Abstract

This study uses the 2013–2017 American Community Survey to explore differences in the returns to obtaining US citizenship for immigrants from the four largest source countries relative to all other immigrants. We find that Chinese, Mexican, and Filipino immigrants face a wage penalty prior to naturalization, while Indian immigrants experience higher wages than other immigrants. Naturalization more than offsets the wage penalty for Chinese and Filipino immigrants and partially offsets the wage penalty for Mexican immigrants. However, naturalized Indian immigrants earn less than non-naturalized Indian immigrants. We find only limited evidence of a naturalization premium for immigrants from other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research into the returns to citizenship has largely found a significant economic benefit to immigrants choosing to naturalize. In general, naturalized immigrants tend to have lower rates of unemployment, higher earnings, and wage growth, and tend to be employed in occupations with more desirable job characteristics compared to non-naturalized immigrants (Bratsberg et al. 2002; Steinhardt 2012; Gathmann and Keller 2013; Helgertz et al. 2014; Euwals et al. 2010). While some studies have examined how these labor market outcomes differ across countries and regions of origin, these differences are mostly explained by differences in initial human capital and the ease of assimilation. While these differences are indeed important, there is another source of variation that has been largely ignored in the literature: differences in the ability to naturalize. Empirical studies examining naturalization in the USA (e.g., Bratsberg et al. 2002; Akbari 2008) implicitly assume that the naturalization process is the same for all immigrants, regardless of country of origin. However, this is not the case.

According to US Citizen and Immigration Services, in order to qualify for naturalization, an applicant must have been a lawful permanent resident (a.k.a. a “green card” holder) for at least 5 years, or 3 years if married to a US citizen. After this time, green card holders are eligible to apply for citizenship (USCIS 2016a). However, not all immigrants to the USA have the same access to green cards. With the exception of immediate family members of US citizens, annual green card allocation is restricted by quotas pertaining to immigrant category and country of origin. In particular, the Department of State issues a maximum of 226,000 family-preference sponsored visas and 140,000 employment-based visas per year. These two broad categories are further subdivided into subcategories, with each receiving a percentage of the total visa allocation (USCIS 2016b). Furthermore, no more than 7% of the total available visas may be issued to natives of any one independent country (USCIS 2016c). In practice, this means that a maximum of approximately 25,000 green cards can be issued to applicants from any single source country, while the rest of the applicants are placed on a waiting list. In fiscal year 2017, Mexico has 1.3 million applicants on the waiting list. China, India, and the Philippines each have over 250,000 applicants on the waiting list (US Department of State 2016).

Given the backlog, applicants from the largest immigrant source countries might wait several years to obtain lawful permanent residence, making the time to naturalization much longer for some groups than others. This can substantially increase the costs of obtaining citizenship, thus altering the composition of the naturalized immigrant population. Furthermore, since there are additional quantitative limits on classes of visas, wait times can vary widely even for applicants from the same country. For example, while there is no waitlist for workers with advanced degrees from Mexico and the Philippines, the wait time to get a green card for brothers and sisters of adult US citizens can be longer than 20 years. China and India have shorter wait time for family-based green cards than Mexico and the Philippines, but longer wait time for employment-based green cards. This is especially the case for India, with more than 10 years of wait time in the EB2 and EB3 categories as of July 2019 (US Department of State 2019). These excessively long wait times could hinder wage growth as immigrants are excluded for certain sectors of the labor force, of excluded all together if they have to remain in their home country while they wait for a green card.

If the returns to naturalization vary across different countries of origin, then this quota system is a potential source of unrealized gains within the economy. This study represents a step toward understanding how the visa quota system affects immigrants from oversubscribed countries. In particular, we examine differences in earnings between naturalized and non-naturalized immigrants, paying particular attention to immigrants from the four largest source countries for immigrants to the USA: China, India, Mexico, and the Philippines. We compare this naturalization premium to immigrants from the rest of the world to determine whether naturalized immigrants from oversubscribed countries benefit more or less than immigrants from other countries. We find that the premiums are larger than average for Chinese, Mexican, and Filipino immigrants, but smaller than average for Indian immigrants. Furthermore, we find that Chinese, Mexican, and Filipino immigrants face a wage penalty compared to other migrants. We find that naturalization more than offsets this penalty for Chinese immigrants, but only partially offsets the penalty for Mexican and Filipino immigrants. Finally, we find no evidence of a naturalization premium for immigrants from the rest of the world.

Economic Assimilation and the Naturalization Premium

A wide body of the literature has examined how immigrants fare in the labor market. Much of this literature focuses on immigrants’ labor market performance relative to natives, and the role that assimilation and citizenship play in labor market outcomes. Chiswick (1978) was one of the first to investigate the effect of citizenship on earnings. While he initially found evidence that naturalized immigrants earn more than non-naturalized immigrants, after controlling for years since migration, this effect disappeared. Hence, he concluded that naturalized immigrants earn more due to more experience in the USA, rather than naturalization itself. The general explanation of this finding is that new immigrants lack the necessary information and skills necessary for labor market success when they first arrive. However, over time they assimilate to local labor market conditions, and their wages catch up to natives’ wages. Further, if immigrants are positively selected, eventually their wages will surpass those earned by natives. The findings of this seminal study, that naturalization was insignificant and immigrants’ earnings catch up over time, coupled with a dramatic shift in immigrant demographics that was occurring at the time led the research narrative over the next few decades to focus attention away from the effects of naturalization and toward identifying more precise estimates of the rate of wage growth for various immigrant cohorts and regions of origin.

