Abstract

Besides being extensively studied by health sociologists, medicalisation has also become a term that frequently appears in mainstream discourses on health and illness. Recently, scholars started to acknowledge a greater complexity within medicalisation. This article is situated within this research tradition and draws on three recurring critiques on the validity of medicalisation; critique on the construct validity, internal validity and external validity. By examining the interests and network of health-policy stakeholders, this article attempts to unravel different mechanisms of medicalisation and demedicalisation within a social health insurance system. The empirical data for this article derive from 30 elite interviews with key informants from 18 organisations in Belgium. Key representatives of these organisations provided us with in-depth information about their political intentions and interests. This study provides empirical evidence that both medicalisation and demedicalisation are different processes that can occur simultaneously. Furthermore, in order to facilitate studies on medicalisation in an institutional context, this article proposes some indicators for medicalisation and demedicalisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past decades, numerous studies on medicalisation have been published. Early attempts of conceptualising medicalisation emphasised the expansion of medical jurisdiction and the definitional aspect. ‘By medicalisation we mean defining behaviour as a medical problem or illness and mandating or licensing the medical profession to provide some sort of treatment for it’ (Conrad, 1975, p. 12). These studies assume that there will be a ‘pathologicalisation of everything’ (Conrad, 2013, p. 207; Zola, 1972). More recent studies have taught us that ‘rather than a fixed, universal process, medicalisation is fluid, relational, and shifts depending on the context’ (Bell, 2016, p. 44).

Drawing on the results of a large qualitative study in Belgium, this paper adds to this literature by presenting further insights into the medicalisation process. This article calls on three recurring critiques on the validity of medicalisation and uses the Belgian social health insurance system as a case study, which is characterised by the inclusion of nongovernmental actors within the decision-making process. In this corporatist model, these various actors collaborate but also compete with each other. Decisions on what belongs to the medical sphere – and what does not belong – are, thus, constantly (re)negotiated. Hence, in this context, medicalisation is a fluid process instead of a fixed process. Starting from this fluid nature of medicalisation, we explore how processes of medicalisation and demedicalisation are constituted in this institutional context.

A Brief History of Medicalisation

Medicalisation is often defined as ‘the process by which previously nonmedical problems become defined and treated as medical problems, usually as diseases or disorders’ (Conrad, 1992, p. 211). In early formulations of medicalisation, the concept was linked to medical dominance and the extension of medicine’s jurisdiction (Ballard and Elston, 2005), and was rooted in criticism on the medical takeover of everyday life (Illich, 1976; Zola, 1972). From the 1980s onwards, changes in the organisation of medicine and medical knowledge caused a shift in the drivers of medicalisation (Conrad, 2005). Ballard and Elston (2005, p. 234) argue that ‘medical sociologists have increasingly turned to the examination of the particular contexts and protagonist characteristics that are conducive (or not) to medicalisation, and of the different forms that medicalisation might take, rather than assuming it to be the inexorable outcome of medical dominance’.

Consequently, scholars view medicalisation as ‘a more complex, ambiguous, and contested process’ (Ballard and Elston, 2005, p. 230), and focus now on variations within medicalisation (Bell, 2016; Halfmann, 2012). Other publications have emphasised the importance of demedicalisation (Lowenberg and Davis, 1994; Halfmann, 2012), which is often defined as the obverse of medicalisation (Halfmann, 2012, p. 2). Lowenberg and Davis (1994, p. 594) argue that ‘there is no unilateral movement in the direction of either medicalisation or demedicalisation’. They emphasise that both processes can occur simultaneously and, consequently, encourage researchers to focus on resistance and constraints to medicalisation (Lowenberg and Davis, 1994; Halfmann, 2012).

Furthermore, different researchers have criticised the validity of medicalisation as a concept (Busfield, 2017). First, the very nature of medicalisation has been questioned. Davis (2006) has criticised the severing of the connection between medicalisation and medicine. He argues that the decoupling of medicalisation from the institution of medicine has created a situation in which “we have no way to determine what constitutes a ‘medical’ term or framework” (Davis, 2006, p. 53). Others have claimed that the medicalisation thesis is no longer sufficient to explain new trends in medicine and medical sociology (Abraham, 2010; Clarke and Shim, 2011; Williams et al, 2011). Clarke and Shim (2011, p. 173), therefore, conceptualised biomedicalisation as ‘the transformation of medical phenomena by technoscientific means’. Another related concept is pharmaceuticalisation, which Abraham (2010) as well as Williams and colleagues (2011) have conceptualised. Pharmaceuticalisation can be defined as ‘the transformation of human conditions, capabilities and capacities into opportunities for pharmaceutical intervention’ (Williams et al, 2011, p. 711). Second, scholars have criticised the strong focus on the definitional aspect. More recently, the attention for practices and actors as mechanisms of medicalisation has increased (Clarke and Shim, 2011; Halfmann, 2012). Halfmann (2012), for example, developed a typology in which he distinguishes between three levels and dimensions of medicalisation and demedicalisation. According to him, medicalisation increases when biomedical vocabularies, practices or actors become more prevalent in addressing social problems (Halfmann, 2012, p. 6). Third, the external validity of medicalisation has been criticised. Most theories of medicalisation use the United States (USA) as a single case study (Conrad and Bergey, 2014; Olafsdottir, 2010). This has led to an incomplete understanding of the medicalisation process as, according to Olafsdottir (2010, p. 241), ‘the US has a unique relationship between the market, the state and medicine’. Being the only advanced, industrialised society where healthcare is not universal to all citizens, medicine in the USA has become a commodity. Other practices, such as direct-to-consumer advertising, private ownership and funding of health insurance, further contribute to the commodification of healthcare (Busfield, 2010; Moran, 2000). In fact, Olafsdottir (2010, p. 251) argues that ‘medicalisation processes are embedded within institutional arrangements that shape how medicalisation happens and what mechanism are the main forces of medicalisation’. Consequently, medicalisation varies across institutional settings (Buffel et al, 2017; Conrad and Bergey, 2014; Olafsdottir, 2010).

