A judgement of taste on which charm and emotion have no influence (although they may be bound up with the satisfaction in the beautiful), – which therefore has as its determining ground merely the purposiveness of the form, – is a pure judgement of taste.

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgement (1790), par. 13.

Abstract

This article examines the social construction of indie-folk as a genre, defined not primarily as an aesthetic category but as a tool and resource of social differentiation. Drawing from 48 in-depth interviews with musicians, gatekeepers, and audience members, the discourse of indie-folk is analyzed, focusing on how Dutch community members draw social and symbolic boundaries. Analysis shows that they are “poly-purists,” a type of cultural omnivores who consume a broad variety of musical genres yet by staying within the confines of the indie music stream rather than adopting a politics of ‘anything goes.’ By transposing the aesthetic disposition to the historically lowbrow phenomenon of folk music, community members distinguish ‘authentic’ folk from mainstream pop and dance, lowbrow country, and highbrow jazz and classical music. Simultaneously, they choose within these and other genres those items that match their ‘quality’ taste. Therefore, this study classifies indie-folk as a rising genre and contributes to existing research on cultural hierarchy and diversity, arguing that the emergence and institutionalization of indie-folk is part of the ongoing historical narrative of a Kantian aesthetics emphasizing the disinterested nature of artistic evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the central questions that emerged from scholars’ application of Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital to the study of genre in popular music is whether the binary distinction between “high” art and “popular” culture can be maintained (e.g., Peterson and Kern, 1996; Holt, 1997; Van Venrooij and Schmutz, 2010). Bourdieu (1984) discerned a hierarchy in 1970s French society both in the type of cultural goods consumed and in the modes of cultural consumption. On the one hand, a “legitimate taste” existed, requiring an “aesthetic disposition” or “pure gaze,” which values form over function and “implies a break with the ordinary attitude towards the world” (Bourdieu, 1984, p. 31). In general, people who possess an aesthetic disposition experience art through “aesthetic distancing,” most notably from immediate sensation and easy enjoyment, and by showing economic “disinterestedness.” “Illegitimate taste,” on the contrary, is characterized by a “popular aesthetic” that affirms “the continuity between art and life” and exhibits hostility towards formal experimentation or, vice versa, displays a demand for social engagement, emotion, and audience participation (ibid, pp. 32–34). Both aesthetics, according to Bourdieu (1993a), operate in a dichotomous power structure in which two fields of cultural production are in an antagonistic relationship: on the one hand, a field of “restricted” production in which economic profit-seeking is avoided and status is achieved through the production of “symbolic capital”; on the other hand, a field of “large-scale” production which involves “mass” or “popular” culture and in which profit-seeking dominates (Johnson, 1993, pp. 15–16).

These distinctions, however, are not carved in stone. It has been argued that various popular music genres, most notably blues, rock, bluegrass, and folk, have gained status and artistic legitimacy during the past two decades (Peterson and Simkus, 1992; van Eijck, 2001; Van Venrooij and Schmutz, 2010), as well as that hierarchies between the highbrow and lowbrow also exist within distinct music genres (Hesmondhalgh, 2006; Hibbett, 2005; Strachan, 2007). This article similarly argues that the emergence and institutionalization of indie-folk as an industry-based genre (Lena, 2012) is part of the qualitative shift from snobbism to cultural omnivorousness as a marker of high-status (Peterson and Kern, 1996).

In this article, I specifically argue that the social construction of indie-folk is an example of the so-called “omnivorous paradox” (Johnston and Baumann, 2007, p. 178). This refers to a strategy of the cultural (upper) middle-classes in western societies, comprising openness to popular forms of culture on the one hand, while simultaneously drawing boundaries around highbrow cultural forms, notably those associated with high economic and symbolic capital, on the other. Previous research suggests that such a paradox is emblematic for an omnivorous taste characterized by eclecticism, diversity, and a general trend away from cultural snobbery; the latter a form of exclusion no longer feasible for high-status groups due to various democratic tendencies in western societies, including rising levels of education, class mobility, geographic migration, and counter-institutional currents in the art worlds and cultural industries (Peterson and Kern, 1996; van Eijck, 2001; Lizardo and Skiles, 2012; Goldberg et al. 2016). The emergence of the cultural omnivore (Peterson, 1992) – the highly educated individual consuming a broad variety of cultural genres – is regarded as a reflection of these sociocultural shifts. And indeed, various studies point out that cultural omnivorousness is more likely to occur in relatively egalitarian societies such as the U.S. and the Netherlands (Van Venrooij and Schmutz, 2010), or emerges as a trend in countries transitioning to democracy (Fishman and Lizardo, 2013). However, a recurring argument emerging from research on omnivorousness is that underlying the boundary spanning activities of cultural omnivores is an exclusionary politics of class distinction (Bourdieu, 1984). In their study of gourmet food writing, Johnston and Baumann (2007), for example, argue that “authenticity” (and associated frames such as “simplicity” and “exoticism”) is used as a frame through which high-status groups aim to legitimize and reproduce their taste. They do so by applying an aesthetic disposition to forms of popular culture (e.g., the hamburger), while drawing boundaries around dominant cultures associated with either snobbery (haute cuisine) or commercialism (McDonalds). Authenticity, in this respect, becomes the quintessence of ‘quality’ taste. Lizardo and Skiles (2012) similarly argue that omnivorousness is a variant of the aesthetic disposition described by Bourdieu in a postmodern context. They argue that high-status groups have mastered the skill to appreciate a wide range of cultural goods due to the decline in the power of (singular) cultural objects to signify high-status. As a result, they legitimize and reproduce their taste, not only by consuming broadly, but also by transposing their disposition to cultural objects associated with popular and vernacular culture. Thus, by authenticating popular and vernacular culture through applying the aesthetic disposition, they simultaneously engage in social distinction.

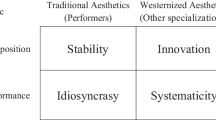

Recent research by Goldberg et al. (2016) points into the same direction. By operationalizing omnivorousness on two different dimensions – (i) variety (operationalized as heterogeneous taste) and (ii) atypicality (operationalized as a preference for transgressing genre codes) – they distinguish between two types of cultural omnivores: first, those who both consume broadly and defy genre codes (so-called “poly-mixers”), and, secondly, those who consume broadly but prefer to stay within the confines of established genre conventions (“poly-purists”). Goldberg et al. then demonstrate how a taste for variety decreases one’s adherence to atypicality. They interpret this process as a performance by “poly-purists” to display that they have – or aspire to – high-status. They do so by consuming a wide range of – preferably mobile – genres, while simultaneously appreciating, within these genres, those objects that are associated with refinement, complexity, and sophistication. Poly-purism thus “constitutes a social display of refined cultural taste” (ibid, p. 230). It most likely reflects the taste of the highly educated cultural omnivore we know from previous research characterized by being “disproportionately attracted to traditionally consecrated forms of culture and the arts” (Lizardo and Skiles, 2012, p. 19; emphasis original). It explains the defensive attitude of poly-purists toward cultural activities that span boundaries excessively; specifically those cultural activities that span boundaries between ‘authentic’ art and ‘commercial’ and/or ‘snobbish’ culture. As Goldberg et al. argue, poly-purists are consumers who are capable of assessing cultural objects through their “categorical purity” (Goldberg et al., 2016, p. 221). This is seen as a strategy of cultural omnivores to make their breadth of consumption socially meaningful, that is, to distinguish themselves from both commercial, snobbish, and populist taste or, more accurately, from those objects within genres with a specific commercial, snobbish, and/or populist orientation.

