Abstract

Participation in the public debate constitutes one of the most evident avenues for political scientists to demonstrate the social relevance of the discipline. This article focuses on two questions: the types of roles political scientists adopt in their public interventions and the potential tensions between their public engagement and the epistemic norms regulating academic and research activities. We investigate these questions in the context of very salient political debates, involving a high degree of political confrontation, where basic political beliefs, values, identities, and interests are at stake. Focusing on the case of the public debate surrounding the Catalan independence crisis (2010–2018), we demonstrate that in this type of context, (1) political scientists mostly adopt a partisan stance in their public interventions, yet it is also frequent that this is combined with the presence of academic elements in their discourse; (2) demand side factors (media outlets’ editorial lines) reinforce these partisan dynamics. These findings show that opportunities for increasing the social relevance of political scientists in these highly contentious contexts might come at the price of creating tensions that could erode the legitimacy of political science knowledge before the public.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Some recent research has shed light on the attitudes and participation of political scientists in the public debate. The survey to political scientists in Europe carried out in the context of the PROSEPS project (Verzichelli, Real-Dato, and Vicentini, 2019)Footnote 1 has shown that a great majority of political scientists in Europe feel they should become involved in public debates as an inherent part of their role as social scientists. Moreover, many of them tend to do it in a more or less regular fashion. There is also evidence that this involvement is influenced by individual-level factors, such as professional norms, seniority, gender, or the particular country context.

However, there is still a knowledge gap concerning the specifics of the participation of political scientists in the public debate. In the introduction to this special issue, Real-Dato and Verzichelli (2021) connect such participation to the issue of the social relevance of political science, pointing to three main dimensions of interest: the involvement of political scientists in partisan discussions, their visibility in the public sphere, and the actual impact of their interventions on policy making decisions. In this article, we are interested mostly in the first dimension, and, indirectly, in the second one.

On the one hand, we focus on the types of roles political scientists adopt in their public interventions, particularly concerning the display of partisan stances, and the potential tensions between the public engagement of political scientists and the epistemic norms regulating academic and research activities. On the other hand, we examine how partisanship and visibility interact in a context of highly politicised and salient debates where basic political beliefs, values, identities, and interests are at stake—though we do not evaluate the visibility of political scientists per se.Footnote 2 In theory, the high degree of media and public attention on these very salient and divisive issues (particularly where they fit the disciplinary knowledge of political science) may increase the opportunities for public debate-oriented political scientists (Real-Dato and Verzichelli 2021). Our basic argument is that such visibility will come at the price of subordinating the academic to the partisan “hat”.

This article investigates these issues by focusing on Spanish political scientists participating in the media in relation to the internal crisis produced in Spain by the nationalist independence movement in Catalonia between 2012 and 2018. This crisis constituted a fully fledged systemic crisis, as it involved putting into question the existing territorial integrity and constitutional configuration of the Spanish state. Through analysing the content of the interventions of political scientists in major national and Catalan newspapers, we shed light on the different roles adopted by participants and how normative tensions are solved.

The article is structured as follows. The following section presents the theoretical framework that underpins the expectations we test in the article about the roles of political scientists in highly contentious public debates and the influence of the media system. Then, we provide some context, by introducing the basic features of the Catalan independence crisis. The next two sections constitute the core of the article. After describing the process of data collection and coding, we analyse the data to test the expectations developed in the theoretical section. The article finishes with a summary of the findings and a reflection on further avenues of inquiry.

Political scientists’ roles in the public sphere on highly contentious issues

Most academic political scientists generally consider that their role as social scientists implies their engagement into public discussion. This attitude appears more as an internal normative imperative (Verzichelli, Real-Dato, and Vicentini, 2019) than a result of external conditionings, yet the increasing pressure put on academic researchers by the “impact agenda” (Flinders, 2013; Bandola-Gill, Brans, and Flinders, 2021) constitutes an additional incentive.

But the approach to such engagement varies. Schematically, political scientists may wear different “hats” when they get involved in the public debate. First, they may intervene in the public debate wearing the scientist/expert “hat”, applying disciplinary knowledge to illuminate certain aspects of a specific issue for the general public (observer role, see the introductory article to this special issue). They may also point to courses of action (existing or in theory), but avoiding at any time to show any sympathies for any particular positioning or actor (broker role). In this context, interventions prioritise epistemic norms guiding the production of scientific knowledge, such as methodological rigour and value neutrality over political positionings or sympathies.

In contrast to this approach, interventions in the public debate may explicitly advocate specific political positions or interests. In this partisan role, political scientists’ discourse is entirely designed to support a political stance, while norms that regulate the production of scientific knowledge might be entirely neglected.

But, between the ideal type roles of the scientific/expert and the partisan advocate, there are grey zones. Some authors contend that partisanship may slip inadvertently into the discourse even when individuals try to stick to the pure scientist/expert role (Shapiro, 1984). This unintended (and unavoidable) partisanship in public interventions may surface in the selection of issues, the vocabulary in use or if discourses reproduce specific social constructions (Schneider and Ingram, 1997). A person familiar with the issue at hand could identify these situations as hidden partisanship. However, since such identification could raise problems of empirical validity for its extreme dependence on subjective judgement, we focus only on those instances where the authors’ political positioning can be explicitly identified in the text.

