Abstract

Between 2000 and 2007, 255 individuals comprising 59 groups were prosecuted in US federal courts for providing material support to known terrorist organizations, a violation of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996. In collaboration with the American Terrorism Study, data were collected from federal court records on the prosecution of these individuals. Patterns in the data were observed and these offenders were categorized into four groups. Logistic regression models were used to compare these offenders with conventional, violent terrorists. Results show significant differences (in regards to both demographic and legal variables) between those offenders providing material support and those carrying out violent actions. Implications of the data and results are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A wealth of professional and academic research has been dedicated to terrorism since 11 September 2001 (9/11). The vast majority of government reports, empirical research and media attention that pertains to terrorism focuses on the violent offender that is acting on behalf of an ideological motive. However, what truly separates terrorism from the vast world of everyday crime is the concept that there is a larger, structured enemy supporting these few trigger-men. Thus, to fully understand terrorism it is necessary to understand these supporting personnel. In criminal law these concepts would be better described with titles such as accomplices and conspiracies. While the scale of such a threat may be exacerbated when observing terrorism, these concepts are not unique to terrorism. Prior research has addressed accomplices and conspiracy; prior research has also addressed terrorism. However, no source of empirical data exists that addresses the overlap between these two phenomena. The current study seeks to fill this void.

In April 1995, Timothy McVeigh detonated a bomb destroying the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. This act of terrorism resulted in 168 deaths and 680 more victims that were wounded. As a relatively quick response to this attack the United States Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (ATEDP) exactly one year later. In addition to other reforms, this law specifically defined and prohibited fundraising for and the giving of assistance to international terrorist organizations. This law also, for the first time, defined the term ‘Foreign Terrorist Organization.’ Since the enactment of this law in 1996 statutes have existed that prohibit providing material support to designated terrorist groups. However, with one exception, the provisions of this law were never used to prosecute criminals until after the events of 9/11.

The codifying of this new criminal offense has created a compromise. Under the ATEDP Act, terrorist accomplices no longer have to be tied to a specific violent incident, only to a known terrorist organization. The current study will clearly show that without this connection to violent behavior punishment is not as harsh as it otherwise could be. Under the Model Penal Code, after which many states model their own criminal codes, accomplices before and during the act can be charged with the same offense as the primary offender. The American justice system has clearly established that the efficiency of enforcement takes precedence over just punishment. Packer (1968) described the justice system as a balance between due process and crime control with efficiency being the ultimate means of crime control. He would probably be greatly pleased with these changes in law. However, many would argue that punishment and deterrence could just as effectively serve the purpose of crime control. This would be better served by connecting material supporters to the violent actions they facilitate and allowing the possibility of harsher and more fitting punishment.

The enforcement of these statutes requires an understanding of these offenders. Understanding who these offenders are, what they do, what motivates them, and how they differ from conventional violent terrorists has many benefits. It can aid investigators and court personnel in the field and also help to drive future theory and inquiries in the study of terror and security. Because of the short lifespan of this act, opportunity has not existed for previous research to be conducted on the implementation of this law and its impact. Because of this fact, the current study is exploratory in nature.

Literature Review

As mentioned, prior research has addressed the concepts of accomplices and conspiracy. Prior research has also delved into many facets of terrorism. However, the current study cannot build upon an existing body of knowledge on the joint study of these two topics. This is simply because empirical studies have not focused on the very real presence of accomplices within terrorist groups. This study seeks to build upon what has been observed through studying each of these areas separately.

First consider the study of accomplices and conspiracy. These phenomena distinguish the social side of criminal behavior. Criminology has provided a wealth of theoretical studies that focus on the social relationships between offenders (Burgess and Akers, 1966; Hindelang, 1971; Akers, 1985; Akers, 1998; Tremblay and Morselli, 2000; Morselli and Tremblay, 2004). However, terrorist organizations take this social relationship one step further. They rely on heavily organized, formal structure. Their structure is much more similar to organized crime than a group of delinquent peers. White (2006)states, ‘Terrorism is also linked to organized crime throughout the world, and in some cases it is almost impossible to distinguish between terrorist and criminal activity’ (p. 71).

The study of organized crime has phased in and out of the spotlight in criminology. With the unit of analysis frequently being the organization, as opposed to the individual, these works are frequently case studies. These studies offer invaluable qualitative evidence. These studies have looked at aggregate level predictors of organized crime (Sung, 2004). They have also distinguished a fine line between three types of criminal organizations: illegal markets (Natarajan, 2006), cartels illegally involving themselves in legal businesses (Faulkner et al, 2003), and hybrid organizations (White, 2006).

The body of knowledge on terrorism has served a myriad of unrelated purposes. One area of research that has been a point of emphasis concerns the prosecution and sentencing of terrorists in US federal courts. This research is largely spearheaded by Smith and Damphousse (Smith and Damphousse, 1996; Smith et al, 2002; Smith et al, 2005; Damphousse and Shields, 2007), who have created the American Terrorism Study (ATS) through the collection of select federally tried court cases identified by the FBI.

