Abstract

The objective of this paper is to challenge three implicit assumptions about residents’ engagement with city branding: first, that disengaged residents may not be attached to their place; second, that residents’ desire engagement with official place branding; and third, that residents perceive place branding is appropriate for their city. In-depth semi-structured interviews were held with 22 residents of Dunedin, New Zealand, to examine their place attachment, place identity, understanding of city branding and attitudes toward their city’s brand. To assist residents to articulate their feelings about Dunedin, a visual elicitation method was used to assist them to articulate their place identity and place attachment. The findings identify tensions between residents’ place identity, their understanding of city branding and attitudes toward their city’s brand, underpinned by their attachment to the city. Many residents expressed place-protective attitudes towards anticipated changes to the social fabric of their community, which they perceive to be consequences of this urban governance strategy. Local authorities may need to re-think their adoption of place branding as a ‘one-size fits all’ solution to place management and find alternatives which promote the perceived uniqueness of the city while reinforcing residents’ multiple and complex place identities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Much of the early research on city branding, a sub-set of place branding, has focused on tourists as stakeholders; only more recently has attention turned to city residents as stakeholders (Insch and Stuart 2015; Merrilees et al. 2009). Braun et al. (2013, p. 21) considered that the role of residents as citizens is the “most neglected” aspect of place branding theory, despite residents’ capacity to grant political legitimacy to the city brand. This capacity is evident in cases where government authorities have adopted a top-down approach to city branding without the support of residents, resulting in a backlash from the latter (Braun et al. 2013; Zenker and Petersen 2014).

Previous research suggests that resident engagement with place branding may be enhanced by involving residents early in the official place branding process and also through improving their satisfaction with and attachment to place (Braun et al. 2013; Insch and Florek 2008; Kavaratzis and Ashworth 2008). Significantly, the majority of previous studies share three implicit assumptions about residents’ level of engagement in organised place branding processes: first, that disengaged residents may not be attached to their place; second, that residents’ desire engagement with official place branding; and third, that residents perceive city branding to be appropriate for their place.

The objective of this study is to question these implicit assumptions through examining residents’ relationship to the city in which they live and their engagement with city branding. Dunedin, New Zealand, was chosen as a case study as local government had implemented a city branding strategy to address a falling population, a decline in employment and low economic growth (Hooker 2007). An exploratory study by Insch and Stuart (2015) identified resident disengagement with these branding efforts. This study builds on this work but takes a holistic view of the factors influencing resident engagement with place branding. Specifically, it investigates how residents’ place identity and place attachment influences their engagement with city branding and identifies the underlying tensions in residents’ perceptions of place branding. In doing so, it addresses a gap in the place branding literature on the nuanced, complex relationship between residents and city branding practices, and explores the implications for local government authorities.

Residents and their relationship with place brands

Within the growing literature on place branding only a few studies have focused on the relationship between residents and the official place brands of their locality (Kavaratzis 2012; Insch and Stuart 2015; Kavaratzis and Kalandides 2015; Zenker and Petersen 2014; Zenker and Seigis 2012; Braun et al. 2013). Previous research identifies various capacities of residents in the place branding process—as an attribute of the place brand; as ambassadors of the place brand; as voters and ratepayers providing political legitimacy and financial support for the place brand (Braun et al. 2013). Indeed, resident participation and engagement with the place brand is argued to benefit the formation and development of place brands (Kavaratzis and Kalandides 2015). Among the many desirable outcomes of resident participation in the branding process are: increasing residents’ satisfaction and commitment to the city, increasing residents’ level of trust in local governing officials (Zenker and Seigis 2012), increasing residents’ ownership of the brand (Braun et al. 2013; Eshuis and Edwards 2012) and increasing residents’ loyalty behaviour, including purchase intentions and brand commitment (Kemp et al. 2012).

To date, research has focused on uncovering the antecedents of residents’ positive attitudes, self-brand connection and place brand loyalty and advocacy. Identifying the reasons why residents do not perceive their role or civic duty to support their place brand or to be involved in its development has not received sufficient attention. Researchers have identified differences in place brand images held by different stakeholder groups as a source of tension and possible derision by disaffected groups (Gotham 2007; Zenker and Beckman 2013). In their study of various resident and non-resident groups in Hamburg, Zenker and Beckman (2013) described how some residents did not support the city brand identity promoted by the local governing authority and launched the “Not in our Name” campaign (Zenker and Petersen 2014). Other documented cases of counter-branding demonstrate how “actors outside the expected-tourism and branding institutions” have rejected official city branding campaigns (Maher and Carruthers 2014, p. 248). Such actors, including residents, might oppose officially promoted city images in various ways as part of an “ongoing process of contestation over city identity” (Maher and Carruthers 2014, p. 249). Examples include appropriation of local governments’ official city brand elements (e.g., language, logo, font and colour) to change its meaning and communicate alternative agendas.

