Abstract

Background

Supplementation with iron and folic acid (IFA) is recommended to prevent anaemia in pregnancy. However, the effectiveness of the supplementation in improving haemoglobin level depends on the degree of compliance. It is therefore necessary to periodically assess level of compliance with IFA supplementation. The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and factors associated with compliance to IFA supplementation in pregnancy in Tamale Metropolis, Ghana.

Methods

A health facility–based cross-sectional study was conducted among 403 pregnant women who accessed antenatal clinic (ANC) services in three health facilities in Tamale Metropolis, Ghana. Simple random sampling was used to select study health facilities and participants. Compliance to IFA was defined as use of IFA supplement in 4 of the last 7 days. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify the determinants of IFA supplementation compliance.

Results

The mean age of the study population was 26.7 (± 4.18) years. The prevalence of compliance to IFA supplementation was 58.8% (215/403) and the main reason the women gave for non-compliance was forgetting to take the supplements (40.9%). Following multivariate analysis, factors that were significantly associated with compliance were pregnancy trimester at interview, educational level, IFA knowledge, sex of household head and household wealth index.

Conclusion

About 3 out of 5 women seeking ANC services in Tamale Metropolis are compliant with IFA supplementation with some of their socio-demographic and household characteristics predicting compliance. Efforts to increase compliance to IFA supplementation must focus on education on its benefits and improvement of socio-economic status of women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Iron and folic acid (IFA) are essential micronutrients for normal physiological function, growth, development and maintenance of life [1] whose demand increases during pregnancy creating a need for supplementation [2]. It is estimated that 56% of women in sub-Saharan Africa are anaemic [3]. The prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women in Ghana was estimated at 54% in 2013 [3] and 45% in 2014 according to the latest Demographic and Health Survey [4]. Pregnancy-related anaemia ranks highest among the leading causes of global health burden [5] with more than half attributed to iron deficiency. Anaemia in pregnancy affects the results of pregnancy negatively and increases the risk of both maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality [6].

Some public health interventions are being implemented in Africa to tackle the root causes of iron deficiency and anaemia including IFA supplementation, malaria prevention and deworming [7]. With IFA supplementation, the WHO recommends a standard dose of 60 mg iron and 400 μg folic acid daily to be taken during pregnancy at places where iron deficiency anaemia prevalence is above 40% [8]. Ghana has adopted this recommendation and a combined formulation of iron and folic acid (combo) supplement is indicated for pregnant women from the first antenatal clinic (ANC) visit to delivery and in the first 6 weeks postpartum [9]. The cost of the IFA supplementation is covered by the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) and pregnant women who hold valid NHIS cards do not pay for it. However, whenever health facilities are out of stock of the combined formulation, they give iron and folic acid supplements separately or only one of these depending on what is available and ask the women to purchase the other from a pharmacy.

Compliance with a medication regimen is generally defined as the extent to which patients take medications as prescribed by their health care providers. Compliance to IFA supplementation among pregnant women for survey purposes is defined as the intake of supplements for at least 4 days within the most recent week [10]. The proportion of women complying with the supplementation are however much lower especially in low- and middle-income countries, and that hinders anaemia prevention [11]. In Ghana, compliance with IFA supplementation was estimated at 66.2% [12] in Upper East Region and that of folic acid at 63% in Northern Region [13]. Compliance with IFA supplementation was low (26.2%) among Junior High School adolescent girls in the Metropolis [14]. Nationally, the proportion of women who took daily iron supplements for 90 or more days during their last pregnancy were 59.4% [4]. Elsewhere in Africa, the prevalence of compliance to IFA was reported as 32.7% in Kenya [1], 55.3% in Ethiopia [15], 58.0% in Dakar [16] and 65.9% in Nigeria [17]. In these studies, factors associated with compliance to IFA supplementation were knowledge on IFA supplementation, awareness on anaemia, knowledge of relationship between anaemia and IFA supplementation [1], motivation of the midwife, health benefits of IFA supplementation, fear of being sick [16], counselling, early ANC attendance, multipara and current anaemia history [18]. On the other hand, gastrointestinal side effect, inability to purchase the supplements and forgetfulness were associated with non-compliance [17].

