Abstract

Various macro-shocks arguably affect the demand for populism. However, there is no evidence beyond a few case studies. I expand electoral data on left- and right-wing populism and link them with per capita income, inflation, unemployment, government expenditures, income inequality, migration, trade and financial openness, and natural resource rents. Negative shocks in some of those consistently predict a surge in populist votes, even in the presence of inherent populist cycles. Shocks also affect election outcomes of left-wing and right-wing populists differently. Finally, European and Latin American voters are still different, yet converging, in their post-crisis preferences for populism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Roots of Populism

This paper studies the economic roots of populism in 49 European and Latin American countries since 1980. In political science populism is defined as a “communication style,” a discourse, which tries to be as close to the people but at the same time takes an anti-establishment stance and excludes “specific population segments” from an image of an ideal society (Jagers and Walgrave 2007, p. 475). Typically, populists are extreme right or extreme left parties or leaders who fight against the elite political and corporate establishment (Dalio et al. 2017; Hawkins 2009), emphasizing the us-against-them rhetoric.

Economists define populism as an “...approach to economics that emphasizes growth and income distribution and deemphasizes the risks of inflation and deficit finance, external constraints and the reaction of economic agents to aggressive non-market policies” (Dornbusch and Edwards 1990, p. 247). Dalio et al. (2017, p. 2) specify a typical set of those policies in the period after the Great Depression: protectionism, nationalism, increased infrastructure building, increased military spending, greater budget deficits, and capital controls. They find that the causes and evolution of populism across those episodes are so similar that they follow an almost identical pattern. This pattern is described as “populist playbook” by Dalio et al. (2017) and “populist paradigm” by Dornbusch and Edwards (1990). Dornbusch and Edwards (1990) infer that populism ultimately leads to welfare deterioration for most voters initially favoring populist leaders or parties.

If history indeed suggests that large groups of people are made worse-off for supporting parties elected to make them richer, then we need a more systematic understanding of the reasons people vote for populists. The literature offers several explanations.

First, the depth of a recession affects the likelihood of populist insurgence in Europe and Latin America (Dornbusch and Edwards 1991; Moffitt 2015). Research on Asia has also shown a significant effect of crises on the likelihood of populism. For example, Tejapira (2002) and Hewison (2005) review the rise of economic nationalism in Thailand as a result of economic stagnation which followed the 1997 East-Asian crisis. As the post-crisis reforms created a vast number of losers, economic freedom reforms were rejected in the 2001 elections, creating a far more nationalistic political agenda fitting well into the “populist paradigm.” Therefore, Greskovits (1993) contends that to make populism less likely, all reform packages need to contain an adequate compensation mechanism for the reform losers. If the group of losers is large enough, this would inevitably surface as mounting social discontent which will meet with the supply of populist agendas.

Second, normally any reasonable government would create compensation mechanisms to counter-act the persistent unemployment during or after a deep recession. However, the fiscal stance after the Great Recession is different than in previous recessions. Unlike before, governments now need to curb government expenditures exactly when voters need them most because of the high existing levels of government debt. As a result, austerity has been fueling a sense of disenfranchisement among voters.

Third, persistent inequality, combined with stagnant growth or outright economic depression, stands at the heart of social discontent which motivates the supply of populist agendas, according to Dornbusch and Edwards (1990) and Kaufman and Stallings (1991). To arrive at this conclusion, both teams review an array of populist episodes in Latin America. Dornbusch and Edwards (1991) argue that “populist regimes have historically tried to deal with income inequality problems through the use of overly expansive macroeconomic policies.” Macroeconomic mismanagement, however, leads to recessions and banking and fiscal crises, which ensued hyperinflation episodes. In turn, this worsened inequality rather than remedy it, thereby hurting the very people who elected populists. Kaufman and Stallings (1991) also predict that populism would become a more isolated political phenomenon, a conclusion which definitely calls for a revision a decade after the Great Recession.

In fact, even before the Great Recession it was apparent that populism is coming back to prominence in Latin America as a result of persistent income inequality and stagnant growth in the presence of market-oriented reforms (Roberts 2007). Leon (2014) also argues that the use of macroeconomic redistribution to alleviate income inequality may make populist agendas more likely, and Dornbusch and Edwards (1990) add that large-scale redistribution proposals are a persistent feature of populism in Latin America.

