Abstract

Democratic theory argues that individuals should have their policy preferences equally represented in politics. Research on opinion congruence has often found, however, that political parties’ views are more likely to align with those of higher-income and higher educated citizens. We argue that this conclusion does not account for heterogeneity among parties. Based on an integrated dataset containing the positions of over 1,700 Belgian citizens and 11 Belgian parties on over 120 policy statements, we examine how opinion congruence inequality between privileged and underprivileged people varies between parties. We find that left-wing parties align more with underprivileged citizens than they do with privileged citizens on economic issues, while the opposite holds for right-wing parties. On cultural issues, however, both left- and right-wing parties better represent the preferences of privileged people. The exception is the radical right party Vlaams Belang, which on the cultural dimensions better represents the views of underprivileged voters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite manifold debates about the style, focus, and direction of political representation, there is widespread agreement that, “unless mass views have some place in the shaping of policy, all talk about democracy is nonsense” (Key 1961, p. 7). It is for this reason that high levels of agreement between voters and representatives, in what has been referred to as “opinion congruence” (Walgrave and Lefevere 2013), are seen as an indicator of a healthy democracy (Diamond and Morlino 2005). Equally important, however, is that all citizens have their voices equally heard. Nevertheless, as societal resources are unequally distributed, a growing concern has emerged that some voter groups’ greater access to, and control over, certain resources translates into increased levels of opinion congruence. In almost all cases, this access to resources is measured through a person’s income or level of education (Gilens 2005; Lesschaeve 2017). The possibility that some people have their opinions better represented that others has spurned on a growing body of literature on how preference representation differs between social groups. Studies in this field generally find that the voices of the affluent or higher educated carry more weight than those of less privileged citizens or lower class voters (Flavin 2012; Giger et al. 2012; Schakel and Hakhverdian 2018).

In most Western democracies, political parties are the central actors that translate public opinion into public policy, as they develop policy programmes from which voters are able to choose on election day (Dalton 2017). Given the importance of parties in what is referred to as the “responsible party model” (Adams 2001), it is surprising that relatively little attention has been given to the role of political parties in scholarly efforts to explain unequal opinion representation. If one looks at the impressive body of research on inequality in representation of the past two decades, one would come to the conclusion that inequality is seemingly pervasive and a constant in government policy-making. Only recently have scholars, primarily focussing on the US, begun to take into account parliamentary or government configuration (Hillen and Steiner 2020; Rosset and Kurella 2020; Schwander et al. 2020).

This study contributes to these efforts by examining how parties moderate inequality in opinion congruence between privileged (i.e. the higher educated and higher incomes) and underprivileged citizens (i.e. the lower educated and lower incomes). Does left–right ideology still matter, with parties on the left aligning more with the views of the underprivileged, and parties on the right sharing the preferences of the privileged? Is this relation dependent on issue dimension (Lefkofridi et al. 2014)? And what is the role of radical right parties, which seem to upend the classic distinction between the left and the right (Kitschelt and McGann 1997)?

This study explores the theoretical foundations of these research questions and answers them on the basis a large dataset containing the policy preferences of over 1700 Belgian voters and 11 Belgian parties on over 120 policy statements collected in the run-up to the 2014 Belgian elections. As a small consociational democracy, which arguably encourages party ideological convergence, Belgium represents a critical case in which to examine whether parties matter in opinion congruence inequality. The results show that this inequality is indeed related to party ideology, but that this relation also depends on issue dimension. On economic issues, the policy stances of left-wing parties align more with those of underprivileged voters than with those of privileged voters, while an opposite pattern is observed for right-wing parties. On cultural issues, we find both left- and right-wing parties favouring the views of privileged voters. Finally, the radical right party Vlaams Belang deviates from this trend by showing higher levels of opinion congruence with the lower educated and less affluent on cultural issues. While these findings show that parties very much matter in opinion congruence inequality and that, depending on the parties in power, inequality can be in favour of the underprivileged, they also suggest that the latter have no option in the Belgian party system that sides with their views on both dimensions.

Parties, issue dimensions and inequality in opinion congruence

Scholars have identified various mechanisms that result in political elites holding stances that are more congruent with those of privileged voters: lobbying, financial contributions, voter turnout, and descriptive biases among political elites. With lobbying, lobbyists seek to establish shared perspectives with politicians through socializing, friendship networks, revolving-door employment, the use of think tanks to formulate complex policy positions, and even by the act of drafting legislation for politicians (Winters and Page 2009). Financial contributions—political donations and spending on behalf of political elites—primarily serve a selection purpose, according to what has been labelled the “ideological sorting hypothesis” (Bronars and Lott 1997). These contributions do not try to change the preferences of political elites, but rather serve as a means of helping politicians with congruent policy preferences win (re)election. Regarding turnout, studies have consistently pointed towards underprivileged citizens being less likely to vote in elections than privileged citizens are (Gallego 2010; Steinbrecher and Seeber 2011).

