We walked in the bush through the night and what happened between my house and where we stopped in the morning was a hell of a beating… They kept beating me every night and said they were just interested in money… I saw dead bodies [of victims whose family could not pay ransom]. But they said they also killed those whose families paid ransom, depending on what they just chose to do. Some of them [bandits] also decided to kill me too but one of them saved me.

Special report: More Nigerians live in fear as kidnap-for-ransom worsens (II), Premium Times, October 8, 2021.

Abstract

This study explores the phenomenon of banditry as a criminal enterprise in Nigeria. By employing qualitative and quantitative data, it provides a historical context for banditry and discusses kidnapping for ransom as its variant. The spatial distribution and patterns of kidnapping incidents are also highlighted. In response to this persistent challenge posed by banditry, the study notes the government and community members have implemented three distinct strategies. They are enhancing security and law enforcement, negotiations, and legislation. The limitations of these responses are also examined. The paper offers guidance on the necessary policy imperatives to effectively combat armed banditry through a multifaceted approach. It emphasizes that addressing the escalating incidents of kidnapping for ransom in the northwest region cannot be addressed independently from the broader need for reform within the security sector of the country. Strengthening border security, preventing the free flow of illicit firearms into the nation, and concerted effort focused on the recruitment, training, and deployment of adequately equipped security personnel to the border areas become pivotal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Nigeria, insecurity has become everyday experience in most communities in recent years. This can be attributed to the nationwide evolution and domination of several non-state armed groups. With divergent motivations, intents, as well as approach, the actors comprise, separatist groups, religious terrorists, criminal gangs, and indeterminate kidnappers, called ‘unknown gunmen.’ Lately, Nigeria’s very crucial security challenge is labeled as banditry. It is a complex crime including vicious murder, rape, illicit possession of weapons, cattle rustling, and kidnapping. The term banditry is a derivative from the word bandit. Banditry refers to the activities of outlawed armed groups that instill fear in people and forcefully seize their belongings. It is comparable to the formation of gangs that employ small and lightweight weapons to carry out attacks on individuals. The starting point of the rapidly growing contemporary studies on banditry has been associated with the influential work of Eric Hobsbawm on social banditry. Hobsbawm in his seminal thesis basically argues that the rapid disintegration of state power and administration in many parts of the world, and the notable decline of the ability of even strong and developed states to maintain the level of law and order they developed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries explain the historical conditions in which endemic, and sometimes epidemic, banditry can exist (Hobsbawm 2000; Ojewale 2024).

The violent actions of bandits precisely affect northwest Nigeria and are fast extending with footholds in the states in Nigeria’s northcentral. Impending evidence indicates an increasing nexus between bandits and terrorists in northwest Nigeria bordering on recruitment tactics and the mutual deployment of logistics and arms (Ojewale 2021a, b). The number of bandits is estimated at about 30,000, scattering astride hundreds of gangs in a range of 10 fighters to over a thousand (Adeyemi 2022). This study focuses on the historical and geographical northwest of Nigeria comprising Kaduna, Katsina, and Zamfara states with the inclusion of Niger state where banditry has become epidemic in recent years (see Fig. 1 below).Footnote 1

In terms of the evolution, scale, spread, and trajectory of banditry in Nigeria, Zamfara, Niger, Katsina, and Kaduna states are properly fitting for this study. More importantly, the conterminous states are also strategically positioned for the purposes of national and regional relevance. For example, Zamfara, Niger, and Katsina are territorially contiguous and collectively border Benin and Niger. The states are also homes historical and contemporary transhumance pathways for human and arms trafficking—highlighting the complexity of insecurity and associated challenges in the states face. According to Good Luck Jonathan Foundation (2021), these four states have a landmass of about 164,370 square kilometers. The large-scale landmass, mainly composed of network of rivers forestlands, and mountains constitute serious policing challenges). The four states are also strategic to both infrastructure and national security in Nigeria. For instance, three major dams serving as the sources of hydro-power to the entire country are located in Niger state. They are Kanji, Jebba, and the Shiroro dams, whereas Kaduna state is widely described as Nigeria’s Westpoint for security planning and military education. Lastly, Nigeria’s northwest is considered a vital region and the bastion of the country’s granary. With farming activities being affected by the bandits who kill, abduct, and threaten farmers, the activities of the criminal groups may aggravate widespread food insecurity if banditry and kidnapping continue to linger (Samuel 2020).

This study sheds light on the multifaceted nature of kidnapping for ransom as a variant of banditry, providing a comprehensive understanding that can inform more effective and sustainable policy responses. By addressing the root causes and impacts, the research seeks to contribute to improved security, stability, and community well-being in affected region. Organized into 10 main parts, the article (after the above introduction) presents the methodology that undergirds the research. The third part historicizes banditry through global perspectives. The fourth section discusses the sociological, criminological, and environmental perspectives as significant theoretical frameworks for understanding banditry. The fifth section analyzes banditry and its transnational linkages to broader instability in the Sahel. It discusses the internationalization of banditry—a terrain that is hardly explored by previous studies in central Sahel. The section six examines the enablers of banditry, while the sections seven and eight provide insights into banditry and the criminal economy of kidnapping for ransom in northwest Nigeria. The section nine appraises governance responses to the growing trend of kidnapping for ransom by bandits. The last section suggests a whole-of-society approach by placing additional emphasis on the roles of the government, community, civil society, and political decision-makers in addressing kidnapping as a variant of banditry in the study area.

Materials and methods

The research method is a blend of primary and secondary data. The study combines literature review with information on attacks by armed groups in the northwest as extracted from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project. The ACLED project collects data from variety of primary and secondary sources on violent events within states, which include armed conflicts, terrorist activities, and violent crime. Data are disaggregated by date, location, and actors. By aggregating local and international news sources using various databases, ACLED coders use local, state, and international media sources to capture violent events across the globe. The data are presented in an excel file and disaggregated according to a country’s geographical and administrative units. For the purpose of this study, the downloaded excel file was edited and converted to a.csv file that can be used in Arcmap. The.csv file was assigned ‘x’ and ‘y’ value and converted to a shapefile. The shapefile was imported into the Arcmap environment as a layer. Thus, the incidents of banditry were defined according to locations using map coordinates extracted from ACLED excel file and georeferenced to determine the spread, concentration, and spatial pattern of attacks by armed groups. Drawing from earlier definition of banditry, attacks associated with kidnapping were extracted for the purpose of data analysis. This methodology becomes pivotal as this article makes significant academic and policy contributions to literature by providing an empirical mapping of attacks and kidnapping by bandits in Nigeria’s northwest. The map on incidents could assist security and law enforcement agents in understanding the spatial pattern, scale, and concentration of attacks and the best way to respond. In addition, establishing a stronger link between theory and practice, the methodology can also provide a scientific understanding of the factors that affect the distribution and frequency of attacks and kidnapping, with a view to improving prevention policies and programs in any conflict setting. As shown on Table 1, key informant interviews were carried out across 29 communities with an array of 32 respondents drawn from 16 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Kaduna, Katsina, Niger, and Zamfara states. One interview was also conducted in neighboring Sokoto state in the border area with Niger based on snowballing and advice from interviewed respondents in the four major states. This is with a view to understanding the cross border linkages to banditry and kidnapping in the study area.

Respondents include members of vigilante group, traditional rulers, cattle breeder/pastoralist, former and battlefield bandits, leaders from Fulani communities, farmers, and religious leaders (Muslim and Christian clerics). Others are leaders of Kautal Hore (a Fulani socio-cultural organization), leaders of women groups and local civil society organizations, law enforcement and security personnel, and school teachers and parents particularly in communities where abduction of school children for ransom has become endemic lately. Respondents were asked about how their communities are being affected by banditry. Questions raised include the following: What are the causes of banditry? Who are the bandits operating in Nigeria’s northwest? Why has banditry worsened, and became intractable to state and community responses? How do bandits operate kidnapping for ransom in the northwest? In the events of abduction, what forms of abuse were victims subjected to by the bandits? What factors make communities vulnerable and soft targets for bandits? This approach affords a degree of comprehensiveness as research questions were further operationalized for the purposes of validity, reliability, and objectivity for data collection and analysis. Evidence is deliberately sought from a wide range of independent sources and by different means, comparing and triangulating oral testimonies with literature review and quantitative research findings. Most research participants consented to be quoted and referenced anonymously due to the security sensitivity of the study.