Populism has also emerged in other regions of the world. Some countries in Europe are already embracing populist agendas like they used to after the Great Depression (Dalio et al. 2017). Unlike elsewhere, the European brand of populism has a distinctive trait: xenophobia. For a number of years now, and even before the Great Recession, various authors have studied the nascent comeback of populism to the European political scene. According to Jones (2007, p. 37), populists “are making headway across Europe and from all points on the political spectrum”, and a distinctive trait of this comeback is its “xenophobic, anti-immigrant rhetoric”.

The reasons for this rhetoric are outlined also by Cahill (2007). He asserts that the immigration waves from “North Africa and Eastern Europe, fear of economic dislocations under European Union enlargement, and the struggles to integrate Muslim immigrants have breathed new life into anti-immigration platforms” (p. 79). Therefore, these platforms may appeal to the large masses of people experiencing discontent from the consequences of austerity, persistent unemployment and stagnant growth in Europe. As a result, the fourth driving factor behind populism is the “migration issue”, i.e., how large is the inflow of foreign-born population in a given country.

Fifth, various types of globalization shocks such as increased migration, trade openness, and capital account liberalization have been outlined in the recent study of the populist drivers by Rodrik (2017). Increased trade participation and the alleged export of jobs to cheap labor locations have also played well into the populist rhetoric at times of persistently high unemployment or underemployment. For example, a significant part of the Make America Great Again platform appeal to a large mass of working class voters was based on bringing those allegedly lost jobs back to the USA.

Sixth, it has long been established that natural resource rents produce dictator regimes (Sachs and Warner 1999, among others). Some of those regimes are populist. The recent literature has linked the natural resource abundance with populist support (Matsen et al. 2016; Mazzuca 2013).

The above literature suggests eight major factors for the rise of populism across the globe: recessions, inflation, unemployment, austerity, income inequality, immigration, trade and financial openness, and natural resource abundance. The analysis below tests if any of those has played a statistically significant role for populist insurgences. However, first we need a way to measure populism.

Measuring Populism

Recent efforts have generated two data sets that can be used to measure populism and understand its political economy. By using and updating the original index of Hawkins (2009), Rode and Revuelta (2015) design a non-partisan measure of populism as a rhetorical style and study its effect on economic freedom in 33 countries. The advantage of their data set is that it tracks populism in both developed and developing countries across the globe. However, its within-country time variation is small. The index contains 252 observations, of which 55 are after 2007. It is important to note that the Rode and Revuelta (2015) data are generated by studying incumbent political leaders’ speeches. Therefore, these data monitor the rhetorical style of the current political incumbents. Yet, most of the populists, especially in Europe, have been thus far a part of the political fringe. Then, we need richer data to understand what drives populism to political prominence. A more recent data set produced by Heinö (2016) overcomes this constraint.

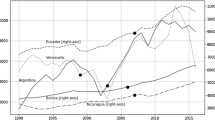

Heinö (2016) monitors actual national election outcomes in 33 European countries since 1980 to track the rise of European populism. He labels a certain party as left-wing or right-wing populist based on the party’s ideology. As there is no single authoritative source on party ideology, information was taken from various sources, including existing political party databases and parties’ own websites.Footnote 1 Then, for each country he sums up the political support for each type of populism, including the period after the recent crisis. The data allow for studying both the overall populism dynamics, as well as the underlying trends in right-wing and left-wing populist support. This makes the index particularly suitable for empirical scrutiny, indicated by the rising number of articles using the underlying data.Footnote 2 The surge of the post-crisis populist appeal makes studying the economic drivers behind populism an even more timely exercise.

The Rode and Revuelta (2015) rhetoric populism data vary little over time, and the Heinö (2016) election outcomes data cover only Europe. As a result, we still lack a more comprehensive perspective on the rise of populism. This calls for an additional empirical effort. This effort is directed at both increasing time coverage, especially with more observations after the crisis, and expanding the geographic coverage beyond Europe. This is needed because populism has been slowly moving from the local political fringe to global prominence, especially after 2016 Brexit and US elections. Therefore, to adequately understand the political economy of populism, we need broader data.

