Abstract

Crime victimization and fear of crime have been studied extensively in the extant literature, but very few studies have been carried out in sub-Saharan Africa. Using a sample of 523 students from a leading university in Nairobi, Kenya, we found that females, older students, and prior crime victims are more fearful of crime at school, of crime in the community, and of overall crime. In addition, we found that incivility, measured as the perceived prevalence of drug use among Kenyans, was also statistically significantly related to fear of crime at school, fear of crime in the community, and the overall measure of fear of crime. These findings are consistent with findings from the extant literature, mainly from the United States. Thus, we argue that the correlates of fear of crime appear to be similar in different geopolitical contexts. The implications of the findings for campus safety and security are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Becoming a victim of crime is a major concern for citizens of every nation, and it is undoubtedly one of the principal concerns of community members in the United States (Cohen 2008). Relatedly, university campuses around the world are not immune to the problem of crime. Both administrators and students worry about school safety, even though most college campuses have structures and procedures in place to both increase the risk for committing crimes and lower the risk of becoming a crime victim. Although the crime victimization and fear of crime literature is replete with studies from the developed world (Fisher et al. 1995; Fisher and May 2009; Fisher and Sloan 2003; Fox et al. 2009; McCreedy and Dennis 1996), very few studies have been carried out in sub-Saharan African countries, such as Kenya, to test the relationship between crime victimization (and other correlates) and fear of crime.

This study fills the gap in the extant literature by assessing the impact of gender, crime victimization, incivility, and other variables on fear of crime among college students at a prominent public university in the Kenyan capital of Nairobi. This study is important because sub-Saharan Africa is known for the highest levels of criminal victimization across the globe (Di Tella et al. 2008; Sulemana 2015), yet very few studies measuring crime victimization and fear of crime on the African continent exist. Indeed, a handful of studies have studied the impact of fear of crime on economic well-being in Africa, one being a study of the impact of fear of crime in South Africa (Moller 2005; Powdthavee 2005), and the other a study involving the citizens of Malawi (Davies and Hinks 2010). Sulemana (2015) went a step further by studying the effect of fear of crime and crime victimization on subjective well-being in Africa using data involving 20 African countries.

Interestingly, however, the three aforementioned studies examined fear of crime in relation to economic well-being, which does not address the issue from a criminological perspective. Thus, the current study is one of the first to test the relationship between crime victimization and fear of crime on the African continent from a purely criminological perspective. Additionally, this is the first study about crime on a Kenyan college campus carried out by U.S.-based scholars.Footnote 1 Specifically, we test the Kenyan students’ views about fear of crime on their college campus and in the local community. This approach would allow us to determine if there are variations in the students’ levels of fear of crime. We also test the relationship between crime victimization (in addition to other variables) and the composite measure of fear of crime (our “global” measure of fear of crime) and compare the results to the analyses in which we employ fear of crime on campus and fear of crime in the community as single-item dependent variables.

College campuses may be relatively safe and crime-free, but students still fear the possibility of falling prey to crime (Fisher et al. 1995; Fox et al. 2009). Thus, the fear of becoming a victim of crime on a college campus can have a negative impact on a student’s capacity to concentrate on his or her studies (Bachman et al. 2011). Additional stressors such as “psychological distress, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder” (Bachman et al. 2011, p. 707; see also Dao et al. 2006) can arise due to students’ concerns about their safety on campus. We note here that the most recent annual crime report for this Kenyan university indicates that there were over 100 crimes committed on campus during the year in question, with about half of the crimes committed by students. Fear of victimization may also lead some students to avoid certain places on campus, especially areas known to increase the risk of victimization. We argue therefore that crime victimization would lead to heightened levels of fear of crime.

Fear of crime on college campuses

Bennett and Flavin (1994) observed over two decades ago that conceptual models addressing fear of crime were generally developed to explain fear of crime in the United States. In fact, the literature on fear of crime is dominated by research conducted by American scholars, within America’s borders, and, in spite of five decades of fear-of-crime research, there are still only a handful of fear-of-crime studies conducted outside of the United States, thus limiting scholars’ and practitioners’ ability “to explain crime-related phenomena such as victimization or fear of crime in a comparative context” (Bennett and Flavin 1994, p. 358). The problem of comparative fear-of-crime research extends to university student samples as well. Indeed, U.S.-based scholars, who have led the charge on fear-of-crime research on U.S. college campuses (Day 1994; Fisher and May 2009; Fisher and Sloan 2003; Hilinski 2009; Lee and Hilinski-Rosick 2012; Starkweather 2007) have otherwise not ventured outside of the United States to test the same conceptual models that address fear of crime on U.S. college campuses. The current study fills this important gap, as the authors are the first to study fear of crime on a college campus in Kenya, a sub-Saharan African country. Thus, this study engenders a comparative analysis of fear-of-crime research among college students on different continents.

Literature review

Crime victimization and fear of crime

The literature on the fear of crime is relatively new, going back approximately five decades only (Ferraro 1995; Fox et al. 2009; Schafer et al. 2006). In conceptualizing fear of crime, Ferraro and LaGrange (1987) have observed scholars’ lack of agreement on the definition of the concept. They argued that a lack of delineation between risk and fear of crime in many fear-of-crime studies was problematic. Citing the work of DuBow et al. (1979), they argued that fear of crime studies should distinguish between judgments (risk to oneself and others) and emotions (fear for one’s and others’ victimization). Ferraro and LaGrange (1987) then argued that “measures of fear of crime should tap the emotional state of fear rather than judgments or concerns about crime” (p. 81). We employ the emotional strand of fear of crime in the current study.

