Abstract

This study intends to clarify the psychological mechanism that explains the crisis responsibility and corporate reputation link, aiming at gaining knowledge on individuals’ perception formations in and reactions to a crisis. We extended the situational crisis communication theory through identifying the moderation effects of personal relevance and person–company fit in this relationship. The VW emissions scandal was investigated with respect to its impact on post-crisis reputation and negative word-of-mouth. A sample of 721 German respondents was analyzed through structural equation modeling. The results suggest that personal relevance strengthens the positive relationship between crisis responsibility and anger. Next to this, person–company fit weakens the impact of crisis responsibility on anger, as well as on sympathy. The results suggest that more attention needs to be drawn on the personal perspective in crisis communication, while different response strategies should be developed with respect to distinct stakeholder groups for protecting corporate reputation in the crisis context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

On September 18, 2015, the Volkswagen (VW) Group was accused of intentionally manipulating VW and Audi cars with sophisticated software to bypass Clean Air Act standards (Kollewe 2015)—this incident became known as the VW emissions scandal. Germany, being a country in which “one in seven people earn their living, directly or indirectly, from auto making” (Bender 2015, para. 3), was shocked. The crisis affected more than 11 million cars of the brands VW, Audi, Seat, Skoda and Porsche worldwide (Kollewe 2015), of which 2.4 million alone in Germany (heise online 2016). Further, it resulted in a fall of the company’s shares (Geier 2015) and a substantial decline of sales (The Guardian 2016), followed by a large product recall. Sweeping restructuring efforts were paid to rebound its performance, which only started to regain customers’ trust in the German carmarket in early 2017 (McGee 2017).

Crisis communication plays an important role for protecting an organization’s post-crisis reputation in a product recall (Coombs 2007). Despite so, it has not been extensively investigated in this context (Laufer and Jung 2010). Studies in the past mainly focused on product recall crises in North America (Lee 2004), whereas Coombs (2014) calls for a good understanding of the role of crisis communication in other markets as well as in the global dimension. As the VW emissions scandal is recognized as a crisis for which the firm is held responsible (Vizard 2015), a good understanding of it may add value to the field of crisis communication research. In this study, we aim to clarify the mechanism through which the VW emissions scandal affected distinct stakeholders’ perceptions differently. Unfolding such a relationship is important for an organization to carry out effective corporate responding strategies because an organization can then tailor its crisis communication toward the interests of different stakeholder groups.

This study draws on the Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) (Coombs 2007) as groundwork. SCCT is vital for understanding the components of a crisis and developing appropriate crisis communication strategies. However, to our best knowledge, most existing research on crisis communication adopting the SCCT were not audience-oriented (Lee 2004) and little research has included the personal perspective, such as perceived personal involvement (Choi and Lin 2009a) so far. This is crucial, though, to assess how individuals understand and react to a crisis (Lee 2004). Hence, an increasing number of authors (e.g., Coombs and Holladay 2002; Dawar and Pillutla 2000) call for research on different stakeholders’ perceptions in the crisis context (Choi and Lin 2009b). Moreover, several scholars have suggested the importance of incorporating the personal perspective in crisis communication research (Coombs and Holladay 2014; Choi and Lin 2009a; Lee 2004). Therefore, this study intends to clarify the psychological processes that link attribution to reputation perceptions, aiming at gaining knowledge on individuals’ perception formations in and reactions to a crisis.

Our results suggest that personal relevance strengthens the positive relationship between crisis responsibility and anger. Next to this, person–company fit weakens the impact of crisis responsibility on anger, as well as on sympathy. This implies that the individuals who are highly identified with an organization may feel being hurt or betrayed in an intentional crisis, thus, show less compassion toward the organization, compared to others. The results suggest that more attention needs to be drawn on the personal perspective in crisis communication, while different strategies should be developed with respect to distinct stakeholder groups for protecting corporate reputation.

Theory

The Impact of Crisis Responsibility on Corporate Reputation and NWOM

Coombs (2007) defines a crisis as “a sudden and unexpected event that threatens to disrupt an organization’s operations and poses both a financial and a reputational threat” (p. 164). A crisis occurs when stakeholders perceive violations of their expectations of an organization (Coombs 2014). The SCCT (see e.g., Coombs and Holladay 2002; Coombs 2004, 2007; Kim and Cameron 2011) provides managers with guidelines to match crisis response strategies to different crisis types. It identifies three types of crises, known as the victim crisis, accidental crisis and intentional crisis, respectively. Each crisis type defines how much responsibility the stakeholders attribute to an organization. Thereby, an intentional crisis, such as human-error product harm or organizational misdeed, has the strongest attribution of crisis responsibility and poses a severe reputational threat (Claeys et al. 2010).

Crisis responsibility is recognized as one of the key deterministic factors that support the comprehension of the harmful impact of a crisis in the SCCT (Coombs 2007, 2015). It is derived from attribution theory (Coombs 2015), in which causal attributions play a pivotal role (Weiner 1985). Crisis responsibility can either be attributed to the person or organization embroiled in the event (internal), or to circumstantial (external) factors (Coombs 2010). The attribution of internal or external responsibility is essential in inducing affective reactions or behaviors to the organization (Weiner 1986). In the case of a high degree of internal responsibility, oftentimes more negative perceptions threatening corporate reputation are observed among stakeholders (Coombs 2007; Weiner 2006).

Corporate reputation is “an evaluation stakeholders make about an organization” (Coombs and Holladay 2006, p. 123). Favorable reputations are regarded as intangible assets that have been related to positive outcomes for an organization (Coombs 2007; Coombs and Holladay 2006; Gibson et al. 2006; Rhee and Haunschild 2006). As Fombrun and van Riel (2004) put it: “A good reputation is like a magnet: It attracts us to those who have it” (p. 3). The formation of reputation is dependent on an organization’s past actions (Kiambi and Shafer 2015; van Riel and Fombrun 2007) and is generated from cognitive associations, which are derived from information that stakeholders receive about an organization over time (Fombrun and van Riel 2004; Rhee and Haunschild 2006; van Riel and Fombrun 2007; Turk et al. 2012).

A good reputation leads to higher expectations of an organization among stakeholders (e.g., Dean 2004; Grunwald and Hempelmann 2011; Rhee and Haunschild 2006). If these expectations are violated in a crisis, well-reputed organizations will be punished more sternly (Sohn and Lariscy 2015), for instance, by causing them to pay higher restitutions in order to resolve the incident (Grunwald and Hempelmann 2011). Sohn and Lariscy (2015) call this mechanism the ‘boomerang effect’. It justifies the reason that corporate reputation inflicts severe damage to an organization at negative events. As for the VW emissions scandal, the individuals who trust the company on its good reputation before the crisis may experience a high violation of their expectations due to the strong attribution of the crisis responsibility to the VW Group. Thus, they may suffer from the boomerang effect and form negative perceptions toward the VW Group. Accordingly, the corporate reputation of the VW Group will be influenced negatively by the crisis responsibility.

H1

Crisis responsibility influences post-crisis reputation negatively.

