Abstract

This study examines how immigration policy impacts citizens’ trust in politicians and political institutions. The article argues that immigration policy affects political trust through policy congruence. More specifically, it claims that the level of restrictiveness of immigration policy impacts political trust heterogeneously, conditional on whether citizens are anti- or pro-immigration and additionally on how strongly citizens are seeking information about political issues, the latter making it potentially easier for them to identify policy (in-)congruencies. Combining country-level data on immigration policy outputs in European countries with individual-level data to complex multilevel models, the findings reveal that the level of congruence of immigration policy to citizens’ immigration preferences alone does not impact political trust. But they show that immigration policy impacts the political trust of citizens who are highly anti-immigration and at the same time very strongly seeking political information. Overall, however, the article concludes that the impact of immigration policy congruence on political trust is moderate at best.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Citizens’ trust in political institutions and authorities is essential for the stability and viability of representative democracies (van der Meer and Zmerli 2017, p. 1). A lack of political trust reduces citizens’ degree of compliance with law (Marien and Hooghe 2011), the capacity of political leaders to effectively govern and adopt redistributive policy (Hetherington 2004), and it can increase political cynicism (van der Meer 2017b). Variations in citizens’ political trust result to a considerable extent from the degree to which citizens feel substantively represented by government policies (e.g., Citrin et al. 2014; McLaren 2016).

Among the most salient and polarizing policy issues in European countries in recent decades is immigration policy (Givens and Luedtke 2005; Lahav 1997), which is part of the new integration–demarcation cleavage (e.g., Grande and Kriesi 2012). European citizens’ views diverge strongly on how strictly immigration to their country should be regulated (e.g., Heath and Richards 2019; McLaren 2015, chap. 3). Moreover, public debates over immigration policy are heated and polarized. However, we do not yet know whether the extent to which immigration policy substantively represents citizens’ immigration preferences matters for political trust.

Addressing this issue is of great importance from both a practical and scholarly perspective. The so-called ‘liberal paradox’, which assumes that liberal democracies must balance competing demands arising from representation, constitutionalism, and capitalism (Hampshire 2013), limits the ability of liberal democratic governments to enact restrictive immigration policies even though the median voter calls for tightening immigration (Ford et al. 2015; Morales et al. 2015). In other words, the fact that in the design of immigration policy, liberal democratic governments must reconcile ‘representation’ with ‘responsibility’ (e.g., Armingeon and Lutz 2019) provides particularly great potential for reduced political trust among the anti-immigration public.

To study effects on political trust, studies have so far focused on policy effects of integration and multiculturalism policies (Citrin et al. 2014; Hooghe and de Vroome 2015; McLaren 2016). These policies are directed at the obligations and rights concerning the participation of immigrants (Helbling et al. 2020, p. 2604). There are indications that integration policy is in line with public preferences, whereas immigration policy is not (Lutz 2021). This could imply that the effects of immigration policy on political trust are more negative than those of integration policy, making the former the more relevant case to study.

There is, however, no study that has examined the impact of immigration policies on political trust. Immigration policies regulate who can be admitted and permitted to stay (Helbling et al. 2020, p. 2604), and they are referred to here as ‘policy outputs’, that is concrete laws, regulations, and decisions (Knill and Tosun 2011, pp. 496–497). Instead, existing studies have looked at effects of immigration ‘policy outcomes’ on political trust, thus focusing on the consequences resulting from the outputs (Easton 1965, p. 351). These refer to effects of immigration rates (Jeannet 2019; Rocha et al. 2015), asylum applications (Harteveld et al. 2018), or perceived government performance (McLaren 2011). But to make claims about the consequences of public representation of citizen preferences by immigration policies for political trust, the impact of concrete immigration policy outputs must be investigated. I refer to this effect on political trust as an effect of policy congruence, namely, the extent to which policy content and citizen preferences and interests match (Golder and Ferland 2017, p. 229).

What is more, it has been pointed out that there are strong differences among citizens in how much they know about their country’s public policies (e.g., Achen and Bartels 2016). In that regard, studies have suggested that effects of ideological congruence on citizens’ support of the political system are conditional on how strongly citizens are seeking information about political issues (e.g., Stecker and Tausendpfund 2016), making it easier for them to identify policy (in-)congruencies (Campbell 2012). To make convincing claims about the effects of immigration policy on political trust, it is therefore imperative to take into account heterogeneity in the extent to which citizens are seeking political information.

Against the background of the limitations of existing studies, I attempt for the first time to test in a systematic way the consequences of the degree of government immigration policy congruence for peoples’ trust in national political institutions in European countries. I argue that if the immigration policy output of a country is congruent or incongruent to citizens’ ideological preferences, citizens’ levels of political trust increase or decrease, respectively. I also argue that policy effects are greater for citizens with a higher compared to lower level of seeking political information.

I test my arguments with complex multilevel models by combining country-level data from the Immigration Policy in Comparison index (Helbling et al. 2017) for 23 European countries for the period 2002–2010 with corresponding individual-level data from the European Social Survey. The policy index measures the restrictiveness of concrete immigration laws, and it combines many specific regulations regarding immigration conditions, eligibility criteria, security of status and rights. First, the empirical results demonstrate that the impact of immigration policy congruence on political trust is substantively negligible. Second, however, the results show that immigration policy congruence affects the political trust of people who very strongly oppose immigration, once very high levels of political information seeking are accounted for.

Theoretical framework

The concept of political trust

Political trust can be defined as “citizens’ support for political institutions […] in the face of uncertainty about or vulnerability to the actions of these institutions” (van der Meer 2017b, p. 1). Objects of support for the political system span from more specific to more abstract (Norris 1999, 2017). Trust in institutions such as parliament, political parties, the legal system, and political authorities represent a “middle-range object of support” (van der Meer and Zmerli 2017, p. 4). It correlates with trust in individual politicians and with support of the regime principles, but is different from them (Marien 2011, 2017; van der Meer 2017b, pp. 5–6). As it is considered central yardstick for whether a democracy is in good condition (Hakhverdian and Mayne 2012, p. 740), I concentrate on political trust in institutions.

Drawing from theories and existing empirical research, I view political trust in a rationalist manner as an ‘evaluative orientation’ (Hakhverdian and Mayne 2012, p. 740; Hetherington 1998; Mishler and Rose 2001). In that perspective, citizens evaluate political institutions in a given political domain as to whether they act in their interest (Mishler and Rose 2001, p. 32), and trust is thus relational and situational (Hardin 1999; Levi and Stoker 2000, p. 476), and rather volatile (van der Meer and Zmerli 2017, p. 4). To the contrary, ‘cultural theories’ (e.g., Mishler and Rose 2001; Norris 2011) stress the empirical relevance of interpersonal trust (e.g., Liu and Stolle 2017), and long-lasting cultural changes such as increases in educational levels and postmaterialist values (Inglehart 1999; Norris 2011, p. 7) for political trust.

