Abstract

In this study, the semi-discretization technique is employed to establish a discrete representation of a modified Leslie-Gower prey-predator system that includes a Holling II type functional response. The dynamics of this model are then analyzed through the application of center manifold theory and bifurcation theory. We present comprehensive results for the local stability of the fixed points across the entire parameter space. Additionally, we provide sufficient conditions for the occurrence of flip bifurcation and Neimark-Sacker bifurcation. Besides, the system has experienced a flip bifurcation to chaos controlled using the method of chaos control, viz., state feedback method, pole placement technique, and hybrid control strategy. Furthermore, we provide specific conditions to ensure that bifurcation and chaos can be stabilized. Finally, numerical simulations are conducted to validate theoretical analysis and illustrate several new complex dynamical behaviors between two species.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction and preliminaries

The interactive dynamics between populations of prey and predator has been a focal point of interest within the discipline of mathematical ecology for an extended period. In 1910, Lotka [1] first proposed a prey-predator model similar to a chemical reaction. Volterra [2, 3] considered the same problem in 1926. Later, Holling [4, 5] extended the model to include density-dependent prey growth and presented various functional responses. The Leslie-Gower model [6, 7] is also one of the prey-predator models and modified by May [8].

In 2003, Alaoui and Okiye [9] proposed an adapted Leslie-Gower model that incorporated the Holling II functional response

where x and y represent the population densities of prey and predator at time t, respectively, and parameters \(r_{1}\), \(b_{1}\), \(a_{1}\), \(k_{1}\), \(r_{2}\), \(a_{2}\), and \(k_{2}\) are positive numbers with the subsequent biological implications: \(r_{1}\) (\(r_{2}\)) denotes the rate of increase in the prey (predator) population, while \(b_{1}\) quantifies the level of competition between individuals within the prey species. \(a_{1}\) (\(a_{2}\)) denotes the maximum value that can be reached per capita reduction rate of prey (predator), and \(k_{1}\) (\(k_{2}\)) assesses the degree to which the environment offers protection to the prey (predator) species.

Numerous researchers have conducted thorough investigations into the dynamics of the system (1.1). To enhance readers’ comprehension, we offer a collection of relevant literature [9–14]. Alaoui and Okiye [9] focused on examining the boundedness of solutions and the global stability of the positive fixed points within the system. Zhu and Wang [10] obtained rigorous results regarding the existence of globally attractive positive periodic solutions in the case where the parameters are positive and T-periodic functions. Wang and Zhang [11] identified the necessary conditions for the presence of a slow-fast limit cycle. Martínez-Jeraldo and Aguirre [12] studied the Allee effect affecting the prey species in the Leslie-Gower predator-prey model. They identified saddle-node, homoclinic and Hopf bifurcations around a Bogdanov-Takens point. Chakraborty et al. [13] studied a modified Leslie-Gower model with an impulsive three-species food chain and derived the global stability and permanence of the system. Chen et al. [14] studied the Leslie-Gower predator-prey model with feedback control and demonstrated that feedback control parameters do not affect the overall stability of the Leslie-Gower model; instead, they solely alter the location of the singular interior equilibrium while preserve its global stability.

To date, an increasing number of scholars have considered various comprehensive factors in biological and/or ecological systems, such as the functional response [9, 10, 15–19], Allee effect [12], impulsive effect [13, 15], diffusive effect [20], time delay [16, 21], and others. As is known, discrete-time models are more appropriate techniques for identifying the evolutionary behavior of a species with nonoverlapping generations, such as annual plants or insects that have a yearly reproductive cycle. Consequently, it is widely acknowledged that discrete-time models exhibit more intricate dynamics compared with continuous-time models, resulting in chaotic patterns in population interactions [22]. At the same time, chaos control can enhance the existence of chaos or create chaos when it is beneficial to the system. However, when chaos is undesirable and harmful to the system, chaos control involves eliminating or weakening the influence of chaos. Several strategies, including state feedback, pole placement, and hybrid control, are applied to control bifurcation and chaos in a discrete prey-predator model. For related work, please refer to the papers [23–27] and the references cited therein.

In order to discretize a continuous system, many authors choose the forward or backward Euler method [28]. Due to the requirement of accuracy, the forward Euler method (or backward Euler method) requires a step size of \(0 < h \ll 1\). In reality, meeting this condition can be challenging. In other words, the accuracy requirement is often violated. Thus, we utilize the semi-discretization method [29–37] in this paper to avoid violating the accuracy requirement and obtain the discrete version of system (1.1). For the details of the semi-discretization method, please refer to [29, 30, 32–35].

Here, we employ identical parameters scaling as described in a previous work [15] and take

Subsequently, by reassigning the parameters x̄, ȳ, and t̄ as x, y and t respectively, the system (1.1) is transformed into

In order to facilitate discussion, let us assume the parameters \(k_{1}=k_{2}=k\), which implies that the level of protection provided by the environment to both prey and predator is equal.

Letting

system (1.2) is reduced to the subsequent form:

By employing the semi-discretization technique on system (1.3), it is easy to obtain the discrete system as outlined below:

Here, the parameters a, m and s are all positive constants with distinct biological interpretations.

Now, the discrete system (1.4) can be also denoted by the following mapping:

In this paper, we mainly consider bifurcation problems in addition to the stability of map (1.5). Additionally, we observe that a chaotic set will emerge in our system; therefore, chaos control strategies are applied to stabilize unstable orbits by introducing small perturbations into map (1.5). Meanwhile, we use a definition and a key lemma, as referenced in [29, Def. 4.1, Lem. 4.2], which are mainly aimed at studying the stability and local bifurcation of its fixed points. Furthermore, state feedback, pole placement, and hybrid control methods are successful in controlling chaos on the map (1.5).

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, we formulate the conditions for the existence and stability of fixed points of map (1.5). In Sect. 3, we select the parameter s as the bifurcation parameter to study complex bifurcation problems at the positive fixed point \(E^{*}\). In Sect. 4, numerical simulations are conducted to validate the aforementioned theoretical findings and reveal several new dynamical properties. In Sect. 5, the control strategies outlined in map (1.5) are implemented to control chaos and validated through numerical simulations. In Sect. 6, we draw several new conclusions and give some discussions.