Given the corporatist interest group system (van Gerven and Beckers 2009), strict campaign finance laws (Weekers et al. 2009), and compulsory voting in Belgium (De Winter and Johan Ackaert 1994), the most relevant mechanism behind inequality in opinion congruence in the present study is arguably the fact that political elites tend to come predominantly from privileged groups. In Belgium, just like in most Western democracies, between 70 and 90 per cent of MPs have a college degree (Bovens and Wille 2017). In the USA, the median individual net worth of members of Congress is six times that of average Americans (Carnes 2012). Due to their shared background, politicians view the world in a similar way, resulting in similar policy preferences. As a result, underprivileged citizens experience lower levels of opinion congruence. The literature on the link between substantive and descriptive representation supports this assertion (see for instance Saalfeld and Bischof 2013), in spite of examples where upper-class politicians defend the interests of the underprivileged.

If there are sufficient reasons to expect inequality in opinion congruence to occur at all, how then might we expect political parties to moderate this inequality? Intuitively, one might apply the classic left–right divide to expectations of opinion congruence inequality. Starting with the seating arrangement in the French National Assembly of 1789, where the King’s supporters sat to right of the Assembly’s president, and supporters of the revolution to his left, left-wing parties have been traditionally associated with the interests of the underprivileged segments of society, while the right has been seen as defenders of the wealthy (Bobbio 1996).

However, this view would be overly simplistic and ignore the multidimensional nature of issue positions. Public opinion studies have shown that citizens organize their policy stances on two issue dimensions (Kriesi et al. 2006). The first is the economic dimension, which captures conflicts on the role of the government in the economy and the redistribution of wealth. The second dimension revolves around the cleavage between cosmopolitan and progressive values on one side and more traditional and nationalistic values on the other. While there is debate on whether citizens treat these dimension as independent, enabling any combination of preferences, a self-interested view would expect some combinations to be more prevalent than others (Werfhorst and Graaf 2004). Specifically, such a view argues that underprivileged individuals are much more susceptible to proposals of government involvement in the economy and the redistribution of wealth, as they stand to gain more from such policies, in contrast to privileged citizens. While underprivileged voters are more likely do adopt left-wing views on the economic dimension than privileged voters are, this relation is reversed on the cultural dimension. Again, these positions make sense from a self-interest perspective. For instance, the influx of immigrants increases competition on the job market (Kriesi et al. 2012). In addition, higher levels of education induce cosmopolitan values through a greater familiarity with other cultures (Stubager 2008).

On the supply side of politics, most studies find that political parties organize their policy positions along a single policy dimension that encompasses both economic and cultural issues (Van Der Brug and Van Spanje 2009). Consequently, parties often combine left/-right-wing policy positions on economic issues with tolerant/conservative views on cultural issues (Rovny and Edwards 2012). Combining the assumptions on party and citizens’ policy views, it is predicted that on economic issues opinion congruence inequality is in favour of the privileged among right-wing parties, while among left-wing parties, inequality is reversed and in favour of underprivileged voters (Hypothesis 1a). On cultural issues, this relation is expected to be reversed, with right-wing parties favouring the preferences of the underprivileged and left-wing parties being more congruent with privileged voters (Hypothesis 1b).

While the role of political parties and their ideological leanings in structuring opinion congruence inequality might appear obvious, including in the eyes of the public (Freire and Belchior 2013), it is worth considering the arguments of those suggesting that ideological labels have increasingly less to do with the adoption of distinct issue positions and by extension opinion congruence. These arguments revolve around the transformation of political parties. After the vote was extended to the working class and to women, mass parties emerged, which focused on the representation and mobilization of a well-defined social group (Duverger 1972). As mass parties gradually began to evolve into catch-all and cartel parties in the late ‘80s and ‘90s, the sharp ideological distinctions between parties began to fade and gave way to programmatic convergence. Instead of advocating for a comprehensive transformation of society in service of their constituents, parties started to preach social amelioration, which did not alienate the voters outside their “class gardée” (Mair 1997). One of the main driving forces behind this evolution was the enlarging of the middle class, of which both traditional working class and capitalist parties sought to win support (Thomas 1980). Down’s (1957) model of electoral competition predicts that parties lose their ideological distinctiveness once they converge on the median voter. Indeed, convergence on centrist positions is strategy that has been shown to pay off electorally, both in two- and multiparty systems (Adams and Somer-Topcu 2009). The idea of ideological converge is also rooted in the spirit of the times, as with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the poorer performance of planned socialist economies, there seemed to be no alternative to market-based liberal democracy (see Fukuyama 1992). In other words, policy objectives are viewed as something commonly agreed upon, and party competition relates itself primarily to which party is most capable to reach those objectives. While this does not inherently make policy, decisions favour the preferences of the privileged over the underprivileged, it does render parties an irrelevant factor in explaining inequality in opinion congruence.

While there has been some evidence to suggests that parties have indeed converged in terms of issue positions (Evans and Tilley 2012), the story does not end here. When parties converge, they lose part of their distinctiveness and their “unique brand”, and by doing so pave the way for the success of newer parties that are willing to adopt more extreme positions and positions abandoned by the mainstream (Kitschelt and McGann 1997). Indeed, the electoral benefits of moderation only apply to large traditional parties, while smaller parties profit from setting themselves apart (Abou-Chadi and Orlowski 2016). As a result, the loss in programmatic choice by mainstream parties converging on the centre is usually offset by smaller parties filling those ideological vacuums. Furthermore, the success of these smaller parties often makes mainstream parties reconsider moderation. In other words, ideological converge should not be overstated in the presence of mechanisms of divergence.