This paper addresses these critiques and contributes to the literature that focuses on the complexity of medicalisation. First, by focusing on the healthcare system, we bring the institution of medicine back into medicalisation. Second, by focusing on the interests and interplay between health-policy stakeholders, we go beyond a definitional approach towards medicalisation. That is to say, we perceive medicalisation as a multidimensional concept and analytic tool that allows us to investigate the expansion of medicine beyond its boundaries (Busfield, 2017). For the purpose of this study, we will focus mainly on two dimensions of medicalisation: practices and actors (Halfmann, 2012). Third, by using Belgium as a case study, we add to the literature that analyses medicalisation in different institutional settings. More specifically, we will focus on the institutional context of a social health insurance system.

Social Health Insurance Systems

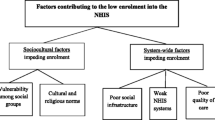

Within Western Europe we can distinguish two types of healthcare systems: national health insurance systems (NHI) and social health insurance systems (SHI) (Thomson et al, 2009; van der Zee and Kroneman, 2007). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) adds a third type to this classification: the private health insurance model (PHI) (Schieber, 1987; Colombo and Tapay, 2004), which only exists in the USA (Giaimo and Manow, 1999; Olafsdottir, 2010; Colombo and Tapay, 2004). Figure 1 illustrates the differences in financing, ownership and provision of health services between these systems (Hassenteufel and Palier, 2007; Wendt et al, 2009). Although, it is often difficult to classify countries because of the internal variation within each healthcare model (Moran, 2000; Wendt et al, 2009) most countries can be situated in at least one of these systems (Hassenteufel and Palier, 2007; Wendt, 2014).

Figure 1 indicates that SHI systems are funded by social insurance contributions and managed by nongovernmental actors (e.g. sickness funds, physicians) (Wendt et al, 2009). In order to understand the SHI type of system, and the complexity it implies, it is necessary to revisit its seven core components (Saltman et al, 2004: p. 6). A first core component is a scheme of risk-independent, transparent contributions, tied to the affiliated users’ income and collected separately from other state revenues. Secondly, health insurance is organised through non-profit private ‘sickness fund’ agencies, which collect health insurance contributions or receive them from a state-run fund. Third, citizens are free to choose their healthcare providers as well as the sickness fund agencies they affiliate to. Fourth, the SHI operates upon a principle of solidarity in what concerns the coverage, funding and benefit packages.

The three remaining traits of the system are important for our analysis. A fifth trait is the inclusion of different actors that are all considered as constituent parts of the organisational structure. Sixth, SHI systems consist of a corporatist model of negotiations. The seventh, and last, core component also relates to the inclusion of different actors within the SHI system. As Saltman and colleagues (2004, p. 8) explain

SHI systems typically incorporate participation in governance decisions by a wide range of different actors. The most visible manifestation is the traditional process of self-regulation by which sickness funds and providers negotiate directly with each other over payment schedules, quality of care, patient volumes and other contract matters.

At this point, it becomes clear that the SHI system is unique in that both private and public interests are combined in the public policy-making process through a network of stakeholders (Hassenteufel and Palier, 2007), which is key in the focus of this article. In order to fully grasp these various interests and potential conflicts between stakeholders, a qualitative approach is necessary. Considering that these intentions and interests are often hidden to the naked eyes of researchers and other actors within the system, this process is difficult to fully comprehend by merely observing behaviours. Therefore, this study uses elite interviews. The term ‘elite interviewing’ is used to describe interviews with ‘those who occupy senior management and board level positions within organisations’ (Harvey, 2011, p. 5).

Methods

Selection of stakeholders

This study is part of a larger research project that deals with health-policy stakeholders in Belgium. For purposes of this study, a stakeholder is defined as an organisation that has an interest in the SHI system or could have an active influence on the decision-making and implementation processes (Bryson, 2003). This definition is related to what Ramírez (2001) calls ‘social actors’. Someone can be a stakeholder, but he/she also has to have the knowledge and capacity to act as a social actor. For example, individual patients are stakeholders because they have an interest in healthcare decisions. Yet, they are not included in our sample of stakeholders because they as individuals do not have the capacity to act as social actors. Conversely, patient organisations are seen as stakeholders because they have both the knowledge and capacity to actively participate within the SHI system. Moreover, other stakeholders will perceive them as social actors.

In order to construct a meaningful sample, we organised the stakeholders in six categories (see Table 1) that are based on the types of organisations as described in the literature (Britten, 2008; Busfield, 2010) and the types of organisations included in the organisational structure of the Belgian SHI system. Subsequently, to overcome the risk of accidentally omitting important parties, these categories were scrutinised by two experts, who were familiar with the system. The final sampling model included 19 stakeholders operating across the Belgian SHI system.

Selection of key figures

Once the stakeholders were defined, elite interviews were conducted with key informants within each organisation. The first key figures we selected were high-rank management representatives (e.g. Chief Executive Officer and managers), as their position provides them with a general overview of the respective organisation and its goals. Since this study was concerned with health politics and communication, the communication officers were also recruited as interviewees. Interviewing two key figures per organisation allowed for distinguishing between the official organisational rhetoric and personal views, and it offered a quality check (Berry, 2002). It enabled comparing the information provided by one person or organisation with the information by another person or organisation (Patton, 1999).