Maternal IFA supplementation has been shown to reduce maternal anaemia [19] and, consequently, maternal mortality, new-born mortality and poor birth outcomes such as low birth weight [20] and congenital anomalies [21]. However, the effectiveness of the IFA supplementation in increasing haemoglobin level depends on the level of compliance [22]. Thus, it is important to regularly review the level of compliance and assess the factors associated with it in order to inform prevention and treatment policies and procedures. The main aim of this study was to determine the level of compliance to IFA supplementation among pregnant women receiving antenatal clinic (ANC) services and identify the factors associated with it in Tamale Metropolis, Ghana.

Methods

Study design and area

A health facility–based cross-sectional study was conducted in Tamale Metropolis in Northern region of Ghana. The Metropolis is located in the central part of the region and shares boundaries with Sagnarigu district to the west and north, Mion district to the east and East Gonja to the south-west and north. The Metropolis has a total land size of 646.9018 km2 [23].

The population of Tamale Metropolis, according to the 2010 population and housing census, is 233,252 representing 9.4% of the region’s population. This comprises of 49.7% males and 50.3% females. A greater proportion of the inhabitants (80.8%) live in urban localities. The study was carried out in 3 out of 4 health facilities: Central Hospital, Reproductive and Child Health Clinic and Seventh Day Adventist Hospital located around the central business district of the city. These health facilities provide ANC services that are covered by NHIS making them the first point of call for pregnant women within the Metropolis. The Central Hospital serves as a secondary level service point [24].

Study population

The population for this study was pregnant women at any gestational age attending ANC in the 3 selected health facilities in the Tamale Metropolis during the period of the study.

Sample size determination and sampling

Using the formula for estimating sample size for single population proportion [25], prevalence of compliance to IFA supplementation of 50% (p), margin of error allowed (ME) of 5% and the z-score of the 95% confidence level 1.96 (z), a sample size of 384 was estimated. Five percent (5%) of the estimated sample size was added to obtain the final sample size used for the study (403). The subjects were selected from 3 randomly selected health facilities out of 4 around the central business district of the Metropolis using lottery method. The names of the 4 health facilities were written on pieces of paper, folded and placed in a basket. The health facilities whose names were written on 3 randomly drawn out folded papers were used for the study. Probability proportional to size was used to select the number of respondents from each health facility using the total ANC attendance in the previous month. Proportions of 40.9% (165/403), 28.5% (115/403) and 30.5% (123/403) of the total sample size were taken from Central Hospital, Reproductive and Child Health Clinic and Seventh Day Adventist Hospital respectively.

Pregnant women attending ANCs were selected for inclusion using simple random sampling technique by applying the lottery method. The number of women to be recruited on a given day at a health facility was pre-determined. The words “Yes” (corresponding to the number of women to select on a day) and “No” were written on pieces of paper, folded and mixed in a box. The women were asked to pick one piece of paper from the box without replacement and those who selected “Yes” were recruited into the study and interviewed.

Questionnaire

Data collection made use of an investigator-assembled questionnaire. The questionnaire included modules on socio-demographic and economic characteristics (30 items), IFA supplementation (12 items), knowledge on IFA (3 items) and knowledge on anaemia (18 items). The module on socio-demographic and economic characteristics of the women included questions on age, highest educational level, occupation, religion, ethnicity, number of household members, number of children, sex of household head, building material of house and sources of water, lighting and cooking fuel and possession of household items used to construct household wealth index. The rest of the variables were trimester of first ANC visit, gestational age/trimester of pregnancy at interview and whether the pregnancy was the first one. IFA supplementation and knowledge module consisted of questions on whether they received IFA, type of supplements received, number of days supplement was taken in the last 7 days prior to survey, reasons for non-compliance and the benefits of IFA. The module on anaemia knowledge had questions on definition, causes, symptoms and preventive measures of anaemia. The questions on knowledge on IFA and anaemia were put together in English in a focus group discussion by a team of ANC nurses conversant with nutrition education at ANCs in Ghana. Potential determinants of compliance to IFA supplementation were identified in a review of similar studies [1, 16,17,18, 26, 27].