Besides the potential negative effect on reputation, the SCCT suggests the importance to connect the impact of a crisis to customers’ behavioral intention, such as negative word-of-mouth intention (Coombs 2010; Coombs and Holladay 2008), as “If crises altered reputations and create affect but did not impact behavioral intentions, there would be no reason to worry about the effects of crises” (Coombs 2007, p. 169). However, research only showed limited support for the affect–behavioral intention relationship (Coombs and Holladay 2004), thus calls for more investigations to clarify how behavioral intentions are affected by a corporate crisis. Negative word-of-mouth (NWOM) is an informal, noncommercial person-to-person communication among communicators about brands, products, services or organizations (Anderson 1998; Harrison-Walker 2001; Richins 1984; Goyette et al. 2010). It relates to statements that stakeholders make about a corporation (Schultz et al. 2011), and has long been accepted as a dominant power in influencing the evaluation of brands (Laczniak et al. 2001), products (Rea et al. 2014) and organizations (Kiambi and Shafer 2015). It may also change a person’s present and future purchase decisions (Chu and Li 2012; Coombs and Holladay 2007; Schultz et al. 2011) and is thus widely recognized as a threat to an organization (Coombs 2010, 2014; Coombs et al. 2007). The emergence of new media (e.g., online forums) further enforces the negative influence of NWOM on corporations (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2004; Silverman 2001).

A high tendency to use NWOM in an intentional crisis is addressed in literature (e.g., Utz et al. 2013; Kiambi and Shafer 2015). For instance, Utz et al. (2013) found for the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster that secondary crisis communication, such as NWOM, is salient among the public. Despite these findings, Kiambi and Shafer (2015) call for more research on NWOM in the crisis context. Since the VW Group possessed a good reputation prior to the emissions scandal, it is not clear to what extent the NWOM intention is affected by the crisis. However, as the VW emissions scandal is recognized as an intentional crisis, the NWOM of the stakeholders is expected to be present after the crisis due to its severity. As a consequence, the crisis responsibility attributed to the VW Group corresponds to the existence of NWOM among the stakeholders.

H2

Crisis responsibility influences NWOM positively.

The Mediation Role of Emotions: Anger vs. Sympathy

Crisis communication may protect an organization’s reputation more effectively, if the stakeholders’ affective reactions are taken into account (Coombs and Holladay 2005), as crisis managers can respond more properly to the incident (Laufer and Coombs 2006). Despite so, the role of emotional responses in the crisis context has only been studied in recent years (see e.g., Choi and Lin 2009a, 2009b, 2009c; Coombs et al. 2007; Jin 2009, 2010; Jin et al. 2012; Kim and Cameron 2011).

Coombs and Holladay (2005) argue that crises will not only trigger attributions but also create emotional responses among individuals. In accordance with the attribution theory, anger and sympathy are stated as the main emotions in the context of post-crisis communication (Coombs and Holladay 2005, 2008). Anger toward a crisis is mainly triggered when the responsibility is attributed to an organization for a violation or sorrow (Iyer and Oldmeadow 2006; Lindner 2006; Jin 2010). Sympathy, on the other hand, is evoked through witnessing others’ suffering, in particular, when the suffering is seen as undeserved (Gruen and Mendelsohn 1986; Salovey and Rosenhan 1989). Only few studies in crisis research have centered on the impact of sympathy, though the significance of positive affects in communication is argued to be apparent (Folkman and Moskowitz 2000; Jin 2014).

In the SCCT, emotion is incorporated as a predictor for behavioral intentions but not for reputation (Coombs 2007; Choi and Lin 2009b). However, Jin et al. (2007) argue that emotions in a crisis can have an impact on people’s perceptions about an organization. Choi and Lin (2009b) thus proposed a revised conceptual model of SCCT that contained a direct path from emotions to reputation. They found that a higher level of anger significantly corresponds with a lower corporate reputation. This highlights the importance of considering emotional reactions when aiming to protect an organization’s reputation (Choi and Lin 2009b). In line with the revised SCCT model proposed by Choi and Lin (2009b), we conjecture that anger mediates the impact of crisis responsibility on reputation: Crisis responsibility attributed to an organization results in a high level of anger, thus leading to the damage on an organization’s reputation. Parallel to this, the mediation role of sympathy is also expected, however, through a different mechanism: The higher the crisis responsibility attributed to an organization, the less sympathy is generated among the stakeholders and thus the more negatively the post-crisis reputation is affected.

H3a

Anger mediates the impact of crisis responsibility on corporate reputation.

H3b

Sympathy mediates the impact of crisis responsibility on corporate reputation.

Emotions also trigger behavioral intentions, such as NWOM (Coombs and Holladay 2007; Coombs 2007, 2014). Anger, for instance, has been found to lead to NWOM intention since people are inclined to express their feelings or avenge (Wetzer et al. 2007). Coombs et al. (2007) posit that unhappy customers have a higher proclivity to tell close friends about their purchasing experience than those who are satisfied with their experience. Utz et al. (2013) further reveal that anger has an impact on secondary crisis communication. This so-called “negative communication dynamic” is, however, not always confirmed in literature. As suggested in Coombs et al. (2007), a moderate level of anger toward a crisis may not be sufficient to develop a negative communication dynamic. When a higher level of anger is observed, individuals may support an organization less and tend to use NWOM more likely (McDonald et al. 2010). As a high crisis responsibility attributed to an organization often triggers a high level of anger, a strong NWOM intention is thus expected. In other words, anger mediates the impact of crisis responsibility on NWOM. Sympathy, on the other hand, is argued to play a less important role in the crisis than anger, since the positive affect might not influence stakeholders to a large extent (Coombs and Holladay 2005). Despite so, the individuals who hold a high level of sympathy may be more willing to take actions in support of the organization, thus, are less inclined to engage in NWOM. Therefore, parallel to anger, sympathy also mediates the impact of crisis responsibility on NWOM, though in a different manner.

H4a

Anger mediates the impact of crisis responsibility on NWOM.

H4b

Sympathy mediates the impact of crisis responsibility on NWOM.

The Moderation Roles of Personal Relevance and Person–Company Fit

Recently, several scholars stressed the importance of understanding how the personal perspective affects crisis outcomes (see e.g., Choi and Lin 2009a; b; Claeys and Cauberghe 2015; Dean 2004). For instance, Laufer and Jung (2010) applied regulatory focus theory to examine whether consumers with different regulatory systems (i.e., promotion focus vs. prevention focus) react differently to product recall communication, and found that creating regulatory fit is crucial for increasing intentions to comply with a product recall request. Likewise, Laufer and Wang (2017) adopted the accessibility–diagnosticity theory from psychology to explain how crisis information is processed by consumers as well as its consequence on the possibility of triggering a crisis contagion. A high similarity of companies, for instance, may trigger consumers to classify them into one category. If one company is in crisis, others belonging to the same category may be affected even without any wrong-doing, due to a high accessibility in consumers’ mental system (Laufer and Wang 2017; Roehm and Tybout 2006; Yu et al. 2008).

Despite these findings, Choi and Lin (2009b) note that not much is yet known about how potentially affected stakeholders respond to a crisis and how their responses should be incorporated into the SCCT. The comprehension of these reactions can be used for guiding an organization’s post-crisis communication (Härtel et al. 1998; Coombs 2007; Kim and Cameron 2011). Therefore, Choi and Lin (2009a) conclude that the inclusion of consumer involvement into the SCCT is a “logical next step for future research in crisis communication” (p. 21). In response to this call, this study examines the moderation impact of two personal-related factors—personal relevance and person–company fit—on the aforementioned crisis outcomes, aiming to extending the SCCT through identifying distinct crisis communication strategies with regards to different stakeholder groups.

