Abstract

Motivated by the international business literature that examines the interactions between political forces and business environments, we investigate whether and how political connections affect managers’ voluntary disclosure choices. We show that compared to non-connected firms, connected firms issue fewer management earnings forecasts. In addition, relative to non-connected firms, connected firms have a greater increase in the frequency of management forecasts subsequent to the elections that damage their political ties. Further analyses suggest that lack of capital market incentives, reduced litigation risk, and lower proprietary costs shape politically connected firms’ unique voluntary disclosure choices.

Résumé

Motivés par la littérature en international business qui examine les interactions entre les forces politiques et les environnements d’affaires, nous étudions si et comment les connexions politiques influencent les choix de divulgation volontaire des dirigeants. Nous montrons qu’en comparaison aux firmes non-connectées, les firmes connectées émettent moins de prévisions concernant la gestion des bénéfices. De plus, par rapport aux firmes non-connectées, les firmes connectées connaissent une plus forte augmentation de la fréquence des prévisions de gestion suite aux élections qui nuisent à leurs liens politiques. D’autres analyses suggèrent que le manque d’incitations du marché du capital réduit le risque de litiges, et que des coûts propres moins élevés façonnent les choix uniques de divulgation volontaire des firmes connectées politiquement.

Resumen

Motivados por la literatura de negocios internacionales que examina las interacciones en las fuerzas políticas y los entornos de negocio, investigamos si y cómo las conexiones políticas afectan las opciones de los gerentes a divulgar información voluntariamente. Mostramos qué comparado con las empresas no conectadas, las empresas conectadas emiten menos pronósticos de ganancias de la gestión. Adicionalmente, en relación con las empresas no conectadas, las empresas conectadas tienen mayor aumento en la frecuencia de los pronósticos de gestión empresarial posterior a las elecciones que dañan sus vínculos políticos. Otros análisis sugieren que la falta de incentivos en el mercado de capitales, reduce el riesgo de litigación, y los menores los costos de propiedad configuran las opciones únicas de divulgación voluntaria de las empresas conectadas políticamente.

Resumo

Motivados pela literatura de negócios internacionais que examina as interações entre forças políticas e ambientes de negócios, investigamos se e como as conexões políticas afetam as escolhas de divulgação voluntárias dos gerentes. Mostramos que, em comparação com empresas não conectadas, as empresas conectadas divulgam menos previsões gerenciais de resultados. Além disso, em relação às empresas não conectadas, as empresas conectadas têm um aumento maior na frequência de previsões gerenciais após eleições que prejudicam seus laços políticos. Análises adicionais sugerem que a falta de incentivos do mercado de capitais, o risco de litígio e custos de propriedade mais baixos definem as distintas escolhas de divulgação voluntárias de empresas politicamente conectadas.

摘要

受研究政治力量与商业环境之间相互作用的国际商务文献的激发,我们调查政治关联是否以及如何影响管理者的自愿披露选择。我们表明,与非关联企业相比,关联企业发布的管理收益预测较少。另外,相对于非关联企业而言,关联企业在有损它们之间政治关系的选举之后的管理预测的频率有较大幅度的增加。进一步的分析表明,资本市场激励的缺乏、诉讼风险的减少和专利成本的降低形成了政治关联企业独特的自愿披露选择。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Political connections are prevalent and economically significant in global markets (Faccio, 2006). An extensive cross-country literature suggests that high-level political connections are associated with various benefits and costs to firms and their shareholders.1 However, there is little evidence on how the benefits and costs associated with political connections affect a firm’s voluntary disclosure choices. Further, prior studies examining connected firms’ earnings quality and auditor choices yield mixed evidence on connected firms’ preference for transparency.2 In this study, we aim to shed light on politically connected firms’ preference for transparency by assessing the effect of political connections on the voluntary disclosure practice of firms around the world.

A global study on political connections and voluntary disclosures is timely and of great interest from the international business (IB) perspective. A growing number of studies in the IB literature focus on corporate transparency because it plays an important role in contractual agreements for multinational corporations (Jandik & Kali, 2009). In addition, the literature recognizes that corporate transparency improves investment efficiency and spurs growth, and that a firm’s disclosure choice is a function of country-level institutions (Cumming & Walz, 2010; Durnev, Errunza, & Molchanov, 2009; Shi, Magnan, & Kim, 2012). By taking advantage of the cross-country variation in capital market development and corruption, we provide evidence on the mechanisms through which political connections influence voluntary disclosure choices. Further, we establish causality of the relation by leveraging on multiple shocks to political connections across different countries.

We hypothesize that compared to non-connected firms, politically connected firms issue fewer voluntary disclosures because of their weaker capital market incentive and/or lower litigation risk. Disclosure theories suggest that firms are more likely to provide voluntary disclosure when they have greater capital market incentives and when they face higher litigation risk (Diamond & Verrecchia, 1991; Skinner, 1994). Compared to non-connected firms, however, connected firms have better access to credits and obtain privileged loans from banks that are influenced by politicians. As a result, connected firms have a lesser need to raise capital from the public and therefore have lower disclosure incentives to reduce the cost of capital. In addition, connected firms enjoy political protection and lower litigation risk and, consequently, have lower disclosure incentives to avoid lawsuits.

We note, however, that countervailing incentives may exist for connected firms to provide more voluntary disclosure in order to improve transparency or manage expectations. For example, theories suggest that firms are less likely to provide voluntary disclosure when they face higher propriety costs of disclosure. Connected firms are more likely to receive government contracts, which lowers the proprietary costs of disclosure because information revealed through voluntary disclosures does not deprive connected firms of their competitive advantage. Thus relative to non-connected firms, the lower proprietary costs increase the disclosure incentives of connected firms. In addition, politically connected firms are subject to more public scrutiny, which increases their incentives to improve information transparency (Guedhami, Pittman, & Saffar, 2014). Thus the relation between political connections and voluntary disclosure is an empirical question.

We use management earnings forecasts to capture voluntary disclosure because prior studies suggest that they lower the cost of capital (Coller & Yohn, 1997) and reduce litigation risk (Field, Lowry, & Shu, 2005). Management forecasts are also an important channel through which managers communicate additional information to market participants to reduce information uncertainty (Hirst, Koonce, & Venkataraman, 2008). While management forecasts have been examined extensively in the US, they are relatively unexplored in international markets. We follow recent studies (Li & Yang, 2016) and obtain worldwide management forecasts from Capital IQ. Following Chaney, Faccio, & Parsley (2011) and Guedhami et al. (2014), we capture high-level political connections using the data from Faccio (2006), who defines a firm as politically connected if at least one of its large shareholders and top directors is a member of parliament, a minister or the head of state, or is closely related to a top official.

Our treatment sample consists of 208 politically connected firms (547 politically connected firm-years) in 24 countries from 2002 to 2004.3 Because political connections are not random, we implement the two-stage regression procedure suggested by Heckman (1979) to control for the effect of self-selection. The control sample consists of 11,466 non-connected firms (28,006 non-connected firm-years) in the same 24 countries. Our selection model indicates that political connections are more prevalent among firms that are larger, more mature, and headquartered in a nation’s capital city. Connected firms are also more likely to be in an industry where a greater percentage of industry peers are connected and less likely to be in countries with stricter regulations limiting business activities of government officials. Importantly, after controlling for the self-selection effect, we find that connected firms are associated with less frequent management forecasts. The association is economically significant. For example, the average number of management forecasts issued by connected firms in a given year is 77.4 percent lower relative to forecasts issued by non-connected firms.