Drawing from the evaluative perspective, I argue that political trust results from citizens’ evaluations of the extent of ‘substantive representation’ (Noordzij et al. 2021). Substantive representation is given when the actions of representatives resemble the substantive or ideological preferences of citizens (Golder and Ferland 2017). As a static type of substantive representation, ‘ideological congruence’ demands that “the actions of the representative are in line with the interests of the represented at a fixed point in time” (Golder and Ferland 2017, p. 216).Footnote 1 An essential condition for ideological congruence is policy congruence, namely, the resemblance of policy content with citizen preferences (Golder and Ferland 2017, p. 229). Studies show that political trust is greater when government policies are in line with citizens' preferences, as citizens feel more strongly that institutions are acting in their interests. For instance, using objective policy measures, studies find that political trust is greater when integration and multiculturalism policies are more in line with citizens’ ideological preferences related to migration (Citrin et al. 2014; Hooghe and de Vroome 2015; McLaren 2016). Other studies find that ideological congruence and how it affects support of the political system also depends on its institutional characteristics (Golder and Stramski 2010; Reher 2015).

Another strand of studies linked to the evaluative perspective argues that political trust results from citizens’ evaluations of the ‘quality of representation’ (Noordzij et al. 2021). In that perspective, political trust is explained by evaluations of ‘institutional process’ (e.g., Hakhverdian and Mayne 2012) and ‘institutional performance’. Studies focusing on institutional performance effects traditionally investigate the role of (evaluations of) macro-economic performance (e.g., van der Meer 2017b) and the welfare state (e.g., Kumlin 2014) on political trust, and more recently immigration. Arguing that anti-immigration citizens associate (a growth in) the presence of migrants with bad institutional performance, they find that for this group a rise in migrant stock (Jeannet 2019, p. 5) and asylum applications (Harteveld et al. 2018) decrease political trust while higher deportation rates increase it (Rocha et al. 2015).

Yet, this latter approach does not speak to how policies as policy outputs or legal regulations (Knill and Tosun 2011) impact political trust, as it focuses on policy outcomes instead. Therefore, I concentrate instead on policy congruence, as it enables conceptualizing the effects of citizens’ substantive representation by concrete immigration policy outputs on political trust. In that line, political trust increases (decreases) when immigration policy is in line (not in line) with citizens’ preferences.

Immigration policy congruence and political trust

In terms of underpinning mechanisms, I conceptualize the effect of immigration policy congruence on political trust as an ‘interpretive effect’ (Pierson 1993, p. 611; see also Ziller and Helbling 2017, p. 4). The concept is part of policy feedback theory, which asserts that the content of public policy influences mass public opinion and behavior (Campbell 2012; Mettler and Soss 2014). The interpretive effects perspective assumes that policies influence public opinion by providing information and meaning regarding the policies (Pierson 1993). Policies feature as interpretive signals, which influence the public’s “perceptions about what their own interests are and whether their representatives are protecting those” (Pierson 1993, p. 621).

Building from the above, I argue that immigration policies impact political trust heterogeneously conditional on whether the contents are (in-)congruent with the anti- or pro-immigration preferences of citizens. During the period of this study, the first decade of the 2000s, European countries hosted and received significant numbers of workers, asylum seekers, and family members (McLaren 2015, chap. 3; Messina 2007, pp. 3–4; van Mol and de Valk 2016). Immigration issues were salient politically (Givens and Luedtke 2005; Kriesi 2012; Lahav 1997; Messina 2007, pp. 5–6; 9) and publicly (Dennison 2020, p. 416; Paul and Fitzgerald 2021, p. 383), thus being of significance for the formation of citizens’ political attitudes.Footnote 2

European citizens also strongly varied in their opinion of whether they were in favor or against more immigration (McLaren 2015, chap. 3). But given that immigration policy across European countries has systematically become more liberal in past decades (Helbling and Kalkum 2017) despite public demands for restrictions, there is most potential for decreased political trust among the opponents of immigration. A central reason for the liberalization trend is that, as presumed by the ‘liberal paradox,’ liberal democracies must reconcile demands of the public for restrictions with external demands for liberalizations resulting from well-organized capitalist interests and constitutionalism when designing immigration policy (Hampshire 2013, chap. 3). It ties in with the idea that democratic governments must balance ‘representation’ and ‘responsibility’ in order to govern legitimately (Mair 2009, pp. 10–12). From this follows that whereas responsible (i.e., more liberal) immigration policy is likely to be evaluated by anti-immigration citizens as unrepresentative of their interests and preferences, it is likely to be evaluated by pro-immigration citizens as representative, thereby impacting the political trust of these groups heterogeneously.

Citizens who are anti-immigration view national membership to be based on shared ethnicity and culture (Citrin et al. 2014; Heath and Tilley 2005, p. 128). Therefore, anti-immigration citizens view immigration as a threat to the cultural identity of their country (Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015) and their own exclusive status in its political community (McLaren 2011). Thus, they will interpret liberal and thus ‘responsible’ immigration policies as ‘unrepresentative’ of their immigration policy preferences. Their political trust is expected to decrease if they feel that the immigration policy adopted by politicians and institutions mismatches their interest in the preservation of the country’s cultural identity (cf., McLaren 2015, chap. 4). To the contrary, restrictive policies that are viewed to alleviate the perceived threat from immigration signal to anti-immigration citizens that institutions and politicians are acting on their behalf. Thus, immigration policy interpreted as restrictive and therefore less ‘responsible’ is expected to increase political trust. Consequently, I propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1a

Restrictive immigration policies will increase the political trust of people who oppose immigration, while liberal immigration policies will decrease it.

In contrast, people who are pro-immigration define national membership as based on shared political principles rather than shared ethnicity or culture (Citrin et al. 2014, p. 5; Wright 2011, p. 838). Membership in the national community is thus viewed to be achieved by attaining citizenship, learning the country’s language, and respecting the law (Heath and Tilley 2005, p. 122). People supporting immigration therefore likely interpret a liberal or ‘responsible’ immigration policy to be in line with their ideological profile, and to thus be ‘representative’ of their views. These policies may include, for instance, measures to facilitate admission of unskilled labor migrants and to grant asylum seekers the right to work. In contrast, restrictive immigration policies may be rejected as making it too difficult for foreigners to achieve membership. Thus, citizens who support immigration may interpret from liberal immigration policies that political authorities and institutions are substantively representing their ideological preferences, and from the enactment of restrictive policies that they are not, thus increasing and decreasing their political trust, respectively. I therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1b

Restrictive immigration policies will decrease the political trust of people who support immigration, while liberal immigration policies will increase it.

Political information seeking

Empirical studies investigating policy effects on citizens’ attitudes presume that people have some knowledge about the policies (Ziller and Helbling 2017, p. 5). This assumption is questionable because knowledge of which policies have been passed or amended in the country varies strongly across citizens (e.g., Achen and Bartels 2016). A condition for immigration policy effects to occur on political trust is therefore that people have some information about them (see Campbell 2012; Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996, p. 176).

