Abstract

We analyse the economic conditions (the “shocks”) behind currency movements and show how that analysis can help address a range of questions, focussing on exchange rate pass-through to prices. We build on a methodology previously developed for the UK and adapt this framework so that it can be applied to a diverse sample of countries using widely available data. The paper provides three examples of how this enriched methodology can be used to provide insights into pass-through and other questions. First, it shows that exchange rate movements caused by monetary policy shocks consistently correspond to significantly higher pass-through than those caused by demand shocks in a cross-section of countries, confirming earlier results for the UK. Second, it shows that the underlying shocks (especially monetary policy shocks) are particularly important for understanding the time-series dimension of pass-through, while the standard structural variables highlighted in the previous literature are most important for the cross-section dimension. Finally, the paper explores how the methodology can be used to shed light on the effects of monetary policy and the debate on “currency wars”: it shows that the role of monetary policy shocks in driving the exchange rate has increased moderately since the global financial crisis in advanced economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Exchange rate movements affect a wide range of economic variables—from the ability of a company to service its debt or compete internationally, to a country’s inflation rate and GDP growth. Therefore, understanding how any exchange rate fluctuation affects these economic variables is critically important for modelling macroeconomic dynamics, economic forecasting, and setting monetary policy. Estimating the impact of exchange rate movements, however, is not straightforward. For example, the pass-through from exchange rate movements to prices (ERPT) not only varies substantially across countries and over longer time spans (the focus of most empirical work), but also over shorter periods within countries. This paper shows that in order to understand the impact of exchange rate movements on inflation and other variables, it is important to explicitly model and incorporate the economic conditions driving exchange rate movements (i.e. the shocks). It builds on a SVAR framework that was previously developed to explicitly model the role of the shocks behind exchange rate movements for the UK, but adapts the framework so that it can be applied using widely available data for a range of diverse countries. Then it provides several examples of how this framework can be used to improve our understanding of inflation dynamics for a range of countries, as well as to provide insights into other important economic developments.

To motivate this analysis, the paper begins by estimating pass-through to consumer prices using a standard reduced-form model, based on the seminal work in Campa and Goldberg (2005, 2010), recently updated in Burstein and Gopinath (2014). We focus on a sample of 26 small open economies with flexible exchange rates that will also form the basis for the subsequent analysis. The reduced-form estimates of pass-through confirm earlier work highlighting substantial variation across countries. A large empirical literature has focused on explaining these meaningful differences in pass-through across countries by examining structural economic characteristics (including policy regimes). Our reduced-form estimates, however, also show substantial variation in pass-through over time within countries—a variation which has received less attention. Pass-through increases over time in some countries, decreases in others, and shows sharp, short-lived movements during some periods in others.

Could this variation in pass-through across time (and possibly across countries) partly reflect the role of economic conditions—the underlying structural shocks behind exchange rate movements? If so, this would support the theoretical literature showing that firms adjust their prices and mark-ups differently after different shocks. This would also imply that the shocks leading to an exchange rate movement can be important in determining the effects on pricing, inflation, and other economic variables.Footnote 1 Although this point is generally understood and has been incorporated in some recent empirical work focussing on an individual country or region, it is usually not explicitly incorporated in empirical papers estimating pass-through and there has been no analysis of the importance of these underlying economic shocks relative to other determinants of pass-through. The limited number of papers that have made some attempt to model the underlying shocks include: Shambaugh (2008), which was the first paper to identify a set of shocks to exchange rates for several countries through long-run restrictions, and more recently Forbes et al. (2018), which develops a more extensive SVAR framework to study shock-dependent exchange rate pass-through in the UK.Footnote 2 Comunale and Kunovac (2017) and Corbo and Di Casola (2018) also apply this latter SVAR framework to selected euro area economies and Sweden, respectively. These SVAR studies all find evidence for the specific country (or region) on which they focus, supporting theoretical work that a given exchange rate movement can be associated with very different price dynamics depending on the underlying shock. None of these papers, however, assesses the relative importance of these shocks for understanding pass-through relative to the importance of the structural variables that are generally the focus of this literature. These frameworks also rely on specific identifying assumptions or country-specific data, which make them difficult to apply to a cross-section of countries.

Do these insights for this limited set of countries apply to a larger and more diverse sample—including emerging markets and countries outside of Europe? Are there empirical regularities across countries in terms of which shocks behind exchange rate movements correspond to larger (or smaller) degrees of pass-through? And how important is the role of these shocks in explaining pass-through relative to the role of the structural variables on which the literature has focused? Answering these questions is more complicated than simply applying the framework used for the UK and European countries to other nations as some of the data used in earlier work are not widely available, and some of the underlying model assumptions may not apply to other countries. This paper therefore attempts to answer these questions by modifying the SVAR framework developed for the UK in Forbes et al. (2018) so that it can be applied to a sample of 26 diverse economies. This large country sample also allows us to address additional questions—such as a comparison of the role of the underlying shocks, relative to standard structural variables, for understanding variations in pass-through across countries and over time.

Our estimates show how different shocks correspond to different degrees of pass-through across the diverse sample, and although certain types of shocks (particularly global shocks) have dissimilar effects across countries, there are certain empirical regularities and consistent findings. For example, monetary policy shocks correspond to a positive correlation between exchange rate and price responses in all countries, and generate larger pass-through effects than the other shocks in most countries. In contrast, domestic demand shocks correspond to a negative response of prices even alongside an exchange rate depreciation, and generate less pass-through than monetary policy shocks in all countries. We also find substantial variation in the importance of different shocks driving exchange rate movements across countries, and especially over time within individual countries. The nature of the shocks driving exchange rate movements can therefore be important in explaining differences in pass-through across countries, and especially over time within countries.

To better highlight the magnitudes and importance of explicitly controlling for the shocks when estimating pass-through, especially in comparison with the previous literature which tends to focus on slow-moving structural determinants, we then estimate a series of cross-sectional and panel regressions and apply the results to individual countries. We explore how important our shock-based framework is for explaining differences in the impact of exchange rate movements on prices in both the cross-section and time-series dimension, including when simultaneously controlling for structural country characteristics previously highlighted in the literature (such as the volatility of inflation and trade openness).Footnote 3

The results suggest that the prevalence of different shocks can help explain the variation in pass-through across individual countries, but is more important for understanding the variation in pass-through over time within individual countries. More specifically, in the cross-section, the role of the shocks fluctuates based on the specification and can be insignificant when simultaneously controlling for structural characteristics. In contrast, in the time-series, the role of the shocks (especially monetary policy shocks) is consistently significant across a range of specifications, even when controlling for a range of structural characteristics (which also continue to be important). The underlying shocks, as well as structural characteristics, are both significant and economically meaningful for understanding changes in pass-through over time.

This shock-based framework used to estimate the effects of exchange rate movements on prices can also be useful to explore a range of other issues. The last section of the paper provides one example: to assess if monetary policy played a greater role in driving exchange rate volatility following the Global Financial Crisis. Over the last decade, many countries have relied heavily on monetary policy to support growth, including the use of unconventional tools. Has this greater reliance on monetary policy caused more volatility in exchange rate movements than in the past? The shock-based analysis suggests that for advanced economies (but not emerging markets), monetary policy has driven a moderately larger share of exchange rate movements than during a comparable period before the crisis. This increased role of monetary policy for exchange rates, however, does not appear to be larger for countries around the effective lower bound (ELB) on interest rates that used unconventional monetary policies (even though these countries had a larger increase in exchange rate volatility). These results provide mixed support for the increased concerns around “currency wars”. Monetary policy may have played a greater role in driving exchange rate movements since the crisis and thereby generated increased spillovers, but it is not clear that this has led to higher exchange rate volatility or that unconventional monetary tools are aggravating these concerns.