One group of parties that emerged in the wake of ideological convergence is the Radical Right party (RRP). This party type is defined by a core ideology that revolves around a combination of three elements (Mudde 2007). The first is nativism, which aspires to the ideal of cultural homogeneity. The second is authoritarianism, which stresses the need to strictly enforce order in society, and the third is populism, which views society as being divided between the people and the corrupt elite. RRPs have traditionally sought to court voters by adopting more extreme views on cultural issues than mainstream parties, especially on topics like immigration (Kitschelt and McGann 1997). Initially, this right-wing socio-cultural stance was combined with a right-wing view on economic and social welfare matters (Kriesi et al. 2006), rendering them simply a more radical version of mainstream right-wing parties. Over the past decade, however, RRPs have begun to adopt and stress left-wing positions on economic issues, expanding their opposition to globalization to include not only the cultural consequences, but also the economic ramifications (Lefkofridi and Michel 2014). RRPs and their “welfare chauvinism”, in which welfare benefits are to be limited to the “own people” (Mudde 2007), have become an increasingly relevant force in West-European politics (Schumacher and van Kersbergen 2016). While there is debate on whether RRPs are genuinely left-wing or more centrist on economic issues (see Mudde 2007), it stands to reason that such parties can be expected to break away from the unidimensional belief system of mainstream parties. As such, RRPs are expected to deviate from the patterns predicted in Hypothesis 1.

To summarize, we have the following expectations on inequality in opinion congruence for RRPs. On cultural issues, similar to other right-wing parties, RRPs are expected to have policy positions closer to those of underprivileged voters than those of privileged voters. On economic issues, inequality in opinion congruence is expected to be smaller or even reversed in the favour of unprivileged voters, when compared to other right-wing parties. This is our second hypothesis.

Data and methods

To test these expectations, two sets of data from the Belgian regional, federal, and European elections of May 2014 are used. Belgium is small consociational federation in Western Europe and mainly consists of two linguistic regions, Flanders and Wallonia (Deschouwer 2009). In the country, party convergence is arguable greater, as its relatively small size makes it more subject to the forces of globalization, and its EU membership has further reduced the leeway of political elites to shape the country’s policies. In addition, Belgium is known as a consociational democracy, in which elites engage in cooperation to reduce conflict (Lijphart 2012). This too has arguably dampened political polarization and reduced rather than increased the ideological distances between parties. As a result, Belgium is a case where partisan convergence can be expected to be greater than in other countries, thus representing a critical test for the assertion that parties matter when it comes to inequality in opinion congruence.

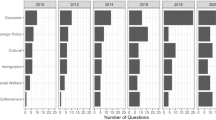

The first dataset is an online survey of 1768 eligible Belgian voters, after excluding respondents with incomplete information, conducted in March 2014. Respondents were quota sampled from a large panel managed by TNS Dimarso in order to make sure that the sample as a whole reflects the Belgian population in terms of age, gender, and level of education. The questionnaire included large batteries of policy statements, which touch upon topics relevant for the upcoming three elections. While the statements for the federal and European level were identical for all respondents, the regional statements were customized to reflect regional differences in what the topical issues were in 2014. In the end, this study can rely on the answers of Flemish voters on 127 policy statements and the answers of Walloon voters on 134 statements. Answering such a long list of policy statements can results, however, in survey fatigue. Specifically, when online surveys take over 20 min to complete, responses have been found to become increasingly inaccurate (Galesic and Bosnjak 2009). To prevent this, the survey was split up into two waves, with the same respondents being surveyed twice, with one or two days in between. This limited the average length of each wave to roughly 15 min.

The second dataset is a party leadership survey. Concurrent with the voters’ survey, the leaders of all eleven political parties in Belgium were contacted that had at least one representative in either the regional or national parliament before the 2014 elections and were asked to answer the same policy statements as those in the voter survey. The Belgian party landscape is split along the Flemish/Francophone linguistic divide (De Winter et al. 2006), resulting in our party leadership survey to consist of six Flemish and five Francophone parties. The eleven parties come from six party families. From the environmentalist family, there are Groen (Green), and Ecolo (Ecologists), and from the social democrats, there are Sp.a (Socialistische Partij Anders, Socialist Party Differently) and PS (Parti Socialiste, Socialist party). The christen democrats are represented by CD&V (Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams, Christian Democratic and Flemish) and CDH (Centre démocrate humaniste, Humanist Democratic Centre). From the liberal party family, there are Open VLD (Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten, Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats) and MR (Mouvement Réformateur, Reformist Movement). The FDF (Front démocratique des francophones, Democratic Front of Francophones) and N-VA (Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie, New Flemish Alliance) are two regionalist parties. Finally, there is the extreme right/regionalist/populist Vlaams Belang (Flemish interest).