Much effort has gone into the study of the deterrence of terrorists (Dugan et al, 2005; O’Malley, 2006; Stern and Modi, 2008; Lafree et al, 2009). Many have analyzed responses to terrorism. These include a wide variety of studies, including responses from both states (Croissant and Barlow, 2007; Lombardi and Sanchez, 2007; Napoleoni, 2007; Perl, 2007; Piombo, 2007; Biersteker et al, 2008; Eckert, 2008) and society (Powell and Self, 2004; Goodwin et al, 2005; Yum and Schenck-Hamlin, 2005; Ai et al, 2006; Sheridan, 2006). Research has evaluated such topics as the geographic structure of terrorist cells (Rossmo and Harries, 2009) and the psychology of terrorist members (Hamm, 2004; Moghaddam, 2005). Efforts at making an exhaustive list of terror related research would be folly. This is due, in large part, to the collective lack of focus in this discipline. While the current study will not address the need for focus it will address a gaping hole that is not even contemplated in the existing body of knowledge, the terrorist accomplice.

Where the current study differs from previous research is in the fact that the focus is no longer on the trigger man. Instead the focus has shifted to the accomplices, or those that provide material support. Therefore, this exploratory study should begin with the simple question ‘who are these offenders?’ However, the current research does not end so abruptly. The current research seeks to answer two questions. They are detailed as follows:

Research Question 1:

-

Who are these offenders that provide material support to terrorists? Descriptive statistics will be used to initially identify and describe these previously unobserved offenders. Additionally, these offenders will be compared to a sample of conventional violent terrorists using logistic regression models.

Research Question 2:

-

What are the typologies of material support offenders? Trends in the collected data are identified that can categorize and specify the various types of deviance committed by material support offenders.

It is important for any initial observation to report simple descriptors such as demographics and legal variables. However, it is also the intent of this researcher to compare these offenders with traditional terrorists, and to categorize the offenses of these accomplices to allow for a better understanding of their deviance. Such typologies will show not only the nature of the act they commit, but will also display the relationship between these various accomplices.

Research Methodology

The current dataset on terrorist accomplices consists of 59 indictments, containing 255 individuals. This complete list of offenders investigated and charged under the ATEDP Act was provided to the ATS by the FBI. All listed cases were tried in federal courts; therefore, no state criminal cases were included. While data on conventional terrorists have been added to the ATS on a regular basis this list of individuals who provided material support has been ignored. The existing data in the ATS was used to create the baseline control group of conventional, violent terrorists. These additional cases were used to create a new sample of material support cases. As mentioned, this legislation was not routinely enforced until after 9/11. Therefore, with one exception, all offenders were indicted between 2001 and 2007, as opposed to the data on conventional terrorists which were indicted between 1980 and 2002.

After the initial list of offenders was obtained, court records were then reviewed on each case by way of the PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records) system, an online source for official federal court records. The data were collected from various court documents including the following: the court docket, indictments, trial minutes, arrest warrants, financial affidavits, judgments, sentencing memorandums, plea agreements, and various other motions.

Data were collected on each count against each individual. This method of coding the data allows greater flexibility. This allows analysis at the count, person, indictment, and group level. This method was also useful in providing descriptors for the current research question. Data were coded and analyzed using Stata statistical analysis software.

Results

Research question 1: Who are these offenders?

Because of its exploratory nature, the analysis of these material support cases will begin with simple descriptive statistics. Identifying the individuals being charged with, and convicted of an offense, sheds light not just on the offender and the offense, but also on the government’s enforcement of the statutes. The most obvious place to begin is with demographics. The majority of these offenders are Arab males, over the age of 35, who tend to be married and live with a spouse and/or children. This is much older than what is thought by theorists, such as Sampson and Laub (1993), to be the prime offending age. With Arabs making up 80 per cent of individuals charged with providing material support to terrorists, this may explain more about the enforcement of the law than the actual individual offenders. Before 9/11 this country was concerned with both domestic and international terrorists. After 9/11 international terrorism was the sole focus.

Even more surprising may be their level of education. The majority have some formal college experience. Many have completed a college degree. Thirteen per cent have completed a master’s degree, and 16 per cent have completed a doctorate, jurist doctorate, or medical degree. These numbers are not only higher than conventional criminal offenders; they are even higher than the typical non-offending population. A complete breakdown of all of these demographic categories is found in Table 1.

As previously mentioned, the sample consists of 255 individuals tried in 59 cases. Of these 59 cases, the majority were tried in one of four states: Michigan, New York, Texas, or Florida. For a breakdown of the number of cases by state see Table 2. No other state had more than four cases.

It should be understood that the existing dataset was not compiled to simply evaluate demographics. Many legal factors were observed and are presented in Table 3, beginning with pre-trial factors. Similar variables are also presented in Table 4.Footnote 1 These defendants typically relied on public defenders for representation (however, it should be noted that 28 per cent had exclusively private representation), received bail with an average amount of 238 000 dollars, endured very lengthy trials, had nearly a dozen co-defendants, and faced nine counts.

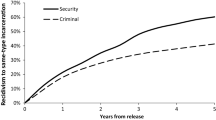

The most frequent result for these cases was for the individual to plead guilty to one or more charges (56 per cent). In total, 85 per cent of those individuals that appeared before the court where convicted of at least one charge. Upon sentencing, the court more often than not issued a sentence in line with both the pre-sentence investigation and the recommended range provided by the federal sentencing guidelines. The rare case of a downward departure was because of the fact that the individual provided substantial assistance to the prosecution. Common punishments consisted of incarceration, fines, restitution, forfeiture, and probation. Of those convicted, 86 per cent saw some time of incarceration. Of all those incarcerated the mean sentence length was nearly 125 months; a figure much smaller than the sentence of conventional violent terrorists. The percentage distributions of pre-trial and sentencing variables are displayed in Tables 3 and 4. The mean values of appropriately represented legal variables are found in Table 5.

