Abstract

Unilateral adoption of transfer pricing regulations (TPRs) may have a negative impact on real investment by multinational corporations (MNCs). This paper uses a quasi-experimental research design, exploiting unique panel data on domestic and multinational companies in 27 countries during 2006–2014, to find that MNC affiliates reduce their investment by over 11% following the introduction of TPRs. There is no significant reduction in total investment by the MNC group, suggesting that these investments are most likely shifted to affiliates in other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Tax-motivated profit shifting within multinational corporations (MNCs) has been on top of the international tax policy agenda since the global financial crisis—most notably due to the G20/OECD initiative on base erosion and profit shifting (OECD 2015). Profit shifting means that MNCs shift income from affiliates in high-tax jurisdictions to those in low-tax jurisdictions to reduce their overall tax liability. There is ample empirical evidence demonstrating that extensive profit shifting is taking place. For example, it is found that German affiliates of MNCs have paid on average 27% less in taxes than comparable domestic German firms (Finke 2013). In the UK, taxable profits as a share of total assets reported by subsidiaries of foreign MNCs are on average 12.8 percentage points lower than those of comparable domestic standalone companies (Bilicka 2019).Footnote 1 Regarding the scale of revenue loss from international tax avoidance, recent estimates suggest an annual loss in government revenue by between $100 and 650 billion globally, with disproportionately larger losses found for developing countries (UNCTAD 2015; OECD 2015; Crivelli et al. 2016; Trøsløv et al. 2018).

A common way for MNCs to shift profits is through the manipulation of transfer prices, that is, the prices charged for transactions between related parties. These transfer prices are necessary to determine the allocation of profits between affiliates of a MNC group. Tax laws generally prescribe that these prices should be arm’s-length, reflecting market prices that unrelated parties would have used for similar transactions. However, due to information asymmetries vis-à-vis the tax administration, MNCs can often charge artificially low or high prices for sales between related parties in high-tax and low-tax jurisdictions, thereby shifting profits and reducing their overall tax liabilities.

Many governments limit the extent of transfer mispricing by implementing transfer pricing regulations (TPRs) to enforce the arm’s-length principle. These generally describe the methods allowed to determine arm’s-length prices, prescribe documentation requirements, set penalties in case of non-compliance, and determine the probability of a transfer price adjustment. TPRs can raise the effective tax burden on MNCs, thus protecting domestic revenue and leveling the playing field vis-à-vis domestic companies (OECD 2013; Fuest et al. 2013).Footnote 2

TPR may have unintended consequences on MNC investment. If MNC investment would decline in response to the introduction or strengthening of TPR, this could offset its benefits, especially if multinational investments yield positive productivity spillovers to local firms (Andrews et al. 2015). The exact relationship between TPR and investment, however, has received little attention in the literature, in both theoretical research and empirical research.Footnote 3 Indeed, there is currently limited empirical evidence on the causal effect of TPR on MNC investment, with the exception of Buettner et al. (2018) that examines the effect of TPRs on investment by German MNCs between 1996 and 2007.Footnote 4

To fill this gap in the literature, this paper explores the effect of TPR on multinational investment. First, we develop a simple model to infer the likely impact of TPR on the scale of multinational investment. The key channel in the model is that TPR makes it costlier for the MNC to manipulate transfer prices and, thereby, to shift profits into the low-tax country (or alternatively, shift profits out of the high-tax country). This reduces the optimal supply of intermediate inputs and thereby also reduces the return on its investment in the foreign affiliate.TPR thus increases the cost of capital so that fewer investments in the foreign affiliate are undertaken.

Guided by this theory, the paper empirically explores the impact of TPR on MNC investment. We employ a microlevel dataset containing rich information on both MNC and purely domestic affiliates. The main dataset comprises 27 countries during 2006–2014. This is combined with information on the introduction date of TPRs and an indicator of their strictness. Our analysis starts with a standard difference-in-difference (DD) approach, where the identifying variation comes from the differential change in investment by a MNC affiliate relative to investment by a purely domestic affiliate in response to the introduction of TPR in the local economy. The results from the DD regressions point to a strong negative impact of TPR on MNC investment: investment in foreign affiliates is, on average, around 11% lower following the introduction of TPR, compared to investment in similar firms that are wholly domestic. We also run panel regressions, similar to the estimation approach used in Overesch (2009), Riedel et al. (2015) and Buettner and Wamser (2013), to estimate changes in the tax sensitivity of multinational investment due to TPRs. The latter follows a more structural approach and results are reported in “Appendix 2” section. Consistent with the evidence from the DD analysis, results from the panel regressions show that MNC investment responses to tax rates are almost one quarter larger if TPRs are in place. The overall estimated elasticity of investment with respect to the cost of capital is around − 0.69, of which 15% is due to increased sensitivity following the introduction of TPRs.

Deeper analysis suggests that the investment response to TPR varies in several dimensions. For instance, the effect size rises in the strictness of the TPR but decreases in the share of intangible assets of firms; and the effect is more robust at the intensive than at the extensive margin of investment. Effects are also found to be larger if the tax differential grows, but this relationship is not monotonous and responses actually become smaller at very large tax differences. We also uncover asymmetric effects of the TPR that vary across key characteristics of the larger tax system in a country. The investment effect of TPR is larger and more robust in countries that also employ thin-capitalization rules (TCRs). Moreover, while the TPR unambiguously reduces investment and reported profits in low-tax countries, its effect on reported profits is smaller in high-tax countries. Using a different dataset of consolidated accounts, we find further that lower investment in MNC affiliates does not lead to a similar reduction in total investment by the MNC group. We interpret this as evidence of relocation: the multinationals divert their investment away from countries that introduce TPR toward other countries with no TPRs.

This paper contributes to a growing literature that exploits cross-sectional variation to study the effects of anti-avoidance legislations on key aspects of firm behavior, including reported profits (Saunders-Scott 2013, 2015; Beer and Loeprick 2015; Riedel et al. 2015; Marques and Pinho 2016; Nicolay et al. 2016), transfer prices (Clausing 2003; Bernard et al. 2006; Davies et al. 2018; Vicard 2015; Cristea and Nguyen 2016; Flaaen 2016; Liu et al. 2020), and capital structure (Buettner et al. 2012; Buettner and Wamser 2013; Blouin et al. 2014; Merlo and Wamser 2015; de Mooij and Shafik 2018). Our analysis complements these studies by looking at the impact of anti-avoidance legislation on MNC investment. Our paper also directly relates to studies of profit-shifting opportunities on MNC investment (Hines and Rice 1994; Grubert and Slemrod 1998; Desai et al. 2006; Overesch 2009), and the larger literature on taxation and business investment (Cummins et al. 1994; Caballero et al. 1995; House and Shapiro 2008; Cooper and Haltiwanger 2006; Yagan 2015; Zwick and Mahon 2017), by offering a new perspective on the investment effect of TPRs.

Our paper is most closely related to Buettner et al. (2018). Focusing on German MNCs between 1996 and 2007, they find that regulations of transfer pricing exert no significant effects on their FDI or employment abroad. In contrast, we focus on MNCs that are headquartered in over 60 countries. Our findings suggest that there is a negative and sizable effect of TPRs on MNC investment between 2006 and 2014, a period during which efforts to tackle profit shifting have been elevated across countries. Apart from using a larger sample and a different time period for analysis, we also improve upon the empirical strategy by using a difference-in-difference approach. With the inclusion of a valid control group, our estimation strategy better controls for unobserved time-varying macroeconomic shocks that may differentially affect investment in each host country to identify the causal effect of the TPR on MNC investment.

The results in the paper are important for the current policy debate on international taxation. For instance, the negative investment effects from TPRs can make governments reluctant to introduce them unilaterally or encourage them to adopt more lenient regulations in order to mitigate adverse effects on investment. Binding global coordination can prevent this. Restricting the opportunities for countries to set their own anti-avoidance regulations can, however, reinforce tax competition among countries in the use of corporate tax rates (Keen 2001; Janeba and Smart 2003; Bucovetsky and Haufler 2007). The results imply further that coordination should also cover other anti-avoidance rules (such as thin-capitalization rules) as otherwise TPRs might cause substitution into other avoidance channels.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of TPR across countries. Section 3 develops a simple model to illustrate how TPR can affect MNC investment into an affiliate. Section 4 describes the data and sample selection used for the empirical analysis. Section 5 explains the research designs and Sect. 6 reports the main results. Section 7 elaborates on the results for total investment by the MNC group, based on consolidated accounts. Finally, Sect. 8 concludes.