Even if explicitly adopting a partisan role, individuals may also appear in their interventions wearing the scientist/expert “hat”. Here, individuals act as politically oriented experts, using scientific arguments or evidence in parallel to arguments supporting a specific political position. These situations put pressure on the norms regulating scientific activities. Publicly stating a political positioning seems to contradict the basic scientific epistemic norm of value neutrality, particularly if it is evident that scientific evidence or theories are instrumental to the political argument. In this context, scientific knowledge used in the public debate risks being deemed tainted, even if such knowledge is based on evidence obtained through rigorous methods and the author clearly differentiates scientific facts or arguments from values.

These tensions and suspicions about the use of scientific knowledge in the public debate should rise when those debates turn around highly contentious issues. The public policy literature has shown that rational learning (using new evidence to change or adjust existing policy beliefs) is less likely when the levels of conflict within policy subsystems are high–that is, when basic policy beliefs are at stake or questioned (Jenkins-Smith, Nohrstedt, Weible, and Ingold, 2017). In these contexts, individuals adopt a defensive stance, where scientific evidence is much likely to be used to support and reinforce existing positions, while new information disputing one’s basic beliefs is rejected [see also Majone (1989)]. In short, in situations of high conflict, partisanship would usually trump science in the policy process.

Similarly, we should expect that the partisan role predominates when political scientists intervene in highly contentious public debates. Though we do not deny that in these contexts political scientists may intervene in a dispassionate fashion—as observers or brokers, just wearing the scientist/expert “hat”—there are several reasons supporting that expectation. First, political scientists, as most members of a political community, also hold basic political beliefs about the nature of that community, how it should be ruled, which political and social values should predominate, etc. These basic beliefs usually convey intense emotional feelings and identifications, which make the distortion of rational arguments more likely, by emphasising affective traits over evidence or through other cognitive biases, such as confirmation or “myside” biases (Kahneman, 2011; Mercier and Sperber, 2017). In addition, many of those beliefs are of a normative nature and, therefore, are immune to scientific empirical evaluation and incommensurable with other normative beliefs, which eventually might reinforce those biases.

Beyond these reasons, factors linked to the structure and dynamics of mass media system explain the expected predominance of political scientists wearing the partisan “hat” in public debates on highly contentious issues. In media systems characterised by “political parallelism” (Hallin and Mancini, 2004), media outlets are prone to hold identifiable political positions, close to those of specific political parties or the government. In those politicised contexts, highly contentious issues are likely to resonate in the outlets’ content in line with their political stance. Therefore, we can expect that politicised media reinforce conflictual dynamics present in the public debate by giving a voice to individuals (in our case, academic political scientists) aligned with their editorial positioning. Indirectly, this might enhance the visibility of these political scientists adopting a partisan “hat”.

From these arguments, we derive the following hypotheses:

-

1.

The participation of political scientists in highly politicised debates will be characterised by a predominance of a partisan stance, both collectively and at the individual level;

-

2.

Such partisan stance will be more evident among those scholars more visible in the public debate;

-

3.

Given the high politicisation of the media system, partisan interventions will be grouped in different media according to their positioning in the debate.

We test these hypotheses using the case of the role of Spanish academic political scientists during the internal crisis produced by the nationalist independence movement in Catalonia between 2012 and 2018 (what we will call the “Catalan independence crisis”). As in other cases analysed in this Special Issue, like those of the Greek bailout referendum (Tsirbas and Zirganou-Kazolea, 2021) or the Italian constitutional referendum (Vicentini and Pritoni, 2021), this crisis has all the characteristics of a highly contentious issue. But while those cases focus, respectively, on major political decisions or institutional reforms, the Catalan independence crisis constitutes a fully fledged systemic crisis involving a questioning of Spain’s territorial integrity, as a significant part of the citizens and political actors in Catalonia demanded (and manoeuvred for) the right to secede this territory from Spain and establish a new independent state. We review this context in the next section. Besides, the high level of politicisation of the Spanish media system (Chaqués-Bonafont, Palau, and Baumgartner, 2015; Büchel et al, 2016), which was manifested in coverage of the Catalan independence crisis, makes the case suitable to test whether media dynamics reinforce partisanship in public debates.Footnote 3

The context: the Catalan independence crisis

In this section, we offer just a brief analytic overview of the main events and political dynamics of the Catalan independence crisis during the analysed period (2010-2018). For a more detailed narrative, sources and chronology focusing on the main events in this crisis, see the online supplementary documentation.

We distinguish three main periods: (1) a preparation period (“pre-procés”), from 2010 to the November 2012 Catalan election; (2) the “procés period”, from late 2012 to the unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) on 27 October 2017; and (3) the post-procés period, from that date onwards.

