Abstract

The housing market is one of the most cyclical parts of the U.S. economy and played a leading role in the Great Recession. While house prices have recovered, the extent of the recovery varies considerably across markets. We evaluate housing prices in 20 MSAs and find that 12 out of them show a consistent pattern of behavior relative to the nation, while eight cities’ house price indices (HPIs) are characterized as having inconsistent behavior. Our analysis found breaks in the time series behavior of all HPIs. Furthermore, some MSAs, such as New York and Miami, began to recover much sooner than others. Granger causality test results suggest that some MSAs lead the national average and most of the other MSAs. Thus, our study suggests that changes in housing prices in a number of MSAs would provide an early warning for price moves at the national and regional levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The housing market played a leading role in the Great Recession. While house prices have recovered from their collapse, the extent of the recovery varies considerably across markets. Our study analyzes house price movements across different markets.

First, we assess home prices in 20 MSAs and determine where each market currently stands relative to the national housing recovery and its own historic metrics. Second, we determine if the time series of house prices in the nation and in the MSAs have shifted. We finally test to determine which MSAs tend to lead and lag the national market.

Our view is that region-specific analysis of this type can provide a more complete picture of the state of the housing market than can come from a sole focus on the national figures. Activities in some regions can permeate through to the overall economy. A great illustration is the recent experience. The housing boom was initially thought to be a regional phenomenon that did not pose a serious risk to the national economy. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) transcripts from this period show that at first the FOMC considered there to be isolated regional housing bubbles. Likewise, by 2006, the meeting transcripts show that Ben Bernanke, the Federal Reserve Board’s Chairman at the time, discussed that falling home prices might not derail economic growth.Footnote 1

We examine housing price moves in three ways: (1) straightforward examination of graphs comparing MSA and national prices. (2) State space analysis to determine structural breaks in the time series. (3) Granger causality tests to identify MSAs that lead and lag national prices and prices in other MSAs.

2 Not all booms/busts are created equally: a graphical review

We use the S&P CoreLogic Case–Shiller home price index (CoreLogic HPI) as a measure of home prices. Our set uses three aggregate measures [the national HPI, 20-City HPI (20 major MSAs), 10-City HPI (ten major MSAs)] and individual HPIs for the 20 major MSAs. Houses are a heterogeneous asset class, and they are unique because of location and physical attributes, while sales, or turnover, is typically infrequent. By the same token, house price behavior varies across different MSAs as some MSAs attract large numbers of foreign buyers (such as Miami and New York), while other markets draw mostly domestic buyers (with good examples being Cleveland and Minneapolis). The pace of the economic recovery of an MSA/state is also an important determinant of home prices. Therefore, multiple factors are responsible for the pace of home price movements in different MSAs.

The pace/magnitude of the housing boom/bust was far from identical for all MSAs.Footnote 2 For example, the peak level for some MSAs was significantly higher/lower than the national HPI’s peak. By the same token, declines (as measured from peak to trough) in certain MSAs were significantly larger than the national HPI drop. There were some MSAs that experienced a much smaller increase, compared to the national HPI, during the boom period but significantly larger peak-to-trough declines than the national HPI. Over the 2002–2006 period, the national HPI increased by 57.4%, while the increase in Miami was 125.5%, 122.3% in Los Angeles, and 103.7% in Las Vegas. At the other end of the spectrum, Detroit saw the smallest gain of 7.4%, Dallas was up 10.7%, and Cleveland grew 12.6%.

The national HPI dropped by 21.5% over the 2007–2012 period. The largest drop was for the Las Vegas market (55.8%) followed by Miami (45.8%) and Phoenix (43.4%). Denver enjoyed the smallest drop of 2.2% with Dallas down only 2.6%. Note that Las Vegas and Miami experienced the largest drops, after enjoying the largest increases during the boom period. Similarly, Denver and Dallas were among the smallest gainers followed by smaller drops during the bust period. There are some exceptions to the conventional wisdom of the larger the gain, the deeper the drop. For example, Detroit’s gain of just 7.4% was the smallest during the boom period, but its 32.1% peak-to-trough decline was larger than the national drop. Other examples of MSAs experiencing below-average HPI growth during the boom period but larger than average HPI declines during the subsequent bust include Chicago (−32.8%), Atlanta (−28.4%), and Minneapolis (−25.4%).

