Abstract

The emergence of digital platforms and ecosystems (DPE) as a venue for value creation and capture for multinational enterprises holds considerable implications for the theory and practice of international business. In this paper, we articulate these implications by considering the dual perspectives of cross-border platforms and ecosystems – as a venue for multifaceted innovation and as multisided marketplace – and focusing on three overarching themes at the intersection of DPEs and international business, that is, DPEs as affording new ways of internationalization, as facilitating new ways of building knowledge and relationships, and as enabling new ways of creating and delivering value to global customers. We explain specific DPE-related concepts and constructs that underlie these themes and discuss how they could be incorporated into existing IB theories in ways that would enhance their richness and continued relevance as well as their ability to better predict a multitude of emerging IB phenomena.

Resume

L’émergence des plates-formes et des écosystèmes numériques (PEN) en tant que lieu de création et de capture de valeur pour les entreprises multinationales a des implications considérables pour la théorie et la pratique en international business. Dans cet article, nous articulons ces implications en prenant en compte la double perspective des plates-formes et des écosystèmes transfrontaliers – en tant que lieu d’innovation multifacettes et en tant que marché multidimensionnel – et en nous concentrant sur trois thèmes majeurs à la croisée des PEN et de l’international business, à savoir : les PEN qui offrent de nouvelles approches d’internationalisation, qui facilitent le développement de connaissances et de relations, et qui permettent de nouvelles approches pour créer et fournir de la valeur aux consommateurs globaux. Nous expliquons les concepts et les construits spécifiques liés aux PEN qui sous-tendent ces thèmes et nous discutons de la manière dont ils pourraient être intégrés dans les théories de l’IB existantes de manière à améliorer leur richesse et leur pertinence continue, ainsi que leur capacité à mieux prédire une multitude de phénomènes émergents en IB.

Resumen

El surgimiento de las plataformas digitales y los ecosistemas (DPE) como lugar para la creación de valor y captura para las empresas multinacionales tiene implicaciones considerables para la teoría y la práctica de negocios internacionales. En este artículo, articulamos estas implicaciones al considerar las perspectivas duales de las plataformas y los ecosistemas transfronterizos -como un lugar para la innovación multifacética y un mercado de múltiples lados- y nos centramos en tres temas de alcance global y la intersección de las plataformas digitales y los ecosistemas y los negocios internacionales, es decir las plataformas digitales y los ecosistemas ofrecen nuevas formas de desarrollo de conocimiento y relaciones, y permiten nuevas formas de crear y entregar valor a los clientes globales. Explicamos los conceptos específicos de las plataformas digitales y los ecosistemas y los constructos que subyacen estos temas y discutimos cómo podrían incorporarse dentro de las teorías existentes de negocios internacionales de manera que aumenten su riqueza y relevancia continua, así como su habilidad para predecir mejor una multitud de fenómenos emergentes de negocios internacionales.

Resumo

O surgimento de plataformas digitais e ecossistemas (DPE) como um local para criação e captura de valor para empresas multinacionais tem implicações consideráveis para a teoria e a prática de negócios internacionais. Neste artigo, articulamos essas implicações considerando as perspectivas duais de plataformas e ecossistemas transfronteiriços – como um local para inovação multifacetada e como mercado multilateral – e focando em três temas abrangentes na interseção de DPEs e negócios internacionais, isto é, DPEs como proporcionadores de novas formas de internacionalização, facilitando novas formas de construção de conhecimento e relacionamentos e possibilitando novas formas de criar e entregar valor a clientes globais. Explicamos conceitos e construtos específicos relacionados às DPE que fundamentam esses temas e discutem como eles poderiam ser incorporados em teorias de IB existentes de forma a aumentar sua riqueza e continuada relevância, bem como sua capacidade de melhor prever uma multidão de fenômenos emergentes de IB.

摘要

数字平台和生态系统(DPE)作为跨国企业价值创造和捕获的场所的出现对国际商务的理论和实践带来了相当大的启示。在本文中, 我们通过考虑跨境平台和生态系统的双元视角来阐述这些启示 – 作为多面创新和多边市场的场所 – 并关注DPE与国际商务交叉的三个总体主题, 即DPE提供新的国际化方式, 促进建立知识和关系的新方法, 以及为全球客户创造和提供价值的新方法。我们解释了这些主题背后特定的与DPE相关的概念和结构,并讨论如何将它们纳入现有IB理论中,以增强其丰富性和持续相关性,以及更好地预测大量新兴IB现象的能力。

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

International business (IB) theories have long been based on assumptions of tangible flows of goods and services, restricted access to open resources, monetized transactions across national borders, and large organizations that compete in an environment full of physical barriers. For instance, the internalization theory (e.g., Buckley & Casson, 1976; Hennart, 1977, 1982a, b; Rugman, 1981; Rugman & Verbeke, 1992, 2001, 2003, 2004), built largely on transaction cost economics, has served as the theoretical foundation for much of the extant research on IB and has informed on a number of key issues relating to multinational enterprises (MNEs) including their location choice, entry mode, knowledge transfer, and organizational design. However, in recent years, some of the key assumptions that underlie this and other IB theories have come under increasing scrutiny. Specifically, the emergence of digital technologies and disruptive business models has begun to radically reshape the nature and structure of the global economy. Contemporary global business operations are increasingly characterized by intangible flows of data and information, greater availability of key open resources including technologies, heightened importance of digital infrastructure, instant worldwide access to knowledge and expertise, more exchanges of free content and services, and the growing role of small enterprises in economic activity and technology development. These changes make it necessary to reassess long-held assumptions about the global business environment and improve IB theories to better fit these emerging realities (e.g., Tallman, Luo, & Buckley, 2018; Casson, Porter, & Wadeson, 2016; Knight & Liesch, 2016).

In particular, the phenomenon of ‘platformization’ – the shift from individual products or services to platforms as the basis for offering value – and the emergence of associated ecosystems as a major venue for innovation, value creation, and delivery have considerable implications for IB and for the continued relevance of IB theories. Platforms constitute a shared set of technologies, components, services, architecture, and relationships that serve as a common foundation for diverse sets of actors to converge and create value (Gawer & Cusumano, 2002; Gawer, 2014). For example, Apple’s iOS platform provides a set of building blocks for hundreds of other firms to develop their own unique offerings that complement and enhance the value of the platform. Platform-based ecosystems then denote these sets of actors who are aligned to pursue a focal value proposition (Adner, 2017) and who exhibit varying types of mutual dependencies borne out of their co-specialization and complementarities in the platform context (Jacobides, Cennamo, & Gawer, 2018). This, in turn, also implies different roles for actors to play in the ecosystem (for example, orchestrator, integrator, complementor) – wherein the interdependencies tend to be standardized within each role (Jacobides et al., 2018) – and the consequent need for different types of skills, capabilities, and strategies (Autio & Thomas, 2014; Helfat & Raubitschek, 2018; Nambisan & Sawhney, 2011).

While examples of such platforms and ecosystems abound in the digital economy (e.g., Uber, Airbnb, Apple, Google, etc.), increasingly they are visible in the context of MNEs operating in traditional industries too – for example, automotive (e.g., Ford), energy and heavy industry (e.g., GE), industrial infrastructure and automation (e.g., Siemens, Johnson Controls), agriculture (e.g., John Deere), retail (e.g., Amazon, Wal-Mart), and home appliances (e.g., Nest). Indeed, many successful MNEs have created such digital platforms and ecosystems that their partners can use to interact, transact, innovate, and co-develop.

Digital platforms and ecosystems (DPEs) also transcend borders, locations, and industries.1 Collaborative interactions among ecosystem members reflect and reinforce these members’ co-specialization in different economic activities that are often situated in different countries and orchestrated by a central player (the platform leader). Buckley (2009, 2011) alluded to the above by the “global (virtual) factory” notion to characterize a business network in which an MNE may be a lead member in key or highly value added areas. Digital platforms enable cross-border as well as cross-sector collaboration opportunities with partners operating in varying industries, significantly extending an MNE’s nexus of network. These DPEs foster the availability and usage of open resources for all sizes of businesses, embracing many micro-MNEs that participate in global competition.