2 Transfer Pricing Regulation

The current system of international taxation is largely based on separate accounting. This means that the unconsolidated account of a multinational affiliate terminates at the border. To determine the income in each affiliate, the multinational must use transfer prices for transactions, including both exports and imports, between related parties. In principle, the setting of transfer prices should follow the arm’s-length principle, meaning that prices of goods and services sold between related parties mimic prices that would be used in transactions between unrelated parties.Footnote 5 Given the nature of related party transactions, there can exist a wide range of arm’s-length prices for the same transaction, especially when a comparable transaction does not exist for unrelated parties. Also, it can be costly for tax authorities to verify whether a transfer price used by a MNC is indeed arm’s-length. Consequently, MNCs have some discretion to under-price exports sold from an affiliate in a high-tax country to an affiliate in a low-tax country (or over-price imports), thereby shifting profits and reducing their global tax burden.

There is ample empirical evidence for the presence of tax-motivated transfer mispricing. Most of these studies estimate how the price wedge between the arm’s-length price observed for unrelated transactions and the transfer price used for related party transactions varies with the statutory CIT rates in the destination country relative to the origin country. Studies for the USA, UK, and France find evidence for significant responses of the price wedge to the tax rate differential, as supportive evidence for tax-motivated transfer mispricing by MNCs (Clausing 2003; Bernard et al. 2006; Davies et al. 2018; Vicard 2015; Cristea and Nguyen 2016; Flaaen 2016; Liu et al. 2020).

To limit transfer mispricing, several countries have introduced transfer pricing regulations (TPRs). These offer guidance in the implementation of the arm’s-length principle and often include various specific requirements. For instance, they limit the methods that can be used by a MNC for establishing an arm’s-length price; specify requirements for the documentation needed to support the transfer price used by a MNC; and set transfer-pricing-specific penalties if mispricing is detected or adequate documentation not provided. The scope and design of these regulations vary between countries and across time. Stricter regulations could increase the cost of transfer mispricing and, indeed, are found to be effective in curbing the extent of profit shifting in advanced economies. For example, Riedel et al. (2015) show that the introduction and tightening of TPRs raise (lower) reported operating profits of high-tax (low-tax) affiliates and reduce the sensitivity of affiliates’ pre-tax profits to corporate tax rates.

Our empirical analysis focuses on the impact of TPRs on investment. It uses two policy variables to capture TPRs. First, we use a discrete variable \({{ TPR}}_{kt}\) to reflect the introduction of transfer pricing regulation. This dummy variable takes the value of 1 in the years after country k introduced some TPR in year t to capture the effect of TPR implementation, and is zero otherwise. This information is derived from Deloitte’s annual Transfer Pricing Strategic Matrix and is summarized in Mescall and Klassen (2018). Panel A in Fig. 1 provides an overview of the number of countries with TPR between 1928 and 2015. Sweden was the first country that introduced some form of TPR in 1928. A more modern version of TPR was first implemented in the early 1980s in Australia. Since then, it has been gradually adopted in other countries across the world. Today, almost 70 countries have TPRs in place. Since 1995, many OECD countries base their TPR on the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines. This development is largely attributed to globalization and the increasing awareness of the risks of profit shifting and base erosion, but also to the fact that the introduction of transfer pricing regulations can function as a defense against other countries (Lohse et al. 2012). As taxpayers tend to allocate more taxable income to countries with strong TPRs in order to ensure compliance, the introduction of transfer pricing regulations can be a way to protect tax revenues. Our analysis exploits countries that have introduced TPR between 2006 and 2014 among the 27 countries in our sample. These include Bosnia and Herzegovina (year of TPR introduction: 2008), Finland (2007), Greece (2008), Luxembourg (2011), Norway (2008), and Slovenia (2007). “Appendix 1” section describes each of the TPRs in more details and shows that in our sample, there is little correlation between the introduction of the TPR and a country’s per-capita GDP or its headline CIT rate.

Transfer pricing regulations (TPRs). (Notes: Panel A plots the number of countries with newly introduced TPRs (top green bar) and the number of countries with existing TPRs (bottom red bar) during 1928–2011. Panel B exhibits cross-sectional variation in the overall strictness of the TPRs (tprisk) during 2006–2014, showing the median, the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the minimum and maximum value of tprisk in a box plot. The dots denote the minimum value of tprisk in later years which are outside the inter-quartile range of the tprisk which is bounded by the vertical line). (Color figure online)

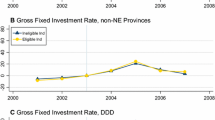

TPRs can vary in several dimensions. This can determine their overall strictness and, therefore, their implications for the behavior of MNCs. To capture the strictness of TPR, we use a second variable, namely an index of TPR strictness developed by Mescall and Klassen (2018). The index is based on 15 detailed features in the regulation and its enforcement [see also Saunders-Scott (2013)].Footnote 6 Mescall and Klassen (2018) use these features to explain the variation in the perception of 76 transfer pricing experts regarding the transfer pricing risk in 33 countries, as revealed in a survey conducted in 2010.Footnote 7 From the regression equation, one can simulate the systematic impact of each TPR feature on the perceived transfer pricing risk, including for countries not captured in the Mescall and Klassen study and for years before and after 2010. Thus, a panel has been constructed of a transfer pricing risk variable, labeled tprisk. This variable measures the overall strictness of the transfer pricing rule and ranges between 1.26 and 5.17 in our sample countries, with higher values reflecting more stringent TPR.Footnote 8 Alternatively, the tprisk variable can be interpreted as a measure of tax uncertainty induced by TPR—an interpretation that more closely resembles that of Mescall and Klassen. Hence, this variable can also shed light on the impact of increased tax uncertainty on MNC investment.Footnote 9 Panel B of Fig. 1 shows the variation in tprisk both across countries and over time in our dataset, reflected by the median, the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the minimum and maximum value. We see that the dispersion across countries has become smaller in recent years, while the median has remained at a similar level.

3 Theory

This section develops a simple model to illustrate the impact of TPR on multinational investment in a foreign subsidiary. Assume that a multinational parent resides in home country h. It decides on how much capital (k) to invest in its foreign subsidiary in country s. For simplicity, it is assumed that the investment is financed by equity at a cost r, which is exogenously determined on the world capital market. Next to capital, the parent also supplies the subsidiary with intermediate inputs (x) used in production—which can also be thought of as firm-specific knowledge. The subsidiary generates output through production technology f(k, x), which features decreasing returns in each of the two inputs, capital and intermediates (i.e., \(f_k,f_x>0,f_{kk},f_{xx}<0\)). Marginal factor productivity of each factor rises in the other input (\(f_{kx}>0\)). Without loss of generality, the price of the final good is normalized to 1.

The parent can buy the intermediate input at the local market at price p (or, alternatively, produce it and then sell at a fixed price p). However, when it supplies x to its subsidiary, the parent can charge a transfer price (\(p^{{\mathrm{T}}}\)) that deviates from the arm’s-length market price. The firm can shift profit between the parent and the subsidiary. Indeed, if the tax rate charged by the country where the subsidiary is located (\(\tau ^{s}\)) is lower than the tax rate charged by the country of the parent (\(\tau ^{h}\)) and the repatriation of income is exempt in the parent country, it will be attractive to shift income from the parent to subsidiary. In deviating the transfer price from the market price, however, the parent faces an expected cost (c), e.g., due to a penalty when caught or because of costs associated with a transfer pricing dispute. The expected cost per unit of intermediate input traded is assumed to rise quadratically in the price deviation, i.e., \(c=\beta (p^{{\mathrm{T}}}-p)^{2}\). The parameter \(\beta\) can be influenced by the government through TPR. For instance, TPR determines the probability of an adjustment in the transfer price or the penalty in case of detected mispricing. Hence, stricter TPR rules are reflected in a higher \(\beta\).

