Abstract

Much of the research on organized interests concludes that lobbying has little influence on lawmaking. We argue that businesses often need only small actions from politicians in order to secure profitable outcomes in the marketplace. Case studies show how lobbyists affected the Air Cargo Deregulation Act in the 1970s, the Data Quality Act in the 2000s, and the recent Federal Trade Commission investigation of Herbalife. Hedge funds are particularly well situated to profit from small actions by lawmakers, as those political actions affect market values. As a largely unregulated sector, hedge funds are ideal for testing the idea that businesses lobby for directly profitable actions. Our time series analysis demonstrates that spending on lobbying coincides with the value of assets under management in hedge funds and with increases in the federal budget. Although the time series work cannot directly test our theory, our results do fit with the notion that businesses and financial firms treat spending on lobbying as an investment to protect their interests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In this article, we make the case that businesses and financiers frequently lobby for small actions from government actors that can ensure profitability. We argue that much of the literature on lobbying misconstrues what matters to business. If we were to assume that business lobbyists are primarily interested in walking freestanding bills into laws, then we would overlook several smaller actions that can affect a firm or investor’s profit margin. These could be nonlegislative actions like asking questions in public hearings or sending letters to regulators as well as smaller-scale legislative work like inserting minor wording changes into existing bills. Further, if we were to assume that all lobbyists from the business and finance sectors push for actions that will raise firms’ value, we would overlook strategic actions taken by short sellers who want to see an asset’s value drop. We develop a theory that lobbyists in the business and financial sectors seek small actions that can affect short-term valuation of firms and assets. Because of their emphasis on short-term profits and the fact that they are largely unregulated, hedge funds are the ideal sector for this behavior. Based on our hedge fund findings, we believe that future research regarding business and finance lobbying ought to consider the possibility that the purpose of much lobbying is for small-scale actions that have a direct profit motive as opposed to broad changes in policy or regulations.

To contrast the case we build here with existing research, careful followers of interest group scholarship could be forgiven if they downplayed concerns about business lobbying expenditures. Classic work by Bauer et al (1963) (BPD hereafter) noted that the business lobbyists they interviewed preferred taking paths of least resistance and contacting their legislative allies. Lobbyists augmented a legislator’s staff and provided small favors and assistance to the legislator’s office, but in the view of BPD there was little room for undue influence. In the interest group subfield, BPD’s work continues to resonate today. More recent efforts by Hall and Miler (2008) and Hall and Deardorff (2006) add twists to the BPD foundation. In particular, these studies show that there should be some concern due to bias emerging from who lobbies, even if lobbying serves principally to subsidize actions or provide information.

An overall bewilderment surrounding lobbying recently peaked again with the success of Baumgartner et al’s (2009) Lobbying and Policy Change. Despite rich analysis, many readers concluded, “the real outcome of most lobbying is…nothing” (Burns, 2010, p. 62). Rather than argue that lobbying is irrelevant, Baumgartner et al contend that status quo policies are nearly invincible. If the status quo is so strong, why is lobbying, despite up and down years, generally a growth industry (Baumgartner et al, 2011; Ho, 2014)? Unfortunately, we know little about the linkages between lobbying expenditures and influence. Leech argues that “political researchers have struggled to measure influence…with contradictory results [and that the] search for a definitive statement about the power of lobbyists has become the Holy Grail of interest group studies” (Leech, 2010, p. 534).

Findings from interest group scholars about lobbying spending do not square easily with laypersons’ understanding, media portrayals, or Hollywood presentations of lobbying influence. These views may be at odds due to the types of analysis conducted (Leech, 2010). While scholars often study large samples, nonacademic observers typically focus in depth on single cases. Additionally, cases selected for media scrutiny are often outliers. Differences in interpretation also could stem from different measures of success. For instance, one could focus on the final votes on legislation or the structuring of the language in legislation.