By applying the Heinö (2016) approach to Latin America, my research assistant and I expanded the populism index. We looked at actual election outcomes for pre-defined left-wing and right-wing populist parties in 16 Latin American countries since 1980 and added additional 546 observations to the Heinö (2016) data. As a rule of thumb, far-left or Marxist-Leninist parties were labeled left-wing populists, and far-right parties were labeled right-wing populists. To increase within-country time variation for Latin America, we added information on electoral support on both parliamentary and presidential elections. If both happen in the same year in a given country, the average of the two results was taken for each party. The electoral support data were sourced from Nohlen (2005), and for later periods—from electionguide.org.

As a result, our populism data set includes a total of 49 countries and 1586 observations since 1980, which makes it the largest data set of populist support to date. The data set monitors populism on an annual basis, and populist appeal between elections is assumed constant. However, for the empirical estimations that follow, we take only the country-time observations with actual elections. Thus, 436 observations remain in the expanded populism data set.

I link this data set with the above explanatory factors. Data on per capita income, inflation, unemployment, government expenditures in GDP, trade openness, and natural resource rents are taken from the World Development Indicators (World Bank 2017). Data on inequality dynamics, i.e., Gini coefficient and income ratios, are taken from UNU-WIDER (2017)—a richer data set than previously used Milanovic (2014). Whenever there was more than one observation for a given country-year in the original UNU-WIDER (2017) data due to multiple sources, the average of those observations was used.

Data on the stock of migration used in the benchmark model are taken from United Nations (2017a), and data on net migration are taken from United Nations (2017b). The former includes the percentage of foreign-born populationFootnote 3 at a certain point in time, while the latter features the net number of migrants (immigrants minus emigrants) per 1000 population in each country. The United Nations (2017a) data set covers migrants from 1990 to 2017 at 5 year intervals, while the United Nations (2017b) data span from 1950 to 2015 at 5 year intervals. Within each of the 5-year periods, migration was assumed constant. This is done because data at annual frequencies are available only for the OECD countries (OECD 2017), which is not a match good enough for the countries in the extended populism sample. At the same time, the World Bank (2017) bilateral migration data vary at 10-year frequencies. Thus, the 5-year data strike a relatively good balance: at the expense of a smaller time variation than the OECD (2017) data, it gains a larger country coverage. Details on the estimation methods follow.

Model

To estimate how populist support at both ends of the political spectrum relates to macroeconomic shocks, I estimate the following model in differences:

where \(POP_{it}\) is either the total electoral support (POP), or the support for left-wing (LW) or right-wing (RW) populist parties. For each country i and election year t, \(X_{it}\) contains the following: Log(GDP/c.), CPI inflation, unemployment, government expenditures in GDP, Gini coefficient, trade openness, natural resource rents, the stock of migration, and an interaction of those with an after-crisis dummy (AC) to estimate if populism is driven by those factors differently before and after the Great Recession. The AC dummy is equal to 1 if the year is greater than 2008, and equal to 0 otherwise. The model includes also country- and time-fixed effects, and standard errors (SE) are clustered at the country level. Per capita GDP is preferred in this case over the underlying GDP for one important reason: it is voter preferences that drive election outcomes, and the median voter sentiment would be much better proxied by the per capita GDP than the actual GDP.

Difference estimation is needed for at least two reasons. First, a major concern for the benchmark model—especially if run in levels—is the possible non-stationarity of the variables on both sides of the equation. If those variables are non-stationary, the correlations and statistical significances reported may be artificially increased. To check for stationarity, I run a number of panel data unit root tests. The Levin–Lin–Chu, the Im–Pesaran–Shin, and the Fisher-type tests reject non-stationarity in all populism variables, measured in levels. However, the Breitung and the Harris-Tzavalis tests cannot reject it. Further, the Hadri LM test rejects that all populism panels are stationary. All tests cannot reject stationarity of the differenced populism data. Therefore, there is a need to run the model in differences. Second, we are looking into how macro-shocks affect populist dynamics, not just if poorer and more unequal societies vote for populists more often. Then, for both econometric and intuitive reasons, we need the model estimated in differences with country- and time-fixed effects and clustered standard errors (SE).