Based on these assumptions, the subsidiary earns the following income:

which is taxed in the host country of the subsidiary. The income is assumed to be exempt in the parent country when distributed. The earnings of the parent company are as follows:

i.e., it earns direct income from the sale of the intermediate input, which is taxable at rate \(\tau ^{h}\), receives the profit from the subsidiary, which is taxable at rate \(\tau ^{s}\), and incurs the cost of financing k and the expected cost of deviating the transfer price from its arm’s-length price.

The parent maximizes its profits with respect to three choice variables: k, x and \(p^{{\mathrm{T}}}\). The first-order conditions of this maximization problem read as follows:

Equation (3) shows the usual optimality condition for investment, indicating that a higher tax rate in the host country of the subsidiary will increase the cost of capital and, therefore, require a higher marginal product for investment to be undertaken. Under decreasing returns, this will reduce investment. Equation (4) shows that the parent will supply intermediate inputs to the subsidiary up to the point where its marginal product equals the marginal cost. If the tax rates in the parent and subsidiary countries are the same, or if the parent charges the arm’s-length market price for the intermediate inputs, then Eq. (4) shows that the marginal cost exactly equals p. Otherwise, the marginal costs of using intermediate inputs in the subsidiary may differ from p, depending on the tax differential and the cost of shifting. Equation (5) determines the optimal transfer price. If the tax rate in the subsidiary country is lower than the tax rate in the parent country, Eq. (5) shows that the optimal transfer price used by the parent will be lower than the arm’s-length price. This is because the lower transfer price will increase the income earned by the subsidiary and decrease direct income earned by the parent. This reduces the overall tax liability of the multinational. The extent to which the transfer price is reduced depends on the parameter \(\beta\), i.e., the cost parameter that can be influenced by TPR.

Combining Eqs. (4) and (5), we obtain an expression of the optimal supply of intermediate inputs:

Hence, Eq. (6) suggests that any tax differential between the parent and subsidiary will lead to a lower required marginal return to x, i.e., \(\partial f_x/\partial (\tau ^{h}-\tau ^{s})|_{\tau ^{s}}<0\). Only if the tax difference is zero will \(f_x\) be independent of tax parameters. Due to decreasing returns, this implies a higher supply of intermediate inputs, i.e., \(\partial x/\partial (\tau ^{h}-\tau ^{s})|_{\tau ^{s}}>0\). Moreover, since \(f_{kx}>0\), it will also imply a lower marginal product of capital and, therefore, an increase in investment (\(\partial k/\partial (\tau ^{h}-\tau ^{s})|_{\tau ^{s}}>0)\).

As long as the tax rates differ (\(\tau ^{h} \ne \tau ^{s}\)), Eq. (6) also shows that TPR will influence the supply of intermediate inputs. This is reflected by the impact of a change in \(\beta\), i.e., \(\partial f_{x}/\partial \beta =-\frac{(\tau ^{h}-\tau ^{s})^{2}}{(1-\tau ^{s})4\beta ^{2}}<0\) so that \(\partial x/\partial \beta >0\), i.e., stricter TPR will reduce the supply of intermediate inputs to the subsidiary. Since \(f_{kx}>0\), this implies that stricter TPR also reduces the marginal product of capital \(f_{k}\) and, therefore, investment \(\partial k/\partial \beta <0\). Intuitively, stricter TPR will require a higher marginal return to capital to break even, and therefore, increases the cost of capital. This effect will only occur if the subsidiary is located in a different country than the parent and the tax rates in these countries differ. Indeed, the size of the effect rises in the tax differential between the two countries. If the parent and the subsidiary reside in the same country (or if tax rates between countries are the same), Eq. (6) shows that an increase in \(\beta\) will have no implications for the optimal supply of x and, therefore, for optimal investment k. We use this difference in our empirical strategy to identify the effect of TPR on multinational investments, using wholly domestic firms as a control group. This constitutes our main hypothesis:

Proposition 1

Stricter TPR will reduce investment by multinational parents in their foreign subsidiaries, but not by purely single-national parents in their domestic subsidiaries.

4 Data

The primary dataset for the empirical analysis is an unbalanced panel of 101,079 unique companies in 27 countries for the years 2006 to 2014. It is constructed using unconsolidated financial statements of affiliates that are part of a multinational or purely national company group in the ORBIS database provided by Bureau van Dijk.Footnote 10 A company is defined as a MNC affiliate if its ultimate parent company is in a different country and owns at least 50% of its shares. A company is defined as a domestic affiliate if (1) its ultimate parent company (owning at least 50% of its shares) is in the same country and (2) all other affiliates of the company group are in the same country of the parent company. The comparison is thus between MNC affiliates and affiliates of purely domestic company groups, excluding all independent, standalone companies that may be less comparable to MNCs. Figure 2 shows the distribution of multinational and domestic affiliates across industry sectors in the main dataset.

The main sample for regression analysis includes all non-financial, non-utility affiliates with non-missing (and nonzero) sales, total assets and fixed asset values. We discard any companies with missing industry information, with less than three consecutive observations, and in countries with less than 1000 observations. We further eliminate MNC affiliates that locate in the same country as their parent company to create a sample of foreign affiliates of MNCs. Table 8 shows the country distribution of affiliates in the main regression sample, distinguished by MNC affiliates and domestic affiliates.

Firm-Level Data The main variables for the analysis are investment in fixed capital assets, sales, cash flow, earnings before interest and tax (EBIT), and earnings before tax (EBT). We compute investment spending (\(I_{t}\)) as the change in fixed tangible assets plus depreciation, i.e., \(I_{t}=K_{t}-K_{t-1}+depreciation\), where capital stock (\(K_{t}\)) is the reported book value of fixed tangible asset in year t. Investment rate (\(I_{t}/K_{t-1}\)), is defined as the ratio between current-year gross investment spending and beginning-of-year capital stock. In some regressions we conduct separate analyses for intensive and extensive margin responses. The intensive margin variable is the logarithm of investment spending. The extensive margin variable is an indicator for positive investment. Sales equal operating revenue. Sales growth rate equals the ratio between current-year and previous-year operating revenue minus 1. Cash flow rate is current-year cash flow divided by lagged capital stock. Profit margin is calculated as EBIT divided by sales. All ratio variables are winsorized at top and bottom 1 percentile to minimize influence of outliers.

Country-Level Variables As discussed in Sect. 2, our main variables of interest are the discrete binary indicator on the existence of some transfer pricing regulation (TPR), and the measure of the overall transfer pricing strictness (tprisk). These two policy variables are constructed based on information provided in Mescall and Klassen (2018), which are available between the years 2006 and 2013. We expand their coverage for one more year to 2014 by using country-specific detailed TPR characteristics in Deloitte’s Transfer Pricing Strategic Matrix, 2014. Data on country-level macroeconomic characteristics, including GDP per capita, the growth rate of GDP per capita, population, and unemployment rate, that capture the aggregate market size and demand characteristics in the host country are from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database. The user cost of capital is computed as \(r_{{\mathrm{real}}}+\frac{1-A}{1-CIT}\), where \(r_{{\mathrm{real}}}\) is the real interest rate and the second term reflects varying tax rules and corporate income tax (CIT) rates in different countries and over time. Data on the statutory CIT rates and the net present value of depreciation allowances (A) are provided by the Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation.Footnote 11 The tax differential, which proxies for the net tax savings from transfer mispricing, is the absolute difference between the host country and parent country statutory CIT rate. Table 1 presents the summary statistics of the key variables that are used in the regression analysis.

Alternative Regression Samples In addition to the main regression sample that includes both multinational and domestic affiliates, we use alternative data in some of the analysis. First, Sect. 6 uses a matched sample of multinational and domestic affiliates based on their average turnover, turnover growth rate, number of workers, and total assets during the sample period. Second, the analysis on the potential spillover effect of TPRs in Sect. 7 uses a sample of consolidated accounts in ORBIS. It includes companies that are parent of multinational or domestic company group to eliminate double counting, as regional headquarters are also required to file consolidated accounts. The sample for this analysis includes 17,638 observations corresponding to about 2024 distinct non-financial, non-utility parent companies (of which 1103 are MNCs) in more than 60 countries in the period from 2006 to 2014. Investment in the consolidated accounts reflects total investment of the company group. Finally, the analysis on the tax sensitivity of FDI in “Appendix 2” section uses a smaller MNC-only dataset that excludes domestic affiliates from the sample to focus on the tax sensitivity of multinational investment.

