Abstract

This article seeks to contribute to ongoing debates on gender equality in energy development projects. This article adopts a feminist critical standpoint to assess initiatives on gender and energy in international development. While recognizing the benefits of applying gender analysis to map out the divergences in access and opportunities in energy, this article stresses three recurring issues in energy development studies: a dangerous return of the ‘efficiency approach’ of women in energy and development; the erroneous interchangeability of gender as a ‘women only’ issue; and the diffusion of ‘feminization of energy poverty’ discourses. This article stresses how international organizations and practitioners in energy are echoing the already critiqued concept of ‘feminization of poverty’ and how this can unintentionally undermine the efforts to achieve gender equality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Poverty has many faces and dimensions, affecting many people across the globe. But since the inception of global international aid initiatives in the 1960s–1970s, international organizations are consistently asserting that women are the poorest among the poor (UN 1995).Footnote 1 This realization led to the coining of the ‘feminization of poverty’Footnote 2 concept, a term which stresses predominantly the income-based disparities men and women experience, especially in the ‘developing’ world (Jackson 1996). Throughout the following decades, women in less industrialized countries have been targeted by countless initiatives aiming at reducing local income poverty. However, studies monitoring the effectiveness of these measures indicate that in some cases, women experienced a worsening of their conditions in society rather than the intended outcome (Jackson, 1996, 1998; Kalpana 2005; Sengupta 2013; Ukanwa et al. 2018). Particularly, feminists have highlighted the dangers hidden behind these initiatives (Coulter 2009) especially when an appropriate gender analysis in planning, methods and delivery is not carefully implemented. This is particularly frequent when projects focused exclusively on women and when the tools to analyze gender disparities were reduced to gender-disaggregated data. This condition exacerbated conflicts and altered the already precarious relation dynamics between heteronormative couples (Calkin 2015).

The main point this article aims to discuss is that despite earlier criticisms on how development institutions targeted women’s poverty, some ongoing energy development initiatives are reproducing and replicating the same potentially dangerous discourses and approaches. For example, countless of energy development initiatives, discussed later in this article, claim that energy access can reduce gender inequality. However, feminist scholars and practitioners pointed out how technological and financial determinism linked to energy access cannot fix gender inequality.

A misalignment in the way gender inequality is understood leads to misinterpretations of the key messages. For example, early international development literature on Gender and Energy was predominantly practitioner-based (grey literature), women-focused, and tended to stress with certainty the positive changes in gender equality through modern electricity/energy services (Cannon and Chu 2021). Several development organizations such as the Asian Development Bank (2015) and the World Bank (Köhlin et al. 2011) stated: ‘The literature on gender and energy suggests that providing electricity to communities and homes, and motive power for tasks considered women's work can promote gender equality’ (Köhlin et al. 2011: viii). Similar considerations have also been found in academic literature, especially in rural geographies (Oparaocha and Dutta 2011; Sovacool et al. 2013; Chikulo 2014). In their discourses, it is clear that access to modern energy services is somehow linked to gender equality and the argument is often around health and time. In fact, especially in rural areas of the Global South, an overwhelming amount of evidence can be collected on women’s time poverty because of the pre-established gendered role in energy provision and preparation of meals Clancy and Roehr 2003; Blackden et al. 2006; Kes and Swaminathan 2006. More recently, evidence points at a shift in family time for women in rural Kenya adopting new clean cookstoves (Jagoe et al. 2020). However, while there are important benefits brought by electricity services to both men and women, such as cooling for health and nutrition (Khosla et al. 2021), there are some important pitfalls in the way energy is portrayed in relation to gender inequality.

Moreover, while it is widely known that gender is a social construct and is the constitutive element of power inequalities between sexes, classes, and ethnic groups (Scott 1986) studies in energy and gender rarely attempt to understand the cultural factors that engendered local gender roles and relations in different geographies (Listo 2018; Fathallah and Pyakurel 2020). In this sense, to understand whether energy access is a key factor in shifting pre-determined gender roles we need to talk about the power structures which sustain such ideologies and include a feminist perspective in the discussions. In fact, as highlighted by Bell et al. (2020) feminist theory offers a valuable contribution in the understanding of power structures especially in energy research (Bell et al. 2020). However, intersectional, postcolonial and post-structuralist feminist approaches to energy access is still an overlooked topic. In conducting a narrative review of 57 articles, Cannon and Chu (2021) found that only 18 papers looked at gender and energy beyond cis-heteronormative identities and that only one paper applied queer theory. Fathallah and Pyakurel (2020) suggest there might have been a misuse of gender as category of analysis, which is not just about the differences between men and women. Gender as category of analysis is the constitutive element of power inequalities between sexes, classes and ethnic groups (Scott 1986). In Scott’s definition of gender as category of analysis we already find an encompassing, multidimensional lens which deviates from the mere understanding of women/men as biological category. However, most early energy studies left this assumption largely unchallenged (Fathallah and Pyakurel 2020), leading to a lack of understanding about how an unequal distribution of energy services around the world affects non-normative identities, such as migration status, sexuality, and ethnicity.

It is perhaps more appropriate to talk about energy’s potential to increase the quality of life for all people of all gendered identities, and particularly for individuals whom, because of pre-established gendered roles, are more exposed to the negative consequences of energy poverty and unsafe fuels usage. Hence, access to resources (and in this case energy) is only one component of a larger process which involves a combined intervention to shift preestablished and hard-to-break ideologies (classism, racism, and patriarchy to name a few) which are responsible for the perpetration and reproduction of inequalities within society. An example of a combined action (social justice principles with energy equity) is gender mainstreaming in energy development. In this case, women are incorporated in every step of the energy production chain (from policies to distribution) which is now called energy justice (Sovacool and Dworkin 2015). In a recent publication, Feenstra and Özerol (2021) argue that ‘The objective of gender and energy policy research is an engendering energy policy that enables a fair energy distribution between women and men, recognises gendered energy needs, and contributes to equal participation of women and men in the energy sector.’ However, Alston (2014: 282) already pointed the limitations of gender mainstreaming approaches as ‘it has not necessarily resulted in advances for women, as it is usually associated with a winding back of women-focused policies and programs […] Further, is it about integrating women into male normative systems or about transforming those systems to achieve radical change?’.

