Abstract

The internationalization of China’s equity markets started in the early 2000s but accelerated after 2012, when Chinese firms’ shares listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen gradually became available to international investors. This paper documents the effects of the post-2012 internationalization events by comparing the evolution of equity financing and investment activities for (i) domestic listed firms relative to firms that already had access to international investors and (ii) domestic listed firms that were directly connected to international markets relative to those that were not. The paper shows significant increases in financial and investment activities for domestic listed firms and connected firms, with sizable aggregate effects. The evidence also suggests that the rise in firms’ equity issuances was primarily and initially financed by domestic investors. Foreign ownership of Chinese firms increased once the locally issued shares became part of the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) Emerging Markets Index in 2018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

China’s integration into global financial markets is important for both China and the world economy (Cerutti and Obstfeld 2019). Before China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, international investors’ access to Chinese stocks was severely restricted.Footnote 1 After China became a WTO member, it established a Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) program that partially allowed selected institutional investors to purchase shares issued in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets.

In the post-2012 period, the internationalization process accelerated significantly as Chinese authorities steadily eased restrictions that prevented international institutional and retail investors from buying shares of Chinese firms listed in domestic markets (the so-called A shares). In 2013, the authorities relaxed restrictions on foreign institutional ownership of domestic firms. In 2014 and 2016, the Stock Connect program gave international institutional and retail investors direct access to a subset of stocks listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen, respectively, through the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Since 2018, these connected stocks have been gradually incorporated into the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) Emerging Markets Index.

This paper studies how opening mainland China’s stock markets to foreign investors has affected Chinese firms’ equity financing and investment activities. We analyze the performance of firms between 2000 and 2020, focusing on the post-2012 internationalization period, given the number and relevance of events in those years. We conduct difference-in-differences estimations to compare firms targeted by the internationalization events with non-targeted firms. We also analyze the role of domestic and international investors in financing Chinese firms.

We construct a rich panel dataset of publicly listed firms residing and operating in mainland China, combining transaction-level equity issuances with balance sheet and income statement information. We compare the performance of different groups of firms based on their exposure to the internationalization events. First, the foreign listed group consists of firms listed outside mainland China, whose stocks were available to international investors for the entire sample period. Second, the domestic listed group includes firms listed only in mainland China, whose stocks became available to international investors through the different internationalization events. Third, within the domestic listed group, the connected group is the subgroup of firms whose stocks became accessible to international investors through the Stock Connect program and the incorporation into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Fourth, the unconnected group refers to the remaining firms in the domestic listed group.

We systematically compare (i) domestic listed with foreign listed firms and (ii) connected with unconnected domestic listed firms. We emphasize the comparison between connected and unconnected firms because it is less subject to omitted variable bias and other identification concerns. The panel dataset enables us to examine yearly differences between treatment and control groups over a long period.

We find that firms targeted by the post-2012 internationalization events substantially increased their equity issuance and investment activities relative to non-targeted firms. Domestic and foreign listed firms followed similar equity issuance patterns during 2000–2013. But since the implementation of the Stock Connect in 2014, domestic listed firms, especially the connected ones, increased their equity issuances relative to the other firms. The difference in equity issuances between connected and unconnected firms peaked during 2015–2017 and remained significant during the 2018–2020 MSCI incorporation process. By 2020, the cumulative amount of equity raised (over initial assets) was 51 percentage points higher for connected firms than for unconnected firms with similar initial characteristics. Connected firms also increased their capital expenditures, acquisitions of other firms, research and development (R&D) expenditures, and short-term investments (including cash) relative to unconnected firms during 2014–2020. We show that the rise in investments can be directly linked to the surge in equity financing associated with the internationalization events.

We take a first step toward understanding the aggregate impact of the post-2012 internationalization events in China. Around 28 percent of all equity raised by domestic listed firms and 20 percent of all equity raised in China between 2013 and 2020 could be associated with these events. The estimates of the impact on market capitalization are of similar magnitudes. For investment activities, these events could be associated with about 10 percent of capital expenditures, 12 percent of acquisitions, 24 percent of R&D expenditures, and nearly a quarter of cash and short-term investments by all domestic listed firms in China between 2013 and 2020.Footnote 2

To study the behavior of international investors during the internationalization process, we analyze foreign equity inflows into China, foreign equity holdings of Chinese stocks, and foreign ownership ratios of domestic listed firms. We find that foreign equity inflows were substantially smaller than domestic equity proceeds raised during 2015–2017. This suggests that domestic investors bought most of the new shares issued during those years, providing “bridge financing” until international investors entered Chinese markets. The most notable increase in foreign participation occurred during the 2018–2020 MSCI incorporation process.

Our paper speaks to an established literature that studies the internationalization of equity markets in emerging economies and its impact on domestic firms. Several studies focus on equity prices and argue that improved international risk sharing of domestic stocks effectively reduces firms’ cost of capital (Stulz 1999; Henry 2000; Chari and Henry 2004, 2008). The evidence on the real impact is more mixed. Some argue that stock market liberalizations can boost investment and growth (Bekaert et al. 2001, 2005; Mitton 2006; Quinn and Toyoda, 2008; Gupta and Yuan 2009). Others show that the internationalization of domestic equity markets does not necessarily have real effects (Edison et al. 2004; Prasad et al. 2007; Kose et al. 2009; Mclean et al. 2022).Footnote 3 The mixed results could reflect the difficulties in isolating the effects of liberalization policies from those of other concurrent reforms, especially with aggregate data.

We contribute to this literature in two ways. First, little evidence exists on the impact of internationalization events on firms’ equity issuance activity. We fill this gap by documenting the evidence from China. Second, the literature on the economic implications of liberalizing equity markets is mainly based on cross-country studies. We contribute to this literature by conducting a within-country study on the largest emerging economy where subgroups of firms were integrated at different times.

Our paper is also related to a growing literature that studies the integration of China into global financial markets. Some papers cover the early periods of liberalization, studying the entrance of foreign institutional investors, the lifting of foreign exchange restrictions, and the extent of financial integration (Lane and Schmukler 2007; Chiang et al. 2008; Huang and Zhu 2015; Yao et al. 2018). One central message from this literature is that China has gradually opened its financial system by progressively allowing selected foreign investors to invest within China. Other papers focus on the post-2012 internationalization of Chinese equity markets. They show that equity prices and capital expenditures increased following the connection between the stock markets in mainland China and Hong Kong (Bai and Chow 2017; Chan and Kwok 2017; Li et al. 2020; Ma et al. 2021; Peng et al. 2021; Wang 2021; Chen et al. 2022). These studies typically focused on narrow time windows around the 2014 implementation of the Stock Connect program in Shanghai.

Our paper complements this literature by providing a more complete characterization of the internationalization of Chinese equity markets and the associated effects. We systematically investigate the impact of different internationalization events on domestic firms during 2000–2020. We focus on the implications for firms’ equity issuances rather than prices and link them to different types of investments.Footnote 4 In addition, we provide evidence on how the firm-level changes translated into aggregate effects and how international investors reacted to the various internationalization events.

Other papers study the evolution of foreign ownership during the internationalization of Chinese equity markets. They document higher foreign participation in China’s stock markets around the 2014 implementation of the Stock Connect program (Cerutti and Obstfeld 2019) and an increase in foreign equity inflows into China around the 2018 incorporation of A shares into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index (Antonelli et al. 2022).Footnote 5 Using firm-level data covering a more extended period and different measures of foreign equity investment, we show that the most important event for the increase in foreign participation in Chinese stocks was their incorporation into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. This is consistent with the notion that international investors closely follow equity benchmark indexes in choosing their investment strategies (Raddatz et al. 2017).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the main internationalization events in China. Section 3 describes our data and empirical strategy. Section 4 reports our results. Section 5 concludes.

