Abstract

We examine the impact of tariff and non-tariff reductions on firm-level gross value of output (GVO) and productivity for various types of Indian manufacturing MSMEs for the 2002–2007 period. We merge the 3rd (2001–2002) and 4th (2006–2007) All India Census data on Indian MSMEs to create a novel dataset that includes micro-enterprises and to calculate input and final goods tariffs, ERPs and NTBs for broad product groups using information from India’s export–import policy, 1997–2003 and 2004–2009. After controlling for firm, industry, state and time-specific factors, we find tariff reductions have improved firm-level GVO and productivity for MSMEs which are technologically upgraded and quality certified. Further, the effects of input tariff reduction exceed those from final goods tariff reductions, i.e., the input sourcing channel is stronger than the final product competition channel. Liberalization of non-tariff barriers is found to have a positive effect on both GVO and productivity growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) are seen as important engines of economic growth in developing countries. According to the World Bank’s data on MSME indicators, there are 125 million formal MSMEs across 132 economies, including 89 million in emerging economies (Kushnir et al. 2010).Footnote 1 In India, the MSME segment plays a significant role, as it absorbs a large part of the low and semi-skilled workforce. There are more than 44 million MSME units producing over 6000 products and accounting for 90% of all industrial units in India (Grant Thornton and FICCI 2013). Based on the latest Annual Report of the Ministry of MSMEs, it is estimated that MSMEs accounted for 33% of total manufacturing output and for 6% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2014–2015.Footnote 2 They contributed to 45% of the country’s exports in 2014–2015. Sectors such as textiles, leather and food products, which constitute a significant share of India’s export basket, are dominated by MSMEs (Singh et al. 2010b).

Until 1991, India’s MSME segment remained protected by high levels of tariff and non-tariff barriers (Das 2008). However, since 1991, Indian industry, including the MSME segment, has faced extensive trade liberalization with a significant reduction in import tariffs on final as well as intermediate products and the removal of quantitative restrictions on a large number of import items (Singh et al. 2010b). Average tariffs (MFN applied rates) declined from 86.82% to 14.57% between 1990 and 2009 and the non-tariff barrier coverage ratio, i.e., the share of imports subject to non-tariff restrictions, fell from nearly 100% to 0% over this period.Footnote 3 Moreover, items that were previously reserved only for MSME production (Singh et al. 2010a) have been de-reserved over time along with the lifting of import prohibitions.Footnote 4 As a result, Indian manufacturing MSMEs have faced growing competition from foreign and domestic sources.

It is widely held that Indian MSMEs have had difficulty in confronting the competitive challenges posed by trade liberalization and have failed to take advantage of the new opportunities arising from liberalization, due to various constraints such as scarcity of financial resources, outdated technology, poor quality of products and lack of modernization (Grant Thornton and FICCI, 2013; Government of India 2013; Gyampah and Boye, 2001). As a result, the MSME segment’s contribution to India’ GDP and to its manufacturing output has declined over the years. However, as MSMEs continue to absorb the largest proportion of the labour force after agriculture, ensuring their growth and enabling them to confront increased domestic as well as international competition remain critical challenges for policy makers in India (Government of India, 2013). A district-level study by Martin et al. (2017) shows that national small-scale industry (SSI) reservation policies have over the years hindered overall output and employment growth in India. Against this backdrop, understanding the impact of trade reforms on MSMEs and the factors mediating this relationship assumes importance.

This paper examines the impact of trade liberalization on the performance of Indian manufacturing MSMEs. The analysis focuses on two key performance measures, namely, growth in the gross value of output (GVO) and growth in total factor productivity (TFP). We examine the impact of a reduction in both tariff and non-tariff barriers (NTB) on both these performance measures, in the context of India’s trade policy (EXIM Policy) of 1997–2003 and 2004–2009.Footnote 5 We also examine how this impact varies with MSME characteristics, such as whether they use modern power sources, have advanced technological knowledge, maintain product quality standards, and whether they are sick units.Footnote 6

The analysis in this paper is placed within the broader literature on new–new trade theory by Melitz (2003), Costantini and Melitz (2008), Bernard et al. (2003), which highlight the role of firm heterogeneity in shaping the impact of trade policy. It also builds on the existing literature on Indian manufacturing, including studies such as Goldar and Kumari (2003), Das (2004), Balakrishnan et al. (2006), Sivadasan (2009), Topalova and Khandelwal (2011), Loecker et al. (2016), Hasan (2002), Bas and Berthou (2011), Ahsan (2013), Mallick and Marques (2008), Kato (2009), Goldberg et al. (2010a), Kathuria (2002) and Parameswaran (2010), and reconfirms the role of factors such as the level of technology, extent of modernization and access to credit on firm and industry-level performance following trade liberalization. It also extends the findings of studies such as Nataraj (2011) and Kathuria et al. (2012) on trade liberalization and TFP in Indian manufacturing by showing that tariff liberalization has had a differential impact on MSMEs depending on their firm-level characteristics.

This paper makes three important contributions to the literature. First, it not only examines the effect of trade liberalization on the performance of MSMEs but also tries to identify the various channels for this impact, i.e., whether this is through tariff reductions on final goods or inputs or due to the reduction in NTBs. Moreover, it also assesses the relative importance of these various channels of impact. Second, this paper specifically calculates the actual incidence of NTBs for different industries (as opposed to just categorizing industries as having high and low NTB protection as done in some earlier studies). It examines the effect of the level of non-tariff protection on the output and productivity growth of Indian MSMEs. Finally, and most importantly, this paper undertakes analysis based on a new dataset that has been created by the authors by merging the 3rd and 4th All India Census data on Indian MSMEs for the years 2001–2002 and 2006–2007.Footnote 7 This merged dataset is being used for the first time in such empirical analysis and contains information on a panel of close to 10,000 unique MSME firms, including a large number of micro-enterprises, for the two census years. It includes information on financial variables such as access to credit as well as on product and industry characteristics such as quality standards, technological knowhow and power source at the firm-level.Footnote 8 This dataset enables us to track the performance of a large number of MSMEs, including micro-firms, over a time period that has witnessed significant trade liberalization in India, while controlling for important firm-level characteristics which are available in the Census dataset.Footnote 9 The conceptual flow for the analysis carried out in this paper in terms of the various channels of impact and the performance variables under examination is represented in Fig. 1.

The plan of the paper is as follows. “Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics” discusses the data sources and key descriptive statistics. “Methodology and Measurement Issues outlines the methodology used for the empirical analysis and discusses measurement issues. “The Estimation Strategy and Analysis” presents the estimation strategy and analysis of the results, and also summarizes the key findings. “Robustness Checks” discusses the difference-in-difference (DID) model for robustness analysis, and finally, “Summary of Findings: Policy Interferences and Extensions” concludes the paper with some policy recommendations and possible future extensions of this research.

Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

Data Sources

We merge the All India 3rd Census Survey data on MSME registered firms (2001–2002) with the All India 4th Census Survey data on MSME registered firms (2006–2007).Footnote 10 This gives us a set of unique Indian MSME firms over the 2002–2007 period with useful firm-level information for this period, such as GVO, total inputs used, total fixed assets, age, total employment, institutional loan outstanding, etc. This exercise enables us to comprehensively examine the performance of these MSME firms in the context of trade liberalization and the various mediating firm and industry-level factors.