2 Existence and stability of fixed points

The stability of fixed points in map (1.5) is considered, and these fixed points satisfy the following conditions:

Taking into consideration the biological implications of map (1.5), the analysis focuses solely on nonnegative fixed points. Consequently, it is determined that map (1.5) exhibits a maximum of four fixed points under various conditions: the trivial fixed point \(O(0, 0)\), the semi-trivial fixed points \(A(\frac{1}{a}, 0)\), \(B(0,1)\), and the unique positive fixed point \(E^{*}(\frac{1-m}{a},\frac{1-m+a}{a})\), when \(0< m<1\).

For map (1.5), the Jacobian matrix at a fixed point \(E(x,y)\) is shown below

Hence, the characteristic polynomial of Jacobian matrix \(J(E)\) is expressed as follows:

Now, we present certain findings regarding the local stability of the fixed points O, A, B, and \(E^{*}\) in the subsequent theorems.

Theorem 2.1

The fixed point \(O=(0,0)\) of map (1.5) is a source.

Theorem 2.2

The fixed point \(A=(\frac{1}{a},0)\) of map (1.5) is a saddle.

Theorem 2.3

The following statements about the fixed point \(B=(0,1)\) of map (1.5) are true.

-

1.

When \(0< m<1\), the fixed point \(B(0,1)\) is a saddle,

-

2.

When \(m=1\), the fixed point \(B(0,1)\) is non-hyperbolic,

-

3.

When \(m>1\), the fixed point \(B(0,1)\) is a sink.

The results of Theorems 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3 are simple, and hence the proofs are omitted here.

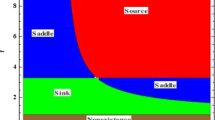

Theorem 2.4

When \(0< m<1\), map (1.5) has a unique positive fixed point \(E^{*}=(\frac{1-m}{a}, \frac{1-m+a}{a})\). Moreover, the results for the positive fixed point \(E^{*}\) as shown in Table 1below are valid, where \(R_{1}=2+\frac{2m(1-m)}{(m+1)(1-m+a)}\) and \(R_{2}=\frac{(2m-1-a)(1-m)}{m(1-m+a)}\).

Proof

For the positive fixed point \(E^{*}(\frac{1-m}{a},\frac{1-m+a}{a})\), the Jacobian matrix of map (1.5) is given by

The characteristic polynomial of Jacobian matrix \(J({E^{*}})\) can be written as

where

Notice that \(F(1)=s(1-m)>0\) always holds for \(0< m<1\). Obviously,

Now, compare \(R_{1}\) with \(R_{2}\).

Thus, \(R_{1}>R_{2}\) always holds. Then, consider the subsequent two cases.

Case I: m ∈ (0, \(\frac{1}{2}\)].

Then, \(R_{2}<0<s\). According to (2.2), one has \(C<1\); hence, the following derivations hold true.

-

1.

\(0< s< R_{1}\). It follows from (2.2) that \(F(-1)>0\) and \(C<1\). According to [29, Def. 4.1 (1), Lem. 4.2 (i.1)], one can conclude that the eigenvalues satisfy \(|\lambda _{1,2}|<1\), and hence the fixed point \(E^{*}\) is a sink.

-

2.

\(s=R_{1}\). Then, from (2.2), one has that \(F(-1)=0\) and \(C\neq 1\). [29, Def. 4.1 (4), Lem. 4.2 (i.2)] illustrates that the eigenvalues are \(\lambda _{1}=-1\) and \(\lambda _{2}\neq -1\), and therefore the fixed point \(E^{*}\) is non-hyperbolic.

-

3.

\(s>R_{1}\). Then, according to (2.2), we know that \(F(-1)<0\). [29, Def. 4.1 (3), Lem. 4.2 (i.3)] indicates that the eigenvalues satisfy \(\lvert \lambda _{1}\lvert <1\) and \(\lvert \lambda _{2}\lvert >1 \), so the fixed point \(E^{*}\) is a saddle.

Case II: \(m\in (\frac{1}{2},1)\).

Now, we again consider the following two subcases:

I. \(a\in (0,2m-1)\);

II. \(a\in [2m-1,+\infty )\).

First, consider Subcase I: \(a\in (0, 2m-1)\); then, \(R_{1}>R_{2}>0\). We divide \(s>0\) into the following five cases:

-

1.

, , \(E^{*}\) is a source;

-

2.

, , \(E^{*}\) is non-hyperbolic (a Neimark-Sacker bifurcatin may occur);

-

3.

, \(E^{*}\) is a sink;

-

4.

, , \(E^{*}\) is non-hyperbolic (a flip bifurcation possibly occurs);

-

5.

, \(E^{*}\) is a saddle.

Next, analyze Subcase II: \([2m-1, +\infty )\); then, one has \(R_{2}\leqslant 0\). The same results as in Case I: \(m \in (0, \frac{1}{2}]\) may be obtained. Therefore, the above results discussed were summarized in Table 1. □

3 Bifurcation analysis at the positive fixed point \(E^{*}\)

In this section, we mainly focus on examining the local bifurcation problems of map (1.5) at the unique positive fixed point \(E^{*}(\frac{1-m}{a},\frac{1-m+a}{a})\), when \(0< m<1\).

3.1 Flip bifurcation

For the positive fixed point \(E^{*}\), the following statements regarding the flip bifurcation of map (1.5) are true.