Historicising banditry and kidnapping: the global perspectives

Banditry encompasses various criminal acts such as cattle rustling, kidnapping, armed robbery, drug abuse, arson, rape, and brutal massacres of people in rural communities, often utilizing sophisticated weaponry (Uche and Chijioke 2018; Rosenje and Adeniyi 2021). Another study defines banditry as the act of attacking and looting victims by semi-organized groups, whether planned or spontaneous, using offensive or defensive weapons, with the aim of overpowering the victim and acquiring loot or achieving certain political objectives (Shalangwa 2013). These bandits are typically viewed as outcasts, desperate marauders who operate outside the boundaries of the law, lacking a fixed abode or destination as they roam through forests and mountains to evade identification, detection, and arrest by security and law enforcement agencies (Ojewale 2023a).

Throughout history, banditry has been a prevalent crime in many countries, with varying antecedents. In Latin America during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, banditry was sometimes used as a means of political uprising and economic opportunity in situations where opportunities were limited. Bandits would often attack both people and property, and some would even state a political agenda. In certain cases, such as with Gaucho brigands in Argentina and bandits in Brazil, Bolivia, and Cuba, the masses viewed them as heroes who were standing up against their wealthy oppressors. However, banditry was also chosen by rural poor in places like nineteenth-century Mexico and Hispanic bandits in California and the Spanish borderlands due to the lack of legitimate alternatives. While personal gain was often the central motive for bandits in Mexico, Peru, Brazil, and Cuba, they occasionally received support from local elites rather than commoners. As a result, outlawed networks often crossed class lines and committed crimes for a variety of reasons.

During the period of 1920–1922 in the Soviet Union, banditry emerged as a result of the peasant revolution. The uprising was fueled by the deep-seated animosity toward the Bolshevik agrarian practices associated with Lenin's policy of war communism. This policy involved the collective production of grain, compulsory delivery at fixed prices, and forced requisitions, which the peasants grew to resent. They felt burdened by their role as a constant source of food for the Soviets and as recruitment centers for the Red Army. Consequently, the Green Movement emerged, resembling a band of pirates, and attracted a multitude of adventurers, criminals, deserters, and freebooters who exploited anarchism as a means to plunder. While numerous bands spread terror throughout Russia, the majority of the violence was concentrated in Ukraine. Here, partisan leaders easily tapped into the idea of Ukrainian independence and capitalized on the prevailing spirit of anarchism in the region. The three most prominent groups responsible for the widespread violence were led by Nikifor Grigoriev, who established his stronghold in the lower Dnieper region; Zelenyi, who controlled the area around Kiev; and Nestor Makhno, who operated in the prairie northeast of Crimea (De Lazari n.d.).

In South Africa during the period of 1880s and 1890s, bandits operated as gangs. They seized control of hamlets and took occupation of small frontier towns. They engaged in the damaging of properties, thefts, and threatened vulnerable retailers who refused to provide them with the credit or goods they demanded. They were regarded by law enforcement agencies as antisocial elements, diamond and gold smugglers, highwaymen, murderers, rapists, and thieves in dark world (Van Onselen 2014). In east Africa, banditry is viewed as an emergence a new system of predatory exploitation of economic resources. This problem manifests in various forms and it is becoming endemic in northwestern Kenya through cattle rustling among the pastoral communities. The phenomenon is causing great concern with new trends, tendencies, and dynamics, leading to commercialization and internationalization of the practice (Osamba 2016).

Banditry in northwest Nigeria has a long history dating back to 1901 when bandits attacked a caravan and stole goods worth £165,000, killing 210 traders (Rufa‟i 2018). In recent times, the resurgence of banditry in the region can be traced to the killing of Alhaji Isshe, a Fulani leader, by the Yan-Sa-Kai vigilante group in 2012. This led to reprisal attacks and mass killings of innocent people by the bandits of Fulani extraction. The gang grew in number, strength, power, and weapons, and even had connections with neighboring countries such as Niger, Mali, and Chad (Auwal 2021). This is in line with the scholarly argument that co-membership of organized crime groups is higher among individuals who share the same ethnicity and nationality, commit acts of violence, and perpetrate crimes in the same area. It conforms to the notion that recruitment from a small area and similar ethnic/national background increases cooperation among criminal groups (Campana and Varese 2020).

There has been a gradual transformation from the elementary and isolated roots of banditry to a complex transnational and fast spreading security threat. From Latin America to the Soviet Union; South Africa to Kenya, and lastly Nigeria, in Nigeria, bandits have historically followed a similar path in terms of their development, organization, and operational strategies, albeit with subtle differences specific to various regions. Notably, well-established studies argue that these bandits can reach a level of violence that proves difficult for governments to effectively counter, as the capacity of state security actors to uphold public safety visibly declines while criminals engage in new forms of predatory crime such as looting, pillaging, and kidnapping for ransom (Creveld 1991; Kaldor 2013).

Kidnapping for ransom has long history across countries and regions of the world. For example, kidnapping for ransom characterized the annals of the Italian Republic for virtually 30 years (1969–1998). Approximately 700 individuals fell victim to anonime sequestri (criminal syndicates known for their involvement in kidnapping) and rooted in Sardinian banditry, the Sicilian Mafia, and the Calabrian’Ndrangheta. The primary targets of these abductors were predominantly men from the upper middle-class, with women and children being targeted less frequently. The captives were forcibly confined in deserted residences, forests, caves, and subterranean passages, enduring harrowing experiences such as sensory deprivation, mutilation, torture, and constant fear of death (Montalbano 2016).

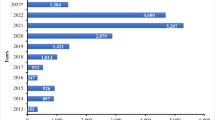

The illicit economy of kidnapping and ransom payment continues to grow with the resurgence of armed groups in various countries such as Congo, Mali, Chad, Central Africa Republic, and Nigeria and so on. This places Sub-Saharan Africa in the lead of regions (see Fig. 2) with a dynamic kidnapping environment underpinned by gross failure of governance. More recent global rankings identify the top five riskiest countries for kidnapping for ransom as Mexico, India, Pakistan, Venezuela, and Nigeria (Pires and Guerette 2019). Nigeria in particular is thought to be the new kidnapping capital of West Africa, because a combination of diverse armed groups and the inability of the state to effectively manage crime and criminal groups has drawn comparisons to the conditions in other failed states. Extant study argues that kidnappings for ransoms are generally found in failed or collapsed states (Hastings 2012). Thus, in recent years, kidnapping has emerged as a crime of choice for the bandits. In this context, kidnapping is the act of forcefully seizing and detaining or transporting a person without their consent, often accompanied by a demand for ransom. This heinous act involves taking a person away from their loved ones with the intention of holding them captive and profiting from their family's distress (Lobo-Guerrero 2007; Uzorma and Nwanegbo-Ben 2014; Otu and Adedeji 2021). In Nigeria, kidnapping and abduction act of 2017 prescribes a strict punishment of thirty (30) years' imprisonment for anyone caught conspiring with an abductor to receive ransom for an individual who has been wrongfully confined. Moreover, it explicitly states that individuals involved in kidnapping activities leading to the death of another person will be subject to the most severe penalty of death (Olujobi 2021). The subsequent sections present the theoretical framework for understanding banditry and kidnapping for ransom in northwest Nigeria.

Source: Control Risks: Kidnap for Ransom in 2022 (Control Risks 2022)

Kidnaps by region, 2021.