Growth in national and regional HPIs has since continued to vary. For example, in 2013–2016 the national HPI increased by 28.7% and the “usual suspects” (Las Vegas, Miami, and Los Angeles) have outperformed that pace. There are some “unusual suspects” in this recovery, as San Francisco reported the largest gain of 56.1%, followed by Portland (47.1%).The smallest gain was Cleveland’s 12.1%.

The unusual markets during 2013–2016 recovery were Denver (up 41.4%), Dallas (up 40%), Atlanta (up 39.1%), and Detroit (up 35.6%), as these MSAs were among the slowest markets for home price appreciation during the 2002–2006 period. Interestingly, New York’s gain was the second lowest (14.1%) with the D.C. MSA having the third smallest gain of 15.6%—both of these MSAs enjoyed faster house price appreciation than the national average during the 2002–2006 period.

The notable divergence in price behavior across regional housing markets during the 2002–2006 boom period suggests that regional/MSA level analysis is crucial in evaluating the true state of the U.S. housing market.

2.1 “A picture is worth a thousand words:” let the data speak for the housing recovery

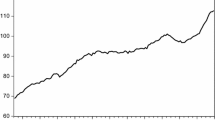

We now turn to a more systematic analysis of the numbers, starting with a look at graphical representations of housing price indices. We set all HPI values in January 2000 = 100. We utilize the national HPI as a benchmark to analyze each MSA. We then look at the relative movements of an MSA’s line with that for the nation to characterize and MSA’s HPI as “consistent” or “inconsistent.” We designate an MSA’s HPI as “consistent” if it stays above/below the national HPI line, otherwise it exhibits “inconsistent” behavior. If an MSA HPI stays above the national HPI line then the MSA’s home values consistently appreciate faster than the national average value. On the other hand, if an MSA’s HPI stays below the national HPI line, then home values in that MSA consistently increase at a slower pace than the national average. Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, and 20 compare the HPI for each MSA with the 10-City, 20-City, and national measures.

The figures show that the 10-City HPI outperformed both the national and 20-City HPIs. The 20-City HPI had either higher or the same growth rate as the national HPI. 12 out of 20 MSA HPIs show a consistent behavior (either stay above or below the national HPI line in the sample period) and eight HPIs are characterized as having inconsistent behavior. Among the consistent behavior HPIs, 5 MSAs outperformed (stayed above) the national HPI; those are D.C., Los Angeles, Miami, New York, and San Diego.Footnote 3 The remaining seven MSAs with consistent behavior that stayed below (underperformed) the national HPI line are Atlanta, Charlotte, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Denver, and Detroit.

Among the eight MSAs with inconsistent behavior (different behavior for different time periods in our sample), Tampa outperformed national HPI growth up until 2008, and then underperformed until 2015, with a recent catch up to the national HPI line. The Minneapolis MSA HPI started strong (above the national HPI line), but dropped below the national line in 2005 and has remained there to the present. The Portland and Seattle MSA HPI lines started below the national HPI and stayed there until 2007. They then exhibited similar growth as the national HPI during the 2007–2014 period and have since outperformed the national rate. The HPI lines for San Francisco and Boston started out above the national HPI, then dropped below, only to outperform the national HPI most recently; San Francisco has been especially strong in the last couple of years. The Las Vegas and Phoenix HPI lines show similar (inconsistent) behavior as they both started below the national HPI and then outperformed the national index during 2004–2006. Both MSA’s HPI lines have underperformed the national HPI index since the Great Recession.

Summing up, our first method suggests that the pace of the housing recovery varies across housing markets. Furthermore, certain MSA’s HPI behavior is inconsistent compared to the national HPI and that suggests that we should not assume that the past performance of an MSA’s HPI relative to the nation will be repeated in the future.