The questionnaire was culturally validated as it underwent double translation from English to Dagbani and back to English and face-validated through pretesting with pregnant women in another ANC who were satisfied that the questions could adequately measure their iron, folic acid and anaemia knowledge. Also, during the pretesting, questions that were ambiguous were rephrased to convey the intended information.

Data collection procedures

Data were collected in May, 2019, at ANCs of the three health facilities using face-to-face interviews conducted by enumerators. The data for the determination of compliance to supplementation was collected by asking the women to recall the number of days they took the IFA supplement in the last 7 days prior to the interview. Data collection was done by 3 final year students and 2 lecturers of the Department of Nutritional Sciences, University for Development Studies (UDS), Tamale, Ghana.

Quality control

A 2-day training was given to data collectors and their supervisors. During the training, the enumerators learnt the meanings of the questions and practiced how to ask them. The training also covered informed consent procedures, sampling technique and interviewing skills. There was an opportunity to pre-test the questionnaire administration before the actual survey. During the course of data collection, the completed questionnaires were checked by the supervisors for completeness on site on daily basis and the problems identified were rectified.

Data analysis

Compliance to IFA supplementation

Compliance was defined as the intake of IFA supplements (i.e. IFA combo, or both iron and folic acid) in 4 of the last 7 days [10]. This was the main outcome indicator of the study.

Knowledge on IFA index

This examined the knowledge of the women on the importance of the IFA supplement such as prevention of maternal anaemia, promoting improved pregnancy outcomes and prevention of neural tube defects in unborn baby. Each correct response was awarded a score of “1,” otherwise a score of “0”. The summary score therefore ranges from 0 to 3 depending on the number of correct responses provided since there were 3 items. All the responses were then summed up and the average used to categorise the index into two halves. Women who obtained less than the mean score (1.28) were classified into low category and those who had the mean score or above were put into high category.

Knowledge on anaemia index

To ascertain the pregnant women’s knowledge on anaemia, 17 questions were asked on the definition, causes, signs and symptoms and preventive measures of anaemia including 7 true or false questions. For each correct response, they were awarded a score of “1,” otherwise a score of “0”. The overall score ranges from 0 to 17 depending on the number of correct responses. The scores were then summed up and the mean score (6.42) used to divide index into two halves low and high.

Household wealth index

A household wealth index was generated and used as a proxy indicator for socio-economic status (SES) of the women. This is based on an earlier concept whereby the sum of dummy variables created from information collected on household assets and housing quality was used to construct an index [28]. The 14 variables used were the following: radio set, television set, satellite dish, sewing machine, mattress, refrigerator, DVD player, computer, fan, mobile phone, bicycle, motorcycle, animal drawn cart and car. A household was awarded a score of “1” for each item possessed, otherwise a score of “0”. Each item was counted only once irrespective of the number the household possessed. Principal component analysis was used to generate a household wealth index score which was then ranked and divided into three categories (tertile).

Data entry and management was done using SPSS. For continuous data, means and standard deviations were computed and frequencies and percentages were used for categorical data. Descriptive statistics were used to display the distribution of both the dependent and independent variables. The factors associated with compliance to IFA supplementation in pregnancy were determined using Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression modelling. Bivariate tests were conducted and all significant factors were entered in a multivariate logistic regression model. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) was calculated to check strength of association between compliance and its determinants. In the analyses, a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Multicollinearity among the exposure variables was checked using variance inflation factor which was below 2 for all the exposure variables indicating there were no problems with multicollinearity. Model fit was checked using log likelihood Chi-square test and Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test; both of which showed that the model fitted the data well.