We suggest that political scientists need to do a better job at explaining lobbying expenditures before they can explain lobbying influence. Although we know that corporate lobbying expenditures have increased dramatically over the last couple of decades (Drutman, 2015), we know much less about when firms spend money in the marketplace (to design better products or expand market share) versus when they spend money on lobbying in Washington. We argue that macro-level spending on lobbying responds to businesses’ investment considerations such that businesses spend more on lobbying when they have more investments to protect (Brav et al, 2009). With a particular focus on hedge fund investments, we find evidence that investments that are susceptible to minor political actions can generate substantial spending on lobbying.1

Over the last few decades, we have learned much about businesses’ nonmarket activities. We know that regulated industries contribute more to political action committees (Grier et al, 1994) and lobby more (Brav et al, 2009). Overall, government size affects the attractiveness of political lobbying (Gray and Lowery, 1996; Tichenor and Harris, 2003), government attention to issues leads to greater lobbying on those issues (Leech et al, 2005), and lobbying expenditures are higher in firms with highly compensated CEOs (Brav et al, 2009). Campaign contributions markedly rise from individuals who become S&P 500 CEOs (Fremeth et al, 2012), and contributions from S&P 1500 top executives are affected by the firm’s sensitivity to political decisions (Gordon et al, 2007). Incumbency status as well as committee and leadership positions also affect election contributions. Finally, year after year, the amounts spent on lobbying easily overshadow the amounts spent on elections. Total lobbying expenditures are typically ten times the total expenditures on federal elections, so it is unlikely that calculated campaign contributions are followed by haphazard lobbying.

In this article, we explore a heretofore overlooked concern related to business lobbying. Since most D.C. lobbying is tied to business, separating the study of lobbying strategy from overall corporate strategy might lead one to overlook important connections between business strategies and political strategies. Failing to consider how nonmarket, lobbying strategies interact with marketplace strategies might lead one to misestimate lobbying influence and success.

In the next section, we review two case studies to explore the micro-level mechanisms undergirding business lobbying to illustrate why differing types of businesses might benefit from small requests by lobbyists. In the third section, we explore the operation of hedge funds, including hedge fund activity in Washington. The connections between hedge funds and D.C. lobbying have been explored by numerous finance scholars (Gao and Huang, N.d.), but political scientists remain largely in the dark. Because hedge funds are unregulated, we argue that these are the best place to test our theory of small requests for big gains. To wit, hedge funds do not have to split their lobbying attention between policy lobbying, regulatory lobbying, and lobbying to protect investments—instead, they can dedicate all of their attention to investment-oriented lobbying. The discussions in the second and third sections provide the theoretical underpinnings for the empirical section, which focuses on aggregate lobbying expenditures. Although aggregate annual expenditures cannot directly test our theory, it is possible to falsify our result with time series analysis. If our theory is right, aggregate lobbying expenditures should increase as hedge fund assets under management increase, controlling for overall economic health and size of the federal budget. In the conclusion, we return to the issue of lobbying influence and why our analysis of hedge funds may tell us more about business lobbying in general.

Small Ball Politics Yielding Marketplace Home Runs

Minor lobbying efforts have the potential to yield considerable marketplace benefits. Fisch (2005) details the steps Fred Smith, the founder of FedEx, took to position his fledgling company within powerful circles inside the D.C. beltway. Smith was close to Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush as well as presidential candidate John Kerry. FedEx maintained ties to every elected official from its home state of Tennessee, as well as legislators on key committees and members of the Black Caucus. Smith made sure that his small fleet of planes was available to friendly elected officials who needed a free ride back to their districts. He also encouraged his largest customers to offer similar services to legislators, thereby creating a “rent chain” (e.g., Baron, 2001). “In the case of a firm [lobbying for benefits], rents are earned not only by shareholders but also by employees, suppliers, distributors, retailers” and others associated with the firm spearheading the lobbying effort (Baron, 2001, p. 70). Smith magnified his lobbying persuasiveness by mobilizing the FedEx rent chain.

Rent chains also allowed Smith to counter claims that the Air Cargo Deregulation Act of 1977 was simply the “Federal Express Act.” With air cargo deregulation, FedEx secured 1 year of noncompetition protections in any new U.S. market it entered. An “urgent letter exception” allowed FedEx to enter the overnight delivery market, directly competing with the U.S. Postal Service. Another political win assured that FedEx trucks going to or from an airport facility were not vulnerable to the same restrictions and regulations as other truck cargo carriers. For instance, trucks with the United Parcel Service received no special dispensations. Writing about FedEx, Fisch noted “the regulatory environment is an integral part of market decisions…as well as a key factor in…growth and strategic planning” (Fisch, 2005, p. 1558). FedEx politically out-maneuvered the U.S. Postal Service and the United Parcel Service—its two major competitors. Clearly, “firm competition takes place both in the marketplace and in the political arena” (Fisch, 2005, p. 1558). The economic success of the FedEx delivery models depended on urgent letter exceptions, noncompetition protections, and more lax truck regulations. Successful lobbying created a favorable marketplace position.