We perform various robustness checks for our main results. We find that the effect of political connections on management forecasts is greater among firms whose political ties are measured more objectively (i.e., where top shareholders and director serve as a member of parliament or a minister), relative to firms whose political ties are measured more subjectively (i.e., where top shareholders and directors have close relationships with a top official). Our results hold when we use alternative measures of voluntary disclosure, including a variable indicating whether a firm issues management forecasts and a variable measuring the frequency of conference calls during a fiscal year. Further, we find that our results are robust to including additional controls (i.e., state ownership, earnings quality, analyst forecast accuracy, and family ownership), using alternative samples, and employing alternative clustering methods for standard errors.

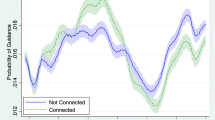

To further establish the causal link between political connections and management forecasts, we employ a difference-in-differences (DiD) research design that examines changes in the frequency of management forecasts for connected firms relative to the changes for non-connected firms subsequent to exogenous shocks to political ties. Using worldwide presidential and legislative elections between 2004 and 2010, we find that connected firms have a greater increase in the frequency of management forecasts subsequent to the elections that result in power turnovers, compared to non-connected firms in the same countries. This finding supports our inference that political connections cause less frequent management forecasts. In contrast, we find no change in the frequency of management forecasts for connected firms following the elections that do not result in power turnovers, suggesting that connected firms do not change their voluntary disclosure practices when their political ties remain intact after the election. We further mitigate potential concerns regarding our DiD estimation by showing that the increase in management forecasts materializes in the years subsequent to the power-turnover elections. In addition, there is no increasing or decreasing trend in management forecasts prior to these elections, suggesting that confounding effects such as increased economic or political uncertainty are unlikely to explain our results.

Next, we investigate the mechanisms through which political connections shape voluntary disclosure by performing analyses conditional on capital market incentives, litigation risk, and proprietary costs. If connected firms’ weak capital market incentives drive the negative relation between political connections and the level of management forecasts, we predict that this negative relation is more pronounced in countries with greater capital market development. In addition, if the lower litigation risk of connected firms drives the relation, we predict the negative relation to be greater in more litigious industries. In contrast, if the lower propriety costs of connected firms attenuate the negative relation, we predict the negative relation to be less pronounced for firms with greater industry-adjusted R&D, a proxy of firm-level proprietary information. Our analyses confirm these predictions.

A possible alternative explanation for the negative relation between political connections and voluntary disclosure is political rent extraction. Prior studies suggest that political rent seeking may motivate politically connected firms to maintain opaque information environment (Chaney et al., 2011). The rent extraction explanation implies that the negative relation between political connections and management earnings forecasts is more pronounced in countries with greater corruption. Inconsistent with the rent extraction explanation, we find that the negative relation is more pronounced in less corrupt countries.

Our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, by documenting disclosure practices of politically connected firms, we add to the IB literature that examines the interactions among political forces, corporate policies, and economic outcomes (Adhikari, Derashid, & Zhang, 2006; Boubakri, Mansi, & Saffar, 2013; Brockman, Rui, & Zou, 2013; Chen, Ding, & Kim, 2010; Claessens, Feijen, & Laeven, 2008; Faccio, 2006; Faccio, Masulis, & McConnell, 2006; Fan, Wong, & Zhang, 2007; Fisman, 2001; Habib & Zurawicki, 2002; Khwaja & Mian, 2005; Li, Meyer, Zhang, & Ding, 2017; Simon, 1984; Sojli & Tham, 2017). We provide the first evidence on whether and how political connections influence voluntary disclosure practices, which in turn shape firms’ information environment. Several recent studies have examined corporate reporting environments of politically connected firms by investigating accrual quality (Chaney et al., 2011), analyst forecast error (Chen et al., 2010), appointment of Big N auditors (Guedhami et al., 2014), and tax aggressiveness (Kim & Zhang, 2016). However, the findings of these studies are inconclusive and speak only indirectly to connected firms’ preference for information transparency.4 Our article provides direct evidence of politically connected firms’ preference for transparency by examining voluntary disclosure. We also shed lights on the channels through which political connections affect voluntary disclosure. Our results suggest that weaker capital market incentives and lower litigation risk reduce politically connected firms’ disclosure incentives. This finding adds to our understanding of how political forces shape global companies’ strategy for the communication with capital providers.

Second, we add to the burgeoning line of research in the IB literature on firms’ disclosure choice and behavior. Cumming & Walz (2010), for example, show that there are significant and systematic biases in managers’ reporting of fund performance around the world. Shi et al. (2012) document that the disclosure likelihood of firms cross-listed in the US varies with their home-country legal institutions. Akamah, Hope, & Thomas (2018) find that multinational firms with tax-haven operations exhibit distinct geographic disclosure behavior. By providing evidence on the relation between political connections and firms’ voluntary disclosure behavior, we answer to a recent call by the special issue of Journal of International Business Studies for more research on patterns in disclosure policy around the world (Cumming, Filatotchev, Knill, Senbet, & Reeb, 2015).

Third, our study extends recent studies that examine management forecasts worldwide (Li & Yang, 2016; Radhakrishnan, Tsang, & Yang, 2012) by documenting the effect of political connections on management forecasts in global markets. Our findings suggest a greater disclosure gap between connected and non-connected firms in countries with more developed markets and less corrupt institutions, thereby highlighting the interactive effect of firm-level political strategy and country-level institutions on management forecasts.

Finally, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to examine the effect of political events on firms’ voluntary disclosure practices in global markets. Our study extends prior single-country studies that document the impact of political events on financing strategies (Leuz & Oberholzer-Gee, 2006 for Indonesia), accounting choices (Ramanna & Roychowdury, 2010 for the US), and information environments (Piotroski, Wong, & Zhang, 2015 for China).

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The second section develops our hypothesis. The third section describes the variable measurement and research design. The fourth section presents our sample and descriptive statistics, and the fifth section reports empirical results. The sixth section discusses the key mechanisms and alternative explanations. The last section concludes.

Hypothesis Development

A long-standing literature shows that political connections add value to the connected firms. Fisman (2001) finds that at the time of Indonesian President Suharto’s worsening health, stock prices of firms closely connected with Suharto dropped more than the prices of less connected firms. In a cross-country study, Faccio (2006) finds that stock prices rise when officers or large shareholders of a firm enter politics. Studies also document that the benefits of political connections can take various forms including access to bank finance and lower cost of capital (Claessens et al., 2008), lower tax burdens (Adhikari et al., 2006), lax regulatory enforcement (Firth, Rui, & Wu, 2011), and receipt of government contracts and support (Faccio et al., 2006; Sojli & Tham, 2017). In addition, Boubakri et al. (2013) provide evidence that politically connected firms are more likely to undertake risky projects because they are insulated from bankruptcy in worse states of nature. An important implication from this literature is that political connections and political favors could affect firms’ preference for voluntary disclosure.

Disclosure theories suggest that capital market incentives and litigation risk influence a firm’s voluntary disclosure choice. First, firms have incentives to provide voluntary disclosures because greater disclosure reduces information asymmetry, which in turn, leads to a lower cost of capital (Diamond & Verrecchia, 1991). Empirical evidence is generally consistent with these theoretical predictions. Coller & Yohn (1997) find a reduction in bid-ask spreads, a proxy for information asymmetry, after the issuance of management earnings guidance. Prior studies also document a negative relationship between a firm’s level of voluntary disclosure and its cost of both debt (Sengupta, 1998) and equity capital (Botosan, 1997; Botosan & Plumlee 2002). Second, firms provide voluntary disclosure to mitigate litigation risk and accompanying costs (Skinner, 1994, 1997). Skinner (1994) and Billings & Cedergren (2015) argue that the asymmetric loss function for managers induced by the US legal system creates incentives for managers to disclose bad news quickly to reduce the probability of being sued and if sued, to reduce the settlement costs.