Most analystsFootnote 4 point to the 2010 Spanish Constitutional Court’s (Tribunal Constitucional, TC) ruling on the 2006 Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia as the event initiating the Catalan independence crisis. The ruling stroke down key sections of the Statute on language, nationality, and judicial powers of the Catalan autonomy, a decision that was interpreted among nationalist Catalan parties and civil society sectors as a demonstration that the Spanish state was not able to satisfy their demands for the national recognition of Catalonia (Requejo and Sanjaume, 2013). This and the claim that Catalonia was treated unfairly by the Spanish state in terms of public funding were the two basic lines of argumentation in the strategy aimed at mobilising support for secession developed by pro-independence parties such as ERC (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya— Catalan Republican Left) or CUP (Candidaturas de Unitat Popular—People’s Unity Candidacies), as well as civil society organisations, such as Òmnium Cultural and ANC (Assemblea Nacional de Catalunya—National Assembly of Catalonia). This strategy proved very successful, as illustrated by the massive 2012 Diada demonstration and the growth, between 2010 and 2012, of support for independence, which experienced a quantum leap from minority status to almost a majority among Catalans. This series of events and the fear to lose its hegemony within the nationalist field led CiU (Convergència i Unió—Convergence and Union), the nationalist coalition governing Catalonia since December 2010, to veer towards secessionist positions. Thus, CiU's manifesto for the November 2012 Catalan election included a defense of Catalonia's right to self-determination (Barrio and Rodríguez-Teruel, 2017; Barrio and Field, 2018).

The second phase of the independence crisis overlaps with what is popularly known as the “procés” (process), which ended on October 2017 with the UDI and the intervention of the Catalan institutions by the Spanish government. Initially, during the campaign of the 2012 Catalan election, pro-independence forces framed the procés as a path towards realising the legitimate democratic right of the citizens in Catalonia to decide about their political future on their own, intendedly through a referendum to be held in November 2014. After the TC stopped the referendum—which was reduced to a symbolic consultation (López and Sanjaume-Calvet, 2020)—the procés was less ambivalently redefined as a process towards the construction of an independent Catalan state. This was considered as the only path to grant Catalonia the recognition of its sovereign political identity, denied by the Spanish state, as well as its economic prosperity. These ideas were central in the campaign for the 2015 Catalan elections, which were presented by secessionist forces as a plebiscite on the independence of Catalonia.Footnote 5

The procés period was characterised by a steadily increasing polarisation of the Catalan political space along the national dimension (Barrio and Rodríguez-Teruel, 2017). After separatist forces failed to win the majority of the popular vote in the 2015 plebiscitary election, during 2016 and 2017 they formed a quite unified front (though internal competition for hegemony between CDC and ERC continued). Together, they pushed for unilateral secession, ignoring the Spanish legal system and the rights of parliamentary minority. Their goal was to force a second referendum of self-determination. The referendum finally took place on 1 October 2017, although it was declared illegal by the TC. In contrast, the forces opposing secession remained much divided. The leftist Podemos (We can) and its regional branch, Catalunya Sí que es Pot (Catalonia, yes we can), granted the right for self-determination. On the opposite side, the Partido Popular (People’s Party, PP) and Ciudadanos (Citizens) rejected any concession to secessionist parties and emphasised the defence of the Spanish constitutional order. In between, the Socialist Party (PSOE) and its regional branch, the PSC (Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya—Socialist Party of Catalonia), though also denied secessionist claims, favoured a better accommodation of the demands of national recognition by the Spanish state (PSOE, 2013). However, when the secessionist procés advanced towards its full realisation during 2017, the PSOE ultimately backed the PP government when it proposed in October 2017 to take back the powers the Spanish Constitution granted to the Catalan region after the UDI by the Catalan parliament.

The third stage of the independence crisis (the post-procés period) is characterised, firstly, by the intervention of the Catalan regional autonomy by the Spanish government in implementation of the 155 article of the Spanish Constitution, which lasted until the formation of the new Catalan government in May 2018. This is also the period of the judicial prosecution of the Catalan government and other leaders of the procés. Some of them (including the former vice-president of the Catalan government) were sentenced on 14 October 2019 for sedition between nine and thirteen years of prison. Other leaders, such as former regional president Carles Puigdemont, avoided prosecution by fleeing to other European countries.

An additional feature of the post-procés period is the stalemate in the correlation of forces after the December 2017 Catalan election, with a secessionist government being supported by a thin parliamentary majority formed by Puigdemont’s JxCat (Junts per Catalunya, Together for Catalonia), ERC and CUP, while parties opposing independence won the popular vote. Finally, since 2018 there has been a relative de-scalation of the conflict, motivated by the arrival of the PSOE to the Spanish government and its parliamentary dependence on an ERC, which showed more open to dialogue.