In this article, I argue that the social construction of indie-folk as a genre reflects a similar strategy. Indie-folk aficionados are expected to be poly-purists who, while being tolerant of eclecticism, provide distinction by using the value of authenticity as the quintessence of legitimate taste – that is, by drawing boundaries around the mainstream (commercial pop and dance), the highbrow (jazz and classical music) and the lowbrow (country and vernacular music).Footnote 1 Following this line of argument, the rest of this article proceeds as follows: first, a brief overview of research on genre will be provided, focusing on how indie-folk, over the past two decades, emerged as an industry-based phenomenon. Subsequently, research on indie music is reviewed, focusing on how indie-folk is part of the emergence of an indie music “stream” (Ennis, 1992; Hesmondhalgh, 1999; Hibbett, 2005; Fonarow, 2006; Petrusisch, 2008). After introducing data and method, the results of this research are presented, focusing on how the Dutch indie-folk audience employs distinction while simultaneously adopting a politics revolving around inclusive folk values of egalitarianism, openness, and diversity (Roy, 2010). In conclusion, I reflect on the implications of this study for analyzing the link between music and social structure, as well as its contribution to existing research on cultural omnivorousness as a marker of class distinction.

Theorizing Genre and the Emergence of Indie-Folk

It has been argued that studying the link between musical structure and social structure is complicated by the emergence of a postmodern condition favoring hybridity over categorization (Hesmondhalgh, 2005; Holt, 2007). Straw (2001) argues that the concept of “music scene” is both “flexible” and “anti-essentializing” and is therefore best capable of expressing the fluid boundaries upon which musical communities and their social identities are established. Hesmondhalgh (2005, p. 29) criticizes this view by emphasizing the importance of knowing how social and symbolic boundaries are drawn, “not simply that they are fuzzier than various writers have assumed” (ibid, p. 34). He argues that “genre” is a better candidate, for it has the ability “to connect up text, audience and producers” (ibid, p. 35) and thus to investigate the discourse in which youth, class, and/or race-based politics are encoded. Moreover, by combining the concept of genre with Stuart Hall’s notion of “articulation,” Hesmondhalgh introduces a set of concepts with which the link between music and social structure can be studied without falling back into deterministic reflection or shaping approaches (characteristic of Birmingham subcultural theory) in which symbolic expressions were believed to either mirror or construct social identities.Footnote 2 Thus, instead of suggesting a purely homologous relationship between music and community, he enables us to consider the multiple articulations – “including ‘homologous’ ones” – of musical communities; or, more passively, that social identities can be multiply determined (ibid, p. 35).Footnote 3

Holt (2007) has introduced a “general framework of genre” which gains further insight into how genres are founded, coded, and commodified. He defines genre as “a type of category that refers to a particular kind of music within a distinctive cultural web of production, circulation and signification” (ibid, p. 2). In terms of how genres are established at the organizational (meso) level, Holt argues that they are most often founded and coded by members of “center collectives” (e.g., active fans, leading journalists, iconic artists) within (trans)local scenes. From there on, genres are “further negotiated” by actors working within the commercial music industry, mass-mediating them to mass audiences (ibid, p. 20). Collectively, they come to agree upon the establishment of a hegemonic term and a set of shared conventions including musical codes, values, and practices. This corresponds with research by Lena (2012, pp. 27–55) who, conducting a survey of primary and secondary texts on the history of sixty market-based American music genres, discovered that a majority of musical forms follow a certain pattern in their development. This pattern is referred to by Lena as the AgSIT-model, emphasizing the embeddedness of genres in Avant-garde movements, which gradually evolve into Scene-based and Industry-based genres. This trajectory is followed by a Traditionalist phase, when the music is no longer seen as the ‘next big thing in popular music’ and is turned into cultural heritage.

The history of indie-folk as a genre followed the same pattern as indicated by Holt and Lena. What started as an avant-garde movement in the early 1990s gradually evolved into scene-based genres coined New Weird America (2003), free-folk (2003), and freak-folk (2004); genres which in turn were morphed into the commercially successful phenomenon of indie-folk around 2005 (see Keenan, 2003; Petrusisch, 2008; Encarnacao, 2013 for historical overviews). The incorporation of new genres into the “folk music stream” (Ennis, 1992) indicates that “culture produces an industry” (Negus, 1998, p. 3), for it points to the institutionalization of new generic rules associated with the genre of folk. However, it also means that “industry produces culture” (ibid, p. 2): with indie-folk becoming an industry-based genre, Dutch musicians started to produce indie-folk for the national market, resulting in the formation of (trans)local scenes and fan-driven entrepreneurial activities (Van Poecke and Michael, 2016). I discuss these new generic rules in the results sections below. First, however, the genre of indie-folk will be situated in the broader field of indie music.

What is Indie? Two Strategies in Preserving Authenticity

The origins of indie music could be roughly traced back to countercultural movements in the international music industry, leading towards the establishment of ‘independent’ record firms and ‘underground’ music scenes in the late 1950s and early 1960s (Hesmondhalgh, 1999; Hibbett, 2005; Fonarow, 2006). Hibbett (2005, pp. 57–58), for example, points to the lo-fi and experimental productions of the Velvet Underground “as an edgier and poorly received alternative to the Beatles,” and therefore defines their music as an early example of rock music that produced a certain kind of aesthetic homologous to the band’s industrial politics. From there on, a historical lineage can be discerned to the counter-institutional politics of the international punk movements in the mid-to-late 1970s, the emergence of ‘college rock’ in the early 1980s, and the advent of ‘alternative rock’ in the late 1980s. However, with grunge music becoming a mainstream phenomenon in the early 1990s due to the commercial success of Seattle bands such as Pearl Jam and Nirvana, the term ‘alternative’ lost its embattled stance. “It is out of this Oedipal tradition,” as Hibbett (2005, p. 58) writes, “and in rebellion against the all-too-efficient metamorphosis of what was ‘alternative’ into something formulaic, that an indie consciousness emerged.”

Hesmondhalgh (1999) similarly observes how ‘indie’ first designated a (rebellious) political attitude, but how it gradually evolved into a particular style or genre. He describes how the term was coined in the mid-1980s by gatekeepers at the British music industry to describe a “more narrow set of sounds and looks” as an alternative to the more eclectic experimental aesthetics covered by the umbrella term ‘post-punk,’ including “‘jangly guitars, an emphasis on clever and/or sensitive lyrics inherited from the singer/songwriter tradition in rock and pop, and minimal focus on rhythm track” (1999, p. 38). Over the last two decades, indie music has turned into a global phenomenon that resembles the emergence of a distinct “music stream” (Ennis, 1992), a concept referring to a set of musical styles that “retains [its] coherence through shared institutions, aesthetics, and audiences” (Lena, 2012, p. 8). As an independent music stream, indie includes multiple hyphenated genres, such as indie-rock, indie-pop, and indie-folk.

Fonarow (2006, p. 26), more specifically, defines “indie” (i) as a “type of musical production” (associated with small labels operating within a distinctive web of ‘independent’ music distribution); (ii) as an “ethos” (rooted in the rebellious narrative of punk culture), and (iii) as a “genre.” At a basic level, she defines the genre of indie as “guitar rock or pop combined with an art-school sensibility” (ibid, p. 40). Indie bands generally consist of a four-piece combo with electric guitar, bass, drums, and vocals. The conventions of indie are structured around a set of key values including simplicity, austerity, technophobia, and nostalgia (ibid, p. 39). Simplicity is at the core of the genre, producing the context in which the rest of the values operate. According to Fonarow, indie is characterized by the idea that music should be stripped bare to its purest form. This produces a set of stylistic conventions in regards to music production, performance, and musicianship, including that (i) songs are short and direct; (ii) song structures are basic and streamlined; (iii) musicians are self-taught instead of being trained in institutional settings; (iv) guitar soloing is reduced to the minimum; (v) looks are modest; and (vi) live performances are perceived as immediate and direct, while recorded music is seen as constructed and removed (ibid, pp. 39–51).

In his socio-linguistic analysis of the indie-rock genre, Hibbett (2005) draws a parallel between indie-rock and high art, arguing that the indie-rock community defines the genre in terms of an avant-garde aesthetic. By defining themselves as agents who possess a knowledge of the field, indie aficionados aim to maintain a hegemonic position within the field of popular music and distinguish themselves from those who ‘lack’ cultural capital. The expression of such a ‘highbrow’ taste has resulted, according to Hibbett, in the creation of a set of stylistic conventions revolving around avant-garde ideals such as innovation, experimentation, authenticity, and obscurity with which indie-rock defines itself as the mirror image of commercial music production and distribution. Echoing Bourdieu’s analysis of the “restricted” field of cultural production (see Introduction), Hibbett (2005, p. 60) argues that “indie enthusiasts [thus] turn to symbolic value, defending what they like as ‘too good’ for radio, too innovative and challenging to interest those blasting down the highway. They become the scholars and conservators of ‘good’ music.”

