Abstract

The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) seeks to provide global financial reporting comparability of its International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). The objective of this study is to propose an organizational dynamic that could improve global comparability of financial reporting under IFRS through rigorous and homogeneous global enforcement. We use the qualitative framework of Gioia et al. (Organ Res Methods 16:15–31, 2012) to identify the relevant literature, methodologies, and organizational dynamics to understand the issues and changes needed to possibly achieve full-IFRS financial reporting for cross-border listed firms. We draw on previous studies that provided evidence of limitations and issues about comparability of financial reporting based on (not homogeneous) adoption, application, and enforcement of IFRS worldwide. A content analysis of IASB’s deliberations in developing its interactions with (International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO)) and national regulatory bodies is used to provide evidence about the initiatives IASB has undertaken to support the homogeneous global enforcement of its standards. Then, we prescribe an organizational dynamics change for IOSCO, to enhance its engagement in promoting rigorous and homogeneous enforcement of IFRS globally. Lastly, we propose that IOSCO review, at least once every three years, cross-border listed firms’ financial reports using a comment letter approach. The results of such a review would be publicly available so that investors and creditors might be able to ascertain whether the financial reports published by cross-border listed firms are comparable with their cross-border listed competitors stating IFRS compliance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Economies, investors, and creditors rely on the free flow of capital and investments across different countries. International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) have become the global language by which investors from across more than 165 countries make judgments regarding cross-border investments. Moreover, some accounting academic studies empirically document lower cost of capital, increased investments in a jurisdiction, increased liquidity, reduced investor forecast errors, and reduced abnormal returns or accrual anomaly for firms after adopting IFRS (de Moura et al. 2020; Kim and Lin 2019; Abad et al. 2018; Wang 2014; Brochet et al. 2013; Horton et al. 2013; Mohammadrezaei et al. 2015; Wang 2014; Yip and Young 2012; Tan et al. 2011).

However, the adoption of IFRS across borders continues to be plagued with incomparable financial reporting between firms listed across differing legal jurisdictions (Phan et al. 2020; Quagli et al. 2020; Mita et al. 2018; Felski 2017; Mohammadrezaei et al. 2013). More recently, even the IASB expressed significant concerns about the incomparability in reported earnings subtotals allowed under IFRS (IASB 2019). Hans Hoogervorst, chairman of the IASB, states (2019)Footnote 1 that little has been done to improve the comparability of financial reporting (CFR) of income statement presentations. He contends that there is evidence that under IFRS companies compute earnings subtotals differently. As a consequence, investors create their own subtotals differently and this limits the comparability of income statement subtotals, like operating income.

Moreover, issues in CFR could emerge within a single country’s financial market. For example, investors on ones’ home country financial market may compare IFRS financial reports (as well as performance indicators) of companies incorporated in different countries but listed in their home countries’ financial markets. Even if these companies’ financial reports are using IFRS, it is probable that comparability is impaired between domestic and cross-border listed companies using different levels of adoption, application, and enforcement of IFRS.

First, each company could draft its IFRS financial report according to the provisions of its home country. Each country may have adopted a different version of IFRS (Felski 2017; Zeff and Nobes 2010). Some could have adopted IFRS as published by the IASB, whereas other countries may have adopted IFRS with a lag or with differing versions of IFRS.

Second, comparable application may be impaired not only when comparing reported earnings, but also when converting from companies’ differing home country language to the host country’s language because of the influence of national culture and country factors in this process (Kleinman et al. 2014). For example, Prather-Kinsey et al. (2018) found that the term “control” is interpreted differently conditional upon management’s work location, and whether from a rules-based vs principle-based accounting standards background.

Third, the enforcement of IFRS is also different between legal jurisdictions (Kleinman et al. 2019; Brown et al. 2014). CFR under IFRS may be impaired when enforcement is high in one country, but not in the other.

The following example might be helpful in understanding the potential complexities that affect comparability of companies’ financial reports relative to adoption, application, and enforcement of IFRS. An international investor is interested in selecting among three investment options in the securities of companies in the telecommunication industry, all cross-listed or listed in the German capital market. We consider two foreign companies, namely, Chunghwa Telecom Ltd. from Taiwan, and Swisscom AG from Switzerland, and one domestic company, namely Deutsche Telekom. They are all similar in size (i.e., market capitalization) and book to market ratio, and use the same set of accounting standards, IFRS, for their consolidated financial statements. The international investor may believe that the financial reports of all three companies are comparable since they all state some form of compliance with IFRS.

However, each company is in a country that has adopted a different version of IFRS: Taiwan (Chunghwa Telecom Ltd.) adopted IFRS as endorsed by the Financial Supervisory Commission of the Republic of China (FSC) (T-IFRS) where the timing of revenues may differ from that reported under IFRS as published by the IASB. In fact, under T-IFRS, Chunghwa’s revenue from selling the prepaid phone cards is recognized at the time the card is sold by the Taiwan Company, while under IFRS 15 paragraph 39 by IASB, an entity shall “recognize revenue over time by measuring the progress toward complete satisfaction of that performance obligation,” namely over time as consumed. Chunghwa does provide a disclosure of this different treatment in the management commentary, but the revenues of Chunghwa are not categorized separately for prepaid phone card sales. Such a disclosure leaves the investor uncertain as to the amount of differences in revenue recognition timing between T-IFRS and IFRS. Thus, comparing T-IFRS and IFRS financial reports may require further analyses which increases complexity for investors when the recognition of some revenue categories differs for Chunghwa from Taiwan as compared to companies applying IFRS as published by IASB like Swisscom AG from Switzerland.

As highlighted by Doupnik and Richter (2003), differing home country languages could be a further source of impaired comparability when converting financial reports to the host country’s language. For example, Chunghwa Telecom Ltd. translated its Chinese financial reports to English. Swisscom AG and Deutsche Telekom translated their German financial reports to English. Translation to English can be influenced by the translator.

With regard to lag, for example, South Africa adopts IFRS as published, but European Union countries adopt IFRS with carve-outs and sometimes with a substantial lag. For example, IFRS 9 Financial Instruments with IFRS 4 Insurance Contracts (Amendments to IFRS 4) was effective by the IASB on January 1, 2018, but the EU deferred application of IFRS 9 to January 1, 2021. Consequently, delays due to the EU endorsement procedure and thus differences in effective dates for the adoption of any endorsed standards, could lead companies of different countries to declare their compliance with IFRS even if they refer to different version of IFRS (endorsed or not).

IFRS are principle-based standards, and this implies the necessity of an interpretation and/or a judgment when applying IFRS that could be affected by accountants’ country and personal factors as highlighted by Prather-Kinsey et al. (2018). The definition of “control” is an example of that as IFRS 10 defines “control” as the power of an investor over an investee where the former has the ability to affect returns through its power over the investee (IFRS 10:5–6; IFRS 10:8). The rules-based standards of US GAAP define “control” as having 50% or more of the voting rights of another entity. The application of IFRS 10 could lead to a different result from US GAAP, as the parent company might decide to consolidate an investee under IFRS (40% ownership of voting shares) based on differing interpretations of the term “control.”

However, the differences in interpretation of terms may be mitigated when all companies list on the same stock exchange and, therefore, become subject to the same (high) level of enforcement. In other words, the listing country’s enforcement authority is acting as a regulatory body, in enforcing IFRS for its cross-border listed companies regardless of the location of their home country.

In this study, we adopt a normative approach to provide support for a global supranational regulatory body for all cross-border listed firms that could enhance homogeneity in the application and rigor in enforcement of IFRS as published by the IASB for consolidated financial reporting.

The IASB’s stated objective is to provide financial reporting about an entity that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors in making resource allocation decisions (IASB 2018, ¶1.2). One of its enhancing qualitative characteristics in providing useful financial reporting is comparability.

