Abstract

This study examines the effect of FDI openness to China and the rest of the world (ROW) on democracy levels of African countries in the short and long terms. We propose and test the hypothesis that the nexus between FDI openness and democracy is moderated by the grabbing and helping hands of regime corruption of African countries. We argue that in the short run, FDI openness will negatively impact democracy (grabbing hand) in corrupt regimes. However, in the long run there will be a positive effect (helping hand) as the revenue spillovers from the investment projects will reach the society empowering the middle class to demand better institutional qualities. We test these theories with a unique panel dataset spanning 2003–2017. Our dataset includes gravity model and politico-economic variables not only between China and African countries but also between the ROW. Building on examples from the existing research, we test the short-run impacts with dynamic GMM model (Blundell and Bond, J Econ, 87(1):115–143, 1998), whereas we test the long-run relationships with two stage least squares fixed effects models. To account for transaction costs and endogeneity problems, in the first stage we apply instruments on openness to both China and ROW FDI. We find statistically strong yet mixed results for our expectations. While in the short-run corrupt African countries that liberalize to Chinese FDI have lower democracy levels, in the long run, the FDI openness has a positive influence. Our results are robust to alternative measurements of democracy, 3- and 5-year non-overlapping smoothed averages and exclusion of top five countries with FDI openness to China and ROW.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

How does openness to foreign direct investments (FDI) from China and ROW influence democratization in domestic markets of African countries overtime? Why some African countries that obtained high levels of Chinese FDI experienced more democratization than others? The impact of Chinese enterprises on institutions in African continent has been under severe scrutiny from academics and policy experts alike in recent years (Mourao 2018; Chen et al. 2018; Sanfilippo 2010). The scholarly community is divided into two camps on the role of China’s economic presence in Africa. Some scholars suggest that China deliberately selects states with weak governance in order to make a swift entrance into the local economic sectors of resource rich countries (Alden and Alves 2008; Bodomo 2009; Adolph et al. 2017). As a counterargument, other scholars propose that Chinese FDI investments have advanced the infrastructural development, manufacturing in different industries, and economic growth in Africa (Whalley and Weisbrod 2012; Amighini and Sanfilippo 2014; NguyenHuu and Schwiebert 2019). Some even suggest that healthy business environments and stable institutions are major motivators for Chinese FDI in African countries (Borojo and Yushi 2020).

Local institutions in the destination country are decisive for attracting or discouraging foreign capital as some investors enter offshore markets having higher demands for stable and efficient socio-political foundations than others (Bailey 2018; Alence 2004). The previous research examining the relationship between institutions and FDI demonstrates that developing countries which have a better democratic political process (Busse et al. 2016), low inflation (Farazmand and Moradi 2014), economic growth (Acquah and Ibrahim 2020), low corruption (Gossel 2018), ongoing institutional reforms (Malikane and Chitambara 2017), availability of local resources for productive markets (Pinto and Zhu 2016), rich natural resources (Shan et al. 2018) and significant human development (Reiter and Steensma 2010) attract larger inflows of foreign capital from China and other economic partners.

The research investigating how Chinese investments shape democratization in African countries in the long and short terms remains limited. The economic activities by Chinese investors in African countries have drawn a widescale attention from the global community. Chinese investments in the capital and production markets of African countries have grown substantially in the recent decades as China continues to stretch its powerful economic wings (Eisenman 2012; Broich 2017). The existing empirical studies exploring China’s foreign direct investments in Africa offer conflicting theoretical expectations for the effects of FDI on democratic development. Some show that resources and market potentials are important determinants of Chinese investments in African states (Shan et al. 2018; Pinto and Zhu 2016; Sanfilippo 2010; Pinto and Zhu 2016). The abundance of natural resources like oil and copper and large markets for agricultural goods and services production can further deepen the resource curse in Africa delaying democratization. This problem could worsen if Chinese state sponsored and independent investors approach African markets by proposing weak regulatory policies that can produce additional adverse effects on the society (Humphrey and Michaelowa 2019). Other scholars suggest that Chinese economic cooperation projects can lower the costs for improving the internal and external infrastructure in Africa (NguyenHuu and Schwiebert 2019; Busse et al. 2016). The persistent corruption in many African countries serves as an impediment for much needed economic growth from foreign investments (Quazi et al. 2014) as those investments increase in states with strong institutional capacity (Gossel 2018).

Since the lack of accountability and institutions for checks and balances as well as the presence of pervasive corruption all hamper economic prosperity from foreign investments (Bougharriou et al. 2019), there are variations in long- and short-term temporal effects on democracy that are critical for more systematic investigation (Dinh et al. 2019). This paper aims to fill the gap in the growing research focusing on the impact of Chinese FDI openness in Africa while controlling for openness to other investment partners. We present a theory which hypothesizes that liberalization to Chinese FDI will yield different long- and short-term effects on democracy in African countries with various levels of corruption. Our main argument is that the effect that openness to FDI makes on democratic institutions is moderated by regime corruption. As such, following some related theoretical frameworks designed by Gossel (2018), Mourao (2018), Quazi et al. (2014), Bak and Moon (2016) and Borojo and Yushi (2020) who explore various relationships between FDI openness/flows/stocks and institutional qualities, we argue that openness to foreign investments will allow for more inclusionary politics and property rights protection hence more democratization over the years. As such, we theorize that in the short run, the democratic institutions will suffer from the potential exploitation of foreign capital from China and elsewhere to Africa by local elites who receive and manage those investments. However, in the long run, we expect African countries to experience more democratization as the society will benefit from spillovers of investment projects.

To closely model the anticipated mitigating impact of regime corruption within the FDI openness and democracy nexus we refer to two prominent and competing hypotheses, the grabbing hand and helping hand. The grabbing hand hypotheses suggests that the uncertainty surrounding corruption increases the costs of investments for foreign firms (Quazi et al. 2014). While the helping hand hypothesis proposes that fraudulent tactics such as bribery, relaxed labor taxes, and low market entry barriers serve as a helping hand to make a swift route for foreign investors into local markets of recipient countries (Gossel 2018). The empirically supported conclusions regarding these hypotheses are largely inconclusive with scholars providing some evidence in both directions at different levels of corruption (Egger and Winner 2005).

Unlike the previous studies that view these theories as conflicting, we argue that there is an inter-related association between the two. We argue that strategic yet corrupt entrepreneurs in domestic markets will utilize the advantages of the helping hand of corruption to allure investments (Fredriksson et al. 2003). Nevertheless, the properties of the grabbing hand of corruption will become more prevalent when they extract more rents by exploiting foreign capital for personal use (Marquette and Peiffer 2018). The latter tactic, as our framework and results reveal, is more harmful for the democratization in African countries.

The novelty of our theoretical approach is twofold. First, unlike some existing works in this field of research we argue that operating through FDI’s impact, the short-term effects of market openness will produce negative effects on democracy. This outcome itself will validate the presence of the grabbing hand influences of corruption in domestic investment markets in the short term. Yet, in the long run, the effects of FDI openness on democracy will become positive because once the foreign investors get used to corrupt methods in foreign destinations and realize that those practices do not harm their potential to accumulate wealth, they will become complacent and invest more. The research shows that high levels of investments are positively associated with democratization (Moon 2019; Bak and Moon 2016). Second, we suggest that the effects of the grabbing and helping hands of corruption work in cycles. As illustrated in Table 1, we theorize that when the grabbing hand aspects are present then FDI openness has short- and long-term negative effects on democracy. However, we notice that when the helping hand features are at work the short- and long-run effects are positive. By contrast, the grabbing hand theory will be prevalent.