The paper concludes that understanding the economic conditions behind exchange rate movements can be important for addressing a range of questions. Models assessing pass-through should not only consider the structure of the economy, but also explicitly account for the shocks underlying exchange rate movements. Central banks, or any institution attempting to forecast inflation, should avoid using historic “rules of thumb” to predict how a given exchange rate movement will pass-through into inflation, and instead directly incorporate the shocks underlying the exchange rate movement into their models.Footnote 4 The importance of this framework for setting monetary policy has begun to be discussed (as pointed out in Cœuré (2017), Bank of England (2015) and Forbes (2015)), but this paper demonstrates its importance for a broad set of countries and shows how this modelling framework can be applied more generally. The contribution of monetary policy to exchange rate movements, and how that role may have changed since the crisis, is important for understanding the political sensitivities around “currency wars” and the associated potential for increased volatility in exchange rates and resultant spillovers.

The remainder of the paper is as follows. Section 2 reports reduced-form estimates of pass-through across countries and over time. Section 3 describes the generalized SVAR model to estimate shock-based determinants of exchange rate pass-through. Section 4 reports results on the role of shocks and country structure in explaining differences in pass-through across countries and over time. Section 5 examines if the role of monetary shocks in driving exchange rate movements has changed since the crisis and what this implies for concerns about “currency wars”. Section 6 concludes.

2 Estimates of Pass-Through Across Countries and Over Time

This section estimates pass-through coefficients for each country in our sample and for different periods using a standard, reduced-form specification. It begins by discussing the sample, data, and methodology. Then it reports estimates of the average rate of pass-through for each country over the full sample, concluding with estimates that vary over time.

2.1 Sample, Data, and Methodology

We focus on a sample of diverse countries from 1990 to 2015 that meet three criteria: have flexible exchange rates, are “small open” economies, and have key data required for the analysis.

First, countries in our sample must be classified as having a de facto floating exchange rate throughout at least the ten years from 2006 to 2015, according to the IMF.Footnote 5 This yields a sample duration of up to 26 years (1990–2015) for countries with a long history of floating exchange rates (such as Australia and Japan) but no shorter than 10 years for countries which adopted floating exchange rates more recently (such as Israel, Romania, and Serbia).

Second, countries must be “small open economies,” in the sense their economic conditions do not affect global variables. This requirement is necessary to satisfy the identification assumptions for our SVAR model used to extract the shocks driving the exchange rate (discussed in Sect. 3). In our base case, this only involves excluding the USA from our sample, although we also examine the impact of removing Japan. China and countries in the euro area were already excluded as they do not meet the criterion of having flexible exchange rates.

The final requirement for our sample is that quarterly data on domestic consumer prices, exchange rates, short-term interest rates, and real GDP are available. The resulting sample of 26 countries includes 11 advanced economies (Australia, Canada, Iceland, Israel, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK) and 15 economies we refer to as “emerging” (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ghana, India, Mexico, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Romania, Serbia, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey and Uruguay). The data sources, definitions, and periods used for each country are listed in “Appendix A”.

In order to obtain pass-through estimates for this sample of advanced and emerging economies, we follow the standard methodology developed in Campa and Goldberg (2005, 2010), and recently updated in Burstein and Gopinath (2014). More specifically, we estimate a distributed lag regression of changes in domestic consumer prices on the following explanatory variables: changes in the trade-weighted exchange rate (contemporaneous to four quarter lags), changes in the trade-weighted export prices of trading partners (contemporaneous to fourth quarter lags), and GDP growth (contemporaneous). The resulting country regressions can be expressed as:

where \(\Delta p_{i,t}\) is the quarterly log change in the domestic consumer price index (CPI) of country i in period t; \(\Delta s_{i,t - n}\) is the quarterly log change in country i’s trade-weighted exchange rate index in period t-n; \(\Delta wxp_{i,t - n}\) is the quarterly log change in country i’s trade-weighted world export prices in period t − n; and \(\Delta gdp_{i,t}\) is the log change in country i’s real GDP.Footnote 6

Exchange rate pass-through in country i is captured by the sum of the coefficients on all lags of the exchange rate, i.e. \(\mathop \sum \nolimits_{n = 0}^{4} \beta_{i,n}\). Equation (1) is estimated using OLS with Newey-West standard errors robust to autocorrelation of lag order of up to eight quarters.

2.2 Reduced-Form Estimates of Pass-Through

Panel (a) of Fig. 1 shows the resulting estimates of “long-sample” pass-through for our sample of advanced and emerging economies over the full sample period from 1990 through 2015 (or as long as possible for each country). The red diamonds show the point estimates from the country-by-country estimates of Eq. (1), and the corresponding blue bars show the 95% confidence bands. The black dashed line running across the graph shows the pass-through coefficient estimated from a panel regression with the entire country sample and controlling for country fixed effects, with the orange shading the corresponding confidence band from this panel regression. Higher estimates imply greater pass-through, i.e. the more prices rise (fall) after a given exchange rate depreciation (appreciation). The interpretation of the point estimates is straightforward: a 0.1 coefficient means that a 1% increase in the exchange rate (1% depreciation) corresponds to a 0.1% increase in the level of consumer prices.

Estimates of “long-sample” and 6-year exchange rate pass-through by country. Notes: The red diamonds depict point estimates of exchange rate pass-through based on Eq. (1), and the blue ranges depict the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Panel (a) plots the estimate using the full sample period for each country, while panels (b) and (c) show the 6-year window estimates. The black dashed lines in panels (b) and (c) correspond to the point “long-sample” estimates for each country shown in panel (a). Note that for some countries the “long-sample” consists of the longest period possible and can include years that are not included in the individual 6-year periods used for the short-term estimates. As a result, the dashed lines may not necessarily correspond to an average of the red diamonds

The figure shows that long-sample pass-through varies substantially across countries, as well as relative to the pass-through estimated for the full sample in the panel regression. It ranges from around 0 in several countries to around 50% in Mexico and 70% in Turkey. The average rate of pass-through for advanced economies is 5% (or 0.05), while the average for the emerging economies is 23% (or 0.23). For many countries, the 95% confidence bands are small, indicating fairly precise estimates, although for some countries with few data points the bands are substantially wider (such as Poland and Romania). Comparing the country-specific to the panel estimates reveals that for a majority of countries in our sample assuming a common pass-through coefficient across countries would result in significantly different estimates than experienced in that country.

Figure 1, panels (b) and (c) also depict the corresponding pass-through coefficients and 95% confidence bands for each country over four 6-year periods: 1992–1997, 1998–2003, 2004–2009, and 2010–2015. The comparison with panel (a) suggests that the long-sample estimates can miss meaningful changes in pass-through over time within individual countries.Footnote 7 This supports results for individual countries showing pass-through can change over time, such as for the UK in Forbes et al. (2018), for Switzerland in Stulz (2007), for the euro area in Comunale and Kunovac (2017) and Cœuré (2017), and for the USA from the 1980s to the 1990s.Footnote 8 In some countries (such as Japan, Switzerland and the UK), pass-through has increased over the sample period, while in other countries (such as Australia, Brazil, and Mexico), pass-through has decreased at some point. In some countries, pass-through spikes in one period and then falls back (such as in Canada and Philippines).

Data for emerging economies over the earlier periods are more limited, and some of the sharpest increases in pass-through in emerging economies correspond to financial or currency crises. To ensure that the focus on these arbitrary 6-year periods does not affect our results, we also estimate Eq. (1) using 7-year, 8-year, and 10-year periods. These time-varying estimates of pass-through also highlight the diversity of experiences across countries, but do not change our main results discussed below.

The long-sample estimates in Fig. 1 vary across countries from around 0% to 70%, with a standard deviation of 17 percentage points. The time variation in the 6-year pass-through estimates for individual countries ranges from substantial (− 5% to 14% for Japan) to very large (− 12% to 49% for Romania). The standard deviation for this time dimension ranges from 2 to 30 percentage points, with an average of 9 percentage points. This confirms that there is meaningful variation in pass-through both across countries and over time.