Clustering at the country level, however, provides consistent SE estimates only in the presence of a large number of clusters. With the relatively small number of countries here, there are two ways to proceed: (1) employ the cluster-adjusted T-Statistics (CATs) procedure suggested by Cameron et al. (2008) and extended for practical purposes by Ibragimov and Müller (2010) and Esarey and Menger (2018); (2) employ a difference GMM approach a la Arellano and Bond (1991), which deals with serial correlation within clusters in the presence of populism dynamics.

Results from the CATs procedure are presented in Table 1, while results from the one-step robust difference GMM model are presented in Table 2. As significant multicollinearity could be observed between some of the explanatory variables, the models are also run separately for each of the variables in \(X_{it}\). Results from the separate estimations are presented in Table 3. A detailed discussion of the results follows.

Results

The results in Table 1 are presented in three sets of estimates, each containing three columns. The first set presents the results for the entire sample of countries. The second and the third sets represent separate estimates for Europe and Latin America, respectively. Within each set, column (1) uses the total populist support (TP) as the dependent variable, and columns (2) and (3) display the results for left-wing populism (LW), and right-wing populism (RW) separately. The results allow for comparing what drives populism before and after the Great Recession, and for analyzing any differences in those drivers between Europe and Latin America.

The lagged-dependent variables are indeed significant in most estimations, and they are negatively correlated with the changes in populist acclaim. This means countries that have gone through a rise of populism in past elections are more likely to vote away from the political extremes in the current elections, and vice versa. This result supports evidence of cycles of populism within each country over time, as modeled by Dovis et al. (2016), and documented earlier by Roberts (2007) and Ocampo (2015). Those cycles of populism are also less evident in Latin America than in Europe.

All estimates demonstrate that declines in income per capita are rarely associated with a significant increase in populist support. The exception is left-wing populism in Europe, which has the expected negative correlation with recessions. A rise in inflation and unemployment, a higher trade participation, and a greater immigration flows are also not the core drivers of populist insurgencies.

Austerity plays a different role for right-wing and left-wing populism. Countries with heavier fiscal contractions in Europe are more likely to experience a surge in left-wing populism. Overall, fiscal contractions also significantly reduce the demand for right-wing populist agendas.

However, right-wing populism seems unaffected by income inequality. A rise in the Gini coefficient plays a significant role only for voters in Latin America, and only for left-wing populists. Apparently, Latin American voters are more sensitive to spreading inequalities than Europeans, perhaps due to more tolerable existing levels of inequality in Europe and broader coverage of the European social safety nets. In addition, inequality does not play a significant role in how differently voters perceive populism before and after the Great Recession. That is not the case for natural resource endowments.

Countries accumulating natural resources also experience a burgeoning populist support. This is evident from the parameter estimates of Rents and is hardly surprising. Typically, resource-rich countries use the proceeds to buy political support through either infrastructure development or direct social transfers, consistent with the “populist paradigm.” It is notable that no significant differences emerge between Europe and Latin America in terms of how voters perceive higher endowments.

The parameter estimates on the interaction terms with an after-crisis dummy (AC) add further insight into the political economy of populism after 2008. Overall, the after-crisis sensitivity to populists due to macroeconomic shocks seems to have intensified. On the one hand, deflation and austerity now play an even more pronounced role than before the Great Recession, especially for left-wing populists. Countries experiencing deeper deflationary episodes after 2008 also help lift the left-wing populists. Similar conclusions are drawn for spending cuts, except for Latin America where austerity makes people turn to right-wing populists instead. On the other hand, natural resource rents do not exert a different impact after the Great Recession. They become even less relevant for populist support in Latin America, indicated by the significant negative estimates on the after-crisis interaction term for the region. We also notice the increased similarity in post-crisis voter reaction to shocks across Europe and Latin America, which implies a certain convergence in political preferences.

There are two surprising sets of post-crisis estimates in Table 1. First, income per capita recessions actually harm populists, and the effect is more significant for Latin America than for Europe. This may be anticipated in some countries long governed by populists, e.g., Venezuela, which may experience populism fatigue. However, this effect is harder to explain in Europe, where left-wing populists lose electoral support as a result of recessions, and Greece is a notable example to the contrary. Second, one would expect higher right-wing popularity in countries receiving more immigrants. The electoral outcomes from the 2016 British referendum, and the 2017 Dutch, French, and German elections indicate that those countries are both receiving a lot of immigrants and increasingly voting for far-right populists. However, contrary to the expectations, the estimates demonstrate that countries receiving more immigrants in Europe do not fall easily for populist agendas—the overall effect is insignificant, and so are the interactions with AC. Only in Latin America countries receiving more migrants are actually less devoted to populists.

