Abstract

The dimensionless thermoelectric figure of merit and magnetic field production ability of “natural” nanostructures–layered ternary alloys (TA) of the family [(Ge, Sn, Pb)(Te, Se)]m [(Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)3]n, with non-isovalent cationic substitution (Ge, Sn, Pb ↔ Bi, Sb) are investigated. In the transition from binary alloys (BA) to TA, we observed the formation of the phase “phonon glass–electronic crystal” (PGEC) and its subsequent degeneracy, accompanied by sharp increase in the carrier densities in the samples. As a result, the size ZT of samples went down, and the size X substantially increased, which speaks in the work to formation of a degenerated PGEC phase under non-isovalent cationic substitution in the samples. Comparison with known thermoelectric materials (ТEMs) (metals, semimetals, and semiconductors) used for production of magnetic fields H in contours of short-circuited ТC has shown that the investigated TA forms a new class of TEMs for magnetic field production with raised values of parameters X and Y.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Presently, direct transformation of thermal energy into electric energy is performed using various thermoelectric transformers (TET): generators, coolers, and heaters. Active elements of TET are represented by thermocouples (TC), which consist of branches of hole (p-type) and electron (n-type) conductivity forming a p–n transition. Manufacturing of p- and n-branches involves various metallic, semimetallic, and semiconducting thermoelectric materials (TEM) [1–3].

The efficiency of TEM operation is defined by the parameter of dimensionless thermoelectric figure of merit ZT, which defines the efficiency of transformation of energy η in TET

where A = α2σ is a parameter of thermoelectric power; α is the differential thermo-EMF; σ = ρ–1 is the specific electrical conductivity; ρ is the specific electrical resistance; κ = κph + κe is the specific thermal conductivity; κe and κph are the electron and phonon (lattice) components of thermal conductivity, respectively; and T is the absolute temperature [4].

The principle of universality of parameter ZT is maintained for most operating regimes of TET (regime of maximum power Wmax, regime of maximum efficiency ηmax, etc.). An exception is regime of maximum current Imax, which is used for obtaining magnetic fields in contours of short-circuited TC [5]. According to [5], in Imax regime, the efficiency of transformation of thermal flux into electric current Q → I for small temperature differences ΔT is described by the “current coefficient” (CC)

where j = I/S and q = Q/2S are the densities of electric current I and thermal flux Q through TC, respectively; S = Sp = Sn; Sp and Sn are the cross section of the p- and n-legs; Y = \(\left| \alpha \right|\frac{\sigma }{\kappa } = \frac{Z}{\alpha }\) is a parameter of magnetic field production ability of TEM; α = αp and α = |αn| are for materials of p- and n-type of conductivity; and α = αp – αn is for TC as a whole. The Imax regime takes a special place in thermoelectricity (TE) and its applications. It is related to the first observation of TE phenomenon in TC Bi/Cu and Sb/Cu (T. Seebeck, 1821) (Fig. 1) [6] as well as to obtainment of unprecedented magnetic fields (H to 105 A/m and greater) in fluxes of high-temperature plasma (Fig. 2) [5, 7–9]. The advantage of TC in obtaining magnetic fields H over permanent magnets and electromagnets is connected with the absence of the Curie temperature in TC and external source of current, respectively [7, 8].

Seebeck experiment on the observation of thermoelectricity (1821). Thermocouple legs: K—Cu; B—Bi. (Here sn is the magnetic needle; N and S are geographical “north” and “south”) [6].

Construction of thermocouple based on metallic materials for obtaining strong magnetic fields H in high-temperature plasma flows (I > 103 A, H > 105 A/m) [5].

Equivalent circuit of a short-circuited TC operating in Imax regime is presented in Fig. 3. Passing of thermal flux Q by heat chain of TC (2) (Fig. 3) causes appearance of current I in its electric circuit (1). In turn, the magnetic field of current H ⊥ I appears in the contour of TC, whose value depend on shape of the contour, its area S, and the number of windings N (Fig. 3) [10]. The electric current of TC is equal to

Equivalent circuit of the short-circuited thermocouple. Notation: R1, R2 and \(R_{1}^{T}\), \(R_{2}^{T}\) are electrical and thermal resistances of the legs, \(R_{i}^{T}\) is inner thermal resistance of heater, Q0 and Q1 are input and output heat flows, and E = αΔT1 is the electrical voltage of the thermocouple. Circuits of thermocouple: (1) electric, (2) thermal.

the absolute value of the magnetic field in the center of TC for a rectangular contour is

where ln and lp are the height of branches, a and b are the sides of the rectangle, and ΔT = (T2 – T1) and ΔT1 = (T3 – T1) are the initial and operating temperature differences [10]. Attainment of the Imax regime requires optimization of electric

and thermal circuits of TC

consisting of n- and p-branches connected to each other sequentially and in parallel, respectively (Fig. 3). At the same time, for agreement with internal thermal resistance of heater \(R_{i}^{T}\), the total thermal resistance of TC is selected in accordance with Lenz’s law

which provides maximum thermal pressure Q0ΔT1 on branches (Fig. 3) [4, 11–13].