By conducting a Bourdieusian analysis of the field of indie-rock, Hibbett provides insightful information into how the genre is not only a reflection of the community’s ‘taste,’ but also how it “satisfies among audiences a desire for social differentiation and supplies music providers with a tool for exploiting that desire” (ibid, p. 56). In so doing, he complicates the binary distinction between high art and popular culture by investigating the hierarchies within the field of popular music and by framing rock as a genre of music that over the past two decades has gained in status and artistic legitimacy. Similar to how Bourdieu (1993a) distinguishes between the field of “restricted” and “large-scale” production, Hibbett argues that “indie rock is part of a dichotomous power structure in which two fields operate in a contentious but symbolic relationship” (ibid, p. 57). In the words of the author,

[a]s an elite sect within a larger field, indie rock requires its own codes, i.e. cultural capital, and therefore can be used to generate and sustain myths of social or intellectual superiority. Obscurity becomes a positive feature, while exclusion is embraced as the necessary consequence of the majority’s lack of ‘taste’. Indie rock enthusiasts (those possessing knowledge of indie rock, or ‘insiders’) comprise a social formation similar to the avant-garde of high culture.

Hibbett, more specifically, distinguishes between “two aesthetic movements” that historically have been associated with the genre of indie-rock (ibid, p. 56). The first movement, epitomized by acts such as Smog (Bill Callahan), “Palace” (Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy), and Lou Barlow’s Sebadoh, is rooted in DIY ideology and aims to connote ‘honesty,’ ‘sincerity,’ and ‘integrity’ through the use of lo-fi recording techniques. By emphasizing the direct presence of production, lo-fi ironically aims to connote sincerity by suggesting its absence and “provides a space in which artworks seem to exist outside the conditions of their production, and a bastion from which the cultured few may fend off the multitude” (ibid, p. 62). This first movement, then, is infused with a postmodern sensibility, as expressed by lo-fi acts through the use of self-depreciative humor in the lyrics and artwork to paradoxically expose an interest in economic disinterestedness. Moreover, it uses parody to illustrate the heteronomous nature of its products and thus to obscure the boundary between advertising and art (ibid, p. 63). Adopting an ironic stance in production and performance practices is interpreted by Hibbett as a first – postmodern – strategy in preserving “the myth of authenticity” (ibid, p. 64) in a field in which consumers are increasingly more reflexive about the artificial nature of music production and performance (cf. Fornäs, 1995).

The second movement associated with indie-rock is referred to by Hibbett as ‘post-rock’ and provides a second strategy in preserving “the myth of authenticity.” Epitomized by acts such as Sigur Rós, Mogwai, and Godspeed You! Black Emperor, it is characterized by a “fuller, more richly embodied sound” created through the stylistic conventions of more elaborate instrumentation (including strings, winds, and other classical instruments), ambient sounds and environmental soundscapes, narrative fragmentation, the heavy use of multitrack recording techniques, and theatrical performance practices (ibid, pp. 65–66). Such attention to “how things are represented, not just what is represented,” as Hibbett writes (ibid, p. 67), demands aesthetic distancing from members of the audience, “and distinguishes post-rock from what Bourdieu considers popular art.” Post-rock shares its critique of the corporate end of popular music with the first (lo-fi) movement, exemplified, for instance, in Godspeed’s comparison between the music industry and the war industry on one of their albums. Unlike the first movement, however, post-rock does not take an ironic stance in criticizing the heteronomous nature of popular music production, but instead returns to a more ‘modern’ approach by constructing a symbolic universe in the lyrics and art work that postulates “an alternative system of meaning” (ibid, p. 69). By permeating the lyrics and art work with “a constant element of hope,” or a “deep sense of obligation to go on trying,” post-rock suggests a “renewed seriousness,” as Hibbett argues (ibid, p. 66) – “a restoration of grandeur, beauty, and intensity to what had retreated into a flatter, more self-reflexive form of expression.” The construction of a fictional universe through language and visual representation thus makes post-rock a genre, which aims to go beyond the striving for irony and self-reflexive consciousness characteristic of postmodern lo-fi. As Hibbett concludes (ibid, pp. 68–69),

[p]ost-rock is not postmodern. Rather, it assumes a more traditional role in which art becomes a privatized sphere of reality, seen in opposition to a world debased by common values. Political or apolitical, post-rock artists, like the literary Modernists, endeavor toward alternative systems of meaning, seeking unity through myth and symbol in the face of disrepair. Within these richly symbolic, highly politicized narratives the argument for indie authenticity is preserved.

By defining post-rock as a “privatized sphere” which stands “in opposition to the world” (Hibbett, 2005, pp. 68–69), the distinction between ‘independent’ and ‘mainstream’ is brought back into the picture. However, during the past two decades, various scholars have complicated this binary distinction. Conducting a qualitative case study of the institutional politics of British independent record labels, Hesmondhalgh (1999) found that indie firms display a tendency to distance themselves from the punk ethos upon which they were originally established and instead aimed to build commercial partnerships with major record firms (often framed by the indie community as “selling out”). This is interpreted by Hesmondhalgh as a more fruitful approach in an “era of pragmatic acceptance of collaboration with major capital” than remaining true to obscurity and autonomy; a strategy resulting in marginalization (“burning out”) (ibid, p. 53). Indie record firms building relationships with commercial partners thus forms a “protective layer” between the opposing poles of corporatism and independence. Doing so, they provide indie bands the opportunity to first collaborate with “pseudo-independents” to attract the attention of the fan base and to potentially make the transfer to the pop mainstream without necessarily compromising their indie aesthetics (ibid, pp. 53–55).

A similar argument is put forward by Van Poecke and Michael (2016), who found that Dutch indie-folk musicians partner up with commercial firms operating within the “alternative mainstream,” a platform where bottom-up production and top-down distribution converge. They suggest a link between institutional changes as a consequence of the advent of “participatory culture” (Jenkins, 2006) on the one hand and, on the other, the emergence and institutionalization of (popular) musics, like indie-folk, structured around a set of “participatory aesthetics” (Turino, 2008). The adopting of a participatory framework in performance practice is framed as a strategy of the community to criticize the mechanization, specialization, and homogeneity characterizing mainstream music production. On the other hand, it is seen as a strategy of community members to distinguish themselves from punk ethos, which is framed as the construction of a dogmatic master vocabulary creating a rift between (heteronomous) culture and (autonomous) subculture. Dutch indie-folk aficionados present themselves as “true ironists” (Rorty, 1989) by using participatory aesthetics such as harmonious singing, egalitarian stage set-ups, the downplaying of musical virtuosity and soloing, and the use of metaphor and polysemy in language. They do so to create ‘openness’ and to achieve reflexivity, rather than framing the genre’s aesthetics as a “final vocabulary” (ibid.). These aesthetics reflect the community’s ideology revolving around (folk) values of egalitarianism, sincerity, and communion (Roy, 2010). The distancing from mainstream pop and punk relates to Hesmondhalgh’s work referred to above, namely that indie-folk is a “double articulation” of the (upper) middle-class, first, against the ‘dogmatism’ of former subcultures and, second, against dominant cultures associated with high levels of economic and symbolic capital. The emergence and institutionalization of indie-folk as a genre, in other words, reflects both the generational and class politics of a genre community associated with the cultural (upper) middle-class. I elaborate on this argument in the sections below, after first defining indie-folk as a genre and introducing data and method.

Defining Indie-Folk

Similar to how Hibbett observes a fragmentation of categories within the genre of rock music, Petrusich (2008) perceives that there are marked differences in aesthetics and institutional politics between the various folk genres listed above. Regarding the institutionalization of contemporary folk in the U.S. popular music industry, she writes how in the early 2000s,

“most of the artists and bands (…) were tucked under the umbrella of ‘New Weird America’, which flowed into the slightly more descriptive ‘free-folk’, which became ‘freak-folk’, and subsequently evolved, as more and more diverse artists were swept up in the wave, into the catchall ‘indie-folk’ – even though the differences between psych-infused free-folk like MV & WE and acoustic indie-folk like Iron and Wine seem profound enough to warrant at least two distinct, hyphenated prefixes (ibid, p. 239).