In addition to the firm-level data, we have also extracted information on industries and trade restrictions from other sources. Industry-level information is extracted from the Industry Analysis Service and the Economic Outlook, the two online databases provided by the CMIE. Tariff-related information is obtained from the TRAINS-WITS online database provided by the World Bank. We measured the NTB index data by using the import conditions data from the Director General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) database, and the import data from the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Department of Commerce, Government of India.Footnote 11

Overview of the Merged Census Dataset

We next discuss the creation of this merged dataset and summarize the key firm-level features revealed by this collated census data. For merging and identifying the unique firms from these two censuses, we take the following steps. Firstly, we observe that each firm has a permanent registration number. These permanent registration numbers repeat within a specific state, district, tehsil, taluk or mandal and even town or village.Footnote 12 Thus, we create a combination number by considering all these varying area-level subcategories, starting from a sector code (i.e., rural or urban) to a town or village code, and the permanent registration number assigned to each firm. We repeat this procedure for both the 3rd and 4th Census MSME firm-level datasets to arrive at a set of unique firms which are present in both the survey rounds. Finally, we merge these two firm-level datasets based on the unique firm code that we generate using the aforementioned combination number. This exercise is mainly carried out to track firm-level performance of Indian registered MSME firms over the 2002–2007 period, through a comprehensive examination of different firm-level performance indicators for this unique set of registered MSME Indian firms. We confirm the accuracy of this merging procedure and the uniqueness of the firms across both survey rounds by checking the uniqueness in a firm’s permanent registration year and its 5-digit NIC code across the two Census datasets.Footnote 13 We finally arrive at 9918 unique MSME firms in our merged dataset.Footnote 14 The accuracy of this merging procedure was validated by the Indian Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.Footnote 15

We provide here some of the descriptive statistics for the merged census data to provide an overview of some key characteristics of the registered MSME firms covered in this dataset as well as their distribution across various dimensions of performance and operation. The latter helps provide a context to the overall discussion by defining the kinds of firms that are being studied and also highlights the potential role of various firm-level characteristics in determining the impact of trade liberalization within the MSME segment. An important point to note is that this dataset captures registered MSMEs as opposed to unorganized firms. By focusing on registered MSMEs, we are able to capture that segment of firms for which data have been systematically captured across a range of industries and firm-level characteristics, and which are directly used in policy formulation. While registered MSMEs form only 4.4% of the total number of MSMEs, they account for 66% of the GVO of the entire MSME sector in India, thus justifying our focus on this segment.Footnote 16 Table 1 provides the average values for the MSME firms for various firm features. An interesting feature to note is that while per unit gross output has increased between the 3rd and 4th Censuses, the efficiency of investment as indicated by the value of gross output relative to fixed investment has declined over the two Censuses.

In addition to the characteristics highlighted in Table 2, it is interesting to note certain other features of these firms. The state-wise distribution of these MSMEs in the Census dataset reveals that a sizeable proportion (around 50%) of them are located in some of the backward and less industrialized states, such as Bihar (8.4%), Madhya Pradesh (18.55%), and Rajasthan (9.74%), while some of the leading industrialized states such as Gujarat and Maharashtra account for a very small share of the firms in this dataset.Footnote 17 In terms of industry distribution, the MSMEs are highly concentrated in a few industries, namely, the food products, beverages and tobacco industries (33.2%), the paper and paper products industries (29.8%), miscellaneous manufacturing industries (14.1%) and mineral and metal (12.6%) products industries. The regional and industry-wise distributional characteristics of MSMEs indicate the likely differential impact of policy changes like trade liberalization on these firms.Footnote 18

The merged Census dataset also highlights other important firm-level features used in our model, such as firm-level performance indicators (GVO and TFP), controls (total asset and employment) and other categorical indicators (access to technological knowledge, type of power source used, quality certification status, credit status and sickness status). Tables 2 and 3 provide these descriptive statistics.

We find that the bulk of registered MSMEs are characterized by limited technological knowledge, poor access to credit and poor-quality standards and a large number (around one-third) either do not use power sources or use traditional sources of power. Some of these MSMEs are sick units.Footnote 19 These characteristics highlight the types of competitive challenges that confront registered Indian MSMEs (and also unorganized/informal MSMEs) underscoring the need to focus separately on the MSME segment to assess the impact of trade reforms.

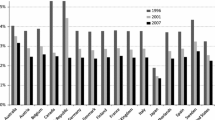

Overview of the Trends in Tariffs

The tariff data extracted from the TRAINS-WITS online database presented in Table 4 highlights the significant reduction in final goods tariffs in many industries between 2002 and 2007, i.e., the period under study. It further reveals the varying degree of tariff liberalization across different industries. While the average tariff rate in the low protection industries fell from nearly 30% to a little over 11% between 2002 and 2007, in the high protection industries, the average tariff rate declined only marginally from 36% to 32%. Within the low protection industry group, some industries experienced sharp reductions in tariffs from around 30% to single digit in some cases. In general, the food and agro-based industries have remained relatively more protected than the majority of non-food, non-agro-based manufacturing industries.

The asymmetric nature of tariff liberalization across industries with very different levels of protection coupled with the broad overall trend of tariff reductions validates the choice of the study period and indicates the likely differential impact of trade reforms on MSMEs based in different industries. Overall, the above overview of the descriptive statistics for MSMEs and the tariff trends and variations across industries motivates the need to focus on firm- and industry-specific characteristics of MSMEs in examining the impact of trade liberalization.

Methodology and Measurement Issues

We undertake a fixed effect regression analysis of the impact of trade liberalization on firm-level performance indicators such as the growth of deflated GVO and productivity for 2001–2002 and 2006–2007, after taking into account different firm-level and state-level unobserved heterogeneity.Footnote 20 We regress these performance measures on different industry-level trade liberalization indicators, namely, input and final goods tariffs, the effective rate of protection and NTBs. This approach helps us to identify the effects of tariff policy on the performance of different types of MSME firms, as characterized by features such as whether or not they are organized, whether or not they are sick units, whether they use electric or nonelectric sources of power, their ability to access credit, and whether or not they are quality certified as well as the relative importance of these different types of protection.Footnote 21 This fixed effect methodology is firstly applied to all MSME firms and then repeated for the different sub-groups based on the aforementioned firm-specific characteristics.Footnote 22

The empirical analysis requires the measurement of three key variables, namely, productivity, tariff and NTBs. The methodology involved in measuring these variables is discussed next.

Productivity Measures

In order to capture industry-level unobserved productivity shocks, we calculate firm-level TFP for the 9581 registered MSME firms in the merged dataset and examine how their productivity has been affected by trade liberalization. For this purpose, we follow the semi-parametric methodology of Levinsohn and Petrin (2003) for measuring firm-level TFP of different MSME firms. We take the value of deflated firm-level total intermediate inputs as a proxy for the unobservable productivity shock and correct for simultaneity in a firm’s choice of output and input levels in its production function.

Following the assumption of a Cobb–Douglas production function, we represent below a log linearized output function for firm i in industry j at time t as follows:

where y denotes output (measured in terms of the firm’s GVO), l denotes labour (measured in terms of the total number of labour employed), m denotes total input expenditures, and k denotes capital used (measured in terms of total fixed assets). In the above regression equation, all the variables are taken in natural log form. We calculate wijt, which is the firm-specific, time varying unobservable productivity shock based on Levinsohn and Petrin (2003).

