Abstract

There is evidence to suggest that law enforcement data are a valid and reliable source for firearm violence data. Data for this exploratory study come from law enforcement sources in a large Midwestern city and include all unintentional nonfatal shooting incidents (n = 177) occurring in between 2017 and 2019. Incidents most commonly occurred in the fall season, during nighttime hours, and at a residence. Victims were more likely to be male, Black, Indigenous, or People of Color, and 18–34 years old. Their injuries resulted from improper firearm handling. Most victims were wounded in their extremities and did not engage emergency medical/ambulance services before seeking medical care. This study demonstrates the utility of law enforcement data as a source for additional context surrounding unintentional nonfatal shooting incidents. Findings suggest two policy implications: requiring a gun safety course as part of the permitting process and treating gun safety as a life skill by advocating for gun safety courses in schools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Current and available gun violence data are severely limited despite the ubiquitous presence of gun violence across American cities. The most accurate and reliable data pertain to fatal firearm injuries despite the fact that nonfatal firearm injuries occur at a much higher rate than fatal gun injuries (Gani et al. 2017; Hipple et al. 2020; Hipple and Magee 2017). Limitations in data availability and quality are common in the United States (U.S.) because there is no standardized comprehensive injury surveillance system nationwide (Annest and Mercy 1998; Hink et al. 2019). Instead, data are collected by different government agencies in different formats (Roman 2020). Research, therefore, has focused on fatal firearm incidents and there are less epidemiologic data available that describe the criminological and public health characteristics of nonfatal unintentional firearm injuries in the U.S. (Frattaroli et al. 2002; Grommon and Rydberg 2015; Kalesan et al. 2017; Webster et al. 2016).

Demographic characteristics among firearm injury victims are relatively consistent in the published research. Researchers have found that most firearm injury victims are Black, male, and aged 35 years or younger (Hipple et al. 2019, 2020; Hipple and Magee 2017; Kalesan et al. 2017; Coupet et al. 2019; Fowler et al. 2015; Manley et al. 2018; Reynolds 2021; de Anda et al. 2018). While researchers have found similar demography when focusing on unintentional injuries, these findings are not consistent, partially due to a lack of a national definition for a nonfatal shooting incident (Hipple et al. 2019, 2020; Hipple and Magee 2017; Reynolds 2021; Huebner and Hipple 2018). Without a national definition or an official data source for nonfatal shooting incidents, jurisdictions are left to develop one themselves, which creates validity and reliability issues when trying to compare data over time (i.e., intraagency) as well as across jurisdictions (i.e., interagency) (Hipple 2022).

According to Kellermann et al. (1996), the three circumstances under which firearm injuries generally occur involve interpersonal violence, suicidal behavior, and unintentional weapon discharges. Criminological research predominantly focuses on interpersonal firearm violence, specifically homicide, because these incidents are most likely to come to the attention of law enforcement, increasing the reliability and validity of the measures (National Research Council 2005; Black 1980; Jackson 1990). This focus is despite the fact that homicides are rare events and capture only a small proportion of all criminal firearm violence (Piquero et al. 2005; Pridemore 2005). Suicide and unintentional shootings, while still documented by law enforcement in most states (Victim Rights Law Center 2014), do not illicit a formal response from the criminal justice system because they are not inherently criminal. These facts contribute to the dearth of detailed empirical work on the incident and victim characteristics of unintentional shootings.

Finally, the majority of available firearm violence data are summary data and lack sufficient detail to inform policy and practice. For example, information about where a firearm injury occurred is commonly missing from national data sources (Parker 2020). There is, however, evidence to suggest that law enforcement data are valid and reliable sources for firearm violence information (Kaufman et al. 2020; Magee et al. 2021; Post et al. 2019). This exploratory study uses law enforcement data to examine unintentional nonfatal shooting incidents and victims in a large Midwestern city. We describe incident characteristics including location, time of day, and time of year. We also describe victim demographic characteristics, injury severity, hospital transport method, as well as the shooter’s actions contributing to the firearm injury.