Theorem 3.1

Assume that the parameters \((a, m, s) \in \Omega _{1}=\{(a,m, s) \in R^{3}_{+}|a>0, s>0, 0< m<1 \}\) and let \(s_{0}=R_{1}=2+\frac{2m(1-m)}{(m+1)(1-m+a)}\). Let U and \(\gamma _{2}\) be defined in (3.7) and (3.8), respectively. If \(U\neq 0\), map (1.5) experiences a flip bifurcation at the positive fixed point \(E^{*}\) when the parameter s passes over the critical threshold \(s_{0}\). If \(\gamma _{2}>0\) (resp. \(\gamma _{2}<0\)), the flip bifurcation is supercritical (resp. subcritical), and the flip orbits that bifurcate from \(E^{*}\) are stable (resp. unstable).

Proof

Take the transformation \(l_{t}=x_{t}-\frac{1-m}{a}\), \(m_{t}=y_{t}-\frac{1-m+a}{a}\), which transfers \(E^{*}(\frac{1-m}{a},\frac{1-m+a}{a})\) to the origin \(O(0, 0)\), introduce a slight disturbance \(s^{*}\) to the parameter s around \(s_{0}\), namely, \(s^{*}=s-s_{0}\), with \(0<|s^{*}|\ll 1\) and set \(s_{t+1}^{*}=s_{t}^{*}=s^{*}\); then, map (1.5) may be shown as below:

Applying the Taylor expansion to system (3.1) at \((l_{t}, m_{t}, s_{t}^{*}) = (0, 0, 0)\) yields

where \(\rho _{1}=\sqrt{l_{t}^{2}+m_{t}^{2}+(s_{t}^{*})^{2}}\),

\(a_{200}=\frac{am}{1-m+a}+a(1-m)\frac{(1-2m+a)^{2}-2m}{2(1-2m+a)^{2}}\), \(a_{110}= \frac{(1-m+a)^{3}+a^{2}m(1-m)(2-2m+a)}{a(1-2m+a)^{2}}\),

\(a_{101}=0\), \(a_{020}=\frac{am^{2}(1-m)}{2(1-m+a)^{2}}\), \(a_{011}=a_{002}=0\),

\(a_{300}=\frac{a^{2}(1-2m+a)^{2}-2m}{2(1-2m+a)^{2}}-a^{2}(1-m) \frac{(1-2m+a)^{3}-6m(2-2m+a)}{6(1-m+a)^{3}}\),

\(a_{210}=\frac{-3a^{2}m(8m-5a-5)}{6(1-m+a)^{2}}- \frac{m(1-m)(1-2m+a)^{2}}{6(1-m+a)}+ \frac{a^{2}m(1-m)[-4m^{2}+(13+4a)m-a^{2}-5a-7]}{3(1-m+a)^{3}}\),

\(a_{201}=0\), \(a_{120}=\frac{a^{2}m^{2}}{2(1-m+a)^{2}}-m^{2}(1-m)[ \frac{a^{2}(4-2m+a)(m-a)}{6(1-m+a)^{3}}-\frac{1-2m+a}{6a}]\),

\(a_{111}=a_{102}=0\), \(a_{030}=\frac{-a^{2}m^{3}(1-m)}{6(1-m+a)^{3}}\), \(a_{021}=a_{012}=a_{003}=0\), \(b_{200}=\frac{aK(2+K^{2})}{2(1-m+a)}\), \(b_{110}=\frac{-aK(K+2)}{1-m+a}\), \(b_{101}=1\), \(b_{020}=\frac{aK(K+2)}{2}\), \(b_{011}=-1\),

\(b_{002}=0\), \(b_{300}=\frac{-a^{2}K}{(1-m+a)^{2}}[1+(1-m+a)K+\frac{1}{6}K^{2}]\),

\(b_{210}=\frac{a^{2}K}{(1-m+a)^{2}}(2+\frac{5}{2}K+\frac{1}{2}K^{2})\), \(b_{201}= \frac{-a(K+1)}{1-m+a}\),

\(b_{120}=\frac{a^{2}K}{(1-m+a)^{2}}(1+2K+\frac{1}{2}K^{2})\), \(b_{111}= \frac{2a(K+1)}{1-m+a}\),

\(b_{102}=0\), \(b_{030}=\frac{a^{2}K^{2}(K+3)}{6(1-m+a)^{2}}\), \(b_{021}= \frac{-a(K+1)}{1-m+a}\), \(b_{012}=b_{003}=0\),

where

One can obtain that the three eigenvalues of the matrix

are \(\lambda _{1}=-1\), \(\lambda _{2}=m[1-\frac{(1-m)^{2}}{(1-m+a)(1+m)}]\), \(\lambda _{3}=1\) with the corresponding eigenvectors \(\xi _{1}= \begin{pmatrix} \frac{m(1-m)}{(1+m)(1-m+a)+m(1-m)} \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \), \(\xi _{2}= \begin{pmatrix} \frac{m+1}{2} \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \) and \(\xi _{3}= \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} \). Set \(T=(\xi _{1}, \; \xi _{2}, \; \xi _{3})\), namely,

then

where

The transformation \( \begin{pmatrix} l_{t} \\ m_{t} \\ s_{t}^{*} \end{pmatrix} =T \begin{pmatrix} u_{t} \\ v_{t} \\ \sigma _{t} \end{pmatrix} \) changes system (3.2) into

where \(\rho _{2}=\sqrt {u_{t}^{2}+v_{t}^{2}+\sigma _{t}^{2}}\),

Consider for the center manifold that

where \(\rho _{3}=\sqrt {u_{t}^{2}+\sigma _{t}^{2}}\); then, based on the subsequent expressions:

and by matching coefficients across the same orders of terms, one can derive

Therefore, system (3.6), confined to the center manifold, is denoted below

where

Afterwards, we compute the subsequent quantities to assess the occurrence of a flip bifurcation in accordance with [38, (21.2.17)–(21.2.22), p. 516]. One has the following results:

Notice that

equivalently,

and

Thus, if \(U\neq 0\), then, map (1.5) experiences a flip bifurcation at the positive fixed point \(E^{*}\).