The incorporation of all women, independently of their biological sex, in the path of an equal process of decision-making around energy access, energy transition and energy policy in general is fundamental to redistribute power especially in a masculinized and overpoweringly men-based institutions (especially in the oil and gas industry)5. The achievement of the most basic human needs such as clean water, safe food and reliable energy access should not start with a patriarchal infrastructure which inserts women to satisfy a diversity tick box, but it should begin with gender equity and gender equality. Once patriarchy, classism and racism are eradicated, we can truly say that energy and gender are positively linked; until then, any discourse which attempts to enshrine energy as an agent for gender equality can be misleading.

This article’s final critique is about the ontological ground in which the disadvantages women living in energy poverty experience, such as time and income poverty, and lack of opportunities. The term poverty, time poverty and disadvantages are predominantly conceptualized within a western, neoliberal perspective which assigned time poverty, lack of opportunities and income poverty a negative connotation within a system of values in which profit is the most important value.

This article builds on existing critiques and intends to flag the dangers and the limitations embedded in the current interpretation of gender in energy and development studies and discourses. Moreover, it re-proposes the use of gender as originally intended by Scott (1986) as the ‘constitutive element of social inequalities which includes discriminations based on sexuality, class, ethnicity, and race’. Furthermore, to assess the possible return of the feminization of (energy) poverty discourses, this article adopts the work of Sylvia Chant (2007) as a critical lens. The combination of Scott’s theory and Chant’s critical contribution helped flag: a) the reproduction of efficiency models; b) the misuse of gender as women only concept and c) the dangerous return of the ‘feminization of poverty’ discourses in energy and development studies and practices.

This article is structured as follows, the first part flags out the similarities between gender and development discourses and the literature on gender and energy development. The second part introduces Chant’s feminization of poverty’s ideas applied to energy studies, and the third part reflects on the dangers of reproducing the feminization of energy poverty narratives for gender equality.

Gender and Energy in Development

Women in Development—also known as WID—was one of the earliest initiatives tackling the ‘feminization of poverty’, characterized by the deployment of several initiatives to increase women’s economic resources through microcredit programmes, Conditional Cash Transfers (CCTs) policies and female-only cash in hand programmes. In 2006, Muhammad Yunus was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for founding the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh—considered a powerful strategy to combat poverty (especially women’s poverty) (Wilson 2011). Early critiques of WID emphasize how the feminist principle of gender equality have been targeted almost exclusively in terms of access to finances and income-generating opportunities. The idea of ‘feminization of poverty’ rose from a context where ‘poverty’ was conceptualized mainly as income paucity (Chant 2008) and its immediate solutions or anti-poverty measures, such as CCTs and microcredit were seen as having ‘rarely relieved women of the onus of coping with poverty in their household, and has sometimes exacerbated their burdens’ (Chant 2008: 165).

In this sense, improving the efficiency of domestic chores is described as central to freeing women’s time. Women’s time ‘poverty’ is a concern not only for justice reasons, but also because it affects other development measures aiming to address gender equality and reduce poverty (Clancy et al. 2015). Similarly, looking into multiple dimensions of poverty and considering energy services and infrastructure, development organizations are once more proposing immediate one fit for-all technical solutions to address energy-poverty and gender inequality. That is the case with clean technology access mirroring microcredit solutions and CCTs, rather than aiming to understand the core determinants of the unbalanced burden of energy provision and usage.

The critiques of WID encouraged the development of a new approach called Gender and Development (GAD) in the 1980s, which primarily aimed to challenge gender relations and improve the position of women in society. The assumption was that an access-based approach was insufficient to challenge a long-established hierarchy of power, even if women had more resources. International development initiatives like the Millennium Development Goals used GAD frameworks with the foundational idea that gender moved beyond the income-centred sets of action, embracing a more comprehensive notion of equality based on the principles of freedom, solidarity, tolerance, and shared responsibility.

In that sense, Kofi Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations highlighted the extent to which gender equality was a prerequisite to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (Duflo 2012), turning gender equality from ethical principle to a development goal. However, feminist literature notes that even an equal distribution of opportunities does not effectively change gender disparities. The gender pay gap, gender-based violence and unbalanced reproductive responsibilities are still some of the gendered issues on-going in several countries such as France and the UK, where there has been political action towards the equality of opportunity (Chant 2014). Moreover, Cornwall and Rivas (2015) feared that focusing on gender differences created a wider divide between sexes, while systematically ignoring the other levels of complexities, including race, class, ethnicities and sexualities.

Mimicking the development of anti-poverty measures regarding ‘female poverty’, women’s disadvantaged conditions in the context of energy poverty inspired a crescendo of international measures and public–private initiatives, e.g., clean cookstoves or CCS initiatives in Kenya, solar electric cookers in India and increasing interest in sustainable energy in rural areas. For international organizations such as UN-Women, and the World Bank, access to cleaner technologies and sources is, therefore, a matter of gender equality (UNEP 2016). One of the first examples of energy impacts on women’s economic empowerment is the Multi-Functional Platform (MFP), a diesel generator providing electricity for refrigerators, lighting, and other appliances, such as water pumps and cereal grinders.

In 1993, the UNDP started a pilot project with Mali’s Government to ‘simultaneously distribute energy services, empower women and support local activities’ through the distribution and implementation of 500 MFP from 1999 to 2004 (Sovacool et al. 2013). This was then replicated in numerous countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the UNDP, the success of the MFP can be seen on different levels; women who own and manage the machine have higher incomes, more economic independence, and more time for education, and ultimately, achieved a better social status and a higher quality of life than women who do not have access and/or control over the MFPs. Moreover, according to Sovacool (2012) villages’ incomes increased from 1999 to 2004. Table 1 below indicates the similarities between WID-GAD and Energy and Gender development projects.

