Abstract

Weight cycling, the process of losing and then gaining weight repeatedly, is presented negatively in both the mainstream obesity and critical health studies literature. In this paper, I present an alternative perspective through the use of Lacanian psychoanalytic theory coupled with the qualitative method of autotheory. Specifically, I contest the notion of weight maintenance, suggesting instead that repeated weight loss and gain can be seen as the maintenance of the subject’s desire – something that has an ethical basis in psychoanalytic terms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Biomassochism: The act of punishing oneself with one’s biomass and enjoying it; usually involving bathroom scales.

For more than a decade, I have been reading and writing about weight loss as a repetitive pattern that exerts an influence across one’s life, even intergenerationally (Winship and Knowles, 1996; Arroyo et al., 2017). I have determined that attempting to lose weight is a fraught process, riddled with what seems like perpetual success and failure, with all sorts of nasty consequences. This should come as no surprise, as even a cursory glimpse at the world reveals a kaleidoscope of trauma in and around weight practices (Bacon and Aphramor, 2011; Bombak and Monaghan, 2017; Dickson, 2011; Throsby, 2009).

My scholarly work has revolved around trying to critique the industry that creates what I have previously called the ‘weight-anxious consumer’ (Dickson, 2011, 2015b; Warbrick et al., 2016). This industry achieves its surpluses through the repeated (failed) attempts of the consumer to lose weight. Despite my extensive reading, thinking, and talking in this area, the pull for me, too, to lose weight is undiminished, encoded, as it must be for many of us, in lalangue (McConnell and Gillett, 2005). As Lacan (1973/1998) writes:

Llanguage [lalangue] serves purposes that are altogether different from that of communication. That is what the experience of the unconscious has shown us, insofar as it is made of llanguage, which, as you know, I write with two l’s to designate what each of us deals with, our so-called mother tongue, which isn’t called that by accident. (p. 138)

What am I to do about the intractability of the pull to lose weight, that insists on making itself known even when I should be able to let it go, even when the doctors and scientists tell me ‘You’re just a BIG GUY. You’re fit and healthy, don’t worry!’? I’m still worried. You are probably worried too.

In this paper, I am attempting to deploy writing differently (Sayers, 2016) as an academic method, to move away from the form and function of traditional academic writing to embrace the emotionality of the one who desires to write, and about themself (Rickard, 2009; Longhurst, 2012; Dickson, 2015a; Ruth et al., 2018). My aim here is not only to write in line with the existing literature, particularly autoethnography and autobiography, but also to extend it in the broad direction of autotheory (Nelson, 2015; Ruti, 2018), that most intriguing of ‘postructural methods’ (Kaufmann, 2005, p. 576).

Second, and relatedly, I want to work towards crushing the myopic motivation deployed in the wider world of weight loss and ‘obesity’ research, that is to force people into futile weight loss attempts to excise the ‘obese’ from our society, as so many before me have also attempted (Aphramor, 2005; Gard and Wright, 2005; Guthman and DuPuis, 2006; Pausé, 2017).

Third, and most important, I want to introduce a Lacanian reading of the ethics of desire in relation to weight loss—a theory that gives the weight-anxious a chance to recognise their repeated attempts to lose weight within an ethic of desire. Almost exclusively, weight cycling is viewed by mainstream obesity scholars as a failure to maintain weight loss (see, for example, Feller et al., 2015). This is also the case in the critical social sciences, though in a more nuanced and sensitive fashion (see Bombak and Monaghan, 2017, p. 934 ff.). I present an alternative to the negativity with which weight cycling is viewed by questioning what Bombak and Monaghan would call the ‘stalled future’ (p. 934) that comes with repeated attempts to lose weight.

This paper has two parts, as well as this current introduction. The following section is an autotheoretical text on my weight cycling, aiming to capture some of the lalangue I refer to above. Therefore, I attempt to write associatively, to follow my desire. The final section is a Lacanian analysis of my perceived failed weight loss attempts, which aims to demonstrate that there is an ethics of desire in these attempts, as well as in the ways in which they are related to masochism and the position of the anorexic subject.