With the theoretical framework developed in this paper, we also aim to examine whether the arguments criticizing China’s “no strings attached” economic cooperation in African countries with weak institutions have any empirical basis for validation. To probe the key assumptions of our theory, we build on existing studies from Quazi et al. (2014), Bak and Moon (2016), Malikane and Chitambara (2017), Gossel (2018) (Mourao, 2018), Henri et al. (2019), Dinh et al. (2019) and Kucera and Principi (2014) and design static and dynamic models which examine the long- and short-run effects of Chinese FDI on democracy levels in Africa, respectively. The static models testing the long-term trends of democratic transition employ two-stage least-squares (2SLS) regression approach. In the first stage, we account for transaction costs and endogeneity problems by instrumenting the Chinese FDI openness and openness to the rest of the world (ROW) with traditional gravity model variables such as distance, landlock and common language (Borojo and Yushi 2020; Subasat and Bellos 2013; Bellos and Subasat 2012a, b). Following (López-Córdova and Meissner 2008), in the second stage we use the predicted values of instrumented economic variables to investigate their impact on our unique measure of democracy. To tease out the influence of FDI openness on democracy that is due to changing levels of corruption, we employ interaction terms between Chinese or ROW FDI openness and regime corruption index. To inspect the short-term effects, we follow Henri et al. (2019), Gossel (2018), and Quazi et al. (2014) and use system generalized method of moments (GMM) approach to build models that include both contemporaneous and lagged values of democracy index and FDI openness. We also include the interaction terms in our dynamic models.

Using an unbalanced panel data over the period 2003–2017 for 48 African countries in our observed sample, we find mixed results on how investment liberalizations to China and ROW influence democratization in African countries with different levels of corruption in long and short run. The results in main models where the dependent variable is a composite democracy index from the Varieties of Democracy show that, after accounting for exogenous causes, when corrupt African regimes liberalize to Chinese FDI the democracy decreases in the long run which is against our hypothesized direction. However, as we expect there is a negative short-run relationship between democracy and Chinese FDI openness in African countries with high levels of corruption. Regarding the FDI openness to ROW, we find that in the long run the impact on democracy is positive as we hypothesized. The impact is still negative in the short run which is contrary to our expectations.

An important finding delivered by our results is that the effects of FDI openness highly vary depending on the measurement, operationalization and sources of the dependent variable, the democracy. For example, our robustness analysis reveals that while Chinese FDI openness negatively impacts some variables of democratic indices, it has a positive effect on others. Additionally, following Quazi et al. (2014), we check for the unit root and address its presence by making it stationary in some of the explanatory variables in order to bypass inaccurate estimations that could be driven by random noise in our stochastic process. To save space, more details on the procedures and methodological techniques we took for tackling this issue are outlined in Supplementary Materials of this article that are available online.

This article proceeds as follows. The first section reviews the existing empirical literature on short- and long-term relationships between FDI, corruption, institutions and democracy. In this section, we also discuss China’s investments in Africa as well as the role of corruption in African countries for attracting FDI. The second section introduces the theoretical motivation behind the analytical framework surrounding the divergent relationship between FDI and democracy in Africa in long and short terms. This section also produces testable hypotheses derived from the main conceptual framework. “Research design and econometric models” section presents and describes the research design and econometrics models. This section also describes the data for main dependent and independent variables by interpreting some descriptive statistics. Also, in “Research design and econometric models” section, we discuss the instrument validity and explain study limitations. Section 4 discusses the main econometric outcomes of the static (long-term) and dynamic (short-term) models. “Robustness analysis” section defines the robustness check strategies and estimation procedures and presents explanation on the results of those estimations. “Discussion and implications of findings” section discusses the magnitude and implications of our key findings. “Policy recommendations and future research” section offers policy recommendations and suggests improvements for future research. Lastly, we conclude by summarizing the contributions of this article.

Review and Discussion of the Literature

In this section, we outline the main empirical and theoretical studies that investigate the importance of FDI on promoting democracy, as well as the reverse causation between the two as identified in the literature. Then, we survey the existing studies on Chinese investments in African countries and their repercussions on institutional development. Tables 16 and 17 in “Appendix” present the synthesis of methodologies and major findings in relevant empirical research. As we notice, most studies in this field examine the effects of institutional and governance qualities on some measure of FDI in different parts of the world. Unlike those approaches, we attempt to elucidate how openness to foreign investment from China and ROW in corrupt African countries shape democratization in the short and long terms.

Democratization has many endogenous and exogenous influences and distortions (Acemoglu et al. 2019). A rich body of scholarly works have shown significant and positive association between economic activities such as FDI and democratization.Footnote 1 Scholars have also identified foreign investments as a major factor for fostering economic growth that causes improvements in political institutions vital for democratization (Guha et al. 2020). Yet, the mechanism between FDI and democratization is complicated by the existence of pervasive institutional corruption (Freckleton et al. 2012). Developing countries with low levels of corruption and high levels of democracy receive more foreign capital than those where institutional corruption is prevalent (Ay et al. 2016). However, this view is challenged by some works which find that corruption and low institutional development do not discourage the presence of foreign investors in domestic markets. The investors are presented with opportunities to capture low rates on investments and high rates on capital returns (Resnick, 2001).

In this paper, we are interested in analyzing how unilateral FDI inflows from China and ROW change the levels of democratization in African countries overtime. Additionally, we focus on the macroeconomic role of pervasive corruption which as we argue produces different dynamic effects on the outcome of interest. Hence, while surveying the major works on FDI, institutions and democratization, we pay a close attention to how the presence of corruption may alter the short- and long-term impact of investments on democracy.

FDI, Institutions and Democracy

There is an important literature on the influence of FDI on institutional qualities and democratization or failure thereof (Lacroix et al. 2021; Ross 2019; Van Bergeijk and Brakman 2010; Busse and Hefeker 2007; Resnick 2001). However, the existing works are at odds with each other regarding which institutions are the most effective for capturing foreign investments. Factors that have been identified for attracting more FDI in democracies relate to democratic institutions’ ability to lower the costs associated with high level of regime corruption (Guha et al. 2020).Footnote 2 In democracies, investors rely on credible commitment of stable governance (Guerin and Manzocchi 2009; Yang 2007; Busse and Hefeker 2007). Democracies attract more FDI than autocracies because they offer affordable tax rates on investments and stable property rights protection for foreign investors (Dorsch et al. 2014). Foreign investors prefer government regimes where economic policy outcomes are easy to predict and have strong checks and balances which prevent expropriation of revenues from foreign assets by corrupt elites (Li and Resnick 2003; Gastanaga et al. 1998). Dietrich (2013) argues that countries with weak governance and poor institutional qualities are less likely to receive foreign investments. Hence, democratization may be stalled in societies where lack of economic growth from foreign capital generates institutional instabilities.Footnote 3

By contrast, some studies like Resnick (2001) find that democracy has a negative impact on FDI. Foreign capital in its turn promotes poor governance in Latin American countries that were already plagued with corruption (Subasat and Bellos 2013). A few recent studies examined variations of FDI while looking at differences in political institutions of autocratic or hybrid regimes (Bermeo 2016; Bak and Moon 2016; Moon 2019). In contrast to Dietrich (2013), Bellos and Subasat (2012a) design a gravity model between recipient and donor countries to show that instead of discouraging FDI the lack of good governance in transition economies is not an obstacle for alluring more investments. Similar to their results, using two-stage regression analysis Bak and Moon (2016) show that FDI can prolong the authoritarian durability by strengthening the long-term survival of regime elites in office. The elites use capital from abroad to pay the loyal agents, assuage possible escalation of challenges by the opposition and create FDI centered distributional coalitions for political parties. In a related work, Moon (2019) argues that autocratic countries which masquerade under democratic institutional structures such as elected legislatures attract more FDI than those without democratic features. The elected legislature provides transparency and credibility for multinational corporations to protect foreign interests in domestic markets.

