. Anxiety: Current Trends in Theory and Research, 2, 383–403.

Sarason, I. G. (1973). Test anxiety and cognitive modeling. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28(1), 58.

Sarason, I. G. (1980). Test anxiety: Theory, research, and applications. Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc Inc.

Sarason, S. B. (1974). The psychological sense of community: Prospects for a community psychology. Jossey-Bass.

Schmader, T., Johns, M., & Forbes, C. (2008). An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychological Review, 115(2), 336–356.

Schroder, H. S., Moran, T. P., & Moser, J. S. (2018). The effect of expressive writing on the error‐related negativity among individuals with chronic worry. Psychophysiology, 55(2), e12990.

Schwarzer, R. (1990). Current trends in anxiety research. European Perspectives in Psychology, 2, 225–244.

Sefton, R. E. (2014). A Study of Underprepared College Algebra Students and Test Anxiety: The Impact of Using Expressive Writing on Test Performance. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://jewlscholar.mtsu.edu/bitstream/handle/mtsu/4286/ Sefton_mtsu_0170E_10278.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Seipp, B. (1991). Anxiety and academic performance: A meta-analysis of findings. Anxiety Research, 4(1), 27–41.

Shen, L., Yang, L., Zhang, J., & Zhang, M. (2018). Benefits of expressive writing in reducing test anxiety: A randomized controlled trial in Chinese samples. PLoS ONE, 13(2), 1–15.

Smyth, J. M., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2008). Exploring the boundary conditions of expressive writing: In search of the right recipe. British Journal of Health Psychology, 13(1), 1–7.

Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(1), 4–28.

Spielberger, C. D. (1966). Theory and research on anxiety. Anxiety and behavior, 1(3).

Spielberger, C. D. (1980). Test anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Spielberger, C. D., Anton, W. D., & Bedell, J. (1976). The nature and treatment of test anxiety. In M. Zuckerman, & CD Spielberger. Emotion and anxiety: New concepts, methods and applications.

Spielberger, S. L. (2015). Effects of an expressive writing intervention aimed at improving academic performance by reducing test anxiety. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY.

Steegen, S., Tuerlinckx, F., Gelman, A., & Vanpaemel, W. (2016). Increasing transparency through a multiverse analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(5), 702–712.

Steele, C. M. (1998). Stereotyping and its threat are real. American Psychologist, 53(6), 680–681.

Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2012). Can stereotype threat explain the gender gap in mathematics performance and achievement? Review of General Psychology, 16(1), 93–102.

Stricker, L. J., & Ward, W. C. (2004). Stereotype threat, inquiring about test takers’ ethnicity and gender, and standardized test performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(4), 665–693.

Szafranski, D. D., Barrera, T. L., & Norton, P. J. (2012). Test anxiety inventory: 30 years later. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 25(6), 667–677.

Tomasetto, C., & Appoloni, S. (2013). A lesson not to be learned? Understanding stereotype threat does not protect women from stereotype threat. Social Psychology of Education, 16(2), 199–213.

Tse, C. S., & Pu, X. (2012). The effectiveness of test-enhanced learning depends on trait test anxiety and working-memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 18(3), 253–264.

Unsworth, N., & Engle, R. W. (2007). The nature of individual differences in working memory capacity: Active maintenance in primary memory and controlled search from secondary memory. Psychological Review, 114(1), 104–132.

Van Emmerik, A. A., Kamphuis, J. H., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2008). Treating acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with cognitive behavioral therapy or structured writing therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 77(2), 93–100.

Von Der Embse, N., Barterian, J., & Segool, N. (2013). Test anxiety interventions for children and adolescents: A systematic review of treatment studies from 2000–2010. Psychology in the Schools, 50(1), 57–71.

Walter, H. (2018). The effect of expressive writing on second-grade math achievement and Math anxiety (Unpublished dissertation). George Fox University, Newburg, OR.

Wheeler, S. C., & Petty, R. E. (2001). The effects of stereotype activation on behavior: A review of possible mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 127(6), 797–826.

Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B., & Telch, M. J. (2010). Efficacy of self-administered treatments for pathological academic worry: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(9), 840–850.

Woodworth, R. S. (1938). Experimental psychology. Holt.

Yang, C., Sun, B., Potts, R., Yu, R., Luo, L., & Shanks, D. R. (2020). Do working memory capacity and test anxiety modulate the beneficial effects of testing on new learning?. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied.

Zeidner, M. (1998). Test anxiety: The state of the art. Plenum.

Zeidner, M. (1990). Does test anxiety bias scholastic aptitude test performance by gender and sociocultural group?. Journal of Personality Assessment, 55(1–2), 145–160.

Zeidner, M. (2007). Test anxiety in educational contexts: Concepts, findings, and future directions. In Emotion in Education (pp. 165–184). Academic Press.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.