Abstract

We systematically review the literature on customer satisfaction, partitioning the literature into three generations of thought and focus, with the most recent, third generation, heavily emphasizing international business phenomena. Following a brief, stage-setting review of the first two generations – which address, respectively, the psychological underpinnings of the satisfaction concept, its antecedents, and consequences (first-generation), and the relationship between customer satisfaction, its strategic firm drivers, and firm financial performance outcomes, as well as moderators and mediators of those drivers and outcomes (second-generation) – we primarily focus on the third-generation international studies that have emerged over approximately the last 20 years. These third-generation studies have predominantly investigated the customer satisfaction concept as it is applied cross- and multi-nationally in diverse international market contexts but, due in large part to the cross-disciplinary nature of this research, this literature is fragmented and disjointed. Following a review and synthesis of the third-generation satisfaction literature, connecting it to and differentiating it from the first two generations and integrating its main themes and most significant findings, we identify enduring gaps and unanswered research questions. Of particular note is the dearth of studies examining cross- and multinational moderators of both the strategic firm drivers of satisfaction and the satisfaction–firm performance relationship. We conclude with avenues for future research that can generate important IB-related customer satisfaction knowledge with the potential to provide enormous value to international researchers and managers.

Résumé

Nous passons systématiquement en revue la littérature de la satisfaction du client en la divisant en trois générations de pensée et de thème, avec la troisième et la plus récente génération mettant fortement l'accent sur les phénomènes des affaires internationales. Après un bref examen des deux premières générations - qui abordent respectivement les fondements psychologiques du concept de la satisfaction, de ses antécédents et de ses conséquences (première génération), et la relation entre la satisfaction du client, ses moteurs stratégiques au niveau de l’entreprise et les conséquences en matière de performance financière de l'entreprise, ainsi que les modérateurs et les médiateurs de ces moteurs et conséquences (deuxième génération) - nous nous focalisons essentiellement sur les travaux internationaux de troisième génération qui ont émergé au cours des 20 dernières années environ. Ces travaux de troisième génération ont principalement étudié le concept de la satisfaction du client tel qu'il est appliqué à l'échelle transnationale et multinationale dans divers contextes de marché international, mais, en raison notamment de la nature interdisciplinaire de cette recherche, cette littérature est fragmentée et disjointe. Après avoir passé en revue et synthétisé la littérature de la satisfaction de troisième génération, nous identifions des lacunes persistantes et des questions de recherche sans réponse en reliant cette littérature de troisième génération aux deux premières générations, en la différenciant de ces dernières, et en intégrant ses principaux thèmes et ses résultats les plus significatifs. Il convient de souligner le manque de recherche portée sur les modérateurs transnationaux et multinationaux des moteurs stratégiques de satisfaction au niveau de l’entreprise et de la relation satisfaction-performance. Nous concluons par des pistes de recherche future qui peuvent générer d'importantes connaissances sur la satisfaction du client liées aux affaires internationales, susceptibles d'apporter une valeur considérable aux chercheurs et aux managers internationaux.

Resumen

Hicimos una revisión sistemática de la literatura sobre satisfacción del consumidor, separando la literatura en tres generaciones de pensamiento y enfoque, con la más reciente, la tercera generación, la que más fuertemente enfatizando el fenómeno de negocios internacionales. Tras un breve repaso de las dos primeras generaciones, que abordan, respectivamente, los fundamentos psicológicos del concepto de satisfacción, sus antecedentes y consecuencias (primera generación), y la relación entre la satisfacción del consumidos, sus impulsores estratégicos y los resultados financieros de la empresa, así como los moderadores y mediadores de dichos impulsores y resultados (segunda generación), nos centramos principalmente en los estudios internacionales de tercera generación que han surgido en los últimos 20 años aproximadamente. Estos estudios de tercera generación han investigado predominantemente el concepto de satisfacción del consumidor tal y como se aplica a nivel transnacional en diversos contextos de mercado internacionales pero, debido en gran parte a la naturaleza interdisciplinar de esta investigación, esta literatura está fragmentada y desarticulada. Luego de una revisión y síntesis de la literatura sobre la satisfacción de tercera generación, conectándola y diferenciándola de las dos primeras generaciones e integrando sus principales temas y conclusiones más significativas, identificamos las brechas persistentes y las preguntas de investigación sin respuesta. Se destaca particularmente la escasez de estudios que examinen los moderadores multinacionales de los motores estratégicos de la satisfacción de la empresa y la relación entre la satisfacción y el desempeño de la empresa. Concluimos con pistas para futuras investigaciones que pueden generar importantes conocimientos sobre la satisfacción del consumidor relacionada con los negocios internacionales, con el potencial de proporcionar un enorme valor a los investigadores y gerentes internacionales.

Resumo

Revisamos sistematicamente a literatura a respeito de satisfação do cliente, dividindo a literatura em três gerações de pensamento e foco, com a mais recente, terceira geração, enfatizando fortemente fenômenos de negócios internacionais. Seguindo uma breve revisão de cenário das duas primeiras gerações – que abordam, respectivamente, os fundamentos psicológicos do conceito de satisfação, seus antecedentes e consequências (primeira geração), e a relação entre a satisfação do cliente, seus impulsionadores estratégicos da empresa, e resultados de desempenho financeiro da firma, bem como moderadores e mediadores desses impulsionadores e resultados (segunda geração) – focamos principalmente nos estudos internacionais de terceira geração que surgiram nos últimos 20 anos. Esses estudos da terceira geração investigaram predominantemente o conceito de satisfação do cliente, uma vez que é aplicado de forma transversal e multinacional em diversos contextos do mercado internacional, mas, devido em grande parte à natureza interdisciplinar desta pesquisa, essa literatura é fragmentada e desarticulada. Seguindo uma revisão e síntese da literatura de satisfação da terceira geração, conectando-a e diferenciando-a das duas primeiras gerações e integrando seus temas principais e descobertas mais significativas, identificamos lacunas duradouras e questões de pesquisa não respondidas. De particular interesse é a escassez de estudos examinando moderadores transversais e multinacionais tanto dos impulsionadores estratégicos da firma de satisfação quanto da relação satisfação-desempenho da firma. Concluímos com vias para pesquisas futuras que podem gerar importante conhecimento de satisfação do cliente relacionados a IB com o potencial de fornecer admirável valor para pesquisadores e gerentes internacionais.

摘要

我们系统地回顾了关于客户满意度文献, 将文献分为三代思想和重点, 最近的第三代重点强调国际商业现象。我们在对前两代进行了简短的阶段性的回顾之后, 主要关注了大约在过去 20 年中出现的第三代国际研究 – – 分别解决了满意度概念的心理基础、其前因与后果 (第一代) , 客户满意度与其战略公司驱动力和公司财务业绩结果之间的关系, 以及这些驱动力和结果 (第二代) 的调节者和中介者。这些第三代研究主要调查了客户满意度概念, 因它在不同国际市场环境中的跨国和多国的应用, 但在很大程度上由于这项研究的跨学科性质, 文献是分散和脱节的。在对第三代满意度文献进行回顾和综合后, 将其与前两代文献联系起来并加以区分, 并整合其主要的主题和最重要的发现, 我们确定了一直存在的空白和尚未回答的研究问题。特别值得注意的是, 对满意度和满意度-公司绩效关系的跨国和多国调节因素的战略公司驱动力缺乏研究。我们在结尾中指出了未来研究的途径, 这些途径可产生重要的与 国际商业(IB) 相关的客户满意度知识, 有潜力为国际研究者和管理者提供巨大的价值。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Customer satisfaction has been and remains one of the most widely adopted and analyzed business metrics – and quite possibly, the single most widely adopted such metric – within the international business ecosystem (Mintz, Currim, Steenkamp, & de Jong, 2019; Hult, Gonzalez-Perez, & Lagerström, 2020). Countless large, mid-size, and small firms spanning developed, emerging, and frontier markets measure the satisfaction of their customers as a key performance indicator (KPI) reflective of the strength of their customer relationships and business performance (Mintz et al., 2019). A substantial number of multinational enterprises (MNEs) and the market research suppliers serving them1 also measure the satisfaction of diverse customer portfolios across a variety of national markets, often as a means for benchmarking and comparing relative performance across these (diverse) markets (Morgeson, Sharma, & Hult, 2015; Kumar, Rajan, Gupta, & Pozza, 2019). Academic customer satisfaction research is now nearly 60 years old (e.g., Cardozo, 1965; Bell, 1967), and while alternative business KPIs have emerged and vanished – management “fads” that built excitement and garnered the attention of executives only to fade away and fall out of popularity – customer satisfaction has endured over this lengthy period (Collins, 2013).