Compared to non-connected firms, however, connected firms have weaker capital market incentives for voluntary disclosure because the benefits of disclosure in reducing the cost of capital accrue less to politically connected firms. A firm’s need to access external financing affects the expected benefits of providing voluntary disclosure. Since politically connected firms have better access to credits and obtain privileged loans from banks that are influenced by politicians, they have a lesser need to raise capital from the public and therefore a lower incentive for voluntary disclosure. In addition, because of political favors that the connected firms enjoy, the cost of capital may be already relatively low for connected firms even without extensive information disclosure.

Politically connected firms also have weaker incentives to provide voluntary disclosure because they bear lower litigation costs. Politically connected firms tend to have more favorable regulatory treatment and lower litigation risk (Firth et al., 2011). Lower litigation risk implies weaker incentives for politically connected firms to issue timely disclosures that may help preempt lawsuits.

To the extent that political connections weaken the disclosure incentives that arise from capital markets pressure and litigation risk, we predict a negative relation between political connections and the level of voluntary disclosure. Our hypothesis, stated in the alternative form, is as follows:

Hypothesis:

Politically connected firms provide a lower level of voluntary disclosure compared to non-connected firms.

There are countervailing arguments for why politically connected firms may not provide a lower level of voluntary disclosure. Disclosure theories suggest that proprietary costs can explain why managers withhold information (Verrecchia, 1983). Compared to non-connected firms, politically connected firms are more likely to receive government contracts and support (Faccio et al., 2006). Because information revealed through voluntary disclosures does not deprive connected firms of their competitive advantage of receiving exclusive government contracts, politically connected firms may disclose more frequently than non-connected firms that bear proprietary costs of disclosures. That is, political connections can mitigate the disclosure disincentive associated with propriety costs. Politically connected firms may also have distinct incentives to provide voluntary disclosure to convince outside investors that they do not engage in self-dealing. In particular, connections to high-level politicians (i.e., members of parliament and ministers) are highly visible and subject to great public scrutiny.5 Because more reliable financial reporting and information disclosure help prevent expropriation by insiders and their political patrons, there is a stronger market demand for information transparency for politically connected firms (Watts & Zimmerman, 1983). Consistent with this reasoning, Guedhami et al. (2014) find that politically connected firms are more likely to appoint a Big N auditor.

Variable Measurement and Research Design

Measuring Political Connections

We obtain data on political connections from Faccio (2006), who developed a dataset of worldwide politically connected firms as of 2001. The data are commonly used in prior studies examining political connections in global markets (Chaney et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2010; Guedhami et al., 2014). According to Faccio (2006), a firm is classified as politically connected if at least one of its large shareholders (anyone directly or indirectly controlling at least 10 percent of votes) or top directors (CEO, chairman of the board, president, vice-president, or secretary) is a member of parliament, a minister or a head of state, or is closely related to a top official. We define an indicator variable, PC, which takes a value of one for connected firms, and zero otherwise.

It is worth noting that Faccio (2006) focuses on connections with high-profile politicians, and does not include connections via campaign contributions or state ownership. Campaign contributions are generally unobservable and difficult to identify in the global setting. In addition, the political ties documented in Faccio (2006) are likely to be more durable and thus provide a more powerful setting to detect the impact of political connections on firms’ disclosure policy.6 Faccio’s (2006) definition of political connections, however, may leave out firms that are classified as connected firms under alternative definitions, potentially leading to under-representation of certain countries in the sample.7

Measuring Voluntary Disclosure

We focus on management earnings forecasts to capture voluntary disclosure. Management earnings forecasts are an important form of voluntary disclosures that provide information about forthcoming earnings. These forecasts represent a key voluntary disclosure mechanism by which managers establish or alter market earnings expectations and influence the information environment of a firm (Pownall, Wasley, & Waymire, 1993; Hirst et al., 2008).

We obtain management forecasts from Standard & Poor’s Capital IQ, which collects worldwide corporate guidance information in text format starting in 2002. Capital IQ relies on public data sources including press releases and news wire articles, regulatory files, company websites, web agents, conference call transcripts, and investor conference organizer websites. While this database is relatively new to the literature, it has been increasingly used in recent studies examining management forecasts around the world (Li & Yang, 2016; Radhakrishnan et al., 2012).8 To extract information on management earnings forecasts, we conduct a keyword search for “earnings,” “Earnings,” or “EPS” in headlines and main texts under the “Corporate Guidance” event type from Capital IQ’s Key Developments Database. We do not differentiate annual versus quarterly earnings forecasts because our interest is on how political connections affect voluntary disclosure in general. Following prior studies (Li & Yang 2016), we treat multiple forecasts by the same firm on the same date as a single forecast.

Our measure of voluntary disclosure, the frequency of the disclosure (Freq), equals the natural logarithm of one plus the number of management forecasts issued in a given year. We focus on the extent to which managers provide earnings forecasts because the issuance of management forecasts is a first-order decision (Hirst et al., 2008).9

Research Design

Because political connections are not random and firms choose to make political connections (Faccio, 2006), we implement the Heckman (1979) two-stage regression procedure to control for the effect of self-selection in our analyses. In the first stage, we model the determinants of political connections by estimating a probit model in which the dependent variable is an indicator variable (PC) with a value of one for connected firms and zero for non-connected firms. The independent variables are the factors influencing firms’ decisions to establish political connections. In the second stage, we regress our voluntary disclosure measure, Freq, on the indicator, PC, and a set of control variables including the inverse Mills ratio (Lambda) estimated from the first-stage probit model.10

The first-stage probit model follows:

Equation (1) includes Capital and IndustryPC as exogenous variables (also known as “exclusion restrictions,” Lennox, Francis, & Wang, 2012). We reason that a firm’s location in the capital city and industry-level political connections are likely to influence a firm’s decision to establish its political connections, but are unlikely to directly affect its voluntary disclosure levels. Specifically, Capital is a variable indicating the location of a firm’s headquarters, which equals one if a firm’s corporate headquarters is located in the nation’s capital city, and zero otherwise. If a firm is located in the nation’s capital, it is much easier for the firm to make connections with high-profile politicians who work in the nation’s capital. The location of the firm would not have a direct effect on voluntary disclosure. In addition, a high level of political connections in the industry (IndustryPC) can motivate a firm to obtain political connections to defend its competitive position, but the industry-level political connection would not affect individual firms’ voluntary disclosure decisions without going through its effect on the individual firms’ political connections.

We also include the following firm-level and industry-level determinants of political connections based on prior literature (Chaney et al., 2011; Faccio, 2006; Guedhami et al., 2014; Hillman, Keim, & Schuler, 2004; Schuler, Rehbein, & Cramer, 2002): (1) firm size (Size), calculated as the natural logarithm of total assets in US dollars, because larger firms have greater resources and tend to be more politically active; (2) firm age (LnAge), measured as the natural logarithm of number of years since the IPO date, because older firms are more likely to have political connections; (3) free cash flows (FreeCash), measured as operating income before depreciation and amortization minus income taxes less changes in deferred taxes, interest expense, preferred dividends, and common dividends, deflated by total assets (Lehn & Poulsen, 1989), because firms with more free cash flows can afford to engage in political activities; and (4) industry concentration (Herf), measured as the Herfindahl index, because industry characteristics have been shown to correlate with a firm’s political activities.

