Abstract

Governments in many European countries have been working towards integrating health and social care services to eliminate the fragmentation that leads to poor care coordination for patients. We conducted a systematic review to identify and synthesize knowledge about the integration of health and social care services in Europe. We identified 490 records, in 14 systematic reviews that reported on 1148 primary studies and assessed outcomes of integration of health care and social care. We categorized records according to three purposes: health outcomes, service quality and integration procedures outcomes. Health outcomes include improved clinical outcomes, enhanced quality of life, and positive effects on quality of care. Service quality improvements encompass better access to services, reduced waiting times, and increased patient satisfaction. Integration procedure outcomes involve cost reduction, enhanced collaboration, and improved staff perceptions; however, some findings rely on limited evidence. This umbrella review provides a quality-appraised overview of existing systematic reviews.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Key messages

-

Integration of social care and health systems appears to produce moderate improvement in social and health sectors and a wide range of improvements in health outcomes, service quality, and integration procedures outcomes.

-

Health and social care integration improves clinical outcomes and quality of care but faces limited, subjective evidence and financial challenges.

-

Integration is complex and costly, with potential long-term benefits but limited evidence of immediate cost savings and a focus on efficiency over patient outcomes.

Introduction

Critical demographic changes on the European continent [1] stimulated by scientific, technological, social, and economic advances have helped address many health problems. But they also present new challenges, including demand for more and increasingly complex health services as life expectancy increases, populations age, and prevalence of chronic diseases grows [2, 3].

Demographic changes over recent decades inspired countries adopt a goal: to integrate health and social care [4]. Doing so occupies a central place in the political discussion [5,6,7], as a key element in modernizing public policies [8].For the purpose of this review, we define integration as an approach to delivering health care that emphasizes coordination and collaboration among varied health professionals, services, and settings to provide comprehensive and seamless care [9, 10]. An integrated system ensures patients receive well-coordinated and continuous care to meet all their needs, with a focus on quality, improving outcomes, and optimizing use of resources. In a more holistic and patient-centric approach, services include medical, behavioral, and social services [11]. Understanding quality of care, and whether a new approach will improve it, depends on an inclusive measure of patient welfare, after taking into account the balance of expected gains and losses associated with all parts and the entire process of care [12]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), quality health services should be effective, providing evidence-based health care services to those who need them; safe, avoiding harm to people for whom the care is intended; people-centered: providing care that responds to individual preferences, needs and values. And, to achieve benefits of quality, the services must be timely and equitable, as well as integrated, and efficient [13].

Care of some patients is complex. No single professional can address all the needs, thus responsibility must be shared among patients and varied health and social care professionals who accompany them [6, 14, 15].

European country governments are developing policies to foster the integration of health and social care services [16,17,18]. These require new structures to enable sharing assessment and governance between different stakeholders, including healthcare providers, social care organizations, government bodies, and the public, to ensure a coordinated and efficient approach to service delivery [16,17,18,19,20]. Studies have shown resistance to health and social care integration in some countries due to complexities of implementation, resource allocation, and management of organizational changes in the system of care [16, 21, 22]. Some emphasize a need to develop new organizational models in health and social sectors to optimize resources and enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of healthcare and social care processes [9, 17, 20, 23,24,25].

Several countries, notably Denmark, England, Scotland, and Norway have initiated integration and studied changes intended to ‘humanize’ the care provided–as positive results of integration of [9, 26]. Several systematic literature reviews focus on integration of these systems worldwide [8, 16, 22, 27]. Given the diversity of stakeholders involved and the need for new ways of working, researchers characterize the management and learning involved as challenges. To date, the most successful examples of health and social care integration are small scale and highly localized.

Review question and objectives

The study aimed to synthesize the findings, quality and certainty of the evidence reported in systematic reviews on health and social care integration policies worldwide. It is an umbrella review, meaning a synthesis of existing systematic reviews, which allows findings of reviews relevant to a review question to be compared and contrasted [28].The research objectives included (1) identifying relevant systematic reviews [28]; and (2) assessing them to provide a comprehensive synthesis of evidence, including key elements or principles associated with better outcomes on models of social and healthcare integration [28]. The SPIDER model, a tool developed for qualitative research, consists of five domains of interest:

-

Sample (S): Countries with integration between healthcare and social care sectors

-

Phenomena of Interest (PI): Integration of health and social care

-

Design (D): All qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods reviews.