Table 1 gives an overview of the number of organisations and interviews, which were undertaken between March and October 2015. Although the sampling model considered 19 organisations, one stakeholder declined to take part in the research. Note that, in case of small size organisations, only someone at the management level was interviewed. Finally, in four cases a double interview took place because the key informant either asked to involve a second informant or insisted that the director and the communication officer were interviewed at the same moment.

Data gathering and analysis

A semi-structured guide with open-ended questions was used to gather in-depth information about the interests and relations between these stakeholders. Each respondent was given an explanation about the research project’s scope and privacy procedure and then signed a confidentiality agreement allowing us to record the interviews. Several strategies were used to ensure the quality of the data and results, such as full recording and transcription of the interviews (Aberbach and Rockman, 2002), and CAQDAS techniques to ease data management. Organisational documentation, press releases and policy documents were gathered as well. The analysis itself consisted of different stages of coding and constant comparison (Mills et al, 2006; Strauss and Corbin, 1990).

Findings

Our results indicate that the various interests of these stakeholders and the complex interplay between them lead towards both medicalisation and demedicalisation processes. To better understand this complex interplay between stakeholders and their interests, the following subsections provide an in-depth analysis of each stakeholder.

Sickness funds

The following quote of one of the representatives of the sickness funds summarises the main interests of sickness funds:

We’re a social insurance company. We’re a social movement and we’re a social entrepreneur, and everything we do is related to one of those 3 domains (Sickness Fund 1).

First, sickness funds are social insurance companies. The Belgian SHI system was conceived when in 1894 the law on mutual benefit funds was enacted (Corens, 2007; Schepers, 1993). Starting from 1900, these sickness funds were grouped at the national level in six Health Insurance Associations (HIAs), which are private, non-profit organisations entrusted with a central role in the SHI system (Nonneman and van Doorslaer, 1994). These HIAs gradually became more important and were in a constant struggle with the medical profession (Schepers, 1993). The Health Insurance Act of 1963 extended the coverage of the compulsory health insurance and introduced a system of conventions and agreements (Callens and Peers, 2015; Corens, 2007). Furthermore, the compulsory health insurance market is closed to new entrants, granting HIAs a monopoly position within the system (Nonneman and van Doorslaer, 1994).

Before 1994, sickness funds were not held financially responsible for their expenses, meaning that for them cost containment was less important. Starting from 1994, a system of financial responsibility was introduced (Callens and Peers, 2015). Sickness funds became more focused on keeping the healthcare budget within certain limits. This has become a part of their identity, and their discourses reflect this identity:

We don’t have campaigns that encourage the use of medicines. On the contrary, I can give you two, even three, examples of campaigns against the overconsumption of medicines (Sickness Fund 1).

This quote reflects one of the main themes within their discourse, namely the overconsumption of medicines and other treatments. Other recurring themes were self-care and the use of generic medicines. Moreover, the law on financial responsibility uses the efforts made with regard to health education, promotion and the use of less expensive treatments as one of the benchmarks to evaluate the financial management of sickness funds (Callens and Peers, 2015). Our interviewees provided us with various insights into these efforts. For example, one sickness fund developed an online tool that helps losing weight and gives dietary advice. Furthermore, in our interviews and in a recent position paper (Brenez, 2015), the battle against overconsumption and fraud was described as an important challenge for the future:

For example, physicians and hospitals who charge the same treatment twice. Physicians who perform a treatment that they aren’t allowed to perform. Unnecessary testing of urine or blood by hospitals (Sickness Fund 1).

As a consequence, their identity, discourse and practices are focused on lifestyle solutions for (medical) problems instead of biomedical practices, and encourage demedicalisation of certain problems (Halfmann, 2012).

Second, sickness funds are social movements. Historically, sickness funds were associated with the labour movement, and they developed along political and religious lines (Nonneman and van Doorslaer, 1994). One representative explains:

They developed on the stairs of churches or in ‘volkshuizen’ [social meeting places for working people] (Sickness Fund 1).

This historical background still influences their goals and priorities. For example, the Independent sickness fund is the result of a merger between small mutual benefit funds for professionals. Nowadays, this focus on professionals is still reflected in their magazine for health professionals. Moreover, these different ideological backgrounds lead to differences in the benefits packages offered by the sickness funds. For example, recently the Socialist sickness fund announced that they would reimburse the non-refundable part of medical expenses, so that GP consultations would become free of charge (Solidaris, 2016). According to the Socialist sickness fund, this reimbursement leads towards increased access to care and more solidarity within the healthcare system. Other sickness funds disagree with this practice, as it encourages medical treatment. According to them, the non-refundable part is necessary to raise awareness of its costs.

These differences in benefits packages are also related to the third function of sickness funds; their social entrepreneur function. Besides having a monopoly position within the compulsory system, sickness funds also offer additional insurance and benefits, such as sauna sessions. These additional benefits are driven by a competition between HIAs for new members (Nonneman and van Doorslaer, 1994), a logic that is amplified by the competition within the private, supplementary, health insurance market, in which sickness funds also participate. This competition is driven by two goals: more members means more revenue, and competition for ideological dominance and political power (Nonneman and van Doorslaer, 1994). The representatives in our sample often referred to each other as “con-collega’s”, meaning that they are colleagues but also competitors. They are colleagues in the sense that they often work together and negotiate as one group. Nevertheless, they are also competitors, and this competition often results in medicalising practices. One of the representatives gave the example of alternative medicine, which is not reimbursed within the compulsory system (Corens, 2007). Notwithstanding their important role within the compulsory system, most sickness funds offer some reimbursement for alternative medicine. The representative explained that, ‘although they – as a sickness fund – know that alternative treatments do not work, lay people use these alternative treatments’. Consequently, they reimburse some treatments. More specifically, the ones that are prescribed by physicians, in order to protect patients from ‘charlatans’ and potentially harmful treatments. Undoubtedly, this is the official discourse. Most of these treatments are reimbursed in order to attract new members, and to compete with each other.