‘Users’ decisions involve choosing between alternatives, for example, selling or holding an investment, or investing in one reporting entity or another. Consequently, information about a reporting entity is more useful if it can be compared with similar information about other entities and with similar information about the same entity for another period or another date. Comparability is the qualitative characteristic that enables users to identify and understand similarities in, and differences among, items.’ (IASB 2018, ¶2.24-2.25)

Extant studies provide evidence that financial reporting incomparability might be due to inconsistent adoption, application, and enforcement of IFRS (ICAEW 2018). Therefore, we review previous studies that discuss the divergence of IFRS adoption between countries, IFRS application between firms, and the extent to which these divergences affect CFR. After reviewing these divergences in country adoptions and company applications of IFRS, we study the discourses of the IASB and IOSCO with national jurisdictions to assess the volume of their enforcement-related interactions overtime.

As Brown et al. (2014) observe, it is unlikely that the mere adoption of one set of accounting standards alone will automatically mitigate incomparable financial reporting. Tarca (2020) points out the potential large impact of various factors at a national level on the compliance of IFRS and, therefore, on the CFR. She also encourages further research that investigates how various entity and country factors interact to achieve comparability. In the same vein, Kleinman et al. (2019) provide evidence of the persisting relevance of national characteristics/settings even in a context of undersigned agreements that settle supranational cooperation and regulation.

There is also empirical support for the notion that homogeneous IFRS application requires a supranational enforcer (Ball 2016, 2006; Pope and McLeay 2011; Schipper 2005). Quagli et al. (2020) raises concern about the need for a supranational enforcement agency in providing homogeneous enforcement of international accounting standards. The objective of this study is to suggest an organizational dynamic such that IOSCO, in corporation with national regulatory bodies, should have a stronger role in the global promotion of homogeneous enforcement of IFRS application as published by the IASB for consolidated financial reports of cross-border listed firms.

To achieve the objective of this study, we use a inductive approach to define the theoretical framework, develop our literature review, and state our research question. We adopt the Gioia et al. (2012) qualitative theoretical framework to frame our literature review and to prescribe an organizational dynamics change to achieve CFR globally (see Fig. 1). First, we conduct a simple content analysis of the publicly available documents and minutes of IASB and IOSCO meetings with national regulatory bodies to understand the extent to which IASB and IOSCO engaged between them and with national regulatory bodies in pursuing the enforcement of IFRS across jurisdictions. Then, we refer to Gioia et al.’s framework (2012) to identify and prescribe organizations’ interrelationship dynamics change process. That is, given the current context of IFRS adoption and application, we recommend an organizational dynamic change such that IOSCO increases its role as the portal for global enforcement of cross-border listed firms’ IFRS-compliant financial reports. To this end, we present the establishment of an IOSCO Monitoring Board (IOSCO MB) as the institution to monitor and review the financial reports of cross-border listed firms stating compliance with some form of IFRS. IOSCO, through the IOSCO MB, would strictly collaborate with national authorities and review, at least once every three years, the financial report of firms that cross-border list and state compliance with IFRS. This review would be based on the comment letter approach as a dialog between the cross-border listed firms and the IOSCO MB that would deem the company as complying with full-IFRS or not at the end of the process. This change is proposed to mitigate differences in enforcement of IFRS at the country level and thus enhance global CFR.

Gioia et al. (2012) Inductive Research Approach

Our contribution to the literature is threefold. One is providing a review of studies on the differences in financial reporting not only de jure but also de facto. Second, we study the discourse about IFRS and its enforcement between IASB and IOSCO with national regulatory bodies to assess the extent of their actions toward global enforcement of IFRS. Third, we propose an international organization dynamic that is forward-looking as a next step in instituting CFR across national jurisdictions. These results could be useful to national standard setters and the IASB in meeting its “usefulness” objective and CFR characteristic, and useful to national accounting regulators and investors in achieving a more efficient global capital market.

Following is the background. We argue, based on prior studies, that there are differences in IFRS adoption, application, and enforcement across the world and that these could impair the de facto CFR of IFRS financial reports. Next is the methodology, followed by the findings. These findings are used to suggest a global organizational dynamic change that could improve CFR of cross-border listed firms stating compliance with IFRS. Lastly are the conclusions and limitations of the study.

Literature review

We articulate our literature review to systematically discuss most part the potential sources of incomparability of accounting information in an IFRS environment that have been object of previous studies. To this end, we categorized our literature review according to three lines of possible source of incomparability of accounting information: adoption, application, and enforcement. We also addressed our focus on the cross-border listed firms that are probably more exposed to the risk of incomparability for all the issues related to adoption, application, and enforcement.

Literature review about differences in IFRS adoption across the world

Adoption of IFRS has not been consistent across countries. Some countries adopt IFRS as published by the IASB, while others adopt IFRS with carve-ins and carve-outs (see Felski 2017) or adopt IFRS with a substantial lag. For example, South Africa adopts IFRS as published, but the European Union adopts IFRS with carve-outs and sometimes with a substantial lag. That was the case of the EU that carved-out from IAS 39 Financial Instrument, (1) the use of the “full fair value option” for all financial assets and liabilities, especially regarding a company’s liabilities, and (2) the “hedge accounting” provisions. The EU endorsement process of IFRS has sometimes resulted in an EU IFRS adoption lag for as many as three years. For example, IFRS 9 Financial Instruments with IFRS 4 Insurance Contracts (Amendments to IFRS 4), were effective on January 1, 2018, but the EU deferred application of IFRS 9 to January 1, 2021. In European companies’ financial reports, they state compliance with IFRS as adopted by the EU. In essence, the EU has adopted IFRS but with carve-outs and lags.

If we refer to the information about IFRS adoption by jurisdiction from the IASB’s website of March 13, 2020, we find that of the 165 countries listed on the IASB website, only 68 countries or approximately 41% of the countries have fully adopted IFRS. By fully adopted we mean required for domestic and foreign companies as published by the IASB and without carve-ins and/or carve-outs and/or lags.

Zeff and Nobes (2010) argue that only a few countries have “fully adopted” IFRS as many jurisdictions have not incorporated the full text of IFRS without any change directly and instantly into their national accounting regulations. The lack of the IASB’s IFRS adoption comparably across legal jurisdictions is what we define as “pseudo-adoption” or a “CFR gap.” In this sense, the comparison of one country’s pseudo-IFRS-compliant company’s financial reports with that of a another country’s pseudo-IFRS-compliant company’s set of financial reports, may be misleading, as each country has endorsed its own version of IFRS (De Luca and Prather-Kinsey 2018). Moreover, pseudo-adoption timelines may vary across national jurisdictions when IFRS must go through a co-endorsement process like in the EU. In fact, Felski (2017) empirically finds that the pseudo-adopted IFRS financial reporting can impair CFR across countries. Felski (2017) examines countries that modify adoption of IFRS to assess the extent to which CFR is impaired. This study provides evidence that some countries experience difficulties in implementing the latest version of IFRS or ensuring proper translation of the standards due to a lack of resources, while other countries endorse IFRS with modifications to represent their financial reporting environment. It follows that the specifics of how countries modify IFRS adoption may result in differences in comparable financial reporting between different countries, though all state IFRS compliance.

Some studies find that pseudo-IFRS adoption results in useful information. Mita et al. (2018) examine whether the indirect effect of IFRS adoption results in increasing foreign investors’ ownership through improvement in CFR. Drawing on a sample of listed companies from18 countries, 2003 to 2012, the authors show that there is a positive association between the level of IFRS adoption (measured as fully adopt, partially adopt, adopt with delay, or adopt with modification) and the level of CFR. Because of this improvement in CFR, firms experience increases in foreign investor ownership. Barth et al. (2008) find that firms “exhibit less earnings management, more timely loss recognition, and higher value relevance when complying with IFRS than accounting amounts of firms that apply domestic standards” immediately before and after IFRS adoption. Generally, these results are consistent with the notion that IFRS adoption improves CFR.