Studies suggest that active seeking of political information is associated with knowledge of public policy (e.g., Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996, p. 176). In this vein, self-exposure to political information via the media has been identified to trigger knowledge about policies (e.g., Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996; Vettehen et al. 2004). News media such as newspapers, radio, and television do so by informing about public policies and by making them more intelligible (Campbell 2012, pp. 345–346). Besides news exposure, political interest is associated with seeking of political information (e.g., Fraile and Iyengar 2014, p. 281; Luskin 1990). It motivates people to learn about a wide range of political issues (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996, p. 175; Galston 2001, p. 222), and it makes them more attentive to the policy positions of political authorities (Otjes 2018, p. 648; De Vries and Giger 2014).

In this vein, I assume that seeking of political information conditions the immigration policy feedback process on political trust, as it should make the contents of the policies more visible to the public and more traceable to the actions of politicians and institutions (see Ziller and Helbling 2017, p. 5). It allows people to better compare their own policy positions to those of authorities, to identify (in-)congruencies and to reward or punish them accordingly (see Pierson 1993, p. 622). In support of these arguments, a study finds that a more visible welfare state enables voters to better compare their own positions with those of political parties (Gingrich 2014, p. 566). Other studies show that political interest moderates the effect of policy distance on democratic satisfaction (Stecker and Tausendpfund 2016), and that knowledge about antidiscrimination policy (Ziller and Helbling 2017) and institutional performance (Cook et al. 2010) affects political trust. Based on these considerations, I expect the following:

Hypothesis 2

The moderation effect of immigration attitudes on the association between immigration policy and political trust is stronger the higher the degree of political information seeking.

Data, measures, and method

Measure of immigration policy

To cover national and over-time variation in immigration policy, I use data from the Immigration policy in Comparison dataset (IMPIC; Helbling et al. 2017). The IMPIC measures policy outputs (i.e., the concrete laws and legal regulations instead of their implementation or resulting outcomes) for the years 1980 to 2010 for 33 countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). It captures regulations pertaining to the policy areas of labor migration, refugee and asylum policy, family reunification, and co-ethnics (Helbling et al. 2020, pp. 2607–2608).

For each policy area, the index measures the restrictiveness of eligibility criteria and entry conditions, which determine how hard it is for an immigrant to become a legal resident in a country. Furthermore, the index captures the security of status and the rights that come with a specific entry permit, determining for instance length of stay and employment access. The index also captures the extent of enforcement of these regulations through the control of irregular immigration (Helbling et al. 2020, pp. 2607–2608).

To create the IMPIC dataset, legal experts provided information on concrete legal regulations by answering a questionnaire. On that basis, the IMPIC team coded the restrictiveness of these regulations. All resulting items on regulations map the level of restrictiveness of concrete legal regulations (Helbling et al. 2017, pp. 86–90). They can vary between 0 (liberal) and 1 (restrictive). The fact that the index measures restrictiveness as opposed to policy changes guarantees comparability over time and between countries (Helbling et al. 2017, p. 88).

All these individual items were aggregated to retrieve comprehensive measures for the restrictiveness of the different policy areas (Helbling et al. 2017, pp. 90–92). To ensure the comparability between the different policy areas, the mere existence of a specific law is fixed at the value of 0.5 (Helbling et al. 2017, p. 89). Schmid and Helbling (2016) find that the policy areas of labor migration, family reunification, and refugees and asylum form a unique and coherent dimension, while the policy areas co-ethnicity and control of irregular immigration constitute a separate dimension each (Helbling et al. 2020, p. 2608).

Based on these findings, I use a single comprehensive indicator that is the mean score of the above-described restrictiveness measures for the three policy areas of labor migration, family reunification, and asylum and refugees. These areas are the main legal channels of immigration (e.g., Messina 2007). Regulations targeting co-ethnic migrants are excluded because it concerns a special category of immigrants existing in only few countries (for a similar approach see Helbling et al. 2020, p. 2608). Moreover, because immigration control does not concern immigration regulations but their enforcement, it is not relevant for testing my argument. In Table A1 in the Online Appendix, I list all regulations that constitute the comprehensive index that I use.

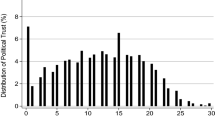

The index ranges from 0.19 to 0.80, with a mean value of 0.33, indicating that immigration policy among the country sample and the selected time period (i.e., 23 countries, period 2002–2010) is liberal on average (see Table 1 for an overview of the variable). Because the index is skewed (see Figure A1 in the Online Appendix), I divided the variable into quartiles to better capture the relevant information towards the lower end of the scale (the 1st quartile being the quartile with the most liberal immigration policy values, and the 4th quartile being the quartile with the most restrictive immigration policy values).

Illustration of the conditional effect of immigration attitudes on political trust (2-way interaction). Note Shows the predicted effect of immigration policy on political trust at pro-immigration attitudes (= black line) and anti-immigration attitudes (= gray line), with 95% confidence intervals. Predictions are based on Model 2 in Table A8 in Online Appendix. Immigration policy restrictiveness on x-axis divided into four quartiles, with quartile 1 representing the most liberal immigration policy values and quartile 4 the most restrictive immigration policy values. Pro- and anti-immigration attitudes fixed at 2SDs below and above the mean, respectively

Individual-level data

Individual-level data are retrieved from waves 1–5 (2002–2010) of the European Social Survey (ESS). ESS data are collected biannually in lengthy face-to-face interviews in the language of the respective country.

I only include respondents who possess the legal citizenship of the country at the time of the interview in my sample. I do so because my argument is about interpretive effects of immigration policy on people who are not the target group of immigration policy, namely, legal citizens. After including legal citizens only, the overlap of the IMPIC with the ESS allows me to cover a sample of 182,276 individuals across 23 European countries and 5 years (2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010). Table 2 provides an overview of the sample.

The outcome variable is political trust, which I measure with items on how much trust the respondents have in their country’s politicians and parliament. The items range from 0 (‘no trust at all’) to 10 (‘complete trust’), and I calculated the mean score on both items (scale reliability: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84). The resulting political trust index ranges from 0 to 10, with higher values indicating more political trust.

To capture immigration attitudes as moderator, I estimate the respondents’ mean score on six items. Three relate to what extent respondents agree that immigrants with the same race/ethnicity, a different race/ethnicity, or immigrants from poorer countries should be allowed to live in the country (4-point scale each, ranging from 1 ‘allow many’ to 4 ‘allow none’). Three other items refer to what extent respondents think that immigration is bad/good for the country’s economy, undermines/enriches the country’s cultural life, and whether it makes the country a better/worse place to live (11-point scale each, ranging from 0 to 10). To ease interpretation, the resulting immigration attitude index was transformed to range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a stronger anti-immigration attitude.