Table 1 shows some examples of the striking similarities between WID and GAD approaches to Energy and Gender development initiatives, including approaches that had already been criticized by feminist scholarship for worsening women’s conditions. For example, a focus on energy access which emphasizes women’s economic empowerment deriving from energy-related economic activities does not alone deliver important transformations in gender equality because gendered power structures are not challenged, as already found in microfinance programmes (Kalpana 2005; Cornwall et al. 2008). Also the technological and business in hand approach delivered by programmes such as Solar Mamas, while creating opportunities to initiate financial inclusion and technological access, such approaches stand on the theoretical basis that women should be active participants to the economy. However, such assumption can be problematic, as an excessive focus on women’s financial independence may exacerbate the tensions between men and women and worsen women’s conditions (Mayoux 2001; Molyneux 2006). Winther et al. (2017) show how in some cases in northern India and Zanzibar, electrification highlighted the social divide and strengthened patriarchal structures. Silberschmidt (2001) reports that when a sudden change in the social structure occurs, such as when women become economically independent ‘Many men expressed outright jealousy and fear that when wives have their own business projects outside the home they may feel attracted to other men’. Clearly, no change (however positive) occurs without unintended negative consequences. This suggests that when attention is given exclusively to the financial wellbeing of women, without challenging pre-existing gender ideologies this can be counterproductive in the efforts to eradicate patriarchy and can exacerbate violent behaviour towards women. This is shown, for instance, in Kerala (India), where Wilhite (2013) showed how electrification increased dowry expectations with the inclusion of electrical appliances, increasing financial burden of families, and reinforcing gender inequalities in household duties. Similar unintended consequences have occurred in energy development programmes with a pointed focus on women. A study found that in rural South African villages, electrification increased the perceived income disparity between genders (Matinga and Annegarn 2013). The previously discussed work by Winther et al. (2017) also highlighted socially divisive and patriarchy-strengthening effects of electrification. Still, current programmes aiming at deploying sustainable energy in developing countries still follow the same pattern: a focus on financial or technological transition and training. While increased focus on gender in global development and poverty reduction programmes helped to channel more resources to women in the last two decades (Chant 2008), the eradication of poverty does not guarantee an improvement in women’s decision-making power and legal rights within public and private spheres.

Chant’s argument also applies to energy programmes focused on women’s economic empowerment, such as: solar lamps, micro-enterprises, multifunctional platforms and small hydropower plants. The programmes Solar Sister (SS) in Africa and Barefoot College (BC) in India tackle energy access and availability, offering women the opportunity to learn business activities, increase their income and acquire new skills. These renewable energy projects focus on rural women, typically in areas where strong patriarchal norms are in place. While some claim that there are positive transformative outcomes of a technical and economic integration of women in society, there is no guarantee that an actual shift in pre-existing gender relations and opportunities is occurring because of economic empowerment or technical training. For example, in their study of SS programmes in rural Tanzania, Gray et al. (2019) argue that economic empowerment provided by the solar lanterns also encompassed other forms of empowerment such as improving women’s self-esteem and autonomy. Some women also reported of feeling proud and stronger (Gray et al. 2019: 38). What often miss in these types of analysis is the realization that the research is valid at a specific point in time. For example, an analysis of such programmes realized soon after its inception, will inevitably lead to positive responses by its beneficiaries, especially among those who have been deprived of resources and opportunities. I argue that a long-term assessment of such programmes is currently missing in most of research investigating gender equality and energy. Research, in fact, demonstrates that societal subversion norms and values, particularly of long-standing patriarchal ideologies, do not occur in a short amount of time. Mininni (2021) also argued that energy related initiatives which foster women’s integration in the local economy led to a greater gender equality in energy, and that such programmes (BC & SS) are ‘needed to engender transformative change’ (p.), however, the same author also claims that the sociocultural background can be challenging to subvert current social structures and hierarchies. In this sense, the benefits of women’s empowerment initiative via energy projects are limited to an economic empowerment, meaning offering women the opportunity to work in and with energy. As argued in this article, the economic empowerment approach, while providing a much needed basis for women’s integration in the economy, does not necessarily lead to a greater gender equality in the sense of subversion of pre-existing patriarchal norms.

Several cases reporting the efforts of development projects on alleviating women’s chores show a shift in the burden or even worse conditions for women. This is because women are generally in charge of domestic work, and without a re-balance of chores between men and women, the latter becomes overburdened with productive and reproductive activities. In her work, Jackson (1998) reports that even if development programmes focus on training women as entrepreneurs, they often cannot participate in development projects because they are already overburdened with domestic chores and have no time to become involved. Similarly, energy-development programmes also target gender equality by focusing on women living in energy poverty mostly in terms of the financial benefits linked to energy access, as the UNDP (2011: 3) states:

‘Energy has significant links to gender equality. First, women and girls are often primarily responsible for collecting fuel and water at the community level. Also, poor women tend to participate in the informal economic sector (for example, the food sector)’.

The statement above clearly points out how, due to existing gender divisions of labour, the task of collecting firewood and fetching water mainly falls on women (Cecelski 2000; Skutsch 1998, 2005; FAO 2011). Therefore, when local governments do not deliver on infrastructure for clean and potable water, or grids to supply electricity, women are depicted as the main providers of basic services, sacrificingFootnote 3 their time and working hours to provide these resources. Most of the academic and grey literature on Energy and Gender (EG) echoes the UNDP statement, agreeing that women can develop and achieve equal opportunities through modern energy access (Clancy et al. 2012). Moreover, practitioners of energy access advocate that energy access has become a fundamental way to redistribute benefits for men and women, equally (ENERGIA 2019).

This entails a fundamental shift in energy development, from energy as a resource (object), which should be equally enjoyed by men and women, to a new interpretation of energy as a tool to further gender equality. Energy, as object and service, is now invested with a new function: the promotion of gender equality. This ‘agentification’ of energy as gender equality catalyst is problematic. Firstly, it seems to assume that all women and girls living in energy poverty are the main energy and water providers everywhere in the world; secondly, it promises structural changes which are not always possible, e.g. energy access provided in a context of rigid gender roles will not change fundamentally the position of women in the society; thirdly, by ‘enshrining’ energy with the feminist mission to achieve gender equality, it alleviates human’s responsibility to challenge the structures that created inequality in the first place.