From the biomassochist

But basking in the punk allure of [Lee Edelman’s] ‘no future’ won’t suffice, either, as if all that’s left for us to do is sit back and watch while the gratuitously wealthy and greedy shred our economy and our climate and our planet, crowing all the while about how lucky the jealous roaches are to get the crumbs that fall from their banquet. Fuck them, I say. (Nelson, 2015, p. 95)

But, also, really Lee Edelman’s middle finger No! ‘can bring relief to subjects who experience their encounters with the symbolic establishment as tyrannical and wounding: not giving a damn about what the Other wants can be liberating for those who have been subjected to the unjust laws of this Other’ (Ruti, 2018, p. 64).

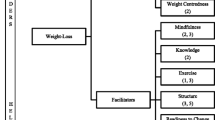

Do you ever wish you had written the words you just read? I do, reading these paragraphs. It seems to me that the anti-normative ethic contained in them frames the entire fat activist/body positivity movement. I think the idea is that, rather than just turning away from, obscuring, or refuting the normativity of the big Other and the dogma of the Body Mass Index, instead just ram the normativity up their arse by flaunting your (perceived) obscenity, your fat body. But, it doesn’t really work that way, does it? (Fig. 1).

Analysing the above photograph (and caption) is a complicated undertaking, personally and sociologically. Longhurst (2012) said ‘for the last couple of years I have wrestled with critiquing discourses around women and slimness while desiring to be slim’ (p. 9). For me, this has been the case for what feels like a lifetime. There can be no peace between the body and me; it is my battleground.

However, as a scholar, I must make some important decisions, particularly around where to start from, theoretically. There are many options. One could approach it as a visual exercise. The subject has his hands up in a classic boxing cover; hand wraps are present; there are heavy bags hanging in the background; exercise gear is worn. One could also analyse the text: the subject appears not to be in a positive frame of mind. A scholar of critical theory might be tempted to situate the vignette historically. It is 2020; the subject is a white male, balding, approaching middle age, if not already there. He was probably born in the 1970s. If so, he grew up in the cradle of neoliberalism – the age of individual responsibility – and here he stands, putting his body on the line in pursuit of wellbeing. His next stop may well be a mindfulness webinar. This is a docile body; he even loves/hates it, as society expects him to. He is working on himself. Caring for himself, but not so much taking care of his self (Foucault, 1986/2012). He is a paradox.

‘In Foucauldian feminist analysis, dieting is understood as a disciplinary practice that serves to construct “docile bodies”’ (Heyes, 2006, p. 132). Except when that body is your mOther. I mean, what could be less docile than that? A Freudian slip is when you say one thing but mean your Mother. A Freudian slip is when you say one thing but mean your Mother. Is this ‘repetition for emphasis’, as we were told at school, or just repetition? My Mother was a teacher; she taught me about unruly bodies. Like Nelson (2015) said,

This comes as no real surprise–my mother and her entire family line are obsessed with skinniness as an indicator of physical, moral, and economic fitness. My mother’s [desire for a] skinny body, and her lifelong obsession with having zero fat […] Look how fat everyone is, my mother says, her mouth agape, whenever […] A writer is someone who plays with the body of his mother. (p. 131)

I have not, of my own free will, stepped on a set of bathroom scales since 2011. Despite this, I know what I weigh. I know because most of us know. It is a basic aspect of living in a society of scales. We know what we weigh, how big our feet are, how many teeth we have lost. We even know our approximate IQ scores. We are scaled. Our little babies are scaled instantly upon detection, six weeks pregnant, second trimester, bone-length comparison, birth weight. You can even define a newborn baby as clinically obese. ‘Fat and happy’ was the old definition.

Starving is complicated. Starving your children is frowned upon in middle-class parenting circles, but starving yourself is fabulous! Having been practising for a while now, I can comfortably starve myself for 24 hours and still remain entirely functional – in fact, I run faster fasted. And that emptiness. Apparently, I am doing my body an immense favour; there are a multitude of physiological and psychological benefits. Does this calculation work: Physiology + psychology = Andy? If so, I think I may well have the answer – ‘STOP EATING, FATSO.’ ‘Alternatively, it [starving] can lead to anorexia and bulimia, those failed suicidal consequences of the “refusal of femaleness”’ (Kristeva, 2004, p. 66).

