Abstract

Taking into account expected return characteristics like firm size and book-to-market in the selection of winners and losers helps to ex ante separate stocks with momentum from those that exhibit reversal in international equity markets. A strategy that buys small value winners and sells large growth losers generates significantly larger momentum profits than a standard momentum strategy, is robust to common return controls, and does not suffer from return reversals for holding periods up to 3 years. The superior performance of the strategy is attributable to a rather systematic exploitation of cross-sectional mispricing among momentum stocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last three decades, the momentum effect has become one of the most examined return patterns in finance. In their seminal work, Jegadeesh and Titman (1993) demonstrate that a strategy that buys past winners and sells past losers produces large abnormal returns for holding periods up to 1 year. Since then, the momentum effect has been documented in international equity markets, within industries, and across different asset classes (Rouwenhorst 1998; Moskowitz and Grinblatt 1999; Asness et al. 2013). However, over longer holding periods, momentum portfolios, in general, suffer from a return reversal pattern, i.e., the abnormal returns earned over the first year after portfolio formation reverse or even turn negative in subsequent years (Jegadeesh and Titman 2001; Blackburn and Cakici 2017).

Despite the enormous body of literature on the momentum effect, explanations for the return behavior of momentum stocks remain an ongoing debate. Daniel et al. (1998) were among the first to present a behavioral model based on investors’ overconfidence that explains the short-term return continuation and long-term return reversal patterns of typical momentum strategies. Conrad and Kaul (1998) suggest a risk-based explanation that is, however, contradicted by Jegadeesh and Titman (2002) who argue that momentum portfolios should not suffer from return reversals if the risk-based interpretation is correct.Footnote 1

Recently, Conrad and Yavuz (2017) take up again this debate by arguing that stocks with momentum can be separated from those that exhibit reversal when risk-based expected return characteristics like firm size and book-to-market are taken into account in the selection of winners and losers. Assuming that these firm characteristics are responsible for differences in expected returns (Fama and French 1992), they construct two distinct momentum strategies that differ in their underlying risk characteristics. The MAX momentum strategy takes a long position in high-risk winners, i.e., small value winners, and a short position in low-risk losers, i.e., large growth losers. Analogously, the MIN momentum strategy goes long in low-risk winners (large growth winners) and short in high-risk losers (small value losers).

Studying the US equity market, Conrad and Yavuz (2017) find that the MAX strategy does not only yield larger momentum profits than the standard momentum strategy in the short run, it also does not display significant return reversals for holding periods beyond 1 year. In contrast to that, the MIN strategy produces no significant momentum profits in the short run but suffers from substantial and significant return reversals in the long run. Thus, short-term return continuation and long-term return reversals are not necessarily linked. Taking into account expected return characteristics like firm size and book-to-market in the selection of winners and losers helps to ex ante separate stocks with momentum from those that exhibit reversal.

The approach of Conrad and Yavuz (2017) seems to be related to the style momentum of Chen and DeBondt (2004) who propose a strategy that goes long in firms with in-favor styles, e.g., being small value stocks, and short in firms with out-of-favor styles, e.g., being large growth stocks, based on the past price performance of these style characteristics. However, there exist clear differences. First, Chen and DeBondt (2004) document in their study that style momentum is distinct from pure price momentum by showing that both strategies possess unique information about subsequent stock returns that is not captured by the other strategy. Second, though the MAX and MIN strategies also take into account firm size and book-to-market in the selection of winners and losers, the focus of these strategies is on using these characteristics as risk measures for separating high-risk from low-risk momentum stocks. Consequently, the strategies’ long and short legs are uniformly defined. In contrast, the long- and short-leg portfolios of style momentum strategies can potentially also consist of mid-cap blend-style stocks or non-dividend-paying stocks, which are not in the center of attention of the MAX and MIN strategies. Third and finally, while the motivation of Chen and DeBondt (2004) is the improvement of style rotation strategies with respect to firm size and value/growth, the MAX and MIN strategies are motivated by the idea that momentum can be separated from reversal for constructing enhanced momentum-based investment strategies.

In this paper, we contribute to the literature by studying the findings of Conrad and Yavuz (2017) outside the USA. As with any finding in empirical research, the decomposition of momentum and reversal could be the result of data snooping in the sense of Lo and MacKinlay (1990) and therefore be sample-specific. To address this concern, we independently examine in this study the novel MAX and MIN strategies in the broad cross section of international firms drawn from 20 developed non-US equity markets. Obtaining results similar to the previous US evidence in Conrad and Yavuz (2017) would strengthen their findings and may lead to a better understanding of the momentum and reversal return patterns across equity markets.

From the previous US evidence, we derive three hypotheses that we test out-of-sample in non-US equity markets. The first hypothesis directly addresses whether international stock returns conform to the same pattern observed in the USA.