Fear of crime has been generally understood as the body’s response to crime or news about crime (Ferraro and LaGrange 1987). Fear of crime may have health-promoting benefits, if deployed appropriately. In other words, understanding the relationship between crime and victimization may produce a healthy fear of crime. It is when fear of crime takes on a debilitating tone, leading to increased levels of panic and anxiety, that it becomes unhealthy (Warr 2000). Ferraro (1995) observed that the emotional response exhibited by a person fearful of crime could be dread or anxiety, and either of these emotional manifestations is itself tied to feelings of threat to one’s safety. Thus, we employ fear-of-crime items that measure the emotional response of the participants in the current study.

Some scholars have delineated specific crime types in their fear-of-crime studies. Ferraro and LaGrange (1987) noted that measuring a “universal” concept of crime is inherently useful, although tapping into specific crimes, such as property or violent crimes (e.g., rape, assault, and robbery), has its own unique advantages. And while multiple items may be preferable for measuring the fear of crime, almost one-half of all studies on fear of crime had employed single-item indicators to denote this variable (Ferraro and LaGrange 1987; Lane et al. 2014). It can be argued, then, that employing single-item measures to measure the fear of crime may be conceptually sound, if the argument is to separate the fear-of-crime variable into specific crime types, such as robbery or rape. Still, some scholars insist that multiple-item indicators are preferable to single-item indicators for measuring an important psychological construct such as the fear of crime.

Not unlike testing the effects of personal and vicarious experiences on satisfaction with police (Pryce 2016a; Tyler et al. 2015; Weitzer and Tuch 2002, 2005), fear-of-crime scholars have argued that it may be necessary to delineate the effects of primary and vicarious victimizations on fear of crime (Fox et al. 2009; Skogan and Maxfield 1981). It can be argued that a victim of assault on a college campus would express fear of crime, but so would a friend of the victim. This connection between personal and vicarious experiences has been tested extensively in both fear-of-crime and policing studies. This distinction between personal and vicarious experiences is important because it allows researchers to understand the influence of external stimuli on how people process fear, not just fear of crime that arises from personal victimization. For example, media outlets play an important role in disseminating stories of crime, whether the crimes occurred on college campuses or in the larger community. It is therefore reasonable to argue that anyone—college student or otherwise—who follows the news by watching television, listening to the radio, or perusing the Internet would be exposed to crime information. Understanding how the news affects fear-of-crime levels in the population is thus important. While we are aware of this dichotomy between personal and vicarious experiences, we limit our study of crime victimization to only personal victimization because of the types of questions posed to the research participants.

Crime victimization has been known to be statistically significantly related to fear of crime in a number of studies, although the strength of the relationship has varied (Quann and Hung 2002; Skogan 1987; Tseloni and Zarafonitou 2008). Skogan (1987), for example, found that community members who had previously been victimized reported higher levels of fear of crime. Tseloni and Zarafonitou (2008) also found that those who had suffered personal and vicarious victimization reported higher levels of fear of crime than those who had not been victimized. Although the level of fear far exceeds crime levels in the community (Lab 2016), the disparity is generally attributable to the body’s emotional response to perceptions that crime is occurring everywhere and at all times. As Lab (2016) has noted, “both official and victimization measures show that less than 10 percent of the population is victimized, despite fear of 40 percent or more” (p. 17). It is precisely this disparity that may account for the positive relationship between crime victimization and fear of crime in a number of past studies (Bachman et al. 2011; Ferguson and Mindel 2007; Roundtree 1998; Will and McGrath 1995). Interestingly, however, other research studies did not find a statistically significant relationship between crime victimization and fear of crime (Ferraro 1995; Garofalo 1979; McGarrell et al. 1997). Yet other research studies have argued that finding a statistical relationship between crime victimization and fear of crime is inextricably tied to the measures and conceptualizations employed for both constructs in the particular study (Baumer 1985; Bennett and Flavin 1994; Ferraro and LaGrange 1987).

Incivility

Testing the effect of incivility on fear of crime remains an important component of the literature on crime victimization and fear of crime (Bachman et al. 2011; McGarrell et al. 1997). Although several definitions and operationalizations of incivility exist in the extant criminological literature (Bennett and Flavin 1994; Cao et al. 1996; Dai and Johnson 2009; Reisig and Parks 2000), we employ LaGrange et al.’s (1992) definition of incivility, which is the “erosion of conventionally accepted norms and values” (p. 312). Lab (2016) provides examples of social incivility discussed in the extant literature: public drunkenness, vagrancy, and overt drug sale and consumption. Specifically, we measure incivility as the perceived prevalence of drug use among Kenyan citizens, which is in line with measures of incivility employed by other researchers (Box et al. 1988; Lewis and Maxfield 1980). These scholars asked respondents questions that evaluated the latter’s perceptions of drug use in the neighborhood, in addition to other measures of incivility. LaGrange et al. (1992) classified drug use as social incivility, which is quite distinct from physical incivility, which includes dilapidated buildings in a neighborhood. While research has generally shown that higher levels of incivility predict higher levels of fear of crime (Bachman et al. 2011; LaGrange et al. 1992), results have also depended on whether or not measures of social incivility or physical incivility, or even objective measures of incivility recorded by trained researchers, were employed in the study (Covington and Taylor 1991). Overall, research shows that incivility tends to be significantly related to fear of crime (Lane and Fox 2012; Lane and Meeker 2011).

Demographic factors and fear of crime

Past research studies have employed demographic variables either as independent variables or as control variables (Fox et al. 2009). In this study, gender and age, in addition to crime victimization and incivility, are employed as independent variables to test their independent effects on fear of crime. Gender differences in the measurement of fear of crime have been extensively studied by scholars (Fisher 1995; Fox et al. 2009; McCreedy and Dennis 1996; Warr 2000). For example, males are more likely to be victimized than females (Craven 1997; Di Tella et al. 2008; Lauritsen and Heimer 2008). And although males, especially young Black males, have a higher risk of victimization, females exhibit higher levels of fear of crime on college campuses as well as in the wider community (Fisher 1995; Fox et al. 2009; Gibson et al. 2002). Several other studies confirm that women are the most fearful group in the community (Baumer 1985; Perkins and Taylor 1996; Will and McGrath 1995), in spite of the fact that women are the least victimized group (Lab 2016). Thus, a study of fear of crime among college students in Kenya is important because it will reveal whether or not female college students in Kenya are more fearful than their male counterparts. If the females are more fearful than the males, it will point further to the near-universality of gender differences in the fear of crime, considering the fact that Kenya is a different geopolitical context than, say, the United States.

