Abstract

This article examines organizational change in national ministries responsible for higher education in light of public sector reforms. The article suggests an analytical framework based on authority/autonomy and capacity developments, paying special attention to the creation of agencies. Empirically, this is exemplified by two cases: the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Research, and the Ministry of Education and Research in Norway, each in relation to two subordinate agencies. Both ministries initiated structural governance reforms for their national higher education systems in the early 2000s. The results of this study indicate that although similar intentions were driving the reforms in both countries, the way in which the ministries transformed was somewhat different. In Austria, the reduction in ministerial capacity, an absent agency structure, and increased institutional autonomy might have created a potential policy vacuum in system-level governance right after the new higher education law was introduced in 2002. In Norway, ministerial capacity remained stable, while central agencies experienced substantial capacity growth and influence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the early 2000s, a number of Western European countries introduced far-reaching higher education reforms aimed at improving the quality, relevance and productivity of their universities and colleges. The reform agendas included structural adaptations, such as the enhancement of institutional autonomy and the establishment of public agencies especially in the areas of quality assessment and internationalization (Huisman, 2009). The nature of these reforms and their impacts on higher education institutions (HEIs) have received ample scholarly attention (Amaral, 2009; Austin and Jones, 2016; Huisman, 2009; Paradeise et al., 2009). However, the question of how the reforms affected national ministries responsible for higher education (HE) remains an understudied phenomenon. The ‘matrix-structure’ of the public governance of HE in Western Europe implies that the various governance levels, that is, the cabinet, ministry, agency and public organization levels are closely interconnected (Braun, 2008, 232–233). Consequently, it can be assumed that reform of HEIs, in the sense of enhanced autonomy, and the establishment of agencies, in the sense of transferring authority from the ministry to the agency level, will have implications for the ministry level. In addressing this assumption, the aim of this article is to discuss a number of organizational changes that took place in ministries responsible for HE in two countries (Norway and Austria) that initiated a HE reform in the early 2000s.

Drawing on public policy studies that examine the effects of ministerial reorganization and agencification processes (Christensen and Lægreid, 2006; Pollitt, 2005; Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011) issues such as political control, bureaucratic/agency autonomy, and capacity building (see, e.g., Overman and Van Thiel, 2016) will be discussed. These issues have already been studied in various policy areas, such as telecommunication, security, and transportation (as outlined in Maggetti and Verhoest, 2014) but to a lesser extent in HE (Capano et al., 2017; Jungblut and Woelert, 2018). Another blind spot is that even if agencification processes are examined (Beerkens, 2015; Hansen, 2014) empirical evidence about changes in HE ministries is still scarce.

Therefore, addressing the research question how ministries responsible for HE have changed organizationally, the article first introduces a conceptual framework and proposes expectations about the possible effects of public sector reforms on organizational change linked to ministerial authority/agency autonomy and policy capacity. Next, outcomes of a study of ministries responsible for HE in Austria and Norway are presented. The data analyzed in this study are derived from a qualitative document study, with data generated from internal organizational documents, and an examination of national legal frameworks in HE. In addition, descriptive statistics for employee and funding numbers are used. Austria and Norway are considered typical cases (Gerring and Cojocaru, 2016) of an organizational change phenomenon, that is, HE systems in Western Europe undergoing substantial reforms at the turn of the century (in Austria, the University Act 2002 and in Norway, the Quality Reform 2003). Starting with a similar set of underlying motivations for governance reforms (Krüger et al.,2018) the two HE systems are embedded in different institutional frameworks and administrative traditions (Bleiklie and Michelsen, 2013; Painter and Peters, 2010) which makes both systems interesting cases to follow. That being said, the focus is not on the role of the institutional level nor on potential reform effects for institutional autonomy but on ministerial change in light of changed governance constellations. The period from 2000 until 2018 was chosen to cover the situation right before the reforms were manifested in new HE laws up until the most recent available data.

The article starts with an overview of the contextual shifts in public governance structures concerning agencification processes. Then, theoretical and conceptual perspectives are unpacked to examine organizational change in ministries in the context of public administration reforms. These perspectives are substantiated with empirical findings about organizations in the two selected countries: in Austria, the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Research (BMBWF), with the Agency for Quality Assurance and Accreditation Austria (AQ Austria) and the Austrian Agency for International Cooperation in Education and Research (OeAD); in Norway, the Ministry of Education and Research (KD), with the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education (NOKUT) and the Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education (SIU). These agencies were selected because they have a mandate encompassing central policy issues in contemporary HE systems (quality assurance (QA) and internationalization). The article concludes with a brief analysis of the empirical cases and possible future research trajectories.

Changes in Public Sector Governance

Ministries play a central role in the formation and governance of public sectors. As part of public administration, ministries transmit political goals in a rule-bound and bureaucratic way (Christensen et al., 2007; Lodge and Wegrich, 2014). In a sector like HE, this implies the allocation of funds to selected actors, such as universities or agencies. Moreover, the ministries set the policy agenda by, for example, emphasizing student welfare policies or regulating tuition fees. In other words, organizing the distribution of resources and the proliferation of public services is the central task of the ministry responsible for a specific policy sector (Ferlie et al., 2008).

