Abstract

In February 2012, George Zimmerman, a Hispanic man, shot and killed Trayvon Martin, an African-American teen, after encountering Martin walking in a hoodie in the rain in his neighborhood. A media frenzy followed, focusing on the racial differences between the two and the possible injustice of the incident. A key legal and public question was whether Zimmerman was acting in self-defense or based on racial stereotypes. Based in the fear of crime and racial socialization literature, this study examines the impacts of racial socialization, fear of crime, and subcultural diversity on university students’ expected reactions to an incident very similar to the Zimmerman–Martin encounter. We find that the race of the person encountered is not a significant predictor of how these university students expected to respond. In addition, while fear of crime and subcultural diversity also fail to reach significance, promotion of mistrust of other races is related in this sample to willingness to pull a gun and shoot one. Given the policy and public significance of behavioral reactions to crime, we call for much more research before making conclusions about the impact of racial differences and mistrust on how people might react in potentially threatening situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

On February 26, 2012, George Zimmerman, a 28-year-old, Hispanic neighborhood watch member spotted a “suspicious” young black man who he thought was “up to no good” in his neighborhood. He called police. The dispatcher said they were on their way and asked Zimmerman not to follow the person. The young man walking with a sweatshirt hood over his head to shield himself from the rain was 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, who was returning to a family friend’s home after walking to a local 7–11 to get snacks. Zimmerman followed him, they exchanged blows, and Zimmerman shot unarmed Martin in the chest, killing him. Zimmerman claimed self-defense when the police arrived (Botelho 2012; Serino 2012), and throughout the trial where he was eventually acquitted of second-degree murder (Alvarez 2013). There apparently were no witnesses who saw the entire skirmish from beginning to end or who saw the actual shooting (Alvarez 2013).

After both this incident and acquittal occurred, commentators, the mass media, and people in the public spent a great deal of time debating what really happened and whether Zimmerman was really defending himself or was a racist who profiled a young black man as criminal and wrongly killed an innocent teenager (see Carlson 2016; Mullen 2015; O’Connor 2015). George Zimmerman’s shooting of Trayvon Martin is fraught with elements relevant to the work of fear of crime researchers. One core issue in this case was whether Zimmerman was really afraid for his life and acted in self-defense. Another primary element that many commentators and the public focused on was the racial/ethnic differences between the two men—that is, was Zimmerman reacting not based on any real problem from Martin, but rather on his own biases about black people—was he racially profiling? The “subcultural diversity” or racial heterogeneity approach to explaining fear of crime focuses specifically on perceived racial and ethnic differences as a factor that increases fear. The argument is that people are afraid of others who look different because they do not understand the other person’s behaviors and mannerisms (see Merry 1981). Specifically, it could have been that Zimmerman was afraid of Martin, simply because he looked and acted differently than Zimmerman was accustomed to seeing among people he knew (e.g., wearing a “hoody” sweatshirt, walking through the neighborhood with his head down, or simply carrying himself in a different manner).

Psychologists have studied the impact of racial socialization on people’s attitudes and behaviors, and one of their ideas is that some people are socialized to mistrust people of other races/ethnicities and to be more alert around them (Hughes and Chen 1997; see also Bentley et al. 2008; Priest et al. 2014; Yasui 2015). In other words, this might be one explanation for the importance of the subcultural diversity argument in explaining fear of crime. If this were true for Zimmerman—if he was socialized to mistrust other groups and if he did not understand Martin’s mannerisms and behaviors, leading to fear of Martin—it might partly explain his shooting of the teen.

No one else can know what Zimmerman was really thinking or why he followed Martin, even if they listen to his words in interviews or testimony. He may or may not have told the truth about what he was thinking or his biases may have been implicit (see Greenwald and Krieger 2006, for a review), yet the impact of fear of crime and racial socialization can be examined more broadly by asking others how they might respond in a similar situation to the Zimmerman–Martin case. Situated in fear of crime theory and psychological research on racial socialization, this article examines these two issues by reporting the results of a survey designed to ask undergraduates in the state of Florida, where the Zimmerman–Martin case occurred, what they thought they would do if faced with a situation similar to the one faced by Zimmerman. Specifically, we focus on three research questions for this undergraduate student sample. First, do fear of crime and racial socialization, especially parental promotion of mistrust of other races, predict one’s willingness to choose a violent reaction in a situation similar to the Trayvon Martin–George Zimmerman case? Second, are men in this sample more likely than women to say they would respond with violence? Finally, does the race/ethnicity of the “suspicious” person encountered affect the likelihood of saying one would choose violence? While results from a convenience sample of undergraduates may not generalize to the population at large, this study was a first step toward exploring some important issues raised by the Zimmerman case for fear of crime research.

Gender, race, and fear of crime

Research on fear of crime in recent years has focused on both the possible causes and consequences of fear. Many studies have concentrated on what personal and theoretical factors might predict fear of crime among individuals. In terms of demographic characteristics, both gender and race of the individual, topics discussed in this paper, matter. One of the most consistent and compelling findings in the research over time is the almost universal result that women are more afraid of victimization than men are, despite their generally lower risk of victimization by street crime. In the fear of crime literature, there are generally four theoretical approaches to understanding women’s greater fear of crime: physical vulnerability (women are generally actually physically weaker and feel more vulnerable to possible harm if victimized) (e.g., Skogan and Maxfield 1981), perceived threat of rape (women worry that any type of victimization might actually lead to rape) (e.g., Ferraro 1996; Warr 1984), patriarchy (women’s lived experiences with gender inequality rightly lead to fear of victimization) (e.g., Stanko 1985), and socialization (women are more likely than men to be socialized to believe they are weaker than men and cannot fend off an attacker) (e.g., Hollander 2001) (see Lane 2013; Lane et al. 2014, for a review). It is this latter socialization argument that prompted the idea for the current research. Specifically, if socialization is considered to be an important component of women’s fear of crime, it is logical that socialization might also play an important part in explaining differential fear among other groups, especially racial and ethnic groups. Yet, fear of crime literature has yet to focus much attention on this possibility.

Over time, many studies have found that non-Whites are more afraid than Whites are (e.g., Baumer 1978; Ferraro 1995, 1996; Lane and Meeker 2003; Skogan 1995; Skogan and Maxfield 1981; Warr 1984; cf. Gainey et al. 2011; for a summary, see Lane et al. 2014). Consequently, some studies have also examined the reasons for greater fear among minorities (see Lane et al. 2014, for a review). First, racial and ethnic minorities statistically are more likely to live in areas plagued by crime (De la Roca et al. 2014; Friedson and Sharkey 2015). Second, minorities, particularly African-Americans, are statistically more likely than Whites are to be victimized (Truman and Morgan 2016). Taken together, these factors make racial and ethnic minorities more socially vulnerable to victimization and therefore, scholars argue, it makes logical sense that they would feel more fear of crime (e.g., Ferraro 1995; Parker 1988; Parker and Ray 1990; Skogan and Maxfield 1981; see also Lane et al. 2014).

As mentioned above, another theoretical argument for different levels of fear of crime across races lies in the subcultural diversity perspective, which notes that people who have language and cultural differences but come into contact may fear each other because they do not understand the differences (Merry 1981). For example, people who are new to the US may be afraid for their safety if they do not speak English well and do not feel they can navigate their social environment effectively (e.g., Lee and Ulmer 2000). Moreover, long-term residents may be afraid of newer residents who speak an unfamiliar language and whose behaviors are not familiar (see Lane 2002; Merry 1981). Another possibility put forth more recently is the possibility that racial socialization may play a factor in fear differences among racial and ethnic groups. For example, Lane and Fox (2012) noted that just as parents might socialize their daughters more often to be careful, minority groups may be more likely to socialize their children of color to be more aware of crime, as a way of protecting them from harm. It is possible that one of the reasons that subcultural diversity might matter in predicting fear of crime is that people have been socialized as children to believe that they should fear people who are different, racially, ethnically, or culturally.