Moreover, research on the intersection of gender and fear of crime has either addressed fear of crime in the aggregate, or in a disaggregated form. For both aggregated and disaggregated forms of fear of crime, women have experienced higher levels of fear of crime (Barberet et al. 2004; Fox et al. 2009; Wilcox et al. 2007). We take both aggregated and disaggregated approaches in this research study, by asking respondents to rate their fear of crime on their college campus or in the larger community. We also tested a composite measure of the two items measuring fear of crime. Because research on fear of crime is practically nonexistent in sub-Saharan African countries, we argue that this study represents an important step to understanding fear of crime among college students in sub-Saharan Africa, especially in Kenya where the current study took place.

Age is also an important correlate of fear of crime, with research pointing to older individuals as being more fearful of crime than their younger counterparts (Fox et al. 2009; Gibson et al. 2002; McGarrell et al. 1997). Other scholars have argued that younger people are actually more fearful of crime, and that studies pointing to higher levels of fear among older people may be due to the particular conceptualization of the fear-of-crime variable (Chiricos et al. 1997; Ferraro 1995; Lumb et al. 1993). Thus, testing age as a correlate of fear of crime in the current study is important and will contribute to knowledge about the age–fear of crime nexus. Because the extant literature is replete with studies involving age as a correlate of fear of crime, but more so in studies involving the general population (non-college samples) (Fox et al. 2009), it is important to include age as a correlate of fear of crime in the current study involving Kenyan college students.

Kenya: constitution, society, and policing

Kenya, not unlike many other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, has a functioning democracy, but elections have generally been marred by accusations of vote-rigging, with the concomitant violence casting a splotch on the integrity of the nation’s presidential elections. Kenya’s national elections have always been hotly contested, with the violence that erupted during and after the 2007 elections an example of how divided Kenyan society is. Even the most recent national election, which took place in October 2017 after an earlier election held in August 2017 was annulled by the country’s highest court, was marred by allegations of vote-rigging, in favor of the incumbent, Uhuru Kenyatta. A new Kenyan Constitution, approved in 2010 by 67% of Kenyan voters, was designed to bring about policing reform, but very little has been achieved so far. Indeed, it can be argued that the country’s inability to maintain a consistently peaceful democracy is reflected in its police force’s inability to maintain a safe and secure society for citizens.

The fear of crime in Kenyan society, especially in Nairobi, cannot be divorced from the “notorious gangs in Nairobi’s sprawling, dense slums” (Klopp and Kamungi 2008, p. 12). These gangs, with names such as the Taliban, Baghdad Boys, and Mungiki, are known to operate along ethnic and tribal lines (Klopp and Kamungi 2008). With crime so rampant in Nairobi, it is understandable that community members, including college students, would be concerned about their safety. In a recent empirical study involving 20 African nations, Kenyans recorded the highest levels of fear of crime (Sulemana 2015). Sulemana (2015) concluded his study by observing that “Kenya reported the highest level of fear of crime, with about 51% of respondents (or their family member) indicating fear of crime over the past year” (p. 856). This high level of fear of crime among Kenyan citizens is a direct result of a lack of confidence in Kenya’s police (Ruteere and Pommerolle 2003).

Although the police in Kenya have good intentions to curb crime and make Kenyan society safer and more secure, the former continue to face many challenges. Reports of rising crime continue to bedevil Kenya’s police (Akech 2005; Gastrow 2011; Osse 2016; Ruteere and Pommerolle 2003). Kenyan police have always operated under a totalitarian model of policing (Ruteere and Pommerolle 2003), and have consistently been accused of failing to professionally answer citizens’ calls for assistance, engage in proper criminal investigations, handle city traffic, and manage citizen protests protected by the Kenyan Constitution (Osse 2016). The police in Kenya, not unlike the police in other countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Pryce 2016a; Pryce et al. 2017; Tankebe 2008), are known to brutalize the population, kill suspects without approval from the courts, are rarely held accountable for their actions, and torture suspects held in custody (Osse 2016; Ruteere and Pommerolle 2003; Ruteere 2011). Because fear of crime on campus and in the community is tied to perceptions of police effectiveness, it is important to discuss how Kenyans view the nation’s police force and police officers.

Chronic underfunding of Kenya’s police force (Osse 2016) also means that officers are unable to provide heightened levels of security for local communities, which may translate into greater fear of crime on college campuses and in the larger community. Another problem plaguing the Kenyan police, in spite of recent attempts to institute policing reform, is the lack of adequate police preparedness to provide security in the community (Akech 2005; Osse 2007, 2016). Osse (2016) captured, matter-of-factly, the chronicity of the poor state of policing in Kenya in the following words:

Rather than investigating a case and examining the causes of alleged or proven police misconduct in order to prevent its recurrence, the officer involved was often transferred without further action. Police supervision was sometimes corrupt, fake, or otherwise incompetent. Police regulations were not shared on paper with police officers, but communicated only during training. Members of the public were reluctant to file complaints about police misconduct, believing such complaints would go unheeded. (p. 908)

This state of affairs may explain why Kenyans reported the highest levels of fear of crime in Sulemana’s (2015) study. Indeed, such high levels of fear of crime may be linked to how college students in Kenya view crime victimization, hence the importance of the current study. Like many other universities in Africa, but unlike universities in the United States, this Kenyan university does not have its own police department, but relies on security officers to provide protection on campus. Although the campus security team liaises with the Kenyan police on occasion, the absence of uniformed, gun-carrying officers on campus may also have an impact on students’ levels of fear of crime.