Methods

The site

Indianapolis, Indiana is the 16th largest city in the U.S. It spans roughly 400 square miles and had an estimated population of 887,000 in 2020. Like many cities in the U.S., Indianapolis continues to experience high rates of criminal gun violence (Rosenfeld and Lopez 2020). In 2020, there were 14 gun deaths per 100,000 population—the 20th highest rate in the U.S., making Indianapolis an appropriate site for this study. The majority of Indianapolis and its encompassing county (Marion) are served by the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department (IMPD).The IMPD is the largest law enforcement agency in the state of Indiana.

By definition, unintentional shootings are not crimes; however, most states, including Indiana, require medical personnel to notify local law enforcement about a firearm injury regardless of the incident context (Indiana Code 35-47-7-1) (Victim Rights Law Center 2014). Local law enforcement must document the injury and the circumstances surrounding it in an incident report. In Indiana, firearm injuries most commonly come to the attention of law enforcement in two ways: a community member requests emergency/ambulance services (e.g., calls or texts 911) or a healthcare worker notifies law enforcement when someone has presented in the emergency department with a firearm injury. Data for this study were collected from internal police documents created by an investigating detective within 24 h of when a firearm injury was brought to the attention of law enforcement. Patients were not involved in this study. The University of Indianapolis Human Research Protections Program determined the study was exempt from institutional review board review because the researchers were provided de-identified data.

The IMPD dispatches an Aggravated Assault detective to each nonfatal shooting incident scene to investigate the incident once the reporting officer confirms a firearm injury. As part of this process, the detective attempts to conduct an initial interview with the victim, most commonly at the emergency department. Departmental procedure dictates that detectives draft an internal summary document within 24 h of the incident, which includes additional information gathered after the responding officer completed the initial police incident report. Data for this study come from these internal documents.

There is no national definition of a nonfatal shooting incident or victim. For this study, a shooting victim is defined as an individual with a penetrating wound caused by a projectile from a weapon that uses a powder charge (Hipple and Magee 2017; Hipple et al. 2019; Huebner and Hipple 2018). To be included in the study, the nonfatal shooting incident had to occur between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2019 and include at least one surviving unintentional nonfatal shooting victim. An unintentional shooting incident is one that does not occur during an aggravated assault and lacks the intent of one person to cause harm to another person, including harm to oneself. Both the UCR and the NIBRS define an aggravated assault “as an unlawful attack by one person upon another for the purpose of inflicting severe or aggravated bodily injury” (Federal Bureau of Investgation 2013a, b). Because suicide attempts involve the intent to harm oneself and self-defense shootings include the intent to cause harm to another person for protection by the shooter, they were excluded from the study. Additionally, incidents where intent could not be determined were and incidents where the victim was injured by a weapon not meeting the federal definition of a firearm such as a BB gun or flare gun were also excluded. Table 1 displays different shooting scenarios and the reasons for their inclusion or exclusion in this study. The violent nature of firearm injuries and the fact that the majority require medical care, along with Indiana’s mandatory reporting law, led authors to believe these data likely represent close to the population of unintentional shooting incidents and victims in Indianapolis for the study period (Magee et al. 2021).

Data

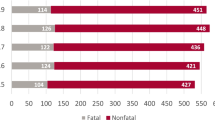

The sample included 177 incidents identified during the 3-year study period that met our definition of an unintentional shooting incident. One incident had two victims therefore our sample includes 178 victims. The majority of variables were police officer-coded at the time of the incident. We began with incident-level variables. Using the incident date, we determined the time of year or season according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2016) definitions (Spring: March, April, May; Summer: June, July, August; Fall: September, October, November; Winter: December, January, February). The time the incident occurred was categorized according to the time of day approximately representing school/work hours (0800–1559 h), after school/work hours (1600–1159 h), and nighttime hours (0000–0759 h). The location of the incident was categorized as business, public street/alley, inside a residence, outside a residence, in a vehicle, other, and unknown.