In addition, we include the following country-level variables that are likely to correlate with political connections, as suggested in Faccio (2006) and La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny (1998): (1) corruption (ICRGCorrupt), measured as the International Country Risk Guide’s assessment of corruption in governments, because political connections and corruption tend to be complements; (2) openness (XborderRestrict), measured by whether there is any restriction on the purchase of foreign securities or outward direct investment by citizens, because capital restrictions ensure connected firms’ access to domestic capital; (3) regulatory environment (RegScore), measured as the regulatory score constructed in Faccio (2006), to capture regulations that prohibit or set limits on the business activities of public officials; (4) economic development (LnGDP), measured as the natural logarithm of GDP per capita in 2001; and (5) three legal origin indicators (German, French, and Scandinavian), to capture the German, French, and Scandinavian civil-law traditions.11 Finally, we include year fixed effects. Appendix provides detailed definitions of the variables.

The second-stage regression model follows:

We estimate an OLS model with our voluntary disclosure variable, Freq, as the dependent variable.12 Our variable of interest is the political connection indicator, PC. A negative (positive) coefficient on PC indicates that politically connected firms have a lower (higher) level of management forecasts than non-connected firms. Following Chaney et al. (2011), we cluster standard errors at the country-industry level throughout our analyses.13

We control for various factors that prior literature identifies to affect firms’ voluntary disclosure choices (Chen, Chen, & Cheng, 2008; Li & Yang, 2016). Our control variables include (1) firm size (Size), defined as the natural logarithm of total assets in US dollars, (2) return on assets (ROA), defined as net income deflated by total assets, (3) market-to-book ratio (MTB), calculated as market capitalization divided by book value of equity, (4) leverage (LEV), calculated as the long-term debt deflated by total assets, (5) earnings volatility (EarnVol), calculated as the standard deviation of earnings over assets for the past 5 years,14 (6) return volatility (RetVol), calculated as the standard deviation of annual stock returns over the past 5 years, (7) the number of analyst following (NAnalyst), (8) an indicator variable that equals one if a firm experiences a negative earnings change in the year (BadNews), (9) a variable indicating equity issuance in the subsequent year (EquityIssue), defined as a dummy variable equal to one if a firm’s total number of common shares outstanding after adjusting for stock splits and dividends increases by 20 percent or more in the next year, (10) a variable indicating whether a firm is cross-listed in the US (Cross), (11) an indicator variable that equals one for Big N auditors (BigN), (12) an indicator variable that equals one for the use of International Accounting Standards (IAS),15 and (13) a measure of a firm’s ownership structure (Closeheld), defined as the number of closely held shares divided by total shares outstanding. We also include year, industry, and country fixed effects to control for the variation of management forecasts across different years, industries, and countries. Throughout our analyses, we winsorize all scaled variables, including ROA, MTB, LEV, EarnVol, RetVol, and Closeheld, at the top and bottom 1 percent of their distribution to mitigate the influence of outliers.

Sample and Descriptive Statistics

Sample

We start with a list of 541 politically connected firms from 34 countries in 1997–2001 as identified in Faccio (2006). Based on Compustat (Global and North America), we construct a sample of non-connected control firms in these 34 countries over the same period. We obtain data on management earnings forecasts from Capital IQ. Since complete corporate guidance information in Capital IQ starts from 2002, we restrict our sample period to 2002–2004, by which we assume that the political connections established in 1997–2001 continue to hold in the subsequent 3 years.16 We exclude companies in Japan because their management forecasts are mandated (Kato, Skinner, & Kunimura, 2009).17 The forecast frequency of firms with missing guidance information from Capital IQ is set to zero. After requiring financial data to be available in Compustat and Worldscope, our final sample consists of 547 (28,006) firm-year observations representing 208 (11,466) politically connected (non-connected) firms in 24 countries from 2002 to 2004. The number of connected firms in our sample is similar to that in prior studies such as Chaney et al. (2011).18

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1, Panel A reports the sample distribution by country. It indicates a wide cross-country variation in both the connected and non-connected firms. For example, firms from the UK and Malaysia dominate the politically connected sample, accounting for 32 percent and 26 percent of all connected firm-year observations, respectively; while the rest of the countries each represent less than 7 percent of the connected firms. This pattern is consistent with prior studies such as Chaney et al. (2011) and Guedhami et al. (2014). Among the non-connected control firms, the US has the largest number of observations (12,893) and Hungary has the smallest (34).19 Panel B reports the sample distribution by year. We observe a steady increase in the number of observations over the three sample years.

Panel C of Table 1 presents the average number of management forecasts and the institutional characteristics of our sample countries. The average number of management forecasts (NForecast) varies significantly across the countries, ranging from 0.91 in the US to zero in Mexico. Nine out of our 24 sample countries have at least one restriction on cross-border capital flows (XborderRestrict). Philippines has the highest regulatory score (RegScore), indicating the most stringent regulatory environment that prohibits or sets limits on the business activities of public officials, while six countries have no such regulations (i.e., Belgium, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, and Taiwan). In addition, Switzerland has the highest GDP per capita (LnGDP) in 2001 while India has the lowest. As for the legal origin (Legal Origin), eleven, six, five, and two of our sample countries have English, German, French, and Scandinavian legal origin, respectively. US has the highest market efficiency score, followed by Hong Kong, and Mexico has the lowest score. Based on the ICRG corruption index (ICRGCorrupt), Philippines is the most corrupt country with the highest score in our sample and Canada, Finland, Sweden, and Switzerland are the least corrupt countries with the lowest score. Based on the German corruption index, on the other hand, Indonesia and Thailand have the highest value of five in our sample and 14 countries have the lowest value of zero.

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics across connected and non-connected firms. We find that for connected firms, the average number of management earnings forecasts issued over a year is 0.25, significantly lower than the number for non-connected firms (0.47). In comparison to non-connected firms, connected firms, on average, are more likely to have their headquarters located in the nation’s capital city (Capital) and are in an industry with more connected peer firms (IndustryPC). In addition, connected firms are larger (Size) and older (LnAge), have more free cash flows (FreeCash), and are in an industry with less competition (Herf). They also are more leveraged (LEV), less likely to issue equity in the subsequent year (EquityIssue), more likely to cross-list in the US (Cross), more likely to use a Big N auditor (BigN), and more likely to adopt International Accounting Standards (IAS), as well as having better accounting performance (ROA), less volatile earnings and returns (EarnVol and RetVol), greater analyst coverage (NAnalyst), and more closely held shares (Closeheld). These differences are generally consistent with prior research (Chen et al., 2010; Guedhami et al., 2014).

Empirical Analyses

The Effect of Political Connections on Voluntary Disclosure

Table 3 reports the Heckman two-stage regression results of the effect of political connections on voluntary disclosure after controlling for other potential determinants of disclosure. For brevity, we suppress reporting of the coefficients on fixed effects in this and all subsequent tables.

Column (1) of Table 3 reports the results of the first-stage probit model. As in prior studies (Chaney et al., 2011; Hillman et al., 2004; Schuler et al., 2002), we find that firms are more likely to be politically connected when their headquarters are located in a nation’s capital city, or when there is a greater percentage of industry peers that are politically connected. We also find that political connections are more prevalent in larger and more mature firms, consistent with the findings in Hillman et al. (2004). On the other hand, there are fewer politically connected firms in more concentrated industries, which is inconsistent with the prediction from prior studies. In addition, consistent with Faccio (2006), political connections are less common in countries with stricter regulations limiting business activities of government officials. Finally, political connections are less prevalent in countries with German legal origin.