Patient organisations

From our historical overview of the development of sickness funds, it becomes clear that they originally were conceived as the defenders of patients (Schepers, 1993). In 1999 and 2000, two umbrella organisations each representing around 100 patient organisations were founded (Belgian Official Journal, 1999, 2000). These umbrella organisations gradually became more prevalent within the SHI system, and there is a tendency towards including them in different consultation bodies. In March 2015, the Belgian Minister of Public Health announced that these organisations would be included in the Board of Directors of the Belgian Healthcare Knowledge Centre (KCE). Moreover, she announced that patients needed a voice within the health-policy making process, because they were ‘an essential actor’ within the organisation of healthcare (De Block, 2015). This announcement suggests that the Minister questions the role of sickness funds as defenders of the patient. In fact, some of our interviewees also questioned their role, and indicated that they preferred working together with patient organisations because they are independent from any political background. The following interview excerpt of one of the sickness funds summarises the main differences between these organisations:

That’s something that isn’t yet clear. What is the role of the patient organisation and what is the role of the sickness funds? As I mentioned, patient organisations will focus on the interests of the sick. We [sickness fund agencies] have to defend all our affiliated members and look to the future, to the challenges that lie ahead. What are the needs? Which budgets do we need? And how are we going to organise those budgets? (Sickness Fund 2).

Patient organisations focus on ‘the sick’, while sickness fund agencies have to defend all their members, irrespective of their health status. These patient organisations are what Halfmann (2012) calls biomedical actors – advocating for a specific disease is key to their identity. Furthermore, our interviews and a recent study indicate that most patient organisations are continuously struggling to find sufficient (financial) resources (Denis and Mergaert, 2009). As a consequence, patient organisations often depend on financing by the government or the pharmaceutical industry, and they are constantly balancing between maintaining their independence and surviving. This financial dependence further strengthens their focus on biomedicine and their identity as biomedical actors (Denis and Mergaert, 2009). Consequently, one could argue that, because of their specific background, the rise of patient organisations as more prevalent and powerful biomedical actors increases medicalisation within the Belgian system.

However, as they are fairly new, these umbrella organisations are not yet anchored in the system. They are still, as the previous interview excerpt showed, struggling with their identity. As they represent various patient organisations, they have to find a balance between the different goals and interests of all their member organisations. The following interview excerpt of one of their members illustrates this difficult balance between the interests of individual patient organisations, who focus on one disease, and the development of a general framework that suits all these individual organisations:

Our focus is on [name of disease]. It’s good to think about a general framework, that there’s an organisation that represents everyone. But in the end, we will always focus on [name of disease]. That’s our focus. And as an umbrella organisation, you have to find a good balance (Patient organisation 4).

This has resulted in a strong focus of these umbrella organisations on patient rights, empowerment, and the organisation of the healthcare system in general, instead of advocacy for certain diseases or therapies. When asked what these organisations do, one of their member organisations answered:

Making sure that patients are represented within the healthcare policy-process. They also focus on a number of social issues, such as patient rights and insurances. When it comes to a specific disease, they always refer to the individual patient organisations. They have a very strict code about that. (Patient organisation 4).

We can argue that by mainly focusing on the position of patients within the SHI system these umbrella organisations demedicalise because they try to decrease the power of the medical profession and increase the power of patients. This corresponds with the fact that, notwithstanding their differences, the representatives of the sickness funds and patient organisations in our sample also refer to each other as allies. They explain that they often work together, and try to be a united cartel against the industry and associations of healthcare professionals. This suggests that these organisations identify themselves as counterforces against medicine. For example, a coalition of sickness funds and patient organisations recently launched a petition against the pricing policy of pharmaceutical companies (Test-Aankoop, 2016a). Undoubtedly, in this context, these actors challenge the power of biomedical actors, therefore encouraging demedicalisation.

Pharmaceutical Industry

Another important actor within the Belgian SHI system is the pharmaceutical industry, who are at the institutional level represented by an umbrella organisation. In the previous subsections, we have unravelled different conflicting interests and practices both within and between organisations that lead to both processes of medicalisation and demedicalisation. Our interviews reveal a slightly different pattern for the pharmaceutical industry. They do not experience the same internal challenges as our previous stakeholders, but do get challenged by other stakeholders.

Our interviewees often referred to the same issues. For example, on an institutional level, their main concern is for patients to get access to their products by getting them approved and reimbursed, which is clearly reflected in their discourse and practices.

Our main goals as [name of the company] are… of course… making sure that patients get access to our medicines. We develop new medicines that have to be registered and then it’s our goal to make sure that they’re available for patients (Pharmaceutical industry 3).

Market approval and reimbursement are important tools for getting new– often very expensive – innovative medicines to patients. When talking about market access, our interviewees often referred to Belgium as an important ‘Pharma country’. The pharmaceutical industry are indeed an significant economic player. In 2015, they invested 2.6 M€ in research and development (R&D) on pharmaceuticals, making Belgium one of the leading R&D countries in Europe (OECD, 2015). Furthermore, they are the third largest exporter of pharmaceuticals in Europe (EFPIA, 2016), and with an added value of €181,500 per employee they are the second most important industry in Belgium (Pharma.be, 2015). Since they only have an advisory function within the different consultation bodies, this economic position is often used to influence policy-decisions. The Itinera Institute even described them as one of the most powerful players within the SHI system (Daue and Crainich, 2008). Undoubtedly, this is a result of their significant economic position, which has also resulted in a pact with the Ministry (Minister of Public Health, 2015). Increased access to new innovations and the reimbursement of tests using biomarkers were important results of this pact (Minister of Public Health, 2015). Both decisions increase the use of biomedical technologies in the administration of health and illness. As a consequence, this focus on new biomedical treatments and their economic position make them a prevalent and powerful biomedical actor within the Belgian SHI system, therefore increasing medicalisation.