The Feminization of Energy Poverty

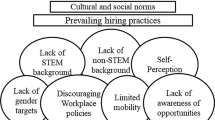

This article adopts Sylvia Chant’s critique of the feminization of poverty, following five main ideas extrapolated from her major works (Chant 1998; 2006, 2008, 2013; Chant and Sweetman 2012). Through Chant’s critique of the feminization of poverty, I identified how discourses on the feminization of poverty tended to share common characteristics with the energy and gender discourses, namely: 1) women are poorer than men; 2) women’s poverty tends to coincide with household headship; 3) women tend to suffer the effects of poverty in the long-term; 4) women are more likely to suffer ‘extreme’ poverty then men; 5) women face more obstacles in escaping poverty. Using Chant’s concepts as guiding tools, it is possible to create a conceptual diagram to assess energy and gender initiatives. Figure 1 shows Chant’s main points about the feminization of poverty are simply reproduced in discourses and initiatives on energy development.

Author’s Elaboration

Chant’s points (1–2), ‘women experience a higher incidence of poverty than men’ have been mimicked in the scholarly literature on energy access (points 1-2E) in developing countries Sovacool 2012; Habtezion 2012; Sovacool et al. 2013; Winther et al. 2018), as well as in Europe (Sánchez-Guevara Sánchez et al. 2020), as discussed in the previous section. Cecelski (1995) asserts that poor women in rural areas of developing countries are the most vulnerable group because they carry heavy loads of firewood across long distances and cook on smoky fires that may cause them and their families to develop lung disease. However, there are studies highlighting the absence of sufficient evidence to generalize firewood collection as a women’s only role. A study from the World Bank (Blackden et al. 2006) reviewed data on the time allocated by men and women in household chores and non-commercial energy in Benin, South Africa, Madagascar and Ghana, respectively, in 1998, 2000, 2001 and 1998–99; and the results are disparate. In rural areas of Benin and Ghana, women are largely responsible for the collection of firewood, while in Madagascar; it is seen as a man’s task.

Moving forward in the critical map above, point 3E can be unfolded in the energy and gender literature, women seem to suffer disproportionally the consequences of energy poverty in respect to men, including:

-

(1)

Health risks related with the use of polluting cookstoves (Amegah and Jaakkola 2016; Rosenthal et al. 2018; Anenberg et al. 2017).

-

(2)

Health/safety risks related to collecting firewood (Chynoweth and Patrick 2007; UNEP 2016; Afrotechana 2016).

While it is fairly certain that inhaling the toxic fumes of firewood combustion used for cooking is detrimental for one’s health (WHO 2016; Anenberg et al. 2017), the discourse of energy practitioners and development agencies seems to overemphasize the extent to which this burden falls, almost exclusively, on women, neglecting children, men and the elderly. For example, Bhattasali (2005) found that rural Indian women are inhaling the equivalent of 20 cigarettes every day from indoor smoke. While the paper brings forth some interesting insights, there are some key aspects left unchallenged: 1) how did the author ‘isolate’ the inhaled smoke from other types of pollutants the participants may have been exposed during the day? Moreover, the study did not mention, nor did it seem to find relevant that perhaps children, the elderly and men in the same household may also be exposed to the same risks. This omission is also noted in relation to other negative consequences linked to inhaling smoke, such as asthma, cataracts and chronic headaches, amongst others (Victor 2011).

The reason for this emphasis on women’s burden lies in the numbers, the WHO/UNDP (Bailis et al. 2009) reported that 44% of deaths caused by indoor air pollution from solid fuels are of children, and of the 56% of adults, 60% are women. The feminization of the negative effects of traditional energy sources has sparked countless initiatives and investments from the private sector to public initiatives for clean cookstoves deployment in the development world. However, by neglecting men, children and the elderly from discourse, these may fuel the narrative that inhaling indoor smokes is a women’s problem, reinforcing gender divisions rather than encouraging equality.

Similarly, several studies indicate the negative consequences of procuring firewood, especially when the gathering areas are distant from the villages. While it is important to report and acknowledge that the lack of services and infrastructure may lead to negative events, the focus of these studies should not be on the practices of gathering firewood as the main culprit for sexual assault, but rather on the origins of sexual assaults. Efforts to eradicate the risks of sexual violence are mostly employed in the deployment of fuel efficient stoves and even establishing ‘firewood patrols’ (Patrick 2007), while there is no mentioning on the end of sexual violence, as the main issue to eradicate.

This leads to the third node (4E) ‘women suffer more the consequences of energy poverty’ can be referred to in the EG literature to ‘time poverty’ as a women’s only crisis. In the energy literature, women lack time because they are responsible for collecting firewood and cooking (Clancy et al. 2007; Sunikka-Blank et al. 2018; Arora 2013). According to Clancy et al. (2015: 965), time poverty can be conceptualized as ‘the condition in which an individual does not have enough time for rest and leisure after taking into account the time spent in productive and reproductive work’. Oparaocha and Dutta (2011) support the idea that energy poverty affects more women than men, emphasizing that the real energy crisis is rural women’s time. Time spent in collecting wood and transporting water over great distances, added to the long-established reproductive roleFootnote 4 for women, hinders their capacity to work outside their households and the potential to escape the poverty cycle (Abdourahman 2017). As it is thought that women generally have longer working hours than men Clancy et al. 2015), modern sources of energy access and technologies represent additional time saved to spend on leisure activities, studying, building their human capital or creating better opportunities to increase their productive roles inside and outside the household (Skutsch 2005; Sengendo 2005; Panjwani 2005; Clancy et al. 2007; Costa et al. 2009).

It is important to emphasize that when time is evaluated and ‘judged’ in terms of economic opportunities, the energy literature positively stresses how women reinvest their time in income-generating activities (Pueyo and Maestre 2019; Pueyo et al. 2020), which will give them more financial independence and, perhaps, more bargaining power. Other studies stress the positive impact of the reduction of labour and physical efforts (Cecelski 2002), while more hedonic activities such as of having leisure and resting time (Mahat 2004; Pereira et al. 2011), are generally understudied as a positive outcome of energy access.

What is critically missing from these studies on women’s allocation of time and energy access is an understanding on the impact of access to leisure and education for men and children. For example, men’s improvement in education is critically neglected, and perhaps assessing the educational angle is a more effective tool to address the systematic reproduction of gender inequalities. For example, Levtov et al. (2014) found that men’s educational attainment ‘is associated with more equitable practices, including more participation in the home and reduced use of violence’.