Data and methods

The empirical case study covers the core events in the Catalan independence crisis, spanning from the January 2010 until the end of 2018. Opinion pieces published by academic political scientists in major commercial national and Catalan conventional generalist newspapers constitute our corpus for qualitative content analysis (Schreier, 2014). Given the difficulties for systematic identification of pertinent instances, we exclude interventions in other media outlets (radio or television broadcasts, as well as online newspapers). We have also excluded to examine books or book chapters on the topic targeted for non-academic audience, since the more limited audience of this kind of publications usually implies a lower impact on the public opinion.Footnote 6

The selection of newspapers aims at reflecting the different angles of the debate and the plurality of positions, as well as their public relevance. We included the three most important (in terms of audienceFootnote 7) generalist newspapers published in Madrid (El País, El Mundo, and ABC). In Catalonia, we included two newspapers with widely read national editions and published both in Castilian and Catalan (La Vanguardia and El Periódico), and the two leading newspapers with an exclusive regional scope, Ara and El Punt Avui, published only in Catalan. This later newspaper is the result of the merge, in August 2011 of two previous outlets, El Punt and Avui, both of which we have also included in our analysis of the period 2010–July 2011.

We identified opinion pieces written by academic political scientists using an electronic database of Spanish newspapers (MyNews, https://hemeroteca.mynews.es/) in a systematic, multi-step process (see the online supplementary documentation). In the end, the corpus contains a total of 371 opinion pieces. We did not include articles which dealt with the procés issue but did not adjust to our selection criteria.

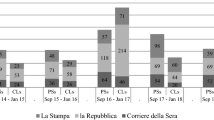

Figure 1 presents the distribution of articles by outlet and year. Most of the texts (67.9%) are concentrated in the procés period. More specifically, about a third of the articles (35.6%) were written between the 2012 Diada and the failed referendum of 2014. The other period where political scientists were more active was between the 2015 election and the unilateral declaration of independence (24.3%). Figure 1 also shows that interventions of academic political scientists on the Catalan secession issue mostly appear in Catalan newspapers until 2015, though in the following years there is a balance between Madrilenian and Catalan outlets. Finally, interventions are mainly concentrated in two newspapers, El País (38.5% of articles) and Ara (26.7%), published, respectively, in Madrid and Barcelona, and the latter only in Catalan language.

Additional descriptive statistics confirm three asymmetries, also revealed by the PROSEPS survey (Verzichelli et al., 2019), about the participation of political scientists in the public debate. One is the presence of a group of highly engaged individuals which account for a great majority of the contributions (we develop this below in the text). A second asymmetry refers to gender. Women authored or co-authored only 8.6% of the articles. In terms of individual authorship, of all 53 participants, seven were women, and just one of them is among the group of highly active authors. Finally, participation of senior scholars is much more frequent (54% of the texts were written by full professors).

The units of analysis in the corpus are each of the articles. We coded their content across several dimensions, indicated in Table 1. In consideration of the sometimes highly interpretative character of the evidence supporting the allocation of some codes and, therefore, aiming at maximising the reliability of the coding process, we opted for the strategy suggested by Guest, MacQueen, and Namey (2012: 89). Consequently, two of the authors coded separately every article in the corpus. Then, we compared results and discussed dissimilarities thoroughly until agreeing one code. In case of no agreement, the default coding option was the absence of the feature in the article (“no” or “not mentioned”). Finally, since the purpose was to judge the interventions of political scientists entirely by their content and avoid any bias from contextual factors, we decided to eliminate dates and authors’ names from the coding template and shuffle the articles for analysis, so they were coded in a random sequence.

Analysis

Mapping partisanship in the public debate

Our first theoretical expectation concerns the predominance of the partisan role among political scientists participating in public debate regarding the Catalan independence crisis. Here, we consider as “partisan” those articles in which the authors clearly exhibit a preference for a political position or interest in the debate. We operationalised this in our coding procedure through the variable “Side” (see Table 1), where partisan categories correspond to those articles clearly aligned (as judged by the coders) with (1) pro-independence/sovereigntist positions favouring the secessionist option; (2) anti-independence/constitutionalist positions supporting the status quo, and (3) “third way” alternatives, contrary to the secession of Catalonia from Spain, but in favour of some kind of agreement leading to institutional reforms (i.e. federal reform) that imply an advancement in self-government and political recognition of Catalonia.

Figure 2 presents evidence of the validity of this measure by means of multiple correspondence analysis (MCA). MCA is a statistical technique used to detect and represent underlying structures in categorical data (Le Roux and Rouanet, 2010). The solution plot presented in Fig. 2 includes variables measuring several of the content-analytic dimensions coded in the texts (criticism, legitimacy, blame, and nature of Catalan society). We identified two meaningful dimensions. A vertical dimension (politicisation) discriminates between non-evaluative categories and political evaluative categories. The horizontal dimension (side), in turn, differentiates between political positions. One side of the plot is populated with categories that imply the legitimacy of pro-independence positions, putting the blame on the Spanish government and parties, and asserting the illegitimacy of constitutional positions and actions or the homogeneous nature of the Catalan society. We divided the positive side of this horizontal dimension into two clear sections: one situated to the extreme, which includes categories affirming the illegitimacy of pro-independence claims, the legitimacy of constitutional stances, or blaming the Catalan government and parties for the situation. Closer to the origin appear those categories asserting the heterogeneity of the Catalan society, criticising pro-independence positions and actions, or dividing up the blame between Spanish and Catalan political actors.