Ethics approval

The study protocol (Number 04-2018) was approved by the Joint Ethics Board of School of Medicine and Health Sciences and School of Allied Health Sciences, UDS, Tamale, Ghana.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from pregnant women before the administration of the questionnaire. The women were also assured of anonymity and confidentiality of the data being provided. As such, no person identifiable information was collected, and data collected were stored on password-protected computer and accessed only by members of the research team. The women were also informed that participation in the study was voluntary and those who did not want to participate were at liberty to decline the invitation to participate.

Results

Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of respondents

The mean age of the women was 26.7 (± 4.18) years with 43.2% of them within the age range 25–29 years (Table 1). Almost all the women were either married or cohabiting (88.3%); Dagomba (64.5%) was the predominated ethnicity and 26.6% of the respondents had completed Senior High/Vocational school. Trading (42.7%) was the predominant occupation among the women. More than half (56.1%) of the women had been pregnant before and majority (48.4%) were in their second trimester of pregnancy. Most women (77.4%) visited the ANC within the first trimester of pregnancy. More than half (52.1%) of the women had given birth to 1–3 children with 43.7% from households with 1–5 members. Majority of the women drank pipe-borne water (81.6%), dwelled in houses made of blocks (87.8%) and used electricity as main source of lighting (97.5%). About half of the women (54.8%) used charcoal as their main source of cooking fuel and a third (33.7%) belonged to the poorest tertile of household wealth index.

Iron and folic acid supplementation and knowledge of respondents

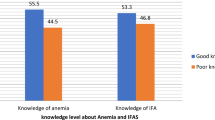

Majority (98.3%) of the women were given the IFA supplements with 79.8% receiving both iron and folic acid and 3.7% receiving iron-folic acid combo (Table 2). About a fifth of the women (18.1%) received only iron or folic acid. The prevalence of compliance with IFA supplementation was found to be 58.8%. Forgetfulness (40.9%) was the major reason for non-compliance among the women and 24.1% of the women cited experience of side effects. The study also found that 72.5% and 35.7% of the women reported perception of improved pregnancy outcome and prevention of anaemia as benefits of supplementation respectively. Four in ten women (39.5%) were classified as having high knowledge on IFA.

Anaemia knowledge of respondents

About half (55.3%) of pregnant women knew what anaemia was (Table 3). Among this group, 75.8% reported that poor iron-rich food intake was the cause of anaemia, and 72.6% reported that tiredness and weakness were the main symptoms of anaemia. With the true or false statements, more than 80% of the respondents identified 4 statements correctly with most of them (96.8%) acknowledging that “Good nutrition before conception is very important”. About half (48.0%) of the women were classified into the high category of knowledge on anaemia index.

Bivariate analysis of women’s factors associated with compliance to iron and folic acid supplementation

From Table 4, the women’s factors that were associated with compliance to IFA supplementation in bivariate analyses were as follows: religion (p = 0.032), educational level completed (p < 0.001), occupation (p = 0.005), pregnancy trimester at interview (p = 0.002), trimester of first ANC visit (p = 0.011), sex of household head (p = 0.002), number of household members (p = 0.001), household wealth index (p < 0.001) and knowledge on IFA (p < 0.001). Although the women’s knowledge on anaemia was also significantly related to their compliance level (p = 0.011), it was not included in the multivariate analysis because it correlates highly with knowledge on IFA.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with compliance to iron and folic acid supplementation

Following multivariate analysis, the following were the determinants of compliance to IFA supplementation: pregnancy trimester at time of interview, education, knowledge on IFA, sex of household head and household wealth index (Table 5). Women in the third trimester of pregnancy at the time of interview were about 4 times more likely to be compliant compared with those in first trimester (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 3.72; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.84–7.55; p < 0.001). Those whose highest educational level was primary were 5 times more likely to be compliant compared with those with tertiary level education (AOR 4.71; 95% CI 1.56–14.29; p = 0.006). On the contrary, women with low knowledge on IFA compared with those with high knowledge (AOR 0.42; 95% CI 0.25–0.70; p < 0.001), and those belonging to female-headed households compared with those belonging to male-headed households (AOR 0.36; 95% CI 0.17–0.77; p = 0.008) were less likely to be compliant. Similarly, women belonging to households classified as poorest (AOR 0.42; 95% CI 0.23–0.77; p = 0.006) or medium (AOR 0.40; 95% CI 0.22–0.74; p = 0.003) when compared with those from rich households were about 60% less likely to be compliant.