-

Evaluation (E): Not applied string due to the nature of the umbrella study

-

Research (R): Systematic reviews.

Understanding the impact of specific public health policy interventions will help to establish causality regarding the effects of welfare on population health and health inequalities. We conducted the review to document contextual information on the organization, implementation, and delivery of population-level public health interventions. This information can help to identify effective interventions for reducing health inequalities across and within European countries.

Data and methods

We developed a protocol following the JBI methodology for systematic reviews [29], and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2020 checklist [30, 31]. We conducted data selection and extraction process from April through July 2022. The umbrella review protocol has been registered on PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews—https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/), on 08 May 2022 on the (PROSPERO: CRD42022319432) [32]. The final version of the protocol was uploaded in Open Science Framework (OSF) and it is available in https://osf.io/nbqvc and https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022319432.

Search strategy

On 26 June 2022 we searched electronic bibliographic databases (PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Embase) using combinations of both natural language terms and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) connected with intervention as “integration”, “social care”, and “health” and terms of study-type-defining such as “systematic review” or “meta-analysis”. After selecting studies for inclusion, we also searched manually their reference lists for potentially relevant papers. We did not limit the search by dates. See the search strategy in Supplementary Material Table S1.

Study selection and eligibility criteria

Two researchers (RCM and CM) performed an initial screening of publications based on titles and abstracts. The same two independently evaluated full texts of studies that met the inclusion criteria. We included systematic reviews, with or without meta-analyses, that focused on integration of social and health care, with focus on patient-centered or service-centered outcomes. We looked for integration implemented in any health and social care setting, including primary, secondary, or community care. We included only reviews published in English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese languages. We excluded grey literature, letters to the editor, abstract or conference posters, and commentaries. We also excluded reviews that did not clearly report or provide sufficient information on the health or social care setting. The reviewers resolved most discrepancies through consensus. Where necessary, they consulted a third reviewer (GN). The screening process was blinded through the use of Covidence® software (https://www.covidence.org/) [33].

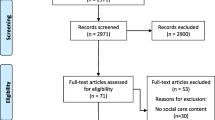

We identified 490 records, removed duplicates, screened 210 studies, and excluded 164 based on their titles and abstracts. We assessed forty-six full-text articles; 32 did not meet the eligibility criteria. We included the fourteen remaining articles in the analysis. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flowchart for the selection process and indicates reasons for exclusion. Due to heterogeneity of the reviews included it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis of quantitative findings, thus we present them in narrative format.

Data extraction and management

One reviewer read the full texts of each article that met the inclusion criteria and extracted data (RCM). To ensure accuracy, a different team member (CM) also checked the data extractions. The information included: author, year, country, study aim, databases searched, number of studies included, and main findings. In Supplementary Material Table S2, ‘main findings’ refers to the outcomes, results, or significant conclusions reported. These reflect key insights, observations, or conclusions about health and social care integration policies.

Assessment of methodological quality of included reviews

Two authors (RCM and CM) critically assessed the methodological quality of each systematic review using two tools: the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews tool (AMSTAR) and the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews 2 tool (AMSTAR-2) [34]. AMSTAR consists of 11 items; its designers intended it to be used for content validity [35]. The updated version, AMSTAR-2, consists of 16 items covering the entire process: topic selection, design, registration, data extraction, statistical analysis, and discussion of the systematic reviews [36]. The checklist allows ranking according to seven critical and nine non-critical areas. Based on the assessment provided by AMSTAR/AMSTAR-2, we classified the quality of each as “critically low”, “low”, “moderate”, and “high-quality”. Again we resolved disagreements through discussion with a third reviewer (GN) [36]. Of the two scales, AMSTAR-2 is more conservative, and results in very low rankings when some of the critical questions are omitted. This pertained to systematic reviews that did not provide meta-analysis.