Expressions (1) and (2) imply that high values of ZT do not guarantee high values of parameter X of TEM. In [5] it was noted that, in view of parameter X, some metal alloys may exceed semiconductors with ZT greater by an order of magnitude, especially in the domain of high temperatures [6]. Reduction of parameter X in TEM with high values of ZT is connected with the effect of the Le Chatelier–Braun principle, which leads to decreasing ΔТ1 owing to Peltier effect taking place during flow of current I in short-circuit TC [4, 9]. In this way, creation of TE sources of I and H requires special optimization of TEM with respect to parameter X, which is different from standard optimization with respect to parameter ZT [1, 5].

Earlier a series of new physical phenomena [14–16] (selective disordering of cation and (or) anion sublattices causing simultaneous amorphous behavior of lattice thermal conductivity κph and electrical conductivity σ) was observed in narrow-gap semiconducting materials—layered ternary alloys (TA) of family [(Ge, Sn, Pb)(Te, Se)]m [(Bi, Sb)2(Te,Se)3]n (m, n = 0, 1, 2, …) with non-isovalent cationic substitution (Ge, Sn, Pb ↔ Bi, Sb). TA are also characterized by “concentration collapse” (CC)—sharp increment of concentration of electrons (holes) n(p) = 1019 → (2–5) × 1020 cm–3 as compared with binary alloys (BA) (m, n = 0) [16]. The mentioned phenomena in TA do not occur for isovalent replacement Ge ↔ Pb ↔ Sn and Bi ↔ Sb [16]. Such phenomena were explained by formation of phase “phonon glass–electronic crystal” (PGEC) in TA [17]:

and its degeneration (PGEC → phonon glass–electronic glass) [14–16]:

where \({{\lambda }_{{{\text{ph}}}}} = \frac{{3{{\kappa }_{{{\text{ph}}}}}}}{{CV}}\) and \({{\lambda }_{{\text{e}}}} = {{\nu }_{{\text{F}}}}\left\langle \tau \right\rangle \) = \(\hbar {{\left( {\frac{{3{{\pi }^{2}}n}}{{{{N}^{2}}}}} \right)}^{{{1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 3}} \right. \kern-0em} 3}}}}\frac{\mu }{e}\) are the mean free paths of phonons and electrons in the samples, a ~ 0.3 nm is the shortest interatomic distance, V ~ 3000 m/s is characteristic value of sonic speed in solid bodies, C = \(\frac{{{{C}_{{{\text{mol}}}}}d}}{M}\) is the heat capacity of unit volume, Сmol is the molar heat capacity, d is the density, M is the molecular mass, νF is the Fermi velocity, 〈τ〉 = \({{\tau }_{0}}{{E}^{{r - {1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}} \right. \kern-0em} 2}}}}\) is the average relaxation time of electrons with respect to energy E, r is a scattering parameter, τ0 is a factor which does not depend on energy, n is the concentration of carriers, N = \({{\left( {\frac{{{{m}_{{\text{d}}}}}}{{{{m}_{{\text{c}}}}}}} \right)}^{{{3 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {3 2}} \right. \kern-0em} 2}}}}\) is the number of extrema in the zone, mc, md, and μ are effective masses of conductivity, state density, and mobility of electrons, and e is the elementary charge) [18, 19].

Earlier two TA, of the researched family (GeTe)m(Bi2Te3)n and PbBi2(Te1 – xSex)4 + δ, which belong to the degenerated phase of PGEC (expression (5)), showed increased values of magnetic field production coefficients X and Y. As a result the alloys turned out to be promising TEM, which are appropriate for obtaining large magnetic fields H in contours of short-circuited thermocouples [14, 15].

The aim of this work is to (1) search for new TEM with high values of coefficients X and Y among other TA of the family; (2) explain high values of magnetic field production ability of TA, which are reached in degenerated PGEC phase of TA; (3) determine the place of researched TA among other groups of TEM (metals, semimetals, and semiconductors) with magnetic field production.