H1

A strategy that buys small value winners and sells large growth losers, the MAX strategy, yields significantly larger benchmark-adjusted returns over holding periods up to 1 year than a strategy that buys large growth winners and sells small value losers, the MIN strategy.

Showing that the short-term performance of the MAX strategy is superior to the MIN strategy is only the first part of the key results of Conrad and Yavuz (2017). Second and even more important may be the finding that considering expected return characteristics like firm size and book-to-market in the selection of winners and losers helps to ex ante separate momentum stocks that display return reversals from those that do not. Therefore, we further investigate the return behavior of the MAX and MIN strategies over longer holding periods up to 3 years and formulate our second hypothesis as follows.

H2

Over holding periods beyond 1 year, the MAX strategy displays no return reversal, while the MIN strategy exhibits significant return reversal.

The distinct return behavior of the MAX and MIN strategies may be attributable to the varying underlying risks associated with different levels of firm size and book-to-market, as argued by Conrad and Yavuz (2017). However, these well-known firm characteristics can also be interpreted as measures of mispricing (e.g., Lakonishok et al. 1994; Shleifer and Vishney 1997; Hirshleifer and Jiang 2010). Though Conrad and Yavuz (2017) reject that the level of market-wide mispricing as measured by market states and the investor sentiment is influential in the results observed, they do not rule out explanations based on cross-sectional mispricing. That is, the possibility that the different return behavior of the two strategies is the result of a rather systematic exploitation of existing mispricing among momentum stocks that is induced by taking into account mispricing-related measures like firm size and book-to-market in the stock selection procedure. Because mispricing at the individual firm level may add to our understanding of the varying return behavior of the MAX and MIN strategies, we formulate our third and final hypothesis as follows.

H3

The strong performance of the MAX strategy and the weak performance of the MIN strategy are the outcome of cross-sectional mispricing.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section describes the data and variables used in this study. The subsequent sections test the outlined hypotheses and present the empirical results. The final section concludes the paper.

Data and summary statistics

The dataset used in this study consists of an international sample of firms from 20 developed non-US equity markets. Our sample selection resembles the countries included in the well-known EAFE (Europe, Australia, and the Far East) stock market benchmark from MSCI which measures the foreign stock market performance outside of North America. We collect monthly total return data on common stocks from Datastream and firm-level accounting information from Worldscope. To ensure that accounting information is known before the returns are calculated, we match the latest accounting information for the fiscal year ending in the previous calendar year with stock returns from July of the current year to June of the subsequent year throughout the paper. All data are denominated in US dollars. To ensure that tiny or illiquid stocks do not drive our results, we follow Ang et al. (2009) and exclude very small firms by eliminating the 5% of firms with the lowest market equity in each country. In addition, as in Fama and French (1992), we also exclude firm-year observations with negative book equity and financial firms with Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes between 6000 and 6999. The sample period is from July 1990 to June 2017 (henceforth 1990–2017), and the sample comprises on average 7652 firms per month. Distributional statistics for the sample firms across countries are given in Panel A of Table 1.

The variables used in this study are defined as follows. A firm’s size (SZ) is its market equity (stock price multiplied by the number of shares outstanding) measured as of June each year in million US dollars. Book-to-market (BM) is the ratio of book equity to market equity at the fiscal year-end. Momentum (MOM) is the cumulative prior 6-month stock return, skipping the most recent month (Jegadeesh and Titman 1993). Following Fama and French (2015), operating profitability (OP) is revenues minus cost of goods sold and interest expense, all divided by book equity.Footnote 2 Investment (INV) is the annual change in total assets divided by lagged total assets. To proxy for systematic mispricing in the later analysis, we employ a financing-based misvaluation measure that is based on Bradshaw et al’s (2006) external financing (XFIN) variable. XFIN is the sum of net equity financing and net debt financing divided by lagged total assets. Net equity financing is the sale of common and preferred stock minus the purchase of common and preferred stock minus cash dividends paid. Net debt financing is the issuance of long-term debt minus the reduction in long-term debt.Footnote 3

Panel B of Table 1 summarizes the distributional statistics of the variables over the 1990–2017 sample period. A typical firm in our international sample has a size of $955 million in terms of market equity, an average relative valuation based on book-to-market of 0.96, and a mean past 6-month return of 5%.

Abnormal returns of MAX and MIN strategies

In this section, we test hypothesis H1 that the MAX strategy yields larger benchmark-adjusted returns than the MIN strategy. To do so, we examine the returns to winners and losers on the MAX and MIN strategies at the individual firm level using the Fama and MacBeth (1973) methodology and conduct difference-of-means tests on the average coefficient estimates from the regressions. For comparison purposes, we also include the standard momentum strategy in the analysis to gauge the strength of the MAX and MIN momentum premiums in relation to the unconditional momentum investing approach in international equity markets.