2 The Internationalization Events in China

Chinese equity markets were established in the early 1990s with the opening of the Shanghai “SSE” and Shenzhen “SZSE” stock exchanges. These equity markets remained largely closed to international investors until the early 2000s but have experienced significant opening and growth since then. This section discusses key events and aggregate trends related to the internationalization of Chinese equity markets, focusing on the institutional investor programs, the Stock Connect program, and the incorporation of Chinese stocks into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.Footnote 6

2.1 The Start of the Internationalization Process: The Institutional Investor Programs

The internationalization process started in 2002 when China allowed specific foreign institutional investors to invest in China through the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) program. Foreign institutions that qualified for this program could buy stocks listed in China’s domestic markets (SSE and SZSE). There were many restrictions for foreign institutions to access this program, such as strict quota restrictions, both at the country level (maximum quota limits for each country) and at the institutional level (maximum quota limits per investment firm). There were also restrictions based on the investors’ characteristics, such as minimum years of experience and market capitalization requirements. The licensed investors for the QFII included: asset management companies, insurance companies, securities companies, pension funds, banks, and other institutional investors.

In 2011, China launched the Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII) program. While QFII quota holders had to convert foreign currency into renminbi to invest in Chinese securities, RQFII quota holders could invest in China’s domestic markets with offshore renminbi accounts. Initially, only Hong Kong subsidiaries of Chinese fund management companies qualified for the RQFII program. In 2013, the QFII and RQFII programs experienced material expansions. For example, the total investment quota allowed through the QFII almost doubled from previous years (from 80 to 150 billion US dollars). China also granted RQFII investment quotas to institutions in Singapore and the UK.

2.2 The Stock Connect Program

The opening of China’s equity markets to foreign investors substantially widened in 2014. Before that year, the QFII and the RQFII were the only schemes through which foreign institutions could buy stocks listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen (A shares).

In April 2014, the Stock Connect program was officially approved. The Shanghai (Shenzhen) and Hong Kong stock markets were connected in November 2014 (December 2016). Under this program, international investors of any type (institutional and retail) can invest in eligible stocks listed in mainland China through the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.Footnote 7 More than half of the Chinese stocks listed in domestic equity markets were connected through this program. The connected stocks primarily included the constituent stocks of local benchmark indexes (SSE 180 Index, SSE 380 Index, and SZSE Component Index) and stocks cross-listed in the domestic (Shanghai or Shenzhen) and Hong Kong markets.Footnote 8 The program allowed foreign institutions to circumvent most of the previous restrictions linked to the QFII and RQFII schemes.Footnote 9

2.3 The Incorporation of Chinese Domestic Stocks into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index

In June 2013, MSCI released the first official document discussing the potential inclusion of A shares in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.Footnote 10 Until then, the only Chinese stocks tracked by MSCI were those of foreign listed firms.

Following several consultations between 2014 and 2017, MSCI announced in June 2017 the inclusion of A shares in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Only A shares eligible through the Stock Connect program were added to the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Large capitalization (Large Cap) shares were included with an inclusion factor of 5 percent in 2018.Footnote 11 The inclusion factor subsequently increased to 10 percent in May 2019, 15 percent in August 2019, and 20 percent in November 2019.Footnote 12 The addition of Mid Cap A shares was announced in 2017 and implemented in 2019.

2.4 Aggregate Trends

The internationalization of equity markets in China coincided with rapid growth in equity market capitalization. The market capitalization of domestic listed firms grew especially fast during the implementation of the Stock Connect program (2014–2016) and the MSCI incorporation (2018–2020). The Chinese equity market capitalization grew faster than GDP and the capitalization in Hong Kong and Singapore (Fig. 1, Panel A).Footnote 13 By 2014, China’s market capitalization had become the second largest in the world after that of the USA.

Aggregate equity market indicators. This figure shows aggregate equity indicators for mainland China; Hong Kong; and Singapore. Panel A shows the total equity market capitalization of domestic listed firms in each economy. Panel B shows price indexes of domestic listed stocks (2012=1). The mainland China equity index is the average between the Shanghai and Shenzhen composite equity indexes. The Hong Kong index is the Hang Seng Index. The Singapore index is the Straits Times Index. Panel C shows the aggregate equity issuance activity (excluding initial public offerings) of publicly listed firms with residence in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Values are expressed in billions of 2011 US dollars (USD). The shaded areas capture the implementation of the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor programs (QFII and RQFII), the implementation of the Stock Connect program, and the incorporation of domestic listed stocks from China into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. RHS: right-hand side. Sources: World Bank and Refinitiv

The expansion of market capitalization coincided with increases in equity prices and issuances. The price index in China rose rapidly since 2014, significantly diverging from the indices in Hong Kong and Singapore, despite sharing similar trends up to 2013 (Fig. 1, Panel B). Moreover, the aggregate amount of equity raised in mainland China doubled between 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 (Fig. 1, Panel C). While mainland China and Hong Kong shared similar equity issuance trends before 2014, a clear divergence has occurred since then. The pattern of equity issuances suggests a significant impact of internationalization on domestic equity financing that has yet to be explored in the literature. We fill this gap by using a rich dataset on equity issuance activity.

3 Data and Methodology

3.1 Data

We merge transaction-level data on equity issuances with balance sheet data of domestic and foreign listed Chinese firms with residence and major business operations in mainland China. The transaction-level data come from Refinitiv’s Securities Data Corporation (SDC) Platinum, which provides detailed transaction-level information on new equity issuances during 1990–2020. The balance sheet and income statement data come from Worldscope. Lastly, we augment our merged dataset with firm-level data on ownership structure from Wind.Footnote 14

We work with a balanced sample, requiring firms to be listed in 2013. Therefore, we exclude firms that had an initial public offering (IPO) after 2013 and focus on secondary equity offerings (SEOs) of already publicly listed firms. SEOs explain most Chinese equity issuance growth since 2013 (Appendix Fig. 8). Moreover, SEOs allow us to compare firm performance before and after the capital raising activity, which we cannot do with IPOs as there is no issuance or balance sheet information for a firm before its IPO. 2013 also marks the beginning of most internationalization announcements and events we analyze.

We define domestic listed firms as those that had only issued equity in the Shanghai or Shenzhen stock exchanges (A shares) up to 2013. We define foreign listed firms as those that issued equity (at least once) in the Hong Kong Stock Exchange or other foreign stock exchanges (such as New York) before 2013.Footnote 15 Therefore, the foreign listed group includes Chinese firms that only issued equity in international markets and dual listed firms issuing equity in domestic and international markets.Footnote 16

Within domestic listed firms, we distinguish between connected and unconnected firms using information from the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Connected firms are domestic listed firms whose A shares became available to international investors through the Stock Connect program and were added to the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Unconnected firms are the remaining domestic listed firms that did not gain direct access to foreign capital through these events.Footnote 17

Our sample comprises 2,017 domestic listed firms (82 percent) and 438 foreign listed firms (18 percent). Among domestic listed firms, there are 1,289 connected firms and 728 unconnected firms (Table 1, Panel A). Between 2000 and 2012, foreign listed firms accounted for about 70 percent of the total equity raised by all publicly listed firms (Table 1, Panel B). This pattern reversed during 2013–2020 when domestic listed firms accounted for more than 70 percent of the equity raised. Connected firms accounted for about 86 percent of the equity raised by domestic firms.