Data synthesis and presentation

PRISMA guided our reporting [37]. We present the main results in tabular format with a narrative synthesis. We categorized results according to the three purposes: health outcomes, service quality, and integration procedures outcomes. Substantial heterogeneity among the primary studies in each systematic review, however, prevented pooling of intervention effects across reviews and meta-analyses. We present the synthetized findings according to three distinct phenomena of interest. That of health outcomes is of primary concern. Service quality emerged as a separate category because it encompasses elements that directly affect patient experiences with services and the effectiveness of health and social care delivery; but these are not related to the clinical and health status of the patient. To capture the organizational and structural aspects of integration, we grouped other findings together as integration procedure outcomes. We followed the methodology described by van Tulder et al. to evaluate the level of evidence used for synthetized findings [38].

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure is the extent to which integration of health systems is associated with quality of care, using a variety of metrics. We looked for indications of a change following integration that involved improvement of clinical outcomes, quality of life, or quality of care. We also considered avoidance of hospitalization and mortality indicators, and length of stay.

We evaluated three secondary outcomes: health, service, and economic. Health outcomes include clinical effectiveness such as mortality rates, adverse events, physical functioning, and patient-reported well-being. Service outcomes encompass utilization and accessibility of health services, hospital admissions, and length of patient stays. We examined the economic outcomes associated with health system integration, including cost savings, resource allocation, budget considerations, and performance measures. We included the barriers to effective integration and describe these in the results section.

Results

Summary and methodological quality assessment

The 14 studies reported on 1148 primary studies and review articles published between 2006 and 2021 (Supplementary Material Table S2). The number of articles covered by each review article ranged from 7 [39, 40] to 531 [41]. The majority of reviews included studies from multiple countries, although three reviews focused only on studies in the United Kingdom (UK). One review included only studies conducted in high-income countries.

The average AMSTAR score was 5.4 (range 3–10). This value indicates an average of five “yes” answers to all twelve items, thus, moderate overall quality. Low scores (poor quality) stem from items related to publication status as an inclusion criterion: listing of excluded studies, inclusion of study characteristics, and quality assessment. Most were qualitative reviews, thus there is no statistical analysis could. The AMSTAR-2 rating of overall confidence in the reviews was critically low in eight studies [8, 21, 22, 27, 39, 41,42,43], low in one [40], moderate in three [16, 44, 45] and high in two [46, 47]. The following domains of methodological quality are those to which all review authors adhered: (a) PICO components in the inclusion criteria and research questions; (b) establishing the methods prior to the conduct of the review; (c) using a comprehensive literature search strategy; (d) describing the included studies in adequate detail; (e) assessing the impact of risk of bias on the results of the meta-analysis; and (f) accounting for the risk of bias when discussing the results. We included only two meta-analyses in the study [46, 47] (see Supplementary Material Table S3 for the AMSTAR-2 assessment).

Below we present findings related to differing levels of evidence related to health outcomes, service quality, Integration procedures, barriers, and requirements for effective integrated health and social care (Table 1).

Health outcomes

Most reviews assessed the impact of integration on health outcomes, revealing consistent findings. We found integration yielded strong evidence of improvement in clinical outcomes [44] and moderate to strong positive impact on quality of life [16, 44,45,46], quality of care [16, 21, 27, 44, 46], and enhancement of self-management among older individuals with multiple chronic conditions [21, 42, 44,45,46]. Integration also showed promise in reducing hospitalization rates, with a moderate to strong effect [21, 40, 45, 46]. We found some inconsistent data, specifically regarding mortality rates [44], length of hospital stays [16, 27, 39, 44], unscheduled admissions [16, 27, 40, 47], and readmissions [16, 21, 27, 40, 44, 47]. Thus, the impact of integration on these dimensions remained inconclusive, highlighting need for additional investigation to establish a clearer understanding of the impact of integrated care on them.