Further, to a considerable degree, the shift towards DPEs has been driven by the emergence of new digital infrastructures (e.g., Internet of Things, cloud computing, blockchain, big data analytics) and the infusion of digital technologies in products, services and processes (e.g., Nambisan, Lyytinen, Majchrzak, & Song, 2017; Porter & Heppelmann, 2015; Yoo, Henfridsson, & Lyytinen, 2010). The availability of ubiquitous digital infrastructures that underlie DPEs has radically restructured the nature, ways, processes, structure, as well as the cost of doing businesses internationally. Similarly, such digitization has led to less bounded outcomes and less predefined agency in innovation and entrepreneurship (Nambisan, 2017) that in turn imply more fluidity (or impermanence) in MNEs’ organizing for value creation across borders. These changes compel us to examine the implications of DPEs as a context for international business and consider how the related theoretical perspectives could be incorporated into existing IB theories to make them better reflect the contemporary global business environment.

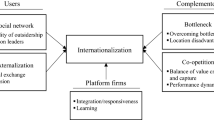

To develop our arguments, we consider the dual perspectives of DPEs – as a venue for multifaceted innovation and as multi-sided global marketplace – and suggest the significance of several underlying concepts (and related set of constructs) for international business. For example, DPEs embody a shared set of critical resources that redefines the nature of ownership advantages and the governance choices to deploy these resources for MNEs – specifically, ownership advantages at the level of the ecosystem and governance choices that de-emphasize location in preference to (industry) context. DPEs also embody new forms of connectivity among cross-border partners that in turn redefine the ways by which knowledge is sourced, transferred, transformed, and deployed, and the collective power that MNEs exercise outside of the ecosystem. Further, DPEs are characterized by modularity and loose ties that embody more fluid and flexible forms of resource recombination and deployment, that in turn facilitate innovative global business models and entrepreneurial initiatives. Therefore, a careful consideration of these concepts that underlie DPEs can inform on three broad themes or sets of implications for IB: new ways of internationalization; new ways of building knowledge and relationships; and new ways of creating and delivering value to global customers.2 We discuss each of these themes in detail and identify specific ways by which these DPE-related concepts/constructs could be incorporated into existing IB theories.

To be sure, we do not imply the insufficiency of existing IB theories. Rather, we believe the emergence of DPEs offers a new dynamic context for IB and makes it imperative that we reassess existing IB theories and delineate how, on the one hand, those IB theories can explain and accommodate the DPE phenomenon, and on the other hand, DPE concepts can enrich and augment them. Thus, our contribution here is twofold. First, we help to establish the relevance and significance of DPEs for IB scholarship by identifying some of the specific ways by which these platforms and ecosystems affect existing IB theories, such as OLI, internalization, internationalization process, dynamic capability, global knowledge, alliances, and international entrepreneurship. These perspectives espouse different assumptions about the sources of advantage in the marketplace. We propose that the emergence of DPEs is likely to change some of these assumptions in fundamental ways, suggesting new ways (and new risks) of competing. Second, we articulate promising avenues for future conceptual and empirical IB research to incorporate specific DPE-related constructs in ways that would enhance the richness and the continued relevance of IB theories and their ability to better predict a multitude of new and profound IB phenomena. Toward this end, in the sections that follow, we identify the implications of our arguments for IB theories and for research applying them.

CROSS BORDER PLATFORMS AND ECOSYSTEMS

Dual Perspectives of Platforms

Research on platforms (and associated ecosystems) has emerged from two distinct areas within the management literature – product development and industrial economics – and this has led to dual perspectives. The product development perspective (e.g., Gawer & Cusumano, 2002) has conceptualized platforms as a shared set of components, technologies, and other assets, arranged in modular architectures, that facilitate or serve as a venue for innovation. The industrial economics perspective (e.g., Rochet & Tirole, 2003, 2006) has conceptualized platforms as a set of rules and architectures that serve to connect two or more sets of entities and mediate interactions and transactions among them; i.e., as a multi-sided marketplace. Each of these perspectives underlines important issues and concepts that govern the management and operations of platforms and associated ecosystems, that in turn hold significant implications for international businesses (see Table 1).

From a product development perspective, an extensive set of studies on product design and development (e.g., McGrath, 1995; Robertson & Ulrich, 1998; Krishnan & Gupta, 2001; Meyer & Lehnerd, 1997) has established the notion of platforms as modular technological (or product) architectures that involve a stable, shared set of core components and a variable set of peripheral components. Such a modular architecture enables the re-use of shared resources (components or assets) that in turn leads to economies of scope in both production and innovation (Gawer, 2014). Modularity also facilitates innovation by reducing the interdependencies between modules to simplified interconnectivity rules articulated in terms of interfaces (Baldwin & Clark, 2000). By making such interfaces more open (West, 2007), platforms enable a broader set of entities with more heterogeneous knowledge and capabilities to participate in complementary innovation (Gawer & Cusumano, 2002).

The literature has identified two types of complementarity – unique complementarity that may involve some degree of co-specialization (Teece, 1986) and ‘Edgeworth’ or supermodular complementarity (e.g., Jacobides et al., 2018). For example, Apple’s iOS platform and Apps have both a unidirectional, unique complementarity (Apps require iOS to function) as well as Edgeworth complementarity (the greater the number of Apps available, the greater the value of the iOS platform). The nature of these complementarities defines the roles as well as the relationships (among the different sets of actors) that evolve in the associated ecosystem. The ecosystem that develops around the platform thus includes the platform leader, who defines the architecture of participation and orchestrates the innovation activities (Dhanaraj & Parkhe, 2006; Nambisan & Sawhney, 2011) and the complementary innovators, including customers (Lusch & Nambisan, 2015). All of these indicate the significance of platforms as a venue for innovation – one that embodies the potential for international businesses to enhance the value proposition of their core offering by seeking out and incorporating knowledge and expertise from diverse global partners as well as to customize the value proposition and business models to fit diverse international markets.

Studies that build on the industrial economics perspective have conceptualized platforms as multi-sided markets that are characterized by network effects that arise between different “sides” of the market (i.e., where one side’s benefits from participating in a platform depends on the size of the other side) (Armstrong, 2006). Such network effects can shape product pricing strategies and the nature of market competition. Network effects can be same-side (direct) or cross-side (indirect).3 Same-side network effects arise when the benefits to a user participating in a platform is based on the number of other users on the same side (Parker & Van Alstyne, 2005; Rochet & Tirole, 2003) and could be either positive (e.g., number of users on the Xbox gaming platform) or negative (e.g., job seekers on Monster.com). Cross-side network effects arise when the benefits to users belonging to one side (or group) of the platform are dependent on the size of the other side (number of users in another group) and could be unidirectional or bidirectional (e.g., number of buyers and sellers on eBay) (Hagiu & Wright, 2011).

Both same-side and cross-side network effects can give significant market advantage to an early entrant or incumbent (through a self-reinforcing cycle) that in turn could lead to a “winner-take-all” outcome (Eisenmann et al., 2006). The role of the platform leader involves establishing the ecosystem that constitutes the different user groups (or ‘sides’) and promoting regulated participation by making the best match among different parties for each interaction or transaction. Further, platform leaders can gradually enhance the scope (functionality) by leveraging their existing user base (and network effects) and move to adjacent markets – platform envelopment – to target new competitors (Eisenmann et al., 2011). All of these variables highlight the significance of platforms as a multi-sided marketplace (Table 1) – one that embodies the potential for international businesses to rapidly expand their overseas footprint by offering a consistent value proposition across borders and exploiting the associated network effects (both same-side and cross-side network effects) as well as by expanding into (or ‘enveloping’) adjacent (often foreign) markets. As such, DPEs hold considerable implications for international businesses, both established MNEs and new ventures.