Table 2 presents similar estimates of the correlations between macroeconomic and social shocks and populism dynamics. Just like with the estimates produced by the CATs method, the Arellano-Bond (AB) estimates reveal a significant inherent populist cycles in both Europe and Latin America. Still, the populist cycles in Latin America—especially of left-wing populism—are less predictable.

Further, as before, recessions and austerity boost left-wing populism in Europe, unlike the one in Latin America. Income per capita dynamics, inflationary pressures, fiscal cuts, natural resource discoveries, and migration shocks play a very similar role, evident from the post-crisis estimates in both tables.

There are three notable differences between the CATs and the AB estimates. First, deflation plays a statistically significant role in pushing populism forward in the AB estimates. However, the effect is still politically negligible. Second, according to the AB estimates, the post-crisis populism landscape in Europe seems unaffected by macroeconomic shocks, while the CATs estimates demonstrated a significantly different impact of recessions, inflation, austerity, and trade participation. Third, the AB estimates for Latin America also demonstrate a lower impact of income inequality on populism than the CATs estimates. We also note that when country fixed effects are explicitly included in the difference GMM model, STATA fails to report SEs for Latin America because of insufficient observations. Therefore, the AB model run on differenced data is done without the country fixed effects.

Due to significant multicollinearities observed between the explanatory variables, we need to check if the data offer further insight into the political economy of populism when each of the variables in \(X_{it}\) is included separately. Table 3 presents the estimates from the separate estimations. Just as before, the models also include lagged-dependent variables and are estimated in differences. For parsimony, the table reports only the parameter estimates of the variables in \(X_{it}\).

The estimates are not very different from what we observed in the previous two tables. Recessions play a role for spurring populism in Europe only. Countries going through deflationary episodes are more likely to vote for populist. Populist votes in Latin America appear more sensitive to rising unemployment and income inequality, especially after the crisis. The lack of this effect in Europe is perhaps due to the well established and more generous social safety nets there. Just as before, increasing rents play a significant role for propelling populism while immigration does not prompt more populist votes, even in the models estimated separately.

Trade participation is the only factor that comes up significant, while the original estimates did not capture any impact. The effect is particularly notable for Latin America, where countries increasing trade openness turn to populism more often, consistent with the intuition set forth in Rodrik (2017). A number of robustness checks follow (Table 4).

Robustness Checks

A series of robustness checks were performed to ensure the results are not driven by the choice of models, variables or variables definitions. The core messages after those checks remained the same. In some cases, messages came out stronger suggesting the benchmark estimates were rather conservative.

Inequality

The Gini coefficient is only one of the measures that proxy how unequal a given society is. The WIID3.4 also contains information on the income ratio between the first and the fifth quintile, and the first and the tenth decile. I use those ratios as alternatives to the Gini coefficient in the benchmark estimations. The results are roughly the same, with minor qualifications.

Specifically, when the decile income ratio substitutes for Gini, changes in income inequality continue to play a statistically negligible role for boosting populism. Inequality becomes marginally more important for left-wing populism after the crisis, and in the entire sample of countries. At the same time, plugging the decile ratio for Gini changes other estimates. For example, both the rents and austerity come out stronger and more significant than in the benchmark estimates, especially for Latin America. Similar conclusions were drawn when the quintile ratio was used, with somewhat subdued impact of inequality on populism than the decile ratio.

Austerity

In the benchmark models, the G/GDP ratio measures if a certain government has adopted austerity measures. A decline in the ratio is what defines austerity. However, G/GDP may decline because GDP has risen even without an explicit reduction in government expenditures. Then, we possibly need a change in the way we define austerity. If we use a decline in the log-government expenditures in constant dollars instead of the decline in G/GDP, then austerity plays a stronger role for spurring left-wing populism in Europe but the post-crisis estimates become insignificant. This is valid for both Europe and Latin America.