Thus, despite its linear trajectory (see above), the field of independent folk music currently consists of two sub-fields, with the more “restricted” free-folk field on the one hand, and the more commercial (or “large-scale”) indie-folk field, on the other. These sub-fields, as mentioned, have developed their own aesthetics and differ in institutional settings: the former placing premium on ‘music for music’s sake,’ the celebration of autonomy and therefore existing mostly outside of the boundaries of the commercial music industry; the latter placing premium on economic standards, a more conventional understanding of the (pop) album and song structure, and being located at the heart of the international music industry.

Keenan (2003, p. 32), who coined the term “New Weird America,” observed the eclectic and pluralistic tendencies of early free-folk acts such as MV & EE, Six Organs of Admittance, Sunburned Hand of the Man, and Charalambides, by describing their music as drawing on an “intoxicating range of avant-garde sounds, from acoustic roots to drone, ritualistic performance, Krautrock, ecstatic jazz, hillbilly mountain music, psychedelica, archival blues, and folk sides, Country funk and more.” Encarnacao (2013) uses the less normative term “new folk” and defines the music produced and disseminated within the restricted free-folk field as part of the discourse of rock music. He refers to new folk music, associated with acts such as the ones listed by Keenan, but also those of Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, Smog/Bill Callahan, Animal Collective, Joanna Newsom, Devendra Banhart, and CocoRosie, as music that aims “to denote acoustic tendencies and the use of traditional, pre-Tin Pan Alley song forms and techniques in rock practice” (ibid, p. 8).Footnote 4 More specifically, he sees new folk as part of the discourse of punk music, as many of the associated acts are (or have been) connected with independent ways of producing and distributing music. Moreover, they combine punk aesthetics, such as lo-fi production and recording techniques, free improvisation, using expanded or very minimal track structures and putting self-imposed limitations on singing and playing, with folk aesthetics, including the preferred use of acoustic instruments such as the guitar, the banjo, and the mandolin, multiplicity of voices, and harmonious singing (ibid, pp. 8–9); therewith reinforcing romantic tropes of domesticity, community, amateurism, and spontaneity (ibid, p. 240). In Goldberg’s terms (2016), they are producers of contemporary folk music who score high on “atypicality,” as they span boundaries between ‘traditional’ folk and various other established genres, including classical music and hip-hop. Thematically, the music of new folk acts revolves around lyrics telling anthropomorphic stories about nature, the pre-industrial, and animal life, as well as about the innocence of childhood or being transgender; although some of the new folk acts, such as Charalambides, and Animal Collective, rarely advance a narrative, or use narrative fragmentation as a stylistic feature (ibid, p. 236). Thus, when applying Hibbett’s theoretical framework described above, it could be argued that acts (previously) categorized under the umbrellas of ‘free-folk,’ ‘New Weird America,’ and ‘freak-folk’ use a combination between a postmodern (lo-fi) and modern (post-rock) approach in preserving the “myth of authenticity.” While using postmodern recording techniques to create a sound that is both bedroom and backwoodsy, they return to a more modern approach in their poetry, performances, and art work – which evoke a romantic mythos that is antagonistic to a mainstream society perceived as corrupt, commodified, and infused with postmodern irony and cynicism (Keenan, 2003; Vermeulen and Van den Akker, 2010).

Music produced within the more commercial indie-folk field, on the other hand, should be seen as part of the discourse of pop music. Although indie-folk acts such as Bon Iver, The Lumineers, Fleet Foxes, and Mumford and Sons make use of the same folk aesthetics as their experimental counterparts (most notably acoustic guitars and harmonious singing), their recordings are more hi-fi produced, albums and songs are more structured, and voices are less limited or even upfront. Thematically, indie-folk is less politically charged and more concerned with autobiographic storytelling revolving around the expression of either melancholia (Bon Iver) or happiness (Edward Sharpe) – that is, a more ‘expressivist’ poetry emphasizing sensitivity, subjectivity, and inwardness (see Van Rooden, 2015).

Methodology

This article is part of a larger research project investigating the production, reception, and aesthetics of independent folk music in the Netherlands for which gatekeepers, musicians, and audience members were interviewed.Footnote 5 In total, 48 semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted in the period between March 2013 and March 2015, lasting between 50 min and two hours and 20 min. Two interviews were double interviews, which eventually resulted in a sample consisting of 50 interviewees in the age bracket 20–57, most of whom are living in larger urban areas in the Netherlands (notably concentrating in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht, and Groningen) and have similar high educational backgrounds in the humanities, arts, social sciences, and natural sciences (see Online Appendix 1).Footnote 6

Thirty-one of the interviewees were male; 9 were female. Although the genre of indie-folk defines itself as egalitarian and inclusive rather than hierarchical (Van Poecke and Michael, 2016), the sample of respondents is consistent with former research indicating that folk music is generally white and male-dominated (Badisco, 2009), as well as that (folk) music revivals are “middle class phenomena which play an important role in the formulation and maintenance of a class-based identity of subgroups of individuals disaffected with aspects of contemporary life” (Livingston, 1999, p. 66). Because of strong similarities in social and educational backgrounds, and because most respondents belong to the same age group (the clear majority of them is in their twenties and thirties), it could be argued that they are part of an “interpretive community” (Holstein and Gubrium, 2000) belonging to the cultural (upper) middle-class in Dutch society (De Graaf and Steijn, 1997).Footnote 7

Interviews were chosen, first, because ‘taste’ is defined as a cultural practice (something one ‘does’ rather than something one ‘has’) and, second, because analyzing “omnivorousness in action” (Lizardo and Skiles, 2012) requires focusing on the modes of cultural consumption rather than on finding patterns between cultural consumption and social class. All of the interviews with musicians and audience members were conducted face-to-face in a domestic setting, with the exception of two interviews using Skype. The interviews with gatekeepers were conducted face-to-face in an institutional setting, except for one interview using Skype, and one interview using e-mail. Names of the interviewees have been changed to protect their privacy. Most of the interviewees, however, clearly stated that were not in favor of using pseudonyms.

The interviews were conducted following the epistemological guidelines of “active interviewing” (Holstein and Gubrium, 1997). This refers to a type of interviewing acting as an “interpretive practice,” meaning that the interview setting is seen as “part of a broader image of reality as an ongoing, interpretive accomplishment” (ibid, p. 113). The interviews were structured around the following five topics: (i) musical taste formation; (ii) definitions of indie-folk; (iii) affinity with indie-folk; (iv) use of indie-folk in everyday life; and (v) broader cultural and political preferences. The interviews with musicians were complemented by questions based on the topics of (i) career path and (ii) use and understanding of indie-folk aesthetics. Interviews with gatekeepers, lastly, were particularly focused on questions on the historical formation of their firms as well as on evaluation methods and the marketing of indie-folk acts included in their rosters, programs, and/or other marketing outlets.

The interviews were transcribed ad verbatim and coded using Atlas.ti, enabling me to search for patterns. Analysis focused on the questions associated with interview topic 2, including questions on how respondents attributed stylistic criteria to indie-folk music, what acts should be in, and excluded from the genre, and personal (dis)preferences in regards to musicians and bands both within and outside of indie-folk. The interview excerpts associated with interview topic 2 were coded inductively (‘in vivo’), resulting in a list of codes emphasizing the discursive strategies of Dutch indie-folk practitioners. These discursive strategies were visually presented using the Atlas.ti network function (see Online Appendix 2). Because the interviews with gatekeepers were not primarily focused on questions about genre classification, analysis focused on the interviews with musicians and audience members. Excerpts taken from these interviews, however, were complemented with fragments from interviews with gatekeepers, as they play a key role in establishing links between production and consumption practices. The results are presented below, which are structured in three parts, focusing (i) on how the authenticity–commercialism dichotomy crosscuts the genre of indie-folk, parceling it into two separate domains involving indie-folk as ‘high’ art and ‘popular’ culture; (ii) on how a taste for indie-folk reflects a taste for ‘quality’ culture; and (iii) on how symbolic boundaries are drawn around a snobbish and populist aesthetic.

