Abstract

Introduction

Refugee HIV positive mothers experience significant obstacles in accessing, utilizing and adhering to antiretroviral therapy (ART). Identifying ART non-adherence can help in the development of interventions aimed at improving adherence and subsequently effectiveness of ART among the refugee mothers. We describe the use and the factors associated with non-adherence to ART among Refugee HIV positive pregnant mothers aged 18–49 years in Kyangwali Refugee Camp, Uganda.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study among HIV positive pregnant mothers aged 18–49 years in Kyangwali refugee camp between May and June 2023. Using a structured questionnaire, we collected data on use, and factors associated with non-adherence to ART. We used modified Poisson regression analysis to determine factors associated with non-adherence to ART.

Results

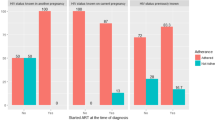

Of the 380 participants enrolled, 192 (50.5%) were married, mean age 32.1 years. Overall, 98.7; 95% Confidence Interval (CI) [97.5–99.8%] were using ART and 27.4; 95% CI [22.9–31.9%] were non-adherent. Non-adherence was associated with: Initiating Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) care in the third trimester of pregnancy (adjusted Prevalence ration(aPR): 2.06; 95% CI: 1.27–3.35), no need to get permission to seek PMTCT services aPR 1.61; 95% CI [1.07–2.42] and poor attitude of PMTCT providers aPR 1.90; 95% CI [1.20–3.01].

Conclusion and recommendations

Non-adherence to ART was generally high; therefore limiting the effectiveness of the PMTCT program in this setting. Refugee context specific education interventional programs aimed at early initiation into HIV care, strong social and psychological support from families, communities and health care providers are vital to improve adherence in this setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, HIV remains a major public health concern, with especially countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) reporting increasing trends in new infections [1]. As of 2022, there was an estimated 39.0 million people living with HIV, with two thirds in SSA alone [1]. In Uganda, prevalence of HIV among adults in the general population is at 5.8% but higher among women at 7.2% [2]. In the refugee settlements, prevalence of HIV among adults is 1.8% among women and 1.1% among men [3]. Refugees are at an increased risk of contracting HIV due to the extended displacement and associated disruption to their lives [4]. They are often accused of importing HIV to the host communities, and are therefore discriminated against [4] and their priorities are characterized by day-to-day survival such as finding food, safety, and shelter over health [4,5,6]. In such circumstances, women often engage in commercial sex for food, shelter, clothing and other basic commodities [4], which puts them at a high risk of acquiring HIV and subsequently risks of vertical transmission of the infection to their unborn babies and breast-feeding infants [4].

Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) is a proven HIV prevention intervention set and adopted by various health systems globally [7]. PMTCT programs provide a range of services to mothers and their infants. These services include HIV testing and counselling, ART initiation, safe sex practices, safe child birth practices, appropriate feeding practices and viral load testing and ART prevention for exposed infants [8, 9]. In order to achieve viral load suppression and prevention of mother to child transmission, ART should be initiated early in pregnancy and optimal adherence observed [10, 11]. However, evidence shows various gaps in implementation of PMTCT programs. In a systematic assessment in low and middle-income countries, nearly half of HIV positive expectant mothers neither received ART prophylaxis during antenatal care (ANC) nor delivered in health facilities [12]. A study in Northern Uganda using health facility data from 2002 to 2011 showed that only 69.4% of HIV positive gravid mothers were started on ART for prophylaxis [12]. Mukose et al. in a study conducted in Central Uganda found that 91% of mothers received a prescription of ART; of whom 93.3% started swallowing their medicines and only 76.8% achieved optimal adherence to ART [11]. In a qualitative study conducted in Nakivale Refugee settlement camp in Uganda it was found that difficulty in accessing clinics when ill, food insecurity, drug stock outs, and violence were the major barriers to ART adherence [13]. The current study describes the use and the factors associated with non-adherence to ART among Refugee HIV positive pregnant mothers aged 18–49 years in Kyangwali Refugee Camp, Western Uganda using the social ecological model. We observe that although PMTCT services exist, refugee pregnant mothers experience significant obstacles in accessing, utilizing and adhering to such services which negatively affects the effectiveness of the program. Refugee context specific education interventional programs aimed at early initiation into HIV care, strong social and psychological support from families, communities and health care providers are vital to improve adherence in this setting.