Racial socialization and promotion of mistrust research

Recently, Hagerman (2018, p. 142), a sociologist, discussed how parents of white children talk to them about race, finding that “In some cases, these family conversations attempt to interrupt racism, while in others they attempt to reinforce racial stereotypes and myths.” For example, some parents mock the names of black youths or call their parents lazy, while others reprimand their kids for saying racist things or mentioning racial differences. Yet, most studies on racial socialization by parents appear in the psychological literature and primarily discuss the process in African-American families (see Priest et al. 2014, for a review). Although there is no standard definition of this construct, the focus of this literature generally has been to examine the messages that black children receive as parents strive to teach them about their culture, about relating to other racial and ethnic groups, and to “cope with their oppressed minority status” (Lesane-Brown 2006, p. 401). The latter is more likely to occur, for example, when families live in more racially mixed areas and when parents believe that their children have been treated unfairly (see Hughes and Johnson 2001; Lesane-Brown 2006; Thornton et al. 1990). Parents share these types of messages to help their children adapt to and negotiate their experiences in the outside world (Rollins and Hunter 2013).

The psychological literature argues that parents specifically share messages about race and ethnicity in four ways—through cultural socialization, preparation for bias, egalitarianism and promotion of mistrust (Hughes and Chen 1997; Priest et al. 2014). Messages about cultural socialization and preparation for bias are given to children to increase their cultural pride and teach them how to cope with discrimination (Hughes et al. 2006), while egalitarianism messages focus on commonalities and shared experiences across groups rather than differences (Priest et al. 2014). These socialization practices are meant to have and often result in positive emotional and behavioral outcomes, such as more knowledge of group history and traditions, group pride, higher social competence, better self-esteem, a better developed racial identity, better social functioning and academic efficacy and performance and fewer internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (Coard and Sellers 2005; Caughy et al. 2002; Evans et al. 2012; Hughes et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2003); although some research shows that preparation for bias can cause behavioral problems, especially among girls (Caughy et al. 2006). Some have argued that the effects of these messages may be dependent on the age of the child or the type of neighborhood in which one lives (see Caughy et al. 2006).

In contrast to the others, promotion of mistrust messages, which appear to be less common and are the subject of fewer studies, teach children to be suspicious of and more alert around other racial groups, sometimes focusing on awareness of discrimination (Hughes and Chen 1997; Priest et al. 2014). We expect that these types of messages are the ones most likely to lead to the theoretical concept in the fear literature called “subcultural diversity,” or a misunderstanding of the behaviors and mannerisms of people who look different, eventually leading to fear of crime (see Merry 1981). There is not much literature specifically focused on the effects of promotion of mistrust. Most research has found that promotion of mistrust messages are associated with negative outcomes for children, including depression, deviance, and lower social competence (Granberg et al. 2012; Hughes et al. 2006). These studies overwhelmingly focus on African-American families and show that youths who receive racial mistrust messages are more likely to engage in deviant behavior, commit crime, react aggressively toward others, and have poorer school performance (Caughy et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2003; Taylor et al. 1994; Biafora et al. 1993). In addition, when youths were given messages to be cautious around Whites, they were more likely to feel closer to Blacks and support black separatism (Demo and Hughes 1990). Results also show that racial socialization can increase acculturative stress, or discomfort when dealing with Whites (see Thompson et al. 2000).

Only a few studies have examined the effects of promotion of mistrust on people of other races and cultures. One study found that among Asian Americans more promotion of mistrust messages were related to fewer positive feelings toward social interactions and one’s own social abilities (Tran and Lee 2010). Another found that they were related to lower academic achievement among Chinese, Hispanics, and Whites (Huynh and Fuligni 2008). Still another examined a combined sample of African-American, Asian and Latino college students, finding that promotion of mistrust was related to depression, in part because it increased pessimism (Liu and Lau 2013). Interestingly, although fear of crime researchers have focused on the impact of gender socialization on fear of crime among women and men (e.g., see Goodey 1997; Hollander 2001), they have basically ignored the possible impacts of racial socialization on fear or precautionary behaviors. Although we do not have the data to determine if racial socialization, especially promotion of mistrust, leads specifically to concerns about subcultural diversity, we contend that it may be an important precursor that could help explain concerns about subcultural diversity and subsequently fear and possibly reactions, such as gun carrying, that could make problems worse rather than better. This paper is just a first step in exploring the connection between promotion of mistrust messages, subcultural diversity, fear, and possible behavioral responses to a real threat situation.

Subcultural diversity as a predictor of fear of crime and reactions to it

Fear of crime researchers who have examined the impact of concerns about race have done so within the broader framework of social disorganization theory. Social disorganization is a macro-level theory that primarily concentrates on the impact of neighborhood factors such as low socioeconomic status, residential mobility and racial heterogeneity on local crime levels, but it can also help researchers understand differing fear levels across neighborhoods (macro-level) and people (micro-level) (see Bursik and Grasmick 1993; Liska et al. 1982; Sampson and Groves 1989; Shaw and McKay 1942). Fear researchers have generally focused on how macro-level social disorganization factors can translate into micro-level (or individual) causes of fear through perceptions. One of the important factors in the social disorganization tradition is racial heterogeneity, or differences in races and ethnicities among people living in an area. A key theoretical model explaining fear, as mentioned above, is the subcultural diversity argument, which posits that living near people of different racial, ethnic, or cultural backgrounds produces fear because people interpret others’ actions “through the lens of their own culture” (Merry 1981, p. 149). Research on the subcultural diversity argument has shown that it predicts fear of crime generally and fear of specific perpetrators (e.g., gangs) (see Covington and Taylor 1991; Lane 2002; Lane and Meeker 2000, 2003). One study found that racial prejudice among Whites led to more fear when they encountered a Black stranger compared to those who were not prejudiced, while both groups were more afraid of a Black person than a White one (St. John and Heald-Moore 1996). That is, both racial/ethnic differences (subcultural diversity) and mistrust or prejudice matter in predicting fear, but research has not yet studied their impacts on behavioral precautions in response to fear.Footnote 1 This study does.

Fear of crime leads to constrained behaviors, but only sometimes gun carrying

Fear of crime researchers have found that people who are afraid often engage in precautionary behaviors to prevent victimization, and these are often termed “constrained behaviors” (Lane et al. 2014). Some argue that fear of crime and constrained behaviors can have reciprocal effects, meaning that people who are afraid may engage in more precautionary behaviors, which in turn makes them more afraid; yet, there is little research to date to confirm these arguments (see Liska et al. 1988; Henson and Reyns 2015 for a review). Still, Rader and Haynes (2014) did find that people who reported using avoidance behaviors—such as avoiding areas or limiting daily activities–were more worried about crime, while people who engaged in other constrained behaviors, including carrying weapons, were not. This section first discusses gun ownership and carrying as it relates to fear of crime, because of its centrality to the Zimmerman case and this paper more generally, and then discusses other behavioral precautions, many of which the research shows are more common responses to fear (see Lane et al. 2014).

Statistics regarding constrained behaviors

One behavioral response to fear is carrying a gun for protection, like George Zimmerman did, and Gallup finds that very few people do so (Carroll 2007). Before one can carry a gun, though, one must own (or have) one. A recent study found that about 1/3 of Floridians (32.5%) own a gun, compared to a slightly lower percentage of gun owners nationwide (29.1%). Yet, many fewer Floridians own guns compared to some other Southern states (e.g., 57.9% of residents of Arkansas reported owning a gun) (Kalesan et al. 2016; see also “Owning Guns” 2013). Results from the General Social Survey (GSS) show similar numbers of people nationally living in households with a gun (about 34%) (Smith et al. 2014). Generally, men are more likely to personally own a gun than women are, and Republicans are more likely than Independents and especially Democrats to own a gun. Older people are also more likely than younger people to own a gun (Kalesan et al. 2016; Yuan and McNeeley 2016 see also “Owning Guns,” 2013). Yet, GSS results show that since the 1970s, gun ownership has declined a great deal overall (Smith et al. 2014).

