Abstract

The recent rise in protectionism and demonization of foreign countries has increased the risk of brands falling victim to the negative effects of consumer animosity, or strong negative affect directed at a foreign country. We investigate the role of cultural values as moderating the relationship between consumer animosity and willingness to buy. The combined results of a meta-analysis and six experiments in the US and China offer strong evidence that collectivism and long-term orientation mitigate the negative effects of consumer animosity and support the contention that animosity’s effect on willingness to buy is much stronger than on product judgments.

Resume

La montée récente du protectionnisme et de la diabolisation des pays étrangers a accru le risque que les marques soient victimes des effets négatifs de l’animosité des consommateurs, ou d’un fort effet négatif dirigé contre un pays étranger. Nous étudions le rôle des valeurs culturelles comme modérateur de la relation entre l’animosité des consommateurs et leur volonté d’acheter. Les résultats combinés d’une méta-analyse et de six expériences menées aux États-Unis et en Chine montrent clairement que le collectivisme et l’orientation à long terme atténuent les effets négatifs de l’animosité des consommateurs et appuient l’affirmation selon laquelle l’effet de l’animosité sur la volonté d’acheter est beaucoup plus fort que sur le jugement des produits.

Resumen

El reciente aumento del proteccionismo y la demonización de los países extranjeros ha aumentado el riesgo de que las marcas sean víctimas de los efectos negativos de la animadversión de los consumidores, o de un fuerte efecto negativo dirigido a un país extranjero. Investigamos el rol de los valores culturales como moderadores de la relación entre la animadversión del consumidor y la disposición a comprar. Los resultados combinados de un metaanálisis y seis experimentos en los Estados Unidos y China ofrecen una fuerte evidencia que el colectivismo y la orientación a largo plazo mitigan los efectos negativos de la animadversión del consumidor, y respaldan la alegación que el efecto de la animadversión sobre la disposición a comprar es mucho más fuerte en juicios de producto.

Resumo

O recente aumento do protecionismo e demonização de países estrangeiros aumentou o risco de marcas serem vítimas dos efeitos negativos da animosidade do consumidor ou de um forte efeito negativo direcionado a um país estrangeiro. Investigamos o papel dos valores culturais como moderadores da relação entre animosidade do consumidor e vontade de comprar. Os resultados combinados de uma meta-análise e seis experimentos nos EUA e na China oferecem fortes evidências que coletivismo e orientação a longo prazo atenuam os efeitos negativos da animosidade do consumidor, e sustentam a alegação que o efeito da animosidade na vontade de comprar é muito mais forte do que no julgamento de produtos.

摘要

近期的贸易保护主义和对外国妖魔化的上升增加了品牌成为消费者敌意的负面影响或直接针对外国的消极情绪的受害者的风险。我们调查文化价值在调节消费者敌意与购买意愿之间关系中的作用。汇总分析和在美国和中国的六个实验的综合结果提供了有力的证据, 表明集体主义和长远导向减轻了消费者敌意的负面影响, 并支持敌意对购买意愿的影响远大于对产品判断的影响的论点。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Consumer animosity, defined as “anger related to previous or ongoing political, military, economic, or diplomatic events” (Klein, 2002: 346), has become an important international consumer behavior concept. Early studies focused on “old” conflicts as the source of a stable enduring animosity, for example, Chinese consumers animosity toward Japan (Klein, Ettenson, & Morris, 1998) or Dutch animosity toward Germany (Nijssen & Douglas, 2004), stemming from World War II atrocities. Other studies have focused on transient anger following more recent perceived injustices. For example, Muslim anger with Denmark, following the publication of cartoons depicting the prophet Muhammad (Knight, Mitchell, & Gao, 2009) or Australian anger toward France following nuclear tests in the South Pacific (Ettenson & Klein, 2005). The effects on consumer behavior are similar whether the animosity is stable (i.e., enduring deep-rooted animosity based on perceived historical injustices) or situational (i.e., event-driven transient animosity) (Leong et al., 2008).

Research on animosity has made important discoveries to help us better understand the phenomenon. Although some consumers may be uninterested and unaware of geopolitical events and accuracy of knowledge about products’ origins vary (Samiee, 1994; Samiee, Shimp, & Sharma, 2005), research in a wide variety of contexts has shown that consumers around the world may experience animosity (Funk, Arthurs, Trevino, & Joireman, 2010; Papadopoulos, El Banna, & Murphy, 2017) that can even extend to B2B markets (Edwards, Gut, & Mavondo, 2007). Furthermore, the recent rise in economic protectionism (Ghemawat, 2017; Witt, 2019) along with the increasing ability of consumers to act on their anger and become activist consumers through technological tools, e.g., social media (McGregor, 2018; Miller, 2016), has heightened the risk of brands falling victim to negative consequences due to their country association, at the hands of consumers drawing such country-brand associations. Thus, we identify several research gaps that are important to address.

First, the primary theoretical contribution from the seminal Klein et al. (1998) animosity model (hereafter KEM animosity model) is the assertion that animosity affects consumers’ behaviors (i.e., product ownership and purchase intentions), but not product judgments (i.e., perceptions of quality). A number of subsequent studies support this hypothesis (e.g., Funk et al., 2010; Klein, 2002; Maher & Mady, 2010). However, other studies have found that animosity is related to both behavior and product judgments (e.g., Ettenson & Klein, 2005; Leong, et al., 2008). Thus, mixed empirical evidence casts doubt on this key theoretical assertion of the KEM animosity model.

A better understanding of this discrepancy has implications for our theoretical understanding of buying decisions. Traditional behavioral frameworks suggest that attitudes are the central precursor to buying intentions (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975); whereas the KEM animosity model suggests an important role for animosity. This also has practical implications. Many marketing communication strategies are focused on enhancing perceptions of product quality. Yet, such strategies are likely to be ineffective if animosity affects purchase decisions independent of product judgments. Thus, in such instances, brand managers may benefit more from other communication strategies (see Klein, Smith, & John, 2004; Knight et al., 2009). Given the lack of conclusive evidence to indicate the degree to which animosity affects willingness to buy relative to product judgments and its theoretical and practical importance, this study aims to address this gap.

A second, and in our view, more important research gap is the lack of cross-cultural comparisons with respect to the effect of animosity on willingness to buy and product judgments. Even though evidence of animosity has been found in many countries around the world, the assumption that the effect of animosity is unchanged from one cultural context to another is dubious. Most studies have focused only on a single country precluding cross-cultural comparisons (e.g., Klein et al., 1998; Shoham, Davidow, Klein, & Ruvio, 2006). Only a few studies have included multiple countries, but they have focused on other issues leaving the question of cross-cultural differences unaddressed (e.g., Abraham & Reitman, 2018; Harmeling, Magnusson, & Singh, 2015; Leong et al., 2008). We address this gap by examining whether cultural values moderate the animosity–willingness to buy relationship.

We posit that cultural values likely influence the effects of consumer animosity based on the influence of values in regulating emotion-based responses, so that an individual’s response is consistent with those values (Ho & Fung, 2011). For example, culture shapes and influences the outward expression of emotion, encouraging the expression of socially engaging emotions in individualist cultures (Kitayama, Mesquita, & Karasawa, 2006), and discouraging the expression of negative emotions in collectivist cultures (Butler, Lee, & Gross, 2007). Further, values have a propensity to predict preferences (Olson & Zanna, 1993) and an ability to affect behavior (Feather, 1990; Mintz, Currim, Steenkamp, & de Jong, 2019); indeed, cultural values are an underlying influence in shaping behavior of individuals (Hofstede, 2001).

The animosity literature’s lack of accounting for cross-cultural differences is relevant because of its implications for a company’s strategic response in markets where consumers hold animosity toward the brand’s home country. The effect of animosity may be magnified or muted, depending upon the country’s dominant cultural values. Thus, a company’s strategy in terms of resource allocation to address the animosity would be commensurate with the degree of its anticipated negative effects. In sum, given the lack of cross-cultural examinations and the importance of cultural values in international business, clarifying the role of cultural values is an important gap to fill.