The seven largest developed countries in the world include Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, and the USA. None of these economies fully adopted IFRS for all its listed firms without carve-in or carve-outs. This should be alarming as there have been times when these economies were concerned that adoption of IFRS was not achieved globally. For example, during periods of scandals (e.g., Enron) and financial crisis (e.g., Asian of 1997 and globally in 2008) there was demand by the G7 (as part of the G20) for global regulation to limit asymmetric information among market participants. Kothari and Lester (2012) argue that the lax regulation during the financial crisis resulted in the advent of the Great Depression of 2008. We contend that one of the reasons the largest seven economies or the G7 was not fully adopting IFRS may have been because of the differences allowed in its application and enforcement. Also, management’s incentives, language, and country of operations may influence application of IFRS.

Literature review about differences in IFRS application across the world

Extant accounting research shows that application of IFRS’s principles-based standards is influenced significantly by management’s incentives, language, and country-related factors (e.g., socio-political and cultural environment) differently between countries. We provide a review of the literature that accordingly substantiates differences in application of IFRS between countries.

Some managers are incentivized and governed by the capital market, whereas other managers are incentivized by creditors. Some managers seek capital market growth, while others seek social responsibility. Moreover, some scholars find evidence that over time, after countries adopt IFRS, managers/accountants become familiar with IFRS and adapt implementation of IFRS to meet their local needs (Liao et al. 2012; Larson 1997). Other authors (Lasmin 2011; Chua and Taylor 2008; DiMaggio and Powell 1983) find that IFRS adoption is driven more so by social legitimization pressures than economic benefit pressures.

Ball et al. (2003) study 2726 East Asian companies’ annual earnings announcements and infer that “it is misleading to classify countries by standards, ignoring incentives.” They find that financial reporting practice under a given set of standards is significantly influenced by management and auditor incentives. Burgstahler et al. (2006) study management’s earnings reporting incentives for European private and public firms in light of accounting standards harmonization. The sample includes 378,122 firm-year observations during 1997–2003. They find that for public firms of 13 EU countries, managements’ reporting incentives explain earnings informativeness (especially in weaker legal enforcement countries). Pope and McLeay (2011) study the literature about EU’s adoption of IFRS. They find that the application of IFRS adoption is not uniform across Europe and depends on preparer incentives and the effectiveness of local enforcement.

Liao et al. (2012) study the CFR output values (earnings and book values) using 1153 French and 1236 German firm-year observations. Their empirical results reveal that output values are significantly influenced by management incentives. They conclude that the properties of financial reporting under IFRS vary between French and German firms after the year of initially adopting IFRS. These differences are associated with institutionally influenced management incentives varying between countries resulting in IFRS being applied differently. Daske et al. (2013) study a large panel of voluntary IAS adopters from 1990 to 2005 across 30 countries. They also find that IAS application depends on management’s reporting incentives. Through a single-country analysis on Italian not-listed companies, Di Fabio (2018) provides evidence that companies that apply IFRS in their financial statements are leveraged and, in many cases, financially distressed companies, differently from the UK setting and similarly to Germany.

There is significant cross-sectional heterogeneity in application of IFRS, some of which is related to management’s corporate governance incentives. Managers may be able to profit by giving a false signal to the market. Wójcik (2006) argues that differences exist in corporate governance practices between countries and industries. Yoshikawa and Rasheed (2009) find almost no evidence of convergence in corporate governance between countries. They find that while IFRS may be implemented comparably globally in form, this usually is not carried out in practice due to differences in management incentives (Felski 2017). We conclude, then, that application of IFRS may vary between countries as a result of differing institutional factors influencing management in application of IFRS.

In addition to management incentives, other accounting studies imply that complex language, such as that of IFRS, is subject to management obfuscation. Evans (2018) emphasizes that translation in accounting is not a simple technical, but a socio-cultural, subjective, and ideological process. Beyond accounting practices, the legal and cultural background of a country affects the wording of national law itself (Alexander et al. 2018). Different wordings in national laws, and different interpretations of similar wordings in national laws, can be explained by taking recourse to the philosophy of language (Alexander et al. 2018).

Complex language commingles two latent components of linguistics: the information component and the obfuscation component. The information component of a language is technical disclosures about a business and results in symmetric information between management and the market. The obfuscation component of a language is the component intended to increase asymmetry and reduce the informativeness of disclosures. Bushee et al. (2018) used conference call transcripts from Thomson Reuters StreetEvents, returns, and accounting data from CRSP Compustat and I/B/E/S management forecasts from 60,172 firm quarters between 2002 and 2011. Their findings suggest that the information component of linguistic complexity is negatively associated with information asymmetry and that the obfuscation component of information complexity is positively associated with information asymmetry.

Language complexities resulting in information obfuscation can be intentional or unintentional. Bushee et al. (2018) are referring to intentional information obfuscation resulting in information asymmetry. English language barriers can lead to unintentional obfuscated disclosures by foreign firms. Unintentional obfuscation may arise from non-English-speaking firms not speaking proficiently. Brochet et al. (2016) discuss that because non-English firms face institutional and cultural barriers in reporting in English, such may result in opaque disclosures to the financial markets. In other words, markets may face unintended obfuscation from foreign firms presenting their financial statements in a foreign language. Lundholm et al. (2014) findings are contrary. They sample foreign private issuers’ Form 20-F filings and 10-K filing between 2000 and 2012 from EDGAR and Compustat. This resulted in a sample of 3499 foreign firm-year observation from 45 countries and 37,344 US firm-year observations. Their major finding was that the readability of text and use of numbers in annual filings of foreign firms were clearer and with more numbers than US firms. Lundholm et al. (2014) conclude that “foreign firms are responding to a perceived reluctance on the part of US investors to own them and attempt to lower the investors” information disadvantage or psychological distance by providing clear disclosures. Findings then are not conclusive regarding unintended obfuscation, but clearly suggest opaque financial reporting using IFRS whether a US or non-US filer. In the same vein, Prather-Kinsey et al. (2018) conducted a survey of 180 English-speaking accountants based in the USA and India. Their findings suggest that accountants’ decision to consolidate is significantly influenced by work location and core self-evaluations. This is more evident when the term “control” is interpreted according to the principles-based terminology, rather than when it is interpreted using rules-based terminology. This principles-based language may affect CFR in an IFRS environment.

In addition to management incentives and language differences, country location incentives (i.e., legal institution, product market competition, and governance structure between legal jurisdictions) may result in inconsistent application of IFRS by those managers purporting to be IFRS compliant (Ball et al. 2015, 2003, 2000; Daske et al. 2013; Burgstahler et al. 2006; Haw et al. 2004; Leuz et al. 2003; Fan and Wong 2002).

This review of previous studies confirms that interpretation and use of IFRS may differ between countries, reflecting substantial and long‐standing differences in management’s application of IFRS principles-based standards (Brown et al. 2014; Mohammadrezaei et al. 2013; Schipper 2005; Whittington 2005). The IASB itself still struggles to provide comparable application and enforcement of its IFRS globally. In fact, responding to investor demands, the IASB has recently started a new project to achieve more “comparable information in the statement of profit or loss and a more disciplined and transparent approach to the reporting of management-defined performance measures (‘non-GAAP’)” (IASB 2019).Footnote 2 Additionally, enforcement of IFRS is questionable when most of the economies fully adopting IFRS are in weak legal jurisdictions as defined by La Porta et al. (1998).