Having a gun in the household, however, is different than carrying one outside the home. Gun carrying is more common in the South, which technically includes Florida, and West, than other regions of the country (Felson and Pare 2010). Florida is a “shall issue” state, meaning that people who request a concealed gun carry permit must be given one as long as they meet the criteria in the law (US Government Accountability Office 2012), although Florida currently does not allow guns to be carried openly (Open carrying of weapons, Florida Statute 790.053). As of May 2017, there were over 1.7 million concealed carry gun permits in Florida, and about 3/4 of them were issued to males (Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services 2017a, b).

It is not clear how many gun owners carry for protection. According to a special Gallup poll, only about 12% of people nationally carry guns for protection, while about a quarter indicate that they bought a gun for protection (23%) (Carroll 2007). A 2013 poll by the Pew Research Center, in contrast, found that among gun owners, 48% at least said they owned a gun for protection (Drake 2014). Gallup finds that most people do not buy or carry guns or other weapons to protect themselves from crime. Rather, they are more likely to avoid certain areas of their communities (48%) or do something such as get a dog for protection (31%) or install an alarm system in their homes (31%). Women (54%) are more likely than men (41%) to say they avoid places, while men are more likely to indicate they bought a gun for protection (32% vs. 15%) or carried a gun (17% vs. 6%) or knife (16% vs. 9%) for self-defense (Carroll 2007). A more recent Gallup poll found that men, people in the South, married people, Whites, older people, and political conservatives (including Republicans) are more likely to own guns (Jones 2013).

Scholarly research on constrained behaviors

Scholarly research confirms poll results. The most common approach to preventing personal victimization is avoiding unsafe areas, especially at night, as well as adding locks or lighting to one’s home. Gun carrying is a less common prevention measure (see Ferraro 1995; Lane 2009; Lane and Meeker 2004; Wilcox et al. 2006). Studies show that men are more likely than women to carry guns (e.g., see Bankston et al. 1990; Cobbina et al. 2008; Felson and Pare 2010; Ferraro 1995; Lane 2009; Luxenburg et al. 1994),Footnote 2 and males and non-whites are more willing to shoot someone they believe is a criminal (Cao et al. 2002). Generally, then, men are more likely than women to do proactive, defensive behaviors that may eventually lead to more crime or violence. Some research shows that older people and minorities are more likely to own guns for protection (Lizotte et al. 1981), while others show that younger people are (Carroll 2007; Luxenburg et al. 1994).

Some research focusing specifically on gun ownership is equivocal on whether fear of crime leads to owning or carrying guns (Arthur 1992; DeFronzo 1979; Smith and Uchida 1988; Young 1985), while other studies find that fear of crime predicts gun carrying. For example, some studies show that fearful males are more likely to carry guns than men who are not afraid (Hill et al. 1985), and this is true for adult male offenders (Watkins et al. 2008). Still another study found that fear for personal safety was a significant predictor of gun carrying for both men and women (Felson and Pare 2010). Perceived risk of crime also predicts gun carrying (Smith and Uchida 1988). A more recent study on a number of behavioral precautions, however, found that neither perceived risk nor fear of crime predicted gun ownership (Yuan and McNeeley 2016).

There are fewer studies that examine race differences in constrained behaviors, and findings are inconsistent, suggesting the need for more research. Madriz (1997) noted that white women were more likely than women of color to avoid places during darkness or when they were alone. Hibdon et al. (2016) also found that white college students in residential housing were more likely than non-white ones to engage in avoidance behaviors. Yet another study found that Whites were more likely than non-Whites to have a burglar alarm but not to have extra locks or leave on extra lights or own a weapon (Yuan and McNeeley 2016). In contrast, Lane and Meeker (2004) found that Hispanic respondents were significantly more likely than Whites to engage in avoidance behaviors while there were no significant differences among Whites, Hispanics, and Vietnamese in terms of arming behaviors. Yet, Rader et al. (2007) found no race effect in predicting avoidance (i.e., not doing activities they would like to do) or defensive behaviors (doing things to protect their home). We are aware of no studies that focus specifically on how perceptions of racial diversity affect gun carrying.

Method

Study context and recruitment

For this exploratory study, we collected data during the 2013 spring semester at the University of Florida, a school that is situated in the heart of the state where the Trayvon Martin shooting and subsequent trial and acquittal of George Zimmerman occurred. We recruited participants using a convenience sample from the Department of Sociology and Criminology & Law’s participant pool. Undergraduate students in some criminology courses were required each semester to participate in the participant pool (or choose to do an alternative assignment), and others were allowed to participate as an extra credit option. Students generally could choose among many research projects to fulfill their course requirements. Because some of the participating classes were considered “general education” courses at the university and fit within a group of social science classes that any student could take to meet university requirements, students in the pool were not necessarily criminology majors. While the results of this study may not generalize beyond this sample, this was a first step to examine the possible effects of racial socialization on possible reactions to “suspicious” people.

Design and variables

This study uses survey data that examines what actions respondents would consider doing should they be faced with a situation similar to the Zimmerman–Martin interaction, using a 2 × 3 factorial design, varying the gender (male or female) and race (white, black or Hispanic) of the suspicious person. Participants in this study took an anonymous online survey through www.qualtrics.com and answered questions about their personal characteristics, racial socialization, concerns about subcultural diversity, and fear of crime. Then, each participant read a hypothetical situation, which was very similar to the Trayvon Martin case but varied the race and gender of the “suspicious person.” The Qualtrics software randomly assigned scenarios to participants. After they read the scenario, participants then answered related questions about how they would consider reacting in that particular situation to protect themselves, and then answered additional questions not analyzed here.

Independent variables

Racial socialization

Informed by the psychological literature, we measured racial socialization using three scale measures, designed to capture cultural socialization, preparation for bias, and promotion of mistrust (Hughes and Chen 1997; Hughes and Johnson 2001). The stem question asked, “I would like you to indicate how often your parents engaged in the following behaviors when you were growing up.” This was followed by 15 behaviors related to racial socialization. Response options included: never (1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), and often (4).

A principal component factor analysis using Varimax rotation of the racial socialization items revealed three constructs (Eigenvalues greater than 1.0), and the included items were used to create three racial socialization scales: cultural socialization (7 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.89), preparation for bias (6 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.88), and promotion of mistrust (2 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.92). The cultural socialization measure used here consisted of the following behaviors (factor loadings in parentheses): talked to you about important people or events in the history of different racial or ethnic groups other than your own (0.82), encouraged you to read books about other racial or ethnic groups (0.79), talked to you about important people or events in your racial or ethnic group’s history (0.72), talked to you about discrimination against a racial or ethnic group that is not your own (0.79), explained something on TV that showed discrimination (0.74), encouraged you to read books about your own racial or ethnic group (0.63), and did or said things to show that all are equal regardless of race or ethnicity (0.67). Preparation for bias scale items included: talked about discrimination against your own racial or ethnic group (0.75), talked about others trying to limit you because of your race or ethnicity (0.83), told you that you must be better to get the same rewards because of your race or ethnicity (0.80), told you your race or ethnicity is an important part of self (0.66), talked to someone else about discrimination when you could hear (0.52), and talked to you about unfair treatment due to your race or ethnicity (0.82). Promotion of mistrust scale items included: did or said things to keep you from trusting kids of other races or ethnicities (0.92) and did or said things to encourage you to keep your distance from people of other races or ethnicities (0.94).

Fear of crime

We measured fear of crime using two constructs—fear of property crime and fear of violent crime (Lane and Meeker 2003; Lane 2006, 2009). The stem question read: “I would like to ask you about how personally afraid you are of the following crimes. For each of the following crimes, please indicate if you are not afraid (coded 1), somewhat afraid, afraid, or very afraid (coded 4). In the past year how personally afraid have you been of:”.