Column (2) of Table 3 presents the results of the second-stage OLS regression. We find that the coefficient on the political connection indicator, PC, is negative and significant at the 0.01 level.20 To gage the economic significance of the result, we take the exponential value of the coefficient on PC and then subtract one. We find that the average number of management forecasts issued by connected firms in a given year is 77.4 percent lower relative to forecasts issued by non-connected firms.21 Thus the effect of political connections on the frequency of management forecasts is economically significant. Column (2) shows that several control variables are significant at the 0.10 level or better. Specifically, the frequency of management forecasts increases in firm size, return on assets, market-to-book ratio, earnings volatility, and analyst coverage, and decreases in leverage and the percentage of closely held shares. These findings are generally consistent with prior studies such as Chen et al. (2008). Finally, the coefficient on Lambda is significantly positive at the 0.01 level, indicating a significant self-selection effect in our sample.22 In summary, the results in Table 3 suggest that relative to non-connected firms, politically connected firms provide less voluntary disclosure.

Sensitivity Tests

In this section, we conduct several robustness checks of our results in Table 3 by examining different types of political connections, considering state ownership as an alternative form of political connections, using an alternative measure of voluntary disclosure, adding additional control variables, using an alternative sample, and adopting alternative schemes of clustering standard errors. Panel A of Table 4 reports the tests for alternative definitions of key variables and additional control variables. Panel B of Table 4 reports the tests with alternative samples and adjustment to standard errors. We summarize the results of these robustness checks below.

Examining Different Types of Political Connections

Faccio (2006) suggests that compared to connections with a minister or members of parliament (GovParli), close relations with top officials (Relation) are more ambiguous and less objective because the necessity of relying on publicly available sources for information on close relationships produces an incomplete picture. We investigate whether the impact of political connections on voluntary disclosure varies across different connection types. Column (1) of Table 4, Panel A shows that, consistent with Faccio (2006), the effect of political connections on management earnings forecasts is greater among firms whose political ties are more objectively measured. The difference of the effect of GovParli versus Relation is significant at the 0.05 level.

Considering State Ownership

Following Faccio (2006), we capture political connections as the personal ties between high-level politicians (i.e., a head of state, a minister, or a member of parliament) and corporate insiders (i.e., large shareholders or top directors). State ownership is not considered as political ties in this study. Nevertheless, state ownership may constitute another form of political connection and can be associated with both political connections and a firm’s voluntary disclosure practice. We collect the information on state ownership based on Claessens, Djankov, & Lang (2000) and Faccio & Lang (2002) and re-define PC as a dummy variable, PCplus, equal to one if a firm is politically connected as in Faccio (2006) or has state-controlled ownership. We rerun our analysis in Table 3 and find consistent results as reported in column (2) of Table 4, Panel A. In column (3), we include state ownership as an additional control variable in our regression analysis, and find that our results are qualitatively identical to those reported in Table 3.23 In addition, we find that the coefficient on PC is more negative than the coefficient on State (significant at the 0.01 level), suggesting that the effect of high-level political connections on voluntary disclosure is greater than the effect of state ownership. In sum, our findings are robust to controlling for state ownership.

Issuance of Management Forecasts as an Alternative Measure of Voluntary Disclosure

We assess whether our results extend to the decision to issue management forecasts rather than disclosure intensity as measured by forecast frequency. We replace the frequency of forecasts (NForecast) with a variable indicating whether a company issues at least one forecast during the fiscal year. We estimate a probit model and report the results in column (4) of Table 4, Panel A. We find that our results are qualitatively identical to those reported in Table 3.

Conference Calls as an Alternative Measure of Voluntary Disclosure

Conference calls are another channel through which managers communicate their private information on firm performance (Bushee, Matsumoto, & Miller, 2003). We assess the robustness of our results by using conference calls as an alternative measure of voluntary disclosure. While management forecasts provide forward-looking information, conference calls provide context, clarity, and greater details about the recent earnings number. To the extent that both management forecasts and conference calls improve transparency, however, the effect of political connection on these two different types of disclosures should be similar. We obtain information on conference calls from Capital IQ and rerun our analysis in Tables 3 by replacing the frequency of management forecasts with that of conference calls. Our sample for the analysis of conference calls is identical to the sample in Table 1, except that we now include 6,576 observations from Japan (69 connected observations representing 27 unique firms and 6,507 non-connected observations representing 2,586 unique firms).24 In untabulated univariate analysis, we find that the average frequency of conference calls for connected firms in a year (0.039) is significantly lower than that for non-connected firms (0.173). Column (5) of Table 4, Panel A reports the regression result. The coefficient on PC is negative and significant at the 0.01 level, suggesting that connected firms hold less frequent conference calls. Thus our findings are robust to using conference calls as an alternative measure of voluntary disclosure.

Controlling for Additional Variables

While we control for an extensive set of variables in Eq. (2), our results could still be subject to the bias of correlated omitted variables. Prior studies find that connected firms have lower financial reporting quality and greater analyst forecast errors (Chaney et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2010). Thus we further control for two variables: (1) a proxy for earnings quality (EarnQuality), calculated as the standard deviation of 5-year performance-matched discretionary current accruals, and (2) a proxy for analyst forecast accuracy (FError), measured by the absolute value of the difference between the last consensus analyst forecast prior to the earnings announcement and actual earnings, deflated by stock price at the beginning of the year. We also include an indicator variable for family ownership as in Chaney et al. (2011). We then re-estimate Eq. (2) after adding these three additional control variables. The number of observations is substantially smaller in this test due to data restrictions in calculating the additional variables. Column (6) of Table 4, Panel A finds that, despite the much smaller number of observations, our results are qualitatively identical to those reported in Table 3. Thus our findings are robust to including additional controls for earnings quality, analyst forecast accuracy, and family ownership.

Using a matched sample

The sample distribution in Table 1 shows a much larger number of control firms than the number of connected firms. While using the full sample helps ensure adequate sample sizes in our partitioning analyses and additional tests, we test the robustness of our results to alternative sample compositions by constructing a one-to-all, by-year, by-country, and by-industry matched control sample following Chen et al. (2010).25 While we already control for year, industry, and country fixed effects in all our regressions, matching of connected and non-connected firms in these dimensions helps ensure that our results are not driven by year, industry, and country-specific factors. Column (1) of Table 4, Panel B finds that our results are qualitatively identical to those reported in Table 3, even though the number of observations is substantially reduced.

Excluding preliminary earnings announcements

Companies often provide earnings forecasts after the end of the reporting period but before the release of the final earnings numbers. These earnings forecasts are termed as “preliminary earnings announcements” and motivations for issuing such forecasts are potentially different from those of other forecasts issued earlier in the year (Hirst et al., 2008). We assess the sensitivity of our results by excluding management forecasts issued between the fiscal yearend and the date of earnings announcement. Column (2) of Table 4, Panel B finds that our results are qualitatively identical to those reported in Table 3. Thus our findings are robust to excluding preliminary earnings announcements.

Addressing Capital IQ coverage issues

Radhakrishnan et al. (2012) suggest that Capital IQ expands its coverage over time and the coverage is likely to be more complete after 2004. To address the potential concern of incomplete coverage in our sample period, we first re-estimate Eq. (2) by limiting our sample to firms with analyst following, assuming that firms that are followed by analysts are likely to be covered by Capital IQ even in earlier years. The results reported in column (3) in Table 4, Panel B are qualitatively identical to those reported in Table 3. In untabulated analysis, we also find that our results are robust to limiting the sample period to 2004. Thus our findings are robust to addressing the potential coverage issues with Capital IQ.