Data examined also related to the nature of the offense. Various forms of support were provided. In each of the 59 cases a dollar value was given for the support provided. This was self-explanatory when support was monetary. In other cases the investigating law enforcement personnel estimated values of illegal goods, such as weapons or drugs, and reported these values to the district attorney. They were then presented in the indictments, financial affidavits, and sentencing memorandums. The average value of support provided was over 3.8 million dollars.Footnote 2 Take, for example, one arms dealer who attempted to sell weapons to the FARC. He was apprehended by an undercover FBI agent while attempting to sell 3.9 million dollars’ worth of small firearms, grenades, and various other explosives. The data from this case shows the nature of the offense, the type of support provided (material goods), and the value of the support. In these cases, the methods of raising funds were coded as either legitimate, illegitimate, or a combination of both. In cases like this example, where illegal transactions constitute the support, fund raising is coded as illegal. A breakdown of the nature of the sources of funding (legal, illegal, or both) is shown in Table 4.

Comparing material support cases to conventional terrorists

The univariate statistics paint a picture of the individual charged with providing material support to terrorists. However, in order to fully understand these offenders they must be compared with a reference category. For this purpose, the data on material support cases was merged with a sample of 510 conventional terrorists taken from the existing ATS dataset. This resulted in a merged sample of 765 individuals that either committed violent acts of terror or provided material support.

A simple t-test could evaluate the significance of the relationship between group identification and any other single variable. However, a logistic regression model, with a dichotomous outcome indicating material support cases, will do the same thing. In addition it will yield a measurable magnitude, and simultaneously control for age, gender, and race. This allows the researcher to observe if the difference between conventional terrorists and material support cases is significant even when age, gender, and race are held constant. This test was conducted for 15 variables. It should be noted that the inclusion of all variables in a single logistic regression model was impossible, because of missing observations in the original ATS cases. Attempting this resulted in no variation in the dependent variable. It should also be noted that criminal history and a binary variable, indicating domestic or international terrorism, would also have been included except that these variables lacked the needed amount of variance. The results are presented in Table 6 as odds ratios.Footnote 3

Of the 15 regression models run, in half of the cases the variable being observed is no longer significant once the model controls for age, gender, and ethnicity. The variables that do achieve significance are ethnicity, education, whether or not the individual is convicted, whether or not the individual pleads guilty, the type of sentence received (incarceration), the number of co-defendants, case length, and offense severity. In several of the models, but not all, age is also significantly different between accomplices and violent terrorists. In each of those six instances, it is obvious that accomplices are more likely to be over the age of 35 than are conventional terrorists. These models show that accomplices are as much as 98 per cent less likely than conventional terrorists to be white. This is not surprising considering the ethnic makeup of both groups presented in Table 1.

With age, gender, and race held constant the following are all true. The odds of an accomplice having a college degree are 136 per cent greater than a conventional terrorist. This corroborates the percentages in Table 1 and shows that accomplices are far more educated than conventional terrorists. The odds of an accomplice being convicted are 80 per cent less than that of a conventional terrorist. This relationship is significant despite the fact that the conviction rate of the two groups only differs by eight per cent. The odds of an accomplice accepting a plea bargain are twice as likely as a conventional terrorist. And, the odds of an accomplice facing incarceration are 84 per cent less likely than the odds of a conventional terrorist. So, accomplices are less likely to be convicted and less likely to face incarceration when convicted.

Additionally, the coefficients in these models indicate a significant difference in the number of defendants, the length of cases, and the severity of the offense. In order to optimize normality each of these variables was transformed, which skews the magnitude of these effects. However, a statistically significant difference is still known. Refer to Table 5. Material support offenders have significantly larger groups of co-defendants. Their cases take significantly longer to try and their offense severity is significantly greater.

With this fundamental knowledge of material support offenders and a quantitative comparison with traditional terrorists, the logical conclusion of many may be to create a profile that could assist law enforcement in detecting these crimes and apprehending these offenders. This is not advisable. With the following research question the author seeks to create typologies to further theory and understanding, not for the purpose of creating profiles. Not only does the use of rigid profiles bring with it controversial questions about practice, it also makes avoiding detection simple for the offender. There is no easier way to avoid detection then to know the exact picture law enforcement is looking for.

Research question 2: What are the typologies of material support offenders?

If these offenders are providing material support to terrorists it begs the question, ‘Exactly how are these individuals furthering terrorist goals?’ The previous question focused on who these individuals are. This current question focuses on what these individuals have done. The nature of the support provided to terrorist organizations is a basis upon which this sample of offenders can be segregated into four typologies. These typologies are categorized by the type of physical support they provide a terrorist group, not necessarily the law broken or crime with which the individual is charged.

Individuals were placed into one of four categories based upon observations gathered from reading these various court documents. While reading through dozens of these cases, specific patterns began to emerge. Individuals and groups were found to (i) provide monetary support, (ii) offer their personal services, or (iii) provide material items such as weapons or supplies. There are also a few rare cases in which a group or individual provided a combination of these types of support. The nature of these crimes varies greatly, as does the overt appearance of criminality.