Theoretical framework: sociological, criminological, and environmental perspectives

Sociological, criminological, and environmental theories are indispensable in a bid to provide scholarly understanding on the character of banditry. Such theories serve as guides for researchers, analysts, and advocates, accentuating their comprehension of the dynamics underpinning crime, the emergence of bandits and their staying power, and the ways in which they disrupt society. By applying theoretical perspectives to the analysis and interpretation of banditry, open-minded policymakers who are seeking to develop effective strategies for dealing with crime can also gain useful insights that would shape community and institutional responses to crime (Barlow 1995; Alemika 2013). Thus, such theories include routine activity theory—Cohen and Felson, the social disorganization theory, developed by Shaw and McKay, deprivation theory first proposed by Bonger Willem in 1906, ungoverned spaces theory (Clunan and Trinkunas 2010), and rural vulnerability theory. These are elaborated subsequently.

Developed by Cohen and Felson, the routine activity theory emphasizes that crime occurs when three elements align: a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of a capable guardian. This theory takes into consideration the routine activities of both the offender and the victim. Routine activity theory relies on the rational choice methodology often deploy by the criminals. Furthermore, according to the theory of social disorganization, in communities characterized by disorganization or a lack of collective efficacy, the erosion of informal social controls enables the rise of criminal cultures. In current scholarly debates on crime and security governance, such places are often characterized as ungoverned space. The proponents of ungoverned spaces basically argue that almost all countries have remote areas within which formal governments do not matter much. The notion of ungoverned spaces as a critical threat to governments and their interests is gaining momentum worldwide. These spaces are commonly associated with failed states, or states that struggle to assert their sovereignty effectively. The ungoverned space theory suggests that violent jihadism, terrorists, proliferators of weapons of mass destruction, narco-traffickers, and kidnapping gangs often emerge where there is a lack of authorities and institutions to stop them. The theory also finds application in the virtual realms, such as cyberspace and global finance, and underscores the ease with which non-state actors can bypass state surveillance and erode state sovereignty (Clunan and Trinkunas 2010).

An opaque area of activity involves the state’s inability to monitor or control certain criminal activities such as terrorism financing, hostage taking, attack on rural communities and critical infrastructure, and kidnapping for ransom. In Africa, this tends to a capacity problem. This is because, even when the states enact laws to engender protection and welfare of citizens, they may not have the resources to guarantee their enforcement. More importantly, incapacity and the lack of political will may also interact. Moreover, in Africa, it is not uncommon to observe the amplification of ungoverned territories when the central government collapses. This occurrence often paves the way for the emergence of alternative forms of governance that compete with each other over a certain period of time (Whelan 2006). However, the assertion is made by extant study that unregulated territories can be a security risk, yet armed organizations are seldom the culprits behind their establishment. Instead, the cause of their emergence is attributed to deficient governance that curtails the quality of life and deprives the people of their fundamental necessities (Taylor 2016).

Deprivation theory is typically used to explain a series of social problems, such as conflicts, and social unrest. Subjectively, deprivation as a sociological idea has been classified into absolute and relative deprivation, which have been considered important causes of crime. Bonger Willem introduced the concept of absolute deprivation in 1906, as documented by Hightower et al. (1970). Absolute deprivation typically pertains to the condition resulting from extreme poverty or the absence of essential resources necessary for survival. This is also well situated in the classical theory of social contract which recognizes the individual’s natural right to survival at basic levels. Since without food, clothing, and shelter, the individual will not survive, it is clear that the terms of any binding social contract cannot be limited to protection of person and property, as they do in classical versions of the theory, but must include the provision of food, clothing, and, shelter, or the employment to guarantee them. If the state should decline to furnish these necessities, the classical theorist of society evolution argues that the member must retain the same rights he would have if the state were to decline to provide protection of person and property. Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau agree that if the commonwealth fails to perform its role in delivering security, the social contract is broken. Therefore, absolute deprivation was once thought to be an important reason for the high crime rates and extreme social unrest in many societies. Poverty rates or individual income levels are typically thought to be strongly correlated with deprivation (Faison 2016).

The social disorder theory—a more ecological approach emphasizes the role of local physical and social environments in engendering fear of crime. Fear of crime has been a serious social problem studied for almost half a century. Initially, scholars directed their attention toward the operationalization and conceptualization of fear of crime, with a specific emphasis on understanding its nature and distinguishing it from other phenomena. In theorizing the fear of crime, two perspectives have emerged over the years (Rader 2017). The first approach conceived the fear of crime as “risk.” That is, how likely is it that a person will be a victim of a particular crime (Ferraro and LaGrange 1987; Ferraro 1995; LaGrange, et al. 1992). According to certain scholars, fear of crime should be defined as the emotional response to the potential of being victimized, whereas "perceived risk" should be defined as the probability of victimization risk. These concepts are related but distinct in the fear of crime literature. For instance, one's perceived risk of becoming a victim may influence their level of fear of crime (Rountree and Land 1996; Mesch 2000; Warr 2000; Rader et al. 2007; Wyant 2008).

According to Rader (2017), there are several predictors of fear of crime at the individual level. These include social class and previous victimization. On the socioeconomic aspect, existing research has shown that individuals with lower income levels tend to have a higher fear of crime compared to their wealthier counterparts (McKee and Milner 2000; Pantazis 2000). This can be attributed to the social and physical vulnerability experienced by those in poverty. They may reside in areas with a higher likelihood of criminal activity, making them more susceptible to victimization. Additionally, they may lack the means to protect themselves due to inadequate policing or neglect (Pantazis 2000; Scarborough et al. 2010). The relationship between fear of crime and previous victimization has been extensively studied, with mixed results (May and Dunaway 2000; Schafer et al. 2006). Some studies suggest that victimization experiences increase fear of crime (Ferguson and Mindel 2007; Katz, et al. 2003), while others indicate that it decreases fear (Mesch 2000) or has no effect (Ferraro 1995). Research has also explored the impact of vicarious victimization, where individuals who know or hear of someone who has been victimized are more likely to fear crime (Skogan and Maxfield 1981; Chiricos, et al. 2000; Eschholz, et al. 2003). The foregoing theories present a scholarly legacy which has been described as urban-centric and global north-dominated postulations on crimes dynamics.

Ceccato and Abraham (2022) argue that the prevailing theories in criminology predominantly revolve around urban settings, neglecting the significance of non-urban contexts. These theories heavily rely on the concept of "urban neighborhoods" and often overlook the intricate dynamics of crime in globalized rural areas. Furthermore, they fail to acknowledge the variations in crime patterns worldwide, particularly in countries of the Global South (Carrington et al. 2015; Ceccato and Abraham 2022). Therefore, the introduction of rural vulnerability theory provides contemporary understanding on how to integrate crime dynamics in rural areas to the global academic and policy discourse. The proponents assert among other themes that rural areas are under constant transformation; violent crime characterizes rural contexts in the global south; rural safety is an environmental issue; crime underreporting in rural areas is a problem, and policing and crime prevention models often neglect rural challenges (Ceccato and Abraham 2022). Certain crime opportunities are only present in the rural areas, because they are largely determined by low population density which makes detection difficult in most regions. The absence of people in certain areas can lead to undetected crime, such as the illegal dumping of waste in forests or cattle rustling in sparsely populated regions. Rural communities may also have a higher tolerance for certain types of behavior and crime, which can contribute to the prevalence of criminal activity. Furthermore, the influx of people into rural areas due to mineral extraction operations may also lead to an increase in crime (Ruddell 2017; Ojewale 2021a, b).

More importantly, the rural areas of the global south are contested spaces where violence is part of daily life. This is particularly true in central and south America, Africa, and most parts of Asia, where crime encompasses armed robbery, organized crime, killings related to land-reform, and environmental conflicts (Ceccato and Abraham 2022). Examples include rural patterns of violent crime in farming communities of Zimbabwe (Rutherford 2004), extractive crime by artisanal miners and international mining companies in eastern DRC (Ojewale 2022a, b), and farmer herder clashes in Nigeria’s north central (Ojewale 2023a, b). The foregoing theories find application in two distinct domains—vulnerability of victims of crime and susceptibility of disadvantaged population to recruitment by criminal groups. In subsequent sections, the findings of this study are highlighted, discussed, and situated in the theoretical explanations.