Discussion

This study sought to determine the level of compliance to IFA supplementation and identify its determinants among pregnant women receiving antenatal care in Tamale, Northern Ghana. The study determined that 58.8% of the women were compliant with IFA supplementation and identified the women’s socio-demographic and household factors associated with compliance to IFA supplementation.

Our finding suggests that a large majority of the women were given a supplement containing iron and folic acid, but about a fifth of these women were given only iron or folic acid and would therefore not derive the full benefit of the IFA supplementation. The possible reasons for this observation include unavailability of the supplements in health facilities and communities and lack of resources by clients to purchase the two supplements when the health facility is unable to supply them. The level of compliance to IFA supplementation in this study is similar to compliance rates in pregnant women in Northwest Ethiopia (55.3%) [15] and Dakar (58%) [16] but a bit lower than the rate for a population in Nigeria (65.9%) [17]. In Ghana, the rate measured in this study is lower than the IFA compliance rate (66.2%) reported for pregnant women in Upper East Region [12], and the folic acid compliance rate (63%) in Northern Region [13], but is similar to the compliance rate of iron nationally (59.4%) [4]. However, this rate is far bigger than the IFA compliance rate among Junior High School adolescent girls in the Tamale Metropolis (26.2%) [14]. Differences in the rates of compliance can be attributed to differences in levels of knowledge on anaemia, supply of tablets, utilisation of ANC services, ability to purchase supplements, knowledge on the benefits of IFA, experience of side effects, forgetfulness and poor counselling [29].

The study also pointed out some important key reasons why most pregnant women are not compliant to IFA supplementation. Majority of women reported forgetfulness of taking the tablets (40.9%) as one of the reasons for non-compliance. This can be a result of their busy schedules since majority of them engaged in trade as their main occupation. This finding was similar to the results of a study conducted in Enugu that reported forgetfulness as a barrier to compliance to iron supplementation by pregnant women [17]. The experience of side effects such as vomiting, nausea, dizziness and cramps also may have contributed to non-compliance as some women who experienced the side effects mentioned above stopped taking the supplements. A similar finding was reported by other authors [12, 17, 30]. It would therefore be necessary for staff of ANCs at the various health facilities to reassure the women that the side effects of IFA supplementation are not harmful to the foetus; therefore, they should not stop taking the supplements on account of them. Most women had misconceptions about the supplement causing the foetus to increase in size, thereby making it difficult to have a natural delivery. This finding can be attributed to the poor knowledge background of these women, hence the lack of knowledge on the benefits of the supplements. This misconception can be corrected if more education on the supplements and its benefits are stressed at ANCs. One study in Ethiopia also reported a similar finding in which 28.5% of women believed that continuous taking of IFA supplement in pregnancy leads to overweight babies [31]. Women also cited other reasons (i.e. exhausted all the supplements received) for non-compliance to IFA supplementation. Women whose supplements were finished but they had not been re-supplied during their visits to ANC have higher odds of non-compliance. It was then realised that some of the facilities ran out of the supplements and therefore had to prescribe for the women to buy from the open market which affected compliance as a result of financial constraints. This was similar to reports in Senegal that women who did not purchase the supplements for financial reasons were at an increased risk of non-compliance with IFA supplementation [16].