5 Empirical Specifications

This section describes the main empirical strategy—the standard difference-in-difference (DD) approach—that we use to identify the effect of TPRs on multinational investment. The DD approach estimates the differential changes in investment by MNCs compared to that by domestic affiliates. “Appendix 2” section discusses a more traditional panel regression, which estimates the difference in the tax sensitivity of multinational investment before and after the introduction of TPR.

Our main empirical strategy is the standard DD approach. Intuitively, if the adoption of TPR raises the effective cost of capital only for multinationals, we would expect a subsequent reduction in their investment relative to the investment by otherwise similar affiliates that are part of purely domestic company groups. Formally, we test the investment response using the following specification:

where i indexes firms, k indexes the host country, and t indexes time. We control explicitly in this specification for changes in investment due to other non-tax factors by using a control group of affiliates from purely domestic companies. The latter are exposed to the same aggregate shocks as those experienced by the multinationals. The dependent variable \({ Investment}_{ikt}\) denotes current-year investment spending \(I_{t}\) divided by lagged capital stock \(K_{t-1}\). The key variable of interest is the interaction term between two dummy variables: an indicator that takes the value of 1 if firm i is part of a multinational group and zero otherwise (\(MNC_{i}\)); and an indicator that takes the value of 1 for all the years following the introduction of TPR in country k, and zero otherwise (\({{ TPR}}_{kt}\)).Footnote 12 The coefficient \(\beta _{TPR}\) represents the DD estimate of the effect of TPR on investment by MNC affiliates and is expected to be negative following our theoretical prediction of Sect. 3.Footnote 13

Throughout the various specifications based on Eq. (7), a full set of firm fixed effects (\(a_{i}\)) is always included to control for unobserved heterogeneity in firm-level productivity and parent company characteristics. Firm fixed effects subsume host country fixed effects (given that firms’ ownership information is time-invariant in the sample), controlling for time-invariant differences across host countries that may affect the location choice of multinationals.Footnote 14 These considerations could include, for example, perceived average quality of governance during the sample period, common language and/or former colonial ties with the home country, and geographical distance between the home and host country. We also include a full set of time dummies (\(d_{t}\)) to capture the effect of aggregate macroeconomic shocks, including the effect of the great recession, that are common to both multinational and domestic companies. \(X_{ikt}\) denotes a vector of firm-level non-tax determinants of investment, including proxies for firm size, its growth prospect, the degree of financial constraints and profitability. This is to control for the fact that foreign-owned firms may perform better than private domestic firms, which may imply different investment patterns (Manova et al. 2015). Finally, \(\varepsilon _{ikt}\) is the error term.

We include in most DD specifications the statutory corporate tax rate in the host country (or alternatively, a set of country-year fixed effects), to control for potential confounding effects of concurrent tax reforms on business investment. We also include a set of time-varying country characteristics (\(Z_{kt}\)) in the host countries, including GDP per capita, population, and unemployment rate to capture the effect of time-varying local productivity, market size and demand characteristics on investment. Our preferred specification includes a full set of industry-year fixed effects, country-year fixed effects, and country-industry fixed effects. Taking the full set of fixed effects is crucial to identify the causal effect of TPR on investment. Specifically, the two-way industry-year fixed effects control for the average investment in a given industry-year across all countries, taking out all the industry-specific shocks to business investments in each year. This fixed effect is important to control for any difference in the industry composition of MNCs compared to domestic companies. The second fixed effect, for country-year pairs, controls for macroeconomic shocks to investment that are common to all firms in each country-year pair. Finally, country-industry fixed effects control for all shocks to the supply or demand of fixed capital that are industry and country specific throughout the sample period. The coefficient of interest \(\beta _{TPR}\) hence insulates the effect of TPR on MNC investment from many industry- and country-specific factors that could potentially confound the investment effects of the policy change.

A limitation of the ORBIS data is that information on the ownership structure refers to the latest report year, which is 2014 for most observations in the sample. We assume that the same parent–affiliate ownership structure applies to earlier years. If there are changes in ownership structure over the sample period, there may be potential misclassifications of parent–subsidiary connections, introducing attenuation bias against findings of significant policy effects.Footnote 15

5.1 Identification

Our DD strategy rests critically on the assumption that, prior to the introduction of TPRs, there are no differential changes in investment by MNCs relative to domestic companies, conditional on changes in non-TPR factors that are already empirically controlled for. We perform placebo tests to check the validity of the identification assumption by examining whether there was a differential change in MNC investment in any of the pre-legislation years. Specifically, we estimate the model:

where \(Pre-{{ TPR}}_{l}\) is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 for the lth year before the introduction of the TPR, and zero otherwise, and \(Post-{{ TPR}}_{n}\) is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 for the nth year after the introduction of the TPR, and zero otherwise. Without loss of generality for our test, we normalize \(\beta _{0}=0\). In this specification, the assumption of parallel trends between the treated and control group corresponds to the hypothesis that all pre-TPR \(\beta _{l}\)s are equal to each other, i.e., there is no significant change in the difference between investment by multinational and domestic affiliates in any of the pre-TPR years, even if the investment levels between the two groups could be different. Table 2 presents the full set of regression results.Footnote 16 We test the null hypothesis that there is no difference in the pre-TPR effects, that is, all pre-reform \(\beta _{l}\) coefficients are equal to each other. The p value of 0.23 does not reject the null hypothesis; our parallel trends assumption therefore passes the placebo test.

6 Results

This section first provides direct evidence on the reduction in MNC investment in response to the introduction of TPR, based on the DD regression approach. It then presents robustness checks and discusses heterogeneity in responses. Finally, we estimate the “TPR-adjusted” semi-elasticity of multinational investment, using the structural approach.

6.1 Baseline

Table 3 presents the main DD regression results based on Eq. (7). Each regression in Table 3 includes a full set of firm fixed effects and year fixed effects. We report standard errors clustered at the firm level. Column (1) leaves out any country-level control variables. The DD coefficient is − 0.049 and significant at the 1% level, indicating that, on average, the introduction of TPR dampens MNC investment. The coefficient estimates on firm-level non-tax determinants of investment have the expected signs and are highly significant. For example, the negative coefficients on cash flow and profitability suggest that firms that are less financially constrained invest more in fixed capital assets. The positive coefficient on sales growth implies a positive link between firm-level investment and its growth prospect.

Column (2) of Table 3 checks the robustness of the baseline finding by including the host country-level statutory CIT rate, population, unemployment rate, exchange rate, real GDP per capita, and GDP growth rate. This is to ensure that the DD estimate is not confounded with contemporaneous macroeconomic changes in the host country that may affect MNC investment. Inclusion of these country-level characteristics slightly reduces the magnitude of the DD coefficient from − 0.049 to − 0.041.

The next four columns of Table 3 check the robustness of the baseline finding by subsequently adding two-way country-year fixed effects in Column (3), two-way industry-year fixed effects in Column (4), two-way country-industry fixed effects in Column (5), and two-way home country-industry fixed effects in Column (6). In our preferred specification in Column (6), the DD estimate is − 0.041 and significant at the 1% level. It suggests that, on average, the implementation of TPR reduces the investment rate (i.e., investment as a percentage of the fixed assets) by multinationals by 4.1 percentage point. Given that the average gross investment per dollar of fixed asset is 35.9 cents for multinational affiliates in the sample, this corresponds to 11.4 percent reduction in their investment. Table 11 reports regression results from our preferred specification by industry sector. The DD estimate is negative in all sectors except Agriculture and Forestry and is highly significant in Manufacturing and Whole and Retail Sales. Intuitively, TPRs are more likely to have teeth in Agriculture, as arm’s-length prices are commonly observable for agriculture commodities. The results also show that TPRs matter more for sectors that require more large-scale physical activities in the host countries.

Finally, Column (7) of Table 3 includes an interaction term between \(MNC_{i}\) and the \(tprisk_{kt}\) variable that measures the strictness of TPR. Intuitively, stricter TPR would increase the effective cost of capital faced by multinationals, thereby dampening their investment by more. The negative coefficient estimate on the interaction term suggests that this is indeed the case, with a coefficient of − 0.072 that is significant at the 1 percent level.Footnote 17 For a country with a relatively lenient TPR regime (index of 3.0), the reduction in MNC investment would thus be 0.216 percentage points; for a country with the strictest regime (index of 5.17), this would be a 0.36 percentage points.