The answers of the leadership are taken as the positions of the entire party. This assumption is merited in the Belgian context due to the strong control leadership exerts over matters such as candidate list formation (Andeweg and Thomassen 2011). Even in disagreement, party MPs are likely to follow the leadership’s lead, as is evident from the extreme degree of party cohesion during parliamentary votes (Depauw 2003).

To summarize, the strength of the datasets used here lies in the fact that they contain comparable party and voters’ positions on a large number of concrete issues to measure the congruence of their opinions. This approach has been shown to be vastly superior to other methods such as the reliance on the left–right scale, which has been found to be only weakly related to voters’ concrete issue positions (Freire and Belchior 2013). Both party leaderships and voters could either ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’ with a policy statement. While more limited than the classic Likert-scale, Rabinowitz and Macdonalds (1989) argue that additional answering categories are more likely to reflect the importance or intensity with which a position is held instead of positional nuance.

The dependent variable is the difference in opinion congruence between the privileged and underprivileged. To distinguish between these two groups of respondents, information is used on their income and education, included in the voter survey. For education, voters are divided into three categories: lower educated voters only have an elementary school degree, middle educated consists of those who have finished their secondary education, and higher educated are voters who have a graduate or university degree. Voters’ income is measured as the decile category they belong to when taking into account their total household income. These income deciles too were grouped into three categories, the first containing the first three income deciles, the second income deciles four to seven, and the third income deciles eight to ten. These variables were combined to calculate socio-economic status (SES) by adding them up. Respondent are considered privileged when they belong to the top two SES categories, and underprivileged when they belong to the bottom two categories. Of the 1768 respondents in the sample, 697 (39 per cent of the sample) belong to the underprivileged group while the privileged category consists of 592 respondents (33 per cent of the sample). Finally, the middle category consists of 479 respondents (28 per cent of the sample). While previous studies have often relied on either income or education to identify social strata (Flavin 2012; Giger et al. 2012; Schakel and Hakhverdian 2018), it is argued here that a better approach is to conceptualize them as two sides of the same coin, i.e. access to socially valued resources (see Bourdieu 1986).Footnote 1

The purpose of this study is to analyse whether some parties have views that align more closely with those of privileged or underprivileged voters. The primary interest here is how the supply side of politics affects inequality in opinion congruence rather than the choice made by citizens during elections (see Lau et al. 2014). For that reason, the first step in calculating the dependent variable is to measure, for each party position how many privileged and underprivileged respondents share that position, regardless of whether respondents are that party’s supporters or not. However, with Belgium’s separate Flemish and Francophone party system, party competition for seats happens in each region separately, even for the federal and European parliaments. Therefore, when calculating the agreement with Flemish and Francophone party positions, the sample is limited to Flemish and Francophone respondents, respectively.

In a second step, the level of agreement among unprivileged respondents is subtracted from the level of agreement among privileged respondents. The resulting variable, inequality in opinion congruence, is the dependent variable in our analyses. This variable is positive when a party position aligns more with the views of the affluent and the higher educated, and negative when a party position caters more to the preferences of the underprivileged segments of society. The data are stacked so that the unit of analysis is the party*statements combination. This stacking procedure artificially inflates the number of observations, and failing to account for this would lead to underestimated standard errors, and an overestimation of statistical significance (Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal 2012). Therefore, when modelling the data, a multilevel regression model is employed with random intercepts for the party and policy statement level. The main downside of the above-described approach is the inability to take into account potential heterogeneity in policy preferences among those with high and low levels of SES. Therefore, robustness checks were performed in which the analyses were rerun, after splitting the data by gender and age. These checks, reported in the Online Appendix, show results that are in line with the findings reported in the next section.

A precondition to inequality in opinion congruence is the presence of diverging policy views between the privileged and underprivileged (Soroka and Wlezien 2008). If both groups agree on what the policy outcome should be, the potential for inequality in opinion congruence to occur at all, let alone to vary by party, is very limited. In other words, it makes little sense to analyse inequality on issues where there is a consensus across groups of voters. Therefore, the analyses are limited to statements on which there is substantial disagreement on the policy objective between privileged and underprivileged citizens. Such statements are identified by calculating the absolute difference between the percentage of privileged voters and the percentage of underprivileged voters who agree with a policy statement. On the basis of the median value of this difference (6%), the sample is divided into statements on which there is little disagreement and statements on which there is substantial disagreement. The analyses focus solely on the latter.Footnote 2

Figure 1 visualizes opinion congruence inequality. Every bar in the figure represents one policy statement, and the height of each bar shows the degree of opinion congruence inequality. Positive values indicate that congruence is higher for privileged voters, while negative values mean that congruence is higher for underprivileged voters. The statements are placed in order of increasing inequality in favour of privileged citizens. From the graph, it is clear that in most cases, 55.3% to be precise, inequality in opinion congruence favours the upper classes. Inequality in favour of the privileged is largest on the policy statement “People over 65 must be able to continue to travel for free by bus or tram” for the parties Groen, CD&V, Open VLD, N-VA, Vlaams Belang, who all opposed this proposal. This opposition was shared by 45 per cent of privileged voters, but only by 19 per cent of the underprivileged.