Motivating Facts: Short- and Long-Term Links of FDI, Corruption and Democracy

A growing empirical research has tested temporal (short and long run) properties of FDI produced on institutional transformation leading to economic growth and democratization (Kahouli and Maktouf 2015; Gossel 2018; Li and Resnick 2003). Most studies in this line of research have relied on a prominent tool, System Generalized Method of Moments (SGMM), developed by Arellano and Bond (1991) to examine the short-run dynamic effects of foreign investments. Others have employed a gravity model of FDI to assess the relationship between governance qualities, institutions and foreign investments (Borojo and Yushi 2020; Kahouli and Maktouf 2015; Bellos and Subasat 2012a,b; Guerin and Manzocchi 2009; Talamo 2007). An earlier work by Feng (1997) develops a theoretical framework for diverging long- and short-run effects of economic growth and democracy. The results of multi-stage regression analysis reveal that economic growth has a positive long-run, however, negative short-run impact on prosperity of democracy. The econometric analysis by Yang (2007) employs OLS, seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) and Arellano–Bond system GMM methods for short-run effects to study the relationship between FDI and political regimes. The results from a panel data of 134 countries between 1983 and 2002 suggest that while the relationship between democracy and FDI in levels and FDI as ratio of GDP is insignificant, being a democratic regime is positively associated with high levels of FDI. Another study using dynamic short-run models by Aziz and Mishra (2016) finds that Arab countries with stable institutions attract more FDI in general. Others find that developing countries with significant corruption which achieved high economic growth rate receive more FDI than those with low economic growth Guha et al. (2020).

The Grabbing and Helping Hands of Regime Corruption

Finally, the macroeconomic impact of FDI on democracy in developing countries has been analyzed from the perspective of two related but competing hypotheses, the helping hand and the grabbing hand. The helping hand hypothesis suggests that corrupt governments of host countries may use bribing methods to appeal foreign investors eager to enter their markets (Quazi et al. 2014). Those methods may include relaxing the taxes on labor, materials, and lowering the wages for manufacturing (Gastanaga et al. 1998). Contrary to the helping hand hypothesis, the grabbing hand theory suggests that bribes initiated by corrupt regime elites may increase the risks associated with contracts on investments, property rights, and asset capital.

A prominent study by Gossel (2018) examines the interrelation between FDI, democracy and corruption in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries by probing empirical implications of these two conflicting hypotheses. Using the GMM estimation, this study finds that foreign investors who are keen on investing in specific SSA countries leverage the opportunities to obtain lower rates on spending and higher rates on revenue returns. This suggests that the implications of the helping hand hypothesis are more applicable within the context of SSA countries’ governance styles. However, the study concludes that in the long run the helping hand aspects of the regime corruption become grabbing hand motivations and increase the democratic capital. In other words, corrupt African regimes receiving FDI improve their democratic regulatory and institutional qualities.

Similarly, Quazi (2014) uses generalized least squares estimation to analyze the impact of corruption on FDI in East Asian and South Asian countries from 1995 to 2011. In contrast to (Gossel 2018), this author finds that the grabbing hand of corruption is more dominant in those parts of the world as the results reveal a robust and negative effect of corruption on FDI flows. However, when investigating the association between corruption and FDI in African countries with GMM models, Quazi et al. (2014) find support for the helping hand hypothesis.

Sino-African Economic Relations: Issues and Recent Developments

With the exception of few studies that have investigated the Sino-African economic activities (Broich 2017; Malikane and Chitambara 2017; Asiedu and Lien 2011), most research on the nexus between Chinese investments and democracy is limited, particularly in the context of Africa. In this paper, we attempt to provide new insights on how the openness to investment flows from China to African countries influences levels of democratization of the host economies in the short and long terms.

Several factors make the Sino-African economic relations important for systematic empirical examination. First, China is increasingly becoming one of the most influential capital donors in Africa (NguyenHuu and Schwiebert 2019). The investigation of Sino-African economic relations becomes significant because Africa includes the most countries with lowest levels of freedom, institutional stability, income equality, pervasive corruption and employment (Arezki and Gylfason 2013). Yet, the quantitative research that evaluates the democratic outcomes influenced by Chinese capital flows to Africa is scant.Footnote 4 Second, empirical research that analyzes repercussions of Chinese investments on democratization in Africa is limited and does not account for potential endogeneity problems between FDI and democracy. Third, while studies that investigate Chinese investments in Africa are increasing, to the best of our knowledge the unobserved impact of investments from the rest of the world has not been introduced in empirical models in most of those studies. Our empirical exercise revisits all these gaps in the research by conducting logarithmic 2SLS regression analysis where in the first stage we use a gravity model of FDI to control for potential endogeneity bias and transaction costs.

China’s Investments in African Countries

China’s growing economic engagement in Africa has raised many alarms among academics and policy practitioners. At the core of these alarms lies the argument that China’s economic presence in Africa demands “no preconditions” for cooperation from institutionally unstable African countries (Chen et al. 2018; Huiping 2013; Edoho 2011; Meidan 2006; Sautman and Hairong 2009). Yet, empirical research examining how Chinese investments impact democracy in African countries in the short and long term is scarce. A recent work by Borojo and Yushi (2020) develops a gravity model of FDI with pseudo-Poisson maximum likelihood regression to analyze how institutional qualities and business environments motivate Chinese investments in African countries. The results indicate that African countries with better institutional structures and business opportunities are more likely to receive FDI from China than those countries lacking such environments.

In a related prominent study, Mourao (2018) examines Chinese FDI in Africa for 44 African countries between 2003 and 2010 relying on stochastic frontier models. The results show that Chinese investment destinations are determined by the presence of dynamic national markets with significant population size and extensive forest areas. The author derives efficiency scores for each African country based on political institutions. Particularly, countries with higher levels of political stability and regulatory quality receive more Chinese FDI. Other authors find that although China has a substantial role in African development finance, it does not resemble a “game changing” presence due to lack of economic progress in many African countries (Humphrey and Michaelowa 2019). This outcome can be attributed to China’s perception of African economies as supply sources for raw material and energy to fill in the gaps of shortages in China’s growing industries and markets. Other empirical studies reach inconclusive results regarding how Chinese investments shape mechanisms of institutional development and economic growth in African countries.

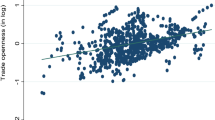

Similar to our approach, some previous studies have focused on the mitigating role of institutional conditions for inviting more FDI separately from China and the rest of the world countries (Fan et al. 2009). Chinese FDI and ROW FDI may distinctly influence democratization in Africa for various reasons. First, when investigating the impact of economic activities on democracy, it is important to control for the total magnitude of those activities. Although our primary objective is to analyze how openness to Chinese investments shapes democratization in African countries, the analysis would be incomplete and would yield inconsistent outcomes if we ignore the presence of investments from elsewhere. Second, while policymakers observe global investment trends concentrating on the bigger picture of continents like Latin America, Africa and Central America, as shown in Figure 1, there are some differences in the levels of openness to FDI from China and ROW that African countries with different government qualities have. Third, as opposed to dividing the investments to African countries by only its three or more sources, we only explore the consequences on democracy impacted by Chinese and ROW investments. The reason for this is the data availability from other big partners. For example, the UNCTAD reports include investment flows, however, for most big partner countries those country level reports have many missing values for the year-range that the data on Chinese investments are available from CAIR (2019) source.Footnote 5 Lastly, Chinese and ROW FDI openness may differently effect democracy in African countries since some countries in Africa are more welcoming of non-Chinese firms than those entering from China (Knutsen and Kotsadam 2020).