Group #1: Financers

The first category of terrorist accomplices is comprised of those that provide exclusively financial support. This is the most frequently occurring typology, as 109 of the 255 offenders are financers (43 per cent). These offenders often send finances discretely to their one contact within a terrorist organization. They either send funds internationally to a large group or to a small, domestic cell that is under the umbrella of an international organization. The most frequent form of monetary transfers was the use of wire transfer businesses (62 per cent). However, these individuals also made use of checks and couriers, who physically delivered funds.

Financers were usually observed to be in large, yet unorganized, groups that were often connected by family. Large is a term relative to the other typologies. The mean group size for the entire sample is 10.85, while the mean group size for financers is 14.13. Table 7 shows several such differences between these typologies. Those providing finances operated within large groups. However, these individuals comprise their own local cells; they do not associate with a large number of known terrorists. Very few had any contact with individuals designated as terrorists by the US State Department. This supports Shapiro’s proposition (2007) that the individual’s choice to specialize in the financing of terror is a rational choice, one that is intended to minimize risk yet allow the individual to support their ideological cause. This is important, because if terrorism is a product of rational choice it can theoretically be deterred.

The criminal behavior undertaken by financers is often more deviant on its face then the actions committed by the other typologies. This is because finances are usually acquired illegally. On the contrary, the following explanation of voluntary personnel and those that provide material support shows that these individuals are committing acts that, without terroristic intent, often lack criminality. Illegal methods of raising funds observed in this data set include interstate smuggling, theft rings, selling counterfeit goods, arms trade, money laundering, credit card fraud, tax fraud, unlicensed wire transfer businesses, and drug sales. All of these acts are illegal regardless of the ultimate destination of the funds. Sixty-seven per cent of financers relied on one of these illegitimate means to raise funds. Twenty-three per cent used funds from legitimate businesses or their own finances. Ten per cent used a combination of both illegitimate and legitimately acquired funds.

Illegal schemes for raising funds were found more often than legal ones. Take, for example, the owner of an Arizona based export company. He operated a baby formula theft ring out of Tempe, Arizona, that stole and resold seven million dollars’ worth of formula. He had 26 co-defendants working under him, at least four of whom were direct relatives. This case exemplifies the large, and often familial, group size of financers. Like most financers, this Arab-American businessman did not have direct contact with a known terrorist. In fact, prosecutors were not able to convince the jury of a link to terrorists. Instead, the defendant was convicted on 20 various counts of conspiracy, theft, money laundering, and fraudulent nationality documents, not terrorism related charges. This business owner was ultimately convicted by a jury and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

While illegal examples such as this are the norm, they in no way comprise all cases of financing terrorists. Legal sources of income, such as business profits, charitable gifts, and even federal grants, were found to be used in financing terror. A very high profile case in North Texas involved a charity, the Holy Land Foundation. The entire foundation was charged as one defendant along with seven other co-defendants, only one of which was not employed by the Holy Land Foundation. This organization used charitable donations to support Hamas efforts in the Gaza Strip. The amount of funds provided to Hamas leaders was estimated to be over 12 million dollars. The foundation was ordered to forfeit all assets. Of the seven co-defendants one is still a fugitive today. The others were punished with incarceration, forfeiture, and/or deportation. Sentences ranged from 6 to 240 months.

The overt deviance of the act varies greatly, but is very important when the individual is on trial. Financers often commit illegal acts just to acquire the funds they will use for further criminal purposes.

Group #2: Voluntary personnel

Forty-four of the 255 offenders (17 per cent) are voluntary personnel who offered their personal services, not money or physical assets, to a terrorist organization or cell. Very often, these are individuals who train and prepare for physical attacks, but being apprehended before executing any plans, these individuals remain only accomplices. The actions by voluntary personnel include recruiting other potential members, attending and/or organizing training camps, relaying messages, and gathering intelligence.

Voluntary personnel’s knowledge of and involvement in group plans varies greatly. Many are new recruits aiding small cells. Others have established contact with some of the highest ranking leaders of international organizations, such as Al Qaeda and the Taliban. Because of the number of these individuals that travel to attend training camps, they are far more likely than other offenders to operate in small groups of one, two, or three. As opposed to financers, these individuals are in very small, yet highly organized groups. As mentioned, the mean group size of the entire sample is 10.85, yet the mean group size for voluntary personnel is only 6.14.

Thirty-eight of the 44 individuals (86 per cent) categorized as voluntary personnel attempted to join and/or train with a terrorist organization. Jeff Bonner was one of seven individuals that attempted to join Al Qaeda shortly after the events of 9/11. While one of the individuals provided finances to the organization in order to create a training camp in Oregon, the other six members of the group planned to attend this camp and eventually join Al Qaeda. Local and national news labeled this group the Portland Seven. Bonner, one of the two American born members of this group, attended this camp and engaged in small firearms training. Mr Bonner pled guilty to one count of ‘conspiracy to levy war against the United States’ and one count of ‘refusing to testify before a grand jury.’ The actions of traveling to a terrorist camp and training in specific skills are precisely the support that most voluntary personnel provide. These actions subjected Mr Bonner to 18 years in federal prison, a fine, and forfeiture of all assets involved in the training camp. Yet consider the criminality of these acts. No crimes would have been committed if Mr Bonner’s actions were free of terroristic motive.