Perhaps the most important point of contention with Chiswick’s (1978) findings was that the data were restricted to white males observed in the 1970 Census. Given that in the 1950s, “approximately two-thirds of all immigrants arrived from Europe, Canada, or Australia” (LaLonde and Topel 1992), this may have been an appropriate group to study at the time. However, reforms to immigration law in 1965 meant that the typical immigrant in the future may not be well represented by the white male who arrived in the previous 50 years. Prior to the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, the USA utilized a country-of-origin quota system that allowed entry based on 1890 population ratios. This system largely favored immigrants from Western Europe, while excluding immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, as well as other parts of the world, particularly Asia and Latin America. The removal of the quota system in 1965 dramatically changed the demographic profile of immigrant flows into the USA. Between the 1970 and 1980 Census, recent arrivals from Europe fell from 30% of the new immigrant population to 14%, while recent arrivals from Asia, and Central and South America rose from 39% to 67% (Pew Research Center 2015, p. 35). In the 50 years since 1965, only 12% of immigrants come from Europe, while 51% come from Latin America and 25% come from South/East Asia (Pew Research Center 2015, p. 19). Furthermore, the new law put an emphasis on family-based preferences in immigration over employment-based preferences.

These changes in cohort demographics combined with the cross-sectional nature of the data led future research largely to ignore the effects of naturalization and focus mostly on whether the observed effects on immigrant wage growth were due to assimilation effects or changes in cohort quality. That is, if immigrants entering the country in 1970 are more likely to come from countries with lower levels of human capital than immigrants who arrived in 1950, it follows that these later immigrants would have less human capital and therefore not perform as well in the labor market. Thus, the observed differences between recent arrivals and previous arrivals are not due to the previous arrivals having been in the country longer, but that they came with more human capital to start with. Thus, research on immigrant performance over the decades to follow was largely focused on identifying the accurate rate of wage growth for various immigrant groups, according to arrival cohorts and places of origin (e.g., Borjas 1985, 1995; Chiswick 1986; Duleep and Regets 1997; LaLonde and Topel 1992).

It was not until the turn of the century that economists began looking again at the labor market benefits of naturalization. Bratsberg et al. (2002) revisited the question of returns to naturalization, highlighting the labor market advantages naturalized citizens have over non-naturalized immigrants. First, US citizens have access to certain federal and local government jobs that non-citizens do not. Also, employers may prefer US citizens over non-citizens for a variety of reasons. Employers may have a taste for discrimination or be fearful of running afoul of immigration laws. Additionally, acquiring citizenship may signal to employers an applicant’s level of commitment to stay in the USA and willingness to invest in US-specific human capital. Finally, there may be selection effects based on unobservable characteristics. Using both cross-sectional (1990 Census and 1994–1998 CPS) and longitudinal data (NLSY), they find that naturalized citizens (1) earn higher wages, on average, primarily due to higher rates of wage growth, (2) are more likely to be employed in public-sector, white-collar, and union jobs, and (3) benefits of naturalization are larger for immigrants from less-developed countries. A later study by Akbari (2008), using data from the 2000 Census, similarly finds that the returns to naturalization are substantially higher for immigrants from developing countries. However, he finds the returns to naturalization to be smaller for migrants from developing countries working in professional occupations, perhaps due to lack of recognition of foreign credentials.

Outside of the USA, other studies find similar results. DeVoretz and Pivnenko (2005) find that immigrants to Canada from non-OECD countries receive a higher naturalization premium than immigrants from OECD countries. Steinhardt (2012) finds that naturalization benefits Turkish immigrants and “third country nationals”Footnote 1 more than immigrants from EU, European Economic Area, or OECD countries. Corluy et al. (2011), examining immigrants to Belgium, find no significant effect of naturalization on wages for immigrants from Western countries of origin. However, there is a positive effect on wages for immigrants from non-Western countries, particularly from North Africa and South America.

Within all of the literature examining the naturalization premium, there is the underlying question of whether the increases in wages or wage growth are due to selection bias, or whether it is a causal effect. Many studies are unable to disentangle these effects due to data constraints. Those that do generally find that the naturalization premium is a combination of both selection and causal effects. As mentioned above, causal impacts may be derived from access to certain jobs only available to citizens, or signaling effects to employers. Selection among immigrants, however, may be positive or negative. Positive selection may occur through successful social integration. As an immigrant assimilates and begins to identify with the culture of the host country, this might lead to both positive labor market outcomes and the desire to obtain citizenship. Further, the desire to obtain citizenship may arise from successful labor market outcomes. That is, if an immigrant secures a successful job in the host country, they may wish to obtain citizenship to ensure their right to remain in the host country (Euwals et al. 2010). On the other hand, negative selection might occur if low-earning immigrants choose to naturalize to access welfare state benefits of the host country (Euwals et al. 2010), or successful migrants may decide to return home if their accumulated savings have higher purchasing power in their home country (Wahba 2015). While selection is generally found to be positive (Bratsberg et al. 2002; Scott 2008), Euwals et al. (2010) find some evidence of negative selection in the case of Germany. However, this negative selection is only with respect to tenured employment probability, which they attribute to immigrants wanting to obtain citizenship before temporary contracts expire.

It should not be surprising that evidence of negative selection is rare in the literature. The naturalization process can be rather costly, in monetary costs as well as time and effort. Under standard utility maximization theory, rational immigrants would not choose to naturalize unless expected future benefits exceed those costs. In the case of naturalizing in order to get welfare state benefits, it is unlikely that the additional benefits received would exceed the costs associated with the naturalization process. Furthermore, in many countries, immigrants must be able to demonstrate economic self-sufficiency before they can become citizens. It is also unlikely that a desire to return to their home country would prevent successful immigrants from naturalizing. Unless the country forbids dual citizenship and has strict regulations governing non-citizens, for example, preventing foreigners from owning real estate or inheriting wealth, naturalizing in the host country would not impose a significant additional cost in that respect. Thus, the costs associated with naturalization process serve as a screening mechanism which tends toward positive selection.