As customer satisfaction research proliferated over the last 60 years, the literature has evolved through three discernible and distinct (but overlapping with respect to time) streams, or “generations” as we label them in this research. Briefly, the first-generation studies focused on customer satisfaction as a post-consumption state-of-mind, believed to be influential over future consumer behaviors advantageous to firms. Most of these consumer psychology and consumer behavior studies sought to identify what customer satisfaction is and the cognitive processes through which the phenomenon emerges, as well as its primary psychological antecedents and consequences (e.g., Cardozo, 1965; Oliver, 1977, 1980; Churchill & Surprenant, 1982). The second-generation satisfaction studies are strategy-focused, and seek to validate many of the primary theses of the first-generation research regarding the (presumed) positive business outcomes driven by satisfaction. This objective was largely pursued through an examination of the link between customer satisfaction and both its strategic drivers and objective, external measures of firm financial performance, along with the moderators and mediators of these relationships (e.g., Rust & Zahorik, 1993; Anderson, Fornell, & Lehmann, 1994; Anderson, Fornell, & Rust, 1997). Through these investigations, the ability of firms to drive customer satisfaction and for (aggregate) firm-level satisfaction to positively impact a firm’s financial performance (across a broad range of business and accounting metrics) cemented the importance of the concept for managers and researchers alike. Overwhelmingly, first- and second-generation customer satisfaction research focused on single-market contexts, largely ignoring the role of international business-related factors in the customer satisfaction ecosystem. This fact is reflected in the absence of discussion of any international business-related factors in the existing systematic reviews of either first-generation (Yi, 1990) or second-generation (Otto, Szymanski, & Varadarajan, 2020) satisfaction research.

More recently, a third generation of customer satisfaction research has emerged. These third-generation studies are multifaceted, often blending elements of the first two generations, and are broadly focused on the delineation of international business-related factors as drivers of customer satisfaction and/or as moderators and mediators of its relationships with its psychological and objective antecedents and outcomes. Notably, these third-generation studies evolved in parallel with the rapid growth in economic globalization around the turn of the new millennium. At the time, dramatic growth in firms’ internationalization efforts (e.g., Kirca, Hult, Roth, Cavusgil, Perryy, Akdeniz, Deligonul, Mena, Pollitte, Hoppner, & Miller, 2011), the globalization of supply chains and production (Hult, Closs, & Frayer, 2014), and increased interest in leveraging international joint ventures (e.g., Fang & Zou, 2009), among other important developments, were necessitating a broader emphasis on the measurement and monitoring of customer relationships across diverse, geographically and culturally disparate national markets (e.g., Cullen, Johnson, & Sakano, 1995; Lee & Beamish, 1995; Lin & Germain, 1998; Wulf, Odekerken-Schröder, & Iacobucci, 2001; Lee, Sirgy, Brown, & Bird, 2004). As such, these third-generation studies focused on applying the satisfaction concept in this increasingly internationalized business environment. Within this generation, the moderators and mediators of satisfaction examined derive from familiar themes within the international and cross-national business environment, and investigate cultural and/or national market variables hypothesized to affect customer satisfaction (at either the customer and/or the firm levels) and the relationship between satisfaction, its antecedents, and its outcomes. It is these third-generation studies that serve as the impetus for this review.

At this stage of its development, it is important to conduct a comprehensive review of these third-generation, international, multi-market satisfaction studies, the lessons learned, and the questions as yet unanswered to create synergy across knowledge generated between these generations for the benefit of the international business literature, and to effectively identify avenues for future research. Systematically reviewing this prominent collection of third-generation, internationally focused customer satisfaction studies is the primary objective of our review. Adopting a multidisciplinary approach, our review of this literature is based on an analysis of 140 articles from 30 leading journals spanning a variety of academic disciplines (e.g., international business, marketing, management) published predominantly since the year 2000 (we also provide a brief review of the first- and second-generation studies as a foundation for our third-generation review). Through this review, our study makes several contributions to the literature at the intersection of customer satisfaction and international business.

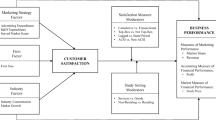

First, this study represents the first systematic review of the third-generation, international and cross-national customer satisfaction-focused literature, providing a unique opportunity to synthesize the state of and to set directions for this research, and thus providing value to those conducting research on customer satisfaction around the world. Through this exercise, we not only provide insights regarding this generation of research but also aim to stimulate further research therein. As noted above, while systematic reviews of both first- and second-generation customer satisfaction research have been provided (e.g., Yi, 1990; Otto et al., 2020), no similar review of these internationally oriented, third-generation studies has yet been offered, a substantial gap in the existing literature providing initial motivation for this study. Second, and relatedly, through this review we categorize and sub-segment this third-generation satisfaction literature into a useful structure for both researchers and managers addressing and confronting unique challenges regarding customer satisfaction measurement in a multi-market, multinational environment. This categorization is summarized in an inductively developed framework (see Figure 1, discussed in greater detail later in the manuscript) which provides insights into the international B2C and B2B relationships commonly examined in this stream of literature.

The knowledge structure and gaps in international customer satisfaction research. $ Not represented under the dotted box. However, all exporter–importer relationships are inherently international. # A few of the reviewed third-generation studies examine a narrow set of strategic antecedents such as CSR (Ruiz, Garcia, & Revila, 2016), channel strategy (Rambocas et al., 2015), and segmentation strategy (Diamantopoulos et al., 2014). However, largely the examination of strategic drivers of satisfaction has been overlooked. * Two of the reviewed third-generation studies (Berger et al., 2015; Webster & White, 2010) examine business performance using survey-based self-reported measures (by managers) but no study examines the objective firm performance outcomes.

Lastly, and most critically, this comprehensive, multidisciplinary review is motivated by two interrelated and crucial weaknesses we observe in the existing third-generation, international customer satisfaction literature: the fragmented and disjointed nature of this research, and the resulting critical gaps in the literature emerging from this fragmented condition. Marketing scholars and those in many other business sub-disciplines have researched customer satisfaction for decades. The last two decades have seen scholars adopt an international perspective with respect to examining satisfaction, as we illustrate below. But as a result of progressing largely independently in separate academic disciplines, this third-generation international customer satisfaction research is scattered and disjointed, precisely because arising across diverse disciplines with variable research priorities, methodological traditions, and so forth. Moreover, and due largely to this fragmented nature, the extant third-generation literature has developed a variety of “blind spots” and failed to ask or answer an array of consequential questions. Importantly, these omissions include a failure to investigate the potentially differential nature of both the strategic firm drivers and outcomes of satisfaction (i.e., the satisfaction–financial performance linkage) as these are moderated by a variety of factors across diverse markets, leaving open the possibility that these relationships differ (in form, magnitude, or both) in ways significant to both researchers and international managers. Synthesizing and providing structure to this literature, highlighting its most important findings and conclusions, and providing an outline of the most important but still-unanswered research questions therein serves as the primary motivation for this review.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Following a brief, stage-setting review of the core studies from the first two generations of customer satisfaction research, we introduce the third-generation research. We next outline the scientometric methods employed towards a systematic identification and review of this cross-national and international, third-generation customer satisfaction research. Via a descriptive analysis, we proceed by outlining the general focus of the field, the research topics examined, the development of this literature over time and across journals and disciplines, and the most common data and analytical methods employed. In specific detail, we then thematically outline the research questions and the key findings of this literature, grouping studies into two broad categories (international B2C and international B2B relationships), as well as sub-categorizing the literature within each broad group and identifying significant enduring questions. Finally, we offer detailed commentary on the most crucial gaps in the literature and most important research questions and directions for advancing the third-generation satisfaction literature, with a particular emphasis on the need to more thoroughly integrate the second-generation focus on the strategic firm drivers and outcomes of satisfaction in the satisfaction–financial performance linkage into the international and cross-national third-generation literature (Buckley, Doh, & Benischke, 2017).