Smith’s lobbying efforts for FedEx took place over several years, but sometimes a short burst of focused lobbying can have major implications. In 2001, Dr. James Tozzi—a lobbyist for pesticide, tobacco, and pharmaceutical companies—single-handedly transformed the regulatory process by adding a brief passage to a 2001 appropriations bill. The passage became known as the Data Quality Act (DQA) or the Information Quality Act. Tozzi had long sought to give the White House greater leverage over agencies and the procedures by which agencies developed regulations.

Prior to the DQA’s passage, regulatory agencies had free rein to establish their own procedures and criteria when evaluating a product’s safety. In particular, agencies were not required to meet the same scientific standards for data quality or replicability as the producers were required when initially demonstrating a product’s safety. Tozzi convinced Representative Jo Ann Emerson (R-MO) to slip a few dozen words into an appropriations bill. Congress considered the bill late in the session, and no legislators other than Emerson in the House and Richard Shelby (R-AL) in the Senate appeared to understand the DQA’s implications.

The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA, within the Office of Management and Budget in the White House) subsequently required each federal agency to draft guidelines for ensuring data quality and to submit those guidelines to OIRA for approval. The guidelines that OIRA approved for the EPA substantially reduced the type of information the EPA could use to keep products off the market, which substantially raised the costs of preventing a product’s registration or renewal. For instance, OIRA forced the EPA to develop its own, independent test for each type of harmful outcome that might lead to the denial of a product’s registration. Developing such an array of tests is a long and arduous task, and implementing the tests is time consuming and costly. Extant tests that failed to meet the new guidelines were no longer acceptable. Numerous chemical firms, including Dow Chemical, benefitted from the new guidelines and the delays in stricter regulations due to the DQA. For example, Godwin et al (2013) show how the DQA insured continued sales of atrazine, a hazardous herbicide, because the studies indicating potential harm did not meet DQA standards.2

The FedEx and DQA stories show how political successes can situate firms, allowing them to increase profits. Both, however, are case studies, and it is important to move beyond single observations. Yu and Yu (2011) looked at over 250 firms over an 8-year period, yielding a dataset with over 2000 firm-year observations. For each observation, Yu and Yu assessed lobbying expenditures by firms and fraud detection by federal agencies. Firms that lobbied were less likely to have fraud detected. Among the firms implicated with fraud, those firms that lobbied evaded detection almost 4 months longer. Fraudulent firms spent more money on lobbying than those firms not caught in fraudulent activities. Finally, firms that were caught in fraud claims spent 29 per cent more on lobbying during their periods of fraudulent activity as compared to their nonfraudulent periods. Once again, the lobbying strategy interacts with the business strategy. Business lobbying is not all about legislation; rather, business lobbying is all about market position. So strong is this connection between lobbying and business success that some investors are now considering a firm’s lobbying activity when deciding where to put their money. Specifically, MotifInvesting, Inc. offers the “Kings of K Street” portfolio, allowing investors to focus on firms that “tend to spend the most on lobbyists relative to the size of their asset bases” (see: https://www.motifinvesting.com/motifs/kings-of-k-street, accessed 2/12/15).

Lobbying Incentives for Hedge Funds

Hedge funds constitute an area of business that calls for special attention in the area of lobbying. Consider their nature: Hedge funds place large bets on individual stocks and overall market movements. Through such bets, hedge funds try to profit in both bull and bear markets. Every fund is different, but a few factors differentiate hedge funds from other financial firms. First, unlike “traditional institutional investors, hedge fund managers…do not face the regulatory or political barriers that limit the effectiveness of…other investors” (Brav et al, 2008, p. 1773). The fact that hedge funds are unregulated is a central feature for testing our theory that businesses lobby for market position. Without the need for regulatory cover or concerns about the way they are regulated, the fundamental reason hedge funds lobby is to bolster their market position and ensure profitability on their investments. Hedge funds allow us to isolate this “market position” effect without worrying about competing incentives to lobby. Second, hedge funds generally appeal to wealthy, shorter-term investors. Rather than buy and hold, hedge funds will “pump and dump” or “short and distort” to make quick gains. That is, some investments expect a firm’s value to rise (like more traditional investments), but others bank on overvaluation in hopes that market price will drop. Either way, investors wish to accelerate convergence to target asset prices. Third, hedge funds engage in “activism,” directly intervening in the operations of firms they hold or are considering for purchase (Brav et al, 2008, 2009). Hedge funds are more apt to work to alter the corporate governance of firms, engage in proxy fights, pursue lawsuits, or initiate takeover bids. In short, hedge funds place bets amid many marketplace vagaries and are willing to intervene in a firm’s governance and operation to reduce the uncertainty of their investment.