A turning point in Western public administrations in the modern era occurred in the 1970s and 1980s. The recession slowed national economies and presented the (preliminary) end of unprecedented economic growth in Western societies in the postwar era. Rising public expenditure and efficiency problems in the proliferation of state services questioned the traditional governance modes of public administration (Bovens et al., 2001). A solution to these problems was seen in introducing market elements to public administration, such as management concepts and performance measurements. These elements were subsumed under the term New Public Management (NPM) and were assumed to improve the quality and efficiency of state services (Pollitt et al., 2007).

A central aspect in the following NPM reforms was the creation of single-purpose agencies that remained part of the public administration and operate at arm’s length from a ministry (Christensen and Lægreid, 2006). Ministerial responsibilities for a given policy sector, such as HE, were transferred to an agent who then acts on behalf of its principal (the ministry). This middle layer between the state and the policy sector is assumed to solve efficiency problems and improve the quality of state services, as the agent is closer to the day-to-day demands of its target group (Verhoest, 2012). An important agencification process in HE, for instance, took place in the areas of quality assurance (QA) and accreditation (Beerkens, 2015) and internationalization (Altbach et al., 2009), where agencies have become a popular and dominant organizational form in many countries.

However, a persistent challenge with these organizations has been the question of balancing autonomy, control, and accountability. Although this issue has been debated and examined in numerous studies (Christensen and Lægreid, 2006; Maggetti and Verhoest, 2014), less has been said about the implications for ministries, especially in HE. An underlying assumption is that one way to observe organizational change in ministries is to use agencification processes as a mirror for change dynamics in the ministry itself (see, e.g., Christensen et al., 2007). For that reason, it is important to focus on indicators related to ministerial authority, such as task delegation, organizational mandate, and capacity issues, to capture these shifts, as they present one of the main functions of public sector organizations in a specific policy area.

Conceptual Foundation and Possible Scenarios for Organizational Change

The conceptual basis for this study is formed by specific organizational theory approaches for studying public sector governance (Christensen et al., 2007). These approaches are chosen because they address the peculiarities of shifting policies with possible implications for organizational change in public sector organizations. HE governance is characterized by a complex ‘matrix’ structure, given the various interconnected governance levels and multiple policy arenas in which HE is debated (see Braun, 2008). This interconnectedness implies effects on various levels and actors if caused, for example, by comprehensive public sector reforms. This applies to ministries, as well, which are responsible for formulating and implementing policies and coordinating the interests of politics, key stakeholders and society at large. Furthermore, ministries allocate resources and play a central role in the design and maintenance of the legal framework.

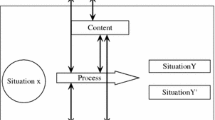

The approach for examining organizational change in ministries discussed in this article proceeds in two dimensions. The first refers to the authority of the ministry, which includes questions about areas of responsibility and task delegation (Christensen and Lægreid, 2006). For example, how is responsibility for QA organized in the public governance matrix of HE? Who is responsible for what kind of aspects of QA? What degrees of authority or autonomy are enjoyed by specific organizations or subunits? Such questions emphasize the importance of the legal framework of the specific sector, as it defines (at least formally) the sphere of influence for any organization involved in public governance. The second dimension refers to the resources that are necessary to carry out public governance tasks, that is, policy capacity (Wu et al., 2018). For example, to make sure that QA regulations are followed, a ministry would have to build a database run by trained IT personnel to collect performance data from HEIs. Or if the ministry outsources that task, the ministry has to equip the responsible agency with sufficient funds. Inconsistencies such as overlapping mandate or “doing the same work twice” can be assumed not to be part of the reform intentions. Authority/autonomy and capacity changes in relation to the agencies thus ideally present zero-sum constellations (e.g., capacity increases at an agency come with capacity reductions in the ministry). However, as it will be seen in the further course, there are instances where a zero-sum approach does not hold.

To start with, ministry and agencies are understood as principal and agent. This differentiation helps to get a better understanding of the structural changes, as ministries have to navigate the task delegation and capacity development in relation to subordinate agencies (e.g., Bach, 2016; Capano et al., 2017). However, the primary focus is not on the interaction between a ministry and an agency per se, but using the agency creation process as a reflection for understanding in which way the ministry is moving. In other words, ministry and agencies are treated as separate organizations that negotiate their influence and area of responsibility, with a clear hierarchy divide in favor of the ministry.

Ministries are usually regarded as being at the intersection of political leadership and apolitical administration. Part of their mandate is to initiate and implement political agendas yet administer them apolitical and impartial way (Egeberg and Trondal, 2009). Over the years, the ministries’ tasks have been increasingly carried out by agencies, which legally present suborganizations. Christensen and Lægreid (2007), for example, defined agencies as “organizations whose status is defined in public law and whose functions are disaggregated from the ministry. Agencies have some autonomy from the ministry but are not fully independent, because the ministry has the power to alter the budgets and main goals of the agency” (503).

Ministries establish agencies because of the assumption that they will lead to a more effective and efficient offer of public services (Christensen and Lægreid, 2007). Task handling and policy-making in a specific policy area have become numerous and complex. Ministries are perceived as being too far from the day-to-day needs and operations of the sector (Verhoest, 2012). To increase quality and efficiency, governing the sector through agencies takes place in a market-like environment, infused by the logics of NPM. As agencies remain part of the public sector and are predominantly funded by public money, they are quasi-businesses that act more professionally and less politically or ideologically oriented than ministries (Verhoest, 2012).

