Abstract

To what extent does the economic crisis affect support for political protest? Since the outburst of the financial crisis in 2008 many protests have been mobilized against national governments and their austerity policies. In some countries, these actions were described in the media as having little support among the general public, while elsewhere these actions enjoyed significant public support. Surprisingly little scholarly work has examined this variation. We fill this research gap by investigating who approves of austerity protests, how bystanders’ attitudes differ from the activists’ approval of protests and how repertoires relate to the approval of austerity protests. The analysis uses original survey data from nine European countries affected by the recent economic crisis at varying degrees and demonstrates that protest experience, both at the country and individual level, relates to approval of anti-austerity protests. The severity of economic crisis increases is positively related to protest approval in general terms, but there are differences depending on the type of grievances and which forms of austerity protests are considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Numerous protests have been mobilized as a reaction to austerity policies and the Great Recession of 2008: Occupy events in the U.S. and beyond, Indignados in Spain, widespread demonstrations and strikes in Greece since 2010, demonstrations of precarious workers in Italy and Spain, as well as many other larger and smaller protest events all across Europe. Ortiz et al. (2013) noted a significant increase in protests after the adoption of austerity measures across the world. The majority of these events which had common claims referring to austerity policies, unemployment and increasing inequalities have been analysed from the perspective of activists or political decision-makers (Accornero and Ramos Pinto 2015; Anduiza et al. 2013; Bernburg 2015; Della Porta 2015a; Della Porta et al. 2015b; Dodson 2015; Fominaya and Cox 2013; Giugni and Grasso 2015; Kern et al. 2015; Rüdig and Karyotis 2014; Peterson et al. 2015). Despite the large numbers involved in these protests, not everyone was participating in what were often labelled as radical protests, and some did not even approve of them. Even the most encompassing movements did not represent everyone: for example, research has shown that the massive anti-austerity protests of 2010 in Greece involved 30% of the population and were supported by 65% (Rüdig and Karyotis 2014). Similar ratios of protest activists and supporters were also noted in Iceland (Bernburg 2015) and we have similar historical examples of how pacifist mobilization during wartime faced clear disapproval (Barnes and Kaase 1979). Furthermore, disruptive repertoires, such as general strikes in Spain or rioting in the UK, have been shown to backfire and decrease the support for activists and their claims (Elsbach and Sutton 1992).

As individual support for protests might be a predictor of future mobilizations (Ajzen 1988; Ajzen and Fishbein 2005; Barnes and Kaase 1979), better understanding of protest cycles requires knowledge about when bystanders, i.e. those who usually do not participate in protests, approve of protests and if this approval varies between more and less disruptive forms of actions. Bystanders are critical for social movements as the message that is conveyed by demonstrators and the government response the movement seeks, are largely conditioned by the influence of the bystander public (Smith et al. 2001). The relationship between protest and bystanders has been often addressed by scholars focusing on the role of the media (Gamson 2004). In fact, protest does not happen in a void and it scarcely matters if it is not reported: the literature on the relationship between social movements and public opinion has shown how central the impact on public debate is in order to produce significant outcomes (Kriesi 2015) and protests that do not reach bystanders through media coverage have been qualified as “non-events” (Gamson and Wolfsfeld 1993, p. 116). On the other hand, some recent studies from United States, notably Andrews et al. (2016), demonstrate that whites living near the locations where the sit-ins of the Civil Rights Movement took place were more likely to support these actions than those who lived further away. This spatial proximity or experience of protest is also important for our work, which analyzes the individual and contextual factors that shape the way in which bystanders perceive protest; while this article does not focus on how spatial proximity influences how bystanders perceive protest, it contributes to this literature showing how the relationship between movements and public opinion tends to depend on some factors, such as the socio-economic context, individual conditions and the repertoires of action.

Unfortunately, such knowledge is lacking today. This paper fills this research gap by studying who approves of anti-austerity protests, how bystanders’ attitudes differ from the activists’ approval of protests, how the repertoires of protest relate to the approval of austerity protests and how these variations relate to country’s experience of economic crisis.