In particular, we estimate three different specification variants nested within the following firm-level cross-sectional regression, where the future 12-month holding period return of firm i in month t is regressed on two binary indicator variables, denoted Long and Short, in conjunction with common controls that are all available before the month in which the return measurement begins:

We apply Newey and West (1987) adjusted t statistics here and in all subsequent regressions to correct for the holding period overlap in the statistical inference (Jegadeesh and Titman 1993). An indicator variable takes the value of one if the underlying condition holds for a firm and zero otherwise. For the standard momentum strategy, Long and Short are equal to one if the firm’s past 6-month return is in the top or bottom tercile of the MOM distribution, respectively. Thus, the long leg describes winners, while the short leg denotes losers. When studying the MAX and MIN strategies, the indicator variables also take into account the firm’s size and book-to-market ratio as expected return characteristics in line with Conrad and Yavuz (2017). For the MAX strategy, Long is equal to one if the firm has a past six-month return in the top tercile of the MOM distribution and simultaneously a firm size in the bottom tercile of the SZ distribution and a book-to-market ratio in the top tercile of the BM distribution, thus classifying the firm as a small value winner. On the other hand, Short is equal to one if the firm has a past six-month return in the bottom tercile of the MOM distribution and simultaneously a firm size in the top tercile of the SZ distribution and a book-to-market ratio in the bottom tercile of the BM distribution, thus classifying the firm as a large growth loser. For the MIN strategy, the indicator variables are defined in an analogous manner using the tercile classifications based on SZ, BM, and MOM. In particular, Long is here equal to one if the firm is a large growth winner and Short is equal to one if the firm is a small value loser.Footnote 4

Taking into account the most recent developments in asset pricing (Fama and French 2015), the set of common control variables includes firm size, book-to-market, operating profitability, and investment for measuring benchmark-adjusted returns. Except for MOM, which is updated monthly, the other explanatory variables are updated each June. Furthermore, since we combine firms from multiple countries in the analysis, we include country dummies here and in all subsequent regressions to control for possible country effects.

Table 2 presents average coefficient estimates from the outlined firm-level cross-sectional regression setting for the standard, MAX, and MIN momentum strategies along with difference-of-means tests to assess whether the strategies produce significantly different momentum profits. The last row provides the economic and statistical significance of the average return premiums associated with the three strategies based on the difference between the long- and short-leg coefficient estimates.

To begin with, specification (1) reports the results for the standard momentum strategy. As indicated by the average coefficient estimates on Long and Short, past winners are associated with significantly positive subsequent returns (1.74% per year), while past losers are associated with subsequent negative returns (− 1.83% per year). Though the strategy’s short-leg return is statistically somewhat weaker over the sample period, the spread in average returns is sufficient to obtain a significant (long–short) standard momentum premium of 3.57% per year after controlling for firm size, book-to-market, operating profitability, and investment.

Specifications (2) and (3) report the results for the novel MAX and MIN strategies. When the MAX strategy is considered, where the long leg consists of winners with high expected return characteristics (small and value) and the short leg is based on losers with low expected return characteristics (large and growth), the attainable momentum premium is economically and statistically greatly enhanced and amounts now to more than 7.34% per year. The average return premium is here equally driven by the strategy’s long leg (3.63% per year) as well as by the short leg (− 3.70% per year). In contrast, when the MIN strategy is considered, where the long leg consists of winners with low expected return characteristics (large and growth) and the short leg is based on losers with high expected return characteristics (small and value), the attainable momentum premium is with its value of 1.20% per year statistically not reliably different from zero.

Comparing our international results to the previous US evidence in Conrad and Yavuz (2017) indicates, in general, a similar return behavior across equity markets. In a related analysis that also controls for the Fama and French (2015) benchmark variables, they report significant MAX momentum premiums of 1.01% per month over the strategy’s first 6 months and 0.59% per month over the subsequent six-month period, which correspond to about 10.03% on an annual basis (formally, (1 + 0.0101)6 × (1 + 0.0059)6 − 1) over their 1965–2010 sample period. For the MIN strategy, they report insignificant premiums of 0.11% per month over the first 6 months and − 0.23% over the following 6 months, which correspond on average to − 0.72% per year.

The estimates on the control variables echo in general prior results in the literature and corroborate their importance as cross-sectional return determinants in non-US equity markets. International stock returns are significantly positively associated with book-to-market and operating profitability, while they are significantly negatively related to investment. In contrast, we do not find that firm size has significant power predicting returns during the sample period. This result is, however, also in line with recent international evidence (e.g., Fama and French 2012, 2017).

The difference-of-means tests in the last three columns show that the average return premiums associated with the MAX and MIN strategies are significantly different from the standard momentum premium and to each other. Relative to the standard strategy, the return spread between winners and losers is noticeably more pronounced when small value winners and large growth losers are considered (MAX), while it is less pronounced when large growth winners and small value losers constitute the strategy (MIN). Finally, the difference between the MAX and MIN momentum premiums is statistically highly significant and amounts to more than 6.14% per year.