Personal relevance refers to an individual’s perceived importance of an event based on inherent values and needs (Celsi and Olson 1988; Zaichkowsky 1985). It defines an individual’s subjective sense of personal involvement in a situation or action, the so called “felt involvement” (Celsi and Olson 1988). The public relations literature has highlighted the crucial role of personal relevance regarding audience’s receptivity to information and issues (Heath and Douglas 1990; Choi and Chung 2013). Since it affects the cognitive processes such as attention and comprehension, personal relevance has a direct impact on attitude change (Petty and Cacioppo 1981, 1986; Maclnnis et al. 2002): While highly involved individuals process information on the central route—paying more attention to the quality of the arguments, low-involved individuals process it on the peripheral route and pay more attention to aspects such as the source credibility of the message. Thus, the higher an individual perceives an event as personally relevant, the more difficult it is to change his attitude toward it. This argument is further supported by Avnet et al. (2013) who found that the level of personal involvement determines the persuasion process significantly.

McDonald and Härtel (2000) were the first to apply personal relevance to the crisis communication context. They stress that although the attribution theory views the personal relevance of an event as critical, it hardly integrates the concept into the model. Instead, the affective events theory proposed by Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) argues that the level of personal relevance defines the intensity of emotions that customers feel in a crisis. Choi and Lin (2009a), for instance, assume that high crisis involvement stimulates more in-depth comprehension of crisis information than low involvement, and confirms the existence of a direct link between product involvement and anger in this event. However, Choi and Lin (2009a) do not compare high and low involvement with regards to crisis evaluation of consumers. More recently, Claeys and Cauberghe (2014) fill this gap through incorporating personal involvement into the SCCT framework. They demonstrate that with a high crisis involvement, crisis response strategies that match the crisis types increase the post-crisis attitude toward the organization. However, they manipulated personal involvement in their experiment as opposed to measuring “felt involvement” directly, though this may add more insights to the cognitive process in the crisis context.

Based on the findings in literature, we conjecture that the impact of crisis responsibility on the German public’s emotions may vary in the VW emissions scandal, depending on the level of personal relevance. The individuals who perceive the crisis with high level of personal relevance are more inclined to devote attention to the content of the crisis information than individuals with low relevance (Maclnnis et al. 2002). As a consequence, they may assess the crisis responsibility of the VW Group as more salient and harmful, thus, will show more anger and less sympathy toward the organization. In contrast, the individuals perceiving themselves as less involved in the crisis correspond to a weaker impact of crisis responsibility on anger and sympathy. In other words, personal relevance moderates the impact of crisis responsibility on anger and sympathy, respectively.

H5a

A high personal relevance strengthens the positive impact of crisis responsibility on anger.

H5b

A high personal relevance strengthens the negative impact of crisis responsibility on sympathy.

Person–company fit originates from the concept of social identification, which refers to “the perception of oneness with or belongingness to a group, involving direct or vicarious experience of its successes and failures” (Ashforth and Mae 1989, p. 34). The social identity theory postulates that individuals are inclined to categorize themselves into social groups, as it enables them to situate themselves in their social environment (Pérez 2009; Ashforth and Mael 1989; Tajfel and Turner 1985). Ashforth and Mael (1989) transferred the concept of social identification to an organizational context and argue that organizational identification is a particular type of social identification. The organization thereby functions as a social category that might fulfill motives for the individual and that the individual uses to build up self-confidence (Ashforth and Mael 1989). People who have a strong identification with an organization behave in a way that is coherent with the organization’s values, beliefs, and culture (Xiao and Hwan (Mark) Lee 2014).

Person–company fit has been widely studied in the marketing domain (e.g., Lichtenstein et al. 2004; Bhattacharysa and Sen 2003). For instance, it was found that consumers who identify themselves with a company often have a mental connection with it (Dutton et al. 1994; Bhattacharya and Sen 2003) and may adjust their actions to the company’s aims and interests (Mael and Ashforth 1992). They may even show enthusiasm about the company’s activities (Chu and Li 2012). High customer–company identification is argued to benefit an organization through generating customer loyalty (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003; Lichtenstein et al. 2004), forming appealing attitudes toward an organization (Du et al. 2007; Einwiller et al. 2006; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001) and enhancing customers’ commitment to it (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003; Kim et al. 2010).

Even without the existence of interpersonal connection or interaction with an organization, person–company fit may still emerge (Ashforth and Mael 1989). Thus, it can be argued that not only customers, but also noncustomers can feel certain identification with an organization. This would signify that Germans as a whole may develop certain level of identification with the VW Group. The identification can even endure when “group failure is likely” (Ashforth and Mael 1989, p. 35). This implies that within a crisis scenario, the stakeholders who hold a high identification with an organization may still feel emotionally connected with it, thus supporting its activities. In other words, they may believe in the organization’s values and consider themselves as part of the group, despite the negative event. As a consequence, the crisis responsibility attributed to the organization may evoke less anger but more sympathy among those individuals with a higher person–company fit than others who possess a lower person–company fit. Therefore, we predict that the supportive attitudes among the highly identified individuals weaken the impact of crisis responsibility on anger and sympathy, respectively. In other words, with a high person–company fit, the positive relationship of crisis responsibility and anger becomes less positive, while the negative relationship of crisis responsibility and sympathy becomes less negative.

H6a

A high person–company fit weakens the positive impact of crisis responsibility on anger.

H6b

A high person–company fit weakens the negative impact of crisis responsibility on sympathy.

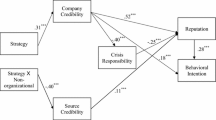

In summary, personal relevance and person–company fit both determine the level that an individual seeks, perceives, and values crisis information. A person may perceive the crisis information as more important than his prior knowledge of the organization if he regards the crisis as more relevant personally. Parallel to it, one may value the crisis information as less crucial if he feels highly identified with the organization. Given the weights assigned to the crisis information differently due to these personal-related factors, their emotions are affected correspondingly. Our predictions are illustrated in the conceptual model in Fig. 1.

Method

Data Collection

An online survey was conducted for data collection. The participants were recruited through the German online access-panel SoSci,Footnote 1 which is a free and noncommercial panel with a pool of more than 93,000 registered persons (“SoSci Panel für Wissenschaftler” 2015). The data was collected between 2 and 16 June 2016. An email was sent to 4500 SoSci panel members. A total of 1025 respondents participated in the survey, among which, 879 completed the questionnaire, resulting in a response rate of 20%. We excluded the participants who were not of German nationality, leading to a final sample of 721 German participants with an average age of 40 (SD 15.03; range = 17–83 years). Approximately 51.3% were male (N = 370) and 48.7% were female (N = 351). The majority of the participants (59.5%, N = 429) obtained a university degree. Furthermore, 34% (N = 245) of the participants indicated to currently own a car of the VW Group, among which the majority (73.5%, N = 180) does not own a car affected by the VW emissions scandal.

Measures

Previously validated measures were used in this study, and adapted to the context of the VW emissions scandal. The seven latent variables—crisis responsibility, anger, sympathy, reputation, NWOM, personal relevance and person–company fit—were first defined by indicators, then measured by self-reported responses on an attitude scale (Byrne 2013), as shown in Table 1.