We deflate the GVO, total fixed assets and total input expenditure as proxies for the physical quantities of output, capital and intermediate inputs, following the literature on productivity estimation.Footnote 23 We deflate GVO, capital employed and total input expenditure by using industry-specific wholesale price indices, collected from the Economic Adviser, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, using 2004 as the base year.Footnote 24

By using the firm-level panel data on deflated GVO and other input expenditures for the periods 2000–2001, 2001–2002 and 2006–2007, we estimate their respective coefficients by using the methodology of Levinsohn and Petrin (2003).Footnote 25 The above estimation result is given in Table 5 for all MSME firmsFootnote 26:

After getting all the estimated coefficients, we calculate TFP for the ith firm in the jth industry at time t by using the following equation:

After getting the Hicks-neutral TFP, we also create the productivity index following the methodology of Aw et al. (2001).Footnote 27 This is done to make the estimated TFP comparable across industries. Table 6 gives the detailed calculation for the productivity index:

To make sure that the extreme outliers do not affect the analysis, we also trim the top and bottom 1% of the productivity index.Footnote 28

Tariff and Non-tariff Barriers Measures

We calculate the input tariff, the effective rate of protection (ERP) and NTBs (NTBs) for all the 17 2-digit broad industry groups (based on ISIC revision 3 or NIC-2004).Footnote 29 To analyse the effects of trade liberalization on firm-level performance for Indian MSME manufacturing firms, which belong to these 17 industry groups, we calculate the input tariff and ERP for all the 17 industries based on final goods tariff data and input–output data collected from the WITS database and the OECD-STAN database, respectively.Footnote 30 We also calculate NTBs for all these 17 industries based on the data for import conditions (import policy) for each 8-digit product group and the import data for each 2- and 8-digit product group, collected from the DGFT database, Government of India and the Ministry of Commerce and Industry database, Department of Commerce, Government of India, respectively.Footnote 31 The detailed calculation of all these aforementioned trade indicators is given in Appendices B and C. Along with the aforementioned protection indicators, we also calculate the industry-level export propensity for all these 17 2-digit industry groups (NIC 2004) using Eq. (3) based on the industry-level export data collected from the WITS-UN COMTRADE database (World Bank) and the GVO data from the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) database.Footnote 32

where j = industry and t = time.Footnote 33

The Estimation Strategy and Analysis

Model Specifications

As outlined earlier, the main objective of this study is to determine the effects of trade liberalization on firm performance, to understand how this impact differs across different types of MSME firms and to assess the relative significance of various forms of trade liberalization, i.e., input, final goods and non-tariff liberalization, in shaping this impact. The fixed effect (2N) models for the effect of tariff liberalization on firm-level GVO and productivity are specified in Eqs. (4) and (5), respectively. The fixed effect (2N) models for the effect of non-tariff liberalization on firm-level GVO and productivity are specified in Eqs. (6) and (7), respectively.

where, i = manufacturing (MSMEs) firms, j = industry and t = time.

In both these models, the firm-level GVO is deflated by using the industry-level WPI deflator. We take the dependent variable, GVO, in natural log form and also control for firm, year and state × year fixed effects, firm size (proxied by a firm’s total fixed assets), total employment, institutional loans outstanding (to proxy access to credit) and industry-level export propensity, apart from the main variables of interest which are the lagged tariffs and the NTB Index. In the fixed effect models for productivity, we control for firms’ institutional loans outstanding and industry-level export propensity, firm, year and state × year fixed effects, apart from the lagged tariffs and NTB index, which are our main variables of interest.Footnote 34 It is expected that tariff and non-tariff liberalization would improve the performance of MSMEs in terms of GVO and productivity. This implies negative coefficient values for the tariff liberalization indicator, i.e., a lower tariff resulting in better performance, and positive coefficient values for the non-tariff liberalization indicator, i.e., a higher NTB indicator (which represents a lower incidence of NTBs)Footnote 35 resulting in better performance. Increased firm size, employment and access to credit are expected to improve MSME performance, implying positive coefficient values for the aforementioned indicators for firm characteristics. Industry-level export propensity is expected to result in increased competition and thus a decline in MSME performance, implying a negative coefficient value for this industry characteristic.

In order to validate the robustness of our specification, we also test for possible endogeneity between performance measures, such as GVO and productivity and trade policy (captured by the input, final goods and ERP tariff measures), which could arise from the industry’s previous period GVO and productivity status affecting the level of trade protection. We find that trade policy is not affected by past period firm-level output or productivity.Footnote 36

Results and Interpretations of the Fixed Effect Models

This section discusses the results of the fixed effect models on firm-level GVO and productivity. As discussed earlier, we use these models to first assess the impact of trade liberalization on these performance measures for all MSME firms, and then to assess the impact on these same performance measures for subgroups of MSME firms which differ in terms of their production and operating structure (i.e., whether they use modern power sources, have quality certification, and have upgraded technology) as well as their financial health (i.e., whether or not they are sick firms).Footnote 37

Tariff Liberalization and Firm-Level Performance

We present the results of the models specified in Eqs. (4) and (5) for the impact of final goods and input tariff liberalization on firm-level performance. The results are discussed along four dimensions, i.e., the role of selected firm-level characteristics in shaping the impact of tariff reductions, including the relative importance of these firm-specific characteristics; the role of selected control variables in mediating the relationship between tariff reductions and firm-level performance; the relative importance of final goods versus input tariff liberalization; and the commonalities and differences in the results obtained for GVO growth and productivity. Tables 7 and 8 show the effects of a reduction in lagged final goods tariffs and lagged input tariffs, respectively, on firm-level GVO and productivity. Table 9 presents the results for the combined effect of both lagged final goods and input tariffs on firm-level GVO and productivity while Table 10 provides the results for the ERP on firm performance. In all the tables, Panel 0 (Column 1) represents the results of the fixed effect (2N) models for all MSME firms. The different kinds of firm characteristics discussed above are represented in Panels 1–4. In each of the regressions (Columns 1–8), the standard errors are clustered at the firm-level. It should be noted that, as the number of observations is limited for some of the MSME sub-groups, we have not controlled for state–year effects in order to avoid the degrees of freedom problem. However, when dealing with the full sample (Tables 11, 12, 13), we have included state–year effect to control for any macro-economic shocks (i.e., any state- and year-specific policy changes) which might affect our main results. Hence, we ensure the robustness of our main findings.

The results in Table 7 indicate that final goods tariff liberalization has not had any significant impact on GVO growth or productivity for MSMEs as a whole. However, the impact varies depending on MSME characteristics. MSMEs which have quality certification and are technologically upgraded have significantly benefited, while their counterparts have been adversely affected. A 1% decrease in the final goods tariff has increased the firm-level GVO by 2.1% and 2.4% for technologically advanced MSMEs and quality certified MSMEs, respectively, while this same tariff reduction is associated with a decrease of 0.4% and 0.1% for their respective counterpart firms. We can thus broadly infer that firms which have modernized and become technologically more efficient have been better able to cope with increased product competition following tariff liberalization. The direction of the results is broadly similar in the case of productivity, though the coefficients are largely insignificant.

Table 8 presents the results for the impact of input tariff liberalization on firm performance. We find that the impact has been consistently positive and significant for all MSMEs and also for certain types of MSMEs. A 1% reduction in input tariffs is associated with an increase of 0.5% in firm-level GVO of all MSMEs, especially those which are not sick units, and an even higher increase for those MSMEs which use electricity (2.4%), which have quality certification (6.4%) and are technologically upgraded (3.2%). Hence, we again observe that those MSMEs which are modern and formal in their production and operating structure have benefited more from input tariff liberalization, while their less organized and less modern counterparts have either not benefited significantly or have been adversely affected. A similar result is obtained in case of productivity with regard to MSME characteristics. In particular, we find firms with quality certification have experienced significant benefits from input tariff liberalization, indicating that maintaining quality helps firms to derive productivity improvements through imported intermediate inputs.

A comparison of the results in Tables 7 and 8 further reveals that the impact is consistently larger and more significant in the case of input tariffs compared to final goods tariffs for both firm-level GVO and productivity. Hence, the input sourcing channel following input tariff reductions has been stronger than the competition channel arising from final goods tariff reductions. The positive and much stronger impact of input tariff liberalization may be explained by the improved access to a larger scale, variety, possibly better quality and reduced costs of imported intermediate inputs. Further, a reduction in input tariffs increases access to imported inputs which embody imported technology, thus enabling the transfer of technology and R&D spillovers. This provides firms with an opportunity to upgrade technologically and compete in a sustained manner on the basis of quality, product differentiation and innovation, rather than on the basis of price competitiveness alone which is made possible by output tariff reduction. Input tariff reduction also exerts pressure on the domestic input industry (import competing) to become more efficient. This finding is consistent with a Government of India (2013–2014) Annual Report of the Ministry of MSMEs which specifically notes the importance of technology for the MSME segment and highlights the difficulties faced by MSMEs in acquiring technologies due to their size, thus preventing realization of economies of scale and aggravating competitive challenges from imported items.