Victim-level variables included age at the time of the incident, victim race (BIPOC,Footnote 1 white), sex (male, female), and number of gunshot wounds (single, multiple). We captured the location/severity of victims’ injuries using a modified version of the 1990 Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) (Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine 1990; Hipple et al. 2019). This variable was coded based on the detective's observation; we did not have access to medical data. We first captured the body part affected and then recoded to less severe/extremities and more severe/center mass (Less severe/extremities [wrist, ankle, hand, foot, arm, leg]; more severe/center mass [back, hip, buttocks, genitals/pubic area, abdomen, head, neck, chest]). When a victim had more than one gunshot injury, the AIS score was recorded for the most serious injury. Victim injury location/severity was categorized as unknown if there was no wound location documented in the data source.

We captured how the victim traveled to the emergency department (ambulance, self-transport, unknown). Self-transport included the victim driving themselves, walking, or if they were transported by another person. We also captured whether or not the gunshot wound was self-inflicted (no, yes, unknown). Finally, we captured the shooter’s actions immediately preceding the injury. Actions included: maintenance, handling, showing off, storage, and unknown. See Table 2 for detailed descriptions of the actions included in these categories and examples of each.

Results

There were 177 unintentional nonfatal shooting incidents during the study period. Only one unintentional incident had two victims. In this incident, the bullet traveled through the shooter hitting the second person. Table 3 displays the incident characteristics. The majority of incidents (55.3%) occurred during the fall and winter months and almost half (47.5%) occurred during nighttime hours, after midnight but before 8 AM. A residence, inside or outside, was the location of just more than half (51.9%) of unintentional incidents. The location of the incident was unknown 20% of the time.

Table 4 displays the characteristics of the 178 unintentional nonfatal shooting victims. Victim age ranged from 2 to 85 years with a mean age of 29.6 years and a standard deviation of 14.9 years. Most victims were male, BIPOC, and between the ages of 18 and 34 years. These findings align with previous research regarding victim age, gender, and race (Kalesan et al. 2017), although BIPOC are still overrepresented as unintentional shooting victims compared to the national and local populations. Most unintentional victims suffered from a single, self-inflicted gunshot wound. Multiple gunshot wounds were the result of the bullet entering and exiting multiple body parts. Eighty-five percent of unintentional shooting victims suffered less severe injuries to their extremities. Unintentional shooting victims were more likely to arrive at an emergency department by non-emergency mode rather than by ambulance, meaning they did not engage services via 911 or by flagging down a police officer. While the exact circumstances of the unintentional nonfatal shooting were unknown for one-fifth of the sample, when known, unintentional shootings occurred most often due to general handling mishaps unrelated to cleaning (28.7%) followed closely by unintentional shootings during cleaning or maintenance of the firearm.

Discussion and implications

This study demonstrates the utility of law enforcement data in examining unintentional nonfatal shooting incidents and victims by providing additional qualitative context not traditionally captured or available in public health and medical data sources. Importantly, this research illuminates the shooter’s actions immediately preceding the unintentional shooting. What is particularly noteworthy is the finding that the majority, nearly 29%, of unintentional nonfatal shooting incidents occurred during simple handling or routine maintenance of the firearm. There is existing work with similar findings but it is dated, limited to firearm deaths, or both (Cherry et al. 2001; Grossman et al. 1999; Lee and Harris 1993). Similarly, the geographic location of unintentional nonfatal shooting incidents is not captured well in available public health and medical data sources (Frattaroli et al. 2002; Cherry et al. 2001). These findings suggest that over one-half (51.9%) of unintentional nonfatal shootings are likely to occur in someone’s home.

The quantitative findings contribute to the current body of knowledge regarding accidental shooting incident and victim characteristics—aligning with some findings such as the modal age, race, and gender of unintentional shooting victims (Kalesan et al. 2017; Fowler et al. 2015; Kongkaewpaisan et al. 2020) and wound location (Coupet et al. 2019; Kongkaewpaisan et al. 2020; Mills et al. 2018), but countering existing work that examines victims’ mode of transport to a medical facility.

Indiana is a gun-friendly state with weak gun control laws (Giffords Law Center). There is no permit required to purchase a firearm and no firearm registration requirement. A constitutional carry law went into effect on July 1, 2022 (Indiana Code 35-47-2-3) eliminating the permit requirement to carry a handgun in Indiana. Federal purchasing laws still apply, however, there is no firearm safety training requirement at the state or federal levels.