The lobbying we have discussed so far operates as insurance to increase the prospect of profit when uncertain about a firm’s financial future. FedEx and Dow Chemical may have been profitable even without their lobbying prowess, but their political successes increased the odds of economic victories. Of course, Dow Chemical had an array of products, but the sale of atrazine insured that their stable of products remained more viable. Political fates affect market valuation, and market valuation is everything for the hedge funds we consider here.

The ability to predict political and economic events can be extremely valuable, and more and more D.C.-based firms provide “political positioning” advice to businesses. These new D.C. firms mirror the services of firms predicting market movements. Of course, investors routinely search for clues related to companies’ values and market movements, but more and more New York- and D.C.-based firms also provide information regarding political positioning (Gao and Huang, N.d.). Witko (2016) explores the politics behind the increasing financialization of the U.S. economy. That is, finance, insurance, and real estate (FIRE) have grown relative to other sectors of the economy. As businesses expand their nonmarket strategies, there is also an increasing financialization of politics. In particular, hedge funds, which reject the standard buy-and-hold investment strategy, bet on short-term changes in prices. An investor who is suspicious of a company’s value, due to marketplace or political concerns, can “short” the company, promising to deliver shares at a low price at some future date. Once that contract is established, the incentives to distort the company’s value are great. If the company is truly less valuable than the market price suggests, one simply speaks truth to power. Either way, one cannot make money unless the company shares fall to an even lower price than contracted.

The Wall Street Journal and the New York Times detailed the shorting process with the story behind vitamin and supplement maker Herbalife. After a hedge fund shorted Herbalife, fund managers sought assistance on Capitol Hill, lobbying to undermine Herbalife’s market position. After being solicited by the fund manager, Senator Ed Markey (D-MA) sent letters to the Security Exchange Commission and the Federal Trade Commission asking for investigations of Herbalife’s business practices (Schmidt et al, 2014). Herbalife stock sank by 17 per cent after the public release of the letters (Germano and Kendall, 2014). Of course, Herbalife stock may have fallen anyway, or Markey might have sent the letters on his own. This is a problem that is common to lobbying studies—we do not have the opportunity to observe the counterfactual of what would have happened without lobbying. Therefore, here and in other lobbying studies, it is hard to pin down whether lobbying influences politicians. However pivotal the lobbying was in this case, it provided extra insurance for the marketplace bet.

Letters are small political actions that yield marketplace movements. Questions during legislative hearings are even more minute political gestures, costing legislators virtually nothing. Indeed, legislators seem to like to ask questions. Some questions posed by legislators are for media consumption, some are for constituents, and some are for lobbyists representing key industries. Esterling (2007) finds that campaign contributions can be linked to more detailed questions and analysis during congressional hearings. Perhaps, legislators eschew symbolic politics in favor of substance, or perhaps they ask canned questions developed by industry experts. In either event, lobbying activity spurs questions from legislators. In contrast to the passage of major legislation, a few questions or a bit of inserted language might seem trivial, but small political acts like a letter sent to a regulatory agency can move stock prices. To counter the lobbying onslaught, Herbalife hired its own lobbyists and lawyers to initiate a counterattack (Stevenson and Protess, 2015). Lobbying to protect one set of bets was countered by additional lobbying. The fact that there was lobbying on both sides of the Herbalife issue is revealing in two ways: First, Herbalife’s lobbying emerged to protect the overall valuation from the company, which illustrates that business firms in general will lobby not only in consideration of the regulatory process but also to help short-term value. Thus, our notion of small ball lobbying for profitability and market valuation potentially can emerge anywhere in the business or financial sector. Second, as the assets invested through hedge funds increase, growth in aggregate lobbying spending may come from investors themselves as well as from defensive lobbying by firms targeted as short sale investments.