Thus, this study aims to address two important research questions: (1) the magnitude of the effect of animosity on willingness to buy relative to the effect on product judgments, and (2) how cultural values influence the negative effects of animosity. To accomplish this objective, we employ a multi-method approach. First, we conduct a meta-analysis of the consumer animosity literature. Meta-analysis is a valuable technique for integrating and expanding the base of knowledge on research topics (Kirca, et al., 2011). It is well suited for resolving theoretical disputes in a more definitive way than any single study because of its ability to synthesize empirical research over a variety of studies (Schmidt & Hunter, 2015). Second, following the meta-analysis, we employ a number of experiments, drawing on samples from both the US and China. Experiments are well suited for offering evidence of causation, and their use in international business research has been encouraged (Zellmer-Bruhn, Caligiuri, & Thomas, 2016). Each method contributes complementary insights into both research questions, thus the analytical approach is robust and rigorous.

We proceed by offering background on the consumer animosity literature. This serves as the foundation for our hypotheses on the effect of animosity on willingness to buy relative to product judgments and how cultural values influence the animosity–willingness to buy relationship. Afterward, we describe the method and results of the Study 1 meta-analysis, followed by six experiments. Finally, we discuss the results and provide managerial and theoretical implications.

CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

Consumer Animosity Consequences

Consumer animosity refers to consumers’ strong feelings of dislike or even hatred toward a country due to its political, military, or economic behavior (Klein et al., 1998). Thus, at its core, consumer animosity is a strong negative affect directed at a particular country (Leong et al., 2008). Most commonly, a history of war or economic repression has been the antecedents driving consumer animosity, but some studies have focused on different drivers (Riefler & Diamantopoulos, 2007). For example, feelings of animosity can be based on religious differences (Shoham et al., 2006), or concerns about a country’s social and environmental practices (García-de-Frutos & Ortega-Egea, 2015).

The main consequence of consumer animosity is its negative effect on willingness to buy (Klein, 2002). For example, after the US implemented tariffs against a significant range of Chinese products in 2018, the microblogging site Weibo featured comments such as “do your duty…don’t buy US products” (Kubota, Deng, & Li, 2018). A remaining question is whether animosity will have the same negative effect on product judgments. In the initial conceptualization of the KEM animosity model, it was argued that animosity affects behavior (i.e., ownership and purchase intentions) without affecting product judgment. According to Ettenson and Klein (2005: 203), “consumers withhold consumption of products or brands [from a given country] not because of concerns about quality or value, but because these goods are associated with actions that the consumer finds objectionable.” Angry consumers “do not distort or denigrate images of a target country’s products, they simply refuse to buy them” (Klein, 2002: 347). For example, a Chinese consumer may acknowledge the high quality of Japanese brands, yet due to animosity arising from their historically turbulent relationship refuse to buy them.

The contrasting effect on behavior versus product judgments advanced by the KEM animosity model is an important theoretical distinction from traditional behavioral frameworks, where attitudes are viewed as a central precursor to behaviors (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Yet, not all researchers have agreed with this perspective and several studies have indeed found a negative relationship between animosity and both willingness to buy and product judgments (e.g., Leong et al., 2008; Shoham, et al., 2006), which makes this question theoretically meaningful and important to address.

Theoretically, the link between a consumer’s negative emotions (i.e., anger toward a country) and behaviors (i.e., boycott of products from that country) can be explained by a family of related social psychology theories, which all emphasize the desire for congruity between emotions and behaviors (Festinger, 1957; Heider, 1946; Lazarus, 1991). In short, when people experience negative emotions in response to a situation, there is a need for a coping behavior, or an effort to alleviate distress caused by the negative emotion. In the context of animosity, boycott behavior is a coping mechanism to create balance between the consumer’s emotional state and his or her actions (Harmeling et al., 2015).

However, the type of coping mechanism tends to differ based on the type of negative affect (Roseman, Wiest, & Swartz, 1994). Anger is an outward, “fight”-focused emotion that prompts the desire to punish the offending country, leading to lower purchase intentions. However, anger is more visceral than cognitive, and cognition would be necessary to revise product judgments. Angry individuals tend to act instinctively and focus on getting revenge (Mitchell, Brown, Morris-Villagran, & Villagran, 2001). In contrast, other negative emotions, such as fear and sadness, are related to more in-depth thoughts. Such negative emotions tend to be associated with “flight.” Further, fighting back is not viewed as a viable option, and therefore, to cope, people are more likely to revise and downgrade cognitive thoughts about the offending entity, leading to negative product judgments (Zourrig, Chebat, & Toffoli, 2009).

Animosity generally refers to anger and most animosity measurements include at least one item directly referring to anger (Klein et al., 1998). However, it is likely that some studies implicitly capture other negative emotions, e.g., anxiety and insecurity (Leong et al., 2008), which may lead to differential effects on willingness to buy and product judgments. Harmeling et al. (2015: 681) found that when animosity feelings are dominated by anger, angry consumers “tend to act instinctively and focus their anger on taking measures to exact revenge.” In contrast, when the animosity feelings are dominated by fear, consumers are more likely to employ systematic, mindful deliberation about the threatening stimuli, suggesting that fear-based animosity is significantly related to product judgments. Given that the conceptual definitions and operationalization of animosity has been dominated by anger, we posit that there will be a much stronger effect of animosity on willingness to buy than on product judgments.

Hypothesis 1:

Consumer animosity will have a stronger negative effect on willingness to buy than on product judgments.

Cultural Values

We suggest that the implicit assumption that the effect of animosity is invariant across cultures is flawed, and that there are conditional effects of consumer animosity based on the cultural values of the evaluator. Culture is the pattern of thinking, feeling, and acting, or software of the mind, the core of which is formed from values. These cultural values are “broad tendencies to prefer certain states of affairs over others” (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010) and cultural values are inextricably linked to affect that can motivate behavior (Schwartz, 2007). Cultural values have also been found to moderate the influence of emotions on evaluative judgments (Schoefer, 2010). Thus, it is logical to expect some interaction between emotion, i.e., anger/animosity and cultural values with respect to the consumer animosity–willingness to buy relationship.

We view cultural values through the theoretical lens of the Hofstede (2001) cultural framework because it has been the most influential framework used in international marketing research (Steenkamp, 2019) and demonstrates strong convergent validity compared to alternatives (Magnusson, Wilson, Zdravkovic, Zhou, & Westjohn, 2008). Whereas Hofstede’s framework provides a broad set of dimensions, it has been recommended to focus only on the values most theoretically related to the outcome of interest (e.g., Hofstede, 1983; Tung & Verbeke, 2010). Three of the dimensions, collectivism, long-term orientation, and power distance appear to be closely related to how people regulate emotion and deal with conflict. Accordingly, we develop a priori hypotheses for these three cultural value dimensions. Even though, we do not find theoretical justification for developing hypotheses for masculinity and uncertainty avoidance, we include them in the meta-analysis and assess their effects.

Investigating the role of cultural values at the societal level with a meta-analysis (Study 1) establishes correlational evidence. However, as Oyserman and Lee (2008) assert, to provide stronger evidence of the causal effect, priming cultural values at the individual level is necessary, since manipulating cultural values at the societal level is not possible. Although the Hofstede cultural dimensions have been conceptualized as societal, or country-level constructs (Hofstede et al., 2010), there is strong evidence of the structural similarity of values at the individual and country levels (Fischer, Vauclair, Fontaine, & Schwartz, 2010; Peterson & Barreto, 2018). Moreover, the corresponding constructs manifest at the individual level can be primed and made temporarily accessible (Leung & Morris, 2015; Oyserman & Lee, 2008).