Indiana law requires all persons born on or after January 1, 1987 to successfully complete a hunter’s education course offered by or through the Department of Natural Resources to obtain a hunting license (Indiana Code 14-22-11-5). It is an online course (https://www.hunter-ed.com/indiana/studyGuide/20101601/) for individuals ages 12 and older which could easily be adapted to include firearm safety training. Additionally, policymakers should consider a required gun safety course as part of the purchasing process or permitting process if ever reinstated. This requirement would not change the status of Indiana as a gun-friendly state but has the possibility to drastically reduce the number of unintentional nonfatal firearm injuries across the state.

Second, almost 15% (n = 25) of victims in our sample are under the age of 18 and therefore could not legally possess a firearm in the state of Indiana. Yet, these data show that children can and do have access to guns and that these accidents happen in homes. The majority of unintentional nonfatal injuries in this age group (40%) resulted from playing with the firearm. Policymakers should consider including gun safety in school curriculum alongside other important personal health and life skill topics taught in schools. Gun safety should be considered a life skill in the U.S.

Finally, a noteworthy finding is that more than one-half of unintentional nonfatal shooting victims did not engage public safety or emergency/ambulance services when seeking medical attention. Instead, they chose to find another way to travel to the emergency department. This finding is counter to previous work using the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System that indicated roughly 68% of nonfatal firearm injury victims who presented at an emergency department from 2010 to 2012 were transported by emergency medical services or an ambulance (Fowler et al. 2015). The proportion using emergency medical/ambulance services is even greater for firearm assault victims (Manley et al. 2018). Grommon and Rydberg (2015) found similar results in their examination of nonfatal firearm injury data although this variable was missing in a lot of their records. Relatedly, the incident location (n = 36) and the shooter’s actions (n = 37) were each unknown 20% of the time, which suggests victims were not forthcoming with the detective about what happened. Without direct victim input, it is impossible to know exactly what is driving this decision to not engage public safety services. Research shows that victims of sexual assault and criminal nonfatal shootings are often reluctant to engage with law enforcement (Hipple et al. 2019; O’neal 2017; Kaiser et al. 2017). This topic is important for future research especially when trying to use data to drive policy and practice.

This study is limited in that it is a single, urban site that uses law enforcement data. The internal police documents used as the data source were not designed for research purposes and reflect the police perspective (Alison et al. 2001); therefore, these results should be interpreted with that in mind. Additionally, the data reflect information known to police within the first 24 h of the incident and the authors did not have access to updated case information. Due to the urban study setting, these findings lack any information on hunting-related firearm injuries. Future research should examine similar data in additional urban and rural locations as well as work to include the victim’s perspective.

Conclusion

One in 90 people in Indiana are expected to die from a firearm injury in their lifetime. This risk is greater than the national expectation of one death by firearm in every 108 people (Sehgal 2020). It is important to work towards developing comprehensive data about firearm injuries, especially nonfatal shootings. Continued research and surveillance using both public health and law enforcement data will provide a stronger understanding of unintentional nonfatal shooting victims and incidents that will further inform prevention and intervention efforts to decrease morbidity and mortality.

Notes

Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

References

Alison, L.J., B. Snook, and K.L. Stein. 2001. Unobtrusive Measurement: Using Police Information for Forensic Research. Qualitative Research 1(2): 241–254.

Annest, J.L., and J.A. Mercy. 1998. Use of National Data Systems for Firearm-Related Injury Surveillance. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 15(3 Suppl. 1): 17–30.

Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine. 1990. The Abbreviated Injury Scale 1990 Revision. Des Plaines, IL: Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine.

Black, D.J. 1980. Production of Crime Rates. In The Manners and Customs of the Police, ed. D.J. Black. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Cherry, D., C. Runyan, and J.A. Butts. 2001. A Population Based Study of Unintentional Firearm Fatalities. Injury Prevention 7(1): 62–65.

Coupet, E., Jr., Y. Huang, and M.K. Delgado. 2019. Us Emergency Department Encounters for Firearm Injuries According to Presentation at Trauma Vs Nontrauma Centers. JAMA Surgery 154(4): 360–362.