To measure political information seeking as additional moderator I include two separate indicators. The first is the respondents’ level of political interest (4-point scale, ranging from 1 ‘very interested’ to 4 ‘not at all interested’). Political interest is taken to account for seeking political information as it indicates the extent to which a person is self-motivated to learn about general issues of political relevance (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996, p. 175; Fraile and Iyengar 2014, p. 282; Galston 2001, p. 222). The second indicator is political news exposure, i.e., the amount of time a person spends seeking information about news/politics and current affairs, which is gauged by measuring the respondents’ mean scores on three items. These items are the amount of time a person spends an average weekday on watching the tv, listening to the radio, and reading the newspaper to receive information about news/politics/current affairs (8-point scale each, ranging from 0 ‘no time at all’ to 7 ‘more than 3 h’). Exposure to political news has been found to predict political knowledge (Vettehen et al. 2004).

Summary statistics on the outcome variable and the moderator variables are presented in Table 1 and Table A3–A5 in the Online Appendix, and question wordings are shown in Table A2 in the Online Appendix.

Statistical models

Five years of the ESS [2002–2010] were merged with the IMPIC data [2001–2009]. More precisely, ESS data from the respective survey year were matched with IMPIC data from 1 year prior to the survey year. For instance, ESS data from 2002 were matched with IMPIC data from 2001 and ESS data from 2004 were matched with IMPIC data from 2003, and so on. By matching ESS survey-year data with IMPIC data from 1 year prior to the survey year, I intend to prevent potential reverse causality, namely, that political trust may impact the degree of immigration policy restrictiveness.

The structure of the data is time-series cross-sectional. To deal with this data structure I estimate multilevel regression models, as recommended by Gelman and Hill (2009, p. 246). In order to account for clustering in the data and for correct estimation of the standard errors, I follow Schmidt-Catran and Fairbrother’s (2016) advice to include random effects at all contextual levels. I adopt their recommendation to apply a statistical modeling technique, in which country-years are cross-classified within countries and years, and individuals are nested in country-years. According to the authors, this technique results in a full model that principally accounts for all potential statistical dependencies and contains a level for every type of variable (Schmidt-Catran and Fairbrother 2016, pp. 25–26).

In a range of multilevel models, my arguments on the relationship between immigration policy congruence and political trust and on the moderating role of political information seeking are tested. All of my multilevel models incorporate a full set of control factors at individual and contextual level. Individual-level controls consist of a standard series of factors, which have been identified in other studies to influence political trust. These are the respondents’ years of age, gender, years of education, area of living, employment status, migration status, political ideology, and feeling about the household’s income (e.g., de Vroome et al. 2013; Ziller and Helbling 2017).Footnote 3 See Tables A3–A5 in the Online Appendix for summary statistics on all individual-level control variables. At contextual level, all models incorporate time-varying factors on the respective country’s gross-domestic product per capita (in current US$), unemployment rate (in percent of total labor force), and foreign-born population (as a percentage of the population), which all may exert a direct impact on the respondents’ political trust levels. With the exception of the variable for the foreign-born population, all of these contextual control variables are matched with ESS data at the year of the survey. In order to avoid potential reverse causality of political trust on the share of the foreign-born population, this variable was lagged by 1 year. See Table A6 in the Online Appendix for summary statistics on all country-level control variables and Table A7 in the Online Appendix for sources.

In summary, all of the multilevel models incorporate a full set of individual-level and contextual-level control variables and random effects in order to account for clustering in the data. Also, for the reason mentioned above, only legal citizens of the respective country are included in the sample of the models.

In a first multilevel model, the average effect of the immigration policy indicator on political trust is tested. In addition to individual-level and country-level controls, it incorporates the immigration policy indicator, the variable for the respondents’ immigration attitudes, but no interaction terms. The size of the variance inflation factor does not indicate multicollinearity among the explanatory variables. Furthermore, a random slope for the respondents’ immigration attitudes is included. It allows the effect of the respondents’ immigration attitudes to vary across country-years. In so doing, this model accounts, for example, for the possibility that there is a strong negative relationship between immigration attitudes and political trust in countries with a rapid increase of the share of immigrants or the unemployment rate. A likelihood-ratio test confirms that the model is improved by the inclusion of the random slope.

Second, I interact the immigration policy indicator with immigration attitudes (i.e., 2-way interaction) to test my main argument about the extent to which the degree of congruence of immigration policy outputs affects political trust. Again, a full set of individual and contextual level controls, and a random slope for immigration attitudes are included.

Third, I interact the immigration policy indicator with immigration attitudes and with variables capturing individual political information seeking (i.e., 3-way interactions). This way, I can test whether immigration policy congruence effects on political trust are particularly pronounced among individuals with pro-/anti-immigration attitudes who also exhibit high levels of political information seeking. In other words, this allows me to investigate to what extent the seeking of political information influences the degree to which immigration attitudes moderate the effect of immigration policy on political trust. To do so, I estimate two specific 3-way interactions, which each include (in addition to the immigration policy and immigration attitude measures) either political interest or political news exposure, which serve as indicators for political information seeking (see discussion in “Individual-level data” section). To prevent multicollinearity, only one interaction term is included at a time. In addition to the full set of individual and contextual level controls and a random slope for immigration attitudes, I also include random slopes for political interest and political news exposure, respectively, in the corresponding regressions. It allows the effect of the respondents’ political interest and political news exposure to vary across country-years. In so doing, the models account, for example, for the possibility that there is a strong negative relationship between political interest or media exposure, respectively, with political trust in countries with a rapid increase of the share of immigrants. A likelihood-ratio test confirms that the models are improved by their inclusion.

Because I have little interest in the control variables, I only discuss the coefficient estimate of the policy indicator, and the interaction terms graphically. Full model details are available in the Online Appendix. Furthermore, to ease interpretation of the regression models, all dummy variables are set to zero, and all interval-scaled individual-level independent variables are centered at the total grand mean. Thus, the individual manifestations of the interval-scaled individual-level independent variables indicate the deviations from the total mean value.

Results

What is the impact of the congruence of government immigration policy with peoples’ immigration preferences on their level of trust in political institutions? As a first step to answering the question, regression Model 1 incorporates the immigration policy measure, the immigration attitude measure and all control factors, but no interaction terms (see Table A8 in the Online Appendix for full regression outputs). The model predicts that the average level of political trust of a regular citizen is 3.8 on a 0–10 scale.Footnote 4 Moreover, the model shows that the level of restrictiveness of government immigration policy outputs alone does not affect the level of political trust of an average citizen to a statistically and substantively significant extent.

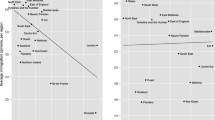

How does the degree of congruence of immigration policy with citizens’ immigration preferences impact their political trust (i.e., hypotheses H1a and H1b)? To answer this question, Model 2 incorporates, in addition to the control factors, a term for the 2-way cross-level interaction between immigration policy and immigration attitudes (see Table A8 in the Online Appendix for full regression outputs). The interaction term is statistically significant. Figure 1 presents the substantive meaning of the interaction, using the estimates from Model 2. It illustrates the degree to which a person’s attitude to immigration moderates the association between government immigration policy outputs and her political trust. In the figure, pro-immigration attitudes are fixed at 2 standard deviations below the mean value and anti-immigration attitudes at 2 standard deviations above the mean value. Recall that the immigration policy indicator is divided into quartiles, with quartile 1 representing the most liberal immigration policy values and quartile 4 the most restrictive immigration policy values.