A principal component factor analysis using Varimax rotation of the fear of crime items revealed two constructs (two Eigenvalues greater than 1.0; factor loadings in parentheses after each item). We used these two constructs to create two fear of crime scales: fear of property crime (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.89) and fear of violent crime (10 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.97). The fear of property crime scale included: having your car stolen (0.66), having your property damaged (0.76), having your property damaged by graffiti or tagging (0.83), having someone break into your home while you are away (0.74), and having your money or property taken from you without using force or a weapon (0.68). The fear of violent (or personal) crime scale included: having someone break into your home while you are there (0.70), being raped or sexually assaulted (0.80), being murdered (0.89), being attacked by someone with a weapon (0.84), being robbed or mugged on the street (0.75), being shot at while walking down the street (0.85), being shot at with a concealed weapon (0.86), being the victim of a drive-by or random shooting (0.84), being physically assaulted or attacked by someone (0.84), and having your money or property taken from you with force or a weapon (0.73).

Subcultural diversity

The stem for the subcultural diversity construct read, “with regard to the neighborhood that you consider to be your home neighborhood please indicate whether or not the following problems characterize your neighborhood. Please indicate if the following items are a big problem (4), a problem (3), somewhat of a problem (2), or not a problem (1).” A principal components factor analysis of the subcultural diversity items revealed one construct (one Eigenvalue greater than 1.0; factor loadings in parentheses). We used this set of questions to create a subcultural diversity scale (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.79). The scale included: language differences between residents (0.83), cultural differences between residents (0.89), and racial differences between residents (0.81) (see Lane and Meeker 2003, 2004).

We also included personal characteristics of the respondents (sex, age, race, and political orientation) as control variables in the multivariate models when they were significantly associated with the dependent variables at the bivariate level. We coded sex so that 1 = female and 0 = male, because research on fear of crime shows that women are consistently more afraid of crime than men are (Ferraro 1996; McGarrell et al. 1997; May et al. 2010; Schafer et al. 2006; Warr 2000). We measured political orientation on a scale from very liberal (1) to very conservative (5). Age was a continuous variable. For race, we included the individual racial and ethnic identities in the descriptive statistics table for informative purposes, but recoded them into White (coded 1) and non-White (coded 0) for the analysis due to small numbers in some racial/ethnic categories.

Conditions

Participants were assigned to read one of six hypothetical scenario conditions. The conditions varied by two levels of the gender of the suspect (male and female) and three levels of the race of the suspect (White, Black, and Hispanic). Therefore, there were six conditions total (White male, White female, Black male, Black female, Hispanic male, and Hispanic female). The following is an example of the scenario (underlined words changed based on condition).

It is about 7:00 P.M., dark, and raining. You are returning home in your car from a personal errand and see a suspicious man walking around in your neighborhood. The man looks like he is up to no good and may be on drugs. You’ve had a string of break-ins in your neighborhood, so you are alerted to it because he is walking around the area staring at all the houses. The man is white, in his late teens, and wearing a sweatshirt, pants, and tennis shoes. You put a call into the police to get an officer over to the area. When you are on the phone with the police dispatcher, the man begins to run toward the back entrance of your neighborhood. The dispatcher tells you not to follow him and there is an officer on the way. However, you get out of your car and follow the man so he does not get away before the police get there. You confront the man and a struggle ensues.

Dependent variables

Reactions

After they read the scenario varying the race and gender of the suspicious person, participants answered the following question, “In order to protect yourself during the fight described in the previous situation you read, what would you consider doing?” The answer options were: scream for help, run away, fight back, pull a gun, pull a weapon other than a gun, shoot at them with a gun, and use a weapon other than a gun. These items constitute the dependent variables in the study. For each answer option, the respondents could indicate yes, no, or don’t know. We dummy coded each variable, so that yes equals 1 and no equals 0. We coded people who indicated “don’t know” as missing.

Analysis

Our first research question asked whether fear of crime and racial socialization messages—especially promotion of mistrust—predicted one’s propensity to choose a violent reaction in a situation similar to the George Zimmerman–Trayvon Martin case. To assess this question, we ran descriptive and bivariate analyses to determine distributions and associations between personal characteristics, racial socialization, fear of crime, and reactions to the scenario. Next, we ran multiple logistic regression models to determine which of those independent variables that were correlated at the bivariate level predicted people’s choice of reactions to this potentially scary situation (e.g., whether they would consider screaming, running, fighting, pulling a gun, or shooting the person). Predictor variables included in the models are fear of crime, racial socialization, subcultural diversity, and personal characteristics. Our initial goal was to include demographics and promotion of mistrust first, then add subcultural diversity, and then add fear of crime to the models. This would have allowed us to examine and compare the effects of subcultural diversity and fear of crime, after controlling for racial socialization. However, because some of these variables were not correlated with expected reactions at the bivariate level, it generally did not make sense to include them in the multivariate equations.

Our second research question asked if men were more prone to choose a violent reaction, and so we pay particular attention to these findings. Our final research question asked whether the race of the suspicious person (e.g., white, black or Hispanic) would affect expected reactions, particularly use of violence.

Results

We first report descriptive statistics for the sample, including their demographic characteristics and their responses to the predictor variables of interest. We then present the bivariate analysis, showing the relationships between the independent variables and the expected reactions to the hypothetical situation similar to the Zimmerman–Martin case. Finally, we present the multivariate logistic regression analysis for each of the expected reactions in which there was more than one significant independent variable correlated at the bivariate level.

Descriptive statistics

The sample consists of 386 undergraduate students (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics). The majority of the sample is female (65.8%) and White (57.0%). About 16% were Black, 18% were Hispanic, and 9% were “others.” Ages ranged from 18 to 39, but most were young (mean = 20.38 years old). In terms of political orientation, 4.1% of the sample indicated they were very liberal, 30.2% were liberal, 34.1% were middle of the road, 26.1% were conservative, and 5.5% were very conservative. The mean (2.99) indicates that as a group they were more “middle of the road” on politics rather than at the extremes. A majority of the sample was majoring in the social sciences (81.5%). After the participants answered the questions used in the analysis reported here, we asked them if they had heard of the Trayvon Martin case, and approximately 89% said they had.

As shown in Table 1, respondents were much more likely to indicate that they would scream (84.8%), run away (74.7%), or fight back (77.6%) if confronted with a situation similar to the Zimmerman–Martin encounter than pull a weapon other than a gun (33.6%), use this weapon (32.5%) or pull a gun (15.0%) or shoot one (7.7%). That is, very few respondents indicated that they would consider pulling a gun, and even fewer said they would consider shooting one. In contrast to George Zimmerman’s reaction, an overwhelming majority of this sample indicated that shooting was not something they would do.

In terms of racial socialization, respondents as a group generally indicated that their parents “rarely” engaged in promotion of mistrust (mean = 1.82) and preparation for bias (mean = 2.39) and “sometimes” (mean = 2.89) provided cultural socialization. The mean (1.32) for the group on their perceptions of subcultural diversity issues in their home neighborhoods was also low, indicating they generally did not see language, cultural and racial differences between residents to be a problem there. That is, generally, race and racial differences, as measured here, do not appear to be particularly salient to this group.

Fear of crime is our third primary predictor variable of interest, and fear was more relevant for this group than issues of race were. Respondents were more likely to indicate that they currently were “afraid” of violent crime (mean = 2.44) than property crime (mean = 2.03), for which they were generally “somewhat afraid.” This level of violent crime-related fear is especially interesting, given that the respondents were college students on a residential campus at a large university, which some assume are generally safe places (but see Sloan and Fisher 2011).

Bivariate correlations

Table 2 shows a bivariate correlation matrix with personal characteristics, fear of crime, subcultural diversity, racial socialization, and reactions to the hypothetical situation similar to the Zimmerman–Martin case. Despite our expectations, race of the subject was not correlated at the bivariate level with anticipated personal reactions. However, the bivariate results show that females were more likely to say they would consider screaming for help and running away. Males were more likely to say they would consider pulling a gun and shooting a gun. Participants who responded as being more liberal were more likely to say they might choose to scream or run away, but political orientation was not correlated with the other responses. People who were afraid of both violent and property crime were more likely to say they would consider screaming for help and running away. Those who feared property crime were less likely to say they would fight. People who reported that their parents taught them to distrust other races (promotion of mistrust) were more likely to say they would consider both pulling a gun and shooting. Participants who indicated more concerns about subcultural diversity in their home neighborhood were slightly less likely to say they would react by screaming, but this variable was not significantly correlated with any of the other reactions.