Previous works find preconditions in the causal relationship between democracy and Chinese FDI in Africa. Broich (2017) controls for political, institutional, strategic, economic and geographic factors to show that Chinese development finance does not systematically target authoritarian African countries with weak institutions. Using a large panel data of 112 countries between the years 1982–2007, Asiedu and Lien (2011) show that democratic countries are more likely to emerge as recipients of FDI when the share of minerals and oils in total exports is below a specific threshold. Additionally, they find that the magnitude of democracy’s impact on FDI is strongly determined by the size instead of the type of a natural resources considered. Malikane and Chitambara (2017) show a positive association between FDI inflows, economic growth and democracy-building in some African countries. After applying the GMM model on a panel of 18 Southern African countries between 1980 and 2014, the authors present evidence for a positive linkage between FDI and economic growth. The authors attribute this effect to the levels of democracy in the sample of countries. This finding is significant because as suggested by Malikane and Chitambara, the Southern African countries with durable democratic institutions are more likely to capture the positive outcomes derived from incoming FDI compared to those countries with poor democratic governance.

Corruption and Short- and Long-Term Impact of Chinese FDI on Democracy in African States

Few studies show that developing countries especially in Africa with weak institutions and corruption attract more foreign investments from China and elsewhere (Jalil et al. 2016; Bellos and Subasat 2012a; Kolstad and Wiig 2011; Egger and Winner 2005). We claim this outcome can be explained by the argument that the rent-seeking behavior from local politicians in many African countries hampers a positive institutional transformation. In addition, the political survival of autocrats in resource-rich countries like DRC, Zimbabwe and Mali contributes to exploitation of foreign capital for redistribution of goods and services to beneficiaries of elites in power. The lack of impetus from China to improve the political process of host countries further exacerbates opportunities for bureaucratic transformation that could promise changes in the societies of various weak African states. As such, Sino-African economic relations are unbalanced and asymmetrically relying mostly on two aspects: (1) successful completion of investment projects by African entrepreneurs and (2) revenue returns for Chinese investors. This behavior generates harmful practices against unfairly compensated labor force which encounters limited opportunities for growth.

Both theoretical and empirical studies on Chinese economic investments in African countries inform about two overarching frameworks. The first line of argument suggests that Chinese investments in Africa create substantial improvements in infrastructural sectors helping to alleviate poverty and decrease income inequality (NguyenHuu and Schwiebert 2019). Some factors contributing to poverty and inequality mitigation in Africa are tied to Chinese FDI’s ability to diversify low-technology industries and generate better quality manufacturing exports (Amighini and Sanfilippo 2014). The second line of argument states that China’s investments in Africa raise alarming concerns because capital inflows tend to be mismanaged by the rent-seeking bureaucrats and politicians in African economies with weak state capacity (Edoho 2011; Lynch and Crawford 2011; Eisenman 2012; Arezki and Gylfason 2013; Brautigam 2015; Swedlund 2017). Some scholars argue that China deliberately selects states with weak governance in order to make a swift entrance into the local economic sectors of resource abundant African countries (Alden and Alves 2008; Bodomo 2009). While China inarguably is becoming a heavyweight in the global trade and investment competition, many democracies of the Western world claim that China conducts economic activities within poorly governed countries by ignoring the violations of human rights and social liberties of the local governments toward their own population (Adolph et al. 2017).

These two predominant views explain different narratives of democratization in Africa. The growth of production heavy economies significantly relies on labor-intensive industries which have high- and low-skill sectors. When the production markets liberalize in developing countries, the high-skill labor force also gains traction. As demonstrated by the Heckscher–Ohlin theorem and interrelated Stolper–Samuelson model, an increase in high-skill labor motivates improvement in institutions that empower the middle class (Levchenko 2007). However, the definition of skill sectors varies across developed and developing countries as what qualifies as a low skill in a developed state may be considered a high skill in a developing state (Bogliaccini and Egan 2017). For the large-scale manufacturing sectors of goods and services to maintain momentum, foreign investment inflows are necessary to sustain factors of production. Thus, the country’s relative endowments such as labor and capital will define its comparative advantage. China, which has both capital and labor resources, is economically more developed than an African country like Cameroon which could very well be on the path of economic development with vast natural resources in addition to some labor and/or capital abundance.

Liberalization to capital inflows from China and other countries can bring prospects for domestic progress for both democratically weak and strong African states. When capital abundant partners like China, the USA, Russia and European Union enter a region with rich natural resources, the resulting economic cooperation expands the workforce for production of labor-intensive goods. Improvement of labor force will promote a growing working class which can have a more central role in the political process. Democratization will prosper in countries where the workers are able to profit from capital-intensive markets. A more stable working middle class will emerge as the number of beneficiaries from liberal investment policies increase. And finally, the flexible foreign capital investment in infrastructural projects will lead to democratization with the expansion of the wealthier middle class (Acemoglu et al. 2019; Persson and Tabellini 2009).

Theoretical Motivation

An important hypothesis that has received minimal attention in the quantitative literature is that there may be a tradeoff between FDI liberalization and democratization. We argue that pervasive corruption may hinder democratization in the short term as dishonest entrepreneurs exploit profits from foreign investments to distribute rents (Fredriksson et al. 2003). However, in the long run, the society accumulates enough resources from those investments (Kucera and Principi 2014) that stable participation in the democratic process becomes possible (Kurer et al. 2019). Rent-seeking institutions in the African continent have increased as a result of pervasive corruption in recent decades (Gossel 2018; Mathur and Singh 2013). Foreign investors pay close attention to the corruption in the host economies. Yet, this does not indicate that they are discouraged by ongoing corruptible practices. Moreover, an experimental research study on Chinese firms investing abroad shows that arbitrary corruption instead of predictable corruption allows more frequent entry to foreign markets (Zhu and Shi 2019).

The predictability of corruption divides the scholarly community into two camps with contrasting views. The proponents of the helping hand hypothesis suggest that predictable regime corruption greases the wheels of rent extracting machinery by offering foreign investors low tax rates on investment and labor wages (Marquette and Peiffer 2018). The contrasting hypothesis is labeled as the gabbing hand which suggests that corruption puts “sands in the wheels” instead of greasing them by discouraging foreign investors to take the gamble on transferring capital to governments with high risks of expropriation and fraudulence (Cheung et al. 2010). Quazi et al. (2014) investigate the empirical implications of these competing hypotheses on FDI in Africa. Using system GMM estimation, they find that in the short run corruption promotes high levels of FDI in Africa which provides support for the helping hand hypothesis. Gossel (2018) also presents empirical support for the helping hand hypothesis and shows that foreign investors leverage their opportunities for sealing deals with low costs by ignoring the corruption.

Analytical Framework

While the macroeconomic impact of foreign investments on democratization is well studied, the association between these two factors within countries with different levels of corruption remains a subject of academic debate. The novel contribution of our analytical framework is that, as opposed to the previous research, we do not disaggregate the influence of corruption into only one of the two types, helping hand or grabbing hand. Moreover, we argue that the impact of corruption on attracting FDI and FDI’s subsequent impact on democracy works differently in the long and short runs.