Dropping influential countries

Table 1 indicates that the UK, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Singapore are the five countries with the largest number of connected firms in our sample. To assess the sensitivity of our results to the influential countries, we drop these five countries all together. The results reported in column (4) of Table 4, Panel B are qualitatively identical to those reported in Table 3. In untabulated analysis, we also drop these five countries one at a time and find consistent results. Thus our findings are robust to excluding influential countries. In addition, as US firms take up a large proportion of the control sample, we exclude them from our analysis and find the results (untabulated) qualitatively identical to those reported in Table 3.

Using alternative clustering schemes

Following Chaney et al. (2011), we cluster the standard errors in all our regressions at the country-industry level to control for common but unobservable characteristics shared by observations within the same country-industry group.26 To assess the sensitivity of our results, we employ the following alternative clustering schemes: (1) two-way clustering by firm and year, (2) two-way clustering by firm and country-year. As shown in columns (5) and (6) of Table 4, Panel B, our results are qualitatively identical to those reported in Table 3. Thus our findings are robust to alternative standard error clustering schemes.

Performing analysis by year

Our sample period spans over 2002–2004. We conduct Fama–MacBeth regressions and find robust results as reported in column (7) of Table 4, Panel B. In untabulated analysis, we also rerun our analysis by year and find qualitatively identical results for each year as those reported in Table 3. Thus our findings are robust across all sample years.

Changes in Management Forecasts Following Elections Worldwide

Our analyses so far use the Heckman two-stage regression procedure to control for the effect of self-selection. In this section, we further mitigate the concern of endogeneity by adopting an alternative design using a DiD approach. Specifically, we examine the change in management forecasts for connected firms subsequent to political events that damage their political ties. If political connections are indeed the reason for a lower level of management forecasts, we expect connected firms to increase voluntary disclosure subsequent to these events, that is, when their political ties are broken. As a falsification test, we also examine changes in management forecasts around political events that do not affect the existing power structure and expect no changes for connected firms following these events. To implement these tests, we compare changes in the number of management forecasts issued by connected firms 2 years before and after the elections, relative to the corresponding changes in the number of forecasts issued by non-connected firms in the same country over the same period. This DiD design helps isolate the effect of elections from other factors potentially affecting voluntary disclosure.

To capture political events that damage the political ties of connected firms, we use elections that result in power turnovers. We utilize the World Bank Database of Political Institutions (Beck, Clarke, Groff, Keefer, & Walsh, 2001), which collects information on worldwide presidential and legislative elections from 1975 to 2012. We define elections with power turnovers as those electing a new president in countries with presidential systems (e.g., Taiwan and the US) or a new parliament under the leadership of a different party in countries with parliamentary systems (e.g., Austria and Canada). Similarly, elections without power turnovers (i.e., political events that do not damage the political ties of connected firms) are those that re-elect the incumbent presidents in countries with presidential systems or the same party in countries with parliamentary systems. Since political connections reflect ties with the existing head of state or members of parliament, elections that result in turnover of the incumbent president and ruling parties should damage such a connection.27 Elections without power turnovers, on the other hand, are not expected to affect political connections. We focus on elections in 2004–2010 because corporate guidance information is available in Capital IQ starting in 2002 and we wish to examine firms’ voluntary disclosure behavior 2 years before and after the elections. To be included in this analysis, sample countries must have elections between 2004 and 2010. We also require firms, including politically connected firms, to have necessary financial data in periods both before and after the elections.28

Table 5 presents the results of this analysis. Panel A describes the sample countries experiencing elections with and without power turnovers. Panel A shows that thirteen sample countries have parliamentary systems and six have presidential systems. Thirteen countries in our sample experience elections that result in power turnovers (i.e., “realigning elections”) in 2004–2010, while thirteen but a non-identical set of countries experience elections without power turnovers.29 We follow Julio & Yook (2012) and define the fiscal year for a firm as the election year if the date of the election lies between 60 calendar days prior to the end of fiscal year t and 274 calendar days after the end of fiscal year t.30 There is a wide variation in the election years across our sample countries, which helps strengthen our identification strategy by mitigating the undue influence of unobservable factors common across the nations at a particular time.

Panel B of Table 5 presents the regression analysis of the effect of realigning elections on voluntary disclosure practices of connected firms. In column (1) we regress the proxy of voluntary disclosure (Freq) on the indicator for connected firms (PC), the indicator for post-election years (Post), their interaction, and the set of control variables as in Eq. (2).31 We find that the coefficient on PC is negative and significant at the 0.01 level. This result is consistent with the result in Table 3 and indicates a lower frequency of management forecasts for connected firms in the 2 years before the elections. More importantly, the coefficient on the interaction term PC × Post is significantly positive at the 0.01 level, consistent with the notion that following the realigning elections politically connected firms increase management forecasts more than non-connected firms.32

There are several alternative explanations for the results in Panel B of Table 5. For example, connected firms are more likely to be in main industries that contribute to a country’s overall economy, and voters are likely to penalize the incumbent more when the economy is bad, resulting in party turnovers. We address this concern by controlling for bad news indicator (BadNews) and industry fixed effects. Another potential concern of our analysis is that the results may be driven by political uncertainty and firms’ response to uncertainty prior to elections. Julio & Yook (2012) find that firms reduce investment expenditures in election years due to political uncertainty. Thus an alternative explanation for our result in column (1) of Panel B is that firms suppress voluntary disclosures before elections in response to political uncertainty and return to the normal disclosure level after the election, and this behavior is more pronounced among politically connected firms. To examine whether politically connected firms suppress voluntary disclosures more than non-connected firms prior to elections, we follow Bertrand & Mullainathan (2003) and replace the Post indicator with indicator variables that track the effect of the elections before and after they take place. Specifically, we interact PC with four indicator variables, Yr − 1, Yr0, Yr1, and Yr2, which equal to one for the year prior to, the year of, the year after, and 2 years after the elections, respectively, and zero otherwise. The period of the 2 years prior to the election serves as a benchmark. We include year fixed effects in the regression and therefore omit the main effects of year indicators, Yr − 1, Yr0, Yr1, and Yr2. We report the results in column (2) of Panel B. We find insignificant coefficients on PC × Yr − 1 and PC × Yr0, and significantly positive coefficients on PC × Yr1 and PC × Yr2. This result suggests that the increase in management forecasts among connected firms is unlikely due to heightened political uncertainty leading firms to temporarily suppress voluntary disclosure prior to or during the election year.

In columns (3) and (4), we break down political connections into two types: firms connected to government officials or members of parliaments (GovParli) and firms with close relationships to a top official (Relation), and rerun the analysis in columns (1) and (2). In column (3), we find a significantly negative coefficient on GovParli but an insignificant coefficient on Relation. This result is consistent with Faccio (2006) and indicates that the negative relation between political connections and the frequency of management forecasts prior to the elections is significant only for the more objective type of connections (GovParli). Further, column (3) reports a significantly positive coefficient on GovParli × Post and an insignificant coefficient on Relation × Post, suggesting that the increase in the number of management forecasts following the elections is present only among firms connected with government officials or members of parliaments. In column (4), we find insignificant coefficients on GovParli × Yr − 1 and GovParli × Yr0, and significantly positive coefficients on GovParli × Yr1 and GovParli × Yr2, similar to the result in column (2). This result provides further support that the increase in management forecasts among connected firms is due to the elections that damage their political connections.