The possibility of combining multiple representations of a city into a unitary place brand is the dominant position advocated in the place branding literature. Less attention has been given to the existence of alternative and often opposing place brand narratives (Maiello and Pasquinelli 2015). Similarly, limited research has investigated how a city’s official branding may alienate some of the city’s residents and other stakeholder groups who may remain, or later become, disengaged from efforts to brand the city. Insch and Stuart’s (2015) study of resident city brand disengagement identified a lack of brand awareness, a lack of brand identification, disapproval of local government actions and residents’ cynical attitudes towards involvement as reasons for their disengagement. A study of different types of citizen participation in the governance of a large scale development project revealed that being invited to participate in the project had a greater impact on citizen satisfaction than the type of participation involved (Zenker and Seigis 2012). In particular, if residents consider their underlying place values and expectations are respected by local government officials, they may be more supportive of activities which promote their place to external stakeholder groups (e.g., tourists, new residents or investors). In order to conceive a holistic view of residents’ engagement (or indeed their estrangement) with city branding understanding what shapes residents’ relationship to the places they experience on a daily basis is first necessary.

Residents’ relationship with their city

Environmental psychology offers a conceptual lens for studying an individual’s relationship with the place in which they live. Two interrelated concepts, place attachment and place identity, are important to this research as they form the basis for understanding why and how residents incorporate aspects of place in their self-identity through experiencing place and can develop affective bonds with a place. In turn, these concepts and the four guiding principles of Breakwell’s (2015) identity process theory (IPT) offer a framework for understanding why residents might resist, or become disengaged, with their city brand.

Place attachment, a concept which has been defined in environmental psychology, human geography and sociology, is viewed as a process and an outcome of bonding oneself to an important place (Giuliani 2003). Low and Altman (1992) define the concept as a psychological process that can develop through cognition and affect, which has been shown to be a prerequisite for attaining a sense of stability, balance and good adjustment, as well as becoming involved in local activities in the community (Hay 1998). Individuals might form emotional ties and close bonds with a place through the “steady accumulation of experience with a place” or, alternatively, this process can occur quickly in settings featuring “dramatic landscapes” and places where individuals have had “intense experiences” (Stedman et al. 2004, p. 582). Individuals who are attached to their local area tend to become involved in their local communities through participating in social and sporting clubs and organisations (Anton and Lawrence 2014).

To clarify understanding of the concept of place attachment Scannell and Gifford (2010) offer a tripartite framework comprised of three major dimensions: (1) person—individual experiences in a place create meaning as well as the symbolic meanings of a place shared among a group (i.e., community or a cultural group); (2) process—affective (i.e., happiness, pride and love), cognitive (i.e., memory, knowledge, schemas and meaning) and behavioural components of the psychological process of place attachment (i.e., proximity-maintaining and reconstruction of place), and (3) place—characteristics of the place, both social (i.e., social area and social symbols) and physical (i.e., natural and built environment). This framework offers an integrative view of place attachment, which connects “the different types of bonds into a single overarching concept” (Scannell and Gifford 2010, p. 7).

Place identity, a concept closely related to place attachment, is centred “…on the psychological construct of identity and its relationship with social identity” (Uzzell et al. 2002, p. 29). Proshansky et al. (1983, p. 59) define the concept as a substructure of self-identity which encompasses cognitions about the physical world in which individuals live. These cognitions include memories, ideas, feelings, attitudes, values, and preferences about varied and complex environments that define the daily existence of each human being. The process of developing place identity occurs early in childhood through socialisation and continues throughout an individual’s lifetime; thus it is a “…dynamic, social product of the interaction of the capacities for memory, consciousness and organized construal…” (Breakwell 2015, p. 190).

Breakwell’s IPT has been used as a lens for explaining what guides self-identity and as a part of it, place identity (Anton and Lawrence 2014; Twigger-Ross and Uzzell 1996). This theoretical framework has four principles of identity: (1) self-esteem, (2) self-efficacy, (3) continuity over time and (4) distinctiveness from others. The principle of self-esteem, which relates to the positive evaluation of oneself or with the group which an individual identifies, suggests living in a place might be a source of pride for a resident if it boosts their self-esteem. The principle of self-efficacy relates to an individual’s belief in their capabilities to meet situational demands and cope with changing circumstances. In the context of place identity, self-efficacy refers to the ways the environment is perceived to facilitate, or at least not to hinder, an individual’s everyday lifestyle (Twigger-Ross and Uzzell 1996).

The third principle, continuity of the self-concept, is viewed as a key motive guiding the formation and maintenance of identity (Breakwell 2015) and in defining an individual’s relationships with places. Individuals seek to ensure the continuity of their self-concept by living in a place that represents their values. Disruption to the physical environment (e.g., flooding, demolition of homes) and associated social networks might threaten continuity of self, triggering residents to find another place to live (Twigger-Ross and Uzzell 1996). Change can also be more gradual such as the case where decisions to modify spatial plans lead to the influx of ‘outsiders’ (Dixon and Durrheim 2000). Finally, establishing a sense of distinctiveness is important in the process of acquiring place identity, as individuals seek to identify with those they perceive to share characteristics which are relatively rare and deemed positive in a particular context (Anton and Lawrence 2014). For example, a resident of a particular neighbourhood or city might use their place identification (i.e., I live in Hackney or I am a Londoner) as a basis for differentiating themselves (Twigger-Ross and Uzzell 1996).