Then, when we project the “Side” variable on the MCA solution, we observe that the variable’s categories nicely fit into the two-dimensional space. So partisan stances are projected on the lower half of the plot coinciding with the distribution of evaluative arguments (pro-independence articles on the negative side of the horizontal dimension, third-way positions to the middle and constitutionalist/anti-independentist articles on the far right). Projections of articles with non-identifiable political positionings appear about the middle of the top half of the plot. Finally, in the case of articles coded as “neutral”, since they usually involve balanced political evaluations, they are projected in the bottom half of the plot, about the middle of the horizontal dimension. In any case, we will not consider these neutral articles as partisan, since, according to our definition, they do not exhibit a clear political preference in the text.

Predominance of the partisan “hat”

Returning to the hypothesis about the predominance of the partisan role in political scientists’ interventions, we confirm across the whole period that articles classified as pro-independence/sovereigntist, constitutionalist/anti-independence, or “third way” amount to 55.5% of the total. Within these articles with a partisan stance, a majority supports a pro-independence stance (30.7%), while texts identified with constitutionalist and third-way options represent 11.9 and 12.9%, respectively. In turn, the proportion of articles adopting a neutral positioning amounts to only 4.1%. Finally, those articles where we cannot identify a political position represent 38.8% of the total.

Figure 3 shows a more fine-grained view. The general pattern (represented by the average lines) is also present across the different stages of the crisis—pre-procés, procés, and post-procés. Besides, the interest among political scientists on the subject (measured every six months) correlates with the main political events in the crisis. Therefore, during the pre-procés period, the highest level of interest appears in the second semester of 2010, following the ruling of the Constitutional Court on the Statut of Autonomy (June 2010). There is also an upsurge of attention in the second half of 2012, coinciding with the events of the first massive Diada demonstration in September, and the start of the procés stage with the election of November 2012. During the procés period, the peaks in Fig. 3 coincide with three major political events—the campaigns of the 2014 referendum, the 2015 Catalan election, and the events that resulted in the October 2017 referendum and the unilateral declaration of independence. The second semester of 2017 also coincides with the start of the post-procés period and the application of the article 155 of the Spanish Constitution and the regional elections of 20 December 2017.

Sides supported in articles (by semester) (2010–2018). Note: The vertical axis represents counts. The horizontal axis represents semesters (first and second) within a year. Averages capture the variation across the three main periods analysed in the article. In the figure, these roughly correspond to the biannual sections: pre-procés (2010–1 to 2012–1), procés (2012–2 to 2017–2), and post-procés (2018) periods.

The predominance of partisan interventions would be more obvious if it were not for the predominance of non-aligned interventions over partisan ones in some of the periods of higher salience of the issue. This is the case of the second semesters of 2012 and 2015, where the proportion of non-partisan interventions reaches 53.5% and 52.5%, respectively. We can explain this by the fact that these periods coincide with electoral campaigns and that a substantial part of those interventions corresponds to some kind of pre- or post-electoral analysis (42.9% and 61.9% in 2012 and 2015, respectively). Also, in the moments of more intense contentiousness, during the second half of 2017, most of the non-identifiable interventions (58.3 percent, about seven texts) corresponded to articles focusing on the December 2017 election. In sum, these non-aligned articles published during electoral or post-electoral periods account for almost 40 per cent of the total in the non-identified or neutral categories.

It is also remarkable how partisan and non-partisan interventions differ in their intentions to influence on other actors’ behaviour by proposing courses of action (prognostic approach). While only 19.4% of the opinion pieces classified as “non-identified” contains such recommendations, this percentage is significantly higher among partisan interventions. Therefore, a great majority of pro-independence and third-way articles (69.3 and 93.8, respectively) adopt a prognostic approach, as well as a high proportion of neutral texts (61.3%). In contrast, only 25% of constitutionalist articles qualifies as prognostic, which is probably a reflection of the eminently reactive stance adopted by actors on this side of the conflict, which privileged the conservation of the status quo.

Opinion leaders for the independence cause

Figure 4 further shows the asymmetric distribution of individual contributions by political scientists participating in the Catalan secession public debate. Of the 53 authors identified, just one of them (who we will call “PS1”) produced 24% of the articles. Another three (labelled PS2, PS3, and PS4) were responsible for 35.2%. And four other individuals produced 19.4% of the articles. The rest of the texts (21.3%) spread across forty-five different authors. Therefore, what Spanish political scientists say about the Catalan independence crisis is greatly dependent on these eight highly active and more visible individuals, who account for almost 80% of all interventions. The fact that most of these people enjoyed regular columns in the analysed newspapers suggests that the asymmetric pattern in interventions and the likelihood to become an opinion-maker is not just a matter of personal motivation or interest in the topic, but clearly depends on the role of the media in giving voice to specific individuals, who in many cases exhibit opinions quite close to the outlet’s editorial line.