On the statement “The living wage must rise”, one can find the greatest degree of inequality favouring the underprivileged for the parties Groen, Sp.a, CD&V, Open VLD, N-VA, and Vlaams Belang, who all supported the proposal. This is in line with the preference of 79 per cent of underprivileged voters, but with only 49 percent of privileged voters. The complete overview of inequality in opinion congruence for every party-statement combination can be found in the Appendix.

The first independent variable is parties’ left–right positions, which was derived from the Comparative Candidate surveyFootnote 3 conducted just after the elections of May 25. Each candidate was asked to place their own party on the left–right scale, and a party’s position is the average of those placements. Figure 2 shows the place of the eleven parties on the left–right scale. The second independent variable indicates the policy dimension to which a policy statement belongs. Each statement was assigned to the economic or cultural dimension, but a third category was added for statements that did not clearly fit either dimension.Footnote 4 The coding procedure followed the distinction between issue dimensions of Kriesi et al. (2006). The economic dimension represents the classic opposition between the welfare state and economic liberalism, while the cultural dimension captures issues related to nationalism versus cosmopolitism and law and order.

Hypothesis 2 predicts that radical right parties deviate from patterns predicted in Hypothesis 1, and instead better represent the underprivileged, both when it comes to issues on the economic and on the cultural dimension. In the Belgian party system, only the party Vlaams Belang (VB) can unambiguously be identified as a radical right party. The literature on RRPs is in agreement that VB has an ideology that is centred on the protection and promotion of the ‘Flemish’ culture, a strong emphasis on the law and order, and is infused with the idea that ‘the people’ need to liberated from an elite class that threatens them economically and culturally (Mudde 2007; Pauwels 2011). Therefore, testing Hypothesis 2 will entail the comparison of the patterns of opinion congruence inequality for VB with those of the other ten parties.

The analyses control for statement ignorance. It is possible, even likely, that some respondent positions amount to nothing more than what Converse (2006/1964) referred to as ‘nonattitudes’, attitudes that are not real and emerge solely because people where asked a question in a survey. While the aggregation of individual opinions in the calculations will arguable help ameliorate this problem (Page and Shapiro 1992), it can be reduced further by controlling for differences in how well the privileged and underprivileged understood the statements. While the survey did not include a precise measure of how clear each policy statements was, it can be approximated by looking at the number of respondents who answered with ‘don’t know’. This number is arguably greater for poorly understood statements. Therefore, statement ignorance is the non-response in the sample, calculated for each statement.Footnote 5 Finally, as the policy statements come from different linguistic regions and parliaments, the models control for the language group (Flemish or Francophone) and the legislature (regional, national, or European). Especially this last covariate is important as both the regional and national elections can be considered first-order elections, but not European elections (Deschouwer 2012). Table 1 gives an overview of all of the variables.

Results

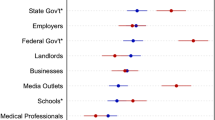

Before explaining inequality in opinion congruence, the data are explored by examining the degree to which parties and voters adopt left- and right-wing views in Fig. 3. Most parties are situated in the bottom left quadrant, indicating generally left-wing economic and cultural views, with a number of other parties found in the upper left quadrant (left-wing economic and right-wing cultural views), and in the upper right quadrant (right-wing economic and cultural views). Voters are situated in the top left quadrant, maintaining left-wing economic positions with right-wing positions. However, low-level SES voters are relatively more left-wing than high-level SES respondents on economic issues and vice versa on cultural issues. As such, the data provide some support for the assumptions outlined in the theoretical section.

Noticeable, however, is that most parties adopt left-wing or centrist attitudes on cultural issues, in contrast to the vast majority of voters. The sole exception is the RRP Vlaams Belang, which is by far the most right-wing party on cultural issues. Furthermore, Vlaams Belang combines these cultural views with a moderately left-wing perspective on economic positions. In sum, a visual inspection of the aggregate patterns in the data suggests support for hypothesis 1a, as left-wing parties appear to be relatively closer to the economic positions of underprivileged voters than they are to those of privileged voters. In addition, in line with hypothesis 2, the RRP Vlaams Belang is closer to low-level SES voters on both cultural and economic issues. In contrast, hypothesis 1b seems less supported, as most parties are closer to high-level SES voters on cultural issues.

Table 2 formally tests whether inequality in opinion congruence is dependent on party ideology and issue dimension. Model 1 includes only the covariates, while model 2 adds the main explanatory variables. Finally, model 3 adds the interaction terms between parties’ left–right position and issue dimension. Model 1 shows that opinion congruence inequality is not related to statement ignorance, the election level, and that there is no difference between Flemish and Francophone party positions. Model 2 indicates that opinion congruence inequality is generally higher on cultural issues than it is on economic issues. An average level of inequality of -0.54% on the latter dimension indicates a balance in the Belgian party system between left-wing and right-wing parties. On cultural issues, however, the views of privileged citizens are roughly 3% more congruent with parties than the views of the underprivileged are. As Fig. 3 already showed, there are more culturally left-wing parties than right-wing parties, resulting in a general overrepresentation of privileged voters on these issues.