3 Measuring the Economic Conditions (the “Shocks”)

3.1 The SVAR Model

To understand whether the economic environment (i.e., the shocks) causing exchange rate movements affects the extent of pass-through across countries and over time, we modify the SVAR model developed in Forbes et al. (2018) for the UK so that it can be applied to a set of diverse countries. We adapt the model in two ways. First, we focus on consumer prices instead of import prices, due to the more limited data on import prices available for the broader sample of countries, as well as because consumer prices are the primary focus for forecasts and monetary policy. Second, we adjust the identification of shocks in order to better capture the different ways in which shocks (and especially global shocks) can affect the diverse set of economies.Footnote 9 Building on Sect. 2, we continue to use quarterly data from 1990 (when available) to 2015.

The resulting SVAR model identifies three domestic and three global shocks, each to: monetary policy, demand, and supply. The shocks are identified using a combination of standard sign and zero restrictions, applied to domestic consumer prices, GDP, interest rates, exchange rates, and foreign trade-weighted GDP, foreign consumer prices and foreign interest rates.

Specifically, we assume that only domestic and global supply shocks affect the level of output in the long run. This is consistent with the standard assumption that only changes in technology can affect the productive capacity of an economy in the long run and that prices will adjust to ensure that markets clear.Footnote 10 We also assume that domestic shocks do not affect foreign variables, either on impact or in the long run, which is the common “small open economy” assumption made in the literature.Footnote 11 Instead, only global shocks may have an impact on foreign variables. Next, we impose several short-run sign restrictions on domestic and global shocks. Supply shocks are associated with a negative correlation between GDP and the CPI on impact. Demand shocks are associated with a positive correlation between GDP and the CPI and a counter-cyclical monetary policy response. Positive domestic demand shocks are also associated with an exchange rate appreciation. Monetary policy shocks are identified such that a lower interest rate is associated with a rise in GDP and the CPI, and a depreciation of the nominal exchange rate.Footnote 12 Further details on methodology and identification are in “Appendix B”.

3.2 Overview of SVAR Results

The SVAR estimates show that the response of consumer prices relative to that of the exchange rate, conditional on the shock that drives both, varies meaningfully across shocks. The average responses and ranges across countries are summarized in Fig. 2. The shaded areas show the confidence bands of these mean group estimates, and the orange lines plot the 10th and 90th percentiles of the country-specific estimates. The graphs suggest not only different rates of pass-through, but also different signs, based on why the exchange rate has moved. A 1% depreciation caused by a domestic monetary policy shock (looser monetary policy) corresponds to an increase in consumer prices of just over 0.3% on average across countries after 8 quarters. This is a significantlyFootnote 13 larger average effect than for a comparable depreciation caused by any other type of shock. In contrast, the same depreciation caused by a domestic demand shock (weaker domestic demand) occurs simultaneously with a decrease in consumer prices of about 0.3%. The mean group estimate of this relative consumer price response after a domestic demand shock is significantly lower than the average response associated with all other shocks, apart from global monetary policy shocks. In addition, this negative effect occurs for all countries and is very different than the standard assumption that a depreciation corresponds to higher prices. The other shocks causing currency movements have somewhat smaller effects, and their impact varies across countries, albeit all usually have the typical positive sign.Footnote 14

Cross-country mean group estimate for the response of consumer prices conditional on a 1% exchange rate depreciation, eight quarters after shock. Notes: The blue range depicts the 2 standard error range of median cumulative consumer price responses corresponding to a cumulative exchange rate appreciation of 1% within four quarters caused by different shocks across the 26 countries. The mean group point estimate and standard deviations around it are calculated as in Pesaran (2015), pp. 717–718. The orange lines correspond to the 10th and 90th percentiles of the country-specific median responses. The first, second, and third columns show the estimates after domestic supply, demand, and monetary policy shocks respectively, while the fourth, fifth, and sixth show the estimates after global supply, demand, and monetary policy shocks, respectively

The result that the median ratio between the responses of prices and the exchange rate following domestic monetary policy shocks is higher than that following domestic demand shocks for all countries in our sampleFootnote 15 is noteworthy. Furthermore, the average relative response of prices across countries (as captured by the mean group estimates in Fig. 2) is significantly higher after a domestic monetary policy shock than after a domestic demand shock. These two shocks are the most important determinants of exchange rate movements on average across the countries and years in our sample (explaining 44% of the forecast error variance after eight quarters). These different patterns are not related to changes in foreign marginal costs, as the domestic shocks behind the exchange rate movements should not affect the foreign economies (particularly foreign consumer prices). Instead, these different degrees of pass-through reflect different responses by firms and the other general equilibrium effects from these shocks. For example, if the exchange rate depreciated due to a negative domestic demand shock, foreign exporters would face weaker demand in the domestic market and slower growth in domestic prices and wages, providing less incentive to increase prices in the domestic market (and thereby generating lower pass-through). In contrast, if the exchange rate depreciated due to looser domestic monetary policy, demand conditions in the domestic economy would improve, supporting domestic prices and wages, providing more incentive to increase prices in the domestic market (and thereby generating higher pass-through). These meaningful differences in the effects of domestic demand and monetary policy shocks will feature in the empirical analysis below.

Also noteworthy is that the importance of different shocks behind exchange rate movements can vary meaningfully across countries as well as over time (see Appendix Figs. 7 and 8). For example, in Iceland almost 50% of the exchange rate forecast error variance is explained by domestic monetary policy shocks over the full period, while in Australia domestic demand shocks play an unusually large role (explaining 30% of the variance). Consistent with monetary policy shocks corresponding to higher pass-through, and demand shocks corresponding to less, Iceland has the highest pass-through in the advanced economies (at 22%), and Australia one of the lowest (at about 0%). Similarly, shifting to the time-series dimension, domestic monetary policy shocks have recently played a greater role in explaining currency movements in Korea and Chile; this has corresponded to greater pass-through in both countries (Fig. 1, panels (b) and (c)), as would be expected given the higher pass-through from monetary policy shocks.

While these patterns and correlations are not a formal test of the determinants of pass-through, they highlight how different shocks behind exchange rate movements could play a role in explaining differences in pass-through across countries as well as over time.

4 The Role of Shocks for Pass-Through

This section assesses the role of different shocks (from Sect. 3) and standard structural variables in explaining the variation in pass-through (from Sect. 2) across countries and then over time. It discusses the methodology, applies this methodology to estimate a series of regressions, and then uses these results to evaluate the role of the “shocks” and economic structure in pass-through.

4.1 Methodology

In order to build on previous work examining differences in pass-through across countries, we follow the two-stage regression approach in Campa and Goldberg (2005). More specifically, we regress the OLS estimates of exchange rate pass-through from Sect. 2 on the shock contributions obtained in Sect. 3 plus country characteristics previously highlighted in the literature. When examining the time-series variation, we include country fixed effects in order to control for any time-invariant structural characteristics that could explain cross-country differences in pass-through. Following Campa and Goldberg (2005), we estimate the regressions with weighted (or generalized) least squares, using the inverse of the variance of the estimated pass-through coefficients as weights. This reduces the importance of imprecisely estimated pass-through coefficients.

The academic literature has highlighted a large number of “structural” variables that can explain differences in pass-through across countries. These include a number of nominal measures (such as the average inflation rate, inflation volatility, foreign currency invoicing, and exchange rate volatility), whether the country is an emerging market (which tend to have less well anchored inflation expectations and a shorter history of independent central banks), and variables that capture the economy’s pattern of production in ways that can affect pass-through (such as trade openness, the share of less differentiated goods in imports and domestic market regulation).Footnote 16 We will call these “structural” variables to simplify discussion, although some are only loosely “structural” and may reflect policy choices. Many of these variables are highly correlated,Footnote 17 so that when combined with the limited sample size, it is only possible to include a small number of these controls simultaneously.