Sides supported by each individual author (2010–2018). Note: The horizontal axis represents each of the 53 different authors analysed. The bars represent the stacked total number of articles written by every individual classified on every category of the “Side” variable (“Pro-independence”, “Constitutionalist/anti-independence”, “Third way”, “Neutral”, and “Not identifiable”).

The hypothesis about the prevalence of partisan interventions at the individual level is greatly confirmed too. Of the 53 authors identified, 48 of them have produced at least one article explicitly taking sides on the conflict, and in the case of 42 authors, they adopted a partisan approach in at least half of their interventions. In contrast, only 21 authors wrote some non-partisan text (neutral or not identifiable), and 16 authored both partisan and non-partisan articles.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the positions taken by the authors. First, we observe that the group of more publicly active scholars (those above ten articles along the nine-years period) combine to some extent partisan and non-partisan interventions, though distributions vary across individuals. Thus, positions are predominantly partisan for only half of this group. These data only partially confirm our second hypothesis about the predominance of partisan stances among more visible scholars.

We also observe differences in terms of the consistency or homogeneity of partisan positions. Thus, the three scholars with more interventions (PS1 to PS3, who jointly accumulate almost half of the articles) are clearly aligned with pro-independence positions. Jointly, they are responsible for 82.5% of all pro-independence articles, which makes them key opinion figures of this camp in the public debate. In this respect, we must also mention that the involvement of two of these authors went far beyond media interventions, as they also occupied relevant positions in the institutional structure created to support the secessionist process.

Furthermore, while most pro-independence texts by PS1 and PS3 are concentrated during the procés period (92.3% and 92.9%, respectively), in the case of PS3 the articles aligning with pro-independence positions spread over the whole period. This individual is also remarkable because of the discourse eminently prognostic (81.4% of the entire production) and focused on providing clear theoretical arguments for secession, even before the ruling of the Spanish Constitutional Court in 2010. This makes this individual the only one in our study that could probably raise to the status of public agenda setter, in the sense that he is capable of raising awareness on issues or paths of action that later would be followed by main political actors.

The homogeneity of partisan stances within this group of most active, pro-independence individuals contrasts with the less homogeneous positions of the rest of authors with more than ten articles (PS4 to PS8). Apart from the clear opposition (except for PS4, which is ambiguous in some articles) towards secession, their positions vary along time without any clear pattern of evolution.

Politically oriented experts

With respect to the compatibility of partisanship and academic standards, the data confirm that most articles (61.2%) contain academic elements (concepts, empirical evidence, mention to political science theories, or authority arguments). This proportion is rather stable across partisan and non-partisan interventions (59.7% among those labelled as pro-independence, 61.4 among articles taking the constitutionalist side, 62.5 for those advocating for some kind of third-way option, and 66.7 in articles that did not opt for any side of the conflict). Only in the case of the articles categorised as neutral, the proportion of texts using academic elements was significantly much lower (38.1%).

Therefore, from the roles mentioned in the theoretical section (scientist/expert, politically oriented expert, and partisan), it is the second one which clearly dominates the others, with about one-third of all interventions fitting in this category. However, there is also a significant proportion of articles (28%) where participants adopt the role of scientist/expert. In line with our categorisation, 83% of the articles where the author adopts such role use exclusively an analytical approach.

The rest of articles does not include any academic content, and they are divided between plainly partisan interventions (which amount to a remarkable 22.4%) and interventions where the author acts as a “non-partisan commentator” (16.4%).

The influence of the media system

Finally, we examine our third hypothesis—that interventions appear according to the media’s sympathies for different sides of the conflict. Figure 5 shows mixed evidence on this. In the case of newspapers exclusively published in Catalan language (Ara, Avui, El Punt, and El Punt Avui), we observe that partisan opinion pieces authored by academic political scientists are overwhelmingly aligned with pro-independence positions. The same applies in the case of constitutionalist positions, to Abc and El Mundo, two Madrid newspapers with a conservative editorial line (Chaqués et al., 2015).

Distribution of articles with a political positioning by newspaper (2010–2018). Note: The figure represents the distribution of pieces (counts) across newspapers during the studied period. Though pieces labelled as “neutral” are not considered partisan, they have been included since they imply a political positioning.

We also observe that El Periódico and El País, two newspapers opposed to the secession but with liberal editorial lines, published most of the articles showing a neutral and third-way position. Figure 5 also shows that a significant proportion of the pieces in these newspapers (46.2% and 55.2%, respectively) corresponds to articles labelled as constitutionalist or pro-independence. However, regarding the latter, it is also remarkable how in these two newspapers pro-independence articles disappear during 2017 (in El País during the second half of the year), coinciding with the moments of highest political tensions. In the case of El País, most pro-independence articles were written by one of the highly active authors mentioned in the previous paragraphs, who was a regular columnist in the newspaper. The disappearing of pro-independence articles written by political scientists coincided with the sacking of this columnist in the Autumn of 2017.