Analysis of Judgment: Indie-Folk as a Tool and Resource of Social Differentiation

Aestheticizing the commonplace: indie-folk as high art and popular culture

If indie is defined as music that is stripped bare to its purist form, then indie-folk could be seen as an even more radical version of indie music. Both audience members and musicians generally define the genre as “real” and “authentic,” and support this classification with terms such as “unpolished,” “without glamor,” and “no nonsense” – or, more actively, as “simple,” “primordial,” “ordinary,” “from life itself,” “more pure,” “emotional,” and “honest” (see Figures 1 and 2 in Online Appendix 2). More concretely, the valorization of authenticity is connected to “real instruments,” most notably the acoustic guitar, the violin, the tambourine, and the banjo; to looks that are “casual,” “just neat,” or “everyday,” and to musicians who act “sincere.” The realistic and serious stance with which indie-folk is produced and consumed is reflected, furthermore, in the preference for “little drums,” “constancy of rhythms,” and meandering guitar techniques such as guitar “strumming” and guitar “picking,” reflecting, as one respondent explained (Tonnie, 40, male, Middelburg, professional musician), the routinized and repetitive practices of everyday life itself. On a narrative level, it is reflected in the representation of everyday themes in the lyrics, including themes about discordant and emotionally laden events in life.

Focusing more closely on how musicians define indie-folk (and thus on the production-side of the genre), it is particularly worth noting that they define their lyrics as a form of poetry. Indeed, indie-folk lyrics could be best defined as either lyrical or “narrative poems,” the latter type referring to a form of poetry in which the narrator tells a story either from a first or third person perspective and with sentences typically phrased in the past tense (Jahn, 2005). Stories about communion (e.g., family, friends, love relationships); discordance (e.g., relationships breaking up; sickness, death); the otherworldly (e.g., the sublime forces of nature, dreams, the sub-consciousness), and history (e.g., traditions, customs, religion) are key representations. Here, we also witness the ‘historicism’ underlying contemporary indie-folk. As some of the musicians explain, folk music is evaluated in terms of how it is grounded in tradition and ancient history, so that it contains “infinite depth” rather than being a commodity:

For example, a record like Wolfgang Amadeus by Phoenix [2009 album by French indie-pop act, NvP], I think is really amazing. (…) It is a record you can play endlessly, it’s not just candy. But the real link for me is, if I listen to a Stanley Brothers’ song, or Bob Dylan, that it has infinite depth, because it, eh, it is truly sustainable. I just said, Phoenix, it’s not candy, but eh, folk music, it sometimes exists for more than 1000 years. A church hymn, for example, I think it’s amazing when someone can convincingly sing this today, and touch people. Such a song has infinite depth.Footnote 8

(Kim, male, Utrecht, professional musician).

However, alongside the functional aspects of lyrics, what matters most is the way in which stories are told. Musicians describe their lyrics as “intelligent” and “not stupid,” and explain how songs should be “cryptic,” “a bit vague,” or infused with “poetical abstraction,” rather than conveying their meaning “in an obvious way,” as Djurre and Otto explain:

D: What I think is a nice one is “The Unknown Character” [one of his songs, NvP]. I was with someone in a relationship, who was handing me in a way I could not really deal with, and then I say: ‘You gave me a bouquet of question marks. Told me to keep them in a vase, make sure you water them enough.’ And then I had this image of a question mark in a vase, with the dot below water. And then they all pretty much hang out. (…) But you can also say: ‘Don’t keep me waiting, I miss you’. But I don’t think that is beautiful, it does not appeal to me. (…) I always try to create a certain level of poetical abstraction in what I sing and not just like: ‘I’m in pain’.

(Djurre, male, 36, Amsterdam, professional musician)

O: I see myself both as a folksinger and a singer-songwriter. So I am not entirely a folksinger, otherwise I would only use the codes of folk music. (…) But I’m not entirely a singer-songwriter either, because I refuse to write… like Joni Mitchell, for instance. Then people look at it, as if they are watching a soap series. Like: ‘O, look at me, what happens to me!’ (…) But a really good singer-songwriter, what I think is really interesting, who also has this folk feeling, when they evoke the folk feeling, then the song is also about you. Then you listen to it, and you see it, and then it is like looking in a mirror. (…) Some singer-songwriters, when they sing about being ditched by a girl, then I think: ‘O, how sad for them’. While, when I listen to Leonard Cohen, then I always think he is singing about me: ‘O, how sad for me!’

(Otto, male, 36, Amsterdam, professional musician)

In the first excerpt, Djurre explains how he aims to convey the meaning of his song metaphorically, that is, by encoding the message in such a way that it contains aesthetic value. In the second excerpt, Otto distinguishes the folksinger (Leonard Cohen) from the singer-songwriter (Joni Mitchell). Whereas he sees the folksinger, like himself, as a singer-songwriter by occupation, he at the same time distinguishes between folk and singer-songwriter as two distinct genres. The difference between the two genres is perceived in the way in which stories are told: whereas the singer-songwriter tells the story from a personal perspective (as if it were a soap series), the folksinger allows his personal message to be more universal – that is, more detached from direct sensation.

Focusing on the consumption of indie-folk shows how the genre is consumed not only by showing economic disinterestedness but also through “aesthetic distancing” (Bourdieu, 1984). Indie-folk is generally experienced by audience members by creating a setting in which they are “closed off from the world,” meaning that they prefer to listen to “laidback” indie-folk by breaking with the routinized structure of their daily lives. This is most notably achieved through “active listening,” so that respondents – like reading a book, or drinking a glass of wine – can be “carried away” or slide into a “dream daze.” This is contrasted with other, more up-tempo genres such as rock, electronic dance, and commercial indie-folk in the style of Mumford and Sons, which are generally more listened to while conducting everyday routines (Van Poecke, forthcoming). This is also confirmed by some of the gatekeepers, who classify the indie-folk audience as experiencing music in a contemplative state of mind:

Yeah, one time, someone wrote in a newspaper headline: ‘A contemplative festival’. So these are particularly people who also go to litera… well, book readings. Eh… a peaceful audience, so at our festival you won’t be seeing any stage dives, you know, that kind of stuff. It could be, of course, because I think we have an audience that can handle that kind of music pretty well, but it also needs to be a kind of synching feeling, and I notice that when I program a band that plays extremely loud that… I personally think that is really cool, but… it doesn’t really go berserk. Thus, acts that require a contemplative state of mind, it just works better.

(Michel, 43, male, Den Haag, festival director)

Thus, while the ‘common,’ the ‘common man,’ and the ‘commonplace’ are key representations in lyrics, performances, and art work, the way in which indie-folk is consumed is by creating a setting that “implies a break with the ordinary attitude towards the world” (Bourdieu, 1984, p. 31). This corresponds with research arguing that cultural omnivores are consumers capable of appreciating music aesthetically, that is, by assessing music by means of the aesthetic disposition so that form is valued in separation from function (Johnston and Baumann, 2007; Lizardo and Skiles, 2012; Goldberg et al., 2016). As this study indicates, members of the Dutch indie-folk community are part of the cultural (upper) middle-class (see Methodology section), a fraction in society that achieves distinction by actively criticizing highly commercialized and mass-produced music, while transposing the aesthetic disposition to the consumption of ‘lowbrow’ folk (Roy, 2010). The ability to assess folk music through applying the aesthetic disposition is particularly appropriated by members of the second sub-group: the somewhat older respondents endowed with “objectified” and “institutionalized” markers of cultural capital, including (high levels of) education and familiarity with a wide range of more experimental and obscure indie(-folk) acts (cf. Lizardo and Skiles, 2012, p. 18). The construction of indie-folk as a genre that is counterhegemonic to the mainstream reflects the antagonistic relationship between ‘authentic’ folk and ‘commercial’ pop (Ennis, 1992). However, this study indicates that the authentic–commercial dichotomy also crosscuts the genre of indie-folk itself, parceling it into two separate fields – avant-garde oriented indie-folk and indie-folk with a commercial orientation – each having its own actors, institutional politics, and conventions.