Our analytical agenda is twofold. First, we combine the logic from both the helping-hand and the grabbing-hand hypotheses with the analytical framework of Heckscher–Ohlin theorem and Stolper–Samuelson (HOSS) model. In a nutshell, the HOSS assumes that higher extent of economic activities such as liberalization to foreign capital investments and trade will empower the middle class. This will allow for greater accountability from the elites, strengthen labor and property rights protections and generate institutions conducive for democratization (Knutsen 2011). We are interested in testing the assumptions regarding the short- and long-term impact of FDI on democratization. This will provide new insights about whether corruption in African countries serves as a helping hand or a grabbing hand for attracting FDI from China.

Second, we aim to understand whether there are any regularities that allow to shed a better light on debates whether China’s economic activities in Africa have an overall positive or negative effect on democratization. We identify the following nexus on how openness to Chinese and ROW FDI will influence democratization in African countries. In societies with pervasive corruption, democratization will become a gradual process because FDI has exploitable rents that the dishonest entrepreneurs can seize in the short run. Borrowing from Gossel (2018), we theorize that exploitability of FDI revenues makes the assumptions of the grabbing hand hypothesis more relevant in the short run. When FDI revenues serve the economic welfare of the few in power, the benefits of the society are undermined (Acemoglu 2008). The appropriation of welfare may increase social unrest and economic grievances and promote corruption. These factors hinder democratization in the short run, for instance, within several years.

Yet, revenues extracted from foreign investments may still make their way to the society to benefit certain sectors that are crucial for improving democratic institutions (Persson and Tabellini 2009; Acemoglu et al. 2008). Henceforth, the properties of the helping hand hypothesis become more visible in the long run as the entrepreneurs in various regime types redistribute rents to the winning coalition in order to prolong their time in office (De Mesquita and Smith 2011, 2010; De Mesquita et al. 2005). Put simply, in the long run the cumulative effect of multi-year investments will positively influence democratization as the labor force will sustain productivity despite of expropriation of foreign investments in the short term. African countries will benefit from FDI openness in the long run as inflows can motivate better economic integration in the society. An efficient economic process triggered by global capital flows will redesign the redistribution of resources, property rights, and social values while moving the political equilibrium towards democratic values. As such, we hypothesize the following relationship between openness to FDI and democracy:

H1 Ceteris paribus:

As African countries with pervasive corruption become more open to Chinese FDI inflows, the levels of democracy will increase (decrease) within and across African countries in the long run (short run).

After controlling for other country characteristics, we can expect a similar trajectory for the relationship between the foreign investments streaming from ROW to African countries in the observed sample of countries.

H2 Ceteris paribus:

As African countries with pervasive corruption become more open to FDI inflows from ROW, the levels of democracy will increase (decrease) within and across African countries in the long run (short run).

Table 1 summarizes our hypothesized direction of FDI openness on democracy levels in African countries. As illustrated in the Panel 1 of this table which demonstrates our main expectations, we expect that democracy prospects will decrease in the short term when African countries with significant levels of corruption liberalize to FDI from China and ROW. This outcome will make the characteristics of the grabbing hand hypothesis more relevant in this context as corruption will amplify regulatory inefficiencies, transaction, and reputational costs for foreign investors (Quazi et al. 2014). Nevertheless, in the long run the effects of the helping hand of corruption may produce positive outcomes on democratization because the regime elites would need to satisfy the demands and grievances of their constituency in order to avoid threats to the regime stability.

By contrast, if contrary to our expectation the short-term effects from FDI openness on democracy are positive instead of negative as we expect, then the characteristics of the helping hand are more visible as shown by Panel 2. The logic for this expectation is that the grabbing hand of corruption may hinder the emergence of democratization since the investors become more discouraged in uncertain business climates. Yet, the helping hand of corruption may increase investments to contribute for development of institutional qualities that can promote democratization. In other words, the novelty of our framework is that we postulate that instead of viewing them as separate influences, the scholarly community should consider the grabbing and the helping hands of corruption in conjunction as one hand complements the other.

Research Design and Econometric Models

We analyze the impact of FDI openness to China and ROW on democracy in African countries moderated by regime corruption. As such, we include interaction terms in our models to gauge the influence of changes in FDI openness that is due to changes in regime corruption on democracy index, the outcome variable of interest.Footnote 6 Our research design is similar to that of Gossel (2018) and Quazi et al. (2014), as we likewise attempt to test the implications of the grabbing hand and the helping hand hypotheses in the context of FDI market liberalization in African countries. However, we move a step further by disaggregating sources of FDI to Africa, namely those coming from China and ROW. Our panel is unbalanced and includes 48 countries spanning from 2003 to 2017. The sample of countries is determined by the availability of FDI data from China to African countries. We obtain this data from China-Africa Research Initiative (CAIR, 2019). As argued by Humphrey and Michaelowa (2019), the information offered by the CAIR is one of the few comprehensive options given the absence of reliable data from Chinese authorities (p. 18).

Following the methodological structure in several of studies outlined in Lacroix et al. (2021), Culver (2021), Moon (2019), Bak and Moon (2016), Pinto and Zhu (2016), Kahouli and Maktouf (2015), and Pandya (2014) that explored the association between economic activities and democratization, we design a two-stage least-squares estimation to evaluate how FDI openness affects democracy in African countries in the long and short run. In the first stage, we use a gravity model of FDI openness to China and ROW from African countries to account for the costs of economic activities (Borojo and Yushi 2020) and endogeneity between democracy and FDI in the second stage regression (Bellos and Subasat 2012b). Second, we employ the predicted values of FDI openness from the first stage in the second stage where we regress the fitted values on our unique democracy index. Additionally, given the panel nature of our dataset, we control for country and year fixed effects—confounders that can potentially influence democracy. For both the first and second stages of our analysis, we include country, year or two-way fixed effects to isolate static differences per country and control for time constant omitted effects. To examine the short-run effects, we design a GMM model similar to Blundell and Bond (1998) to tease out the impact of both contemporaneous and previous values of the dependent and independent variables on trends of democratization in our sample of African countries.

Data

The descriptive statistics on all the variables are presented in Table 5 of “Appendix A.” Correlation figures in a cross-tabular format are also included in the same appendix.

Dependent Variable

The main dependent variable is the democracy index extracted from Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset (Coppedge et al. 2020). We produced this unique measure by averaging the five variables quantifying different levels of democracy available in the V-Dem: electoral democracy, liberal democracy, participatory democracy, deliberative democracy, and egalitarian democracy scores. The democracy index is a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 1 with lowest values assuming less democratic and higher values more democratic regimes. We estimate the level of democratization as the change from year \(t_{1}\), \(t_{2}\)…\(t_{n}\) for a sample of 48 African countries for 15 years per country with missing years for some countries that had no FDI data available.

The left panel in Figure 1 shows that African countries with autocratic as well as democratic institutions became more open to trade with China than the ROW. The right panel in this figure reveals that Chinese investment in African states surpassed that of ROW only after 2011. One explanation can be that after the Arab Spring the risky political climate in countries such as Angola, Egypt, Morocco, Libya, Sudan and Tunisia as major recipients of ROW investments became uncertain. Meanwhile, the FDI from China has not experienced those apparent post-Arab Spring declines at the same level as FDI from ROW. Therefore, for the purpose of this paper, it is important to account for the effect of FDI from China and ROW on democracy levels both within and across African countries overtime.