An inspection of the individual difference-of-means tests reveals that both legs of the MAX strategy significantly contribute to its superior overall performance, regardless of which of the other two strategies is used for comparison.

Since the MAX strategy appears to be the most promising of the three from an investment perspective, we further investigate the strategies’ turnover and potential transaction costs to shed light on practical implementation issues. To begin with, though momentum-based investment strategies are often implemented with monthly rebalancing in the literature, we primarily focus in our analysis on the performance over a twelve-month holding period to identify strategies that do not require frequent rebalancing in order to lower transaction costs. Examining the turnover (across the long- and short-leg portfolios) of the standard, MAX, and MIN momentum strategies in terms of unique stock additions and removals, we find on average values of 33.63%, 39.56%, and 36.67% per year, respectively.Footnote 5 However, since we study the strategies based on Fama and MacBeth (1973) regressions which are analogous to creating equal-weighted portfolios, the annual rebalancing to equal weights could potentially increase the turnover to 100% per year.Footnote 6 Does this circumstance eliminate the superior performance of the MAX strategy after accounting for corresponding transaction costs?

We address this question by employing the novel insights of Frazzini et al. (2018) who have analyzed over 1.7 trillion dollars of executed trades across 21 developed equity markets over a 19-year period from AQR Capital, a large institutional asset manager that is well known for its scientific and factor-based investing approach. Though their cost measures fully take into account bid-ask spreads, market impact costs, and commissions, they find that real-world trading costs are much smaller compared to the—typically assumed—costs used in previous studies.Footnote 7 For instance, realized trading costs for long or short positions in non-US stocks are on average 0.11% or 0.22% and range for small stocks from 0.23% (long) to 0.27% (short). Using for simplicity the largest magnitude of 0.27% regardless of the given order type and an annual turnover of 100%, the roundtrip costs would only amount to 0.54% per year which seems negligible in light of the MAX strategy’s abnormal return of 7.34% per year.

Up to this point, our full sample results fall right in line with our first hypothesis. To further assess the robustness of our findings across time, firm size, and regions, we repeat our cross-sectional regression analysis for the MAX and MIN strategies in two different sub-periods, among small and large firms, and in three different regions (Asia-Pacific, Europe, and Japan). The corresponding results are presented in Table 3, where Panel A shows estimates for the MAX strategy and Panel B shows estimates for the MIN strategy.

Specifications (1) and (2) report sub-period results. The earlier sub-period runs from July 1990 to December 2003 (162 months), while the later sub-period is from January 2004 to June 2017 (162 months). As documented by the average return premiums on the MAX and MIN strategies, the influence of the expected return characteristics on the realized momentum profits is persistent in the earlier and more recent half of the sample period. The MAX momentum premium is large and significantly present in both sub-periods, while the MIN momentum premium remains insignificant across time.

A further cause for concern for anomalous return patterns is their pervasiveness across size. Though we control for a possible size effect in the cross section of average returns by including firm size as one of the control variables, it is interesting to know whether our main findings hold across small firms as well as large firms. To address this question, specifications (3) and (4) report size-segmented subsample results.Footnote 8 The subsample of small (large) firms consists of the bottom (top) 50% of firms in each country in terms of market equity, measured as of June of each year. Though the MAX momentum premium is somewhat more pronounced among smaller firms, as it is the case for most other return anomalies, it is not limited to small firms but also significantly present among the largest and economically most important firms in international equity markets. In contrast, we do not find that the MIN strategy produces significant momentum profits among small firms or large firms.

Finally, specifications (5)–(7) provide regional evidence by dividing the EAFE international sample into three major regions in line with Fama and French (2012, 2017). Asia-Pacific includes Australia, Hong Kong, New Zealand, and Singapore. With the exception of Japan, which represents a region of its own, Europe encompasses the remaining sample countries (see Panel A of Table 1). We observe that the MAX momentum premium is strong in terms of economic and statistical significance among Asian-Pacific and European equity markets. On the other hand, we do not find that taking into account expected return characteristics like firm size and book-to-market in the selection of winners and losers produces significant momentum profits in Japan.Footnote 9 This result is, however, consistent with Asness (2011) and others who have documented that momentum-based investment strategies do not seem to work among Japanese firms. The regional results for the MIN strategy corroborate in general our international cross-country findings of insignificant momentum profits on this type of strategy. The only exception is Europe, where the MIN momentum premium tends to be statistically significant, but in terms of its economic magnitude, it is still less than half of the corresponding European MAX momentum premium.