In fact, several studies suggest that access to electricity resulted in an increase of workload for women rather than the opposite. While these types of observations bring light to an overlooked issue of energy studies, academics and practitioners should shift discourses from ‘how women should spend their time’ in rural areas to ‘what women want to do with their time’. The risk associated with prescriptive discourses on time allocation is that it deliberately promotes a western-centric lifestyle, which assumes that not only time should be spent on accumulating capital but it has to be done efficiently. Appliances are thought to be ‘saving’ women’s time so that they can reallocated that time in other income-related activities.

The last point (5E) ‘refers to the obstacles women face in benefitting from modern energy’, a condition that can only be addressed through women’s empowerment (Standal and Winther 2016; Winther et al. 2018, 2019; Kim and Standal 2019). Some scholars and NGOs taking a gendered approach to understand energy poverty argue that using energy access as a tool may empower women economically, because women face more obstacles to accessing and benefitting from energy. The ENERGIA’s WE programme (2014–2017), aim to scale up ‘proven business models that will strengthen the capacity of 3000 women-led MSEs (micro and small enterprises) to deliver energy products and services to more than 2 million consumers’ (Dutta et al. 2017: 8). Similarly, the Women’s Empowerment Fund, funded by the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves, developed business models to ‘empower women energy entrepreneurs in the clean cooking sector’ (Dutta et al. 2017: 8). Even in more recent debates (Winther et al. 2019), empowerment and gender equality are strictly tied to equal access to electricity.

Therefore, questions regarding more structural changes such as gender roles and relations are not currently tackled in energy scholarship. In other words, why are we focusing on the differences in energy access rather than shifting oppressive gender roles? Does electricity exacerbate gender divisions, does it reinforce existing gender roles? Do energy development plans exacerbate existing gender divisions? Standal and Winther noted that in India ‘women's agency and decision-making power were not strengthened with the electrification process. On the contrary, it could be said that the channelling of more resources through the dowry system after electrification reinforced the patriarchy and structures of inequality.’ (Standal and Winther 2016: 42). Given these findings, why is the energy scholarship insisting on claiming gender equality through energy?

These cases reinforce the need of what Chant conceptualizes as the ‘feminization of responsibility and/or obligation’, a concept associated with the observation of the ‘unevenness between women’s and men’s input and their perceived responsibilities for coping with poverty’ (Chant 2006: 204). Findings from studies on rural areas in Guatemala, Kenya, Bangladesh, Nepal and the Philippines show that while women’s responsibility for the survival of their household is intensifying, men’s responsibility seems to be restricted or even diminishing (Chant 2006: 205). A focus on the feminization of responsibilities and or/obligation would ‘provide a better basis for policy interventions’ (Chant 2016: 115). Focusing on the uneven sense of responsibility provides a better angle on the immaterial, unconscious, superimposed structures that materialize in the actual material inequality. Deconstructing and understanding why women feel a higher sense of responsibility towards nurturing, caring and reproductive roles is perhaps best positioned towards gender equality. By proposing a technological fix, we are overlooking the drivers of gender equality, the overburdening actual and perceived sense of duty towards the wellbeing of a family/household cannot be replaced by technologies and tools.

Discussion and New Horizon for Energy and Gender Studies: What are we Missing?

For the nature of this review, gender equality has been considered almost exclusively in terms of material access to energy and its services. More specifically, the energy development and gender literature focus on the impacts of electricity on empowerment and equal enjoyment of the opportunities created with energy services. In this sense, this review did not focus on the business and policy side of gender equality in the energy sector. That is the case because the literature on the gender gap in businesses and policies has a weaker link to energy per se, looking at energy as a business and key geopolitical sector.

I focused instead on the narratives of international energy development initiatives, and how they refer to energy services as an agent to achieve gender equality. To assess this literature, I used Chant’s critique on the feminization of poverty to flag the similarities in the approaches and solutions between gender and development practitioners and energy and gender research. This article assessed the feminist critique to development, highlighting the unwanted, negative consequences of certain gender and development initiatives such as the exacerbation of women’s responsibilities and the deterioration of gender relations. The article’s framework shows remarkable similarities and repetition in development approaches and ideologies that silence feminist critiques of efficient approaches to gender equality. Moreover, it shows that evidence that energy has a more transformative leverage challenging existing patriarchal ideologies remains thin.

It is important to highlight that while efforts to increase gender equality in energy are desirable, neglecting earlier feminist warnings to development initiatives which dramatically disrupt local social balances, or that use gender as a Trojan Horse for neo-liberal projects, can have some severe consequences on local populations, such as the exacerbation of local conflicts, overburdening of women’s time, and an increasing of social inequalities. The SDG7 and SDG5 should consider critical, postcolonial feminist work on development to avoid the repetition of the same mistakes. Postcolonial feminist approaches can help understand the needs, values and perspectives of local women and men from their cultural point of view, rather than assessing their realities imposing western values of wellbeing and western interpretations of empowerment.

One possible way forward is not only to include feminist, postcolonial critiques into the debate on energy and gender, but also to de-agentify energy access from its role as ‘gender-equality provider’, and re-focus on people as agents for a more equal enjoyment of infrastructure, services, and technologies. The focus therefore should not be about defining ‘progress’ and quantifying men and women’s time and activities as measure for gender equality, but rather focus on the end of all discriminations and lack of opportunities based on gender, sexuality, colour of the skin, age, abilities, ethnicities and so on.

As Chant invites researchers and practitioners to focus on the non-material aspects of gender inequalities, this article also builds on her idea, proposing a non-material angle of gender equality and energy in the private sphere: the invisible element of achieving companionship and support as part of the gender equality discourse. In this sense, this article suggests a shift from a neoliberalist conception of how energy creates gender equality, income, and opportunities, and proposes instead an understanding of the long-term effects and linkages between gender equality, energy development and people’s personal enhancement, based on their needs and aspirations.

When looking at countries with more energy access, more technologies, and more infrastructure, they are still burdened with the plague of patriarchy as the gender pay gap shows. Why should development agencies try to convince people that in order to achieve gender equality they need a Solar PV or an electric stove? This already suggests that the answer for gender equality is not just in equal access to infrastructure, but rather a change of ideology towards a mutual enhancement of capabilities and aspirations. Similarly, gender equality in the public sphere is not just about women in positions of power, but how societies look at leaders with the same respect regardless of their physical appearances, abilities, or gender identity in the long period.