Migration

The benchmark model uses the stock of migration. However, net migration can also guide voters to the political extreme rather than the stock of immigrants. Then, migration stock and its interaction with AC are replaced by the net flows of immigrants. Overall, similarly to the benchmark models, net migration is still uncorrelated with electoral outcomes for populists. Countries seeing less migrants are more prone to populism of both kinds. This time the results are significant also for Latin America. In addition, substituting net migration for the stock of migration renders austerity as a stronger factor driving left-wing populism than in the benchmark model.

Trade Openness Versus Capital Account Openness

Rodrik (2017) argues that not only increased trade participation but also a deeper financial integration makes voters more susceptible to populists. Then, a natural robustness check would be to replace trade openness with capital account openness. One of the more comprehensive sources of data on capital account openness is the Chinn-Ito Index detailed in Chinn and Ito (2006) and especially Chinn and Ito (2008). The index was updated in 2017 and covers the period between 1970 and 2015 for most countries in our sample.

The benchmark estimates suggested that trade openness was not the main driver of demand for populism, and so is capital account liberalization. However, there is a marked difference between the post-crisis reaction of voters to trade and financial openness. Whereas trade openness after the crisis was associated with no significant increase in the populism hype, capital account liberalization has lead to a significant boost in populist appeal on both ends of the political spectrum. The capital account effect is stronger for Europe than for Latin America.

Election Cycle Durations

The differences in the benchmark model were constructed with respect to the previous election year. However, there is another approach to check if populism dynamics has been affected by macro-shocks. Rather than observing elections years only, we could assume constant populism appeal within each electoral cycle until the following elections. Effectively, this means artificially blowing up the number of observations which, at first glance, is hardly a credible strategy. In addition, when those observations are differenced, the model will regress a number of zeros on a shock which may underestimate the true effects of those shocks. However, imputing populist appeal between elections has one advantage: we can check if the lag-length has any effect on the estimates, even though we know those would be biased. Three different lag-lengths have been used: 3, 4, and 5 years, respectively, to accommodate the duration of a typical election cycle.

Varying election cycle durations changes little about the core messages of the paper. Recessions, deflation, and austerity play in the hands of European left-wing populism. In addition, macro-shocks play a more pronounced role in the post-crisis political dynamics. Recessions and deflation boost left-wing populism even further, with the effects becoming significant for Latin American left-wing populism as well. The results are not highly sensitive to the duration of the lag.

Lagged Explanatory Variables

The benchmark \(X_{it}\) excludes lags of the differenced explanatory variables. However, economic shocks may have a longer-term implications than just their contemporaneous effect on populism. Then, we need to take into account those implications by running the benchmark model with lagged explanatory variables as well. To do that, I first determined the optimal number of lags for each of the explanatory variables by a pvar-procedure. Overwhelmingly, the number of optimal lags turned out to be one.

The lack of sufficient observations for Latin America, however, necessitates two changes in the model for the region: Time-fixed effects were removed, and the lags of X-es were not differenced, both to preserve degrees of freedom. As the model for Latin America changed which makes the estimates harder to compare across regions, I prefer to exclude the lagged independent variables from the benchmark model. The rest of the model remained unchanged.

Including lags of the differenced explanatory variables delivered a stronger message than the benchmark model. They preserved the contemporaneous effect of recessions and austerity on left-wing populism in Europe. In addition, a rise in unemployment gave a marginally significant boost to left-wing populism. Increase in migration has also barely contributed to an increase in the overall populism score, unlike in the benchmark estimations.

The lags of recessions, unemployment and fiscal contractions, which were missing from the benchmark model, showed some teeth in boosting populism. So did the lags of post-crisis immigration flows, which confirms the increased role of immigration in shaping the post-crisis voter preferences. Including lags of explanatory variables has also dramatically increased the explanatory power of the models. Indeed, as expected, populism today could be driven by shocks from the not so distant past, as Dalio et al. (2017) have conjectured.

Redefining Populism

All of the estimates so far were produced by using the expanded Heinö (2016) data, which understands the rise of populism as a boost in electoral demand for pre-defined populists, be they incumbent or potential entrants. This means the estimates ignored populism as a rhetorical style of incumbent politicians, as measured in the Rode and Revuelta (2015) data.