The few studies which do examine public attitude towards protests do not account for the difference between activists and bystanders (Crozat 1998), and/or rely mainly on data from a few countries in experimental (e.g., Osborne and Sibley 2013) or survey research (Olsen 1968). Our comparative analysis of attitudes towards anti-austerity protests contributes to the literature in three ways: first, we account for contextual determinants of individual level attitudes by using survey data from nine countries which have been affected by the economic crisis to different degrees. The deeply affected Greece, Spain and Italy experienced the highest unemployment rates until 2015; while the least affected Germany, Sweden and Switzerland have had the highest GDP per capita during the crisis period and relatively low unemployment rates (Hofer and Mexi 2014, Eurostat). The three remaining—France, Poland and the UK had lower GDP per capita than the least affected countries in 2015 and lower unemployment rates than the most affected countries at the time of survey (Eurostat 2016). The difference between the three groups of countries is also prevalent if we compare the social inclusion indexes from 2015 (Schraad-Tischler 2015). The crisis-related protest mobilization took more often place in the first (the most severely hit) category of countries, but the protests saw a significant transnational dimension (Kousis 2013), spreading beyond the borders of the most austerity-ridden countries (Sotirakopoulos and Rootes 2013).

Second, we study differences between activists and bystanders in order to disentangle general support for anti-austerity protest from the attitudes of determined activists. This distinction provides a good proxy of general population support towards protest. Third, we investigate how protest repertoires relate to attitudes of protest. While disruptive protests are arguably less accepted by the public, there is little systematic evidence of how bystanders’ and activists’ attitudes vary in this respect, and what explains these differences. This article aims to contribute in filling this gap in the literature, through the analysis of survey data collected in the context of the LIVEWHAT project.

The article is organized as follows: in the next section, we briefly present what we know to date from prior research on attitudes towards protest and then sketch our theoretical expectations and testable hypotheses guiding the data analysis. This is followed by presentation of the data and methods of the analysis. We then discuss our findings and finally present our conclusions.

Public attitudes towards protest: previous research

Studies about citizens’ attitudes towards protest were common in the late 60 and 70 s, when these attitudes were mainly used for predicting protest behaviour (Olsen 1968; Turner 1969; Barnes and Kaase 1979). The majority of these studies were based on data from the U.S. or a few Western European countries and concluded that people “give more weight to the mode of behaviour than issue in whose cause it is adopted” (Barnes and Kaase 1979, p. 64, our emphasis). The mode or repertoire of protests was also important for Crozat (1998) who provides one of the most recent systematic comparative analyses of citizens’ approval of different protest strategies. His study makes an assumption that some forms of action might have more influence on public opinion and thereby also affect bystanders’ approval of these actions. Examining data from two cross-sectional surveys in 1974 and 1990, Crozat demonstrated that general acceptance of protests had decreased in four examined West European countries although the general level of protest activism had increased. Less contentious forms of action such as petitions were more accepted than the more contentious tactics such as civil disobedience (Ibid.). Studies which were even more concerned with the general support for violence argued that the difference in attitudes could be explained by socio–economic variables, as more educated citizens tend to express less support for violent protests than less educated ones (Hall et al. 1986). Others, such as Bernburg (2015), showed that perceived relative deprivation increases support for crisis-related protests in Iceland, but only for those who perceive that they have been affected by the crisis more than others.

Recent research in political psychology demonstrates that relationships behind the approval of protest behaviour are even more complex. With the respect of relative deprivation, the experimental studies have shown that perceptions of a just system decreased participants’ anger, which, in turn, weakened their support for protests (Osborne and Sibley 2013). Similarly, the effect of internal (self) political efficacy on support for protests is conditional to individuals’ evaluation of how just the political system is (Osborne et al. 2015). This resembles the results of one of the few bystanders’ study, where Jeffries et al. (1971) demonstrate that respondents perceived the Watts (racial) riots as “social protest” rather than “a negative disturbance” when they saw activists as worthy and believed the discrimination existed to some degree. These results suggest that system-justifying beliefs, but probably also satisfaction with government policies, help maintain the status quo by dampening the blow of inequality and by reducing the total effect that deprivation might have on approval of protest mobilization. Considering that system-justification beliefs tend to vary more between than within the countries, these results might also explain why Crozat (1998) and Barnes and Kaase (1979) found significant country differences in approval of protests.

These excellent studies on protest approval have, however, neglected the likely difference between activists’ and bystanders’ attitudes towards protest behaviour. Older studies have shown that public support towards protest is particularly relevant for resource-weak bystanders (Eisinger 1973) and that being spectator to a specific event (e.g., a demonstration) might increase approval of other forms of protesting (Berkowitz 1973). Similarly, the likely experience of action or spatial proximity to protest events increased support for sit-ins among bystanders of these actions in the U.S. (Andrews et al. 2016). Fuchs and Rucht find differences in the dynamics of support for specific movements between proponents and opponents of these movements when studying their mobilization potential in the 80’s in Europe in a comparative perspective (Fuchs and Rucht 1992).