3.2 Empirical Strategy

The baseline empirical framework is a difference-in-differences approach that exploits firm heterogeneity in their exposure to the equity market internationalization process. We use the following specification throughout the analysis:

where \(y_{it}\) is our dependent variable of interest (alternatively, issuance activity and balance-sheet variables capturing investment) for firm \(i\) at time \(t\). \(D_{i}^{Treated}\) is a dummy variable that equals one if firm \(i\) is in the treatment group (i.e., exposed to the internationalization process) and zero otherwise. We include a set of year dummies \(time_{t}\) and their interactions with the treatment dummy. Therefore, \(\gamma_{t}\) measures the change in each variable for the control group in year t relative to 2012, while \(\beta_{t}\) measures the differential effect for the treatment group in year t relative to 2012. Industry fixed effects are denoted by \(\alpha_{j}\).Footnote 18\(\sigma\) is a constant. Since 2013 marks the beginning of most of the internationalization events, we set 2012 as the comparison year in our analysis and normalize each variable of interest by the firm’s total assets in 2012.Footnote 19

We first distinguish between Chinese firms listed in international markets (foreign listed firms) and those listed in mainland China’s capital markets (domestic listed firms). In this case, \(D_{i}^{ Treated}\) is a dummy variable that equals one for domestic listed firms and zero for foreign listed firms. We consider three variants of the control group: all foreign listed firms, foreign listed excluding those with A shares (dual listed), and foreign listed excluding dual listed and those listed in Hong Kong. We analyze the 2000–2020 period to study equity issuance patterns around the establishment of the QFII and RQFII programs, the Stock Connect implementation, and the MSCI incorporation, which targeted domestic listed firms. Finding statistically significant changes in the equity issuance activity of domestic listed firms relative to foreign listed firms would suggest an impact of the internationalization events.

We conduct a second difference-in-differences analysis to remove potentially confounding effects from contemporary reforms or financial shocks affecting domestic capital markets, such as the rise in shadow banking around 2010–2012 (Acharya et al. 2020b; Chen et al. 2020). We focus on domestic listed companies, distinguishing between connected and unconnected ones. Here, \(D_{i}^{ Treated}\) is a dummy variable that equals one for connected firms and zero for unconnected firms. We focus on the 2007–2020 period to study equity issuance patterns around the Stock Connect and the MSCI incorporation, which targeted connected firms.Footnote 20

Still, the selection of firms is not random, and the connected treatment group could be fundamentally different from the unconnected control group. Indeed, on average connected and unconnected firms differed in some important financial and real variables in 2010–2012 (Table 2, Panel B). The most significant differences between connected and unconnected firms are in size-related variables, such as total assets, market capitalization, and total debt.Footnote 21 We attempt to address endogeneity concerns related to the systematic differences between connected and unconnected groups in two ways.

First, we analyze differences in the long-term trends in our variables of interest (issuance and investment activities) between the treatment and control groups. If the two groups had similar trends before the internationalization events, one could argue that the unobservable variables should not differentially affect these firms during the post-internationalization period. To this end, we use a yearly difference-in-differences specification and compare yearly differentials instead of analyzing two distinct periods. Second, we run propensity score matching (PSM) regressions to obtain a subsample of connected and unconnected firms with similar characteristics before internationalization (Chan and Kwok 2017; Ma et al. 2021). We estimate a logit model to predict the probability of being connected based on the broad set of variables from Table 2. The estimated model matches firms in the treatment group to their nearest neighbors in the control group based on similar predicted probabilities of being connected.Footnote 22 After the matching, the ex-ante differences in firm characteristics between connected and unconnected firms in the PSM sample disappear or become significantly smaller (Table 2, Panel C).Footnote 23

4 Results

Consistent with the aggregate data, our firm-level evidence shows that the post-2012 internationalization events coincided with a surge in firms’ equity issuance activity. The growth in equity issuances was driven by domestic listed (connected) firms and accelerated since 2014. By 2016, the aggregate amount of equity raised by connected firms was more than five times the amount raised in 2012. Although equity issuances declined between 2016 and 2017, the overall issuance level was still historically high in 2017 before declining in 2018–2020 (Fig. 2, Panel A).Footnote 24

Equity issuance activity by different types of listed firms. This figure shows trends in equity issuance activity for different groups of publicly listed firms with residence and operations in mainland China. Panel A shows the aggregate amount of equity raised per type of firm. Values are expressed in billions of 2011 US dollars (USD). Panel B shows the average amount of equity raised per type of firm and year over 2012 assets. Panel C shows the average cumulative equity raised per type of firm and year over 2012 assets. The shaded areas capture the implementation of the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor programs (QFII and RQFII), the implementation of the Stock Connect program, and the incorporation of domestic listed stocks into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index

We observe similar patterns when scaling the amount of equity raised per firm as a fraction of its total assets in 2012. During 2000–2012, the average amount of equity raised to assets was low and similar across firms (Fig. 2, Panel B). Equity issuances substantially grew after 2012 and started to diverge across firms since 2014. For connected firms, the average amount of equity raised to assets was ten times higher in 2014–2016 than in 2012 (about 10.5 percent versus 1 percent, respectively). Unconnected and foreign listed firms also increased their equity issuances but to a lesser extent than connected firms. By 2020, the cumulative amount of equity raised over assets was about 56 percent for connected firms and 36 percent for unconnected firms. Both started from similar levels in 2014 (Fig. 2, Panel C).

4.1 Firm Financing

4.1.1 Baseline Results

We begin our econometric analyses by examining the internationalization effect on firms’ equity issuance activity. We run our baseline difference-in-differences regression (Equation 1) to assess changes in equity issuance activity across different groups of publicly listed firms. We consider two dependent variables (\({y}_{it}\)): the amount of equity raised per firm-year and the cumulative amount raised per firm up to each year. We normalize both measures by the size of each firm (measured by total assets) in 2012.

The regression results confirm that equity issuances only started to diverge across domestic listed firms and foreign listed firms in the years following the implementation of the Stock Connect program (Table 3, Columns 1-3).Footnote 25 The difference in equity raised over assets between domestic and foreign listed firms was not statistically significant during the QFII implementation in 2002, the RQFII implementation in 2011, or the QFII/RQFII expansions in 2013. It became statistically significant in 2015, when domestic listed firms increased the equity to assets ratio by 4 percentage points (p.p.) relative to foreign listed firms. This difference increased to more than 10 p.p. in 2016. By 2020, the cumulative amount of equity raised over assets for domestic listed firms reached 50 percent, 21 p.p. higher than that for foreign listed ones (Fig. 3, Panel A).Footnote 26

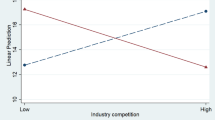

Differences in equity issuance behavior. This figure shows differences in equity issuances for different groups of publicly listed firms with residence and operations in mainland China. The figure plots the difference-in-differences (DiD) coefficients (and their 90% confidence intervals) obtained by estimating Equation (1), using the cumulative amount of equity raised over 2012 assets as the dependent variable. The DiD coefficients show, for each year, the average differences in equity raised across groups of firms (relative to the 2012 difference). Panel A compares domestic listed and foreign listed firms. Panel B compares connected and unconnected domestic listed firms. Panel C compares the propensity score matched (PSM) sample of connected and unconnected domestic listed firms. The 2012 coefficients show the differences in 2012. The shaded areas capture the implementation of the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor programs (QFII and RQFII), the implementation of the Stock Connect program, and the incorporation of domestic listed stocks into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Appendix Table 10 reports the coefficients shown in this figure

Since comparisons between foreign and domestic listed firms may be affected by confounding domestic events unrelated to internationalization, we now focus on the group of domestic listed firms. We estimate difference-in-differences regressions to compare the issuance activity of connected and unconnected domestic listed firms. We present the full and PSM sample results (Table 3, Columns 4 and 5). Both groups of firms show similar equity issuance patterns before the Stock Connect program was implemented. Since then, connected firms raised substantially more equity than unconnected firms.

Results with the full sample show that the differences between connected and unconnected firms became significant in 2015. The amount of equity raised over assets was about 4 p.p. higher for connected firms than for unconnected firms in 2015 and 6 p.p. higher in 2016. Differences between connected and unconnected firms were still significant (but smaller) during the MSCI incorporation process (2018–2020). By 2020, the cumulative amount of equity raised over assets was approximately 18 p.p. higher for connected firms than for unconnected firms, starting from similar values before 2014 (Fig. 3, Panel B).