As is observed from Fig. 1, where the line for anti-immigration attitudes (= gray line) is upward sloping, the line for pro-immigration attitudes is downward sloping (= black line). The figure reveals that for immigration opponents restrictive immigration policies are associated with higher political trust and liberal immigration policies with lower political trust, while the opposite applies to immigration supporters. Whereas the former finding is in line with what related studies found (Jeannet 2019; McLaren 2011; Rocha et al. 2015), the latter is more novel. Both effects correspond to what I assumed in hypotheses H1a and H1b, respectively. Nevertheless, both slopes are not steep: For people who oppose (support) immigration, a change from the most liberal to the most restrictive immigration policy increases (decreases) political trust by only 0.29 points (0.27 points) on an 11-point scale. Therefore, the effects are substantively negligible and support the hypotheses insufficiently. Thus, the congruence of government immigration policy with the interests of citizens with pro- or anti-immigration attitudes does not substantively impact the level of political trust of these groups.

Turning to hypothesis H2, to what extent does the impact of the interaction between immigration policy and immigration attitudes on political trust vary by the degree of individual political information seeking? For that purpose, Models 3–4 incorporate each a coefficient for the 3-way cross-level interaction between immigration policy, immigration attitudes, and one of the two indicators for political information seeking (i.e., political interest and political news exposure, respectively; see Table A9 in the Online Appendix for full regression outputs). Graphical interpretations of these 3-way interactions show that the interaction including political news exposure is substantively meaningful, whereas the interaction incorporating political interest is not. For that reason, only the graph for the former is presented in the following (see Fig. 2 below), while a graph for the latter can be viewed in the Online Appendix (i.e., Figure A2).

Illustration of the conditional effect of immigration attitudes & political news exposure on political trust (3-way interaction). Note Shows the predicted effect of immigration policy on political trust at pro-immigration attitudes & low/high levels of political news exposure, and at anti-immigration attitudes & low/high levels of political news exposure, with 95% confidence intervals. Predictions are based on Model 4 in Table A9 in Online Appendix. Immigration policy restrictiveness on x-axis divided into four quartiles, with quartile 1 representing the most liberal immigration policy values and quartile 4 the most restrictive immigration policy values. Pro- and anti-immigration attitudes fixed at 2SDs below and above the mean, respectively. Low level of political news exposure is fixed to 0 and high level of political news consumption to 7 of the 0–7 scale

Figure 2 presents the substantive meaning of the interaction, using the estimates from Model 4. It illustrates how political news exposure conditions the moderation effect of immigration attitudes on the association between immigration policy and political trust. For Fig. 2, a low level of political news exposure is fixed to 0 (‘No time at all’) and a high level to 7 (‘More than 3 h’) of the 0–7 scale.

The lines for the combination of pro-immigration attitudes with either low (= circle symbol) or high levels (= square symbol) of political news exposure are both only weakly downward sloping, and the line for the combination between anti-immigration attitudes and low levels of political information seeking (= diamonds symbol) is leveled. However, the line for the combination of anti-immigration attitudes with high levels of political news exposure (= triangle symbol) is upward sloping to a substantive extent. This means that for people with strong anti-immigration attitudes and a high degree of exposure to political news, a change from liberal to restrictive immigration policy increases political trust by a meaningful 1.3 points. Thus, while political information seeking moderates the conditional effect of anti-immigration attitudes on political trust, this is not the case for pro-immigration attitudes. This corroborates hypothesis H2, but only for respondents with anti-immigration attitudes.

On a more cautionary note, however, this substantively large effect only prevails when the policy knowledge proxy is set to its extremes, and the immigration attitude variable as well (i.e., ± 2 SDs). The substantial effect becomes much smaller when a high level of news exposure is set to 3 (‘More than 1 h, up to 1.5 h’) instead of 7 (‘More than 3 h’), the former still being a considerable amount of political news consumption for an average weekday. Then the increase in political trust for people with anti-immigrant attitudes is only 0.55 points, which is not substantively different from the effect shown in Fig. 1, where the respondents’ political information seeking behavior is unaccounted for (Figure A3 in the Online Appendix).

In summary, the results reveal that immigration policy (in-)congruence (decreases) increases political trust, but only for people with very strong anti-immigration views and a very high degree of political news exposure, representing only a small segment of society.

Robustness

I test the stability of the results presented in Figs. 1, 2 and Figure A2 in Online Appendix with a series of robustness tests and additional controls (see Tables A10 to A16 in the Online Appendix for the model output; graphical interpretations not shown).

The first goal of these analyses is to ascertain whether the effects are robust across different dimensions of immigration policies (i.e., external and internal)Footnote 5 and immigration policy areas (i.e., family reunification policies, labor migration policies, and asylum policies). Then, the second goal is to find out whether the results of the study remain the same when also legal citizens with immigration background are included. Finally, in order to test the sensitivity of the results, I run models without country-level controls and then successively add them (i.e., first the foreign-born population, then gross-domestic product per capita, and then the unemployment rate). Lastly, but exclusively for the 3-way interactions in which the composite indicator for political news exposure is used, I test whether the results remain robust when radio listening is excluded from the indicator. This is because the latter may reflect the individual's age (with older respondents tending to have higher levels of radio consumption) rather than political information seeking.

The results from Fig. 1 (i.e., 2-way interaction) remain robust in these alternative models: When graphically examined the substantively minor interaction effect between immigration policies and immigration attitudes on political trust remains, with small variations, the same. This is the case when alternative immigration policy indicators are used (see Table A10 in the Online Appendix), when all legal citizens are included in the models (see Table A11 in the Online Appendix), and when country-level controls are included in the models consecutively (see Table A12 in the Online Appendix).

The findings for the 3-way interactions with the political information seeking indicators from Figure A2 in the Online Appendix (i.e., political interest) and Fig. 2 (i.e., political news exposure) also remain robust in these alternative models. To start with, the 3-way interaction effect including political interest remains substantively insignificant in all alternative specifications (see Tables A14–A16) in the Online Appendix. The 3-way interaction effect including political news exposure is mostly confirmed in the alternative analyses. First, disaggregated analyses show that the interaction effect remains substantively large with most but not all of the alternative immigration policy indicators: They indicate that policy effects are more attributable to internal immigration policy, labor migration policy and asylum policy, but less to external immigration policy, and family reunification policy (see Table A14 in the Online Appendix). Second, the effects remain robust with minor variations when all citizens are included (see Table A15 in the Online Appendix), and also third, when country-level controls are included in the models consecutively (see Table A16 in the Online Appendix). Fourth, when radio listening is excluded from the political information seeking composite indicator, the effect size becomes substantively a little smaller but remains robust (see Table A13 and Figure A4 in the Online Appendix).

