Abstract

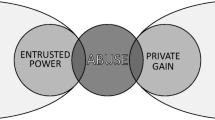

The search for a universally acceptable definition of corruption has been a central element of scholarship on corruption over the last decades, without it ever reaching a consensus in academic circles. Moreover, it is far from certain that citizens share the same understanding of what should be labelled as ‘corruption’ across time, space and social groups. This article traces the journey from the classical conception of corruption, centred around the notions of morals and decay, to the modern understanding of the term focussing on individual actions and practices. It provides an overview of the scholarly struggle over meaning-making and shows how the definition of corruption as the ‘abuse of public/entrusted power for private gain’ became dominant, as corruption was constructed as a global problem by international organizations. Lastly, it advocates for bringing back a more constructivist perspective on the study of corruption which takes the ambiguity and political dimensions of corruption seriously. The article suggests new avenues of research to understand corruption in the changing context of the twenty-first century.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Corruption is one of today’s most high-profile social ills and has become one of the world’s most talked-about issues (Heywood 2015, 1). Long seen as a ‘pathology of underdevelopment’ (Gledhill 2004), corruption is understood today as a problem shared across societies, despite significant variations in scale and form. Not only is there a consensus on the fact that corruption exists in all countries and all sectors, but corruption is now seen as a global problem ignoring national borders (World Bank 2020). It is a great source of public anxiety because, in itself, corruption undermines the values and rules of democratic systems and fair public service, but also because it causes, or at least facilitates, the emergence of other problems, including some of the most existential threats that have (re)surfaced over the last decades, such as climate change, transnational organized crime, terrorism or global health challenges (OECD 2017; Klein 2014; UN 2020; Steingrüber et al. 2020).

Corruption is also one of the most challenging problems of our contemporary world, deemed by some to be a growingly wicked problem (Rittel and Webber 1973; Heywood 2019; Wickberg 2020). Indeed, despite a substantial rise in research on corruption and an exponential growth of policy initiatives since the ‘corruption eruption’ following the end of the Cold War (Naim 1995), anti-corruption efforts are considered today as a global policy failure (Quah 2008; Heeks and Mathisen 2012; Persson et al. 2013; Marquette and Peiffer 2018). We still lack information and understanding on the mechanisms and dynamics of corruption in practice. Given the methodological challenges associated with the analysis of corruption practices as they unfold, we know little about the nature of these practices, the actual motivations of participants, the pressures they find themselves under or their understanding of the situation. The anti-corruption agenda has become global and programmes considered as ‘good practices’ have spread, leading to a certain degree of policy convergence (Hough 2013; Katzarova 2019; Wickberg 2020). There is a need for more contextually sensitive research and policy (Heywood 2017), to better understand the role of political structures and social norms and practices (in different countries and sectors) in manifestations and conceptions of corruption (Heidenheimer and Johnston 2002; Ledeneva 2008; Kubbe and Engelbert 2017).

Another major challenge facing policy-making and research in this area is the increasing instrumentalization of anti-corruption rhetoric in a time of growing anti-politics sentiment (Fawcett et al. 2017; Clarke et al. 2018; Mungiu-Pippidi and Heywood 2020). This trend indeed tends to further blur what is already considered an ‘essentially contested concept’ (Gallie 1956; Rothstein and Varraich 2017), which can be understood in different ways and sustain a variety of competing narratives. This ambiguity stems from corruption being, at the same time (but not necessarily for the same people), a crime, an analytical concept, a negatively loaded term of appraisal and a public problem whose definition evolves through the actions of policy actors. As Elizabeth Harrison (2006, 26) suggests, corruption is ‘both a normative concept and a set of practices that help some people and seriously harm others’. This duality captures the important idea that corruption is both ambiguous in the abstract (what is corruption?) and in the particular (what practices should be labelled corruption?).

Research on corruption has flourished since the 1990s, with scholars studying every aspect of the problem, from its causes and consequences to its mechanisms, forms and workings (see Heywood 2015; Mungiu-Pippidi and Heywood 2020 for an overview of the different aspects of corruption research). This article will review only one dimension of this rich literature, namely research on the concept itself. It looks, albeit briefly, at the ways in which corruption has been defined, tracing the history of the concept and highlighting the more recent definitional battles, before exposing how the currently mainstream understanding of corruption as the ‘abuse of public/entrusted power for private gain’ (World Bank, Transparency International) imposed itself. In a last section, it advocates for taking the ambiguity and political dimensions of corruption seriously, and proposes new avenues of research to understand corruption in the twenty-first century.

Making sense of corruption

A short history of an old concept

Today, corruption is often presented as a universal phenomenon that has existed through time and space (Alatas 1968; Mendilow and Phélippeau 2019; Knights 2018). Its meaning has, however, fluctuated between being understood as the nature of certain individuals or organizations that are corrupt and being seen as the influence of external factors that corrupt someone or something that was good or pure in its original state. Buchan and Hill (2014) show that corruption has gone from referring to the broadly understood condition of things departing from an original state to describe economic crime and the misconduct of public officials, specifying that there is no fixed temporal demarcation as these conceptions have always coexisted.

‘Corruption’ comes from the Latin corruption/corrumpere—to destroy or ruin—and was later used in Old French. The Centre national des ressources textuelles et lexicales (CNRTL) traces its use back to the twelfth century, attributing different meanings to the term: ‘alteration from what is sane, honest in the soul’ and later, in the fourteenth century ‘action of diverting someone from their duty with money or favours’.Footnote 1 The Oxford English Dictionary traces the use of the term in Old English to the fourteenth century and also attributes various definitions to the term corruption: giving it a physical definition (‘the destruction or spoiling of anything, especially by disintegration or by decomposition with its attendant unwholesomeness’) as well as a moral one (‘moral deterioration or decay; the perversion of anything from an original state of purity’). Scholars tend to agree on the religious influence on the term (Friedrich 1972; Génaux 2004), Rothstein and Varraich (2017) tracing its roots in both Christian and Muslim faiths.

What is common to all these definitions is the notion of change, of departure from an original or pure state, be it a physical, a moral or a social state. Scholars having explored the origins of the concept suggest that this idea of change and degeneration comes from the Aristotelian opposition of permanence (aphthorà) and change (phthorà), found in his treatise Peri geneseôs kai phthoras translated to the Latin De generatione et corruption. This treatise is part of Aristotle’s work on physics and specifically on the generation, alteration and dissolution of things in nature, which will later be applied to the study of politics in his theory on constitutional change, corruption thus being understood as ‘system decay’. Looking at Classical, Medieval and Early Modern political thought, Buchan and Hill (2014) identify two discourses that have been used to make sense of corruption. The first, which relates directly to this notion of change, is what they label ‘degenerative conception’, associated with moral, spiritual but also political decay. They refer to the second one, being narrower and contemporary, as the ‘social-scientific conception of corruption’, which defines a specific form of abuse of power. The two interpretations have existed in parallel for centuries, with the degenerative conception remaining dominant until the end of the eighteenth century, when the conception of corruption as deviant behaviour took over.