A less common action categorized as voluntary personnel are those individuals that relay messages and gather intelligence. Two Arab males in New York City were accused of relaying messages to and from Omar Ahmad Ali Abdel Rahman. This internationally wanted terrorist goes by the alias ‘the Sheikh,’ and is the head of the radical Islamic group that simply calls itself ‘The Islamic Group.’ The case of these two New Yorkers exemplifies how small these groups of voluntary personnel can be, and how they can become involved with high ranking terrorist leaders. This case quickly made national news when, while incarcerated, their attorney (a white American female) and translator aided them in sending additional information to ‘the Sheikh.’ The group of two offenders then grew to four. Of these four, one is a fugitive and the other three were convicted of conspiracy, making false statements, and solicitation. Sentences ranged from 20 to 288 months. Consider the actions of the defendants. They made phone calls, sent faxes, and wrote emails. Regardless of the content of such messages, these actions would never be considered criminal, or be monitored, had it not been for the recipient of the messages. The transferring of information was criminal only because it was intended to aid ‘the Sheikh’ and ‘The Islamic Group.’

Unlike financers, voluntary personnel rarely commit acts that are illegal in and of themselves. Many of the physical actions taken by these individuals were merely traveling, relaying information, and communicating with other specific individuals. While financers were often observed committing acts that were criminal at face value, voluntary personnel were often observed committing acts that, separated from terroristic motives, would not be considered criminal.

Group #3: Material providers

Those individuals that supply physical assets, rather than services, are categorized as material supporters. In many ways these offenders should be considered the intermediate of these three typologies. Material supporters are more common than voluntary personnel, but are not as prevalent as financers. They comprise 35 per cent of the entire dataset. The average group size for these individuals is 10.47, smaller than the same value for financers and larger than voluntary personnel. This number is very close to the mean of the entire sample. This indicates that they function in both large and small groups.

Much like voluntary personnel, the group involvement of material supporters varies greatly. Some provide a small number of supplies to local cells. Others provide long-term, steady support to international terror organizations over a period of years. An example of the latter was the case of Infocom Corporation, a telecommunications company that operated out of Richardson, Texas. While much of the media coverage surrounding this case portrayed the offenders as financers, they were actually the primary supplier of computer and networking hardware for Hamas in Libya and Syria. They primarily used trade diversion to provide these goods overseas. Like most other material supporters, they operated in what would be considered a medium size group of eight conspirators. Six were brothers, one was a family friend, and the last defendant was Infocom Corporation. All six members of this group that appeared in court were convicted by a jury and the sentences were as long as 84 months.

The types of materials provided are diverse in nature. Observed in these cases were individuals providing weapons, night vision goggles, clothing and uniforms, vehicles, computer and networking hardware, housing, false documents, medical services, training equipment, and oil manufacturing equipment. There is even great variance in the weapons supplied. They include small firearms, grenades, rocket propelled grenades, anti-aircraft missiles, other explosives, and even attempts to acquire chemical weapons and weapons of mass destruction. Additionally, the quantities vary, from instances as minor as individual members making use of their personal sidearm all the way up to arms dealers providing thousands of firearms.

Sending materials to another person may or may not be illegal. In several of these cases individuals were shipping materials, posed as trade goods, to countries, individuals, and/or organizations with whom the federal government has criminalized trade. These cases are clearly criminal regardless of motive. Another example of overt criminal acts by these offenders is where false documents were provided. However, the actions of material providers, separated from motive, are not always overt crimes. In cases where the individual is indicted for providing training equipment it is often merely camping supplies that are being shipped from one individual to another. In addition, those individuals who provide transportation or housing are providing services that are in no way criminal without the attachment to terroristic motives.

The diversity of these cases can be seen by comparing the previously mentioned executives of Infocom with the case of Youssef Mohamad, a 26 year old waiter from North Carolina. Mr Mohamad organized and operated a cigarette smuggling ring with 24 other co-defendants. He transported thousands of dollars’ worth of cigarettes to Michigan, where he could resell them and keep the profit disguised as a higher state tobacco tax. The cigarettes, however, were a means to acquire cash. The cash was actually used to purchase various firearms and explosives for Hizballah cells. This case was rare among the material support category because it involved such a large group. Of the 25 defendants, 18 were convicted, two were acquitted, and five are fugitives. As the leader of the operation, Mohamad received the harshest penalty. He was sentenced to 155 years.

Now compare these two cases. The executives of Infocom were committing an act that, without political motive, would have no criminal nature. Shipping computer hardware overseas is perfectly legal. Aiding terrorists changes the nature of this act. However, regardless of political motive the actions of Mr Mohamad and his co-conspirators were illegal. He illegally transported cigarettes, illegally sold cigarettes, and used the money to illegally purchase weapons. In addition, those weapons went to support a terrorist organization. These actions would warrant the attention of law enforcement regardless of political motive.

The actions of financers were observed most frequently to be criminal in nature. The actions of voluntary personnel were observed most frequently to not be criminal in nature. These two examples show that material providers are the intermediate typology. Their actions are evenly distributed between illegal and legal behavior once separated from terroristic motives.