Discussion and conclusion

That citizens’ substantive interests and preferences are in line with the policies enacted by government is a key element of democratic representation (Pitkin 1967). Yet, the contexts in which governments govern are changing, forcing governments to sometimes prioritize ‘responsibility’ over ‘representation’ (Mair 2009). This pertains particularly to the issue of immigration policy, where external pressures arising from constitutionalism and international interdependencies urge governments to liberalize immigration policies, thus systematically neglecting public demands for restrictions (e.g., Hampshire 2013).

Starting from the assumptions that political trust in institutions is a crucial yardstick for the political well-being of a democracy and that it is influenced by citizens’ evaluations of substantive representation, this contribution sought answering the question to what extent political trust is impacted by the extent to which immigration policies in a country are in line with citizens’ preferences. Answering this question is highly instructive for our understanding of how immigration policies impact citizens’ political trust in a political context in which it becomes more difficult for governments to represent (Armingeon and Lutz 2019; Mair 2009).

I have argued that immigration policy impacts political trust through citizens’ perceptions of (in-)congruence and that citizens’ efforts to seek political information strengthen this effect.

In this study, I have shown that, first, immigration policy has no substantive effect on political trust, neither for opponents nor for supporters of immigration. But I find, secondly, that immigration policies impact the political trust of people who are highly anti-immigration and at the same time very strongly seeking political information. For them, liberal (restrictive) immigration policy reduces (increases) political trust substantively. This finding adds important evidence to the literature that investigates how migrant policies and immigration impact political trust (e.g., Citrin et al. 2014; Jeannet 2019).

I conclude that immigration policy congruence does impact political trust but that it is limited in scope to a small segment of society who is very strongly anti-immigration and also very well politically informed (i.e., rejection of Hypotheses H1a and H1b; partial support for Hypothesis H2). As this amounts to a small part of the population, I suggest that the effect of the congruence between government immigration policy outputs and citizens’ preferences on political trust is moderate at best.

Overall, when viewed from the angle of the broader literature, immigration policy congruence plays a rather limited role when it comes to political trust.

This finding on policy effects stands in contrast to studies that find the effects of immigration policy outcomes, that is asylum applications and deportation rates, on political trust (Harteveld et al. 2018; Rocha et al. 2015). But it is also more in line with Jeannet (2019), who finds a moderate effect of countries’ migrant stock on political trust. All in all, it appears that legal regulations are less visible and traceable to the public than their outcomes, thus having a comparably smaller effect on political trust. The results of my study are also at odds with my assumption (see Introduction) that immigration policies impact political trust more strongly than migrant policies (i.e., integration and multiculturalism policies). But this question cannot be conclusively resolved because the existing studies which find that migrant policies affect political trust do only investigate the indirect moderating role of these policies (Citrin et al. 2014; Hooghe and de Vroome 2015; McLaren 2016).

Second, the findings show that immigration policy congruence affects the political trust of immigration opponents but not of proponents. These findings are in line with Harteveld et al. (2018, pp. 173–174), who have similar results for the effects of the number of asylum applications on political trust. My finding is also in line with the ‘liberal paradox’ (e.g., Hampshire 2013), based on which I expected a stronger impact on the political trust of immigration opponents compared to proponents (see “Immigration policy congruence and political trust” section).

Third, the findings put in perspective the assumption that a lack of substantive representation on immigration is detrimental for liberal representative democracy (e.g., Freeman et al. 2013). The evidence presented here implies that ‘responsible’ immigration policies (Armingeon and Lutz 2019) that are not in line with the demands of citizens favoring restrictions, do not substantively reduce institutional trust – at least not at individual level and in short term.

Fourth, the results of this contribution do not generally question the relevance of objective indicators of policy outputs or government performance vis-à-vis subjective indicators as determinants of political trust (see for discussions Kumlin 2014; van der Meer 2017b). This study included political information seeking indicators, that have been found in previous studies to correlate with policy knowledge (e.g., Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996) and/or to moderate congruence effects on political support (Stecker and Tausendpfund 2016), as moderating variables. Thus, the moderate policy effect found in my study may indicate the actual limited relevance of immigration policy outputs for citizen political trust – rather than questioning the role of objective measures per se.

While this study helps to understand more how immigration policy (outputs) impact(s) political trust in institutions, it also has some limitations. First, a frequent limitation of research examining policy effects is that it studies the effects of strongly aggregated indicators. Finding moderate effects with an objective indicator does not exclude that subjective indicators cannot have more substantive effects (e.g., van der Meer 2017a). Second, the study is limited due to the fact that the timespan of the immigration policy data that are used is limited until 2010, where immigration was less salient compared to 2015, the start of the so-called ‘European refugee policy crisis,’ and after. Third, the study implicitly assumes that the respondents consider the issue of immigration important, which is a condition for immigration policy (in-)congruence to influence their political trust. In that regard, it is a limitation of the study that it cannot explicitly measure subjective issue salience and that the relative influence of immigration policy in comparison to other public policies cannot be gauged. Thus, salience is an untested assumption and the results are therefore also context-specific and cannot be readily applied to other time periods. Lastly, the political information seeking indicator that is used does not contain information about certain news outlets or social media use, which may play a more specific role in interpretive policy effects on political trust.

Besides dealing with these problems of measurement, prospective studies could investigate under which conditions immigration policies may impact political trust more substantively. These could be for instance the increased salience of certain policy areas or specific policies. Moreover, it is also possible that the impact on trust is larger if policies do not reach promised goals (Czaika and de Haas 2013) or when politicians are perceived to talk tough on immigration but act weakly on it (Lutz 2021). We also need to explore whether immigration policy effects on political trust are more negative if there is already a low repertoire of political trust at country level.

It becomes clear that the salient discussions on the relationship between immigration (policy) and democracy require more rigorous empirical research.

Change history

23 March 2023

Placement of Table 2 was incorrect in PDF version. Now, it has been moved to the section Individual-level data.

Notes

The concept of ideological congruence differs from responsiveness. Whereas the former conceptualizes substantive representation as static, the latter conceptualizes it as dynamic (Golder and Ferland 2017, 216).

During the first decade of the 2000s, cultural issues such as immigration challenged the political salience of economic issues (Kriesi et al. 2006, 2012). Public and media attention was focused on the perceived failure of integration policies to integrate former migrant workers and their families, leading to salient discussions about the introduction of selective immigration policies (Doomernik et al. 2009) and stricter controls for undocumented migrants (van Mol and de Valk 2016).

Details on the coding of the individual-level control variables: years of age (i.e., the respondents’ age in years), gender (male = 0; female = 1), years of education (i.e., years of full-time education completed), area of living (small/middle town = 0; Rural area or village = 1; Large town = 2), employment status (employed = 0; unemployed = 1), migration status (0 = native born with native background; 1 = second-generation immigrants; 2 = first-generation immigrants), political ideology (11-point scale, ranging from 0 ‘left’ to 10 ‘right’), and feeling about one’s household’s income (4-point scale, ranging from 1 ‘living comfortably on present income’ to 4 ‘very difficult on present income’).