Following the aforementioned research and considering that in some countries there were significantly more anti-austerity protests than in other countries (Genovese et al. 2016; Giugni and Grasso 2015), we argue that the effect of individual micro-level factors on approval of anti-austerity protests among activists and bystanders is contingent on protest repertoires and country’s experience of crisis and crisis-related protests.

Theoretical expectations and hypotheses

To test our argument, we focus on three major sets of factors which are expected to affect attitudes towards anti-austerity protests: (1) individual level factors describing the subjective and objective experience of the crisis and the experience of protests, that is a character of an activist or bystander; (2) protest repertoire and (3) contextual differences, particularly the varying severity of economic crisis between three groups of countries.

First, regarding individual level factors, we examine the effects of both subjective perceptions of the crisis, such as retrospective relative deprivation and objective material grievances, such as reduced consumption or worsening job conditions on attitudes towards austerity protests. Similarly to the previous studies on the relationship between relative deprivation and protest mobilization (Gurr 1970; Bernburg 2015), we expect that individuals who perceive themselves as relatively deprived approve of austerity protests more than those who did not feel the effects of the crisis as strongly (Hypothesis 1).

Although there are many studies which emphasize the importance of resources for political participation, less is known about the support of protests. Bernburg (2015) showed that perceived economic loss (i.e. relative deprivation) increases support of protest only if individuals perceive that crisis have affected them more than others, but he did not find any significant effect of individuals’ objective economic situation on protest approval. Although it is likely that protest support, in contrast to participation, is not related to resource availability, the experienced material deprivation as a result of crisis might lead to more supportive attitudes towards anti-austerity protests. Consequently, we expect individuals who have objectively experienced material deprivation (i.e. reduced their consumption or experienced worsened job conditions) because of the crisis to have higher levels of approval of anti-austerity protests as those without such experience (Hypothesis 2).

Based on prior research, in the case of activists and those who did not participate in any of protests, i.e. bystanders, we have a simple expectation that activists approve protests more than bystanders (Hypothesis 3a). Our main argument, however, is that this difference between activists and bystanders is contingent on several factors like the subjective relative deprivation or the experienced material deprivation. According to prior studies it is likely that individuals choose to be bystanders because they lack resources or because they perceive low chances of influencing political change (e.g. low political efficacy) (e.g., Kern et al. 2015). Therefore, it would not be surprising that bystanders who feel more relatively deprived or face significant grievances also discard austerity protests more than non-deprived bystanders. On the other hand, the experience of crisis may increase feelings of solidarity with the anti-austerity protest activists, and in this case bystanders with higher levels of relative and material deprivation would have a higher approval of austerity protests than non-deprived bystanders, but have still lower rates of approval than deprived activists. The “common experience” of crisis might increase bystanders’ tolerance towards protests and therefore we expect that bystanders who perceive relative deprivation or face objective deprivation discard austerity protests more than those bystanders who do not perceive or experience deprivation (Hypothesis 3b).

Second, in respect of protest repertoire, we follow Crozat (1998) who showed that approval of more disruptive repertoires such as occupation and illegal forms of actions is lower than of less disruptive repertoires such as demonstrations or strikes. It is logical to expect that protesters are more likely to approve all types of repertoires because of their own participation or through the anecdotes of close comrades. The varying attitudes of bystanders, on the other hand, need more complex explanation. Bystanders, especially if they are not the spectators of the event, get only mediated accounts of protest events and it is widely known that media-framing of disruptive events is negative (Smith et al. 2001). Therefore, we expect the differences between activists and bystanders in their approval of protest to be larger for occupation and illegal forms of actions than for demonstrations or strikes (Hypothesis 4).

Third, we argue that approval of austerity protests is context dependent. Prior studies showed strong support for protests in severely hit countries such as Iceland (Bernburg 2015) and Greece (Rüdig and Karyotis 2014). Protest experience is known to increase the support for protests and the severely hit countries also had more anti-austerity protests than other countries. Thus, we expect that individuals in countries more severely hit by the economic crisis will be more supportive of protest than those who live in the countries where the crisis was less severe (Hypothesis 5).

Considering that protest experience can affect spectators’ approval of protest mobilization in general, it is also likely that the amount of anti-austerity protests influences bystanders’ approval of protests in crisis-affected countries more than elsewhere. The feelings of solidarity with the activists might also be more likely in crisis-affected contexts. Therefore, we expect that differences in protest approval between protesters and bystanders will be lower in the countries where the crisis was the most severe than in the countries which suffered the least by the crisis (Hypothesis 6).

