Abstract

This Note introduces the Heads of Government dataset, which provides summary information about the ideological orientation of heads of government (left, center, or right, with separately provided information about religious orientation) in 33 states in Western Europe, the Americas, and the Asia–Pacific region between 1870 and 2012. The Note also describes some intriguing empirical patterns when it comes to over-time changes in the political prominence of left-wing, centrist, and right-wing parties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the last few years, scholars of comparative politics have taken a greater interest in political developments between the late nineteenth century and the Second World War. Ten or twenty years ago, such long-term historical analyses were rare, with most cross-country studies in comparative politics starting after the Second World War, or even later. As a result of this emphasis on the post-war period in the existing literature, we have long lacked systematic data on the ideological orientation of governments before 1945. We have developed a new measure of government ideology that is based on the ideological orientation of heads of government.

In this note, we introduce the Heads of Government dataset (HoG), which provides summary information about the ideological orientation of heads of government in 33 states in Western Europe, Latin America, North America, and the Asia–Pacific region between 1870 and 2012, including periods in which these countries were governed by authoritarian, as opposed to democratic, governments. We also present some empirical patterns that are revealed by the new dataset. We show, for instance, that the first left-wing heads of government were appointed approximately one decade into the twentieth century, that the political right was historically weak around the time of the Second World War, but recovered soon thereafter, and that there are intriguing fluctuations in the balance of power between left and right over time.

Contributions

Data on the ideological orientation of chief executives in all countries in the world since 1975 are available from the World Bank’s Database of Political Institutions (Beck et al, 2001; Keefer, 2012), which introduced a categorization of left–right ideology and religious orientation that the Heads of Government dataset builds on. Information about the ideological orientation of parties in the advanced industrialized states in Western Europe, North America, and the Asia–Pacific region in the post-war period is provided by, among others, Armingeon et al (2012); Döring and Manow (2010); Swank (2010), which relies, in turn, on the expert codings by Castles and Mair (1984); and Woldendorp et al (2011). Information about the ideological orientation of parties in Latin America during much of the twentieth century is provided by Coppedge (1997) (additional information can be found in Murillo et al, 2010).

Neither of these datasets has the geographical and temporal scope that the Heads of Government dataset has. The Heads of Government dataset covers the period from 1870 to 2010 and includes 33 countries: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, Ecuador, Finland, France, Germany (West Germany between 1949 and 1990), Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Paraguay, Peru, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, Uruguay, and Venezuela. In other words, the dataset includes all South American, North American, and Western European countries with a current population of more than one million, plus Australia, Costa Rica, Japan, Mexico, and New Zealand. Some of these countries were not independent during the entire period between 1870 and 2012. No ideology coding is provided for years in which a country is not coded as independent in the Boix et al (2013) dataset on political regimes.1

The reasons that we have chosen to concentrate on these 33 countries are that all of them have historically experienced periods of democratic government, even if democracy has sometimes been interrupted by dictatorships, as in most of the Latin American cases; that the economic left–right dimension has been salient in all of them (which is not the case in most other parts of the world); and that most of them are important country cases in the comparative politics literatures on the advanced industrialized countries (North America, Western Europe, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand) and Latin America. For all three reasons, the data that we provide are likely to be useful for future scholarship.

The main conceptual difference between the Heads of Government dataset and the post-war datasets that have been developed in the past four decades is that the Heads of Government dataset concentrates on heads of government. Most other datasets, by contrast, provide information about the distribution of legislative seats or cabinet seats among several political parties. Our justification for concentrating on heads of government is entirely practical: extending existing post-1945 datasets to the 75-year period between 1870 and 1944 would be a much more demanding task than the task that we have undertaken, since it would require an ideological classification of all parties in each national the party system – not only the smaller set of parties that were significant enough for their leaders to compete for the office of head of government.

Categorizing the ideological orientations of political leaders

Our coding of head of government ideology has two dimensions: a largely economic, ideological dimension (distinguishing between ‘left,’ ‘center,’ and ‘right’) and a religious dimension (distinguishing between heads of government with an explicitly Christian platform and those without an explicitly Christian platform). In some of the countries in our sample, additional conflicts, such as conflicts over language, have also structured political competition, but all countries in our sample have, at one time or another, experienced conflicts over class and religion, which is why we concentrate on those two dimensions.