Therefore, in the main specifications reported below, we focus on results that include controls for inflation volatility (to capture nominal factors) and trade openness (measured by the share of imports to GDP). These are the variables most often significant when combined with other structural variables. Results with different combinations of a large set of control variables are reported in “Appendix C”. None of the sensitivity tests change the key results discussed below meaningfully.

4.2 Regression Results: The Role of Shocks and Structure in Explaining Pass-Through

We use this methodology to explore the role of the shock contributions and structural variables in explaining the cross-sectional and then the time-series variation in pass-through. Table 1 begins by estimating the role of the six different “shock” measures in explaining the variation in pass-through across countries (columns 1–6). The explanatory variables capturing shock contributions come from the SVAR forecast error variance decomposition of the exchange rates in our sample and are plotted in Appendix Fig. 7. The coefficients on the domestic shocks have the expected signs (with positive pass-through after each of the shocks except for domestic demand, for which the coefficient is negative). The coefficient for domestic demand shocks is also significant.

Column 7 then includes two of these shock variables simultaneously (for domestic demand and monetary policyFootnote 18) as well as two variables to capture the “structure” of the economy: a proxy for nominal characteristics (inflation volatility) and for production patterns (trade openness). The shock contributions become insignificant (although continue to have the expected signs), while the volatility of inflation has a positive and significant relationship with pass-through. These results in columns 1–7 are typical of a range of specifications with different control variables: the shock variables can be significantly correlated with the extent of pass-through (especially demand shocks) and generally have the expected sign, but their significance varies based on which other pass-through determinants are included. The insignificance of some of the shocks (such as for domestic supply or the global shocks) is not surprising given the heterogeneous relationship between these shocks and pass-through across countries (as shown in Fig. 2, pass-through can be either positive or negative based on the country). The coefficient on inflation volatility is significant in almost all specifications—even when other controls for nominal and structural variables are included.

Next, we repeat this analysis in Columns 8–14, except now assess the role of the six shocks and structural variables in explaining the variation in pass-through over time within countries, focusing on the four 6-year periods reported in panels (b) and (c) of Fig. 1.Footnote 19 The coefficients on the shock variables continue to have the expected signs and are more often significant. Demand shocks continue to be associated with significantly lower pass-through, while monetary policy shocks are now associated with significantly higher pass-through. Moreover, the coefficient on the monetary policy shock continues to be significant when controls for the structural variables are simultaneously included (column 14). This suggests that when monetary policy shocks explain a greater portion of an exchange rate movement at a specific time, pass-through tends to be significantly higher. The role of structural variables—such as inflation volatility and trade openness—are also consistently significant, indicating a role for structural variables as well as shocks in explaining changes in pass-through over time.

To check the robustness of these results and better understand the time frame over which the shocks seem to matter for pass-through, we perform a number of tests. We estimate the regressions using: different specifications to obtain the reduced-form pass-through coefficients on the left-hand side; different identification strategies and sign restrictions for the SVAR; excluding the 2008 crisis; different combinations of a larger set of structural variables; different measures of monetary policy; different treatment of commodity importers and exporters; and adjustments for VAT changes. All of these extensions are summarized in “Appendix C” and do not change the key results discussed above.

We also repeat the analysis for regressions with pass-through coefficients estimated over 7-, 8-, and 10-year windows, as well as with 6-year rolling windows, so that the results are not influenced by different cut-off dates.Footnote 20 Inflation volatility remains significant in each of these variants, while the significance of trade openness (as well as other structural variables included in the sensitivity tests) fluctuates based on the window length. Among the shock-based variables, the monetary policy shock remains significant in the regressions using changes in the rolling coefficients, as well as for the non-overlapping 7- and 8-year periods. The only timing conventions in which shock variables are no longer significant is the non-overlapping 10-year windows. This is not surprising as this longer window is closer to the “long-sample” pass-through estimates, for which the nature of the shocks driving the exchange rate movement appears to be less important.

Overall, these results suggest that the shocks behind an exchange rate movement, and especially the prevalence of monetary policy shocks, are an important determinant of changes in pass-through over time, even after controlling for structural variables. Exchange rate movements caused by monetary policy shocks correspond to significantly higher rates of pass-through. Structural variables also play a role in explaining pass-through over time, especially inflation volatility and trade openness. In addition, the importance of the underlying shocks increases as the window over which one estimates pass-through decreases. This suggests that the nature of the shocks behind an exchange rate movement is more important for understanding short-term variations in pass-through for a given country, while the structural variables appear to be more important in explaining pass-through over longer periods and across countries.

4.3 The Magnitudes: The Role of Shocks and Structure in Explaining Pass-Through

To put these estimates in context, and better understand the relative importance of the structural and shock variables, we use the estimates from Table 1 to calculate the contribution of “shocks” and “structure” to pass-through for each country. We begin with the cross-section dimension and then consider the time-series.

To capture the role of the “shock” and “structure” variables in explaining differences between each country’s average rate of pass-through with sample averages, we apply the estimates from Table 1 (column 7) to explain the difference between a country’s “long-sample” pass-through and the average pass-through across the countries in our sample. Figure 3 shows the resulting contribution of the different structure and shock variables. These comparisons suggest that although the role of the shocks can be economically meaningful, it tends to be smaller than for the structural variables. For example, consider the case of Australia. It has one of the lowest rates of pass-through in the sample (Fig. 1, panel (a)). The contributions of demand shocks (which generate lower pass-through and are more prevalent in Australia) and monetary policy shocks (which generate higher pass-through and are less prevalent in Australia) to currency movements account for just under 4 pp of Australia’s 15 pp shortfall relative to average pass-through in the sample. In contrast, lower inflation volatility (which corresponds to lower pass-through) accounts for almost 11 pp of the shortfall and therefore plays a greater role than the shocks in explaining Australia’s lower pass-through.

Determinants of “long-sample” pass-through. Note: The black diamonds depict country-specific pass-through estimates in percentage point deviation from the cross-country average. The shaded grey area is the percentage point deviation explained by cross-country differences in the importance of the two shock variables (for domestic monetary policy and domestic demand) and the shaded blue is the percentage point deviation explained by the two structural variables (inflation volatility and trade openness)

Next, shifting to the time-series dimension, consider four countries with different geo-economic characteristics and different patterns of pass-through over time: Australia, Sweden, Korea, and Mexico. We apply the estimated coefficients for each of the significant variables from Table 1, Column 14 to illustrate the importance of shock and structural variables for the time variation of pass-through within each country.Footnote 21 Fig. 4 shows a meaningful role for both the prevalence of monetary policy shocks and structural variables (proxied by inflation volatility and trade openness) in explaining the differences in pass-through across the 6-year windows. In some periods, the prevalence of monetary policy shocks can play an even more important role than the structural variables in explaining these deviations in pass-through—such as in Sweden from 2004 to 2009, when monetary policy shocks accounted for 2.7 pp of the 4.2 pp shortfall in pass-through relative to the average for Sweden over the full period. This important role for the shock variables, however, is more typical in advanced economies than in emerging markets. The results for Mexico are typical of the latter group, with inflation volatility generally more important than monetary policy shocks in explaining deviations in inflation over most periods. This is not surprising, as inflation volatility tends to vary more over time for emerging markets than advanced economies.