Recall that due to centering the continuous individual-level variables at the total grand mean and setting the individual-level dummy variables to zero, the constant in all regression models represents the average level of political trust for a citizen that is 47 years of age, male, has 12 years of education, lives in a small/middle town, is employed, is native born with native background, has an on average political ideology (5.1 on a scale ranging from 0 ‘left’ to 10 ‘right’), on average immigration attitudes (0.5 on a scale ranging from 0 to 1), and an on average feeling about her household’s income (1.99 on a scale ranging from 1 ‘living comfortably on present income’ to 4 ‘very difficult on present income’).

For an explanation of the meaning of these indicators see “Measure of immigration policy” section and Table A1. Moreover, all alternative indicators were lagged by 1 year and, because they are also right-skewed, were divided into quartiles.

References

Achen, Christopher H., and Larry M. Bartels. 2016. Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Armingeon, Klaus, and Philipp Lutz. 2019. Muddling between Responsiveness and Responsibility: The Swiss Case of a Non-Implementation of a Constitutional Rule. Comparative European Politics 18: 256–280.

Campbell, Andrea Louise. 2012. Policy Makes Mass Politics. Annual Review of Political Science 15 (1): 333–351.

Citrin, Jack, Morris Levy, and Matthew Wright. 2014. Multicultural Policy and Political Support in European Democracies. Comparative Political Studies 47 (11): 1531–1557.

Cook, Fay Lomax, Lawrence R. Jacobs, and Dukhong Kim. 2010. Trusting What You Know: Information, Knowledge, and Confidence in Social Security. The Journal of Politics 72 (2): 397–412.

Czaika, Mathias, and Hein de Haas. 2013. The Effectiveness of Immigration Policies. Population and Development Review 39 (3): 487–508.

De Vries, E. Catherine, and Nathalie Giger. 2014. Holding Governments Accountable? Individual Heterogeneity in Performance Voting. European Journal of Political Research 53 (2): 345–362.

de Vroome, Thomas, Marc Hooghe, and Sofie Marien. 2013. The Origins of Generalized and Political Trust among Immigrant Minorities and the Majority Population in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review 29 (6): 1336–1350.

Delli Carpini, Michael X., and Scott Keeter. 1996. What Americans Know about Politics and Why It Matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dennison, James. 2020. How Issue Salience Explains the Rise of the Populist Right in Western Europe. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 32 (3): 397–420.

Doomernik, Jeroen et al. 2009. No Shortcuts: Selective Migration and Integration: A Report to the Transatlantic Academy. Transatlantic Academy Paper Series.

Easton, David. 1965. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ford, Robert, Will Jennings, and Will Somerville. 2015. Public Opinion, Responsiveness and Constraint: Britain’s Three Immigration Policy Regimes. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (9): 1391–1411.

Fraile, Marta, and Shanto Iyengar. 2014. Not All News Sources Are Equally Informative: A Cross-National Analysis of Political Knowledge in Europe. The International Journal of Press/politics 19 (3): 275–294.

Freeman, Gary P., Randall Hansen, and David L Leal. 2013. Introduction: Immigration and Public Opinion. In Immigration and Public Opinion in Liberal Democracies, Routledge Research in Comparative Politics, eds. Gary P. Freeman, Randall Hansen, and David L. Leal.

Galston, William A. 2001. Political Knowledge, Political Engagement, and Civic Education. Annual Review of Political Science 4: 217–234.

Gelman, Andrew, and Jennifer Hill. 2009. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models, 11th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gingrich, Jane. 2014. Visibility, Values, and Voters: The Informational Role of the Welfare State. The Journal of Politics 76 (2): 565–580.

Givens, Terri, and Adam Luedtke. 2005. European Immigration Policies in Comparative Perspective: Issue Salience, Partisanship and Immigrant Rights. Comparative European Politics 3 (1): 1–22.

Golder, Matt, and Benjamin Ferland. 2017. Electoral Systems and Citizen-Elite Ideological Congruence. In The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems, ed. Erik S. Herron, Robert J. Pekkanen, and Matthew S. Shugart, 213–245. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Golder, Matt, and Jacek Stramski. 2010. Ideological Congruence and Electoral Institutions. American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 90–106.

Grande, Edgar, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2012. The Transformative Power of Globalization and the Structure of Political Conflict in Western Europe. In Political Conflict in Western Europe, ed. Hanspeter Kriesi, et al. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hainmueller, Jens, and Daniel J. Hopkins. 2015. The Hidden American Immigration Consensus: A Conjoint Analysis of Attitudes toward Immigrants. American Journal of Political Science 59 (3): 529–548.

Hakhverdian, Armen, and Quinton Mayne. 2012. Institutional Trust, Education, and Corruption: A Micro-Macro Interactive Approach. Journal of Politics 74 (3): 739–750.

Hampshire, James. 2013. The Politics of Immigration: Contradictions of the Liberal State. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hardin. 1999. Do We Want Trust in Government? In Democracy and Trust, 22–41. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harteveld, Eelco, Joep Schaper, Sarah L. De Lange, and Wouter Van Der Brug. 2018. Blaming Brussels? The Impact of (News about) the Refugee Crisis on Attitudes towards the EU and National Politics. Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1): 157–177.

Heath, Anthony F., and Lindsay Richards. 2019. How Do Europeans Differ in Their Attitudes to Immigration? Findings from the European Social Survey 2002/03–2016/17. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers (222), 1–40.

Heath, Anthony F., and James R. Tilley. 2005. British National Identity and Attitudes towards Immigration. International Journal on Multicultural Societies 7 (2): 119–132.

Helbling, Marc, Liv Bjerre, Friederike Römer, and Malisa Zobel. 2017. Measuring Immigration Policies: The IMPIC Database. European Political Science 16 (1): 79–98.

Helbling, Marc, Stephan Simon, and Samuel D. Schmid. 2020. Restricting Immigration to Foster Migrant Integration? A Comparative Study across 22 European Countries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (13): 2603–2624.

Hetherington, Marc J. 2004. Why Trust Matters. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hetherington, Marc J. 1998. The Political Relevance of Political Trust. American Political Science Review 92 (04): 791–808.

Hooghe, Marc, and Thomas de Vroome. 2015. How Does the Majority Public React to Multiculturalist Policies? A Comparative Analysis of European Countries. American Behavioral Scientist 59 (6): 747–768.

Inglehart, Ronald. 1999. Postmodernization Erodes Respect for Authority, but Increases Support for Democracy. In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government, ed. Pippa Norris, 236–272. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jeannet, Anne-Marie. 2019. Immigration and Political Distrust in Europe: A Comparative Longitudinal Study. European Societies 15 (2): 1–20.

Knill, Christoph, and Jale Tosun. 2011. Policy-Making. In Daniele Caramani, ed. Comparative Politics, 496–517. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kriesi, Hanspeter, et al. 2006. Globalization and the Transformation of the National Political Space: Six European Countries Compared. European Journal of Political Research 45 (6): 921–956.