Regarding La Vanguardia, we observe a high proportion of pro-independence articles (83.3% of all pieces published in this newspaper). The author of most of them (37 out of 40) was one of the highly active authors mentioned in a previous section, who was a regular columnist in this newspaper during the period we analyse. It must be noted that though La Vanguardia’s editorial position on the issue of Catalan independence changed over time—from a sympathetic treatment of the Catalan government’s claims until 2013 to an anti-independence stance in the following yearsFootnote 8—this newspaper kept publishing the articles written by its pro-independence columnist during the whole period.

In sum, the previous evidence partially supports our expectation about the grouping of articles in outlets according to their political positioning. However, this occurs mostly in those newspapers with more polarised positions on the issue, while more liberal newspapers are to some extent open to contributions that do not entirely fit with their editorial lines.

Conclusions

The evidence presented in this article has shed light on a quite neglected topic: the role (or roles) political scientists play in highly contentious public debates. As Real-Dato and Verzichelli (2021) show in the introduction to this special issue, the roles political scientists adopt in the public debates may affect their visibility and the perceived social relevance of the discipline before the general public. In this respect, such perception may result when political scientists use their disciplinary expert knowledge to enlighten the public about hidden or scarcely known aspects of public problems or political conflicts. But they can also be relevant by helping to support and legitimise specific political positions or alternatives, even if such approach implies some friction with scientific standards.

In the highly conflictual political debates around the Catalonian independence question, the partisan role trumps the scientific/expert “hat”. Though political scientists’ partisan interventions may usually appear in tandem with academic elements, mentioning specialised concepts, empirical evidence, or scientific theories, these elements are subordinated. In this type of interventions, the authors mostly appear in their condition of members of a political community than as members of the scientific community. To some extent, such approach is understandable (both in normative and behavioural terms) when an individual’s basic political identity and beliefs are in question.

The article has also offered evidence on the role the mass media can play as unavoidable intermediaries between political scientists and the public. First, they affect the public visibility of political scientists in general, as the huge differences in the presence of political scientists across newspapers demonstrate. Second, media selectivity also contributes to accentuate the asymmetries observed in the public participation of political scientists, by providing some of them a privileged access to the public in the form of regular slots. Third, mass media also reinforce the prevalence of partisanship in the public interventions of political scientists, through the selection of individuals with partisan opinions in tune with their editorial lines. Finally, we have also demonstrated that scholars’ media visibility is not completely dependent on adopting partisan stances, since media outlets also demand non-politicised analyses.

In sum, this article has shown that highly contentious political debates may represent an opportunity for political scientists to increase their visibility and social relevance before the public. However, there is also the danger that the combination of partisan arguments and scientific elements might erode the legitimacy of political science knowledge before that same public. In the end, the problem could be that what helps some political scientists to become socially (and politically) relevant could also negatively affect the social relevance of political science as a disciplinary knowledge. Further research on the topic should shed light on this crucial issue.

Notes

The survey was carried out in 2018 in the context of the COST Action “Professionalisation and Social Impact of European Political Science” (PROSEPS) (http://proseps.unibo.it/proseps/). The survey was carried out in 37 European countries (plus Israel and Turkey) among academic political scientists. The total number of respondents was 2354.

This would require an entirely different research design, analysing participation of academic political scientists in the context of all the interventions in this public debate. However, this is beyond our purposes in this article.

Spain is classified by Hallin and Mancini (2004) among pluralist polarised systems. These systems “[tend] to be associated with a high degree of political parallelism: newspapers are typically identified with ideological tendencies, and traditions of advocacy and commentary-oriented journalism are often strong.” (2004: 61). Also, “the press is marked by a strong focus on political life (…). Instrumentalization of the media by the government, by political parties, and by industrialists with political ties is common. Public broadcasting tends to follow the government or [parliament] (…). The state plays a large role as an owner, regulator, and funder of media, though its capacity to regulate effectively is often limited.” (2004: 73).

See, for instance, the manifesto of the unitary pro-independence coalition Junts pel Sí (Together for Yes) for the 2015 Catalan election (Junts pel Sí, 2015). Junts pel Sí was integrated by ERC and one of the parties that formed the disappeared CiU, Convergència Democrática de Catalunya (CDC).

We used as a reference the audience surveys produced three times a year by the AIMC (Asociación para la Investigación de los Medios de Comunicación – Association for Mass Media Research) (http://reporting.aimc.es/index.html#/main/diarios, accessed 26/04/2020).

The watershed between both editorial lines was marked by the replacement of the newspapers’ director in December 2013, who two years later founded a new pro-independence newspaper (see “La Vanguardia cambia de director para descolgarse del proceso soberanista”, Eldiario.es, 13/12/2013, available at https://www.eldiario.es/politica/Vanguardia-director-descolgarse-proceso-soberanista_0_206829738.html (accessed 01/06/2020)).

References

Álvaro, F.-M. 2019. Ensayo general de una revuelta: las claves del proceso catalán. Barcelona: Galaxia Gutemberg.