Members of the Dutch indie-folk field (musicians, gatekeepers, and audience members) generally share a taste for a broad variety of cultural disciplines and musical genres. They are avid readers, foodies, and (art house) film enthusiasts, and almost without exception claim not to watch television, aside from documentaries and TV series – that is, the more narrative and ‘quality’ art forms (cf. Johnston and Baumann, 2009 on ‘foodie’ culture and Lavie and Dhoest, 2015 on ‘quality’ television) (see Figure 3 in Online Appendix 2). Interestingly, similar distinctions are made within these disciplines between more ‘authentic’ styles (such as “art house movies,” “literature written in a journalistic manner,” and “sustainable food with quality”) and genres that are considered too commercial and/or snobbish (such as “very simple commercial movies,” “reality TV,” and food that is “too green” or “green in a very idealistic manner”). Zooming in on their musical preferences, they share a broad taste for genres ranging from folk to rock, jazz, hip-hop, bluegrass, Americana, world music, funk, rockabilly, electronic music, and classical music. Within the community, however, a clear distinction can be made between a sub-group favoring the more commercial approach of indie-folk acts such as Mumford and Sons (and associated indie-pop acts such as Coldplay), and a sub-group preferring the more avant-garde indie-folk in the style of MV & EE, Six Organs of Admittance, CocoRosie, and Animal Collective.

The difference between the two groups is that members of the first sub-group, of which the majority are adolescents and early adults, have a taste for indie bands, such as Coldplay and Muse, which have managed to make a crossover to the mainstream. Members of the second group, on the contrary, are somewhat older (most of them are in their thirties and early forties) and have a taste for indie-folk acts at the avant-garde end of the genre. Members of the first sub-group, however, remarkably define indie-folk in the style of Mumford and Sons as a more authentic version of indie-pop. They prefer this type of indie because of the use of acoustic instead of electric instruments, because looks are more modest, and because the lyrics and artwork emphasize “community” and “coziness.” Yet most importantly, because indie-folk acts such as Mumford and Sons and The Lumineers stay within a certain “format,” mostly by building up songs towards reaching a climax, as Julie explains:

(J): This is something I have with other bands as well, but also a little bit when it concerns The Lumineers. It is just relaxing and it is really about the music. Yeah, it brings a sort of coziness, a certain atmosphere. I think this is also very true when it concerns Mumford and Sons. That it reaches a sort of climax.

(N): What do you mean with a ‘climax’?

(J): Well, for example… The song “The Cave” by Mumford and Sons, I think this song is amazing. With the stamping, then it is almost impossible for me to remain seated, and then at a certain moment the song goes faster, and then it is increasingly louder… I am not familiar with those terms, but with these guitars, and then at a certain moment, you see everyone in front of you… dancing and stamping.

(Julie, female, 25, Oostvoorne, sales person)

While respondents of the first sub-group are mostly unfamiliar with indie-folk acts operating at the avant-garde end of the indie-folk genre, respondents of the second sub-group actively criticize the more commercial indie-folk spearheaded by Mumford and Sons, who are remarkably often labeled as “Coldplay with a banjo,” as Bas illustrates:

Mumford and Sons, I really hate it. I think it’s just a pose, there is nothing unique about it. I think it is Coldplay with a banjo. Really disgusting. The mimicry, it is not particularly warm, it is not focused on performing a real song, it is only aimed at scoring.

(Bas, 48, male, Amsterdam, booker/agent/festival organizer)

The framing of Mumford and Sons in such a way shows how members of the second group regard indie-folk with an overt commercial orientation – and mainstream popular music in general – as being too “scripted,” “commodified,” and “structured.” Instead, they prefer music – indie-folk included – which is “unconventional,” “experimental,” “dynamic,” a “little squeaky,” or, as Robert explains, which is more “layered” and has more “depth”:

I have to say that I don’t like Mumford and Sons. They are framed as a folk band, I also think so, but their music, it doesn’t appeal to me. (…) In general, I miss some depth in popular music. The layers I was referring to… I am not really surprised by it. I don’t… Sometimes, I analyze the lyrics, then I discover: ‘Wow, this seems really simple, but it is really deep, this is a really great metaphor!’. But this, I think, is completely missing from popular music.

(Robert, 23, male, Utrecht, University College student)

Musicians and audience members within the second (avant-garde) group commonly define indie-folk as “artistic guitar pop” and strongly associate the genre both with lo-fi and post-rock music in the style of Sebadoh and Godspeed You! Black Emperor (cf. Hibbett, 2005), with electronic dance music in the style of acts such as Caribou and The Knife, and with neo-classical music in the style of Nils Frahm and Ólafur Arnalds. In the distinction, in short, between the two groups within the genre of indie-folk – associated, respectively, with the sub-fields of “large-scale” and “restricted” production – we witness the distinction between a popular aesthetic valuing function over form, and a high art aesthetic characterized by a preference for formal experimentation. Similar to the general image of indie as the mirror image of commercial pop and synthetic dance and techno (Fonarow, 2006), members of both subgroups, however, define indie-folk as the antidote of “mainstream pop” and “electronic dance.” The former category (mainstream pop, linked to acts such as Justin Bieber and Snoop Dogg) is defined in bourgeois terms (“commodity,” “money,” “hype,” “fast food”) and is regarded as “very artificial” and “glamorous.” It is associated with “the average pop listener” as well as with acts such as Lady Gaga that cultivate the artist’s identity through the extensive use of personae. The latter category (electronic dance and techno music) is defined as “synthetic” and “glittery,” indeed because the approach with which music is produced and performed is regarded as “purposefully instrumental,” meaning that it is meant to “effectively” create “euphoric trance” for the “big masses.” Indie-folk, which is regarded as more “pure” and “authentic,” being the antidote. The fact that both subgroups define their version of indie-folk as more authentic in comparison to the mainstream emphasizes the graded nature of authenticity as a method of evaluation, as it is used by two different – and to a certain extent oppositional – groups within the field of indie-folk for the same reason, that is, to distinguish from acts that are considered to be exemplar of mainstream popular music production.

Indie-Folk as a Marker of ‘Quality’ Taste

A recurring theme in the discourse of musicians and audience members belonging to the second sub-group referred to above is the relationship between experimental indie-folk and what respondents themselves refer to as “postmodernism.” Analysis indicates that respondents associate “postmodernism” with concepts such as “deconstruction,” “contingency,” and “relativism,” as well as with taking a reflexive stance to nostalgia. Folk music should be contemporary in the sense that it is eclectic, that both acoustic and electronic instruments are allowed, and that it is characterized by the use of new techniques and sound effects such as “noise,” “distortion,” and “fragmentation.” These are seen as innovations to the genre existing next to more traditional stylistic conventions such as “polymorphous singing,” “little drums,” and “guitar strumming.” The preference for innovation and experimentation explains the negative valuing of taking a restorative approach to nostalgia. It is argued that contemporary folk should not restore the past, but should upgrade the past to the present:

In music I think it is cool to not work from a specific idiom, I don’t think that is really interesting. I also don’t think it is interesting when, for example, a bluegrass band plays bluegrass music from the 1920s. They exist, well fine, but I don’t think it’s interesting. It becomes a sort of attraction. But when you do something new with it, electronic beats for instance, then something starts to happen. (…) What I think is interesting is that it plays with certain expectations. So that you hear a banjo playing, but you start thinking: ‘Is this folk?’. It’s not really folk, it’s not really classical music either, but what is it? What is happening here?