EXPERIMENTAL

In the investigations, we used layered polycrystalline ternary alloys (TA): 1—(GeTe)m(Bi2Te3)n; 2—(GeTe)m(Sb2Te3)n; 3—(SnTe)m(Bi2Te3)n; 4—(PbTe)m(Bi2Te3)n; 5—(PbSe)m(Bi2Se3)n; and 6—(PbTe)m(Sb2Te3)n, with trigonal (1–4, 6) or monoclinic (5) symmetry (Table 1) [14–16]. Alloys were synthesized from high-purity components (content of the main substance not less than 99.999 at %) in vacuum quartz ampules at temperature T = 1020–1190 K, which were then cooled to 770 K at rate of 4 K/min. The obtained samples were burned at temperature of 770 K for 200–400 h and then annealed in water with ice. After annealing, the average size of crystalline grain constituted 50–100 μm.

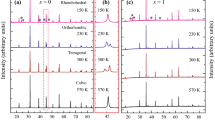

X-ray studies [14, 15] showed that the obtained layered TA represent natural nanostructures with discrete nanospectrum ξ = ξ1; ξ2, which appears spontaneously during crystallization of TA and maintains its stability in the whole temperature interval up to temperature of melting of compounds (Tm ~ 900 K). Here ξ1 = 1–3 nm is the thickness of layer packets; ξ2 = 2–20 nm is the period of superstructures forming in TS depending on their content (m, n). Nanospectra ξ = ξ1; ξ2 of the researched family of TA partially superimpose on one another and together cover the interval Δξ = 1–20 nm, which is the most interesting for thermoelectric applications of materials [18].

Thermoelectric parameters α, σ, and κ of alloys were measured by a stationary method on the facilities of the Ioffe PTI Laboratory (St. Petersburg) for temperature difference ΔT ≤ 10 K using samples with sizes of 7 × 7 × 15 mm3 with accuracy of 3, 3, and ~10%, respectively. In this work we determined the following: the type of conductivity of samples by sign of α; concentration of current carriers in samples from measurements of Hall coefficient RH = \(\frac{{{{A}_{{\text{H}}}}}}{{ne}}\) performed on the basis of the difference frequency (current I = 0.2 A of frequency f1 = 72 Hz, magnetic field with induction В = 0.5 T with frequency f2 = 50 Hz) on both samples with size of 1.5 × 5 × 15 mm3 with accuracy of ~2% (here AH ~ 1 is the Hall factor, and n the concentration of current carriers); Hall mobility of current carriers in samples from the correlation μn,p = Rσ; thermal conductivity of crystalline lattice κph = κ – κe from experimental quantities κ and σ (Table 1), and using the Lorentz formula κe = LTσ (L = 2.45 × 10–8 (W Ω/K2 is the Lorentz number corresponding to case of strong Fermi degeneration of electrons (holes) \(\frac{{{{E}_{{\text{F}}}}}}{{{{k}_{0}}T}}\) > 4, EF is the energy of the Fermi level, and k0 is the Boltzmann constant) [2].

The width of the band gap of TA Eg was estimated by Vergard’s law from the correlation

using known values \(E_{g}^{A}\) and \(E_{g}^{B}\) of BA [20, 21]. The energy of the Fermi level EF counted from the edges of the zones of conductivity and valent for samples of n- and p-type conductivity, respectively, was determined by the method of thermo-EMF for the case of acoustic scattering of electrons in samples (r = 0). The effective masses of state density

were computed on the basis of the found values of n, p, and EF (h = 1.0542 × 10–27 erg/s is the Planck constant, and m0 = 9.1 × 10–28 g is the mass of electron) [2]. Correlations (4) and (5) were used as conditions of PGEC phase formation and its degeneration.

RESULTS OF INVESTIGATIONS

Tables 1 and 2 present the results of investigations for thermoelectric properties and zone structure of BA and TA of family [(Ge, Sn, Pb)Te]m[(Bi, Sb)2(Te,Se)3]n. Figures 4–6 show results of statistical processing of the obtained data. Dashes in Figs. 4–6 show parameters of “mother” BA (Bi2Te3) (crosses); dots correspond to statistical linear trends (SLT) (basic tendencies) of the studied dependences with respect to kinetic and zone parameters of TA.

Dependence of the carrier density n(p) on the composition of the TA. (1) (GeTe)m (Bi2Te3)n; (2) (GeTe)m (Sb2Te3)n; (3) (SnTe)m (Bi2Te3)n; (4) (PbTe)m (Bi2Te3)n; (5) (PbSe)m (Bi2Se3)n; (6) (PbSe)m (Sb2Se3)n. Conductivity type: p—1 (for n/(n + m) < 0.5), 2, 3; n—1 (for n/(n + m) > 0.5), 4, 5 (T = 300 K).