One glaring hole in the literature on US naturalization is that it assumes the process is the same for all immigrants, and that the decision to naturalize is solely a function of demographic characteristics, such as age and human capital. However, while all immigrants wishing to naturalize must follow the same steps, quantitative limits on visa issuance have created a substantial difference in the time costs associated with the naturalization process depending on the immigrant’s country of origin. Depending on the category of visa applied for, immigrants from China, India, Mexico, or the Philippines might have to wait as much as 25 years longer than immigrants from other countries to obtain lawful permanent resident status (US Department of State 2019), which is an intermediate step in the naturalization process. Coon and Chi (2018) find that each additional year of wait time is associated with a 2% reduction in annual earnings for immigrants who entered the USA on temporary work visas. They also find a negative relationship between earnings and wait times for those who entered on student visas and have waited longer than 5 years to obtain lawful permanent resident status. These substantial differences in wait times are likely to deter many immigrants from undertaking the process of naturalizing and realizing potential gains from naturalization. Further, excessive wait times may result in migrants returning to their countries of origin, potentially losing many immigrants that would otherwise contribute significantly to the US labor market. Relaxing and/or removing per-country visa limits would help prevent these unrealized gains.

While there has been a fairly large amount of attention paid in the literature to differences in immigrant origin, for the most part it ignores naturalization, and primarily highlights the differences in human capital between Western Europe and other parts of the world. As such, much of the immigrant population in the USA is lumped into broad groups such as Asia, Latin America, Middle East, or “developing countries.” Very few studies have looked at economic performance of immigrants from specific countries (with Mexico and Cuba being notable exceptions), and those that do are aimed at highlighting underlying human capital differences between countries within a specific region. Lin (2013) examines the labor market performance of ethnic Chinese immigrants to the USA from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Aly and Ragan (2010) compare US labor market performance for immigrants from different Arab countries. Wu and Seeborg (2012) analyze differences in wage convergence between immigrants from Mexico and China in the USA. All three of these studies ascribe the difference in outcomes between these countries to differences in the human capital immigrants bring with them. None of these studies, however, consider the role of naturalization and the effect it may have on labor market access as a contributing factor to differences in earnings.

In the sections below, we estimate the naturalization premium for immigrants from the four main oversubscribed source countries: China, India, Mexico, and the Philippines. Immigrants from these four countries have the longest wait times to obtain green cards, and, thus, naturalization. Understanding how naturalization affects these immigrants will be critical in developing a more efficient immigration system. We compare the estimates for these four countries with estimates for immigrants from the rest of the world. Our findings indicate that the arbitrary visa quota system leads to an inefficient distribution of citizenship.

Data and Methodology

Our aim in this study is to estimate the “naturalization premium” as described by Euwals et al. (2010), according to country of origin. To determine the naturalization premium, we estimate the following wage equation

where \(Y_{i}\) is the annual wage and salary income, \(N_{i}\) is a binary variable equal to 1 if the immigrant is naturalized, \(C_{ij}\) is also a binary variable equal to 1 if individual i was born in country j, where \(j \in \left\{ {China, India, Mexico, Philippines} \right\}\), and X is a vector of individual and demographic control variables. Our estimate of the naturalization premium for each country, j, is \(\gamma = \beta_{1} + \beta_{3} C_{ij}\). As described by Euwals et al. (2010), the naturalization premium consists of three components, such that \(\gamma = \gamma_{c} + \gamma_{ps} + \gamma_{ns}\), where \(\gamma_{c}\) is the causal impact of naturalization, \(\gamma_{ps}\) represents a positive selection effect, and \(\gamma_{ns}\) is a negative selection effect. If the coefficient estimate is positive, this would indicate that the causal impact and positive selection effect outweigh any negative selection effects, and vice versa for a negative coefficient estimate.

This study uses data from the 2013–2017 5-year American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample (Ruggles et al. 2019). We restrict the sample to include foreign-born, working-age males with nonzero income who worked full time.Footnote 2 Additionally, we follow Mazzolari (2009) to restrict the sample to only individuals who were at least 18 years old when they arrived in the USA, and have been in the USA for at least 5 years in order to eliminate those who gained citizenship through their parents’ naturalization and nonimmigrant respondents.

Table 1 reports summary statistics for selected variables. Among all immigrant men who were at least 18 years old when they arrived in the USA, had positive wage and salary income in the year prior to when the survey was administered, and have been in the USA for at least 5 years, mean annual earnings were just over $60,000. Naturalized immigrants earned approximately $23,000 per year more than their non-naturalized counterparts. Indian immigrants have the highest annual earnings with an average of $113,668, while Mexican immigrants have the lowest at $34,312. Across all subgroups, naturalized immigrants have higher earnings.

In the full sample, 49.4% of immigrants are naturalized. Filipino immigrants have the highest rate of naturalization at 74.1%, while Mexican immigrants have the lowest rate at 26.1%. Slightly more than half of Indian and Chinese immigrants are naturalized.

In addition to naturalization status, we include several control variables similar to those proposed by Lin (2013) that might influence an immigrant’s earning potential. We include age, and its square, to proxy for potential work experience. The average age in our sample is 45.5 years old, and naturalized immigrants are, on average, approximately 7 years older. Across all subgroups, the average age is between 42 and 49 years, and naturalized immigrants are older, on average. The largest age difference between naturalized and non-naturalized immigrants is among Indian immigrants at 10.6 years. The smallest difference, 4 years, is found among Filipino immigrants. We also include the number of years, and its square, the immigrant has been in the USA to control for assimilation effects. The average immigrant has been in the USA for 18.5 years. Naturalized immigrants have been in the USA approximately 7 years longer than non-naturalized immigrants. Indian immigrants have the least average experience in the USA, 15.56 years, but the largest gap between naturalized and non-naturalized immigrants, 10 years. Additionally, as a proxy for immigrant networks, we include the share of the immigrant population in the immigrant’s place of residence. We expect areas with larger immigrant populations will provide better labor market opportunities for immigrants in general. This could either be due to immigrants’ propensity to locate in areas with more labor demand, or through information sharing among immigrant networks. Immigrants who speak English will also likely have access to more and better jobs, so we include a variable for English fluency. Mexican immigrants have the lowest rate of English fluency, but also the largest gap between naturalized and non-naturalized immigrants. Over 70% of naturalized Mexican immigrants are fluent in English, compared to only 42% among non-naturalized immigrants. As a final control for human capital, we include education levels. Across the entire sample, 33% have a college degree. However, this number varies widely across country of origin. Approximately half of Chinese and Filipino immigrants have college degrees. However, 87% of Indian immigrants have college degrees, but only 6% of Mexican immigrants have degrees. Interestingly, Indian immigrants are the only subgroup for which the share of college graduates is smaller for naturalized citizens. We also control for whether an individual is currently in school. We expect current students to earn less as they are less likely to be fully engaged in the labor market. Similarly, we include the number of weekly hours worked, as those who work more are likely to earn more. We also include household characteristics. Naturalized immigrants are more likely to be married, with highest marriage rates among Indian immigrants. Mexican immigrants tend to have more children than other immigrant groups. Across all subgroups, naturalized immigrants are more likely to be married and have more children. Since earnings can fluctuate across geographic locations, we include a set of regional controls and whether the household is in a metropolitan area. Finally, we include survey-year fixed effects, and an indicator variable for the decade of arrival to control for potential cohort effects.Footnote 3