The narrowing of the meaning of corruption illustrates the growing influence of a legal conception of corruption. According to Génaux (2002), corruption had a legal existence in Roman law and ius commune and was associated with the criminality of certain agents of public power, namely those exercising justice, as apparent in Sylla’s law, the Coutumes de Beauvaisis from 1246 and a series of European treatises of penal doctrine from the sixteenth century, all referring specifically to the corruption of judges. Historians situate the triumph of the more technical meaning of corruption and the emergence of political uses of the term in the late eighteenth century (Monier 2016; Kroeze et al. 2018). Corruption, no longer understood as system decay, becomes specifically used to describe the subversion of public office, as we can see in OED quotations from the nineteenth century that broadens the focus from judges to practices in parliaments or elections. The French criminal code of 1810 established the offence of bribery of public officials using the term corruption. Indeed, corruption in French legal language equates to the English bribery.Footnote 2

This narrow meaning of corruption, as compared to the pre-modern conception of corruption as moral decay, is closely tied to the philosophy of the Enlightenment, the development of Weberian bureaucracies, separation of the public and private spheres and interests, and the emergence of democratic regimes. The conception of corruption as individual abuse of power is often associated with the shift in political ideology in Britain and the emergence of the philosophy of David Hume, Adam Smith and Jeremy Bentham, which separated corruption from the notion of virtue to attach it to the idea of interests (Hirschman 1997; Buchan and Hill 2014; Boccon-Gibod forthcoming). Until the late eighteenth century, the amalgamation of public and private interests makes the contemporary understanding of corruption incongruous. Yves Mény explains this by emphasizing both the absolute superiority of the interest of the State in pre-revolutionary France and the confusion of public and private interests consequential to the purchase of public offices and charges with the aim to financially benefit from them, as Richelieu supposedly said ‘It is normal that ministers watch over their wealth while they watch over that of the State’ (Hirsch 2010; Mény 2013). With the development of liberal political thought, the public–private distinction created the basis on which an understanding of the possibility of conflicting public and private interests could develop. The development of modern belief systems, drawing a clearer distinction between the public and private spheres and the separation of powers, contributed to redefining corruption as the misuse of public power for private gain (Kroeze 2016). As Friedrich (2002, 22) puts it: ‘by the second half of the nineteenth century, what had been considered “normal behaviour” had become corruption’.

With the narrowing of the concept to refer to the labelling of individual deviant behaviour, allegations of political corruption became increasingly used in political competition to undermine opponents’ credibility. Combined with an increasingly mediatized public sphere and critical public opinion (Habermas 1989), the end of the nineteenth century saw the emergence of waves of scandals in Europe and America. Critical groups from both sides of the political spectrum, using corruption as a political weapon, bridged the technical and degenerative conceptions of corruption in their discourse, making the abuses of some the symptom of the moral decay of the system. As Paul Jankowski (2008, 83) writes, in early twentieth-century France, ‘corruption’ served to describe any regime that did not find public favour; ‘the myth of corruption [serving] to crystallise other free-floating fears and resentments’. The nineteenth century created a confusion between an increasingly formalized conception of corruption in law and a broader lay definition reflecting the belief in system decay that is still, to some extent, a reality today (Philp 2015). However, as Albert O. Hirschman (1997, 40) notes, from the late eighteenth century, ‘corruption’, while still referring to the deterioration in the quality of government, became increasingly likened with bribery, until ‘the monetary meaning drove the non-monetary one out almost completely’, much like ‘fortune’ according to the author. After the Second World War, the topic of corruption went through a period of relative disregard, with many European countries preoccupied with reconstruction and with the memory of the fascist discourse on corruption still ripe.Footnote 3 Corruption re-emerged as a topic of political and academic interest in the late twentieth century, when it acquired its contemporary meaning of ‘abuse of public (or entrusted) power for private gain’ (World Bank; Transparency International) and progressively became defined as a global public problem (Williams 2000).

The struggle over meaning-making

Whether considering corruption as a category of criminal offences or a broader group of unethical and/or abusive practices, scholars, practitioners and policy-makers has sought to identify common elements that define what can be considered as corruption. Controversy is still rife, leading some to argue against the need for a universal definition. As Heywood (2015, 1–2) flagged, ‘there remains a striking lack of scholarly agreement over even the most basic questions about corruption, [such as] the very definition of “corruption” as a concept’. Defining a public problem is not a neutral exercise of truth finding. It is a fundamental political process that can oppose different worldviews and that has political consequences as it categorizes people and labels practices. How one understands corruption, both conceptually (what it is) and theoretically (why is it), indeed depends on one’s (implicit or explicit) view on human nature (are certain individual corrupt by nature or do we all have a propensity for corruption), of human agency (is it individual deviance or a systemic problem) and the relation between political and economic power (how much interference between the spheres is acceptable). The cost–benefit analysis of the occurrence of corruption, inspired by Becker (1974), has largely dominated the mainstream conception of corruption since Robert Klitgaard (1998) adapted it to the issue of corruption through his now famous formula (C = M + D − A: Corruption equals monopoly plus discretion minus accountability).

The conceptual debate within academia over the last decades, summarized in Table 1 which gives an overview of the elements emphasized by different definitions, has opposed scholars who argue that it should only be used to describe the violation of legal norms or formal rules of a given public office, others for whom corruption is defined by the damage done to the public interest or to the distribution of public goods, and social constructivists who base the definition of corruption on people’s perception (Graaf 2007; Lascoumes 2010; Rothstein and Varraich 2017; Wickberg 2018).

Some academic definitions retain parts of the normative dimension of the pre-modern conception of corruption, defining it in terms of the specific damages it does. Thompson (1993) argued against an excessive focus on individual gain and characterized corruption through its impact on the working of institutions and processes. For him, the consequences matter more than intention and motives (Thompson 1993; Philp and David-Barrett 2015). Carl Friedrich (1972) and, more recently, Warren (2015) understand corruption as an abuse of power that has negative consequences on the public interest. Rothstein and Torsello (2014) proposed a ‘public goods theory’ of corruption which sees corruption as the conversion of public goods into private ones by those in charge of managing them. Similarly, Kalniņš (2014) defines corruption as the ‘particularistic (non-universal) allocation of public goods due to abuse of influence’. These definition can be considered normative in comparison with the public office definition, which has become dominant as the article will later show, since practices need to be harmful to be labelled ‘corrupt’. Corruption is indeed seen as a synonym of duplicitous exclusion or a form of unjustified partiality or injustice (Warren 2015; Rothstein and Varraich 2017).