The dependences of parameters n, p, and ZT on the content of BA and TA are presented in Figs. 4 and 5. It can be seen in Fig. 4 that values of n and p increase by ~10–27 times during transition BA → TA (shown with arrows) and exceed values optimal for reaching (ZT)max of TEM (n, p)opt ~ 1 × 1019 cm–3 for T = 300 K [1, 23]. At the same time, the value ZT of TA decreases by 4–10 times as compared with Bi2Te3 (Fig. 5) [2, 24]. In turn, the magnetic field production coefficients of BA and TA vary in wide ranges: Y = 0.12–10.32 1/V and X = 0.12–8.27 1/V; their average values for TA are \(\bar {Y}\) ~ 3.62 1/V and \(\bar {X}\) ~ 3.22 1/V (Table 1, Fig. 6). In addition, the largest values of parameter X were observed for TA of the following groups: 1—\(\bar {X}\) ~ 4.25 1/V; 4—\(\bar {X}\) ~ 2.84 1/V; 5—\(\bar {X}\) ~ 2.84 1/V. The best parameters among all the studied TA of the family belong to samples p-Ge4Bi2Te7 (X ~ 7.15 1/V), n-Ge2Bi10Te17 (X ~ 6.11 1/V), and p-SnBi2Te4 (X ~ 7.08 1/V) (T = 300 K) (Table 1).

Dependences of the dimensionless thermoelectric figure of merit ZT on the composition of the TA (T = 300 K). For notation, see Fig. 4.

Dependences of the magnetic field production ability coefficients Y and X on the composition (a, b) and the thermoelectric figure of merit ZT on Y and X of ТA (с, d) (T = 300 K). For notation, see Fig. 4.

Analysis of dependences Y, X = f(ZT) obtained for TA of the family showed the presence of SLT Y, X ~ ZT (dash) (Figs. 6c and 6d). The mentioned dependences are described by functions (1) and (2) taking correlation ZT\( \ll \) 1 observed in TA into account (Table 1, Fig. 5). At the same time, the values of parameter Y for all TA do not exceed the corresponding values for Bi2Te3 (Fig. 6c); however, for some TA, we have X(ТС) > X(Bi2Te3) (Fig. 6d), which is described by formula (2) taking correlation ZT(ТС) \( \ll \)ZT(Bi2Te3) into account (Table 1, Fig. 5). In this case, the wide scatter with respect to the content of parameters X, Y = f[n/(n + m)] of TA (Figs. 6а and 6d) is explained by differences of zone structure, degree of degeneration of PGEC phase, and degree of Fermi degeneration of samples (Table 1) [24].

Table 2 presents the computation of zone parameters and mean free paths of phonons and electrons (holes) in TA of the family. It can be seen that all the studied TA represent narrow-gap semiconductors with Fermi energy EF > 0, which belongs to the valence band (р-type) or conduction band (n-type). As a result, Fermi degeneration of current carriers in TA turns out to be strong even at room temperature \(\frac{{{{E}_{{\text{F}}}}}}{{{{k}_{0}}T}}\) ~ 4–7. Figure 7 presents schemes of zone (band) structure (BS) of TA (d) as compared with BS of metals (a), semimetals like Bi (b), and narrow-gap semiconductors like Bi2Te3 (c). According to Table 2, all the studied TA except strong Fermi degeneration belong to the PGEC phase, which is also close to degeneration already at room temperature (PGEC → “phonon glass–electron glass”) (formulas (4) and (5)).

Table 3 and Fig. 8 present SLT results for dependences dX/dB on kinetic and zone parameters of TA (B = α, σ, κ, κlat, μ, μ/κlat, EF, m/m0) (Tables 1 and 2). The obtained characteristics of TA (Table 3) had various signs and values. Positive signs of SLT of X by parameters B = α, σ, κ, κlat, μ, μ/κlat, EF, m/m0 are typical of dimensionless thermoelectric quality ZT of TEM [1] and are explained by dependence Y ~ ZT (formula (2)). In turn, negative values of SLT of X with respect to parameters B = λph/α and κe/α correspond to formation of PGEC phase in TA; at the same time, small values of coefficient dX/dB (B = λe/α) point to strong degeneration of PGEC phase in samples (formula (5)).

Dependences of the magnetic field production ability coefficient X: (a) on the band gap Eg, (b) carrier density n(p) of the TA (T = 300 K). For notation, see Fig. 4.