The current study

The current study fills a gap in the extant literature in two important ways: (a) It adds to the scant literature on the crime victimization–fear of crime relationship in sub-Saharan Africa, and (b) It adds to scholarly work on the gender–fear of crime and age–fear of crime nexuses, because “much of the prior literature on demographic correlates of fear of crime [focused] on non-college samples” (Fox et al. 2009, p. 28), primarily in Western societies. The following specific research questions are addressed: (1) What is the impact of gender on fear of crime on a Kenyan college campus? (2) What is the relationship between age and fear of crime on a Kenyan college campus? (3) Does crime victimization predict fear of crime in this sample of Kenyan college students? (4) Does perceived incivility increase fear of crime in this sample of college students? Answers to these questions will have important implications for policy on campus safety in Kenya and other sub-Saharan African nations.

Methods

Participants and procedures

The data for this study come from a survey of college students enrolled at a top-ranked public university located in the capital city of Nairobi. The cross-sectional data were obtained from a sample of 523 students who were at least 18 years of age. One of the authors, who served as a Fulbright Scholar at this Kenyan university in 2013, administered the survey questionnaire to pre-law students over several days. Official permission to conduct the survey was granted by the Dean of the Law School as well as by the individual instructors. Paper surveys were distributed to the students soon after their class sessions ended, and the surveys were completed voluntarily by the students, who were assured confidentiality as part of the survey protocol. The survey took approximately 20 min to complete. Out of 581 surveys distributed, 523 were completed and returned for the current study, resulting in an overall response rate of 90%.

Sample

The sample included 58% (n = 301) females and 42% (n = 218) males. The survey respondents ranged in age from 18 to 44 years (mean = 21.04; standard deviation [SD] = 2.6). In terms of educational level, there were 284 first-year, 86 second-year, 145 third-year, and 3 fourth-year students. This variable was then recoded into first year (n = 287) and sophomore or higher (n = 234). Finally, 277 students lived off-campus, whereas 241 lived on-campus.

Variables

Fear of crime

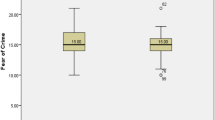

The dependent variable, fear of crime, was measured using two items. A four-point Likert-type scale—(1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) agree, and (4) strongly agree—was employed to measure this dependent variable. The scale was coded so that higher scores reflected higher levels of fear of crime. The two survey items were (1) I am fearful of being a victim of crime at school.Footnote 2 (2) I am fearful of being a victim of crime in my home community. These items were regressed separately on the independent variables, and also combined into a fear-of-crime index (Cronbach’s Alpha = .807; mean = 2.94; standard deviation (SD) = .872).

Crime victimization

The two items denoting crime victimization were measured as a dichotomous variable: Yes = 1; No = 0. (Cronbach’s Alpha value = .371; mean = .34; SD = .586). The two survey items were: (1) Have you been a victim of crime in your home community in the past 12 months? (2) Have you been a victim of crime at school in the past 12 months? Because of the low Cronbach’s Alpha value, these two items were employed separately in the regression analyses (see Tables 3, 4, 5).

Incivility

Incivility was measured using 1 item. A four-point Likert-type scale—(1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) agree, and (4) strongly agree—was employed to measure this independent variable. The scale was coded so that higher scores reflected higher levels of incivility. The survey item was: Drug use is a major cause of crime in KenyaFootnote 3 (mean = 3.23; SD = .773).

Gender: Gender was measured as: Male = 1; Female = 0.

Age: Age was measured as a continuous variable.

Control variables

The following control variables—educational level and housing type—were employed in the current study, because of “their association with fear of criminal victimization reported in past research” (Fisher and May 2009, p. 310).

Educational level: This variable was recoded into first-year; sophomore or higher. It was measured as: First-year = 1; Sophomore or higher = 0.

Housing type: This variable was measured as: On-campus = 1; Off-campus = 0. We hypothesize that housing type—off-campus or on-campus—would have an effect on college students’ fear of crime. Living off-campus may carry a higher risk of victimization, and hence an increased fear of crime, because of the high levels of gang and other criminal activity in Nairobi, as noted in the literature review section. On the contrary, we posit that the students living on-campus would have a lower fear of crime because college campuses tend to act as a cocoon, thus “shielding” students from the “ravages” of inner-city crime. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the variables.

Appropriate tests and analytic strategy

Preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure that there was no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity. The absence of outliers was also checked by inspecting the Mahalanobis distances. Tolerance and VIF values, for example, were all within acceptable ranges (Pallant 2010). Finally, from Table 2, none of the correlations between the dependent and independent variables, and between any two independent variables exceeded .70 (Pallant 2010), so all of the independent variables and the dependent variables were retained for analysis. Hierarchical multivariate regression was employed to test the relationships among the variables.

Results of regression analyses

Table 3 presents results from three Ordinary Least-Squares (OLS) regression models. In this table, the individual item, fear of crime at school, is the dependent variable. In Model 1, the effects of the control variables (housing type and educational level) and the independent variables (age and gender) on fear of crime at school were tested. In other words, Model 1 regressed fear of crime at school on housing type, educational level, age, and gender. The model is statistically significant and explains 3%Footnote 4 of the variation in fear of crime at school. The results suggest that older respondents had more fear of crime at school (β = .115, p < .05). Also, males had less fear of crime at school than their female counterparts (β = − .142, p < .05).