Notwithstanding this position, the pharmaceutical industry are just one of the many actors within the Belgian corporatist-model and they – due to their advisory function – have to look for other ways to influence policy-decisions. Our interviewees often referred to the need to collaborate with other stakeholders. One of the representatives described this logic as follows:

There are different projects in which we work together with them [the pharmacists]. We believe in collaboration. Nowadays, there are less organisations who follow an individual path. For us, dialogue and collaboration are two important goals. I believe it’s the only way to develop good initiatives (Pharmaceutical industry 2).

The representatives referred to regular meetings with the association of pharmacists and collaborations together with sickness funds. The following quote from an association of healthcare professionals explains the goal of these meetings:

We frequently talk to [umbrella organisation of the pharmaceutical industry]. We also have regular meetings with other industries in order to exchanges views on the evolution of medicines (Association of health professionals 1).

Furthermore, medical representatives still play an important role within the medical education of physicians as well. And recently, a website revealing the financial transfers between the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare professionals was founded. In 2015, 138.5 M€ were spent on research, conference and lecture fees. Of this sum, 7.5 M€ were used to reimburse healthcare professionals for their services (Eckert and Cools, 2016). Consequently, serious investments are made to maintain relationships with other stakeholders.

However, this multi-stakeholder model also means that other stakeholders can act as counterforces against the industry. For example, in 1998, an independent organisation of medical representatives was founded (Farmaka, 2016). Other stakeholders publicly challenge the pharmaceutical industry. For example, in March 2016, a patient organisation published a report in which 7250 medicines where evaluated. This report questioned the use and safety of 13 per cent of the evaluated medicines (Test-Aankoop, 2016b). As a consequence, these actors challenge the power of the pharmaceutical industry and discourage the use of pharmaceuticals, therefore encouraging demedicalisation.

Associations of healthcare professionals

In Belgium, physicians are grouped in medical associations (Schepers and Casparie, 1997). The first medical associations date back as early as 1840 (Schepers, 1993). Since 1998, elections are held to decide on the number of representatives of each union in the Medicomut (the negotiations between physicians and sickness funds). These unions represent different groups of physicians and models of medical practice (Schepers and Casparie, 1997), which has consequences for their identity, practices and discourses. First, these unions have to decide on their own identity. Do they represent only medical specialists or general practitioners or both? Do they represent Dutch-speaking or French-speaking Belgian physicians? Do they defend liberal medicine (autonomy and dominance for physicians) or are they more moderate? Clearly, there are large differences between these unions. For example, one of the oldest unions represents mostly medical specialists, both French-speaking and Dutch-speaking, and is rather conservative in its approach. Its representative frequently repeated: ‘we are a union for physicians’, which means that all their activities are focused on keeping or extending the freedom – and dominance – of physicians and of the medical profession. They stress the importance of the physician–patient relation:

The individual, the patient has to be looked after and the GP or the physician is his lawyer (Association of healthcare professionals, 2).

The union that represents mostly Flemish general practitioners has a more progressive, moderate, approach. They believe that:

Uhm we want to promote the GP but in a broader context. So, the GP as one of the many caregivers of a patient. We want to promote every aspect of their profession. We specifically chose to not use the word defending, because we want to support the future, and a new view on care (Association of healthcare professionals, 3).

These differences also lead to different practices. For example, the first union, due to its emphasis on physician’s autonomy, strongly advocated against the introduction of a third-party payment scheme, as it would allegedly threaten that autonomy (BVAS, 2015). Consequently, they have a strong biomedical identity and encourage medicalisation. The second union, on the other hand, did not oppose the idea of a third-party payment scheme, but opposed the way the scheme would be implemented. Therefore, they came with an alternative implementation plan (AADM, 2015). This shows that they are less focused on medical dominance, have a weaker biomedical identity, and can contribute to demedicalisation.

Furthermore, as elections are held to decide on the number of representatives in the Medicomut, these organisations also compete with each other. The following interview excerpt indicates the importance of being elected:

If we aren’t elected, we consult other stakeholders then the physicians to obtain information. We believe in an holistic approach. We don’t want to be conservative. The [name of other union] is also more progressive, but the [name of union] is very conservative. They will withhold information. That’s the way it works (Association of healthcare professionals, 3).

Consequently, the union that obtains the majority of the votes can heavily influence the direction of the health-policy process. In 2014, the more conservative union obtained 55 per cent of the votes, whereas the progressive – and first time participant – union obtained 21 per cent of the votes (RIZIV, 2014). In 1998, however, the conservative union obtained 67 per cent of the votes (RIZIV, 2014). Hence, the new progressive union may become a counterforce against the dominance of the conservative union, and could decrease medicalisation.

Finally, as explained earlier, both sickness funds and associations of healthcare professionals are anchored in the SHI system, and decisions are made through a system of conventions and agreements. Even though both groups often compete with each other, they are also allies in lobbying for a larger budget. A larger budget involves more means for sickness funds, because the total healthcare budget is divided between the different sickness funds, and it means a better fee schedule for providers (Callens and Peers, 2015). Consequently, this identity as supporters of a larger budget increases medicalisation.