The signs of SLT of X with respect to parameters B = Eg, n, p were also negative, which is explained by growth of temperature of the maximum of parameter X – Tmax = Т(X = Xmax) with growth of Eg as well as possible exceeding of optimal values of parameters n, p. Thus maximum values of X and Y at room temperature were reached firstly in TA with small values of Eg and n, p (Table 1). On the other hand for TA with increased values of Eg, parameters X and Y had lowered values at room temperature, but they increased with growth of temperature [15]. The maximum values Xmax and Ymax reached in these alloys in the zone of high temperatures were estimated using empirical dependences Tmax = f(Eg) [17] and Xmax = CX300 K (Tmax – 300 K) for C ~ 0.01 (V K)–1 [15], respectively. The results of estimates of Tmax and Xmax are presented in Table 2. It can be seen that increment of Eg causes additional growth of parameter Xmax of TA and shifting toward the interval of high temperatures. As a result, according to the estimate, 29 samples of 48 may reach high values of Xmax ≥ 4 in the temperature range T = 300–500 K, which is of practical interest (Table 2).

The performed estimates show that increased values of Xmax in TA (Tables 1 and 2) are due to decreased values of κph and ZT and increased concentration of carriers n, p in samples typical of degenerated PGEC phase [11–13]. The general pattern of phenomena accompanying transition BA → TA and formation of PGEC phase in samples is explained qualitatively in Fig. 9 [18, 23]. Curve 3 in Fig. 9 corresponds to the known concentration dependence ZT = f(n, p) with maximum for n, p ~ 1019 cm–3 obtained by numerous authors [1, 23] taking the curvature of dependences α, σ, and κ = f(n, p) into account (Fig. 9, curves 2, 7, 8). At the same time, maxima of A and Y obtained by the same method turn out to be shifted toward larger concentrations of current carriers n(p) (Fig. 9, curves 4 and 5) [18, 23]. The transition crystal → PGEC under condition λe = const does not change the value of parameter A (curve 4); however, it leads to increasing (ZT)max and Ymax by absolute value as well as to shifting of maxima toward smaller n, p (Fig. 9, curves 3 → 1 and 6 → 5). In turn, degeneration of PEGC phase simultaneously decreases the values of ZT and Y (Fig. 9, curves 1 → 12, 5 → 11), which generally does not strongly change the value of parameter Xmax (correlation (2)).

It is necessary to note that growth of n, p in TA of the family (Tables 1 and 2) occurs spontaneously as a result of development of concentration instability of crystals (CC) (Fig. 9, curve 3 → 6). In addition formation of PGEC phase (λph/α → 1) and its degeneration (λe/α → 1) causes decrement of κph (Fig. 9, curves 9 → 10) and ZT (curves 3 → 1 → 12), which correspondingly increases the magnetic field production coefficient X of TA (Tables 1 and 2).

DISCUSSION

In this work we searched for new TEM with high values of magnetic field production coefficients X and Y among 48 layered TA—“natural” nanostructures of family [(Ge, Sn, Pb)(Te, Se)]m[(Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)3]n with non-isovalent cationic substitution (Ge, Sn, Pb ↔ Bi, Sb). Alloys p-Ge4Bi2Te7 (X ~ 7.15 1/V), n-Ge2Bi10Te17 (X ~ 6.11 1/V), and p-SnBi2Te4 (X ~ 7.08 1/V) showed the best characteristics at room temperature (T = 300 K). It was shown that 29 of 48 samples studied in the work may reach values Xmax ≥ 4 with growth of temperature within the range T = 300–500 K, which is of practical interest (Table 2).

It was established that the increase in values of Xmax in TA of family (Tables 1 and 2) is connected with decreased values of κph and ZT and increased concentrations of carriers n, p in samples typical of degenerated PGEC phase [11–13]. In addition, the reason for degeneration of PGEC phase in TA of the studied family was established—disordering of cation sublattices and formation of mixed cation layers with non-isovalent replacements (Ge, Sn, Pb ↔ Bi, Sb), which lead to simultaneous strong scattering of phonons and electrons in samples [14, 15]. As a result, selective scattering of phonons (strong) and electrons (weak) typical of PGEC phase is violated and “amorphous-like” behavior for both thermal conductivity of crystalline lattice κph and electrical conductivity σ of samples is observed simultaneously in degenerated PGEC phase of TA [14, 15].

The described mechanisms of growth of parameters X and Y were not known earlier, which allows assigning the studied TA to a new group of TEM for magnetic field production—narrow-gap semiconductors belonging to degenerated PGEC phase [24].

Table 4 presents the electrophysical and thermal properties as well as zone parameters and limited operating temperature Тmax of various groups of TEM (metals and alloys, semimetals, and semiconductors) with magnetic field production in comparison with PGEC samples [25–27]. Parameters λph/a and λe/a for samples (Table 4) were computed by the same methodology as for TA [19].