Literature review about difference in IFRS enforcement across the world

Several studies have demonstrated that the cost of capital, liquidity, and others measures of financial markets efficiency, in a IFRS context, depend upon the enforcement intensity existing in different countries (Silvers 2016; Christensen et al. 2013; Landsman et al. 2012; Armstrong et al. 2010; Li 2010; Daske et al. 2008). When the enforcement system is stronger, financial analysts’ estimates are more accurate (Demmer et al. 2019; Preiato et al. 2015; Byard et al. 2011), institutional investors’ ownership increases (Florou and Pope 2012), and earnings management behaviors and accruals anomaly decrease (Kim and Lin 2019; Houqe et al. 2012; Cai et al. 2011). Moreover, in countries with stronger enforcement, financial disclosures improve (Gros and Koch 2018; Glaum et al. 2013). The lack of CFR is also empirically evidenced in the IFRS-based earnings in financial reports of differing legal jurisdictions (Phan et al. 2020). Abad et al. (2018) use market microstructure proxies for information asymmetry to examine the effects of IFRS adoption on the level of information asymmetry in the Spanish stock market. They provide evidence that markets benefit from the mandatory switch from local accounting standards to IFRS as a reduction in information asymmetry, even in case of lower enforcement-level jurisdictions.

In today’s capital markets, enforcement of accounting standards still takes places at national levels through various types of regulatory structures such as local stock exchanges, government agencies, and regulatory organizations (De Luca and Prather-Kinsey 2018). For example, in European Union (EU) countries, standards must be endorsed by the EU before they are sanctioned by the EU and its member states. Enforcement in Europe is not under a common supranational organization as the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) is an independent EU Authority that simply fosters supervisory convergence among security regulators. In the USA, IFRS is allowed for foreign private issuers complying with IFRS as published by the IASB, without reconciliation to US GAAP. The SEC enforces foreign registrants’ financial reports using a comment letter approach. After reviewing foreign registrant’s IFRS financial statements for compliance, the SEC issues a comment letter for which a firm can remedy deficiencies or defend. A resolution may come about after several rounds of discourse. The comment letters then become public information unless confidential treatment is granted by the SEC.

Comparability remains an open issue as the mere existence of a single authority that enforces both sets of standards (IFRS and US GAAP) is not a guarantee in itself of comparability. But this issue probably goes beyond the scope of our study. In fact, we aim at focusing on the comparability issue within an IFRS environment and not between IFRS and other sets of standards (as for example in the US markets where there is a sort of competition among sets of standards). The above examples provide some evidence on possible differences in application and enforcement of IFRS by differing legal jurisdictions.

It is widely acknowledged that without an effective global enforcement system, it is difficult to achieve further improvements in financial reporting through the adoption of high-quality accounting standards (Quagli et al. 2018). Extant studies highlight that the global accounting system lacks a consistent rigorous enforcement mechanism to ensure consistent and quality reporting of IFRS-compliant financial reports across legal jurisdictions (Kleinman et al. 2019; Mohammadrezaei et al. 2013). At present, IOSCO is the international body that brings together the world's securities regulators, is recognized as the global standard setter for the securities sector, develops, implements, and promotes adherence to internationally recognized standards for securities regulation and works intensively with the G20 and the Financial Stability Board (FSB) on global regulatory reform (De Luca and Prather-Kinsey 2018; Kempthorne 2013). Its objectives (IOSCO 2017b) are protecting investors, ensuring that markets are fair, efficient, and transparent and reducing systemic risk. IOSCO has several memorandums of understanding for enforcement, with the cooperation of over 130 national regulators (IOSCO 2019). Therefore, we believe that IOSCO should assume a stronger role in promoting homogeneous enforcement of IFRS worldwide, especially for cross-border listed firms. To this end, we prescribe an organizational dynamic change of IOSCO’s organization structure to achieve CFR globally.

The efforts to achieve homogeneous enforcement of IFRS worldwide

The objective of our study is to suggest a global organization dynamic change in the enforcement of IFRS through IOSCO to enhance CFR globally. First, we conduct a simple qualitative analysis of the content of IASB and IOSCO documents to understand the trend and current status of CFR in application and enforcement of IASB’s IFRS. We consider this analysis as supplemental to our proposal of a global organization dynamic. In fact, we aim at providing an up-to-date picture of the current discourse and engagement level about the enforcement of IFRS among the main global actors, IASB and IOSCO, and the national regulatory bodies.

We use a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) package (Hoque 2018; Pratt 2009) NVivo, to perform content analysis of IASB, and IOSCO deliberations. We imported a PDF version of each IASB and IOSCO public document into NVivo software and searched for specific words within the documents using NVivo (Perkiss et al. 2020). After establishing a procedure for classifying documents (according to the meeting to which they belong and participants) and searching on select words, we run separate qualitative analyses of the IASB documents and IOSCO documents.

IASB content analysis

To sort qualitative data, we perform a content analysis of IASB’s documents and events to see the effective status of their stated efforts in achieving enforcement of IFRS through their discussion with enforcement bodies around the world. A search of the IASB’s website from 2006 to 2019 is conducted (https://www.ifrs.org). We also search the IASB’s deliberations in developing an understanding of the history of its interactions with IOSCO and national regulatory bodies.

From https://www.ifrs.org in the “News and Events” section we find a total of 597 IASB meetings and events that include 9,585 documents from 2006 to 2019. We note which external participants are involved in the IASB meetings and events. That is, for every meeting we list all of those who participate. This information is provided in one of the documents of every meeting. We then determine whether the participant is the IASB (internal) or non-IASB organization (external). We define a “contact” every time there is an official meeting or event jointly held or participated in by IASB and an external party whose minutes are publicly available.

Of the 597 meetings, we find that there were 562 contacts, as above defined, between the IASB and external parties. We provide the following example to illustrate how contacts are enumerated. As shown below, in the December 20, 2006, meeting there are 3 contacts: IASB with North American Insurance Enterprises GNAIE, Allianz, and AXA Group. Or in the meeting on December 3, 2008, there are 2 contacts: IASB with Nippon Life Insurance Company and Samsung Life Insurance Corporation. Thus, the number of contacts is not the same as the number of meetings.

Illustration of how # contacts were computed

No | Date | Type | Topic | External party | Type of external party |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | December 20, 2006 | Meeting | IAS 37 Round-table discussion | North American Insurance Enterprises GNAIE | Insurance |

IAS 37 Round-table discussion | Allianz | Insurance | |||

IAS 37 Round-table discussion | AXA Group | Insurance | |||

2 | November 25, 2008 | Meeting | North American Round tables—Global financial crisis | Group of North American Insurance Enterprises (GNAIE) | Insurance |

3 | December 3, 2008 | Meeting | Asian Round tables—Global financial crisis | Nippon Life Insurance Company | Insurance |

Asian Round tables—Global financial crisis | Samsung Life Insurance Corporation | Insurance | |||

4 | September 7–8, 2017 | IFRS Conference | EY 16th IFRS Congress 2017 in cooperation with the IFRS Foundation | Allianz | Insurance |

5 | September 6–7, 2018 | Events | EY 17th IFRS Kongress 2018 | Allianz | Insurance |

Next, we study, in depth, the 33 (out of 562) contacts between IASB with IOSCO and other national regulatory market authorities. These 33 contacts are associated with 26 meetings. Following is an example of how data are extracted and classified from a January 28, 2013, meeting. In the meeting on January 28, 2013, the IASB discusses the disclosures in financial reporting. We find 6 documents of the meeting from their website. They are as follows.

Illustration of How a Data extraction and Classification of the IASB Meeting on January 28, 2013 was Derived

Year | Date | Type | Topic of meeting | Documents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2013 | 28 January | Meeting | IASB Discussion Forum: Disclosures in Financial Reporting | Meeting agenda.pdf |

Papers: The disclosure problem: setting the scene.pdf | ||||

Papers: Communication not compliance (Hermes Equity Ownership Services).pdf | ||||

Papers: Preparer response (HSBC).pdf | ||||

Papers: Disclosures in Financial Reporting: summary.pdf | ||||

Feedback statement.pdf |

By reading the meeting agenda of the above January 28, 2013 meeting, we find that there were several external parties involved in this discussion. These parties are then classified into type. For example, the EFRAG is a European advisory group, FASB in a national standard setter, etc. These examples are presented in the illustration below.