Service quality

Strong and consistent evidence across studies indicates significant improvements in access and availability of services [16, 27, 39, 46]. A moderate to strong level of evidence supports the finding that integration produced overall positive effects on patient satisfaction [16, 44]. A moderate level of evidence supports favorable effects on reducing waiting times for hospital admission and medical appointments [21, 27]. And a moderate level of evidence supports a positive association of integration with health equity outcomes [21, 43, 45]. Only limited evidence supports a finding of favorable impact of integration on certain aspects of service quality, such as improvements in prescribing rates [16], and on reduced time spent in specific hospital departments as emergencies [16, 27, 40, 42]. Data related to the number of clinician contacts and adherence to quality of care standards presented inconsistencies [16], emphasizing the need for further research to clarify these dimensions and strengthen the evidence base.

Integration procedures

The impact of integration extends to integration procedure outcomes. Multiple studies found that Integration demonstrated a moderate to strong positive effect on staff perceptions [16, 27, 40, 45, 46], an important influence on how staff perceive and engage with integrated care initiatives. Integration also demonstrated:

-

a moderate positive impact on collaboration between social care staff and healthcare professionals, promoting better cooperation and coordination [40].

-

a moderate effect in improving capacity for ongoing support and training for care home staff, emphasizing the importance of integrated approaches in enhancing staff capabilities[40].

Evidence of positive impact is limited in other areas, or inconsistent:

-

on availability of resources and the impact of integration on access to different resources [16]

-

on beneficial effects on some clinical care settings [16, 27, 39, 40, 42].

-

on cost reduction [16, 22, 27, 39, 41, 43,44,45] and staff working experiences [8, 16, 21, 27, 40, 47] some studies pointed to positive, neutral, or negative impact.

Studies on the cost of integration found difficulties in implementation of financial integration, and budget holders’ control over access to services remained limited [16]. Many partnerships proved to be costly, hard to manage, and rife with struggle over cultural, organizational, and accountability issues [46]. Integrated care showed significant results in reducing of mean treatment costs [47], but studies often concluded too soon for these benefits to be realized [39]. Although some evidence indicates that co-financing the health and social sectors can lead to improved outcomes [24], other studies suggested inconsistencies about cost savings from avoided hospitalizations [37] and lack of clarity about reduction in service costs [27]. Integration failed to demonstrate strong evidence in cost reduction in some studies [16, 27]; others suggested that costs could actually increase [16]. A recent meta-analysis of economic evidence on integrated care across different clinical and care areas, and types of integration, found an association between integrated care and lower costs compared to usual care [43]. Most systematic reviews of delivery arrangements lack economic evaluations, thus the value of many of these models is unknown [44, 45].

Barriers

Integration may be hard to measure and overestimated by policymakers [46]. Barriers to successful operation of integration include time consumption for the services and health and social care professionals, failure to acknowledge the expertise of home care staff and high turnover of care home staff, and limited availability of training for professionals in both sectors [40] Health equity is generally not included in the integration setting and limited evidence suggests lack of access to health care services by some populations, particularly those from marginalized communities, lower socio-economic backgrounds, or rural areas, highlighting a critical need for more inclusive health policies and practices [43, 45, 48]. Other studies report poor service coordination due to the number of professionals involved in caring, or to involvement of multiple jurisdictions and budgets for health and social care [41]. Uptake and use of technology are also major barriers, including financial investment in equipment (to set up and to continue use), licensing, and software required [45]. Despite these barriers, many integration schemes including those that failed to improve health or reduce costs have reported improvements in access to care [27].

Requirements for effective integrated health and social care

A challenge for health care systems is determining how to deliver high-value and effective care while trying to reduce the rate of increase in costs [41]. Optimal resource allocation is fundamental to success for integrated health and social care programs that depend on adequate funding, staffing, and infrastructure. Moreover, to ensure these resources are used effectively, robust economic evaluations of alternative care delivery models are essential. These evaluations inform decisions about funding allocation by comparing the relative value of different models in terms of their effectiveness and efficiency [41]. Effective integrated care requires interprofessional collaboration between health and social care professionals [16], with effective communication and shared decision-making as key elements. Definition of clear roles and responsibilities avoid duplication of efforts and allocation of resources and time ensure effective care [22].