While the definition of corruption remains an open question in academia, the ‘public office’ definition has largely won the battle among practitioners. Some elements of this definition remain up to interpretation (what does abuse mean?). Yet, the identification of corrupt practices is dependent on rules of office. In this sense, the ‘public office’ definition is certainly the easiest to operationalizable in different contexts. Taking public office as a central definitional element indeed avoids engaging in debates on public goods, the public interest or moral ideals (Bukovansky 2006; Gebel 2012; Wedel 2012). It does not presume some common understanding of public interest or what constitutes public goods (Kurer 2015). The ‘public office’ definition inspired the World Bank and Transparency International’s definitions of corruption, respectively, the ‘abuse of public office for private gain’ and the ‘abuse of entrusted power for private gain’, which are widely used in policy and academic spheres today.

Globalizing a problem and harmonizing its meaning

From being a problem internal to (certain) political systems, corruption progressively became reconceived as a global public problem in the second half of the twentieth century (Abbott 2001; Wang and Rosenau 2001; Roux 2016; Katzarova 2019). This meant firstly that practices labelled as instances of corruption evolved to include ‘trans-boundary problems’ resulting from facilitated cross-border movements of people, goods and financial flows (Soroos 1990; Glynn et al. 1997). Secondly, it meant that academics and policy actors started to conceive of corruption as a problem that existed in all countries in the world and that should be understood in a similar manner. If corruption was to be studied as a cross-border phenomenon, it needed to be defined in a manner that allowed for international comparison. Academics, most prominently economists, played a crucial role in constructing corruption as a global problem and harmonizing its meaning through quantification.

Corruption rankings, measurements and mapping played a particularly important role in putting corruption on the global agenda, making visible a phenomenon that is notoriously hard to ‘see’ (Wang and Rosenau 2001; Heywood and Rose 2014; Hellman 2019). The politics of numbers indeed proved essential in raising awareness about corruption, as is still visible in contemporary reference to estimates of costs and level of corruption. As Peter Andreas and Greenhill (2010, 1), argue ‘to measure something—or at least to claim to do so—is to announce its existence and signal its importance and policy relevance’. According to Kelley, in the global information age, rankings and measurements matter since countries worry about their reputation and pay attention when provided with ‘credible and visible information about their performance, especially if [it] makes it easy to compare them with other states or track their performance over time’ (2017, 232), turning indicators into a technology of global governance, shaping our understanding of global problems such as corruption (Cooley and Snyder 2015; Merry et al. 2015).

Quantifying corruption implies selecting, categorizing and analysing measurable information to make it tractable, countable and comparable. As Heywood and Rose (2014) argue, corruption indicators inevitably reflect particular definitions. They contain biases relative to the universe of things which could be measured. Looking at existing measurements helps us get a sense of how the battle of the numbers framed the problem, contributing to define corruption on the global stage. In a time where modernization theory was falling out of fashion, research on the economics of corruption made it necessary to develop an operational definition that caters to the needs of measurement and comparison. Rose-Ackerman (1978, 7), one of the leading figures in this field of research, provides a clear explanation of the need for ‘essentially equat[ing] corruption with bribery’. Other practices relating to corruption, such as favouritism, influence peddling or policy/state capture are indeed much harder to quantify through victimization surveys. She justifies narrowing the concept of corruption to bribery using a ‘wide range of productive research’ that focusses on ‘the piece of the broader concept most susceptible to economic analysis—monetary payments to agents’ (Rose-Ackerman 2006, xiv). The need to quantify and measure corruption certainly played an important role in the narrowing down of corruption to becoming a synonym of bribery.

In the mid-1990s, international governmental and non-governmental organizations also started to quantify corruption for the purpose of measurement and comparison. The NGO Transparency International (TI) and the World Bank were the first to develop corruption indicators. It is widely recognized that TI’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) was an important factor in the organization’s growing visibility and influence on the international stage, notably through the media attention that it came to receive each year (Wang and Rosenau 2001; Bukovansky 2015). To operationalize its governance turn, the World Bank developed its Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) in 1996, which includes an indicator on the ‘control of corruption’. Both measurement tools are composite indexes, merging indicators on the level of corruption and on existing mechanisms to prevent it. This suggests a vague definition of corruption, based on the ‘public office’ definition that they promote. TI rapidly became a mass-producer of corruption indicators, progressively diversifying its methods (turning to public opinion surveys with the Global Corruption Barometer—GCB) and focus (looking at the practices of exporting firms with the Bribe Payers’ Index—BPI). The corruption measurements developed by the World Bank and TI served the organizations’ ambition to normalize their definition of corruption (Nay 2014), inspired by the ‘public office’ definition and focussing on the practices of individual office-holders.

Corruption measurement has become a competitive market, providing the developers of successful tools with a place under the (anti-corruption) sun, attracting academic citations, research funding and visibility in policy spheres. Other organizations joined the bandwagon of corruption measurement as the problem became increasingly visible in the public debate. The Index of Public Integrity (IPI), produced by the European Research Centre for Anti-Corruption and State-Building (ERCAS) at the Hertie School of Governance, and the European Quality of Government Index (EQI), produced by the Quality of Government Institute (QoG) at the University of Gothenburg, are interesting cases. Unlike the first indicators, these measurements were developed by academic institutions who became known for being relatively critical to the international anti-corruption regime. These measurements do not fundamentally differ from TI and the World Bank’s measurement in terms of their underlying conceptualization of corruption. But they add a level of sophistication to the measurements, allowing for subnational ranking in the case of the EQI, and interpret control of corruption differently, as detailed in Table 2. More and more actors are willing to invest time and resources in developing indicators to measure corruption. This supports Diane Stone’s (2013) claim that global governance is increasingly structured around interactions between state and non-state actors, with knowledge organizations playing an increasing role. Measurement tools have become a source of cognitive authority, necessary to gain visibility in the anti-corruption community and to promote one’s conception of corruption. The methods used to measure corruption contribute to reinforce the dominant conception of corruption as a global problem and thus to shape the cognitive framework for policy-making at the national and global levels.