The results with the PSM sample show that the differences between connected and unconnected firms of similar characteristics became significant in 2014 and were larger than those with the full sample. The amount of equity raised over assets was about 3 p.p. higher for connected firms than for unconnected firms in 2014, 8 p.p. higher in 2015, and 18 p.p. higher in 2016. The amount of equity raised over assets was still 7 p.p. higher for connected firms in 2017. While the differences declined further during 2018–2020, they were still significant. By 2020, the cumulative amount of equity raised over assets by connected firms was 51 p.p. higher than that of unconnected firms of similar characteristics, starting from similar values before 2014 (Fig. 3, Panel C).Footnote 27

Overall, these results suggest significant and lasting effects of the 2014–2020 internationalization process on equity issuances. Connected firms started to raise more equity (relative to unconnected firms) during the 2014–2016 Stock Connect implementation and continued to do so, but to a lower extent during the 2018–2020 MSCI incorporation. However, it is difficult to fully disentangle the importance of each event because both the Stock Connect and the MSCI events targeted the same connected firms and occurred back-to-back. Firms subject to the Stock Connect effect could have also anticipated the MSCI incorporation by raising more funds before 2018, given that the MSCI reviews about the incorporation started in 2014.

4.1.2 Firm Size

One plausible reason why PSM sample results show larger equity issuance effects than full sample results relates to differences in firm size. Our previous estimates show that connected firms are substantially larger than unconnected firms in the full sample (Table 2, Panel B). However, the largest connected firms are dropped from the PSM sample (Appendix Fig. 9). If smaller firms were more reactive to the internationalization events, the difference in the firm size between the two sample groups could explain – at least in part – the differences between the full sample and PSM sample results. This is plausible because smaller firms, which tend to be more financially constrained, could react more to equity internationalization events than larger corporations.

To verify this formally, we disaggregate the connected firms in the PSM sample by size (defined by total assets in 2010–2012). We then re-estimate the difference-in-differences equation for each subgroup (Appendix Tables 11 and 12). We find that the smallest firms (in the lowest quartile) in the PSM sample raised the most equity post-2012 (as a fraction of total assets in 2012), and the magnitude of the impact decreases monotonically in firm size (Fig. 4, Panel A). Consistent with this pattern, we also show that the smaller connected firms (below the median) increased their equity issuances relative to the larger connected firms (above the median) during 2014–2020 (Fig. 4, Panel B). The correlation between equity issuance reactions and firm size survives even when excluding state-owned enterprises (SOEs) from the sample. This is important because SOEs are relatively large corporations whose investment reacted less to the Stock Connect than privately owned firms (Ma et al. 2021).Footnote 28

Differences in equity issuance behavior: connected firms of different sizes. This figure shows differences in equity issuances among connected firms of different sizes in the propensity score matched (PSM) sample. Firm size is measured as the average total assets in 2010–2012. Panel A compares connected firms of different sizes with unconnected firms. Connected firms are divided into four groups according to their size: firms with assets below the 25th percentile, firms with assets between the 25th and 50th percentiles, firms with assets between the 50th and 75th percentiles, and firms with assets above the 75th percentile of the firm size distribution of connected firms. Panel B compares connected firms with sizes below the median (50th percentile) with those with sizes above the median. Both panels plot the difference-in-differences (DiD) coefficients (and their 90% confidence intervals) obtained by estimating Equation (1), using the cumulative amount of equity raised over 2012 assets as the dependent variable. The 2012 coefficients show the differences across groups that year. The shaded areas capture the implementation of the Stock Connect program and the incorporation of domestic listed stocks into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Appendix Tables 11 and 12 report the coefficients shown in this figure

4.1.3 Robustness and Extensions

We perform and report robustness tests for the PSM sample (Table 3, Columns 6-9) and full sample (Appendix Table 13). We (1) control for lagged assets and sales growth, (2) control for the size of bond issuances, (3) exclude firms with margin trading stocks, and (4) exclude firms with stocks purchased by the government during 2015–2019.Footnote 29 Controlling for lagged total assets and sales growth allows us to ensure that changes in firm size or demand conditions do not drive our estimates of the impact of internationalization events. The other robustness tests help us disentangle the effect of the internationalization process from other financial shocks that could have affected connected and unconnected firms differently around the internationalization period.

The estimates remain significant when including lagged assets and sales growth but are slightly smaller than those in the baseline regression. This could be because the internationalization process also affects these additional controls. For instance, if firms could raise more equity financing through the Stock Connect, they could grow faster and have higher total assets.

One potentially confounding factor is the internationalization of bond markets post-2012, which could have affected equity issuances. The QFII and RFQII programs allowed qualified foreign investors to purchase corporate bonds. Moreover, China implemented a “Bond Connect” program in 2017. However, neither the QFII nor RQFII programs nor the Bond Connect program specifically targeted firms connected through the Stock Connect program. Thus, it is difficult to associate the differential equity issuances between connected and unconnected firms with the internationalization of bond markets. Still, to ensure that bond market events do not contaminate our equity results, we add as a control the proceeds from bond issuances per firm and year over 2012 assets. The baseline equity results do not change materially.

A second potential confounding event was the implementation of margin trading, which began in 2010 and expanded in 2013 to some eligible stocks. By allowing investors to borrow to buy shares, margin trading could have prompted equity issuances, potentially explaining the differential behavior between connected and unconnected firms. To ensure this event does not drive our estimates, we exclude margin trading firms (those whose stocks became eligible for margin trading during 2010–2017), many of which were also connected. About 32 (11) percent of the connected (unconnected) firms in our PSM sample had eligible margin trading stocks. The estimates of the impact of internationalization become larger when we exclude firms with margin trading stocks.

A third potential confounding event was the government purchase of stocks to stabilize the market following the 2015 crash in equity prices. The Securities Finance Corporation and other government institutions targeted selected firms, possibly benefiting connected firms relatively more. We exclude firms with stocks purchased by the government during 2015–2019 (following Ling et al. 2022), which constitute about 37 (41) percent of the connected (unconnected) firms in our PSM sample. The estimates of the impact of internationalization become slightly larger when we exclude these firms.

Overall, the results show a robust and significant difference in issuance activity between connected and unconnected firms during the post-2012 internationalization period. Because margin trading and intervened firms were, on average, 130 and 75 percent larger than the other domestic listed firms, the larger effect we find when excluding them is consistent with the size-related reaction to the internationalization events discussed earlier.

4.2 Event Studies

This section presents event-specific results for the implementation of the Stock Connect in Shanghai (2014) and Shenzhen (2016). In contrast to the baseline analysis, here we restrict the sample in each event study to firms listed in that specific stock market. We separately analyze only the Shanghai listed firms connected in 2014 and the Shenzhen listed firms connected in 2016. Hence, the treatment group dummy variable \({D}_{i}^{ Treated}\) in Equation (1) becomes event specific.

This exercise not only allows us to understand and compare the impact of different events, but also helps us better identify the impact of these events. If our baseline estimates were confounded by other concurrent shocks or policy changes in the domestic financial markets, we would not see a significantly positive \({\widehat{\beta }}_{t}\) for both events, unless the confounding factors also occurred in two different periods and in each equity market.

We run PSM regressions for each event to ensure that firms in the treatment and control groups had similar characteristics before the event in each case. As there is significant variation in firm size, especially for Shanghai listed firms, we use the average total assets in 2010–2012 to predict the probability of being connected within each exchange. In doing so, we remove most of the ex-ante difference in size between connected and unconnected firms (Appendix Fig. 12).

We find a positive and significant impact of the Stock Connect program for firms in each stock market (Appendix Table 15). Among firms listed in Shanghai, the ratio of equity raised over assets increased by about 7 p.p. more for connected firms relative to unconnected firms in 2015. The cumulative difference was 17 p.p. in 2020 (Fig. 5, Panel A). Among firms listed in Shenzhen, the ratio of equity raised over assets increased by 22 p.p. for connected firms relative to unconnected firms in 2016, and the cumulative difference was 42 p.p. in 2020 (Fig. 5, Panel B). Since firms listed in Shanghai are, on average, larger than firms listed in Shenzhen (Appendix Fig. 12), the fact that connected firms in Shenzhen reacted more than connected firms in Shanghai is consistent with our size-related results.