Group #4: Combinations

While the overwhelming majority (95 per cent) of these cases can cleanly fit into one of these three main typologies, 12 individuals (five per cent) observed in this dataset provided some combination of finances, physical assets, and services. Eleven individuals provided a combination of finances, weapons, and personally recruited other members (or did all three). The final individual provided a combination of services and material assets.

Kamel Zayed was a Muslim imam practicing in New York who was found supplying Al Qaeda with various resources. He and an accomplice were charged with six counts of providing material support to terrorists. Zayed used his position as a religious leader to find sympathetic recruits. In addition, he provided Al Qaeda with more than 24 million dollars’ worth of cash and firearms. For his part, Zayed was sent to prison for 15 years and was ordered to pay a 1.3 million dollar fine.

These individuals may not be of great statistical significance because of their rarity; however, it is significant to point out that these three main typologies are not mutually exclusive. The current data is analyzed on the individual level. It is an important reality that these typologies can co-exist at the individual level, but it is perhaps more important that these typologies can, and often do, co-exist and complement one another at the group level. Groups could very well have individuals that specialize in providing each of these various resources. The consequences of this line of inquiry are beyond the scope of the current study.

Discussion

The results from the current study can be used to show support for existing theoretical explanations, to inform law enforcement on strategies not to pursue, and to make three recommendations to improve the efforts of law enforcement and courts in countering terrorist supporters.

Support of theoretical explanations

Is terrorism, as assumed in studies of deterrence, a product of rational choice? According to the classical school of criminology, offenders are rational actors who consider the outcomes of their actions, and choose the course that provides the most pleasure and the least pain. Many (Dugan et al, 2005; Lafree et al, 2009) have worked under the theoretical assumption that this is true of terrorists as well. Shapiro (2007) went so far as to explain that this assumption is supported by the presence of individuals providing monetary support to terrorists. In doing so, these actors are able to increase pleasure by knowing that they have contributed to an ideological and/or violent cause. At the same time they are able to avoid pain by minimizing the odds of detection, because a traditional, street-level crime is not being committed and little evidence exists.

The typologies observed in the current data provide further evidence of Shapiro’s claim. Several measures unique to financers display a conscious control of risk. Those that provide monetary support rarely meet wanted terrorists face to face. In cases that this does happen, the financer would have a single contact. Transfers of finances were most typically made through wire transfers; most did not exchange physical finances, thus limiting direct contact. A third of these financers even used their own legally acquired funds. Those that did use illicit methods chose methods that are very hard to detect with great potential for reward, such as smuggling, fraud, money laundering, and illegal trade. All of these facts taken from the current data depict an individual who is consciously trying to minimize risk, a rational actor. This not only supports Shapiro’s claim, but at the same time lends validity to deterrence theory and the classical school of criminology. Theoretical explanations that correctly measure the nature of these offenders might also be useful in attempting to control their behavior.

What not to do

The current study should also be used to encourage some changes but discourage others. As previously suggested, the typologies observed in this data could be used to create profiles of those providing material support to terrorists. However, this is not advisable. These typologies are better suited for guiding theory, future research, and understanding. The use of rigid profiles by law enforcement could actually do more good for the criminal seeking to avoid detection than for the investigating agency. The simplest way for an organized criminal group to avoid detection is to recruit and deploy offenders that law enforcement would never suspect. This is made a simple task for any criminal group when a known racial or demographic profile of any kind is being used.

Recommendations for enforcement and courts

All of this newly acquired knowledge should be applied to the law enforcement and legal strategies used against terrorist accomplices. These offenders should not be treated like conventional terrorists when conducting research or crafting policy. The current findings show that they are a different set of individuals and commit a very different set of crimes. They merely share political motivation for their crimes and group affiliation. The justice system should not expect the same strategies to be effective in apprehending and deterring these offenders that are effective against conventional, violent terrorists. Because material support and conventional terrorists are so different in nature, new strategies must be used, and old strategies must be adapted in order to investigate the ever changing actions of terrorists. For these reasons three changes are recommended.

Taking a qualitative approach to this data, it is easy to see the high percentage of material support cases that involve unregistered wire-transfer businesses. The first recommendation is for law enforcement to focus on policing these businesses and encourage cooperation from the private sector, just as they do in the formal banking system. However, in doing so officials must also consider the burden that this places on a predominantly legitimate business. Remittances sent out of the United States amounted to more than 41 billion dollars in the year 2005 alone (Mairson, 2007). Policing this would be no small task.

Another obvious application, which has been made numerous times, including in the 9/11 Commission Report, is the need for greater communication between law enforcement agencies. Federal agencies may lack the in-depth knowledge of criminal environments that local authorities use. At the same time, local agencies often lack the funding and resources of federal agencies. These are obvious considerations that have been addressed in the past. Where the current study can be uniquely applied to practice is in the legal strategies used against these offenders.