TI and the World Bank were instrumental in constructing corruption as a global problem, by providing a definition that they presented as non-political and thus as applicable to all polities around the world. It is not coincidental that they appropriated a concept of corruption promoted by an epistemic community seeking to render corruption measurable and comparable across borders. From designating the (fundamentally political) process of political system decay, corruption’s current mainstream definition refers to the transgression of the rules of public office. Johnston (2015, 284) summarizes the transition to our contemporary understanding of corruption as the shift from broader moral notions towards notions that ‘are by now almost exclusively, material or money-based. From there it is not a long leap to the sorts of technical and index-driven outlooks on corruption and reform that are dominant, but in some important respects unsatisfying, today’, as they ignore many forms of corruption that might be prevalent in many countries and/or considered as particularly serious in the eyes of citizens. This search for a technical definition of corruption might indeed clash with the broader, more ambiguous, use of the term in political or lay discourse (Hay 2007; Philp 2015).

Understanding what is labelled ‘corruption’

While the existence of a common definition of corruption might be necessary for measurement and comparative research, I argue that there is another side to corruption meaning-making that deserves further research. As presented in previous sections of the article, corruption is conceptually ambiguous, but it is also interpretively ambiguous—and these are not the same (Best 2008; Craig 2015; Hay 2016). Different ‘things’ can be said to be corrupt, and by labelling them as such, we confer (different) negative connotations upon them. Historians have sought to understand what phenomena and practices are or have been labelled corrupt (or ‘as corruption’), across time and space. They find that corruption has played a role in public and political discourse ever since antiquity but that its boundaries fluctuate, with the term referring to very different phenomena, practices and events (Buchan and Hill 2014; Kroeze et al. 2018). The question of which practices and phenomena feature under the label ‘corruption’ is still not resolved, as meanings coexist as seen above, and people use the terms rather differently across countries and social groups.

In ‘policy English’ (Clarke 2006), the dominant language of the anti-corruption regime, corruption refers to a category of unethical practices, which includes bribery, embezzlement, trading in influence, abuse of functions, illicit enrichment or money laundering, largely captured under the World Bank’s or TI’s definition presented above. This perspective has been translated into other languages, like Swedish, where ‘korruption’ refers to a similar category of criminal offences (Institutet mot mutor, Transparency International Sverige). France features among the exceptions, since ‘corruption’ in French refers to a specific criminal offence (articles 432-11 and 433-1 of the Criminal Code) which translates to the English ‘bribery’. The French ‘corruption’, however, also has a wider meaning (that is similar the English or Swedish terms), but the expressions ‘atteintes à la probité’ or ‘manquements au devoir de probité’ (meaning ‘violations of integrity’) are more commonly used than corruption in official discourse. Corruption might thus not always refer to the same ‘real world’ practices across borders. Corruption is, however, not defined at all in most international conventions (such as the United Nations Convention Against Corruption, the Council of Europe Criminal Law Convention on Corruption, the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption or the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption), which resolve the interpretive ambiguity of corruption through a list of practices. The United Nations did not manage to reach a consensus among member states’ different understanding of the problem (Vlassis 2004; Katzarova 2019) and saw it as a strategic choice not to define it at all, to maintain a certain interpretative leeway: ‘Notwithstanding the varying acts that may constitute corruption in different jurisdictions (…) Nothing herein shall limit the future criminalization of further acts of corruption or the adoption of measures to combat such acts’ (United Nations 2010, 43). Corruption even has porous and movable definitional boundaries within the international policy community, as this quote from the Council of Europe suggests, ‘no precise definition can be found which applies to all forms, types and degrees of corruption, or which would be acceptable universally as covering all acts which are considered in every jurisdiction as contributing to corruption’ (World Bank 1997, 20; Pearson 2013, 36).

While scholars continue to debate what a universal ‘core’ to the concept of corruption might be which could embrace all of these practices, as exposed above, many call for more contextually sensitive research on corruption to better understand the dynamics and mechanisms of the problem as it unfolds from the transnational level, with its constantly changing vehicles, to the local and sectoral level (Marquette and Peiffer 2018; Kubbe and Engelbert 2017; Kubbe and Varraich 2019; Mungiu-Pippidi and Heywood 2020; Wickberg 2020). Beyond the need for corruption research to rethink its focus, I argue that scholars should take the ambiguous dimension of the problem seriously and seek to understand how different social groups within and across societies resolve the interpretive ambiguity of corruption.

Early scholarship on corruption used constructivist and sociological frameworks to understand citizens’ attitude to corruption, concluding that acceptance or rejection of corruption varies significantly across social groups, depending on contexts and prevalent social norms (Gardiner 1970; Heidenheimer 1970; Peters and Welch 1978; Heidenheimer et al. 1989). This bottom-up approach to the study of corruption more recently inspired Pierre Lascoumes (2010) to analyse French citizens’ attitudes towards the problem. These seminal studies deserve to be explored anew, to better understand how corruption can continue to mean different things to different people, social and professional groups and in different contexts, despite international efforts to diffuse and harmonize anti-corruption policy since the 1990s. In a time of rising populism and anti-politics sentiments I suggest that beyond attitudes to corruption, it is the very understanding(s) and uses of the term ‘corruption’ that ought to be further explored.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the attribution of the term ‘corruption’ to certain practices varies depending on political/partizan preferences and geographical or linguistic differences. The scandal involving François Fillon, then candidate to the French presidency, during the 2017 campaign is revealing in this regard: his fellow Républicains presenting the situation as a political move by the opposition to destabilize their candidate, while opponents or foreign media more easily labelled it ‘corruption’ (Lefebvre 2017; Pecnard 2017; Zaretysky 2017; Europe 1 2017; Belouezzane 2020). Academic research also shows that, despite overwhelmingly rejecting corruption—at least in theory, the public does not hold a conceptually monolithic view of corruption (Rose 2018; Navot and Beeri 2018). These studies start from the assumption people might agree on a common conceptual core in the abstract, but that disagreements will emerge regarding how the term is applied, its application to concrete cases and to the conceptual boundaries (Atkinson and Mancuso 1985; Philp 1997; Johnston 2014; Navot and Beeri 2018). Navot and Beeri (2018), for instance, reintroduce the use of scenarios—utilized by earlier studies presented above—to measure the conceptualizations and conceptions of political corruption held by the Israeli population. Their study offers a new tool to elucidate public understanding of corruption, which ought to be used by scholars in other countries and regions to get valuable insights regarding the link between conceptions of corruption and perception of the problem. Feminist scholarship also finds significant differences between how women and men perceive corruption, with regard to both levels and types. Women are usually found to be less tolerant to corruption than men (Sineau 2010; Torgler 2010), to be less likely to engage in corruption (Barnes 2018) and to sometimes be held to higher standards (Eggers 2018). Research also shows that, partly due to their social role and exclusion from spheres of power, women are not sensitive to the same types of corruption, perceiving higher levels of ‘need corruption’ (to access public services) than ‘greed corruption’ (to access undue privileges) (Bauhr and Charron 2020). This difference in conception is also a result of women being exposed to other forms of abuse than men, such as sexual extortion, making corruption more than a monetary transaction (Loli and Kubbe forthcoming).