In Model 2, all the variables in Model 1 were retained and incivility added to the regression model. The model is statistically significant and explains 4% of the variation in fear of crime at school. Once again, older respondents had more fear of crime at school (β = .117, p < .05). Also, males were less fearful of crime at school than were females (β = − .131, p < .05). Finally, the more respondents believe that drug use is a major cause of crime in Kenya, the more likely they were to hold higher levels of fear of crime at school (β = .1, p < .05). In Model 3, all the variables in Model 2 were retained and crime victimization at school added to the regression equation. The model is statistically significant and explains 6% of the variation in fear of crime at school. Similar to results from Models 1 and 2, older respondents were more fearful of crime at school (β = .116, p < .05), male respondents had less fear of crime at school than female respondents (β = − .135, p < .05), respondents who believe that drug use is a major cause of crime in Kenya were more likely to hold greater levels of fear of crime at school (β = .123, p < .05), and respondents who had suffered prior victimization at school were more fearful of crime at school (β = .147, p < .05).

Table 4 presents results from three OLS regression analyses. In this table, the individual item, fear of crime in the community, is the dependent variable. Model 1 regressed fear of crime in the community on housing type, educational level, age, and gender. The model is statistically significant and explains 2% of the variation in fear of crime in the community. The results suggest that male respondents had lower levels of fear of crime than female respondents (β = − .134, p < .05). In Model 2, incivility was added to the model. The model is statistically significant and explains 3% of the variation in fear of crime in the community. Once again, gender was the only predictor variable that was statistically significantly related to fear of crime in the community: male respondents had lower levels of fear of crime in the community than their female counterparts (β = − .125, p < .05). In Model 3, crime victimization in the community was added to the regression model. The model is statistically significant and explains 4% of the variation in fear of crime in the community. The results show that male students were less likely to be fearful of crime compared to female students (β = − .130, p < .05), respondents who believe that drug use is a major cause of crime in Kenya were more likely to hold greater levels of fear of crime in the community (β = .089, p < .05), and respondents who reported a prior victimization in the community were more fearful of crime in the community (β = .118, p < .001).

In Table 5, the composite measure of fear of crime is the dependent variable. In other words, we attempted to capture the respondents’ overall fear of crime. In Model 1, overall fear of crime was regressed on housing type, educational level, age, and gender. The model is statistically significant and explains 3% of the variation in overall fear of crime. The results suggest that older respondents had higher levels of overall fear of crime (β = .095, p < .05). Also, males were less likely to be fearful of crime overall (β = − .153, p < .05). In Model 2, incivility was added to the regression equation. The model is statistically significant and explains 4% of the variation in overall fear of crime. Here, too, older respondents were more fearful of crime overall (β = .098, p < .05), and males were less likely than were females to be fearful of crime overall (β = − .142, p < .05). Also, those respondents who believe that drug use is a major cause of crime in Kenya were more likely to be fearful of crime overall (β = .104, p < .05).

In the third model, crime victimization at school was added to the regression equation. The model is statistically significant and explains 6% of the variation in overall fear of crime. Once again, older respondents had higher levels of overall fear of crime (β = .099, p < .05), males were less likely than were females to be fearful of crime overall (β = − .145, p < .05), and respondents who believe that drug use is a major cause of crime in Kenya were more likely to be fearful of crime overall (β = .114, p < .05). Finally, respondents who noted that they had been victimized at school in the past held higher levels of overall fear of crime (β = .148, p < .05).

In the fourth model, crime victimization in the community was added to the regression equation. The model is statistically significant and explains 7% of the variation in overall fear of crime. Once again, older respondents had higher levels of overall fear of crime (β = .107, p < .05), males were less likely than were females to be fearful of crime overall (β = − .153, p < .05), and respondents who believe that drug use is a major cause of crime in Kenya were more likely to be fearful of crime overall (β = .114, p < .05). Finally, respondents who had been victimized at school in the past (β = .126, p < .05) and respondents who had been victimized in the community in the past (β = .097, p < .05) held higher levels of overall fear of crime.

As with empirical research generally, this study also has limitations. First, because this study examined the correlates of fear of crime on a single university campus in Kenya, caution is required before generalizing the findings to all university campuses in Kenya. Second, we employed cross-sectional data, which means that we cannot infer causal relationships from the regression results. Causality can be determined through the use of a longitudinal study to measure the same concepts in the same Kenyan student population. Finally, our survey research was limited by the types of questions posed to respondents. For example, the use of a number of single-item measures may have affected the robustness of the findings, although we believe that this study’s findings contribute immensely to knowledge about fear-of-crime research in sub-Saharan Africa. To strengthen the validity and reliability of measures, we recommend that future research studies on fear of crime in sub-Saharan Africa employ more robust, multidimensional measures than those employed in the current study.

Discussion and conclusion

This study addressed the fear of crime on a Kenyan university campus. Based on available literature, this is the first research study by U.S.-based scholars to look at fear of crime on a college campus in Kenya. Studies in the extant criminological literature point to a statistically significant relationship between crime victimization and fear of crime, and this study is an attempt to add to the literature on fear of crime, although the study was carried out in a geopolitical context that is different from many of the current studies available in the literature. We argue that comparative studies must be carried out in several geopolitical contexts to increase scholars’ understanding of fear of crime.

Although we tested a composite fear-of-crime index, we also examined fear of crime at school and fear of crime in the community separately to shed more light on any fear-of-crime differences based on physical location. From Tables 3, 4, and 5, crime victimization predicted fear of crime, irrespective of whether fear of crime was measured as a single item (as in Tables 3 and 4) or as a composite index (as in Table 5). These statistically significant relationships point to the strong link between crime victimization and fear of crime, and are similar to findings from studies conducted in the United States (Bachman et al. 2011; Ferguson and Mindel 2007; Skogan 1987). Compared to victimization in the community, victimization at school was a stronger predictor of overall fear of crime (see Table 5). This finding was not unexpected because, as we noted earlier in this paper, school campuses may act as a cocoon, thereby shielding students from the “ravages” of inner-city crime. Thus, a student victimized on campus is expected to feel even less safe in the larger community, where the “protective shield” from crime is expected to be weaker overall (Volkwein et al. 1995). This finding also strengthens the argument for improved security on this Kenyan college campus.