Results

Main Results

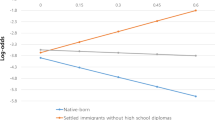

Table 2 presents our results for the estimates of the model presented above. The baseline model, which does not control for country of origin, in Column 1 shows that on average, naturalized immigrants earn 7.2% more than non-naturalized immigrants. These results are consistent with previous findings by Bratsberg et al. (2002), who find naturalized immigrants earn between 5 and 11% more than non-naturalized immigrants. Columns 2–5 introduce controls for country of origin for the USA’ four largest immigrant source countries, allowing for a comparison of the outcomes immigrants from each country face relative to immigrants from all other countries. In general, we find that Chinese, Mexican, and Filipino immigrants earn less than non-naturalized immigrants from other countries, while non-naturalized Indian immigrants earn more. The naturalization premium for Chinese, Mexican, and Filipino immigrants is larger than the naturalization premium for other immigrants, as indicated by the positive and significant coefficients of the interaction term. However, the naturalization premium for Indian immigrants is not only less than that of other immigrants, but is, in fact, negative.

Column 6 includes all four nationalities and produce largely the same pattern of results as found in Columns 2–5. We find that the naturalization premium for immigrants from countries other than China, Mexico, the Philippines, and India is 4.4%, which is smaller than that found in Column 1. Immigrants from Mainland China face a wage penalty when compared to other immigrants, with non-naturalized Chinese immigrants earning 7.9% less than non-naturalized immigrants from the rest of the world. However, the naturalization premium for immigrants from Mainland China is approximately 13.2%. This more than offsets the initial wage penalty, and suggests naturalized Chinese immigrants would earn 5.3% more than non-naturalized immigrants from the rest of the world, and 0.8% more than naturalized immigrants from the rest of the world.

Mexican immigrants face a larger wage penalty than Chinese immigrants, earning 13.6% less than immigrants from the rest of the world. In the case of Mexican immigrants, though, naturalization does not completely offset that loss. Although naturalized Mexican immigrants earn 11.8% more than non-naturalized Mexican immigrants, after accounting for the wage penalty, a naturalized Mexican earns 5.4% less than naturalized immigrants from the rest of the world, and 0.9% less than non-naturalized immigrants from the rest of the world.

The largest wage penalty, 15.8, is faced by Filipino immigrants. However, similar to Chinese immigrants, a substantial naturalization premium of 16.5% offsets this penalty, with naturalized Filipino immigrants earning 0.7% more than non-naturalized immigrants from the rest of the world. However, Filipino immigrants earn 3.7% less than naturalized immigrants from the rest of the world.

Indian immigrants earn substantially higher wages than other immigrant groups. Non-naturalized Indian immigrants earn 27.2% more than immigrants from the rest of the world. However, the coefficients for naturalization and the interaction term suggest that naturalized Indian immigrants earn 12.2% less than non-naturalized Indian immigrants, after controlling for other factors. That is, the wage premium is negative. As mentioned above, a negative wage premium implies that negative selection effects outweigh all causal wage effects and any positive selection effects.

Column 6 includes all four nationalities and produces largely the same results as found in Columns 2–5. We find that the average wage premium for a naturalized immigrant from any country other than the four largest is 4.7%. Naturalized Chinese immigrants earn 8% more than naturalized immigrants from the baseline group, and 18.6% more than non-naturalized Chinese immigrants. Naturalized Mexican immigrants earn 7.9% more than non-naturalized Mexican immigrants, but 7% less than naturalized immigrants in the baseline group, and 2.3% less than non-naturalized immigrants in the baseline group. Similarly, naturalized Filipino immigrants earn 17% more than their non-naturalized countrymen, but still earn substantially less than immigrants in the baseline group, regardless of naturalization. Finally, we find that although naturalized Indian immigrants earn significantly more than naturalized immigrants in the baseline group, they earn less than non-naturalized Indian immigrants after controlling for other characteristics.

The results in Column 6 assume that the effects of changes in covariates other than naturalization on income are the same across all groups. To examine how heterogeneity among covariates might affect our estimates of the naturalization premiums, we estimate the wage equation for each group separately.Footnote 4 These results are presented in Table 3. Examining the other covariates reveals interesting variation in earnings determinants. Mexican and Indian immigrants earn more in areas with higher shares of immigrants in the community, whereas we find no significant difference for other immigrant groups. Fluency in English is associated with higher earnings for Chinese immigrants than other immigrant groups, with fluent English speakers earning 33% more than other Chinese immigrants. Indian and Chinese immigrants have the highest returns to experience in the USA among all groups, increasing earnings by 2.5 and 2.1% for each additional year in the USA, respectively. Chinese and Indian immigrants tend to earn more in Western states, and Filipino immigrants earn more in the Northeast. Chinese and Indian immigrants also appear to have higher returns to education than other groups.