Beyond scenario-based research, I suggest that we need more research regarding the concrete use of the term corruption by citizens, political organizations, the media, in both writing and orally, online and ‘in real life’. Indeed, while the mainstream conception of corruption in international policy and academic circles was largely shaped by international organizations involved in the fight against corruption, it is far from certain that citizens share this expert view on what corruption is and what it refers to. As Philp (2015, 18–19) points out, ‘because it is a widely used category of social meaning with powerful negative connotations, (…) technical and professional use of the term often clashes with the meanings which are ascribed to it by ordinary people, politicians and public servants, the media and commentators, each of whom may have different concerns and different interests in identifying certain types of conduct as corrupt’. As the problem of corruption becomes increasingly politicized, in populist and conspiracy-leaning discourse but not only, this research agenda could trace the evolution(s) of the use of the term, the construction of these various uses within and between groups and countries, and seek to understand the reasons and strategies used by actors to mobilize this normative concept for political (or other) reasons.

Considering corruption as a social and historical construct, and recognizing that the term can indeed mean different things to different people, social groups and in different national contexts encourages scholars to seek to elucidate its various conceptions by studying the situated use of the term (Schaffer 2016). Such a research agenda should further our understanding of how corruption was constructed and defined as a public problem in different contexts, following existing research showing how the definition of corruption adapted to serve powerful actors on the global stage, to denounce certain practices (more prevalent in the developing or transitioning countries) or to further the agenda of international financial institutions (Krastev 2004; Harrison 2006; Sousa et al. 2009; Tänzler et al. 2012; Wedel 2012; Jakobi 2013; Bratu and Kažoka 2018; Katzarova 2019; Wickberg 2020). This is indeed not unexplored terrain nor is it a novel idea. Michael Johnston (1996) argued three decades ago, while debates on the definition of corruption were raging, that there was also a need to pay attention to the political conflicts shaping the idea of corruption. Yet only few studies have faced this challenged, beyond the issue of attitudes towards corruption (see for instance Koechlin 2013; Huss 2018; Engler 2020; Berti et al. 2020 for an overview of studies on the media framing of corruption). Both case studies and comparative research are needed, to understand different interpretations of corruption within and across (sub-)national borders—between different social groups and between policy-makers (who are often both the initiators and the target audience of anti-corruption policy), politicians (including those with a populist-leaning), business and interests’ representatives, activists, the media and ordinary citizens—as well as the factors that might explain similarities and differences. Applying a comparative approach to this constructivist agenda would shed light on different social groups’ use and conception of the term across borders, and identify where conceptions converge or differ. A multitude of research methods could be used to contribute to this research agenda, from discourse analysis, in-depth interviews, focus groups or participant observation to quantitative text analysis and surveys.

This constructivist research agenda should not be perceived as a means to further fuel the debate between a universalistic and a relativistic approach to corruption. Rather, I argue that elucidating the expert, political and everyday uses of the term, and doing so comparatively, would greatly serve both the academic and policy community. Indeed, divergence in conceptions of the problem (with and across societies) might be an underestimated factor explaining the failure of anti-corruption policy (Persson et al. 2013; Marquette and Peiffer 2018). It might also generate gridlocks in international cooperation, as has been the case in the European Union for instance. Despite the multiplication of initiatives against corruption, we have not gotten rid of it. The discourse of the policy community has even evolved, from reflecting the ambition to eliminate the problem to the more modest project of managing its risks, and the efforts of global actors and international organizations to depoliticize the problem have rendered anti-corruption efforts increasingly technocratic and uniform (Wickberg 2020). A better understanding of the different ways social groups’ conceive of corruption could push scholars and policy-makers to re-politicize the problem and better consider existing (local, national or global) power structures in their reflexion on the mechanisms of corruption and the development of solutions (Philp and David-Barrett 2015; Heywood 2015; Marquette and Peiffer 2018). (Re)applying a constructivist perspective to the study of corruption could also shed light as to how the meaning(s) and use(s) of the term evolves in the face of changes in global political economy, power structures, new means of communication, etc. While scholars called for such a turn already in the 1990s (Johnston 1996), the recent rise of populist discourse, anti-politics sentiment, post-truth, conspiracy theories and illiberal democracy, coupled with the emergence of new media and technology, make this endeavour all the more relevant, as corruption becomes increasingly politicized and instrumentalized (Mungiu-Pippidi and Heywood 2020).

Conclusion

This article has demonstrated how the existing literature confirms that corruption has been and remains an essentially contested concept, an ambiguous term which can be understood in different ways and sustain a variety of competing narratives. While the meaning of corruption progressively narrowed from its ‘degenerative conception’, associated with moral, spiritual but also political decay, to a ‘social-scientific conception of corruption’, referring to specific forms of individual abuse of power, the contemporary understanding of the term is still a matter of scholarly disputes. The development of an international anti-corruption regime and policy community made it necessary to develop a common definition of corruption allowing for the elaboration of global solutions and common policy instruments. Similarly, measuring corruption and studying it as a global phenomenon required a conception of the problem that allowed for international comparison. One of the consequences of the globalization of the anti-corruption agenda was the purging of the political dimension from the idea of corruption, turning it into an issue of (wrong) incentives, by its conceptual architects, the World Bank and Transparency International.

In this article, I argue that it is necessary for corruption research to diversify its analytical lenses and reconsider the constructivist perspective developed by some of the pioneers of this scholarship, adapting it to the new challenges of the twenty-first century. Having stripped corruption of its intrinsically political dimension, it might just be timely to bring politics back in and reconsider the contentious nature of the development and evolution of the terms’ meaning, at the interplay of formal institutions and socio-political forces, of global and local dynamics. This approach could be relevant beyond corruption research, as there is value in paying closer attention to the construction of numerous normative concepts mobilized for political reasons, such as democracy, human rights, modernization, populism or crisis (Oren 2002; Guilhot 2005; Gregg 2011; Voltolini et al. 2020). As critical and feminist work on concepts suggests, it is necessary for social sciences to consider concepts, such as corruption, as a product of context and power struggles, and to bring meaning-making back to the core of our analysis of politics (Mazur 2020). I propose a research agenda that takes the ambiguity of corruption seriously and thus seeks to elucidate how people in different social groups, professional spheres and geographical locations resolve this interpretive ambiguity, and to understand where similarities and differences in conceptions of corruption stem from. As Mason (2020) recently wrote: ‘there has been no shortage of thinking done about corruption’, and we live in a world rich of research, expertise and policy innovations targeting the intractable problem of corruption. Far from undermining this valuable work, the approach presented in this article offers to look at the problem from a different angle, to shed light on the practices that are currently omitted from mainstream understandings of corruption and on the social and political dynamics and conflicts that shape it as a social issue and as a policy problem.