Differences in equity issuance behavior: Shanghai and Shenzhen events. This figure shows differences in equity issuances between connected and unconnected firms listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen. The figure plots the difference-in-differences (DiD) coefficients (and their 90% confidence intervals) obtained by estimating Equation (1), using the cumulative amount of equity raised over 2012 assets as the dependent variable. The DiD coefficients show, for each year, the average differences in equity issuances between connected and unconnected firms (relative to the 2012 difference). The 2012 coefficients show the differences between connected and unconnected firms in 2012. Panel A uses the propensity score matched (PSM) sample of firms listed in Shanghai. Panel B uses the PSM sample of firms listed in Shenzhen. The shaded areas capture the formal announcement and implementation of the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect and Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect. Appendix Table 14 reports the coefficients shown in this figure

4.3 Investment Activity

To examine the effect of internationalization on firms’ investment activity, we focus on capital expenditures (capex), spending on acquisitions, R&D, and cash and short-term investments.Footnote 30 While cash and short-term investments are measured as stock values each year, capex, acquisitions, and R&D are flows, so the changes in those variables are not easily comparable.

We study again the differences between connected and unconnected firms. We run the baseline difference-in-differences specification (Eq. 1) using the following dependent variables in turn: capex over total assets, acquisitions over assets, R&D over assets, and cash and short-term investments over assets. Assets are measured as of 2012. We report the estimated difference-in-differences coefficients, \({\widehat{\beta }}_{t}\), from each regression using the full and PSM samples (Appendix Table 15).

The key takeaway is that both connected and unconnected firms followed similar trends in their investments (of all types) before 2013, but the behavior of the two groups diverged since then. The connected group invested significantly more than the unconnected group during 2014–2016. By 2016, the difference between the two groups in the PSM sample was approximately 8 p.p. for capex to assets, 6 p.p. for acquisitions to assets, 2 p.p. for R&D to assets, and 28 p.p. for cash to assets (Fig. 6). Except for acquisitions, the differences between connected and unconnected firms remained high and significant during the 2018–2020 MSCI incorporation process.Footnote 31

Differences in investment behavior: connected versus unconnected domestic listed firms. This figure shows differences in investment behavior (for capital expenditures, acquisitions, research & development, and cash & short-term investments) between connected and unconnected firms in the propensity score matched (PSM) sample. The figure plots, for each variable, difference-in-differences (DiD) coefficients (and their 90% confidence intervals) obtained by estimating Equation (1). The DiD coefficients show, for each year, the average differences for each dependent variable between connected and unconnected firms (relative to the 2012 difference). The 2012 coefficients show the differences between connected and unconnected firms in 2012. The shaded areas capture the implementation of the Stock Connect program and the incorporation of domestic listed stocks into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Appendix Table 15 reports the coefficients shown in this figure

Next, we examine how much of the increase in each investment measure was financed by equity issuances, our primary variable of interest. We follow the methodology of Kim and Weisbach (2008), which controls for other sources of financing. We first construct a panel dataset from the full sample such that for each firm i, we keep the observations in each year t \(\in\) (2013, 2020) with positive equity issuances (\({issuance\;value}_{it}\) > 0), as well as the observations in the pre-issuance (t–1) and post-issuance (t+1) years. Then, we estimate the following regression for the 2013–2020 period:

where \(assets_{it - 1}\) denote firm i’s total assets in the pre-issuance yeart-1, and total resources represent the total funds generated by the firm internally and externally. The dependent variable is

We estimate separate regressions for k = 0 (issuance year) and k=1 (post-issuance year). The panel data used in this exercise are unbalanced by construction: all firm-level variables in Equation (2) are defined only if \(issuance \,value_{it}\)>0; otherwise, they are treated as missing values. \(\alpha_{j}\) denotes industry fixed effects. \(\gamma_{t}\) represents year fixed effects.

The coefficient of interest, \(\beta_{1}\), measures the proportion of proceeds raised per issuance for each type of investment. To facilitate the interpretation, we convert the estimates into the dollar effect, i.e., how much of every dollar raised in equity is used in every investment. We first calculate the predicted values of the dependent variable by plugging into Equation (2) the value of equity issuance and the estimated \(\hat{\beta }_{1}\). We then re-compute the predicted values of the dependent variable by adding one US dollar to the issuance value. Next, we calculate the difference between the two predicted values to obtain the marginal change in the use of proceeds. Last, we compute the average change per firm (across its equity issuances) and show the results for the median firm.

The results show that in the equity issuance year (k=0), the median connected firm invested 14 cents in capex, 24 cents in acquisitions, 2 cents in R&D, and 52 cents in cash and short-term investments for every dollar raised in equity (Table 4). In the post-issuance year (k=1), capex investment increased to 26 cents per dollar raised compared to the previous year. Cash and short-term investments remained the most common use of proceeds.

4.4 Aggregate Impact

How much did the post-2012 internationalization of equity markets contribute to the overall financing and investment activities of publicly listed firms in China? For financing activity, we look at total equity raised and total market capitalization; for investment activity, we consider capex, acquisitions, R&D, and cash and short-term assets. We calculate the aggregate impact on these variables using estimates from the difference-in-differences regressions in the full sample, where we distinguish between connected and unconnected firms. Since we are interested in the impact on the level of each variable, we re-estimate Equation (1) with the different dependent variables expressed in levels (denoted by \(Y_{it}\)).Footnote 32

The difference-in-differences coefficient estimate \(\hat{\beta }_{t}\) captures, for each year t, not only the differential change for the connected group (relative to the unconnected group) but also the difference between the average actual outcome among the connected firms \(\overline{Y}_{t}^{T} \equiv E\left[ {Y_{it}^{T} } \right]\) and the average counterfactual outcome \(\overline{Y}_{t}^{CF} \equiv E\left[ {Y_{it}^{CF} } \right]\). The counterfactual outcome assumes no internationalization among connected firms in a post-internationalization year. As a result, the aggregate impact of the internationalization (in dollars), for each year t, is given by the average impact \(\hat{\beta }_{t}\) multiplied by the number of connected firms \(N_{C}\), i.e., \(Y_{t}^{T} - Y_{t}^{CF} = N_{C} \hat{\beta }_{t}\).Footnote 33 The estimated coefficients \(\hat{\beta }_{t}\) are reported in Appendix Table 16. Insignificant estimates are treated as zeros in our calculations.

For each variable of interest, we compute the cumulative aggregate effect of the internationalization events between 2013 and 2020 as a percentage of the actual aggregate outcomes. More specifically, for equity raised, capex, acquisitions, and R&D, we calculate the ratio of the cumulative aggregate impact to the cumulative aggregate outcome, i.e., \(\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{t = 2013}^{t = 2020} \left( {Y_{t}^{T} - Y_{t}^{CF} } \right)}}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{t = 2013}^{t = 2020} Y_{t} }}\). For the stock variables market capitalization and cash, we calculate the ratio of the aggregate impact in 2020 to the aggregate outcome in the same year. We consider three candidates for the denominator \(Y_{t}\): the actual aggregate outcome among all connected firms, all domestic listed firms (connected and unconnected), and all publicly listed firms (domestic and foreign listed).Footnote 34

Our back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that the internationalization events had a sizable aggregate impact on both financing and investment activities by firms in China (Table 5). In the full sample, around 33 percent of all equity raised by connected firms, 28 percent of all equity raised by domestic listed firms, and 20 percent of all equity raised in China between 2013 and 2020 are associated with the internationalization events. The effects on market capitalization by 2020 are of similar magnitudes. The post-2012 internationalization process could explain about a quarter of all cash and short-term investments, 24 percent of all R&D expenditures, 12 percent of acquisitions, and 11 percent of all capex by all domestic listed firms between 2013 and 2020.Footnote 35

While our estimates indicate potentially sizable aggregate effects, pinpointing the precise magnitude is challenging. Aggregating firm-level responses is non-trivial, and our approach has limitations. It is difficult to disentangle the impact of internationalization events from other concurrent aggregate shocks in the domestic financial markets. To identify the effect of the events as cleanly as possible, we defined connected firms as those that were exposed to internationalization for the first time since the Stock Connect program, but dual listed firms also had A shares that participated in the program. Our estimates of aggregate effects do not include the impact on their equity issuances and investment activities.