Our findings regarding these gains from imported inputs are in line with the endogenous growth literature by Grossman and Helpman (1991), Ethier (1979, 1982), Rivera-Batiz and Romer (1991), which highlight the role of foreign intermediate inputs in enhancing growth. These gains have also been highlighted in several theoretical and empirical studies by Lee (1995), Eaton and Kortum (2001), Goh and Olivier (2002), Xu and Wang (1999) and Alfaro and Hammel (2007), which discuss the effect of liberalizing trade in intermediate and capital goods sectors on firm-level performance. Our results also confirm empirical analysis along similar lines for Indian manufacturing firms as a whole by Topalova and Khandelwal (2011), Goldberg et al. (2010a, b), Loecker et al. (2016), Mukherjee and Chanda (2016, 2017) on the significance of input liberalization for firms in the textile industry. These latter studies find an increased probability of importing capital goods for the average firm, a positive effect of input tariff cuts on the intensive margin of imports of capital goods, and a positive effect of input-trade liberalization on firms’ sales, firm productivity growth and firms’ ability to introduce new products. Our results are also in line with the findings of Nataraj (2011), where productivity gains are observed for large-formal firms following trade liberalization. We find that, even within the MSME segment, the more modernized, technologically adept and quality conscious MSMEs have been able to realize the benefits of input tariff liberalization while their counterparts have in fact been adversely affected.

The results obtained for the various firm- and industry-level control variables are significant and of the expected signs in case of both final goods and input tariff liberalization. MSMEs that are larger, as proxied by employment and fixed assets, and MSMEs which have greater access to credit, as proxied by institutional loans outstanding have experienced higher firm-level GVO. Likewise, MSMEs with better access to credit have performed better on the productivity front. Uniformly, greater export orientation at the industry-level has a significant and negative impact on both firm-level GVO and productivity, probably indicating the fact that firms in more export-oriented industries are likely to face greater competition than firms in inward-oriented industries. However, it is interesting to observe that the coefficients are larger and more significant in the case of less modernized, less technologically upgraded and less quality conscious MSMEs, suggesting that such MSMEs in export-oriented industries have been more adversely affected than their progressive counterparts One can thus infer that the more progressive MSMEs have been better able to cope with the competitive pressures arising from tariff liberalization.

Our results regarding the importance of firm-sizeFootnote 38 in shaping the benefits of trade liberalization confirm the findings of earlier studies such as Singh et al. (2010b) regarding the heterogeneous effect of trade liberalization on firms’ technology and product choice, and the importance of firm-level characteristics in shaping the performance of Indian MSMEs.Footnote 39 We can thus infer that larger MSMEs are more likely to have captured the benefits of trade liberalization, reflecting the advantages they possess over smaller ones, in terms of technology, scale economies, quality, and access to credit, among other factors. Studies on Indian manufacturing across industries have also highlighted the importance of credit conditions, technology, assets, among other firm-level characteristics in influencing firm-level performance, and our findings confirm the same.

Our results hold even when both input and final goods tariffs are included in a single regression, as shown in Table 9. A reduction in final goods tariffs has a negative and significant impact while a reduction in input tariffs has a positive and significant impact on firm-level GVO. Once again, MSMEs with access to technological knowhow, with quality certification and modern production methods and without sickness problems, benefit more from input tariff liberalization and are less adversely affected for the most part from final goods tariff liberalization, indicating that the more modern and technologically upgraded firms are in a position to realize the sourcing-related gains from trade liberalization and to face increased competition arising from final goods tariff liberalization. The results for productivity are weaker than for firm-level GVO but again we find that firms which are able to maintain their product quality standards are associated with a positive impact on productivity due to a reduction in input tariffs. Thus, combining input and final goods tariffs in a single regression does not alter the nature of our earlier findings and again underscores the relative importance of the input sourcing channel for gains from trade liberalization.

We finally examine the net effect of liberalizing final goods and input tariffs, i.e., the effect of changes in the ERP on firm-level GVO and productivity. This is motivated by the fact that there are differing effects on firm performance in terms of the magnitude, significance level and signs of the coefficients in the case of final versus input tariff reductions. This is once again done for MSMEs as a whole and then for specific kinds of MSMEs. The results of this exercise are provided in Table 10.

We find that a reduction in ERP is associated with an insignificant effect on firm-level GVO and productivity, reflecting the opposing effects of final versus input tariff liberalization. However, as seen earlier, when we consider the results for different kinds of MSMEs, for MSMEs which are technologically upgraded and have obtained quality certification, we observe a beneficial and significant impact of a reduction in the ERP on GVO and an adverse effect on their counterpart firms. The results for productivity remain by and large insignificant, though for the modern, upgraded and quality conscious MSMEs, the effect is positive. Thus, technology adoption and quality certification again emerge as two important firm-specific characteristics which enable MSMEs to, on net, benefit from trade liberalization.

Overall, our results for the effects of tariff liberalization on firm-level performance across Tables 7, 8, 9, and 10 indicate that Indian MSMEs as a whole have not benefited much from tariff liberalization in terms of either output or productivity growth. However, those MSMEs which are characterized by modern operating and production structures have fared better and have been able to withstand competitive pressures arising from tariff liberalization. Both firm and industry characteristics have played a role in mediating the impact of tariff liberalization.

To ensure the robustness of our above findings, we also extend our analysis to the full sample, by introducing an interaction term for various broad firm characteristics and the trade policy indicators (i.e., Tariff × Modern Power Source Dummy, Tariff × Maintaining Quality Standard Dummy, Tariff × Maintaining Modern Technological Dummy, Tariff × Sick-MSME Dummy) and state–year interaction effects (Table 11). Here, we examine whether Indian MSMEs have experienced an improvement in their GVO and productivity following a reduction in input, final goods and effective rate of protection, when we control for the broad differences in firm characteristics and any other unobserved macro-economic shocks (i.e., state- and year-specific any policy changes during the study period) which might affect our main results.

The coefficients for the final goods tariff variable in Columns 1 and 5 clearly indicate that, although the inclusion of various interaction terms does not change the results for GVO (Column 1), there has been a significant and positive effect (i.e., 1.24%) on firm-level productivity (Column 5) of a 1% reduction in final goods tariff. This highlights the importance of various firm-specific factors and state–year policy effects, which can influence the impact of tariff liberalization on the performance of Indian MSMEs. We find similar results in the case of input tariffs and ERP wherein the impact of liberalization remains positive for both GVO and productivity but becomes much stronger in the case of productivity compared to our baseline results presented earlier. The latter suggests that industry-specific shocks as well as macro-economic policies and programs (which are captured by the state–year interaction effects) that are designed to alleviate the problems of the manufacturing sector, or of MSMEs in particular, can help firms to realize gains in GVO and productivity from tariff liberalization. So, the existing industry and policy context is important in shaping the impact of tariff reductions on Indian MSMEs. In this regard, initiatives such as The National Manufacturing Competitiveness Programme, micro-& Small Enterprises Cluster Development Programme, Technology Centre Systems Programme, Credit Linked Capital Subsidy Scheme, Entrepreneurship and Skill Development, Rajiv Gandhi Udyami Mitra Yojana, Market Development Assistance Scheme, etc.Footnote 40, which aim to address the problems of Indian manufacturing firms and especially Indian MSMEs, can play an important role. Importantly, the results in Table 11 again confirm our main findings and highlight the relative importance of the input sourcing channel for gains from trade liberalization. Our results hold when both input and final goods tariffs are included in a single regression, as shown in Table 11 (Columns 4 and 8). Similar to our earlier findings, Column 4 shows that a reduction in final goods tariffs has a negative and significant impact while a reduction in input tariffs has a positive and significant impact on firm-level GVO. Moreover, a 1% point reduction in input tariffs improves productivity by 1.98%, while a reduction in final goods tariffs fails to affect firm-level productivity.