The two concepts of place attachment and place identity do overlap (Table 1) and are fundamental to understanding why and how residents can form close bonds with places and how symbolic qualities of a place can hold important meaning for people. Examining residents’ perceptions and attitudes to official place branding activities, which promotes a selective representation of the city, first requires an understanding of how residents express their place attachment and place identity. Toward this end, the aims of the research reported in this paper were to: (1) examine residents’ place attachment and place identity and identify the salient aspects of their person-place relationship; (2) investigate residents’ attitudes and understanding of place branding as a tool of urban governance; and (3) identify sources of tension between their place attachment, place identity and engagement with place branding activities in their city of residence.

The research context: Dunedin city, New Zealand

Dunedin City, located in New Zealand’s South Island, is considered one of the four major cities in the country, despite having a smaller population than several North Island cities. The city’s population growth was relatively static between 1961 and 2001; growing by 1.5% (Dunedin City Council 2002). In the five years from 2001 to 2006, there was a resurgence in population growth to 3.8% (Statistics New Zealand 2006). However, from 2006 to 2013, this rate of growth contracted to 1.3% (Statistics New Zealand 2013). Slow population growth, allied with a decline in employment in some established industries and economic growth trailing other major cities, has been an ongoing source of concern for the Dunedin City Council (DCC).

Over the last three decades, the DCC has sponsored a number of city marketing and branding campaigns (Table 2). The first campaign, “It’s All Right Here”, designed to raise the city’s profile around the country, was launched in 1988. While a lack of financial support meant the campaign ended in the early 1990s, the slogan demonstrated a longevity; still being remembered or parodied more than two decades later (see for example, Fairfax Media 2012). The less successful “The Spirit of Dunedin” campaign followed in 1998. Neither campaign included community consultation and neither were considered to capture the ‘essence’ of Dunedin and what was unique about it (Hooker 2007).

Despite these attempts to market Dunedin, approximately 10,000 jobs have been lost in the city over the past two decades due to the centralisation of a number of government and large corporate head offices in other cities. The “I Am Dunedin” campaign was launched in 2001 with the express purpose of creating jobs and economic growth, and in doing so grow the population by 20,000 over the following decade. Unlike previous efforts, this branding campaign sought input from hundreds of Dunedin residents, and invited Dunedin-based creative agencies rather than outsiders to present proposals for the new marketing campaign (Hooker 2007). By 2010 the “I Am Dunedin” campaign had been completed and the DCC embarked on a new campaign titled ‘The Dunedin Brand’. Since its inception, it has not been widely communicated to the general public, rather focusing on targeted external audiences (e.g., visitors and investors).

Research methodology

In-depth semi-structured interviews with residents was considered the most appropriate means of investigating the research aims of this study, which focused on investigating residents’ place attachment and place identity, identifying salient aspects of their person-place relationship and exploring their attitudes and understanding of place branding. In addition, the research aimed to identify any sources of tension between their place attachment, place identity and engagement with place branding activities. As the chosen data collection method, in-depth personal interviews offered the means to gain new, rich insights that were unlikely to emerge from alternative means such as a structured self-completion questionnaire. Interviewees were probed beyond the semi-structured questions by asking how, why, and what questions to elicit understanding, explanation and clarification of their attitudes and perceptions (Creswell 2003). Interviews were conducted at interviewees’ homes located throughout the city over a four week period in June–July 2015. The interviews ranged in duration from 30 to 45 min in length and were digitally recorded and fully transcribed.

Snowball sampling, a non-probability sampling technique, was used to recruit a total of 22 individuals to participate in the research project, following Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) guiding principle that sampling be based on appropriateness. Recruitment of interviewees followed a chain-referral process whereby, at the end of each interview, participants were asked to nominate someone that they knew who lived in Dunedin that was aged 18 years or older who might be willing to participate. Throughout this process, the researchers aimed to ensure diversity among interviewee’s age, gender, occupation and suburb of residence to gain a variety of perspectives, to reduce potential bias.

The sample comprised an equal split of male and female Dunedin residents, residing in 17 different suburbs across the city, with an average age of 45 years (range 24–80 years), living in the city an average of 26 years (range 2–80 years). Three of the interviewees had lived in the city their entire lives. Occupations included government (public sector) employees, administrators, those employed in the education, finance, transport and tourism industries, one student and two retirees. Most interviewees were involved in their community, but the level of involvement varied—interviewees with children reported heavy involvement with school activities, some were involved with professional networking groups, while others participated in groups centred on sporting, religious or musical pursuits. Due to the sampling technique used, it is not possible to generalise to the population of the study; this is acknowledged as a limitation of this study.