3 A structural break and the housing recovery: an econometric setup

The graphical method suggests that MSA HPI behavior varies across geographical markets and exhibits different behavior over time. The Las Vegas HPI is a good example of a market changing behavior over time. Its HPI grew noticeably more than the national HPI during 2004–2007, and then well below the national HPI line in the post Great Recession era. A statistically significant change in a variable’s behavior over time is known as a structural break. In the next step, we test whether the understudy HPIs experience is a statistically significant structural break.

If we find a structural break, say in the national HPI, and the coefficient of interest is positive, then that would indicate that the HPI has shifted higher (a higher pace of growth) since the break date. If the break coefficient is negative, then that means a lower (or negative) growth zone. If there is no break, then the HPI behavior is stable over time.

We utilize the state space approach to detect a structural break in the national and MSA indices.Footnote 4 There are three possible changes in the behavior of an index: additive outliers (AO), level shifts (LS), and temporary changes (TC). Additive outliers indicate that one (or more) observations are very different (or far away) from the rest of the observations. Level shifts (true structural breaks) show a variable has two or more different structures—in the present case an HPI may have shifted upward (if the coefficient is positive) or downward (a negative coefficient). A temporary change (TC) is a change in a variable for fixed period before it returns to its previous level.

The structural break results are reported in Table 1. The results indicate breaks in the national HPI series in 2007, 2013, and 2010. The coefficients of the 2007 and 2010 breaks are negative, and are consistent with the graphical observation of the HPI decline in 2007–2012. The positive coefficient of the 2013 break suggests that the national HPI returned to the positive growth zone in 2013. Further results identify 2009 (negative coefficients) and 2013 (positive coefficients) as structural breaks for both the 20- and 10-City HPIs. Basically, national measures of house prices show the recovery phase beginning in 2013 as all three HPI series have positive break coefficients in 2013.

We find evidence of breaks in all 20 MSA’s HPIs, which confirms the graphical depictions of the boom and bust in home prices over 2002–2012. Most MSA’s HPIs apparently entered a recovery phase in 2013 as most HPIs show positive break coefficients in 2013. There are some exceptions, as Denver, Las Vegas, New York, Miami, and San Francisco began to recover earlier than 2013, while Boston and Dallas started their rebound later.

In sum, our state space method found structural breaks in all HPIs series, which is a confirmation that HPI behavior varies across different markets in our sample period.

4 Is there a relationship between different regional/national housing markets? The spillover effect

The state space estimates formally demonstrate that different behavior exists for different MSA HPIs, with certain MSAs, such as New York and Miami, having earlier turning points. If changes in one MSA’s HPI, New York’s HPI for example, are helpful to predict changes in other MSA HPIs, the Atlanta HPI for instance, then the New York HPI is leading the Atlanta HPI, all else constant. Furthermore, if changes in the New York HPI are useful to predict national HPI, then that would indicate that New York’s HPI leads the national HPI.

There are some major benefits arising from being able to identify lead/lag relationship between HPIs. By definition, leading MSAs will see major price swings ahead of other markets, providing a heads up on future price movements elsewhere, including the nation as a whole. Getting a heads up on swings in home prices may help design and adopt policies intended to arrest excessive changes or ameliorate their effects. These policies may be national or area-specific.

Which MSA’s HPIs are leaders and which are lagers can be tested using the Granger causality test (Granger 1969).

4.1 The Granger causality test and the state of the housing recovery

Granger causality is based on prediction. If a variable X “Granger-causes” a variable Y then past values of X should contain information that helps predict Y above and beyond the information contained in the past values of Y alone.

The Granger causality test further indicates the direction of causality. If X “Granger-causes” Y but Y does not “Granger-cause” X then one concludes there is “one-way” causality. On the other hand, if X “Granger-causes” Y and Y also “Granger-causes” X then there is evidence of “two-way” causality. For instance, in the present case, we test whether the New York HPI Granger-causes the Atlanta HPI. That is, whether New York’s HPI helps to increase predictability of Atlanta’s HPI. If we find one-way causality from New York HPI to Atlanta HPI then that would indicate that the New York HPI is leading the Atlanta HPI. If we find no causality, then that would be a rejection of a spillover effect, and implies housing activities in one area may not spill over to the other area.