Materials and methods

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional study employing quantitative methods among refugee HIV positive pregnant mothers aged 18–49 years in Kyangwali refugee camp. This study adopted and modified the social ecological model (SEM) [14] to study factors associated with non-adherence to ART among the refugee HIV positive pregnant mothers. The SEM puts into consideration the individual, and their relations to peers, family, community of residence and organization. It therefore considers five levels that is individual/intrapersonal, interpersonal, community, organization and public policy [14]. However, we focused only on the first four levels and did not study any factors related to public policy in this work.

Study setting

This study was conducted between May and June 2023 among refugee HIV positive pregnant mothers aged 18–49 years in Kyangwali refugee camp, Western Uganda. Kyangwali refugee camp lies in Kikuube district in Western Uganda, along Lake Albert at the border between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda. The refugee settlement covers over 90 square kilometers and is divided into 14 villages consisting of 10 to 20 housing blocks each [15]. Top administration of the camp is managed by the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) which retains responsibility concerning on-site settlement management teams and selection of Refugee Welfare Councils. Given its proximity to Eastern Congo, majority of the population is Congolese [15], and as of January 2021 the settlement had over 125,039 people in 42,428 households. Of these, 81% are women and children, and 19% are youth aged between 15 and 24 years [16].

Study population and sampling

A pregnant woman was eligible for the study if she: (1) was aged 18–49 years, (2) had available HIV/PMTCT records at a health facility, and (3) was willing to consent to join the study. An individual was excluded if she: (1) could not speak English, Runyoro or Swahili, and (2) was found admitted at a health facility for any medical condition at the time of the study.

We estimated the sample size of 380 pregnant mothers using both the Leslie Kish and finite population formulae [17, 18]. This was done under the following assumptions: 55% uptake of PMTCT [12] among pregnant mothers a 5% level of precision,95% confidence interval and effect size of 2; achieving more than 90% power. Participants were attached to six health facilities of Kasonga H/C III, Maratatu H/C III, Rwenyawawa H/C III, Kansonga H/C IV, Kyangwali H/C IV, and Rwenyawawa H/C IV. For purposes of representativeness, we employed simple random sampling using computer-generated random numbers and proportion to size sampling for each of the health facilities.

Data collection tool, measurements and procedure

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire administered in face-to-face interviews. The questionnaire included questions on socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge and attitudes about HIV and PMTCT, family/partner, community and organizational related factors, current use and adherence to ART, motivation to continue using ART and reasons for non-use and non-adherence to ART. Use and non-adherence to ART were the dependent variables and were measured by self-reports and verified with drug record availability at the respective health facility reported by the participant. Use was defined as having received a prescription, starting to swallow ART and currently swallowing ART while non-adherence was defined as taking less than 95% of the ART doses (< 29 doses) in the past 30-days before the interview day [11]. Non-adherence was assessed through self-report by asking for the number of ART doses taken in the past 30 days. The study team included the first author (JT), two counsellors, one community linkage facilitator, one Village health team (VHT) team and two research assistants (RAs). All the research team members were experienced in community research work, spoke and read English, Runyoro and Kiswahili. The counsellors had a diploma level of training in Community HIV/AIDS care and management, the RAs had a degree-level training in Environmental Health Sciences, while the community linkage facilitator and VHT had lower secondary school of education. Prior to the start of data collection, RAs were trained for four days on all study procedures to clarify their responsibilities and pre-test the study questionnaire. The counsellors helped in identifying registered pregnant mothers on the PMTCT program from the facility records while the community linkage facilitator and VHT helped in identifying the selected mothers from the refugee camp. The RAs individually administered questionnaires to each participant. At the end of each day, all collected data were reviewed for accuracy and completeness by the study PI (JT).