This study also employed a visual elicitation method to assist residents articulate their feelings about Dunedin which may have otherwise remained elusive (Stedman et al. 2004). Interviewees were asked to bring along a photo or picture of Dunedin, which represents the city to them. This tool was also a useful means to build rapport with the interviewees to help them to feel comfortable sharing their attitudes and feelings with the interviewer. During the remainder of the interview, the interviewees were asked a set of open-ended questions which were derived from the main concepts in the tripartite framework of place attachment (Scannell and Gifford 2010) and Breakwell’s (2015) IPT. The general topics covered in the interview were:

-

(1)

attitudes and feelings toward Dunedin (including favourite place(s) in Dunedin);

-

(2)

involvement in community or social groups in Dunedin;

-

(3)

understanding of and attitudes to branding places;

-

(4)

awareness and perceptions of city branding in Dunedin; and

-

(5)

attitudes toward resident involvement in city branding.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was chosen as it is a sufficiently adaptable method that allows a latent (interpretive) approach to be taken with the interview data (Braun and Clarke 2006). The interview transcripts were initially read through to become familiar with their overall meaning and gain a sense of the main themes in relation to the research aims. At this stage, initial ideas and thoughts for coding the data in relation to the research questions were noted. In the second stage, the coding of the data became formalised and systematic as a set of initial codes was developed and applied by highlighting the segments of text that represented the code. From these two early phases of analysis the initial codes were generated and all relevant extracts for each code were collated. In the third stage a list of themes was created by sorting the different codes within the initial set of themes and starting to organise the themes into a thematic map to reflect their interrelationships. In the subsequent phase the themes were reviewed to ensure internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity (Patton 1990) so that data was coherent within themes and that distinctions between the themes were clear. The themes were reviewed both in relation to how they captured ‘the contours of the coded data’ (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 91) and how they accurately represented the data set as a whole and minor refinements to the coding and organisation of themes were made.

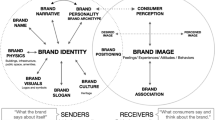

Saturation of themes, the point where additional data and further data analysis failed to uncover any new themes in relation to the research questions (Strauss and Corbin 1990; Guest et al. 2006), was reached after 22 interviews. Through the process of refining, defining and naming the themes and understanding the hierarchy of their meaning, from concrete to more abstract, a thematic map was created which captured the ‘meanings evident in the data set as a whole’ (Braun and Clarke 2006: 98). Two overarching themes were decided and within them, four sub-themes were identified (Fig. 1). The thematic map provided a visual tool for analysing and discussing the findings, and extracts from the interview transcripts were used to illustrate the themes (Braun and Clarke 2006). Interviewees were given a pseudonym to ensure their anonymity.

Findings

Attached to the city

Participants in this study articulated their attachment to various social-cultural and biophysical aspects of living in Dunedin. Their explanations of why they chose the particular image of Dunedin as meaningful allowed the elements of the natural and social environment that contributed to their attachment to Dunedin to be teased out. Among the places selected, those depicting the city’s landscape and natural assets were the most frequent (e.g., hilltops, and peninsula). Many participants chose a special place they visit regularly, which offers peace and quiet and solitude. Such places provide an opportunity for restorative experiences, enabling emotional and self-regulation, which are fundamental to constructing place identity (Korpela 1989). Photographs with family and friends, at a specific location, or engaging in a particular recreational activity were also described. Three interviewees chose flora or fauna they perceived as unique or special to represent the city (i.e., Royal Albatross, primroses covered in snow). In many instances, the photos and places represented in them involved both biophysical and social-cultural elements of place attachment (Stedman et al. 2004). One participant describes this integration of the two aspects:

So…believe it or not it’s a photo of my boyfriend…so the photographer is [xxx] who’s a local guy…Yeah! He takes photos of all the boys surfing – everyone around St Clair, pretty much – and my mum’s house is up here and my dad’s house is over here and I grew up here and I go for walks on the beach and I just love, like, the coastline in Dunedin, so I picked that one (Annelise, F, 24 years).

The majority of participants could choose a favourite place in Dunedin and could articulate the reasons for their choice. Overwhelmingly, participants described a location in the city’s natural environment. For a smaller group, it was their home and suburb of residence. For many, their special place was valued in terms of its natural beauty and amenity, such as for recreation, providing a place of solitude and tranquility and memories of time spent with their family. Four interviewees were unable to choose a favourite place in the city as they explained there were many individual places they preferred and could not single out a specific place. One participant, Piper (F, 37 years) experienced difficulty finding a favourite place and feels she “struggles with Dunedin” as a result.

Pride

For the majority of the interviewees, the way they speak about their lived experiences of Dunedin reveals a pride in being a resident of the city. Their speech often became animated when describing how they perceive the city, and it is evident they are immensely proud of Dunedin’s diverse natural and cultural assets and amenities and their location relative to their place of residence.

…being on the coast, being near the ocean, I love that we’ve got access to some really good nice bush [forest]…And then also being in the South Island, it doesn’t take actually that much to get to the mountains…But also if you look at Dunedin its also got really good art galleries, its got amazing cafés, if you’re into an evening or a night out there’s tons to pick from…, (Anton, M, 49 years).