FIRST- AND SECOND-GENERATION CUSTOMER SATISFACTION RESEARCH

In this section, we provide a brief, stage-setting review of the first two generations – which address, respectively, the psychological underpinnings of the satisfaction concept, its antecedents, and consequences (first-generation), and the relationship between customer satisfaction, its strategic firm drivers, and firm financial performance outcomes, as well as moderators and mediators of those drivers and outcomes (second-generation). Table 1 outlines and compares core features of the three generations of customer satisfaction research, including their predominant analytical focus, level of analysis, and theoretical and methodological approaches. Additionally, Tables A1 and A2 (included within the Web Appendix) provide a representative selection of first- and second-generation customer satisfaction research, respectively.

First-Generation Satisfaction Research

Customer satisfaction research first emerged in the mid-1960s, borrowing a concept that had been examined for decades in studies of job and life satisfaction (e.g., Brayfield & Rothe, 1951; Neugarten, Havighurs, & Tobin, 1961) and applying it to the realm of consumer attitudes. Although predominantly a consumer psychology and marketing research concern (e.g., consumer behavior, firm-level marketing asset), the first-generation satisfaction literature emerged from across a range of scholarly disciplines, both within and outside business. In a widely adopted definition, Richard L. Oliver defines customer satisfaction as “…the consumer’s fulfillment response … It is a judgment that a product/service feature, or the product/service itself, provided (or is providing) a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfillment, including levels of under- or overfulfillment” (Oliver, 2010, p. 8). Thus, satisfaction for the individual consumer represents both a positive affective response and a cognitive judgement regarding a product or service that arises during or following a consumption experience (e.g., Oliver, 1980, 1993).

Much of the first-generation satisfaction research was focused on identification of psychological correlates and cognitive mechanisms underlying and driving consumers’ satisfaction. Early on, and again borrowing from research in related disciplines (e.g., Spector, 1956), customer satisfaction was deemed to be intertwined with consumers’ pre-experience expectations regarding the product or service consumed. Satisfaction was defined as “pleasurable consumption fulfillment,” but this affective state both drove and was driven by consumer perceptions of “under- or overfulfillment” with the product/service experienced, with the latter revealed through a cognitive process of comparing an experience to prior expectations about the same (e.g., the expectancy–disconfirmation model) (Oliver, 1977, 1980). Much of the first-generation work aimed at refining, debating, and clarifying the nature of both expectations and expectancy confirmation and disconfirmation, while also introducing the concept of perceived performance (or quality perceptions) into the theoretical system (e.g., Olshavsky & Miller, 1972; Churchill & Surprenant, 1982; Tse & Wilton, 1988; Anderson & Sullivan, 1993; Spreng, MacKenzie, & Olshavsky, 1996).

Importantly, beyond investigations of its psychological antecedents, first-generation studies posited that customer satisfaction likewise drove consumer behavioral intentions favorable to the firm (Yi, 1990). From the very earliest research, it was argued that customer satisfaction “presumably leads to repeat purchases, acceptance of other products in the same product line, and favorable word-of-mouth publicity,” outcomes of value to most firms (Cardozo, 1965, p. 244; Oliver, 1980). Validating the existence of these consequences of satisfaction, at least as attitudinal descriptors of satisfied consumers’ behavioral intentions, and modeling their functional form played an essential role in the first-generation satisfaction literature (Anderson, 1998). Given the importance of customer loyalty, up- and cross-selling opportunities, positive word-of-mouth, and related outcomes for firms, measurement of aggregate customer satisfaction among a firm’s customers (or among particular segments of those customers) was quickly recognized as a fundamental business imperative (McNeal & Lamb, 1979).

Second-Generation Satisfaction Research

In the early 1990s, a significant second-generation shift in focus within customer satisfaction studies emerged. Researchers turned their attention from the nature and correlates of the consumer-psychological state and began to examine its objective drivers and its influence over business outcomes. At its core, this marketing strategy-focused stream of the literature sought to confirm customer satisfaction’s positive relationship with not just consumers’ attitudes, positive affect, and behavioral intentions, but to evidence its influence over observed consumer behaviors (e.g., Bolton, 1998). Studies in this stream also focused on examining a variety of firms’ strategies, both marketing-related and others, for their effects on customer satisfaction. Given the difficulties inherent in tracking the connections between (always-evolving) consumer attitudes and consumers’ observed future behaviors longitudinally at an individual customer level (for even a single firm, let alone a cross section of firms in diverse economic sectors and industries), most research pursued these objectives by investigating the relationships at the firm level, i.e., firm-level customer satisfaction, its firm-level strategic drivers, and firm-level financial performance outcomes.

Concerning firm-level strategic drivers, the second-generation studies have examined a variety of strategies for their implications for customer satisfaction in both B2C and B2B relationships and across a variety of industry contexts, including: marketing strategies, such as advertising (Song, Jang, & Cai, 2016), and R&D and innovation (Dotzel, Venkatesh, & Berry, 2013; Rubera & Kirca, 2017); financial strategies, such as financial leverage (Malshe & Agarwal, 2015); human resource strategies, like wage inequality (Bamberger, Homburg, & Wielgos, 2021a, b) and front-line autonomy (Marinova, Ye, & Singh, 2008); supply chain strategies, including distribution network redesign (Shang, Yildirim, Tadikamalla, Mittal, & Brown, 2009) and franchised channel governance (Kashyap & Murtha, 2017); and other business-level strategies, like mergers and acquisitions (Umashankar, Bahadir, & Bharadwaj, 2021), corporate political activity (Vadakkepatt, Arora, Martin, & Paharia, 2021), corporate social responsibility (Luo & Bhattacharya, 2006), and business downsizing (Habel & Klarmann, 2015). As expected, given the substantial and fundamental differences among and across such strategies, there is much variability in the theoretical underpinnings for these effects on customer satisfaction and the empirically examined mechanisms driving them.

By contrast, the theoretical underpinning for the link between customer satisfaction and firms’ financial (and accounting) performance, sometimes referred to as the “satisfaction–profit chain” (Anderson & Mittal, 2000), is relatively straightforward: satisfying consumption experiences → positive consumer attitudes (e.g., attitudinal loyalty, intention to recommend) → pro-firm future consumer behaviors (e.g., behavioral loyalty, increased spending, positive word-of-mouth) → positive firm financial performance. Early research in the second-generation literature established the parameters and economic mechanisms of the satisfaction–profit chain through which customer satisfaction affects firms’ financial performance, at times counterintuitively and differentially across product categories and industries (e.g., Anderson et al., 1994; Fornell, 1992, 1995). It also provided evidence that satisfaction did indeed relate positively to marketing and accounting metrics (e.g., return on investment, profitability, productivity) (Anderson et al., 1997; Rust & Zahorik, 1993); Anderson & Mittal, 2000). Over the ensuing years, the second-generation literature has expanded substantially on these findings and positively connected firm-level customer satisfaction to a wide variety of objective measures of financial performance (Otto et al., 2020).