For example, research has shown that people in high power distance societies generally have higher individual-level power distance orientation (Lian, Ferris, & Brown, 2012; Winterich & Zhang, 2014) and that the value can be made temporarily salient through priming. Similar findings have been established for the individualism dimension, generally labeled independent versus interdependent self-construal at the individual level (Markus & Kitayama, 1991) and for long-term orientation (Bearden, Money, & Nevins, 2006). Thus, we expect converging and robust evidence about the moderating effects of cultural values at both the societal level (examined in the meta-analysis—Study 1) and when made temporarily accessible through priming at the individual level (examined in the experimental studies—Studies 2, 3 and 4).

Individualism-Collectivism

The individualism-collectivism cultural value dimension refers to whose interests should prevail, the interests of the individual or the interests of the group. In individualist societies, ties between individuals are relatively loose with the expectation that individuals should care for themselves and their immediate family. On the other hand, in collectivist societies, ties between individuals are very strong, based on group membership determined from birth (Hofstede, 2001). This value dimension presents an interesting case insofar as there are compelling arguments to believe that both individualists and collectivists would act on their animosity more than the other. Consequently, we present competing hypotheses.

First, there is reason to suggest that individualism strengthens the relationship between animosity and willingness to buy. Kitayama et al. (2006) found that highly individualist cultures, such as the United States, foster emotions such as pride and anger, which stands in contrast to collectivist cultures, such as Japan, which fosters more positive emotions. This is logical, as those with an independent self-construal strive to assert their individualism and uniqueness, and stress their separateness from the social world (Heine & Lehman, 1995). Notably, this includes an emphasis on speaking one’s mind and acting on one’s feelings (An, Chen, Li, & Xing, 2018), accompanied by a low aversion to confrontation (Hofstede, 2001). Not surprisingly, customer complaints, a type of consumer action, are more common in individualist compared to collectivist cultures (Liu & McClure, 2001).

In contrast, key attributes of an interdependent worldview involve the role of harmony and confrontation avoidance. Maintaining harmony is important in collectivist cultures, motivating collectivists to avoid confrontations; whereas the individualist tendency to speak one’s mind is more likely to invite confrontation (Hofstede, 2001). Given that consumer animosity reflects a relationship in dis-harmony and indicates a confrontational state of affairs, collectivist cultures are more likely to suppress such confrontational responses, and show a preference for expressing more positive socially engaging emotions (Kitayama et al., 2006), which would mitigate the effect of consumer animosity on willingness to buy.

Further, in a collectivist society, people are more likely to forgive brand transgressions (Sinha & Lu, 2016), due to their tendency to suppress emotion-based responses (Butler et al., 2007). When faced with a transgression, individualists perceive injustice or unfairness that needs to be remedied; whereas collectivists perceive a threat to social harmony that calls for forgiveness (Ho & Fung, 2011). This inclination toward forgiveness indicates that a country’s transgressions are more likely to be forgiven by those with a collectivist mindset.

Hypothesis 2a:

The negative effect of animosity on willingness to buy is weakened under conditions of collectivism (versus individualism).

Competing hypothesis

Although there is theoretical justification for the preceding hypothesis, one may put forward an alternative explanation. An interdependent worldview makes a strong distinction between the in-group and out-groups. Whereas the interdependent self is attuned to the concerns of others, oftentimes, such concerns are limited to “when there is a reasonable assurance of the ‘good-intentions’ of others, namely their commitment to continue to engage in reciprocal interaction and mutual support” (Markus & Kitayama, 1991: 229). An offending country, subject to animosity feelings, is not a member of the in-group and has not proven a reasonable assurance of good intentions. As such, the concern for harmony with others that is typical of an interdependent worldview may not be salient when dealing with an offending country considered part of an out-group. Further, belongingness needs are very strong for individuals who are more interdependent (White, Argo, & Sengupta, 2012). Fractious relations with another country may be perceived as a social identity threat that activates the need to reinforce belongingness to one’s own national group, and manifest itself with the preference against brands from the offending country.

Further, from a thinking styles perspective, individualism and collectivism are associated with opposite modes, analytic and holistic thinking, respectively. Individualists tend to engage in analytical thinking, which hinges on the “detachment of the object from its context,” and therefore exclude contextual information such as animosity. On the other hand, collectivists tend to engage in holistic thought processes viewing objects and events as “an orientation to the context or field as a whole” (Krishna, Zhou, & Zhang, 2008), and are more likely to be affected by the situational context (Choi, Dalal, Kim-Prieto, & Park, 2003).

Thus, based on the in-group out-group distinction, and analytical versus holistic thinking arguments, it also seems reasonable to expect that consumers from collectivist cultures would exhibit a stronger association between their animosity and willingness to buy. Accordingly, we advance the following competing hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2b:

The negative effect of animosity on willingness to buy is strengthened under conditions of collectivism (versus individualism).

Long-Term Orientation

Long-term orientation, originally referred to as Confucian dynamism, was introduced by Hofstede and Bond (1988) and added to Hofstede’s (1980) four original cultural dimensions. It is defined as the extent to which a society exhibits a pragmatic future-oriented perspective fostering virtues like perseverance and thrift, rather than a conventional short-term point of view (Hofstede, 2001). It has also been called the difference between focusing on the “here and now” versus a holistic view of the future and the past (Bearden et al., 2006). We identify two key characteristics of long- versus short-term orientation that suggest that it may play a moderating role in the animosity–willingness to buy relationship.

First, long-term-oriented cultures regard emotions as dangerous and threatening to long-term relationships, thus high long-term orientation encourages muted or softened responses in order to preserve positive relations for the long-term future (Matsumoto, Yoo, & Nakagawa, 2008). This long-term perspective of relationships suggests a lower likelihood of changing behavior toward brands from an offending country. Qualitative results support this perspective and indicate that long-term orientation explains why Chinese more so than Americans tend to avoid direct conflict, insofar as direct conflict hurts the long-term relationship (Friedman, Chi, & Liu, 2006).

Second, short-term orientation is associated with a strong need for cognitive consistency, whereas long-term-oriented societies have a weaker need (Hofstede et al., 2010). This means that emotions (i.e., I am upset with country x) are expected to be closely aligned with a consistent behavioral response (i.e., I will not purchase products from country x) to avoid mutually conflicting bits of information. Thus, short-term orientation is associated with “having an invariant self that does not change across situations” (Minkov et al., 2017: 311). In contrast, long-term orientation emphasizes flexibility and the need for cognitive consistency tends to be weaker. This suggests that long-term-oriented societies find that holding contradictory feelings are less problematic (Hofstede et al., 2010), implying that maintaining intentions to buy from a country despite personal anger directed at that country, is more acceptable due to the cultural ideal of maintaining a long-term orientation. This does not, however, mean that long-term orientation is associated with fickleness. Instead, all cultural tendencies, including the need for cognitive consistency, and the prevalence of these traits are not about presence versus absence, but about relative frequency or relative importance (Minkov et al., 2017).

Thus, the strong need for cognitive consistency in short-term-oriented cultures suggests a strong relationship between animosity and purchase intentions. However, long-term orientation favors a pragmatic view where what works is more important than being consistent (Hofstede & Minkov, 2010). As a result, the coexistence of consumer animosity toward a country along with a seemingly inconsistent willingness to buy products from that country may simply be practical and pragmatic. In sum, based on differences in terms of focus on a more holistic view to time and relationships, as well as the weaker need for cognitive consistency, the effect of consumer animosity on willingness to buy should be relatively weaker in long-term-oriented societies.

Hypothesis 3:

The negative effect of animosity on willingness to buy is weakened under conditions of long- (versus short-) term orientation.