Robustness Table 4 presents regressions from alternative specifications and samples to test the robustness of the findings in Table 3. Column (1) excludes profitability and sales growth rate from the firm-level controls to make sure that these variables do not drive the key result. Column (2) excludes affiliates with a parent residing in country that has a worldwide tax system, which could mute the incentive for profit shifting compared to territorial taxation. Column (3) clusters the standard errors at the host country level to address the concern that in tax reform studies, the standard errors can be understated by assuming independence across firms within the same tax jurisdiction (Bertrand et al. 2004). In all three columns, the result on the TPR variable remains unchanged.

Column (4) includes an interaction term between the MNC dummy indicator and a post-crisis indicator that takes the value of one for all years after the Great Recession period. This is to control for potential heterogeneity that multinational and domestic firms have performed differently during the Great Recession (Alviarez et al. 2017). While the coefficient estimate of this interaction term is positive and significant at the 10% level, controlling for the potential differential impact of Great Recession on MNC investment does not substantially change our main coefficient of interest, which is around − 0.037 in this specification.

Column (5) implements a matching DD strategy ( Heckman et al. (1997)) to address the concern that companies in the treated and control groups may not have similar observable characteristics, and that these differences may explain different trends in investment over time. The regression in Column (5) replicates the DD analysis on a subsample of matched firms from a Mahalanobis distance matching procedure based on average firm-level turnover, turnover growth, employment and total assets. The resulting estimate remains positive and significant at the 1% level for the matched sample, and the size of the coefficient remains similar.Footnote 18

In “Appendix 2” section, we use a more structural approach to identify the impact of the introduction of TPR on MNC investment, by estimating the tax sensitivity of MNC investment with and without TPR. The results reported in Table 7 suggest that the estimated semi-elasticity of fixed capital assets is slightly larger than one in the absence of TPR and highly significant. Hence, a 1 percentage-point increase in the CIT rate will reduce MNC investment by approximately 1%. The tax effect increases by 0.24 in the presence of TPR to an overall semi-elasticity of 1.26. Hence, after TPR introduction, corporate tax rates matter about one quarter more for MNC investment than before TPR. The reason is that, as MNCs find it more costly to avoid high tax rates through profit shifting, they become more responsive in their investment to those taxes.

6.2 Heterogeneous Responses

Table 5 explores heterogeneity in investment responses. Columns (1)–(4) focus on heterogeneous investment effects of TPRs across firm characteristics, whereas Columns (5)–(8) present evidence on asymmetric effects of TPRs across countries.

Extensive Versus Intensive Margin The first two columns of Table 5 explore the difference between intensive and extensive margin investment responses. Column (1) uses a discrete dummy indicator for positive investment as the dependent variable. The linear probability regression captures the extensive margin investment responses to TPRs. The coefficient is small and insignificant, suggesting that TPRs have negligible impacts on firm’s likelihood to invest in years after their introduction. Column (2) examines the intensive margin response using the logarithm of investment as the dependent variable, thus excluding observations with negative investment. The DD coefficient is positive and highly significant. Hence, investment reductions due to TPR are most likely due to lower investment by MNCs with positive investment prior to the policy change.

The Size of Tax Differential Equation (6) suggests that the tax differential matters for the impact of TPRs on investment, with the impact becoming larger if the tax differential increases.Footnote 19 To explore this, we divide the sample into quartiles based on the tax differential and then interact the main policy term in Eq. (7) with the quartile indicators:

Column (3) of Table 5 presents the coefficients obtained from this regression. The results suggest that the tax differential indeed matters. At the bottom quartile of tax differential, the response to TPR is negative but insignificant. This may be due to fixed costs associated with changing investment, or because MNCs shift very little profit if tax differentials are small due to the fixed cost of shifting. The investment effect is larger and highly significant in the \(2{\mathrm{nd}}\) quartile of the tax differential, consistent with the theory. However, the impact does not increase monotonically in the tax differential. In fact, the coefficient becomes smaller and less significant in the \(3{\mathrm{rd}}\) and \(4{\mathrm{th}}\) quartile, although it remains negative and significant at 10%. The non-monotonic effect of the tax differential on affiliate investments is also consistent with the explanation that not all tax incentives for profit shifting are captured in the headline CIT rate. For example, loss-making affiliates do not pay any CIT in a host country, so that the tax saving from shifting profits to these affiliates is independent of the host country tax rate. Moreover, there may well exist tax incentives for profit shifting in a host country, including from company-specific advanced pricing agreements and country-specific double tax treaty network, that are not reflected in the statutory tax rate. Differences in TPR enforcement across countries can be another possible reason why the tax differential effect is non-monotonic, thus highlighting the value-added of using the tprisk variable, which does capture the strictness in TPR enforcement across countries in three different dimensions.

The Intensity of Intangible Assets For firms investing heavily in intangible assets, it can be difficult to find comparable prices to comply with the arm’s-length principle. For them, the impact of TPR on investment can be quite different. On the one hand, it might be that TPR offers little guidance as to how transfer prices should be determined. In that case, we might expect that the impact of TPR declines in the share of intangibles. On the other hand, it might also be that TPR is more important for them as it provides tax authorities with greater power to adjust transfer prices. The regression can show which of these is more likely. We test the effect of intangible asset intensity on the relationship between TPR and investment in the following specification:

where \(IntangShare_{i}\) is the average level of intangible fixed assets relative to total assets for firm i during the sample period. In this specification, \(\beta _{TPR}\) captures the impact of transfer pricing regulation on investment for firms with no intangible assets, whereas \(\beta _{Intang}\) captures the changing impact of transfer pricing regulation on investment across firms of different intangible asset intensity.

Table 5 Column (4) reports a negative coefficient estimate on the main interaction term \(MNC_{i}\times {{ TPR}}_{kt}\). The coefficient on the three-way interaction term with the share of intangibles is small but positive and highly significant. Hence, the negative effect of TPR on multinational investment decreases in the firm’s intensity of intangible assets. Note that the size of this effect is small: the difference between a firm with no intangibles (\(IntangShare=0\)) and a firm with only intangibles (\(IntangShare=1\)) is only 0.2 percentage points, i.e., the investment effect drop from − 3.2 percentage points to − 3.0 percentage points.

Interaction Between Transfer Pricing Regulation and Thin-Capitalization Rule MNCs can shift profits through different channels. For instance, apart from the manipulation of transfer prices, they can use intra-company loans to enjoy interest deductions in high-tax affiliates and have the interest taxed in low-tax affiliates.Footnote 20 Hence, it might be that MNCs will respond to the introduction of TPR by substituting away from abusive transfer pricing toward debt shifting through the use of intra-company loans (Saunders-Scott 2015).Footnote 21 Hence, TPRs might be less effective in restricting the overall profit shifting by MNCs if there are no TCRs in place due to unlimited substitution. In that case, the introduction of TPR might have little impact on the effective cost of capital for multinationals and we may expect a smaller effect on investment, relative to the case where a TCR is in place.

To examine the interaction between TPRs and TCRs, we divide the host countries in our sample into one group without any TCR, and a group with some TCR during the sample period.Footnote 22 We then estimate separately the effect of TPR on multinational investment in each country group, using the DD regression based on Eq. 7. Columns (5) and (6) of Table 5 report these results. Interestingly and consistent with our prediction, the DD coefficient for countries without TCR is − 0.013 and insignificant [Column (5)], while the DD coefficient for countries with TCR is almost three times larger and significant at 1% [Column (6)]. Hence, transfer mispricing and debt shifting are likely to be substitutes in MNC profit shifting. The effectiveness of one measure against tax avoidance thus depends critically on other measures. At the same time, the more effective these packages become in limiting profit shifting, the more likely it becomes that they reduce MNC investment.

Low-Versus High-Tax Countries Our main prediction in Sect. 3 suggests that the introduction of TPR should have an unambiguously negative impact on MNC investment in the respective country. On the other hand, the impact of the TPR on reported profits and tax revenues collected from MNCs is likely to differ. For high-tax countries, TPR will likely expand the tax base due to less outward profit shifting; but for low-tax countries, the opposite may occur, i.e., less inbound profit shifting. This suggests that the overall effect of TPR can vary across countries. For host countries with a lower tax rate than the representative country of a parent firm, i.e., beneficiaries from inward profit shifting, TPRs would lower tax revenue as well as investment. For host countries with a higher tax rate, TPR would restrict the extent of outward profit shifting and increase tax revenue, while the investment responses would offset the positive revenue effect.