Determinants of the deviation from average country-specific pass-through, selected countries. Note: The figure shows the percentage point deviation of estimated pass-through from the country average (black diamonds) and the estimated contribution from inflation volatility, trade openness, and the monetary policy shock variable

5 Exchange Rate Volatility, Monetary Policy, and Currency Wars

The shock-based framework developed above for understanding exchange rate movements is useful to understand not only how exchange rate movements pass-through to inflation, but also a range of other issues. This section provides a very different example of how this framework can be applied—to explore if the role of monetary policy for exchange rate movements has changed since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). The analysis in Sect. 3 showed that monetary policy shocks have been the most important driver of exchange rate movements—explaining 28% of the variation in exchange rate movements in our sample over the full period from 1990 to 2015. The analysis also showed, however, that the role of different shocks can vary over time within individual countries (see Fig. 4). If monetary policy is having a greater impact on exchange rates than in the past, this could aggravate concerns around “currency wars” and provide insights useful for the policy debate about the international spillovers from monetary policy.

There are a number of reasons why the impact of monetary policy on the exchange rate could have changed since the GFC. Changes in monetary policy (such as 25 bp change in the policy rate) could have a larger impact when rates are at today’s low levels if it is the percent change in rates, rather than the change, which is important for relative returns and capital flows. This effect could be aggravated in today’s environment when there is less divergence in policy interest rates across major financial centres (as shown in Jordà and Taylor 2019). Tighter prudential and macroprudential regulation, which have played an important role in reducing the volume of cross-border banking flows, could have reduced liquidity so that changes in monetary policy have greater effects on relative prices (i.e. the exchange rate).Footnote 22 When monetary policy is adjusted using unconventional tools, potentially in conjunction with more conventional tools, it could also have different effects on the exchange rate than the more traditional adjustments in just policy interest rates or reserve levels.Footnote 23

Whether monetary policy since the GFC (including unconventional monetary policy used at the effective lower bound, or ELB) has had a larger effect on exchange rates than comparable adjustments in monetary policy before the GFC is still an open question. This section uses the shock-based framework developed in Sect. 3 in order to address three related questions. First, has exchange rate volatility in different groups of countries changed since the crisis? Second, has the role of monetary policy shocks in driving this exchange rate volatility changed since the crisis? Finally, what does this imply for the debate on currency wars and global spillovers? Each portion of the analysis explores whether the results vary between advanced economies and emerging markets, as well as between countries which have had interest rates near their lower bounds (and often used unconventional policy tools) relative to those which have not been constrained by the lower bound. A better understanding of these issues will be more important in the future as the decline in the global neutral interest rate suggests that countries are more likely to be constrained by the effective lower bound and rely more heavily on unconventional policy tools in the future.

5.1 Exchange Rate Volatility: Pre- and Post-Crisis

In our sample of 26 advanced economies and emerging markets covering the period 1990q1–2015q4 (discussed in Sect. 2), the average absolute percent change in quarterly exchange rates is 2.84% (with a standard deviation of 3.44 pp). Not surprisingly, exchange rate volatility is larger for emerging markets (with an average absolute percent change of 3.23% and standard deviation of 3.86 pp) compared to that for advanced economies (with an average percent change of 2.39% and standard deviation of 2.81 pp). Also not surprisingly, exchange rate volatility spiked during the peak of the GFC, with the average absolute percent change in quarterly exchange rates reaching 4.66% in 2008–2009 (with a standard deviation of 4.77 pp). This volatility in exchange rates can have significant effects on a range of economic variables.

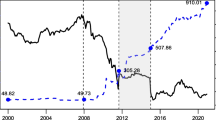

In order to test if exchange rate volatility has changed since the GFC, we exclude the years immediately around the crisis and focus on two 6-year windows: 2001q1–2006q4 (the “pre-crisis window”) and 2010q1–2015q4 (the “post-crisis window”). As shown in Fig. 5, exchange rate volatility (as measured by the average absolute percent change in quarterly exchange rates) has fallen, from 2.93% pre-crisis to 2.39% post-crisis. A T test shows that this fall in the magnitude of average quarterly exchange rate movements between the pre-crisis and post-crisis periods is significant at the 95% level. This reduction in volatility, however, is entirely driven by reduced volatility in emerging markets. As shown in the middle of the figure, exchange rate volatility in emerging markets has fallen significantly (from 3.68% to 2.65%), but remained constant across periods at 2.04% for advanced economies.

Exchange rate volatility pre- and post-crisis in different country groups. Note: Exchange rate volatility measured as the average percent change in the quarterly trade-weighted exchange rate of each country in the group. Pre-crisis is the period 2001q1–2006q4, and post-crisis is 2010q1–2015q4. Countries are defined as being at the ELB (effective lower bound) if their policy interest rate falls to 0.5% or less

Does this stable volatility in exchange rates in advanced economies mask differences across countries or groups of countries? For example, did countries with monetary policy interest rates near the lower bound (ELB) experience an increase or decrease in volatility? To test this, we divide the sample of advanced economies into those where interest rates were around the ELB at some point in the period (defined as the policy interest rate falling to 0.5% or less) and those which were not. The countries at the lower bound are: Canada, Israel, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK. The right side of Fig. 5 suggests that exchange rate volatility has increased in the post-crisis period for countries that were at the lower bound (from 1.74% to 2.01%), but decreased for other advanced economies that were not at the lower bound (from 2.36% to 2.08%). Moreover, this increase in exchange rate volatility for countries at the ELB in the post-crisis period is moderately significant. If we estimate a panel regression of quarterly exchange rate volatility for each of the groups of countries below, the post-crisis dummy for advanced economies near the ELB is positive (and significant at the 88% level).

These average differences, however, could be driven by sharp changes in one or two countries—especially given the small sample. A closer look at changes in exchange rate volatility in the pre- and post-crisis windows for each country suggests that these average results are not driven by outliers. Of the six advanced economies at the lower bound, five experienced an increase in exchange rate volatility in the post-crisis window (with Canada as the only exception). The increase was sharpest in Switzerland, where volatility almost doubled. Of the five advanced economies not at the lower bound, only one experienced an increase in exchange rate volatility of more than 0.1 pp in the post-crisis window (Australia).

5.2 The Role of Monetary Policy: Pre- and Post-Crisis

How much of these changes in exchange rate volatility since the GFC is associated with changes in the role of monetary policy on currency movements? And for advanced economies, what can we learn from looking separately at countries constrained by the lower bound on interest rates?

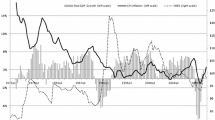

To shed light on these questions, we return to the analysis in Sect. 3, which used the SVAR framework to estimate the contributions of six different shocks (to domestic and global monetary policy, demand and supply) to exchange rate movements for our sample of 26 countries from 1990 to 2015. Then we calculate the average share of quarterly exchange rate movements driven by each type of shock, over the same 6-year windows used above: pre-crisis (2001q1–2006q4) and post-crisis (2010q1–2015q4). Figure 6 shows the resulting estimates of the role of monetary shocks for the different groups of countries in the two periods. It focuses on the large exchange rate movements that are the most important for policymakers by weighting each quarterly movement according to its magnitude.

The graph shows some noteworthy patterns. Monetary policy shocks play an important role in driving the exchange rate in both emerging economies and in advanced economies. This role of monetary policy shocks in driving exchange rate movements is basically the same for emerging markets in the pre-crisis period relative to the post-crisis period, but has increased moderately for the advanced economies in our sample, particularly for those not near the ELB. In the pre-crisis period, the different groups of countries considered did not experience a significantly different role of monetary policy shocks in driving their exchange rates. In the post-crisis period, however, the group of advanced economies that were not constrained by the lower bound experienced a significantly higher proportion of exchange rate movements driven by monetary policy shocks.Footnote 24 This result is consistent with monetary policy playing a greater role for exchange rate movements in advanced economies since the crisis, especially in those countries not constrained by the lower bound.Footnote 25

These results are robust when we use different measures of monetary policy than the policy rates, such as market-based forward rates at horizons of up to 1 year, or shadow short rates extracted from the whole yield curve using affine term structure models (both of which should better capture changes in unconventional monetary policy).Footnote 26 Using these shadow rates does not imply a greater post-crisis role for monetary policy in the economies constrained by the ELB. These sensitivity tests provide tentative evidence that unconventional policies have not had a larger contribution to exchange rate movements than other types of monetary policy. A thorough analysis of the role of unconventional policy measures and their link to exchange rate volatility, however, requires measures of unconventional policies for more countries across more time variation than currently available in our sample.