Statistical analysis

We summarized continuous variables using mean and standard deviation, and used frequencies and percentages for the categorical variables. We defined the outcome (non-adherence to ART) as taking less than 95% of the ART doses (< 29 doses) in the past 30-days before the interview day [11] which we measured on a binary scale as a proportion. We used modified Poisson regression analysis to assess for factors associated with non-adherence to PMTCT and measured associations as prevalence ratios (PR) and their 95% CI. At bivariate analysis, we considered variables with P < 0.20 as significant for multivariate analysis. We also added to the multivariable model variables reported as confounders in literature even if they were not significant at bivariate analysis. Modified Poisson regression model was used because data were cross-sectional and PR were more conservative in magnitude than prevalence odds ratios (POR) for a relatively common outcome, i.e. prevalence > 10% [19, 20]. We checked for correlation and multi-collinearity by conducting a correlation coefficient matrix and a variance inflation factor (VIF) test. We conducted likelihood ratio tests to identify the best fitting model. Adjusted prevalence ratios with P-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

We enrolled 380 participants into the study. Participants had a mean age of 32.1 years, 51.8% were married, 50.3% had attained primary education and 69.5% relied on farming as an occupation. 64.0% had disclosed their HIV status to the partner or family member and 34.2% needed permission from partner or family member to seek for PMTCT services (Table 1).

Only 19.7% belonged to a community support group, majority (98.2%) did their initial HIV testing from the health facility, 26.8% did not receive any counselling before the HIV test and 1.6% did not receive any counseling post the HIV test. More than half (68.7%) mentioned that the transport costs to PMTCT health facilities were not affordable. (Table 2).

Although most (98.7%) participants were using ART, 27.4% did not adhere to ART. (Table 3). About 99.2% intended to deliver from a health facility and 98.7% to continue using ART in the future (Table 3).

At multivariable analysis, non-adherence was significantly associated with one factor under each level of the SEM. The factors were duration of pregnancy at PMTCT initiation, need for permission from partner or family member and attitude of the PMTCT service providers.

Non –adherence to ART was associated with initiating into PMTCT care in the third trimester of pregnancy; aPR 2.06; 95% CI [1.27–3.35], no need to get permission from either partner or family member; aPR1.61; 95% CI [1.07–2.42] and perceived poor attitude of PMCTC service providers; aPR 1.90; 95% CI [1.20–3.01]. Table 4.

Discussion

This study assessed the current use and the factors associated with non-adherence to ART among Refugee HIV positive pregnant mothers aged 18–49 years in Kyangwali Refugee Camp, Western Uganda. The study findings indicate that 98.7% of the pregnant mothers were currently using ART, 99.2% intended to deliver from the health facility and 98.7% intended to continue using ART in the future. However, non-adherence to ART was quite high at 27.4%; and was significantly associated with initiating PMTCT care in the third trimester of pregnancy, no need for permission to seek for PMTCT care and perceived poor attitude of PMTCT service providers.

Our finding of use of ART among pregnant mothers aged 18–49 years at 98.7% is higher than the finding of the Uganda Refugee Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment (RUPHIA) 2021 survey of 87.0%. [3]. The observed difference can be attributed to two factors. Firstly, while the RUPHIA survey was community based and among all refugee settings in Uganda, our study was both facility and community based. It is more likely that participants identified from facility records would be found using ART at the moment. Secondly, while the RUPHIA survey was conducted among the general population, our study was conducted among a special population of pregnant mothers. In comparison to the general population, evidence indicates that the desire to have HIV free infants is likely to positively influence pregnant mothers to use ART [11]. Similarly, our finding of current use of ART is higher than reported in other studies conducted among pregnant mothers in non-refugee settings. [21, 22].