(Djurre, male, 36, Amsterdam, professional musician)

Here, we see how Djurre frames the copying of the past in traditionalist folk and bluegrass music as an “attraction,” while taking a reflexive stance is seen as experimental, innovative, and challenging. Authenticity is thus achieved, according to Djurre, by negotiating between adhering to a folk idiom on the one hand and by renewing the idiom on the other (cf. Peterson, 2005). Musicians particularly encourage the incorporation of stylistic conventions associated with neo-classical music and electronic music into the genre, particularly to create a more “ambient” sound. Thus, while strongly criticizing electronic music “for the big masses,” the incorporation of electronic influences into the folk idiom is encouraged. This corresponds with aforementioned research by Fonarow (2006, pp. 57–62), who found that indie enthusiasts assess music in terms of quality rather than in terms of genre or style. As musicians and audience members explain, indie-folk is music that is “primordial” or created with a “fundamental attitude.” Both songs and performances, moreover, should be “sincere,” meaning that they should “match with the one who performs.” It is believed by Dutch indie-folk practitioners that such a primordial way of creating music is not exclusive to indie-folk but can be achieved in almost any genre. It leads to the construction of oppositional pairs such as The Knife vs. Armin van Buuren, Kanye West vs. Snoop Dogg, “accessible jazz” (e.g., Michael Kiwanuka) vs. “jazz without lyrics” (as a reference to strictly instrumental jazz), and more traditional classical music vs. experimental classical music in the style of Bill Ryder-Jones and Nils Frahm:

For example, there is Bill Ryder-Jones, the guitarist of the Coral, and he, he left the band, but he made an album by himself. It is classical music, but always with arrangements of his own. Yet sometimes it is a classical piece for piano and strings, but then a song transforms into a screaming guitar solo. And that is something I really like, that those kind of things are mixed. But I also listen to the more experimental end of classical music, the more minimalistic spectrum of the genre, and then I end up with someone like Nils Frahm.

(Robert, 23, male, Utrecht, University College student)

A similar discourse is produced by gatekeepers, who generally claim to use quality, rather than style or genre, as a method of evaluation, as explained by Bas:

I don’t think we have a genuine style. I think that, at the best, we have quality as style. Quality. I am now working on organizing a new festival (…). It is oriented at venues of 400 people max, three days, and it is about what we refer to as ‘intrusive quality’, which also is the sub-title of the festival. Thus, quality you cannot escape from, which for some people is too confronting. But on the other hand is pure, authentic, urgent. I think that is the binding element, and not necessarily… yeah, I mean, in terms of style, acts like Lonnie Holley [American folk artist, NvP] are far away from Damien Jurado [American indie-rock artist, NvP], or Adrian Crowley [Irish indie-folk artist, NvP], or Sleep Party People [Danish post-rock/dream pop/ambient act, NvP]. These are all bands we include in the line-up, but there is a certain uniqueness, which we think is very interesting. (…) We are not focused on: ‘We are still looking for a rock band or a…’ It is just to, yeah, sell it, because people need particular frameworks, to evaluate, or, how do you say, to guide them. In this respect, you need to work with them, because people need frameworks.

(Bas, 48, male, Amsterdam, booker/agent/festival organizer)

Here, we see how genre is used both as a tool to organize and classify music and as a marketing tool. Underlying Bas’s classification practice, however, is a process of social distinction. In the construction of “intrusive quality” as a method of evaluation, we see how he erects symbolic fences between himself and those who ‘lack’ quality, that is, those who are not capable of evaluating multiple styles and genres of (popular) music through their “categorical purity” (Goldberg et al., 2016, p. 221). This corresponds with the aforementioned claim by Goldberg et al. (2016), who argue that poly-purists consume heterogeneously, yet by cherry picking those cultural objects within genres that are considered refined, sophisticated, more complex, or prestigious. I therefore emphasize that the ideology of ‘quality,’ and associated frames such as authenticity, urgency, and purity, are socially constructed phenomena. By this I mean that even the most experimental and eclectic music is capable of connoting purity and authenticity. More accurately, that the distinction between ‘authentic’ and ‘commercial’ music is made based on how the former is less formulaic than the latter. This complicates the distinction made by Goldberg et al. between “poly-mixers” and “poly-purists.” While it is undoubtedly true that Dutch indie-folk aficionados are mixers by showing a strong preference for eclecticism, innovation, and formal experimentation, they are first and foremost purists – or even snobs – in the sense of appreciating the more ‘authentic’ – that is, innovative – acts within genres, while disqualifying music that is produced, disseminated, and consumed within the (alternative) mainstream, which is regarded as commercial and overly structured. Simultaneously, they dissociate from a taste that is homogeneous or “mono-purist,” expressed by how they actively distinguish themselves from traditionalist bluegrass practitioners. Music is considered to be ‘authentic,’ then, when it transgresses conventions by being eclectic, and thus by spanning boundaries. Spanning boundaries, however, by mixing techniques, sounds, and styles associated with various genres at the experimental end of the indie stream (rock, punk, post-rock, hip-hop, electronic music, experimental classical music, etc.) rather than adopting a politics of ‘anything goes,’ for example, by mixing indie-folk with commercial pop or traditional classical music. This indicates that poly-purism reflects not merely a broad taste for consecrated forms of culture, but also a more experimental taste for the more ‘authentic’ objects within established categories. The distinction between poly-mixers and poly-purists, in fact, seems to be somewhat obsolete in the context of a musical landscape that is parceled into numerous (sub-)categories and in which innovation is achieved through eclecticism and nostalgia (cf. Reynolds, 2011). This forces high-status consumers to consume broadly, yet by singling out those objects within genres that match their ‘quality’ taste. This is measured in terms of how music is more “pure” or “authentic” – or how it deviates from the standardized mainstream, as well as from music which is associated with snobbism and traditionalism.

Turning Need into a Virtue: Distancing from Snobbism and Traditionalism

Zooming in on the politics of boundary drawing, analysis shows that, next to drawing boundaries around mainstream pop and electronic dance and techno music, both musicians and audience members erect symbolic fences between ‘authentic’ indie-folk (and associated indie genres) on the one hand, and genres that are either associated with traditionalism or populism, like country and Schlager, and snobbism or aestheticism, such as experimental jazz, funk, metal, and classical music. While indie-folk is appreciated because it connotes authenticity and simplicity, traditionalist genres are criticized for being “too simplistic.” Snobbish genres, on the other hand, are criticized for emphasizing technical skill and a purely ceremonial nature of music performance, while indie-folk, at the same time, is defined by community members based on how it incorporates techniques, such as distortion and improvisation, historically associated with the musical avant-garde (cf. Hibbett, 2005). The drawing of symbolic boundaries suggests the antagonistic relationship between indie-folk practitioners and musical communities that either prefer to consume more ‘lowbrow’ or ‘highbrow’ forms of music.

Next to the genres of mainstream pop and electronic dance and techno music, metal and hard rock are commonly criticized because they are associated with “false” emotions, most notably aggression, in comparison to more ‘authentic’ emotions such as cheerfulness, melancholia, and depression. Moreover, metal and hard rock music is criticized, because these genres are associated with a very “ceremonial” and “technical” style of performing through extensive guitar soloing and drumming. More lowbrow forms of music, most notably country, Schlager and vernacular music, are defined as “carnavalesque,” whereas high art-infused genres such as jazz and classical music, are framed as “rational” or as “elitist stuff.” Thus, while country music is considered to be “too simplistic,” both jazz and classical music, as Ronald explains, are defined as “too technical”:

Yeah, MV & EE [American free-folk ensemble, NvP]. That kind of music for me is very interesting, because it connects to… both the way I would like to experience music and the way I play music myself. (…) You know, you can listen to classical music, and then it really is about the repetition of certain patterns, and subtlety as well, that things are repeated. But on the other side of the spectrum it is improvised music, eh… yeah, which maybe is more lively and it is about interaction between musicians. For me, that is interesting to do, and I find it really interesting to look at it when I go to concerts. With Matt Valentine and those types of musicians, I think it’s really interesting what happens there, because things happen that are unexpected. And you notice that they [the musicians, NvP] also don’t know. It’s not about technical perfection.