After having addressed the robustness of our main findings across time, firm size, and regions, we further study the MAX and MIN momentum premiums conditional upon business conditions. It is well known that the profits of momentum strategies vary with the general state of the economy. They tend to be large during expanding/optimistic states and small during contracting/pessimistic states (Jegadeesh and Titman 2011). To address whether the MAX and MIN strategies conform to the same pattern observed for standard momentum strategies, we estimate firm-level cross-sectional regressions based on Eq. (1) for two different specification variants that differ in the underlying state of the economy, i.e., contracting/pessimistic versus expanding/optimistic. We measure the two economic states using six different proxies based on market volatility, market states, investor sentiment, market liquidity, default spread, and the NBER recession indicator. The first two measures are based on international EAFE data, while the remaining measures are based on US data in lack of appropriate cross-country proxies. The use of US-based variables outside the USA can be motivated by Baker et al. (2012) who show that sentiment is contagious across countries and particularly driven by the US sentiment. Furthermore, Rapach et al (2013) document that the USA possesses, as the world’s largest and most important equity market, a leading role for international markets.

The proxies are defined as follows. Market volatility is the annual standard deviation of the value-weighted EAFE market portfolio returns over the 12 months prior to the beginning of the strategies’ holding period (Baker and Wurgler 2006). Following Cooper et al (2004), the market state is measured based on the cumulative return on the value-weighted EAFE market portfolio over the 36 months prior to the beginning of the strategies’ holding period. To capture investor sentiment, we rely on the monthly US sentiment index constructed by Baker and Wurgler (2006).Footnote 10 To measure market liquidity, we employ Hu et al’s (2013) noise index, which is based on the aggregate noise in the prices of US Treasury bonds, i.e., the differences between market and model-implied yields.Footnote 11 In light of the fact that the US Treasury bond market is one of the most active and liquid markets in the world and one with the highest credit quality, the level of noise in this market can be used as a market-wide measure of liquidity. In line with Fama and French (1993), the default spread is the monthly difference between the yield on an index of 10-year US corporate bonds and 10-year US Treasury bonds.Footnote 12 Finally, the NBER recession indicator for the USA is used to separate crisis from non-crisis periods over the sample period. Except for market states and the NBER recession indicator, the median of the given economic state proxy over the sample period is used to define periods of low and high values on that measure. Positive (negative) 36-month market returns separate up (down) market states.

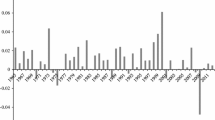

Figure 1 illustrates the average return premiums associated with the standard, MAX, and MIN momentum strategies during contracting/pessimistic business conditions (black bars) and expanding/optimistic business conditions (clear bars), as measured by the six different economic state proxies (Panels A to F). As before, the premiums are derived from the differences between the long- and short-leg coefficient estimates from the outlined firm-level cross-sectional regression setting that includes common return controls and country dummies.

Momentum premiums conditional upon business conditions. This figure illustrates the average return premiums associated with the standard, MAX, and MIN strategies in percent per year during contracting/pessimistic business conditions (black bars) and expanding/optimistic business conditions (clear bars), as measured by six different economic state proxies (Panels A to F)

First, regardless of the applied economic state proxy, the standard and MAX strategies are associated with significantly positive average return premiums during expanding/optimistic periods. Across the six proxies, the average momentum profits here amount to 5.56% per year on the standard strategy and 9.57% per year on the MAX strategy. During contracting/pessimistic periods, we do, however, not find that the standard and MAX momentum premiums are statistically significantly different from zero. The MIN momentum premium is in general insignificant in both states of the economy. The only two exceptions, where we find significantly positive momentum profits on this type of strategy are periods of low market volatility and after positive 36-month market returns (up markets).

Second, conducting difference-of-means tests on the strategies’ average momentum profits during a given economic state corroborates our previous inference on the superiority of the MAX strategy. Regardless of the applied economic state proxy and irrespective of the given economic state, the differences between the MAX and standard momentum premiums are always significantly positive and statistically significant. The same is true for the differences between the MAX and MIN momentum premiums. Hence, the MAX strategy is superior in comparison with the standard and MIN momentum strategies during contracting/pessimistic as well as expanding/optimistic periods. Comparing the MIN strategy relative to the standard strategy, we observe that the differences in premiums are persistently significantly negative during expanding/optimistic periods, while they are in general insignificant during contracting/pessimistic periods.

In sum, the results in this section are consistent with hypothesis H1. Similar to the prior US evidence, we observe that the MAX strategy produces significantly larger benchmark-adjusted returns than the MIN strategy and the standard momentum strategy in non-US equity markets over holding periods up to 1 year.

Longer holding period returns

Following the insights of Conrad and Yavuz (2017), we test in this section hypothesis H2 that the MAX strategy displays no return reversal, while the MIN strategy exhibits significant return reversal over holding periods beyond 1 year. To explore whether their US findings carry over to international equity markets, we estimate different firm-level cross-sectional regressions nested within Eq. (1), where the dependent variable now is the longer holding period return computed over the second and third year after the measurement of the strategies’ underlying firm characteristics.