Other limitations of the aggregate estimates are related to the partial equilibrium approach we take in aggregation. For instance, our regression estimates only measure the direct impact on connected firms and do not include any potential spillover effects from connected to unconnected firms or the general equilibrium effects on prices and wages.Footnote 36 Without a structural model incorporating these channels, predicting whether the general equilibrium effects will dampen or amplify the firm-level responses is challenging. Nevertheless, our simple and transparent approach provides a useful first step toward understanding the potential aggregate impact of China’s internationalization events.

4.5 Investor Behavior

We exploit additional data sources to explore the behavior of investors around the internationalization events. We retrieve (1) aggregate data on foreign equity inflows from the IMF’s balance of payments statistics; (2) aggregate data on foreign equity holdings via the QFII/RQFII programs and the Stock Connect program from Wind; (3) firm-level data on the share of foreign ownership from Refinitiv; (4) country-level bilateral data on foreign equity holdings from the IMF’s Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS).

Foreign investors entered relatively late in the internationalization process. Although foreign equity inflows increased in 2014, they experienced their fastest growth during 2018–2020. Foreign equity inflows were about 15 billion US dollars in 2015 and more than 80 billion in 2020 (Fig. 7, Panel A). In addition, aggregate foreign equity holdings through the Stock Connect program, which channeled most of the 2018–2020 expansion in foreign participation, rose from 15 billion US dollars in 2015 to 151 billion in 2020 (Fig. 7, Panel B). Nonetheless, foreign equity holdings were far from their quota limits in the QFII/RQFII or the Stock Connect program. Those limits were removed in 2020 and 2016, respectively (Appendix Fig. 13).

Foreign equity investment into China. This figure shows the evolution of foreign equity investment in China. Panel A shows annual foreign equity portfolio inflows into China and annual proceeds from domestic equity issuances (excluding initial public offerings). Foreign inflows correspond to net changes in foreign portfolio equity positions in China (stocks, participations, depositary receipts, private equity of unlisted firms, mutual funds, and investment trusts). Panel B shows the outstanding value of foreign equity holdings bought through the QFII and RQFII programs (combined) and the Stock Connect program. Panel C shows the average foreign ownership ratio across domestic listed firms each year. The foreign ownership ratio is the value of shares held by investors outside mainland China over the total value of shares outstanding per firm. Panel D shows the evolution of China’s weight in foreign equity positions relative to all emerging economies (CPIS Weight) and China’s weight in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index (MSCI Weight). The panel also plots (in red) two counterfactual scenarios for China's weight in the MSCI in 2018–2020: with an inclusion factor (IF) for the A shares equal to 100 percent and 0 percent. The definition of emerging economies follows the MSCI classification of emerging countries in 2020. Values are expressed in billions of 2011 US dollars (USD). Sources: Balance of Payments from the IMF, Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS), MSCI, Refinitiv, and Wind

Domestic investors seemed to have provided bridge financing for domestic firms before international investors increased their participation. Foreign equity inflows were substantially smaller than domestic equity issuances during 2014–2017. This suggests that domestic rather than international investors bought most of the new shares issued during those years. Foreign equity inflows surpassed domestic equity issuances during 2018–2020.Footnote 37

Next, we analyze the evolution in firms’ foreign ownership structure. We compute the percentage of foreign ownership, the value of shares held by investors outside mainland China over the total value of shares outstanding per firm. We plot the average foreign ownership ratio across domestic listed firms over time (Fig. 7, Panel C). The figure shows how the foreign ownership ratio substantially increased during 2018–2020 relative to previous years. By 2020, the average percentage of foreign owned shares per firm had almost tripled compared to 2016, from 1.3 percent to 3.8 percent.

Overall, the evidence suggests that most of the increase in foreign equity investment in China occurred with the addition of domestic listed stocks to the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.Footnote 38 China’s weights in foreign equity holdings (from CPIS data) and in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index followed a similar trend (Fig. 7, Panel D). However, the CPIS weight lagged behind the MSCI weight during 2016–2020.Footnote 39 By 2020, China accounted for approximately 40 percent of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index and less than 30 percent of the CPIS emerging market equity portfolios.Footnote 40

5 Conclusion

This paper showed that China’s post-2012 equity market internationalization benefits have been significant and spanned multiple years. At the firm level, those targeted by the internationalization events raised significantly more equity financing, increased their cash holdings, and invested more than other domestic firms. At the aggregate level, the internationalization process was associated with a significant fraction of equity raised and investment activities among all domestic listed firms in China between 2013 and 2020. Most of the rise in equity issuances by connected firms appeared to be primarily supported by domestic investors that increased their investments in those firms. Foreign entry only accelerated after China’s A shares were incorporated into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index in the late 2010s.

The importance of China in emerging market equity portfolios has grown gradually but could increase further. Market makers and authorities have integrated China progressively to minimize the potential for domestic disruptions caused by a surge in portfolio inflows and to avoid sudden large capital outflows from other emerging markets. As long as China’s weight in emerging market equity portfolios lags behind its weight in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index and investors follow the index, a catch-up in foreign investments could be expected. Moreover, China’s internationalization efforts expanded even further in 2023, when it connected more than 1,000 new firms. About 90 percent of the total market capitalization became open to foreign investors, prompting them to increase their financing of domestic firms.

The exceptionally high savings rate in China before and during the internationalization events might have allowed connected firms to obtain domestic financing, ultimately fueling the growth of the corporate sector before the arrival of international investors. In this regard, our results for China could overstate the benefits of internationalization for other emerging economies without a strong domestic investor base and high saving rates. On the other hand, to the extent that China remains underrepresented in international investors’ portfolios, our results could understate the benefits of internationalization for other countries with higher foreign participation.

Notes

Foreigners could only buy specific shares denominated in foreign currency (B shares) issued by a very limited number of firms in the mainland stock markets or invest in Chinese stocks by buying shares in Hong Kong SAR, China (H shares).

Mapping firm-level estimates into macroeconomic outcomes is non-trivial. Without a structural model, we cannot capture the general equilibrium effects associated with the liberalization events. Our estimates of the aggregate effect provide a useful benchmark for any future work that investigates the aggregate impact through the lens of a model.

In turn, eligible domestic (Chinese) institutional investors gained access to stocks listed in Hong Kong, through the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges.

The Shenzhen Connect also includes the SZE Small/Mid Cap Innovation Index with a minimum market cap of 6 billion renminbi.

The new reform allowed investors to trade stocks anonymously on a centralized trading platform set up by the Shanghai and Hong Kong Stock Exchanges, subject to a foreign investors’ aggregate quota of 300 billion renminbi (40 billion US dollar) quota. This aggregate quota was abolished in 2016 (Appendix Table 6).

The inclusion factor is the proportion of a security’s free float‐adjusted market capitalization that is allocated to the index.

Other foreign equity benchmark indexes followed MSCI. In September 2018, the Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE) Russell announced the official inclusion of China’s A shares into its Global Equity Index Series (FTSE GEIS). In September 2019, A shares were officially included in the FTSE indexes with an inclusion factor of 5 percent. In August 2019, FTSE Russell increased the inclusion factor of A shares from 5 to 15 percent. In September 2019, Standard and Poor’s (S&P) Dow Jones Indices added China’s A shares to its S&P Global Broad Market Index (BMI) at an inclusion factor of 25 percent.