(Ronald, male, 41, De Bilt, visual artist and lecturer)

Here, we see how improvisation is encouraged by Ronald, however only when it serves the goal of celebrating music collectively. This is contrasted with a style of improvisation more common in jazz, which is initiated ‘for the sake of musicians.’ Indie-folk, in other words, operates in a flirtatious relationship both with lowbrow forms of music, like country, which recall the ideology of folk as “music of the people,” and with genres, such as jazz and classical music, which require a preference for innovation, formalism, and experimentation (cf. Peterson and Simkus, 1992). It too, however, maintains a defensive relationship with both genres: with country because it is considered to be “too simplistic,” and with forms of jazz and classical music because they are framed as “too experimental,” “too technical,” or “overly composed” (emphasis added). The way indie-folk operates in a double bind with both the lowbrow and highbrow is reflected in the way respondents define country as a “guilty pleasure,” while experimental jazz is seen as unknown territory yet a field to be conquered:

(M): Real diehard country music, as in Willie Nelson, I think that is really annoying and also a bit simplistic. I don’t like to be associated with that, I guess. (…) Now folk music, of course, is typically American as well, but somehow I feel that there is less to it and that… No, I absolutely don’t like it and that is why, when some music leans towards country, then I immediately… I can appreciate it, secretly, but then it becomes a sort of guilty pleasure, because I actually don’t allow myself to like country, even if I secretly like it.

(Matthijs, male, 26, Rotterdam, Ph. D. student)

(E): For example, music like jazz… It can go in every direction, the way I see it. If you use a compass, it can go 360 degrees and every song can be really unpredictable. And folk music, on the contrary… it can be unpredictable as well, but it is not as predictable as pop and not that structured. But it creates a lot of opportunities for me. (…) The jazz genre is something I want to be more familiar with, and eh… immerse myself in it, a little bit. It’s a little project.

(Esther, female, 29, Groningen, front office employee)

From the part of musicians, the double bind relationship with genres that require considerable cultural capital (in the form of knowledge and musical skill) is reflected in the way they, on the one hand, frame indie-folk as music that is “intellectual,” “artistic,” and “contemplated.” On the other hand, it resonates in the way they negatively define their preference for participatory aesthetics, such as the downplaying of musical virtuosity, limited guitar soloing, and playing improvised music collectively – that is, by criticizing a very individualistic, “macho,” “technical,” and/or “ceremonial” style of performing which is more common in genres such as jazz and classical music. Yet, it also echoes in the way musicians define their strategy of producing participatory music as a means to compensate some of their “limitations” as a musician, as Mink and Tessa, respectively, explain:

(M): I can’t really stand it when, I always refer to it as a kind of macho type of music, and I always think about it in this way when it concerns jazz, or funk, or that kind of stuff. I can appreciate music when it has these influences, but if it is only like ‘hear me going!’ – it’s of course a bit biased – but then I’m like: ‘Try to create something nice together’ instead of ‘Yeah, this really grooves!’. That, I don’t particularly like.

(Mink, male, 27, Rotterdam, musician/student)

(T): So it [indie-folk, NvP] is pop music that is contemplated, taking into account my own limitations [giggles]. I am not extremely good, namely, in playing the guitar, so there are other things I am good at. And those are just a few things.

(N): What are those things you are good at?

(T): I can play a sort of strum or pluck the guitar in a very fast way. So, something like: ‘um te, um te, um te, um te, um te’. And then you don’t have to do a lot, but it is totally crazy. Yeah, it is not heavy finger-picking, but yeah, it is something I have practiced.

(Tessa, female, 28, Utrecht, musician)

Participatory aesthetics, in short, reflect a politics of ‘making a virtue of necessity.’ The indie-folk community distrusts the all too technical, rational, and ceremonial, while acknowledging the constraints of being unable to be involved in highly presentational performance practices (see on the difference between participatory and presentational aesthetics: Turino, 2008). Indie-folk, therefore, could be best defined as a hybrid: it has incorporated aesthetic criteria historically related to the high arts – experimentation, innovation, and economic disinterestedness on the production-side; aesthetic distancing and formalism on the consumption-side – while at the same time remaining true to a popular aesthetic which entails a vision of art that is purposeful, emotional, and socially engaged. It flirts with l’art pour l’art, yet regards music that is just being technical as too elitist or snobbish. Doing so, indie-folk adheres to the roots of folk as music of the ‘common’ man. This ultimately boils down to the conclusion that indie-folk is a ‘rising’ genre, constructed by cultural omnivores having or aspiring to high-status.

Conclusion and Discussion

This article has studied the social construction of indie-folk as a genre. Doing so, it has discussed the “double articulation” of indie-folk representing a segment of the cultural (upper) middle-class in Dutch society: first, to dominant subcultures of former generations (most notably “dogmatic” punk culture); second, and most importantly, to dominant cultures associated with high levels of economic and/or symbolic capital. It has been argued, more specifically, that the construction of indie-folk as a genre reflects the class politics of the cultural (upper) middle-class in Dutch society – more accurately, of a group of adolescents and (early) adults aspiring to high-status. This corresponds with sociological research emphasizing how, also in a postmodern condition favoring hybridity over categorization, some forms of music, like indie-folk, are an extension of community and social identity; how musical structure is homologous with social structure (cf. Hesmondhalgh, 2005).

In fact, this research has emphasized how community members, particularly those showing a strong interest in experimental music such as indie-folk, strongly criticize commercialism and homogeneity in the production and consumption of popular music. They achieve distinction by drawing boundaries around mainstream pop, hip-hop, and electronic dance and techno music. At the same time, they span boundaries both with the highbrow (notably with experimental forms of classical music) and the lowbrow (notably with country and bluegrass and electronic music), yet without turning their taste into ‘anything goes.’ They do so by consuming a broad palette of (sub-)genres within the indie music stream, which are considered to be more pure and authentic than the mainstream. Authenticity is determined by the ability of producers to create eclectic, experimental, and innovative music, and thus through the spanning of boundaries between (indie) genres. As well as by putting an emphasis on how music (particularly its lyrical aspects) is created, rather than on what the music purposefully represents. Underlying the boundary spanning activities of community members, then, is a politics of boundary policing, preventing heterogeneous taste from turning into “mono-purism” or “poly-mixing”; hence, losing its capacity to provide distinction. Indie-folk aficionados can only make their consumer practices socially meaningful when exploring multiple forms of innovative music, yet by staying within the confines of the indie music stream. This corresponds with former research indicating that cultural omnivores are tolerant towards popular and vernacular culture, while simultaneously adopting an exclusionary politics of class distinction (e.g., Johnston and Baumann, 2007). The emergence and institutionalization of indie-folk as an established genre within the indie music stream is thus part of the rise of the cultural omnivore (Peterson, 1992), yet seems to reflect a desire for something more authentic, pure, and delineated in a cultural landscape dominated by heterogeneity, diversity, and the commodification of culture.

Indie-folk, in this respect, could be seen as the product of postmodernity, a type of society characterized by increasing diversity, heterogeneity, fragmentation, and the commodification of culture, as well as by a critique of the dogmatic ideology and somewhat snobbish attitude of past subcultures. Indie-folk, however, also seems to be a response to postmodernism, for it returns to emotion, engagement, sincerity, and to either realist representations of the ‘commonplace’ and the ‘common (man),’ or to otherworldly representations of a romantic mythos, as alternative systems of meaning. The construction of such a “new seriousness” in indie-folk (cf. Hibbett, 2005) could be seen as a strategy to ‘bootstrap’ constructions of meta-authenticity and irony more common in postmodern genres such as lo-fi, grunge and self-conscious avant-garde rock and pop (cf. Hibbett, 2005). It explains the preference within the indie-folk community for participatory aesthetics, reflecting an ideology revolving around democratic values of openness, engagement, egalitarianism, and connectivity. The emphasis on participatory aesthetics in contemporary indie-folk music, however, also indicates the inability of the indie-folk community to “refract” economic capital in terms of maintaining the logic of autonomy (Johnson, 1993, p. 14). This seems to be generally indicative of the emergence of indie as a distinct domain within the global music industry, located at the interstice between the avant-garde and commercialism, and therefore forced to form commercial partnerships. Participatory aesthetics such as the use of “more poetic” language, however, require considerable amounts of cultural capital, and are only effective in the context of a community of which members possess the knowledge and knowhow to recognize and decode associated conventions. This research therefore emphasizes that a cultural (upper) middle-class taste extends in indie-folk.