Interestingly, although we found that some participant characteristics, fear of crime, subcultural diversity, and racial socialization variables were associated with particular reactions to the situation at the bivariate level, we did not find significant differences in how people responded when we examined the particular race and gender of the “suspicious person” (Hispanic male, Hispanic female, etc.) at the bivariate level. This in part may be due to the small numbers of people in each of the 6 conditions (ranging from 53 for suspicious white male to 74 for suspicious white female). However, when we compared reactions based on the gender of the suspicious person only (combining all races into the two to gender groups), we found that participants were more likely both to pull a gun and use a weapon (other than a gun) if the suspect was male. Additionally, there were no significant bivariate correlations among the variables when we compared reactions based only on the race of the suspicious person (combining genders). That is, the race of the suspicious person did not predict reactions to the situations at the bivariate level. Due both to the lack of bivariate correlations and to the small numbers in the individual conditions when separated by both race and gender, we present here only the models for the sample as a whole.

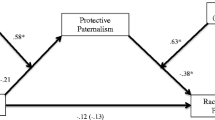

Multivariate logistic regression

Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6 show the multivariate logistic regression models predicting people’s expected choice to scream, run, pull a gun, and shoot a gun if put in a situation similar to the Trayvon Martin–George Zimmerman case. Recall that we did not run regression models for reactions with no (or only one) significant predictors at the bivariate level (that is, fight back, pull a weapon other than a gun, or use a weapon other than a gun). The presented regression models include only the independent variables that were significant at the bivariate level, except that we also include variables for the gender (female is the reference category) and race (white is the reference category) of the suspicious person in each of the sets of models. We include these gender and race variables despite their apparent statistical irrelevance at the bivariate level (except for gender and pulling a gun) not only because they focus on our theoretical questions of how much gender and race of the suspicious person matters, but also because the racial difference between Zimmerman and Martin has been a key focus of the media and commentary attention since the incident occurred. We expect that the racial difference is the key reason the case received so much attention and that readers will be interested in seeing these variables in the final analysis. Yet, given their lack of correlation with the reactions, we did not expect them to be significant predictors in the multivariate models.

For the first two sets of models—the avoidance behaviors (Tables 3, 4)—the relevant variables differed slightly in that subcultural diversity was included in Table 3 but not Table 4. For the first group of models (scream reaction; Table 3), the included variables were sex, political orientation, subcultural diversity, fear of violent crime, and property crime, as well as the sex and race of the suspicious person (see Table 2 for details). For the second group of models (run reaction; Table 4), the independent variables included were sex, political orientation, fear of violent crime, fear of property crime, and the sex and race of the suspicious person. For the remaining two sets of models (Tables 5, 6)—the defensive behaviors, or pull a gun and shoot a gun—the included independent variables were sex and promotion of mistrust as well as the sex and race of the suspicious person.

As noted, Tables 3 and 4 focus on avoidance behaviors. Table 3 shows the set of models predicting the possibility that the person would “scream for help.” The first model (column 1) includes the independent variables sex and political orientation. The overall model is significant (χ2 = 56.58, p < 0.001). However, after controlling for sex, political orientation is no longer a significant predictor of choosing to scream. Females are over 11 times more likely to say they would react by screaming for help than males (b = 2.42, p < 0.001; OR = 11.21). The second model (column 2) adds subcultural diversity (χ2 = 64.96, p < 0.001), which is significantly, but negatively related to screaming—people with more concern about subcultural diversity in their neighborhoods were less likely to say they might scream (b = − 0.81, p < 0.01, OR = 0.44). The third model (column 3) adds the independent variables of fear of violent and property crime, and the overall model is significant (χ2 = 67.01, p < 0.001). As in the previous model, after controlling for sex and subcultural diversity, the other variables—political orientation, fear of violent and property crime—are not significant predictors of choosing to scream. Women were still over 8 times more likely to say they would scream than males were (b = 2.13, p < 0.001, OR = 8.44). Also, participants that reported more subcultural diversity in their home neighborhoods were much less likely (about a third as likely) to say they would scream (b = − 0.96, p < 0.01, OR = 0.38).

The fourth model (column 4) adds the gender and race of the suspicious person, and the overall model is significant (χ2 = 71.47, p < 0.001). Similar to the previous models, after controlling for gender and race of the suspicious person, female participants were over 9 times more likely to say they would scream than males were (b = 2.30, p < 0.001). Also, participants that reported more subcultural diversity in their home neighborhoods were much less likely to say they would scream (b = − 0.97, p < 0.01, OR = 0.38). Yet, as expected based on bivariate results, the gender or race of the suspicious person was not a significant predictor of one’s likelihood of screaming.

Table 4 shows the models predicting person’s expectation that they might “run away.” The first model (column 1) includes the demographic variables. The overall model is again significant (χ2 = 78.18, p < 0.001). However, again, after controlling for gender, political orientation is no longer significant. Women are almost 11 times more likely to say they would choose to run away than males are (b = 2.40, p < 0.001, OR = 10.97). The second model (column 2) adds fear of violent and property crime, with the overall model significant (χ2 = 77.21, p < 0.001). As in the previous model, after controlling for sex, the other variables—political orientation and fear of violent and property crime—are not significant predictors of choosing to run away. As with the scream reaction, women were over 11 times more likely to run than males (b = 2.41, p < 0.001; OR = 11.09). The third model (column 3) adds gender and race of the suspicious person, with the overall model significant (χ2 = 80.23, p < 0.001). Similar to previous models, after controlling for sex of the participant, the other variables in the model are not significant predictors of choosing to run away. In the final model, women were about 12 times more likely to say they would run than males were (b = 2.48, p < 0.001; OR = 11.97). In sum, for the avoidance behaviors, gender—or being female—is the strongest predictor of indicating one would consider screaming or running away in a scuffle with a suspicious person in the neighborhood.

The next two tables reflect defensive behaviors, or those that are more assertive rather than passive. Table 5 shows the models predicting the willingness to “pull a gun” in the potentially threatening situation. The first model (column 1) only includes respondent sex, because the other personal characteristics were not correlated at the bivariate level. The overall model is significant (χ2 = 13.86, p < 0.001). Men were three times more likely to say they would consider pulling a gun compared to females (b = − 1.15, p < 0.001, OR = 0.32), when other variables are not in the model. The second model (column 2) includes the sex of the participant and promotion of mistrust, because those are the only theoretical variables of interest that were correlated at the bivariate level with choosing to pull a gun. The overall model is significant (χ2 = 19.49, p < 0.001). After controlling for sex, promotion of mistrust remains a significant predictor of pulling a gun (b = 0.35, p < 0.05, OR = 1.42). People whose parents more often promoted mistrust of other races and ethnicities were almost one and a half times more likely to say they would consider pulling a gun. This model shows that again men are over three times more likely to say they would pull a gun than females were (b = − 1.11, p < 0.001, OR = 0.33). The third model (column 3) includes the sex of the participant, promotion of mistrust, and gender and race of the suspect. The overall model is significant (χ2 = 25.44, p < 0.001). After controlling for gender and race of the suspicious person, both gender of the participant (b = − 1.13, p < 0.001) and promotion of mistrust (b = 0.36, p < 0.05) remain significant. People whose parents promoted mistrust of other races and ethnicities were almost one and a half times more likely to say they would consider pulling a gun. Women were about 1/3 as likely to say they would pull a gun as men were. Additionally, participants were twice as likely to say they would pull a gun if the suspicious person was male (b = 0.74, p < 0.05, OR = 2.10) rather than female. But, interestingly and as expected based on the bivariate analysis, encountering a black or Hispanic suspicious person did not increase the likelihood willingness to pull a gun when compared to encountering a suspicious white person.