Multivariate analysis showed that the pregnant women’s trimester at interview, educational level and IFA knowledge are associated with compliance to IFA supplementation. We found that in the third trimester women have the highest odds of compliance. This may be explained that pregnant women in their third trimester have the highest risk of anaemia and may have been more compliant to avoid anaemia. It is also possible that, if they started ANC attendance in the first trimester, they would have been exposed to counselling and education on IFA supplementation for a long time and this would have improved their compliance. The study also found that education appears to improve compliance; however, those who had education up to the primary level have the highest odds of compliance. This finding does not agree with the result of a study in Garu-Tempane in Ghana which found the highest odds of compliance among women with education up to tertiary level [12]. Women who had low knowledge on IFA were less likely to be compliant. This finding is similar to the findings of a study in Dakar which reported that knowledge on the health benefits of IFA among women was among the factors that influenced compliance rate positively [16]. This reinforces the need to stress on the health benefits of the supplements during ANC in order to improve compliance.

Other factors associated with IFA supplement compliance are sex of household head and household wealth index. While we found that women from female-headed households are less likely to be compliant compared with women from male-headed households, it is not clear what the mechanism is. We found that women from socio-economically advantaged households had higher odds of compliance compared with those from poor households. Our finding of improved compliance with better socio-economic status of households was previously reported for women in sub-Saharan Africa [29].

The main limitation of this study is that the determination of compliance to IFA supplementation relied on recall data from the women which could not be verified or objectively measured. As with any survey relying on recall of events by the respondents, there is a possibility of under- or over-reporting. However, we are of the view that this research gives an overview of compliance to IFA level and its determinants in the Tamale Metropolis.

Conclusions

About 3 out of 5 pregnant women seeking ANC services in the Tamale Metropolis are compliant with IFA supplementation with some of their socio-demographic and household characteristics predicting compliance. We found that the women’s pregnancy trimester at interview, knowledge on IFA, educational level, sex of household head and household wealth index influence compliance. Efforts to increase compliance to IFA supplementation must focus on education on its benefits and improvement of socio-economic status of women.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal clinic

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- IFA:

-

Iron and folic acid

- NHIS:

-

National Health Insurance Scheme

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- UDS:

-

University for Development Studies

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Kamau MW, Mirie W, Kimani S. Compliance with iron and folic acid supplementation (IFAS) and associated factors among pregnant women: results from a cross-sectional study in Kiambu County, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):580.

Allen LH. Anemia and iron deficiency: effects on pregnancy outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(5):1280S–4S.

Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, Branca F, et al. Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995–2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(1):e16–25.

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), and ICF International: Ghana demographic and health survey 2014. Rockville, Maryland, USA: GSS, GHS, and ICF International; 2015.

Fiedler JL, D’Agostino A, Sununtnasuk C: Nutrition technical brief: A simple method for making a rapid, initial assessment of the consumption and distribution of iron-folic acid supplements among pregnant women in developing countries. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project; 2015.

Anlaakuu P, Anto F. Anaemia in pregnancy and associated factors: a cross sectional study of antenatal attendants at the Sunyani Municipal Hospital, Ghana. BMC research notes. 2017;10(1):402.

Patience D. Knowledge and perception of risk of anaemia during pregnancy among pregnant women in Ablekuma South. Accra: University of Ghana; 2016.

World Health Organization: WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva, Switzerland; World Health Organization; 2016.

Ghana Health Service, and SPRING/Ghana: Health Worker Training Manual for Anaemia Control in Ghana: Facilitators Guide. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project; 2017.

World Health Organisation. Guidance: daily iron and folic acid supplementation in pregnant women. Geneva, Swirtzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

Taye B AG, Mekonen A.: Factors associated with compliance of prenatal iron folate supplementation among women in Mecha district, Western Amhara: a cross sectional study. Pan Afr Med J 2015(20):7.

Minyila CA. Factors influencing compliance with iron supplements intake among pregnant women in the Garu-Tempane district of the upper east region. Accra: University of Ghana; 2018.

Mohammed BS, Helegbe GK. Routine haematinics and multivitamins: adherence and its association with haemoglobin level among pregnant women in an urban lower-middle-income country. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology: Ghana; 2020.

Dubik SD, Amegah KE, Alhassan A, Mornah LN, Fiagbe L: Compliance with weekly iron and folic acid supplementation and its associated factors among adolescent girls in Tamale Metropolis of Ghana. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2019, 2019.