Intersections Between Platforms and IB

As stated below, we suggest three key themes at the intersection of DPEs and IB: new ways of internationalization; new ways of building knowledge and relationships; and, new ways of creating and delivering value to global customers.

DPEs incorporate a shared and critical set of resources that could potentially redefine the nature of ownership advantages and governance choices to deploy those resources for MNEs – specifically, ownership advantages at the level of the ecosystem and governance choices that de-emphasize location in preference to (industry) context. For example, when viewed as a venue for innovation, platforms offer a common set of technologies, tools, components, and other assets that along with well-defined interfaces allow ecosystem members to minimize design and development redundancies and reduce both innovation costs and time (Iansiti & Levien, 2004). Similarly, as a multi-sided marketplace, platforms offer shared access to different sets of users and customers from various countries along with well-defined processes to govern interactions and transactions with them (Parker et al., 2016). The relationships with these users become a critical shared resource that could be redeployed by ecosystem members in different market contexts, generating surplus value.

The notion of innovation leverage (Iansiti & Levien, 2004) relates to sharing and reuse of such resources (e.g., technologies, processes, infrastructure, and intellectual assets) by ecosystem members and consequent generation of abnormal value (reflected in members’ enhanced innovation output or reduced innovation cost).4 Importantly, the extent of innovation leverage realized by ecosystem members would be shaped by both platform modularity and ecosystem openness (Nambisan & Sahwney, 2011). Thus, a focus on shared platform resources (and on the nature of their ownership and governance) implies the potential for MNEs to formulate novel ways or modes of international expansion.

DPEs embody new forms of connectivity among internationally diverse partners. In comparison with global cooperative alliances and networks, DPEs involve more diverse, loosely structured partners and more flexible forms. Structural, relational, and contractual interdependencies tend to be higher in alliances and networks than in DPEs. While both alliances and DPEs can generate competitive advantages arising from interconnections among partners, sharing of knowledge and risk, and exercise of collective power, the latter often allows more players of different kinds (e.g., customers) to cooperate more openly and flexibly without worrying about barriers and boundaries of distance, geography, and industry. Direct connections forged with worldwide customers allow MNEs to reduce their dependencies on foreign intermediaries and to co-create knowledge with customers (Lusch & Nambisan, 2015). Similarly, as a multi-sided marketplace, the connectivity with different ‘sides’ that underlie platforms allows platform leaders to benefit from collaborative advantages with their partners yet still dominate in control. Thus, a focus on the connectivity that underlies DPEs implies the potential for international businesses to formulate novel ways of building and utilizing knowledge and relationships. As discussed later, this has implications for several existing IB theories including the knowledge perspective of MNEs (e.g., Kogut & Zander, 1993; Inkpen, 1998) and the global alliance perspective (Contractor & Lorange, 1988).

DPEs are characterized by modularity and loose ties that embody more flexible forms of organizing for value creation and delivery. This allows for the emergence of innovative business models and entrepreneurial initiatives. For example, as a venue for innovation, platforms are designed to facilitate mix-and-match innovation (Garud & Kumaraswamy, 1995) through the rapid recombination of varied innovation assets, by minimizing the interdependencies among modules and making explicit the nature of their interconnectivity through open interfaces (Baldwin & Clark, 2000). As a multi-sided marketplace, platforms enable the mix-and-match of ‘sides’ (groups of users) and the rapid development of innovative business models to cater to emerging market needs. New digital infrastructures further enhance the capability of MNEs to engage in such fluid organizing (in terms of both structure and process) for innovation and entrepreneurship (Nambisan, 2017).

The innovation management literature has also emphasized network or ecosystem orchestration (Dhanaraj & Parkhe, 2006) as a critical capability that could shape the extent of such innovative and entrepreneurial initiatives among ecosystem members. Specifically, platform leader’s orchestration capability facilitates the management of innovation coherence – both internal coherence (among members’ activities) and external coherence (between platform goals and market context). Platform leaders who exercise superior orchestration capability would be able to promote a greater level of innovative and entrepreneurial initiatives in the ecosystem. Indeed, ecosystem orchestration can be viewed as a source of dynamic capability for MNEs (Teece, 2007, 2014). Thus, a focus on the flexibility that underlies DPEs implies the potential for MNEs to conceive new ways of creating and delivering value to global customers. This has implications for several existing IB theories, especially dynamic capabilities (e.g., Teece, 2014) and international entrepreneurship (e.g., Jones, Coviello & Tang, 2011).

Below, we examine each of the above three themes in detail and identify important avenues to augment existing IB theories (see Table 2). In articulating these implications for IB theories, we identify the important research issues that underlie each of the themes and suggest specific ways to incorporate DPE-related concepts and constructs in future IB research, ensuring their richness and continued relevance.

NEW WAYS OF INTERNATIONALIZATION

The above discussion suggests that DPEs engender new ways of international expansion with implications for a host of IB theories. These implications largely flow from the perspective of DPEs as shared resources that shape the decisions and actions related to internationalization. The concept of platforms as shared resource bundles that drive value creation and capture redefines ownership-specific advantages with implications for the OLI paradigm (Dunning, 1980, 1988) and internalization theory (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Hennart, 1977; Rugman, 1981; Rugman & Verbeke, 1992).

Specifically, DPEs imply the significance of ecosystem-specific advantages for MNEs – advantages that accrue from membership or participation in a platform-based ecosystem. Such ecosystem-specific advantages are often portable across borders (i.e., non-location bound) as they typically arise from the common or shared assets that constitute the particular platform, the complementary assets (contributed by ecosystem members) that enhance the value of the platform, as well as exclusive access to specific groups of actors (including customers). Ecosystem-specific advantages could also stem from shared intangible resources such as members’ reputation and brand recognition, members’ relational assets with external entities, and members’ prior experiences and intellectual assets. The leverage (surplus value) derived from reusing or redeploying such shared and non-location bound resources allow MNEs to gain internationalization advantages vis-à-vis its competitors outside the ecosystem.

With the emergence of DPEs, there is a shift in focus from inter-firm competition to inter-platform competition (competition among DPEs). Thus, an MNE’s success could increasingly be shaped by competitive moves that are based on such ecosystem-specific advantages that go beyond firm-specific advantages. Interestingly, prior studies on DPEs have shown that platform leaders may experience “scope creep” (Gawer & Cusumano, 2002) where the core platform functionalities expand over time to intrude into complementors’ space (i.e., incorporate functionalities offered by complementors). This raises the possibility that MNEs may seek ecosystem-specific advantages and then over a period of time, start internalizing them (or converting them into firm-specific advantages). This raises research issues on the dynamics between ecosystem-specific advantages and firm-specific advantages and how MNEs sharpen their distinctive (i.e., firm-specific) capabilities in participating in DPEs and leveraging ecosystem-specific advantages.

Viewed as shared resource bundles, DPEs also imply the increasing relevance of the business context – specifically, industry and market context – rather than national boundaries in examining global strategies – and, hence the need to consider context-specific advantages. Thus, differences in business contexts assume greater importance than differences between nations – and this, as Knight & Liesch (2016) recently noted, raises the need to delve on ‘intercontextual business’. For example, a platform-based MNE’s advantages are likely to be enhanced when the value proposition offered by the platform is consistent across national boundaries, which then would make entry to new foreign markets easier and faster. Such context-specific advantages may also accrue from the standardization of business processes, business models, and digital infrastructures across nations. In such situations, MNEs could easily port their context-specific advantages across national boundaries and pursue international expansion. For example, as the cases of Instagram and Airbnb illustrate, context-specific advantages in terms of the nature and size of the user base and associated network effects could enable MNEs to rapidly enter, scale, and grow their operations in foreign markets.