Notes

Term coined by Pierce in 1978.

There are two reasons I italicized the word sacrificing: a) it is a preferred and recurrent term used in energy-gender literature; b) the word ‘sacrificing’ has an implicit subjective value, hence it should be used only when people affected by energy poverty feel they’re sacrificing something based on their systems of value.

Gender roles are defined regarding the division of labour and tasks amongst men and women. The three identified gender roles are: reproductive, productive and community tasks. The first involves all tasks regarding bringing up the next generation and includes childbearing and rearing, feeding the family, caring for the sick and elderly, and teaching acceptable behaviour. The second refers to the work completed for payment in cash or in kind and includes the production of goods and services for subsistence or market purposes. The community tasks role involves the tasks not completed for individual family gain, but for the greater wellbeing of the community or society, such as charitable work, self-help communal construction of village facilities, sitting on village committees, involvement in religious activities and visiting friends who needs help (Moser 1993; Clancy and Roehr 2003).

References

Abdourahman, Omar Ismael. 2017. Time Poverty: A Contributor to Women’s Poverty? Mainstreaming Unpaid Work. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199468256.001.0001.

Afrotechana, Elmahdi Shaza. 2016. Impact of Energy Efficient Projects on Gender-Based Violence in Humanitarian Emergencies. Journal of Women’s Health. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2016.29006.abstracts.

Alston, Margaret. 2014. Gender mainstreaming and climate change. Women’s Studies International Forum 47 (Part B): 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2013.01.016.

Amegah, Adeladza Kofi, and Jouni J.K.. Jaakkola. 2016. Household air pollution and the sustainable development goals. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 94 (3): 215–221. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.15.155812.

Anenberg, Susan C., Daven K. Henze, Forrest Lacey, Ans Irfan, Patrick Kinney, Gary Kleiman, and Ajay Pillarisetti. 2017. Air pollution-related health and climate benefits of clean cookstove programs in Mozambique. Environmental Research Letters. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa5557.

Arora, Diksha. 2013. Gender Differences in Time Poverty in Rural Mozambique. Review of Social Economy 73 (2): 196–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2015.1035909.

Asian Development Bank. 2015. Women in the Workforce: An Unmet Potential in Asia and the Pacific Manila. Philippines: Asian Development Bank.

Bhattasali, Amitabha. 2005. A silent killer of rural women, BBC News, 2 March.

Bailis, Rob, Amanda Cowan, Victor Berrueta, and Omar Masera. 2009. Arresting the Killer in the Kitchen: The Promises and Pitfalls of Commercializing Improved Cookstoves. World Development 37 (10): 1694–1705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.03.004.

Bell, Shannon Elizabeth, Cara Daggett, and Christine Labuskic. 2020. Toward feminist energy systems: Why adding women and solar panels is not enough. Energy Research & Social Science 68: 101557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101557.

Blackden, C. Mark, and Quentin Wodon (eds.). 2006. Gender, Time Use, and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: Foreword, World Bank Working Paper No. 73. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Calkin, Sydney. 2015. Feminism, interrupted? Gender and development in the era of ‘Smart Economics.’ Progress in Development Studies 15 (4): 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464993415592737.

Cannon, Clare E. B., and Eric K. Chu. 2021. Gender, sexuality, and feminist critiques in energy research: A review and call for transversal thinking, Energy Research & Social Science, 75. Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102005.

Cecelski, Elizabeth. 2002. Enabling Equitable Access to Rural Electrification: Current Thinking on Energy, Poverty and Gender, ENERGIA, Briefing Paper.

Cecelski, Elizabeth. 2000. The Role of Women in Sustainable Energy Development. National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Cecelski, Elizabeth W. 1995. From Rio to Beijing. Engendering the Energy Debate. Energy Policy 23 (6): 561–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-4215(95)91241-4.

Chant, Sylvia. 2016. Women, girls and world poverty: Empowerment, equality or essentialism? International Development Planning Review 38 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2016.1.

Chant, Sylvia. 2014. Exploring the “feminisation of poverty” in relation to women’s work and home-based enterprise in slums of the Global South. International Journal of Gender Entrepreneurship. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-09-2012-0035.

Chant, Sylvia. 2013. Cities through a ‘gender lens’: A golden ‘urban age’ for women in the global South? Environment and Urbanization. 25 (1): 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247813477809.

Chant, Sylvia. 2008. The ‘Feminisation of Poverty’ and the ‘Feminisation’ of Anti-Poverty Programmes: Room for Revision? Journal of Development Studies 44 (2): 165–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380701789810.

Chant, Sylvia. 2007. Gender, Generation and Poverty: Exploring the ‘feminisation of poverty’ in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Chant, Sylvia. 2006. Re-thinking the ‘Feminization of Poverty’ in Relation to Aggregate Gender Indices. Journal of Human Development 7 (2): 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880600768538.

Chant, Sylvia. 1998. Households, gender and rural-urban migration: Reflections on linkages and considerations for policy. Environment and Urbanization 10 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624789801000117.

Chant, Sylvia, and Caroline Sweetman. 2012. Fixing women or fixing the world? ‘Smart economics’, efficiency approaches, and gender equality in development. Gender and Devevelopment 20 (3): 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2012.731812.

Chikulo, B.C. 2014. Gender Climate Change and Energy in South Africa: A Review. Gender and Behaviour 12 (3): 5957–5970.

Chynoweth, Sarah, and Erin M. Patrick. 2007 Sexual violence during firewood collection: income-generation as protection in displaced settings. In: Geraldine Terry (eds) Gender-Based Violence. Oxfam GB: 43–55, Oxford

Clancy, Joy S., N. Dutta, Nthabiseng Mohlakoana, A.V. Rojas, and Margaret Njirambo Matinga. 2015. The predicament of women. In International Energy and Poverty: The Emerging Contours, ed. Lakshman Guruswamy. NY: Routledge.

Clancy, Joy S., Tanja Winther, Margaret Njirambo Matinga, and Sheila Oparaocha, 2012. Gender Equity In Access To And Benefits From Modern Energy And Improved Energy Technologies: World Development Report Background Paper. ETC/ENERGIA in association Nord/Sør-konsulentene.