Non-tariff liberalization and firm performance

We also examine the effects of a reduction in NTB barriers, as measured by an NTB liberalization index, on firm-level GVO and productivity for all MSMEs. The measurement of this index is as outlined earlier in “Tariff and Non-tariff Barrier Measures” and illustrated in Appendix C. We observe that there is an upward trend in this index, i.e., liberalization trend, over our study period.Footnote 41 The results are presented in Tables 12 and 13. Columns 1 to 5 in Panel 1 represent the impact of reductions in final goods tariffs, input tariffs, ERP, the combined case of final goods and input tariffs, and NTBs, respectively, on firm-level GVO. Columns 6 to 10 in Panel 2 represent the impact of these same reductions on productivity.

Although we do not assess the effects for different MSME subgroups, the results for all MSMEs presented in Tables 12 and 13 highlight two important features regarding the impact of non-tariff liberalization. First, we observe that NTB liberalization, like tariff liberalization, impacts only firm-level GVO positively and significantly at the firm-level across all MSMEs, while for productivity growth the impact is insignificant (see Table 12). The results are also significant and stronger for NTB liberalization compared to input tariff liberalization which was earlier found to be the main source of gains. When the effects of both tariff and non-tariff liberalization are considered simultaneously in the same regression, we observe that the latter is not only consistently beneficial for firm performance (Table 13) but is also more significant than a reduction in any form of tariff liberalization (input, final goods, ERP) for both output growth and productivity. Furthermore, in contrast to the case where individual tariffs are assessed for their impact (Table 12), in the combined tariff and non-tariff liberalization estimation (Table 13), we find that the relative importance of input tariffs declines while that of final goods tariffs and of NTBs increases. This suggests that the removal of quantitative restrictions has played an important role in enabling MSMEs to improve their output and productivity, even though there is not much variability in the NTB index values calculated.Footnote 42 Finally, firm-level characteristics such as size and access to credit have a positive and significant effect on firm-level GVO and productivity while industry features such as export propensity continue to have an adverse and significant effect on firm performance. Hence, the role of these firm and industry features remains similar, regardless of the nature of trade liberalization.

Overall, the stronger results for NTBs compared to tariffs across all MSMEs is possibly due to the significant NTB liberalization observed across all industry groups following the dismantling of quantitative restrictions and import licensing across a wide range of industries post-2001. This is in contrast to the case of tariff liberalization where there has been a lot of variation in the extent of liberalization between different industry groups, which may explain the mixed results observed for tariff liberalization.Footnote 43 Our results also indicate that increased availability of imported inputs and final goods due to NTB reduction has been more important for firm-level performance compared to the price wedge effects driven by tariff reductions.

Robustness Checks

In our earlier discussion on estimation strategy and analysis in “The Estimation Strategy and Analysis”, it was shown that, during our study period, productivity does not suffer from an endogeneity problem, which was also indicated in Appendix Table 23. We further validate this finding by undertaking a robustness analysis of our main results by using a DID approach to estimate the differential impact of a major trade policy change that happened in Indian manufacturing industries during the study period (i.e., EXIM Policy, 2004–2009) on the firm-level performance of Indian Manufacturing MSMEs, after controlling for any endogeneity problems with respect to policy formulation for various industry groups.Footnote 44 The latter may arise from an omitted variable bias created by unobserved variables such as lobbying by industries to manipulate policy makers so as to influence the formulation of tariff policies in their favour.Footnote 45 Thus, to overcome this potential bias, we estimate the mean difference of the treatment effect (i.e., EXIM Policy, 2004–2009) in the performance of Indian manufacturing MSME firms between two broad industry groups, namely, non-food and non-agro-based industries (termed the control group) and food and agro-based industries (termed the treatment group) before (i.e., in the year 2001–2002) and after (i.e., in the year 2006–2007). The firm-level performance indicators for analysis are log (GVO) and TFP. Thus, DID estimation enables us to determine the unbiased impact of EXIM Policy 2004–2009 (treatment) on the mean difference of the firm-level performance between food and agro-based MSMEs and non-food and non-agro-based MSMEs post-2004, after keeping all firm characteristics orthogonal to the treatment effect on firm performance.

This DID methodology is first applied to all firms in the dataset and then repeated for different sub-groups of firms based on their firm-specific characteristics, such as whether or not they use modern power source, whether or not they use modern technology, whether they have product quality certifications, etc. (see Table 14). We have extended this robustness analysis by performing the DID model again for the full sample after controlling for all possible state × year-specific unobserved macro-economic heterogeneity as well as firm-characteristics and trade indicator interaction effects (see Table 15). The results for both the DID models are broadly in line with our main results and findings which were highlighted in “The Estimation Strategy and Analysis”, thus confirming the robustness of our model specifications.Footnote 46

Given the above robustness check scenario, individual-level panel data is a useful tool for estimating policy effects. Simple, effective models in the case of our study are given as follows:

where, i = manufacturing (MSMEs) firms, j = industry, t = time, and τ = treatment effect.

Postt is a dummy taking the value 1 in the post-treatment period (i.e. year 2006–2007) and 0 in the pre-treatment period (i.e. the year 2001–2002). The term (Food_Agro × Post)jt denotes the interaction between the Food and Agro-based industry dummy (group dummy) and the Post dummy. The term (State × Year)jt which denotes the interaction between the state dummy and the year dummy, has been used to control for any unobserved macro-economic shocks that can influence our results. The firm fixed effect is denoted by ci. Moreover, we include firm-level total fixed assets (as a proxy for firm size), total employment and institutional loan outstanding (as a proxy for a firm’s access to credit) as the control variables in the model.Footnote 47

From the above model, we estimate the differential effects of tariff reduction (treatment) on firm-level performance in India’s MSME sector, following implementation of the EXIM policy 2004–2009. We find the mean difference of the firm-level gross value of output and productivity between the group of firms, which come under the treated industry (i.e., food and agro-based industry) and the group of firms, which come under the untreated industry (i.e., non-food and non-agro-based industry).

Results and Interpretations of Difference-in-difference (DID) models

We examine the effects of implementing the EXIM policy 2004–2009 on firm-level GVO and firm-level total factor productivity. Moreover, we also examine the difference in these effects across different groups of firms and industry (food and agro-based vs. non-food and non-agro-based).

Table 14 presents the results of the DID models on log (GVO) and Productivity for all firms in Column 1 (Panel 0). Next, we present the results of sub-samples based on their broad firm-specific characteristics in Panels 1 to 4. In Column 1, the coefficients of Post_2004 dummy (Rows 1 and 8) provide evidence of a definite significant and positive effect of EXIM Policy, 2004–2009 in improving firm-level GVO and productivity for all MSME firms. More importantly, the coefficients of the Post-2004 × Food and Agro-based Dummy highlight that food and agro-based MSME firms experienced 0.080% and 0.667% lower firm-level GVO and productivity compared to the non-food and non-agro-based MSME firms. This indicates that food and agro-based MSME firms realized less improvement in their GVO and productivity following tariff reductions, as they remained relatively protected compared to their non-food and non-agro-based counterparts. If we compare the coefficients of the Post_2004 dummy for both the GVO and Productivity models in Table 14 across sub-samples, based on broad firm-specific characteristics (see Panels 1 to 4, Rows 1 and 8), we find clear evidence of relatively higher firm-level performance with respect to GVO and Productivity for MSMEs which are not sick units, which use modern power sources in their production, which maintain product quality standards and are technologically advanced. For instance, if we compare Columns 6 and 7 in Panel 3 with respect to the coefficients of the Post 2004 dummy, we find evidence of a greater impact of EXIM Policy, 2004–2009 on firm-level GVO and productivity to the extent of 0.257% and 1.343%, respectively, post-2004 for MSMEs which maintain product quality standards compared to their low-quality counterparts. Further, if we compare Columns 8 and 9 in Panel 4 with the coefficients of the Post-2004 dummy, we find evidence of a greater impact of EXIM Policy 2004–2009 (0.252% vs. 0.113%), on firm-level GVO and productivity post-2004 for technologically advanced MSMEs compared to their less advanced counterparts.