The transversal condition (\(\gamma _{1}\)) and nondegenerate condition (\(\gamma _{2}\)), which are used to ascertain the presence and orientation of a flip bifurcation [29–34], are also calculated based on the following two specific quantities:

If \(\gamma _{2}> 0\) \((resp. <0)\), the period-doubling orbits that bifurcate from \(E^{*}\) are stable (resp. unstable). □

3.2 Neimark-Sacker bifurcation

When the parameters \(m\in (\frac{1}{2},1)\), \(a\in (0, 2m-1)\), and \(s=R_{2}=\frac{(2m-1-a)(1-m)}{m(1-m+a)}\), it follows from Table 1 that the eigenvalues \(\lambda _{1}\) and \(\lambda _{2}\) are a pair of conjugate complex roots with \(|\lambda _{1}|=|\lambda _{2}|=1\). At this moment, map (1.5) may experience a Neimark-Sacker bifurcation. One can derive the subsequent result.

Theorem 3.2

Let \(s_{0}=R_{2}=\frac{(2m-1-a)(1-m)}{m(1-m+a)}\) and L be defined in (3.13). Assume the parameters \((a, m, s) \in \Omega _{2}=\{(a, m, s) \in R^{3}_{+}| \frac{1}{2}< m<1, 0<a<2m-1, s>0 \}\). Then map (1.5) experiences a Neimark-Sacker bifurcation at the positive fixed point \(E^{*}\) when the parameter s changes within the small neighborhood of the critical threshold \(s_{0}\). Moreover, if \(L<(>)0\), then an attracting (repelling) invariant closed curve bifurcates from the fixed point for \(s>(<)s_{0}\).

Proof

Take \(l_{t}=x_{t}-\frac{1-m}{a}\) and \(m_{t}=y_{t}-\frac{1-m+a}{a}\) to transform \(E^{*}\) to the origin O. Given a slight disturbance \(s^{*}\) to the parameter s around \(s_{0}\), namely, \(s^{*}= s-s_{0}\), with \(0< |s^{*}|\ll 1\), map (1.5) may be written as following:

Applying the Taylor expansion to (3.9) at \((l_{t}, m_{t})= (0, 0)\) yields

where \(r_{4}=\sqrt {l_{t}^{2}+m_{t}^{2}}\).

Assume that the characteristic polynomial of the Jacobian matrix for linearized system of system (3.10) as \(F(\lambda )=\lambda ^{2}-p(s^{*})\lambda +q(s^{*})\) with

Then, the two roots of \(F(\lambda )=0\) are

Noticing that the parameter vector \((m, a, s) \in \Omega _{2}\), one has

Thus,

where

Obviously, for \(0< |s^{*}|\ll 1\),

hence,

The occurrence of the Neimark-Sacker bifurcation is characterized by the following specific conditions that must be satisfied:

It is obvious that \(\lambda ^{i}_{1, 2}(0)\ne 1\) for all \(i=1,2,3,4\); hence, all necessary conditions for the occurrence of the Neimark-Sacker bifurcation have been met.

Now, proceed to search for the normal form of system (3.9) when \(s^{*}=0\). Applying the Taylor expansion to system (3.9) at \((l_{t}, m_{t}) = (0, 0)\) leads to

where \(r_{5}=\sqrt {l_{t}^{2}+m_{t}^{2}}\),

\(a_{20}=\frac{am}{1-m+a}+a(1-m)\frac{(1-2m+a)^{2}-2m}{2(1-2m+a)^{2}}\), \(a_{11}= \frac{(1-m+a)^{3}+a^{2}m(1-m)(2-2m+a)}{a(1-2m+a)^{2}}\),

\(a_{02}=\frac{am^{2}(1-m)}{2(1-m+a)^{2}}\), \(a_{30}= \frac{a^{2}(1-2m+a)^{2}-2m}{2(1-2m+a)^{2}}-a^{2}(1-m) \frac{(1-2m+a)^{3}-6m(2-2m+a)}{6(1-m+a)^{3}}\),

\(a_{21}=\frac{-3a^{2}m(8m-5a-5)}{6(1-m+a)^{2}}- \frac{m(1-m)(1-2m+a)^{2}}{6(1-m+a)}+ \frac{a^{2}m(1-m)[-4m^{2}+(13+4a)m-a^{2}-5a-7]}{3(1-m+a)^{3}}\),

\(a_{12}=\frac{a^{2}m^{2}}{2(1-m+a)^{2}}-m^{2}(1-m)[ \frac{a^{2}(4-2m+a)(m-a)}{6(1-m+a)^{3}}-\frac{1-2m+a}{6a}]\), \(a_{03}= \frac{-a^{2}m^{3}(1-m)}{6(1-m+a)^{3}}\), \(b_{20}=\frac{as_{0}}{1-m+a}(\frac{s_{0}}{2}-1)\), \(b_{11}= \frac{as_{0}(2-s_{0})}{1-m+a}\), \(b_{02}=\frac{as_{0}}{1-m+a}( \frac{s_{0}}{2}-1)\), \(b_{30}=\frac{a^{2}s_{0}}{(1-m+a)^{2}}(\frac{s_{0}^{2}}{6}-s_{0}+1)\), \(b_{21}= \frac{a^{2}s_{0}}{(1-m+a)^{2}}(-\frac{s_{0}^{2}}{2}+\frac{5s_{0}}{2}-2)\),

\(b_{12}=\frac{a^{2}s_{0}(s_{0}^{2}-4s_{0}+2)}{2(1-m+a)^{2}}\), \(b_{03}= \frac{a^{2}s_{0}^{2}(3-s_{0})}{6(1-m+a)^{2}}\).