Table 4 presents average coefficient estimates from the outlined firm-level cross-sectional regression for the two year-to-year holding periods. The results document that selecting winners and losers conditional upon their expected return characteristics based on firm size and book-to-market also has a major impact on the behavior of longer holding period returns.

While the MAX strategy yields strong momentum profits in the first year (see Table 2), it does not display significant return reversals in the following 2 years. The average coefficient estimates on Long and Short as well as the resulting (long–short) MAX momentum premium are all statistically indistinguishable from zero. This is in sharp contrast to the MIN strategy which does not produce significant momentum profits in the first year but suffers from substantial return reversals in the subsequent years. The average MIN momentum premium is − 4.83% per year in the second year and − 3.70% in the third year. As indicated by significantly positive short-leg returns, the reversal is primarily driven by the rebound of the strategy’s short leg that generates benchmark-adjusted returns of around 3% per year.

Taken together, the results in this section strongly support hypothesis H2. Short-term return continuation and long-term return reversals are not necessarily linked. Taking into account expected return characteristics like firm size and book-to-market in the selection of winners and losers helps to ex ante separate momentum stocks that display return reversals from those that do not.

A mispricing-based explanation

In this section, we test our final hypothesis H3 that the strong performance of the MAX strategy and the weak performance of the MIN strategy are the outcome of mispricing. Even though Conrad and Yavuz (2017) argue in favor of a risk-based explanation, they do not rule out the possibility that the varying MAX and MIN momentum premiums may be attributable to cross-sectional mispricing. In particular, they only study whether the US premiums are related to market states and investor sentiment. Lagged market returns and the investor sentiment index are commonly used as market-wide proxies for mispricing that reflect aggregate investor confidence or risk aversion which may cause delayed overreaction among investors and therefore provide an explanation for the observed momentum pattern in average stock returns. However, both explanations fall short to explain the MAX and MIN momentum premiums. Though the level of market-wide mispricing may explain the varying strength of the momentum premium across time, existing mispricing at one point in time can also vary across firms (Hirshleifer and Jiang 2010; Walkshäusl 2016).

Following this reasoning, we explicitly investigate the aspect of cross-sectional mispricing as an explanation for the significantly different return behavior of the MAX and MIN strategies. To proxy for systematic mispricing, we employ the firm’s external financing behavior as measured by Bradshaw et al’s (2006) XFIN variable. Positive values on XFIN indicate issues, while negative values indicate repurchases. The opportunistic financing hypothesis (Ikenberry et al. 1995; Loughran and Ritter 1995) suggests that firms issue additional capital when prices are high and repurchase outstanding capital when prices are low. Thus, issues (repurchases) provide signals of potential overvaluation (undervaluation) based on the management’s private assessment of the firm’s intrinsic value relative to the market. Thus, if cross-sectional mispricing drives the return behavior of the MAX and MIN strategies, the realized momentum profits on the two strategies should consequently differ when the underlying momentum stocks are either perceived as overvalued or undervalued.

To examine whether the observed return premiums on the MAX and MIN strategies are attributable to the systematic exploitation of cross-sectional mispricing, we estimate firm-level cross-sectional regressions based on Eq. (1) for two different specification variants that differ in their underlying stock samples. Specification (1) excludes winners that are also issuers and losers that are also repurchasers, thus representing overvalued winners and undervalued losers. Specification (2) excludes winners that are also repurchasers and losers that are also issuers, thus, denoting undervalued winners and overvalued losers. The firms excluded from the corresponding samples are identified each month by their monthly updated MOM characteristic and their XFIN characteristic which is measured each June. By constraining the underlying stock samples in this way, we obtain groups of firms, where the perceived mispricing of winners and losers is in general favorable [specification (1)] or unfavorable [specification (2)] for momentum strategies that exploit cross-sectional mispricing.

Table 5 presents average coefficient estimates from the two outlined firm-level cross-sectional regression variants using holding period returns computed over the first, second, and third year after the measurement of the strategies’ underlying firm characteristics. Panel A shows estimates for the MAX strategy and Panel B shows estimates for the MIN strategy. For the sake of brevity, the estimates on the common control variables are not tabulated.

The results document that cross-sectional mispricing plays an important role in understanding the return behavior of MAX and MIN strategies. In line with our previous findings, the MAX strategy produces a significantly positive momentum premium in the first year and no significant return reversals in the following 2 years when the unfavorably mispriced winners and losers are excluded from the sample [specification (1)]. However, this inference changes considerably when the favorably mispriced winners and losers are left out. In specification (2), the MAX momentum premium is rendered insignificant in the first year, and the strategy now suffers from substantial return reversals in the second and third year.