Measuring Dependent Variables: Post-crisis Reputation and NWOM

Two dependent variables were measured in this study: Post-crisis reputation and NWOM. Post-crisis reputation was assessed using the five-item Organizational Reputation Scale (Coombs and Holladay 1996, 2002; Coombs 2004). This scale was originally adapted from McCroskey’s (1966) Character subscale for measuring ethos (Coombs and Holladay 2002). In our study, the scale was assessed using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from one to seven (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). In order to measure the intention for NWOM, three items from previous studies were applied (e.g., Coombs and Holladay 2008, 2009; Kiambi and Shafer 2015). Similar to post-crisis reputation, this concept was also measured using a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Measuring Independent Variable: Crisis Responsibility

To assess crisis responsibility, the newly invented scale by Brown and Ki (2013) was used and measured on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). As a result of the pre-test, the scale for crisis responsibility was reduced to an eight-item scale, making it shorter and less repetitive. More precisely, the three-item dimensions intentionality and locality were each reduced by one item and the dimension accountability was reduced by two items. See Table 1 for the final version for the scale.

Measuring Mediators: Anger and Sympathy

The mediator variables anger and sympathy were assessed using two four-item scales from McDonald et al. 2011). The authors criticized “the absence of scales using words that incorporate consumers’ own crisis emotion lexicon and which are psychometrically robust” (McDonald et al. 2011, p. 337). The anger scale contained the items angry, disgusted, annoyed, outraged, while the sympathy scale consisted of the items sympathetic, sorry, compassion, empathy (McDonald et al. 2011). In this study, both concepts were measured using a seven-point Likert scale whereas 1 means “not at all” and 7 means “very much”.

Measuring Moderators: Personal Relevance and Person–Company Fit

Personal relevance was assessed based on the six-item, seven-point bipolar scale by Wigley and Pfau (2010). The scale is based on the involvement scale by Zaichkowski (1985). Due to the accessibility of the questionnaire, a seven-point Likert scale was used for this measurement. The moderator variable person–company fit was measured using five items. These items were previously developed by Lin et al. (2011) based on scales by Keh and Xie (2009) and Mael and Ashforth (1992) as well as items of Mael and Ashforth (1992) themselves. The scale was measured using a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Measurement Model

The analysis was conducted through structural equation modeling (SEM). First, we followed Luo and Bhattacharya (2006) to employ confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the validity of the measures of the latent variables. All variables in the model were standardized as a preparation for generating the interaction terms (Aiken and West 1991) and all factors were allowed to correlate. The results are presented in Table 2. It can be observed that all constructs have a Cronbach’s alpha above the 0.7 threshold (Nunnally 1978), suggesting a good lower bound for reliability. The factor loadings of the same constructs are all higher than 0.5 only except for Resp5. In addition, the average variance extracted (AVEs) values are all above the 0.5 benchmark (Fornell and Larcker 1981) and the composite reliability all above 0.7, confirming a satisfied convergent validity. For testing the discriminant validity, we follow Fornell and Larcker (1981) to compare the square root of AVEs with the correlations across the constructs. As shown in Table 3, the square roots of AVEs are greater than the absolute values of all other entries in the corresponding rows and columns, lending some support for the discriminant validity in the measurement model. Overall model statistics show that the comparative fit index (CFI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (.895, .910, and .068, respectively) are above or nevertheless close to the threshold, suggesting a good model fit. However, the Chi-square for the model is 981.98 (d.f. = 226, p > 0.05). The high χ2/df value might be attributed to the complexity of our model due to the number of items involved (Hair et al. 2010; Theo et al. 2013). Similar issues are found in other published articles too (e.g., Liao et al. 2009; Conway et al. 2015). As most indicators for model fit are above the threshold, we decided to save this measurement model for testing the hypotheses.

Results

The influences of crisis responsibility on post-crisis reputation and NWOM are shown in Model 2 (see Table 4). The results suggest a significant negative relationship between crisis responsibility and post-crisis reputation, but not for NWOM. Thus, H1 is confirmed while H2 is rejected. Next, we followed the four-step approach discussed in Baron and Kenny (1986) and Luo and Bhattacharya (2006) to test the mediation effects. As shown in Model 1, the positive impact of crisis responsibility on anger and the negative impact of it on sympathy are both significant. In addition, anger and sympathy significantly influence post-crisis reputation and NWOM in the predicted direction. When the mediators—anger and sympathy are controlled, as in Model 3, the strength of the direct impact on post-crisis reputation is reduced from − .20 to − .132, suggesting the existence of a partial mediation effect.

In addition to our predictions, we also found the mediation role of anger and sympathy on personal relevance. Since personal relevance was controlled in the model, it was possible to test whether the conditions for the mediation effect hold for it, too. The results suggest that the impact of personal relevance on post-crisis reputation is fully mediated (i.e., a significant path estimate of − .208 in Model 2 and an insignificant estimate of − .066 in Model 3), while its impact on NWOM is partially mediated (i.e., a decrease of path estimate from .406 in Model 2 to .219 in Model 3). It implies that the German individuals who regarded the VW emissions scandal as more important and personal are angrier about and sympathize less with the VW Group, leading to more negative impact on post-crisis reputation and more positive impact on NWOM.

The moderation effects are shown in Table 5. The interaction terms were added from Model 2 to Model 3. Based on the results—a significant interaction effect of personal relevance on anger at the 90% confidence interval but not on sympathy was identified. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between crisis responsibility and anger for individuals with low and high personal relevance. In addition, the results partially confirm our prediction on person–company fit: The moderation effect weakens the direct effect on anger. However, as for sympathy, the moderation effect strengthens the direct effect. In other words, the German individuals who are more identified with the VW Group are even less sympathized with the company. This result contradicts to our conjecture. It implies that people who are more identified with an organization may feel betrayed or being hurt in an intentional crisis and thus show less compassion to the organization. Figure 3 illustrates the observed moderation effects of person–company fit.

Further, we investigated the influence of demographics (i.e., gender, age, ownership) on perceived crisis responsibility, emotions, personal relevance, person–company fit, post-crisis reputation and NWoM. An independent t test shows no significant difference with respect to gender, only except for personal relevance. Men tended to perceive the VW crisis more relevant personally than women, t(719) = − 2.246, p < .005. Levene’s test indicated unequal variances (F = 7.328, p = .007), so degrees of freedom were adjusted from 719 to 716. Age, however, turned out to be a deterministic factor of crisis perception. Older participants (age > 40) are found to attribute more crisis responsibility to VW than younger participants (age < 40), t(719) = − 5.234, p < .001; They also feel the scandal more relevant personally than younger participants, t(719) = 5.005, p < .001. Levene’s test indicated unequal variances (F = 8.613, p = .003), so degrees of freedom were adjusted from 719 to 668. Correspondingly, older participants showed more anger (t = 4.674, p < .001, d = 719) whereas less sympathy (t = − 3.458, p < .001, d = 719) toward VW, perceived the post-crisis reputation lower than the younger participants (t = − 4.699, p < .001, d = 719. Levene’s test indicated unequal variances, F = 1.487, p = .223, so degrees of freedom were adjusted from 719 to 682), and were more willing to communicate negative things about the company (t = 2.713, p < .01, d = 719. Levene’s test indicated unequal variances, F = .041, p = .840, so degrees of freedom were adjusted from 719 to 702). Last but not the least, in comparison to the participants who do not own a car of VW, customers (i.e., who own a car of VW) were observed to perceive a higher fit with the company (t = 8.844, p < .001, d = 719).