The high levels of current use and intention to continue using ART are promising. However, the observed non-adherence level of 27.4% is worrying since the effectiveness of the PTMTC programs directly depends on the mother’s adherence to ART [10, 11]. The non-adherence observed in our current study is slightly above what Mukose et al. found in a study conducted among pregnant and lactating mothers in Central Uganda [11]. This can partly be explained by the use of a combination of modern health facility and traditional health services among refugees. The use of both services occurs even when there are better health services in stable refugee settings [23]. It is therefore important to build capacities for both modern health facility and traditional health personnel in partnership. More so, such built capacities need to pay attention to education and counselling strategies regarding the importance of adherence to ART.

Our study findings also indicated three factors associated with non-adherence with one factor under each of the three levels of the SEM.

At the intrapersonal/individual level, we found that mothers who initiated their ART/PMTCT care in the third trimester of pregnancy were more likely to be non-adherent. This finding is in line with other previous studies [24, 25]. Literature indicates that late presentation into HIV care poses a higher cumulative risk of HIV transmission to others, less chances of responding to treatment, non-adherence and increased financial strain on health services systems [26, 27]. Similarly, starting PMTCT during the third trimester has significant consequences to both the mothers and the unborn babies. Firstly, the available short time discourages the mother from adhering to achieve viral suppression and increases the risk of transmitting HIV to their child. Secondly, there is no ample time needed to adapt to a new medication routine, deal with the drug related side effects and other psychological aspects that come with the pregnancy and the new HIV diagnosis. It is therefore vital to develop refugee context specific education interventional programs aimed at providing knowledge on the available health care and HIV specific services in the refugee camp to improve the timely consumption of such services. There is also need for assessing other reasons for late utilization of ANC/PMTCT and other related services beyond the individual level.

At the interpersonal level, we found that mothers who did not need to obtain permission from a partner or family member to seek for PMTCT services were more likely to be non-adherent. This finding may seem contradictory, however, the need to obtain permission from a partner or family member in the refugee context may indirectly imply availability of a family support system that not only provides permission to seek for PMTCT services but also social, psychological and financial support to the mother. While family support plays a significant role in ART adherence [28,29,30], evidence indicates that refugee communities usually lack such support due to family separation. Concerns about the need to flee quickly without family, separation in the process of displacement, family members going missing, or substantive barriers to family reunification following safe resettlement in a host country have been reported among refugee communities [31, 32]. Mechanisms to limit family separation during resettling of refugees and creation of strong social and psychological support systems in settlement areas are crucial.

Lastly, at organization level, mothers who perceived the attitude of PMTCT service providers as being poor were more likely to non-adhere to ART. Previous studies have illustrated how health workers’ poor attitudes and non-professional behavior could impinge on clients’ adherence to medications. They have also demonstrated the need to provide good working environments and motivation strategies to health care providers to effectively provide services [33,34,35].

Study limitation

The main limitation of this study is the fact that data was collected by self-report. This could have been subject to recall bias and social desirability bias. However, we limited our recall period to the last thirty days and interviews were conducted maintaining utmost confidentiality and in a conducive environment for participants to provide an honest view. More so, the cross-sectional design of the study restricted our ability to establish causality or temporal relationships among variables and limited generalizability of our study findings due to the snapshot nature of data collection, which captures information at a single point in time. This did not account for changes over time and/or variations across different contexts.

Conclusion

Non-adherence to ART was generally high; therefore limiting the effectiveness of the PMTCT program in this refugee setting. Duration of pregnancy at PMTCT initiation, need for permission from partner or family member and perceived attitude of the PMTCT service providers influenced non-adherence. Refugee context specific education interventional programs, strong social and psychological support systems both from family community and health facilities are vital to improve adherence. Assessing other reasons for late utilization of ANC/PMTCT and other related services beyond the individual level is also needed.