To test for potential asymmetric effects of TPRs, we include in the regression an interaction term between the main variable of interest (\(MNC_{i}\times {{ TPR}}_{ikt}\)) with a dummy indicator \(Low-Tax_{ikt}\). For each MNC affiliate, the \(Low-Tax_{ikt}\) takes the value of 1 if the host country CIT rate is lower than the average CIT rate of its company group, defined as the unweighted average of the statutory CIT rates of all the countries where its company group operates.Footnote 23 Column (7) of Table 5 reports the results on investment. The coefficient estimate on the new interaction term is negative and insignificant, suggesting similar investment responses in high and low-tax countries. Column (8) of Table 5 reports the results on reported profits, replacing the dependent variable with the log of pre-tax profits defined as earnings net of interest expense but before taxes. Interestingly, introduction of TPR has a negative but insignificant effect on reported profits by MNCs in the high-tax countries, which may reflect the two offsetting effects of TPR on the tax base. However, the effect on reported profits by MNCs in the low-tax countries is also negative, but three times larger and highly significant. The results therefore suggest that the overall effect of TPR on the corporate tax base and total revenue is asymmetric: it is negative for low-tax countries but ambiguous for high-tax countries.

7 Effect on Total MNC Investment

The reduction in fixed capital investment by MNC affiliates identified in Sect. 6 may have two alternative interpretations: it could reflect a reduction in total investment due to a higher cost of capital for the entire MNC company group; or a relocation of investment to other affiliates of the same MNC group. Both investment responses reduce output in the host country in similar ways. However, they have very different economic implications for the rest of the world. Indeed, lower investment by the MNC group would unambiguously reduce global output, while a reallocation of investments across countries would imply a shift of production toward countries that enjoy an inflow of investment. Global output might still decline due to production inefficiency, but is smaller under the second scenario. Of course, cross-country spillovers of this kind can intensify tax competition among national governments and ultimately lead to too lenient TPR in all countries, if there is no international cooperation.Footnote 24

To identify the impact of TPR on total investment of the MNC group, we use a similar DD strategy based on Eq. (7). All the key variables are as previously defined but are now based on consolidated accounts of the parent company. In particular, \({ Investment}_{ikt}\) now reflects the amount of worldwide investment by the MNC group with parent company i in country k. \({{ TPR}}_{kt}\) is a discrete dummy variable that takes the value of one if there is some transfer pricing regulation in the parent country k, and zero otherwise. It is important to note that the \({{ TPR}}_{kt}\) variable defined in this way only captures the effect of TPR in the parent country, ignoring the effect of TPRs in any other countries where affiliates of the same MNC group operate. This implies that there can be measurement error in the \({{ TPR}}_{kt}\) variable to determine the impact of TPRs on the multinational group’s investment, leading to attenuation bias.

Table 6 summarizes the results, where the DD coefficient captures the impact of parent country TPR on total investment by the MNC group. Column (1) reports the baseline regression results based on Eq. (7) with no country-level controls. Contrary to our expectation, the DD coefficient is positive and significant at the 1% level and remains significant with inclusion of country-level characteristics in Column (2). However, the DD coefficient becomes insignificant when including country-year fixed effects in Column (3), suggesting that the significance of the DD coefficient may reflect other country-specific common trends in MNC investment that are unrelated to the introduction of TPR. The DD coefficient remains insignificant when adding industry-year fixed effects and industry-country fixed effects in Column (4). Column (5) interacts the discrete interaction term with the top statutory CIT rate in the parent country, and the basic finding remains unchanged.Footnote 25 Overall, the absence of a clear effect of TPR on MNC consolidated investment suggests that the negative effect of TPRs on investment in foreign affiliates might indeed be due to a relocation effect of investment.

8 Conclusions

Despite increased global interest in transfer pricing regulations to mitigate tax avoidance by multinational companies—most notably due to the G20/OECD project on base erosion and profit shifting—there is no empirical evidence on their implications for investment. This paper fills this gap. It uses a quasi-experimental research design, exploiting a large microdataset of unconsolidated accounts of both multinational affiliates and affiliates of purely national corporations. Guided by a simple theoretical model, it is argued that transfer pricing regulation should only affect the cost of capital of the multinational affiliates. The affiliates of purely national corporations can thus be used as a control group to identify the causal impact on multinational investment. Our data comprise the period between 2006 and 2014, during which seven of the 27 countries in the sample introduced transfer pricing regulations. The estimates suggest that, on average, the introduction of transfer pricing regulations reduced investment in multinational affiliates by more than 11%. The reduction in investment is larger if transfer pricing regulation becomes stricter; and it is also larger for firms that are less intensive in the use of intangible assets. The investment response becomes smaller if the tax differential with other countries becomes very small or in countries that have no thin-capitalization rules in place. Regressions based on consolidated statements indicate that aggregate multinational investment is not affected by transfer pricing regulations, suggesting that multinational firms relocate investment toward affiliates in other countries rather than cut global investment. Thus, transfer pricing regulations induce spillover effects to other countries.

Our results have important policy implications. For example, unilateral introduction of transfer pricing regulation will distort the international allocation of capital; and the negative investment effect can make countries reluctant to adopt them or make them more lenient. Binding international coordination can prevent this, but might not be beneficial for all countries. Also, broad coverage of different anti-avoidance measures is important, as avoidance channels may be substitutes: restricting only one channel will therefore cause a substitution toward other channels of profit shifting.

More research is needed to understand these real effects of other anti-avoidance regulations, including rules that restrict interest deductibility, provisions against treaty abuse, and more general anti-avoidance rules. The interaction between these anti-tax avoidance rules and other tax policy parameters, such as corporate tax rates, is important. These issues are left for further research.

Notes

Dharmapala (2014) and Hines (2014) comprehensively discuss the extent of profit shifting by multinationals. Heckemeyer and Overesch (2013) provide a quantitative review of 25 empirical studies on profit-shifting behavior of multinationals. A more recent survey article by Beer et al. (2018) finds a consensus semi-elasticity of reported profitability by MNCs with respect to the international tax differentials of around − 1.2.

An exception is Peralta et al. (2006), which shows in a fiscal competition model that countries may optimally choose not to control international profit shifting in order to attract more MNC activities. Moreover, the theoretical literature on profit shifting has emphasized that opportunities for profit shifting might help to establish a preferential tax regime that lowers the economic cost of taxation in the context of tax competition (Keen 2001; Janeba and Smart 2003; Becker and Fuest 2012).

Recent studies have assessed the impact of TPR on reported profitability by MNC affiliates and provide mixed evidence: some find that they lead to an increase in the MNCs’ reported operating profits, while others find no significant effect (Riedel et al. 2015; Saunders-Scott 2013). Some studies have also looked at the effect of thin-capitalization rules—another form of anti-avoidance policy—on investment (Buettner and Wamser 2013). To the best of our knowledge, Buettner et al. (2018) is the only other study that examines the impact of anti-avoidance policy, including TPRs and thin-capitalization rules, on investment. We discuss below three key aspects in which this paper differs from Buettner et al. (2018).

The arm’s-length principle is established in Article 9 of the OECD and the UN Model Tax Conventions and is the framework for the extensive network of bilateral income tax treaties between countries. The OECD and UN also have developed Transfer Pricing Guidelines, to support countries’ implementation of the principle.

These detailed TPR features include 12 regulatory variables on whether: (1) the government allows advance pricing agreements, (2) benchmark data are available to taxpayers, (3) the government requires contemporaneous documentation, (4) cost-contribution arrangement is allowed, (5) commissionaire arrangement is allowed, (6) foreign comparables are allowed to estimate transfer prices, (7) related party setoffs (bundling of transactions) are allowed, (8) the taxpayer is required to pay the tax assessment before going to competent authority, (9) the government identifies an order of transfer pricing methods to use, (10) the government requires disclosure on the tax return concerning related party transactions, (11) the government allows a self-initiated adjustment, (12) transfer pricing documentation is required. It also contains 3 enforcement variables on: (13) whether the government has discretion over penalty reduction, (14) whether the government uses proprietary tax data to calculate a “revised” transfer price, and (15) the assessed degree of transfer pricing enforcement as a percentage based on transfer pricing experts’ 1 to 5 assessment of enforcement strictness, where a score of 1.0 (5 out of 5) is most strict and 0.2 (1 out of 5) is least strict.