Banditry in northwest Nigeria and transnational linkages to instability is the Sahel

The West African Sahel region is one of the most unstable regions in the world. The violence-induced instability in the region is worsened by the combination of poor socioeconomic outcomes and a heavily militarized response to multiple insurgencies. This situation is particularly evident in countries such as Chad, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and the northern fringes of Burkina Faso and Nigeria (Olojo et al. 2020; Ojewale 2022a, b). The Sahel region faces many connected and complex political, social, economic, and security challenges. These continue to undercut the upshot of the conditions required for durable peace, confirming that the Sahel might remain trapped in a cycle of violence and vulnerability (Global Terrorism Index 2022). The Sahel region is currently experiencing a complex conflict landscape, primarily driven by the proliferation of non-state armed groups, counter-insurgency activities undertaken by state forces and international partners, and the establishment of armed self-defense militias at the village level.

This conflagration of conflict is most pronounced in central Mali and Burkina Faso, but its ramifications are swiftly extending into neighboring countries in coastal West Africa. Additionally, it is exacerbating the levels of violent crime in northwest Nigeria.Footnote 2 Existing ethnic tensions continue to exacerbate rising insecurity (Fominyen 2020). For instance, the Tuareg and Fula people usually come into conflict over land. In Niger, Nigeria, and Burkina Faso, the Hausa people are gradually moving further north to find new farmland to grow crops. Nevertheless, in doing so, they come into direct conflict with pastoralists, who also utilize the land for grazing and other farming activities. This, in turn, often leads to violent confrontations along ethnic lines (Jeanneney 2016). Each of these potential tensions further exacerbates ethnic and religious opposition and paves the way for violent crime such as banditry as noted by a battlefield Bandit in Kagara Town, Rafi Local Government Area, Niger State.Footnote 3 At the onset of the fratricidal war between the Fulani and Hausa groups which occasioned the resurgence of banditry in Nigeria’s northwest, the former drew members from neighboring countries such as Niger, Mali, and Chad, mostly Tuaregs with links to Sahelian rebels (Auwal 2021).

Therefore, banditry in Nigeria’s northwest is exacerbated by multiple conflicts in the Sahel through recruitment by transnational criminal groups and arms trafficking according to a member of vigilante group in Tagina, Rafi Local Government area in Niger state. Furthermore, a custom officer in Jibia, Katsina state, is equally attested to this development in the border area as quoted below.Footnote 4

Banditry is caused by many things including general insecurity in the west African region, increased poverty among population and fierce competition for limited resources. These are the pertinent factors. Securing a large border… requires a lot of resources which we currently don't have. If our border is secured, those bandits would not be able to sneak into the country. They come through illegal tracks. Illegal routes are not government designated entry and exit points, hence they lack the usual border security apparatuses… Arms, drugs, other prohibited items are smuggled into the country through these illegal routes. And the problem is that these routes are so many that no one could tell… there exact number and location. Banditry is worse because of the porosity of our borders. Arms proliferation has become so intense. Most of such arms and weapons are smuggled into the country from other places [in the Sahel] via our porous border routes. The arms have entered so many hands including criminals.Footnote 5

While the Boko Haram insurgency in Niger's eastern region (Diffa) and the Liptako-Gourma crisis in the western regions (Tillabéri and Tahoua) receive significant attention in terms of international security considerations, it is crucial not to overlook the escalating situation in the Maradi region. Located along the country's south-central border with Nigeria, Maradi has become a new focal point that adds strain to national efforts aimed at addressing insecurity. The expansion of organized banditry from Nigeria's northwest since 2017 has brought about challenges such as rampant cattle rustling and frequent kidnappings for ransom in Maradi as noted by border official in Jibia, Katsina state.Footnote 6 Under the cover of night, armed militias originating from Zamfara and Katsina states in Nigeria breach the border using motorcycles as their mode of transport. Their objective is to launch attacks on the local inhabitants before seeking refuge in the ungoverned territories of the Baban Rafi Forest, which stretches across the shared borders of Niger and Nigeria (Koné 2022).

More importantly, at the tri-border region, where the frontiers of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso meet, evidence shows that militants from the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP)—a splinter group of Boko Haram provided reinforcements to Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) in a recent attack at Tahoua. Although the hotspot of ISGS activities is located over one thousand kilometers from Boko Haram and ISWAP’s main area of operations in northeastern Nigeria, this development portends an expansionist agenda of the terror groups with increasing geographic scope. Additionally, criminal and jihadi activities are converging in Nigeria's northwest, which is much closer to the tri-border area, as the region becomes more insecure. Banditry, especially kidnapping for ransom, is prevalent, and there is a possibility of some level of coordination between primarily criminal bandits and various jihadi groups. The mutual use of logistics and arms also provides evidence of a nexus between the bandits and terrorists in the northwest region. There have been instances of arms trading between these groups, particularly the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) (Campbell and Quinn 2021). Military source confirmed terrorists from Tillaberi region of Niger have been intercepted recently in Nigeria northwest, and drugs, small and light weapons, and ammunition recovered from them according to the official source with the custom officials in Ilela Local Government Area of Sokoto state.Footnote 7 The gradual advancement of weaponry utilized by bandits indicates the existence of an extensive international arms smuggling network that extends across Nigeria's northwest and the central Sahel (Ojewale 2021a, b). The next section focuses on the enabling factors of banditry in northwest Nigeria.

Enablers of banditry

The northwest region of Nigeria is highly susceptible to frequent violent attacks carried out by bandits. This vulnerability arises from a convergence of various factors that consistently contribute to the problem. These factors include poorly handled conflicts over resources between pastoralists and farmers, internal warfare between the Fulani and Hausa communities, illicit gold mining activities, diminishing support for rural livelihoods, ineffective border management, insufficient presence of law enforcement agencies, and the proliferation of ungoverned spaces as noted by a resident teacher at Guga community in Bakori Local Government Area of Katsina state.Footnote 8 Yenwong-Fai (2012) points out that the Nigeria Custom and Immigration Services have failed to effectively police the 1497 km border between Nigeria and Niger. Consequently, a pastoralist interviewed in Rini- a town in Bakura LGA in Zamfara state noted the porous nature of these frontiers increases the risk of criminals entering Nigeria from neighboring countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.Footnote 9 The border's vulnerability to criminal groups infiltrating is heightened by the existence of forest reserves in the surrounding area. The vast and rugged terrain, combined with a sparse population and dense vegetation, create formidable challenges for surveillance efforts. Consequently, these forests provide ideal sanctuaries and operational bases for the bandits, making it even more difficult to combat their activities. According to the residents of Birnin Gwari in Kaduna state, these forests are beyond the surveillance of security forces and have gained notoriety as safe haven of armed groups.

There is a very big forest with remote villages inside it. This forest borders with many states including Niger, Zamfara and Katsina... Criminals come from other places through the border areas. You don't see them on the main roads where security operatives are patrolling. They come through [porous] borders and live in the forest. Some terrains are not even motorable. They [terrorists and bandits] use motorcycles or even trekking in some cases. All this make it difficult for the security operatives to be able to reach and navigate those places.Footnote 10

Consequently, as shown on Fig. 3 above, these zones represent ungoverned territories, where the authorities' existence is either absent or, at most, irregular (Olaniyan 2017). The criminals causing havoc in northwest Nigeria are notorious for imprisoning their kidnapped victims in the adjoining forest according to a police officer in Zurmi, Zamfara state.Footnote 11 This is also confirmed by a leader of the pastoralists in Mariga town in Bangi Niger state.