And doesn’t Kristeva really capture the law here, as she explains the b(l)ind the little girl/woman navigates as opposed to the little boy?

[W]hen the female subject manages to accomplish the complex tourniquet imposed on her by the primary and secondary oedipal phases, she can have the good fortune to acquire that strange maturity that the man so often lacks, buffeted as he is between the phallic pose of the ‘macho’ and the infantile regression of the ‘impossible Mr. Baby’ (p. 66).

Is this why I was in therapy/analysis? Trying to negotiate between the strong anorexic pull that fasting gives me a moral right to approach, and the constant buffeting between the phallic pose of the ‘macho’ and the infantile regression of the ‘impossible Mr. Baby’.

Some time ago I valiantly explained to a distinguished colleague that I was currently writing ‘autotheory’. It was equal parts bravado and desire (one cannot but imagine how Kristeva might explain my buffeting here). She commented that if I did (I do have a habit of the incomplete) I might be the first man to do so … these are now my words: As currently autotheory is women’s business, maybe it is an effect of that strange maturity?

Kristeva also unashamedly interprets Lacan; she is not his groupie. But neither does she back away from ‘Lacan’s heavy-handed Imaginary and Symbolic’ (Nelson, 2015, p. 23). My problem is I want the hand to be heavy – maybe because my father’s hand never was. It’s not that I wanted to be subject to Freud’s primal father in any sense of the reality of human experience, but the absence of the names-of-the-father does seem to play on me.

Summer is coming. Amongst the ever-changing spring weather, we can sense the warmth just around the corner. New Zealand gets lazy in summer, particularly after Christmas, into the beginning of the new year. I spent many of my childhood summers easy/uneasy. Easy in the regional laziness, slow days, cicadas, swimming, sunburn. Uneasy because of ... Where, precisely, were the names-of-the-father? Am I imagining rescue? That I am immune, I suspect, was the logic that was unfurled. But this unfurling was preventable, perhaps not through the ingestion of the right organic tea, but through PG Tips, served alongside a box of Griffin’s Sampler biscuits, and a hard conversation.

A little over ten years ago, my mother, an old teaching friend of hers, and I went out to lunch at a library café in the town where I grew up. In the year previous to this lunch rendezvous, I had lost a LOT of weight, and one of my aging uncles had mistaken me for my brother, who is ‘naturally’ thin. I didn’t correct him – perverse I know – and we had an entire conversation in which I was the ‘right’ son. ‘Lunch with Mother’ is always precisely as bad as it sounds. The conversations are all about weight, even when they don’t seem to be. Sometimes though, weight erupts dramatically, as it did this time. ‘I’m waiting for him to revert back to his old ways’, my mother explained conspiratorially to her generously proportioned friend, right in front of me, literally as my food-laden fork was midway on its journey to my anticipating mouth. ‘It turns out that, under the circumstances, oral activity, which produces the linguistic signifier, coincides with the theme of devouring’ (Kristeva, 1982, p. 41). Now, I don’t want to get into the grist of mothers devouring their young, but you have to wonder at what point a mOther would allow for a shift, or, as the Lacanians might say, a traversing of the fundamental fantasy.

I can say that I did not let my mother down! Unruly as they all are, my body quietly rebels. Perhaps it is, as the scientists would prefer, that my biology is far more potent than my psychology. In this reality even you, reader, cannot outrun your genetics, forever subject to the taunts of the boys as you too approach the long-jump: ‘boomba, boomba, boomba, watch the fat boy run!’ So, you get back on the scales and then get yourself off.

I never tire of asking people about the conditions under which they weigh themselves. For many, it seems rather simple – when they remember, regardless of what is occurring about or within them. These people bore me. What I find fascinating are the people like me, the ones who have ritualised weighing. My ritual has involved NOT weighing myself but thinking about it A LOT. Prior to abandoning my casual sexual affair with the bathroom scales in 2011, I used to carefully plan the execution of ‘the weigh’. It was a daily task, completed during the morning hours. I would wake, ablute, run, shower, then carefully dry every morsel of water from my body and step stark naked onto the scale, looking down with phallic fascination, watching carefully as the numbers were calculated. Grams up, grams down from yesterday. Down = scales working accurately. Up = rinse and repeat, wash some more dead skin off the body, more ablutions, or perhaps more running, until down. ‘That’s about the size of it!’ says Anna. Accurately. About the size of ‘it’.