Thus, to the extent that MNEs employ DPEs as a vehicle for cross-border value creation, their internationalization decisions and processes may be shaped by ecosystem-specific advantages and context-specific advantages (in addition to firm-specific and country-specific advantages), as noted in Table 2. For example, these new ways of internationalization may have implications for the OLI paradigm such that MNEs need to rethink new location strategies and new locational determinants to co-locate with ecosystem players. More importantly, the interactions among these four types of advantages – firm-specific, ecosystem-specific, context-specific, and country-specific – could potentially give rise to novel patterns of capability building and novel resource recombination processes and critically shape mode of entry, scaling, and growth. Combining these advantages in fast-moving global environments is a critical entrepreneurial dynamic capability (Teece, 2014).

While DPE-related resources (and subsequent advantages) assume considerable importance in shaping MNEs’ pursuit of international opportunities, the emphasis is not necessarily on owning and controlling all the required resources but on organizing, synthesizing, and integrating all globally available resources. Thus, DPEs imply a shift in thinking from resource ownership to resource orchestration. For example, in contexts with high location advantages, MNEs could adopt more open platform architectures (wherein interfaces are in the public domain) to attract complementors in foreign countries who have location-specific knowledge assets. This also holds implications for extending the dynamic capability theory of IB. Specifically, a DPE itself is an open, evolving system; if orchestrated well, it can adapt, integrate, and reconfigure member firms’ resources and capabilities to match the requirements of a changing environment. This means that the availability of cross-border resources garnered through ecosystem members assume significance in shaping international expansion strategies. This line of thinking applies also well to asset orchestration (Helfat et al., 2007) and resource orchestration (Simron, Hitt, Ireland & Gilbert, 2011) to examine how MNEs can structure, bundle, and leverage resources in DPEs to fuel their international growth.

While global experience still matters in pursuing internationalization, traditionally defined incremental FDI experience is not necessarily a prerequisite. Thus, from the internationalization process theory (IPT) perspective (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; 1990; Vahlne & Johanson, 2017), DPEs enable young and inexperienced small firms to go international and become mini-MNEs. Digital platforms make resources more portable allowing for faster internationalization or transformation of young ventures into MNEs (Coviello, Kano &, Liesch, 2017). Further, DPEs reduce MNEs’ incremental commitment rationality because of the potential to share both risks and costs with other ecosystem members as well as the availability of open resources. From the OLI perspective, this also creates more “springboard” opportunities for nascent firms to go global (Luo & Tung, 2007, 2018) as DPEs become the vehicle to acquire critical resources to compete with international rivals (other platforms) and to reduce their newness-related or home-market vulnerabilities.

The resources that constitute DPEs (particularly ecosystem-specific advantages) also enable MNEs to adapt rapidly to changing market and industry contexts and as such hold implications for both knowledge-based view (e.g., Kogut & Zander, 1992, 1993, 1995) and global integration-local responsiveness (I-R) perspective (Birkinshaw & Morrison, 1995; Ghoshal & Bartlett, 1990; Roth & Morrison, 1990). DPEs involve both exploitative and explorative learning, but savvy MNEs will use their participation in DPEs as an adaptive and learning process that creates new knowledge and leads to the generation of a variety of products and services. Perhaps more important, this knowledge can fuel “strategic innovations” that redefine a firm’s identity, competitive approach, and role within the DPE. DPEs promote organizational learning in a world of globally diffused partners, underscoring the need for knowledge absorption and integration that lead to the definition of different opportunities, located in different markets around the world. From a global integration-local responsiveness view, DPEs imply the need to make the shift from a pure focus on parent–subsidiary links to a new context that extends broadly to a firm’s ecosystem. Thus, a DPE takes up some I-R functions for member firms. Vertical links in a DPE may integrate more primary value-chain functions while horizontal links can integrate more support activities. Further, greater adaptation or responsiveness is viable for MNEs that are able to creatively exploit and leverage ecosystem-specific advantages, and more generally, by relying on DPE resources.

DPEs also share the logic of global alliance and network perspective, yet bring a sharper focus on the platforms that underlie those alliances and networks. Indeed, a key to the success of MNEs is their ability to define and offer platforms that other members could use to create and deliver value in terms of their own offerings. As such, there is potential to enrich the global alliance perspective by incorporating concepts pertaining to platform leadership that in turn would help us understand how MNEs’ efforts in establishing a platform could lead to the success of their international alliances. This, for example, includes making critical decisions relating to the “essential” business problem that the platform will address and the incentives to attract complementors, the scope of the MNE’s operations vis-à-vis that of its partners in the ecosystem, the openness of the platform architecture and the types of complementarities to promote, and the balance between collaboration and competition with ecosystem members (Gawer & Cusumano, 2002, 2008).

DPEs reinforce Dyer and Singh’s relational view (1998) in that digital platforms can serve as a critical catalyst of inter-organizational competitive advantages through resource sharing. DPEs may also engender real option values due to their relational and contractual flexibility advantages (Chi & McGuire, 1996). That said, the notion of “relative scope” between competition and cooperation with the same network partners (see Khanna, Gulati & Nohria, 1998) applies to DPEs as well – simultaneous cooperation (and trust, fairness, social exchanges) and competition (and control, bargaining, and economic exchanges) occur within a DPE wherein ex ante design of platformization and ex post coordination is essential to the development of the DPE (Luo, Shenkar & Gurnani, 2008). Importantly, unlike alliances in which different partners may approach such design in a relatively balanced manner, DPEs involve platform leaders who play a central role throughout the process. DPEs are generally more structurally open and involve a greater variety of boundary-crossing players than alliances and networks. It is encouraged for future research to probe how such less structurally coupled systems work and what it takes to coordinate diverse members in a way that is different from coordination in global cooperative alliances and networks.

Finally, from an international entrepreneurship perspective, DPEs offer a novel context to study “accelerated internationalization” (Oviatt & McDougall, 2005; Shrader, Oviatt, & McDougall, 2000; Zahra, Ireland, & Hitt, 2000). Co-specialization provides opportunities for new firms to come into existence, survive, and grow. DPEs provide them with the infrastructure needed to instantly reach distant established markets and to capture value (Ceccagnoli et al. 2012; Huang et al., 2013). The existence of such specialized infrastructure also reduces the costs of conducting business, lowering the perceived risks of international expansion decisions. Similarly, ecosystem-specific and context-specific advantages discussed earlier could help new firms overcome liabilities of newness and foreignness in the markets they enter (Mudambi & Zahra, 2007; Zahra, 2005; Zahra et al., 2000), overcoming a major barrier to internationalization. Open platform architecture strategies may allow new firms to leverage the knowledge and capabilities from complementary partners and enter foreign markets with limited resources, offering them opportunities for further growth through market differentiation. Similarly, standardized digital infrastructures with “plug-and-play” capabilities allow new and small firms to put themselves in front of a vast built-in global customer base. Despite all these benefits, the study of new born companies has so far not accounted for the presence of DPEs and participation in these ecosystems (Cavusgil & Knight, 2015). Clearly, there is considerable potential for DPE-related concepts to contribute to our understanding of the formation and evolution of “born-globals” and to advance the literature on the accelerated internationalization perspective.

NEW WAYS OF BUILDING KNOWLEDGE AND RELATIONSHIPS

DPEs also create new ways or modes of building and utilizing knowledge and relationships with important implications for a host of IB theories. These implications largely flow from the perspective of DPEs as facilitating new forms of connectivity that shape MNEs’ decisions and actions related to knowledge and relationship building.

The knowledge-based view (e.g., Kogut & Zander, 1992, 1993) portrays the MNE primarily as an arbitrageur and combiner of knowledge derived from multiple sites and brought together in some centralized process. Similarly, the dynamic capability theory in IB (e.g., Teece, 2014) highlights the significance of knowledge reconfiguration and deployment in international markets as a means of continuous organizational adaptation. DPEs redefine the nature of MNEs’ connectivity with their diverse international partners, and thereby, the nature of such knowledge acquisition, recombination, and (re)configuration that occur in an expanded context and in a more interdependent manner. Specifically, DPEs involve multi-level social and economic processes through which knowledge is sourced, diffused and integrated across member firms, and between MNEs and their global customers. For example, DPEs involve complementors who possess specialized (co-specialized) knowledge about local markets (Gawer & Cusumano, 2002) that differentiate them from other members and help expand the realms of the platform’s value proposition.