The main methodological challenge for a study that attempts to capture ideological differences and similarities among leading politicians in more than 30 countries over a period of 140 years is consistency: to develop measures of ideology that can be applied systematically to all country-years in the sample. Given the size of this challenge, we make no attempt to place leaders along a continuous left–right scale. Instead, we separate heads of government into three broad ideological categories – left, center, and right – which correspond to three sets of party families: ‘left’ denotes communist, socialist and social democratic parties and factions, ‘center’ denotes agrarian and social liberal parties and factions as well as some post-war Christian democratic parties, and ‘right’ denotes conservative and market-liberal parties and factions, as well as most of the pre-war Catholic parties and the remaining Christian democratic parties (fascist heads of government are also coded as right wing).

Mair and Mudde recommend two different approaches to the study of party families, one based on the origin of parties and one based on their ideology, and they make the observation that these strategies should be pursued in ‘parallel’ since one is more appropriate for historical studies and one is more useful for cross-country comparative studies (1998, 225). Since our dataset is both historical and comparative, we have opted for a combination of the two approaches: We have grouped parties on the basis of their shared origins (socialist, liberal, conservative, Christian, etc.), and then we have made a further grouping of the different families into three ideological categories (left, center, right).

We proceeded in the following manner.

-

1.

We used the rulers.org dataset (Schemmel, 2013) to produce a complete list of heads of government – prime ministers, presidents, chancellors – for each country in the dataset.

-

2.

We then used a number of different sources, including, in particular, Nohlen and Stöver (2010), Nohlen et al (2002), Nohlen (2005a, b), Von Beyme (1970), the Encyclopedia Britannica (2013), and, in a few cases, Wikipedia, to identify the name of the party that the head of government belonged to (or, alternatively, his or her parliamentary faction or ideological tendency).

-

3.

In countries where it was possible to do so, we used sources such as Caramani (2000, 2004), Szajkowski (2005) and country-specific sources to determine which broad families of parties have existed in each country, and which parties have historically belonged to those families.

-

4.

We then used a number of different sources to categorize party families and parties into the three categories left, center, and right and to determine if heads of government, or their parties, had an explicitly Christian platform. When it comes to the history and ideological placement of parties, we learned a great deal from the excellent surveys of party position measures that are provided in Rehm (2006) and Di Tella (2004).

-

5.

Finally, we relied on historical reference works and, in some cases, the biographies of heads of government when determining if the ideological orientations of individual heads of government deviated from the ideology of their parties or factions. We used similar sources to determine the ideologies of heads of government that did not belong to any particular party.

-

6.

Once we had a preliminary coding for each country, we sent out the spreadsheets with the years, names, party names, and preliminary ideological categorizations to country experts. Based on the expert responses, often following further inquiries and the consultation of additional country-specific sources, we decided on a final ideological coding.

Our starting point when we coded leader ideologies and religious platforms were two variables in the World Bank’s Database of Political Institutions (Beck et al, 2001; Keefer, 2012). For reasons of temporal and spatial consistency, to correct errors, to more closely follow established comparative projects measuring ideological placement of political parties, and following the advice of our country experts, however, approximately 15 percent of our ideological codings (and 5 percent of our religious codings) for the period from 1975 onward differ from the codings in the World Bank’s dataset.

Specific problems

One of the most difficult problems that we confronted was how to code Christian democratic parties in the economic dimension. It is still debated among scholars whether Christian democratic parties should be thought of as similar to conservative parties such as the British Conservative Party or as parties with a largely centrist ideology; it is also debated whether Catholic and Christian-Social parties before the Second World War were different from post-war Christian democratic parties or not (on both of these issues, see especially the recent review article by Kalyvas and van Kersbergen, 2010). We ended up coding most post-war Christian democratic parties in countries with a large party to the right of the Christian democrats (such as Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, and Norway) as centrists; most other Catholic and Christian democratic parties are coded as being on the right. We believe that this categorization makes sense for many different empirical applications. In cases where it would be better to code these parties differently, it is simple and straightforward to use the separate ideological measure of religion that the Heads of Government dataset provides – which identifies leaders with an explicitly Christian platform – to recode the left–center–right measure for this particular group of parties.

Another difficult problem concerns dictatorships. The dataset includes information about the ideology of head of governments from both democracies and dictatorships over almost one and a half century. Accordingly, the dataset includes right-wing authoritarian leaders such as Otto von Bismarck, Benito Mussolini, and Alberto Fujimori as well as left-wing dictators such as Juan Perón. The ideological positions of these heads of government should be seen in relation to the type of regime they governed, as well as other elements of the cultural and historical context. Scholars using the data are well advised to make use of information about regime type, and other contextual information, to allow for meaningful comparisons across countries.