Power Distance

Power distance captures the extent to which a society accepts inequality in power, wealth, and prestige (Hofstede, 1980). Central to this concept is that power distance does not refer to the actual power disparity a person experiences or the amount of power a person has, but rather to attitudes toward power disparity (Oyserman, 2006). Power distance is typically referred to as power distance belief or power distance orientation when discussed at the individual level (Lian et al., 2012; Winterich & Zhang, 2014). Whereas there is variance within any given society, in high (low) power distance societies, people tend to have higher (lower) power distance beliefs (Earley, 1999, Zhang, Winterich, & Mittal, 2010).

We posit that consumers’ power distance beliefs may influence how strongly they respond to feelings of animosity. High power distance societies tend to discourage assertiveness and encourage emotion regulation. They emphasize social order and restraint of actions that might disrupt that order; thus, suppression of emotion-based responses may be necessary (Matsumoto et al., 2008). The emphasis on obedience and respect carries into organizational behavior. For example, people with high power distance beliefs are less likely to react negatively to injustices from superiors (Lee, Pillutla, & Law, 2000), less concerned about not having a voice in organizational decision making (Brockner, Paruchuri, Idson, & Higgins, 2002), and more accepting of an insult delivered by a superior to a subordinate (Bond, Wan, Leung, & Giacalone, 1985).

In contrast, low power distance is associated with characteristics such as equality and initiative (Hofstede, 1980). For example, visits to the doctor are expected to be consultative, superiors are expected to consult with subordinates, and learning emphasizes two-way communication between teacher and students (Hofstede et al., 2010). Accordingly, people with low power distance beliefs are less likely to defer to authority and more likely to actively challenge perceived injustices (Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen, & Lowe, 2009).

Logically, this should extend to perceived injustices involving countries. Animosity feelings derive from injustices where a (typically superior) country has caused feelings of injustice due to its military or economic power. People with high power distance beliefs are accustomed to behaving in a subservient manner, and active resistance or dissent is not expected. Thus, despite perceived injustice, challenging the offender by taking action would be inconsistent with the cultural value of high power distance. In contrast, low power distance beliefs encourage voice and initiative, and a sense of fairness dictates that injustices be reconciled, which leads to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4:

The negative effect of animosity on willingness to buy is weakened under conditions of high (versus low) power distance.

STUDY 1: META-ANALYSIS

Database Development

To ensure the representativeness and completeness of our database, we used a multi-step sampling procedure to identify studies to be included in the meta-analysis. In the first step, we systematically searched the ABI/INFORM and Business Source Ultimate databases for articles using the keywords “animosity” and “consumer animosity.” The results of our search indicated that Klein et al. (1998) initiated the research stream on consumer animosity with respect to willingness to buy and product judgments; thus, the database of correlations we developed covers the period beginning in 1998 and ending in mid-2018. Second, we examined references of all papers identified as suitable in the previous step. Finally, for papers that appeared suitable but lacked critical pieces of information (i.e., correlations matrix), we e-mailed authors to request the data.

To be included in the meta-analysis, studies needed to have reported relationships involving one or more operationalizations of animosity and either willingness to buy or product judgment; moreover, only those studies that measured constructs at the consumer level were included so that results from research that had vastly divergent goals were not aggregated. Procedures recommended by Lipsey and Wilson (2001) were followed for the development of the final database. First, to reduce coding errors, we prepared a coding protocol specifying the information to be extracted from each study. An initial draft of the coding protocol was revised on the basis of feedback from international marketing scholars and meta-analysis experts regarding the appropriateness of the coding scheme. Then, a coding form was prepared for coders who recorded the extracted data on the variables of interest, including correlation coefficients, study sample sizes, statistical artifacts (i.e., measure reliability statistics), and study characteristics. Two coders knowledgeable about the animosity literature coded each study. Initial agreement between the two coders exceeded 95%, suggesting that the reliability of the coding process was high (Perreault Jr & Leigh, 1989). Remaining discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus reached. Upon completion of the search and data coding process, we had collected results from 43 independent samples covering 18 countries and reported in 37 studies. The Web Appendix lists all studies included in the meta-analysis.

Data Analysis

To be included in the study, each study had to capture consumer’s animosity directed at a nation. Measurement of consumer animosity has been as a first-order construct in most cases, but ten (out of 43) studies used multiple first-order measurements (e.g., war and economic animosity) to create a second-order construct. In such cases, it is recommended to create a composite correlation from the first-order dimensions and enter only one correlation into the meta-analysis, as opposed to two or three from the same study, in order to avoid under-estimation of sampling variance (Eisend, Hartmann, & Apaolaza, 2017, Schmidt & Hunter, 2015).

We then corrected the effects obtained from each study by dividing the correlation coefficient by the product of the square root of the reliabilities of the two constructs (Schmidt & Hunter, 2015). For studies that did not report reliabilities or used single-item measures, we used the mean reliability for the construct from the remaining studies for the reliability correction (e.g., Geyskens, Steenkamp, & Kumar, 1998). After the correction, we transformed the corrected correlations into Fisher’s z-coefficients, and assigned weights by taking the inverse of the estimated within-study variance. Finally, we estimated the effect size using a random-effects model, converted the Fisher’s z-coefficients back to correlation coefficients, and calculated 95% confidence intervals (Rosenthal, 1994).

The meta-analysis focuses on the bivariate relationship between animosity and willingness to buy and product judgments; however, most animosity studies like Klein et al.’s (1998) seminal work include consumer ethnocentrism (CET), i.e., the belief that purchasing foreign products is inappropriate and immoral (Shimp & Sharma, 1987). Thus, in order to provide an additional perspective on the effect of animosity, we conducted a meta-analytic path analysis that includes both animosity and CET as predictors of both product judgments and willingness to buy. We conducted the path analysis in AMOS using the correlations estimated by the meta-analysis as input and the harmonic mean sample size of 262 (e.g., Rubera & Kirca, 2012).

Finally, to determine whether the variation in effect size could be explained by moderator variables, we calculated heterogeneity tests. The animosity–willingness to buy relationship had a significant Q-statistic (Q = 2715.00, p < 0.001), which suggests that moderator variables could be applied to explain the variation in effect sizes. Thus, we assessed whether effect sizes differed based on Hofstede’s cultural value framework. We analyzed the effect of values using both meta-regression and the analog to the ANOVA (subgroup analysis) with SPSS macros developed by Lipsey and Wilson (2001). We consider the meta-regression as the primary analysis method due to its treatment of cultural values as continuous variables resulting in greater statistical power (Irwin & McClelland, 2003). However, to facilitate interpretation of the relationships, we also employ sub-group analysis on groups reflecting the opposing poles for each cultural value dimension, e.g., collectivism group versus individualism group, long- versus short-term orientation groups. Cultural value subgroups were created using median splits calculated from all countries available in the Hofstede database, then mean effect sizes were compared across the groups. Country members of each cultural value subgroup are listed in the "Appendix".

Study 1 Results

Mean effect sizes

Estimated mean effect sizes for the two bivariate relationships of interest are reported in Table 1. The corrected mean correlation between animosity and willingness to buy is strong and negative, (r = − 0.63), and the 95% confidence interval is entirely below zero [− 0.70, − 0.54]. The relationship between animosity and product judgment is considerably weaker (r = − 0.23), although the confidence interval is also entirely below zero [− 0.35, − 0.11]. As evidence of support for H1, the confidence intervals for the two correlations do not overlap, and a test of the difference between them using the Fisher r-to-z transformation and the harmonic mean sample sizes confirm the significant difference (rwilltobuy = − 0.63, n = 262; rprodjudg = − 0.23, n = 264; z = − 5.72, p < .001). The significantly weaker association of animosity with product judgment is consistent with the theoretical argument that animosity primarily influences intentions and behavior, with lesser influence on judgments and evaluations, providing the foundation for a reluctance to buy a product despite a positive product evaluation.