Allowing for heterogeneity among the covariates does not change the sign or significance for any of our estimates of the naturalization premium. However, there are some changes in the magnitude of the estimates. The estimate of the naturalization premium for Chinese immigrants falls from 13.22 to 8.8%. Mexican immigrants’ naturalization premium increases from 11.8 to 18.2%. The estimates for Filipino and Indian immigrants are similar to those reported in Table 2, at 15.4% and -6.1%, respectively. The naturalization premium for immigrants from the rest of the world falls by approximately half, from 4.4 to 2.1%. Taken together, these findings indicate substantial differences in earnings associated with naturalization for Chinese, Mexican, Filipino, and Indian immigrants vis-à-vis immigrants from the rest of the world. In particular, the naturalization premium for Chinese, Mexican, and Filipino immigrants is 4 to 9 times larger than the rest of the world, whereas Indians have a negative naturalization premium.

Education Levels

To further explore possible factors related to the different naturalization premiums, we examine another major difference in terms of immigrant composition among these four countries: education levels. Not only does education impact immigrant earnings, it also can affect their method of entry into the country, and path to citizenship. Generally speaking, Chinese and Indian immigrants are relatively more skilled than Mexican and Filipino immigrants. For example, according to the Department of Homeland Security, 63.6% of Mexicans and 52.5% of Filipinos obtained Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) status in 2013 as immediate relatives of US citizens, whereas 34.5% of Chinese and 29.2% of Indians were in the same category. 51.4% of Indians obtained the LPR status through employment-based preferences, and 27.1% of Chinese were in the same category. A Similar pattern remained in 2017. Given that employment-based green cards are primarily given to individuals with college degrees, and employment-based green cards typically have shorter backlogs, whereas family-based green cards have no education restrictions and longer backlogs, it is important to see if education plays a role in different naturalization premiums received by these countries. We divide our sample into two groups based on highest level of education completed. The first group includes individuals who completed less than 4 years of college. This group includes individuals with less than a high school diploma, a high school diploma, and some college, but not a bachelor’s degree. The second group includes individuals with a bachelor’s degree or higher. We then estimate the wage equation across countries and education levels.

Coefficient estimates for the naturalization premium for these groups are presented in Table 4, along with the top-line estimates from Table 3.Footnote 5 We find that for immigrants with less than 4 years of college, the naturalization premium is higher for Chinese immigrants and immigrants from the rest of the world, when compared to the full sample, and slightly lower for Mexican and Filipino immigrants. Further, there is no significant difference in earning for naturalized Indian immigrants without a college degree. This indicates the negative naturalization premium found in the full sample is driven by higher-skilled Indian immigrants, which can be seen in the results for immigrants with 4 years of college or more. We also find no significant difference in earnings for naturalized college graduates from China and the rest of the world, and a larger naturalization premium for Mexican and Filipino college graduates.

Comparison Regions

In this section, we examine the results for countries from the rest of the world further. Since the rest of the world contains a large and diverse set of countries, we disaggregate further by constructing country groups that are geographically and economically similar to Mexico, China, India, and the Philippines, but do not have long wait times for obtaining lawful permanent resident visas. For the purpose of comparing our results relative to China, India, and the Philippines, we estimate the model on countries with similar incomes, lower-middle and upper-middle income, South Asia, and East Asia and the Pacific. This group includes Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam. For comparison of results relative to Mexico, we estimate the model on countries with similar income, upper-middle income, in Latin America and the Caribbean. This group includes Belize, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Grenada, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, and Venezuela. Finally, we estimate the model on countries included in the Schengen Area of Europe and the UK and Ireland. These countries are economically similar to the USA, have free movement between each country, and have relatively short wait times for immigrating to the USA. In addition to disaggregating by region, we also disaggregate by education level, as above. These results are presented in Table 5.

For the full sample, we find no significant difference in earnings between naturalized citizens and other immigrants from Asia, and no difference in earnings between immigrants from the Schengen Area and UK and Ireland. We find that naturalized immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean earn, on average, 11% more than other immigrants from the region, indicating the causal and positive selection effects outweigh negative selection effects. However, we note that this difference is substantially lower than the difference between Mexican immigrants. For individuals with less than 4 years of college, we find positive and significant difference for all three regions. The naturalization premium for Asian immigrants is approximately half the size of those found for Chinese and Filipino immigrants, and the naturalization premium for immigrants from Latin American and the Caribbean is approximately 6% points lower than that for Mexican immigrants. For individuals with college degrees, we find no significant difference in earnings for Asian immigrants. The naturalization premium for immigrants from Latin American and the Caribbean is less than half the size as the Mexican premium. Finally, college graduates from the Schengen Area and UK and Ireland have a negative naturalization premium.

Discussion

The results presented above highlight stark differences in the naturalization premium among immigrants in the USA. In general, naturalized immigrants earn more than non-naturalized immigrants. However, the differences in earnings that can be associated with naturalization depend largely on the country of origin. We find that the wage differential between naturalized and non-naturalized immigrants from Mainland China, Mexico, and the Philippines is substantially larger than that of the immigrant population as a whole. Further, after allowing for covariates to also differ by country of origin, we find limited evidence of wage differential for immigrants from countries not in the USA’ top four immigrant source countries. Finally, and perhaps most interestingly, we find that Indian immigrants who naturalize earn less than those who do not.