A third problem that we would like to bring attention to is populism. During the twentieth century, several countries in Latin America were governed, from time to time, by populist leaders whose approaches to politics were in some ways similar, but whose ideological convictions are at times difficult to place in the traditional left–right spectrum. Populist leaders distinguished themselves by embracing the poor and lower classes as their power base and by promising to break oligarchic power structures; but they often combined these demands with strong nationalist overtones. Each populist leader was therefore analyzed individually (to avoid making strong assumptions about populist leaders as a general phenomenon). As an empirical matter, however, most of Latin America’s populists have been coded as left wing due to their redistributive platforms.

Validation using other ideology measures

This section compares our coding of the ideological orientation of heads of government with two existing measures of the ideology of heads of governments and one measure of the ideological orientation of cabinets.

-

1.

The World Bank’s Database on Political Institutions (Keefer, 2012) codes the ideology of heads of governments from 1975 onward for a worldwide sample. Although we started from the World Bank’s categories and categorizations when we developed our own measure for the post-1975 time period, the two measures are not identical.

-

2.

In their book Taxing the Rich, Scheve and Stasavage (2016) provide information about left-wing heads of government for 20 developed countries (19 of which are in our dataset) between 1800 and 2013. To facilitate a direct comparison, we collapse our ‘center’ and ‘right’ ideology categories into a single non-left category.

-

3.

The Comparative Political Parties Dataset by Swank (2010) provides information about the share of cabinet seats for left, center, and right parties in 21 countries (all in our sample) between 1950 and 2011. Although Swank’s measure is not strictly comparable with ours, this validation exercise is useful since our coding, like Swank’s, is based on a categorization of the ideologies of government parties.

In Figures 1, 2, and 3, we provide cross-tabulations of our own Heads of Governments coding (in the rows) and each of these alternative ideology measures (in the columns).

For the World Bank’s Database of Political Institutions (DPI) (Figure 1), we find a Goodman–Kruskal lambda of 0.66. The cross-tabulation shows that most of the cases in the left, right, and other categories are in agreement with the World Bank DPI coding. In the center category, however, we find that 52 percent of the heads of government we characterize as centrist fall in either the left or right categories in the DPI. The main reason is that we have categorized several Christian democratic parties as centrist.

We find that Scheve’s and Stasavage’s coding of left and non-left heads of government is in close agreement with our own measure (Figure 2), which is not surprising, since we found the ‘left’ category relatively easy to delineate from other categories. To allow comparison, we combine our center and right ideology categories into a non-left category. The observation that the ideological placement is consistent with Scheve and Stasavage’s ideology measure across a time period starting in 1870 is reassuring. A high Goodman–Kruskal lambda of 0.77 further confirms the strong coding agreement.

Finally, we compare our Heads of Government ideological coding to Swank’s ideological coding of government cabinets (2010) (see Figure 3). To make the two datasets comparable, we use Swank’s data on the political placement of the majority of the cabinet on the left–center–right scale. Despite the conceptual differences between the datasets, we find a fairly close agreement when it comes to the left and right categories, although there is more disagreement when it comes to the center category; the Goodman–Kruskal lambda of 0.52 indicates moderately strong agreement.

Empirical patterns

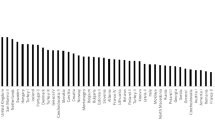

We will now comment on a few patterns that the Heads of Government dataset helps us to see. Figure 4 describes the distribution of ideological orientations among heads of government in all the countries in our dataset between 1870 and 2012. Figure 5 describes the distribution of ideological orientations among the heads of government of democracies in the same time period (overall, our data provide data on 1459 heads of government, about 60 percent of whom were elected or appointed in democracies). As before, we rely on the categorization of political regimes introduced by Boix et al (2013).

One pattern that stands out in both figures is that whereas centrist parties have been ‘squeezed’ since the inter-war period, parties on the right have managed to remain relevant as a political alternative throughout the period covered by the Heads of Government dataset. As shown in Figure 4, which includes non-democratic as well as democratic regimes, right-wing leaders have controlled the government approximately 45 percent of the time since the beginning of the twentieth century. As shown in Figure 5, parties on the right have been less dominant in democracies than in autocracies, but not much so; since the 1950s, right-wing parties have often controlled more than 40 percent of all governments. (On the left the pattern has been more clear-cut: While one quarter of the democratic leaders in our sample are coded as left, only 8 percent of the autocratic heads of government have a left-wing ideology.)