One of the key internationalization reforms – the Stock Connect program – also affected the capital market in Hong Kong. Indeed, part of the growth in the market capitalization in Hong Kong since 2013 could be attributed to Southbound trading activities from the Connect program. Nonetheless, the market capitalization in mainland China rose substantially more after 2013 (Fig. 1, Panel A).

All value variables in our sample are in 2011 US dollars. See Appendix Table 9 for a detailed definition of the main variables used in the paper.

Chinese firms issuing American Depository Receipts (ADRs) are also categorized as foreign listed firms. Foreign listed firms include Chinese firms that raised capital in international markets through variable interest entities (VIEs).

Dual listed firms include mostly Chinese companies with stocks listed in both the mainland stock markets (Shanghai or Shenzhen) and the Hong Kong stock market. Alternatively, we exclude the dual listed firms from the foreign listed group, restricting this group to firms that are exclusively listed abroad.

We focus on firms connected during 2014–2018 and omit those connected afterward. A shares from connected and unconnected firms were available to foreign institutional investors through the QFII/RQFII programs.

The estimates for \({\beta }_{t}\) are identical if we include firm fixed effects instead because \({\beta }_{t}\) focuses on overtime changes in differences across firms.

To minimize the impact of outliers, we remove values above (below) the 99th percentile (1st percentile) for each variable of interest.

We also conduct separate event studies for the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect in 2014 and the Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect in 2016, where we restrict the sample to firms listed in each market, and the dummy variable captures only the connected firms in each event (Section 4.2). This exercise not only allows us to compare the impact of different internationalization events, but also provides additional evidence that our estimates are likely to capture the impact of these episodes instead of other concurrent shocks or policy changes in the domestic financial markets.

The addition of stocks to domestic equity indexes (and to the Stock Connect program) depends on the firms’ market capitalization. Therefore, size is expected to be a major difference between connected and unconnected firms.

We obtain comparable subsamples of connected and unconnected firms based on their equity and debt financing, size, cash flow volatility, and investment ex-ante. In unreported specifications, we also used only size-related variables to predict the probability of becoming a connected firm and obtained similar results. We do not use R&D to perform the PSM because of the higher incidence of missing values (about 54 percent of firms have R&D data).

As shown below, larger firms have more muted responses to internationalization events. Thus, the fact that connected firms in our PSM sample are slightly larger than unconnected firms would likely bias our PSM estimates downward.

The fast expansion in firms’ equity issuances during 2014–2017 likely reduced their needs for external financing during 2018–2020, as firms take time to deploy the cash accumulated from lumpy financing (Bazdresch 2013). This is consistent with the continued rise of capital expenditures during 2018–2020 (Sect. 4.3). The 2018–2020 decline in equity raised is not explained by the exclusion of IPOs from the sample (Appendix Fig. 8).

Table 3 shows the regression results using the amount of equity raised per firm-year (over 2012 assets) as dependent variable. Figure 3 and Appendix Table 10 show the estimated difference-in-differences coefficients \({\widehat{\beta }}_{t}\) using the cumulative amount raised up to each year as dependent variable.

The low levels of equity issuance activity by connected and unconnected firms during 2000–2012 (below 1 percent of equity to assets ratios) indicate that differences since 2014 were economically large (Appendix Fig. 10).

We define as SOEs firms for which the main (top 1) shareholder is a government-related entity (following Ma et al. 2021). We merge our main dataset with 2007–2020 firm-level data on firm ownership structure downloaded from Wind. We consider SOEs to be all firms with a government-related principal shareholder any year between 2007 and 2020. Around 37 percent of firms in our domestic listed sample are SOEs. They are about twice as large as the rest of the (private) firms.

As two additional robustness tests, we used the log of equity raised as dependent variable (instead of the amount raised over assets) and excluded financial firms. The log of equity raised as the dependent variable provides an alternative equity issuance measure that is not scaled by firms’ assets. Financial firms only constitute around 3.4 percent of our sample and excluding them barely changes the results.

We use the Worldscope definition for each variable, as detailed in Appendix Table 9.

The differences are sizable relative to the overall levels. For example, the difference in capex for connected firms accounts for about 60 percent of the level in 2016 (Appendix Fig. 11).

We use the superscript T to denote the treated group (the connected firms in this exercise) and the superscript CF to denote the counterfactual outcome for the treated group. The average actual outcome among the connected firms in post-internationalization year t is given by \(\bar{Y}_{t}^{T} = {\text{~}}\hat{\sigma } + \hat{\theta } + \hat{\gamma }_{t} + \hat{\beta }_{t}\). The average counterfactual outcome for this group, by definition, is given by \(\bar{Y}_{t}^{{CF}} = \bar{Y}_{0}^{T} + \left( {\bar{Y}_{t}^{C} - \bar{Y}_{0}^{C} } \right) = \hat{\sigma } + \hat{\theta } + \hat{\gamma }_{t}\), where the superscript C denotes the control group (the unconnected firms). The alternative interpretation of the difference-in-differences coefficient follows directly, as \({\widehat{\beta }}_{t}={\bar{Y}}_{t}^{T}-{\bar{Y}}_{t}^{CF}.\)

We remove the top 1 percent of each variable (“outliers”) before running each difference-in-differences regression to obtain clean estimates of \({\widehat{\beta }}_{t}\). Nonetheless, since our goal here is to compute the aggregate effect, we multiply \({\widehat{\beta }}_{t}\) by the total number of connected firms; in other words, we are assigning the average impact to both outliers and non-outliers.

For consistency with the numerator and for the purpose of measuring the aggregate effect, the aggregate data (the denominator) also contain the values for the top 1 percent of each variable.

Appendix Table 17 explores a range of plausible values for the aggregate effect on each variable of interest. We also perform the same exercise using the PSM sample of firms, available in the working paper version of this paper (Cortina et al. 2023). Since the \({\widehat{\beta }}_{t}\) estimates are larger in the PSM sample, the “aggregate” impact of these events using the PSM subsample is also notably larger than the overall impact in the full sample.

Spillover effects to the unconnected firms could occur if more funds were available to them when connected firms tapped into the international markets for funding and became less reliant on domestic finance. In principle, these spillover effects could bias our difference-in-difference estimates downward, even after addressing selection issues between connected and unconnected firms. Nevertheless, evidence on the investor side (shown in Section 4.5) suggests that the supply of domestic finance increased for the connected firms during the internationalization events.

Some minimum degree of bridge financing had to occur because, by regulation, firms could sell the shares of the primary issuance activity (IPOs or SEOs) only to domestic investors. However, after purchasing them from firms, domestic investors could have immediately sold those shares to international investors. Thus, this regulation does not explain the years of bridge financing domestic investors provided.

Comparing portfolio equity inflows with foreign direct investments (FDI) into China shows that the former grew relative to the latter during the internationalization process. Specifically, portfolio equity flows were about 15 percent of FDI inflows during 2010–2013. They grew relative to FDI, especially during the 2018–2020 MSCI incorporation, reaching 32 percent of FDI in 2020. This pattern supports the idea that the shock occurred in the financial sector and was related to specific equity market internationalization events. It runs against the notion that it was part of a broader trend in foreign financing to China.

In addition, we simulate two alternative scenarios: scenarios if A shares were included in the index in 2018 with an inclusion factor of 100 percent and 0 percent. As would be expected, China’s actual weight in the index is in between the two counterfactual scenarios, suggesting that it may continue to rise if market makers increase the inclusion ratio.

Investments in China have surpassed investments in other emerging markets and have increased significantly since 2006. But the pace of growth has notably changed since 2017.

References

Acharya, Viral V., Soku Byoun, and Zhaoxia Xu. 2020a. The sensitivity of cash savings to the cost of capital, NBER Working Paper No. 27517.