Birhanu TM, Birarra MK, Mekonnen FA. Compliance to iron and folic acid supplementation in pregnancy, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC research notes. 2018;11(1):345.

Seck B.C JRT: Determinant of compliance with iron supplementation among pregnant women in Senegal. Public Health Nutr 2007, 11(6):596–605.

Ugwu E, Olibe A, Obi S, Ugwu A. Determinants of compliance to iron supplementation among pregnant women in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17(5):608–12.

Gebremariam A.D TSA, Abate B.A, engidaw MT, Asnakew DT Adherance to iron and folic acid supplementation and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care followup at Debre Tabor General Hospital, Ethopia. 2017, 14(1).

Peña-Rosas JP, Viteri FE. Effects and safety of preventive oral iron or iron+ folic acid supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4.

Zeng L, Dibley MJ, Cheng Y, Dang S, Chang S, Kong L, et al. Impact of micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy on birth weight, duration of gestation, and perinatal mortality in rural western China: double blind cluster randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2008;337:a2001.

Yang J, Cheng Y, Pei L, Jiang Y, Lei F, Zeng L, et al. Maternal iron intake during pregnancy and birth outcomes: a cross-sectional study in Northwest China. Br J Nutr. 2017;117(6):862–71.

Srivastava R, Kant S, Singh AK, Saxena R, Yadav K, Pandav CS. Effect of iron and folic acid tablet versus capsule formulation on treatment compliance and iron status among pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2019;8(2):378–84.

Ghana Statistical Service. 2010 population and housing census report. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service; 2014.

Nukpezah RN, Nuvor SV, Ninnoni J. Knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in the tamale metropolis of Ghana. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):140.

Snedecor GWC, William G. Statistical methods. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1989.

Arega Sadore A, Abebe Gebretsadik L, Aman Hussen M: Compliance with iron-folate supplement and associated factors among antenatal care attendant mothers in Misha District, South Ethiopia: community based cross-sectional study. Journal of environmental and public health 2015, 2015.

Nwizu E.N IZ, Ibrahim S.A, Galadana H.H: Socio-demographic and maternal factors in anemia in pregnancy at Booking in Kano, northern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2011, 15(4):33–41.

Garenne M, Hohmann-Garenne S. A wealth index to screen high-risk families: application to Morocco. J Health Popul Nutr. 2003:235–42.

Ba DM, Ssentongo P, Kjerulff KH, Na M, Liu G, Gao X, et al. Adherence to iron supplementation in 22 Sub-Saharan African countries and associated factors among pregnant women: a large population-based study. Current developments in nutrition. 2019;3(12):nzz120.

Mithra P, Unnikrishnan B, Rekha T, Nithin K, Mohan K, Kulkarni V, et al. Compliance with iron-folic acid (IFA) therapy among pregnant women in an urban area of South India. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13(4):880–5.

Taye B, Abeje G, Mekonen A: Factors associated with compliance of prenatal iron folate supplementation among women in Mecha district, Western Amhara: a cross-sectional study. Pan African Medical Journal 2015, 20(1).

Acknowledgements

We thank the pregnant women who participated in the study.

Funding

The study was funded by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AW conceived and designed the study. MMK, AAN and JKF collected the data. AW and HG oversaw the data collection. HG analysed the data. MMK drafted the manuscript which was reviewed by AW and HG. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study protocol (Number 04-2018) was approved by the Joint Ethics Board of School of Medicine and Health Sciences and School of Allied Health Sciences, UDS, Tamale, Ghana.

Statement of informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from pregnant women before the administration of the questionnaire. The women were also assured of anonymity and confidentiality of the data being provided. As such, no person identifiable information was collected, and data collected were stored on password-protected computer and accessed only by members of the research team. The women were also informed that participation in the study was voluntary and those who did not want to participate were at liberty to decline the invitation to participate.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wemakor, A., Garti, H., Akai, M.M. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with compliance to iron and folic acid supplementation in pregnancy in Tamale Metropolis, Ghana. Nutrire 45, 16 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41110-020-00120-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41110-020-00120-6