In addition, though a positive effect of parties’ left–right positions on inequality in opinion congruence is found, this effect is not statistically significant. As expected, this is because the role of left–right views is contingent on the issue dimension. The coefficients in Model 2 show that the effect of parties’ left–right position is highly positive on economic issues (β = 1.19), but far less so on cultural and other issues. To get a better understanding of this interaction term, the marginal effects are plotted in Fig. 4. This figure shows the direct relation between parties’ left–right positions and opinion congruence inequality from Model 1 (solid line), and how this effect differs on economic (dashed line) and cultural issues (dotted line). On economic issues, the relation is steeper when compared the relation on all issues. This change is primarily the result of left-wing parties aligning far more with underprivileged voters. The difference between left- and right-wing parties seems to have reversed on cultural matters, though the slope of regression estimate is not statistically distinguishable from zero. On this dimension, both left- and right-wing parties generally side with the views of privileged voters. While hypothesis 1a thus finds clear support from the data, hypothesis 1b must be rejected. Parties are generally more tolerant on cultural issues than the public. As the higher educated and higher incomes are generally more left-wing on these issues than underprivileged voters are, inequality almost always favours privileged voters.

Inequality in opinion congruence, parties’ left–right position, by issue dimension. Note: Based on the results of Model 2 and 3, Table 2; the grey area represents the 95% confidence interval; when calculating the marginal effects, all other variables are kept at their mean value

The final hypothesis predicts that the RRP Vlaams Belang deviates from the patterns observed among the other parties by siding with underprivileged voters on both economic and cultural issues. Since VB is the only radical right party in the sample, this expectation is tested by regressing inequality in opinion congruence by a series of party dummies. The coefficients are reported in the Appendix, but the results are summarized in Fig. 5, which shows the level of inequality in opinion congruence by party and issue dimension. While the use of party dummies confirms the results of the previous analyses, it is clear that VB deviates from the patterns observed among other right-wing parties. Across all issue dimensions, affluent and higher educated voters are 3.4% less congruent with VB than underprivileged voters are. This gap is smaller and not statistically significant from zero on economic issues (− 1.7%), but substantially greater on cultural issues (− 5.4%). In fact, VB is the only party that sides with the underprivileged on cultural issues. In addition, these results are in agreement with Mudde’s (2007) claim that RRP are more centrist rather than left-wing on economic issues. Nevertheless, the results support hypothesis 2: VB is more congruent with underprivileged voters on the cultural dimension and clearly deviates from other right-wing parties on economic issues, though stopping short from being similar to left-wing parties on this dimension.

Conclusion

Previous studies that have looked at unequal preference representation have found that elite preferences and policy outcomes are often more in line with the views of higher educated and wealthier voters. Yet, such conclusions rarely take into account who controls the levers of power and the composition of legislatures. This paper examines the degree to which inequality in opinion congruence differs between left- and right-wing parties. Overall, while parties’ left–right ideology matters, this is conditional on the issue dimension. Inequality in opinion congruence on economic issues increases as a party become more right-wing. Cultural issues show a different pattern, with almost all parties siding with the policy preferences of the affluent and higher educated voters. As such, the findings agree with Bovens and Wille (2017) in that political elites, across parties, are more likely to have tolerant and permissive views on cultural matters. The sole exception is the RRP Vlaams Belang, which is the only party that better represents the views of underprivileged voters on cultural issues.

As such, the main conclusion of this paper is that not considering the role parties play in structuring inequality in opinion congruence and representation runs the risk of underestimating inequality, or missing instances of reversed inequality in favour of underprivileged voters. The inequality in opinion congruence found in so many studies (Gilens 2005; Giger et al. 2012; Schakel and Hakhverdian 2018) depends very much on the parties in power and on the nature of the policy issue.

Therefore, the approach suggested in this paper may offer a useful way to start thinking more systematically about opinion congruence inequality. The main drawback of this study is its limited scope. By focusing on only one country, there is inevitable doubt on whether these findings can be generalized, and a wider geographical scope would have made the results more robust. However, given that Belgium is a case where partisan convergence can be expected to be greater, and the role of parties in explaining opinion congruence inequality thus smaller, it is highly likely that a repetition of this study in other countries would too find that parties matter.

The findings presented here also have normative implications. On the one hand, finding that the unequal representation of underprivileged voters is not inevitable inspires optimism. Indeed, this paper convincingly shows that inequality in opinion congruence is not a constant, but a variable very much subject to the agency of the voting public. On the other hand, the less educated and lower-income voters clearly have fewer electoral options. In fact, in 2014 there existed no ‘perfect’ political party for the underprivileged; one that shares their views on both economic and cultural matters. Despite an institutional setting that encourages equal representation, and a fractionalized party landscape that increase choice, lower educated and lower-income voters are still stuck between a rock and a hard place. Whichever party they choose, they will find their policy desires frustrated on the economic or the cultural dimension, or on both.