Although the potential for short sales is unique to the area of hedge fund investing, the general Herbalife storyline is not unique. For his shrewd (and perhaps tone deaf) business actions, Martin Shkreli has been called the Gordon Gekko of healthcare. Shkreli, a hedge fund manager and pharmaceutical speculator, bought the rights to a drug treatment that he then repriced at a figure 5445 per cent higher than its original price (Johnson, 2015; Shen, 2015). Shkreli was known in D.C. for lobbying the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regarding at least one other drug—Afreeza. Shkreli asked the FDA to reject Afreeza approval after he had shorted MannKind, the manufacturer of Afreeza, in his investments. Hence, he was well positioned to gain if the FDA rejected Afreeza. This story of lobbying in order to damage a business and profit from doing so is distinct to potential investment patterns of hedge funds. Because it is so much easier to destroy than create, the incentives for small ball lobbying are strong in areas with a lot of hedge fund investment.

The practice of lobbying to insure short bets does not crowd out all other types of lobbying. The traditional story of lobbying to raise the value of an investment and subsequently profit still occurs among hedge fund investors. For example, while Martin Shkreli may have profited early on by negative lobbying against MannKind, he found himself in a different situation after he acquired the rights to the drug Daraprim and raised its price by 5445 per cent. Shkreli began to face bipartisan pressure in Washington, with calls in Congress to subpoena his records (Shen, 2015). In response to this pressure, Shkreli hired four lobbyists to counteract this pressure, perhaps with the knowledge that federal investigations can be deflected by lobbying (Yu and Yu, 2011).

As another example, several hedge fund investors who bought $4.5 billion of Puerto Rico government bonds have worked hard to see budgetary strength and continued debt financing in the commonwealth (Corkery, 2014). At the time of the investment, the bonds appeared to be seriously undervalued, so the investors would do well if their market value rose. Some investment firms sued to guarantee that past electrical authority bonds would still be honored. Further, hedge fund managers have hosted major fundraisers for 2016 gubernatorial candidate Pedro Pierluisi, presumably in hopes of later access. Thus, a major lobbying effort emerged to shore up bets related to bond investing.

Hedge funds follow the political marketplace, and the Herbalife and Shkreli examples illustrate how intervention in political affairs can affect a firm’s fate. Leveraged money requires new bets, or new actions, to cover old bets. Some of those actions entail intervening in corporate governance, and some of those actions entail Washington lobbying.

Empirical Tests

We now explore lobbying expenditures at the most aggregated level to assess how total annual lobbying expenditures can be modeled by the overall strength of the economy, the size of the federal budget, and the amount of money invested in hedge funds. While our causal mechanism of how hedge fund investment can produce additional lobbying cannot be isolated in such an aggregate-level analysis, our results suggest how important these dynamics are if our theory is right. Our outcome variable is the change in aggregate lobbying expenditures at the federal level, which has been publicly available since the 1996 Lobby Disclosure Act. We use three input variables. The change in the assets under management (AUM) in hedge funds is our primary predictor of interest. We predict a positive effect. Hedge funds maintain short time horizons and bet on the positive and negative movements in stocks. Lobbying is a way to insure marketplace bets, and the demand for lobbying increases as there are more investments to protect. The insurance literature notes that people insure against losses when they have more at risk and that people tend to overinsure against large losses and underinsure against smaller losses. Lobbying—as insurance—will be most attractive to those who have most at risk. Of course, financial resources are important for lobbying efforts, but the insurance literature suggests that mentalities change as more is at stake. One way to contextualize our model is to consider where a firm spends its marginal dollar—on new investments or Washington lobbying to protect existing investments.

Based on past research, we also need to account for several control variables. For this reason, change in the federal budget is our second input variable. Past research indicates that as the size and scope of government increase, the resources that organized interests would like to lobby for increase. Therefore, we expect a higher level of lobbying spending when federal outlays increase (Gray and Lowery, 1996; Leech et al, 2005). Our third predictor variable is change in GDP. Generally, lobbying expenditures and the national gross domestic product (GDP) move in opposite directions (Brav et al, 2009). When the economy grows, firms focus on marketplace expansion, and there is less demand for lobbying. When the economy contracts, firms focus on ways to protect themselves from losses. Some protections—say from foreign competitors or costly regulations—can only be secured from the government. As the economy contracts, firms try to position themselves politically so that they can survive economically.3