Path analysis

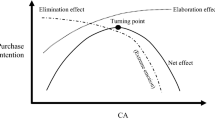

Whereas the simple bivariate correlation between animosity and willingness to buy is − 0.63, Figure 1 depicts animosity’s effect when controlling for effects of CET and product judgments. When the additional variables are included in a model to more closely resemble the KEM animosity model, animosity’s direct effect on willingness to buy is (b = − 0.41, t = − 9.85, p < 0.001). Further, the path analysis reveals that animosity is still significantly related to product judgments; however, that relationship is considerably weaker (b = − 0.15, t = − 2.28, p = 0.02). Product judgment’s effect on willingness to buy is significant (b = 0.39, t = 10.15, p < 0.001); thus, the indirect effect of animosity on willingness to buy is − 0.06. When added to the direct effect of − 0.41, the total effect of animosity on willingness to buy is − 0.47.

Cultural value moderators

The combined results, presented in Table 2, from the meta-regression and subgroup analyses indicate strong evidence of significant group differences for two of the five cultural value dimensions, collectivism and long-term orientation, and weaker evidence for power distance. The meta-regression analysis indicates a significant moderating effect of collectivism on the animosity and willingness to buy relationship (β = 0.46, p < 0.001). Subgroup analysis reveals a mean correlation in the individualism group (r = − 0.75) that was significantly stronger than the collectivism group (r = − 0.54; Q = 12.24, p < 0.001), which supports H2a over the competing H2b. In support of H3, long-term orientation also significantly moderated the relationship (β = 0.47, p < 0.001). The long-term orientation group’s mean correlation (r = − 0.54) was significantly weaker than the short-term orientation group (r = − 0.73; Q = 8.94, p = 0.003) in the subgroup analysis. Regression analysis reflects weak evidence of a moderating role for power distance (β = 0.25, p = 0.09) offering only limited support for H4. This relationship was not reflected in the subgroup analysis where the mean correlation for the high power distance group (r = − 0.60) was nominally weaker, but not significantly different from the low power distance group (r = − 0.65; Q = 0.53, p = 0.47).

Although we made no a priori hypothesis, we also assessed the effect of the two remaining cultural values. The regression analysis reports nonsignificant results for both masculinity (β = − 0.07, p = 0.65) and uncertainty avoidance (β = 0.04, p = 0.77). Consistently, the subgroup analysis also revealed nonsignificant differences in correlations, (rmasculine = − 0.67 versus rfeminine = − 0.56, Q = 2.38, p = 0.12; rlow uncertainty = − 0.62 versus rhigh uncertainty = − 0.65, Q = 0.12, p = 0.73).

Other potential moderators

In addition to cultural values, for robustness, we investigated other potential moderator variables that could account for the variation in the animosity to willingness to buy relationship. Specifically, we examined the potential effect of economic development, institutional strength, and whether the measurement of willingness to buy included items that were product category specific, e.g., cars or televisions.

Differences in economic development and institutional strength may lay a foundation upon which animosity would be magnified to the extent that there is wealth inequality or a lack of formal institutional channels for redress. We assess the potential role of economic development by examining the effect of the sampled country’s GDP on a purchasing power parity basis on the animosity to willingness to buy relationship. Results from the meta-regression analysis reveal that the effect of economic development as reflected by GDP of the sampled population is non-significant (β = − 0.005, p = 0.16). We also examine whether the magnitude of the difference, i.e., GDP of offending country minus GDP of the sampled country, affects the relationship. Again, the results were nonsignificant (β = 0.004, p = 0.13). Finally, we examine whether institutional strength of the sampled country would have an effect, using data from the Global Competitiveness Index available from the World Economic Forum to reflect institutional strength. The meta-regression results indicate a relationship that approaches, yet does not reach the threshold for significance (β = − 0.01, p = 0.08).

Regarding product category differences, only 12 studies introduce product category in the assessment of willingness to buy; many of which include only one or a couple items that are category specific (e.g., Klein et al., 1998). We compared the animosity–willingness to buy correlations based on whether the study used any product category-specific items (12 studies) versus assessing only products in general from the offending country (31 studies). The result of the analysis indicated no significant difference between the mean correlations for studies using a product category-specific measure (r = - 0.66) versus those that did not (r = − 0.62; Q = 0.32, p = 0.57). We further split the 12 studies that were product-category specific into two groups, based on the cultural connectedness of the product category. In the high cultural connection group, four studies focused on food and services; whereas eight studies focused on electronics and automobiles in the low cultural connection group. The results of the analysis indicated no significant differences between the mean correlations for the high cultural connection group (r = − 0.69) versus the low cultural connection group (r = − 0.65; Q = 0.11, p = 0.74). Given that very few studies have measured willingness to buy with product-specific measures, we advise caution in interpreting these results. However, the exploratory evidence suggests that animosity’s effect is consistent regardless of the product’s cultural connectedness.

Study 1 Discussion

The meta-analysis offers evidence that the correlation between animosity and willingness to buy (− 0.63) is approximately three times stronger than the correlation with product judgments (− 0.23). The path analysis which controls for the effects of CET and product judgments likewise reveals that the effect on willingness to buy (− 0.41) is nearly three times stronger than the effect on product judgments (− 0.15). This finding provides a valuable contribution to the animosity literature. By aggregating findings from 20 years of research on the topic, we offer baseline estimates against which future studies can compare. Although the original KEM animosity model suggests no effect on product judgments, given the difference in magnitude between the two effect sizes along with the relatively weak effect on product judgments, we conclude that these findings largely support the seminal KEM animosity model, which asserted that animosity would be most closely associated with behaviors (i.e., purchasing behaviors or intentions) and less effect on quality judgments.

Our second contribution demonstrates the moderating effect of cultural values on the relationship between animosity and willingness to buy. The analysis revealed significant moderating effects for two of the five values, indicating that collectivism and long-term orientation mitigate the negative effects of animosity (and a weak effect for power distance). This adds to our understanding of animosity effects by shedding light on how consumers’ predispositions predicted by cultural values theory influence their tendency to act on their animosity emotions. The robustness of the findings was further supported by testing and ruling out several alternative explanations.

Two important limitations temper the conclusions that can be drawn from Study 1 about the cultural value moderators. First, a meta-analysis is correlational in nature and is unable to establish convincing evidence of causation. Second, intercorrelation among Hofstede’s values, e.g., collectivism and power distance, which is 0.72 in the meta-analysis data, complicates interpretation of the results. Thus, the meta-analysis offers evidence of moderating effects of cultural values using dozens of previous studies with samples from 18 different countries, but potential collinearity and the nature of cross-sectional data limit the robustness of the findings. We address this weakness through a series of experiments.

EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES

Overview of Experiments

In Studies 2, 3 and 4, six experiments provide more clarity about which values moderate animosity’s effect and evidence of a causal relationship. We conducted experiments in the US and in China, societies with two starkly different cultural value profiles. Chronologically, we conducted the US experiments prior to undertaking the China experiments. The experiments for collectivism, long-term orientation and power distance all produce results that are consistent across both the US and Chinese samples, and with results found in pre-tests at an earlier stage of the investigation; thus, the results are robust and replicable.1

In the US experiments, we selected Colombia as the target of animosity. Colombia was deemed appropriate due to (1) a history of tension, particularly surrounding drug trafficking and its resultant economic and social harm, and (2) Colombian consumer products (e.g., coffee and other food products) are readily available to US consumers. Combined, these factors make Colombia an appropriate choice to examine the theoretical predictions. Further, in order to ensure a sufficient presence and variance in animosity, we primed animosity by asking participants to read a fictitious story about Colombia in a similar manner as prior research (Magnusson, Westjohn, & Sirianni, 2019).2

For the Chinese experiments, we selected Japan as the target of animosity, given its difficult history with China and that it has been used in other animosity studies, (e.g., Klein et al., 1998). Thus, instead of priming animosity, we relied on the presence of enduring stable animosity toward Japan. The Chinese versions of the surveys were translated into Chinese by two bilingual academics and discrepancies between the two versions were reconciled through discussion (Douglas & Craig, 2007). Subsequently, it was back-translated into English to ensure equivalence, following best practices in international marketing research (Brislin, 1970).