The last point refers to a challenge that continues to dominate the debate on agencification processes, that is, the question of balancing political control and accountability (Christensen and Lægreid, 2007; Egeberg and Trondal, 2009; Verhoest, 2012). This balancing act presents an area of tension because the ministry wants to ensure that the agency fulfills the tasks the public expects from the government. This is important because the ministry is an agent, as well: it is accountable to its political leadership which, in turn, is accountable to the parliament and the electorate (Braun, 2008). Since parliament has to approve the budgets, ministries face certain challenges in times of limited public funds in handling the quality, effectiveness, and efficiency of the sector. These limitations might have an impact on the organizational format of the ministry and its internal organization, for instance, if departments and subunits are merged or rearranged or if responsibilities are transferred to agencies. One option is adjustments in mandate and assigned areas of responsibility, for example, through changes in the legal framework (Bach, 2016). Another option is linked to altering policy capacity, for instance through budgets or personnel (Wu et al., 2018).

Possible Scenarios of Organizational Change in Ministries

The scenarios in Table 1 provide an overview of the different types of organizational change assumed to occur in ministries following public administration reforms. Authority and capacity present the central dimensions that can increase, remain stable, or decrease. Combining these dimensions would lead to nine scenarios. The default position is that neither authority nor capacity changes substantially.1

For instance, a new government emphasizing the importance of HE and science might allocate additional public resources to the respective ministry. The ministry has identified in a policy-making process and hearings the issues that need more attention, such as QA. This area, for example, is defined and outlined in a revised HE law, adding to the existing portfolio of the ministry. Additional funds are used to create capacity in a newly established department or subunit. This example corresponds to the expansion scenario in which authority and capacity grow in a balanced way.

In the opposite scenario, ministerial authority and capacity are constrained. Internationalization, for example (which could have been part of the ministry’s mandate), is now completely left to the institutional sector or transferred to another ministry. Additionally, the ministry would face cuts in its operating budget and a decrease in staff numbers. This example corresponds to the contraction scenario in which authority and capacity are reduced to the same extent.

In another scenario, the ministry mainly faces budget cuts and has to reduce its capacity (e.g., by reducing the number of staff). In organizational terms, that could imply that departments are merged, rearranged, or shut down. If these cuts do not come with a limitation of the mandate as well, the ministry is expected to operate more efficiently (efficiency type 1, efficiency type 2, or hyper-efficiency).2 In a situation in which the ministry is not over-resourced in the first place, this could imply that an agenda, such as the internationalization of HE, is not effectively pursued due to a lack of resources, and thus, is only symbolic.

The opposite effect is achieved if capacity grows by increasing the number of staff and extensions of the operating budget, but not the mandate. This effect can be also achieved by just reducing the mandate but maintaining stable capacity levels (potency type 1, potency type 2, and hyper-potency). QA, for instance, would now be an area that receives more attention because the freed-up resources from other fields are now redirected to QA.

Potential Effects on the Agency Level

The starting assumption is that while not all changes in a ministry have to be linked to agencification, it can be assumed that there is at least some connection between the dynamics of agencification (i.e., the effects for the agents) and corresponding changes in the ministry (the principal).

From an efficiency perspective, authority/autonomy and capacity transfers ideally present zero-sum games between ministry and agencies. Theoretically, however, one can imagine authority/autonomy and capacity increases (or decreases) on both the ministry’s and the agencies’ side. When could that be the case?

If the ministry is expanding (more authority over new policy areas, additional resources) it could be accompanied by strengthened agencies due to sharing its surplus. Those agencies would gain more power because of an extended mandate (ergo more autonomy) and increasing policy capacity (more personnel, expertise, and consequently more influence). The ministry, on the other hand, could still retain its formal responsibility and use the remaining surplus to control and supervise the agencies.

The opposite case would be an implosion of authority/autonomy and capacity issues on both sides. A contracting ministry, for instance, might not be replaced by a strengthened agency structure. In this case, the legal limitations and funding cuts are so comprehensive that bureaucratic responsibility for the whole sector is constrained substantially.

Further, one might also imagine constellations, where only one dimension is expansive or contractive but the other one a zero-sum game between ministry and agencies. For instance, capacity expands on both sides, but authority/autonomy is demarcated evenly. In this case, a ministry transfers responsibility to an agency (and draws back) but maintains its capacity levels while resources for the agencies increase. In other words, there might be non-zero-sum constellations between ministry and agencies, which apply to only one dimension.

In order to examine these assumptions empirically, ministerial authority and policy capacity are further developed as central concepts and translated into suitable indicators that help to study organizational change at the ministry and its potential implications for the agency structure.