The mixed evidence on many determinants of democracy that reach inconclusive results and various democracy measures tested in this field of research serve as strong basis for implementing alternative measures of democratic indices in our models. For those reasons, building on previous studies such as (Lacroix et al. 2021; Guha et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2018; Bak and Moon 2016; Pandya 2014; Morrissey and Udomkerdmongkol 2012; Busse and Hefeker 2007; Egger and Winner 2005; Asiedu and Lien 2011; Resnick 2001) we employ the following measurements of democracy in the robustness analysis. First, we normalize the combined democracy scores from Polity V project that range from -10 for least democratic to +10 for most democratic societies. After normalization this variable ranges from 0 to 1 where lower values indicate less democratic and higher values indicate more democratic polities. Second, we similarly normalize two measures of governance conditions, 1) voice and accountability (VA) and 2) rule of law (RL) measures obtained from the World Bank’s Governance Indicators (GI) data sources.

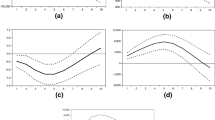

The GI includes 7 measures of governance qualities from a global sample of countries. However, we employ only two of those indicators because as shown in Figure 4 in “Appendix A,” only VA and RL had a low Pearson correlation (0.42) compared to other variables. Lastly, we introduce the political rights (PR) and civil liberties (CL) ratings from the Freedom House database. These measures range from 1 to 7 where higher values suggest more stable protection of citizens’ rights and liberties. We likewise normalize these components to range from 0 to 1 for ease of interpretation of results in comparison to the other indices. Figure 5 in “Appendix A” illustrates the annual averages of all democracy indices that we use in addition to other GI indicators. We notice that there is a great amount of variation across VA, RL, CL, PR, POLITY and V-Dem’s democracy index, the latter of which our main outcome of interest to generate larger variation between democratically stable and unstable countries which liberalize to foreign capital. All aforementioned variables that measure democracy were also extracted from the V-Dem data source which has gathered, stored and organized the original data (Coppedge et al. 2020).

Independent Variables

The main independent variables of interest are the stock FDI openness of African countries to China and ROW. The FDI stocks (in $US millions) from China to an African country i (i = 1, …N) at year t (t = 1,…T) are from China-Africa Research Initiative (CAIR 2019). While some previous studies like Mathur and Singh (2013), Bailey (2018), Gastanaga et al. (1998) and Li and Resnick (2003) have used FDI flows in their empirical analysis, yet, we follow the suggestion from Bak and Moon (2016), Pinto and Zhu (2016) and Kahouli and Maktouf (2015) to use the stock values in order to account for political implications of commercial activities by multinational organizations. The FDI stock flows (in $US millions) from the ROW to an African country i and time t is the difference between FDI inflows from the world and FDI inflows from China. The data on FDI from the world to African countries is extracted from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD 2019). We obtain this measure as follows:

As is standard in the literature, the FDI openness is calculated by dividing the total inflows by gross domestic product of each African country i and time t (Asiedu and Lien, 2011).

All measurements for the ROW variables we calculated by using top commercial partners of African countries excluding China. The top partners in our sample include countries such as Belgium, Brazil, Great Britain, Germany, France, India, Indonesia, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia, United States, Turkey, and Spain.

Figure 2 shows the average level of regime corruption mapped for each African country in our sample and summarized by the market size (GDP per capita) and FDI openness to China and ROW. A noteworthy depiction that these maps present is that as we notice the island-countries like Seychelles, Cabo Verde, and Mauritius have substantially larger foreign investment liberalization to China and ROW than other big economies with larger markets and populations in Africa. One inference that we can draw from this illustration is that it will be important to conduct a sensitivity analysis by isolating small islands that have abnormally larger FDI openness relative to their population size and land area. Another inference is that those small islands still play an important role in understanding how institutional factors become central drivers of foreign investments as Seychelles, Mauritius and Cape Verde are one of the most developed island countries with constitutions that secure representative democracy for their respective citizens. Therefore, before excluding them from the main sample, our primary objective will be to have as comprehensive of a sample of African countries as possible. Thus, we include small islands in the main econometric exercise.

Instrumental (Gravity Model) Variables for the First Stage Regression

Most studies summarized in this paper have been concerned with the impact of institutional qualities on fostering foreign investments. Several of those studies such as Borojo and Yushi (2020), Bellos and Subasat (2012a), Subasat and Bellos (2013), Kahouli and Maktouf (2015), and Bellos and Subasat (2012b) implement a gravity model of FDI to account for any potential transaction costs. The aforementioned authors agree that FDI is endogenous to political institutions of recipient countries. Yet, there might exist a reverse causation between democratization and capacity to attract foreign investments. To account for possible spurious estimation and endogeneity Bak and Moon (2016) construct a unique instrument for FDI. Their approach capitalizes on Pinto and Zhu (2016) who construct an inverse weighted measure of distance between two economic partners.Footnote 7

Borrowing from this example, we calculate the inverse weighted distance between each African country i and China or ROW. Instead of including the GDP as a distinct instrument, we compute the GDP weighted inverse distance. We obtain the data on the distance from the Centre d’Études Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (CEPII) (Head and Mayer 2014). The bilateral distance is an average between producers and consumers of major cities within each African country in our sample relative to China and ROW. For the ROW, we extract the absolute values of distance for top commercial partners of African countries mentioned earlier and compute the average for all of them. Then we calculate the inverse distance weighted by the average GDP of each African country i at year t.Footnote 8

The data for other instrumental variables such as bilateral membership in World Trade Organization (WTO) for each African country with China or ROW, their distance from China, and whether an African country is landlocked or has access to a sea/ocean are also from (CEPII) (Head and Mayer 2014). Using examples from Gossel (2018), Malikane and Chitambara (2017), Aziz and Mishra (2016), Jalil et al. (2016) and Yang (2007) we add the trade openness to the world (including China and ROW) measured as the ratio between exports and imports divided by GDP of each African country in a given year as our fourth instrumental variable. The aforementioned research provides significant empirical evidence for both linear and nonlinear relationship between FDI and trade openness. We likewise expect that trade openness to the World instead of separately for China and ROW will have an overall impact on the extent of FDI stocks from China and ROW to African countries. The reason for this claim is that wealthier economies are more likely to attract more investments in the long run (Busse and Hefeker 2007). We provide more details and explanation for the instrument validity, study limitations and other specification in section 3.2.

Other Control Variables

The prior literature informs that the effect of FDI on democratization depends on several factors, including recipient country’s level of regime corruption (Egger and Winner 2005), market size scaled as GDP per capita (Aziz and Mishra 2016; Mathur and Singh 2013), and property rights (Chen et al. 2018; Li and Resnick 2003). We include these explanatory factors as additional controls in the second stage regression for both long- and short-term models. The regime corruption and property rights are from the Varieties of Democracy (Coppedge et al. 2020). These are continuous variables ranging between 0 and 1 with 0 indicating the lowest level and 1 the highest level for each scale. The regime corruption gauges the clientelistic behavior of politicians in systems of neopatrimonial rule who use their offices for private and/or political gain. Neopatrimonialism is interpreted as a regime where in social hierarchical environment patrons or principles use state resources and power to obtain loyalty from clients or agents in the society. The private property is not concerned with actual ownership of property. The conceptualization of this variable rather comprises rights such as acquiring, possessing, inheriting, and selling private property including land (Coppedge et al. 2020). The boundaries on property rights may be set by the government/state which can censor those rights or fail to enforce them (Acemoglu 2008). The restrictions on property rights may also come from customary laws and practices, religious or social norms (Li and Resnick 2003).

Instrument Validity, Limitations of Study and Other Specifications

Specifications for Instrument Validity

Several scholars have suggested that to properly control for observed and unobserved confounding factors in 2SLS analysis it is necessary to find valid instruments for explanatory variables that are correlated with the idiosyncratic error term (Lacroix et al. 2021; Kahouli and Maktouf 2015; Pinto and Zhu 2016; Bak and Moon 2016; Pandya 2014). To satisfy the proposed validity, the instrument(s) should possess a few properties. First, conceptually, the instrument must affect the main dependent variable through its statistically significant correlation only with other explanatory variables and not be directly correlated with the dependent variable e.g. Z impacts Y only through its effect on X (Goldsmith 2021). Second, it should have low or no correlation with unobserved factors (Bak and Moon 2016).