5.3 Implications for Currency Wars and International Spillovers

What does this imply for concerns that monetary policy is having a greater impact on exchange rates than in the past? If monetary policy is driving greater currency volatility, this could create substantial challenges, especially in emerging markets. These concerns were serious enough that they were the topic of a 2013 G-7 meeting and discussed in the resulting statement establishing ground rules to address the potential effects on exchange rates of different monetary policy tools.Footnote 27

The series of results presented above, however, provides mixed evidence to justify increased concerns about how monetary policy may be driving “currency wars”. The role of monetary policy in driving exchange rate movements appears to have increased moderately for advanced economies since the crisis. This increase was more pronounced in advanced economies not constrained by the ELB, but was not associated with increased exchange rate volatility. Even for advanced economies near the ELB, which experienced a significant increase in exchange rate volatility in the post-crisis period, the role of monetary policy shocks only increased modestly and was still lower than the role for other advanced economies. This evidence does not support the notion that monetary policy used by countries close to the ELB drove a disproportionate share of exchange rate volatility and is responsible for increased concerns about “currency wars”.

These results provide a simple example of how decomposing exchange rate movements into their underlying shocks can be useful to provide insights into a range of questions. In this case, the framework provides moderate support for arguments that exchange rates have been driven more by monetary policy since the crisis in advanced economies than before, but little support for arguments that this has been associated with higher exchange rate volatility and is a prominent economic factor driving concerns about “currency wars”.

6 Conclusions

This paper develops a framework for a cross-section of countries that can estimate the role of economic conditions (the shocks) causing the exchange rate to move. It shows how this framework can be used to address a range of questions, focussing on its use to estimate the pass-through of exchange rate movements to inflation, and to investigate the relative importance of “shocks” versus longer-term structural characteristics for pass-through. It also shows how this framework can help understand other topical questions, using an example of whether changes in the role of monetary policy since the GFC have led to changes in exchange rate volatility.

The results suggest that although structural characteristics are important for understanding pass-through (in the cross-section and time-series), the shocks behind exchange rate movements can also be important, particularly the role of monetary policy shocks for understanding changes in pass-through over time within a given country. Exchange rate movements caused by monetary policy shocks correspond to significantly higher pass-through, while there is some evidence (albeit weaker) that those caused by demand shocks correspond to lower pass-through. These results support previous evidence for the UK, but suggest that these insights also apply to a more diverse sample of economies.

The results also suggest that although exchange rate volatility has not increased in advanced economies in the post-crisis period, monetary policy shocks have played a greater role in driving exchange rate movements, particularly in countries that are not close to the lower bound on interest rates. The group of advanced economies that were constrained by the lower bound at some point since the GFC have experienced higher exchange rate volatility, but the role of monetary policy shocks in explaining this volatility increased somewhat less and was overall less important. These results are helpful to better inform the debate around “currency wars” and the corresponding role of monetary policy in advanced economies. All of these results should be interpreted cautiously, however, given the small sample and limited experience with unconventional monetary policy. If more countries approach or remain near their lower bounds in the future—making unconventional monetary policy tools become more “conventional”—more observations will be available to test these relationships formally.

Notes

This literature includes Bils (1987), Dornbusch (1987), Krugman (1987), Klein (1990), Rotemberg and Woodford (1999), and more recently Corsetti et al. (2009) and Gilchrist and Zakrajsek (2015). Nakamura and Steinsson (2013) discuss the link between the micro- and macro-literature. For discussion of the implications for pass-through, see Burstein and Gopinath (2014), Campa and Goldberg (2005) and Ito and Sato (2008).

The shock-based approach in Shambaugh (2008) did not receive the attention it deserved, and its insights were not incorporated in subsequent research and estimation of pass-through. The framework developed in Forbes et al. (2018) improves on Shambaugh (2008) in three ways: (1) uses different shocks that are more closely linked to the theoretical literature and more straightforward to interpret for empirical analysis; (2) uses advances in SVAR methodology to better identify these richer shocks behind exchange rate fluctuations and better mitigate concerns with weak identification in SVAR models with long-run restrictions; and (3) considers the effects of these shocks on a broader set of variables—including interest rates and foreign export prices. These improvements link the empirical model more closely to the theoretical literature and make the framework more applicable and usable for forecasting key economic outcomes such as inflation.

See “Using rules of thumb for exchange rate pass-through could be misleading” by Forbes (2015), voxeu.org, 12 February 2016.

The de facto floating exchange rate regime categories in the IMF’s classification are “floating” and “free floating”. See the IMF’s 67th Annual Report on Exchange Rate Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions for 2015. Switzerland is the one country in our sample that is not continuously classified as “floating” since 2006 due to the ceiling on the Swiss franc from September 2011 to January 2015, but excluding it from the analysis does not impact the key results.

The last term is included to control for changes in domestic conditions which could affect prices directly rather than just through the exchange rate. We also estimated 27 variations of Eq. (1), including with no control for GDP growth and different controls (such as short-term interest rates, oil prices, and one to four lags of the dependent variable). The results were generally stable and similar to the baseline. See “Appendix B” in Forbes et al. (2017).

Despite the short sample periods of only 6 years, the differences in the estimated pass-through coefficients over these short periods are statistically significant and economically meaningful in some cases but not always. More specifically, the estimated pass-through coefficient for Japan, Korea, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Poland, Romania, South Africa, Turkey and Uruguay differ significantly either between some of the 6-year windows or relative to the “long-sample” pass-through estimate (or both).

In particular, Forbes et al. (2018) only identifies global temporary and permanent shocks, while we add a third global shock (for monetary policy). This greater diversity of global shocks is important when extending the model to diverse countries to capture different monetary policy regimes and different effects of global commodity prices.

For additional references and evidence on these assumptions, see the model and discussion in Forbes et al. (2018).

At the 95% confidence level as indicated by the 2 standard error confidence bands of the mean group estimates in Fig. 2.

It is not surprising that global shocks have varied effects on different countries in our sample. Commodity and oil price movements (which are correlated with global demand and supply shocks) are an important driver of the exchange rate for some countries—but in some cases show positive correlations and in others negative, based on whether the country is a commodity importer or exporter. We allow for these heterogenous effects in the model by imposing no restrictions on the impact of global shocks on domestic prices, interest rates or the exchange rate in both the short and long run.

More precisely, the median pass-through for individual countries four quarters after the shock is negative for all countries; the ratio remains negative eight quarters after the shock for all countries apart from Mexico (where pass-through is negative at horizons of 1 to 7 quarters but switches sign in the eight quarter). At a horizon of eight quarters after the shock, the effect is significantly negative at the 68% confidence level for 14 out of the 26 countries in our sample; four quarters after the shock, the effect is significantly negative at the 68% confidence level for 19 of 26 countries.

These two shocks are not only most often significant, but as discussed in Sec. 3, explain the largest share of the variance of exchange rate movements and have consistently different effects on pass-through across the sample.

The explanatory variables are also re-calculated to correspond to the 6-year windows over which the pass-through coefficients are estimated. The shock contributions, for instance, are now calculated as the sum of squared contributions of each shock to the historical decomposition of the exchange rate divided by the sums of squared contributions of all shocks within each 6-year window. The structural control variables in the baseline specification in Table 1 are the standard deviation of quarterly inflation and the average share of imports in GDP over the respective 6-year windows.

See Forbes et al. (2017) for a subset of these results.

Including the impact of demand shocks has no meaningful impact as the relevant coefficient is almost 0.