Discussion

This study contributes to literature through investigating individuals’ perception formations in and reactions to a crisis. We extended the situational crisis communication theory through identifying the important role of personal relevance and person–company fit. The results suggest that customers’ emotion toward a crisis is determined by personal-related factors: Personal relevance strengthens the positive relationship between crisis responsibility and anger. Person–company fit, on the other hand, weakens the impact of crisis responsibility on anger, as well as on sympathy.

Several theoretical implications can be drawn from the results. First, they suggest the importance of extending the SCCT by paying more attention to the personal-related factors. Both personal relevance and person–company fit were confirmed to moderate the impact of crisis responsibility on emotions. Our results support the findings of Choi and Lin (2009a) and Claeys and Cauberghe (2014) that personal relevance stimulates more in-depth comprehension of crisis information, thus, leading to an influence on crisis outcomes. However, we advance the literature in examining the role of personal relevance on two types of emotions. This result contradicts to Ashforth and Mael’s (1989) assumption that the identification with a group endures even after the failure of the group. It might be due to the feelings of outright betrayal triggered by the severe and intentional crisis, which results in the negative effect of person–company fit on an organization.

In addition to the moderation effects, we also observed a direct effect of personal relevance on both emotions. This finding supports McDonald and Härtel’s (2000) and Coombs and Holladay’s (2005) assumptions that the level of involvement determines a person’s intensity of emotions in a crisis. When determining anger, the effect is even stronger than that of crisis responsibility. This is contrary to the findings of McDonald et al. (2010), who clarified crisis responsibility as a more important predictor for emotional reactions in a crisis than personal relevance. Given that McDonald et al. (2010) used the same measurement for personal relevance, this finding is especially interesting. These opposing results might be explained by the different research approaches employed by McDonald et al. (2010) and this study. While McDonald et al. (2010) used an experimental setup with an artificial airline company, our study focused on a real crisis scenario and measured the perceptions through a survey method.

Despite the crisis responsibility attributed to the VW Group, we could not confirm its direct impact on NWOM. In other words, high crisis responsibility does not necessarily lead to a high NWOM intention. This result coincides, though, with the finding in Kiambi and Shafer (2015) that a low intention to express NWOM is often observed for highly reputed organizations. On the other hand, emotions generated by crisis responsibility, are shown to be associated with the level of NWOM. However, the magnitudes of the impact of anger and sympathy on post-crisis reputation are rather comparable, suggesting salient occurrence of both emotions, simultaneously. It confirms the “negative communication dynamic” predicted in Coombs et al. (2007) that the stakeholders whose anger are triggered by a crisis are more likely to express NWOM than others. However, the result contradicts the prediction in Coombs and Holladay (2005) that sympathy may not affect stakeholders’ perceptions to a large extent compared to the negative emotions. The conflicting finding might be explained by the focus on German population in our study (i.e., the home-country bias). The country dimension plays an important role in individual’s judgment and emotion formation in a crisis (Balabanis and Diamantopoulos 2004; Etayankara and Bapuji 2009). Consumers are often found to be more positive when assessing domestic products versus foreign alternatives (Verlegh 2007). As the German respondents may be emotionally associated with the VW Group before the crisis, it is not surprising that the impact of sympathy is as strong as that of anger in the VW emissions scandal. This result highlighted the value of the country dimension in the crisis context, which should be taken into account when applying crisis communication theories, such as the SCCT, to explain specific responses.

The findings of this study also provide organizations with managerial implications with respect to mitigating the damage of a crisis and retaining corporate reputation. First, the level of individual’s involvement may determine the effectiveness of a response strategy. Since the individuals with a high involvement tend to focus more on the content elements of a message (Maclnnis et al. 2002; Claeys and Cauberghe 2014), useful information (e.g., compensation, instructing information) with respect to how the crisis will be handled should be provided in the response, in addition to a sincere apology. For instance, as customers who own an affected car of VW may regard the crisis as highly relevant personally, corporate crisis managers thus should come up with a timely solution-oriented responding strategy, with an emphasis on how victims of the crisis will be compensated.

Second, crisis communication managers should be aware of a potential negative impact of person–company fit. A high identification may enhance the stakeholders’ commitment to an organization in a variety of scenarios (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003; Kim et al. 2010), but seems to be difficult to leverage in an intentional crisis. This is potentially due to the feeling of outright betrayal—the more loyal the customers are, the more likely they may feel being cheated in an intentional crisis. Therefore, instead of taking the support of highly identified stakeholders for granted, crisis communication managers should pay additional attention to this specific group with respect to fulfilling their expectation in a crisis. Tricking of information in a global scandal like the VW emission will only keep the story on the front pages. Instead, to move with deliberate haste to begin the recovery process is crucial for regaining trust among the engaged customers. For instance, VW may reach out customers who are appalled by the environmental impact of the emission scandal, and in the meanwhile, suggest an outreach to VW customers whose car are not affected (Garcia 2015).

On the other hand, researchers also found that a corporate crisis tends to be forgotten by the public over time (see e.g., Carroll 2009; Vassilikopoulou et al. 2009), especially when the company issues a voluntary recall of its product. One explanation is that being exposed to constant stream of new information in daily lives, people are likely to shift their attention away from a company’s past mistakes to more contemporary issues. The recovery of VW’s sales performance in 2017 right confirms this finding. However, to bounce back from a misdeed in the past was not realized without a cost. After paying for fines, buybacks, and a massive global recall, the sweeping restructuring efforts taken by VW only start to show its value after the company being locked in crisis mode for more than a year (Rauwald 2017). As a company’s sensible response (e.g., assuming full responsibility and asking for forgiveness from stakeholders) is likely to facilitate collective forgetting, from a crisis communication perspective, it is important for a company to show its intention to do substantive things about the scandal, rather than creating short term solutions only. In addition, companies should remember the lessons learnt during a scandal themselves, while holding onto reminders of their wrong-doing in the long run.

Further, the demographic results show that age plays an important role in determining emotions and perceptions in a crisis context. The older customers not only engage more in a crisis while regarding it as a personal-related issue, but also express more negative emotions and cynicism in comparison to the younger customers. This finding confirms the general pattern addressed in marketing literature that aging customers are skeptical and discerning (Leventhal 1997; Szmigin and Carrigan 2001). Crisis communication managers should thus investigate the different motives and identities of the older customers, in order to maintain a good relationship with this customer group and to better meet their expectations in terms of appropriate crisis message and response.

Despite the contributions, we are aware of potential limitations of this study. First of all, we only measured the VW Group’s reputation after the crisis but not that before the occurrence of the emissions scandal. Although several sources (e.g., Fombrun 2015; Reputation Institute 2013, 2014, 2015) agreed on the VW Group’s favorable reputation before the crisis, no reputation loss could be explicitly detected based on this study’s results. In addition, since the data was collected half a year after the first information on the emissions scandal was disclosed, it may have an effect on the evaluation of the perception of the post-crisis reputation, as well as on other measurements. For instance, the corporate reputation may have partially recovered from the crisis while the level of anger may have decreased at a certain level. Second, the response strategy of the VW Group was not examined in this study. Since we identified that different message framing (i.e., content-based vs. emotional-based) may affect respondents distinctively, further research can draw on the effectiveness of the VW Group’s response strategy toward specific stakeholder groups. In this context, the role of the VW Group’s former CEO Martin Winterkorn would be worth studying. As shown in Turk et al. (2012), CEO visibility in immediate crisis response is effective in generating positive attitude purchase intention in a crisis. However, how the response of Martin Winterkorn affected the perceptions among different stakeholders in the VW emissions scandal is yet unknown.