To better interpret our findings, let us first discuss the composition of the non-naturalized group. Since the ACS data only identify foreign-born respondents as naturalized or not naturalized, we do not know the visa status of respondents. Within the non-naturalized group, respondents could have lawful permanent resident visas obtained either through employment- or family-based preferences, temporary work visas (for example, H-1B visa holders), other nonimmigrant visas (for example, student F visas), or could be undocumented. If the non-naturalized group is primarily lawful permanent residents, then the naturalization premium we estimate is capturing the premium from transitioning from lawful permanent resident to citizen. However, if the non-naturalized group is primarily not lawful permanent residents, then the naturalization premium is capturing the benefit from obtaining both lawful permanent status and citizenship. The transition from a temporary visa to lawful permanent resident could potentially be more valuable than the transition from permanent resident to citizen. While we do not have visa status information, we can make some inferences based on constraints placed on our data set and characteristics of the immigration system. First, by restricting our sample to full-time workers, we reduce the probability that respondents are students, since in most cases they are restricted to a maximum of twenty hours per week. Thus, workers who are not lawful permanent residents are likely to be H-1B visa holders or their spouses. Based on data from the Department of Homeland Security (2019), between 2007 and 2017, 94% of H-1B visas awarded were received by workers from India (83%) and China (11%). The Philippines and Mexico were awarded 3% and 1% of H-1B visas over that same period, respectively, with the remaining 2% being distributed among the rest of the world. Further, H-1B visas are almost exclusively awarded to high-skill workers. Similarly, 86% of employer-sponsored green cards are awarded to high-skill workers. While there are no skill-level requirements for family-sponsored green cards, 28% of immigrants who entered the USA prior to 2010 in this category have college degrees. The Department of Homeland Security estimates that in 2015, there were 6.58 million undocumented immigrants from Mexico in the USA, 470,000 from India, 370,000 from the Philippines, and 320,000 from China (Department of Homeland Security 2015). That is approximately twice the size of the population of lawful permanent residents from Mexico. India’s undocumented population is about 80% of the size of its lawful permanent resident population, whereas the Philippines’ and China’s undocumented populations were 64% and 45% the size of their lawful permanent resident populations, respectively. Finally, Pew Research Center estimates that in 2016 only 4% of undocumented immigrants from Mexico had a college degree, while 64% of undocumented immigrants from Asia have a college degree. However, a substantial share of the college degrees are held by undocumented immigrants who have been in the USA for 5 years or less, which are excluded for our sample (Passel and Cohn 2019). Having separated our sample by education level, we can use the above information to make inferences about the composition of the non-naturalized groups. This, in turn, will allow us to determine whether the naturalization premium is primarily capturing earnings differences between naturalized citizens and lawful permanent residents, or whether part of the observed premium is capturing the earnings gains associated with transitioning into lawful permanent resident status.

Based on the information above, it is likely that the subset of immigrants with less than 4 years of college would consist primarily of lawful permanent residents who entered on family-sponsored green card and undocumented immigrants, with the share of undocumented significantly larger among Mexican immigrants. As such, the naturalization premiums estimated for this group largely represent a combination of both the benefits associated with transitioning from lawful permanent resident to citizen, and the difference in earnings between naturalized citizens and undocumented immigrants. Given that Mexico’s undocumented population is substantially larger and less likely to have a college degree, it would be expected that the estimated naturalization premium would be larger, which is indeed what we find.

For the subset of college graduates, disentangling the factors affecting the naturalization premium is more complicated since the non-naturalized group could be more diverse. The non-naturalized college graduates could be either family-sponsored or employer-sponsored lawful permanent resident, H-1B visa holders and spouses, or undocumented immigrants. Based on H-1B allocations, it is likely that there is a large representation among Indian college graduates, and a somewhat smaller representation among Chinese college graduates, and very few in the rest of the sample. It is also likely that a substantial share of Indian college graduates are undocumented, given 92% of non-naturalized Indians are college graduates, and they are almost equally as likely to be undocumented as they are to be lawful permanent residents. There is also likely to be a somewhat smaller undocumented population among Chinese and Filipino immigrants. But it is unlikely that there are many undocumented immigrants among the Mexican college-educated sample, as well as the rest of the world. This leaves the remainder of the sample to be green card holders. Given that the employment-based visa backlog primarily affects Chinese and Indian immigrants, it is likely that college-educated lawful permanent residents from Mexico, the Philippines, and the rest of the world mostly hold employer-sponsored green cards. However, Indian and Chinese green card holders are likely to be a mix of employer-sponsored and family-sponsored. In sum, among college-educated, non-naturalized immigrants, Indian and Chinese immigrants are likely to be a mix of all four possible statuses, with Indians having a higher share of both H-B1 and undocumented immigrants. Filipino immigrants are likely to have a combination of employer-sponsored lawful permanent residents and undocumented immigrants. Immigrants from Mexico and the rest of the world are most likely to be employer-sponsored lawful permanent residents.

Based on this characterization, the naturalization premiums for Mexico and the rest of the world would be primarily due to the transition from lawful permanent resident to naturalized citizen. The naturalization premium for Filipino immigrants would be at least partially based on earnings differences between naturalized citizens and undocumented immigrants. The naturalization premium for Chinese and Indian immigrants would be a combination of differences in earnings due to transitioning to naturalization from lawful permanent resident status, temporary worker, or undocumented.

These findings highlight a potentially important source of unrealized gains in the US immigration system, primarily driven by the method used for visa (green card) allocation. Several previous studies have discussed and shown the labor market benefits associated with citizenship. However, the current immigration law has created a substantial backlog of visa applications from the four largest immigrant source countries, preventing many who may benefit from naturalizing from doing so. To the extent that our estimates are a combination of effects associated with naturalization and transitioning to lawful permanent residency, reducing the visa backlog will contribute to economic gains along both dimensions, even if the visa recipients do not ultimately become US citizens.

Another important factor for interpreting our findings is the extent to which the earnings differences are causal effects, or selection effects. It is likely that our estimates are picking up some causal effects and some selection effects. To the extent that variation in naturalization premiums is being affected by visa backlogs, it is likely that the observed variation in our estimates is due in some part to differences in selection effects. While this study is unable to disentangle how much the naturalization premium is due to causal effects versus selection bias, from a policy perspective, this is somewhat irrelevant. If the effects are causal, not allowing immigrants to naturalize prevents them from realizing their true earnings potential. Optimal policy, therefore, would allow more immigrants from countries with positive naturalization premiums to become citizens. By extension, this would imply issuing more lawful permanent resident visas to immigrants from these countries. If, however, the observed differences are due to positive selection into naturalization, then the policy prescription is the same. Making naturalization difficult undoubtedly aids in ensuring positive selection. If naturalization is costly, it follows that only those who stand to benefit most will undertake the process. However, excessive wait times can make naturalization too costly, thus eroding potential gains. This might dissuade otherwise high-performing immigrants from naturalizing. In cases where we observe positive naturalization premiums, it is also likely that high-earning immigrants at the margin would like to naturalize, but are prevented from doing so due to quota limits. In the long run, these immigrants may ultimately decide to return to their home countries, and these high-performing immigrants will be removed from the US labor pool, thus lowering overall productivity. Making it easier for these individuals to naturalize will make it more likely to attract and retain higher-skilled workers. Thus, the results above suggest that optimal policy would allocate more lawful permanent resident visas to immigrants from China, Mexico, and the Philippines in order to encourage higher rates of naturalization, up to the point where the naturalization premium is similar to that observed among immigrants from other countries.