Although Table 14 confirms the robustness of our main model specifications, it is possible for firm characteristics and trade policy interaction, as well as the state–year unobserved interaction effects to influence our main results. Hence, in Table 15, we present the results of the DID model for all MSME firms, after controlling for all other unobserved macro-economic policy effects.

In Table 15, Panels 1, 2 and 3, we present the results of our DID model on firm-level log (GVO) and productivity, after controlling for all broad firm characteristics and final goods tariff interaction, Input tariff interaction and ERP interaction, respectively, apart from controlling for other firm-specific time invariant unobserved heterogeneity as well as state–year unobserved interaction effects. Similar to our results in Table 14, we find that the coefficients of the Post_2004 dummy are highly significant and positive across all panels (i.e. for Rows 1 and 12) which reconfirms the positive effects of EXIM Policy, 2004–2009, on firm-level GVO and productivity following a reduction in tariff rates across industry groups over time. Moreover, the negative and highly significant values for the coefficients of the (Post-2004 × Food and Agro-based Dummy) interaction dummy across all panels (i.e. for, Rows 2 and 13), again supports the evidence of lower mean firm-level GVO and productivity for the food and agro-based MSME firms compared to the non-food and non-agro-based MSME firms post-2004 period. For instance, the estimates of the coefficients of the (Post-2004 × Food and Agro -based Dummy) interaction dummy in Column 1, clearly show that the food and agro-based MSME firms are less affected (0.056% as seen in Row 2 and 0.974% as seen in Row 13) with regard to their GVO and productivity, respectively, compared to the non-food and non-agro-based MSME firms in 2006–2007.

Summary of Findings: Policy Inferences and Extensions

The census analysis for the performance of MSME firms between 2001–2002 and 2006–2007 shows a varied effect of trade liberalization on MSME firms depending on firm- and industry-specific factors. While the impact on output growth and productivity for the overall MSME segment is mostly negative, we find that certain sub-groups of MSME firms, namely, those which use modern power techniques in their production process, which are technologically upgraded and which maintain their product quality standards, have performed better in both output and productivity terms. We also find that input channel effects resulting from liberalization of input tariffs are consistently larger and more significant than competition effects resulting from the liberalization of final goods tariffs.

Firm-specific characteristics such as access to institutional credit and total employment play a positive and often significant role in enabling growth in firm-level output and productivity of Indian MSMEs. Industry-specific characteristics such as the export propensity of the industry to which an MSME firm belongs also emerge as important in that firms which are exposed to greater trade liberalization are also associated with a more adverse impact on output and productivity. However, in all cases, technology readiness, quality standards and modernization mitigate such adverse effects or enable MSMEs to derive benefits from tariff liberalization. Non-tariff liberalization emerges as more significant than tariff liberalization in terms of improving firm productivity and output growth, probably reflecting the much greater and uniform (across industries) import liberalization through NTB reductions compared to tariff liberalization where significant differences remain across industries in protection levels.

These findings provide several useful takeaways for policy makers. By confirming the significance of operational, structural, financial and technological constraints in shaping the performance of MSMEs and the impact of trade liberalization, our findings underscore the need to focus on the MSME segment separately to address their constraints under India’s overall trade and industrial policy framework. Recent Government of India schemes to provide a corpus fund for MSMEs or to provide upfront capital subsidies to adopt new technologies for in-house testing and quality control are important steps in this direction. More can be done in India to improve access to credit and to incentivize the adoption of technology by MSMEs. Some policy initiatives could include increasing the limits for collateral-free loans, providing funding support for the adoption of Quality Management Standards and Quality Technology Tools, creating greater awareness of IPRs and quality norms through training programmes and mentoring, introducing performance-linked incentives for financial assistance, and creating business facilitation centres with the support of industry associations, equity funds, banks and financial institutions to facilitate access to finance for MSMEs. There is also scope to integrate measures to facilitate MSMEs within recent Government of India initiatives such as by creating an ecosystem wherein foreign companies investing in India under the “Make in India’ scheme, source domestically from MSMEs, by promoting MSME capabilities in the ICT sector under the “Digital India” scheme and by providing mentoring, market information and training support under the “Startup India” scheme. Initiatives adopted in other countries to promote small business can be instructive.

Second, our analysis indicates that, while much of the focus of studies on trade liberalization is on the competition-creating effects in final product markets, the potential gains to firms due to the sourcing of a greater variety and scale of imported intermediate inputs can be important.Footnote 48 Hence, from a policy standpoint, liberalization of tariff and NTBs on imported intermediates requires attention. Such an understanding would also help address an issue often raised by some sectors of Indian industry, namely, the disincentive to value addition that arises from an anomalous reduction in final goods tariffs while intermediate tariffs remain high. This issue assumes importance in the context of preferential trade agreements where one of the main sources of gains could arise from input liberalization and an appropriate balancing of final goods versus intermediate liberalization vis-à-vis trading partners is required. Such an approach to trade liberalization under preferential agreements would also facilitate the participation of Indian MSMEs in global value chains, one of the current objectives of the Indian government.

A third important policy inference that emerges from the results is the significance of firm- and industry-specific characteristics in shaping the effects of trade liberalization, and thus the need for policies that recognize these differences across firms and industry groups when framing policy, so as to ensure a more balanced outcome for the MSME segment at large.

Two immediate extensions are possible to this study. First is the possibility of undertaking more disaggregated empirical analysis of trade barriers and their impact to examine the effects of trade liberalization on the performance of MSME firms within a broad industry group itself, for instance the subsectors of cotton, readymade garments, synthetics, etc. within the textile industry.Footnote 49 Second, the NTB index, which has been constructed at the 2-digit level in this study, could also be constructed at the 4-digit level, which may enable us to observe greater variation in NTB liberalization at a disaggregated level within an industry group. This could enable us to better understand why NTB liberalization has had a stronger and more significant impact than tariff liberalization and to assess differences across industry groups and firm-level characteristics. A second extension of this study would be to examine the role of state and regional factors. As the performance of MSMEs varies across states and regions in India, it would be useful to extend the analysis by incorporating various state-specific indicators and to assess to what extent state policies, level of development and infrastructure, factor market conditions and other parameters have influenced the impact of trade liberalization on Indian manufacturing MSMEs.

Notes

There is, however, variation across countries in defining MSMEs. Countries define MSMEs in terms of assets, turnover or employment.

Annual Report—Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, 2016–2017: http://msme.gov.in/sites/default/files/MSME%20ANNUAL%20REPORT%202016-17%20ENGLISH.pdf.

The simple and weighted average applied MFN tariffs stood at 13% and 6.9%, respectively, in 2014–2015. See Singh (2017), Table 4, p. 14 and Table 5, p. 15.

See Press Information Bureau Government of India, Ministry of Commerce & Industry,

http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=118222 for discussion on removal of the last 20 items from the MSME list.

The Export–Import or Exim Policy consists of guidelines and instructions established by the Director General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) on matters related to the import and export of goods in India. The Foreign Trade Policy of India is guided by the EXIM Policy and is regulated by the Foreign Trade Development and Regulation Act, 1992. See http://www.exim-policy.com/.