The final models in Table 6 show a multivariate logistic regression model predicting the willingness to shoot a gun in a situation similar to the George Zimmerman–Trayvon Martin case. This scenario is closest to the circumstances that happened in that case. The first model only includes participant sex, and males are over 2 times more likely to say they might choose to shoot a gun than females (b = − 0.93, p < 0.05, OR = 0.40). The second model adds the only theoretical variable that was significant at the bivariate level—promotion of mistrust (see Table 2 for details). The overall model is significant (χ2 = 11.41, p < 0.01), and both variables remain significant in this model. Males were still about 2 times more likely to say they might react by shooting a gun than females were (b = − 0.86, p < 0.05; OR = 0.42). People who heard more promotion of mistrust messages about other races/ethnicities as children were significantly more likely (1.58 times) to say they might react by shooting a gun compared to those who did not hear those messages (b = 0.46, p < 0.01; OR = 1.58). The third model adds gender and race of the suspicious person, with the overall model significant (χ2 = 14.09, p < 0.05). Both gender of the participant and promotion of mistrust remain significant in this model. Males were still about 2 times more likely to say they might react by shooting a gun than females were (b = − 0.89, p < 0.05; OR = 0.41). People who heard more promotion of mistrust messages about other races/ethnicities as children were significantly more likely (1.62 times) to say they would react by shooting a gun compared to those who did not hear those messages (b = 0.49, p < 0.01; OR = 1.62). Contrary to what some might expect but consistent with the bivariate results, the characteristics of the suspicious person are not significant predictors of willingness to shoot a gun, at least in this sample.

Discussion and conclusions

We set out to examine three research questions. First, we asked if fear of crime and racial socialization, particularly parental promotion of mistrust of other races during childhood and subcultural diversity concerns, predicted one’s willingness to choose a violent reaction if faced with a situation similar to the George Zimmerman–Trayvon Martin case. We found that few of our respondents overall reported promotion of mistrust by their parents or concerns about subcultural diversity in their home neighborhoods. We also found that respondents were more afraid of violent crime than property crime. In terms of their relationship to expected reactions to a confrontation, we found that fear and mistrust mattered in some cases. Specifically, at the bivariate level, fear of both violent and property crime was associated with the willingness to scream and run away, and fear of property crime was significantly related to the willingness to fight when encountering a suspicious person. Promotion of mistrust was significantly associated with both being willing to pull a gun and shoot one, but not other reactions.

We ran multivariate models only in cases where more than one variable was significant at the bivariate level—scream, run away, pull a gun and shoot a gun. In the multivariate models, we found that fear of crime dropped out of both the scream and run models after we controlled for other variables. Promotion of mistrust remained a significant predictor of being willing to both pull a gun and shoot one, even after controlling for the participants’ gender, and the characteristics of the suspect. Recall that we included subcultural diversity as a theoretical predictor, because we thought that concern about other races might be, in part, due to racial socialization in childhood. This variable was only related at the bivariate level to the scream reaction, and negatively so. In other words, people who were more concerned about subcultural diversity were less likely to scream. In the multivariate models, we found this relationship remained. We do not have the data to help us understand why this is so, but it may be that people who are concerned about racial differences in the neighborhood do not trust their neighbors enough to scream for help.

Second, we asked if men were more likely than women to say they would consider responding with violence in this type of situation. We found that in general they were. Gender was the most consistent predictor in the models overall, but findings depended on the expected behavior. At the bivariate level, women were more likely to say they would consider screaming and running, and men were more likely to say they might pull a gun or shoot one if faced with a situation similar to the Zimmerman–Martin case. When we ran multivariate models for these reactions, we found gender held strong as a predictor in these same directions, no matter what other variables were in the models. Women were still more likely to say they would probably scream or run. Men were more likely to say they would pull a gun and shoot a gun, and this was true even though promotion of mistrust was also significant in these models. Gender was a clear predictor of the likely reaction to the incident—in line with prior research, women were more likely to choose avoidance behaviors and men were more likely to choose defensive reactions (see Lane et al. 2014, for a summary).

Finally, we asked if the race/ethnicity of the “suspicious” person encountered affected the likelihood of being willing to choose violence. In general, we found that it did not. Race of the suspicious person was not related at the bivariate level to any of the possible reactions. Yet, because there still was so much media coverage focused on this issue before and during the Zimmerman trial, we used race of the suspicious person as a predictor in the multivariate models. As expected, based on the bivariate results, in none of the models for this sample was race of the suspicious person a significant predictor of expected reactions in an encounter.

This is the first study we know of that explicitly examines the issue of racial socialization and one’s expected reactions if put in the position George Zimmerman faced when he encountered Trayvon Martin. There are limitations to this study that reduce its generalizability, but the study produces some interesting findings and at least raises some interesting questions for future study.

First, we did not expect to find that people who encountered a hypothetical Black or Hispanic person would be no more likely to choose any of the reactions than those who encountered a White one, especially if implicit bias was affecting results. There are some limitations to this study that could explain these findings. It could be in part because respondents were hyper aware of race and cautious in their responses when they saw a racial or ethnic minority in the vignette and were not honest. Gallup found as recently as 2017 that almost half of Americans worried “a great deal” about race relations, and that these concerns are greater than they have ever been before (Swift 2017), which may point to this possibility. In addition, the sample included only undergraduates and they were going to school in Florida, where the Trayvon Martin–George Zimmerman incident was a regular point of discussion in the news and elsewhere at the time of this data collection. After answering the questions analyzed here, an overwhelming majority said they knew about the case. Given this context, respondents may not have been willing to admit that would consider shooting a black or Hispanic person who looks suspicious; even though they in fact would consider such an action. Undergraduates are also an educated group who may be more open-minded, or at least less likely to admit to unease with other races generally, than people in their age group not going to college.

Future studies may be able to examine this issue in different ways—by looking at different samples (e.g., not college students or not in Florida), conducting the study at a different time (e.g., not when the Trayvon Martin case is still such a hot issue) or asking additional questions in an attempt to better explain this finding (e.g., asking how comfortable people feel talking about racial differences and measuring prejudice or bias). In addition, it would be useful to increase the sample size to allow for separate multivariate models by race and/or gender of the suspicious person.

Still, despite the obvious racial characteristic of the other failing to reach significance, in some cases promotion of mistrust—or negative parental socialization about other racial groups—mattered. Interestingly, promotion of mistrust mattered most when we measured willingness to pull or use a gun. We expected fear of crime and promotion of mistrust to be correlated, but they were not in this sample. That is, based on these results we cannot say that the connection between promotion of mistrust and willingness to use a gun is related to fear of crime. Although the relationship among these variables clearly needs more study, it may be that in the South, mistrust of other races and willingness to carry and/or use a gun are more embedded in culture and socialization than connected to fear of crime.

In fact, in this sample fear of crime was not related to willingness to shoot, even at the bivariate level. We expect that this is because so few people were willing to shoot (N = 26, 7.7%). Future studies of people who own guns might be better situated to examine the connection between racial socialization, fear of crime and willingness to shoot in a potentially threatening situation. Gun socialization—or parental training about the positive and negative aspects of guns, when to use guns, etc.—may be an important predictor of how people might be willing to react in scary encounters (see Lizotte et al. 1981), especially if it is combined with racial mistrust or prejudice. This data set does not contain measures to test this idea. Future studies might collect measures to allow researchers to examine how racial socialization, gun socialization, fear of crime, and expected reactions in threatening situations connect and interact. Gun carrying is more common in the South (Felson and Pare 2010), where this study occurred. One limitation of this study, consequently, is that it did not measure gun socialization or gun ownership or prejudice directly.