Illustration of How of External Parties was Determined using an IASB meeting on January 28, 2013

Year | Date | Type | Topic of meeting | External parties | Type of external parties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2013 | 28 January | Meeting | IASB Discussion Forum: Disclosures in Financial Reporting | European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) | European advisory group |

ESMA/CESR | National Financial Market Authority | ||||

FASB | National Standard Setters | ||||

International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) | National Standard Setters | ||||

The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland (ICAS) | Professional | ||||

Hermes Equity Ownership Services | Company | ||||

HSBC | Bank | ||||

Novartis | Company | ||||

Harding Analysis | Company | ||||

International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) | IOSCO | ||||

Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) | National Financial Market Authority | ||||

KPMG | Auditing firm |

NVivo is useful in searching for specific content and organizing large numbers of documents into years and months (qualitative data analytics). We are interested in researching whether any activity of the IASB in promoting a consistent enforcement globally has occurred. Hence, we use NVivo to search for the keywords “enforce” with its stemmed words (such as enforcing, enforceable, enforcement, enforceability) in all 9585 IASB documents. We are aware that IASB is not an enforcement organization and does not have any authority to issue enforcement rules or regulations, to verify the compliance level, or to inflict sanctions. We limit the content analysis only to keywords “enforce” with its stemmed words. Thus, we simply expect to assess the extent to which IASB has engaged with external parties to promote and foster the enforcement of its standards across the world. We find that enforcement activities are mentioned in several documents. However, most of the references regarding enforcement activities are mentioned in meetings not participated in by capital market regulatory parties. They mostly appear in the meeting with IFRIC, or IASB itself, or joint IASB and FASB meetings. Thus, we run again this analysis (search query with the keyword “enforce”) with the documents from meetings that were participated in by market regulatory bodies.

IOSCO content analysis

We use content analysis to learn about IOSCO’s discussion with IASB on enforcement of IFRS and other related topics.

Content analysis of all IOSCO documents from iosco.org, in the “Media Room” and “Publications” including media releases, articles, speeches, public reports, annual reports, comment letters, information repositories, agreements, and regulator’s statements, is conducted from 1989 to 2019. This search results in 3,188 documents. NVivo is used to conduct a content analysis of the total 3118 documents for the keywords “International Accounting Standards Board,” “International Accounting Standards,” “International Financial Reporting Standards,” or their abbreviations. This NVivo search results in a list of 338 from the total 3118 documents (10.84%).

From this search we want to learn about whether there are any enforcement-related discussions that IOSCO has made with other regulatory bodies. NVivo is used to search within the 338 documents for the keywords “enforce,” “regulate,” “penalty,” “comply,” “sanction,” or “support” and their stemmed words. In fact, IOSCO is the global standard setter for the securities sector and develops, implements, and promotes adherence to internationally recognized standards for securities regulation. For this reason, we decided to extend the content analysis to the aforementioned keywords that relate to securities regulation activities. There are 316 documents (93.49% of 338 documents) found. Alternatively, each time one of the key words appears, we define it as a reference.

We then match the IOSCO content analysis time frame with that of the IASB content analysis time fame. The time frame of the IASB content analysis is from 2006 to 2019. We then limit the 316 IOSCO documents to those within this same time frame, 2006–2019, resulting in 239 IOSCO documents and 17,132 keyword references.

Discussion of results

Content analysis of IASB’s meetings and events

In Appendix 1 we report Tables 1, 2, and 3

Table 1 in Appendix 1 illustrates the number of contacts between the IASB with external parties from 2006 to 2019. There are 562 contacts between the IASB and external parties. The IASB has most of its contacts (24.56%) with national standard setters. More than half of these contacts are from joint meetings between the IASB and FASB (76 out of 138 contacts). However, we find only 2.14% (12 contacts) of total contacts with IOSCO and 3.74% (21 contacts) with national financial market regulatory authorities. IOSCO already has established relationships with over 130 national securities commissions in their respective jurisdictions (IOSCO 2019) upon which the IASB could benefit. It appears that the IASB affirmed the relevance of a homogeneous enforcement activity at the global level, but engaged with national securities commissions and IOSCO only to a limited extent. This was expected as the IASB is not (and cannot act as) a regulatory body. Instead, thanks to the engagement with its members national regulatory authorities, IOSCO demonstrates to be in a potentially good position to facilitate the global improvement of CFR through rigorous and homogeneous enforcement of its standards worldwide.

We then study, in depth, those documents from the contacts of IASB with IOSCO and other National Market Authorities (determined from the prior step). We find 33 such contacts from 26 meetings as is presented in Table 2 (Appendix 1) Most of these contacts are in 2009, 11 contacts, the year after the financial crisis. Only four of these 33 contacts are with IOSCO: 2006, 2008, 2009, and 2013. It is quite surprising that since 2013, the IASB has not had a public discourse (meeting, conference, etc.) with IOSCO in developing homogeneous IFRS enforcement with securities authorities across the globe. The heightened discourse of IASB with IOSCO and capital market regulators during the financial crisis speaks to the need of securing rigorous monitoring and enforcement of IFRS reporting to provide more efficiency and stability in the global financial markets.

Next, NVivo is used to search for the keyword “enforce” with its stemmed words (such as enforcing, enforceable, enforcement, enforceability) in all 9585 IASB documents. Then we include only those meetings that are participated in by regulatory securities parties in Table 3 (Appendix 1). In Table 3 (Appendix 1) we list the name of the document, year, month, title of meeting, and references. A reference is the number of times a keyword or its stem occurs in a document. We find only 20 documents from roundtable meetings and meetings with the IASB monitoring board held jointly with regulatory securities parties that mention the keyword “enforce.” Most of these documents were during the financial crisis and tapered off after the year 2009. Again, at least to the extent of the official meetings’ minutes content, this could suggest a limited engagement to achieve the homogeneous enforcement of IFRS globally. After studying the documents of Table 3 (Appendix 1), we conclude that IASB promotes the enforceability of its standards, but the efforts toward a consistent enforcement of IFRS throughout the world still need to be strengthened. To the best of our knowledge, there are no current formal projects on which the IASB is working together with IOSCO or national market authorities toward a converged global enforcement of IFRS as published by the IASB.

Content analysis of IOSCO’s documents

The goal of searching IOSCO’s website, namely www.iosco.org, is to learn about its enforcement activities, especially enforcement of IFRS. Table 4 (Appendix 1

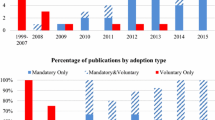

Figure 2 presents the same information, but in graphic form. The peak year of the occurrence of these terms is 2017 (14.04%) and the lowest year of occurrence of these terms is 2012. Most of the 2017 references (1670 of 2409) are in one document, namely “Methodology-For Assessing Implementation of the IOSCO Objectives and Principles of Securities Regulation.” However, the peak year of the number of documents, 55, in which these terms appear, is 2018. This shows the growing discourse between IOSCO and the IASB especially more recently. In fact, despite a more fluctuating trend after 2010, we observe peaks in 2013, 2015, and 2017 in terms of number of references. This provides some evidence that at least biennially the topics related to the enforcement strategy are more recurring in IOSCO meetings’ agenda. These results are promising because the greater the enforcement-related and IASB-related discourse between IOSCO and the IASB, the more likely a consistent and rigorous enforcement of IFRS worldwide is on the forefront of their agendas.

Enforcement modeling and organizational dynamics

Prior accounting research studies provide empirical evidence that adoption, application, and enforcement of IFRS varies across legal jurisdictions. Consistent with a rigorous qualitative approach (Gioia et al. 2012), we propose an organizational dynamic with IOSCO as the enforcement promoter of rigorous and homogeneous monitoring of national regulators as well as the comment letter approach for IFRS enforcement, especially for the case of cross-border listed firms stating compliance with IFRS. IOSCO has established relationships with over 130 national regulators (Kempthorne 2013).