Data availability

All data supporting the results and conclusions of this manuscript are fully available without restriction and are included within the manuscript and its supporting information files.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immunodeficiency syndrome

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- APR:

-

Adjusted Prevalence Ratio

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- CPR:

-

Crude Prevalence Ratio

- EMTCT:

-

Elimination of mother to child transmission

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency virus

- MTCT:

-

Mother to Child Transmission

- PMTCT:

-

Prevention of Mother to child transmission

- TASO:

-

The AIDS Support Organization

- UNAIDS:

-

United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS

- VTC:

-

Voluntary Testing and Counseling

References

WHO. HIV and AIDS key facts. 2023 13th July 2023 [cited 2023 14th Oct 2023]; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids?gclid=CjwKCAjw-KipBhBtEiwAWjgwrD5yn-4fji9ljB8o5mDg6Sz2L1UONVmhJwZJ4yAC41LdSs2-u_7d4xoCxHgQAvD_BwE

UPHIA. Uganda population-based HIV impact assessment (UPHIA) 2020–2021. 2020–2021.

RUPHIA. UGANDA REFUGEE POPULATION-BASED HIV IMPACT ASSESSMENT (RUPHIA 2021). 2021.

Khatoon S, et al. Socio-demographic characteristics and the utilization of HIV testing and counselling services among the key populations at the Bhutanese refugees camps in Eastern Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):535.

O’Laughlin KN, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of home-based HIV testing among refugees: a pilot study in Nakivale Refugee settlement in southwestern Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):332.

Mujyambere P. Barriers to HIV voluntary counselling and testing among refugees and asylum seekers from African Great Lakes region living in Durban. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University; 2012.

Doherty T, et al. If donors woke up tomorrow and said we can’t fund you, what would we do? A health system dynamics analysis of implementation of PMTCT option B + in Uganda. Globalization Health. 2017;13(1):51.

Reeves M. Scaling up Prevention of Mother-to-child transmission of HIV: what will it take? 2011: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Mustapha M, et al. Utilization of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services by adolescent and young mothers in Mulago Hospital, Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):566.

Okonji JA, et al. CD4, viral load response, and adherence among antiretroviral-naive breast-feeding women receiving triple antiretroviral prophylaxis for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Kisumu, Kenya. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(2):249–57.

Mukose AD, et al. What influences uptake and early adherence to option B+ (lifelong antiretroviral therapy among HIV positive pregnant and breastfeeding women) in Central Uganda? A mixed methods study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5):e0251181.

Tudor Car L, et al. The uptake of integrated perinatal prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programs in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e56550.

O’Laughlin KN, et al. A qualitative approach to understand antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence for refugees living in Nakivale Refugee Settlement in Uganda. Confl Health. 2018;12(1):7.

Scarneo SE, et al. The Socioecological Framework: A Multifaceted Approach to Preventing Sport-related deaths in High School sports. J Athl Train. 2019;54(4):356–60.

Naohiko Omata JK. Refugee livelihoods in Kampala, Nakivale and Kyangwali Refugee settlements: patterns of engagement with the private sector. Refugee Studies Centre Oxford Department of International Development University of Oxford; 2013. p. 26. R.S. Centre, O.D.o.I. Development, and U.o. Oxford, Editors.

UNHCR. Uganda - Refugee Statistics January 2021 - Kyangwali. 2021 9th Feb 2021 [cited 2022; https://reliefweb.int/report/uganda/uganda-refugee-statistics-january-2021-kyangwali

Israel GD. Determining sample size 1992.

Kalton G, Heeringa S. Leslie Kish: selected papers. Volume 330. Wiley; 2003.

Bastos LS, R.d.V.C.d. Oliveira, and, Velasque LdS. Obtaining adjusted prevalence ratios from logistic regression models in cross-sectional studies Cadernos de saude publica, 2015. 31: pp. 487–495.

Behrens T, et al. Different methods to calculate effect estimates in cross-sectional studies. Methods Inf Med. 2004;43(05):505–9.