Materials (Table 4) differ with respect to zone structure (Fig. 7) and their closeness to PGEC phase (correlations (4) and (5)); correspondingly, the mechanisms of growth of parameters X and Y, as well as operating intervals of temperatures in them, differ significantly. In this way, high values of X and Y of a number of metals and alloys (chromel, alumel, constantan, and others) are connected with high values of α and σ, which are defined by the complicated shape of Fermi surface, high values of n, p, and low values of ZT (Table 4). At the same time, for metals with low values of α (such as Cu), we have X ~ Y ~ 0 (Table 4), which points to their complete uselessness as TEM with active magnetic field production [14, 26]. Such metals possessing high values of σ are widely used as auxiliary materials for creating current contours in short-circuit TC, including TC with increased number of current windings (N ≥ 1) (Figs. 1, 2) [9].

Comparison of metallic and semiconducting TEM (Table 4) shows that metals are second to semiconductors like Bi2Te3 in values of X and Y at room temperature. At the same time, metallic TEM have significantly higher operating temperature \(T_{{\max }}^{*}\) ~ 1200 K than narrow-band semiconductors and semimetals (\(T_{{\max }}^{*}\) < 600 K) (Table 4), which allows using them for significantly large temperature differences ΔT. Integral EMF of metallic thermocouples for large ΔT is computed by the Avenarius formula (1865)

where α = αp – αn, αp and αn are the Seebeck coefficients of thermocouple and branches of p-type and n‑type of conductivity, t2 > t1 are the temperatures of the hot and cold and hot junctions of TC, and b, c, and β are coefficients differing for various materials [15, 28].

According to formula (6), an increase in EMF E with growth of temperature (β ≥ 0) (thermocouples Ni, Ir, Au–Fe) or attainment of the maximum with subsequent decrease and change of sign (β < 0) (thermocouples Cu–Fe, Mo—Fe, and others) is observed in metallic TC depending on the value of coefficient β [11]. As a result, only in the last case, the operating interval of metallic thermocouples turns out to be limited. On the other hand, in the case of narrow-gap semiconductors and semimetals, there are more significant limits of operating interval of temperatures ΔT connected with development of self-conductivity and in a number of cases even with low temperature of melting of samples (such as Bi) (Table 4). Thus metallic TEM are primarily used in the domain of high temperatures (Fig. 2), and semiconductors and semimetals are used near room temperature [5, 27].

According to Table 4, the highest values of parameter Y ~ ZT are observed in degenerated semiconductors such as Bi2Te3 with high thermoelectric quality (ZT ~ 1, T = 300 K). At the same time, owing to high values of ZT, parameter X of Bi2Te3 significantly decreases (Y < X); as a result, it becomes second to that of a number of studied TA (Table 4). The transition BA → TA also causes expansion of the operating temperature interval of TEM due to growth of Eg of samples (Table 2). In addition, the studied TA of family have one more essential advantage as compared with alloys such as Bi2Te3. Owing to low κрh, the condition of agreement of thermal resistances of thermocouple with internal thermal resistance of heater (3) is fulfilled in TA at lower height of branches. This allows significant saving of expenses on expensive TEM (up to 5 times and more) during production of TC [18, 28].

Semimetals such as Bi with electron spectrum transient from metals to semiconductors (so called “Dirac cone”) are especially distinguished among TEM with magnetic field production (Table 4, Fig. 7b) [29, 30]. According to Table 4, high values of X and Y of semimetals (such as Bi)are defined by high values of parameters α and μ as well as low values of κ connected with peculiarities of BS and large atomic mass (M = 238.98 g) as well as layered structure of crystals (Table 4) [26]. Since the concentration of current carriers in semimetals such as Bi is significantly less than optimal (Fig. 9), high values of X and Y in them are reached by means of spontaneous formation of PGEC phase in samples (1 ~ λph/a\( \ll \) λe/a) (Table 4). In this way, the mechanisms of growth of X and Y in semimetals (such as Bi) and TA turn out to be similar. The parameter of “quality” of PGEC phase in semimetals such as Bi reach an unprecedented value λe/λph ~ 635 (Table 4). Thus, it is a small wonder that T. Seebeck discovered thermoelectricity on TC with branches from Bi [6].

According to [29, 30] special BS (like “Dirac cone”) (Fig. 7b) may characterize not only Bi but also surface layers of a number of its compounds—so-called “topological insulators,” which, in particular, include TA of the family (Table 1). Thus further increase in parameters X and Y of semiconducting TEM with magnetic field production may be connected with either optimization of the degree of degeneration of PGEC phase and Fermi degeneration of current carriers or the use of the contribution of surface states to the properties of semiconducting films.

CONCLUSIONS

1. A new class of thermoelectric materials (TEM) of “natural” nanostructures with magnetic field production is discovered—layered ternary alloys of family [(Ge, Sn, Pb)(Te, Se)]m [(Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)3]n with non-isovalent cationic substitution.