The results based on the Granger causality tests are reported in Table 2. The columns indicate the dependent variables (the national HPI is the first dependent variable, followed by the 20-City HPI). There are 23 different HPIs (three national/aggregate and 20 MSAs measures of house prices) and therefore 23 dependent (potential lagging) variables for our models. The rows indicate the independent (or potential leading) variables. For example, the first dependent variable is the national HPI (first variable of the top row) and the first variable in the left column is also national HPI. Obviously, we cannot rest whether a variable Granger-causes itself, so the corresponding cells of the matrix are empty. The next row of the “National” column is marked Yes, indicating that the national HPI Granger-causes the 20-City HPI (20-City is the dependent variable). A cell value of No indicates that the corresponding row variable does not Granger-cause (lead) the corresponding column variable. For instance, Atlanta’s HPI does not Granger-cause the national index.

The results suggest that national measures of the house prices (the national, 20- and 10-City HPIs) Granger-cause all 20 MSA’s HPIs. That national trends are a leading factor for every MSA’s HPI is expected, as monetary policy and some global factors will affect home prices all across the nation (Vitner and Iqbal 2013).

The Granger causality results suggest that there are some leading MSAs (all the highlighted ones) in addition to the national HPIs. That is, the Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, and San Francisco HPIs lead the national HPIs and most of the other MSAs. Put differently, changes in these MSA HPIs matter for both the national and other MSA housing markets. Basically, our results validate the potential for spillover effects, suggesting that a regional housing boom has the potential to become a national housing bubble.

5 Concluding remarks: yes, some regional housing markets do matter

Our study analyzes house prices across different markets looking to determine whether there is a common theme to housing markets experiencing a stronger recovery and those experiencing a weaker recovery.

We found that 12 out of 20 MSA HPIs show consistent behavior (either stay above or below the national HPI line in the sample period) while the other eight show inconsistent behavior. We also found statistically significant structural breaks in all HPI series.

The Granger causality results suggest leading behavior for the Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, and San Francisco MSAs, implying that changes in these MSA HPIs precede comparable changes in the national HPI and HPIs in other MSAs.

Our view is that evidence of interconnections between regional housing markets may have policy implications. Decision makers might monitor activities in the leading markets to gauge and predict the near-term path of the national housing market. In addition, a boom or bust in the leading MSAs housing markets may have the potential to spread to other metro areas.

Notes

The FOMC transcripts can be found at https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomc_historical.htm.

The national and MSA HPIs increased during the 2002–2006 period, and most of these indices peaked in 2006. Similarly, the national and most MSA HPI bottomed in 2012. We use the 2002–2006 period to show the boom, and 2007–2012 to estimate the bust. Specific month of the boom/bust may vary for different MSAs but, we believe, our conclusion would remain the same if we varied the specific peak/tough dates. Using a common boom/bust period helps us compare increases/drops between the national HPI and MSAs.

During the 2009–2011 period, the Miami HPI line stay very close to the national HPI—both HPIs show similar growth path.

The statistical techniques here are covered in more detail in Silvia et al. (2014).

References

Granger, C.W.J. 1969. Investigating Causal Relationships by Econometric Models and Cross-Spectral Methods. Econometrica 37 (3): 424–438.

Silvia, J.E., A. Iqbal, S. Bullard, S. Watt, and K. Swankoski. 2014. Economic and Business Forecasting: Analyzing and Interpreting Econometric Results. New York: Wiley.

Vitner, M., and A. Iqbal. 2013. Did Monetary Policy Fuel the Housing Bubble? The Journal of Private Enterprise 29 (1): 1–24.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper won NABE’s Contributed Paper Award for 2017 and was presented at the NABE Annual Meeting on September 24, 2017.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iqbal, A., Vitner, M. Quantifying the housing recovery: which MSAs are experiencing bubbles?. Bus Econ 52, 250–259 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s11369-017-0052-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s11369-017-0052-2