Indicators of Ministerial Authority and Policy Capacity

Ministerial authority

Ministerial authority is conceptualized as formal autonomy of the ministry, that is, the ability to define the area of responsibility for the ministry and its subordinate agencies. This conception is in line with Maggetti and Verhoest’s (2014) definition of (bureaucratic) autonomy: “[being] able to translate one’s own preferences into authoritative actions, without external constraints” (241). Therefore, an important aspect and starting point for studying ministerial authority are examining the legal framework, as it provides (relatively) stable parameters for identifying areas of responsibility (Bach, 2016). Further, it helps to understand how tasks and responsibilities have changed in formal terms. The key aim is to examine how areas of responsibility for the ministry have evolved from the time before to the time after the introduction of substantive HE reforms. The following indicators are considered as relevant:

-

Tasks under the ministry’s direct authority:

-

Regulation of national HE law

-

Internal organization regarding HE

-

-

Establishment and/or rearrangement of agencies:

-

Legal status and tasks delegated

-

For the first part of these indicators, it is important to distinguish roughly between different organizational levels of the ministry. In this case, the upper-level refers to the overall format of the ministry. A ministry related to educational and research matters can, for example, be organized as the “Ministry for Education and Research,” “Ministry for Research and Innovation,” or “Ministry for Science and Higher Education,” depending on the overall political agenda and the way in which policy areas are assigned to the organization. The intermediate level can consist of various overarching sections in which the ministry decides to organize itself internally (e.g., secondary education sections, higher education sections, or research sections). The lower-level here refers to all the subsections and subunits (i.e., not the individual level) of which a particular section consists.

Policy Capacity

Policy capacity presents an important variable in the proliferation of the ministry’s services, and questions of authority and organizational change are inextricably linked with it. The effectiveness of public administration can be understood as the proliferation of public services and the capability to solve societal challenges (Fukuyama, 2013; Lodge and Wegrich, 2014) consisting of a “set of skills and resources or competences and capabilities necessary to perform policy functions” (Wu et al., 2018, 3). Wu et al. (2018) propose a framework, which analyzes policy capacity at three different levels (individual, organizational, systemic) based on three different types of competence/skills (analytical, operational, and political). This creates nine different analytical constellations (such as political skills at the individual level or analytical competence on system level). The framework allows for an effective yet nuanced analysis of change along capacity indicators. For this study, the organizational level is of interest (i.e., ministry and agencies as organizational units within the broader sector) and the operational competencies at disposal to permeate the sector.

In this analytical scenario, this typically involves among others public funds to ensure that the system functions as necessary to deliver public goods in the specific policy area (i.e., the funds for the whole HE system) but more so, a budget to cover the operational costs (see Wu et al., 2018, 9–10). A basic assumption is that the higher the operational budget, the more tasks can be addressed. Moreover, the personnel situation plays a crucial role in this, as more personnel in the ministry equal more tasks that can be handled (e.g., Overman and Van Thiel, 2016). Therefore, the following capacity indicators have been used:

-

The ministry’s operating budget (i.e., personnel and material costs)

-

Number of ministerial staff (specifically of the HE section/department)

These indicators link to what to expect from ministerial change in HE: in a reformed environment, the affected organizations and actors have to calibrate their position in the governance matrix which would imply structural modifications in the particular organization (Ferlie, 2006). If a ministry expects to acquire more tasks in the future, it might create new subunits (e.g., a unit responsible for performance agreements or student housing) leading to the recruitment of new staff. Another example is that QA is going to be emphasized but through an agency. Thus, additional resources are needed in order to equip that agency.

These are some considerations of possible change scenarios that require empirical substantiation. The indicators presented above were used to study the Austrian and Norwegian HE ministries focusing on two subordinate agencies, in the period between 2000 and 2018.3

The Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Research

The HE reform initiatives in Austria in the early 2000s have to be seen in context of the general development within Europe (e.g., the Bologna Process) without underestimating the national impetus to reform and transform the Austrian HE system (Winckler, 2012). The preceding university law of the Universities Act 2002 (UG 2002) — the University Organization Act 1993 (UOG 1993) — had aimed at modernizing the tertiary sector by increasing institutional autonomy. Yet, the new law was still embedded in an environment interested in upholding the status quo, that is, low autonomy for the institutional level and a strong academic oligarchy (Winckler, 2003).

It took time until the end of the 1990s, when general European initiatives as well as forces within Austrian HE increasingly pushed for comprehensive university reforms, that institutional autonomy received more acceptance. These efforts culminated in the UG 2002, which, in essence, focused on granting universities more institutional autonomy and shifting more decision-making power from the ministry to the institutions. The relationship between universities and ministry was rearranged through performance-based agreements and global budgets, which were supposed to provide the universities with more strategic room to maneuver (Gornitzka and Maassen, 2017).

From the years 2000 to 2018, the ministry responsible for HE (and science) faced several organizational changes at the upper-level due to the changing governments and political leadership, for example, by being merged with or being separated from ministries responsible for other policy domains. With the implementation of the UG 2002, major changes occurred at the intermediate level; that is, various sections, including the section for HE (in 2018, Section IV: Universities and Universities of Applied Sciences), were rearranged. Generally, a section is responsible for a particular policy area (e.g., teacher education, scientific research and internationalization, universities/universities of applied sciences, etc.). Due to the changes at the upper-level, there has been some variety in the number and order of sections. As an organizational framework, the HE section has been quite persistent with changes merely in the official numbering due to upper-level rearrangements (e.g., from Section VII in the early 2000s to Section IV in 2018) which are cosmetic rather than having hierarchical consequences. The lower-level, however, changed more frequently implying the creation, merging, or closure of subunits.