Clearly, two distinct eigenvalues of the matrix

are \(\lambda _{1}(0)\) and \(\lambda _{2}(0)\) with the corresponding eigenvectors \(\xi _{1}= \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ \beta \end{pmatrix} \) and \(\xi _{2}= \begin{pmatrix} a_{01} \\ \frac{1}{2}(1-s_{0}-a_{10}) \end{pmatrix} \). Let \(T=(\xi _{1}, \; \xi _{2})\), i.e.,

The transformation \( \begin{pmatrix} l_{t} \\ m_{t} \end{pmatrix} =T \begin{pmatrix} u_{t} \\ v_{t} \end{pmatrix} \) brings system (3.11) to the following form:

where \(r_{6}=\sqrt {u_{t}^{2}+v_{t}^{2}}\),

Furthermore,

Next, we compute the first Lyapunov coefficient L to judge the occurrence and stability of the Neimark-Sacker bifurcation [31, 34]:

where

\(\xi _{20}=\frac{1}{8}[\overline{f}_{uu}-\overline{f}_{vv}+2 \overline{g}_{uv}+i(\overline{g}_{uu}-\overline{g}_{vv}- 2 \overline{f}_{uv})]\),

\(\xi _{11}=\frac{1}{4}[\overline{f}_{uu}+\overline{f}_{vv}+i( \overline{g}_{uu}+\overline{g}_{vv})]\),

\(\xi _{02}=\frac{1}{8}[\overline{f}_{uu}-\overline{f}_{vv}-2 \overline{g}_{uv} +i(\overline{g}_{uu}-\overline{g}_{vv}+2 \overline{f}_{uv})]\),

\(\xi _{21}=\frac{1}{16}[\overline{f}_{uuu}+\overline{f}_{uvv}+ \overline{g}_{uuv}+\overline{g}_{vvv}+ i(\overline{g}_{uuu}+ \overline{g}_{uvv}-\overline{f}_{uuv}-\overline{f}_{vvv})] \).

Some calculations display

Substituting these values into the expression of L, the value of L will be obtained. When \(L\neq 0\), the Neimark-Sacker bifurcation takes place. In the case of \(L<(>)0\), an attracting (repelling) invariant closed curve will emerge from the fixed point for \(s>(<)s_{0}\).

The proof is completed. □

4 Numerical simulations

In this section, we utilize Matlab software to validate the theoretical findings and explore additional dynamical behaviors that emerge as the parameters vary.

Example 4.1

We choose the parameters \(a=0.3\), \(m=0.3\), \(s=2\) and the initial values as \((x_{0}, y_{0}) = (6, 3)\). When these parameters are fixed, map (1.5) can be transformed as the following one:

It can be concluded that the positive fixed point of the above system (4.1) is \(E^{*}(2.3333, 3.3333)\) and the critical point \(R_{1}=2.323\). According to Theorem 2.4, the unique positive fixed point is locally asymptotically stable when these parameters satisfy \(0< m<0.5\), \(a>0\) and \(s< R_{1}\). Figure 1 shows the stable dynamics in map (1.5), including that two species coexist and converge to the fixed point \(E^{*}(2.3333,3.3333)\). Then, we modify the value of the parameter s and let the parameter s ∈ (2.2, 3.0). Since the bifurcation diagram of the \((s, x)\)-plane closely resembles that of the \((s, y)\)-plane, we will exclusively present the former. From Fig. 2(a), we observe the existence of flip bifurcation at \(E^{*}\) when \(s_{0}=R_{1}=2.323\), which is aligned with the result presented in Theorem 3.1. By calculating the sign of the parameter \(\gamma _{2} \), we can obtain period-2 orbit and its stability. Moreover, the periods are 2, 4, 8, etc., which illustrate that a chaotic set (period-doubling route to chaos) emerges as the increasing of the value of the parameter s. Figure 2(b) illustrates the range of maximum Lyapunov exponents in relation to the parameter \(s\in (2.2, 3.0)\) under the condition where \(a = 0.3\) and \(m = 0.3\); it is also observed that the maximal Lyapunov exponents are positive for \(b\in (2.92,3.0)\), which means that chaos will occur in this system; hence, chaos control is considered in Sect. 5.

Stable time series for map (1.5) at \(a=0.3\), \(m=0.3\) and \(s=2\)

Bifurcation of the map (1.5) in the \((s,x)\)-plane and the maximal Lyapunov exponent for \(a=0.3\) and \(m=0.3\) with the initial values \((x_{0}, y_{0})=(6, 3)\)

Remark 1

In Fig. 3, two bifurcation diagrams are drawn with respect to s, which illustrate that for lower value of parameter a, chaos disappears in map (1.5). Nevertheless, for the lower value of parameter m, chaos will occur in advance.

Bifurcation diagrams of map (1.5) with respect to s and the initial value \((x_{0}, y_{0})=(6, 3)\)

Example 4.2

For the set of parameters \(a = 0.1\), \(m=0.6\), \(s=0.1\) and the initial value \((x_{0}, y_{0}) = (6, 3)\), according to Theorem 3.2, one can see that when \(s_{0}=R_{2}=0.1333\), map (1.5) undergoes a Neimark-Sacker bifurcation. In Figs. 4 and 5, the fixed point \(E^{*}\) is unstable when \(s< R_{2}\); conversely, \(E^{*}\) becomes stable, and a closed invariant curve disappears when \(s>R_{2}\). Figure 6 is plotted as the bifurcation diagram at \((s,x)\)-plane, which shows the prey population converges to stable as the parameter s increases. To clearly demonstrate this point of view, we take the parameter s near 0.133 and obtain more phase portraits in Fig. 7, which demonstrates the occurrence of the Neimark-Sacker bifurcation for map (1.5) at the fixed point \(E^{*}(4, 5)\).

Time series for map (1.5) at \(a=0.1\) and \(m=0.6\) with the initial value \((x_{0}, y_{0})=(6, 3)\)

Phase portraits for map (1.5) at \(a=0.1\) and \(m=0.6\) with the initial value \((x_{0}, y_{0})=(6, 3)\)

Bifurcation diagram of map (1.5) with respect to s and the initial value \((x_{0}, y_{0})=(6, 3)\)

Phase portraits for map (1.5) at \(a=0.1\) and \(m=0.6 \) with the initial value \((x_{0}, y_{0})=(6, 3)\)

5 Chaos control

Chaos is a ubiquitous nonlinear phenomenon and has been observed in a variety of dynamical systems. In effect, it makes the system undesirable as it can cause a lot of destructive results in many scenarios. Therefore, it is particularly important to use chaos control to ensure that the system is predictable and stable. Then, in this section, we will introduce state feedback, pole placement, and hybrid control strategies to control chaos [23–27] and illustrate them by numerical simulations.