The notion that people choose to live in Dunedin also engenders a sense of pride in the city:

Interestingly, a friend of mine from Auckland said that she had never known a city where so many people said that they loved it…I am proud that people want to move here, that people want to stay here (Kaye, F, 71 years).

Attachment to the city itself appears to be strong for nearly all interviewees—they feel pride and can articulate their feelings about the city to others. Based on their responses, these residents expressed their satisfaction with most features of the city, particularly the natural environment, which seems to reinforce their attachment to place.

People

The people of Dunedin are a significant theme forming interviewees’ attachment to the city. Interviewees frequently mentioned the village atmosphere and the importance of social relationships and sense of belonging. The scale of the city is seen to facilitate these social relationships and interactions. On a deeper level, the meaning of people as a sub-theme is related to the values Dunedinites hold which in turn foster a sense of kinship and communitas. Daniel (M, 51 years) described the types of values that are deemed important to people who live in Dunedin:

…people live here for the right reason, they’re not …too career orientated, they have a good work-life balance I believe, most people in Dunedin, so then they work by day but are part of a community by evening and night, and weekends, and it’s for me a hugely positive thing.

Interviewees also describe Dunedin people as caring, resilient in the face of adversity, parochial yet not boastful, creative, and innovative and entrepreneurial in their business endeavours. One participant (Rick, M, 61 years) describes the qualities of Dunedin residents he values and admires:

I think the way that people actually care about people in the city… there’s not too much graffiti, in fact there’s the opposite with the street art that’s starting, and the way that they’ve actually preserved the buildings.

Again, the sense of pride and respect residents have for the city is reflected in this statement by Rick, which highlights the attachment which residents have for the physical and built environment, as well as the interaction between people and the environment. Thus, any resources which are reinvested to restore and preserve these features are appreciated and people investing in these assets are admired.

Proximity

The notion of proximity features in a variety of forms. First, the proximity within the city itself—most interviewees view Dunedin as a compact city which is quick and easy to get around and a short commute from home to work. The interviewees also consider that Dunedin is in close proximity to nature and the countryside, enabling interviewees to escape the city and enjoy a sense of peace, solitude and/or freedom within minutes of leaving home. This proximity enables residents to ‘live’ in many parts of the city, enjoy what different areas have to offer, and feel connected to the wider city. Their satisfaction with the liveability and manageability of the residential environment is linked to the city’s perceived scale; many residents consider it to be an ideally sized city, offering all of the amenities of a large city, without the disadvantages (e.g., long commutes). This aspect of place enables a feeling of self-efficacy for residents, to develop a strong positive place identity.

Personality

Another sub-theme contributing to residents’ attachment to the city is personality which manifests itself in two main discourses. First, Dunedin is seen as having character and personality, with adjectives such as quirky, funky and creative used to describe the city and/or its residents. Many residents consider the creative community, as well as the music, art and fashion industries as giving the city a unique character or personality. Dunedin fashion and music is distinctive and recognisable: “…a big thing for Dunedin is the fashion isn’t it, it used to be like the music, the ‘Dunedin sound’ and stuff like that…” (Piper, F, 37 years). These elements contribute to residents’ self-esteem and in turn their place identity. Second, some interviewees perceive Dunedin’s personality as combining its historic sensibility with a more modern persona in a way which creates energy and vitality. This is attributed to the recent flourishing street art and the preservation and reuse of heritage buildings which provide a special mix of old and modern that adds colour and vibrancy to the city.

Disconnected from the city brand

The majority of interviewees understand the concept of branding and can articulate some form of lay definition, generally related to imagery, identity, association and reputation of a product or place. When asked to consider the application of branding to places most interviewees feel it plays an important role in differentiating a place. One interviewee considered it to be a ‘necessary evil’. However, some feel branding a city is not in keeping with “what a city is” (Kaye, F, 71 years), and yet “they all seem to be doing it” (Lyall, M, 43 years). Thus, there seems to be a degree of tension in how some interviewees perceive city branding, best encapsulated in this comment: “Oh…[sighs]…I understand it, but I don’t kind of…it’s not a commercial product, so I don’t quite sort of agree with it” (Rick, M, 61 years). In regards to Dunedin’s city brand, there is evidence of a disconnect from the city’s official brand communications among the interviewees. Three main sub-themes contribute to the theme of disconnect from the city brand: brand awareness, brand goals and brand buy-in.

Brand awareness

Interviewees expressed uncertainty about whether there has been any recent branding activity (within the last year) and also about the current city brand. Few are able to identify any recent branding activity. Some assume there is a current brand, but are unable to recall or articulate it. Others believe they know what the current brand is, but actually refer to either past branding campaigns or, as in the following case, to informal branding:

Dunedin is the wildlife capital of the world… As far as I am aware, yes, I think that’s one of the, well THE major one that Dunedin uses (Lyall, M, 43 years).