Definition of sick SSI (small-scale industry) unit: An SSI unit should be considered 'sick' if any of the borrowal accounts of the unit remains substandard for more than 6 months, i.e. principal or interest, in respect of any of its borrowal accounts has remained overdue for a period exceeding 1 year. See https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=543&Mode=0 for further details.

The process for merging the two rounds of census data is explained in “Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics” and illustrated in Appendix A.

This merged dataset has several advantages over other firm-level databases in India for analyzing the impact of trade liberalization. Other datasets like the CMIE (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt. Ltd.) Prowess and ASI (Annual Survey of Industries) database have a very low representation of MSME firms and do not contain firm-level features such as quality standards and technological knowhow. This dataset covers registered enterprises unlike the NSSO (National Sample Survey Office) database which covers unorganized firms. None of these other datasets provide wide coverage of micro-enterprises. The Census dataset also enables a more disaggregated industry-level analysis as it contains a wide range of industries.

It is important to note that no previous studies which have examined the performance of Indian MSME firms have used both the 3rd and 4th censuses to examine the impact of trade liberalization. Coad and Tamvada’s (2012) examination was based only on the 3rd Census.

“Planning of Fourth All India Census of Micro-, Small and Medium Enterprises 2006-07 coincided with a significant development in evolution of small sector, i.e. enactment of MSMED Act in 2006, which broadened the scope of sector to include all the non-agricultural enterprises including medium enterprises falling within the stipulated investment limits. Hence, the frame for the 4th Census of registered enterprises was enlarged to include enterprises registered with KVIC/KVIB, Coir Board and under Section 2 m(i) & 2 m(i) of the Factories Act apart from the enterprises permanently registered with District Industries Centers (DICs), as against the 3rd Census, which included in its frame only permanently registered enterprises with DICs. Thus, in the 4th Census, all the enterprises permanently registered up to 31 March 2007 at District Industries Centers (DICs) of the State/UT Directorate of Industries numbering 21.04 lakh were surveyed on a complete enumeration basis. In addition, 2.15 lakh enterprises registered under Section 2 m (i) & 2 m(ii) of the Factories Act were also surveyed on a complete enumeration basis so that enterprises with investments in Plant & Machinery above Rs. one crore (which was the investment limit for SSI sector prior to the MSMED Act, 2006) were culled for inclusion in the 4th Census results of the MSME sector. Further, 0.73 lakh KVIC/KVIB units and 0.09 lakh Coir units were also taken up in the census of registered MSMEs. In all a set of 24.01 lakh enterprises were surveyed on a complete enumeration basis.

Of the 24.01 lakh enterprises surveyed on a complete enumeration basis, as mentioned above, 22.48 lakh enterprises were found relevant to the MSME sector. Enterprises which exceeded the investment limit of the medium sector under the MSMED Act (i.e. Rs10 crore) were excluded from the list of enterprises registered under Section 2 m(i) and 2 m(ii) of the Factories Act in the final results of the 4th Census. Similarly, enterprises which had more than one registration (i.e. with DIC and with KVIB/Coir) were filtered out in the process of field survey. Break-up of 22.48 lakh enterprises having filed EM II/permanently registered with DIC is 20.62 lakh; registered under Section 2 m(i) and 2 m(ii) of the Factories Act 1948, 1.16 lakh; KVIC/KVIB/Coir units 0.70 lakh”; Final Report of 4th All India Census of MSME Registered Sector 2006–2007, Pages 9–10), This indicates that the study goes beyond the ASI dataset which mainly concentrates on large firms to give a main focus on MSME firms. Note that ‘lakh’ refers to 100,000 and ‘crore’ refers to 10 million.

A tehsil or tahsil/tahasil, also known as taluka (or taluq/taluk) or mandal, is an administrative division. It is an area with a city or town that serves as its administrative centre. It may contain additional towns and a number of villages.

See http://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/Administrative_division.aspx.

The National Industrial Classification-2004 (NIC-2004) plays an important role in maintaining standards of data collection, processing and presentation as well as applications in policy formulation and policy analysis. This classification is used in all types of censuses and sample surveys conducted in India. The latest and fifth Industrial Classification, NIC-2004 was developed and released by CSO in November 2004. See http://mospi.nic.in/Mospi_New/upload/nic_2004_index.htm.

See Appendix A, Tables 16 and 17 for a description of the variables in the 3rd and 4th All India Census of MSMEs and an illustration of the merger procedure.

Although, in both the censuses the authority had collected data for the preceding 2 years (e.g., 2000 and 2001 in the case of Census 2002, and 2005 and 2006 in the case of Census 2007), the information is limited to some key performance indicators, such as the GVO. Thus, our results are confined just to the years 2002 and 2007. But while estimating productivity using the Levinshon–Petrin (LP) method we have utilized the additional information for some major variables, such as the GVO, intermediate inputs, total assets and level of employment (2000–2002 and 2005–2007).

See MSME Annual Report (2015–2016), Table 1, pp. 7–8.

Appendix Table 18 shows the distribution of MSME firms across states.

Appendix Table 19 provides the distribution of MSMEs across industry groups. The Census report provides other descriptive statistics, including employment, output and asset distribution across industries. These broadly mirror the industry-wise distribution of MSMEs although certain industries such as textiles, chemicals and machinery and equipment feature importantly.

Appendix Table 20 shows the major reasons reported by sick or incipient sick units as per the final report on the 4th Census.

The unorganised sector is defined by the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganized Sector as “consisting of all unincorporated private enterprises owned by individuals or households engaged in the sale or production of goods and services operated on a proprietary or partnership basis and with less than ten total workers”; Report on Conditions of Work and Promotion of Livelihoods in the Unorganised Sector (p. 2) See http://dcmsme.gov.in/Condition_of_workers_sep_2007.pdf.

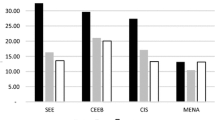

We also identify the effects of trade policy across two broad groups of MSME firms; (1) the non-food and non-agro-based industry group and (2) the food and agro-based industry group. These two industry groups are selected because of the divergent trends in tariff liberalization they have experienced during our study period. The 2004–2009 EXIM Policy which was introduced in 2004, widened the gap in tariff rates between these two groups of industries. The final goods tariff rate for the food and agro-based industry group declined only marginally from 39.89% in 2001–2002 to 35.58% in 2006–2007, while the final goods tariff for the non-food and non-agro-based industry group declined to as low as 6.57% in 2006–2007. Appendix Figures 2, 3, anc 4 provide the differential trends in tariff rates for these two industry groups. See Mukherjee and Chanda (2017) for further discussion of these differential trends. Given this divergent trend in tariff liberalization, we have conducted a robustness check in “Robustness Checks”, where we employ a difference-in-difference model to estimate the differential effect of EXIM Policy, 2004–2009 on firm-level performance of Indian MSME manufacturing across these two industry groups.

See the gross revenue approach to productivity estimation discussed in Levinsohn and Petrin (2003).

It is important to note that the LP method of productivity estimation requires last year’s input data to proxy the unobservable productivity term, as it follows Markov’s chain rule while choosing quantity of inputs in the present period. Hence, we have utilized the additional information of input variables, such as intermediate inputs, total assets and level of employment for the year 2000–2001 as a proxy for the productivity term of 2001–2002 in the 2nd stage of the LP method and similarly we have taken proxy using the data of 2001–2002 for the productivity term of 2006–2007. Thus, in LP productivity estimation results, we have utilized 3 years data of major variables. However, as pointed out earlier, this information is limited to some key performance indicators, such as GVO. Thus, our analysis is confined to the years 2002 and 2007.

It is important to note that, unlike the usual LP results of other papers, Table 5 highlights a very low co-efficient value of total input expenditure (though significant), as this segment consists of all MSME firms, which operate at a very small scale and are unable to use quality inputs to improve their productivity. Moreover, Table 5 indicates that labour and initial fixed assets are the main factors for their productivity improvement.