We don't have government here. They don't come to remote areas where this thing [banditry] is taking place. Even the military is not coming to this place. We use to report this tragedy previously, we have stopped now because even if you manage to report such cases nothing is done. What we do now is that we get our own arms like those [Cattle] rustlers. We defend ourselves to the best of our ability.Footnote 12

The rise in kidnapping incidents in northwest Nigeria often reflects the presence of weak, exclusionary, or exploitative governance systems. This is compounded by various factors, including the lack of institutional capacity within the police, extreme inequality, poverty, and high unemployment rates. Additionally, there is a growing sense of alienation among citizens toward the government (Olugbuo and Ojewale 2018). Notably, Katsina and Zamfara, located in the northwest, are among the ten poorest states in the country (Chukwuemeka 2022). The combination of rapid population growth, inadequate governance, and widespread poverty exposes many unemployed young individuals to recruitment by criminal groups operating in the region (Jerry 2019; Abdulaziz 2021). Moreover, the impact of climate change further exacerbates the situation by disrupting people's livelihoods and making impoverished farmers and vulnerable youths more susceptible to engaging in banditry (Ojewale et al. 2024). It is crucial to recognize that the underlying cause of banditry stems from the long-standing competition for land and water resources between predominantly Fulani herders and mainly Hausa farmers. Over time, both groups have mobilized armed bandits and vigilantes as defense forces (Wuyo 2021; Channels TV 2021).

In an endeavor to put a stop to these attacks, and in light of the federal government's failures, the state governments of Katsina and Zamfara took the proactive step of engaging in direct negotiations with the bandits. As part of these negotiations, the governors offered amnesties and other incentives to the criminal groups in order to bring an end to the violent assaults. However, these agreements proved unsuccessful for various reasons. Firstly, the criminal groups lacked a centralized command structure and a shared objective, making it difficult to unite them in a common negotiation. Additionally, agreements made with one group of bandits did not hold any sway over the others. Secondly, the exclusion of local communities, who bear the brunt of the violent crimes and expect the state to provide compensation, justice, and protection as prerequisites for sustainable peace, further hindered the success of these dialogues. The breakdown of negotiations resulted in a resurgence of attacks by the bandits. Moreover, the competition for access to mineral resources in Katsina and Zamfara states exacerbates existing tensions. Often, the bandits control these mines and are able to act with impunity due to the undue support they receive from authorities through collusion (International Crisis Group 2020); Ogbonnaya 2020). The enablers of banditry are further summarized in Fig. 4.

Banditry and the criminal economy of kidnapping for ransom in northwest Nigeria

Nigeria’s National Security Strategy shows that banditry constitutes about 40% of national insecurity in Nigeria (National Security Strategy 2019). In recent times, there has been a surge in the audacity of bandits who have executed well-planned assaults on the nation's primary defense academy in Kaduna and a military base in Zamfara state (Ojewale et al. 2022). Tragically, during both incidents, 14 officers lost their lives, one was taken hostage, and valuable military equipment was looted. These isolated occurrences have dealt a significant blow to the ongoing efforts to combat violent crimes in the neighboring states. However, the prevalence of mass abductions for ransom has been on the rise in recent years. Bandits have established a kidnapping economy, utilizing the ransom payments they receive to finance their acts of terror (Ojewale et al. 2022; Ojewale and Balogun 2022). In the first month of 2021, a series of alarming incidents involving bandit attacks have unfolded, specifically targeting school children and resulting in the abduction of over 1000 students (Nnachi and Isenyo 2021). This is well situated in the evidence provided by residents of the remote villages and towns affected by kidnapping of school children in Bakura Local Government Area of Zamfara state.

…many of our women are either killed or kidnapped. There is hardly a family in this village that has no woman victim. They have attacked the village I think twice. The last attack was last year and more than 30 people lost their lives and many were kidnapped. We had to gather money in order to pay for their lives. Some of them died in captivity.Footnote 13

In Nigeria, there are six recognized modalities of kidnapping, as outlined in Fig. 5. These modalities consist of the routine model, invasion model, highway model, insider model, seduction model, and feigned model (Onuoha 2021). Notably, bandits in the northwest region predominantly adopt the routine model, invasion model, and highway model when carrying out their criminal activities.

Source: Onuoha (2021)

Analyzing kidnapping through different models.

Due to the lack of effective governance, bandits have capitalized on the security vacuum and successfully assumed control over various territories. They have implemented taxation, restricted the freedom of movement for individuals, and resorted to kidnapping people in exchange for ransom. Banditry has translated to a generalized violence against civilians, and most people in the rural communities are becoming increasingly vulnerable according to interviewed resident and in Nasarawa Mai-Layi, Birnin-Magaji, Zamfara State.

There is hardly a community in Birnin Magaji that has not been affected by banditry in one way or the other. Nasarawa Mai-Layi has been devastated by activities of bandits. Most of the residents have left the community. Many homes are empty, because their inhabitants have left them and have taken refuge in safer places. Bandits attacks on Nasarawa Mai-Layi was so frequent that people from outside have stopped coming to the town completely. We have witnessed many mass burials. Sometimes 50 people can be killed by bandits in a single attack. Our mosques, markets, homes and schools were all attacked at one time or another. We are all used to cattle rustling, forced migrations, kidnappings, and other forms of attacks by bandits.Footnote 14

According to Hobsbawm's historical archetype, bandits are groups of armed men who operate outside the law and authority, using violence and extortion to impose their will on their victims. This form of territorial capture challenges the economic, social, and political order by defying those who hold power, law, and control of resources. As depicted in Fig. 6, there has been a 32% increase in banditry incidents in 2021 compared to 2020, with 30% of attacks taking place in Kaduna state. These bandits operate from ungoverned forests and have killed over 1566 civilians in the four states, representing a 34% increase from 2020. In 2021, kidnapping by bandits increased by 160% compared to 2020. From 2014 to 2022, 4017 persons have been abducted by bandits in the four states. Between 2014 and 2018, there were sporadic cases of kidnapping by bandits, reaching a peak of 8 incidents in 2018. However, starting from 2019, the number of abductions by bandits has been increasing exponentially, with 21 incidents in 2019 and a staggering 135 incidents in 2021. According to ACLED's estimation, a total of 671 civilians were abducted by bandits from January to June 2022, accounting for approximately 31% of the total abductions reported in the region in 2021.

The data collected by ACLED rely on local groups and media reports, and many incidents may well go unrecorded. Since 2020, the trend of kidnapping by bandits shows increasing incidents which eventually outstripped the record of killings by bandits in 2021. This dynamics portends a shift from wanton killings of innocent citizens to a criminal economy of ransom payment which yields humongous financial benefits to the bandits. Therefore, the bandits have taken to kidnapping for at least two principal reasons. The first is the economic incentive it provides as source of financing through ransom payment. The second important factor is that abducted civilians are used as human shields against possible military onslaught through aerial bombardment and land operations. This limit the containment policy of the military, because the rule of engagement against the bandits with abducted civilians in their custody differs significantly compared to regular operation. This is in a bid to avoid or lessen humanitarian casualty in the forests which serve as enclave for the bandits.

The criminal economy of ransom payment

A disaggregated data on ransom payment to bandits from geo-political zones are hard to come by or estimate in Nigeria. However, extant data on the criminal economy of ransom payment in Nigeria reveal a complex challenge. Between 2011 and April 2020, Nigerians paid bandits a total of $18.34 million to secure the freedom of their family members. The largest portion of this amount, which was almost $11 million, was paid by victims to kidnappers between January 2016 and March 2020 (Oloyede 2020). In April 2021, the Zamfara government disclosed that the bandits collected 970,000,000 as ransom from victims’ families between 2011 and 2019. The parents of the abducted students from Greenfield University in Kaduna state reportedly paid a ransom of N150,000,000 and provided eight motorcycles to the bandits in order to secure the safe return of their children. Similarly, the kidnapped pupils from Tanko Salihu Islamic School in Tegina, Rafi Local Government Area of Niger State, were released by the bandits after paying a ransom of N50,000,000. Additionally, the bandits released the village head of Guga in Bakori local government area of Katsina state, along with 35 other residents, after collecting a ransom of N26,000,000 (Babangida 2022). The sum of 800,000,000 was paid recently for the release of seven of the abducted passengers on ill-fated Abuja-Kaduna bound train. The remaining families are expected to pay 4, 300,000,000 for the release of their relatives (Odeniyi 2022).