The overall findings from first- and second-generation research on customer satisfaction provide significant support for the customer satisfaction metric as one of critical importance to businesses. Importantly, customer satisfaction represents more than positive attitudes and intentions among a firm’s customers. It is driven by a variety of firm strategies and also influences and predicts the economic and financial performance of the firm. These findings help explain not only the enduring appearance of satisfaction research but also its continued broad-based adoption among firms, managers in general, and marketing research practitioners in particular (Mintz et al., 2019).

Following these two generations of customer satisfaction research, and about 35 years after the first studies on the topic appeared, another, more recent shift in focus occurred. As noted above, these internationally oriented third-generation satisfaction studies evolved in parallel with the dramatic growth in economic globalization around the turn of the new millennium, and as such they focus on multi-national, multi-market studies of customer satisfaction, and often examine moderators and mediators of satisfaction drawn from the IB literature. While a small number of studies investigating satisfaction in a cross-national, international, and/or multinational context had appeared in the 1980s and 1990s, this trickle became a flood around the year 2000 and thereafter. Driven by the reality of increasingly globalized markets and an explosion of firms’ multi-nationalization efforts, these third-generation studies have thus focused on extending and expanding customer satisfaction from a single-market measure (e.g., a single firm operating within a particular national market) of firm performance to a metric with relevance to MNEs (and related IB ventures) across international markets. It is this third-generation satisfaction research that will garner our attention in the remainder of this review. Next, we turn to a description of the scientometric methods used to identify relevant third-generation studies.

METHODOLOGY

Given the objective of this review article as outlined in the introduction, we adopt a multi-step methodology including two broad phases: (1) article search and selection and, (2) information retrieval and analysis. This approach is similar to those adopted by systematic reviews in both the international business (e.g., Tranfield, Denyer, & Smart, 2003) and marketing (e.g., Lamberton & Stephen, 2016; Whitler, Krause, & Lehmann, 2020) disciplines, and in line with suggestions for best practices in conducting literature reviews (Hunter & Schmidt, 1990, 2004; Littell, Corcoran, & Pillai, 2008; Palmatier, Houston, & Hulland, 2018).

Article Search and Selection

We follow established procedures and use a systematic approach to ensure comprehensive coverage of articles at the intersection of research on customer satisfaction and international business (Aguilera, Marano, & Haxhi, 2019). Specifically, we rely on four literature search strategies: (a) a keyword search in relevant academic journals through electronic databases; (b) a manual search for “articles in advance” and “online first” articles through the websites of the relevant journals; (c) a backward snowball search using the lists of references of the articles retrieved in steps (a) and (b), and a forward snowball search of the articles that cite the articles retrieved in steps (a) and (b) and those discovered in the backward snowball search; and d) contacting the leading authors that publish in this area for additional articles.

First, in step (a), to be as comprehensive as possible in our search for all potentially relevant studies, and given the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of research on customer satisfaction (e.g., Morgeson, Mithas, Keiningham, & Aksoy, 2011; Morgeson et al., 2015), our search covered all 50 of the journals included in the Financial Times’ “FT Research Rank.”2 The journals included in this list encompass the leading journals in the disciplines of international business, marketing, management, organizational behavior, economics, accounting, finance, operations and information systems, business ethics, and entrepreneurship, and are the primary outlets for leading research in their respective disciplines (e.g., Zhang, 2021).

Additionally, given that the third-generation studies on customer satisfaction lie mainly at the intersection of marketing and international business (which is our core focus), and several high-profile journals situated at this intersection are not included in the “FT Research Rank” list, we expanded the list of included journals. Specifically, we included six additional journals from the international business discipline – Global Strategy Journal, International Business Review, Journal of World Business, Management International Review, International Marketing Review, and Journal of International Management (Treviño, Mixon, Funk, & Inkpen, 2010) and five additional journals from the marketing discipline – International Journal of Research in Marketing, Journal of Retailing, Journal of Service Research, Journal of International Marketing, and European Journal of Marketing (Khamitov, Grégoire, & Suri, 2020; Dowling, Guhl, Klapper, Spann, Sitch, & Yegoryan, 2020). Lastly, since the journals included in the Financial Times’ ranking do not include specialized journals from the discipline of hospitality, travel, and tourism, and having discovered many potentially relevant international customer satisfaction studies from this broad “service-focused” area through initial searches on Google Scholar, we also include five journals that constitute the leading outlets in this discipline. The journals included are Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, International Journal of Hospitality Management, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, and Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management (Prayag, Hassibi, & Nunkoo, 2019).

With this list of 66 leading journals across a broad swatch of business disciplines, we undertook a systematic keyword search through multiple online databases using the term “satisfaction” in combination with 35 keywords that capture international dimensions, such as “international,” “global,” “cross-border,” and “cross-cultural” without specifying or delimiting a timeframe.3 This process resulted in 580 search records, which were independently screened by two of the co-authors for inclusion based on two key criteria. First, the article must examine customer satisfaction empirically. As such, conceptual articles, review articles,4 abstracts, book reviews, case studies, corporate profiles, symposium proceedings, editorials, and interviews were not included in our review. Second, the article must empirically incorporate an international dimension, such as examination of cross-country relationships (e.g., importer–exporter relationship) or of national culture-related constructs (e.g., national cultural values), and/or alternatively analyze samples from more than one country (e.g., multi-group comparison of relationships using segments differentiated by country, culture, or region). As such, articles that simply use a sample from more than one country but do not examine cross-national differences in relationships were excluded. The co-authors agreed on their assessment for more than 97% of the original 580 search records and the differences were resolved through discussion, leading to inclusion of 100 articles from this first step.

Next, in step (b), we searched for online-first, accepted but yet to be printed articles, and “articles in advance” in each of the 66 selected journals to ensure inclusion of any recent work on the topic. We identified four additional articles in this step that satisfied our inclusion criteria discussed above in step (a). Overall, steps (a) and (b) therefore resulted in a total of 104 articles that satisfied our inclusion criteria and are included in our review. In step (c), we then conducted our backward snowball search using the list of references of these 104 articles and this resulted in the identification of 15 additional relevant articles. We then conducted a forward snowball search in the articles that cite the 119 articles identified to this point (Duran, Kammerlader, Van Essen, & Zellweger, 2016), and through this step 21 additional articles were identified that satisfy our inclusion criteria. Within both the backward and the forward snowball searches, we included only articles published in journals with an impact factor of 4 or above (Journal Citation Reports Social Sciences Edition (Clarivate Analytics, 2020)) towards inclusion of only state-of-the-art third-generation customer satisfaction research. Finally, in step (d), we identified the top 25 authors (based on a Google Scholar citation count) specializing in either/or customer satisfaction, international marketing, international business, or marketing strategy. These authors were contacted via e-mail and requested to identify any relevant articles or manuscripts in the third-generation customer satisfaction research stream (as we have defined it) that were at or near completion (such as working papers), currently under review, or conditionally accepted/accepted and soon to be published articles. While several replies were received, no additional relevant articles were identified through this step. Overall, our review of the third-generation, internationally oriented customer satisfaction literature is therefore based on 140 articles from 30 journals published during the period 1980–2020.

Information Retrieval and Analysis

In line with prior research (e.g., Morgan, Whitler, Feng, & Chari, 2019) and recommended best practice procedures for review articles (e.g., Katsikeas, Morgan, Leonidou, & Hult, 2016), two of the co-authors independently retrieved information initially from ten articles and coded them using pre-determined protocols agreed upon by all the authors. The pre-determined protocols detailed the coding objectives and specifics on the nature of the information to be retrieved from each article. The initial coding was independently assessed by a researcher with substantial publishing experience in both the marketing and international business disciplines. After discussions and revisions to the information retrieval and coding protocols, the two initial co-authors independently coded each of the 140 articles, with an inter-rate agreement of about 94%.