Analogously, the previously found poor performance of the MIN strategy turns strong when the unfavorably mispriced winners and losers are excluded from the sample, as done in specification (1). The strategy then yields significantly positive momentum profits in the first year and exhibits no significant return reversals in the subsequent years. In contrast, when the favorably mispriced winners and losers are discarded in specification (2), the MIN strategy reveals its weak performance with strong return reversals in the second and third year.

Taken together, the results in this section strongly support hypothesis H3. The realization of the superior performance on the MAX strategy and the occurrence of the inferior performance on the MIN strategy is strongly dependent on cross-sectional mispricing. The varying performance of the MAX and MIN strategies among favorably mispriced and unfavorably mispriced winners and losers furthermore suggests that firm size and book-to-market may rather be proxies for cross-sectional mispricing than risk-based expected return characteristics.

Conclusion

In this paper, we test the US findings of Conrad and Yavuz (2017) that stocks with momentum can be ex ante separated from those that exhibit reversal by taking into account characteristics like firm size and book-to-market in the selection of winners and losers. We provide strongly supportive out-of-sample evidence on the previous US findings in the broad cross section of international firms drawn from 20 developed non-US equity markets over the sample period from 1990 to 2017.

A strategy that buys small value winners and sells large growth losers, denoted the MAX strategy, generates significantly larger momentum profits than a standard momentum strategy, is robust to common return controls, and does not suffer from return reversals for holding periods up to 3 years. In contrast, a strategy that buys large growth winners and sells small value losers, denoted the MIN strategy, produces no significant momentum profits but significant return reversals over holding periods beyond 1 year. Consistent with the view that firm size and book-to-market can also be interpreted as measures of mispricing, the significantly different return behavior of the MIN and MAX strategies is attributable to a rather systematic exploitation of cross-sectional mispricing among momentum stocks. The superior performance of the MAX strategy is driven by undervalued winners and overvalued losers, while the inferior performance of the MIN strategy is driven by the fact that the strategy’s underlying stock selection procedure picks overvalued winners and undervalued losers.

Notes

See Jegadeesh and Titman (2011) for an extended review of the literature.

We do not include selling, general, and administrative expenses, as this item is not broadly available among international firms. The return predictability of operating profitability is, however, not affected by this adjustment.

In line with Hirshleifer and Jiang (2010), we do not include the change in current debt, as it does not reflect market timing.

For each variable, we use the full SZ, BM, and MOM distribution across all sample firms, so that the stock selection procedure corresponds to independent sorts on the three variables, as in Conrad and Yavuz (2017).

These magnitudes are similar to the average turnover of value-weighted US momentum strategies (34.5%) that do not rebalance stocks to initial weights (Novy-Marx and Velikov 2016).

Jegadeesh and Titman (1993) find that even when equal-weighted portfolios are used for momentum strategies, the average turnover is usually less than 100%. They report an average value of 84.8% on their strategy.

The most important determinant of trading costs is the price impact, as bid-ask spreads and trading commissions do not scale with trading size.

To be consistent with the intended size segmentation, the MAX and MIN strategies use tercile classifications based on the SZ, BM, and MOM distributions among the bottom or top 50% of firms and not across all sample firms.

In light of this finding, we also have tested whether Japanese firms are influential in our inference that the MAX strategy is superior to the MIN strategy in international equity markets. For instance, the weighting of Japanese firms in the international MAX and MIN strategies could be responsible for the observed return difference. First, the average share of Japanese firms in the long-leg portfolios is with values of 25.99% (MAX) and 25.09% (MIN) very similar across the two strategies. Only the short-leg portfolios show, on average, a greater exposure to Japanese firms for the MAX strategy of 37.98% in comparison with 25.16% for the MIN strategy. Second, replicating the performance analysis for the MAX and MIN strategies in an international sample that excludes Japan (EAFE ex Japan) in analogy to Table 2 yields an average MAX momentum premium of 10.23% per year (t statistic of 4.45) and an average MIN momentum premium of 2.24% per year (t statistic of 1.32). Thus, the lack of momentum profits among Japanese firms cannot account for the inference that the MAX strategy is superior to the MIN strategy.

The sentiment index is available at Jeffrey Wurgler’s website: http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~jwurgler/. The index time series runs until September 2015.

The noise index is available at Jun Pan’s website: http://www.mit.edu/~junpan/. The index time series runs until December 2016. The data are provided on a daily basis. We employ the index’s daily end-of-month values for our analysis.

An appropriate US corporate bond index is available in Datastream from April 2002 onward.

References

Ang, A., R.J. Hodrick, Y. Xing, and X. Zhang. 2009. High idiosyncratic volatility and low returns: International and further U.S. evidence. Journal of Financial Economics 91(1): 1–23.

Asness, C. 2011. Momentum in Japan: The exception that proves the rule. Journal of Portfolio Management 37(4): 67–75.

Asness, C., T.J. Moskowitz, and L.H. Pedersen. 2013. Value and momentum everywhere. Journal of Finance 68(3): 929–985.