De Anda, H., T. Dibble, C. Schlaepfer, R. Foraker, and K. Mueller. 2018. A Cross-Sectional Study of Firearm Injuries in Emergency Department Patients. Missouri Medicine 115(5): 456–462.

Fowler, K.A., L.L. Dahlberg, T. Haileyesus, and J.L. Annest. 2015. Firearm Injuries in the United States. Preventive Medicine 79: 5–14.

Frattaroli, S., D.W. Webster, and S.P. Teret. 2002. Unintentional Gun Injuries, Firearm Design, and Prevention: What We Know, What We Need to Know, and What Can Be Done. Journal of Urban Health 79(1): 49–59.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2013a. Criminal Justice Information Services (Cjis). Division uniform crime reporting program (Ucr) [Online]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. Available: https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/nibrs/summaryreporting-system-srs-user-manual

Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2013b. Crime in the United States, 2012: Aggravated Assault [Online]. Washington, DC United States Department of Justice. Available: https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2012/crime-in-the-u.s.-2012/violent-crime/aggravated-assault

Gani, F., J.V. Sakran, and J.K. Canne. 2017. Emergency Department Visits for Firearm-Related Injuries in the United States, 2006–14. Health Affairs 36(10): 1729–1738.

Giffords Law Center. Annual Gun Law Scorecard [Online]. Available: https://giffords.org/lawcenter/resources/scorecard/#IN.

Grommon, E., and J. Rydberg. 2015. Elaborating the Correlates of Firearm Injury Severity: Combining Criminological and Public Health Concerns. Victims & Offenders 10(3): 318–340.

Grossman, D.C., D.T. Reay, and S.A. Baker. 1999. Self-Inflicted and Unintentional Firearm Injuries among Children and Adolescents: The Source of the Firearm. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 153(8): 875–878.

Hink, A.B., S. Bonne, M. Levy, D.A. Kuhls, L. Allee, P.A. Burke, J.V. Sakran, E.M. Bulger, and R.M. Stewart. 2019. Firearm Injury Research and Epidemiology: A Review of the Data, Their Limitations, and How Trauma Centers Can Improve Firearm Injury Research. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 87(3): 678–689.

Hipple, N.K. 2022. Towards a National Definition and Database for Nonfatal Shooting Incidents. Journal of Urban Health 99(3): 361–372.

Hipple, N.K., B.M. Huebner, T.S. Lentz, E.F. Mcgarrell, and M. O’brien. 2020. The Case for Studying Criminal Nonfatal Shootings: Evidence from Four Midwest Cities. Justice Evaluation Journal 3(1): 94–113.

Hipple, N.K., and L.A. Magee. 2017. The Difference between Living and Dying: Victim Characteristics and Motive among Nonfatal Shooting and Gun Homicides. Violence and Victims 32(6): 977–997.

Hipple, N.K., K.J. Thompson, B.M. Huebner, and L.A. Magee. 2019. Understanding Victim Cooperation in Cases of Nonfatal Gun Assaults. Criminal Justice and Behavior 46(12): 1793–1811.

Huebner, B.M., and N.K. Hipple. 2018. A Nonfatal Shooting Primer. Washington, DC: Police Foundation.

Jackson, P.G. 1990. Sources of Data. In Measurement Issues in Criminology, ed. K. Kempf. New York, NY: Springer Publications.

Kaiser, K.A., E.N. O’neal, and C. Spohn. 2017. “Victim Refuses to Cooperate”: A Focal Concerns Analysis of Victim Cooperation in Sexual Assault Cases. Victims & Offenders 2: 297–322.

Kalesan, B., C. Adhikarla, J.C. Pressley, J.A. Fagan, Z. Xuan, M.B. Siegel, and S. Galea. 2017. The Hidden Epidemic of Firearm Injury: Increasing Firearm Injury Rates During 2001–2013. American Journal of Epidemiology 185(7): 546–553.