How many ways can a child ask for ice-cream? Ben is inventive when he wants to be, but mainly just insistent when begging for ice-cream. I give in. It is a warm day, summer heading into Christmas. Time marches on. Some months later, driving home from the paddock, Ben tells me that ice-cream may well be taking over from ‘bobbles’ as his favourite food. I quietly reflect on the years of formula preparation, of cleansing bottles and carefully weighing powder from a can, even while his little body writhed and groaned with pure HUNGER, screaming until the teat found his lips. He still drinks milk from a baby bottle almost 9 years later; he still uses the newborn teat, even. He must have a powerful suck, a paediatrician suggested some years ago. But perhaps the lick of an ice-cream is taking over. He doesn’t realise yet what that means.

I didn’t do well with babies and young children; it left an emotional toll on me. I never left, and I worked hard. My friend Craig once told me he couldn’t figure out how they managed to do all the work, now his kids have grown up and he looks back on the labour expended by all involved. Our babies were met with love, wonder, and anxiety, in approximately equal doses. But it all started with Ben; Lizzie came second. I am avoiding the temptation to represent my two beautiful kids in some kind of faux equality system. I love them separately and together; I signify them differently and do not apologise for this. During the drive home from school, the question arose: ‘Who do I love more?’ Lizzie said, ‘Ben, of course’; Ben said, ‘Ben’. He often speaks of himself in the third person. I am suspicious he wouldn’t understand the problem with the classic Lacanian grammar test ‘I have three brothers, Ernst, David and I’ (Žižek, 2002) (Fig. 2).

What do you see in this image? My first stop is not the tiny baby covered in wires, nasal oxygen replacing the recently removed breathing tube. My first stop is the skinny man: that man who both is and is not me. I remember that t-shirt, which was a ‘Large’. Would it be skin-tight now? Luckily, it is well-worn, ripped, and trashed, decomposing somewhere in a landfill, not sitting in my wardrobe, signifying something lost and gained.

The ethics of desire

I think it is clear that (weight) anxiety is the central affect of the autotheoretical passages above. Let me provide some history on my weight. My entire adult life has been an almost continuous cycle of weight loss and weight gain – from a low of around 90kg to a high of around 135kg, with constant weight oscillation around a mid-point (say, 115kg, give or take). I have never been inactive, sometimes running over 100km per week whilst training for marathons, other times sparring and pad-work in Muay Thai kickboxing or boxing gyms. I also eat really well – a wide variety of food, lots of good quality protein, generally low alcohol intake, very minimal mass-produced fast food. We have three large and productive vegetable gardens and easy access to grass-fed lamb, beef and fresh fish. It is hard to explain why my body has been smaller or bigger. Since there is no obvious place to point the finger, clinicians have generally pointed at ‘overeating’, despite that being an impossible thing to capture.Footnote 1

26 years ago, at the end of my first year at university, I lost 25kgs over the course of one summer whilst working for a furniture removal company. At the beginning of the summer, I was 125kg; by the time university started again, I was just over 100kg. I maintained that for only a year or so. In 2006, I lost 45kg. As a percentage of my ‘before’ weight, this was around 33% of my total body mass. It is now 2020, and I no longer weigh my lowest weight from 14 years ago, but nor am I at my highest. You might say that, at this point in time, I have lost 19% of my total ‘before’ weight, or you could as easily say that I have gained 22% from my ‘maintained’ lowest adult weight. Which is it? Am I a gainer or a loser? Am I achieving weight loss ‘maintenance’?

McGuire et al. (1999) would suggest so, as they were pretty impressed by those in their survey who had maintained a 10% weight loss or more for just one year. In Vink et al.’s (2016) trial, the subjects lost around 8kg and gained about half of it back after a nine-month follow-up. In terms of the world of weight loss research, four year follow-ups are rare, since funding cycles are almost never that long. But I am only 43 years old, approximately just halfway through my life – would ‘maintenance’ then need another couple of decades of weight continuity?