Notes

While some have scholars have suggested that the difference between income and education matters (Werfhorst and Graaf 2004), robustness checks, voters were separated not on the basis of SES, but on the basis of education or income alone, confirm the results reported in the “Results” section. These robustness checks are reported in the Appendix.

The models with all statements, including those that have non-significant preference gaps, can be found in the Appendix.

The data utilized in this publication were made available by the CESPOL (UCLouvain), sponsored by the Belgian National Scientific Research Fund FNRS (CDR J.0141.14). The data were originally collected by Lieven De Winter, Audrey Vandeleene and Pierre Baudewyns. Neither the original collectors of the data nor the Centre bears any responsibility for the analysis or interpretations presented here.

All codings were done by the author. The statements were also coded by a second coder and adequate levels of reliability were achieved (Krippendorf’s Alpha = 0.83).

Statement ignorance was not found to differ between privileged and underprivileged respondents, with a correlation of r > 0.90.

References

Abou-Chadi, T., and M. Orlowski. 2016. Moderate as Necessary: The Role of Electoral Competitiveness and Party Size in Explaining Parties Policy Shifts. The Journal of Politics 78(3): 868–881.

Adams, J. 2001. Party Competition and Responsible Party Government: A Theory of Spatial Competition Based Upon Insights from Behavioral Voting Research. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Adams, J., and Z. Somer-Topcu. 2009. Moderate Now, Win Votes Later: The Electoral Consequences of Parties’ Policy Shifts in 25 Postwar Democracies. The Journal of Politics 71(2): 678–692.

Andeweg, R., and J. Thomassen. 2011. Pathways to Party Unity: Sanctions, Loyalty, Homogeneity and Division of Labour in the Dutch Parliament. Party Politics 17(5): 655–672.

Bobbio, N. 1996. Left and Right: the Significance of a Political Distinction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bourdieu, P. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, ed. J.G. Richardson, 241–258. Greenwood: Westport, CT.

Bovens, M., and A. Wille. 2017. Diploma Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bronars, S.G., and J.R. Lott. 1997. Do Campaign Donations Alter How A Politician Votes? Or, Do Donors Support Candidates Who Value The Same Things That They Do? Journal of Law and Economics 2(40): 317–350.

Carnes, N. 2012. Does the Numerical Underrepresentation of the Working Class in Congress Matter? Legislative Studies Quarterly 37(1): 5–34.

Converse, P.E. 2006. The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics (1964). Critical Review 18(1–3): 1–74.

Dalton, R.J. 2017. Party Representation Across Multiple Issue Dimensions. Party Politics 23(6): 609–622.

de Werfhorst, H.G.V., and N.D. de Graaf. 2004. The Sources of Political Orientations in Post-industrial Society: Social Class and Education Revisited. The British Journal of Sociology 55(2): 211–235.

De Winter, L. and Johan Ackaert (1994) ‘Abstentionnisme electoral et vote blanc ou nul: Le “non-vote” en Wallonie.’, In Enquete sur le comportement electoral des Wallons et des Francophones. ed. A.P. Frognier and A.M. Aish-Van Vaerenbergh. Brussel: De Boeck, pp. 77–98

De Winter, L., M. Swyngedouw, and P. Dumont. 2006. Party System(s) and Electoral Behaviour in Belgium: From Stability to Balkanisation. West European Politics 29(5): 933–956.

Depauw, S. 2003. Government Party Discipline in Parliamentary Democracies: The Cases of Belgium, France and the United Kingdom in the 1990s. The Journal of Legislative Studies 9(4): 130–146.

Deschouwer, K. 2009. The Politics of Belgium: Governing a Divided Society. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Deschouwer, K. 2012. The Politics of Belgium: Governing a Divided Society. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Diamond, L.J., and L. Morlino. 2005. Assessing the Quality of Democracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Downs, A. 1957. An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy. Journal of Political Economy 65(2): 135–150.

Duverger, M. 1972. Political Parties, Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State. London: Methuen.

Evans, G., and J. Tilley. 2012. How Parties Shape Class Politics: Explaining the Decline of the Class Basis of Party Support. British Journal of Political Science 42(1): 137–161.

Flavin, P. 2012. Income Inequality and Policy Representation in the American States. American Politics Research 40(1): 29–59.

Freire, A., and A. Belchior. 2013. Ideological Representation in Portugal: MPs’–Electors’ Linkages in Terms of Left-Right Placement and Substantive Meaning. The Journal of Legislative Studies 19(1): 1–21.

Fukuyama, F. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press.

Galesic, M., and M. Bosnjak. 2009. Effects of Questionnaire Length on Participation and Indicators of Response Quality in a Web Survey. Public Opinion Quarterly 73(2): 349–360.

Gallego, A. 2010. Understanding Unequal Turnout: Education and Voting in Comparative Perspective. Electoral Studies 29(2): 239–248.

Giger, N., J. Rosset, and J. Bernauer. 2012. The Poor Political Representation of the Poor in a Comparative Perspective. Representation 48(1): 47–61.

Gilens, M. 2005. Inequality and Democratic Responsiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly 69(5): 778–796.