Clancy, Joy, Fareeha Ummar, Indira Shakya, and Govind Kelkar. 2007. Appropriate gender-analysis tools for unpacking the gender-energy-poverty nexus. Gender and Development 15 (2): 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070701391102.

Clancy, Joy, and Ulrike Roehr. 2003. Gender and energy: is there a Northern perspective? Energy for Sustainable Development 7 (3): 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0973-0826(08)60364-6.

Cornwall, Andrea, and Althea-Maria. Rivas. 2015. From ‘gender equality and women’s empowerment’ to global justice: Reclaiming a transformative agenda for gender and development. Third World Quarterly 36 (2): 396–415.

Cornwall, Andrea, Jasmine Gideon, and Kalpana Wilson. 2008. Introduction: Reclaiming Feminism: Gender and Neoliberalism. IDS Bulletin 39 (6): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2008.tb00505.x.

Costa, Joana, Degol Hailu, Elydia Silva, and Raquel Tsukada. 2009. The Implications of Water and Electricity Supply for the Time Allocation of Women in Rural Ghana, International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (59): 1–27.

Coulter, Kendra. 2009. Women, Poverty Policy, and the Production of Neoliberal Politics in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 30 (1): 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/15544770802367788.

Duflo, Esther. 2012. Women empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature 50 (4): 1051–1079. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.4.1051.

Dutta, Soma, Annemarije Kooijman, and Elizabeth W. Cecelski. 2017. Energy Access and Gender: Getting the Right Balance, ENERGIA, International Network on Gender and Sustainable Energy, Washington, DC: World Bank, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/463071494925985630/pdf/115066-BRI-P148200-PUBLIC-FINALSEARSFGenderweb.pdf

ENERGIA, 2019. Gender in the transition to sustainable energy for all: From evidence to inclusive policies, ENERGIA International Network on Gender and Sustainable Energy.

FAO, 2011. WOMEN IN AGRICULTURE: Closing the gender gap for development, https://www.fao.org/publications/sofa/2010-11/en/

Fathallah, Judith, and Parakram Pyakurel. 2020. Addressing gender in energy studies. Energy Research and Social Science https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101461.

Feenstra, Mariëlle, and Gül. Özerol. 2021. Energy justice as a search light for gender-energy nexus: Towards a conceptual framework. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110668.

Garikipati, Supriya. 2012. Microcredit and Women’s Empowerment: Through the Lens of Time-Use Data from Rural India. Development and Change 43 (3): 719–750. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2012.01780.x.

Gray, Leslie, Alaina Boyle, Erika Francks, and Yu. Victoria. 2019. The power of small-scale solar: Gender, energy poverty, and entrepreneurship in Tanzania. Development in Practice 29 (1): 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2018.1526257.

Habtezion, Senay. 2012. Gender and energy, United Nations Development Program, http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/gender/Gender%20and%20Environment/PB3_Africa_Gender-and-Energy.pdf

Jackson, Cecile. 1998. Gender, irrigation, and environment: Arguing for agency. Agriculture and Human Values 15: 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007528817346.

Jackson, Cecile. 1996. Rescuing Gender from the Poverty Trap. World Development 24 (3): 489–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(95)00150-B.

Jagoe, Kirstie, Madeleine Rossanese, Dana Charron, Jonathan Rouse, Francis Waweru, Mary Anne Waruguru, Samantha Delapena, Ricardo Piedrahita, Kavanaugh Livingston, and Julie Ipe. 2020. Sharing the burden: Shifts in family time use, agency and gender dynamics after introduction of new cookstoves in rural Kenya. Energy Research & Social Science 64: 101413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101413.

Kalpana, K. 2005. Shifting Trajectories in Microfinance Discourse, Economic and Political Weekly, 40(51), 17 December, https://www.epw.in/journal/2005/51/special-articles/shifting-trajectories-microfinance-discourse.html

Kes, Aslihan and Hema Swaminathan. 2006. Gender and time poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa, World Bank Working Paper.

Khosla, Radhika, Nicole D. Miranda, Philipp A. Trotter, Antonella Mazzone, Renaldi Renaldi, Caitlin McElroy, Francois Cohen, Anant Jani, Rafael Perera-Salazar, and Malcolm McCulloch. 2021. Cooling for sustainable development. Nature Sustainability 4 (3): 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00627-w.

Kim, Elena, and Karina Standal. 2019. Empowered by electricity? The Political Economy of Gender and Energy in Rural Naryn. Gender, Technology and Development 23 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2019.1596558.

Köhlin, Gunnar, Erin O. Sills, Subhrendu K. Pattanayak, and Christopher Wilfong. 2011. Energy, Gender and Development. What are the Linkages? Where is the Evidence? Policy Research working paper; no. WPS 5800. World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/3564 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

Levtov, Ruti Galia, Gary Barker, Manuel Contreras-Urbina, Brian Heilman, and Ravi Verma. 2014. Pathways to Gender-equitable Men: Findings from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey in Eight Countries. Men and Masculinities 17 (5): 467–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X14558234.

Listo, Romy. 2018. Gender myths in energy poverty literature: A Critical Discourse Analysis. Energy Research & Social Science 38: 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.01.010.

Mahat, Ishara. 2004. Implementation of alternative energy technologies in Nepal: Towards the achievement of sustainable livelihoods. Energy for Sustainable Development 8 (2): 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0973-0826(08)60455-X.

Matinga, Margaret Njirambo, and Harold J. Annegarn. 2013. Paradoxical impacts of electricity on life in a rural South African village. Energy Policy 58: 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.03.016.

Mayoux, Linda. 2001. Tackling the Down Side: Social Capital, Women’s Empowerment and Micro-finance in Cameroon. Development and Change 32 (3): 435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00212.

Mininni, Giulia M. 2021. The Barefoot College ‘eco-village’ approach to women’s entrepreneurship in energy. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 42: 112–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.12.002.

Molyneux, Maxine. 2006. Mothers at the Service of the New Poverty Agenda: Progresa/Oportunidades, Mexico’s Conditional Transfer Programme. Social Policy Administration 40 (4): 425–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2006.00497.x.