Between July 2021 and June 2022, 19,357,000,000 billion was demanded in exchange for the release of captives while a fraction of that sum (1,647,100,000) was paid as ransom (SBMintel 2022). Based on the official exchange rate (1 USD = 415.9 NGN) between the naira and the US dollar on August 1, 2022, these figures translate to $,46,540,033.7 and $3,960,327, respectively. The figures were arrived at using media reports detailing the sum paid to armed groups. Certainly, the figure will be higher than what is reported, because of the clandestine negotiations and opacity that undergird ransom payment coupled with the fact that not all the payment made to the various criminal groups as ransom is usually reported in the media. These figures are particularly important because of the rising poverty levels in the country and how the crime is affecting the economically disadvantaged cohort of the citizens in towns and villages. Indeed, Katsina and Zamfara considered as the hotspots of banditry and abduction in the northwest are two of the country’s 10 poorest states (Chukwuemeka 2022). Testimonies from families affected in the northwest region reveal the devastating consequences of paying ransom, which not only deprived them of their means of sustenance but also resulted in the loss of their cherished family members. To secure the freedom of their abducted loved ones, certain individuals have found themselves burdened with overwhelming debts incurred from borrowing, while others have resorted to selling their valuable possessions like farmlands, livestock, and other properties. The impact on the people remains alarming as noted by a senior official of community school in Gatakawa, Kankara, Katsina state.

Gatakawa community has continued to experience attacks since 2020. Bandits have collected millions of naira from the residents as ransom for the abducted people. Ransom payments have made many families broke. People have to dispose off some commodities in order to raise money for ransom.Footnote 15

In many areas, killing and abduction by bandits have become so pervasive (see Fig. 7), and people can no longer go to the farms for fear of being kidnapped. Recently, the bandits have adopted a new tactic of intimidating the farmers, extorting large sums of money from them in exchange for a promise of protection from being killed or abducted while working on their farms. These impoverished individuals are left with a dire dilemma—either risk their lives by continuing to work on the farm or abandon their livelihood, migrate to the city, and endure a life of urban suffering (Chukwuemeka 2022; Morgan and Ayantoye 2022; Daily Trust 2019; Ibrahim 2021; Oloyede 2020). The negotiation for ransom payment which is facilitated by middlemen who act as bridge between the families of the victims and bandits has also attracted scrutiny from security forces and the media lately. This borders on the thin line between altruism and complicity. The Zamfara state government established a committee in October 2019 to recommend measures to combat armed banditry.

The committee's findings revealed that five Emirs and 33 district heads were complicit in the complex issue of criminal activities linked with banditry in the state. One of the traditional rulers reportedly received N800,000 naira (approximately $2,050) from bandits as his portion of the ransom paid for the release of a senior state official's kidnapped wife and children (International Crisis Group 2020). Furthermore, a frontline negotiator for the release of persons abducted on a train in Kaduna, in March 2022, was arrested by the State Security Service in September 2022. The authorities uncovered incriminating materials, including military accouterments, substantial sums of money in various currencies and denominations, as well as financial transaction instruments, at his residence and place of work. It has been officially announced that he will be prosecuted in court, as confirmed by the authorities (Abdullateef 2022).

Governance responses to the growing trend of kidnapping for ransom by bandits

As Nigeria continues to experience the shocks of attacks and kidnapping by bandits, the national and subnational governments are providing counter measures to confront the challenges of banditry. Three distinct but complimentary approaches have been noted. They are security and law enforcement response, legislative framework, and negotiation.

Security and law enforcement strategies

Within the constitutional framework of security in Nigeria, the Nigeria Police Force (NPF) has been given the task of maintaining law and order. The NPF's primary role is to engage in mainstream policing, which involves gathering intelligence, protecting vulnerable targets, and providing immediate assistance in cases of abduction by bandits. These are being demonstrated in the northwest. As an illustration, during October 2021, the police's tactical operatives, acting on valuable intelligence, conducted operations in Gidan Bita, Malakar, and Kagara forest. Their efforts resulted in the apprehension of a notorious bandits' commander and the elimination of five others in a raid carried out in Gummi Local Government Area of Zamfara state (News Agency 2021). Similarly, in December 2021, the police apprehended an individual involved in supplying weapons to bandits in Katsina and Zamfara states (Oyelude 2021). These instances highlight the significance of intelligence-based approaches within the overarching policing model, forming an integral part of a comprehensive system aimed at effectively preventing and combating banditry.

In addition to the police force, the community has also embraced the vigilante model of policing, assuming strategic roles such as repelling attacks, rescuing kidnapped victims, apprehending criminals, and occasionally collaborating with the police and army in joint security operations (Umar 2022). Similar to the Civilian Joint Task Force in Nigeria's northeast, who emerged to combat the Boko Haram insurgents, the vigilantes in the northwest employ primitive weapons like knives, clubs, and locally crafted firearms to confront the bandits, many of whom possess sophisticated rifles. Unfortunately, this places the young vigilantes at a significant disadvantage, exposing them to the risk of severe injuries and even death. However, there have been reports of certain vigilantes engaging in extrajudicial killings that specifically target the Fulani ethnic group, often associated with banditry according to an investigative journalist interviewed in Funtua, Katsina state.Footnote 16 Several of these occurrences have resulted in retaliatory attacks (International Crisis Group 2022; Jamiu 2022).

The federal government has also deployed the joint security to counter armed banditry in the northwest. The foundation of this model lies in the concept of collaboration among different security agencies in Nigeria to effectively address security challenges. This approach is frequently employed to achieve prompt results by combining the military and policing capabilities in security operations. The national security strategy, policy initiatives, presidential directives, military doctrine, and the country's constitution all reflect an increasing understanding of the importance of leveraging interagency partners (such as the armed forces and police) and local communities as fundamental elements in developing a more effective and balanced strategy to tackle urgent security concerns, including banditry. The joint task force model serves as a crisis response strategy specifically designed for limited contingency operations. In response to the growing issue of banditry, the president approved joint military and police operations in June 2020, targeting the states of Niger, Kaduna, Katsina, and Zamfara to eliminate bandits from these areas (Agency Report 2020a, b). The Nigerian security forces have previously responded to such presidential directives by increasing the deployment of military and police personnel to the affected regions. These deployments were carried out under different code names and have yielded varying outcomes (Campbell 2022).

In an operation conducted in March 2022, the joint security task force operating in Niger state successfully eliminated 100 suspected bandits at Bangi village in Mariga local government area (Omonobi 2021). Similarly, in March 2021, security forces in Niger state carried out a 4-day operation that resulted in the killing of over 200 bandits, along with the recovery of numerous motorcycles and cattle (Obiezu 2022). Additionally, in October 2021, the joint security forces, comprising the police and the military, neutralized 32 bandits who were attempting to escape from Zamfara state forests to Niger state (Sahara Reporters 2021). Furthermore, in June 2022, the joint task force consisting of soldiers from Operation Yaki and the Kaduna state police command apprehended four bandits and arrested a female accomplice who was supplying arms to the gunmen (Lere 2022). Despite the successes achieved by the security forces in combating bandit attacks, destroying hideouts, and apprehending or eliminating numerous bandits, the frequency of banditry incidents continues. The persistent nature of this crime highlights the complexity of the crisis and emphasizes the need for the state to devise more effective strategies to combat armed banditry and kidnapping in Nigeria's northwest.

Legislative attempt

Apart from the security and law enforcement strategies, there was a legislative attempt by the Nigerian Senate (the 9th assembly) regarding a bill aimed at criminalizing the payment of ransom to kidnappers, bandits, and terrorists. The bill seeks to amend section 14 of the Terrorism Prevention (Amendment) Act, 2013, with a clause that reads: “anyone who transfers funds, makes payment, or colludes with an abductor, kidnapper, or terrorist to receive any ransom for the release of any person who has been wrongfully confined, imprisoned, or kidnapped is guilty of a felony and is liable on conviction to a term of imprisonment of not less than 15 years.” However, the plausibility of the implementation of such legislative proposal if it becomes a law and the prospects for changing the (in)security landscape in the country for the better hang in the balance for various reasons. The bill fails to address the structural factors driving kidnapping and the criminal economy of ransom payment to the bandits. Second, by attempting to criminalize the payment of ransom by distressed family members of abducted person(s), it speaks to the effect rather than the cause. This becomes pivotal because depriving the families of the victims of kidnapping the only means they have to secure the freedom of their relative(s) leaves them with a zero-sum option which might lead to the death of such persons in the captivity of bandits. More importantly, the bill ignores the fact that government had reportedly paid ransom to bandits in recent time and perhaps continues to do so to secure freedom for some citizens (Editorial 2022).