2. It is shown that high magnetic field production ability of ternary alloys of the family (X from 6–8 1/V) is due to formation of degenerated phase “phonon glass–electronic crystal” (PGEC) in alloys with high concentration of current carriers p, n > 1020 cm–3 and low thermal conductivity κ = (4–6) × 10–3 W/(cm K) and thermoelectric quality ZT ~ 0.1.

3. The operating interval of temperatures of ternary alloys (T ~ 300–700 K) turns out to be significantly expanded as compared with Bi2Te3 (T ~ 200–400 K) owing to increase in the width of the band gap Eg. At the same time, low thermal conductivity κ of ternary alloys as compared with Bi2Te3 allows significant saving of expenses on expensive semiconducting materials (up to 5 times and more) during the process of required agreement of thermal resistances of TC and heater.

REFERENCES

Ioffe, A.F., Semiconductor Thermoelements and Thermoelectric Cooling, London: Infosearch, 1957.

Gol’tsman, B.M., Kudinov, V.A., and Smirnov, I.A., Poluprovodnikovye termoelektricheskye materialy na osnove Bi 2 Te 3 (Semiconductor Thermoelectric Materials Based on Bi2Te3), Moscow: Nauka, 1972.

Goldsmid, H.J., Introduction to Thermoelectricity, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2016.

Okhotin, A.S., Efremov, A.A., Okhotin, V.S., and Pushkarskii, A.S., Termoelectricheskie generatory (Thermoelectric Generators), Moscow: Atomizdat, 1976.

Plekhanov, S.I. and Terekov, A.Ya., The contibution of corresponding member of Russian Academy of Sciences N.S. Lidorenko into the development of thermoelectricity in Russia, in Nikolai Stepanovich Lidorenko (Nikolai Stepanovich Lidorenko), Moscow: Kvant, 2011, pp. 3–25.

Seebeck, T.J., Magnetische Polarisation der Metalle und Erze durch Temperatur-Differenz, Leipzig: Engelmann, 1895.

Putilov, K.A., Kurs fiziki (Course of Physics), Moscow: Fizmatlit, 1963, vol. 2.

Pozdnyakov, B.S. and Koptelov, E.A. Termoelectri-cheskaya energetika (Thermoelectric Power), Moscow: Atomizdat, 1974.

Korzhuev, M.A., Katin, I.V., and Nyhezina, I.Yu., Own electromagnetic fields of thermoelements and the possibility of their reduction until safe limits, Materialy XIV Mezhgosudarstvennoi konferentsii “Termoelektriki i ikh primeneniya–2014” (Proc. XIV Int. Conf. “Thermoelectrics and Their Applications–2014”), St. Petersburg: Peterb. Inst. Yad. Fiz., 2014, pp. 245–250.

Yavorskii, B.M. and Detlaf, A.A., Spravochnik po fizike (Handbook of Physics), Moscow: Nauka, 1964.

Korzhuev, M.A., Kretova, M.A., and Katin, I.V., Contribution of the academician E.Ch. Lents to the development of modern thermoelectricity, Termoelektri-chestvo, 2017, no. 1, pp. 5–18.

Lents, E.Kh., Izbrannye trudy (Selected Works), Moscow: Akad. Nauk SSSR, 1950, pp. 361–449.

Korzhuev, M.A., The Lents rule for thermoelectric energy converters operating in maximum power model, Materialy XIV Mezhgosudarstvennoi konferentsii “Termoelektriki i ikh primeneniya–2014” (Proc. XIV Int. Conf. “Thermoelectrics and Their Applications–2014”), St. Petersburg: Peterb. Inst. Yad. Fiz., 2014, pp. 447–452.

Korzhuev, M.A., Kretova, M.A., Avilov, E.S., and Mikhailova, A.B., Intrinsic nanoidentity and physical properties “natural” nanostructures–layered crystals (Ge, Sn, Pb)Te]m [(Bi, Sb)2(Te, Se)3]n (m, n = 0, 1, 2 …), Trudy Rossiisko-Kitaiskogo simpoziuma “Novye materialy i tekhnologii” (Proc. Russian-Chinese Symp. “New Materials and Technologies,” Solntsev, K.A., Ed., Moscow: Interkontakt Nauka, 2015, vol. 1, pp. 276–280.

Avilov, E.S., Korzhuev, M.A, Kretova, M.A., and Mikhailova, A.B., Thermoelectric figure of merit and magnetic field production abilities of “natural” PbBi2(Te1 – xSex)4 + δ and PbBi4(Te1 – xSex)7 + δ nanostructures, Inorg. Mater.: Appl. Res., 2016, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 177–186.