Notes

Author’s own translation.

Interestingly, in French, ‘corruption’ also refers to the sexual abuse of youth, reflecting the original polysemy.

Professor of History, Technische Universität Darmstadt (INTEX1). Interview, with author. November 17th 2016.

References

Abbott, K. 2001. Rule-making in the WTO: Lessons from the Ce of Bribery and Corruption. Journal of International Economic Law 4(2): 275–296.

Affaire Penelope Fillon: Plusieurs centaines de manifestants à Paris “contre la corruption des élus” Europe 1, February 19th 2017. https://www.europe1.fr/societe/affaire-penelope-fillon-plusieurs-centaines-de-manifestants-a-paris-contre-la-corruption-des-elus-2982434. Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

Alatas, H.S. 1968. The Sociology of Corruption: The Nature, Function, Causes and Prevention of Corruption. Singapore: D. Moore Press.

Andreas, P., and K.M. Greenhill. 2010. Sex, Drugs, and Body counts: The Politics of Numbers in Global Crime and Conflict. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Atkinson, M.M., and M. Mancuso. 1985. Do we Need a Code of Conduct for Politicians? The Search for an Elite Political Culture of Corruption in Canada. Canadian Journal of Political Science 18(3): 459–480.

Barnes, B. 2018. Women Politicians, Institutions, and Perceptions of Corruption. Comparative Political Studies 52(1): 134–167.

Bauhr, M., and N. Charron. 2020. Do Men and Women Perceive Corruption Differently? Gender Differences in Perception of Need and Greed Corruption. Politics and Governance 8(2): 92–102.

Becker G. S. 1974. Essays in the Economics of Crime and Punishment. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research: distributed by Columbia University Press.

Belouezzane, S. 2020. Affaire Fillon: Les Républicains «choqués»par les déclarations de l’ex-chef du Parquet national financier. Le Monde, June 22, 2020. https://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2020/06/22/les-republicains-choques-par-les-declarations-de-l-ex-cheffe-du-parquet-national-financier-sur-l-affaire-fillon_6043676_823448.html. Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

Berti, C., R. Bratu, and S. Wickberg. 2020. Corruption and the Media. In A Research Agenda for Studies of Corruption, ed. A. Mungiu-Pippidi and P. Heywood. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Best, J. 2008. Ambiguity, Uncertainty, and Risk: Rethinking Indeterminacy. International Political Sociology 2(4): 355–374.

Boccon-Gibod, T. Forthcoming. De la corruption des régimes à la confusion des intérêts: pour une histoire politique de la corruption. Revue française d’administration publique 145.

Bratu, R., and I. Kažoka. 2018. Metaphors of Corruption in the News Media Coverage of Seven European Countries. European Journal of Communication 33(1): 57–72.

Buchan, B., and L. Hill. 2014. An Intellectual History of Political Corruption. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Bukovansky, M. 2006. The Hollowness of Anti-corruption Discourse. Review of International Political Economy 13(2): 181–209.

Centre national des ressources textuelles et lexicales. n.d. Corruption. https://www.cnrtl.fr/definition/corruption. Accessed 5 Mar 2020.

Clarke, J. 2006. What’s Culture Got to Do with It? Deconstructing Welfare, State and Nation. Working Paper n° 136-06, Centre for Cultural Research, University of Aarhus.

Clarke, N., W. Jennings, J. Moss, and G. Stoker. 2018. The Good Politician: Folk Theories, Political Interaction, and the Rise of Anti-politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cooley, A., and J. Snyder (eds.). 2015. Ranking the World: Grading States as a Tool of Global Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Craig, M. 2015. Post-2008 British Industrial Policy and Constructivist Political Economy: New Directions and New Tensions. New Political Economy 20(1): 107–125.

Eggers, V. 2018. Corruption, Accountability, and Gender: Do Female Politicians Face Higher Standards in Public Life? The Journal of politics 80(1): 321–326.

Engler, S. 2020. “Fighting Corruption” or “Fighting the Corrupt Elite”? Politicizing Corruption Within and Beyond the Populist Divide. Democratization 27(4): 643–661.

Europe 1. Affaire Penelope Fillon: Plusieurs centaines de manifestants à Paris “contre la corruption des élus”. February 19th 2017. Online, available at: https://www.europe1.fr/societe/affaire-penelope-fillon-plusieurs-centaines-de-manifestants-a-paris-contre-la-corruption-des-elus-2982434 Accessed 3 Jan 2021.

Fawcett, P., M. Flinders, C. Hay, and M. Wood (eds.). 2017. Anti-politics, Depoliticisation and Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Friedrich, C. 1972. The Pathology of Politics: Violence, Betrayal, Corruption, Secrecy and Propaganda. New York: Harper and Row.

Friedrich, C. 2002. Corruption Concepts in Historical Perspective. In Political Corruption: Concepts & Contexts. 3rd ed, ed. A.J. Heidenheimer and M. Johnston. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Gallie, W. B. 1956. IX.—Essentially Contested Concepts. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 56(1): 167–198.

Gardiner, J.A. 1970. The Politics of Corruption. Organised Crime in an American City. New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

Gebel, A.C. 2012. Human Nature and Morality in the Anti-corruption Discourse of Transparency International. Public Administration and Development 32: 109–128.

Génaux, M. 2002. Les mots de la corruption: la déviance publique dans les dictionnaires d’Ancien Régime. Histoire, économie et société 21(4): 513–530.

Génaux, M. 2004. Social Sciences and the Evolving Concept of Corruption. Crime, Law and Social Change 42(13): 13–24.

Gledhill, J. 2004. Corruption as the Mirror of the State in Latin America. In Between Morality and the Law: Corruption, Anthropology and Comparative Society, ed. I. Pardo. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

Glynn, P., S.J. Kobrin, and M. Naìm. 1997. The Globalization of Corruption. In Corruption and the Global Economy, ed. K.A. Elliott. Washington, D.C: Institute of International Economics.

Graaf, G. 2007. Causes of Corruption: Towards a Contextual Theory of Corruption. Public administration quarterly 31(1/2): 39–86.

Gregg, B. 2011. Human Rights as Social Construction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guilhot, N. 2005. The Democracy Makers: Human Rights and International Order. New York: Columbia University Press.

Habermas, J. 1989. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Harrison, E. 2006. Unpacking the Anti-corruption Agenda: Dilemmas for Anthropologists. Oxford Development Studies 34(1): 15–29.

Hay, C. 2007. Why We Hate Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hay, C. 2016. Good in a Crisis: The Ontological Institutionalism of Social Constructivism. New Political Economy 21(6): 520–535.