5.1 State feedback control

We define the controlled system of map (1.5) is

where \(U_{t}=-h_{1}(x_{t}-\frac{1-m}{a})-h_{2}(y_{t}-\frac{1-m+a}{a})\). For the positive fixed point \(E^{*}(\frac{1-m}{a},\frac{1-m+a}{a})\), the Jacobian matrix of system (5.1) is as follows

The characteristic polynomial of Jacobian matrix \(J({E^{*}})\) is

where

The eigenvalues \(\lambda _{1}\) and \(\lambda _{2}\) are the roots of the equation \(F(\lambda )=0\), and the lines \(l_{1}\), \(l_{2}\) and \(l_{3}\) must satisfy the conditions \(\lambda _{1} \lambda _{2}=1\), \(\lambda _{1}=1\), \(\lambda _{1}=-1\). One has

For the stability, map (1.5) will be locally stable if all eigenvalues are contained within a triangular region bounded by three lines \(l_{1}\), \(l_{2}\), and \(l_{3}\).

5.2 Pole placement technique

Based on pole-placement method, Romeiras et al. [26] proposed the new chaos controlling technique, which is perceived as a generalized OGY method first time studied by Ott et al. [24]. Applying the method in map (1.5), one has the following:

where a is taken as control parameter with \(|a-a_{0}|<\delta \) and \(\delta >0\) arbitrarily small. The parameter \(a_{0}\) refers to the nominal value belonging to chaotic region. Subsequently, system (5.3) can be estimated in the neighborhood of unstable fixed point \(E^{*}(x^{*},y^{*})\) as the equation

where

Set

then system (5.3) is considered controllable when the matrix C possesses a rank of 2. Hence, if \(|C|\neq 0\), system (5.3) will be controllable. Furthermore, from (5.4) we assume that

where \(D=[d_{1}, d_{2}]\), then map (5.4) can be represented as

We take \(D=[d_{1},\ d_{2}]\) to satisfy two eigenvalues of the matrix \((A-BD)\) to lie in an open unit disk, then the fixed point \(E^{*}(x^{*},y^{*})\) is locally asymptotically stable. These specific eigenvalues are commonly referred to as regulator poles, and positioning these eigenvalues at a specified value is known as the pole-placement technique. Furthermore, the rank of the matrix C is 2, guaranteeing that the pole-placement problem has only a singular solution (a unique matrix D). Next, we set the characteristic equations of matrices A and \(A-BD\) to be \(\lambda ^{2}+\alpha _{1} \lambda +\alpha _{2}\) and \(\lambda ^{2}+\beta _{1} \lambda +\beta _{2}\), respectively. Therefore, from [23], the distinct solution to the pole placement problem can be identified as outlined below

where \(T=CF\) and

5.3 Hybrid control strategy

First, we consider an n-dimensional discrete nonlinear dynamical system

where \(x_{t}\in \mathbb{R}^{n}\), \(t\in \mathbb{Z}\), \(s\in \mathbb{R}\) is bifurcation parameter of system (5.6). Combinating state feedback and parameter perturbation to system (5.6), one gets

where the control parameter \(\alpha \in (0,1)\), \(m\in \mathbb{N^{+}}\) and \(f^{m}(\cdot )\) is the mth iteration of \(f(\cdot )\). Specially, the controlled system (5.7) will reduce to the original system (5.6) when \(\alpha =1\) [39]. For two-dimensional example, we provide general results for controlling bifurcation in discrete systems. Let \(m=1\), \(x_{t}\in \mathbb{R}^{2}\). The uncontrolled system (5.6) and corresponding controlled system (5.7) are

and

For the fixed point \((x_{0}, y_{0})\), the Jacobian matrix of system (5.9) is shown below

Then, the characteristic polynomial of the Jacobian matrix \(J(x_{0},y_{0})\) is

where

Theorem 5.1

If the unregulated system (5.8) exhibits a Codim 1 bifurcation at the fixed point when the bifurcation parameter \(s=s_{0}\) and parameters α and s meet the specified criteria:

-

1.

\(F(1)=1-tr(J(x_{0},y_{0}))+det(J(x_{0},y_{0}))>0\),

-

2.

\(F(-1)=1+tr(J(x_{0},y_{0}))+det(J(x_{0},y_{0}))>0\),

-

3.

\(det(J(x_{0},y_{0})) <1\),

then, the bifurcation of the controlled system (5.9) at the fixed point \(E(x_{0},y_{0})\) can be delayed (advanced) or even eliminated. Simultaneously, the fixed point of the controlled system is asymptotically stable.

Proof

Obviously, the fixed point of the controlled system (5.9) is the same as the original system (5.8), and the eigenvalue equation Eq. (5.10) can be denoted by \(F(\lambda )=0\). Thus, based on the condition of [29, Lem. 4.2 \((i.1)\)], one has \(|\lambda _{1,2}|<1\); then, the fixed point of the controlled system is asymptotically stable, and the bifurcation of the fixed point can be delayed (advanced) or even eliminated by choosing specific parameters α and s.

By applying the above hybrid control method in Theorem 5.1, we rewrite uncontrolled map (1.5) into a controlled system as follows:

The Jacobian matrix of system (5.11) at \(E^{*}(\frac{1-m}{a},\frac{1-m+a}{a})\) reads

The characteristic polynomial of Jacobian matrix \(J(E^{*})\) is

where

Based on Theorem 5.1, system (5.11) is asymptotically stable under the conditions \(F(1)>0\), \(F(-1)>0\) and \(det(J(E^{*}))<0\), where

□

5.4 Numerical simulations

In this subsection, we utilize numerical methods for the purpose of controlling chaos in map (1.5).