The productivity index is calculated as the logarithmic deviation of a firm from a reference firm's productivity in the particular industry in the base year. For the productivity index calculation, we have subtracted the productivity of a firm (mean log output and mean log input level) in 2001–2002 (base year) from the estimated firm-level TFP to get the productivity index.

However, the main results also remained robust after the inclusion of the outliers.

International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities, Revision. 3

http://unstats.un.org/unsd/cr/registry/regcst.asp?Cl=2 and National Industrial Classification,

The STAN database provides a comprehensive tool for analysing industrial performance at a relatively detailed level of activity across countries. It includes annual measures of output, labour input, investment and international trade which enable the construction of indicators pertaining to productivity growth, competitiveness and general structural change.

http://www.oecd.org/industry/ind/stanstructuralanalysisdatabase.htm.

“The World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) database provides access to international merchandise trade, tariff and non-tariff measures (NTM) data. See http://wits.worldbank.org/. The ASI is the main source of industrial statistics in India. It enables analysis of the growth, composition and structure of organised manufacturing sector across a wide range of activities.

http://mospi.nic.in/mospi_new/upload/asi/ASI_main.htm?status=1&menu_id=88.

We have followed the standard definition of export propensity provided by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) to calculate the same at the industry-level over time. See http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditctab2017d6_en.pdf.

While estimating the TFP index we have taken care of the effects of firm size and total employment. Hence, we have not taken these as control variables in the fixed effect model specification.

A higher NTB index value represents a more liberalized regime. This is because, in contrast to earlier studies which construct NTB indices by giving a value of 0 for freely imported products and 1 for products prohibited from imports, we invert the scale by assigning a value of 0 for prohibited products and 1 for the freely imported products. Hence, a higher value of this index represents a more liberalized NTB regime (See Appendix Tables 24, 25, 26 and 27 for details).

See Appendix Table 23 for the results showing the absence of trade policy endogeneity with firm-level performance measures. It should be noted that Topalova and Khandelwal (2011) find trade policy endogeneity between 1997 and 2001, though not for the 1989–1996 period, indicating that there is no systematic trade policy endogeneity with the latter varying over different time periods. The absence of endogeneity between GVO and productivity on the one hand and trade policy on the other between 2002 and 2007 can be explained by the fact that there was a steady move towards trade liberalization in India with the introduction of the EXIM policy in this period, as well as the removal of NTBs that India had to undertake as part of its WTO obligations. We still ensure the robustness of our results in the presence of endogeneity by employing a DID model (see Robustness Checks).

Before examining the relationship between import tariff liberalization and firm performance for the various sub-groups of Indian MSMEs (i.e., Panels 1–4 of Tables 7, 8, 9 and 10) we undertook a post-estimation test of equality between the coefficient means of 'tariff variables' for sub-groups (i.e., all vs. modern power sourced, all vs. high quality, all vs. high tech, all vs. sick and finally with their counterparts). The results show a significant mean difference among the coefficients for each sub-group. For instance, the test for the mean coefficient differences between all MSMEs (i.e., Panel 0) and technologically advanced MSMEs (i.e., Panel 4, Column 1) gives a calculated Chi square (1) value of 10.05 (and the P value is 0.0015), which indicates that the impact of tariff liberalization on firm performance differs significantly for all MSMEs versus technologically advanced MSME firms..

We also include a size-square variable in our model to control for a possible non-linear relationship between firm-size and GVO. Our results remain consistent with the earlier ones. See Appendix D.

It would have been useful to examine the effects of input tariff liberalization on the import behavior of MSME segments (sub-groups) for the study period to identify the significance of the input channel for different groups of firms. However, such analysis could not be undertaken as the census data did not provide information on firm-level imports.

See http://dcmsme.gov.in/publications/MSMEIniciativeEnglish.pdf for further details on initiatives aimed at supporting MSME firms.

A higher NTB index value represents a more liberalized regime, as explained earlier.

The NTB index values exceeds 90 (i.e., mostly free from any import restrictions) for almost 99% of our sample observations. It is important to note that the variation in growth of firm-level GVO across various kinds of Indian manufacturing MSME firms could be better explained by calculating the NTB index at a more disaggregated level (i.e., for 4-digit industry groups). However, our construction of this index, as outlined in Appendix C, is at the 2-digit level as the purpose is to understand the broad overall trend in NTBs over our study period and to compare the results against those obtained for tariff liberalization. Disaggregated analysis of the trends in NTBs is left for future research.

While the average tariff rate in low protection industries fell from nearly 30% to a little over 11% between 2002 and 2007, in high protection industries, the average tariff rate declined only marginally from 36% to 32% (as highlighted in “Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics”).

See Chapter 13 (pp. 455–468) in Wooldridge (2013) Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 5th Edition for more details about the DID approach in Two-Period Panel Data Analysis framework.

For instance, MSME which belong to low-productivity industry groups may receive much higher protection in terms of higher tariff rates compared to high-productivity firms. This might lead to an omitted variable bias in the analysis.

The results for the preliminary DID model with treatment dummy (estimated using OLS) are presented in Appendix E.

It should be noted that, in the productivity equation (Eq. 7), we do not control for total fixed assets and employment as these variables have already been used in the productivity estimation.

Mukherjee and Chanda (2016) has confirmed the greater impact of NTB relative to tariff liberalization on firm-level performance for different sub-groups of the textile industry over the 1999-2009 period.

The discussion of the methodology for tariff measurement is based on Mukherjee and Chanda (2017).

Data extracted on 24 Mar 2014 10:18 UTC (GMT) from OECD. Stat, http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=STAN_IO_TOT_DOM_IMP.

The discussion of the methodology for NTB measurement is based on Mukherjee and Chanda (2017).

The usual NTB index would give 0’s for import free products, hence the reverse formulation.

This is due to the fact that, in other previously constructed NTB measures, both prohibited and restricted imported items were considered to be fully protected and was assumed to have no imports happening over the years.

The size-square variable is included to control for a possible non-linear relationship between firm-size and GVO.

References

Ahsan, R.N. 2013. Input tariffs, speed of contract enforcement, and the productivity of firms in India. Journal of International Economics 90: 181–192.

Alfaro, L., and Eliza Hammel. 2007. Capital flows and capital goods. Journal of International Economics 72 (1): 128–150.

Aw, B.Y., Xiaomin Chen, and Mark J. Roberts. 2001. Firm-level evidence on productivity differentials and turnover in Taiwanese manufacturing. Journal of Development Economics 66 (1): 51–86.

Balakrishnan, P., M. Parameswaran, K. Pushpangadan, and M. Suresh Babu. 2006. Liberalization, market power, and productivity growth in Indian industry. The Journal of Policy Reform 9 (1): 55–73.

Bas, M. and A. Berthou. 2011. “The Decision to import capital goods in India: Firms’ financial factors matter.” Centre d’études prospective et d’informations internationals (CEPII), Working Paper No 2011–06.

Bernard, A., J. Eaton, J.B. Jensen, and S. Kortum. 2003. Plants and productivity in international trade. American Economic Review 93 (4): 1268–1290.

Coad, A., and J.P. Tamvada. 2012. Firm growth and barriers to growth among small firms in India. Small Business Economics 39 (2): 383–400.

Corden, W.M. 1966. The structure of a tariff system and the effective protective rate. Journal of Political Economy 74 (3): 221–237.

Costantini, J., and M. Melitz. 2008. The dynamics of firm-level adjustment to trade liberalization. In The organization of firms in a global economy, ed. E. Helpman, D. Marin, and T. Verdier, 107–141. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Das, D. K. 2003. Quantifying trade barriers: has protection declined substantially in Indian manufacturing. Economic and Political Weekly, January 31st Issue.