Panel C of Table 5 reports results of the parallel analysis based on elections that result in no power turnovers. If the damaged political ties motivate connected firms to increase voluntary disclosures after the power-realigning elections, we should not observe similar results around elections that do not result in power turnovers. In sharp contrast to the results in Panel B, we find that the coefficient on PC × Post is insignificant in column (1), and the coefficients on PC × Yr1 and PC × Yr2 are insignificant in column (2). When we break down political connections (PC) into GovParli and Relation, the result is similar. That is, we find an insignificant coefficient on GovParli × Post in column (3) and insignificant coefficients on GovParli × Yr1 and GovParli × Yr2 in column (4).33 In sum, the results in Panel C suggest that politically connected firms do not change their voluntary disclosure practices when their connections remain intact after the elections. These results also suggest that confounding factors such as increased economic or political uncertainty around elections are unlikely to explain the findings in Panel B, and thus lend further support to the causal link between political connections and voluntary disclosure.

To provide additional insights into the effect of political realignment on management earnings forecasts, we manually collect information on earnings forecast properties issued by connected firms from Capital IQ. We examine changes in the number of additional line items forecasted (Additional line items), whether the forecast is accompanied by an explanation (Explanation), whether forecasted earnings is a loss (Loss), and the degree of specificity in forecast forms such as range or point estimates (Specificity).34 Results in Table 5, Panel D suggest that politically connected firms forecast more additional line items and are more likely to provide accompanied explanations for the earnings forecasts following the realigning elections. This is consistent with the notion that connected firms expand their disclosure once their political ties are damaged. Interestingly, we also find that connected firms become less specific in making forecasts following the realigning elections. One possible explanation for this finding is that uncertainty of connected firms’ fundamentals increases after they lose their political ties and therefore these firms are unable to issue forecasts with high specificity. These results hold among a constant sample of connected firms issuing forecasts in both the pre- and post-election periods.

Mechanisms and Alternative Explanations

Political Connections and (Dis) Incentives for Voluntary Disclosure

As discussed previously, disclosure theories suggest that firms are more likely to provide voluntary disclosure when they have greater capital market incentives and face higher litigation risk. They are less likely to provide voluntary disclosure when they have higher proprietary costs. We argue that political connections weaken these disclosure incentives and disincentives. In this section, we further examine how these three mechanisms (i.e., capital market incentives, litigation risk, and proprietary costs) influence the difference in the voluntary disclosure choices of connected firms versus non-connected firms.

We first take advantage of cross-country differences in the capital market development to examine the role of capital market incentives. Because the demand for transparency is associated with the development of capital markets, we posit that the negative relation between political connections and the level of management forecasts is more pronounced in countries with greater capital market development. We perform this analysis by re-estimating Eq. (2) after partitioning the sample based on the median value of the country-level stock market efficiency, which indicates whether stock markets provide adequate financing to companies (El Ghoul, Guedhami, & Kim, 2017).35 Columns (1) and (2) of Table 6 present the results. We find that the coefficient on PC is more negative in countries with a more efficient stock market than in countries with a less efficient stock market, and the difference across partitions is significant at the 0.01 level. This result is consistent with the notion that lower financing need and weaker capital market incentives drive connected firms to disclose less than non-connected firms.

Next, we explore the role of litigation risk. Because the benefit of disclosure in mitigating litigation risk is more important in industries with higher litigation risk, we expect the disclosure gap between connected firms and non-connected firms to be greater in more litigious industries. We thus predict that the negative relation between political connections and the level of management forecasts is more pronounced in more litigious industries. Following Li (2010), we measure litigious industries using an indicator variable equal to one if a firm operates in a high litigious industry, namely industries with four-digit SIC code 2833–2836, 8731 8734 (bio-tech), 3570–3577 (computer hardware), 3600–3674 (electronics), 7371–7379 (computer software), 5200–5961 (retailing), 4812–4813, 4833, 4841,4899 (communications), or 4911, 4922–4924, 4931, 4941 (utilities).36 We re-estimate Eq. (2) after partitioning the sample into litigious and non-litigious industries and present the result in columns (3) and (4) of Table 6. We find that the coefficient on PC is more negative in litigious industries than in non-litigious industries, and the difference across partitions is significant at the 0.01 level. Thus this result suggests that connected firms’ lower litigation risk is another factor that explains why they issue fewer management forecasts than non-connected firms.

Finally, we investigate the role of proprietary costs. Because politically connected firms have greater access to government contracts and support and therefore face less proprietary costs when disclosing more information, the lower proprietary costs may motivate connected firms to disclose more, counterbalancing the effect of capital market incentive and litigation risk. Thus we expect the disclosure gap between connected firms and non-connected firms to be less pronounced when proprietary information is abundant. We capture the effect of proprietary costs using industry-adjusted R&D expenditure, measured by a firm’s R&D expense deflated by sales, adjusted by the two-digit SIC industry average (adjR&D). While R&D intensity has been used as a proxy for proprietary costs (e.g., Ellis, Fee, & Thomas, 2012), R&D intensity varies by industry and industry-level R&D may capture the entry barrier to the industry (Sutton, 1991). Thus we calculate industry-adjusted R&D to measure the extent of the firm-level proprietary information. We re-estimate Eq. (2) after partitioning the sample based on the sample median value of adjR&D and present the result in columns (5) and (6) of Table 6. We find that the coefficient on PC is more negative among firms with lower industry-adjusted R&D, and the difference across partitions is significant at the 0.01 level. Thus this result suggests that product market concerns are another contributing factor to the difference in management forecast frequency between politically connected firms and non-connected firms.

Political Rent Seeking: An Alternative Explanation?

In this section, we explore empirically whether the negative effect of political connections on management forecasts documented in Table 3 is driven by an alternative explanation of political rent extraction. The political rent-seeking explanation suggests that connected firms may prefer information opacity to obscure their gains from politicians. For example, insiders of connected firms have incentives to divert benefits brought by political connections, which in turn motivate them to maintain an opaque information environment in order to divert monitoring and scrutiny by outsiders. In particular, controlling shareholders of connected firms may want to suppress information on true economic performance in order to ensure that their diversionary practices, largely stemming from political cronyism and corruption, are kept hidden.

We test this alternative explanation by re-estimating Eq. (2) after partitioning the sample based on the median values of the degree of country-level corruption. If political rent seeking is the primary driver of the different voluntary disclosure practices between connected firms and non-connected firms, we expect our results to be more pronounced in countries with more corruption than in countries with less corruption. We follow Faccio (2006) and use the International Country Risk Guide’s assessment of the corruption in governments based on La Porta et al. (1998) (ICRGCorrupt), and a corruption index based on interviews with German exporters as developed by Neumann (1994) (GermanCorrupt).37 Higher values of both corruption proxies indicate more corruption in a country. Table 7 reports results of the regression analysis. For both measures of corruption, the coefficient on PC is more negative in countries with less corruption, and the difference in the coefficient on PC across partitions is significant at the 0.01 level.38 This result is inconsistent with the prediction based on the political rent-seeking explanation. That is, political rent seeking and/or the desire to mask political favors are unlikely to be the main driver for the voluntary disclosure practice of connected firms.