Finally, cultural traditions and differences in the timing, intensity and political opportunities between countries led to different forms and intensity in public contestation to austerity measures (Genovese et al. 2016). Prior studies, especially Crozat (1998), have demonstrated the low approval of disruptive protest repertoires and it is likely that the experience of crisis and crisis-related protests will not balance out this negative attitude towards disruptive protests. Thus, we expect that crisis severity (country differences) has stronger effect on support for less disruptive actions such as demonstrations, but smaller effect on the approval of more disruptive repertoires such as occupations and illegal action (Hypothesis 7).

Data

We test our hypotheses by using a unique cross-national representative web-based survey data which was collected between June and August of 2015 in nine European countries (France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden and the UK).Footnote 1 As noted above, the countries are divided into three groups—the most affected by crisis (Greece, Italy, Spain), the countries affected by the crisis at medium degree (France, Poland, the UK) and the least affected countries (Germany, Switzerland, Sweden). The survey included questions about protest approval, protest participation as well as respondents perceived relative deprivation, objective material deprivation, political attitudes and demographic background (see Appendix for further details). The models are explained further below, as first we describe our dependent variable—the approval of austerity protests.

Approval of austerity protest in Europe

The survey included the following question “When thinking about austerity policies and their consequences, how strongly do you approve or disapprove the following actions:

-

March through town or stage mass protest demonstrations

-

Take part in strikes

-

Occupy public squares indefinitely

-

Take illegal actions such as blocking roads or damaging public property?

The answers were given in the scale of 0 (strongly disapprove) to 10 (strongly approve), and Fig. 1 demonstrates clear country differences in approval rates.

More contentious forms of actions such as illegal actions are widely disapproved, especially in Germany, Greece, Italy and Switzerland. Demonstrations against austerity policies are more approved in Greece, France and Spain, than in Germany, Switzerland and the UK. Anti-austerity strikes are more approved in Greece, France, Spain and Sweden, but disapproved in the UK and Switzerland. The picture seems to only partially reflect the real mobilization of strikes in these countries, as Genovese et al. (2016, p. 948) show that there were many austerity strikes in Greece and France, while the UK and Sweden had none. Occupying public squares—a clear reference to the Occupy movements, which actions took mainly place not only in the US, but also in the UK—and to the Spanish acampadas, are the most approved in France and Italy, while disapproved in Greece, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK.

In terms of activists and bystanders, our dataset includes almost equal proportions of those who have participated in at least one political action during the last twelve months and those who have not participated in any of the actions. The ratio varies across countries being the largest in Greece (70% protesters vs. 30% bystanders) and the smallest in Poland (35% protesters vs. 65% bystanders).

Model of analysis

We study the variance of approval of protests with individual level indicators of objective and subjective experience of the economic crisis, respondents’ participation in protest and the severity of economic crisis. For testing the hypothesis about the different effects of crisis and status as a bystander, we also use several interaction effects.

The dependent variables are approval of four different repertoires—demonstrations, strikes, occupations and illegal actions, measured as a ten-point scale. Because of our theoretical interest in the varying approval of different protest repertoires we do not use any general index for protest attitudes. Question wordings for dependent, independent and control variables are presented in Appendix 1.Footnote 2

We have three sets of independent variables of interest: (1) the experience of the economic crisis is operationalized as subjective perceptions of relative deprivation (as measured through a retrospective evaluation of household situation as compared to 5 years ago) and objective grievances such as reduced consumption (number of reported reductions in consumption for financial/economic reasons) and bad work conditions (number of conditions of job worsening). Pairwise correlations between the three items are below 0.5, signalling that they can be considered independent conditions; (2) the character of respondent as a protest activist or bystander is operationalized as a reported participation in any anti-austerity protests during the last 12 months before the survey; (3) the context of the economic crisis is measured by grouping countries into three categories: the low severity (Germany, Sweden, Switzerland), medium severity (France, Poland, UK), and high severity (Greece, Italy and Spain).

We also include a set of control variables, which are known to play a role for individuals’ approval of protest actions—these are standard measures for political values, satisfaction with government, sources of cognitive inferences, political discussion and social interaction, socialization and demographic traits (all details are reported in Table 8).

Results: explaining varying support for protest

Descriptive statistics for the variation between approval of protests among activists and bystanders is presented in Table 1.