Consistent with the conceptualization of animosity as an anger-based emotion and drawing on Roseman’s (1984) structure of emotions, we measure animosity with four items (anger, frustration, dislike, and irritation) adapted from Klein et al. (1998) and Harmeling et al. (2015). Following the measurement of animosity, in each experiment, we primed two levels of one of the cultural value moderators, i.e., individualism versus collectivism, short- versus long-term orientation, and low versus high power distance, using established priming techniques (e.g., Kopalle, Lehmann, & Farley, 2010; Trafimow, Triandis, & Goto, 1991; Zhang et al., 2010). We analyze the effect of animosity on willingness to buy and product judgments at the two levels of the primed cultural value moderators. Thus, the experiments are considered to be a 2 × continuous, between-subjects design, which we analyze using moderated multiple regression due to the continuous nature of the focal antecedent (Spiller, Fitzsimons, Lynch Jr, & McClelland, 2013). Although the primary purpose of the experiments is to further test the effects of cultural value moderators, we also assess the relative effect of animosity on willingness to buy versus product judgments. Thus, the experiments provide tests of all five hypotheses.

Study 2—COL: Participants and Procedure

In Study 2—COL, we more closely investigate the role of collectivism as a moderator of animosity’s effect on willingness to buy. In the US experiment, we recruited 86 non-student participants (Mage = 37, 50% male) from Amazon Mechanical Turk online consumer panel to participate in this experiment. The procedure described above generated sufficient animosity (M = 4.21, SD = 1.85) with strong reliability (α = 0.93). In the Chinese experiment, we recruited 85 student participants (Mage = 22, 28% male)3 from the business school of a major university in Nanjing, China. A graduate student administered the survey in the classroom. Animosity for the Chinese sample (M = 4.31, SD = 1.21) also had strong reliability (α = 0.86). The use of student samples in the Chinese experiments were deemed appropriate because the phenomenon under study is a fundamental research question examining the basic characteristics of human nature; and the student samples serve as corroborating evidence to the meta-analysis and consumer panel experiments (Bello, Leung, Radebaugh, Tung, & Van Witteloostuijn, 2009).

Participants were randomly assigned to either the individualism or collectivism condition, and completed an adapted version of the similarities and differences with family and friends priming task (Trafimow et al., 1991). For the individualism condition, participants described three things that make them unique from their family and friends. They then described a time when they achieved a goal resulting from figuring something out independently. For the collectivism condition, participants described three things that they have in common with their family and friends, followed by describing a time when they sacrificed something for the good of the group. All primes are listed in the Web Appendix.

As a manipulation check, individualism-collectivism was then assessed with a three-item scale (αUS = 0.89, αChina = 0.79) based on (Yoo, Donthu, & Lenartowicz, 2011). Following the cultural value priming task and manipulation check measure, willingness to buy (αUS = 0.94, αChina = 0.85) and product judgments (αUS = 0.94, αChina = 0.88) were measured with scales adapted from (Klein et al., 1998). Then the remaining non-primed values were measured, and finally demographics.

Study 2—COL: Results

We first evaluated the effectiveness of the individualism-collectivism priming task in a MANOVA with all five cultural values as dependent variables; complete results are presented in Table 3. As expected, the group assigned to the collectivism task scored higher on collectivism than the group assigned to the individualism task in both the US sample (MCollectivism = 4.44, MIndividualism = 3.72, F(1, 84) = 6.34, p = 0.01) and the Chinese sample (MCollectivism = 4.40, MIndividualism = 3.85, F(1, 83) = 4.14, p = 0.04). There were no significant differences between the groups for any other cultural value, suggesting that the manipulation was successful.

To assess the moderating effect of collectivism (H2), we conducted regression analysis using model 1 of the Hayes (2017) PROCESS macro with animosity as the focal antecedent and the condition (individualism versus collectivism) as the moderator. Table 4 reports a significant interaction effect on willingness to buy for both the US sample (b = 0.41, p = 0.01) and the Chinese sample (b = 0.45, p = 0.03) suggesting a mitigating effect of collectivism. To assist in interpreting the effect, Table 4 reports the conditional effect of animosity in the US sample for the individualism group (b = − 0.73, p < 0.001), which is significantly stronger than that for the collectivism group (b = − 0.32, p = 0.01). Similar results were found in the Chinese sample with the effect for the individualism group (b = − 0.66, p < 0.001) being significantly stronger than the collectivist group (b = − 0.20, p = 0.17). The effects are illustrated in Figure 2, panels A and C. In sum, the results are consistent with the meta-analysis and indicate that when individualist values are made temporarily accessible, it leads to a stronger willingness to act on one’s animosity, supporting H2a, over the competing H2b.

Experiments—animosity interactions with collectivism and long-term orientation. Charts show animosity and willingness to buy as scaled in their original metric (1-strongly disagree to 7-strongly agree). Mean animosity is 4.21 in the US collectivism experiment, 4.11 in the US long-term orientation experiment, 4.31 in the China collectivism experiment, and 4.04 in the China long-term orientation experiment.

In addition to the moderation analysis, Table 5 reports the unconditional effects of animosity on willingness to buy versus product judgments. The estimated effects on willingness to buy in both the US (b = − 0.55, p < 0.001) and China (b = − 0.43, p < 0.001) are very similar to the results found in the meta-analysis. Further, there is a significant effect of animosity on product judgments in the US sample (b = − 0.23, p = 0.01), but the effect is not significant in the Chinese sample (b = − 0.12, p = 0.25). To assess whether the effect on willingness to buy is significantly stronger than the effect on product judgments, we conducted an equality of parameters test using AMOS. We regressed both willingness to buy and product judgments on animosity, and created a distribution of the difference between the two coefficients from 2000 bootstrap samples. The resulting 95% confidence interval of the difference between the two coefficients does not include zero in either the US sample [− 0.49, − 0.14] or the Chinese sample [− 0.52, − 0.04]. Thus, animosity’s effect on willingness to buy is significantly stronger than its effect on product judgments, offering additional support for H1.

Study 3—LTO: Participants and Procedure

In Study 3—LTO, we examine the role of long-term orientation as a moderator of animosity’s effect on willingness to buy. For the US experiment, we recruited 99 non-student participants (Mage = 35, 49% male) from Amazon Mechanical Turk online consumer panel. In the Chinese experiment, we recruited 82 student participants (Mage = 19, 27% male). The same procedures and scales were used in these experiments as in the collectivism experiments, with exception of the priming task for the cultural value. Animosity was sufficient and varied in both the US (M = 4.11, SD = 1.59) and China (M = 4.04, SD = 1.08), and the composite constructs had strong reliability (αUS = 0.90, αChina = 0.85).

Participants were randomly assigned to either the short- or long-term orientation condition. Participants in the long-term orientation condition completed a priming task that consisted of reading a short essay describing the benefits of thinking about their present day actions and their effect on the long-term future. Next, they described three benefits they had experienced from sacrificing short-term benefits in order to eventually receive long-term benefits. For the short-term orientation condition in the US, we developed a corresponding priming task. Participants read a short essay describing the benefits of focusing on the present as opposed to always concerning one’s self with the future. They then described three instances when they were distracted about past or future events, but felt better when they decided to focus on the present. To the best of our knowledge, nobody has attempted to prime long- versus short-term orientation in China before. During pre-tests, we discovered that an exact replication of the short- versus long-term orientation prime that we used in the US was not successful in China. Therefore, with guidance from experts on Chinese culture, we slightly revised the priming instructions. Consistent with original writings on long-term orientation (Hofstede, 1980), we repositioned both priming tasks in terms of Confucian ethics. The modified prime emphasized the concept of protecting face in the moment for the short-term orientation prime.