Possible explanations are that unconventional policies work more through the term premium (and therefore long-term securities) and/or are interpreted as a longer-term commitment than conventional policy. See Brainard (2017) for a summary of arguments, and see Neely (2015), Glick and Leduc (2015), Curcuru (2017), Ferrari et al. (2017) and Hatzius et al. (2017) for analysis if the effects of unconventional monetary policy are different than conventional policies.

When estimating a panel regression of quarterly contributions of monetary policy shocks to exchange rate movements for the pre-crisis period, and inserting a dummy for each group of countries considered subsequently, none of these are found to be significant. But for the post-crisis period, the dummy for advanced economies not constrained by the lower bound on interest rates is significant at the 95% level.

It is worth noting that some of these patterns change when giving equal weight to all quarterly exchange rate movements, regardless of their size. In this case, the share of all exchange rate movements driven by monetary policy shocks has increased more since the crisis, but this is driven by emerging markets and countries not at the ELB.

The short-term market-based rates we experimented with were the 3-month, 3-month and 6-month, 6-month forward interbank rates. We used two different measures of shadow interest rates: by De Rezende and Ristiniemi (2018) for Sweden and the UK; and by Krippner (2016) for the UK, Switzerland, and Japan.

See Group of Seven (2013), “Statement by G7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors”, February 12, available at: www.g8.utoronto.ca/finance/fm130212.htm.

The main differences between this framework and that in Forbes et al. (2018a, b) are: we include more foreign variables to identify a set of well-defined global shocks alongside the domestic shocks, and that we exclude import prices from the SVAR. Unfortunately, there are not sufficient, reliable data on import prices over the time-series needed to estimate the model with import prices for the larger set of countries. We also do not allow for exogenous shocks to the exchange rate, as it is no longer possible to identify this shock with only four domestic variables.

The technical details of the estimation are identical to those in Forbes et al. (2018a, b) and described in its "Appendix A".

While sufficient to identify the desired shocks, this set-up relies exclusively on long-run restrictions to differentiate domestic supply shocks from other domestic shocks. Long-run restrictions can lead to weak identification when imposed on relatively short sample periods (see Pagan and Robertson 1998; Faust and Leeper 1997 and Christiano 2007), so we retain the sign restrictions on CPI in our preferred baseline model in the main text.

This means excluding 10 quarterly observations, since using the first two quarters of 2010 requires using the last quarters of 2009 as explanatory variables given our two-lag VAR model.

We include the additional dummies in the cross-section and 6-year windows. The commodity exporters (importers) dummy is based on UNCTAD data (from 1995 to 2015) with commodity exporters (importers) defined as being a net exporter (importer) over the relevant period and commodities defined as SITC 0 + 1+2 + 3+4 + 68.

References

Ahnert, Toni, Kristin Forbes, Christian Friedrich, and Dennis Reinhardt, 2019, Macroprudential FX Regulations: Shifting the Snowbanks of FX Vulnerability? NBER Working Paper No. 25083.

Amiti, Mary, Oleg Itskhoki and Josef Konings, 2016, International Shocks and Domestic Prices: How Large Are Strategic Complementarities? NBER Working Paper No. 22119, March.

Bank of England. 2015. Inflation Report, November. London: Bank of England.

Berger, David and Joseph Vavra, 2015, Volatility and Pass-Through, NBER Working Paper, No. 19651, May.

Bils, Mark. 1987. The Cyclical Behavior of Marginal Cost and Price. American Economic Review 77(5): 838–855.

Binning, Andrew, 2013, Underidentified SVAR Models: A Framework for Combining Short and Long-Run Restrictions with Sign-Restrictions, Norges Bank Monetary Policy Working Paper, No. 14.

Blanchard, Olivier, and Danny Quah. 1989. The Dynamic Effects of Aggregate Demand and Supply Disturbances. The American Economic Review 79(4): 655–673.

Brainard, Lael, 2017, Cross-Border Spillovers of Balance Sheet Normalization, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System speech, given in New York. Available at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/brainard20170711a.htm.

Burstein, Ariel, and Gita Gopinath, 2014, International Prices and Exchange Rates, in Handbook of International Economics, 4th Ed., No. 4, pp. 391–451.

Campa, José, and Linda Goldberg. 2005. Exchange Rate Pass-Through into Import Prices. The Review of Economics and Statistics 87(4): 679–690.

Campa, José, and Linda Goldberg. 2010. The Sensitivity of the CPI to Exchange Rates: Distribution Margins, Imported Inputs, and Trade Exposure. Review of Economics and Statistics 92(2): 392–407.

Carrière-Swallow, Yan, and Luis Felipe Céspedes. 2013. The Impact of Uncertainty Shocks in Emerging Economies. Journal of International Economics 90(2): 316–325.

Carrière-Swallow, Yan, Bertrand Gruss, Nicolas Magud and Fabian Valencia, 2016, Monetary Policy Credibility and Exchange Rate Pass-Through, IMF Working Paper, No. 16/240.

Caselli, Francesca and Agustin Roitman, 2016, Non-Linear Exchange Rate Pass-Through in Emerging Markets, IMF Working Paper, No. 16/1.

Choudhri, Ehsan, and Dalia Hakura. 2006. Exchange Rate Pass-Through to Domestic Prices: Does the Inflationary Environment Matter? Journal of International Money and Finance 25(4): 614–639.

Christiano, Lawrence, Eichenbaum, Martin, and Vigfusson, Robert, 2007, Assessing Structural VARs, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2006, Vol. 21, National Bureau of Economic Research Inc., pp. 1–106.

Cœuré, Benoit, 2017, The Transmission of the ECB’s Monetary Policy in Standard and Non-Standard Times, Speech given in Frankfurt am Main on 11 September.

Comunale, Mariarosaria and Davor Kunovac, 2017, Exchange Rate Pass-Through in the Euro Area, ECB Working Paper, No. 2003, January.

Corbo, Vesna and Paola Di Casola, 2018, Conditional Exchange Rate Pass-Through: Evidence from Sweden, Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper, No. 352.

Corsetti, Giancarlo, Luca Dedola, and Sylvain Leduc. 2008. High Exchange-Rate Volatility and Low Pass-Through. Journal of Monetary Economics 55(6): 1113–1128.

Corsetti, Giancarlo, Luca Dedola, and Sylvain Leduc. 2009. Optimal Monetary Policy and the Sources of Local-Currency Price Stability, International Dimension of Monetary Policy edited by Jordi Gali and Mark Gertler, Chicago University Press, pp. 319-367.

Curcuru, Stephanie, 2017, The Sensitivity of the U.S. Dollar Exchange Rate to Changes in Monetary Policy Expectations, Federal Reserve Board IFDP Notes, 22 September.

De Rezende, Rafael and Annuka Ristiniemi, 2018, A Shadow Rate Without a Lower Bound Constraint, Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper Series, No. 355.

Devereux, Michael, Ben Tomlin and Wei Dong, 2015, Exchange Rate Pass-Through, Currency of Invoicing and Market Share, NBER Working Paper, No. 21413, July.

Dornbusch, Rudiger. 1987. Exchange Rates and Prices. American Economic Review 77: 93–106.

Erceg, Christopher, Christopher Gust, and Luca Guerrieri. 2005. Can Long-Run Restrictions Identify Technology Shocks? Journal of the European Economic Association 3(6): 1237–1278.

Faust, John, and Eric Leeper. 1997. When Do Long-Run Identifying Restrictions Give Reliable Results? Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 15(3): 345–353.

Ferrari, Massimo, Jonathan Kearns, and Andreas Schrimpf. 2017. Monetary Policy’s Rising FX Impact in the Era of Ultra-Low Rates, BIS mimeo.

Forbes, Kristin, 2015, Much Ado About Something Important: How Do Exchange Rate Movements Affect Inflation, Speech given at the Money, Macro and Finance Research Group Annual Conference in Cardiff on September 11 and available at: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/speeches/2015/839.aspx.