Specifically, the perceived transfer pricing risk depends on these TPR features in the following way: \(tprisk=1.27^{***}+0.262^{**} SecretComparables-0.437^{***}APA+0.614^{***} NoForeignComps+0.102NoSetoffs+0.319^{**}NoCCA+0.062PayTaxFirst-0.326^{***} BenchmarkData+0.008SelfInitiatedAdj+0.321^{**} NoCommissionaire+0.075RelatedParty+0.39^{***} ContemporaryDoc+0.035TPDoc+0.296Priority+0.533^{***}PenaltyUncertainty+2.46^{***}TPEnforceSvy+0.011^{***}AgeofRules\), where ***, **, and * denote significance level at the 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

The tprisk measure is available for countries whose country-specific detailed TPR characteristics are documented in Deloitte’s Global Transfer Pricing Country Guide. Among the 27 countries in our sample (Table 8), only Bosnia & Herzegovina is not included in the Global Transfer Pricing Country Guide.

For a discussion of the relationship between tax certainty and investment, see IMF and OECD (2017).

ORBIS data are compiled from different sources across countries, such as chambers of commerce, local public authorities, or credit institutions. Accounting standards may also differ across and within countries (for example, small firms may file simplified accounts). For these reasons, the data on financial information are not fully homogeneous. Despite its caveats, ORBIS is the most comprehensive and commercially available database that can be exploited to analyze the spillover effect of tax policy in a cross-country setting. It has been used extensively in both academic and policy research to assess the scale of profit shifting by multinational firms.

The calculation assumes a common real interest rate of 7.5% for all countries throughout the sample period.

This means that \({{ TPR}}_{kt}\) is equal to one in countries that did not introduce TPR during the sample period. Inclusion of observations in these countries increases precision of estimated coefficients of the other covariates and helps controlling for potential life-cycle pattern differences between MNC and domestic affiliates’ investment over time.

Note that this approach assumes away general equilibrium effects, which could affect multinational investment and domestic investment alike through changes in interest rates. Such effects will be captured by time fixed effects. The regression can thus not be interpreted as the total effect of TPR on investment.

In principle, time-varying ownership information is available by linking across different vintages of the ORBIS datasets, or by accessing the ORBIS historical ownership database directly. Unfortunately we do not have such information to construct a time-varying ownership variable, which would have allowed us to include both firm and host country fixed effects.

The coefficients on the \(MNC_{i}\times {{ TPR}}_{kt}\times Post-{{ TPR}}_{n}\) variables also shed light on the dynamics of the investment effect. The results indicate that TPR has a large negative effect on investment in the first year after its adoption. This is consistent with that investment decisions are forward-looking. The size of its effect is smaller but remains significant in later years, indicating that TPRs have lasting permanent effect on MNC investment.

The tprisk measure is not available for countries without TPRs; hence, the regression in Column (7) explores variation in the strictness of TPR for countries with TPRs.

We run additional DD regression using nearest-neighbor matching method, and the results are quite similar to the baseline findings. The full regression results are reported in Table 10.

This tax differential variable thus captures the tax incentive for profit shifting between affiliates and parent companies. Parent companies are typically large relative to the size of the group and have been shown to play a prominent role in the profit-shifting strategies of multinational firms (Riedel et al. 2015).

Beer et al. (2018) reviewed existing empirical evidence on six main channels of international tax avoidance, including transfer mispricing, strategic location of intellectual property (IP), international debt shifting, treaty shopping, corporate inversion/headquarter location, and tax deferral.

Saunders-Scott (2015) examines changes in the reported EBIT following a tightening of thin-capitalization rules for multinational affiliates, using the ORBIS database. The findings suggest that MNCs use transfer mispricing and intra-company debt shifting as substitutes.

Information about the presence of TCRs is obtained from Mooij and Hebous (2018).

This highlights the important consideration that whether a host country is low or high tax is relative and would depend on the group structure of the MNC affiliate.

Peralta et al. (2006) showed in a fiscal competition model that this is indeed the case: a country may optimally decide not to control international profit shifting in order to attract more MNCs.

The basic finding also remains unchanged when interacting the discrete interaction term with the tprisk variable.

These include Cummins, Hassett, and Hubbard (1994, 1996), Desai and Goolsbee (2004), and Edgerton (2010).

It is significantly smaller, however, than the tax term elasticity of − 1.6 in Zwick and Mahon (2017). The latter uses corporate tax records of both MNC and domestic firms to analyze the effect of bonus depreciation on investment by US firms, and find that small domestic firms are more responsive to corporate taxes.

References

Alviarez, Vanessa, Javier Cravino, and Andrei A. Levchenko. 2017. The Growth of Multinational Firms in the Great Recession. Journal of Monetary Economics 85: 50–64.

Andrews, D., C. Criscuolo, and P. Gal. 2015. Frontier Firms, Technology Diffusion and Public Policy. London: OECD Publishing.

Becker, Johannes, and Clemens Fuest. 2012. Transfer Pricing Policy and the Intensity of Tax Rate Competition. Economics Letters 117(1): 146–148.

Beer, Sebastian, and Jan Loeprick. 2015. Profit Shifting: Drivers of Transfer (Mis)pricing and the Potential of Countermeasures. International Tax and Public Finance 22(3): 426–451.

Beer, Sebastian, Ruud A. De Mooij, and Li Liu. 2018. International Corporate Tax Avoidance: A Review of the Channels, Magnitudes and Blindspots. Journal of Economic Surveys. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12305.

Bernard, Andrew B., J. Bradford Jensen, and Peter K. Schott. 2006. Transfer Pricing by US-Based Multinational Firms. Working Paper 12493, National Bureau of Economic Research August.

Bertrand, Marianne, Esther Duflo, and Sendhil Mullainathan. 2004. How Much Should We Trust Differences-in-Differences Estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(1): 249–275.

Bilicka, Katarzyna Anna. 2019. Comparing UK Tax Returns of Foreign Multinationals to Matched Domestic Firms. American Economic Review 109(8): 2921–53.

Blouin, Jennifer, Harry Huizinga, Luc Laeven, and Gaëtan J. A. Nicodème. 2014. Thin Capitalization Rules and Multinational Firm Capital Structure. CESifo Working Paper Series 4695, CESifo Group Munich.

Bucovetsky, Sam, and Andreas Haufler. 2007. Preferential Tax Regimes with Asymmetric Countries. National Tax Journal 60(4): 789–795.

Budd, John W., Jozef Konings, and Matthew J. Slaughter. 2005. Wages and International Rent Sharing in Multinational Firms. The Review of Economics and Statistics 87(1): 73–84.

Buettner, Thiess, and Georg Wamser. 2013. Internal Debt and Multinational Profit Shifting: Empirical Evidence from Firm-Level Panel Data. National Tax Journal 66(1): 63–95.

Buettner, Thiess, Michael Overesch, and Georg Wamser. 2018. Anti Profit-Shifting Rules and Foreign Direct Investment. International Tax and Public Finance 25(3): 553–580.

Buettner, Thiess, Michael Overesch, Ulrich Schreiber, and Georg Wamser. 2012. The Impact of Thin-Capitalization Rules on the Capital Structure of Multinational Firms. Journal of Public Economics 96(11–12): 930–938.

Caballero, Ricardo J, Eduardo M.R .A. Engel, and John C Haltiwanger. 1995. Plant-Level Adjustment and Aggregate Investment Dynamics. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 26: 1–54.

Clausing, Kimberly A. 2003. Tax-Motivated Transfer Pricing and US Intrafirm Trade Prices. Journal of Public Economics 87(9–10): 2207–2223.

Cooper, Russell W., and John C. Haltiwanger. 2006. On the Nature of Capital Adjustment Costs. The Review of Economic Studies 73(3): 611–633.

Cristea, Anca D., and Daniel X. Nguyen. 2016. Transfer Pricing by Multinational Firms: New Evidence from Foreign Firm Ownerships. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 8(3): 170–202.