References

Aiken, L., and S.G. West. 1991. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Anderson, E.W. 1998. Customer satisfaction and word of mouth. Journal of Service Research 1 (1): 5–17.

Ashforth, B.E., and F. Mael. 1989. Social identity theory and the organization. The Academy of management review 14 (1): 20–39.

Avnet, T., D. Laufer, and E.T. Higgins. 2013. Are all experiences of fit created equal? Two paths to persuasion. Journal of Consumer Psychology 23: 301–316.

Balabanis, G., and A. Diamantopoulos. 2004. Domestic country bias, country-of-origin effects, and consumer ethnocentrism: A multidimensional unfolding approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 32 (1): 80–95.

Baron, R.M., and D.A. Kenny. 1986. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social behaviours. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (6): 443–464.

Bender, R. 2015. Volkswagen scandal tests auto-loving Germany. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://www.wsj.com/articles/vw-scandal-tests-auto-loving-germany-1443217183.

Bhattacharya, C.B., and S. Sen. 2003. Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing 67 (2): 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609.

Brown, K.A., and E.J. Ki. 2013. Developing a valid and reliable measure of organizational crisis responsibility. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 90 (2): 363–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699013482911.

Byrne, B.M. 2013. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York: Routledge.

Carroll, C. 2009. Defying a reputational crisis–Cadbury’s salmonella scare: Why are customers willing to forgive and forget? Corporate Reputation Review 12 (1): 64–82.

Celsi, R.L., and J.C. Olson. 1988. The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. Journal of Consumer Research 15 (2): 210–224.

Choi, J., and W. Chung. 2013. Analysis of the interactive relationship between apology and product involvement in crisis communication: Study on the Toyota recall crisis. Journal of Business and Technical Communication 27 (1): 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651912458923.

Choi, Y., and Y.H. Lin. 2009a. Consumer response to crisis: Exploring the concept of involvement in Mattel product recalls. Public Relations Review 35: 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.09.009.

Choi, Y., and Y.H. Lin. 2009b. Consumer responses to Mattel product recalls posted on online bulletin boards: Exploring two types of emotion. Journal of Public Relations Research 21 (2): 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/10627260802557506.

Choi, Y., and Y.H. Lin. 2009c. Individual difference in crisis response perception: How do legal experts and lay people perceive apology and compassion responses? Public Relations Review 35: 452–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.07.002.

Chu, K.K., and C.H. Li. 2012. The study of the effects of identity-related judgment, affective identification and continuance commitment on WOM behavior. Quality & Quantity 46 (1): 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-010-9355-3.

Claeys, A.S., and V. Cauberghe. 2014. What makes crisis response strategies work? The impact of crisis involvement and message framing. Journal of Business Research 67 (2): 182–189.

Claeys, A.S., and V. Cauberghe. 2015. The role of a favorable pre-crisis reputation in protecting organizations during crises. Public Relations Review 41 (1): 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.10.013.

Claeys, A., V. Cauberghe, and P. Vyncke. 2010. Restoring reputations in times of crisis: An experimental study of the situational crisis communication theory and the moderating effects of locus of control. Public Relations Review 36: 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.05.004.

Conway, E., N. Fu, K. Monks, K. Alfes, and C. Bailey. 2015. Demands or resources? The relationship between HR practices, employee engagement, and emotional exhaustion within a hybrid model of employment relations. Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21691.

Coombs, W.T. 2004. Impact of past crises on current crisis communication insights from situational crisis communication theory. Journal of business Communication 41 (3): 265–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943604265607.

Coombs, W.T. 2007. Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review 10 (3): 163–176.

Coombs, W.T. 2010. Parameters for crisis communication. In The handbook of crisis communication, ed. W.T. Coombs, and S.J. Holladay, 17–53. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Coombs, W.T. 2014. Crisis communication: A developing field. In Crisis communication, vol. I, ed. W.T. Coombs, 3–18. London: SAGE.

Coombs, W.T. 2015. The value of communication during a crisis: Insights from strategic communication research. Business Horizons 58: 141–148.

Coombs, W.T., and S.J. Holladay. 1996. Communication and attributions in a crisis: An experimental study in crisis communication. Journal of Public Relations Research 8 (4): 279–295.

Coombs, W.T., and S.J. Holladay. 2002. Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Management Communication Quarterly 16 (2): 165–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/089331802237233.

Coombs, W.T., and S.J. Holladay. 2004. Reasoned action in crisis communication: An attribution theory-based approach to crisis management. In. In Responding to crisis: A rhetorical approach to crisis communication, ed. D.P. Millar, and R.L. Heath, 95–115. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Coombs, W.T., and S.J. Holladay. 2005. An exploratory study of stakeholder emotions: Affect and crises. The Effect of Affect in Organizational Settings 1: 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1746-9791(05)01111-9.

Coombs, W.T., and S.J. Holladay. 2006. Unpacking the halo effect: Reputation and crisis management. Journal of Communication Management 10 (2): 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632540610664698.

Coombs, W.T., and S.J. Holladay. 2007. The negative communication dynamic. Exploring the impact of stakeholder affect on behavioral intentions. Journal of Communication Management 11 (4): 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632540710843913.

Coombs, W.T., and S.J. Holladay. 2008. Comparing apology to equivalent crisis response strategies: Clarifying apology’s role and value in crisis communication. Public Relations Review 34: 252–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.04.001.

Coombs, W.T., and S.J. Holladay. 2009. Further explorations of post-crisis communication: Effects of media and response strategies on perceptions and intentions. Public Relations Review 35: 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.09.011.

Coombs, W.T., and S.J. Holladay. 2014. How publics react to crisis communication efforts: Comparing crisis response reactions across sub-arenas. Journal of Communication Management 18 (1): 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-03-2013-0015.

Coombs, W.T., T.A. Fediuk, and S.J. Holladay. 2007. Further explorations of post-crisis communication and stakeholder anger: The negative communication dynamic model. Paper presented at the international public relations research conference.

Dawar, N., and M. Pillutla. 2000. Impact of product-harm crises on brand equity: The moderating role of consumer expectations. Journal of Marketing Research 37: 215–226.

Dean, D.H. 2004. Consumer reaction to negative publicity effects of corporate reputation, response, and responsibility for a crisis event. Journal of Business Communication 41 (2): 192–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943603261748.

Du, S., C.B. Bhattacharya, and S. Sen. 2007. Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. International Journal of Research in Marketing 24 (3): 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2007.01.001.

Dutton, J.E., J.M. Dukerich, and C.V. Harquail. 1994. Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly 39 (2): 239–263.

Einwiller, S.A., A. Fedorikhin, A.R. Johnson, and M.A. Kamins. 2006. Enough is enough! When identification no longer prevents negative corporate associations. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34 (2): 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070305284983.

Etayankara, M., & Bapuji, H. 2009. Product recalls: A review of literature. Paper presented at Administrative Sciences Association of Canada (30), Niagara Falls, Canada.

Folkman, S., and J.T. Moskowitz. 2000. Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist 55 (6): 647–654. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.6.647.