Forbes, Kristin, Ida Hjortsoe, and Tsvetelina Nenova, 2017, Shocks versus Structure: Explaining Differences in Exchange Rate Pass-Through across Countries and Time, Bank of England External MPC Working Paper, No. 50.

Forbes, Kristin, Dennis Reinhardt and Tomasz Wieladek, 2017, The Spillovers, Interactions, and Unintended Consequences of Monetary and Regulatory Policies, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 85, pp. 1-22, January.

Forbes, Kristin, Ida Hjortsoe, and Tsvetelina Nenova. 2018. The shocks matter: Improving our Estimates of Exchange Rate Pass-Through. Journal of International Economics 114: 255–275.

Gagnon, Joseph, and Jane Ihrig. 2004. Monetary Policy and Exchange Rate Pass-Through. International Journal of Finance & Economics 9(4): 315–338.

Gali, Jordi. 1999. Technology, Employment, and the Business Cycle: Do Technology Shocks Explain Aggregate Fluctuations? The American Economic Review 88(1): 249–271.

Gilchrist, Simon, and Egon Zakrajsek. 2015. Customer Markets and Financial Frictions: Implications for Inflation Dynamics. Jackson Hole: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Symposium.

Glick, Reuven, and Sylvain Leduc, 2015, Unconventional Monetary Policy and the Dollar: Conventional Signs, Unconventional Magnitudes, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper, 2015-18.

Gopinath, Gita, 2015, The International Price System, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Symposium 2015, Jackson Hole, pp. 71-150.

Gopinath, Gita, Oleg Itskhoki, and Roberto Rigobon. 2010. Currency Choice and Exchange Rate Pass-Through. American Economic Review, American Economic Association 100(1): 304–336.

Gust, Christopher, Sylvain Leduc, and Robert Vigfusson. 2010. Trade Integration, Competition, and the Decline in Exchange-Rate Pass-Through. Journal of Monetary Economics 57(3): 309–324.

Hatzius, Jan, Sven Stehn, Nicholas Fawcett and Karen Reichgott, 2017, Policy Rate vs. Balance Sheet Spillovers, Goldman Sachs Economics Research, Global Economics Analyst, July 28.

Ito, Takatoshi, and Kiyotaka Sato. 2008. Exchange Rate Changes and Inflation in Post-Crisis Asian Economies: VAR Analysis of the Exchange Rate Pass-Through. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 40(7): 1407–1438.

Ito, Hiro and Kawai, Masahiro, 2015, Trade Invoicing in Major Currencies in the 1970s–1990s: Lessons for Renminbi Internationalization, mimeo.

Jasová, Martina, Richhild Moessner and Elod Takáts, 2016, Exchange Rate Pass-Through: What Has Changed Since the Crisis? BIS Working Paper, No. 583.

Jordà, Òscar and Alan Taylor, 2019, Riders on the Storm, Paper prepared for the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Policy Symposium, Challenges for Monetary Policy, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 22–24.

Klein, Michael. 1990. Macroeconomic Effects of Exchange Rate Pass-Through. Journal of International Money and Finance 9(4): 376–387.

Krippner, Leo, 2016, Documentation for Measures of Monetary Policy, mimeo, Reserve Bank of New Zealand, 13 July.

Krugman, Paul, 1987, Pricing to Market When the Exchange Rate Changes, in Real-Financial Linkages among Open Economies, edited by Sven W. Arndt and J. David Richardson, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press.

Liu, Philip, Haroon Mumtaz, and Angeliki Theophilopoulou, 2011, International Transmission of Shocks: A Time-Varying Factor-Augmented VAR Approach to the Open Economy, Bank of England Working Paper, No. 425.

Marazzi, Mario, Nathan Sheets, Robert J. Vigfusson, Jon Faust, Joseph Gagnon, Jaime Marquez, Robert F. Martin, Trevor Reeve, and John Rogers, 2005, “Exchange rate pass-through to U.S. import prices: some new evidence,” International Finance Discussion Papers, No. 833, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Nakamura, Emi, and Jón Steinsson. 2013. Price Rigidity: Microeconomic Evidence and Macroeconomic Implications. Annual Review of Economics 5: 133–163.

Neely, Christopher. 2015. Unconventional Monetary Policy Had Large International Effects. Journal of Banking & Finance 52: 101–111.

Pagan, Adrian, and John Robertson. 1998. Structural Models of the Liquidity Effect. The Review of Economics and Statistics 80(2): 202–217.

Parker, Miles and Wong, Benjamin, 2014, Exchange Rate and Commodity Price Pass-Through in New Zealand, Reserve Bank of New Zealand Analytical Notes, March.

Pesaran, M. Hashem, 2015, Time Series and Panel Data Econometrics, Oxford University Press, ISBN-13: 9780198736912.

Rotemberg, Julio, and Michael Woodford, 1999, The Cyclical Behavior of Prices and Costs, in Handbook of Macroeconomics, eds. John B. Taylor and Michael Woodford, pp. 1051–135.

Rubio-Ramirez, Juan, Daniel Waggoner, and Tao Zha. 2010. Structural Vector Autoregressions: Theory of Identification and Algorithms for Inference. The Review of Economic Studies 77(2): 665–696.

Shambaugh, Jay. 2008. A New Look at Pass-Through. Journal of International Money and Finance 27: 560–591.

Stulz, Jonas. 2007. Exchange Rate Pass-Through in Switzerland: Evidence from Vector Autoregressions, 4. No: Swiss National Bank Economic Studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ines Nicole Lee for excellent research assistance. The authors are also grateful to Philippe Martin and Robert Kollmann for insightful discussions and to Ambrogio Cesa-Bianchi, Roland Meeks, Marek Raczko and participants at conferences and seminars at the Bank of England, European Central Bank, International Monetary Fund, and Riksbank, for helpful comments and further thank for input from Linda Tesar and two anonymous referees. The views in this paper do not represent the official views of the Bank of England or its Monetary Policy Committee. Any errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix to “International Evidence on Shock-Dependent Exchange Rate Pass-Through”

Appendix to “International Evidence on Shock-Dependent Exchange Rate Pass-Through”

1.1 Appendix A: Data Sources and Sample Periods

1.2 Appendix B: SVAR Methodology and Country-Specific Results

1.2.1 Methodology

We modify the methodology developed in Forbes et al. (2018a, b) to derive shock-dependent estimates of pass-through for each of the 26 countries for which we computed reduced-form estimates of pass-through in Sect. 2.Footnote 28 More specifically, we estimate an SVAR with seven variables for each country: changes in nominal trade-weighted exchange rates, consumer price inflation, real GDP growth, short-term interest rates, and changes in trade-weighted foreign GDP and consumer prices as well as foreign short-term interest rates. Detailed definitions are available in "Appendix A", and all variables are at a quarterly frequency. We allow for seven shocks that can affect each country’s exchange rate: three domestic shocks (supply, demand, and monetary policy) and three global shocks (global supply, demand, and monetary policy), and we leave one shock unidentified so as to capture any shocks that don’t satisfy the characteristics of the six well-identified shocks.

In order to identify the shocks, we use a set of standard and straightforward long- and short-run zero restrictions and sign restrictions, summarized in Appendix Table 4. We impose this identification using an algorithm based on Rubio-Ramirez et al. (2010) and Binning (2013) and estimate the model using Bayesian methods with Minnesota priors.Footnote 29 The resulting “shock-dependent” estimates of pass-through tend to be very close to the reduced-form estimates of pass-through (from Sect. 2). For a detailed comparison of the estimates obtained using these two different methods, see Fig. 6 in Forbes et al. (2017).

1.2.2 Contributions of Shocks to Exchange Rate Fluctuations for Individual Countries and Over Time