A manipulation check for short- versus long-term orientation was assessed with a three-item scale (αUS = 0.73, αChina = 0.524) based on Bearden, et al. (2006). After the priming tasks and manipulation check measure, willingness to buy (αUS = 0.89, αChina = 0.84) and product judgments (αUS = 0.90, αChina = 0.89) were measured, followed by measures for the remaining non-primed values and demographics.

Study 3—LTO: Results

The effectiveness of the short- versus long-term orientation priming task is evidenced in Table 3. As expected, the group assigned to the long-term orientation task scored higher on long-term orientation than did the group assigned to the short-term orientation task in both the US sample (MLong-term orientation = 5.07, MShort-term orientation = 4.59, F(1, 97) = 4.35, p = 0.04) and the Chinese sample (MLong-term orientation = 5.35, MShort-term orientation = 4.86, F(1, 80) = 6.04, p = 0.02). There were no differences between the groups for any other cultural value, suggesting that the manipulation was successful.

To assess animosity’s effect on willingness to buy under conditions of long-term orientation (H3), we conducted an analysis using the Hayes (2017) PROCESS macro with animosity as the focal antecedent and the condition (short- versus long-term orientation) as the moderator. Table 4 reports a significant interaction effect on willingness to buy for both the US sample (b = 0.36, p = 0.02) and the Chinese sample (b = 0.42, p = 0.03) suggesting a mitigating effect of long-term orientation, in support of H3. The conditional effect of animosity on willingness to buy in the US sample for the short-term orientation group was much stronger (b = − 0.74, p < 0.001) compared to the long-term orientation group (b = − 0.38, p < 0.001). Similar results were found in the Chinese sample with the effect for the short-term orientation group (b = − 0.59, p < 0.001) being significantly stronger than the long-term orientation group (b = − 0.17, p = 0.27). The effects are illustrated in Figure 2, panels B and D. In sum, the results indicate that short-term oriented individuals tend to act on their feelings of animosity more so than long-term oriented individuals.

We again used the equality of parameters test using 2000 bootstrap samples in AMOS to assess whether the effect on willingness to buy is significantly stronger than the effect on product judgments. The resulting 95% confidence interval of the difference between the two coefficients does not include zero in the US sample [− 0.40, − 0.01], further supporting H1. In the Chinese sample, the effect on willingness to buy (− 0.39) is stronger than the effect on product judgments (− 0.14), but the difference between the two does not reach conventional statistical significance thresholds, 95% CI [− 0.51, 0.03]. Thus, while the difference between the effect on willingness to buy and product judgments is significant in both the US and China in the collectivism experiments, the difference is significant in only the US for the long-term orientation experiment.

Study 4—PDI: Participants and Procedure

Finally, in Study 4—PDI, we investigate the role of power distance as a moderator of animosity’s effect on willingness to buy. For the US experiment, we recruited 95 non-student participants (Mage = 36, 46% male) from Amazon Mechanical Turk online consumer panel. In the Chinese experiment, we recruited 93 student participants (Mage = 20, 25% male). The same procedure and scales were used as in the prior experiments, with exception of the priming task for the cultural value. Animosity was sufficient and varied in both the US (M = 4.64, SD = 1.55) and China (M = 3.71, SD = 1.16), with strong construct reliability (αUS = 0.91, αChina = 0.88).

Participants were randomly assigned to either the low or high power distance condition, and completed a power distance priming task based on Rucker and Galinsky (2008). Participants in the high power distance group recalled an incident when they had power over another individual, i.e., when they controlled the ability of another person to get something they wanted. They then described the situation. In the low power distance group, participants described an incident of the reverse situation, i.e., when an individual had control over the participant’s ability to get something they wanted.

As a manipulation check, power distance was assessed with a three-item scale (αUS = 0.82, αChina = 0.55) based on Zhang, et al. (2010). After the priming tasks and manipulation check measure, willingness to buy (αUS = 0.90, αChina = 0.91) and product judgments (αUS = 0.92, αChina = 0.93) were measured, followed by measures for the remaining non-primed values and demographics.

Study 4—PDI: Results

Table 3 reports the effectiveness of the low versus high power distance priming task. As expected, the group assigned to the high power distance task scored higher on power distance than did the group assigned to the low power distance task in both the US sample (MHigh power distance = 5.37, MLow power distance = 4.84, F(1, 93) = 5.15, p = 0.03) and the Chinese sample (MHigh power distance = 4.80, MLow power distance = 4.31, F(1, 91) = 6.98, p = 0.01). There were no differences between the groups for any other cultural value, suggesting that the manipulation was successful.

We again conducted an analysis using the Hayes (2017) PROCESS macro with animosity as the focal antecedent and the condition (low versus high power distance) as the moderator, to assess the moderating effect of power distance hypothesized in H4. There was no significant interaction in the US sample between animosity and power distance on willingness to buy (b = − 0.02, p = 0.89), rendering the conditional effect of animosity on willingness to buy in the low power distance group (b = − 0.61, p < 0.001) no different from the high power distance group (b = − 0.63, p < 0.001); see Table 4. Likewise, the interaction in the Chinese sample was also nonsignificant (b = 0.17, p = 0.38), rendering the conditional effect of animosity on willingness to buy in the low power distance group (b = − 0.43, p < 0.01) no different from the high power distance group (b = − 0.26, p = 0.05).

Although we found no evidence of a moderating effect of power distance, the US experiment does provide further support for H1. Table 5 reports that the unconditional effect of animosity on willingness to buy (b = − 0.62, p < 0.001) was significantly stronger than its effect on product judgments (b = − 0.25, p = 0.002) as evidenced by the equality of parameters test which produced a 95% confidence interval for the difference that does not include zero [− 0.60, − 0.15]. However, this result was not replicated in the Chinese sample, 95% CI [− 0.31, 0.04].

DISCUSSION

This investigation has taken a multi-method approach to address two important research questions: (1) the magnitude of the effect of animosity on willingness to buy relative to the effect on product judgments, and (2) how cultural values influence the negative effects of animosity. The combined evidence from the meta-analysis and the experimental studies provide robust support for H1, H2a, and H3, but not H2b and H4. The strong support for the contrasting effect of animosity on willingness to buy and product judgments, as well as the moderating effects of collectivism and long-term orientation at both the societal and individual levels have a number of theoretical and managerial implications.

Theoretical Implications

The first theoretical contribution highlights the contrasting effect of animosity on willingness to buy versus product judgments. The results of the meta-analysis in Study 1, which aggregates 20 years of research on the topic, combined with the experiments of Studies 2, 3, and 4 offer more definitive evidence upon which to draw firmer conclusions and clarify the relationship.

The meta-analysis identified contrasting effect sizes of animosity on willingness to buy (− 0.63) versus product judgments (− 0.23). Four of the six experiments found evidence that the effect on willingness to buy was significantly stronger than the effect on product judgments, with average effects sizes in the experiments of − 0.48 for willingness to buy and − 0.22 for product judgments. Combined, this suggests that the effect of animosity on behavior (or behavioral intentions) is two to three times stronger than the effect on attitudes. The difference in magnitude between the two effect sizes suggests consistency with the seminal KEM animosity model, which asserted that animosity would be most closely associated with behaviors (i.e., purchasing behaviors or intentions) compared with quality judgments.

We acknowledge that the effect of animosity on product judgments is statistically significant in the meta-analysis and in four of the six experiments. Inconsistencies in past research may be due to measures that included beliefs alongside emotions, or instead of anger, captured other negative emotions such as anxiety and insecurity (Leong et al., 2008), which are fear-based emotions and have been found to affect product judgments (Harmeling et al., 2015). The rather weak effect size of animosity on product judgments may also partially explain past empirical inconsistencies as sufficient statistical power would be necessary to identify the relationship as significant. Following the recommended practice of focusing on the effect size (e.g., Meyer, van Witteloostuijn, & Beugelsdijk, 2017), we believe animosity’s weak relationship with product judgments, especially in comparison to the effect on willingness to buy found in our results, supports the KEM animosity model.