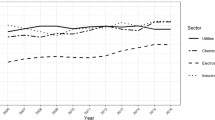

To illustrate our complete time series, Figure 1 shows line plots for lobbying expenditures (in billions), hedge fund AUM (in billions), GDP (in trillions), and the federal budget (in trillions). All of these quantities are in chained 2009 dollars to adjust for inflation. The horizontal axis in each panel represents year, and the vertical axis represents the value of the outcome. To account for the upward trend in each series, we analyze the differenced series. In our regression model, change in lobbying expenditures is the outcome variable, and the predictors are change in hedge fund assets under management, change in the federal budget, change in GDP, and an indicator for the 2008 recession. We estimate this as a Bayesian model.4

Our estimated regression coefficients for change in hedge fund investments and change in the federal budget are shown in Figure 2 as density plots from MCMC estimation. Although an important control, we omit the posterior plot for change in GDP as a robust effect did not emerge. Our model indicates that there is a 0.961 probability that the partial effect of change in hedge fund investments is positive, and the posterior mean of this coefficient is 0.0004. The model also indicates that there is a 0.966 probability that the partial effect of change in federal outlays is positive, and the posterior mean is 0.5159. In short, for each coefficient there is over a 96 per cent probability of a positive effect, so these two robust results conform to our hypotheses. Again, at an aggregate level many unobserved factors could be underlying this empirical association besides our theory that hedge fund investment spurs more business lobbying. That said, our results imply that this investment effect could be important for understanding lobbying. Substantively, the posterior mean for the federal budget effect implies that a $1 trillion increase in the federal budget would project a $516 million increase in lobbying, on average and all else being equal. Meanwhile, the hedge fund investment posterior mean implies that a $1 billion increase in hedge fund spending leads to another $445,000 in lobbying expenditures on average and ceteris paribus.

How much is a billion dollars for the hedge fund industry? In 2015, well over $2 trillion was invested in hedge funds.5 A $1 billion rise represents 0.04 per cent of the total amount invested. Meanwhile, the $445,000 response in lobbying expenditures we project equates to 0.02 per cent of lobbying spending in 2015. Together, the potential scale of this effect of hedge fund investments on lobbying is enormous. To illustrate, a single hedge fund’s bet on Herbalife was $1 billion (Schmidt et al, 2014). Seeing the lobbying action the Herbalife investment generated illustrates just how easily investments can prompt lobbying efforts. To provide more context for this effect, a $1 billion increase in the federal budget would, in expectation, induce a $516,000 growth in lobbying expenditures. So if our preliminary finding from studying aggregate-level lobbying expenditures is right, the $445,000 increase in lobbying spending we estimate for an extra $1 billion in hedge fund investments creates a notable effect.

Implications

Our findings are too highly aggregated to be definitive, but they are consistent with behavior to insure marketplace bets: We believe that the relative value of investing in lobbying for political support for investments is affected by the total assets under management in hedge funds. Our work fits with past work that identifies lobbying as an investment (Gordon et al, 2007; Snyder, 1990). A campaign contribution might be a lagniappe (Ansolabehere et al, 2003; Milyo et al, 2000), but lobbying spending is not.

A key implication for political scientists is that we may need to rethink how lobbying can be influential. Past studies primarily followed bill passage, which is undoubtedly important. But a tight focus on bill passage limits our attention given to other important areas. Lobbyists do not always pursue the enactment of original legislation, often preferring something simpler. Having a senator take a less dramatic action—send a letter to a regulatory agency, insert or delete a few words from a bill, or pose tough questions at hearings—can still move stock prices. In cases of short sales, incentives can exist either to bolster businesses’ value or to undermine firms’ value. Thus, we could have been overlooking much of what motivates businesses when they lobby, both because the scale of nonlegislative actions could be small and because in some instances a lobbyist wants to see a firm’s value decrease. Whereas Baumgartner et al found little evidence of broad-based policy changes, small efforts by legislators can create large gains or devastating losses for affected businesses.