Fombrun, C. 2015. About Volkswagen, reputation, and social responsibility [Blog post]. Retrieved 26 January 2016, from http://blog.reputationinstitute.com/2015/10/07/about-volkswagen-reputation-and-social-responsibility/.

Fombrun, C.J., and C.B.M. van Riel. 2004. Fame & Fortune: How successful companies build winning reputation. New York: Prentice-Hall Financial Times.

Fornell, C., and D.F. Larcker. 1981. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 382–388.

Garcia, T. 2015. Volkswagen’s PR response made problem worse, experts say. MarketWatch. Retrived from https://www.marketwatch.com/story/volkswagens-pr-response-made-problems-worse-experts-say-2015-09-25.

Geier, B. 2015. Everything to know about Volkswagen’s emissions crisis. Fortune. Retrieved from http://fortune.com/2015/09/22/volkswagen-vw-emissions-golf/.

Gibson, D., J.L. Gonzales, and J. Castanon. 2006. The importance of reputation and the role of public relations. Public Relations Quarterly 51 (3): 15–18.

Goyette, I., L. Ricard, J. Bergeron, and F. Marticottte. 2010. e-WOM Scale: Word-of-mouth measurement scale for e-services context. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 27: 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/CJAS.129.

Gruen, R.J., and G. Mendelsohn. 1986. Emotional responses to affective displays in others: The distinction between empathy and sympathy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (3): 609–614.

Grunwald, G., and B. Hempelmann. 2011. Impacts of reputation for quality on perceptions of company responsibility and product-related dangers in times of product-recall and public complaints crises: Results from an empirical investigation. Corporate Reputation Review 13 (4): 264–283. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2010.23.

Harrison-Walker, L.J. 2001. The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. Journal of Service Research 4 (1): 60–75.

Härtel, C.E., J.R. McColl-Kennedy, and L. McDonald. 1998. Incorporating attributional theory and the theory of reasoned action within an affective events theory framework to produce a contingency predictive model of consumer reactions to organizational mishaps. Advances in Consumer Research 25: 428–432.

heise online. 2016. Abgas-Skandal: VW beginnt mit Rückruf – zunächst für das Modell Amarok. Retrieved from http://www.heise.de/newsticker/meldung/Abgas-Skandal-VW-beginnt-mit-Rueckruf-zunaechst-fuer-das-Modell-Amarok-3085837.html.

Hair, J.F., W.C. Black, B.J. Babin, and R.E. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate data analysis, 7th ed. Upper Sadle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Heath, R.L., and W. Douglas. 1990. Involvement: A key variable in people’s reaction to public policy issues. In Public relations research annual, ed. L.A. Grunig, and J.E. Grunig, 193–204. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hennig-Thurau, T., K.P. Gwinner, G. Walsh, and D.D. Gremler. 2004. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing 18 (1): 38–52.

Iyer, A., and J. Oldmeadow. 2006. Picture this: Emotional and political responses to photographs of the Kenneth Bigley kidnapping. European Journal of Social Psychology 36 (5): 635–647. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.316.

Jin, Y. 2009. The effects of public’s cognitive appraisal of emotions in crises on crisis coping and strategy assessment. Public Relations Review 35: 310–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.02.003.

Jin, Y. 2010. Making sense sensibly in crisis communication: How publics’ crisis appraisals influence their negative emotions, coping strategy preferences, and crisis response acceptance. Communication Research 37 (4): 522–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650210368256.

Jin, Y. 2014. Examining publics’ crisis responses according to different shades of anger and sympathy. Journal of Public Relations Research 26 (1): 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2013.848143.

Jin, Y., A. Pang, and G.T. Cameron. 2007. Integrated crisis mapping: Towards a publics-based, emotion-driven conceptualization in crisis communication. Sphera Publica 7 (1): 81–96.

Jin, Y., A. Pang, and G.T. Cameron. 2012. Toward a publics-driven, emotion-based conceptualization in crisis communication: Unearthing dominant emotions in multi-staged testing of the integrated crisis mapping (ICM) model. Journal of Public Relations Research 24: 266–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2012.676747.

Keh, H.T., and Y. Xie. 2009. Corporate reputation and customer behavioral intentions: The roles of trust, identification and commitment. Industrial Marketing Management 38 (7): 732–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.02.005.

Kiambi, D.M., and A. Shafer. 2015. Corporate crisis communication: Examining the interplay of reputation and crisis response strategies. Mass Communication and Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2015.1066013.

Kim, H.J., and G.T. Cameron. 2011. Emotions matter in crisis: The role of anger and sadness in the publics’ response to crisis news framing and corporate crisis response. Communication Research 38 (6): 826–855. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650210385813.

Kim, H.R., M. Lee, H.T. Lee, and N.M. Kim. 2010. Corporate social responsibility and employee-company identification. Journal of Business Ethics 95 (4): 557–569.

Kollewe, J. 2015. Volkswagen emissions scandal—timeline. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/dec/10/volkswagen-emissions-scandal-timeline-events.

Laczniak, R., T. DeCarlo, and S. Ramaswami. 2001. Consumers’ responses to negative word-of-mouth communication: An attributions theory perspective. Journal of Consumer Psychology 11 (1): 57–73.

Laufer, D., and J.M. Jung. 2010. Incorporating regulatory focus theory in product recall communications to increase compliance with a product recall. Public Relations Review 36: 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.03.004.

Laufer, D., and W.T. Coombs. 2006. How should a company respond to a product harm crisis? The role of corporate reputation and consumer-based cues. Business Horizons 49 (5): 379–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2006.01.002.

Laufer, D., and Y. Wang. 2017. Guilty by association: The risk of crisis contagion. Business Horizons. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2017.09.005.

Lee, B.K. 2004. Audience-oriented approach to crisis communication: A study of Hong Kong consumers’ evaluation of an organizational crisis. Communication Research 31 (5): 600–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650204267936.

Leventhal, R.C. 1997. Aging consumers and their effects on the marketplace. Journal of consumer Marketing 14 (4): 276–281.

Liao, H., K. Toya, D.P. Lepak, and Y. Hong. 2009. Do they see eye to eye? Management and employee perspectives of high-performance work systems and influence processes on service quality. Journal of Applied Psychology 94 (2): 371–391.

Lichtenstein, D.R., M.E. Drumwright, and B.M. Braig. 2004. The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. Journal of Marketing 68 (4): 16–32.

Lin, C.P., S.C. Chen, C.K. Chiu, and W.Y. Lee. 2011. Understanding purchase intention during product-harm crises: Moderating effects of perceived corporate ability and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 102 (3): 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/sl0551-011-0824-.

Lindner, E.G. 2006. Emotion and conflict: Why it is important to understand how emotions affect conflict and how conflict affects emotions. In The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice, ed. M. Deutsch, P.T. Coleman, and E. Marcus, 268–293. San Francisco: Wiley.

Luo, X., and C.B. Bhattacharya. 2006. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing 70 (4): 1–18.

Mael, F., and B.E. Ashforth. 1992. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior 13 (2): 103–123.

MacInnis, D.J., A.G. Rao, and A.M. Weiss. 2002. Assessing when increased media weight of real-world advertisements helps sales. Journal of Marketing Research 39 (4): 391–407.