Another relevant question raised by this research regards the culpability of an accomplice in the commission of a crime. Under the Model Penal Code, an accomplice before or during the act can be charged with the same offense as the primary offender. And, in nearly every case in this dataset, the terrorist cell or individual was apprehended before any attacks. These individuals are accomplices before the act. With that said, these individuals were not tried as accomplices. The creation of laws such as the ATEDP Act has loosened the rules of prosecution. These accomplices are no longer tried as accomplices, but as primary offenders. While this may seem like a ‘tough-on-crime’ stance that is concerned with efficiency, it actually results in more lenient punishment. The offender no longer has to be tied to a specific violent attack carried out by a specific cell. These accomplices only have to be linked in some way to a larger, known terrorist organization. Because they are not linked to a specific violent act, these accomplices are charged with lesser offenses that are not of a violent nature. In essence, the justice system is attempting to prevent more severe attacks by punishing terrorists before they conceive large-scale plans. This provides a tradeoff. Legislatures have created with this law a system that prioritizes efficiency over just and fair punishment. The criminal justice system is able to effectively and efficiently process these cases (as mentioned, 85 per cent of these cases resulted in a conviction). However, these individuals are not punished as severely as they would be if tied to a specific, violent act. Looking at the discrepancy between sentence lengths given to violent terrorists and material supporters suggests this.Footnote 4 Conventional, violent terrorists receive sentences that are, on average, 52 months longer than these support cases. This discrepancy would not be present if these individuals were tried as accomplices to specific violent conspiracies.

For these reasons, the final recommendation is for prosecutors, when possible, to seek criminal charges other than violations of the ATEDP Act. The ATEDP Act does serve the purpose of efficiency, but legislatures and prosecutors must decide if crime control is best served with efficiency or more severe punishment. These parties are obviously expressing that the efficiency of the system takes priority over the culpability of an individual accomplice. If accomplices were attached to the violent attacks that they plan and support these individuals could be prosecuted with more severe charges. The punishment would be more likely to fit the crime; however, this would reduce the efficiency of current methods. This trade off must be considered by legislatures and judiciaries.

If variation in the prosecution of terrorist accomplices can increase punishment, than this could serve as a deterrent. It was previously shown that these offenders conform to the ideas of deterrence theory. Incapacitating offenders with harsher sentences and deterring future offenders would ultimately increase the security of this country.

Future research

This dataset in its current form can be used in future efforts to address emerging questions that arise regarding the accomplices of terrorists. A follow-up study is already under way to address the difference in punishment between financers, voluntary personnel, and material supporters. The likelihood of conviction and sentence length will be used as proxies for punishment. Future statistical models could address the likelihood of many other proxies for this same concept, such as the likelihood of receiving bond, the amount of bond, or departures from sentencing guidelines. Other studies could focus on the question of what factors influence various forms of punishment. All of these are possible with the collected data.

If the dataset were expanded over time, as additional cases are tried in federal courts, it may become possible to incorporate more control in statistical models by using nested models. This could help control for the influence of various geographic regions and differing Circuit Courts.

Additional analysis is also needed to firmly ground an understanding of these accomplices. In describing these individuals, they were compared with conventional, violent terrorists. However, it is also necessary that these offenders be compared with conventional street-offenders. This could provide a base line for comparison. These offenders could also be compared with what may be a more similar sample, such as white-collar offenders.

This research has created a dataset that can be used in future inquiry, and a sample that can be compared with other offenders. However, the current study also raises issues that can only be addressed with separate original research. Take the issue of prosecutorial discretion for example. The true variation in these cases may not lie in the hands of judges and juries who sentence terrorist accomplices. Instead, there is reason to believe that discretion lies with the federal prosecutor. Eighty-five per cent of cases that are indicted result in a conviction on one or more charges. This indicates that prosecutors only take these cases to trial when a large amount of evidence exists. This could possibly be a threat to internal validity. Qualitative research would be best suited to survey federal prosecutors, to address more specifically why some offenders are not indicted.

The findings in this study can reaffirm and direct legal practices used today. To the extent possible, the current study has attempted to address the phenomenon of terrorist accomplices. This is merely a starting point. It is a study that raises far more questions than it can answer. However, the creation of the current dataset allows for these questions to be addressed in future inquiries.

Notes

This value was analyzed at the group level not the individual level. Each value represents the combined support of the entire group. Values ranged from 0 to 25 million dollars. The mean is 3.8 million. The variance is 5.10e+13, and the standard deviation is 7.14e+6.

Before observing these logistic regression models diagnostics were used to ensure the data did meet model assumptions. In each model multivariate outliers were removed as needed. No model required removing more than three. In each model the mean variance-inflation factor (VIF) indicated that multicolinearity was not problematic. The highest mean VIF was merely 1.06. Five of the variables proved to not be normally distributed and required transformations in order to optimize normality. The dollar value of bail and the measure of offense severity were both square-root transformed. Sentence length in months, the total number of counts, and the number of co-defendants were all log transformed. The logistic regression models were run following these diagnostic tests.

See Table 5.

References

Ai, A., Santangelo, L. and Cascio, T. (2006) The traumatic impact of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the potential protection of optimism. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 21(5): 689–700.

Akers, R. (1985) Deviant Behavior: A Social Learning Approach. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Akers, R. (1998) Social Learning and Social Structure: A General Theory of Crime and Deviance. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

Biersteker, T., Eckert, S. and Romaniuk, P. (2008) International initiatives to combat the financing of terrorism. In: T. Biersteker and S. Eckert (eds.) Countering the Financing of Terrorism. New York: Routledge, pp. 234–259.

Burgess, R. and Akers, R. (1966) A differential association-reinforcement theory of criminal behavior. Social Problems 14(2): 128–147.