The shared set of standards, processes, and governance systems that underlie DPEs also enable the rapid codification and integration of such local market knowledge (brought by complementors) with general market knowledge (already represented in the platform), accelerating MNEs’ foreign market learning, which is crucial for continuous innovation. Further, the nature of the architectural connectivity afforded by the platform will shape how frictionless such knowledge flows are as well as the ease with which knowledge recombination and reconfiguration may occur. Also, DPEs involve new forms of connectivity with diverse sets of global customers, allowing MNEs to embrace them as partners in innovation and value creation (Nambisan & Sawhney, 2007). For example, new digital infrastructures such as social media, online communities, and crowdsourcing systems enable MNEs to forego foreign intermediaries and establish direct connections with global customers. Interactions facilitated by such digital infrastructures form the locus of customer value co-creation (Ramaswamy & Ozcan, 2018) that allow for new modes of cross-border knowledge acquisition by MNEs.

Further, the diversity of partners and the knowledge acquired from DPEs also imply diversified paths for MNEs’ knowledge use and competence development. For example, while DPEs involve benefits from standardization and scale, MNEs also engage in customizing the local knowledge so acquired to specific markets and/or specific set of customers. This, in turn, aligns well with the I–R balance (Ghoshal & Bartlett, 1990; Roth & Morrison, 1990). Such balance enhances value creation through entrepreneurial exploitation of firm assets, resources, and capabilities. On the other hand, in other instances, MNEs may diffuse and generalize the insights derived from such local market knowledge in ways that facilitate their use by other members of the ecosystem – for example, by incorporating such market insights into the common platform (Gawer & Cusumano, 2002) or by making them available as shared knowledge assets that other members could leverage (Iansiti & Levien, 2004). Over time, this infusion of new knowledge can stimulate innovative and entrepreneurial activities that give member firms competitive advantages.

The connectivity enabled by DPEs helps MNEs to situate key knowledge and value creation activities closer to demand. This approach marks a departure from the traditional focus of MNEs on internalized control and the attendant lack of focus of IB theories on global customers and these customers’ role in value creation. Specifically, DPEs emphasize the promise of demand-side approaches (Priem, Li, & Carr, 2012) to guide MNEs’ knowledge acquisition and value creation strategies in the presence of high customer heterogeneity in global markets. Importantly, several DPE-related factors – for example, modularity and openness of the platform architecture, structural, and decisional openness of the ecosystem – could shape the acquisition and use of such knowledge obtained from partners and customers around the globe. Further, the very factors that enhance the ease of such knowledge acquisition and reconfiguration may also make MNEs and their businesses vulnerable to external uncertainties. Partners have incentives to protect their knowledge and not share it with others. These partners also innovate in idiosyncratic ways and different bases, complicating MNEs’ knowledge acquisition, integration, and recombination. This in turn emphasizes the significance of how well MNEs orchestrate their novel relationships with diverse international partners.

Beyond knowledge building, the connectivity enabled by DPEs also holds implications for managing relationships with a host of diverse partners. For example, while the global alliance theory addresses MNEs’ relationships with foreign partners, it emphasizes highly structured (or tightly coupled), bilateral relationships (Inkpen & Beamish, 1997). In contrast, DPEs constitute more open and/or loosely coupled and often fluid relationships among diverse partners, with members having varying (and dynamic) roles, positions, and incentives. Further, DPEs also mark a shift from bilateral to multilateral relationships; i.e., relationships that are not decomposable to an aggregation of bilateral interactions (Adner, 2017). MNEs are widely seen as entities functioning within larger networks of affiliated, but not internalized, firms, institutions, and activities. Collaboration at all stages of the value chain across organizational as well as national boundaries in a DPE setting has become an essential feature of global strategic management. An MNE may function as the leader or flagship of its network, but it must do so through communication and collaboration mechanisms rather than the command and control relationships of internalized hierarchy. The management of such multilateral relationships among diverse sets of partners is indeed a daunting undertaking, especially since governing complexity and attendant risks (e.g., interdependence risk, integration risk) increase as the ecosystem grows (Adner & Kapoor, 2010). In this context, ecosystem orchestration becomes a significant core competence for MNEs.5 Prior studies (e.g., Dhanaraj & Parkhe, 2006; Nambisan & Sawhney, 2011) have identified constituent elements of such ecosystem orchestration highlighting their underlying processes (e.g., knowledge mobility, innovation coherence) and their antecedents (e.g., member diversity, embeddedness, and openness). Incorporating such concepts/constructs into existing IB theories could critically inform on how MNEs may successfully orchestrate the complex web of relationships and interactions within a DPE so as to bring greater level of alignment among members and between their incentives and contributions. This alignment would enhance their performance and speed up their adaptation to changes in global environments.

It is worth noting that DPE structure makes virtual monitoring power critical. For example, new digital infrastructures such as blockchain technology can enhance the extent of information shared and processed by foreign partners while offering novel non-localized trust mechanisms, thereby reducing problems related to both bounded rationality and bounded reliability (Verbeke & Greidanus, 2009) in MNE interactions. While such new digital technologies help reduce the role of physical distance, distances in terms of the quality of digital infrastructures (and even technology standards) between countries (e.g., domestic and foreign) could arise and fortify location-based advantages. These changes have repercussions for widely held location-based views of FDI decisions.

From a relational perspective, DPEs also help extend the views and assumptions of existing IB theories in that these theories have largely explained individual MNE behavior, motives, and strategies. In contrast, DPEs make a focus on MNEs’ collective behavior imperative. This point was echoed by Buckley & Hashai (2004) who argued that the global system is the most important unit of analysis and that to focus on the individual firm only is to miss network connections. For example, DPEs place a greater emphasis on MNEs’ efforts to co-specialize, co-learn, and co-evolve with diverse partners. Such a focus on collective behavior would behoove IB theories to incorporate ideas and concepts that have been shown to shape collective decisions and actions. One issue that calls for future research attention relates to how DPE members may create a bigger pie (cross-border synergies) yet compete to divide it up.

Recent studies on global value chains and networks (e.g., Buckley, 2011; Buckley & Strange, 2015; Kano, 2018) have highlighted a focus on collective decisions and actions. However, the context of DPEs goes beyond such global value chain networks given the explicit presence of a platform that binds together more diverse actors in terms of types, sectors, origins, roles, and capabilities, creating a bigger network that comprises demand-side players (customers and users) in addition to supply-side actors. DPEs imply a focal value proposition and an alignment (mutual agreement) among ecosystem members regarding their positions, roles, and activity flows (Adner, 2017). This in turn brings a sharp focus on the shared worldview (Nambisan & Sawhney, 2011) and collective identity (Gawer & Phillips, 2013), which is true for alliances as well. Yet, DPE is an more open system that combines firm- and location-specific advantages at the collective level for all participants, further enabling the development of an ecosystem-wide identity as well as capabilities. DPEs also allow participating firms to share and reduce costs and risks in bolstering local responsiveness inducing efficiency and rapid adaptation. Further, DPE implies the need to consider cultural differences among members that could otherwise derail collective behavior promoted through shared digital infrastructures. Some of these cultural values could undermine the norms that encourage ecosystem-wide sharing, coordination and collective actions. Yet, these same cultural values could also be exploited to induce joint learning and collective action.