Heeks, R., and H. Mathisen. 2012. Understanding Success and Failure of Anti-corruption Initiatives. Journal of Crime, Law and Social Change 58(5): 533–549.

Heidenheimer, A.J. 1970. Political Corruption: Readings in Comparative Analysis. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Heidenheimer, Arnold J., and Michael Johnston. 2002. Political Corruption: Concepts & Contexts. 3rd ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Heidenheimer, A.J., M. Johnston, and V.T. Levine (eds.). 1989. Handbook of Corruption. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Hellman, O. 2019. The Visual Politics of Corruption. Third World Quarterly 40(12): 2129–2152.

Heywood, P. 2015. Introduction Scale and Focus in the Study of Corruption. In Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption, ed. P. Heywood. Abingdon: Routledge.

Heywood, P. 2017. Rethinking Corruption. Hocus–Pocus, Locus and Focus. The Slavonic and East European Review 95(1): 21–48.

Heywood, P. 2019. 7—Paul Heywood on Which Questions to Ask to Gain New Insights into the Wicked Problem of Corruption. Kickback the Global Anticorruption Podcast. https://soundcloud.com/kickback-gap/7-episode-paul-heywood. Accessed 5 Nov 2020.

Heywood, P., and J. Rose. 2014. “Close But No Cigar”: The Measurement of Corruption. Journal of Public Policy 34(3): 507–529.

Hirsch, M. 2010. Pour en finir: avec les conflits d’intérêt. Paris: Stock.

Hirschman, A.O. 1997. The Passions and the Interests Political Arguments for Capitalism Before its Triumph. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hough, D. 2013. Corruption, Anti-corruption and Governance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Huss, O. 2018. Corruption, Crisis, and Change: Use and Misuse of an Empty Signifier. In Crisis and Change in Post-Cold War Global Politics, ed. E. Resende, D. Budrytė, and D. Buhari-Gulmez. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Institutet mot mutor. n.d. Brottsbalken. Official website. https://www.institutetmotmutor.se/regelverk/det-svenska-regelverket/brottsbalken/. Accessed 20 Jan 2020.

Jakobi, A.P. 2013. The Changing Global norm of Anti-corruption: From Bad Business to Bad Government. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 7(1): 243–264.

Jankowski, P. 2008. Shades of Indignation: Political Scandals in France, Past and Present. New York: Berghahn Books.

Johnston, M. 1996. The Search for Definitions: The Vitality of Politics and the Issue of Corruption. International Social Science Journal 48(149): 321–335.

Johnston, M. 2014. Corruption, Contention, and Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnston, M. 2015. Reflection and Reassessment. The Emerging Agenda of Corruption Research. In Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption, ed. P. Heywood. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kalniņš, V. 2014. Anti-corruption Policies Revisited: D3.2.8. Background paper on Latvia. In Corruption and Governance Improvement in Global and Continental Perspectives, ed. A. Mungiu-Pippidi. Gothenburg: ANTICORRP.

Katzarova, E. 2019. The Social Construction of Global Corruption: from Utopia to Neoliberalism. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kelley, J.G. 2017. Scorecard Diplomacy Grading States to Influence Their Reputation and Behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klein, N. 2014. This Changes Everything. New York City: Simon & Schuster.

Klitgaard, R. 1998. International Cooperation Against Corruption. Finance & Development 35(1): 3–6.

Knights, M. 2018. Explaining Away Corruption in Pre-modern Britain. Social Philosophy and Policy 35(2): 94–117.

Koechlin, L. 2013. Corruption as an Empty Signifier. Politics and Political Order in Africa. Leiden: Brill.

Krastev, I. 2004. Shifting Obsessions: Three Essays on the Politics of Anticorruption. New York: Central European University Press.

Kroeze, R. 2016. The Rediscovery of Corruption in Western Democracies. In Corruption and Governmental Legitimacy: A Twenty-First Century Perspective, ed. J. Mendilow and I. Peleg. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Kroeze, R., A. Vitória, and G. Geltner (eds.). 2018. Anticorruption in History: From Antiquity to the Modern era. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kubbe, I., and A. Engelbert (eds.). 2017. Corruption and Norms: Why Informal Rules Matter. London: Palgrave Macmillan Political Corruption and Governance Series.

Kubbe, I., and A. Varraich (eds.). 2019. Corruption and Informal Practices in the Middle East and North Africa. Abingdon, New York: Routledge Corruption and Anti-Corruption Studies.

Kurer, O. 2015. Definitions of Corruption. In Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption, ed. P. Heywood. Abingdon: Routledge.

Lascoumes, P. 2010. Favoritisme et corruption à la française Petits arrangements avec la probité. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Ledeneva, Alena. 2008. Blat and Guanxi: Informal Practices in Russia and China. Comparative Studies in Society and History 50(1): 118–144.

Lefebvre, B. 2017. Rétro 2017. Fillon, une campagne placée sous le signe de la corruption. NPA Revolution permanente, December 28th 2017. https://www.revolutionpermanente.fr/Retro-2017-Fillon-une-campagne-placee-sous-le-signe-de-la-corruption. Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

Loli, M., and I. Kubbe. Forthcoming. Add Women and Stir? The Myths About the Gendered Dimension of Anti-corruption. European Journal of Gender Politics.

Marquette, H., and C. Peiffer. 2018. Grappling with the “Real Politics” of Systemic Corruption: Theoretical Debates Versus “Real-World” Functions. Governance 31: 499–514.

Mason, P. 2020. Twenty Years with Anticorruption. Part 4 Evidence on Anti-corruption—The Struggle to Understand What Works. U4 Practitioner Experience Note 2020:4. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute.

Mazur, A.G. 2020. Feminist Approaches to Concepts and Conceptualization Toward Better Science and Policy. In Handbook of Feminist Philosophy of Science, ed. S. Crasnow and K. Intemann. Oxford: Routledge.

Mendilow, J., and E. Phélippeau (eds.). 2019. Political corruption in a world in transition. Wilmington, Delaware: Vernon Press.

Mény, Y. 2013. De la confusion des intérêts au conflit d’intérêts. Pouvoirs 147: 5–15.

Merry, S.E., K.E. Davis, and B. Kingsbury. 2015. The Quiet Power of Indicators: Measuring Governance, Corruption, and the Rule of Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Monier, F. 2016. La corruption, fille de la modernité politique? Revue internationale et stratégique 1(101): 63–75.

Mungiu-Pippidi, A., and P. Heywood (eds.). 2020. A Research Agenda for Studies of Corruption. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Naìm, M. 1995. The Corruption Eruption. The Brown Journal of World Affairs 2(2): 245–261.