Less than a third of interviewees are aware of the current branding. However, even those who are conscious of it are confused about whether it is in fact a brand per se or whether it is one part of a wider promotional campaign for the city:

There’s a Dunedin website isn’t there, and it’s got the ‘Dunedin’ in that kind of funny script [laughs]…the gothic looking script, yeah but I can’t think of the specific campaign or words at the moment that are connected with Dunedin… (Netty, F, 46 years).

However, it is not only the current branding most interviewees lack awareness of—many interviewees are unable to identify any previous branding campaigns. Even Daniel (M, 51 years), whose children and dog modelled for a previous brand campaign considered it ‘so bad I can’t remember what it was!’ But after some consideration he recalls the brand, and how he feels about it:

…it was one of those ones they talk about the ‘Twink test’ – if you twinked out (erased) Dunedin and put anywhere else in, whether it’s Napier, Hamilton, Brisbane, Bangkok or anything would it still fit, so…“Spirit”? Well… [shrugs] so no, so I think over the years we’ve had one good one but we’ve had some that I just don’t think have really…captured.

This comment also alludes to why it does not resonate strongly enough with him to remember—the idea of ‘capturing’ the essence of Dunedin in a manner which elicits buy-into the brand. At a fundamental level, the messages about Dunedin being communicated through the city brand do not reflect the place identity of those interviewed.

Brand goals

The sub-theme of brand goals is subtle yet fundamentally important in contributing to interviewees’ disconnect from the city brand. Many interviewees feel the purpose or value of the branding campaigns for the city’s residents has not been communicated by the local government. Anton (M, 49 years), who took part in the focus group sessions for the “I Am Dunedin” campaign, still has reservations about the effectiveness of city branding in terms of achieving its stated goals:

The “I Am” is probably trying to get people to have personal identity with the place that they live, and then I’m not sure if, I really don’t know if that attracts people into Dunedin…

These residents also expressed their reservations toward the local government’s economic development goal of population growth; they like the size, character and ‘village’ atmosphere of the city and would like to see more jobs for residents so they do not have to move out:

Personally I don’t really want to see the city grow too much more anyway… I like it the size it is, I appreciate it needs to have some form of growth, but not…not hugely. Growth needs to be probably more in terms of industrial growth or forms of employment for the people that are here (Don, M, 47 years).

The interviewees prefer Dunedin as it is. Some voiced a fear of ‘outsiders’ coming in who might change the atmosphere of the city. In line with this, some interviewees convey the idea that the city best sells itself through what it does informally outside the remit of its city branding campaigns:

I actually think there’s lots about Dunedin that almost promotes it just by being as it is, like festivals and things like that…and letting people know about those sorts of things without necessarily having a huge campaign, advertising campaign that costs a lot of money (Netty, F, 46 years).

Residents perceive that these festivals and events may be able communicate the essence of Dunedin’s arts, culture, heritage and wildlife in a way that a brand or slogan may not. The majority of interviewees express a reluctance to brand Dunedin—or at least not for the reasons that they perceive the local government authority deem as important.

Brand buy-in

Most interviewees cannot personally identify with the official city brand, leading to a lack of self-brand connection and brand buy-in. Many cannot see a clear link between the city brand and their lived experience of Dunedin. This is perhaps best summed up by Anton (M, 49 years):

…so marry up the experiences and how I feel about living in Dunedin, and the branding, and they’re actually two dysfunctional subjects, so I look at the branding and…I don’t even want to acknowledge the branding in some ways; it doesn’t resonate with me at all. And I’d be surprised if you found someone that it did.

Others do not buy into Dunedin’s city branding because of a perceived lack of continuity in the local government’s branding strategy:

That’s the other issue, there’s been so many of these things…it’s like every three or four years it’s time to rebrand ourselves, they’ll bring out another campaign, well hang on, is the old one…dead?…but that to me is part of the problem with city branding, we lurch from one thing to another every few years (Daniel, M, 51 years).

Comments such as these were voiced by a number of interviewees and are symptomatic of a wider mistrust of and frustration with the local government authority. The lack of brand buy-in is related to the gap between lived experience of Dunedin residents and the city’s branding—an unclear message, frequent changes, and underlying doubts about the competence and strategic direction of the local government. Nevertheless, despite this lack of buy-in, many of the interviewees believe it is preferable to be involved in decision-making about city branding and many indicate they would participate in such processes if given the opportunity. On the other hand, some of those interviewed are opposed to the idea of engagement per se, as Daniel (M, 51 years) explains: “No. I have had input into the, ah, annual plan before and it was…blankly ignored and having been inside council when stuff has come in, I’m not proud of the way the council handles a lot of the stuff that comes in from the community. No”.

Discussion and conclusions

Previous research suggests place attachment is linked with place satisfaction (Insch and Florek 2008; Ramkissoon et al. 2013). The majority of residents interviewed in this study demonstrate both attachment to and satisfaction with their city, passionately articulating their pride in the city. Thus, it is unlikely that a lack of place attachment or satisfaction is driving their disengagement with the Dunedin brand. On the contrary, and challenging the first implicit assumption in the literature, their place satisfaction and attachment appear to underlie residents’ passive resistance to the local City Council’s place branding campaign.