In the Rode and Revuelta (2015) data, the dependent variable runs from 0 to 1.9, while in the expanded Heinö (2016) data it ranges (theoretically) from 0 to 100. Then, for the sake of making comparisons easier, I normalize the former so that it varies from 0 to 100. However, the data coverage, the within-country time variation in the populism indices and the conceptual differences in how populism is defined make comparisons problematic. The time variation is particularly hard to work with, as differencing leaves the model with insufficient number of observations. Therefore, we need to resort to running the models in levels, and without lags of dependent and independent variables, which calls for caution when comparing the results with the benchmark estimates.

Still, a few of the core messages were kept intact. Just like in the benchmark estimates, recessions per se did not play a crucial role in strengthening populist rhetoric. However, countries going through deflationary episodes did experience a boost in populism, as before. In addition, countries experiencing higher income inequality are also more prone to populist rhetoric. Finally, the crisis had a statistically insignificant correlation with the rise of populist rhetoric, unlike most of the benchmark estimates.

Despite the existing differences across models, data coverage and definitions of variables, a number of conclusions are in order. Those conclusions shed light on how macro-shocks affect electability of populists.

Conclusion

Populist resurgences can be quantified, and their dynamics can be attributed to the underlying social and economic shocks, as expected in the literature. However, to this date no empirical estimates have been produced to better understand what drives populism across a number of countries over numerous electoral cycles. This paper uses a sample of 49 European and Latin American economies over more than 30 years to address the political economy of populism.

One of the key takeaways is that populist cycles exist in multiple countries over multiple periods. The existence of those cycles means that the single most important predictor of the demise of populism is its own rise to prominence. Voters falling for populists in Europe and Latin America in any current elections are more likely to abstain from the political extremes in the following ones, and vice versa.

Although populism lives through its own cycles, it is not independent from economic shocks. Deflationary episodes which typically coincide with recessions turn voters into the hands of populists, and insufficient social safety nets add to the populist appeal, especially of left-wing populists. A windfall of natural resources also supports populists in both Europe and Latin America.

Demand for populism is also inherently different in Europe and Latin America. Voters in Europe demand more populism during recessions accompanied by austerity, while voters in Latin America are more sensitive to income inequality. At the same time, the Great Recession seems to have triggered a convergence of voter preferences across countries. This is indicated by the significant similarities in how voters in Europe and Latin America respond to macroeconomic shocks after the Great Recession.

Despite the ongoing political preference convergence, time invariant country characteristics are still an important factor behind the rise and fall of populist appeal. This means some countries are more prone to populism than others, which could be related to the differences in what is now commonly described as informal institutions.

This study has also shown that macroeconomic shocks have a way to exert a long-lasting impact on voter preferences for populism. This was indicated by the significance of many of the deeper lags included in the robustness checks. To adequately check how long the memory of voters with respect to populism is, it would be practical to live through another handful of election cycles across countries, and gather more data. Until then, we are bound to keep studying populism in a world of small sample biases. Still, it is a step forward from the case study approach dominating the field so far.

Notes

For a detailed description of data collection methods, see Heinö (2016, pp. 13–15).

Most of the data for Europe and Latin America do not include refugees. Exceptions are: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Hungary in Europe, and Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and Nicaragua in Latin America. In those countries refugee data are included into the migrant stock estimates.

References

Arellano, M., and S. Bond. 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies 58(2): 277–297.

Cahill, B. 2007. Of note: Institutions, populism, and immigration in Europe. SAIS Review 27(1): 79–80.

Cameron, A.C., J.B. Gelbach, and D.L. Miller. 2008. Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. The Review of Economics and Statistics 90(3): 414–427.

Chinn, M.D., and H. Ito. 2006. What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions. Journal of Development Economics 81(1): 163–192.

Chinn, M.D., and H. Ito. 2008. A new measure of financial openness. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 10(3): 309–322.

Dalio, R., S. Kryger, J. Rogers, and G. Davis. 2017. Populism: The phenomenon. Technical Report 3/22/2017, Bridgewater Associates, LP.

Dornbusch, R., and S. Edwards. 1990. Macroeconomic populism. Journal of Development Economics 32(2): 247–277.

Dornbusch, R., and S. Edwards. 1991. Introduction to “The macroeconomics of populism in Latin America”. In The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America, ed. R. Dornbusch, and S. Edwards, 1–4. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dovis, A., M. Golosov, and A. Shourideh. 2016. Political economy of sovereign debt: A theory of cycles of populism and austerity. Working Paper 21948, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Esarey, J., and A. Menger. 2018. Practical and effective approaches to dealing with clustered data. Political Science Research and Methods , 1–19.