Kaufman, E.J., J.E. Passman, S.F. Jacoby, D.N. Holena, M.J. Seamon, J. Macmillan, and J.H. Beard. 2020. Making the News: Victim Characteristics Associated with Media Reporting on Firearm Injury. Preventive Medicine 141: 106275.

Kellermann, A.L., F.P. Rivara, R.K. Lee, J.G. Banton, P. Cummings, B.B. Hackman, and G. Somes. 1996. Injuries Due to Firearms in Three Cities. New England Journal of Medicine 335(19): 1438–1444.

Kongkaewpaisan, N., M. El Hechi, M. El Moheb, C.P. Orlas, G. Ortega, M.A. Mendoza, J. Parks, N.N. Saillant, H.M.A. Kaafarani, and A.E. Mendoza. 2020. No Place Like Home: A National Study on Firearm-Related Injuries in the American Household. The American Journal of Surgery 220(6): 1599–1604.

Lee, R.K., and M.J. Harris. 1993. Unintentional Firearm Injuries: The Price of Protection. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 9(3): 16–20.

Magee, L.A., M.L. Ranney, J.D. Fortenberry, M. Rosenman, S. Gharbi, and S.E. Wiehe. 2021. Identifying Nonfatal Firearm Assault Incidents through Linking Police Data and Clinical Records: Cohort Study in Indianapolis, Indiana, 2007–2016. Preventive Medicine 149: 106605.

Manley, N.R., T.C. Fabian, J.P. Sharpe, L.J. Magnotti, and M.A. Croce. 2018. Good News, Bad News: An Analysis of 11,294 Gunshot Wounds (Gsws) over Two Decades in a Single Center. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 84(1): 58–65.

Mills, B.M., P.S. Nurius, R.L. Matsueda, F.P. Rivara, and A. Rowhani-Rahbar. 2018. Prior Arrest, Substance Use, Mental Disorder, and Intent-Specific Firearm Injury. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 55(3): 298–307.

National Research Council. 2005. Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

O’neal, E.N. 2017. Victim Cooperation in Intimate Partner Sexual Assault Cases: A Mixed Methods Examination. Justice Quarterly 34(6): 1014–1043.

Parker, S.T. 2020. Estimating Nonfatal Gunshot Injury Locations with Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning Models. JAMA Network Open 3(10): e2020664–e2020664.

Piquero, A.R., J. Macdonald, A. Dobrin, L.E. Daigle, and F.T. Cullen. 2005. Self-Control, Violent Offending, and Homicide Victimization: Assessing the General Theory of Crime. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 21(1): 55–71.

Post, L.A., Z. Balsen, R. Spano, and F.E. Vaca. 2019. Bolstering Gun Injury Surveillance Accuracy Using Capture-Recapture Methods. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 42(4): 674–680.

Pridemore, W.A. 2005. A Cautionary Note on Using County-Level Crime and Homicide Data. Homicide Studies 9(3): 256–268.

Reynolds, A. E. 2021. Nonfatal Shootings: A Comparison of Unintentional and Criminal Incidents [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation]. University of Indianapolis.

Roman, J. K. 2020. The State of Firearms Data in 2019. Chicago, IL.

Rosenfeld, R., and E. Lopez. 2020. Pandemic, Social Unrest, and Crime in Us Cities. Washington, DC: Council on Criminal Justice.

Sehgal, A.R. 2020. Lifetime Risk of Death from Firearm Injuries, Drug Overdoses, and Motor Vehicle Accidents in the United States. The American Journal of Medicine 133(10): 1162-1167.e1161.

Victim Rights Law Center. 2014. Mandatory Reporting of Non-accidental Injuries: A State-by-State Guide (Updated May 2014). Boston, MA.

Webster, D.W., M. Cerdá, G.J. Wintemute, and P.J. Cook. 2016. Epidemiologic Evidence to Guide the Understanding and Prevention of Gun Violence. Epidemiologic Reviews 38(1): 1–4.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department for their partnership and for providing access to the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Reynolds, A.E., Hipple, N.K., Hancher-Rauch, H. et al. Unintentional nonfatal shootings: using police data to provide context. Crime Prev Community Saf 24, 211–223 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-022-00155-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-022-00155-z