While it is not unexpected that protest activists have higher rates of approval than bystanders, Table 1 shows that protesters in countries where the crisis was the most severe (Greece, Italy, Spain) are also more approving of the actions than protesters in Germany, Switzerland or Sweden. There seems to be a smaller difference among the bystanders, suggesting that the severity of crisis does not have a uniform effect on individuals’ attitudes towards protests. Furthermore, the severity of the crisis seems to have, both among protesters and bystanders, a stronger effect on approval of demonstrations and strikes than it has on approval on occupations and illegal actions. This is in accordance to our expectations in hypothesis 7 and suggests that the support towards more disruptive protest repertoire may be inhibited by cultural norms which are difficult to break even in a context of economic hardship. However, some more elaborated analysis is needed for testing the proposed relationships between individual and contextual variables and protest support.

Individual level factors

The results presented in Table 2 demonstrate partial support for our first hypothesis regarding individuals’ approval of austerity protests. Individuals, who perceive that their household situation is worsened in comparison to 2010 (retrospective relative deprivation), are more likely to approve of austerity demonstrations and strikes, but discard illegal actions. The approval of occupying squares has no correlation with relative deprivation. These results indicate that protest repertoire plays an important role for protest support and provide partial support to hypothesis 1, but exclusively for less disruptive forms of action.

The second hypothesis regarding objective material deprivation finds more support. Although there is no significant effect of reduced consumption on approval of demonstrations, individuals who reduced their consumption as a result of the crisis tend to disapprove strikes and approve austerity related occupations of squares and illegal actions. The effect of worsened working conditions is more robust—reporting about worsened working conditions relates to higher approval rates for all forms of austerity protests. Hence, objective (reported) experiences of crisis increase protest approval. Consistent with standing theory, the lack of material resources is related to lower levels of protest activism (Kern et al. 2015), and these results call for further analysis on the conditional effects of such economic variables.

Moving further to the differences of protest approval between activists and bystanders, we find clear support for hypothesis 3a across all forms of protests (Table 3). While this could have been expected, we also found a very small proportion of respondents (N = 68) who say that they had participated in a demonstration during the last 12 months but strongly disapproved austerity related demonstrations.

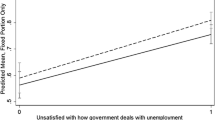

It was also expected that bystanders who perceive relative deprivation or face objective deprivation support austerity protests more than bystanders who do not perceive or experience deprivation (hypothesis 3b). This implies that having experienced the effects of the crisis would moderate the negative attitudes towards protest of bystanders. Our evidence partially supports this expectation as the results vary between the different protest repertoires (Table 4; Fig. 2). Bystanders who perceive relative deprivation show significantly less support for demonstrations and strikes than non-deprived bystanders, but show higher support for occupations and illegal action. Contrarily, the objective (reported) experience of crisis moderates the effect, as bystanders who have reduced their consumption show significantly more support for demonstrations and strikes and less support for occupations and illegal action than bystanders who have not. Bystanders who have experienced worsened job conditions discard all forms of actions more than non-affected bystanders.

Figure 3 makes the conditional effect of protest and crisis experience more explicit—the solid lines for protesters overlap with the dashed lines for bystanders for all protest repertoires and across all crisis effects, evidencing that the difference between activists’ and bystanders’ approval of protests does not depend on perceived relative deprivation or experienced material difficulties as a result of the crisis. Activists do support protests more than bystanders, but higher levels of perceived relative deprivation similarly decrease support of demonstrations among both groups. This means that crisis experience has a more general effect on protest approval than protest experience, and results support those who argue about the role of grievances in protest mobilization (Gurr 1970). Further studies could pay more attention to reasons why bystanders support for protest actions differs from the ones of activists.

Protest repertoires

Table 3 and Fig. 3 suggest that there are some clear differences in protest approval across the repertoires of protest. Bystanders discard all forms of austerity protests more than activists (Table 3), but contrary to our expectations in hypothesis 4, differences between activists and bystanders in their approval of protest are smaller for occupation and illegal forms of actions than for demonstrations or strikes. It is likely that those who were in general supportive towards anti-austerity demonstrations and strikes also participated in these actions, while many who did not join occupations or some illegal protests still felt solidarity with the activists. It should be noted that the general numbers of respondents who have participated in the illegal actions are very small even in our relatively large dataset, and this might affect the relationship for this particular protest repertoire. Our results also suggest that at least in the case of protest approval, the indexes of protest participation which are common in the studies based on survey data (E.g., Kern et al. 2015), might hide some theoretically important differences.