Annual documents about the internal distribution of functions (Geschäftseinteilungen) reveal that QA as an organizational unit in the ministry played a supervisory role. In 2000, for example, QA was part of the international law division before it became a division of its own. Around the time of the implementation of the UG 2002, however, QA primarily targeted the accreditation of private universities and universities of applied sciences (UAS). A reason might be that formal accreditation of universities was not intended, not even by the Austrian Agency for Quality Assurance (AQA) which began operating in 2004 (Fiorioli, 2014). Furthermore, although the AQA was called an agency, it was registered as an association, with the branch office as a unit of the QA division in the ministry.

This changed in 2012, when the Act on Quality Assurance in Higher Education became active. The act regulated external QA and led to the establishment of AQ Austria which is a merger of formerly three separate QA agencies: FHR (responsible for universities of applied sciences), the ÖAR (private universities), and AQA (tertiary sector). The new agency is a legal entity governed by public law. AQ Austria’s main tasks are, in essence, performing external QA, accrediting HEIs and degree programs, supervising and monitoring HEIs, and providing information concerning QA. Audits at Austrian HEIs can also be performed by other European agencies that are registered in the European Quality Assurance Register for Higher Education (EQAR) or are internationally recognized.4 Formally, this implies the creation of a QA market in Austria, yet with open questions about accountability issues, because foreign agencies — unlike Austrian agencies — are not under the ministry’s control.

Internationalization matters at the HE section were, in essence, divided into two policy areas: international HE law and international/European cooperation and mobility. In the transition period around 2002, these policy areas were part of another section. Further, foreign accreditation and mobility issues were traditionally placed at the Austrian Agency for International Cooperation in Education and Research (OeAD).5 Founded in 1961 as a registered association, the then Austrian Foreign Student Service was responsible for international mobility and cooperation in education, science, and research. The association was founded as a reaction to the growing number of international students and the lack of regulation concerning admission. It was established in a joint effort between the Austrian National Union of Students and the universities, with the main goal to reduce the universities’ administrative burden in foreign student admissions. Further, the OeAD became responsible for distributing government grants to foreign students and was a point of contact for legal advice on scholarships or residence rights. In the following period, OeAD offices were established at all Austrian HEIs (Dippelreiter, 2011).

More recently, the tasks of the OeAD have grown substantially, not least because of European mobility programs for which the OeAD became responsible nationally. Additionally, the OeAD portfolio also covers lower educational levels (which is also the case with the Norwegian agency SIU). The association’s complexity and size led to considerations about a new organizational format. Its legal status as a registered association was no longer seen as appropriate due to an increased complexity of tasks, and more organizational autonomy, such as in personnel policies, was seen as necessary. Therefore, an important milestone was the transformation of the OeAD into a GmbH in 2009 (which is similar to a limited liability company), and was from then on 100% owned by the ministry. This new ownership meant a clear dissociation from the universities and more organizational autonomy in formulating strategy and policy (Dippelreiter, 2011).

AQ Austria and the OeAD, which cover important areas in HE, received strengthened organizational autonomy with some delay. Also, based on the ministry’s internal documents, it seems that ministerial capacity regarding internationalization issues has been increased slowly. In addition, there is a difference in QA before and after 2012. In the beginning, the AQA functioned as a consultative rather than a regulatory agency, and QA was more relevant for tertiary institutions excluding public universities. This changed with the establishment of AQ Austria. Figures 1 and 2 show staff and budget developments for the Austrian ministry, and how the OeAD and AQ Austria (excluding its predecessors) developed in the same period:

Staff numbers of Austrian ministry (HE section), OeAD and AQ Austria (without predecessors). Based on annual reports and internal statistics provided by the organizations. No data available in 2005 for the HE section. OeAD numbers also include staff responsible for lower educational levels.

Operating budget of the BMBWF and preceding ministries (BMBWK 2000–2006, BMBWF 2007–2013, 2014–2017 BMWFW) without funds distributed to the sector, such as program funding or university budgets, as well as OeAD and AQ Austria (without predecessors). Numbers are collected from annual reports and from federal audit reports. The numbers for 2002–2006 for the BMBWF budget are an estimation based on federal audit reports.

The operating budget of the BMBWF in Figure. 2 refers to the overall ministry and thus, includes sections other than HE. Due to the different scenarios, that is, mergers with other ministries (culture, education, economy, etc.), extracting reliable and comparable data over time was nearly impossible. Variations also occur due to different accounting procedures in Austrian public administration from 2013 on. Last, the sole operating budget of the science ministry has been declared “non-public figures” upon request. Thus, the budget numbers must be interpreted cautiously. However, some observations are possible. First, the HE section faced a substantial reduction in staff numbers during the implementation of the UG 2002 (see Figure. 1). As personnel costs present a large line in the ministry’s operating budget, one can also assume that substantial budget cuts occurred in the HE section. Second, there is a steady increase in operational funds from 2007 on, which is not necessarily linked to the personnel costs of the HE section (as they were stable over previous years) but possibly to other sections in the ministry and/or material costs.