Hillen, S., and N.D. Steiner. 2020. The Consequences of Supply Gaps in Two-Dimensional Policy Spaces for Voter Turnout and Political Support: The Case of Economically Left-Wing and Culturally Right-Wing Citizens in Western Europe. European Journal of Political Research 59(2): 331–353.

Key, V.O. 1961. Public Opinion and American Democracy. New York: Knopf.

Kitschelt, H., and A.J. McGann. 1997. The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Kriesi, H., et al. 2006. Globalization and the Transformation of the National Political Space: Six European Countries Compared. European Journal of Political Research 45(6): 921–956.

Kriesi, H., E. Grande, M. Dolezal, M. Helbling, D. Höglinger, S. Hutter, and B. Wüest. 2012. Political Conflict in Western Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lau, R.R., et al. 2014. Correct Voting Across Thirty-Three Democracies: A Preliminary Analysis. British Journal of Political Science 44(02): 239–259.

Lefkofridi, Z. and Michel, E. (2014) Exclusive Solidarity? Radical Right Parties and the Welfare State. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Paper No. 2014/120. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2539503.

Lefkofridi, Z., M. Wagner, and J.E. Willmann. 2014. Left-Authoritarians and Policy Representation in Western Europe: Electoral Choice across Ideological Dimensions. West European Politics 37(1): 65–90.

Lesschaeve, C. 2017. Inequality in Party-voter Opinion Congruence: A Matter of Choices Made or Choices Given? Representation 53(2): 153–166.

Lijphart, A. 2012. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mair, P. 1997. Party System Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mudde, C. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Page, B.I., and R.Y. Shapiro. 1992. The Rational Public: Fifty Years of Trends in Americans’ Policy Preferences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pauwels, T. 2011. Measuring Populism: A Quantitative Text Analysis of Party Literature in Belgium. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 21(1): 97–119.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., and A. Skrondal. 2012. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata. 3rd ed. College Station, Tex: Stata Press Publication.

Rabinowitz, G., and S.E. Macdonald. 1989. A Directional Theory of Issue Voting. The American Political Science Review 83(1): 93–121.

Rosset, J. and Kurella, A.-S. (2020) ‘Elections as a Source of Political Inequality. Party Supply and Spatial Voting in Europe’. Available at: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:134625 (Accessed: 30 September 2020).

Rovny, J., and E.E. Edwards. 2012. Struggle over Dimensionality: Party Competition in Western and Eastern Europe. East European Politics and Societies: and Cultures 26(1): 56–74.

Saalfeld, T., and D. Bischof. 2013. Minority-Ethnic MPs and the Substantive Representation of Minority Interests in the House of Commons, 2005–2011. Parliamentary Affairs 66(2): 305–328.

Schakel, W., and A. Hakhverdian. 2018. Ideological Congruence and Socio-economic Inequality. European Political Science Review 10(3): 441–465.

Schumacher, G., and K. van Kersbergen. 2016. Do Mainstream Parties Adapt to the Welfare Chauvinism of Populist Parties? Party Politics 22(3): 300–312.

Schwander, H., D. Gohla, and A. Schäfer. 2020. Fighting Fire with Fire? Inequality, Populism and Voter Turnout. Politische Vierteljahresschrift 61(2): 261–283.

Soroka, S.N., and C. Wlezien. 2008. On the Limits to Inequality in Representation. PS: Political Science & Politics 41(2): 319–327.

Steinbrecher, M. and Seeber, G. (2011) Inequality and Turnout in Europe. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1901620. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1901620 (Accessed: 12 February 2013).

Stubager, R. 2008. Education Effects on Authoritarian–Libertarian Values: A Question of Socialization 1. The British Journal of Sociology 59(2): 327–350.

Thomas, J.C. 1980. Policy Convergence among Political Parties and Societies in Developed Nations: A Synthesis and Partial Testing of Two Theories. The Western Political Quarterly 33(2): 233.

Van Der Brug, W., and J. Van Spanje. 2009. Immigration, Europe and the “new” Cultural Dimension. European Journal of Political Research 48(3): 309–334.

van Gerven, M., and M. Beckers. 2009. Unemployment protection reform in Belgium, Finland, the Netherlands and the UK: Policy learning through open coordination? In Changing European Employment and Welfare Regimes: The Influence of the Open Method of Coordination on National Reforms, ed. M. Heidenreich and J. Zeitlin, 61–83. New York: Routledge.

Walgrave, S., and J. Lefevere. 2013. Ideology, Salience, and Complexity: Determinants of Policy Issue Incongruence between Voters and Parties. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 23(4): 456–483.

Weekers, K., B. Maddens, and J. Noppe. 2009. Explaining the Evolution of the Party Finance Regime in Belgium. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 19(1): 25–48.

Winters, J.A., and B.I. Page. 2009. Oligarchy in the United States? Perspectives on Politics 7(4): 731–751.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lesschaeve, C. Bringing representatives back in: How political parties moderate patterns of inequality in opinion representation. Eur Polit Sci 21, 255–273 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00332-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00332-y