Some residents believe that the DCC is seeking to achieve economic growth via population growth, and they do not share this ambition for the city. Rather, they wish to preserve the character of the city and consider such changes might threaten this continuity and feelings of distinctiveness they receive from living in the city. Specifically, interviewees are concerned that potential new migrants attracted by the branding campaign might not share their values of community and pride in the city. Research examining place attachment and place protective behaviours offers a reason for interviewees’ disconnect from city branding despite their strong attachment to the city (Stedman 2002; Devine-Wright 2009). Where there is a strong attachment to place based on identity, this may manifest in place-protective attitudes and behaviour when that place is perceived to be threatened.

In this study the interviewees view the goals of city branding as potentially threatening their place identity. In essence, interviewees fear the four sources of their attachment to the city (pride, proximity, people and personality) may be threatened. Furthermore, there is a sense of fear that ‘outsiders’ moving into the city to live and work may change the dynamics of the community, resulting in a larger, more dispersed and less-friendly city. As Anton and Lawrence (2014, p. 452) explain, “if people feel that the place they are attached to is threatened and that the landscape could change into a place to which they no longer feel an emotional bond, they could act negatively towards the people or organisations responsible for that change”. This study identifies that residents may perceive that a city’s branding, like other urban governance strategies, has the potential to disrupt their notion of the physical and social characteristics of the city that they value highly. Such a change in the status quo could in turn threaten their place identity and lessen their place attachment.

This research sought to identify sources of tension between residents’ relationship with their city and their engagement with their city brand, contributing to the limited literature on resident perspectives on place branding. The findings suggest that even where place identity, and attachment are strong, resident engagement with city branding may be limited. This can be explained by the discordance between the purpose of city branding, as espoused and practiced by local government authorities, and the desire for continuity of residents’ place identity. This finding is consistent with a study by Stedman (2002) which demonstrated that respondents were more likely to indicate an intention to engage in place protective behaviours “when important symbolic meanings are threatened by prospective change” (p. 577).

As this study shows, residents may also have an existing general mistrust of those responsible for enacting city branding strategies due to the negative legacies of previous campaigns, frustration with the local government and concerns about the competency of brand managers. In contrast to overt protest and resistance, apathy and indifference may become a symptom of this tension. In order to conserve their existing place identity, residents are unlikely to become engaged in any form of consultation or collaboration which is perceived to redefine their place identity. Such a form of resistance, which has also been demonstrated in the case of a community that was largely dissatisfied with their town’s image (Mayes 2008), reflects residents’ unease with attempts to capture the essence of their place identity and feelings of being disconnected or even excluded. This finding provides evidence that residents may be resistant to engage in the process of branding their city, thereby challenging the second implicit assumption in the literature. This may be due to their attitudes toward the local government based on past experiences and/or lack of support for the goals of the campaign.

As this paper demonstrates, the third implicit assumption identified in the literature that residents believe city branding to be appropriate for their place may be flawed. Thus, understanding their ambitions for the city might be the starting point for determining whether city branding is a preferred strategic option for residents as well as local businesses and governing authorities. Considering the needs of residents at the outset recognises the need to evaluate the role and impacts of place branding practices in wider society, beyond the immediate interests of often dominant local elites (Mayes 2008).

The major implication of this study for place branding practice is that some local authorities might need to re-think the adoption of a place branding strategy as a ‘one-size fits all’ solution to urban governance and economic development. Finding alternatives such as an event-led strategy to urban development might prove more appropriate and compatible with the goals of local stakeholders and is an avenue for further research. In addition, residents in this study identified positively with certain regeneration initiatives, which preserved the heritage of the city and were consistent with the distinctiveness and personality of the place. Mechanisms which promote the uniqueness of the city to external audiences and reinforce residents’ place identity might be more acceptable to residents, who are the major contributors to and benefactors of building and reinforcing a strong place brand identity.

Given the geographical focus of this study on Dunedin, a relatively small city, future research should investigate other cities both in New Zealand and internationally of differing size to investigate residents’ engagement with their place brand. In this regard, it is not clear whether size matters, or whether there are other underlying factors (e.g., history or level of economic prosperity), influencing the relationships between residents and their city brand engagement.

References

Anton, C.E., and C. Lawrence. 2014. Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. Journal of Environmental Psychology 40: 451–461.

Braun, E., M. Kavaratzis, and S. Zenker. 2013. My city—my brand: The role of residents in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development 6: 18–28.

Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101.

Breakwell, G. 2015. Coping with threatened identities. London: Psychology Press.

Creswell, J. 2003. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.

Devine-Wright, P. 2009. Rethinking NIMBYism: The role of place attachment and place identity in explaining place-protective action. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 19: 426–441.

Dixon, J., and K. Durrheim. 2000. Displacing place-identity: A discursive approach to locating self and other. British Journal of Social Psychology 39: 27–44.

Dunedin City Council. 2002. Monitoring Population: August 2002. Dunedin: Dunedin City Council.