Of course, we do not believe that a stronger supranational enforcement effort will solve all the incomparability issues as raised by previous studies and summarized earlier in this paper, but it could mitigate some of the enforcement differences at the country level. Moreover, through its surveillance activity, a global enforcement body could ask cross-border listed companies to provide specific disclosures about the differences that could arise from the adoption and/or application of IFRS in different legal jurisdictions.

The issues related to adoption and application of IFRS are not easily solvable. We propose to enhance the homogeneity of enforcement of IFRS at a global level to reduce incomparability. As suggested by previous studies (Ball 2016, 2006; Pope and McLeay 2011; Schipper 2005), we also believe that a global enforcement entity could help in reducing application issues through the comment letter approach that we present later in this paper.

Figure 3 is the current organization structure of IOSCO. The president’s committee consists of 128 ordinary members from 125 countries and meets annually. The IOSCO Board, which includes 34 securities regulators, is the standard setting body. Not only are developed countries represented but growing and emerging markets are represented in IOSCO’s organization structure too. The regional committees, focusing on regional issues, are represented by all regions of the world.

At present, IOSCO (2019) is the largest international body that has cooperation with over 130 of the world's national securities regulators and.

-

Is recognized as the global standard setter for the securities sector,

-

Develops, implements, and promotes adherence to internationally recognized standards for securities regulation; and

-

Works intensively with the G20 and the Financial Stability Board (FSB) on the global regulatory reform agenda.

Its objectives (IOSCO 2017a, 2017b) are protecting investors, ensuring that markets are fair, efficient, and transparent and reducing systemic risk.

IOSCO itself has already settled several principles enforcement rules in securities regulation (IOSCO 2017a, 2017b). They resolved that the regulator should have comprehensive inspection, investigation, and surveillance powers as well as comprehensive enforcement powers as follows (IOSCO 2017a, p. 6–7).

-

“The regulatory system should ensure an effective and credible use of inspection, investigation, surveillance and enforcement powers and implementation of an effective compliance program.

-

The Regulator should have authority to share both public and non-public information with domestic and foreign counterparts.

-

Regulators should establish information sharing mechanisms that set out when and how they will share this public and non-public information with their domestic and foreign counterparts.

-

The regulatory system should allow for assistance to be provided to foreign Regulators who need to make inquiries in the discharge of their functions and exercise of their powers.”

Regarding Issuers, IOSCO asserts that (IOSCO 2017a, p. 8):

“there should be full, accurate and timely disclosure of financial results, risk and other information which is material to investors’ decisions. Holders of securities in a company should be treated in a fair and equitable manner. Accounting standards used by issuers to prepare financial statements should be of a high and internationally acceptable quality.”

Considering the milestones of IOSCO activities, we find at least two key initiatives relative to surveillance of financial reporting. First, in 2002, IOSCO (2002) established the Multilateral Memorandum of Understanding (2002 MMoU) with its “objectives of protecting investors and ensuring that markets are fair, efficient and transparent” (IOSCO 2019). This 2002 MMoU became the global benchmark for international cooperation in the enforcement of securities and derivatives laws and regulations. Since the 2002 MMoU, the lessons of the global financial crisis, and the experience gained by the signatories to the 2002 MMoU, it became critical to enhance information sharing and cooperation between IOSCO members to meet its objectives.

In 2016 IOSCO established an Enhanced Multilateral Memorandum of Understanding (IOSCO 2019; OICU-IOSCO 2018) “with the expectation that its signatories will increase the effectiveness of their investigations and the enforcement of their jurisdiction's Laws and Regulations, while recognizing the rights and privileges afforded to Persons in their respective jurisdictions.”

EMMoU will co-exist with the MMoU, and this demonstrates that IOSCO’s enforcement is strengthening in cooperation from national jurisdictions. The EMMoU gives IOSCO some key powers such as: to obtain and share audit work papers, communications, and other information; to compel physical attendance for testimony (by being able to apply a sanction in the event of non-compliance); to freeze assets if necessary; to obtain and share existing internet service provider (ISP) records; and to obtain and share existing telephone records. Additionally, the EMMoU envisages the obtaining and sharing of existing communications records held by regulated firms. These new powers, which are set out in full in Article 3 of the EMMoU, will foster greater cross-border enforcement cooperation and assistance among national securities regulators, enabling them to respond to the risks and challenges posed by globalization and advances in technology since 2002.

In the EMMoU we find strong support for the need of cooperation among regulators across jurisdictions that:

is critical to help ensure the seamless and efficient regulation of globally active regulated entities, in a manner fully consistent with the laws and requirements of all the jurisdictions involved.Footnote 3

In the same document, IOSCO affirms (p. 3):

without enhanced supervisory cooperation and information-sharing among the world’s securities market regulators, many of the regulatory reforms that have been proposed around the world may prove insufficient to the tasks for which they are being designed. While regulators have different supervisory approaches, each has a common interest in information-sharing and cooperation based on earned trust in each others’ regulatory and supervisory systems.

Moreover, the EMMoU affirms that (article 2(1)):

Enhanced MMoU sets forth the Authorities' intent with regard to mutual assistance and the exchange of information for the purpose of enforcing and securing compliance with the respective Laws and Regulations of the Authorities.

Later, the EMMoU affirms:

The Authorities represent that no domestic secrecy or blocking laws or regulations should prevent the collection or provision of the information.

Article 3 affirms that:

The Authorities will provide each other with the Fullest Assistance Permissible to investigate suspected violations of, ensure compliance with and enforce their respective Laws and Regulations.

The operative tool to solicit assistance is developing a dynamic/document that is mutually agreed upon and reflecting the confidentiality of the request. However, current procedure starts only in case of suspected misconduct. We believe that the EMMoU should monitoring financial information of cross-border listed firms continuously.

Consistent with this, we suggest that the EMMoU includes the application of IFRS financial reporting as published by the IASB and a comment letter approach, especially for cross-border listed firms. Our proposed organizational dynamic is based on the establishment of a new body within IOSCO, namely the IOSCO Monitoring Board (MB). The IOSCO MB would be composed of technical experts, representative of countries across the globe. When a company lists its securities outside of its home country and states compliance with IFRS, the IOSCO MB should be responsible for reviewing the firm’s filings and issuing comment letters.

The comment letter approach requires several steps. First the firm would request to IOSCO for filing of its IFRS-compliant filings outside of its home country. At least once every three years the IOSCO MB, together with the respective national authority, would review a cross-border listed firm’s financial reporting filings and provide a comment letter(s). These comment letters represent a dialog between the cross-border listed registrant and the IOSCO MB. Each time a firm is issued a comment letter, the registrant would have 10 days to respond to the IOSCO MB or state why an alternative time frame is requested. Firms must respond with a detailed explanation to each of the queries in the IOSCO MB’s comment letter(s). If a firm does not agree with the IOSCO MB’s request, they could request a reconsideration or negotiate with the IOSCO MB. Then we suggest that once the comment letter review process is completed between the registrant and the IOSCO MB, IOSCO would then have up to 10 days to disclose to the public the comment letter(s) correspondence and IOSCO’s assessment of compliance with IFRS.

Figure 4 illustrates the proposed IOSCO organization modified structure with the MB review and IOSCO enforcement of cross-border listed firms’ IFRS financial reports according to the dynamic inductive model that, we believe, better fits the processes and phenomena under investigation. The MB would work through IOSCO using the comment letter approach. Moreover, IOSCO could require cross-border listed firms to cooperate with the MB through its MMoU and EMMoU with cooperative nations. Finally, IOSCO would assess whether the financial reports are full-IFRS compliant or not and make all correspondence and its assessment public.