Croissant, A. and Barlow, D. (2007) Terroist financing and government responses in Southeast Asia. In: J. Giraldo and H. Trinkunas (eds.) Terrorism Financing and State Responses: A Comparative Perspective. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 203–230.

Damphousse, K. and Shields, C. (2007) The morning after: Assessing the effect of major terrorism events on prosecution strategies and outcomes. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 23(2): 174–194.

Dugan, L., Lafree, G. and Picquero, A. (2005) Testing a rational choice model of airline hijackings. Criminology 43(4): 1031–1065.

Eckert, S. (2008) The US regulatory approach to terrorist financing. In: T. Biersteker and S. Eckert (eds.) Countering the Financing of Terrorism. New York: Routledge, pp. 209–233.

Faulkner, R., Cheney, E., Fisher, G. and Baker, W. (2003) Crime by committee: Conspirators and company men in the illegal electrical industry cartel. Criminology 41(2): 511–554.

Goodwin, R., Willson, M. and Gaines, S. (2005) Terror threat perception and its consequences in contemporary Britain. British Journal of Psychology 96(2): 389–406.

Hamm, M. (2004) Apocalyptic violence: The seduction of terrorist subcultures. Theoretical Criminology 8(3): 323–339.

Hindelang, M. (1971) The social versus solitary nature of delinquent involvements. British Journal of Criminology 11(2): 167–175.

Lafree, G., Dugan, L. and Korte, R. (2009) The impact of British counterterrorist strategies on political violence in Northern Ireland: Comparing deterrence and backlash models. Criminology 47(1): 17–45.

Lombardi, J. and Sanchez, D. (2007) Terrorist financing and the tri-border area of South America: The challenge of effective governmental response in a permissive environment. In: J. Giraldo and H. Trinkunas (eds.) Terrorism Financing and State Responses: A Comparative Perspective. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 231–246.

Mairson, A. (2007) Sending money home. National Geographic April: 26.

Moghaddam, F.M. (2005) The staircase to terrorism: A psychological exploration. American Psychologist 60(2): 161–169.

Morselli, C. and Tremblay, P. (2004) Criminal achievement, offender networks and the benefits of low self-control. Criminology 42(3): 773–804.

Napoleoni, L. (2007) Terrorism financing in Europe. In: J. Giraldo and H. Trinkunas (eds.) Terrorism Financing and State Responses: A Comparative Perspective. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 171–184.

Natarajan, M. (2006) Understanding the structure of a large heroin distribution network: A quantitative analysis of qualitative data. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 22(1): 171–192.

O’Malley, P. (2006) Risks, ethics, and airport security. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 48(3): 413–421.

Packer, H.L. (1968) The Limits of the Criminal Sanction. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Perl, R. (2007) Anti-terror strategy, the 9/11 commission report, and terrorism financing: Implications for U.S. policy makers. In: J. Giraldo and H. Trinkunas (eds.) Terrorism Financing and State Responses: A Comparative Perspective. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 247–259.

Piombo, J. (2007) Terrorist financing and government responses in East Africa. In: J. Giraldo and H. Trinkunas (eds.) Terrorism Financing and State Responses: A Comparative Perspective. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 185–202.

Powell, L. and Self, W. (2004) Personalized fear, personalized control, and reactions to the September 11 attacks. North American Journal of Psychology 6(1): 55–70.

Rossmo, D. and Harries, K. (2009) The geospatial structure of terrorist cells. Justice Quarterly 28(2): 221–248.

Sampson, R. and Laub, J. (1993) Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points Through Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press.

Shapiro, J. (2007) Terrorist organizations’ vulnerabilities and inefficiencies: A rational choice perspective. In: J. Giraldo and H. Trinkunas (eds.) Terrorism Financing and State Responses: A Comparative Perspective. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 56–71.

Sheridan, L. (2006) Islamophobia pre- and post-September 11th, 2001. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 21(3): 317–336.

Smith, B. and Damphousse, K. (1996) Punishing political offenders: The effect of political motive on federal sentencing decisions. Criminology 34(3): 289–319.

Smith, B., Damphousse, K., Jackson, F. and Sellers, A. (2002) The prosecution and punishment of international terrorists in federal courts: 1980–1998. Criminology & Public Policy 1(3): 311–338.

Smith, B., Damphousse, K., Yang, S. and Ginther, C. (2005) Prosecuting politically motivated offenders: The impact of the ‘terrorist’ label on criminal case outcomes. International Journal of Contemporary Sociology 42(2): 209–226.

Stern, J. and Modi, A. (2008) Producing terror: Organizational dynamics of survival. In: T. Biersteker and S. Eckert (eds.) Countering the Financing of Terrorism. New York: Routledge, pp. 19–46.

Sung, H. (2004) State failure, economic failure, and predatory organized crime: A comparative analysis. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 41(1): 111–129.

Tremblay, P. and Morselli, C. (2000) Patterns in criminal achievement: Wilson and Abrahamse revisited. Criminology 38(4): 633–659.

White, J.R. (2006) Terrorism and Homeland Security. 5th edn. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

Yum, Y. and Schenck-Hamlin, W. (2005) Reactions to 9/11 as a function of terror management and perspective taking. Journal of Social Psychology 145(3): 265–286.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harms, J. The war on terror and accomplices: An exploratory study of individuals who provide material support to terrorists. Secur J 30, 417–436 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2014.48

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2014.48