Finally, the result in Table 7 deviates from the IB literature that finds a negative relation between corruption and information transparency (Chen et al., 2010; Cuervo-Cazurra, 2006; DiRienzo, Das, Cort, & Burbridge, 2007; Zhao, Kim, & Du, 2003). Chen et al. (2010) show that the negative effect of political connections on analyst forecast error is stronger in jurisdictions with higher levels of corruption. Cuervo-Cazurra (2006) and Zhao et al. (2003) suggest that corruption increases transaction costs and creates social-cultural barriers to foreign direct investment. DiRienzo et al. (2007) find that countries with greater access to information and communication technology tend to have lower corruption levels. An important explanation for the different result is that corruption levels are generally lower in countries with greater capital market development. Thus the results in Tables 6 and 7 should be considered together to understand the mechanisms through which political connections relate to voluntary disclosure. Our result indicates that the effect of capital market incentives dominates the effect of corruption and rent seeking, if any, in explaining the voluntary disclosure behavior of politically connected firms.

Conclusions

This study examines the effect of political connections on managers’ voluntary disclosure choices in global markets. We find that politically connected firms are associated with a lower level of management forecasts, and this relation is more pronounced in countries with stronger capital market development and in more litigious industries, and for firms with less proprietary information. Using worldwide presidential and legislative elections that result in a power turnover, we find that connected firms increase the frequency of management forecasts subsequent to these elections. Our study is the first to examine whether and how political connections affect voluntary disclosure. Our results suggest that relatively low financing need and low litigation risk as well as lack of product market concerns shape the distinct voluntary disclosure practices for connected firms.

We acknowledge several limitations of our study. First, as in prior studies such as Chaney et al. (2011) and Chen et al. (2010), we rely on Faccio’s (2006) political connection data, which cover a relatively small sample of high-level connected firms in a short time period and may lead to under-representation of connected firms in certain countries. Our results may not speak to the disclosure incentives of connected firms outside of our sample if the role and influence of politics in our sample countries are much different than those in other countries. Second, we focus on a specific type of political connections, i.e., large shareholders or directors being high-level government officials. Whether and how other forms of political ties affect firms’ disclosure behavior in the global setting remains an interesting avenue for future research.

Notes

-

1

This literature typically focuses on corporate connections to high-level politicians, which are more common outside the US due to less stringent regulations and/or poor institutional environments. Benefits associated with high-level political connections include access to credit from government-owned banks, lower tax burdens, lax regulatory enforcement, and receipt of government contracts and financing (Adhikari et al., 2006; Faccio et al., 2006; Claessens et al., 2008). Politically connected firms are also insulated from bankruptcy, which enables them to invest in risky projects (Boubakri et al., 2013). Examples of costs include rent extraction by politicians and excessive government intervention that results in inefficient investment (Fan et al., 2007; Khwaja & Mian, 2005).

-

2

For example, Chaney et al. (2011) suggest that connected firms have a lesser need to respond to market pressure to increase information transparency by documenting that connected firms have poorer earnings quality than non-connected firms. In contrast, Guedhami et al. (2014) argue that connected firms have a greater incentive to improve information transparency to convince outside investors that they refrain from self-dealing. Consistent with their argument they find that connected firms are more likely to appoint Big N auditors than non-connected firms.

-

3

Faccio (2006) identifies politicians for most countries as of 2001. We begin our sample period in 2002 because the coverage of Capital IQ’s corporate guidance information begins in 2002. We end the sample period for our primary analyses in 2004, the first year in which one of our sample countries experiences a political realignment due to major elections, to avoid measurement errors in our political connection variable.

-

4

The finding of earnings quality being negatively related to political connections is not necessarily generalizable to management forecasts because poorer earnings quality, as typically measured by higher discretionary accruals, may be driven by various motivations including (1) meeting or beating markets’ expectations of earnings, (2) improving the informational value of earnings, and (3) opportunistic earnings management to increase managers’ compensation or mask true performance (Ayers, Jiang, & Yeung, 2006; Subramanyam, 1996). While the first two motivations may imply more management forecasts to facilitate expectation management or convey managerial private information, the third motivation can be associated with fewer management forecasts to hide political favors. Evidence based on auditor choices also has ambiguous implications for politically connected firms’ preference for transparency. Politically connected firms may appoint Big N auditors as a way to (1) improve information transparency and credibility, or (2) leverage the insurance value of large auditors.

-

5

For example, firms connected with members of parliament during our sample period include well-known companies such as Fiat from Italy, British Petroleum from the UK, and Intel from the US.

-

6

Our additional analyses in Table 4 suggest that more direct and visible political ties are more negatively associated with management forecasts. In addition, state ownership, an alternative measure of political connections, is also negatively associated with management forecasts.

-

7

For example, Halliburton is not included in Faccio’s sample. However, Dick Cheney, who was Vice-President from 2001 to 2009, House Representative from 1979 to 1989, Secretary of Defense from 1989 to 1993, was Chairman and CEO of Halliburton from 1995 to 2000. One reason is that Faccio imposes timing requirements in coding political connections. Specifically, her coding considers former heads of state or prime ministers, not former members of parliament or future heads of state/prime ministers. Thus Halliburton is not coded as a politically connected firm when Cheney was Chairman and CEO under Faccio’s approach (because he is an ex-member of parliament) but is coded as a connected firm in other studies that consider such a background.

-

8

We address the potential issues regarding Capital IQ’s coverage in sensitivity tests.

-

9

Furthermore, because management forecasts provided by Capital IQ are in text forms, collecting information on forecast characteristics from Capital IQ is challenging and time-consuming.

-

10

Inverse Mills ratio is calculated differently for treated firms (i.e., connected firms) and untreated firms (i.e., non-connected firms) (Tucker, 2010).

-

11

Our results are robust to including country fixed effects instead of the country-level factors in the first-stage regression.

-

12

In a sensitivity test, we also estimate a probit regression with an indicator for at least one management forecast issued over the fiscal year as the dependent variable. The analysis, reported in Panel A of Table 4, finds that our inference remains unchanged. We focus on the regression with the disclosure frequency as the dependent variable throughout the article because the structural two-stage model for the endogenous treatment effects may result in inconsistent parameter estimates if the second-stage specifications are non-linear such as the probit model (Das, Jo, & Kim, 2011; Greene, 1993).

-

13

As shown in Table 4, our results are robust to alternative clustering schemes.

-

14

Controlling for earnings volatility also helps address the potential concern that politically connected firms face a greater demand for information from market participants due to their increased likelihood of undertaking risky projects (Boubakri et al., 2013).

-

15

We use the term IAS to refer to both the International Accounting Standards issued by the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC), and the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) issued by its successor, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB).

-

16

We end our sample period in 2004 because this is the first year in which one of our sample countries (Indonesia) experiences a political realignment from major elections. Our results (untabulated) remain qualitatively the same if we extend the sample period to 2005, as in Chaney et al. (2011) and Guedhami et al. (2014).

-

17

Regulations for disclosure of forward-looking information differ across countries. We include country fixed effects in all our regressions to control for country-specific factors that influence voluntary disclosure practices.

-

18

The number of connected firms included in Chaney et al. (2011) ranges from 168 to 209 depending on their samples using different measures of accruals quality. Our connected firms represent almost 2 percent of the total firm-year observations, which is comparable to the 2.7 percent as reported in Faccio’s (2006) full dataset.

-

19

As reported in Table 4, our results are robust to using a control sample matched on country, year, and two-digit SIC industry, as well as excluding countries with the largest number of connected firms.

-

20

In untabulated analysis, we use a negative binomial regression to model the effect of political connections on the frequency of management forecasts in the second stage and continue to find a negative coefficient on PC (significant at the 0.10 level).

-

21

−77.4% = (exp(−0.457)−1)/0.474, where −0.457 is the coefficient on PC in column (2) of Table 3 and 0.474 is the average number of forecasts for non-connected firms in Table 2.

-

22