The second theoretical contribution calls attention to the role of cultural values as moderators of the consumer animosity–willingness to buy relationship. To date, the animosity literature has treated this phenomenon as a universal phenomenon and assumed no differences in how consumers reacted to feelings of animosity based on cultural worldview. However, this study reveals a previously unknown contextual influence of cultural values. Specifically, this study’s combination of a meta-analysis of samples from 18 different country cultures and six experiments in which we prime cultural values to make it temporally accessible provides robust support for the moderating effects of individualism versus collectivism and long-term orientation. The influence of these values suggests that the cultural value profile of the sample population should be considered when interpreting results of studies, especially when comparing results to samples drawn from contrasting cultures.

A careful review of the literature led to two competing theoretical predictions for the individualism versus collectivism dimension. The results are interesting insofar as theory seems to pit different aspects of the individualism-collectivism dimension against one another. For example, collectivism includes both the desire for harmony, but also affords different expectations and behavioral responses based on in- versus out-group status. The desire for harmony suggests a weaker effect, but consideration of foreign brands as belonging to the out-group suggests low motivation to achieve harmony and a potentially stronger effect. Across all our studies, the desire for harmony seemed to outweigh the out-group distinction.

Whereas the individualism-collectivism dimension has been the subject of abundant research, comparatively little attention has been given to long-term orientation values. Time orientation was not even included in the original framework offered by Hofstede (1980), and empirical research incorporating this dimension has been relatively limited. However, this study’s findings suggest that it significantly influences how people respond and cope with their animus toward a foreign country. Particularly, the strong sense of national pride and need for cognitive consistency between attitudes and actions, reflective of a short-term orientation, help explain this relationship. This finding highlights the potential explanatory power of cultural values beyond the dominant individualism-collectivism dimension.

Given the different nature of the samples and the animosity contexts, we advise caution in directly comparing the US and Chinese experiments. However, the differences that do emerge are consistent with the rest of our findings. In the US, a highly individualist society, when we prime collectivist values, the effect of animosity on willingness to buy is reduced, but it is still statistically significant. In contrast, in China, a highly collectivist society, when we prime collectivist values and make it even more temporally accessible, the effect of animosity on willingness to buy is reduced so much that it is no longer statistically significant. This pattern of findings is also consistent for the long-term orientation experiments.

Our final contribution is methodological, highlighting the utility of combining societal-level data analysis along with individual-level experimental manipulations. The meta-analysis and experimental studies produced consistent evidence for the contrasting effect of animosity on willingness to buy and product judgments, as well as the moderating effects of collectivism and long-term orientation. However, the meta-regression analysis indicated a weak moderating effect of power distance; whereas, the power distance experiment produced estimates that were far from significant. The discrepancy on the moderating effect of power distance raises questions. We attribute the inconsistency between the meta-analysis and experiments to the correlation between power distance and collectivism at the societal level. In the meta-analysis, where both power distance and collectivism were significant, the correlation between the countries included in the sample resulted in groups with very similar member countries. Thus, the experiments serve an important function to isolate the true causal mechanism.

Current best practices suggest that multi-country studies should include at least seven countries to be able to draw reasonable conclusions (Franke & Richey Jr, 2010). However, even with a large number of countries, such as in the Study 1 meta-analysis, the possibility of intercorrelation among predictor variables remain, making it difficult to isolate the true relationship. The addition of an experimental approach priming cultural values at the individual-level of analysis can serve as a tool to help resolve such issues. In sum, combining analysis of both societal-level data and individual-level experimental manipulations may be a useful technique, especially in the case of correlated values in the data or with small numbers of countries.

Managerial Implications

Before discussing the implications for managers, we acknowledge that some consumers are “blissfully unengaged” in geopolitical events and have little knowledge and concern about products’ origin (Samiee et al., 2005), which means that the salience of country-brand associations vary across different consumer segments (Samiee, 1994). Nonetheless, evidence of significant economic damage to specific brands following animosity events is prevalent, suggesting that animosity does affect a significant amount of consumers. For example, Pandya and Venkatesan (2016) documented the damage to French brands in the US, following France’s decision to not support the Iraq war and Knight et al. (2009) documented the damage to the Danish brand Arla in Muslim countries, following a Danish newspapers publication of cartoons depicting the prophet Muhammad, or the negative effect of military conflict on cross-border acquisition value (Li, Arikan, Shenkar, & Arikan, 2019). Further, there is evidence to show that sometimes consumers are affected even by inaccurate country-brand associations Magnusson, Westjohn, and Zdravkovic (2011) or even when consumers deny using country-brand associations to evaluate brands (Herz & Diamantopoulos, 2017). Thus, the implications apply to those segments of consumers who implicitly or explicitly consider country-brand associations.

First, the aggregate evidence that animosity has limited effect on product judgments has important implications for brand tracking studies. Questions about perceived product quality may not reflect the influence of animosity and may over-estimate product potential. This suggests that when managers suspect that external animosity-causing events may potentially affect product sales, it may be important to capture consumers’ animosity levels and purchase intentions, not just product judgments.

This study found that cultural values influence how willing consumers are to act on their emotions, with more collectivist and long-term oriented consumers suppressing emotional responses. This suggests that if a brand finds its home country the target of animosity from one or multiple countries, understanding the cultural profiles of the countries holding animosity feelings can assist managers in assessing the degree of impact on purchase intentions, and may guide the allocation of resources to attempt to ameliorate those effects. Naturally, given that China and Japan are often considered the prototypical exemplars of countries where animosity has a strong influence on buying behaviors, it is clear that a collectivist and/or long-term oriented worldview does not always preclude consumers from acting on their emotions, they may just be less likely to do so.

Our findings of cross-cultural differences may also speak to the broader debate about international marketing standardization/adaptation (e.g., Katsikeas, Samiee, & Theodosiou, 2006; Westjohn & Magnusson, 2017). Given the cultural differences in how consumers act on their emotions, this should serve as additional caution about the effectiveness of an overly standardized, one-size-fits-all, global strategy.

Finally, how can managers mitigate the negative effects of animosity? First, it is important for managers to understand how strongly their brand is associated with its home country (or potentially another country). To mitigate the effect of animosity, one potential strategy may be to weaken the brand’s association with its home country and reposition it as a global brand. Evidence has found that French brands that were less closely connected with France suffered less from US consumer wrath (Pandya & Venkatesan, 2016) and Budweiser has attempted to position it as a global brand and reduced the brand’s association with the US in several markets where animosity toward the US has been strong.

The experimental studies may also suggest another viable strategic approach to mitigate animosity effects. Through priming, we made certain values temporarily accessible, which reduced the subjects’ willingness to act on their emotions; and research has shown that brand communication messages can activate different cultural values (e.g., Ma, Yang, & Mourali, 2014). This suggests that brands may employ promotion campaigns emphasizing collectivist and long-term orientation themes that have been shown in this research to weaken the effects of animosity. For example, brand communications may attempt to activate a more collectivist mindset by emphasizing language and themes that signify harmony and interdependence. One example is Coke’s well-known “buy the world a Coke” campaign in the early 1970s that included a jingle emphasizing hope and love with a large multicultural group of singers indicating interdependence and harmony. Alternatively, to activate more long-term oriented values, brand communications can emphasize language and themes that signify flexibility, pragmatism, and a focus on the future.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The multi-method nature of the study, and the consistent evidence across the meta-analysis and experiments from two different countries, provide confidence in the findings. Nonetheless, this study is subject to several limitations, which provide avenues for future research. First, any meta-analysis is constrained by the volume, nature, and scope of the original studies on which it is based. The volume of animosity studies is still somewhat limited, which have contributed to the rather large confidence intervals. After a period of time, new studies should be included in a meta-analysis, which may narrow the intervals, providing a more precise estimate of effect sizes.