For state feedback method, we take the following parameter values:

Now, the conditions in (5.2) take the following form:

For the controlled system (5.1), \(U_{t}=-h_{1}(x_{t}-\frac{1-m}{a})-h_{2}(y_{t}-\frac{1-m+a}{a})\) is defined as a feedback force, and \(h_{1}\) and \(h_{2}\) represent feedback coefficients. Then, we take parameters \(h_{1}\), \(h_{2}\) as \(h_{1}=2\), \(h_{2}=1\), which are selected from the triangular region (as in Fig. 8, which is enclosed by the marginal lines \(l_{1}\), \(l_{2}\), and \(l_{3}\)). Thus, a stable time series is demonstrated in Fig. 9, and map (1.5) exhibits a stable dynamical behavior.

Stability region for map (1.5)

Stable time series for map (1.5) when \(a = 0.1\), \(m = 0.6\), \(s = 0.1\) and \(h_{1} = 2\), \(h_{2} = 1\)

From Fig. 3(b), when taking the parameters \(a=0.3\), \(m=0.1\), map (1.5) undergoes a period-doubling bifurcation as s varies in [2, 3]. To satisfy \(|C| \neq 0\), we set \(m=0.1\), \(s=2.9 \) in map (1.5), the parameter a is taken as control parameter and the nominal value \(a_{0}=0.3\), which belongs to chaotic region shown in Fig. 10(a). Hence, the unique positive fixed point \(E^{*}(3,4)\) is a saddle and unstable. Moreover, map (1.5) can be shown as

As in Sect. 5.2, pole placement technique depicts

Obviously, \(|C|\neq 0\), which means the controllability of system (5.3).

Take \(a=0.3-d_{1}(x_{n}-x^{*})-d_{2}(y_{n}-y^{*})\), where \(D=[d_{1}, \ d_{2}]\) represents a gain matrix. The corresponding controlled system is

Hence, the Jacobian matrix \((A-BD)\) of the controlled system (5.16) is of the form:

and the corresponding characteristic equation is

According to [29, Lem. 4.2 (i.1)], one has the following conditions:

Hence, these eigenvalues (regulator poles) are placed at desired value (open unit disk).

For \(d_{1}=-0.02\) and \(d_{2}\in (-0.029616,-0.025977)\), system (5.3) is stable at the fixed point \(E^{*}\). Figure 10(b) shows that the chaos in Fig. 10(a) has been reduced to a periodic window.

For the numerical illustration of hybrid control strategy, we take the following parameter set:

We find that map (1.5) losses its stability and produces flip bifurcation and chaos.

According to (5.13), for the controlled system (5.11), the control parameter α is restricted to \((0.3746, 0.9321)\). Without sacrificing the generality, we select the values of parameter \(\alpha =0.5,\ 0.8,\ 0.9\), then, the Jacobian matrix of the controlled system (5.11) takes

One can see that the corresponding eigenvalue of system (5.18) lie in an open unit disk. Compared with Fig. 2(a), bifurcation diagrams w.r.t. s in Fig. 11(a)–(c) illustrate that chaos can be delayed or even eliminated by reducing the value of parameter α.

Bifurcation diagrams of the controlled system (5.11) when \(a=0.3\) and \(m=0.3\) with the initial value \((x_{0}, y_{0})=(6, 3)\)

6 Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, the dynamical properties of a discrete modified Leslie-Gower prey-predator system with Holling II type functional response are studied. After assuming that the environment provides the same level of protection to both prey and predator \((k_{1}=k_{2}=k)\), we can simplify the parameters in the system to analyze its dynamics more effectively. Subsequently, the semi-discretization method is employed to derive the discrete version of system (1.3). Firstly, we not only clearly and completely demonstrate the existence and stability of the nonnegative fixed points \(O(0,0)\), \(A(\frac{1}{a},0)\), \(B(0,1)\), and the unique positive fixed point \(E^{*}(\frac{1-m}{a},\frac{1-m+a}{a})\) for \(0< m<1\), but also derive the sufficient conditions for the occurrence of the flip bifurcation and Neimark-Sacker bifurcation of map (1.5) at the unique positive fixed point \(E^{*}\). Meanwhile, numerical simulation results are conducted not only to validate the analytical results derived but also to illustrate more new complex dynamical behaviors, including \((i)\) the stability of the unique positive fixed point \(E^{*}\); \((ii)\) a closed invariant curve gradually disappears when the condition changes from \(s< R_{2}\) to \(s>R_{2}\); (iii) flip bifurcation to chaos will occur in map (1.5). Then, specific conditions for state feedback control as shown in (5.2), pole placement control as indicated in (5.5), and hybrid control as presented in (5.13) are provided to control chaos. Furthermore, the three methods successfully demonstrate that chaos can be delayed or even eliminated.

Our results obtained in this paper may serve as a catalyst for increasing focus on the dynamic behavior of discrete systems, complementing existing research on bifurcation theory and chaos control. Furthermore, these results can enhance our comprehension of population dynamics in natural ecosystems.

Data availability

No relevant data is associated with this manuscript.

References

Lotka, A.J.: Contribution to the theory of periodic reaction. J. Phys. Chem. 14(3), 271–274 (1910)

Volterra, V.: Variazioni e fluttuazioni del numero d’individui in specie animali conviventi. Mem. R. Accad. Naz. Lincei 2, 31–113 (1926)

Volterra, V.: Variations and fluctuations of the number of individuals in animal species living together. Translation In: R.N. Chapman: Animal Ecology. McGraw Hill, New York (1931)

Holling, C.S.: The components of predation as revealed by a study of small-mammal predation of the European pine sawfly. Can. Entomol. 91(5), 293–320 (1959)

Holling, C.S.: Some characteristics of simple types of predation and parasitism. Can. Entomol. 91(7), 385–398 (1959)

Leslie, P.H.: Some further notes on the use of matrices in population mathematics. Biometrika 35, 213–245 (1948)

Leslie, P.H., Gower, J.C.: The properties of a stochastic model for the predator-prey type of interaction between two species. Biometrika 47, 219–234 (1960)