However, every two years sickness funds and associations of physicians have to agree on the fee schedule (Callens and Peers, 2015). During these negotiations sickness funds and associations of physicians are opponents. The following interview excerpt illustrates this duality:

The associations of healthcare professionals are partners, who are also – just like sickness funds – anchored in the system. They defend their members. This means that you have the physicians who advocate for quality of care and fair, sometimes undue, fees. Sickness funds also defend quality of care, but want reasonable fees. They negotiate with healthcare professionals to obtain higher quality and reasonable fees. Sickness funds have to keep the healthcare budget in mind (Sickness Fund Agency 1).

Hence, in this case, associations of healthcare professionals medicalise because they, by raising the fees and extending the number of treatments, want to extend the autonomy and dominance of physicians. However, due to the multi-stakeholder model, their power is limited. They have to come to an agreement with sickness funds, who will resist higher fees and – as described in the first subsection – encourage demedicalisation. These tensions between physicians and sickness funds create stability within the SHI system, but also impede drastic healthcare reforms (Cantillon, 2008).

The Government and Minister of Public Health

The Belgian SHI system is a part of the broader Belgian welfare state. Belgium is classified as a conservative or Bismarckian welfare regime, where the role of the market is marginalised and benefits depend on employment status (Esping-Andersen, 1990. Eikemo and Bambra, 2008). This welfare regime is characterised by ‘neocorporatism’ (Cantillon, 2008). Decisions are made by negotiations between different stakeholders but the government does not play a passive role. The government organises these negotiations, facilitates and regulates this corporatist process, limiting the autonomy of these stakeholders (Cantillon, 2008). The following interview excerpt illustrates the role of the state:

The minister is, as you know, responsible for the social security. The social security consists of different departments. One of those departments is the NIHDI [National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance]. The NIHDI distributes the money. It goes to the sickness funds and these are public law bodies managed by unions. The Minister holds the guardianship. In other words, the Minister has a veto concerning the decisions of the social partners (e.g. sickness funds and healthcare providers)… (Sickness Fund 1).

Clearly, the agreements made by the other stakeholders need the final approval of the Minister of Public Health. Moreover, it was the Minister who decided to include patient organisations in the Board of Directors of the KCE. The figure of the Minister as a veto player is, thus, important. Tsebelis (2000, p. 442) describes veto players as ‘individual or collective decision-makers whose agreement is required for the change of the status quo’.

Over the past decades, healthcare expenditures have grown significantly. In 2012, health spending accounted for 10.2 per cent of the Belgian GDP, while in 1997 this was only 7.6 per cent (Cantillon, 2008; OECD, 2015). Consequently, rational spending and budget cuts have become important matters and have led to more interventions by the state. For example, in October 2015, the stakeholders within the NIHDI rejected the budget proposal of the Minister because the budget cuts were too deep. She ignored their advice and convinced the government to approve the proposal. This example indicates that role of the Minister as a veto player has important consequences. Here, this discourse on limiting the healthcare spending encourages demedicalisation.

The political and professional background of the Minister also plays a role. For example, the previous Minister – a lawyer, representing the Socialist Party – created opportunities for homeopathy, increasing the medicalisation of alternative medicine, while the current Minister – a physician, representing the Liberal Party – only accepts Evidence-Based treatments (De Morgen, 2013; Vankrunkelsven, 2014), demedicalising alternative medicine. Clearly, politics play a role within the medicalisation process. Through the minister certain political ideologies become more or less prevalent.

This more active role of the Minister is related to the evolution towards a more active welfare state, that focuses on more active investment policies instead of passive protections policies (Cantillon, 2008). The law on financial responsibility of sickness fund agencies is one of the results of this more active welfare state. Another characteristic is the focus on empowerment and individual responsibility, which – as we explained in the first subsection – encourages demedicalisation. Consequently, the health-policy process is not neutral. Welfare state characteristics and political ideologies influence decisions, leading towards both processes of medicalisation and demedicalisation. For example, current neoliberal policies focus on cost containment and individual responsibility that are realised by an increase in state intervention, which encourages demedicalisation. However, these policies also increase the involvement of market-forces in health-policy making (e.g. the pact between the Minister and the industry), which encourages medicalisation.

Mechanisms of medicalisation and demedicalisation

Following these findings, we are able to distinguish some mechanisms of medicalisation and demedicalisation. Table 2 gives an overview of these indicators.

These mechanisms go beyond the specific context of the Belgian case and can serve as indicators for medicalisation and demedicalisation in an institutional context. For example, the USA has a PHI system and health insurance is organised through private insurance companies. As sickness fund agencies, these insurance companies operate within a health insurance market, and they compete with each other for members. The United Kingdom has a NHI system, which is a state-led system. During the Thatcher regime, cost containment and efficiency, which are principles that encourage demedicalisation, were key principles leading government decisions. Hence, state intervention was strengthened, but also some market-forces, whose involvement encourage medicalisation, were introduced (Giaimo and Manow, 1999). These simple examples suggest that these indicators of medicalisation and demedicalisation can be applied to various institutional settings. Nevertheless, comparative research is needed in order to compare these indicators systematically across different institutional settings, and to expand this list of indicators as well.

Conclusion

Recent studies have emphasised the contested and fluid nature of medicalisation. Starting from this premise, we used elite interviews to gain in-depth insight into the political intentions and behaviours of various health-policy stakeholders within the institutional context of the Belgian SHI system. The main goal of this study was to analyse how processes of medicalisation and demedicalisation are constituted within this specific institutional context. This SHI system brings various public and private interests together which results in a constant struggle over what belongs to the medical sphere (and what does not) and, therefore, offers the possibility to observe the fluid nature of medicalisation. Moreover, this case-study allowed us to distinguish between some mechanisms of medicalisation and demedicalisation on an institutional level.