Contextual effects

The differences between the countries which were highly or less severely hit by the crisis are visible in Table 3. We find partial support for hypothesis 5 as individuals in Greece, Italy and Spain were more positive towards austerity related demonstrations than individuals in Germany, Sweden and Switzerland, but we find an opposite effect for occupations and illegal actions and no significant relation in the case of strikes. This seems to suggest that the general crisis experience, prevalence of austerity policies, as well as the experience of protests increases the support of anti-austerity protest only if these take the form of demonstrations and marches. Strikes, which might affect the already weak economy, are discarded. It might well be that German, Swiss and Swedish respondents who supported the austerity related illegal actions or occupations actually thought about the actions taking place in the severely hit countries. Therefore, the comparison between these two set of countries is negative and it might also explain why we find very small difference between activists and bystanders in the case of illegal actions.

Finally, in order to test whether bystanders’ approval of protests is conditional to the severity of the crisis at the country level, we have tested two-way interaction models between demonstrators and bystanders for country contexts (Table 5 and Fig. 4 ). We find support for our expectations in hypothesis 6 as differences in support between protesters and bystanders in countries where the crisis was the most severe are more than five times lower than in the countries which suffered the least by the crisis (ratio between bystanders at the reference category, low severity countries −1.491 and bystanders at the high severity countries −0.279). Looking into the country effects on the type of repertoire, we find no support for hypothesis 7 as there is no clear evidence on how the severity of the crisis relates to the approval of different protest repertoires. We expected the effect to be larger for less disruptive forms of action, but the differences between low, medium and high severity countries have no clear pattern across the forms of actions. It might be that the severe experience of crisis does not compensate for the general disapproval of disruptive repertoires, especially for the case of anti-austerity protests.

Our results indicate that the support for more disruptive forms of political actions is more complex than expected and probably explained by other mechanisms than the approval of demonstrations. Considering the economic costs of strikes, especially the large general strikes which were common is many crisis-affected countries, it is not surprising that the approval of strikes is not explained similarly as the approval of other forms of action.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to explain the individual level differences of protest approval in the countries which were affected by the economic crisis at different degrees, and investigate how the individuals’ experience of crisis and protest events relates to approval of anti-austerity protests. In the context of the European crisis, when protests tend to encompass a wide set of social sectors, addressing society as a whole and mobilizing people much beyond the “usual suspects”, analysing public support of protest is extremely relevant. In particular, the points discussed in this article are central in shaping the chances of success of the political parties who are aiming to translate in the institutional domain the demands of the anti-austerity movements, thus addressing an even wider audience. Furthermore, understanding public support for protest in the particular context of the economic crisis sheds light on the role of contentious politics for changing public attitudes, which is especially important when considering the role that public contestation to austerity policies played in the south of Europe.

The analysis from survey data for nine different European countries allows us to draw some important conclusions regarding the rarely studied public attitudes towards austerity protests. We draw conclusions at the individual and contextual level for two different attitudinal objects: less disruptive (demonstrations and strikes) and more disruptive (occupation and illegal) repertoires.

First, activists approve protests much more than bystanders and differences between them are not entirely related to perceived or objective experience of crisis, but rather to the contextual differences. The perceived worsening of individuals’ economic situation (relative deprivation) and experienced worsening of job conditions do relate to higher levels of protest support, but do not condition the difference between activists and bystanders. Differences between perceived and experienced grievances are important in forming attitudinal responses and it is likely that they relate to more general emotions (anger and/or solidarity), which in turn might explain the increased approval of all kinds of protest repertoires (see also Passarelli and Tabellini 2013; van Stekelenburg et al. 2011).

Second, protest approval is highly related to the repertoire of protests and this emphasizes the importance of analysing the forms of political action—both the individuals’ participation in protest, support of protest, as well as politicians’ reactions to these actions—separately from each other. Looking specifically into more disruptive forms of protest requires additional evidence such as social desirability might be an important factor in sub-reporting support for illegal action. However, our evidence on marginal support for more disruptive forms of action in the cases where individuals are affected by the crisis, highlights the importance of understanding how social attitudes towards the most radical forms are dissent and can be conditioned by individual experiences.

Third, anti-austerity protests have more support in the countries that were most severely hit by the crisis—Greece, Italy and Spain as compared to countries with low levels of economic crisis. Furthermore, the severity of the crisis experienced by the country at large significantly affects the difference in support among activists and bystanders. This calls for further analysis of how protest movements and political parties which mobilize different protest actions have the potential to increase a general public approval of protests by targeting bystanders.