Are there any limits on these sorts of activities? The STOCK Act of 2012 (Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge) sought to limit—if not curtail—the use of confidential information from congressional sources when making financial trades. The distinction between hiring a lobbyist for confidential congressional information and hiring a lobbyist for general Washington advice is seldom clear. In contrast to Gao and Huang (N.d.), who focus tightly on the purchase of D.C.-based information that the STOCK Act sought to curtail, we envision hedge funds seeking influence and favors in addition to information. The STOCK Act focused on the use of insider congressional information, not on old-fashioned lobbying for favors. Assessments of major policy change suggest that there is little lobbying impact, but our case studies and empirical analysis corroborate investment-oriented spending by businesses and financiers, and Washington lobbying is dominated by these two sectors. No one can definitively prove cause and effect, but our hypothesized micro-level mechanisms are consistent with and corroborate our aggregate-level findings. Furthermore, Wall Street is unforgiving; it expects returns on any investment, including lobbying.

A broader implication of our work is that lobbying serves to protect monied interests throughout the business and financial sectors. Many scholars have argued that democratic tendencies will limit the unbridled exuberance of market winners because inequalities in the market are balanced by political power (e.g., Meltzer and Richard, 1981; Smith, 2000). These assessments contrast with Lindlom’s (1977) “privileged position of business.” More recently, Hacker and Pierson (2010) note various policies that create a strong backstop bolstering winners, thereby allowing more wins and greater political leverage, and Gilens (2012) shows that policy outputs reflect the concerns of the wealthiest Americans. The policy biases produced by wealthy interests push risky financial policies for personal gain (McCarty et al, 2013). Echoing Schattschneider’s (1960) critique of the Pollyannaish pluralists, there is an upper-class ring to the chorus of American politics. As investment vehicles continue changing, hedge funds might lose their oversized role in finance and lobbying. Regardless, there will be Wall Street actors who seek to insure their bets, and Washington often provides the best insurance.

Notes

-

1

Gao and Huang (N.d.) argue that hedge funds are most apt to buy political information from lobbyists when they hold investments in firms that are sensitive to political decisions. That is, Gao and Haung focus on how political information can allow hedge fund managers to buy and sell investments. In contrast, we suggest that information and small political actions can affect investment values.

-

2

Atrazine is a popular herbicide used throughout the midwest. It deteriorates quickly in soil, but persists in water environments. Atrazine potentially damages humans’ endocrine system, and it is linked to hormone disruptions in amphibians. The EPA still allows its use.

-

3

Relatedly, we also include an indicator variable for the year 2008, marking the start of the biggest economic downturn since the Great Depression.

-

4

Additional model details, including the full Bayesian model specification and a full regression table, are in the online appendix.

-

5

Nominally, $2.8 trillion was invested. In inflation-adjusted 2009 dollars, which is what our model uses, this translates to $2.5 trillion.

References

Ansolabehere, S.D., de Figueiredo, J.M. and Snyder, J.M. (2003) Why is there so little money in U.S. politics? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(1), 105–130.

Baron, D.P. (2001) Theories of strategic nonmarket participation: Majority-rule and executive institutions. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 10(1), 47–89.

Bauer, R.A., de Sola Pool, I. and Dexter, L.A. (1963) American Business and Public Policy: The Politics of Foreign Trade. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Baumgartner, F.R., Berry, J.M., Hojnacki, M., Kimball, D.C. and Leech, B.L. (2009) Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baumgartner, F., Gray, V. and Lowery, D. (2011) Policy attention in state and nation: Is anyone listening to the laboratories of democracy? Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 41(2), 286–310.

Brav, A., Jiang, W. and Kim, H. (2009) Hedge fund activism: A review. Foundations and Trends in Finance, 4(3), 185–246.

Brav, A., Jiang, W., Partnoy, F. and Thomas, R. (2008) Hedge fund activism, corporate governance, and firm performance. Journal of Finance, 63(4), 1729–1775.

Burns, M. (2010) K Street and the Status Quo. Miller-McCune Sept–Oct: 62–67.

Corkery, M. (2014) Puerto Rico Finds it has New Friends in Hedge Funds. New York Times, 12 September 2014. 13 September 2014, nytimes.com.

Drutman, L. (2015) The Business of America is Lobbying: How Corporations became Politicized and Politics Became Corporate. New York: Oxford University Press.

Esterling, K.M. (2007) Buying expertise: Campaign contributions and attention to policy analysis in congressional committees. American Political Science Review, 101(1), 93–109.

Fisch, J.E. (2005) How do corporations play politics? The FedEx story. Vanderbilt Law Review, 58, 1495–1570.

Fremeth, A.R., Richter B.K. and Schaufele, B. (2012) Campaign Contributions over CEOs’ Careers. University of Ottowa Department of Economics Working Papers Series, Number 1203E.