It appears that the findings of the current study provide answers to the four research questions put forth earlier in this paper: Gender, age, crime victimization, and incivility are important antecedents of fear of crime in this sample of Kenyan college students. This study’s findings add to the literature on the relationship between gender and the fear of crime (Fox et al. 2009; McCreedy and Dennis 1996; Warr 2000). Not unlike results from prior studies, females are more fearful of crime than are males (Baumer 1985; Fisher 1995; Fox et al. 2009; Gibson et al. 2002; Perkins and Taylor 1996; Will and McGrath 1995), even though women are less likely to be victimized compared to men (Lab 2016). What is interesting about our results is that gender was statistically significantly related to fear of crime in all ten regression models tested. Thus, we argue that these findings are robust, and confirm the near-universality of fear of crime being higher among females than males.

In answering our second research question, we note that older respondents had greater levels of fear of crime at school and greater levels of fear of crime overall. These findings mirror the findings from prior research on the relationship between age and fear of crime (Ferraro 1995; Fox et al. 2009; Gibson et al. 2002; McGarrell et al. 1997). Scholars have posited that age is positively correlated with fear of crime because older persons are generally more vulnerable to crime (McGarrell et al. 1997).

In answering our third research question, we note that prior victimization at school and prior victimization in the community were statistically significantly related to fear of crime in all the regression models. Once again, we argue that these findings are quite robust, and generally support findings from research studies carried out in other geopolitical contexts (Bachman et al. 2011; Baumer 1985; Bennett and Flavin 1994; Ferguson and Mindel 2007; Ferraro and LaGrange 1987; Roundtree 1998; Skogan 1987; Tseloni and Zarafonitou 2008; Will and McGrath 1995). Of course, it is reasonable to expect that people who had suffered victimization in the past would be more fearful of crime, and this finding extends to sub-Saharan Africa as well. This finding thus points to the need for greater security on this Kenyan college campus and in the larger community.

We address the fourth research question by noting that perceived incivility was statistically significantly related to fear of crime in six of seven regression models. This finding is similar to what other researchers had found in a different geopolitical context (Bachman et al. 2011; Box et al. 1988; LaGrange et al. 1992; Lane and Fox 2012; Lane and Meeker 2011; Lewis and Maxfield 1980; McGarrell et al. 1997). This result is intuitive because it taps into the issue of disorder in the community, which in turn is expected to increase students’ fear of crime. Relatedly, it is important that administrators at this Kenyan university address any issues of incivility on campus, in order to lower the levels of fear of crime among students.

To conclude, we reiterate the importance of our study, as campus security is important to both university leaders and students everywhere, not just in the United States. Understanding the correlates of fear of crime in different geopolitical contexts would allow scholars to proffer practical solutions to help provide better security on college campuses. We encourage other researchers to pursue fear-of-crime studies on college campuses in other African nations to increase understanding of the concept of fear of crime.

Policy implications

The current study shows that female students have higher levels of fear of crime than male students, which points to a greater need for increased protection around female dormitories or residence halls on campus. With fairly predictable on-campus activities (e.g., specific lecture times during the day or at night), students, especially female students, need to feel safe on campus, considering the fact that this university experienced more than 100 crimesFootnote 5 in the most recent year for which data are available. The feeling and assurance of safety may also impact female students’ willingness to enroll in a particular university, which is why student safety cannot be overemphasized. We recommend that Kenyan universities establish their own police departments, to be staffed by fully trained, firearms-carrying officers. Although the university in question currently employs security officers to oversee campus security, we argue that uniformed police officers would deter criminal activity better and increase feelings of safety among students, especially female students. For example, Fisher and May (2009) found that “the presence of police may be more relevant for decreasing fear of crime among females than males” (p. 317). In addition, university campuses can organize regular meetings (e.g., crime prevention seminars) for students to inform them about how to better protect themselves on campus, thus reducing their chances of falling victim to predatory acts. The crime-avoidance lessons learned from these regular meetings would also be useful when the students travel to the larger community. Because a single violent crime can easily tarnish a university’s reputation and sow seeds of doubt about personal safety in the minds of current and prospective students, campus safety is germane to what universities do: engage in higher learning and research to make society a better place for all.

Notes

This is important, not only because it is a study conducted in Kenya, but because the plurality of fear-of-crime studies are based in Western democracies. Moreover, the globalization of criminological research and collaborations among researchers from different geopolitical regions are improving knowledge about crime and how to prevent it.

This conceptualization mirrors Bachman et al.’s (2011) conceptualization of fear of crime.

Our conceptualization of incivility is similar to that of Reisig and Parks’ (2000) conceptualization of the same variable. Their incivility scale was a composite measure of the extent of neighborhood problems, and was measured with the following responses: not a problem; minor problem; and major problem.

Although the R Square values are low in all three tables in the current study, these numbers are not unusual in fear-of-crime research studies (see, for example, Jackson 2009).

The official number of reported crimes may be less than the actual number, as research shows that not all crimes are reported to the authorities (see, for example, Fisher et al. 2002). This argument only increases the need for greater security for students, especially females.

References

Akech, J.M. 2005. Public Law Values and the Politics of Criminal (Injustice): Creating a Democratic Framework for Policing in Kenya. Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal 5 (2): 225–256.

Bachman, R., A. Randolph, and B.L. Brown. 2011. Predicting Perceptions of Fear at School and Going to and From School for African American and White Students: The Effects of School Security Measures. Youth & Society 43 (2): 705–726.

Barberet, R., B.S. Fisher, and H. Taylor. 2004. University Student Safety in the East Midlands. London: Home Office, Home Office Outline Report.

Baumer, T.L. 1985. Testing a General Model of Fear of Crime: Data From a National Survey. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 22: 239–255.

Bennett, R.R., and J.M. Flavin. 1994. Determinants of Fear of Crime: The Effect of Cultural Setting. Justice Quarterly 11: 357–382.

Box, S., C. Hale, and G. Andrews. 1988. Explaining Fear of Crime. British Journal of Criminology 28: 340–356.