Huang Z, et al. The uptake of prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programs in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0135068.

Price AJ, et al. Uptake of prevention of mother-to-child-transmission using option B + in northern rural Malawi: a retrospective cohort study. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(4):309–14.

Kirkcaldy EM. The development of programme strategies for integration of HIV, food and nutrition activities in refugee settings. World Health Organization; 2006.

Kadima N et al. Evaluation of non-adherence to anti-retroviral therapy, the associated factors and infant outcomes among HIV-positive pregnant women: a prospective cohort study in Lesotho. Pan Afr Med J, 2018. 30(1).

MacCarthy S, et al. Barriers to HIV testing, linkage to care, and treatment adherence: a cross-sectional study from a large urban center of Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2016;40(6):418–26.

Egger M, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9327):119–29.

Abaynew Y, Deribew A, Deribe K. Factors associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in South Wollo ZoneEthiopia: a case-control study. AIDS Res Therapy. 2011;8(1):8.

Nabunya P, et al. The role of family factors in antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence self-efficacy among HIV-infected adolescents in southern Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):340.

Nabunya P, Samuel K, Ssewamala FM. The effect of family support on self-reported adherence to ART among adolescents perinatally infected with HIV in Uganda: a mediation analysis. J Adolesc. 2023;95(4):834–43.

Knight L, Schatz E. Social Support for Improved ART Adherence and Retention in Care among older people living with HIV in Urban South Africa: a Complex Balance between Disclosure and Stigma. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18):11473.

Liddell BJ, et al. Understanding the effects of being separated from family on refugees in Australia: a qualitative study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2022;46(5):647–53.

Wickes R et al. The social impacts of family separation on refugee settlement and inclusion in Australia: Executive Summary 2018.

Adeniyi OV, et al. Factors affecting adherence to antiretroviral therapy among pregnant women in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Volume 18. BMC Infectious Diseases; 2018. p. 175. 1.

Opara HC, et al. Factors affecting adherence to anti-retroviral therapy among women attending HIV clinic of a tertiary health institution in SouthEastern, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2022;22(1):456–64.

Isabirye R et al. Factors Influencing ART Adherence Among Persons Living with HIV Enrolled in Community Client-Led Art Delivery Groups in Lira District, Uganda: A Qualitative Study HIV/AIDS-Research and Palliative Care, 2023: pp. 339–347.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the management of Kyangwali Refugee camp for their support and collaboration. We would also like to thank the research assistants namely John Vianney Alinda and Wilson Mutenga, the rest of the data collection team members and study participants for their efforts during the data collection exercise.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center, National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute of Mental Health, of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43 TW011304. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the “National Institutes of Health”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JT, JN and MM conceived the concept. All authors co-designed the study, consulted on data collection, data management and statistical analyses, interpreted results and contributed to the first draft of the manuscript, JT managed data collection and conducted the analyses. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

We obtained ethical approval to conduct the study from The AIDS Support Organization (TASO) Research Ethics Committee (REC) under reference number TASO-2022-189 and from Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (UNCST) under reference number HS2711ES. We also obtained administrative permission to conduct the study from the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) and permission to review health facility records from the health facility top management and unit in-charges. We obtained written informed consent from all study participants (who either provided a signature or a thumbprint after receiving explanation of the purpose of the study), including publication of anonymized responses and the participants’ rights. All refugee pregnant mothers were left with a copy of the written informed consent form. All signed or thumb-printed consent forms, audio recordings, and filled tools were stored securely in a locked file cabinet, with access limited to only authorized personnel on the study team. All procedures in this study were applied in accordance with the standards and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tusabe, J., Nangendo, J., Muhoozi, M. et al. Use and non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy among Refugee HIV positive pregnant mothers aged 18–49 years in Kyangwali refugee camp, Western Uganda. AIDS Res Ther 21, 54 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-024-00645-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-024-00645-0