In this respect, the Austrian ministry would fall under the efficiency (type 2) category because of the capacity reduction and unchanged responsibilities, at least de facto. Agencies were not strengthened substantially, and HEIs received more institutional autonomy. One could even claim that the ministry is contracting, as the former ministerial mandate was not effectively covered by a subordinate agency structure, which changed only after the agencies became more influential organizations in 2009 (OeAD) and 2012 (AQ Austria).

The Norwegian Ministry for Education and Research

The continuing massification in Norwegian HE at the turn of the century led to challenges concerning funding and quality issues (Kwiek and Maassen, 2012). The first important national attempt to look into these issues was the Mjøs Committee. Committees such as this one (consisting of experts from a particular sector) present an important feature in Norwegian policy-making. The committee’s recommendations led to the 2003 Quality Reform, upon which a revised HE law in 2005 was implemented. The recommendations (of which many were in line with the propositions of the Bologna Process) included, among others, increased university autonomy, performance-based funding, voluntary mergers between HEIs, stronger emphasis on learning, and internal QA mechanisms (Bleiklie, 2009).

In the Norwegian case, the analytical unit of interest at the ministry is defined as “department” (and not “section” as in the Austrian case), that is, the Department of Higher Education. From 2006 until 2018, it was divided into four subsections which — compared to Austria — present an additional layer between the intermediate- and lower level.6 Until 2006, the department had three sections. The section added in 2006 was the Section for Education and Quality Assurance. Its establishment can be interpreted as a stronger organizational focus on QA, which corresponds in general to an increased focus on QA not least because of the establishment of a new agency (NOKUT).

NOKUT started operating in 2003 and was the successor to the Norway Network Council. Similar to the Austrian case, the Norway Network Council used soft regulations (guidelines, suggestions, etc.) for quality assurance at HEIs. NOKUT, however, obtained legal and over time, substantial financial power (for the operating budget and resource distribution to the sector) to apply a stricter regulatory approach (Hansen, 2014). Backed by the 2005 law, NOKUT enjoys considerable autonomy due to its legal status as an autonomous agency. Formally, NOKUT’s decisions cannot be overruled by the ministry as long they are within the scope of the legal framework, which applies, for example, to decisions about accreditation. Over time, NOKUT’s mandate and its portfolio became broader, and the agency was given tasks that went beyond the classical domain of QA (e.g., funding responsibility for centers of excellence).

A similar expansion of mandate and resources was experienced by SIU. This administrative agency subordinate to the ministry is responsible for developing cooperation and international mobility at all educational levels. The agency is mainly responsible for managing programs over a broad geographic range. Further, the agency functions as an expert organization by providing analysis and services for international collaboration. Although these services cover the complete educational spectrum, HE collaborations present the largest part of the agency’s portfolio. SIU’s history goes back to 1991 when it was established as the Centre for International University Cooperation, linked to the University of Bergen. A major turning point in SIU’s organizational format and function came in 2004 when SIU became a governmental agency, an administrative body responsible to the Ministry of Education and Research. As SIU is a central actor in Norway’s internationalization strategy in education and research, more and more tasks have been transferred to the agency over the years leading to a broad program portfolio and an increasing number of international cooperation programs. At the end of 2018, SIU is about to complete a new major reorganization process through mergers, becoming the Norwegian Agency for International Cooperation and Quality Enhancement in Higher Education (Diku).

NOKUT and SIU have experienced substantial growth in capacity since their formal establishment (around a four- to five-times increase in staff numbers and a five- to six-times increase in operating budgets as shown in Figures. 3 and 4). As the legal framework provides both agencies substantial organizational autonomy, one might argue that administrative power in Norwegian HE has, to a large extent, been transferred to the agencies. However, ministerial capacity regarding staff numbers remained stable and even increased in terms of the operating budget. Thus, one might place the ministry within the hyper-potency category, as the capacity has increased slightly while the ministerial mandate has been transferred partly to the agencies.

Staff numbers of Norwegian HE organizations. Based on figures from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), annual reports, and internal statistics provided by the organizations. The decrease in staff numbers in the ministry preceding KD (2000–2001) is due to the separation of church affairs; similarly, the slight increase from 2006 on is due to the inclusion of kindergarten affairs in the newly organized KD. SIU numbers also include staff responsible for lower educational levels.

Closing Reflections

The aim of this article was to present ministerial authority and policy capacity as core dimensions in assessing organizational change of HE ministries in combination with empirical evidence about changes in two HE systems. Since case study research is about analytical not statistical generalization (Eisenhardt, 1989), the contribution of this study is the development of an analytical framework for assessing ministerial change in public administration reforms based on two crucial dimensions, in combination with the first empirical application. The main propositions by the conceptual framework are that HE ministries can go in different directions to tackle changes in the overall system, which presents an important aspect of understanding the dynamics of the governance matrix of HE.