Negotiation

The negotiation manifests through the payment of ransom to secure the release of abducted persons by bandits. Despite consistent denials from Nigerian federal and state authorities regarding ransom payments to bandits, the reality often contradicts their claims. The Kankara abduction case, involving both schoolboys and bandits, revealed the discrepancy between official statements and reports indicating that the Katsina State government paid ₦30 million (around $76,000) to secure the release of the abducted students (Campbell 2021). On February 26, 2021, about 279 schoolgirls were abducted from the boarding facility of Government Girls Secondary School (GGSS) in Jangebe town, Zamfara State. On March 2, 2021, the bandits released them. The governor of Zamfara state credited the successful negotiation skills of 30 repentant bandits for securing the girls' freedom, firmly denying any payment of ransom. However, contradictory statements from the bandits indicated that N60,000,000 was paid as ransom for the release of the abducted schoolgirls from GGSS. A bandit Warlord confirmed through investigative report that the proceed were used to procure more weapons, and giving credence to assertions that the government has been bankrolling bandits’ operations through ransom payment (Addeh 2020; Akintade 2022). Although ransom payment by state and non-state actors continues in the northwest, this development attracted a tweet from the president of Nigeria.

State Governments must review their policy of rewarding bandits with money and vehicles. Such a policy has the potential to backfire with disastrous consequences. States and local governments must also play their part by being proactive in improving security in and around schools (Buhari 2021).

Therefore, the next section presents strategic recommendations to combat armed banditry and associated kidnapping in Nigeria’s northwest.

Way forward

The rising trend of kidnapping and the subsequent payment of ransoms in the northwest region cannot be addressed without considering the need for a comprehensive reform of the security sector in the country. Therefore, the role of policing is of utmost importance in reversing the chaos and widespread insecurity that plagues society. It is imperative to thoroughly review and amend section 214 of the 1999 constitution, which currently concentrates policing power within the federal government. By implementing a decentralized policing system, a localized and community-oriented approach to law enforcement can be established, allowing communities to actively contribute to the organization, operations, and allocation of human resources in ensuring public safety. Furthermore, the federal government must collaborate with state governments to tackle the immediate challenge of porous borders. By making concerted efforts to recruit, train, and deploy well-equipped security personnel to the borders, surveillance can be strengthened and the influx of illicit arms into the country can be stemmed. The bandits rely on such arms to carry out attacks and abduct innocent civilians. Furthermore, the federal and state governments must also prioritize targeted socioeconomic interventions to ameliorate poverty and lack of opportunities which affect the youths who are being recruited into banditry. The key to resolving these problems lies in making substantial investments in agriculture, infrastructure, education, and other avenues that foster youth employment.

Resolving the security challenge would also require the application of communication technology in security operation. Therefore, the security and intelligence agencies such the Nigeria Police and State Security Service must leverage technology of Sim card- National Identity Number (SIM-NIN) integration to deny bandits of communication flow for planning operations and conducting negotiations. The government must also resource the security agencies with drone technology to enhance real-time awareness of vulnerable communities and highways to enhance rapid incident response initiative and deployment of security forces to hotspots. Durably ending banditry and associated criminal economy of ransom payment in Nigeria’s northwest would require encouraging negotiated settlements between Fulani (herders) and Hausa (sedentary farmers) communities in the rural areas. There various armed groups—Fulani bandits and outlawed Hausa Vigilante must also be disarmed, rehabilitated, and reintegrated into safe spaces within the communities. Concerted efforts to regulate the region’s potentially lucrative gold sector which attracts artisanal miners and enabled terror financing for the armed groups must also be prioritized. Securitization of the forest reserves and other ungoverned spaces that provide refuge for kidnapers and other criminals becomes pivotal as a veritable component of a whole of government and society approach to banditry challenges in Nigeria’s northwest as noted by a farmer in Mashigi, community, Birnin Gwari Local Government Area, Kaduna State.Footnote 17

Conclusion

This article historicizes banditry and kidnapping through global and theoretical perspectives. It identifies the challenges of banditry in Nigeria and discusses kidnapping as a variant of banditry and a criminal enterprise. The article provides emerging evidence on the identities of bandits and assesses the governance responses to the growing trend of kidnapping for ransom by bandits. The article offers direction on the policy imperatives for combatting armed banditry in Nigeria. As Nigeria continues to experience the shocks of banditry, the national and subnational governments, and community members are responding through three distinct strategies of security and law enforcement, negotiation, and legislation. The drawbacks of the responses are also examined. The study argues that the solution to banditry and kidnapping must be multi-pronged. Addressing the rising spate for kidnapping and ransom payment in the northwest cannot be treated independent of the call for broader security sector reform in the country. Strengthening border security and preventing the unregulated entry of firearms into the nation can be accomplished through a concerted effort that focuses on the recruitment, training, and deployment of adequately equipped security personnel. This approach will effectively enhance surveillance capabilities and impede the flow of arms in to the country. Resolving the security challenge would also require the application of communication technology in security operation to deny bandits of communication flow for planning operations and conducting negotiations. Lastly, a peacebuilding approach that fosters negotiated settlements between Fulani herders and Hausa sedentary farmers in the rural areas must be undertaken by state agencies and humanitarian group to establish durable peace in Nigeria’s northwest.

Notes

Interview with a Teacher in Maru Local Government Area, Zamfara State on 14th of May, 2023.

Interview with member of Marke Vigilante Group in Tsafe Local Government Area of Zamfara state.

Interview with a battlefield Bandit in Kagara Town, Rafi Local Government Area, Niger State on February 9, 2023.

Interview with a Member of Vigilante Group in Tagina, Rafi Local Government Area of Niger State on February 9, 2023.

Interview with a custom officer in Jibia, Katisna state on 15th March, 2023.

Interview with a custom officer in Jibia, Katisna state on 15th March, 2023.

Interview conducted with a Custom officer in Illela, Sokoto state on 11th March, 2023.

Interview with a Teacher at Guga community, Bakori, Katsina State on 9th of May, 2023.

Interview in with a Fulani Cattle breeder/Pastoralist in Rini, a town in Bakura LGA in Zamfara state.

Interview with a farmer in Mashigi, community, Birnin Gwari Local Government Area, Kaduna State on February 10, 2023.

Interview with Police officer in Zurmi, Zamfara State on 13th March, 2023.

Interview with a Cattle breeder/Pastoralist in Mariga town, Bangi Local Government Area, Niger state on February 8, 2023.

Interview with Fulani Leader belonging to Kautal Hore, Bakura Local Government Area Branch, Dakku, Zamfara State on February 16, 2023.

Interview with a male teacher of Islamic Religious Studies at Nasarawa Mai-Layi, Birnin-Magaji, Zamfara State on Date: 13th May, 2023.

Interview with a senior official of community school in Gatakawa, Kankara, Katsina State on 10th of May, 2023.

Interview conducted with a Funtua based Journalist on 10 August 2022 in Katsina State.

Interview with a farmer in Mashigi, community, Birnin Gwari Local Government Area, Kaduna State on February 10, 2023.

References

Abdulaziz, A. 2021. Investigation: Boko haram, others in mass recruitment of bandits. https://dailytrust.com/boko-haram-others-in-mass-recruitment-of-bandits. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Abdullateef, I. 2022. DSS: Military equipment, large amounts in different currencies found in Mamu’s house, office. https://www.thecable.ng/dss-military-equipment-large-amounts-in-different-currencies-found-in-mamus-house-office. Accessed 26 Aug 2022.