Another noteworthy finding here is that gender matters in terms of expected reactions; we think pointing to both the importance of gender and gender socialization as fear of crime literature has consistently considered (see Lane et al. 2014). Women were more likely to indicate that they would scream or run away regardless of their own race or that of the person they encountered, while men were more likely to say they would consider pulling or using a gun. In fact, in the multivariate models where fear of crime was correlated at the bivariate level (i.e., scream and run), it was no longer significantly related once gender was included as a predictor in the model. This points to the consistent finding in fear of crime research that gender is a fundamental predictor of crime-related fear. Moreover, it likely points to the importance of gender socialization in how one responds to threatening situations—that is, women are more likely than men are to choose avoidance responses (see Lane 2013; Lane et al. 2014, for a review). Related to these gender differences is what may be a measurement limitation of this survey. We asked if subjects would consider “screaming,” and as another fear researcher mentioned to us, this word choice may make it difficult for men to respond affirmatively due to gender expectations. As he correctly noted, if we had also asked if they would consider “yelling,” more men may have agreed that they might, because the word “scream” may be associated in their minds with femininity and therefore possibly weakness (Farrall 2013, personal communication).

While this study has limitations and it is too early to make policy recommendations, this research is a first step toward thinking about the possible impacts of racial socialization as a child on fear of crime and possible reactions during a scary encounter. The results show that promotion of mistrust of other racial groups is related to willingness to both pull a gun and shoot one when in a scuffle. In addition, the study points to the importance of studying both racial and gender socialization, and to looking at how these two phenomena interact to lead to how people think they might react if put in a situation where they face the immediate possibility of victimization. Yet, there is good news here in that only about 8% of the respondents would react the same way as Zimmerman in a similar situation, regardless of the race of the person they encountered.

Notes

Although one study found that among white males, those who were prejudiced were more likely to own guns to protect themselves (Young 1985).

Some of the research on gun ownership uses measures of fear (e.g., being afraid to walk alone in the neighborhood at night), which have questionable validity and reliability and may actually measure perceived risk (Ferraro 1995; LaGrange and Ferraro 1987; Ferraro and LaGrange 1987, 1988). It is less clear if similar findings would result if better measures of fear were used (e.g., fear of being shot or murdered).

References

Alvarez, L. 2013. In Zimmerman case, self-defense was hard to topple. The New York Times, July 14. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/15/us/in-zimmerman-case-self-defense-was-hard-to-topple.html?_r=0. Accessed 15 Oct 2013.

Arthur, J.A. 1992. Criminal victimization, fear of crime, and handgun ownership among blacks: Evidence from national survey data. American Journal of Criminal Justice 16: 121–141.

Bankston, W.B., C.Y. Thompson, Q.A.L. Jenkins, and C.J. Forsyth. 1990. The influence of fear of crime, gender, and southern culture on carrying firearms for protection. The Sociological Quarterly 31: 287–305.

Baumer, T.L. 1978. Research on fear of crime in the United States. Victimology 3: 254–264.

Bentley, K.L., V.N. Adams, and H.C. Stevenson. 2008. Racial socialization: Roots, processes and outcomes. In Handbook of African American psychology, ed. H.A. Neville, B.M. Tynes, and S.O. Utsey, 255–267. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Biafora, F.A., G.J. Warheit, R.S. Zimmerman, A.G. Gil, E.A. Apospori, W.A. Vega, and D.L. Taylor. 1993. Cultural mistrust and deviant behaviors among ethnically diverse black adolescent boys. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 23: 891–910.

Botelho, G. 2012. What happened the night Trayvon Martin died. (May 23). http://www.cnn.com/2012/05/18/justice/florida-teen-shooting-details. Accessed 7 Aug 2013.

Bursik Jr., R.J., and H.G. Grasmick. 1993. Neighborhoods and crime: The dimensions of effective community control. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Cao, L., F.T. Cullen, S.M. Barton, and K.R. Blevins. 2002. Willingness to shoot: Public attitudes toward defensive gun use. American Journal of Criminal Justice 27: 85–109.

Carlson, J. 2016. Moral panic, moral breach: Bernhard Goetz, George Zimmerman, and racialized news reporting in contested cases of self-defense. Social Problems 63: 1–20.

Carroll, J. 2007. How Americans protect themselves from crime. Gallup. http://www.gallup.com/poll/102418/How-Americans-Protect-Themselves-From-Crime.aspx. Accessed 15 Oct 2013.

Caughy, M.O., S.M. Nettles, P.J. O’Campo, and K.F. Lohrfink. 2006. Neighborhood matters: Racial socialization of African American children. Child Development 77 (4): 1220–1236.

Caughy, M.O., P.J. O’Campo, S.M. Randolph, and K. Nickerson. 2002. The influence of racial socialization practices on the cognitive and behavioral competence of African American preschoolers. Child Development 73: 1611–1625.

Coard, S.I., and R.M. Sellers. 2005. African American families as a context for racial socialization. In African American family life: Ecological and cultural diversity, ed. V.C. McLoyd, N.E. Hill, and K.A. Dodge, 264–284. New York: Guilford Press.

Cobbina, J.E., J. Miller, and R.K. Brunson. 2008. Gender, neighborhood danger, and risk-avoidance strategies among African-American youths. Criminology 46: 673–709.

Covington, J., and R.B. Taylor. 1991. Fear of crime in residential neighborhoods: Implications of between- and within-neighborhood sources for current models. The Sociological Quarterly 32: 231–249.

De la Roca, J., I.G. Ellen, and K.M. O’Regan. 2014. Race and neighborhoods in the 21st century: What does segregation mean today? Regional Science and Urban Economics 47: 138–151.

DeFronzo, J. 1979. Fear of crime and handgun ownership. Criminology 17: 331–339.

Demo, D.H., and M. Hughes. 1990. Socialization and racial identity among black Americans. Social Psychology Quarterly 53: 364–374.

Drake, B. 2014. 5 Facts about the NRA and guns in America. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/04/24/5-facts-about-the-nra-and-guns-in-america/. Accessed 9 June 2017.

Evans, A.B., J. Banerjee, R. Meyer, A. Aldana, M. Foust, and S. Rowley. 2012. Racial socialization as a mechanism for positive youth development among African-American youths. Child Development Perspectives 6: 251–257.

Farrall, S. 2013. Personal communication, November 20, 2013.

Felson, R.B., and P.P. Pare. 2010. Gun cultures or honor cultures? Explaining regional and race differences in weapon carrying. Social Forces 88: 1357–1378.

Ferraro, K.F. 1995. Fear of crime: Interpreting victimization risk. New York: State University of New York Press.

Ferraro, K.F. 1996. Women’s fear of victimization: Shadow of sexual assault? Social Forces 75: 667–690.

Ferraro, K.F., and R.L. LaGrange. 1987. The measurement of fear of crime. Sociological Inquiry 57: 70–101.

Ferraro, K.F., and R.L. LaGrange. 1988. Are older people afraid of crime? Journal of Aging Studies 2 (3): 277–287.

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. 2017a. Number of licensees by type. http://www.freshfromflorida.com/content/download/7471/118627/Number_of_Licensees_By_Type.pdf. Accessed 9 June 2017.

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. 2017b. Concealed weapon or firearm license holder profile as of May 31, 2017. http://www.freshfromflorida.com/content/download/7500/118857/cw_holders.pdf. Accessed 9 June 2017.

Friedson, M., and P. Sharkey. 2015. Violence and neighborhood disadvantage after the crime decline. Annals of American Academy of Political and Social Science 660: 341–358.

Gainey, R., M. Alper, and A.T. Chappell. 2011. Fear of crime revisited: Examining the direct and indirect effects of disorder, risk perception, and social capital. American Journal of Criminal Justice 36: 120–137.

Goodey, J. 1997. Boys don’t cry: Masculinities, fear of crime, and fearlessness. British Journal of Criminology 37: 401–418.

Granberg, E.M., M.B. Edmond, R.L. Simons, F.X. Gibbons, and M.K. Lei. 2012. The association between racial socialization and depression: Testing direct and buffering associations in a longitudinal cohort of African American young adults. Society and Mental Health 2 (3): 207–225.