As we have shown, medicalisation and demedicalisation are two different processes that can – and in fact do in our setting – occur simultaneously. This is an important observation that needed more empirical support. Despite drawing on elite interviews alone, ours is a relevant contribution in this line. Moreover, we have addressed three recurring critiques on the validity of medicalisation. First, by focusing on practices and actors, this article goes beyond a definitional approach towards medicalisation. Our study adds to the literature that provides empirical evidence for the multidimensionality of medicalisation. Second, by focusing on the context of the Belgian healthcare system, we brought the institution of medicine back in our analysis and we add to the literature that goes beyond the USA as a single case study. Not only have we analysed medicalisation in another institutional setting, we have used this setting to develop indicators of medicalisation and demedicalisation that go beyond the context of the SHI system, and can be used by other researchers as indicators for medicalisation or demedicalisation. For example, various countries have emphasised the need to involve patients in health-policy making. Researchers who want to gain more insight into medicalisation or demedicalisation by patient organisations can use their funding and type of organisation as indicators. However, this list of indicators is not comprehensive and needs to be validated by comparative quantitative research. Furthermore, although other scholars have offered valuable insight in this field (Buffel et al, 2017; Olafsdottir, 2010), more comparative research on medicalisation in various institutional settings is necessary.

References

AADM. (2015) AADM biedt een alternatief aan!. Press release, 29 June.

Aberbach, J.D. and Rockman, B.A. (2002) Conducting and coding elite interviews. Political Science & Politics 35(4): 673–676.

Abraham, J. (2010) Pharmaceuticalization of society in context. Sociology 44(4): 603–622.

Ballard, K. and Elston, M.A. (2005) Medicalisation: A multi-dimensional concept. Social Theory & Health 3(3): 228–241.

Belgian Official Journal. (1999) Annexe au Moniteur belge du 4 novembre 1999. http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_vzw/vzw.pl. Accessed 30 May 2016.

Belgian Official Journal. (2000) Bijlage tot het Belgische Staatsblad van 15 februari 2000. http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_vzw/vzw.pl. Accessed 30 May 2016.

Bell, A.V. (2016) The margins of medicalization. Social Science and Medicine 156: 39–46.

Berry, J.M. (2002) Validity and reliability issues in elite interviewing. Political Science & Politics 35(4): 679–682.

Brenez, X. (2015) 6 prioritaire hervormingen voor de Onafhankelijke Ziekenfondsen. Brussel: Onafhankelijke Ziekenfondsen.

Britten, N. (2008) Medicines and society. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bryson, J.M. (2003) What to Do When Stakeholders Matter. London: Paper presented at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Buffel, V., Beckfield, J. and Bracke, P. (2017) The institutional foundations of medicalization. Journal of Health and Social Behavior (in press).

Busfield, J. (2010) A pill for every ill. Social Science and Medicine, 70(6): 934–941.

Busfield J. (2017) The concept of medicalisation reassessed. Sociology of Health and Illness. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12538 (advance online publication 4 January).

BVAS. (2015) De verplichte derdebetaler. Press release, 1 July 2015.

Callens, S. and Peers, J. (2015) Organisatie van de gezondheidszorg. Antwerpen: Intersentia.

Cantillon, B. (2008) De architectuur van de welvaartsstaat opnieuw bekeken. Leuven: Acco.

Clarke, A.E., Shim, J.K. (2011) Medicalization and biomedicalization revisited: Technoscience and transformations of health, illness and american medicine. In: A.B. Pescosolido, et al (eds.) Handbook of the Sociology of Health, Illness, and Healing: A Blueprint for the 21st Century. New York, NY: Springer, pp 173–199.

Colombo, F. and Tapay, N. (2004) Private health insurance in OECD countries. Paris: OECD.

Conrad, P. (1975) The discovery of hyperkinesis. Social Problems 23(1): 12–21.

Conrad, P. (1992) Medicalization and social control. Annual Review of Sociology 18: 209–232.

Conrad, P. (2005) The shifting engines of medicalization. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 46(1): 3–14.

Conrad, P. (2013) Medicalization: changing contours, characteristics, and contexts. In: C.W. Cockerham (ed.) Medical Sociology on the Move: New Directions in Theory. Dordrecht: Springer, pp 195–214.

Conrad, P. and Bergey, M.R. (2014) The impending globalization of ADHD. Social Science and Medicine 122: 31–43.

Corens, D. (2007) Belgium: Health system review. In: S. Merkur et al (eds.) Health Systems in Transition. World Health Organization, pp 1–172.

Daue, F. and Crainich, D. (2008) De toekomst van de gezondheidszorg. Brussel: Itinera Institute.

Davis, J.E. (2006) How medicalization lost its way. Society, 43(6): 51–56.

De Block, M. (2015) Speech at the general assembly of the flemish patient platform. Leuven, 14 March.

De Morgen. (2013) Homeopathie enkel nog door artsen met erkend diploma. 12 July. http://www.demorgen.be/wetenschap/homeopathie-enkel-nog-door-artsen-met-erkend-diploma-bbf4ad5b/. Accessed 6 June 2016.

Denis, A. and Mergaert, L. (2009) De financiële situatie van patiëntenverenigingen in België. Brussel: Koning Boudewijnstichting.

Eckert, M., Cools, S. (2016) Farmasector vertroetelt artsen en ziekenhuizen met miljoenen. De Standaard, 23 June, p 8.

EFPIA.. (2016) The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures. Brussels: EFPIA.