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS OF THIRD-GENERATION CUSTOMER SATISFACTION RESEARCH

We begin our analysis of the retrieved 140 internationally oriented, third-generation customer satisfaction articles published in 30 leading business journals during the 1980–2020 period with a critical descriptive review of the general focus of the field, the research topics examined, development of this literature over time and across journals and disciplines, and the most common data and analytical methods employed. Initial, high-level insights regarding both the current state and the gaps, omissions and shortcomings of the current literature are also provided.

General Focus of the Field

Current state

A substantial majority of the international customer satisfaction studies (see Table 2, Panel A) included in this literature review focus on examining business-to-customer relationships (B2C) (N = 97, 69.8%), with about a quarter examining business-to-business relationships (B2B) (N = 35, 25.2%), and only a handful examining both (N = 7, 5.0%). Likewise, less than half of the articles undertake a cross-cultural analysis (N = 56, 40.0%), examining culture-related factors in the context of customer satisfaction or its antecedents and outcomes. The remaining adopt a cross-national perspective (N = 84, 60.0%) and examine differences in levels of customer satisfaction across countries, its relationship with its antecedents and outcomes, or the effects of country-level factors (such as economic structure, socioeconomic conditions, and/or the political environment) on satisfaction using samples from two or more countries (see Table 2, Panel B). In terms of study conceptualization, about half of the articles adopt a strategic perspective (N = 66, 47.1%), examining customer satisfaction from the firm decision-making perspective, while the other half adopt a behavioral perspective (74, 52.9%) and examine customers’ attitudes and the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral aspects of customer satisfaction (see Table 2, Panel C).

Suggested direction

In the aggregate, while the current third-generation customer satisfaction research has generated substantial insights regarding both B2C and B2B relationships, it offers little understanding of the customer satisfaction formation process and its implications in the increasingly dominant – and very often cross-national and cross-cultural – customer-to-customer (C2C) or peer-to-peer relationships essential to digital marketplaces (e.g., eBay, Craigslist, Amazon, Etsy, and ASOS). These relationships differ substantially from either traditional B2C or B2B relationships, due to characteristics such as lack of quality control, dynamic pricing mechanisms (e.g., demand planning, auction-based pricing), and increased opportunities for seller misconduct (Costello & Reczek, 2020), and the lack of research indicates a promising direction for scholars in this area.

Research Topics

Current state

Concerning the international customer satisfaction literature focused on B2C relationships, our analysis reveals that the current research has predominantly focused on certain topics (see Table 2, Panel D), such as services marketing (N = 77, 55.0%), retailing (N = 22, 15.7%), and country-of-origin (N = 10, 7.1%). Other topics, such as market segmentation (N = 4, 2.9%) and product/service positioning (N = 2, 1.4%), have received some but significantly less attention.5 Concerning B2B relationships, the dominant topics include import–export marketing or buyer–seller relationships in international markets (N = 32, 22.9%), and distribution channels or channel governance (N = 10, 7.1%).

Suggested direction

Overall, while the current third-generation satisfaction research has largely focused on the examination of topics carried over from first-generation research into the international context, it has yet to examine customer satisfaction in emerging contexts that increasingly occupy ongoing second-generation research, such as the sharing economy (Eckhardt, Houston, Jiang, Lamberton, Rindfleisch, & Zervas, 2019), digitization (Banalieva & Dhanaraj, 2019; De Luca, Herhausen, Troilo, & Rossi, 2021), influencer marketing (Hughes, Swaminathan, & Brooks, 2019), the customer-technology interface (Jean, Sinkovics, & Cavusgil, 2010; Crolic, Thomaz, Hadi, & Stephen, 2021; Tan, Chandukala, & Reddy, 2021), healthcare marketing (Robitaille, Mazar, Tsai, Haviv, & Hardy, 2021), and financial technology and inclusion (Kumar, Nim, & Agarwal, 2021) – all innovations that are strongly shaping firm strategies and customer experiences today and in the future, and doing so (potentially) differently across countries and cultures. Additionally, this stream of literature has largely neglected the examination of firm-level strategic drivers of customer satisfaction and its objective firm performance implications in the international context. Here, we note these as gaps and omissions in the current third-generation customer satisfaction research and provide related directions later in the “Future Research” section of the manuscript.

Trends by Disciplines and Journals over Time

Current state

Table 3 provides a breakdown of the 140 articles included in this review across journals (Panel A) and academic disciplines (Panel B) over time. By academic discipline, marketing journals are the primary outlets of the third-generation satisfaction research, with mainstream marketing journals publishing the largest share (N = 54, 38.6%), followed by more specialized international marketing journals (N = 39, 27.9%). The core international business journals account for a share of only 7.9% (N = 11) of the articles, a sizeable gap relative to the other two (and a weakness we aim to address, in part, through this review). The information systems journals, which are the dominant outlet for research on the customer-technology interface, account for the lowest share of the articles (N = 3, 2.1%). About 90% of the literature in this third-generation stream has appeared since 2001, and more than 97% since 1997.

Suggested direction. While our search for relevant literature included leading journals across other disciplines such as finance, accounting, economics, and entrepreneurship, we identified no relevant articles in these disciplines concerning international customer satisfaction research. We deem this to be a significant gap in the literature and a promising direction for scholars in these areas, as these disciplines cover vital aspects of business and otherwise do investigate research questions concerning customer experiences (e.g., Cheng, Qian, & Reeb, 2020; Truong, Nguyen, & Huynh, 2021). As such, the absence of relevant research in these disciplines provides a significant opportunity for future scholarly contributions.

Data and Methods

Finally, in addition to understanding the nature of research topics examined and omitted, it is also helpful to understand the sources of data (including geographic focus) and methods of analysis, as this information can often provide a useful perspective from which to view the findings from this research.

Current state and suggested direction (data types)

The majority of the articles examined in our review use customer or key-informant surveys (N = 98, 70.0%), while a smaller proportion of the articles employ experiments (N = 30, 21.4%) (see Table 4, Panel A). Other non-experimental sources of data include archival data (N = 12, 8.6%), meta-analysis (N = 6, 4.3%), and qualitative data (N = 9, 6.4%). Notably, of the articles that do not use experiments, only 2 (1.8%) address endogeneity issues resulting from factors such as endogenous selection and unobserved heterogeneity (see Table 4, Panel C). This reflects a shortcoming of the current research in this domain because, unless additional steps are taken to test for and address potential endogeneity issues, survey-based data are less appropriate for testing hypotheses concerning causal relationships. Comparatively, the articles in the second-generation customer satisfaction research considered above often use approaches such as instrumental variables, panel data estimation (e.g., fixed-effects, first-differencing), and regression discontinuity design to address endogeneity-related issues (Otto et al., 2020). For future research in third-generation customer satisfaction literature, there is a need for scholars to adopt similar approaches towards a more robust identification of causal relationships.

Current state and suggested direction (geographic focus)

Concerning the geographic focus of the data (see Table 4, Panel D), a majority of the articles have examined samples drawn from Asia (N = 71, 53.0%), North America (N = 57, 42.5%), and Europe (N = 48, 35.8%). Significantly fewer articles have focused on Australia (N = 15, 11.2%), and even fewer on the countries of Africa (N = 11, 8.2%) and South America (N = 4, 3.0%). A relatively small number of studies (See Table 4, Panel E) have examined Western versus Asian (N = 15, 11.2%), international versus domestic (N = 7, 5.2%), and developed vs. emerging market (N = 2, 1.5%) comparisons of customer satisfaction or its relationships with its antecedents and outcomes. Critically, a bias towards certain geographic regions and the neglect of many others is visible in this research, and we draw on this to provide recommendations in the “Future Research” section later in the manuscript.