Our study comprises only nine countries, thus limiting our analysis to a great extent. By bundling together different countries according to three levels of severity of the crisis, we also combine other unobserved contextual features which are closely related to the national political culture that may consequently confound our assessment of public attitudes towards protest (e.g. the tradition, public and modes of protest). Nevertheless, the effect of the crisis on approval of anti-austerity protests is not as direct and unequivocal as one might expect. Countries with lower impact of the crisis have high concerns about the EU crisis and also demonstrated in support of the interests of the most affected countries. Furthermore, national political cultures and protest traditions should be relevant in explaining why the support for strikes varies much less than for occupations of squares. Similarly, the widespread approval of austerity protests by French respondents indicates more the cultural importance of protest mobilization than the severity of economic crisis.

In sum, we have shown that the approval of anti-austerity protests by the public in nine European countries is significantly influenced by the experience of economic hardship, both at the collective and at the individual level. Economic crisis increases protest approval in general, but there are differences depending on the type of grievances and on which repertoires of austerity protests are considered. Furthermore, in an attempt to move towards a more nuanced view on protest approval, accounting for the differences between protesters and bystanders, our study points out that the two groups tend to have developed different relationships with protest, as expected from the existing literature. Surprisingly, we found that the effect of the economic crisis, both at the individual level of deprivation and at the contextual level of country conditions, tends to be rather similar in both groups. Economic hardship seems to have a similar effect of protesters and bystanders, broadening the reach of both groups in a homogenous way, rather than impacting on the difference between the two groups in their attitudes towards protest.

Notes

Survey details are presented in the Technical appendix of the Livewhat Integrated report on individual responses to crises deliverable 4.2. available at: http://www.livewhat.unige.ch/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Integrated-Report.pdf.

The economy, Poverty, Education, Unemployment, Healthcare, Precarious employment, Immigration, Childcare.

References

Accornero, G., and P. Ramos Pinto. 2015. ‘Mild mannered’? Protest and mobilisation in Portugal under austerity, 2010–2013. West European Politics 38 (3): 491–515.

Ajzen, I. 1988. Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press.

Ajzen, I., and M. Fishbein. 2005. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The handbook of attitudes, ed. D. Albarracín, B.T. Johnson, and M.P. Zanna, 173–221. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Publishers.

Andrews, K.T., K. Beyerlein, and T.T. Farnum. 2016. The legitimacy of protest: explaining White Southerners’ attitudes toward the civil rights movement. Social Forces 94 (3): 1021–1044.

Anduiza, E., C. Cristancho, and J.M. Sabucedo. 2013. Mobilization through online social networks: the political protest of the indignados in Spain. Information, Communication & Society 17 (6): 750–764.

Barnes, S.H. and M. Kaase. 1979. Political action: Mass participation in five western democracies. Beverley Hills and London: Sage Publications.

Bernburg, J.G. 2015. Economic crisis and popular protest in Iceland, January 2009: The role of perceived economic loss and political attitudes in protest participation and support. Mobilization 20 (2): 231–252.

Berkowitz, W.R. 1973. The impact of anti-Vietnam demonstrations upon national public opinion and military indicators. Social Science Research 2 (1): 1–14.

Crozat, M. 1998. Are the times a-Changin’? Assessing the acceptance of protest in western democracies. In The Social Movement Society: Contentious Politics for the New Century, ed. D.S. Meyer, and S. Tarrow, 59–81. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Della Porta, D. 2015. Social movements in times of austerity: Bringing capitalism back into protest analysis. Cambridge: Polity.

Della Porta, D., M. Andretta, A. Calle, H. Combes, N. Eggert, M. Giugni, J. Hadden, M. Jimenez, and R. Marchetti. 2015. Global justice movement: Cross-national and transnational perspectives. Abingdon: Routledge.

Dodson, K. 2015. Economic threat and protest behavior in comparative perspective. Sociological Perspectives 59 (4): 873–891.

Eisinger, P.K. 1973. The conditions of protest behavior in American cities. American Political Science Review 67 (01): 11–28.

Elsbach, K.D., and R.I. Sutton. 1992. Acquiring organizational legitimacy through illegitimate actions: A marriage of institutional and impression management theories. The Academy of Management Journal 35 (4): 699–738.

Eurostat. 2016. Eurostat Statistics. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Fominaya, C.F., and L. Cox (eds.). 2013. Understanding European movements: New social movements, global justice struggles, anti-austerity protest. Abingdon: Routledge.

Fuchs, D., and D. Rucht. 1992. Support for new social movements in five Western European countries. A new Europe? Social Change and Political Transformation, 86–111. Londres: UCL Press.