Moser, Caroline O. N. 1993. Gender Planning and Development: Theory. Practice and Training, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.2307/1395333.

Niethammer, Carmen, and Peter Alstone. 2012. Expanding women’s role in Africa’s modern off-grid lighting market: Enhancing profitability and improving lives. Gender and Development 20 (1): 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2012.663611.

Oparaocha, Sheila, and Soma Dutta. 2011. Gender and energy for sustainable development. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 3 (4): 265–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2011.07.003.

Panjwani, Anja. 2005. Energy as a key variable in promoting gender equality and empowering women: A gender and energy perspective on MDG # 3, 1–47.

Patrick, Erin. 2007. Sexual violence and firewood collection in Darfur. Forced Migration Review 27: 40–41.

Pereira, Marcio Giannini, José Antonio. Sena, Marcos Aurélio Vasconcelos. Freitas, and Neilton Fidelis Da. Silva. 2011. Evaluation of the impact of access to electricity: A comparative analysis of South Africa China, India and Brazil. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 15 (3): 1427–1441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2010.11.005.

Pueyo, Ana, Marco Carreras, and Gisela Ngoo. 2020. Exploring the linkages between energy, gender, and enterprise: Evidence from Tanzania. World Development 128: 104840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104840.

Pueyo, Ana, and Mar Maestre. 2019. Linking energy access, gender and poverty: A review of the literature on productive uses of energy. Energy Research & Social Science 53: 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.02.019.

Rosenthal, Joshua, Ashlinn Quinn, Andrew P. Grieshop, Ajay Pillarisetti, and Roger I. Glass. 2018. Clean cooking and the SDGs: Integrated analytical approaches to guide energy interventions for health and environment goals. Energy for Sustainable Development 42: 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2017.11.003.

Sánchez, Sánchez-Guevara., Ana Sanz Fernández, and Miguel Núñez. Peiró. 2020. Feminisation of energy poverty in the city of Madrid. Energy and Buildings https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110157.

Scott, Joan Wallach. 1986. Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis, The American Historical Review, 91(5): 1053–1075, December, Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association Stable.

Sengendo, May. 2005. Institutional and Gender Dimensions of Energy Service Provision for Empowering the Rural Poor in Uganda. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08c8be5274a31e00012a8/R8346_finrep_sengendo.pdf

Sengupta, Nilanjana. 2013. Poor Women’s Empowerment: The Discursive Space of Microfinance. Indian Journal of Gender Studies 20 (2): 279–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971521513482220.

Silberschmidt, Margrethe. 2001. Disempowerment of Men in Rural and Urban East Africa: Implications for Male Identity and Sexual Behavior. World Devevelopment 29 (4): 657–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00122-4.

Skutsch, Margaret M. 2005. Gender analysis for energy projects and programmes. Energy for Sustainable Development 9 (1): 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0973-0826(08)60481-0.

Skutsch, Margaret M. 1998. The gender issue in energy project planning Welfare, empowerment or efficiency? Energy Policy 26 (12): 945–955. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(98)00037-8.

Sovacool, Benjamin K. 2012. The political economy of energy poverty: A review of key challenges. Energy for Sustainable Development 16 (3): 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2012.05.006.

Sovacool, Benjamin K., and Michael H. Dworkin. 2015. Energy justice: Conceptual insights and practical applications. Applied Energy 142: 435–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.01.002.

Sovacool, Benjamin K., Shannon Clarke, Katie Johnson, Meredith Crafton, and Jay Eidsness. 2013. and David Zoppo. Renewable Energy 50: 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2012.06.024.

Standal, Karina, and Tanya Winther. 2016. Empowerment Through Energy? Forum for Development Studies 43 (1): 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2015.1134642.

Sunikka-Blank, Minna, Ronita Bardhan, and Anika Nasra Haque. 2018. Gender, domestic energy and design of inclusive low-income habitats: A case of slum rehabilitation housing in Mumbai India. Energy Research & Social Science 49: 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.10.020.

Ukanwa, Irene, Lin Xiong, and Alistair Anderson. 2018. Experiencing microfinance: Effects on poor women entrepreneurs’ livelihood strategies’. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-02-2017-0043.

UN. 1995. United Nations Report of the Fourth World Conference on Women, September.

UNDP. 2011. Gender and Climate change. Africa. Policy Brief 3. https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/gender/Gender%20and%20Environment/PB3_Africa_Gender-and-Energy.pdf

UNEP. 2016. Environmentally-friendly stoves reduce risk of sexual assault, UN Environment, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/environmentally-friendly-stoves-reduce-risk-sexual-assault

Victor, Britta. 2011. Sustaining Culture with Sustainable Stoves: The Role of Tradition in Providing Clean-Burning Stoves to Developing Countries. Consilience: the Journal of Sustainable Development 5 (5): 71–95. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8R49QF5.

Wilhite, Harold. 2013. Energy Consumption as Cultural Practice: Implications for the Theory and Policy of Sustainable Energy Use. In Cultures of Energy: Power, Practices, Technology, ed. Sarah Strauss, Stephanie Rupp, and Thomas Love. Left Coast Press.

Wilson, Kalpana. 2011. Race. Third World Quarterly 32 (2): 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2011.560471.

Winther, Tanja, Kirsten Ulsrud, Margaret Matinga, Mini Govindan, Bigsna Gill, Anjali Saini, Deborshi Brahmachari, Debajit Palit, and Rashmi Murali. 2019. In the light of what we cannot see: Exploring the interconnections between gender and electricity access. Energy Research & Social Science 60: 101334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101334.

Winther, Tanja, Kirsten Ulsrud, and Anjali Saini. 2018. Solar powered electricity access: Implications for women’s empowerment in rural Kenya. Energy Research & Social Science 44: 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.04.017.

Winther, Tanja, Margaret N. Matinga, Kirsten Ulsrud, and Karina Standal. 2017. Women’s empowerment through electricity access: Scoping study and proposal for a framework of analysis. Journal of Development Effectivenss 9 (3): 389–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2017.1343368.

World Health Organization. 2016. Household air pollution and health. WHO media Cent: Public Health and environment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mazzone, A. Gender and Energy in International Development: Is There a Return of the ‘Feminization’ of Poverty Discourse?. Development 65, 17–28 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-022-00330-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-022-00330-7