From the maintenance of weight loss to the maintenance of desire

I argue that ‘maintained’ is simply the wrong signifier to attach to weight loss. ‘Maintained’ signifies something that is a very long way from the reason behind the vast majority of weight loss attempts made in contemporary society. For a moment, imagine each ‘attempt’ as a discrete yet interconnected incidence of perceived body (dys)morphia across a person’s life span. What connects these attempts? How do the repeated attempts to radically re-shape one’s body make sense?

This is where psychoanalysis is useful for conceptualising human motivation that otherwise seems oblique, including that towards (repeatedly) reshaping one’s body. The concept of desire is critical here, in terms of its ability to repeat in one’s life even when we are not aware of it. ‘Desire is desire for desire’ (Lacan, 2006, p. 723). This enigma speaks to the notion of repetition: that integral to desire is this tendency we have to repeat patterns of relating to others throughout our lives in an unconscious attempt to ‘manage life’. ‘The constantly changing nature of life, Freud argues, demands a perpetual expenditure of energy by our understanding: repetition, then, the rediscovery of something already familiar, is pleasurable because it economizes energy’ (Copjec, 1992, p. 43). Copjec goes on to consider what must be one of the most critical discoveries by Freud (1920/1955a): that the compulsion to repeat is inextricably linked to the death drive, which for Lacan is not in opposition to the pleasure principle but rather an elaboration of it.

The problem with the ‘maintenance of weight loss’ literature is that it just does not understand what is also lost when one loses weight: the potentiality that a large body contains; the potential to lose weight in the first place. We often talk of how people procrastinate in their diet strategies, of their masochistic delaying of what they find most pleasurable: the dropping of the numbers on the scale. This delay

[i]n Lacan (following Freud) [needs to be] understood as prolonging the pleasures of language; it introduces the reality principle, which psychoanalysis defines as that which delays the pleasure principle, or which maintains desire beyond the threats of extinction presented by satisfaction. The death drive does not negate the pleasure principle, it extends it. (Copjec, 1992, p. 54)

The sad irony is that, for most of us, the satisfaction gained from weight loss carries with it a ‘threat of extinction’ (speaking symbolically): an extinction of desire under the grind of the drives. This is not something the subject can stand for long; weight must be regained in order to restore the potentiality stored in one’s body and maintain desire. With this frame I argue that it is not weight loss that is being maintained – it is desire itself – when we weight cycle.

There is an unmistakeable ethic in any strategy that maintains desire. In his seminar on ethics, Lacan (1986/1992) says ‘from an analytic point of view, the only thing one can be guilty of is having given ground relative to one’s desire’ (p. 319). Thus, if one’s desire requires repeated weight loss/weight gain cycles (as it has for me), then we must work with that. We can learn more from an extensive reading of the context of Lacan’s statement above.

Let’s take this further. He has often given ground relative to his desire for a good motive or even the best of motives. And this shouldn’t astonish us. For guilt has existed for a very long time, and it was noticed long ago that the question of a good motive, a good intention, although it constitutes certain zones of historical experience and was at the forefront of discussions of moral theology in, say, the time of Abelard, hasn’t enlightened people very much. The question that keeps reappearing in the distance is always the same. And that is why Christians in their most routine observances are never at peace. For if one has to do things for the good, in practice one is always faced with the question: for the good of whom? From that point on, things are no longer obvious. (p. 319)

This raises the question: For whom am I losing weight? Or, for the good of whom? For, let us be very clear, I am losing it. Lacan’s point here sweeps us up in a vortex of impossibility, in which, as we give ground to our desire by attempting to be a good (thin) subject, we observe the Other observing us in all its convoluted, specular, and paradoxical glory. I (we) determine that it is watching me (us) as I (we) watch it, this despite already suspecting that when (I) you ‘encounter the gaze of the Other, you meet not a seeing eye but a blind one. The gaze is not clear or penetrating, not filled with knowledge or recognition; it is clouded over and turned back on itself, absorbed in its own enjoyment’ (p. 36). And here we have the bald truth of the (bio)massochist: he ‘wants himself to be a disparaged object; he cultivates the appearance of something that has been cast off and makes himself into a piece of trash’ (Soler and Holland, 2006, p. 76) for the Other, a failed subject, fat again, caught up in his own ‘stalled future’ (Bombak and Monaghan, 2017, p. 934), but also fattened with potential.