Current state and suggested direction (empirical methods of analysis)

In terms of empirical methods of analysis (see Table 4, Panel B), structural equation modeling (SEM) (N = 79, 56.4%) has dominated, followed by ordinary least squares (OLS) regression (N = 38, 27.1%) and comparison of means (N = 28, 20.0%). Hierarchical linear modeling (N = 11, 7.9%) is another somewhat frequently deployed method, and an understandable one given that these studies often analyzes samples (of customers and/or firms) nested within higher-level country, region, and/or culture-based groups. Other methods include factor analysis (N = 10, 7.1%) and text analysis (N = 9, 6.4%). A relatively small number of the studies use multiple methods (N = 14, 10%), which, when combined with the fact that only 10.7% (N = 15; see Table 4, Panel A) of the included articles analyze multiple sources of data, suggests another shortcoming of this stream of research, as the use of multiple methods and sources of data is increasingly common and recommended towards the provision of more robust conclusions.

Table A3 (included in the Web Appendix) provides the full list of the 140 articles reviewed here, including a variety of important details about each that were used to generate the descriptive analysis discussed above. The findings from these articles summarized in Table A3 also serve as the guide for our systematic integration of the international customer satisfaction literature in the third-generation studies, which we present in the next section. Table A3 is of value in and of itself for both scholars who focus on any of the niche areas in this third-generation research as well as those new to this sphere of research.

FINDINGS FROM THIRD-GENERATION CUSTOMER SATISFACTION RESEARCH

In what follows, we segment our detailed review of the third-generation customer satisfaction studies into two broad categories – International Business-to-Consumer (B2C) and International Business-to-Business (B2B) customer satisfaction studies – based on an analysis of the focus and content of these studies (see Table 2 and Table A3 (Web Appendix)). As noted previously, the third-generation satisfaction literature has tended to favor the former (N = 97, 69.8%) over the latter (N = 35, 25.2%) type of study (with N = 7, 5.0% including both B2C and B2B dimensions), and this is reflected in our review. We further divide these two broad groups (B2C and B2B) into relevant sub-categories within each, based on an analysis of the retrieved literature and what are deemed to be the primary research questions, methods, purposes, and findings from within these studies.

Figure 1 provides an inductively developed organizing framework for our review, highlighting the key constructs and relationships concerning antecedents, levels, and outcomes of customer satisfaction examined in the third-generation literature, as well as opportunities for future research. Panel (1) delineates the knowledge structure of the extant research for international B2C satisfaction research. As reflected here, the research has examined variation in levels of customer satisfaction from a variety of perspectives, and particularly across cultures and across national markets. It has also examined cross-national variance in the traditional antecedents (e.g., service quality and service failure) and outcomes (e.g., loyalty and complaint behavior) of customer satisfaction, with a noticeable focus on the moderating role of variables such as national culture or market development in these relationships. Viewed in totality, many parallels between the international B2C, third-generation customer satisfaction literature and the foundational, first-generation satisfaction studies are apparent. Also visible in Figure 1 is that these third-generation studies have largely overlooked the examination of cross-cultural and cross-national variance in the effects of firm strategies on customer satisfaction and of customer satisfaction on objective (i.e., financial) firm performance outcomes.

Panel (2) illustrates the knowledge structure of the extant international B2B customer satisfaction research. The dominant type of IB relationship examined in this research – i.e., importer–exporter relationships – is inherently international, and as such this category of satisfaction research has focused on this context and on the role of national culture either in directly affecting satisfaction, or on moderators of the relationships between customer satisfaction and its antecedents and outcomes. Uniquely, this research has often diverged substantially from traditional first-generation customer satisfaction studies, largely through the specification of antecedents and outcomes of satisfaction most applicable to the international B2B domain. It has also deviated from the international B2C third-generation literature by examining more particular cultural moderators most applicable to international business relationships. We begin by discussing the international B2C customer satisfaction studies. In the ensuing sections, we integrate findings from the reviewed articles to provide conclusions under “what we know and its implications”, and to identify specific research gaps and future research questions for each category (and sub-category) of articles under “what we don’t know”. Finally, we also make note of broader gaps and omissions in the literature and draw on these to delineate opportunities for research later in the manuscript in the “What We Should Know – Topics for Future Research” section.

International Business-to-Consumer Satisfaction Studies (Figure 1, Panel 1)

Globalization has created opportunities for established consumer goods and services firms to realize a potentially substantial proportion of their revenue growth via foreign revenues and entry into international markets (Silverblatt, 2019). The competitiveness and appeal of these brands to consumers in new markets, the cross-national and cross-cultural acceptability of these goods, and the factors that drive consumer preferences for them, however, can be difficult to gauge – even for very large, successful businesses (e.g., Shedd, 2019). This has resulted in the need for MNEs (and related entities) to measure and compare consumer perceptions of goods and services across national markets and cultures, and the customer satisfaction metric is regularly adopted to this end. In parallel, academic research has asked and answered a number of important questions regarding B2C customer satisfaction across such markets. In the sub-sections that follow, we categorize International B2C customer satisfaction research based on the dominant research question and/or primary findings, including: 1. cross-cultural and cross-national differences in levels of satisfaction, and 2. cross-national and cross-cultural moderators of the antecedents and outcomes of satisfaction. In the latter sub-section, given its prominent role in the third-generation B2C customer satisfaction literature in general, we segment our discussion into several separate discussions (on service failure and recovery, service customization and personalization, corporate reputation and brand image, e-commerce, developed vs. emerging markets, and foreign vs. domestic/country-of-origin effects).

Cross-cultural and cross-national differences in levels of satisfaction

What we know and its implications. The national culture concept occupies a place of prominence in the IB literature (e.g., Hofstede, 1984; Caprar, Devinney, Kirkman, & Caligiuri, 2015). Consequently, a substantial selection of international B2C customer satisfaction studies has focused on the role of national culture in driving variable consumer attitudes. Within this broad area, one core question involves the comparability of customer satisfaction ratings across countries and national markets marked by sometimes vast cultural differences. Since MNEs and related entities are now more likely to engage in a cross-national-market comparison of customer satisfaction scores (and related customer experience (CX) data) – an activity once limited (as in the first-generation satisfaction literature) to comparisons between ostensibly culturally invariant segments within a single firm’s customer portfolio – evidence of the comparability or equivalence of satisfaction ratings by consumers across national markets is critical (Hult, Ketchen, Griffith, Finnegan, Gonzalez-Padron, Harmancioglu, Huang, Talay, & Cavusgil, 2008). As such, a substantial cohort of studies has focused on examining cross-cultural and cross-national variance in the levels of customer satisfaction.

For example, in a large-scale cross-national study of multiple consumer industries across 19 diverse national markets, consumers in traditional societies were found to be more satisfied with the goods they consumed than those in secular-rational societies, while consumers in self-expressive societies were found to report higher satisfaction than those in societies favoring survival values (Morgeson et al., 2011). Furthermore, in a study spanning 25 national markets, the congruence between product content and consumers’ national culture (measured using the Hofstede cultural dimensions) was found to have a positive impact on consumers’ (online) satisfaction ratings of movies (Song, Moon, Chen, & Houston, 2018). Similarly, in somewhat narrower studies focusing on smaller sub-sets of national cultures, when compared to their North American counterparts (the U.S. and Canada), more conservative Japanese customers have been found to express lower perceived service quality and satisfaction under high-performance conditions, but to also exhibit a positive bias under low-performance conditions (Laroche, Ueltschy, Abe, Cleveland, & Yannopoulos, 2001). Comparable studies have likewise discovered a culturally driven variance in satisfaction ratings between Colombian (higher) and Spanish (lower) students (Duque & Lado, 2010), between Anglo Americans (lower) and Mexican Americans (higher) in both service quality and satisfaction ratings (Ueltschy & Krampf, 2001), and between Western (higher) and Asian (lower) customers (Poon & Low, 2005; Chan & Wang, 2008; Chan, Wan, & Sin, 2009), among other findings (Walsh & Bartikowski, 2013; Wang & Lalwani, 2019). Emerging from these findings is the conclusion that, not unexpectedly, levels of customer satisfaction vary across both cultures and country-based groupings of customers, providing a cautionary note for scholars and MNEs conducting cross-cultural and cross-national benchmarking of satisfaction data.