Korzhuev, M.A., Charge-carrier density collapse in layered crystals of the family [(Ge,Sn,Pb)(Te,Se)]m [(Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)3]n (m, n = 0, 1, 2…), Semiconductors, 2017, vol. 51, no. 7, pp. 924–927.

Slack, G., New materials and performance limits for thermoelectric cooling, in CRC Handbook of Thermoelectrics, Rowe, D.M., Ed., Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1995, pp. 407–440.

Korzhuev, M.A., Thermoelectric nanostructures: pros and cons, Termoelektrichestvo, 2013, no. 5, pp. 10–21.

Korzhuev, M.A. and Katin, I.V., Diagnostics of the phase “phonon glas–electron crystals” (PGEC) in thermoelectric materials, in Physics, Chemistry and Application of Nanostructures, Singapore: Word Scientific, 2015, pp. 107–110.

Kiselyova, N.N., Dudarev, V.A., and Korzhuyev, M.A., Database on the bandgap of inorganic substances and materials, Inorg. Mater.: Appl. Res., 2016, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 34–39.

Kretova, M.A. and Korzhuev, M.A. Estimation of the band gap of a series of new thermoelectric materials, Semiconductors, 2017, vol. 51, no. 7, pp. 902–905.

Korzhuev, M.A, Mihajlova, A.B., Kretova, M.A., and Avilov, E.S., Analysis of the crystal structure of alloys of the family [(Ge, Sn, Pb)(Te, Se)]m [(Bi, Sb)2(Te,Se)3]n (m, n = 0, 1, 2 …) within the theory of closely packed spheres, Semiconductors, 2017, vol. 51, no. 8, pp. 969–971.

Snyder, G.J. and Toberer, E.S., Complex thermoelectric materials, Nat. Mater., 2008, vol. 7, pp. 105–114.

Korzhuev, M.A., Katin, I.V., Kretova, M.A., and Avilov, E.S., Thermoelectric properties and magnetic capacity of thermocouples based on “natural” nanostructures–layered crystals of the family [(Ge, Sn, Pb)(Te, Se)]m [(Bi, Sb)2(Te,Se)3]n (m, n = 0, 1, 2…), Materialy XV Mezhgosudarstvennoi konferentsii “Termoelektriki i ikh primeneniya–2016” (Proc. XV Int. Conf. “Thermoelectrics and Their Applications–2016”), St. Petersburg: Peterb. Inst. Yad. Fiz., 2016, pp. 146–151.

Fiziko-khimicheskie svoistva poluprovodnikovykh veshchestv. Spravochnik (Physical and Chemical Properties of Semiconductor Substances: Handbook), Novoselova, A.V., Ed., Moscow: Nauka, 1979.

Fizicheskye velichiny. Spravochnik (Physical Values: Handbook), Grigor’ev, I.S. and Manuilov, U.Z., Eds., Moscow: Energoatomizdat, 1991.

Kotirlo, G.K. and Lobunets, Yu.N. Raschet i konstruirovanie termoelektricheskich generatorov i teplovykh nasosov. Spravochnik (Calculation and design of thermoelectric generators and heat pumps: Handbook), Kiev: Naukova Dumka, 1980.

Korzhuev, M.A., Use the Lents rule for rapid calculations of thermal and electric chains of thermoelectric modules, Materialy XV Mezhgosudarstvennoi konferentsii “Termoelektriki i ikh primeneniya–2016” (Proc. XV Int. Conf. “Thermoelectrics and Their Applications–2016”), St. Petersburg: Peterb. Inst. Yad. Fiz., 2017, pp. 226–231.

Volkov, B.A. and Pankratov, O.A., Two-dimensional massless electrons in an inverted contact, Pis’ma Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz., 1985, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 145–148.

Eremeev, S.V., Koroteev, Yu.M., and Chulkov, E.V., Effect of the atomic composition of the surface on the electron surface states in topological insulators \({\text{A}}_{{\text{2}}}^{{\text{V}}}{\text{B}}_{{\text{3}}}^{{{\text{VI}}}}\), JETP Lett., 2010, vol. 91, no. 8, pp. 387–391.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our gratitude to P.P. Konstantinov (Ioffe PTI, St. Petersburg) for assistance in measuring the thermoelectric properties of alloys.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Translated by K. Gumerov

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Korzhuev, M.A., Avilov, E.S. & Kretova, M.A. Magnetic Field Production Abilities of Thermoelectric Materials Based on Layered Crystals of the Family [(Ge, Sn, Pb) Te]m [(Bi, Sb)2 (Te, Se)3]n (m, n = 0, 1, 2, …) with Non-Isovalent Cationic Substitution. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 10, 1039–1051 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1134/S2075113319050137

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1134/S2075113319050137