One study identified the length of time it took for teams to become fully operational during the integration and noted that assuring long-term commitment of the organizations is also important [47]. Another study identified need for effective communication between professional groups within teams; for role awareness and for education about working in partnership, along with professional and personal development of staff [39]. The same study identified a need to reinforce partnerships between higher education institutions and health and social care organizations [39].

Integrated care should address the unique needs and preferences of patients, ‘patient centered care’. Patients and their families should participate actively in decision-making, addressing social determinants of health, such as housing, employment, and access to social services, as well as medical concerns [16]. Integrated care programs require robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to assess effectiveness continually, with defined metrics to measure outcomes, including clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, cost savings, and reductions in health disparities [22]. Intersectoral initiatives need to include a comprehensive equity analysis to identify which populations are positively or negatively affected and the conditions under which such effects occur [43].

Discussion

This study aims to enhance the evidence base for policymakers and inform future interventions by synthesizing and assessing evidence from systematic reviews about health and social care integration policies on a global scale. It identifies relevant systematic reviews and the evidence of outcomes within the integration of health and social care. We categorized evidence by health outcomes, service quality and integration procedure outcomes, and different levels of evidence. Evidence of effectiveness is limited and often subjective. Integration of social and health sectors can lead to greater effectiveness by boosting both sectors, but reduced budgets may lead organizations and professionals to withdraw from integration to protect their own funding [49]

The integration of health and social sectors aims to enhance overall care efficacy, yet financial constraints and reduced budgets could hinder these efforts. Key areas requiring further research include the impact on mortality rates, hospital stays, and patient readmission, as well as the financial implications of integration, especially in systems combining health and social care. There's a need for improved understanding of integration's effects on service quality, such as patient and professional satisfaction, and waiting times. While promising in improving clinical outcomes and quality of life, integration in health and social care necessitates further investigation to address uncertainties and adapt effectively to diverse healthcare contexts.

Integration is a complex process requiring high initial investment in time and resources for preparation and planning. Thus, countries sometimes reduced investment in other sectors to ensure sustainability of the integration. Studies have produced inconclusive results on the total cost reduction [27]. Integration may produce new services; these may require time to become stable, and cost savings may become visible only in the long term. Scant evidence supports this claim [50].

Some authors argue that the integration can be driven by the need for cost efficiency, rather than focusing on improving patient outcomes [51]. This review points to more evidence about improvements on health outcomes and service quality than for cost saving through the process. Thus, overall, the evidence supports integration of these two sectors primarily to improve patient outcomes, not to contain costs. Thus, countries considering integration due to budgetary constraints should reconsider this as a way of dealing with this scarcity of resources. Improvements in patient care may be a beneficial consequence rather than the main motivation [27, 50, 51].

Comparison between countries is difficult due to the great diversity of integration models and national policies, and to the large number of outcomes that can be measured [8]. The literature categorizes the impact of integration in health care into three main areas: health outcomes, service quality, and service efficiency, which includes considerations of costs and the perspectives of healthcare professionals. In terms of health outcomes and service quality, there is clear evidence of improvement following integration, although there are still several aspects that remain unexplained or where the data are either inconsistent or too limited to draw strong conclusions. This grouping helps in systematically assessing the multifaceted effects of integration on healthcare systems. On the first two, evidence from improvement is clear, despite of several outcomes that remain unexplained, or inconsistent, or where data are too scant to support strong conclusions.

Essential to success are cooperation between entities in health and social settings to provide citizens with effective health and social care, and promoting communication between health and social services to identify if care is not being provided. So too is strengthening cooperation between the policymakers, social and health institutions.

Study limitations

One limitation of the umbrella review approach is its inclusion of only articles in systematic reviews. This may exclude the most recent information. Strict criteria for defining a systematic review and inclusion may further reduce study results that may be pertinent to the topic. By limiting our review to the authors' proficiency languages could also have excluded relevant studies published in other languages. We suspect this limitation has a negligible impact on the effect estimates and conclusions.