A consequence of such collective behavior in DPEs is the need for IB theories to focus on the competitiveness of DPEs and their diverse members. Increasing competition between different DPEs would redefine the scope of competition as well as the parameters of competition. For example, DPEs allow MNEs to exercise their collective power – i.e., the power derived from the web of ties in the ecosystem including their relationships with specific groups of actors or ‘sides’ – in competing with global rivals that belong in another DPE. However, the development and exercise of such collective power by MNEs and their partners will be predicated on several key DPE-related variables including the alignment of partner motives, cognitions, and contributions. Further, MNEs will need to manage tensions and conflicts among members in the same DPE, calling for diverse and even creative governance systems (e.g., contractual, relational, profit sharing, procedural justice, rules and standards). Resolving these tensions could create a vibrant ecosystem where members enjoy advantages from their collective actions while retaining their individual distinctiveness. DPEs are rich and ideal settings to investigate the processes and mechanisms of global co-opetition.

The novel forms of connectivity enabled by DPEs also hold other processual implications for MNEs that extend the internationalization process theory (IPT). Distance-, space-, and time-related monitoring costs for cross-border transactions decrease as a result of DPE-enabled connectivity, but it can engender new types of organizing costs associated with digital connectivity such as external shocks and information breaches. This new connectivity alerts ecosystem members to emerging opportunities and how to exploit them for an advantage quickly and jointly. Viewed as connectivity, DPEs imply new ways of knowledge and relationship building that involve new forms of foreign market knowledge acquisition (e.g., customer co-creation). Further, IPT emphasizes MNEs’ direct experiential experience, whereas DPEs recognize vicarious learning too. Shared learnings from diverse members’ experiences could promote system-wide innovation and spark entrepreneurial activities in the form of new products, countries, and business models. Path dependence, another major assumption behind IPT, may hold less significance for MNEs in a DPE context. Given the infusion of knowledge and other benefits from their DPEs, MNEs are able to adapt in ways that depart significantly from their traditional strategies. Further, DPEs create new types of MNEs (e.g., digital disrupters) who are lean, agile, aggressive, and cost advantageous. When organized effectively, platformization can facilitate value creation from architectural knowledge, combinative knowledge, and network knowledge in the process of internationalization.

Finally, from an international entrepreneurship (IE) perspective, entrepreneurs often benefit from their network relationships when internationalizing (Coviello & Munro, 1997; Oviatt & McDougall, 1994; Jones et al., 2011). DPEs connect geographically dispersed entrepreneurs, making their access to opportunities (e.g., resources, knowledge, technologies, and markets) and resource assembly easier. Further, digital infrastructures that underlie DPEs (including crowdsourcing and crowdfunding platforms) represent new forms of global connectivity that offer rapid access to two critical entrepreneurial resources – novel ideas (or expertise) and capital. Spurred by such DPE-based connectivity, startups are more likely to become “born globals” (Knight & Cavusgil, 1996). While DPE-based collective power exercised by MNEs could help international new ventures (specifically complementary service providers who want to internationalize their offerings), challenges abound for international entrepreneurs who often lack bargaining and controlling power in DPEs. They need to build strong co-opetition skills when dealing with powerful ecosystem partners. As such, DPEs represent a new context for IE research that has focused on co-opetition involving smaller firms and MNEs (e.g., Vapola, Tossavainen, & Gabrielsson, 2008; Coviello and Munro, 1997). Further, entrepreneurs participating in DPEs may need to play two potentially conflicting roles, that of a follower of the platform and as the leader of an independent firm (Nambisan & Baron, 2013, 2019), that in turn may shape their decision-making regarding international expansion. Clearly, DPEs imply both significant benefits as well as risks for new ventures and entrepreneurs aiming to leverage platforms for rapid internationalization.

NEW WAYS OF CREATING AND DELIVERING VALUE TO GLOBAL CUSTOMERS

DPEs stimulate new ways of creating and delivering value to global customers with important implications for several IB theories, particularly dynamic capabilities theory (Teece et al., 1997; Teece, 2014) and international entrepreneurship theory (e.g., Jones, Coviello & Tang, 2011; Oviatt & McDougall, 1994). These implications largely flow from the perspective of DPEs as affording new forms of flexibility – to be proactive, to learn, and to experiment – that shape MNEs’ innovative and entrepreneurial pursuits in the global arena. With this flexibility, as detailed below, DPEs imply new ways of dealing with global market turbulences, more fluid value propositions, greater impermanence in organizing for value creation across borders, new forms of opportunity recognition and pursuit, and novel avenues for early internationalization of new ventures.

As stated, DPEs denote a major shift in focus from individual products and services to platforms as the basis for offering value to customers. By their very structure, platforms provide a common basis for MNEs (and their ecosystem partners) to offer variants of the focal value proposition; i.e., platforms allow for greater levels of flexibility in refashioning value propositions and associated business models to cater to diverse and dynamic international markets (and customer segments). This is a reason why DPEs foster open innovation (Bogers et al., 2017; Nambisan, Siegel, & Kenney, 2018), enabling new partners to join (and current partners to exit) and in the process creating new avenues for developing innovative business models and delivering novel value propositions. This organizational churning process fuels entrepreneurial activities by promoting new venture creation and encouraging their expansion, often on an international scale (Zahra & Nambisan, 2011, 2012). Further, DPEs by definition are also boundary spanning (in terms of technologies, industries, and markets), expanding MNEs’ reach and capacity to serve diverse foreign customers simultaneously. All of these imply the flexibility afforded by DPEs and the consequent potential for MNEs to be more proactive and to continuously learn, experiment, and adapt to changing international markets.

With the above flexibility, it is instructive to focus on specific elements (or aspects) of DPEs to understand how MNEs can enjoy such flexibility in practice. The modular architecture of platforms facilitates the rapid configuration or recombination of services and value bundles to fit diverse international markets. Open interfaces also allow for ‘plug and play’ wherein complementors can customize their services to cater to specific local needs. Further, by leveraging common assets, partners can reduce their costs while enhancing the speed with which they respond to changing market conditions, allowing for rapid development and deployment of innovative value propositions. DPEs also enable MNEs to rapidly develop and deploy novel business models by adding new sets of partners, new ‘sides’ to multi-sided platforms, or by facilitating new types of interactions among existing ‘sides’. Similarly, DPEs enable MNEs to leverage their existing user relationships and expand the scope of their value propositions to target new international markets with minimal new investments (Eisenmann et al., 2011; Gawer, 2014). Further, the shifting patterns of collaboration and competition among complementors (or partners) (Iansiti & Levien, 2004), while a challenge for MNEs, could also be a source of their flexibility, as it allows for emergent opportunities to corral innovation agents based on their aligned incentives. In turn, this promotes MNEs’ willingness and ability to engage in new forms of business creation – alone or in collaboration with their partners.

In addition, digital technologies have led to less bounded innovation processes and outcomes and less predefined locus of entrepreneurial agency (Nambisan, 2017). For example, digitization allows for the scope, features, and value of offerings to continue to evolve even after they have been introduced to the market (Yoo et al., 2010). As noted, new digital infrastructures that underlie DPEs have led to less predefinition in the locus of innovation or entrepreneurial agency – ideas can percolate from anywhere in the platform-based ecosystem and could be pursued by a dynamic collection of partners with varied goals, motives, and capabilities. Thus, the flexibility afforded by digital technologies can translate into less permanence in MNEs’ organizing for value creation across borders.

While DPEs provide different forms of flexibility, whether an MNE realizes the potential flexibility offered in addressing global market turbulences will largely depend on its platform strategy, organizing competence, and entrepreneurial practices. This relates to the way in which an MNE approaches the alignment of its partners and secures its role in a competitive ecosystem. As such, it includes its approach towards envisioning the focal value proposition of the platform and identifying the gaps therein that could be pursued by partners, facilitating specific partner roles (and positions) in value creation and value capture, and continuously refashioning the alignment to fit the dynamic international business environment. Similarly, strategies founded on the demand-side approach (Priem et al., 2012) would help MNEs to rapidly sense changes in global customer preferences, i.e., to be more open to ‘opportunity signaling’. All of these, in turn, imply several avenues to extend dynamic capability theory and international entrepreneurship perspective. For example, it implies the importance of opportunity recognition in global markets, a topic that has received limited attention in IE research (Jones et al., 2011; Zahra, 2005); specifically, MNEs need to continuously seek opportunities to revitalize their platforms and to expand their scale and scope. These opportunities may require MNEs to invest in building and cultivating relationships within their ecosystem, and importantly, with their customers. These collaborative ventures may provide insights into newer opportunities in foreign markets.