The figures show, as one would expect, that the main conflict in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries involved parties that we categorize as centrist (especially liberal parties) and parties that we categorize as right wing (mainly conservative and Catholic parties). The first left-wing heads of government were appointed just before the First World War (following the mobilization of the working class in many countries at that time). The main period of expansion for the left in the countries in our sample – in terms of rising to the pinnacle of political power – was the fifteen-year period between the middle of the 1930s (the aftermath of the Great Depression) and the early 1950s.

Interestingly, the left was historically weak (in terms of running governments) in the period that is often thought of as the ‘Golden Age’ of social democracy: the 1950s and 1960s. The recovery of the political right and the weakness of the left in democracies in that period (after the powerful swing to the left in the wake of the Second World War) stand out as an important event in the history of competitive politics in the parts of the world that are covered by the Heads of Government dataset – in democracies, as Figure 5 reveals, right-wing parties became consistently weaker between the 1870s and the 1940s; in the 1950s, they turned the tide.

Another observation that can be made on the basis of Figure 5 is that in addition to the long-term ideological ‘waves’ that we have just discussed, the ideological orientation of chief executives seems to fluctuate over time, possibly as a result of coordinated business cycles, possibly as a result of other forces that are not well understood.

Conclusion

The Heads of Government dataset includes information about the ideological orientation of governments in many countries over a long period of time. Inevitably, therefore, the data contain two types of errors. First, it is difficult to achieve consistency when trying to describe ideological orientations in very different economic, social, and political contexts. Second, any measurement of a latent concept such as political ideology at times requires judgment calls, and although we have sought to cross-check our coding decisions with country experts, it is likely that reasonable people disagree on some of the judgments that we have made. We welcome input from all those who detect errors in the data, or who have other reasons to believe that our coding decisions should be altered; we will publish revised versions of the dataset in the future.

Notes

-

1

In other words, we include all country-years for which the democracy_omitteddata variable in the Boix, Miller, and Rosato dataset takes non-missing values.

-

2

In many cases, Archigos provides information about the monarch rather than the prime minister in constitutional monarchies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; Archigos also provides information about the president rather than the prime minister in semi-presidential regimes such as France. We code the prime minister in both types of regimes, since the prime minister is more directly responsible for the development of domestic policy, as opposed to foreign policy.

-

3

In our dataset, in 4 percent of all country-years (185 observations) the leadership ideology variable is coded as ‘Other.’ Of these observations, 75 percent are in Latin America and most (80 percent) occur in non-democratic regimes. In particular, in cases in which military juntas control the government, it is difficult to distinguish a clear ideology of the strongman or president in power. Rather than inferring the regime type from the institution (the army), we coded these cases conservatively and did not assign an ideology category.

References

Armingeon, K., Weisstanner, D., Engler, S. Potolidis, P. and Gerber, M. (2012) ‘Comparative political data set I, 1960–2010’. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne. URL: http://www.cpds-data.org/.

Beck, T., Clarke, G., Groff, A., Keefer, P. and Walsh, P. (2001) ‘New tools in comparative political economy: the database of political institutions’, World Bank Economic Review 15(1):165–176.

Boix, C., Miller, M.K. and Rosato, S. (2013) ‘A complete data set of political regimes, 1800–2007’, Comparative Political Studies 46(12):1523–54.

Caramani, D. (2000) Elections in Western Europe 1815–1996. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Caramani, D. (2004) The Nationalization of Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Castles, F.G. and Mair, P. (1984) ‘Left–right political scales: some ‘expert’ judgments’, European Journal of Political Research 12(1):73–88.

Coppedge, M. (1997) A Classification of Latin American Political Parties. Notre Dame: Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies.

Di Tella, T.S. (2004) History of Political Parties in Twentieth Century Latin America. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers.

Döring, H. and Manow, P. (2010) ‘Parliament and government composition database (ParlGov): Information on parties, elections and cabinets in modern democracies.’ URL: http://www.parlgov.org/.

Encyclopedia Britannica. (2013) Various entries. URL www.britannica.com/.

Goemans, H.E., Gleditsch, K.S. and Chiozza. G. (2009) ‘Introducing archigos: a dataset of political leaders’, Journal of Peace Research 46(2):269–283.

Kalyvas, S.N. and van Kersbergen, K. (2010) ‘Christian democracy’, Annual Review of Political Science 13: 183–209.

Keefer, P. (2012) DPI2000 Database of Political Institutions: Changes and Variable Definitions. Washington, DC: The World Bank, Development Research Group.