What we don’t know. However, the extant studies in this cluster of research, given their design and focus, leave several questions concerning cross-cultural and cross-national differences in the levels of customer satisfaction unanswered. First, most of the research that examines the cross-cultural differences in the levels of customer satisfaction neither specifically examine nor account for observed or unobserved country-level characteristics (e.g., institutional environment, socioeconomic conditions, economic growth, etc.). As such, in combination with the fact that very few studies use experimental methods or address endogeneity issues empirically, it cannot be ruled out that their findings concerning observed differences in the levels of customer satisfaction are driven by cultural factors and not by other country-level characteristics. Distinguishing the unique role of culture- and country-related factors, which often overlap, is thus an important future research objective in this context towards both theoretical development and substantive implications. Second, the findings from these articles could also be confounded because of the presence of measurement error, especially in light of the mixed findings concerning the lack of invariance of measures of customer satisfaction. For example, one article finds that, with some modifications, commonly used measures of customer satisfaction can be deployed across cultures for evaluation of services (Veloutsou, Gilbert, Moutinho, & Goode, 2005). In contrast, two studies that examine the invariance of five customer satisfaction measures used in prior research across countries such as the U.S., Canada (French-Canadians), Germany, and Japan find that only some of the measures are invariant across country-based groups of customers (Ueltschy, Laroche, Tamilia, & Yannopoulos, 2004; Ueltschy, Laroche, Eggert, & Bindl, 2007). These mixed findings indicate that third-generation studies are yet to reach a consensus regarding the invariance of customer satisfaction measures across countries and cultures, a gap that needs to be addressed.

Similarly, while some of the research also specifically examines the effect of cultural distance (or related constructs such as cultural congruency) on the levels of customer satisfaction, we observe contradictory findings regarding such effects. Most studies find a positive effect of lower perceived cultural distance (or higher cultural congruency) on customer satisfaction driven by factors such as increased interaction comfort with the service providers and reduced intergroup anxiety (e.g., Alden, He, & Chen., 2010; Johnson & Grier, 2013; Sharma, Wu, & Su, 2016; Ang, Liou, & Wei, 2018). On the other hand, a study by Tam, Sharma, & Kim (2014) finds a positive effect of higher perceived cultural distance on customer satisfaction, which is argued to result from the reduced expectations that customers have from service providers in situations of higher perceived cultural distance and from customers’ attribution of service failure to cultural factors (relative to the service provider itself). Future research should aim to reconcile these contradictory results, preferably in a single study that tests these competing explanations. Overall, these gaps and limitations provide several opportunities for scholars to contribute to this domain.

Cross-cultural and cross-national moderators of the antecedents and outcomes of satisfaction

What we know and its implications. Much of the first-generation customer satisfaction research focused on the linkages between customer satisfaction and its antecedents and outcomes. A select set of third-generation studies have also adopted this objective, with many examining the moderating role of national culture on the relationships between satisfaction and its antecedents and outcomes. Regarding the antecedents, an insightful study found that while service quality positively affects customer satisfaction in both the U.S. and the U.K., the national-cultural tendency of British consumers towards conservatism leads them to be more tolerant of poor service relative to U.S.-based customers (Voss, Roth, Rosenzweig, Blackmon, & Chase, 2004). Another study points to differences in the cross-national drivers of service quality and its relationship with customer satisfaction, explaining the differences via cultural variability in preferences between Western and Chinese customers (Lai, 2015). Similarly, Chan, Yim, and Lam, (2010) find that the cultural values of customers and employees moderate the effect of customer participation on value creation, which in turn drives customer satisfaction.

Regarding the outcomes, customer satisfaction among wireless telephone service consumers was found to be a driver of customer loyalty across several national markets, but the relationship was moderated by cultural characteristics and observed to be stronger in countries with stronger self-expression values when compared to countries with stronger survival values (Aksoy, Buoye, Aksoy, Larivière, & Keiningham, 2013). Similar research (investigating the same industry) also found cross-national variance in the satisfaction–loyalty linkage across developed (stronger) and emerging (weaker) markets, attributing this in part to national-cultural variability (Morgeson et al., 2015). A multi-industry investigation found that switching costs are a driver of propensity to stay (loyalty) across both Western (Australian) and Eastern (Thailand) cultures, but that customer satisfaction explains additional variance (over and above switching costs) for customers from both cultures (Patterson & Smith, 2003). Related research has likewise found national culture to drive differential links between satisfaction and post-consumption behavioral intentions (Olsen, Tudoran, Brunsno, & Verbeke, 2013; Smith & Reynolds, 2009), as well as other outcomes of satisfaction like post-purchase personal and nonpersonal risk evaluations (Keh & Sun, 2008).

Furthermore, a selection of the international B2C customer satisfaction studies test moderation by validating traditional models of customer satisfaction cross-nationally. Similar to much of the first-generation satisfaction research, these studies predominantly focus on examining the satisfaction formation process and its outcomes, but in this instance aim more narrowly at establishing model equivalence and validity across national markets. For example, one such study examines the generalizability of the expectancy–disconfirmation model of satisfaction across two countries (U.S. and Taiwan) for a consumer electronics product and finds that the direction and the pattern of relationships (and the resulting parameter estimates) to be similar (Spreng & Chiou, 2002). A similar study finds that the effects of service quality on customer satisfaction and of satisfaction on behavioral intention are consistent across two diverse national cultures (Ecuador and the U.S.) (Brady & Robertson, 2001). A comparable study develops a model for a consumer–retailer relationship where relationship tactics influence consumers' perceived relationship investment which in turn impacts perceived quality (a function of satisfaction, trust, and commitment), and ultimately behavioral intentions. The model is cross-validated across two industries (food and apparel) and three countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, and the U.S.) (Wulf et al., 2001). Another such study tests a comprehensive model wherein service quality, service value, and satisfaction jointly and directly impact behavioral intentions. The hypothesized model is tested against competing models based on alternate theories and is found to be superior and applicable across countries and service contexts (Brady, Knight, Cronin, Hult, & Keillor, 2005). Collectively, these satisfaction model-testing investigations, among a not-insubstantial collection of others (e.g., Gilbert, Veloutsou, Goode, & Moutinho, 2004; Ha, Janda, & Park, 2009; Tsai, 2011; Raub & Liao, 2012; Deng, Yeh, & Sung, 2013; Lin & Chen, 2013), generally point towards the cross-national applicability of the satisfaction concept.

In addition to these investigations of moderators of satisfaction in its relationship with its antecedents and outcomes and general satisfaction model testing, a number of studies have focused on special contexts and fundamental concepts in business and in marketing as they are (potentially) differently influential of or influenced by satisfaction across global markets. This includes studies of customer satisfaction in the international B2C context and service failure and recovery, service customization and personalization, digital business and e-commerce, country of origin (foreign vs. domestic) effects, level of development (developed vs. emerging markets), and specific firm-level intangible assets such corporate reputation and brand image. In the subsequent paragraphs, we discuss the insights from these smaller clusters of research.