Gao, M. and Huang, J. (N.d.) Capitalizing on capitol hill: Informed trading by hedge fund managers. Journal of Financial Economics (Forthcoming).

Germano, S. and Kendall, B. (2014) Federal trade commission starts Herbalife probe. Wall Street Journal, 12 March 2014. 8 February 2015, wsj.com.

Gilens, M. (2012) Affluence & Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press and the Russell Sage Foundation.

Godwin, K., Ainsworth, S.H. and Godwin, E. (2013) Lobbying and Policymaking: The Public Pursuit of Private Interests. Washington: CQ Press.

Gordon, S.C., Hafer, C. and Landa, D. (2007) Consumption or investment: On motivations for political giving. Journal of Politics, 69(4), 1057–1072.

Gray, V. and Lowery, D. (1996) The Population Ecology of Interest Representation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Grier, K.B., Munger, M.C. and Roberts, B.E. (1994) The determinants of industry political activity, 1978-1986. American Political Science Review, 88(4), 911–926.

Hacker, J.S. and Pierson, P. (2010) Winner-Take-All Politics. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Hall, R.L. and Deardorff, A.Z. (2006) Lobbying as legislative subsidy. American Political Science Review, 100(1), 69–84.

Hall, R.L. and Miler, K.C. (2008) What happens after the alarm? Interest group subsidies to legislative overseers. Journal of Politics, 70(4), 990–1005.

Ho, C. (2014) Lobby Revenue Down for Third Year in a Row. Washington Post, 22 January 2014. 8 February 2015, washingtonpost.com.

Johnson, C.Y. (2015) The drug industry wants us to think Martin Shkreli is a Rogue CEO. He Isn’t. Washington Post, 25 September 2015. 9 December 2015, washingtonpost.com.

Leech, B.L. (2010) Lobbying and influence. In J. M. Berry & S. Maisel (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of American Political Parties and Interest Groups. New York: Oxford University Press.

Leech, B.L., Baumgartner, F.R., La Pira, T.M. and Semanko, N.A. (2005) Drawing lobbyists to Washington: Government activity and the demand for advocacy. Political Research Quarterly, 58(1), 19–30.

Lindlom, C.E. (1977) Politics and Markets. New York: Basic Books.

McCarty, N., Poole, K.T. and Rosenthal, H. (2013) Political Bubbles: Financial Crises and the Failure of American Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Meltzer, A.H. and Richard, S.F. (1981) A rational theory of the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 914–927.

Milyo, J., Primo, D. and Groseclose, T. (2000) Corporate PAC campaign contributions in perspective. Business and Politics, 2(1), 75–88.

Schattschneider, E.E. (1960) The Semi-Sovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Schmidt, M., Lipton, E. and Stevenson, A. (2014) After Big Bet, Hedge Fund Pulls the Levers of Power. New York Times, 9 Mar. 2014. 8 Feb. 2015, nytimes.com.

Shen, L. (2015) The Former Hedge Funder Who Jacked Up a Drug’s Price by 5,000% Has Hired Lobbyists. Business Insider, 2 October 2015. 9 December 2015, businessinsider.com.

Smith, M.A. (2000) American Business and Political Power: Public Opinion, Elections, and Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Snyder, J.M, Jr. (1990) Campaign contributions as investments: The U.S. house of representatives, 1980-1986. Journal of Political Economy, 98, 1195–1227.

Stevenson, A. and Protess, B. (2015) Herbalife Steps Up Lobbying to Counter Ackman’s Attacks.”New York Times, 2 June 2015. 2 June 2015, nytimes.com.

Tichenor, D.J. and Harris, R.A. (2003) Organized interests and American political development. Political Science Quarterly, 117(4), 587–612.

Witko, C. (2016) The politics of financialization in the United States, 1949-2005. British Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 349–370.

Yu, F. and Yu, X. (2011) Corporate lobbying and fraud detection. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 46(6), 1865–1891.

Acknowledgments

For helpful assistance, including data sharing, we thank Sol Waksman, Alon Brav, and Chris Witko. Complete replication information can be found at our Dataverse page http://dx.doi.org/10.7910/DVN/29171.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ainsworth, S.H., Monogan, J.E. Insuring hedged bets with lobbying. Int Groups Adv 5, 263–277 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-016-0005-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-016-0005-6