The policy implications for India, however, are somewhat less clear. If the observed effect is due to negative selection, optimal policy would depend on the cause of the negative selection. If negative selection is due to desire to access welfare state programs, optimal policy would want to discourage naturalization. However, under US law immigrants have limited access to welfare programs. Additionally, Indian immigrants have the highest average income among all immigrant groups, and our results in Table 4 find the negative naturalization premium for Indian immigrants is primarily driven by high-skill workers, who would be less likely to need welfare programs. Thus, this is an unlikely source of negative selection among Indian immigrants. Another potential source of negative selection is that high earners might prefer not to naturalize due to a desire to return home with their accumulated savings. India does not recognize dual citizenship. Therefore, in order to become US citizens, they would be required to renounce their Indian citizenship. Further, there are restrictions on the types of property non-citizens may own. For example, non-citizens of Indian origin may acquire “immovable property,” that is, real estate, with the exception of “agricultural land/farm house/plantation property” (Reserve Bank of India 2017). Such restriction increases the inherent cost of naturalization and might dissuade high-earning Indians from naturalizing. Thus, it is possible that negative selection is occurring if high-earning Indian immigrants intend to return home at some point, but low-earning Indians do not.

There is, however, another channel through which the observed negative effect might be occurring. As mentioned above, positive selection implies that high earners are more likely to naturalize. However, when countries are bound by the visa limit, then some high earners who wish to naturalize are unable to. If this is the case, then the naturalization premium is likely to be underestimated. That is, high earners stuck in the non-citizen pool will drive up average earnings of non-citizens. Thus, allowing these immigrants to naturalize would widen the gap between the two groups by raising the average income among naturalized citizens and lowering average income among non-citizens. If the high-earning talent pool were sufficiently large, it is possible that the estimated negative naturalization premium is not due to a preference for low earners to naturalize, but due to the inability of high earners to naturalize. This might indeed be the case for Indian immigrants, who have the longest wait times for employment-based visas among the four countries analyzed in this study. Depending on the category, wait times for Indian immigrants can be 5–12 years longer than immigrants from other countries (US Department of State 2019). As a result, it is likely that our sample contains a substantial share of workers on H-1B visas. Since these workers tend to be employed in high-earning occupations, this could be driving the negative premiums we find.

One potential method of identifying negative selection would be to examine the rate at which high-earning lawful permanent residents naturalize. Since they would be legally eligible to naturalize 5 years after obtaining lawful permanent resident status, if high-earning immigrants choose not to naturalize after eligibility, this would provide evidence to support the negative selection hypothesis. If, on the other hand, lawful permanent residents do tend to naturalize, this would suggest that the negative earnings differential is an artifact of the immigration quota system. However, since this information is unavailable in the current data, we leave this to future research.

Conclusion

In this study, we examine the naturalization premium for immigrants from the USA’ four largest immigrant source countries and compare them to immigrants from the rest of the world. We find that naturalization is associated with higher earnings for immigrants from China, Mexico, and the Philippines, and lower earnings for Indian immigrants. Furthermore, after allowing covariate effects to differ by country of origin, we find only limited evidence of a naturalization premium for immigrants from the rest of the world.

Our findings suggest an inefficient allocation of citizenship, likely stemming from visa quota limits. Several previous studies have discussed and shown the labor market benefits associated with citizenship. However, the current immigration law has created a substantial backlog of visa applications from the four largest immigrant source countries, preventing many who may benefit from naturalizing from doing so. While we acknowledge that this study does not control for selection into naturalization, we believe that selection effects are at least partially driving our observed results. However, based on the current system of visa allocation, selection into naturalization, or at least the timing of naturalization, is not entirely up to the immigrant. This increased wait time increases the cost of naturalization, possibly preventing otherwise high-performing immigrants from naturalizing. In fact, our findings regarding Indian immigrants suggest that the current immigration system may be leading to negative selection into naturalization.

Our aim in this paper is to take a first step in examining an otherwise ignored source of inefficiency in access to US citizenship. Though we find that immigrants from the four oversubscribed countries face different naturalization premiums, data limitations prevent us from identifying the true cost of the visa quota system. Excessive wait times can prevent immigrants from entering the USA in prime earning-growth years of their lives. This can put new immigrants at a disadvantage in terms of earnings assimilation. Further, immigrants who enter on temporary visas lack the same labor mobility as permanent residents and citizens. This, too, can limit earnings growth, as well as lead to a general skills mismatch in the labor market. Thus, barriers to permanent residency and naturalization could be a contributor to differences in assimilation rates identified in previous literature. Finally, excessive wait times can prevent high-performing immigrants from coming all together, preventing US employers’ access to a talented labor pool. All of these lead to inefficiencies in the US labor market, and can be prevented by removing artificial barriers to obtaining citizenship. We believe that more research on this area is necessary in order to inform effective immigration policy.

Notes

Third country nationals refer to countries outside of the EU that do not have bilateral labor agreements with Germany.

Estimates that include part-time workers, as well as for female workers, yield similar results. These results are available upon request.

For ease of exposition, we exclude these results from the tables below. In general, we find real earnings were higher for respondents in the 2015–2017 survey years, relative to 2013. Additionally, we find cohorts entering after 1980 earn 10–20% less than those entering prior to 1980. These results are consistent with prior findings by Borjas (1995). Our main findings are robust to inclusion/exclusion of survey-year and cohort fixed effects.

A fully interacted model, available upon request, indicates significant differences between the effects of several covariates across countries.