Cao, L., J. Frank, and F.T. Cullen. 1996. Race, Community Context, and Confidence in the Police. American Journal of Police 15: 3–22.

Chiricos, T.G., M. Hogan, and M. Gertz. 1997. Racial Composition of Neighborhood and Fear of Crime. Criminology 35: 301–324.

Cohen, M.A. 2008. The Effect of Crime on Life Satisfaction. Journal of Legal Studies 37 (2): 325–353.

Covington, J., and R.B. Taylor. 1991. Fear of Crime in Urban Residential Neighborhoods: Implications of Between-and-Within-Neighborhood Sources for Current Modes. Sociological Quarterly 32: 231–249.

Craven, D. 1997. Sex Differences in Violent Victimization, 1994. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS).

Dai, M., and R.R. Johnson. 2009. Is Neighborhood Context a Confounder? Exploring the Effects of Citizen Race and Neighborhood Context on Satisfaction with the Police. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 32 (4): 595–612.

Dao, T. K., Kerbs, J. J., Rollin, S. A., Potts, I., Gutierrez, R., Choi, …Prevatt, F. 2006. The Association Between Bullying Dynamics and Psychological Distress. Journal of Adolescent Health 39: 277–282.

Davies, S., and T. Hinks. 2010. Crime and Happiness Amongst Heads of Households in Malawi. Journal of Happiness Studies 11 (4): 457–476.

Day, K. 1994. Conceptualizing Women’s Fear of Sexual Assault on Campus. Environment and Behavior 26: 742–767.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R., and Nopo, H. 2008. Happiness and Beliefs in Criminal Environments. RES Working Paper No. 4605, Inter-American Development Bank.

DuBow, F., McCabe, E., and Kaplan, G. 1979. Reactions to Crime: A Critical Review of the Literature. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Ferguson, K.M., and C.H. Mindel. 2007. Modeling Fear of Crime in Dallas Neighborhoods: A Test of Social Capital Theory. Crime & Delinquency 53: 322–349.

Ferraro, K.F. 1995. Fear of Crime: Interpreting Victimization Risk. Albany: SUNY Press.

Ferraro, K.F., and R.L. LaGrange. 1987. The Measurement of Fear of Crime. Sociological Inquiry 57: 70–101.

Fisher, B.S. 1995. Crime and Fear On Campus. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 539: 85–101.

Fisher, B.S., and D. May. 2009. College Students’ Crime-Related Fears on Campus: Are Fear-Provoking Cues Gendered? Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 25 (3): 300–321.

Fisher, B.S., and J.J. Sloan. 2003. Unraveling the Fear of Victimization Among College Women: Is the “Shadow of Sexual Assault Hypothesis” Supported? Justice Quarterly 20 (3): 633–659.

Fisher, B.S., J.J. Sloan, and D.L. Wilkins. 1995. Fear of Crime and Perceived Risk of Victimization in an Urban University Setting. In Campus Crime: Legal, Social, and Policy Perspectives, ed. B.S. Fisher, and J.J. Sloan. Springfield, IL: Charles Thomas Publishing.

Fisher, B.S., J.L. Hartman, F.T. Cullen, and M.G. Turner. 2002. Making Campuses Safer for Students: The Clery Act as a Symbolic Legal Reform. Stetson Law Review 32: 61–89.

Fox, K.A., M.R. Nobles, and A.R. Piquero. 2009. Gender, Crime Victimization, and Fear of Crime. Security Journal 22: 24–39.

Garofalo, J. 1979. Victimization and the Fear of Crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 16: 80–97.

Gastrow, P. 2011. Termites at Work: Transnational Organized Crime and State Erosion in Kenya. New York: International Peace Institute.

Gibson, C.L., J. Zhao, N.P. Lovrich, and M.J. Gaffney. 2002. Social Integration, Individual Perceptions of Collective Efficacy, and Fear of Crime in Three Cities. Justice Quarterly 19 (3): 527–567.

Hilinski, C.M. 2009. Fear of Crime Among College Students: A Test of the Shadow of Sexual Assault Hypothesis. American Journal of Criminal Justice 34: 84–102.

Jackson, J. 2009. A Psychological Perspective on Vulnerability in the Fear of Crime. Psychology, Crime & Law 15 (4): 365–390.

Klopp, J., and P. Kamungi. 2008. Violence and Elections: Will Kenya Collapse? World Policy Journal 24 (4): 11–18.

Lab, S. P. 2016. Crime Prevention: Approaches, Practices, and Evaluations (9th ed.) New York: Routledge.

LaGrange, R.L., K.F. Ferraro, and M. Supancic. 1992. Perceived Risk and Fear of Crime: Role of Social and Physical Incivilities. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 29: 311–334.

Lane, J., and K. Fox. 2012. Fear of Crime Among Gang and Non-Gang Offenders: Comparing the Effects of Perpetration, Victimization, and Neighborhood Factors. Justice Quarterly 29: 491–523.

Lane, J., and J.W. Meeker. 2011. Combining Theoretical Models of Perceived Risk and Fear of Gang Crime Among Whites and Latinos. Victims and Offenders 6: 64–92.

Lane, J., N.E. Rader, B. Henson, B.S. Fisher, and D.C. May. 2014. Fear of Crime in the United States: Causes, Consequences, and Contradictions. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

Lauritsen, J.L., and K. Heimer. 2008. The Gender Gap in Violent Victimization, 1973-2004. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 24 (2): 125–147.

Lee, D.R., and C.M. Hilinski-Rosick. 2012. The Role of Lifestyle and Personal Characteristics on Fear of Victimization Among University Students. American Journal of Criminal Justice 37: 647–668.

Lewis, D.A., and M.G. Maxfield. 1980. Fear in the Neighborhoods: An Investigation of the Impact of Crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 17: 160–189.