The changes we described also highlight the significance of entrepreneurial practices (Teece, 2010) that would allow MNEs to rapidly discover and act on the potential alignment of foreign market opportunities and local partner capabilities by utilizing one or more sources of DPE flexibility identified earlier. DPEs extend this logic in important ways. First, DPEs incorporate both coupling and looseness, thereby propelling ambi-structuration of organizing international activities. Second, opportunities are often collectively constructed, i.e., created and shaped by multiple members of an ecosystem. While collective in their construction, individual firms may define and pursue opportunities differently, perpetuating variety within an ecosystem. Third, ecosystem members have an incentive to join others in exploiting opportunities; “going it alone” may cause firms to miss important market segments or fail to adapt in a timely fashion. Joining others in exploiting emerging opportunities reduces risk, enhances learning, and fuels different innovation. In turn, this expedites the birth of ‘born global’ enterprises.

DPEs offer important avenues for the early internationalization of MNEs and the birth of ‘born global’ new ventures that apply new business models, targeting cross-national market niches. DPEs allow for the sharing of existing international customers with large MNEs, introducing different and new business models in global competition for small and medium-sized firms (Tallman, Buckley & Luo, 2018). The infrastructure associated with DPEs also makes access to competitive feedback easier and less expensive, giving ‘born global’ firms important clues that could guide their decisions to position themselves and their products in international markets. This improves these companies’ learning advantages, which are crucial for rapid adaptation, assembly of resources, and building of capabilities (Zahra et al., 2000). Further, the flexibility offered by DPEs allows new ventures (including born globals) to simultaneously participate on multiple platforms – i.e., multihoming (Rochet & Tirole, 2003; Landsman & Stremersch, 2011) – and, thus manage their strategic dependency risks.

DARK SIDE OF PLATFORMS AND ECOSYSTEMS

As noted, DPEs offer promising opportunities for MNEs (and new firms) in their effort to expand their international footprint. However, they also imply varied types of costs and risks that future studies should include them in their research agendas.

The first set of risks relate to the dependencies inherent in platforms and ecosystems. DPEs can increase MNEs’ dependency on others, and thus become subject to more contagious effects from all risks facing them and facing others. While MNEs that assume the role of the platform leader may be able to decide their own goals and strategies for the most part, they are also increasingly likely to be vulnerable to the risks associated with their foreign partners – for example, innovation risks, reputational risks, operational risks, and legal risks. As complementary products and services are closely associated with the platform, any risks associated with their development, delivery, and/or performance would quickly be transmitted to the MNE. Further, in a platform-based network structure, external instabilities (e.g., natural disasters, power shortfalls, political instability, and social unrest) facing one international partner can make all other partners (including the MNE) equally vulnerable. The impact of such external shocks gets magnified in an interconnected world as the ripple effects spread even faster in a more digitized business environment. All of these imply the significance of DPE orchestration as a critical capability for MNEs to identify and to mitigate potential risks due to dependencies inherent in DPEs.

Another set of risks that future research should consider are associated with specific platform and ecosystem strategies adopted by MNEs. For example, platform openness (i.e., how open should the platform be) is an important strategic decision for MNEs to broaden the participation of partners across the world. However, open platforms may involve sharing proprietary technological assets with ecosystem members that in turn raise important risks associated with intellectual property (IP) rights. Such issues become more crucial when MNEs expand to countries with varying IP regimes and cultures. Openness may also involve more decentralization of decision-making in the ecosystem – decisional openness (Nambisan & Sawhney, 2011) – that could enhance member loyalty and quality of contribution. However, the effectiveness of such decisional openness may be dependent on the local or regional culture that platform members belong to; and, as the geographic diversity of DPE members increases, it would pose risks for MNEs orchestrating such efforts. Similarly, as witnessed in the case of Facebook, Amazon, and other platform companies, network effects may often lead to a winner-take-all economy that in turn raises important issues related to monopolistic competition and regulatory responses from government agencies in different countries. Thus, as these examples indicate, significant DPE-related positive returns or gains have consequent negative risks that also need to be considered when MNEs evaluate strategic moves.

An additional set of risks relate to the costs of market entry and exit when DPEs are involved. Establishing and maintaining a platform and orchestrating the associated ecosystem will require MNEs to make considerable upfront investments whose returns may not be evident in the short term. For example, building new organizational capabilities to champion a platform, embrace diverse foreign partners, and orchestrate DPE-related resources and activities would require significant time and effort on the part of MNEs. Similarly, it can be costly and difficult for MNEs to exit from long-term strategic relationships in a cross-national platform-based ecosystem. All of these imply the need for MNEs to incorporate a broader set of decision criteria when evaluating their foreign market entry/exit choices in DPE contexts.

An important aspect of international business operations involves selecting and developing the governance structures and functions of international firms and their component organizations and ecosystem partners, including organizational architecture, management systems, information sharing, and networking of subsidiary organizations.6 DPEs both amplify such connections and raise new challenges in managing such interdependence. Managing the internationally dispersed and often deeply integrated activities of global multi-business enterprises and multi-enterprise systems is a complex, evolving, but essential capability of such firms. Further, in harnessing DPE-induced gains, non-market strategies of pursuing corporate social responsibilities and working with critical stakeholders in host nations (or on an international basis) are also increasingly important to pursuing competitive advantage and reducing environmental and competitive risks for MNEs.

CONCLUSION

With the increasing significance of digital platforms and ecosystems comprising firms from a multitude of countries with a multitude of roles, we need to develop a deeper understanding of how they shape the behavior and performance of firms, large and small, operating internationally. In this article, we have articulated several important ways by which DPEs offer a dynamic business context that is likely to broaden our views about internationalization and related IB theories. Given the nature of this emerging landscape, it is natural to ask: How should we move research on DPEs forward from here? We believe our discussion suggests at least three promising pathways for future efforts.

The first set of research opportunities centers on developing new concepts and related constructs that would facilitate the adoption of the DPE lens in studies rooted in specific IB theories. For example, our discussion raised the potential significance of ecosystem-specific advantages and context-specific advantages in supplementing existing concepts in the OLI paradigm and internalization theory. While our focus here has been on indicating their significance, future research could consider further development of these and other concepts. DPEs have the potential to alter the nature and importance of ownership, location and internalization in fundamental ways suggesting a need to reexamine these issues in future IB research. Value creation in DPEs appears to be driven by a different set of logics and rules that can alter the contributions of the components of OLI and their interrelationships.

A second set of research opportunities relates to developing and validating new models that incorporate such DPE-related concepts and extend or enhance specific IB theories. Again, taking the example of internalization theory, new theories that postulate the combined (or interactive) effects of ecosystem-specific advantages, context-specific advantages, firm-specific advantages and country-specific advantages could potentially offer novel insights on MNEs’ mode of entry into foreign markets or their scaling and growth. Similar theory development efforts – related to other IB theories – could prove to be quite valuable in extending the reach of existing IB theories to platform markets. The rapidly growing base of empirical studies – employing both qualitative and quantitative approaches – implies the promise of validating such newly developed IB theories. For example, recent empirical work in the area of platforms and ecosystems (e.g., Parker & Van Alstyne, 2018; Zhu & Iansiti, 2012; Zhu & Liu, 2016) offers several avenues to operationalize DPE constructs such as platform openness, modularity, and network effects that could be usefully employed in IB research.