Bandola-Gill, J., M. Brans, and M. Flinders. 2021. Incentives for impact: relevance regimes through a cross-national perspective. In Political science in the shadow of the state: Research, relevance & deference, ed. R. Eisfeld and M. Flinders. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Barrio, A., and B. N. Field. 2018. The push for independence in Catalonia. Nature Human Behaviour 2018 (2): 713–715. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0439-8.

Barrio, A., and J. Rodríguez-Teruel. 2017. Reducing the gap between leaders and voters ? Elite polarization, outbidding competition, and the rise of secessionism in Catalonia. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (10): 1776–1794.

Büchel, F., E. Humprecht, L. Castro-Herrero, S. Engesser, and M. Brüggemann. 2016. Building empirical typologies with QCA: Toward a classification of media systems. International Journal of Press/politics 21 (2): 209–232.

Chaqués-Bonafont, L., A.M. Palau, and F.R. Baumgartner. 2015. Agenda Dynamics in Spain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Coll, J., I. Molina, and M. Arias-Maldonado, ed. 2018. Anatomía del procés: Claves de la mayor crisis de la democracia española. Barcelona: Debate.

Flinders, M. 2013. The tyranny of relevance and the art of translation. Political Studies Review 11 (2): 149–167.

García, L. 2018. El naufragio: la deconstrucción del sueño independentista. Barcelona: Peninsula.

Guest, G., K.M. MacQueen, and E.E. Namey. 2012. Applied thematic analysis. Los Angeles: Sage.

Guinjoan, M., T. Rodon, and M. Sanjaume. 2013. Catalunya, un pas endavant. Barcelona: Fundació Josep Irla / Angle Editorial.

Hallin, D.C., and P. Mancini. 2004. Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jenkins-Smith, H.C., D. Nohrstedt, C.M. Weible, and K. Ingold. 2017. The advocacy coalition framework: An overview of the research program. In Theories of the Policy Process, ed. C.M. Weible and P.A. Sabatier, 135–171. Boulder: Westview Press.

Junts pel Sí. 2015. Programa electoral. Barcelona: Junts pel Sí. Retrieved from: https://juntspelsi.s3.amazonaws.com/assets/150905_Programa_electoral_v1.pdf (accessed 18/08/2020).

Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

López, J., and M. Sanjaume-Calvet. 2020. The political use of de facto referendums of independence: the case of Catalonia. Representation 56 (4): 501–519.

Majone, G. 1989. Evidence, argument and persuasion in the policy process. New Haven: Yale University Press.

March, O. 2018. Los entresijos del ‘procés.’ Madrid: Los Libros de la Catarata.

Martí, J. 2018. Cómo ganamos el proceso y perdimos la república. Barcelona: EDLibros.

Martínez, G. 2016. La gran ilusión: mito y realidad del proceso indepe. Barcelona: Debate.

Mas, A. 2020. Cabeza fría, corazón caliente: el procés en primera persona. Barcelona: Península.

Mercier, H., and D. Sperber. 2017. The Enigma of reason. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

PSOE. 2013. Un nuevo pacto territorial: la España de todos. Declaración del Consejo Territorial. Granada, 6 Julio 2013. Madrid: PSOE.

Real-Dato, J., and L. Verzichelli. 2021. In search of relevance: European political scientists and the public sphere in critical times. European Political Science.

Requejo, F., and M. Sanjaume. 2013. Recognition and political accommodation: from regionalism to secessionism: The Catalan case. Barcelona: Grup de Recerca en Teoria Politica, University Pompeu Fabra.

Le Roux, B., and H. Rouanet. 2010. Multiple correspondence analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Schneider, A.L., and H. Ingram. 1997. Policy design for democracy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Schreier, M. 2014. Qualitative content analysis. In: Flick, U. (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis, pp. 170–183. London: Sage.

Shapiro, M.J. 1984. Introduction. In: Shapiro, M. J. (Eds.), Language and politics, pp. 1–12. New York: New York University Press.

Tsirbas, Y., and L. Zirganou-Kazolea. 2021. Greek political scientists under the crisis and the case of the Greek bail-out referendum: an intellectual barricade protecting the status quo? European Political Science.

Verzichelli, L., J. Real-Dato, and G. Vicentini. 2019. Social visibility and Impact of European Political Scientists. Proseps Working Group 3 Report. Retrieved from: http://proseps.unibo.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/WG3.pdf (accessed 30/12/2020).

Vicentini, G., and A. Pritoni. 2021. Down from the “Ivory Tower”? Not so much…Italian political scientists and the constitutional referendum campaign. European Political Science.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Luis de la Calle, Guillermo Rico, all the participants in the Working Group 3 of the PROSEPS COST Action, as well as the reviewers and editors at European Political Science, for their helpful comments and suggestions on previous versions of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Real-Dato, J., Rodríguez-Teruel, J., Martínez-Pastor, E. et al. The triumph of partisanship: political scientists in the public debate about Catalonia’s independence crisis (2010–2018). Eur Polit Sci 21, 37–57 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00341-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00341-x