Crivelli, Ernesto, Ruud de Mooij, and Michael Keen. 2016. Base Erosion, Profit Shifting and Developing Countries. FinanzArchiv: Public Finance Analysis 72(3): 268–301.

Cummins, Jason G, Kevin A Hassett, R Glenn Hubbard, Robert E Hall, and Ricardo J Caballero. 1994. A Reconsideration of Investment Behavior Using Tax Reforms as Natural Experiments. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1994(2): 1–74.

Davies, Ronald B., Julien Martin, Mathieu Parenti, and Farid Toubal. 2018. Knocking on Tax Haven’s Door: Multinational Firms and Transfer Pricing. Review of Economics and Statistics. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00673.

de Mooij, Ruud, and Shafik Hebous. 2018. Curbing Corporate Debt Bias: Do Limitations to Interest Deductibility Work? Journal of Banking & Finance 96: 368–378.

Desai, Mihir A, C Fritz Foley, and James R Hines. 2006. The Demand for Tax Haven Operations. Journal of Public Economics 90: 513–531.

Dharmapala, Dhammika. 2014. What Do We Know About Base Erosion and Profit Shifting? A Review of the Empirical Literature. Fiscal Studies 35(4): 421–48.

Dharmapala, Dhammika, and Nadine Riedel. 2013. Earnings Shocks and Tax-Motivated Income-Shifting: Evidence from European Multinationals. Journal of Public Economics 97: 95–107.

Finke, Katharina. 2013. Tax Avoidance of German Multinationals and Implications for Tax Revenue. Memo, ZEW - Center for European Economic Research.

Flaaen, Aaron. 2016. The Role of Transfer Prices in Prot-Shifting by US Multinational Firms: Evidence from the 2004 Homeland Investment Act. Mimeo, Federal Reserve Board.

Fuest, Clemens, Christoph Spengel, Katharina Finke, Jost Heckemeyer, and Hannah Nusser 2013. Profit Shifting and ‘Aggressive’ Tax Planning by Multinational Firms: Issues and Options for Reform. ZEW discussion papers 13-044, ZEW - Center for European Economic Research.

Grubert, Harry, and Joel Slemrod. 1998. The Effect of Taxes on Investment and Income Shifting to Puerto Rico. The Review of Economics and Statistics 80(3): 365–373.

Hassett, Kevin, and R. Glenn Hubbard. 2002. Tax Policy and Business Investment. In Handbook of Public Economics, vol. 3, 1st ed, ed. A.J. Auerbach, and M. Feldstein, 1293–1343. London: Elsevier.

Heckemeyer, Jost and Michael Overesch. 2013. Multinationals’ Profit Response to Tax Differentials: Effect Size and Shifting Channels. ZEW Discussion Papers 13-045, ZEW - Center for European Economic Research.

Heckman, James J, Hidehiko Ichimura, and Petra E Todd. 1997. Matching as an Econometric Evaluation Estimator: Evidence from Evaluating a Job Training Programme. Review of Economic Studies 64(4): 605–654.

Hines, James, and Eric M. Rice. 1994. Fiscal Paradise: Foreign Tax Havens and American Business. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 109(1): 149–182.

Hines, James R. 2014. How Serious is the Problem of Base Erosion and Profit Shifting? Canadian Tax Journal 62(2): 443–53.

House, Christopher L., and Matthew D. Shapiro. 2008. Temporary Investment Tax Incentives: Theory with Evidence from Bonus Depreciation. American Economic Review 98(3): 737–68.

IMF and OECD. 2017. Tax Certainty—IMF/OECD Report for the G20 Finance Ministers. IMF.

Janeba, Eckhard, and Michael Smart. 2003. Is Targeted Tax Competition Less Harmful than Its Remedies? International Tax and Public Finance 10(3): 259–280.

Keen, Michael. 2001. Preferential Regimes Can Make Tax Competition Less Harmful. National Tax Journal 54(4): 757–762.

Liu, Li. 2020. Where Does Multinational Investment Go with Territorial Taxation? Evidence from the UK. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 148: 1–13.

Li Liu, Tim Schmidt-Eisenlohr, and Dongxian Guo. 2020. Transfer Pricing and Tax Avoidance: Evidence from Linked Tax-Trade Statistics in the UK. Review of Economics and Statistics.

Lohse, Theresa, Nadine Riedel, and Christoph Spengel. 2012. The Increasing Importance of Transfer Pricing Regulations—A Worldwide Overview. Working Papers 1227, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation.

Manova, Kalina, Shang-Jin Wei, and Zhiwei Zhang. 2015. Firm Exports and Multinational Activity Under Credit Constraints. The Review of Economics and Statistics 97(3): 574–588.

Marques, Mario, and Carlos Pinho. 2016. Is Transfer Pricing Strictness Deterring Profit Shifting Within Multinationals? Empirical Evidence from Europe. Accounting and Business Research 46(7): 703–730.

Merlo, Valeria and Georg Wamser. 2015. Debt Shifting and Thin-Capitalization Rules. CESifo DICE Report 01, 12(4): 27–31.

Mescall, Devan, and Kenneth J. Klassen. 2018. How Does Transfer Pricing Risk Affect Premiums in Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions? Contemporary Accounting Research 35(2): 830–865.

Nicolay, Katharina, Hannah Nusser, and Olena Pfeiffer. 2016. On the Interdependency of Profit-Shifting Channels and the Effectiveness of Anti-avoidance Legislation. In Annual Doctoral Conference Paper 2016. Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation.

OECD. 2013. Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting. New York: OECD Publishing.

OECD. 2015. Measuring and Monitoring BEPS, Action 11 - 2015 Final Report. New York: OECD Publishing.

Overesch, Michael. 2009. ‘The Effects of Multinationals’ Profit Shifting Activities on Real Investments. National Tax Journal 62(1): 5–23.

Peralta, Susana, Xavier Wauthy, and Tanguy van Ypersele. 2006. Should Countries Control International Profit Shifting? Journal of International Economics 68(1): 24–37.

Riedel, Nadine, Theresa Zinn, and Patricia Hofmann. 2015. Do Transfer Pricing Laws Limit International Income Shifting? Evidence from Europe. CESifo Working Paper Series 4404, CESifo Group Munich.

Saunders-Scott, Molly J. 2013. How Does Transfer-Pricing Enforcement Affect Reported Profits? Technical Report, University of Michigan.

Saunders-Scott, Molly J. 2015. Substitution Across Methods of Profit Shifting. National Tax Journal 68(4): 1099–1120.

Tørsløv, Thomas R, Ludvig S Wier, and Gabriel Zucman. 2018. The Missing Profits of Nations. Working Paper 24701, National Bureau of Economic Research June.

UNCTAD. 2015. Reforming International Investment Governance, World Investment Report, United Nations Publications.

Vicard, Vincent. 2015. Profit Shifting Through Transfer Pricing: Evidence from French Firm Level Trade Data. Working paper 555, Banque de France.

Yagan, Danny. 2015. Capital Tax Reform and the Real Economy: The Effects of the 2003 Dividend Tax Cut. American Economic Review 105(12): 3531–63.

Zwick, Eric, and James Mahon. 2017. Tax Policy and Heterogeneous Investment Behavior. American Economic Review 107(1): 217–48.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The views expressed are the authors’ and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management. We thank Alan Auerbach, Lily Batchelder, Michael Devereux, Dhammika Dharmapala, Mihir Desai, Vitor Gaspar, Harry Grubert\({^\dagger}\), Jim Hines, Niels Johannesen, Michael Keen, Laura Jaramillo Mayor, Dominika Langenmayr, Julien Martin, Juan Carlos Serrato, Roberto Schatan, Daniel Shaviro, Nicholas Sly, and conference and seminar participants at the IMF, Oxford University, New York University, National Tax Association 2017 Conference, CESifo 2018 Venice Summer Institute, AEA 2018 Annual Meeting, International Tax Policy Forum 2018 Meeting and European Tax Policy Forum 2019 Conference for helpful comments. We are grateful to Devan Mescall for providing the dataset on transfer pricing regulations and to John Russell Damstra and Alice Park for providing excellent research assistance. Any remaining errors are our own.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Institutional Background

This section describes the transfer pricing regulations that were introduced between 2006 and 2014 in our sample countries.

Bosnia and Herzegovina