Navot, D., and I. Beeri. 2018. The Public’s Conception of Political Corruption: A New Measurement Tool and Preliminary Findings. European Political Science 17(1): 1–18.

Nay, O. 2014. International Organisations and the Production of Hegemonic Knowledge: How the World Bank and the OECD Helped Invent the Fragile State Concept. Third World Quarterly 35(2): 210–231.

Nye, J. 1967. Corruption and Political Development: A Cost-Benefit Analysis. The American Political Science Review 61(2): 417–427.

OECD. 2017. Terrorism, Corruption and the Criminal Exploitation of Natural Resources. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Oren, I. 2002. Our Enemies and US: America’s Rivalries and the Making of Political Science. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Pearson, Z. 2013. An International Human Rights Approach to Corruption. In Corruption and Anti-Corruption, ed. P. Larmour and N. Wolanin. Canberra: Asia Pacific Press.

Pecnard, J. 2017. Présidentielle: rechute de complotisme aigu dans l’équipe Fillon. L’Express, March 23rd 2017. https://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/politique/elections/presidentielle-rechute-de-complotisme-aigu-dans-l-equipe-fillon_1891811.html. Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

Persson, A., B. Rothstein, and J. Teorell. 2013. Why Anticorruption Reforms Fail: Systemic Corruption as a Collective Action Problem. Governance 26(3): 449–471.

Peters, J.G., and S. Welch. 1978. Political Corruption in America: A Search for Definitions and a Theory, or If Political Corruption is in the Mainstream of American Politics Why is it Not in the Mainstream of American Politics Research? The American Political Science Review 72(3): 972–984.

Philp, M. 1997. Defining Political Corruption. Political Studies 45(3): 436–462.

Philp, M. 2015. The Definition of Political Corruption. In Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption, ed. P. Heywood. Oxford: Routledge.

Philp, M., and E. David-Barrett. 2015. Realism About Political Corruption. Annual Review of Political Science 18: 387–402.

Quah, Jon S.T. 2008. Curbing Corruption in India: An Impossible Dream? Asian Journal of Political Science 16(3): 240–259.

Rittel, H.W.J., and M.M. Webber. 1973. Dilemmas in the General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences 4: 155–169.

Rose, J. 2018. The Meaning of Corruption: Testing the Coherence and Adequacy of Corruption Definitions. Public Integrity 20(3): 220–233.

Rose-Ackerman, S. 1978. The Economics of Corruption: A Study in Political Economy. New York: Academic Press.

Rose-Ackerman, S. 1999. Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences, and Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (ed.). 2006. International Handbook on the Economics of Corruption. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Rothstein, B., and D. Torsello. 2014. Bribery in Preindustrial Societies: Understanding the Universalism-Particularism Puzzle. Journal of Anthropological Research 70(2): 263–284.

Rothstein, B., and A. Varraich. 2017. Making Sense of Corruption. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roux, A. 2016. La corruption internationale: essai sur la répression d’un phénomène transnational. Ph.D. thesis defended on December 7th 2016 at the University of Aix-Marseille.

Schaffer, F.C. 2016. Elucidating Social Science Concepts: An Interpretivist Guide. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Sineau, M. 2010. Chapitre 6/Genre et corruption: des perceptions différenciées. In Favoritisme et corruption à la française. Petits arrangements avec la probité, ed. P. Lascoumes, 187–198. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Soroos, M.S. 1990. A Theoretical Framework for Global Policy Studies. International Political Science Review 11(3): 309–322.

Sousa, L., P. Larmour, and B. Hindess. 2009. Governments, NGOs and Anti-corruption: The New Integrity Warriors. New York, NY: Routledge.

Steingrüber, S., M. Kirya, D. Jackson, and S. Mullard. 2020. Corruption in the Time of COVID-19: A Double-Threat for Low Income Countries. U4 Brief 2020:6. Bergen: Michelsen Institute.

Stone, D. 2013. Knowledge Actors and Transnational Governance. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tänzler D., Maras, K. 2012. The Social Construction of Corruption in Europe. Farnham Burlington, Vt: Ashgate.

Thompson, D.F. 1993. Mediated Corruption: The Case of the Keating Five. American Political Science Review 8(2): 369–381.

Torgler, V. 2010. Gender and Public Attitudes Toward Corruption and Tax Evasion. Contemporary Economic Policy 28(4): 554–568.

Transparency International. n.d. How Do You Define Corruption? Official website. https://www.transparency.org/what-is-corruption#define. Accessed 5 Mar 2020.

Transparency International Sverige. n.d. Vad är korruption? Official website. https://www.transparency.se/korruption. Accessed 20 Jan 2020.

United Nations. 2010. Travaux Préparatoires of the negotiations for the elaboration of the United Nations Convention against Corruption. Vienna: United Nations Office.

United Nations. 2020. Covid-19: l’ONU appelle à combattre la corruption qui prend de nouvelles forms. ONU Info. https://news.un.org/fr/story/2020/10/1079882. Accessed 10 Nov 2020.

Vlassis, D. 2004. The United Nations Convention Against Corruption: Origins and Negotiation Process. Resource Material Series 66: 126–131.

Voltolini, B., M. Natorski, and C. Hay. 2020. Introduction: The Politicisation of Permanent Crisis in Europe. Journal of European Integration 42(5): 609–624.

Wang, H., and J.N. Rosenau. 2001. Transparency International and Corruption as an Issue of Global Governance. Global Governance 7(1): 25–49.

Warren, M.E. 2015. The Meaning of Corruption in Democracies. In Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption, ed. P. Heywood. Oxford: Routledge.

Wedel, J.R. 2012. Rethinking Corruption in an Age of Ambiguity. The Annual Review of Law and Social Science 8(1): 453–498.

Wickberg, S. 2018. Corruption. In Dictionnaire d’économie politique, ed. A. Smith and C. Hay. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Wickberg, S. 2020. Global Instruments, Local Practices. Understanding the ‘Divergent Convergence’ of Anti-corruption Policy in Europe. Ph.D. Thesis, defended on July 2d 2020. Paris: Sciences Po.

Williams, R. (ed.). 2000. The Politics of Corruption 1, Explaining Corruption. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

World Bank. 1997. Helping Countries Combat Corruption The Role of the World Bank. Poverty Reduction and Economic Management. Washington DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2020. Combating Corruption. Official Website. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/governance/brief/anti-corruption. Accessed 10 Nov 2020.

Zaretysky, R. 2017. Why is France so Corrupt? Foreign Policy, February 1st 2017. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/02/01/why-is-france-so-corrupt-fillon-macron-le-pen/. Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wickberg, S. Understanding corruption in the twenty-first century: towards a new constructivist research agenda. Fr Polit 19, 82–102 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-020-00144-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-020-00144-4