A third set of research opportunities relates to studying the important contingencies within the context of digital platforms and ecosystems. A number of exogenous forces – including market competition, institutional and cultural diversity, policies, and regulations (e.g., anti-trust law), and national/regional technological standards – might moderate (or otherwise shape) the role of platforms and ecosystems in internationalization efforts. Addressing these and other complex contingencies might require ambi-structuration of organizing international activities and imply interesting issues for future research. Platform leaders also need to know where, what, and when the bottlenecks that deter platformization are or will be. These bottlenecks can be technologies, key processes or hierarchies in the system, key nodal members or subsystems, and/or regulatory agencies.

The bountiful research opportunities we have identified above imply rich avenues for existing IB theories to accommodate the DPE phenomenon as well as for extending those IB theories by incorporating a range of DPE related concepts and insights. We hope the ideas presented in this article will advance future conceptual, theoretical, and empirical research in ways that enrich and sustain the relevance of IB theories in the ever-changing global marketplace.

NOTES

-

1

Platorms and ecosystems studied in this article (i.e., DPEs) refer specifically to those that are cross-border and digitally enabled. Note that not all platforms and ecosystems are necessarily global nor digital. For simplicity, we use the term ‘global’ in the title to connote the cross-border feature of the DPEs that we study.

-

2

We do not claim that these are the only IB-related topics or implications of DPEs. Rather, our analysis indicates that the three key DPE concepts – shared resources, connectivity, and flexibility – and their underlying mechanisms imply the relevance of the three themes discussed here.

-

3

Edgeworth (or supermodular) complementarity is the basis for both direct and indirect network effects (Jacobides et al., 2018).

-

4

Note that the term ‘leverage’ applies if the value generated by the shared innovation assets divided by the cost of creating, maintaining, and facilitating their sharing (and reuse) increases rapidly with the number of ecosystem members that use or deploy them, i.e., if the asset’s value curve increases with N (number of users) with an exponent that is larger than one (Iansiti & Levien, 2004).

-

5

Recently, Kano (2018) examined the role of such orchestration in the context of global value chain governance and highlighted social mechanisms that MNEs could deploy to enhance coordination and promote innovation with partners.

-

6

More broadly, DPEs enable MNEs to become global network-based cosmopolitan organizations. Within an MNE, global connectivity spurs intra-organizational sharing, orchestration, and integration for cross-border activities. Externally, MNEs build a nexus of network with ecosystem players – vertically (with foreign suppliers, distributors and customers), horizontally (with foreign competitors) or diagonally (with supporting service providers) – to cope with and to extract value from global connectivity.

REFERENCES

Adner, R. 2006. Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harvard Business Review, 84(4): 98.

Adner, R. 2017. Ecosystem as structure: an actionable construct for strategy. Journal of Management, 43(1): 39–58.

Adner, R., Chen, J., & Zhu, F. 2016. Frenemies in platform markets: The case of Apple’s iPad vs. Amazon’s Kindle. Harvard Business School Technology and Operations Mgt. Unit, Working Paper (15-087).

Adner, R., & Kapoor, R. 2010. Value creation in innovation ecosystems: How the structure of technological interdependence affects firm performance in new technology generations. Strategic Management Journal, 31(3): 306–333.

Armstrong, M. 2006. Competition in two-sided markets. RAND Journal of Economics, 37: 668–691.

Autio, E., & Thomas, L. 2014. Innovation ecosystems. In: The Oxford handbook of innovation management: 204–288. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baldwin, C. Y., & Clark, K. B. 2000. Design rules: The power of modularity (Vol. 1). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Birkinshaw, J. & Morrison, A. 1995. Configurations of strategy and structure in subsidiaries of multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(4): 729–753.

Bogers, M., Zobel, A. K., Afuah, A., Almirall, E., Brunswicker, S., Dahlander, L., et al. (2017). The open innovation research landscape: Established perspectives and emerging themes across different levels of analysis. Industry and Innovation, 24(1): 8–40.

Boudreau, K. 2010. Open platform strategies and innovation: Granting access vs. devolving control. Management Science, 56(10): 1849–1872.

Boudreau, K. J. 2012. Let a thousand flowers bloom? An early look at large numbers of software app developers and patterns of innovation. Organization Science, 23(5): 1409–1427.

Boudreau, K. J., & Jeppesen, L. B. 2015. Unpaid crowd complementors: The platform network effect mirage. Strategic Management Journal, 36(12): 1761–1777.

Buckley, P. 2009. Internalization thinking: From the multinational enterprise to the global factory. International Business Review, 18(3): 224–235.

Buckley, P. J. 2011. International integration and coordination in the global factory. Management International Review, 51(2): 269.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. C. 1976. The future of the multinational enterprise. London: Macmillan.

Buckley, P. J, & Hashai, N. 2004. A global system view of firm boundaries. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(1): 33–45.

Buckley, P. J., & Strange, R. 2015. The governance of the global factory: Location and control of world economic activity. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(2): 237–249.

Casadesus-Masanell, R., & Hałaburda, H. 2014. When does a platform create value by limiting choice? Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 23(2): 259–293.

Casadesus-Masanell, R., & Yoffie, D. B. 2007. Wintel: Cooperation and conflict. Management Science, 53(4): 584–598.

Casson, M., Porter, L., & Wadeson, N. (2016). Internalization theory: An unfinished agenda. International Business Review, 25(6): 1223–1234.

Cavusgil, S. T., & Knight, G. 2015. The born global firm: An entrepreneurial and capabilities perspective on early and rapid internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(1): 3–16.

Ceccagnoli, M., Forman, C., Huang, P., & Wu, D. J. 2012. Cocreation of value in a platform ecosystem: The case of enterprise software. MIS Quarterly, 36(1): 263–290.

Chi, T., & McGure, D. 1996. Collaborative ventures and value of learning: Integrating the transaction cost and strategic option perspectives on the choice of market entry modes. Journal of International Business Studies, 27: 285–307.

Contractor, F., & Lorange, P. 1988. Cooperative strategies in international business. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Coviello, N., Kano, L., & Liesch, P. W. 2017. Adapting the Uppsala model to a modern world: Macro-context and microfoundations. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(9): 1151–1164.

Coviello, N. E., & Munro, H. J. 1997. Network relationships and the internationalization process of small software firms. International Business Review 6(4): 361–386.

Dhanaraj, C., & Parkhe, A. 2006. Orchestrating innovation networks. Academy of Management Review, 31(3): 659–669.

Dunning, J. 1980. Toward an eclectic theory of international production: Some empirical tests. Journal of International Business Studies, 11(1): 9–31.

Dunning, J. 1988. The eclectic paradigm of international production: A restatement and some possible extensions. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(1): 1–31.

Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. 1998. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of inter-organizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4): 660–679.

Eisenmann, T., Parker, G., & Van Alstyne, M. 2006. Strategies for two-sided markets. Harvard Business Review 84(10): 92–101.

Eisenmann, T., Parker, G., & Van Alstyne, M. 2011. Platform envelopment. Strategic Management Journal. 32(12): 1270–1285.

Evans, D. S. 2003. Some empirical aspects of multi-sided platform industries. Review of Network Economics, 2(3): 191–209.

Evans D. S., & Schmalensee, R. 2008. Markets with Two-sided platforms, in ISSUES IN COMPETITION LAW AND POLICY 667 (ABA Section of Antitrust Law 2008).

Evans, D. S., & Schmalensee, R. 2013. The antitrust analysis of multi-sided platform businesses (No. w18783). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Evans, D. S., & Schmalensee, R. 2016. Matchmakers: The new economics of multisided platforms. Brighton: Harvard Business Review Press.

Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A. 1995. Technological and organizational designs to achieve economies of substitution. Strategic Management Journal, 16: 93–110.

Gawer, A. 2014. Bridging differing perspectives on technological platforms: Toward an integrative framework. Research Policy, 43(7): 1239–1249.