Kriesi, Hanspeter, et al. 2012. Restructuring the National Political Space: The Supply Side of National Electoral Politics. In Political Conflict in Western Europe, ed. Hanspeter Kriesi, et al., 96–126. Cambridge: Cambrdige University Press.

Kumlin, Staffan. 2014. Informed Performance Evaluation of the Welfare State? Experimental and Real-World Findings. In How Welfare States Shape the Democratic Public, Globalization and Welfare Series, ed. S. Kumlin and I. Stadelmann-Steffen, 289–310. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lahav, Gallya. 1997. Ideological and Party Constraints on Immigration Attitudes in Europe. Journal of Common Market Studies 35 (3): 377–406.

Levi, Margaret, and Laura Stoker. 2000. Political Trust and Trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science 3 (1): 475–507.

Liu, Christopher, and Di Stolle. 2017. Social Capital, Civic Culture and Political Trust. In Handbook on Political Trust, eds. Sonja Zmerli and Tom van der Meer. Cheltenham.

Luskin, Robert C. 1990. Explaining Political Sophistication. Political Behavior 12 (4): 331–361.

Lutz, Philipp. 2021. Reassessing the Gap-Hypothesis: Tough Talk and Weak Action in Migration Policy? Party Politics 27 (1): 174–186.

Mair, Peter. 2009. Representative versus Responsible Government. MPIfG Working Paper (8): 1–19.

Marien, Sofie. 2011. Measuring Political Trust Across Time and Space. In Political Trust. Why Context Matters, ed. Marc Hooghe and Sonja Zmerli, 13–46. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Marien, Sofie. 2017. The Measurement Equivalence of Political Trust. In Handbook on Political Trust, ed. Sonja Zmerli and Tom van der Meer, 89–103. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Marien, Sofie, and Marc Hooghe. 2011. Does Political Trust Matter? An Empirical Investigation into the Relation between Political Trust and Support for Law Compliance. European Journal of Political Research 50 (2): 267–291.

McLaren, Lauren. 2011. Immigration and Trust in Politics in Britain. British Journal of Political Science 42 (01): 163–185.

McLaren, Lauren. 2015. Immigration and Perceptions of National Political Systems in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McLaren, Lauren. 2016. Immigration, National Identity and Political Trust in European Democracies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (3): 379–399.

Messina, Anthony M. 2007. The Logics and Politics of Post-WWII Migration to Western Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mettler, Suzanne, and Joe Soss. 2014. The Consequences of Public Policy for Democratic Citizenship: Bridging Policy Studies and Mass Politics. Perspectives on Politics 2 (1): 55–73.

Mishler, W., and R. Rose. 2001. What Are the Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies. Comparative Political Studies 34 (1): 30–62.

Morales, Laura, Jean-Benoit. Pilet, and Didier Ruedin. 2015. The Gap between Public Preferences and Policies on Immigration: A Comparative Examination of the Effect of Politicisation on Policy Congruence. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (9): 1495–1516.

Noordzij, Kjell, Willem De Koster, and Jeroen Van Der Waal. 2021. The Micro-Macro Interactive Approach to Political Trust: Quality of Representation and Substantive Representation across Europe. European Journal of Political Research 60 (4): 954–974.

Norris, Pippa. 1999. Introduction: The Growth of Critical Citizens? In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government, 1–27. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Norris, Pippa. 2011. Democratic Deficit. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, Pippa. 2017. The Conceptual Framework of Political Support. In Handbook on Political Trust, ed. Sonja Zmerli and Tom van der Meer, 19–32. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Otjes, Simon. 2018. What’s Left of the Left-Right Dimension? Why the Economic Policy Positions of Europeans Do Not Fit the Left-Right Dimension. Social Indicators Research 136 (2): 645–662.

Paul, Hannah L., and Jennifer Fitzgerald. 2021. The Dynamics of Issue Salience: Immigration and Public Opinion. Polity 53 (3): 370–393.

Pierson, Paul. 1993. When Effect Becomes Cause: Policy Feedback and Political Change. World Politics 45 (04): 595–628.

Pitkin, Hanna Fenichel. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Reher, Stefanie. 2015. Explaining Cross-National Variation in the Relationship between Priority Congruence and Satisfaction with Democracy. European Journal of Political Research 54 (1): 160–181.

Rocha, Rene R., Benjamin R. Knoll, and Robert D. Wrinkle. 2015. Immigration Enforcement and the Redistribution of Political Trust. The Journal of Politics 77 (4): 901–913.

Schmid, Samuel D., and Marc Helbling. 2016. Validating the Immigration Policies in Comparison (IMPIC) Dataset. WZB Discussion Paper (SP VI 2016–202): 1–35.

Schmidt-Catran, Alexander W., and Malcolm Fairbrother. 2016. The Random Effects in Multilevel Models: Getting Them Wrong and Getting Them Right. European Sociological Review 32 (1): 23–38.

Stecker, Christian, and Markus Tausendpfund. 2016. Multidimensional Government-Citizen Congruence and Satisfaction with Democracy. European Journal of Political Research 55 (3): 492–511.

van der Meer, Tom. 2017a. Economic Performance and Political Trust. In The Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust, ed. Eric M. Uslaner. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van der Meer, Tom. 2017b. Political Trust and the ‘Crisis of Democracy.’ Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-77 (November 22, 2017b).

van der Meer, Tom, and Sonja Zmerli. 2017. The Deeply Rooted Concern with Political Trust. In Handbook on Political Trust, ed. S. Zmerli and Tom van der Meer, 1–15. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

van Mol, Christof, and Helga de Valk. 2016. Migration and Immigrants in Europe: A Historical and Demographic Perspective. In Integration Processes and Policies in Europe, ed. Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas and Rinus Penninx, 31–56. Cham: Springer.

Vettehen, Paul G.J. Hendriks., C.P.M. Hagemann, and L.B. Van Snippenburg. 2004. Political Knowledge and Media Use in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review 20 (5): 415–424.

Wright, Matthew. 2011. Diversity and the Imagined Community: Immigrant Diversity and Conceptions of National Identity. Political Psychology 32 (5): 837–862.

Ziller, Conrad, and Marc Helbling. 2017. Antidiscrimination Laws, Policy Knowledge and Political Support. British Journal of Political Science 1: 1–18.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The article has benefited substantially from generous feedback by Jeyhun Alizade, Marc Helbling, Sebastian Jungkunz, Jonathan Latner, Taeku Lee, Philipp Lutz, Samuel Schmid, Caroline Schultz, Carsten Schwemmer, Ulrich Sieberer, and Maarten Vink. I also thank the participants of the Pillar IV Colloquium at the Bamberg Graduate School of Social Sciences. The two anonymous referees helped with their valuablecomments to improve the article.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Simon, S. Immigration policy congruence and political trust: a cross-national analysis among 23 European countries. Acta Polit 59, 145–166 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-023-00284-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-023-00284-9