In organizational terms, the changes at the Austrian ministry were more substantial due to shifts in the overall format. The Norwegian ministry had a more consistent development: the structure of the whole ministry and the HE department has remained stable since 2006. An important finding is that the Austrian ministry and HE section faced a substantial capacity reduction, in terms of budget and personnel. This loss seems to be even more severe considering that it was not compensated through strengthened agencies immediately after the reform. In combination with HEIs no longer being micro-managed by the ministry, this might have contributed to a potential policy vacuum in Austrian HE. The Austrian HE ministry would thus be within the efficiency (type 2) category, moving toward contraction in the period right after the reforms. In Norway, there has been a substantial capacity increase in agencies over the years, as well as growing responsibilities. At the same time, it seems that the ministry maintained its capacity over the years. It might thus have used this surplus to focus more on control and strategic planning. Consequently, the Norwegian ministry would be located in the hyper-potency category as capacity has been increased in budgetary terms, but also more responsibility been given to agencies. Concerning principal-agent issues, it is notable that all agencies are now tied to and funded directly by the ministries (e.g., OeAD and SIU developing from program associations linked to universities into governmental agencies) with direct ministerial allocation complemented by indirect funding streams (e.g., EU mobility programs or external accreditation orders).

However, there are some important limitations to consider when it comes to theoretical propositions and empirical evidence. One is, for example, that any legal framework only reveals the formal dimension of authority shifts. Because of this, it might have limited validity for explaining de facto autonomy and how daily operations occur (Bach, 2016). Second, the role of the institutions is taken out of the equation. In order to make more qualified statements about reform effects from a systemic perspective, the effects of institutional autonomy on HEIs have to be taken into account. Further, the categorization of ministries in this study is based on the relation to only two agencies, albeit responsible for important policy areas. One could also assume different outcomes with different types of agencies (e.g., research councils). Additionally, one has to take into account the differing layout of the selected agencies, for example, that NOKUT in Norway partly covers what the OeAD is responsible for in Austria (e.g., foreign accreditation). Last but not least, the question of how effectively the agency level replaces ministerial changes requires a closer examination.

An interesting future research avenue would be to go more into the interactions between ministry and its agencies, for instance regarding accountability or coordination issues. Another direction is to define and examine dependent variables in relation to organizational change in ministries, for example, regarding issues of performance and outcome, such as student numbers, costs, or the general quality of the HE system.

Notes

-

1.

Strictly speaking, this does not present a reform mode as such because genuine reforms would imply changes in the legal framework and resource allocation.

-

2.

There might also be the potential scenario of an increased operating budget but with decreasing staff numbers; one could argue that this scenario is, nonetheless, an overall capacity decrease, as tasks are not effectively executed.

-

3.

As the examined organizations had not concluded their fiscal year by the end of this study, data on staff and budget numbers end in 2017. 2018 still presents an adequate year to conclude this study, as the Austrian and Norwegian ministries have implemented substantial organizational changes, which in the Norwegian case also led to fundamental changes for NOKUT and SIU.

-

4.

For more detailed information, consult the Act on Quality Assurance in Higher Education (HS-QSG): https://bmbwf.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/E_HS-QSG.pdf, accessed 11 June 2018.

-

5.

From 1961 until 2009 the official abbreviation was ÖAD.

-

6.

Upon request to the Norwegian ministry, it was not possible to get data on organizational lower-level changes.

References

Altbach, P.G., Reisberg, L. and Rumbley, L.E. (2009) Trends in global higher education: tracking an academic revolution; a report prepared for the UNESCO 2009 World Conference on Higher Education. Paris: UNESCO.

Amaral, A. (2009) European integration and the governance of higher education and research, Dordrecht; New York: Springer.

Austin, I. and Jones, G.A. (2016) Governance of higher education: global perspectives, theories, and practices, New York: Routledge.

Bach, T. (2016) ‘Administrative Autonomy of Public Organizations’ in A. Farazmand (ed.). Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, Cham, Springer.

Beerkens, M. (2015) ‘Agencification Challenges in Higher Education Quality Assurance’, in E. Reale and E. Primeri (eds.). The Transformation of University Institutional and Organizational Boundaries, Rotterdam: SensePublishers, pp. 43–61.

Bleiklie, I. (2009) ‘Norway: From Tortoise to Eager Beaver?’ in C. Paradeise, E. Reale, I. Bleiklie and E. Ferlie (eds.). University Governance: Western European Comparative Perspectives, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 127–152.

Bleiklie, I. and Michelsen, S. (2013) ‘Comparing HE policies in Europe: Structures and reform outputs in eight countries’, Higher Education 65(1): 113–133.

Bovens, M., Hart, P.’t and Peters, B.G. (2001) Success and failure in public governance: a comparative analysis, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Braun, D. (2008) ‘Organising the political coordination of knowledge and innovation policies’, Science and Public Policy 35(4): 227–239.

Capano, G., Regini, M. and Turri, M. (2017) Changing Governance in Universities: Italian Higher Education in Comparative Perspective, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Christensen, T. and Lægreid, P. (2006) Autonomy and regulation: coping with agencies in the modern state, Cheltenham; Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Christensen, T. and Lægreid, P. (2007) ‘Regulatory Agencies? The Challenges of Balancing Agency Autonomy and Political Control’, Governance 20(3): 499–520.

Christensen, T., Lægreid, P. and Roness, P.G. (2007) Organization Theory and the Public Sector: Instrument, culture and myth, Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Dippelreiter, M. (2011) 50 Jahre Bildungsmobilität: Eine kleine Geschichte des OeAD, Innsbruck: Studienverlag.

Egeberg, M. and Trondal, J. (2009) Political Leadership and Bureaucratic Autonomy: Effects of Agencification, Governance 22(4): 673–688.

Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989) ‘Building Theories from Case Study Research’, Academy of Management Review 14(4): 532–550.

Ferlie, E., Musselin, C. and Andresani, G. (2008) ‘The Steering of Higher Education Systems: A Public Management Perspective’, Higher Education 56(3): 325 – 348.

Ferlie, E. (2006) ‘Quasi strategy: strategic management in the contemporary public sector’, in A. Pettigrew, H. Thomas and R. Whittington (eds.). Handbook of Strategy and Management, London, SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 279–298.

Fiorioli, E. (2014) ‘Entwicklungslinien und Strukturentscheidungen der Qualitätssicherung in Österreich’, in M. Fuhrmann, J. Güdler, J. Kohler, P. Pohlenz and U. Schmidt (eds.). Handbuch Qualität in Studium und Lehre, Berlin: DUZ Verlags- und Medienhaus GmbH, pp. 103–120.

Fukuyama, F. (2013) ‘What is governance?’, Governance 26(3): 347–368.

Gerring, J. and Cojocaru, L. (2016) ‘Selecting Cases for Intensive Analysis: A Diversity of Goals and Methods’, Sociological Methods and Research 45(3): 392–423.

Gornitzka, A. and Maassen, P. (2017) ‘European Flagship universities: Autonomy and change’, Higher Education Quarterly 71(3): 231–238.

Hansen, H.F. (2014) ‘The development of regulating and mediating organizations in Scandinavian higher education’, in M.-H. Chou and Å. Gornitzka (eds.). Building the knowledge economy in Europe. New constellations in European research and higher education governance, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 188–218.

Huisman, J. (2009) International perspectives on the governance of higher education: alternative frameworks for coordination, New York: Routledge.

Jungblut, J. and Woelert, P. (2018) ‘The Changing Fortunes of Intermediary Agencies: Reconfiguring Higher Education Policy in Norway and Australia’, in P. Maassen, M. Nerland and L. Yates (eds.). Reconfiguring Knowledge in Higher Education, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 25–48.

Krüger, K., Parellada, M., Samoilovich, D. and Sursock, A. (eds.) (2018) Governance reforms in European university systems: the case of Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands and Portugal, Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Kwiek, M. and Maassen, P. (eds.) (2012) National Higher Education Reforms in a European Context: Comparative Reflections on Poland and Norway, Frankfurt: Peter Lang GmbH Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften.

Lodge, M. and Wegrich, K. (2014) ‘Introduction: Governance Innovation, Administrative Capacities, and Policy Instruments’, in M. Lodge and K. Wegrich (eds.). The Problem-solving Capacity of the Modern State, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1-22.

Maggetti, M. and Verhoest, K. (2014) ‘Unexplored aspects of bureaucratic autonomy: a state of the field and ways forward’, International Review of Administrative Sciences 80(2): 239–256.

Overman, S. and Van Thiel, S. (2016) ‘Agencification and Public Sector Performance. A Systematic Comparison in 20 Countries’, Public Management Review 18(4): 611–635.

Painter, M. and Peters, B. G. (2010) ‘Administrative Traditions in Comparative Perspective: Families, Groups and Hybrids’, in M. Painter and B. G. Peters (eds.). Tradition and Public Administration, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 19–30.

Paradeise, C., Reale E., Bleiklie, I. and Ferlie, E. (eds.) (2009) University governance: Western European comparative perspectives, Dordrecht; London: Springer.

Pollitt, C. (2005) ‘Ministries and Agencies: Steering, Meddling, Neglect and Dependency’, in M. Painter and J. Pierre (eds.). Challenges to State Policy Capacity: Global Trends and Comparative Perspectives, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 112–136.

Pollitt, C. and Bouckaert, G. (2011) Public management reform: a comparative analysis: new public management, governance, and the neo-Weberian state (3rd ed.), Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Pollitt, C., Thiel, S. van and Homburg, V. (2007) New public management in Europe: adaptation and alternatives, Basingstoke; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Verhoest, K. (2012) Government agencies: practices and lessons from 30 countries, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Winckler, G. (2003) ‘Die Universitätsreform 2002’, in A. Khol, G. Ofner, G. Burkert-Dottolo and S. Karner (eds.). Österreichisches Jahrbuch für Politik 2003, Wien: Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, pp. 127–137.

Winckler, G. (2012) ‘The European Debate on the Modernization Agenda for Universities. What happened since 2000?’, in M. Kwiek and A. Kurkiewicz (eds.). The Modernization of European Universities. Cross-National Academic Perspectives, Frankfurt/Main: Peter Lang, pp. 235–249.

Wu, X., Ramesh, M. and Howlett, M. (2018) Policy Capacity: Conceptual Framework and Essential Components, in X. Wu, M. Howlett, and M. Ramesh (eds.). Policy Capacity and Governance: Assessing Governmental Competences and Capabilities in Theory and Practice, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–25.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Peter Maassen and Jens Jungblut for their continuous support and feedback. Further thanks to my colleagues from the SCANCOR cohort 2018 at Stanford University for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Friedrich, P.E. Organizational Change in Higher Education Ministries in Light of Agencification: Comparing Austria and Norway. High Educ Policy 34, 664–684 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-019-00157-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-019-00157-x