The diverse models and approaches adopted by different countries and regions [16, 22, 41, 44] may encompass both vertical integration (of different levels of care, services, or functions, with the coordination of primary, secondary and tertiary health care services in a tiered service delivery system), and horizontal integration, (with other organizations that provide the same or similar services) [10, 52, 53]. Although our review encompassed various models, the vertical integration model tends to be more prevalent. This emphasis reflects the nature of the integrated care where coordination and collaboration across levels of health care play important roles in achieving comprehensive and patient-centered care.

Conclusions

This umbrella review provides a quality-appraised overview of existing systematic reviews and allows for a comprehensive review of a vast topic by summarizing the evidence from multiple research syntheses into one systematic review of reviews. We found that the scientific literature on the integration of social and health care in Europe is relatively limited, with most examples being highly localized and evidence still limited, inconsistent, or unexplored. Overall, integration of social care and health systems appears to produce moderate improvement in social and health sectors and a wide range of improvements in health outcomes, service quality, and integration procedures outcomes. Due to the limited amount of evidence available in most reviews, the current umbrella review's conclusions are weak though instructive if used with caution.

References

Eurostat. Demographic change in Europe - country factsheets. Luxembourg: Eurostat; 2020.

Cortes M. Breve olhar sobre o estado da saúde em Portugal. Sociol Probl e práticas. 2016;80:117–43.

Sousa P. O sistema de saúde em Portugal: realizações e desafios. In: Acta Paulista de Enfermagem. 2009. p. 884–894.

Anderson GF, Hussey PS. Population aging: a comparison among industrialized countries: populations around the world are growing older, but the trends are not cause for despair. Health Aff. 2000;19(3):191–203.

Hills M, Mullett J, Carroll S. Community-based participatory action research: transforming multidisciplinary practice in primary health care. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2007;21:125–35.

Nies H. Managing effective partnerships in older people’s services. Heal Soc Care Commun. 2006;14(5):391–9.

Plochg T, Klazinga NS. Community-based integrated care: myth or must? Int J Qual Heal Care. 2002;14(2):91–101.

Kelly L, Harlock J, Peters M, Fitzpatrick R, Crocker H. Measures for the integration of health and social care services for long-term health conditions: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Robertson H. Integration of health and social care. A review of literature and models. Implications for Scotland. R Coll Nurs Scotl. 2011;1–42.

Valentijn PP, Schepman SM, Opheij W, Bruijnzeels MA. Understanding integrated care: a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int J Integr Care. 2013;13.

Clough GP. Does the integration of healthcare and social care help improve the health of senior citizens in the UK? The University of Manchester (United Kingdom); 2021.

Donabedian A. Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring. Defin Qual Approach Assess. 1983;1.

Organization WH, others. Handbook for national quality policy and strategy: a practical approach for developing policy and strategy to improve quality of care. Geneva: WHO; 2018.

Hultberg E-L, Glendinning C, Allebeck P, Lönnroth K. Using pooled budgets to integrate health and welfare services: a comparison of experiments in England and Sweden. Heal Soc Care Commun. 2005;13(6):531–41.

World Health Organization. The world health report 2006: working together for health. World Health Organization; 2006.

Baxter S, Johnson M, Chambers D, Sutton A, Goyder E, Booth A. The effects of integrated care: a systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–13.

Heenan D, Birrell D. The integration of health and social care in the UK: Policy and practice. Macmillan International Higher Education; 2017.

Taylor A. New act, new opportunity for integration in Scotland. J Integr Care. 2015.

Nummela O, Juujärvi S, Sinervo T. Competence needs of integrated care in the transition of health care and social services in Finland. Int J Care Coord. 2019;22(1):36–45.

Heenan D, Birrell D. The integration of health and social care: the lessons from Northern Ireland. Soc Policy Adm. 2006;40(1):47–66.

Ndumbe-Eyoh S, Moffatt H. Intersectoral action for health equity: a rapid systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–13.

McGuire F, Vijayasingham L, Vassall A, Small R, Webb D, Guthrie T, et al. Financing intersectoral action for health: a systematic review of co-financing models. Globalization and Health; 2019. p. 1–18.