Eshuis, J., and A. Edwards. 2012. Branding the city: The democratic legitimacy of a new mode of governance. Urban Studies 50: 1–17.

Fairfax Media. (2012) Top 10 worst NZ city slogans. stuff.co.nz.

Giuliani, V. 2003. Theory of attachment and place attachment. In Psychological theories for environmental issues, ed. M. Bonnes, T. Lee, and M. Bonaiuto, 137–170. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Gotham, K.F. 2007. Authentic New Orleans: Tourism, culture, and race in the big easy. New York: New York University Press.

Guest, G., A. Bunce, and L. Johnson. 2006. How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18: 59–82.

Hay, R. 1998. Sense of place in the developmental context. Journal of Environmental Psychology 18: 5–29.

Hooker, J. 2007. Branding Dunedin: Passionate, active, vibrant, youthful. In Working on the edge: A portrait of business in Dunedin, ed. K. Inkson, V. Browning, and J. Kirkwood, 78–87. Dunedin: Otago University Press.

Insch, A., and M. Florek. 2008. A great place to live, work and play: Conceptualising place satisfaction in the case of a city’s residents. Journal of Place Management and Development 1: 138–149.

Insch, A., and M. Stuart. 2015. Understanding resident city brand disengagement. Journal of Place Management and Development 8: 172–186.

Kavaratzis, M. 2012. From ‘necessary evil’ to necessity: stakeholders’ involvement in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development 5: 17–19.

Kavaratzis, M., and G.J. Ashworth. 2008. Place marketing: How did we get here and where are we going? Journal of Place Management and Development 1: 150–165.

Kavaratzis, M., and A. Kalandides. 2015. Rethinking the place brand: The interactive formation of place brands and the role of participatory place branding. Environment and Planning A 47: 1368–1382.

Kemp, E., C. Childers, and K. Williams. 2012. A tale of a musical city: Fostering self-brand connection among residents of Austin, Texas. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 8: 147–157.

Korpela, K.M. 1989. Place identity as a product of environmental self regulation. Journal of Environmental Psychology 9: 241–256.

Lincoln, Y.S., and E.G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications.

Low, S.M., and I. Altman. 1992. Place attachment: a conceptual inquiry. In Human Behavior and Environment, ed. I. Altman, and S.M. Low, 1–12. New York: Planum.

Maher, K.H., and D. Carruthers. 2014. Urban Image Work: Official and grassroots responses to crisis in Tijuana. Urban Affairs Review 50: 244–268.

Maiello, A., and C. Pasquinelli. 2015. Destruction or construction? A (counter) branding analysis of sport mega-events in Rio de Janeiro. Cities 48: 116–124.

Mayes, R. 2008. A place in the sun: The politics of place, identity and branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 4: 124–135.

Merrilees, B., D. Miller, and C. Herrington. 2009. Antecedents of residents’ city brand attitudes. Journal of Business Research 62: 362–367.

Patton, M.Q. 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. London: Sage.

Proshansky, H.M., A.K. Fabian, and R. Kaminoff. 1983. Place identity: Physical world socialization of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology 3: 57–83.

Ramkissoon, H., L. David, G. Smith, et al. 2013. Relationships between place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour in an Australian national park. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 21: 434–457.

Scannell, L., and R. Gifford. 2010. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 30: 1–10.

Statistics New Zealand. 2006. 2006 Census QuickStats about a place: Dunedin City. http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2006CensusHomePage/QuickStats/AboutAPlace/SnapShot.aspx?tab=Agesex&id=2000071.

Statistics New Zealand. 2013. 2013 Census QuickStats about a place: Dunedin City. http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/quickstats-about-a-place.aspx?request_value=15022&parent_id=14973&tabname=#.

Stedman, R.C. 2002. Toward a social psychology of place: Predicting behavior from place-based cognitions, attitude, and identity. Environment and Behavior 34: 561–581.

Stedman, R.C., T. Beckley, S. Wallace, et al. 2004. A picture and 1000 words: Using resident-employed photography to understand attachment to high amenity places. Journal of Leisure Research 36: 580–606.

Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. 1990. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications Inc.

Twigger-Ross, C.L., and D. Uzzell. 1996. Place and identity processes. Journal of Environmental Psychology 16: 205–220.

Uzzell, D., E. Pol, and D. Badenas. 2002. Place identification, social cohesion, and environmental sustainability. Environment and Behavior 34: 26–53.

Zenker, S., and S.C. Beckman. 2013. My place is not your place—different place brand knowledge by different target groups. Journal of Place Management and Development 6: 6–17.

Zenker, S., and S. Petersen. 2014. An integrative theoretical model for improving resident-city identification. Environment and Planning A 46: 715–729.

Zenker, S., and A. Seigis. 2012. Respect and the city: The mediating role of respect in citizen participation. Journal of Place Management and Development 5: 20–34.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Insch, A., Walters, T. Challenging assumptions about residents’ engagement with place branding. Place Brand Public Dipl 14, 152–162 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-017-0067-5

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-017-0067-5