Baker, M., and J. Wurgler. 2006. Investor sentiment and the cross-section of stock returns. Journal of Finance 61(4): 1645–1680.

Baker, M., J. Wurgler, and Y. Yuan. 2012. Global, local, and contagious investor sentiment. Journal of Financial Economics 104(2): 272–287.

Blackburn, D.W., and N. Cakici. 2017. Overreaction and the cross-section of returns: International evidence. Journal of Empirical Finance 42: 1–14.

Bradshaw, M.T., S.A. Richardson, and R.G. Sloan. 2006. The relation between corporate financing activities, analysts forecasts and stock returns. Journal of Accounting and Economics 42(1–2): 53–85.

Chen, H., and W. DeBondt. 2004. Style momentum within the S&P-500 index. Journal of Empirical Finance 11(4): 483–507.

Conrad, J., and G. Kaul. 1998. An anatomy of trading strategies. Review of Financial Studies 11(3): 489–519.

Conrad, J., and M.D. Yavuz. 2017. Momentum and reversal: Does what goes up always come down? Review of Finance 21(2): 555–581.

Cooper, M.J., R.C. Gutierrez Jr., and A. Hameed. 2004. Market states and momentum. Journal of Finance 59(3): 1345–1365.

Daniel, K., D. Hirshleifer, and A. Subrahmanyam. 1998. Investor psychology and security market under- and overreactions. Journal of Finance 53(6): 1839–1885.

Fama, E.F., and K.R. French. 1992. The cross-section of expected stock returns. Journal of Finance 47(2): 427–465.

Fama, E.F., and K.R. French. 1993. Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics 33(1): 3–56.

Fama, E.F., and K.R. French. 2012. Size, value, and momentum in international stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics 105(3): 457–472.

Fama, E.F., and K.R. French. 2015. A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics 116(1): 1–22.

Fama, E.F., and K.R. French. 2017. International tests of a five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics 123(3): 441–463.

Fama, E.F., and J.D. MacBeth. 1973. Risk, return, and equilibrium: Empirical tests. Journal of Political Economy 81(3): 607–636.

Frazzini, A., Israel, R. and Moskowitz, T.J. 2018. Trading costs. In Working paper, AQR Capital and Yale School of Management.

Hirshleifer, D., and D. Jiang. 2010. A financing-based misvaluation factor and the cross-section of expected returns. Review of Financial Studies 23(9): 3401–3436.

Hu, G.X., J. Pan, and J. Wang. 2013. Noise as information for illiquidity. Journal of Finance 68(6): 2341–2382.

Ikenberry, D., J. Lakonishok, and T. Vermaelen. 1995. Market underreaction to open market share repurchases. Journal of Financial Economics 39(2–3): 181–208.

Jegadeesh, N., and S. Titman. 1993. Returns to buying winners and selling losers: Implications for stock-market efficiency. Journal of Finance 48(1): 65–91.

Jegadeesh, N., and S. Titman. 2001. Profitability of momentum strategies: An evaluation of alternative explanations. Journal of Finance 56(2): 699–720.

Jegadeesh, N., and S. Titman. 2002. Cross-sectional and time-series determinants of momentum returns. Review of Financial Studies 15(1): 143–157.

Jegadeesh, N., and S. Titman. 2011. Momentum. Annual Review of Financial Economics 3: 493–509.

Lakonishok, J., A. Shleifer, and R.W. Vishny. 1994. Contrarian investment, extrapolation, and risk. Journal of Finance 49(5): 1541–1578.

Lo, A.W., and A.C. MacKinlay. 1990. Data-snooping biases in tests of financial asset pricing models. Review of Financial Studies 3(3): 431–467.

Loughran, T., and J. Ritter. 1995. The new issues puzzle. Journal of Finance 50(1): 23–51.

Moskowitz, T.J., and M. Grinblatt. 1999. Do industries explain momentum? Journal of Finance 54(4): 1249–1290.

Newey, W.K., and K.D. West. 1987. A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica 55(3): 703–708.

Novy-Marx, R., and M. Velikov. 2016. A taxonomy of anomalies and their trading costs. Review of Financial Studies 29(1): 104–147.

Rapach, D.E., J.K. Strauss, and G. Zhou. 2013. International stock return predictability: What is the role of the United States? Journal of Finance 68(4): 1633–1662.

Rouwenhorst, K.G. 1998. International momentum strategies. Journal of Finance 53(1): 267–284.

Shleifer, A., and R.W. Vishny. 1997. The limits to arbitrage. Journal of Finance 52(1): 35–55.

Walkshäusl, C. 2016. Mispricing and the five-factor model. Economics Letters 147: 99–102.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walkshäusl, C., Weißofner, F. & Wessels, U. Separating momentum from reversal in international stock markets. J Asset Manag 20, 111–123 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-019-00109-5

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-019-00109-5