Mair, P. and Mudde, C. (1998) ‘The party family and its study’, Annual Review of Political Science 1: 211–229.

Murillo, M.V., Oliveros, V. and Vaishnov, M. (2010) Dataset on Political Ideology of Presidents and Parties in Latin America. New York: Columbia University.

Nohlen, D. (2005a) Elections in the Americas: A Data Handbook, Volume 1 (North America, Central America, and the Caribbean). New York: Oxford University Press.

Nohlen, D. editor. (2005b) Elections in the Americas: A Data Handbook: Volume 2: South America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nohlen, D. and Stöver, P. editors. (2010) Elections in Europe: A Data Handbook. Baden-Baden: Nomos Publishers.

Nohlen, D., Grotz, F. and Hartmann, C. editors. (2002) Elections in Asia and the Pacific: A Data Handbook: Volume 1: Middle East, Central Asia, and South Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rehm, P. (2006) Measuring parties’ positions in the policy space. A critical survey with some suggestions. Columbus: Ohio State University. (unpublished manuscript).

Schemmel, B. (2013) ‘Rulers database’. URL http://www.rulers.org.

Swank, D. (2010) Electoral, Legislative, and Government Strength of Political Parties by Ideological Group in Capitalist Democracies, 1950–2006: A Database. Milwaukee: Marquette University.

Scheve, K. and Stasavage, D. (2016) Taxing the Rich: A History of Fiscal Fairness in the United States and Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Szajkowski, B. (2005) Political Parties of the World. London: John Harper Publishing.

Teorell, J. Samanni, M., Holmberg, S. and Rothstein B. (2012) The Quality of Government Dataset, Version 6 April 2011. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, The Quality of Government Institute.

Von Beyme, K. (1970) Die Parlamentarischen Regierungssysteme in Europa. Munich: R. Piper & Co. Verlag.

Woldendorp, J., Keman, H. and Budge, I. (2011) ‘Party government in 40 democracies 1945–2008. Composition–duration–personnel’. Amsterdam: Department of Political Science and Public Administration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Variables in the dataset

Appendix: Variables in the dataset

In this appendix, we define all the variables that are included in the Heads of Government dataset. We provide two versions. The main dataset is in the country-year format and concentrates on the head of government that was in office during the greater part of the year. We also provide a dataset in the leader-year format (similar to that of the Archigos dataset of political leaders, Goemans et al, 2009), but we do not provide data on the ideology of leaders who were only in power for a few months.2

cname. The name of the country, using naming conventions derived from the QOG dataset (Teorell et al, 2012).

ccode. A three-digit numeric country code based on the ISO 3166-1 standard system.

ccodecow. A numeric country code based the classification by the Correlates of War project.

ccodeiso. A three-letter country code based on the ISO 3166 alpha-3 system.

year. The year.

hogname. The name of the head of government (president, prime minister, chancellor, etc.).

hogid. A unique identifier code for individual head of governments, consisting of the three-letter country code and the last name of the head of government (and, in the event that several heads of government from one country had the same last name, a counter).

archigos leadid. The leader identification code used by the Archigos database (Goemans et al, 2009) (included to simplify the combination of information from the two databases).

hogideo. The ideological orientation of the head of government. The variable takes five values: R(ight), L(eft), C(enter), O(ther), or NA. We use the ‘Other’ category if the head of government’s ideological position does not fit into either of the three main ideologies or if we have insufficient information (for example, if there are competing wings within the head of government’s party and his or her own ideological position cannot be determined).3 We use the code ‘NA’ if there is no head of government.

hogrel. This variable takes the value 1 for heads of government with explicitly Christian platforms, 0 for all others. Whether the state is secular and whether the leader him or herself is Christian does not in itself determine the coding. Empirically, most of the Christian heads of governments that we identify belong to Catholic or other Christian parties before the Second World War or to Christian democratic parties after the Second World War.

hogindate. The date the head of government took office. Most of these data, but not all, are derived from Goemans et al (2009).

hogoutdate. The date the head of government left office. Most of these data, but not all, are derived from Goemans et al (2009).

hogtenure. The overall length of tenure of the head of government in office in days.

hogtenureyear. The total number of days in office during the calendar year.

hogcandnr. The order of heads of government within a country-year with respect to the number of days in office (hogcandnr = 1 thus identifies the head of government with the longest time in office during the calendar year).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brambor, T., Lindvall, J. the ideology of heads of government, 1870–2012. Eur Polit Sci 17, 211–222 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0124-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0124-9