Addeh, E. 2020. Report: Despite FG’s Denial, Freed Katsina Schoolboys Say Ransom Was Paid. https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2020/12/24/report-despite-fgs-denial-freed-katsina-schoolboys-say-ransom-was-paid/. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Adeyemi, I. 2022. Unpunished crimes, poverty, others fuel banditry in Nigeria’s northwest —report https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/521768-unpunished-crimes-poverty-others-fuel-banditry-in-nigerias-northwest-report.html. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

Agency Report. 2020a. Buhari approves joint military, police operations against bandits in north–west. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/regional/nwest/398035-buhari-approves-joint-military-police-operations-against-bandits-in-north-west.html. Accessed 10 Aug 2022.

Agency Report. 2020b. Banditry in Nigeria has international dimension—IGP (August 2020).https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/more-news/409875-banditry-in-nigeria-has-international-dimension-igp.html. Accessed 10 Aug 2022.

Alemika, E. 2013. The Impact of Organised Crime on Governance in West Africa, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/nigeria/10199.pdf. Accessed 22 Aug 2022.

Akintade, A. 2022. We used N60 million ransom to buy more weapons: Zamfara Bandits. https://gazettengr.com/we-used-n60-million-ransom-to-buy-more-weapons-zamfara-bandits/. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Auwal, A. 2021. How banditry started in Zamfara. https://dailytrust.com/how-banditry-started-in-zamfara. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Buhari, M. 2021. Tweet https://twitter.com/mbuhari/status/1365382428777406467?s=21. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Babangida, M. 2022. Bandits release Katsina village head, 35 others after N26 million ransom. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/regional/nwest/515921-bandits-release-katsina-village-head-35-others-after-n26-million-ransom.html. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Barlow, H. 1995. Crime and Public Policy: Putting Theory to Work.Westview Press. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/3074144. Accessed 20 Aug 2022.

Campana, P., and F. Varese. 2020. The determinants of group membership in organized crime in the UK: A network study. Global Crime 23 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2022.2042261.

Campbell, J. 2021. Kidnapping and Ransom Payments in Nigeria. https://www.cfr.org/blog/kidnapping-and-ransom-payments-nigeria. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Campbell, J., and N. Quinn. 2021. Multiple Jihadi Insurgencies, Cooperating with Bandits, Appear to be Converging in the Sahel. https://www.cfr.org/blog/multiple-jihadi-insurgencies-cooperating-bandits-appear-be-converging-sahel. Accessed 10 Aug 2022.

Carrington, K., R. Hogg, and M.E. Sozzo. 2015. Southern criminology. British Journal of Criminology 56: 1–20.

Ceccato, V., and J. Abraham. 2022. Reasons why crime and safety in rural areas matter. In Crime and Safety in the Rural. Springer Briefs in Criminology. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98290-4_2.

Channels Tv. 2021. Zamfara Govt Paid Almost ₦1bn In Ransom to Bandits—Commissioner. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hOP-lqOhXhs. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Chiricos, T., K. Padgett, and M. Gertz. 2000. Fear, TV news, and the reality of crime. Criminology 46: 755–785.

Chukwuemeka, E. 2022. Poorest States in Nigeria 2022: Top 13. https://bscholarly.com/poorest-states-in-nigeria-2022-top-13/. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

Control Risks. 2022. Kidnap for Ransom in 2022. https://www.controlrisks.com/our-thinking/insights/kidnap-for-ransom-in-2022. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Clunan, A.L., and H.A. Trinkunas. 2010. Ungoverned Spaces: Alternatives to State Authority in an Era of Softened Sovereignty. Stanford: Stanford Security Studies.

Creveld, M. 1991. On future war, Chrysalis Books, January 1, 1991. London.

Daily Trust. 2019. How kidnapping is making families poorer. https://dailytrust.com/how-kidnapping-is-making-families-poorer. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

De Lazari, A. n.d. Banditry and Its Liquidation 1920–1922. https://www.loc.gov/rr/geogmap/pdf/ruscw/map10.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Editorial. 2022. Senate’s criminalisation of ransom payment. https://tribuneonlineng.com/senates-criminalisation-of-ransom-payment/. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Eschholz, S., T. Chiricos, and M. Gertz. 2003. Television and fear of crime: Program types, audience traits, and the mediating effect of perceived neighborhood racial composition. Social Problems 50 (3): 395–415.

Faison, S. 2016. The Social Contract: A License to Steal, Stephen Faison cross-examines the idea of a social contract, Visions of Society. https://philosophynow.org/issues/116/The_Social_Contract_A_License_to_Steal. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Ferraro, K.F., and R.L. LaGrange. 1987. The measurement of fear of crime. Sociological Inquiry 57: 70–101.

Ferraro, K.F. 1995. Fear of Crime: Interpreting Victimization Risk. New York: SUNY Press.

Ferguson, K.M., and C.H. Mindel. 2007. Modeling fear of crime in Dallas neighborhoods: A test of social capital theory. Crime and Delinquency 53 (2): 322–349.

Fominyen, G. 2020. Five things to know about spiralling insecurity in the Sahel. https://www.wfp.org/stories/five-things-know-about-spiralling-insecurity-sahel. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Goodluck Jonathan Foundation. 2021. Terrorism and Banditry in Nigeria: The Nexus. https://www.gejfoundation.org/terrorism-and-banditry/. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

Global Terrorism Index. 2022. Sahel has become the new epicentre of terrorism. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/sahel-emerges-as-the-new-epicentre-of-terrorism/. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Hastings, J. 2012. Understanding maritime piracy syndicate operations. Security Studies 21 (4): 683–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2012.734234.

Hightower, R., W. Bonger, and A. Turk. 1970. Criminality and economic conditions. American Sociological Review 35 (3): 601. https://doi.org/10.2307/2093062.

Hobsbawm, E. 2000. Bandits. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Ibrahim, J. 2021. Kidnapping for Ransom: Can Nigerians Survive the Third Wave?. https://dailytrust.com/kidnapping-for-ransom-can-nigerians-survive-the-third-wave. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

International Crisis Group. 2020. Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem, Report 288. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/288-violence-nigerias-north-west-rolling-back-mayhem. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

International Crisis Group. 2022. Managing Vigilantism in Nigeria: A Near-term Necessity, Report 308. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/308-managing-vigilantism-nigeria-near-term-necessity. Accessed 20 Aug 2022.

Jamiu, A. 2022. The teenagers fighting Nigeria’s ‘bandits’ with knives and clubs. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2022/4/25/the-teenagers-fighting-nigerias-bandits-with-knives-and-clubs. Accessed 22 Aug 2022.

Jeanneney, S. 2016. Linking Security and Development: A Plea for the Sahel. https://ferdi.fr/dl/df-mmi8mZkJuCtTRxgA6Lu7wmDX/linking-security-and-development-a-plea-for-the-sahel.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Jerry, R. 2019. Bandits are Recruiting Youths in Katsina State by Given Them N5,000 And Drugs Governor Masari. https://ng.opera.news/ng/en/military/1398896f4457da54f5add748046d4297. Accessed 10 Aug. 2022.

Kaldor, M. 2013. In defence of new wars. Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 2 (1): 4. https://doi.org/10.5334/sta.at.

Katz, C.M., V.J. Webb, and T.A. Armstrong. 2003. Fear of gangs: A test of alternative theoretical models. Justice Quarterly 20 (1): 95–130.

Koné, H. 2022. Organised banditry is destroying livelihoods in Niger’s borderlands. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/organised-banditry-is-destroying-livelihoods-in-nigers-borderlands. Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

LaGrange, R.L., K.F. Ferraro, and M. Supancic. 1992. Perceived risk and fear of crime: Role of social and physical incivilities. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 29: 311–334.

Lere, M. 2022. Security operatives kill four bandits, arrest accomplice in Kaduna. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/regional/nwest/537501-security-operatives-kill-four-bandits-arrest-accomplice-in-kaduna.html. Accessed 22 Aug 2022.