Gamson, W.A. 2004. Bystanders, public opinion and the media. In The blackwell companion to social movements, ed. D.A. Snow, S.A. Soule, and H. Kriesi, 242–261. Oxford: Blackwell.

Gamson, W.A., and G. Wolfsfeld. 1993. Movements and media as interacting systems. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 528: 114–125.

Genovese, F., G. Schneider, and P. Wassmann. 2016. The Eurotower strikes back: Crises, adjustments, and Europe’s austerity protests. Comparative Political Studies 49 (7): 939–967.

Giugni, M., and M. Grasso (eds.). 2015. Austerity and protest: Popular contention in times of economic crisis. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Gurr, T. 1970. Why men Rebel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hall, R.L., M. Rodeghier, and B. Useem. 1986. Effects of education on attitude to protest. American Sociological Review 1: 564–573.

Hofer, M. and M. Mexi. 2014. Empirical assessment of the crisis: a cross-national and longitudinal overview. In: LIVEWHAT WP1 Report, Working paper on definition and identification of crisis. Retrieved from http://www.livewhat.unige.ch/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/LIVEWHAT_D1.2.pdf. Accessed 29 Feb 2016.

Jeffries, V., R.H. Turner, and R.T. Morris. 1971. The public perception of the watts riot as social protest. American Sociological Review 36: 443–451.

Kern, A., S. Marien, and M. Hooghe. 2015. Economic crisis and levels of political participation in Europe (2002–2010): The role of resources and grievances. West European Politics 38 (3): 465–490.

Kousis, M. 2013. The transnational dimension of the greek protest campaign against troika memoranda and austerity policies 2010–2012. In Spreading protest: Social movements in times of crisis, ed. D. Della Porta, and A. Mattoni, 137–170. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Kriesi, H. 2015. Political mobilization in times of crises: The relationship between economic and political crises. In Austerity and protest: Popular contention in times of economic crisis, ed. M. Giugni, and M. Grasso, 19–33. London: Routledge.

Olsen, M. 1968. Perceived legitimacy of social protest actions. Social Problems 15 (3): 297–310.

Ortiz, I., S. L. Burke, M. Berrada, and H. Cortés. 2013. World protests 2006–2013. Initiative for policy dialogue and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung New York Working Paper.

Osborne, D., and C.G. Sibley. 2013. Through rose-colored glasses: System-justifying beliefs dampen the effects of relative deprivation on well-being and political mobilization. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 39 (8): 991–1004.

Osborne, D., C.G. Sibley, Y.J. Hout, and H. Smiht. 2015. Doubling-down on deprivation: Using latent profile analysis to evaluate an age-old assumption in relative deprivation theory. European Journal of Social Psychology 45 (4): 482–495.

Passarelli, F. and G. Tabellini. 2013. Emotions and political unrest. CESifo Working Paper Series 4165.

Peterson, A., M. Wahlström, and M. Wennerhag. 2015. European Anti-Austerity Protests-Beyond “old” and “new” social movements? Acta Sociologica 58 (4): 293–310.

Rüdig, W., and G. Karyotis. 2014. Who protests in Greece? Mass opposition to austerity. British Journal of Political Science 44 (3): 487–513.

Schraad-Tischler, D. 2015. Social Justice in the EU - Index Report 2015. Social Inclusion Monitor Europe. Bertelsmann Stiftung. Brussels. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/social-justice-in-the-eu-index-report-2015/.

Smith, J., J.D. McCarthy, C. McPhail, and B. Augustyn. 2001. From protest to agenda building: Description bias in media coverage of protest events in Washington, DC. Social Forces 79 (4): 1397–1423.

Sotirakopoulos, N., and C. Rootes. 2013. Occupy london in international and local context. In Spreading protest: Social movements in times of crisis, ed. D. Della Porta, and A. Mattoni, 171–192. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Turner, R.H. 1969. The public perception of protest. American Sociological Review 34 (6): 815–831.

Van Stekelenburg, J., B. Klandermans, and W.W. Van Dijk. 2011. Combining motivations and emotion: The motivational dynamics of protest participation. Revista de Psicología Social 26 (1): 91–104.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Discarding protests? Relating crisis experience to approval of protests among activists and bystanders

Appendix: Discarding protests? Relating crisis experience to approval of protests among activists and bystanders

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cristancho, C., Uba, K. & Zamponi, L. Discarding protests? Relating crisis experience to approval of protests among activists and bystanders. Acta Polit 54, 430–457 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-017-0061-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-017-0061-1