May, R.: Stability and complexity in model ecosystems. In: Monographs in Population Biology. Princeton University Press, Princeton (1974)

Aziz-Alaoui, M.A., Okiye, M.D.: Boundedness and global stability for a predator-prey model with modified Leslie-Gower and Holling-type II schemes. Appl. Math. Lett. 16(7), 1069–1075 (2003)

Zhu, Y., Wang, K.: Existence and global attractivity of positive periodic solutions for a predator-prey model with modified Leslie-Gower Holling-type II schemes. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 384(2), 400–408 (2011)

Wang, C., Zhang, X.: Relaxation oscillations in a slow-fast modified Leslie-Gower model. Appl. Math. Lett. 87, 147–153 (2019)

Martínez-Jeraldo, N., Aguirre, P.: Allee effect acting on the prey species in a Leslie-Gower predation model. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 45, 895–917 (2019)

Chakraborty, K., Das, K., Yu, H.: Modeling and analysis of a modified Leslie-Gower type three species food chain model with an impulsive control strategy. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 15, 171–184 (2015)

Chen, L.J., Chen, F.D.: Global stability of a Leslie-Gower predator-prey model with feedback controls. Appl. Math. Lett. 22(9), 1330–1334 (2009)

Song, X.Y., Li, Y.F.: Dynamic behaviors of the periodic predator-prey model with modified Leslie-Gower Holling-type II schemes and impulsive effect. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 9(1), 64–79 (2008)

Nindjin, A.F., Aziz-Alaoui, M.A., Cadivel, M.: Analysis of a predator-prey model with modified Leslie-Gower and Holling-type II schemes with time delay. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 7(5), 1104–1118 (2006)

Yang, W., Li, Y.: Dynamics of a diffusive predator-prey model with modified Leslie-Gower and Holling-type III schemes. Comput. Math. Appl. 65(11), 1727–1737 (2013)

Yuan, S., Song, Y.: Bifurcation and stability analysis for a delayed Leslie-Gower predator-prey system. IMA J. Appl. Math. 74, 574–603 (2009)

Zhou, J.: Positive solutions of a diffusive predator-prey model with modified Leslie-Gower and Holling-type II schemes. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 389(2), 1380–1393 (2012)

Melese, D., Feyissa, S.: Stability and bifurcation analysis of a diffusive modified Leslie-Gower prey-predator model with prey infection and Beddington DeAngelis functional response. Heliyon 7, 1–14 (2021)

Yuan, R., Jiang, W.H., Wang, Y.: Saddle-node-Hopf bifurcation in a modified Leslie-Gower predator-prey model with time-delay and prey harvesting. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 422(2), 1072–1090 (2015)

Kuzenetsov, Y.A.: Elements of Applied Bifurcation Theory, 2nd edn. Springer, New York (1998)

Singh, A., Sharma, V.S.: Bifurcations and chaos control in a discrete-time prey-predator model with Holling type-II functional response and prey refuge. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 418, 114666 (2023)

Ott, E., Grebogi, C., Yorke, J.A.: Controlling chaos. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64(11), 1196 (1990)

Luo, X.S., Chen, G., Wang, B.H., Fang, J.Q.: Hybrid control of period-doubling bifurcation and chaos in discrete nonlinear dynamical systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 18(4), 775–783 (2003)

Romeiras, F.J., Grebogi, C., Ott, E., Dayawansa, W.P.: Controlling chaotic dynamical systems. Physica D 58(1–4), 165–192 (1992)

Din, Q.: Compexity and chaos control in a discrete-time prey-predator model. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 49, 113–134 (2017)

Chen, Q., Teng, Z., Wang, F.: Fold-flip and strong resonance bifurcations of a discrete-time mosquito model. Chaos Solitons Fractals 144, 110704 (2021)

Ruan, M.J., Li, C., Li, X.Y.: Codimension two 1:1 strong resonance bifurcation in a discrete predator-prey model with Holling IV functional response. AIMS Math. 7(2), 3150–3168 (2022)

Li, W., Li, X.Y.: Neimark-Sacker bifurcation of a semi-discrete hematopoiesis model. J. Appl. Anal. Comput. 8, 1679–1693 (2018)

Yao, W.B., Li, X.Y.: Bifurcation difference induced by different discrete methods in a discrete predator-prey model. J. Nonlinear Model. Anal. 4(1), 64–79 (2022)

Yao, W.B., Li, X.Y.: Complicate bifurcation behaviors of a discrete predator-prey model with group defense and nonlinear harvesting in prey. Appl. Anal. 102(9), 2567–2582 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/00036811.2022.2030724

Pan, Z.K., Li, X.Y.: Stability and Neimark-Sacker bifurcation for a discrete Nicholson’s blowflies model with proportional delay. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 27(2), 250–260 (2021)

Liu, Y.Q., Li, X.Y.: Dynamics of a discrete predator-prey model with Holling-II functional response. Int. J. Biomath. 14(8), 2150068 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793524521500686

Wang, C., Li, X.Y.: Further investigations into the stability and bifurcation of a discrete predator-prey model. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 422, 920–939 (2015)

Winggins, S.: Introduction to Applied Nonlinear Dynamical Systems and Chaos. Springer, New York (2003)

Robinson, C.: Dynamical Systems: Stability, Symbolic Dynamics, and Chaos. CRC Press, London (1995)

Carr, J.: Application of Center Manifold Theorem. Springer, New York (1981)

Yuan, L.G., Yang, Q.G.: Bifurcation, invariant curve and hybrid control in a discrete-time predator-prey system. Appl. Math. Model. 39, 2345–2362 (2015)

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61473340) and the Distinguished Professor Foundation of the Qianjiang Scholar in Zhejiang Province (F708108N02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made equal and substantial contributions to the composition of this paper. Each author reviewed and endorsed the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruan, M., Li, X. Complex dynamical properties and chaos control for a discrete modified Leslie-Gower prey-predator system with Holling II functional response. Adv Cont Discr Mod 2024, 30 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-024-03828-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-024-03828-1