McDonald, L., and C.E. Härtel. 2000. Applying the involvement construct to organisational crises. In Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand marketing academy conference, Gold Coast, Australia.

McDonald, L., A.I. Glendon, and B. Sparks. 2011. Measuring consumers’ emotional reactions to company crises: Scale development and implications. Advances in Consumer Research 39: 333–340.

McDonald, L.M., B. Sparks, and A.I. Glendon. 2010. Stakeholder reactions to company crisis communication and causes. Public Relations Review 36: 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.04.004.

McGee, P. 2017. VW rebounds from crisis as earnings beat forecasts. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/6498a500-2fe5-11e7-9555-23ef563ecf9a.

Nunnally, J.C. 1978. Psychometric Theory, 2d ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pérez, R.C. 2009. Effects of perceived identity based on corporate social responsibility: The role of consumer identification with the company. Corporate Reputation Review 12 (2): 177–191.

Petty, R.E., and J.T. Cacioppo. 1981. Attitudes and persuasion: Classic and contemporary approaches. Dubuque: Wm. C. Brown Company Publishers.

Petty, R.E., and J.T. Cacioppo. 1986. Communication and persuasion. Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer.

Rauwald, C. 2017. VW says it’s ‘back on track’ after restructuring, Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-03-14/vw-recovery-makes-progress-as-namesake-car-brand-s-margins-widen.

Rea, B., Y.J. Wang, and J. Stoner. 2014. When a brand caught fire: The role of brand equity in product-harm crisis. Journal of Product & Brand Management 23 (7): 532–542. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-01-2014-0477.

Reputation Institute. 2013. The global RepTrak® 100: The world’s most reputable companies (2013). RI report on consumer perceptions of companies in 15 Countries [Report]. Retrieved from http://www.reputationinstitute.com/Resources/Registered/PDF-Resources/The-2013-Global-RepTrak®-100-Results-and-Report.aspx.

Reputation Institute. 2014. The global RepTrak® 100: The world’s most reputable companies (2014). RI report on consumer perceptions of companies in 15 countries [Report]. Retrieved from http://www.reputationinstitute.com/Resources/Registered/PDF-Resources/2014-Global-RepTrak-100.aspx.

Reputation Institute. 2015. The global RepTrak® 100: The world’s most reputable companies (2015). RI report on consumer perceptions of companies in 15 countries [Report]. Retrieved from https://www.reputationinstitute.com/Resources/Registered/PDF-Resources/Global-RepTrak-100-2015.aspx.

Rhee, M., and P.R. Haunschild. 2006. The liability of good reputation: A study of product recalls in the US automobile industry. Organization Science 17 (1): 101–117.

Richins, M.L. 1984. Word of mouth communication as negative information. Advances in Consumer Research 11 (1): 697–702.

Roehm, M.L., and A.M. Tybout. 2006. When will a brand scandal spill over, and how should competitors respond? Journal of Marketing Research 43 (3): 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.43.3.366.

Salovey, P., and D.L. Rosenhan. 1989. Mood states and prosocial behaviour. In Handbook of psychology, ed. H. Wagner, and A. Manstead, 371–391. New York: Wiley.

Schultz, F., S. Utz, and A. Göritz. 2011. Is the medium the message? Perceptions of and reactions to crisis communication via twitter, blogs and traditional media. Public Relations Review 37: 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.12.001.

Sen, S., and C.B. Bhattacharya. 2001. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research 38 (2): 225–243.

Silverman, G. 2001. The power of word of mouth. Direct Marketing 64 (5): 47–52.

SoSci Panel für Wissenschaftler. 2015. Retrieved from https://www.soscisurvey.de/panel/researchers.php.

Sohn, Y.J., and R.W. Lariscy. 2015. A “buffer” or “boomerang?”—The role of corporate reputation in bad times. Communication Research 42 (2): 237–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212466891.

Szmigin, I., and M. Carrigan. 2001. Learning to love the older consumer. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 1 (1): 22–34.

Tajfel, H., and J.C. Turner. 1985. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology of intergroup relations, 2nd ed, ed. S. Worchel, and W.G. Austin, 7–24. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

The Guardian. 2016. VW global sales fell 2% in year emissions scandal hit. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jan/08/vw-global-sales-fell-year-emissions-scandal-2015.

Theo, T., L. Ting Tsai, and C.-C. Yang. 2013. Applying structural equation modeling (SEM) in educational research: An introduction. In Application of structural equation modeling in educational research and practice, ed. M.S. Khine, 3–22. Rotterdam, NL: Sense Publishers.

Turk, J.V., Y. Jin, S. Stewart, J. Kim, and J.R. Hipple. 2012. Examining the interplay of an organization’s prior reputation, CEO’s visibility, and immediate response to a crisis. Public Relations Review 38 (4): 574–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.06.012.

Utz, S., F. Schultz, and S. Glocka. 2013. Crisis communication online: How medium, crisis type and emotions affected public reactions in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Public Relations Review 39 (1): 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.09.010.

van Riel, C.B.M., and C.J. Fombrun. 2007. Essentials of corporate communication. New York: Routledge.

Vassilikopoulou, A., G. Siomkos, K. Chatzipanagiotou, and A. Pantouvakis. 2009. Product-harm crisis management: Time heals all wounds? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 16 (3): 174–180.

Verlegh, P.W. 2007. Home country bias in product evaluation: The complementary roles of economic and socio-psychological motives. Journal of International Business Studies 38 (3): 361–373.

Vizard, S. 2015. Why Volkswagen cannot survive the emissions scandal unscathed. Marketing Week. Retrieved from https://www.marketingweek.com/2015/09/24/why-volkswagen-cannot-survive-the-emissions-scandal-unscathed/.

Weiner, B. 1985. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review 92 (4): 548–573.

Weiner, B. 1986. An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. New York: Springer Verlag.

Weiner, B. 2006. Social motivation, justice, and the moral emotions: An attributional approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Weiss, H.M., and R. Cropanzano. 1996. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behaviour 18: 1–74.

Wetzer, I.M., M. Zeelenberg, and R. Pieters. 2007. “Never eat in that restaurant, I did!”: Exploring why people engage in negative word-of-mouth communication. Psychology & Marketing 24 (8): 661–680. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20178.

Wigley, S., and M. Pfau. 2010. Communicating before a crisis: An exploration of bolstering, CSR, and inoculation practices. In The handbook of crisis communication, ed. W.T. Coombs, and S.J. Holladay, 607–634. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Xiao, N., and S. Hwan (Mark) Lee. 2014. Brand identity fit in co-branding: The moderating role of CB identification and consumer coping. European Journal of Marketing 48 (7/8): 1239–1254. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2012-0075.

Yu, T., M. Sengul, and R.H. Lester. 2008. Misery loves company: The spread of negative impacts resulting from an organizational crisis. Academy of Management Review 33 (2): 452–472.

Zaichkowsky, J.L. 1985. Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research 12: 341–352.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Guido Berens, the Editor of Corporate Reputation Review and two “anonymous” reviewers for their valuable feedback. We are also immensely grateful to Prof. Boris Bartikowski and Dr. Daniel Laufer for their constructive comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. Any errors are our own and should not tarnish the reputations of these esteemed scholars.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wanjek, L. How to Fix a Lie? The Formation of Volkswagen’s Post-crisis Reputation Among the German Public. Corp Reputation Rev 21, 84–100 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-018-0045-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-018-0045-8