Acharya, Viral V., Jun Qian, Yang Su, and Zhishu Yang. 2020b. In the shadow of banks: wealth management products and issuing banks’ risks in China, CEPR Discussion Papers 14957.

Antonelli, Stefano, Flavia Corneli, Fabrizio Ferriani, and Andrea Gazzani. 2022. Benchmark Effects from the Inclusion of Chinese A-shares in the MSCI EM index. Economics Letters 216: 110600.

Bai, Ye, and Darien Yan Pang Chow. 2017. Shanghai-Hong Kong stock connect: an analysis of chinese partial stock market liberalization impact on the local and foreign markets. Journal of International Financial Markets 50: 182–203.

Bazdresch, Santiago. 2013. The role of non-convex costs in firms’ investment and financial dynamics. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 37(5): 929–950.

Bekaert, Geert, Campbell R. Harvey, and Christian Lundblad. 2001. Emerging equity markets and economic development. Journal of Development Economics 66(2): 465–504.

Bekaert, Geert, Campbell R. Harvey, and Christian Lundblad. 2005. Does financial liberalization spur growth? Journal of Financial Economics 77(1): 3–55.

Bruno, Valentina and Hyun Song Shin. 2017. Global dollar credit and carry trades: a firm-level analysis. Review of Financial Studies 30(3): 703–749.

Calomiris, C.W., Mauricio Larrain, and Sergio L. Schmukler. 2021. Capital inflows, equity issuance activity, and corporate investment. Journal of Financial Intermediation 46: 100845.

Cerutti, Eugenio, and Maurice Obstfeld. 2019. "China’s bond market and global financial markets," in The Future of China’s Bond Market, ed. by Alfred Schipke, Markus Rodlauer, and Longmei Zhang, International Monetary Fund.

Chan, Marc K. and Simon Kwok. 2017. Risk-sharing, market imperfections, asset prices: evidence from China’s stock market liberalization. Journal of Banking and Finance 84: 166–187.

Chari, Anusha and Peter Blair Henry. 2004. Risk sharing and asset prices: evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Finance 59: 1295–1324.

Chari, Anusha and Peter Blair Henry. 2008. Firm-specific information and the efficiency of investment. Journal of Financial Economics 87(3): 636–655.

Chen, Sicen, Shuping Lin, Jinli Xiao, and Pengdong Zhang. 2022. Do managers learn from stock prices in emerging markets? evidence from China. European Journal of Finance 28: 377–396.

Chen, Zhuo, Zhiguo He, and Chun Liu. 2020. The financing of local government in China: stimulus loan wanes and shadow banking waxes. Journal of Financial Economics 137(1): 42–71.

Chiang, Thomas C., Edward Nelling, and Lin Tan. 2008. The speed of adjustment to information: evidence from the Chinese stock market. International Review of Economics & Finance 17(2): 216–229.

Clayton, Christopher, Amanda Dos Santos, Matteo Maggiori, and Jesse Schreger. 2022 Internationalizing like China, NBER Working Paper No. 30336.

Cortina, Juan J., Maria Soledad Martinez Peria, Sergio L. Schmukler, and Jasmine Xiao. 2023. The Internationalization of China’s equity markets, IMF Working Paper 2023/026 and World Bank Working Paper 10513.

Cremers, Martijn, Miguel A. Ferreira, Pedro Matos, and Laura Starks. 2016. Indexing and active fund management: international evidence. Journal of Financial Economics 120(3): 539–560.

Edison, Hali J., Michael W. Klein, Luca Antonio Ricci, and Torsten Sløk. 2004. Capital account liberalization and economic performance: survey and synthesis. IMF Staff Papers 51(2): 861–875.

Erel, Isil, Brandon Julio, Woojin Kim, and Michael S. Weisbach. 2012. Macroeconomic conditions and capital raising. Review of Financial Studies 25(2): 341–376.

Flavin, Thomas and Thomas O’Connor. 2010. The sequencing of stock market liberalization events and corporate financing decisions. Emerging Markets Review 11(3): 183–204.

Gupta, Nandini and Kathy Yuan. 2009. On the growth effect of stock market liberalizations. Review of Financial Studies 22(11): 4715–4752.

Hau, Harald. 2011. Global versus local asset pricing: a new test of market integration. Review of Financial Studies 24(12): 3891–3940.

Henry, Peter Blair. 2000. Stock market liberalization, economic reform, and emerging market equity prices. Journal of Finance 55(2): 529–564.

Huang, Wei and Tao Zhu. 2015. Foreign institutional investors and corporate governance in emerging markets: evidence of a split-share structure reform in China. Journal of Corporate Finance 32: 312–326.

Kim, Woojin and Michael S. Weisbach. 2008. Motivations for public equity offers: an international perspective. Journal of Financial Economics 87(2): 281–307.

Kose, Ayhan M., Eswar S. Prasad, Kenneth Rogoff, and Shang-Jin. Wei. 2009. Financial globalization: a reappraisal. IMF Staff Papers 56(1): 8–62.

Lane, Philip and Sergio Schmukler. 2007. The evolving role of China and India in the global financial system. Open Economies Review 18(4): 499–520.

Li, Zhisheng, Xiaoran Ni, and Jiaren Pang. 2020. Stock market liberalization and corporate investment revisited, SSRN.

Ling, Jin, Zhisheng Li, Lei Lu, and Xiaoran Ni. 2022. Does stock market rescue affect investment efficiency in the real sector? SSRN.

Ma, Chang, John Rogers, and Sili Zhou. 2021. The effect of China connect, SSRN.

McLean, David, Jeffrey Pontiff, and Mengxin Zhao. 2022. A closer look at the effects of equity market liberalization in emerging markets, Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 2022: 1–30.

Mitton, Todd. 2006. Stock market liberalization and operating performance at the firm level. Journal of Financial Economics 81(3): 625–647.

Mo, Jingyuan, and Marti G. Subrahmanyam. 2020. What drives liquidity in the Chinese credit bond markets? SSRN.

Peng, Liao, Liguang Zhang, and Wanyi Chen. 2021. Capital market liberalization and investment efficiency: evidence from China. Financial Analysts Journal 77(4): 23–44.

Prasad, Eswar S., Raghuram G. Rajan, and Arvind Subramanian. 2007. Foreign capital and economic growth. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 38: 153–209.

Quinn, Dennis P. and A. Maria Toyoda. 2008. Does capital account liberalization lead to growth? Review of Financial Studies 21(3): 1403–1449.

Raddatz, Claudio, Sergio L. Schmukler, and Tomas Williams. 2017. International asset allocations and capital flows: the benchmark effect. Journal of International Economics 108: 413–430.

Stulz, Rene M. 1999. Globalization of equity markets and the cost of capital. NBER Working Paper No. 7021.

Wang, Shuxun. 2021. How does stock market liberalization influence corporate innovation? evidence from stock connect scheme in China. Emerging Markets Review 47: 100762.

Yao, Shujie, Hongbo He, Shou Chen, and Ou. Jingha. 2018. Financial liberalization and cross-border market integration: evidence from China’s stock market. International Review of Economics and Finance 58: 220–245.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper was written for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) 23rd Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference in honor of Maurice Obstfeld, whose work inspired this research. We are grateful to Ariadne Checo de los Santos, Gianluca Yong Gonzalez, and especially Yang Liu and Patricio Yunis for excellent research assistance. We received very helpful comments from Yingyuan Chen, Ergys Islamaj, Phakawa Jaesakul, Joong Kang, Michael Klein, Michael Law, Andrei Levchenko, Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, Tomas Williams, two anonymous referees, and other conference participants. For research support, we are grateful to the World Bank Knowledge for Change Program and the Research Support Budget. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF or the World Bank and its affiliated organizations, those of the Executive Directors of the IMF or the World Bank, or the governments they represent. Cortina and Schmukler are with the World Bank; Martinez Peria is with the International Monetary Fund; Xiao is with the University of Notre Dame.

Appendix

Appendix

See Figures 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13.