Service failure and recovery

What we know and its implications. Over the past three decades, the voluminous literature on service failure and recovery has been intertwined with the customer satisfaction literature, and particularly the first-generation satisfaction literature focused on specifying antecedents and outcomes of satisfaction (e.g., Smith, Bolton, & Wagner, 1999). Service failures resulting in dissatisfaction, and firms’ efforts to manage and mitigate the loyalty-eroding outcomes of these failures, has driven the convergence in these two literature streams, and this research continues unabated today (e.g., Morgeson, Hult, Mithas, Keiningham, & Fornell, 2020). Similarly, a variety of third-generation satisfaction studies have examined the connections between service failure and recovery in international B2C contexts and consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction from a cross-cultural and cross-national perspective.

For example, a study spanning the UK, Spain, and Mexico found that while perceived justice in the context of service recovery is valued across cultures, customers from more feminine cultures require greater employee effort to positively influence post-recovery satisfaction, while customers from low uncertainty cultures are more willing to remain loyal to a firm after a service recovery (Yani-de-Soriano, Hanel, Vazquez-Carrasco, Cambra-Fierro, Wilson, & Centeno, 2019). Additionally, customers’ cultural orientations moderate the impact of perceived cultural distance and service outcomes (success vs. failure) on their satisfaction (Sharma et al., 2016) and of the cognitive (perceived justice) and affective antecedents of customer satisfaction (Schoefer, 2010). Other culture-related factors such as consumer ethnocentrism and intercultural competence also moderate the direct or indirect effects of service outcomes (success vs. failure) and perceived cultural distance on customer satisfaction (Sharma, Tam, & Kim, 2012; Sharma & Wu, 2015). Comparable research reinforces these findings of a connection between service failures, recovery efforts, national culture and related variables, and post-failure satisfaction (Matilla & Patterson, 2004; Patterson, Cowley, & Prasongsukarn, 2006; Schoefer, 2010; Weber, Hsu, & Sparks, 2014; Trianasari, Butcher, & Sparks, 2018). Collectively, these findings provide evidence for cross-cultural and cross-national variation in the customer satisfaction formation process in the context of service failures and recovery. For practitioners, these findings suggest the need to account for cultural orientations of customers and deployment of tailored (to culture and/or country) failure recovery strategies to maximize post-failure customer satisfaction.

What we don’t know. There remain, however, a variety of unexplored factors that may be expected to moderate the satisfaction–failure–recovery relationships cross-culturally and cross-nationally. This includes non-verbal cues of front-line employees (Lim, Lee, & Foo, 2017), social comparisons (Bonifield & Cole, 2008), race and discriminatory bias (Baker, Meyer, & Johnson, 2008), and customer revenge (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008; Gregoire, Laufer, & Tripp, 2010), and each of these factors could play different roles in the satisfaction formation process during service failure and recovery events across cultures and countries. Additionally, this research has omitted the examination of related but distinct phenomena such as brand transgressions, product-harm crisis, and product recalls (Khamitov et al., 2020; Mafael, Raithel, & Hock, 2021). Given the global prevalence of these phenomena and calls for integration and further articulation of research on such negative events (Fournier & Alvarez, 2013), scholars can contribute to this domain by expanding research on customer satisfaction in the context of these negative events across cultures and countries and across the stages of the customer journey (Khamitov, Gregoire, & Suri, 2020).

Service customization and personalization

What we know and its implications. In an international marketplace marked by consumers increasingly demanding of goods and services customized to meet their particular needs, how do firms achieve optimal service customization and personalization resulting in customer satisfaction? Several cross-national studies of consumer perceptions of mass customization and service personalization, and their impact on customer satisfaction, have sought to answer this question. For example, research comparing service encounters in Japan and the U.S. examined various dimensions of a service encounter for their importance in influencing customer satisfaction. The findings show that personalization is significantly more important, and formality is significantly less important, for driving customer satisfaction in the U.S. relative to Japan (Winsted, 1999). Somewhat contrarily, another study finds that customers from China emphasize both lifestyle and social norms-related attributes and expect personalized services, while customers from North America emphasize lifestyle-related attributes and expect standardized services (Ying, Chan, & Qi, 2020). Given that both studies are focused on similar contexts (restaurants and hospitality, respectively), the divergence in findings could be driven by a comparison of customers from the U.S. with those from Japan in the former and China in the latter, as independent research has documented significant differences between the cultural values of Japan and China (Globe, 2020; Hofstede, 1984). Another illuminating experimental study finds that mass customization strategies (by attributes versus by alternatives) must be tailored to consumer's cultural information processing styles, as Western and Eastern consumers’ satisfaction, likelihood of purchasing, and the amount of money spent are driven differentially by customization strategies (Bellis, Hildebrand, Ito, Herrmann, & Schmitt, 2019). Finally, in a study comparing consumers across the U.S., China and Canada, the authors find that high service attentiveness can backfire in some contexts, and particularly among East Asian consumers, with these efforts inducing negative consumer responses (as diminished customer satisfaction and patronage likelihood) through suspicions of ulterior motives (Liu, Zhang, & Keh, 2019). In the aggregate, these studies, along with related research (e.g., Ruyter, Wetzels, Lemmink, & Mattsson, 1997; Fong, He, Chao, Leandro, & King, 2019), point towards differential consumer reactions to service customization and personalization efforts across national markets, offering a warning to multinational service providers to carefully “customize” their customization efforts to local cultural standards and norms.

What we don’t know. Despite the above, at least three gaps emerge in this cluster of research on customization and personalization that can be addressed in future research. First, given a dominant focus on services, the extant research does not provide much insight into cross-national or cross-cultural variation in the effects of customization and personalization on customer satisfaction vis-à-vis products, an equally important consideration for many MNEs marketing durable and nondurable goods. This is a notable omission because customization and personalization of products (versus services) involve different trade-offs by firms with important implications for customer satisfaction (Anderson et al., 1997) Second, this research provides little understanding of why the effects of customization and personalization on customer satisfaction differ across cultures and countries. Separate research conducted within the U.S. finds that customization leads to favorable customer outcomes by providing a better preference fit for customers. A prerequisite for such effects of customization is the ability of firms to know what customers actually want (Franke, Keinz, & Steger, 2009). As such, it needs to be examined whether the variability in the preference for customization and its effects on customer satisfaction across markets is driven by differences in customers’ insights into their own preferences or their ability to express these preferences. Third, these articles do not provide an understanding of how customers might respond differently (e.g., concerning their satisfaction evaluation) across cultures and nations when a self-customized (versus standardized) product or service fails. Some guidance on the matter, though not in the international business context, can be found in recent research that finds when consumers have some control (versus no control) over the production process (and thus customization) they have lower purchase intentions for products manufactured with unethical processes (e.g., underpaid labor) (Paharia, 2020).

Corporate reputation and brand image

What we know and its implications. How well do intangible (marketing) assets like corporate reputation and brand image translate across national markets? Do these intangible assets affect customers’ satisfaction and loyalty with goods and services across national markets similarly? Such questions are vital to firms with established brands seeking to expand operations to new markets (i.e., international brand scope), and some third-generation studies have sought to answer these questions. For example, the effects of firm reputation on customer satisfaction and of customer satisfaction on customer loyalty have been found to be stronger in South Korea – a collectivist, high uncertainty avoidance, high context, and low-trust society – than in United States – a low uncertainty avoidance, low context, and high-trust society (Jin, Park, & Kim, 2008). Findings also show that financial strength and corporate social responsibility (CSR) are the most important (and positive) cognitive drivers of corporate reputation, and that satisfaction is the most important (and positive) emotional driver of corporate reputation, at least in the two markets examined (Spain and the U.K.) (Ruiz, Garcia, & Revila, 2016). Taken together, these findings show that the strength of the relationship between the examined intangible assets and customer satisfaction differs across countries and cultures. Driven by the knowledge of such variability, practitioners need to incorporate country and cultural contexts into their decision calculus for driving customers satisfaction most efficiently through investments in intangible assets.