And trashed we are, as we get off on losing weight for an Other that doesn’t give a shit anyway, and then backtrack our own bodies when the (death) drive towards the ultimate slim satisfaction threatens to extinguish our desire. Perhaps this is why I (and you) have such a fascination with the image of the driven anorexic. Why some of us, with an almost religious zeal, spit vitriol against the (pro)anorexic community (Holland et al., 2018). ‘The abstinence and renunciation practised by anorexics disorient others, very much as the cloistered life of nuns does, by the quality of the impossible’ (di Meana, 1999, p. 122), although they ‘are dominated by the knowledge the Other has about them. They escape from total subjection by engaging in a mode of life which seems nonsensical and paradoxical. It is their way of calling a halt to the control others have always had over them’ (p. 128). In this way, anorexics are driven to consume nothing, specifically not giving ground to the grinding morality that this crazy world demands: the simultaneous slimness and hyper-consumption of the modern capitalist bulimic (Pirie, 2011; Vighi, 2016). Whatever the outcome, the anorexic subject’s future is not a stalled one.

But I cannot say the same thing about the biomassochist’s future. For us, ‘it’ is only a semblance; we remain totally subjected. Amidst the wreckage of the weight cycling subject, we recognise the desire that is both the ‘piece of trash’ fatty and the (temporarily) successful ‘slimmer’ but not the refusal of the anorexic, captured as she is by ‘this drive which bores a hole’ in her (di Meana, 1999, p. 52). The difference here is structural: Desire ‘helps us define this characteristic of drives: the drive becomes vital only when the organic senses become inoperative […] object a signifies the multiplicity of objects which could be substituted for it, whose common denominator is the real hole, the central place of loss between the subject and the Other’ (pp. 52–3). Thus, the biomassochist wants to perform for you to maintain his lack and desire. It is from this position that I can ask as a form of ending (Fig. 3).

Notes

If you have a spare hour or so, have a close read of Cooper and Fairburn’s (2003) attempt to ‘refine’ the unrefinable – in particular their recommendation to restore the concept of ‘nonpurging bulimia nervosa’ to the DSM.

References

Aphramor, L. (2005) Is a weight-centred health framework salutogenic? Some thoughts on unhinging certain dietary ideologies. Social Theory & Health 3(4): 315–40.

Arroyo, A., Segrin, C., and Andersen, K.K. (2017) Intergenerational transmission of disordered eating: Direct and indirect maternal communication among grandmothers, mothers, and daughters. Body Image 20: 107–15.

Bacon, L. and Aphramor, L. (2011) Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutrition Journal 10(9): 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-10-9.

Bombak, A.E. and Monaghan, L.F. (2017) Obesity, bodily change and health identities: a qualitative study of Canadian women. Sociology of Health & Illness 39(6): 923–940.

Cooper, Z. and Fairburn, C.G. (2003) Refining the definition of binge eating disorder and nonpurging bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders 34(S1): S89–S95.

Copjec, J. (1992) Read my Desire: Lacan Against the Historicists. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Dickson, A. (2011) The jouissance of the Lard (er): Gender, desire and anxiety in the weight-loss industry. Culture and Organization 17(4): 313–28.

Dickson, A. (2015a) Re: living the body mass index: How a Lacanian autoethnography can inform public health practice. Critical Public Health 25(4): 474–87.

Dickson, A. (2015b) Hysterical blokes and the other’s jouissance. Gender, Work & Organization 22(2): 139–47.

di Meana, G.R. (1999) Figures of Lightness: Anorexia, Bulimia and Psychoanalysis. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Feller, S., Müller, A., Mayr, A., Engeli, S., Hilbert, A., and de Zwaan, M. (2015) What distinguishes weight loss maintainers of the German Weight Control Registry from the general population? Obesity 23(5): 1112–18.

Foucault, M. (1986/2012) The Care of the Self. Volume 3 of The History of Sexuality. Translated by R. Hurley. New York: Vintage Books.

Freud. S. (1920/1955a) Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Standard Edition 18. London: Hogarth Press, pp. 7–64.