We conduct several tests for the validity of our instruments which are the bilateral inverse distance between a given African country and China or ROW, bilateral membership in WTO, and whether or not both ROW or China and African country i have access to a major coastline. First, our validity test in the long-run models is based on the Stock and Yogo (2002) who measure the strength of multiple instruments simultaneously relying on maximum allowable bias relative to OLS, and maximum size of the Wald test. We rely on the Wald test size estimation as it is based on Cragg and Donald (1993) which provides more efficient estimation procedure for a model with multiple endogenous variables. The null hypothesis is that instruments are weak. The Stock-Yogo test for instrument validity obtains the Cragg–Donald statistic for weak instruments and compares it to a critical value.Footnote 9 This is particularly applicable to our models which include interaction terms between FDI openness and regime corruption, the market size, and property rights.

As such, we test for weak instruments in the first stage separately for when the dependent variable is the FDI openness to China and FDI openness to ROW. When the dependent variable is Chinese FDI openness, we use the weighted inverse distance to China. In the case of ROW FDI openness we substitute this instrument with the equivalent for ROW. The Cragg–Donald statistic for weak instruments given the Chinese FDI openness as the first stage dependent variable is 79.26 which is higher than the critical value of 16.85 at α = 0.05 level, so we have sufficient statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis that instruments are weak. Similarly, for ROW FDI openness as the main dependent variable in the first stage the statistic is 41.96 which is higher than the critical value of 16.85 at α = 0.05 level, which allows us to confirm the strength of instruments.Footnote 10

Second, for the dynamic short-run models we report the Sargan test \({\upchi }^{2}\) values and p-test statistics for overidentification, the Wald test \({\upchi }^{2}\) values and p-test statistics for weak instruments, and AR(1) and AR(2) p-values for first and second order auto-correlated disturbances in the first-differenced equations in the GMM models. As shown by these test statistics, for the dynamic models we also reject the null hypothesis for overidentification, weak instruments and autocorrelation in the second order (AR2). As the results reveal in subsequent sections, the instruments for the dynamic models satisfy the conditions of validity based on all these specifications.Footnote 11

Limitations

As it is the case with most studies in this line of research, the current paper also has its weaknesses which we discuss in this section. First, there is a sampling bias in the data. In other words, the sample of countries in our data frame is not representative of the entire African continent. Our sample includes only 48 out of 54 African countries. The biggest factor for this sampling selection issue is the availability of foreign investment data from China to African countries which we were able to obtain only for 48 economic partners. However, the number of African countries in our analysis is dictated by the type of research problem we are investigating. Our main goal is to test the impact of openness to Chinese foreign capital on democratization in African countries in the short and long run while controlling for investment openness from elsewhere. To accomplish this task, we make a compromise to have less units in our analysis. Yet, biased sample size does not imply a small sample size that is inappropriate to use in statistical estimations. Our sample size consists of 48 countries spanning 11–15 years (2003–2017) which provides enough depth for both long and short term within country analysis.

The previous studies that estimated dynamic models to examine the relationship between institutional qualities and economic activities claim that both system and difference GMM approaches are reliable methods for addressing short-term endogenous impact and heterogeneity of covariates (Kahouli and Maktouf 2015; Egger and Winner 2005). Yet, others warn about several limitations that the GMM technique presents (Jalil et al. 2016; Kucera and Principi 2014). The GMM procedure can be unstable, and the predicted coefficients may depend on characteristics of the selected sample or be difficult to directly interpret (Kathavate and Mallik 2012). Next, the GMM estimator may be a weak approach to deal with serial correlation issues even when including the lagged variables (Henri et al. 2019). Additionally, it is difficult to find appropriate GMM instruments to some endogenous independent variables in cases when only weak instruments are available (Aziz and Mishra 2016). The latter problem is not pressing for our study as the GMM statistics reveal that our instruments are not weak, and there are no issues of overidentification in all dynamic models presented in Table 3.

Unit Root Analysis

In both short- and long-term empirical models, we transform variables from level to logarithm because as the panel unit root analysis revealed, all variables had a unit root at the level but had not unit root present after the transformation. To save space, we provide detailed discussion on comprehensive panel unit root checks conducted for this study in the supplementary materials document which are available online.

Static (Long Run) and Dynamic (Short Run) Models

Static/Long-Term Model

Our primary objective is to test the short- and long-run impacts of two hypotheses that the previous research has found to be competing, the grabbing hand and helping hand of corruption on facilitating foreign investments which shape host countries’ institutions. With this in mind, we theorize that the effect of FDI openness on democratization depends on the host country’s level of regime corruption. In countries with high levels of corruption that liberalize to foreign investments, the effect on democratization will be negative in the short run, and positive in the long run. The negative short-run outcome on democracy is expected due to prevalent opportunities for elites in corrupt regimes for rent creation and appropriation. However, institutional advancement will still become possible as those elites need to maintain loyal base of selectorate to prolong time in office (Knutsen and Kotsadam 2020). Consequently, the revenue spillovers from foreign investments will positively influence prospects of democratization as the society will obtain means for political participation, voting and civic engagement in the long run.

To accurately proxy for diverging short- and long-run relationships between FDI openness and democracy moderated by regime corruption, we include interaction terms in our models (Maruta et al. 2020). We design a two-stage least-squares (2SLS) estimation to gauge the long-term effect of FDI openness on democracy. In the first stage, following a large body of research on determinants of FDI (Maruta et al. 2020; Broich 2017; Subasat and Bellos 2013; Kahouli and Maktouf 2015; Bak and Moon 2016; Moon 2019; Pinto and Zhu 2016) we instrument the openness to FDI from China and ROW in African countries by the inverse distance, trade openness, WTO membership and landlocked variables. The 2SLS design enables to account for endogeneity between FDI openness and democratization (Pandya 2014). The endogeneity may bias the regression outcomes as FDI openness will be highly correlated with the idiosyncratic component (Broich 2017). As such, closely following the suggestions from Borojo and Yushi (2020), Kahouli and Maktouf (2015) and Subasat and Bellos (2013) to address possible endogeneity biases in this empirical analysis with gravity-type instruments, our first-stage model consists of the following components. We delegate the more in-depth discussion of gravity model and econometric intuition behind its theory to Methodology “Appendix B.”

Static/Long-run, first-stage gravity-type model:

where \(Ln\left( {\hat{X}_{i,t}^{n} } \right)\) is the predicted level of FDI openness in African country i at time t which based on the subscript n can be toward China or ROW. The vector \(Ln\left( {Z_{i,t}^{n} } \right)\) contains the main instruments that we apply in this model such as the weighted inverse distance, WTO membership, landlocked and trade openness. The subscript n stands for China or ROW for weighted inverse distance and WTO membership variables. The term \({\upalpha }_{i}\) is time invariant individual (country) level effect, the fixed year effect is accounted by \({\updelta }_{t}\) which is time specific, and \(\mu_{i, t}\) is the idiosyncratic error term. We estimate three different fixed effects models where we include either country, year or two-way fixed effects.