For ease of exposition, we withhold coefficient estimates for the other control variables from the table. These results are available upon request.

References

Akbari, Ather H. 2008. Immigrant Naturalization and Its Impacts on Immigrant Labour Market Performance And Treasury. In The Economics of Citizenship, ed. Pieter Bevelander and Don J. DeVoretz, 127–154. Holmbergs: MIM/Malmö University.

Aly, Ashraf E.-A., and James F. Ragan Jr. 2010. Arab Immigrants in the United States: How and Why Do Returns to Education Vary By Country of Origin? Journal of Population Economics 23: 519–538.

Borjas, George. 1985. Changes in Cohort Quality, and the Earnings of Immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics 3(4): 463–489.

Borjas, George. 1995. Assimilation and Changes in Cohort Quality Revisited: What Happened to Immigrant Earnings in the 1980’s? Journal of Labor Economics 13(2): 201–245.

Bratsberg, Bernt, James F. Ragan Jr., and Zafar M. Nasir. 2002. The Effect of Naturalization on Wage Growth: a Panel Study of Young Male Immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics 20(3): 568–597.

Chiswick, Barry. 1978. The Effect of Americanization on the Earnings of Foreign-born Men. Journal of Political Economy 86(5): 897–921.

Chiswick, Barry. 1986. Is the New Immigration Less Skilled than the Old? Journal of Labor Economics 4(2): 168–192.

Coon, Michael, and Miao Chi. 2018. Visa Wait Times and Future Earnings: Evidence from the National Survey of College Graduates. Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-018-0024-6.

Corluy, Vincent, Ive Marx, and Gerlinde Verbist. 2011. Employment Chances and Changes of Immigrants in Belgium: The Impact of Citizenship. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 52(4): 350–368.

DeVoretz, Don J., and Sergiy Pivnenko. 2005. The Economic Causes and Consequences of Canadian Citizenship. Journal of International Migration and Integration 6(3): 435–468.

Duleep, Harriet O., and Mark C. Regets. 1997. Measuring Immigrant Wage Growth Using Matched CPS Files. Demography 43(2): 239–249.

Euwals, Rob, Jacob Dagevos, Mérove Gisberts, and Hans Roodenburg. 2010. Citizenship and Labor Market Position: Turkish Immigrants in Germany and the Netherlands. International Migration Review 44(3): 513–538.

Gathmann, Christina, and Nicolas Keller. 2013. Returns to Citizenship: Evidence from Germany’s Immigration Reform. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 4738.

Helgertz, Jonas, Pieter Bevelander, and Anna Tegunimataka. 2014. Naturalization and Earnings: a Denmark-Sweden Comparison. European Journal of Population 30(3): 337–359.

Lalonde, Robert J., and Robert H. Topel. 1992. The Assimilation of Immigrants in the US Labor Market. In Immigration and the Workforce: Economic Consequences for the United States and Source Areas, ed. George J. Borjas and Richard B. Freeman, 67–92. Chicago, Il: University of Chicago Press.

Lin, Carl. 2013. Earnings Gap, Cohort Effect and Economic Assimilation of Immigrants from Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan in the United States. Review of International Economics 21(2): 249–265.

Mazzolari, Francesca. 2009. Dual Citizenship Rights: Do They Make More and Rcher Citizens? Demography 16(1): 169–191.

Pew Research Center. 2015. Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065: Views of Immigration’s Impact on U.S. Society Mixed. Washington, D.C.

Passel, Jefferey, and D’Vera Cohn. 2019. U.S. Unauthorized Immigrants Are More Proficient in English, More Educated than a Decade Ago. Retreived July 25, 2019 from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/23/u-s-undocumented-immigrants-are-more-proficient-in-english-more-educated-than-a-decade-ago/.

Reserve Bank of India. 2017. Foreign Exchange Management (Acquisition and Transfer of Immovable Property in India) Regulations, 2000. Retrieved from Foreign Exchange Management Act Notification: https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/BS_FemaNotifications.aspx?Id=175.

Ruggles, Steven, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, Erin Meyer, Jose Pacas, and Matthew Sobek. 2019. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 9.0. University of Minnesota. Retrieved July 17, 2019, from http://www.ipums.org.

Scott, Kirk. 2008. The Economics of Citizenship: Is There a Naturalization Effect? In The Economics of Citizenship, ed. Pieter Bevelander and Don J. DeVoretz, 107–125. Holmbergs: MIM/Malmö University.

Steinhardt, Max F. 2012. Does Citizenship Matter? The Economic Impact of Naturalizations in Germany. Labour Economics 19(6): 813–823.

US Department of Homeland Security. 2015. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Retrived from https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook.

US Department of Homeland Security. 2019. Lawful Permanent Residents Data Tables. Retrived from https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/lawful-permanent-residents.

US Department of State. 2016. Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-sponsored and Employment-based preferences Registered at the National Visa Center. Retrieved from https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Statistics/Immigrant-Statistics/WaitingListItem.pdf.

US Department of State. 2019. Visa Bulletin for June 2019. Retrieved from https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/legal/visa-law0/visa-bulletin/2019/visa-bulletin-for-july-2019.html.

USCIS. 2016a. Citizenship Through Naturalization. Retrieved from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services: https://www.uscis.gov/us-citizenship/citizenship-through-naturalization.

USCIS. 2016b. Per Country Limit. Retrieved from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services: https://www.uscis.gov/tools/glossary/country-limit.

USCIS. 2016c. Visa Availability and Priority Dates. Retrieved from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services: https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/green-card-processes-and-procedures/visa-availability-and-priority-dates.

Wahba, Jackline. 2015. Who Benefits from Return Migration to Developing Countries? IZA World of Labor, 1–10.

Wu, Yujie, and Michael C. Seeborg. 2012. Economic Assimilation of Mexican and Chinese Immigrants in the United States: Is There Wage Convergence? Economics Bulletin 32(3): 1978–1991.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chi, M., Coon, M. Variations in Naturalization Premiums by Country of Origin. Eastern Econ J 46, 102–125 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-019-00149-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-019-00149-0