However, the solution that we propose lies its probability of success on the willingness of the corresponding governments to put resources and force behind every initiative that IOSCO tries to undertake. Actually, the EMMoU is based on the expectation that its signatories will, by availing themselves of new forms of assistance and continuing to provide each other with the possible fullest assistance, increase the effectiveness of their investigations and the enforcement of their jurisdiction's laws and regulations. Therefore, the establishment of the IOSCO MB and the adoption of the comment letter approach will be effective to the extent to which IOSCO members will support this initiative with resources and actively collaborate with it in facilitating the dialog between IOSCO and the cross-border registrants. After all, IOSCO is encouraged by the efforts that its members and signatories have made to reform legislation and achieve compliance with the MMoU. Consequently, the EMMoU is a step forward for IOSCO to further pursue global and homogeneous enforcement along with the effective co-operation among its signatories.

Conclusions, limitations of the study, and suggestions for further research

The objective of this study is to propose an organizational dynamic for improving global CFR through rigorous and converged global enforcement of IFRS. In the background of this study, we reviewed previous studies which provided evidence that adoption of IFRS varies by legal jurisdiction, application of IFRS varies by company, and enforcement of IFRS varies from weak to strong regulated national stock exchanges.

As more than 165 countries have adopted some form of IFRS reporting, investors need to be able to compare the financial reports of firms listed across borders. The IASB admits that CFR has yet to be improved. For example, they argue that companies compute subtotals differently and investors create their own subtotal differently such that companies’ income statement subtotals, like operating income, cannot be compared for similarities and differences.

We also observe the current status of IOSCO’s membership, enforcement achievements, and organization structure and review the market authorities’ comment letter approach to establish a rigorous and global enforcement framework for the IASB’s IFRS. After having transformed the static data that we collected, observed, and analyzed based on a rigorous inductive approach, we propose an organization dynamics change for IOSCO. In the same vein of Quagli et al. (2020), we believe that a global enforcement authority could achieve the homogenous enforcement of IFRS at a global level. However, we are also aware that presently IFRS enforcement activities are legally engrained at the country level. Therefore, IOSCO currently cannot intervene in national state’s laws as it can only make recommendations, should strengthen its engagement with local enforcement authorities in promoting a homogeneous enforcement of IFRS globally. We suggest IOSCO as the institution to monitor and review the financial reports of cross-border listed firms stating compliance with some form of IFRS. IOSCO, through the IOSCO MB, would strictly collaborate with national authorities and review, at least once every three years, the financial report of firms that cross-border list and state compliance with IFRS. Based on its review, IOSCO would then deem the company as complying with full-IFRS or not. The comment letters between a firm and IOSCO’s MB and IOSCO’s assessment of IFRS compliance would be made public by IOSCO once the review (comment letter process) and assessments are complete. This review activity could initiate firstly on a voluntary basis as a way to assess its impact on financial markets and investors. Only at a later time, would it be possible to understand whether there is evidence to mandate this IOSCO comment review letter process for all cross-border listed firms stating IFRS compliance. This approach would bring cross-border listed firms’ IFRS financial reporting closer to CFR. Investors, then, would be better able to compare the financial reports of IFRS firms of different regulatory jurisdictions.

This study has several limitations. Generally, the settlement of a supranational enforcement body may not find acceptance by sovereign countries, that is, granting IFRS regulation to another body. Even in EU, with its highly integrated markets, IFRS enforcement authority lies with the single member states and ESMA has only a coordinating and recommending role. Moreover, we do not contend that having a rigorous global-level enforcer is all that is needed to obtain an efficient global capital market. In fact, each element in the application and adoption of IFRS would need to be perfected. However, we believe that pursuing the consistency of enforcement at a global level could be an additional way to mitigate sources of incomparability of financial reporting of cross-border listed firms due to ambiguities in adoption and application of IFRS. Notwithstanding, there are multiple factors that affect global capital market efficiency for which we do not address in our proposed organization dynamics change. For example, instituting IOSCO as the global enforcer of IFRS is costly and these organization change costs may outweigh the “usefulness” criterion to investors and creditors. Few studies have evidence on a regulator’s costs and benefits from IFRS adoption. As stated by Leuz and Wysocki (2016) there is a paucity in empirical evidence on the quantitative cost–benefit and its spillovers from a single international regulatory body.

Companies will probably continue to conform to their societal norms and local environments. Hence, we suggest our organization change dynamic as a means to mitigate, not totally eliminate, incomparability in IFRS enforcement. Management may continue to have the incentive and ability to provide opaque disclosures, but we believe that more transparent disclosures will emanate from IOSCO’s enforcement of firms’ financial reports. Local market enforcers are interested in preserving the interests of their local economies’ survival in the market place. IOSCO may not be able to eliminate all biases in enforcement, but with an international IOSCO monitoring board membership, some of these biases may be dampened. Finally, we do not address the IFRS Interpretations Committee’s timeliness or lack thereof as an impediment to global CFR (see Quagli et al. (2020)).

We do not contend that suggesting IOSCO as an enforcement organization for IFRS is a cure-all, but we do suggest it as a next step toward improving comparability in the financial reporting of cross-listed firms stating compliance with IFRS. We also admit that we have no evidence of an existing supranational enforcement scenario, but we believe that this organization dynamic could address the issues raised by previous studies about the need of a supranational enforcement body as a way to improve comparability of financial reports, especially in the case of cross-border listed firms. Further research is needed to empirically support this proposal and provide an estimation on the cost of global securities regulation enforcement of IFRS as published by the IASB through IOSCO in cooperation with national regulatory bodies for cross-border listed firms.

Change history

31 August 2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note

Notes

https://www.ifrs.org/news-and-events/2019/12/iasb-proposes-to-bring-greater-transparency-to-non-gaap-measures/ (accessed on March 27, 2020).

https://www.ifrs.org/news-and-events/2019/12/iasb-proposes-to-bring-greater-transparency-to-non-gaap-measures/ (accessed on March 9, 2020).

(IOSCO, 2010, Principles Regarding Cross-Border Supervisory Cooperation—Final Report, p. 31, available at http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD322.pdf).

References

Abad, D., M.F. Cutillas-Gomariz, J.P. Sánchez-Ballesta, and J. Yagüe. 2018. Does IFRS mandatory adoption affect information asymmetry in the stock market? Australian Accounting Review 28 (1): 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/auar.12165.

Alexander, D., H. de Brébisson, C. Circa, E. Eberhartinger, R. Fasiello, M. Grottke, and J. Krasodomska. 2018. Philosophy of language and accounting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 31 (7): 1957–1980. https://doi.org/10.1108/aaaj-06-2017-2979.

Armstrong, C.S., W.R. Guay, and J.P. Weber. 2010. The role of information and financial reporting in corporate governance and debt contracting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2–3): 179–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.10.001.

Ball, R. 2006. International financial reporting standards (IFRS): Pros and cons for investors. Accounting and Business Research 36 (sup1): 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2006.9730040.

Ball, R. 2016. IFRS—10 years later. Accounting and Business Research 46 (5): 545–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2016.1182710.

Ball, R., S.P. Kothari, and A. Robin. 2000. The effect of international institutional factors on properties of accounting earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 29 (1): 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-4101(00)00012-4.

Ball, R., X.I. Li, and L. Shivakumar. 2015. Contractibility and transparency of financial statement information prepared under IFRS: Evidence from debt contracts around IFRS adoption. Journal of Accounting Research 53 (5): 915–963. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679x.12095.

Ball, R., A. Robin, and J.S. Wu. 2003. Incentives versus standards: Properties of accounting income in four East Asian countries. Journal of Accounting and Economics 36 (1–3): 235–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2003.10.003.

Barth, M.E., W.R. Landsman, and M.H. Lang. 2008. International accounting standards and accounting quality. Journal of Accounting Research 46 (3): 467–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679x.2008.00287.x.

Brochet, F., A.D. Jagolinzer, and E.J. Riedl. 2013. MandatoryIFRSAdoption and financial statement comparability. Contemporary Accounting Research 30 (4): 1373–1400. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12002.