Greenwald, A.G., and L.H. Krieger. 2006. Implicit bias: Scientific foundations. California Law Review 94: 945–967.

Hagerman, M.A. 2018. White kids: Growing up with privilege in a racially divided America. New York: New York University Press.

Henson, B., and B.W. Reyns. 2015. The only thing we have to fear is fear itself…. and crime: The current state of the fear of crime literature and where it should go next. Sociology Compass 9: 91–103.

Hibdon, J., J. Schafer, C. Lee, and M. Summers. 2016. Avoidance behaviors in a campus residential environment. Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law and Society 17: 74–89.

Hill, G.D., F.M. Howell, and E.T. Driver. 1985. Gender, fear, and protective handgun ownership. Criminology 23: 541–552.

Hollander, J.A. 2001. Vulnerability and dangerousness: The construction of gender through conversation about violence. Gender and Society 15: 83–109.

Hughes, D., and L. Chen. 1997. When and what parents tell children about race: An examination of race-related socialization among African American families. Applied Developmental Science 1: 200–214.

Hughes, D., and D. Johnson. 2001. Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family 63: 981–995.

Hughes, D., J. Rodriguez, E.P. Smith, D.J. Johnson, H.C. Stevenson, and P. Spicer. 2006. Parents’ ethnic–racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology 42 (5): 747–770.

Hughes, D., D. Witherspoon, D. Rivas-Drake, and N. West-Bey. 2009. Received ethnic–racial socialization messages and youths’ academic and behavioral outcomes: Examining the mediating role of ethnic identity and self-esteem. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 15: 112–124.

Huynh, V.W., and A.J. Fuligni. 2008. Ethnic socialization and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology 44: 1202–1208.

Jones, J.M. 2013. Men, married, southerners most likely to be gun owners. Gallup. http://www.gallup.com/poll/160223/men-married-southerners-likely-gun-owners.aspx?version=print. Accessed 4 Nov 2013.

Kalesan, B., M.D. Villarreal, K.M. Keyes, and S. Galea. 2016. Gun ownership and social gun culture. Injury Prevention 22 (3): 216–220.

LaGrange, R.L., and K.F. Ferraro. 1987. The elderly’s fear of crime: A critical examination of the research. Research on Aging 9: 372–391.

Lane, J. 2002. Fear of gang crime: A qualitative examination of the four perspectives. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 39: 437–471.

Lane, J. 2006. Exploring fear of general and gang crimes among juveniles on probation: The impacts of delinquent behaviors. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 4: 34–54.

Lane, J. 2009. Perceptions of neighborhood problems, fear of crime, and resulting behavioral precautions: Comparing institutionalized girls and boys in Florida. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 25: 264–281.

Lane, J. 2013. Theoretical explanations for gender differences in fear of crime: Research and prospects. In Routledge international handbook of crime and gender studies, ed. C.M. Renzetti, S.L. Miller, and A.R. Gover, 57–67. New York: Routledge.

Lane, J., and K. Fox. 2012. Fear of crime among gang and non-gang offenders: Comparing the impacts of perpetration, victimization, and neighborhood factors. Justice Quarterly 29: 491–523.

Lane, J., and J.W. Meeker. 2000. Subcultural diversity and the fear of crime and gangs. Crime and Delinquency 46: 497–521.

Lane, J., and J.W. Meeker. 2003. Fear of gang crime: A look at three theoretical models. Law and Society Review 37: 425–456.

Lane, J., and J.W. Meeker. 2004. Social disorganization perceptions, fear of gang crime, and behavioral precautions among Whites, Latinos, and Vietnamese. Journal of Criminal Justice 32: 49–62.

Lane, J., N.E. Rader, B. Henson, B.S. Fisher, and D.C. May. 2014. Fear of crime in the United States: Causes, consequences, and contradictions. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Lee, M.S., and J.T. Ulmer. 2000. Fear of crime among Korean Americans in Chicago communities. Criminology 38 (4): 1173–1206.

Lesane-Brown, C.L. 2006. A review of race socialization with Black families. Developmental Review 26: 400–426.

Liu, L.L., and A.S. Lau. 2013. Teaching about race/ethnicity and racism matters: An examination of how perceived ethnic racial socialization processes are associated with depression symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 9: 383–394.

Liska, A.E., J.J. Lawrence, and A. Sanchirico. 1982. Fear of crime as a social fact. Social Forces 60: 760–770.

Liska, A.E., A. Sanchirico, and M.D. Reed. 1988. Fear of crime and constrained behavior: Specifying and estimating a reciprocal effects model. Social Forces 66: 827–837.

Lizotte, A.J., D.J. Bordua, and C.S. White. 1981. Firearms ownership for sport and protection: Two not so divergent models. American Sociological Review 46: 499–503.

Luxenburg, J., F.T. Cullen, R.H. Langworthy, and R. Kopache. 1994. Firearms and fido: Ownership of injurious means of protection. Journal of Criminal Justice 22: 159–170.

Madriz, E. 1997. Nothing bad happens to good girls: Fear of crime in women’s lives. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

May, D.C., N.E. Rader, and S. Goodrum. 2010. A gendered assessment of the “threat of victimization”: Examining gender differences in fear of crime, perceived risk, avoidance, and defensive behaviors. Criminal Justice Review 35: 159–182.

McGarrell, E.F., A.L. Giacomazzi, and Q.C. Thurman. 1997. Neighborhood disorder, integration, and the fear of crime. Justice Quarterly 14 (3): 479–500.

Merry, S.E. 1981. Urban danger: Life in a neighborhood of strangers. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Mullen, J. 2015. George Zimmerman accuses Obama of inflaming racial tensions. CNN, March 24. https://www.cnn.com/2015/03/24/us/george-zimmerman-obama-race-comments/index.html. Accessed 23 Aug 2019.

O’Connor, L. 2015. Sean Hannity enrages Fox News panel by defending George Zimmerman. HuffPost, June 11. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/fox-hannity-george-zimmerman_n_7562522. Accessed 23 Aug 2019.

Open carrying of weapons. Florida Statute 790.053. http://www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&URL=0700-0799/0790/Sections/0790.053.html. Accessed 9 June 2017.

Owning guns: One in three have a gun in their household. 2013. https://today.yougov.com/news/2013/02/21/owning-guns-one-three-have-gun-their-household/. Accessed 9 June 2017.

Parker, K.D. 1988. Black–white differences in perceptions of fear of crime. Journal of Social Psychology 128: 487–498.

Parker, K.D., and M.C. Ray. 1990. Fear of crime: An assessment of related factors. Sociological Spectrum 10: 29–40.

Priest, N., J. Walton, F. White, E. Kowal, A. Baker, and Y. Paradies. 2014. Understanding the complexities of ethnic–racial socialization processes for both minority and majority groups: A 30-year systematic review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 43: 139–155.

Rader, N.E., and S.H. Haynes. 2014. Avoidance, protective, and weapons behaviors: An examination of constrained behaviors and their impact on concerns about crime. Journal of Crime and Justice 37: 197–213.

Rader, N.E., D.C. May, and S. Goodrum. 2007. An empirical assessment of the “threat of victimization:” Considering fear of crime, perceived risk and avoidance and defensive behaviors. Sociological Spectrum 27: 475–505.

Rollins, A., and A.G. Hunter. 2013. Racial socialization of biracial youth: Maternal messages and approaches to address discrimination. Family Relations 62: 140–153.

Sampson, R.J., and W.B. Groves. 1989. Community structure and crime: Testing social disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology 94: 774–802.

Schafer, J.A., B.M. Huebner, and T.S. Bynum. 2006. Fear of crime and criminal victimization: Gender-based contrasts. Journal of Criminal Justice 34 (3): 285–301.

Serino, C.F. 2012. Report of investigation. Agency Report Number 201250001136. Sanford Police Department. https://www.scribd.com/document/93951121/State-v-Zimmerman-Evidence-released-by-prosecutor. Accessed 10 Jan 2019.

Shaw, C.R., and H.D. McKay. 1942. Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.