Static/Long-run, second-stage model:

In the second stage, we include the first-stage predicted levels of FDI openness to China and ROW in conjunction with interaction to the regime corruption. In this framework, the term \(Ln\left( {{\text{D}}_{i, t} } \right)\) is the outcome variable of interest which is the democracy index from V-Dem, the unique measure we construct for this study. The interaction term \(\left( {\left( {\hat{X}_{i,t}^{n} } \right) \times Ln\left( {C_{i,t} } \right)} \right)\) consists of the predicted levels of FDI openness to n = {China or ROW} and regime corruption \(Ln\left( {C_{i,t} } \right)\) in the logarithmic form. The coefficient for \({\upbeta }_{3}\) is the main parameter we are interested to estimate as this will allow to proxy for our theory that there are different short- and long-term impacts of FDI openness on democracy that operate through changing levels of corruption. The vector \(Ln\left( {V_{i,t} } \right)\) comprises of our two main control variables, the market size measured by GDP per capita and property rights, both in logarithmic form. The terms \({\upalpha }_{i}\), \({\updelta }_{t}\) and \(\mu_{i, t}\) are unchanged.

Dynamic/Short-Term Model

There are two main sources that motivate the dynamic model framework for short-term effects of FDI on democracy. The first motivation is theoretical. The basis for designing a dynamic environment to examine the relationship between FDI liberalization and democracy is to discover whether our expectation that—high levels of regime corruption hinder allocation of fiscal resources for institutional development necessary for democratization—have any empirical justification in the short term. The results will help us to offer new insights for the existence or prevalence of influences caused by the grabbing hand or helping hand of corruption via FDI liberalization on democratization in African countries. The results will also enable to provide empirically justified conclusions on academic debates for whether or not Chinese investments are favorable to African countries with weak institutions in the short term. Second, we build on numerous previous studies which have argued that there is an important short-term association between foreign investment and institutional factors (Gossel 2018; Malikane and Chitambara 2017; Aziz and Mishra 2016; Busse et al. 2016; Kahouli and Maktouf 2015; Kucera and Principi 2014; Quazi et al. 2014; Asiedu and Lien 2011).

We develop dynamic generalized method of moments (GMM) model proposed by Blundell and Bond (1998). As the empirical literature informs, the sizes of cross sections (N = 699) and time periods (T = 15) of our panel dataset are suitable for constructing dynamic models (Kahouli and Maktouf 2015; Roodman 2009). This empirical approach is appropriate to apply because in the cross-sectional type of panel where models pool data overtime concerns of simultaneity between two (or more variables) can still arise. The system GMM model allows to maintain the sample size in the presence of panel gaps.Footnote 12 Similar to another popular GMM estimation, the Arellano–Bond differenced model, the system GMM also employs internal instruments derived by previous observations of instrumented covariates (Roodman 2009).Footnote 13 The system GMM improves the traditional Arellano–Bond dynamic model by exploiting both differences and levels when fitting the model. That advantage allows to examine the country level characteristics that could temporally alter the levels of democracy while accounting for simultaneity and common trends. In sum, we estimate an individual effect two-step system GMM where the dynamics of cross-sectional variations are investigated by considering the persistence of FDI openness along with rising democracy levels in some African countries. The subsequent setup illustrates the dynamic model:

Dynamic/Short-run model:

In this model, ∆ stands for the difference between a given variable in year t and t − 1, \(Ln(D_{i, t} )\) is the democracy index in a logarithmic form, \(Ln(D_{i, t - j} )\) is the lagged dependent variable with first and second lags p =2, \(Ln\left( {(X^{n} \times C} \right)_{i, t - m} )\) is the interaction term between regime corruption and Chinese FDI openness or ROW FDI openness described earlier, with both contemporaneous values and maximum of one lag per variable, \(Ln\left( {V_{i,t} } \right)\) is a vector of control variables property rights and market size that we included previously, and finally, \({\upalpha }_{i}\) is the indicator for the individual effect, p and q indicate the number of lags for covariates, and \(\mu_{i, t}\) is the country and year specific error term. We formulate a system generalized method of moments model with lagged variables to gauge slow-paced properties of democratic transition. As some authors suggest, the existence of democratic practices is driven by the state institutions that preserved those practices in the past (Persson and Tabellini, 2009). We include up to two lags of the democracy index in the system-GMM model to account for this possibility. Additionally, we allow all lags of the democracy index variable beginning with year t − 2 as a GMM excluded instrument.Footnote 14 Finally, we also include the trade openness, inverse distance to China and inverse distance to ROW as GMM instruments.

Main Econometric Outcomes

The main quantitative objective of this research is to test whether the long- and short-term effects of FDI openness on democratization are due to regime corruption in African countries. This in its turn allows us to clarify implications of two competing hypotheses, the grabbing hand and the helping hand of corruption. We hypothesize that in the long run FDI liberalization to China and ROW will positively effect democratization in societies with increasing regime corruption. In the short run, we expect that this effect will be negative in the short run because corrupt elites will be able to expropriate investment revenues faster than from other sources of wealth. We proceed with the discussion of the second-stage results as the first stage regression outcomes are not part of the main hypotheses.Footnote 15 We then turn to interpreting the statistical importance and influence of estimated levels of FDI openness to China and ROW on democracy in African countries in the short term. More detailed discussion on implications of all our results, their relevance to prior studies and their meaning in a wider context are presented in sections 5 and 6.

Static (Long Run) Results

We follow much of the existing research in this area by reporting the basic linear relationships between our variables in the OLS models where we iteratively include interaction terms as well as the main controls, property rights and market size. Table 2 reports the results of the second-stage static models for the long-run relationship between democracy index and our key variables of interest, the interaction terms of FDI openness to China/ROW and regime corruption.

First, the results in model 1 suggest that we do not find an empirical support for our baseline assumption that as African countries become liberalized to Chinese FDI in the long run, the democratization will increase. Contrariwise, similar to Subasat and Bellos (2013) and Bellos and Subasat (2012b) all of whom analyze a sample of Latin American countries, we find a statistically significant negative relationship between FDI openness on democratization in our sample of African countries. Particularly, the results show that a one unit increase in the predicted level of Chinese FDI openness (in the first stage) is associated with -5.7 percent (100×(−0.057))% decrease in the democracy index.Footnote 16 The direction of this effect does not change in the model 2 where we include the openness to FDI from ROW. We find that democracy index level decreases by 13.9% for every unit increase in the ROW FDI openness variable at a 10 percent significance level.

These baseline results do not directly test the major assumptions of hypotheses 1 and 2. To properly examine the long-term changes in the democracy levels of African countries when liberalizing to foreign investments from China and ROW, we add interaction terms with regime corruption in each country i at year t. The models 3, 4 and 5 yield standard errors clustered by country, year and two-way (country and year) levels. The significant F-statistic values in all models of Table 2 reveal that these regression estimations have strong fit for the independent variables that explain the democracy levels. They also suggest that the models explain substantial variation in the outcome of interest for this study.

Model 3 reports some contrasting outcomes given the predicted coefficients for the interaction terms. First, we observe that Chinese FDI openness that is due to increasing levels of regime corruption has negative effect on the democracy in the long run. Yet, this outcome has no statistical significance. We discover statistically significant support for our second hypothesis in the estimated coefficient of interaction between ROW FDI openness and regime corruption. The result indicates that as FDI openness to ROW increases by 1% in African countries with high level of regime corruption democracy index increases by 0.38%.Footnote 17 This result suggests that when African countries with high regime corruption liberalize to investments from the ROW, the investments coming from Chinese partners have insignificant influence on wealth redistribution trends. In other words, similar to arguments and findings in Chen et al. (2018) we also document that as opposed to alternative investment options, most African countries with tougher socio-political environments seek foreign capital from China, whereas those with relatively stable institutional environment liberalize to FDI from ROW.