Kaehne A, Birrell D, Miller R, Petch A. Bringing integration home: Policy on health and social care integration in the four nations of the UK. J Integr Care. 2017.

Pike B, Mongan D. The integration of health and social care services. 2014.

Correia T. New Public Management in the Portuguese health sector: a comprehensive reading. Sociol line. 2011;2:573–98.

Audit Scotland. Health and social care integration: update on progress. 2018. 2018.

Mason A, Goddard M, Wearherly H, Chalkley M. Integrating funds for health and social care: an evidence review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;20:177–88.

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evid Implement. 2015;13(3):132–40.

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Chapter 10: umbrella reviews. JBI Man Evid Synth JBI. 2020.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1–9.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;2015:349.

Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, Ghersi D, Moher D, Petticrew M, et al. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2012;1(1):1–9.

Babineau J. Product review: Covidence (systematic review software). J Can Heal Libr Assoc l’Association des bibliothèques la santé du Canada. 2014;35(2):68–71.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):1–7.

Chmielowska M, Zisman-Ilani Y, Saunders R, Pilling S. Social network interventions in mental healthcare: a protocol for an umbrella review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e052831.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906.

Van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L, of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group EB, others. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(12):1290–9.

Mackie S, Darvill A. Factors enabling implementation of integrated health and social care: a systematic review. Br J Commun Nurs. 2016;21(2):82–7.

McGregor J, Mercer SW, Harris FM. Health benefits of primary care social work for adults with complex health and social needs: a systematic review. Heal Soc Care Commun. 2018;26(1):1–13.

Jessup R, Putrik P, Buchbinder R, Nezon J, Rischin K, Cyril S, et al. Identifying alternative models of healthcare service delivery to inform health system improvement: scoping review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e036112.

Genet N, Boerma WGW, Kringos DS, Bouman A, Francke AL, Fagerström C, et al. Home care in Europe: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):1–14.

Howarth M, Holland K, Grant MJ. Education needs for integrated care: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(2):144–56.

Liljas AEM, Brattström F, Burström B, Schön P, Agerholm J. Impact of integrated care on patient-related outcomes among older people--a systematic review. Int J Integr Care. 2019;19(3).

Rocks S, Berntson D, Gil-Salmerón A, Kadu M, Ehrenberg N, Stein V, et al. Cost and effects of integrated care: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Eur J Heal Econ. 2020;21(8):1211–21.

Alderwick H, Hutchings A, Briggs A, Mays N. The impacts of collaboration between local health care and non-health care organizations and factors shaping how they work: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–16.

Davies SL, Goodman C, Bunn F, Victor C, Dickinson A, Iliffe S, et al. A systematic review of integrated working between care homes and health care services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):1–21.

Of Sciences Engineering, Medicine, others. Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: Moving upstream to improve the nation’s health. 2019.

Glasby J. Integrated care in a cold climate. Int J Integr Care. 2010;10.

Weatherly H, Mason A, Goddard M, Wright K. Financial integration across health and social care: evidence review. Scottish Gov Soc Res. 2010.

Cook A, Petch A, Glendinning C, Glasby J. Building capacity in health and social care partnerships: key messages from a multi-stakeholder network. J Integr Care. 2007.

Thomas P, Meads G, Moustafa A, Nazareth I, Stange KC, Donnelly HG. Combined horizontal and vertical integration of care: a goal of practice-based commissioning. Qual Prim Care. 2008;16(6):425–32.

Rumbold B, Shaw S. Horizontal and vertical integration in the UK: lessons from history. J Integr Care. 2010;18(6):45–52.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

No approval or consent was needed for this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

41271_2023_465_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary file1 (PDF 208 KB) Supplementary Material: The Supplementary Material includes Table S1: Search strategies; Table S2: Studies included in the umbrella review; Table S3: Critical appraisal of the included systematic reviews.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

de Matos, R.C., do Nascimento, G., Fernandes, A.C. et al. Implementation and impact of integrated health and social care services: an umbrella review. J Public Health Pol 45, 14–29 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-023-00465-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-023-00465-y