Gidron, N., and P.A. Hall. 2017. The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right. The British Journal of Sociology 68: S57–S84.

Greskovits, B. 1993. The use of compensation in economic adjustment programmes. Acta Oeconomica 45(1/2): 43–68.

Hawkins, K.A. 2009. Is Chávez populist? Measuring populist discourse in comparative perspective. Comparative Political Studies 42(8): 1040–1067.

Heinö, A.J. 2016. Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index 2016. Stockholm: Timbro Institute.

Hewison, K. 2005. Neo-liberalism and domestic capital: The political outcomes of the economic crisis in Thailand. The Journal of Development Studies 41(2): 310–330.

Ibragimov, R., and U.K. Müller. 2010. t-statistic based correlation and heterogeneity robust inference. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 28(4): 453–468.

Jagers, J., and S. Walgrave. 2007. Populism as political communication style: An empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. European Journal of Political Research 46(3): 319–345.

Jones, E. 2007. Populism in Europe. SAIS Review 27(1): 37–47.

Kaufman, R .R., and B. Stallings. 1991. The political economy of Latin American populism. In The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America, ed. R. Dornbusch, and S. Edwards, 15–43. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Leon, G. 2014. Strategic redistribution: The political economy of populism in Latin America. European Journal of Political Economy 34: 39–51.

Matsen, E., G.J. Natvik, and R. Torvik. 2016. Petro populism. Journal of Development Economics 118: 1–12.

Mazzuca, S.L. 2013. Lessons from Latin America: The rise of rentier populism. Journal of Democracy 24(2): 108–122.

Milanovic, B.L. 2014. All the Ginis, 1950–2012. Updated in Autumn 2014.

Moffitt, B. 2015. How to perform crisis: A model for understanding the key role of crisis in contemporary populism. Government and Opposition 50(2): 189–217.

Nohlen, D. 2005. Elections in the Americas: A Data Handbook: Volume 2. South America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ocampo, E. 2015. Commodity price booms and populist cycles. An explanation of Argentina’s decline in the 20th century. CEMA Working Papers: Serie Documentos de Trabajo. 562, Universidad del CEMA.

OECD. 2017. International migration database. Retrieved from http://stats.oecd.org.

Roberts, K.M. 2007. Latin America’s populist revival. SAIS Review 27(1): 3–15.

Rode, M., and J. Revuelta. 2015. The wild bunch! An empirical note on populism and economic institutions. Economics of Governance 16(1): 73–96.

Rodrik, D. 2017. Populism and the economics of globalization. Working Paper 23559, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Rohac, D., S. Kumar, and A. Heinö. 2017. The wisdom of demagogues: Institutions, corruption and support for authoritarian populists. Economic Affairs 37(3): 382–396.

Sachs, J.D., and A.M. Warner. 1999. The big push, natural resource booms and growth. Journal of Development Economics 59(1): 43–76.

Tejapira, K. 2002. Post-crisis economic impasse and political recovery in Thailand: The resurgence of economic nationalism. Critical Asian Studies 34(3): 323–356.

United Nations. 2017a. Trends in international migrant stock: The 2017 revision. Downloaded Jan. 20, 2018.

United Nations. 2017b. World population prospects: The 2017 revision. Downloaded Aug. 6, 2017.

UNU-WIDER. 2017. World income inequality database (WIID3.4). Downloaded Sep. 13, 2017.

World Bank. 2017. World Development Indicators, 1960–2016. Downloaded Aug. 6: 2017.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Martin Rode (University of Navarra) for sharing The Wild Bunch! data and to Andreas Heinö (Timbro Institute) for sharing the Timbro Authoritarian Populism data. Two anonymous referees, and the participants at the 12th Young Economists Seminar of the 23rd Dubrovnik Economic Conference offered invaluable advice for further improvements, especially: Oleh Havrylyshyn, Ricardo Lago, Randall K. Filer, Paul De Grauwe, Yuemei Ji, and Vahagn Jerbashian. Luboslav Kostov provided helpful research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stankov, P. The Political Economy of Populism: An Empirical Investigation. Comp Econ Stud 60, 230–253 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-018-0059-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-018-0059-3