Gard, M. and Wright, J. (2005) The Obesity Epidemic: Science, Morality and Ideology. London and New York: Routledge.

Guthman, J. and DuPuis, M. (2006) Embodying neoliberalism: economy, culture, and the politics of fat. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 24(3): 427–48.

Heyes, C.J. (2006) Foucault goes to weight watchers. Hypatia 21(2): 126–49.

Holland, K., Dickson, A., and Dickson, A. (2018) ‘To the horror of experts’: reading beneath scholarship on pro-ana online communities. Critical Public Health 28(5): 522–33.

Kaufmann, J. (2005) Autotheory: An autoethnographic reading of Foucault. Qualitative Inquiry 11(4): 576–87.

Kristeva, J. (1982) Powers of Horror. Translated by L. Roudiez: Columbia University Press, New York.

Kristeva, J. (2004) Some observations on female sexuality. In: J.A. Winer, J.W. Anderson and C.C. Kieffer (eds) The Annual of Psychoanalysis: Psychoanalysis and Women. Vol. XXXII. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press, pp. 59–68.

Lacan, J. (1973/1998) The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XX: Encore, On Feminine Sexuality, The Limits of Love and Knowledge 1972–1973. Translated by B. Fink. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Lacan, J. (1986/1992) The Ethics of Psychoanalysis 1959–1960: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book VII, Edited by J.-A. Miller. Translated by D. Porter. New York: Norton.

Lacan, J. (2006) On Freud’s “Trieb” and the psychoanalyst’s desire. In: Écrits. Translated by B. Fink. New York: Norton, pp. 722–25.

Longhurst, R. (2012) Becoming smaller: Autobiographical spaces of weight loss. Antipode 44(3): 871–88.

McConnell, D. and Gillett, G. (2005) Lacan for the philosophical psychiatrist. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology 12(1): 63–75.

McGuire, M.T., Wing, R.R., and Hill, J.O. (1999) The prevalence of weight loss maintenance among American adults. International Journal of Obesity 23(12): 1314–19.

Nelson, M. (2015) The Argonauts. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press.

Pausé, C. (2017) Borderline: the ethics of fat stigma in public health. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 45(4): 510–17.

Pirie, I. (2011) The political economy of bulimia nervosa. New Political Economy 16(3): 323–46.

Rickard, G.K. (2009) The land of big queers: A fairy’s tale (To be read aloud then discarded just as quickly). Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society 14(1): 89–99.

Ruth, D., Wilson, S., Alakavuklar, O., and Dickson, A. (2018) Anxious academics: talking back to the audit culture through collegial, critical and creative autoethnography. Culture and Organization 24(2): 154–70.

Ruti, M. (2018) Penis Envy and Other Bad Feelings: The Emotional Costs of Everyday Life. New York: Columbia University Press.

Sayers, J.G. (2016) A report to an academy: On carnophallogocentrism, pigs and meat-writing. Organization 23(3): 370–86.

Soler, C. and Holland, J. (2006) What Lacan Said About Women: A Psychoanalytic Study. New York: Other Press.

Throsby, K. (2009) The war on obesity as a moral project: weight loss drugs, obesity surgery and negotiating failure. Science as Culture 18(2): 201–16.

Vighi, F. (2016) Capitalist bulimia: Lacan on Marx and crisis. Crisis and Critique 3(3): 415–32.

Vink, R.G., Roumans, N.J., Arkenbosch, L.A., Mariman, E.C., and van Baak, M.A. (2016) The effect of rate of weight loss on long-term weight regain in adults with overweight and obesity. Obesity 24(2): 321–27.

Warbrick, I., Dickson, A., Prince, R., and Heke, I. (2016) The biopolitics of Māori biomass: towards a new epistemology for Māori health in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Critical Public Health 26(4): 394–404.

Winship, G. and Knowles, J. (1996) The transgenerational impact of cultural trauma: Linking phenomena in treatment of third generation survivors of the Holocaust. British Journal of Psychotherapy 13(2): 259–66.

Žižek, S. (2002) For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor. London: Verso.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dickson, A. Biomassochism: Lacan and the ethics of weight cycling. Psychoanal Cult Soc 26, 364–377 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41282-021-00226-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41282-021-00226-4