Lumb, R. C., Hunter, R. D., & McLain, D. J. 1993. Fear Reduction in the Charlotte Housing Authority. In Proceedings of the International Seminar on Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis, eds. D. Zahm, and P. Cromwell. Coral Gables, FL: Florida Criminal Justice Executive Institute.

McCreedy, K., and B. Dennis. 1996. Sex-Related Offenses and Fear of Crime on Campus. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 12 (1): 69–90.

McGarrell, E.F., A.L. Giacomazzi, and Q.C. Thurman. 1997. Neighborhood Disorder, Integration, and the Fear of Crime. Justice Quarterly 14: 479–500.

Moller, V. 2005. Resilient or Resigned? Criminal Victimization and Quality of Life in South Africa. Social Indicators Research 72 (3): 263–317.

Osse, A. 2007. Understanding Policing, A Resource for Human Rights Activists. Amsterdam: Amnesty International.

Osse, A. 2016. Police Reform in Kenya: A Process of “Meddling Through”. Policing and Society 26 (8): 907–924.

Pallant, J. 2010. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS, 4th ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

Perkins, D.G., and R.B. Taylor. 1996. Ecological Assessments of Community Disorder: Their Relationship to Fear of Crime and Theoretical Implications. American Journal of Community Psychology 24: 63–107.

Powdthavee, N. 2005. Unhappiness and Crime: Evidence From South Africa. Economica 72 (3): 531–547.

Pryce, D. K. 2016a. Does Procedural Justice Influence General Satisfaction With Police? A Study From A Hard-To-Reach Population of Immigrants in the United States. Journal of Crime and Justice. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648x.2016.1193820.

Pryce, D.K., D. Johnson, and E.R. Maguire. 2017. Procedural Justice, Obligation to Obey, and Cooperation with Police in a Sample of Ghanaian Immigrants. Criminal Justice and Behavior 44 (5): 733–755.

Quann, N., and Hung, K. 2002. Victimization experience and the fear of crime. A cross-national study. In: Crime Victimization in Comparative Perspective. Results from the International Crime Victims Survey, 1989–2000, ed. P. Nieuwbeerta, 301–316. The Hague: NSCR, BJU.

Reisig, M.D., and R.B. Parks. 2000. Experience, Quality of Life, and Neighborhood Context: A Hierarchical Analysis of Satisfaction with Police. Justice Quarterly 17 (3): 607–630.

Reisig, M.D., J. Bratton, and M. Gertz. 2007. The Construct Validity and Refinement of Process-Based Policing Measures. Criminal Justice and Behavior 34: 1005–1027.

Roundtree, P.W. 1998. A Reexamination of the Crime-Fear Linkage. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 35: 341–372.

Ruteere, M. 2011. More Than Political Tools: The Police and Post-Election Violence in Kenya. African Security Review 20 (4): 11–20.

Ruteere, M., and M. Pommerolle. 2003. Democratizing Security or Decentralizing Repression? The Ambiguities of Community Policing in Kenya. African Affairs 102: 587–604.

Schafer, J.A., B.M. Huebner, and T.S. Bynum. 2006. Fear of Crime and Criminal Victimization: Gender-Based Contrasts. Journal of Criminal Justice 34: 285–301.

Skogan, W.G. 1987. The Impact of Victimisation on Fear. Crime and Delinquency 33: 135–154.

Skogan, W.G., and M.G. Maxfield. 1981. Coping With Crime: Individual and Neighborhood Differences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publishing.

Starkweather, S. 2007. Gender, Perceptions of Safety, Perceptions of Safety and Strategic Responses Among Ohio University Students. Gender, Place, and Culture 14: 355–370.

Sulemana, I. 2015. The Effect of Fear of Crime and Crime Victimization on Subjective Well-Being in Africa. Social Indicators Research 121: 849–872.

Tabachnick, B.G., and L.S. Fidell. 2007. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

Tankebe, J. 2008. Police Effectiveness and Police Trustworthiness in Ghana: An Empirical Appraisal. Criminology and Criminal Justice 8 (2): 185–202.

Tseloni, A., and C. Zarafonitou. 2008. Fear of Crime and Victimization a Multivariate Multilevel Analysis of Competing Measurements. European Journal of Criminology 5 (4): 387–409.

Tyler, T.R., J. Jackson, and A. Mentovich. 2015. The Consequences of Being An Object of Suspicion: Potential Pitfalls of Proactive Police Contact. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 12 (4): 602–636.

Volkwein, J.F., B.P. Szelest, and A.J. Lizotte. 1995. The Relationship of Campus Crime to Campus and Student Characteristics. Research in Higher Education 36: 647–670.

Warr, M. 2000. Fear of Crime in the United States: Avenues for Research and Policy. In Measurement and Analysis of Crime: Criminal Justice 2000, ed. D. Duffee. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs.

Weitzer, R., and S.A. Tuch. 2002. Perceptions of Racial Profiling: Race, Class, and Personal Experience. Criminology 40 (2): 435–456.

Weitzer, R., and S.A. Tuch. 2005. Determinants of Public Satisfaction With the Police. Police Quarterly 8: 279–297.

Wilcox, P., C.E. Jordan, and A.J. Pritchard. 2007. A Multidimensional Examination of Campus Safety: Victimization, Perceptions of Danger, Worry About Crime, and Precautionary Behavior Among College Women in the Post-Clery Era. Crime and Delinquency 53 (2): 219–254.

Will, J.A., and J.H. McGrath. 1995. Crime, Neighborhood Perceptions, and the Underclass: The Relationship Between Fear of Crime and Class Position. Journal of Criminal Justice 23: 163–176.

Acknowledgements

We thank the journal’s editor and the anonymous reviewers for their tremendously helpful comments, which helped to strengthen the arguments proffered in this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pryce, D.K., Wilson, G. & Fuller, K. Gender, age, crime victimization, and fear of crime: findings from a sample of Kenyan College students. Secur J 31, 821–840 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-018-0134-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-018-0134-5