Brochet, F., P. Naranjo, and G. Yu. 2016. The capital market consequences of language barriers in the conference calls of Non-U.S. firms. The Accounting Review 91 (4): 1023–1049. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51387.

Brown, P., J. Preiato, and A. Tarca. 2014. Measuring country differences in enforcement of accounting standards: An audit and enforcement proxy. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 41 (1–2): 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12066.

Burgstahler, D.C., L. Hail, and C. Leuz. 2006. The importance of reporting incentives: Earnings management in european private and public firms. The Accounting Review 81 (5): 983–1016. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2006.81.5.983.

Bushee, B.J., I.D. Gow, and D.J. Taylor. 2018. Linguistic complexity in firm disclosures: Obfuscation or information? Journal of Accounting Research 56 (1): 85–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679x.12179.

Byard, D., Y. Li, and Y. Yu. 2011. The effect of mandatory IFRS adoption on financial analysts’ information environment. Journal of Accounting Research 49 (1): 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679x.2010.00390.x.

Cai, L., A.R. Rahman, and S.M. Courtenay. 2011. The effect of IFRS and its enforcement on earnings management: An international comparison. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1473571.

Christensen, H.B., L. Hail, and C. Leuz. 2013. Mandatory IFRS reporting and changes in enforcement. Journal of Accounting and Economics 56 (2–3): 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2013.10.007.

Chua, W.F., and S.L. Taylor. 2008. The rise and rise of IFRS: An examination of IFRS diffusion. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 27 (6): 462–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2008.09.004.

Daske, H., L. Hail, C. Leuz, and R. Verdi. 2008. Mandatory IFRS reporting around the world: Early evidence on the economic consequences. Journal of Accounting Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679x.2008.00306.x.

Daske, H., L. Hail, C. Leuz, and R. Verdi. 2013. Adopting a Label: Heterogeneity in the economic consequences around IAS/IFRS adoptions. Journal of Accounting Research 51 (3): 495–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679x.12005.

De Luca, F., and J. Prather-Kinsey. 2018. Legitimacy theory may explain the failure of global adoption of IFRS: The case of Europe and the U.S. Journal of Management and Governance 22 (3): 501–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-018-9409-9.

de Moura, A.A.F., A. Altuwaijri, and J. Gupta. 2020. Did mandatory IFRS adoption affect the cost of capital in Latin American countries? Journal of International Accounting Auditing and Taxation 38: 100301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2020.100301.

Demmer, M., P. Pronobis, and T.L. Yohn. 2019. Mandatory IFRS adoption and analyst forecast accuracy: The role of financial statement-based forecasts and analyst characteristics. Review of Accounting Studies 24 (3): 1022–1065. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-019-9481-7.

Di Fabio, C. 2018. Voluntary application of IFRS by unlisted companies: Evidence from the Italian context. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 15 (2): 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41310-018-0037-z.

DiMaggio, P.J., and W.W. Powell. 1983. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review 48 (2): 147. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101.

Doupnik, T.S., and M. Richter. 2003. Interpretation of uncertainty expressions: A cross-national study. Accounting, Organizations and Society 28: 15–35.

Evans, L. 2018. Language, translation and accounting: Towards a critical research agenda. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 31 (7): 1844–1873. https://doi.org/10.1108/aaaj-08-2017-3055.

Fan, J.P.H., and T.J. Wong. 2002. Corporate ownership structure and the informativeness of accounting earnings in East Asia. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33 (3): 401–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-4101(02)00047-2.

Felski, E. 2017. How does local adoption of IFRS for those countries that modified IFRS by design, impair comparability with countries that have not adapted IFRS? Journal of International Accounting Research 16 (3): 59–90. https://doi.org/10.2308/jiar-51807.

Florou, A., and P.F. Pope. 2012. Mandatory IFRS adoption and institutional investment decisions. The Accounting Review 87 (6): 1993–2025. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50225.

Gioia, D.A., K.G. Corley, and A.L. Hamilton. 2012. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research. Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151.

Glaum, M., P. Schmidt, D.L. Street, and S. Vogel. 2013. Compliance with IFRS 3- and IAS 36-required disclosures across 17 European countries: Company- and country-level determinants. Accounting and Business Research 43 (3): 163–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2012.711131.

Gros, M., and S. Koch. 2018. Goodwill impairment test disclosures under IAS 36: Compliance and disclosure quality, disclosure determinants, and the role of enforcement. Corporate Ownership and Control 16 (1): 145–167. https://doi.org/10.22495/cocv16i1c1art4.

Haw, I.-M., B. Hu, L.-S. Hwang, and W. Wu. 2004. Ultimate ownership, income management, and legal and extra-legal institutions. Journal of Accounting Research 42 (2): 423–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679x.2004.00144.x.

Hoque, Z. 2018. Methodological issues in accounting research, 2nd ed. London, UK: Spiramus Press.

Horton, J., G. Serafeim, and I. Serafeim. 2013. Does mandatory IFRS adoption improve the information environment? Contemporary Accounting Research 30 (1): 388–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2012.01159.x.

Houqe, M.N., T. van Zijl, K. Dunstan, and A.K.M.W. Karim. 2012. The effect of IFRS adoption and investor protection on earnings quality around the world. The International Journal of Accounting 47 (3): 333–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2012.07.003.

IASB. (2018). Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. In: IFRS Foundation.

IASB. (2019). Exposure Draft ED/2019/7 General Presentation and Disclosures. In: IFRS Foundation.

ICAEW. (2018). The effects of mandatory IFRS adoption in the EU: a review of empirical research: The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales.

IOSCO. (2002). Multilateral Memorandum of Understanding Concerning Consultation and Cooperation and The Exchange of Information. Retrieved from https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD386.pdf. Accessed March 27th, 2020.

IOSCO. (2017a). Methodology For Assessing Implementation of the IOSCO Objectives and Principles of Securities Regulation. Retrieved from https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD562.pdf Accessed March 27th, 2020.

IOSCO. (2017b). Objectives and Principles of Securities Regulation. Retrieved from https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD561.pdf. Accessed March 27th, 2020.

IOSCO. (2019). Fact Sheet. Madrid, Spain: OICU-IOSCO. Retrieved from https://www.iosco.org/about/pdf/IOSCO-Fact-Sheet.pdf Accessed March 27th, 2020.

Kempthorne, D. 2013. Governing international securities markets: IOSCO and the politics of international securities market standards. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: University of Waterloo.

Kim, J.H., and S. Lin. 2019. Accrual anomaly and mandatory adoption of IFRS: Evidence from Germany. Advances in Accounting 47: 100445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2019.100445.

Kleinman, G., B.B. Lin, and R. Bloch. 2019. Accounting enforcement in a national context: An international study. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 16 (1): 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41310-019-00056-y.

Kleinman, G., B.B. Lin, and D. Palmon. 2014. Audit quality. Journal of Accounting Auditing & Finance 29 (1): 61–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X13516127.

Kothari, S.P., and R. Lester. 2012. The role of accounting in the financial crisis: Lessons for the future. Accounting Horizons 26 (2): 335–351. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-50134.

Landsman, W.R., E.L. Maydew, and J.R. Thornock. 2012. The information content of annual earnings announcements and mandatory adoption of IFRS. Journal of Accounting and Economics 53 (1–2): 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2011.04.002.

La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. 1998. Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy 106 (6): 1113–1155. https://doi.org/10.1086/250042.

Larson, R.K. 1997. Corporate lobbying of the international accounting standards committee. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting 8 (3): 175–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-646x.00024.

Lasmin, D. 2011. Accounting standards internationalization revisit: Managing responsible diffusion. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 25: 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.555.

Leuz, C., D. Nanda, and P.D. Wysocki. 2003. Earnings management and investor protection: An international comparison. Journal of Financial Economics 69 (3): 505–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-405x(03)00121-1.