Eikemo, T.A. and Bambra, C. (2008) The welfare state: A glossary for public health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 62(1): 3–6.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990) The three worlds of welfare capitalism. London: Polity Press.

Farmaka. (2016) Onafhankelijke artsenbezoekers. http://www.farmaka.be/nl/artsenbezoek. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Giaimo, S. and Manow, P. (1999) Adapting the welfare state. Comparative Political Studies 32(8): 967–1000.

Halfmann, D. (2012) Recognizing medicalization and demedicalisation. Health 16(2): 186–207.

Harvey, W.S. (2011) Strategies for conducting elite interviews. Qualitative Research 11(4): 431–441.

Hassenteufel, P. and Palier, B. (2007) Towards Neo-Bismarckian health care states? Social Policy & Administration 41(6): 574–596.

Illich, I. (1976) Medical Nemesis. New York: Pantheon Books.

Lowenberg, J.S. and Davis, F. (1994) Beyond medicalisation-demedicalisation. Sociology of Health & Illness 16(5): 579–599.

Mills, J., Bonner, A. and Francis, K. (2006) The development of constructivist grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5(1): 25–35.

Minister of Public Health. (2015) Toekomstpact voor de patiënt met de farmaceutische industrie. Brussels: Ministry of Health and Social Affairs.

Moran, M. (2000) Understanding the welfare state. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 2(2): 135–160.

Nonneman, W. and van Doorslaer, E. (1994) The role of the sickness funds in the Belgian Health Care Market. Social Science and Medicine 39(10): 1483–1495.

OECD. (2015) Health at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Olafsdottir, S. (2010) Medicalization and mental health. In: D. Pilgrim et al. (eds.) The SAGE handbook of mental health and illness. London: Sage Publications Ltd., pp 239–260.

Patton, M.Q. (1999) Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research 34(5 Pt 2): 1189–1208.

Pharma.be. (2015) Pharma Figures 2015. Brussels: Pharma.be.

Ramirez, R. (2001) Understanding the approaches for accommodating multiple stakeholders’ interests. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology 1(3): 264–285.

RIZIV. (2014) Medische verkiezingen – resultaten 2014. http://www.inami.fgov.be/nl/professionals/individuelezorgverleners/artsen/beroep/Paginas/verkiezingen-result-2014.aspx#.V1GJlbh97Dd. Accessed 3 June 2016.

Saltman, R., Busse, R. and Figueras, J. (2004) Social health insurance systems in western Europe. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Schepers, R. (1993) The Belgian medical profession, the order of physicians and the sickness funds (1900–1940). Sociology of Health & Illness 15(3): 375–392.

Schepers, R. and Casparie, A.F. (1997) Continuity or discontinuity in the self-regulation of the Belgian and Dutch medical professions. Sociology of Health & Illness 19(5): 580–600.

Schieber, G.J. (1987) Financing and Delivering Health Care. Paris: OECD.

Solidaris. (2016) Dès aujourd’hui, Solidaris rembourse totalement toutes les consultations chez le médecin traitant et le gynécologue. Press Release, 27 April.

Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1990) Basics of Qualitative Research. Newbury Park (Calif.): Sage Publications.

Test-Aankoop. (2016a) Genees de geneesmiddelenindustrie: teken onze petitie. http://www.test-aankoop.be/gezondheid/geneesmiddelen/nieuws/genees-de-geneesmiddelenindustrie-teken-onze-petitie#startpetition. Accessed 23 June 2016.

Test-Aankoop. (2016b) Een slecht rapport voor bijna 900 geneesmiddelen! Press Release, 25 March. http://www.test-aankoop.be/gezondheid/geneesmiddelen/nieuws/geneesmiddelen-weet-wat-u-slikt. Accessed 22 June 2016.

Thomson, S., Foubister, T. and Mossialos, E. (2009) Financing health care in the European Union. Copenhagen: World Health Organization.

Tsebelis, G. (2000) Veto players and Institutional analysis. Governance 13(4): 441–474.

van der Zee, J. and Kroneman, M.W. (2007) Bismarck or Beveridge. BMC Health Services Research 7(1): 94.

Vankrunkelsven, P. (2014) Waarom artsen opgelucht ademhalen nu Maggie De Block op de stoel van Laurette Onkelinx zit, 4 November. http://www.knack.be/nieuws/gezondheid/waarom-artsen-opgelucht-ademhalen-nu-maggie-de-block-op-de-stoel-van-laurette-onkelinx-zit/article-opinion-507917.html. Accessed 6 June 2016.

Wendt, C. (2014) Changing healthcare system types. Social Policy & Administration 48(7): 864–882.

Wendt, C., Frisina, L. and Rothgang, H. (2009) Healthcare system types. Social Policy & Administration 43(1): 70–90.

Williams, S. J., Martin, P. and Gabe, J. (2011) The pharmaceuticalisation of society? A framework for analysis. Sociology of Health & Illness 33(5): 710–725.

Zola, I.K. (1972) Medicine as an institution of social control. Sociological Review 20(4): 487–504.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the organisations that participated in this study, especially to all the anonymous representatives who acted openly and disinterestedly as interviewees. For helping us to have access to these organisations, we have Marc Bogaert to thank. We are also grateful to the Special Research Fund (BOF) of Ghent University for providing funding for the research on which this article is based, the members of the Health, Media & Society research centre, and special thanks go to our colleague, Jana Declercq, for linguistic support and advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Van den Bogaert, S., Ayala, R.A. & Bracke, P. Beyond ubiquity: Unravelling medicalisation within the frame of health insurance and health-policy making. Soc Theory Health 15, 407–429 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-017-0035-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-017-0035-4