Abstract

Interest groups work to influence politics. Come election time, groups have an interest in affecting the composition of parliament and government. On their side, parties value the resources groups can contribute to election campaigns. Active electioneering by groups entails risks, however, as some voters and group members may be offended by close interaction between political parties and interest groups. Based on a cost-benefit framework, this article develops a set of expectations concerning the electoral engagement of interest groups. These are investigated drawing on a survey of all national Danish interest groups conducted after the 2011 national election. Most groups see the election as important, but the level of active electioneering is low. The analysis of variation in election involvement contrasts partisan and non-partisan engagement in the election and finds variation in the level and nature of engagement between different types of groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Elections are decisive events in democracies. Political parties and their candidates for office focus much attention on undertaking election campaigns and convincing voters to support them at the polls (Bowler and Farrell, 1992b; Norris, 2000). However, elections are not only a venue for political parties; other political actors are also significantly affected by election outcomes as they set the framework for policymaking in the coming period. Notably, elections are important for interest groups as some parties and candidates are typically more supportive of group causes than others. Interest groups may take a keen interest in elections, and some authors even suggest a growing engagement in elections by organized interests (Schmitt-Beck and Farrell, 2008, p. 13). Understanding the extent to which interest groups rally around political parties at election time is crucial both from an interest group and a party perspective as the level and nature of group engagement may affect both the election outcome and the subsequent relationship between MPs and organized interests.

Rozell and Wilcox (1999, p. 3) report group participation in American elections to be as old as the nation itself, referring to donations of liquor made by local merchants to bribe voters in George Washington’s run for election in 1757. In the US context, there are now high levels of group activity in all types of elections – with tactics ranging from the establishment of political action committees to election-related ads and volunteer work for candidate campaigns (see, for example, Berry, 1984; Austen-Smith, 1987; Hrebenar et al, 1999; Rozell and Wilcox, 1999; Herrnson et al, 2000; Magleby and Tanner, 2004). The massive body of scholarly literature on group involvement in US campaigns is not mirrored in Europe, where few studies have addressed the subject (Allern and Saglie, 2008; Binderkrantz, 2008; Russell et al, 2008; Murphy, 2012). This article therefore provides the first large-scale empirical study of interest group involvement in an European election.

The basic assumption guiding the article is that group engagement in elections can be seen as the result of a deliberate weighting of benefits and costs. In party-centered systems, groups base their electoral involvement on a calculation of the benefits and costs of supporting the campaigns of parties. While much may be won in election campaigns, active electoral involvement is not without hazards. Being closely involved in the campaigns of some parties may harm post-election relations with other parties, and group members may be alienated if their group supports parties that the individual members themselves may not be inclined to vote for. While the analysis focuses on the group side – whether groups are engaged in elections or not – the costs and benefits for the parties may also play a role because they indirectly affect the group calculus. On the one hand, groups may provide parties with valuable resources, but parties may on the other hand not always win from group support as some groups may be unpopular in the population at large or among segments of voters (Allern and Saglie, 2008, pp. 68–69; Binderkrantz, 2008, p. 127). This may serve as a further disincentive for groups when weighting the costs and benefits involved in electoral engagement – to the extent that group support may in fact not help their favored party in the election this may keep groups from becoming engaged.

Based on the cost-benefit perspective, interest groups are expected to be highly interested in the election, but at the same time most groups refrain from active engagement because of the potential costs involved. In particular, a low level of direct partisan engagement – for example in the shape of financial support to parties – is expected, whereas more groups may engage in non-partisan activities such as seeking media attention in relation to the election where the focus is mainly on the issues the group wants advanced. In explaining variation in electoral engagement the type of interest group is expected to be crucial. Those groups – for example blue collar trade unions – who find themselves closely aligned with the party-political constellation are expected to be more engaged than other groups. This pattern is likely to be particularly evident in regard to partisan electioneering, whereas a somewhat broader set of groups may be engaged in non-partisan activities.

The expectations are investigated in a study of the electoral engagement of Danish interest groups in the national election held in the autumn of 2011. The analyses draw on a survey among all national Danish interest groups conducted after the election. While many studies only focus on the set of electorally active groups (Hrebenar et al, 1999; Rozell and Wilcox, 1999; Russell et al, 2008), the general group population is taken here as the point of departure. This allows us to identify uninterested and inactive groups along with highly engaged groups and thus also to analyse the factors affecting group engagement in elections.

Denmark is an example of a Western European multiparty parliamentary democracy and is a relevant case for a study of group electoral engagement outside of the US context. Further, the 2011 election constitutes an interesting case because the election juxtaposed two clear governing alternatives combined with high uncertainty about the outcome. The stakes were therefore high for groups interested in the election outcome. While the findings in the study are of relevance to other similar countries and elections, the specific institutional set-up and characteristics of the party system are likely to affect the engagement of groups in elections. The results are most immediately generalizable to other party-centered political systems characterized by the same overall level of political alignment between the interest group system and the party system. The issue of generalizability will be further discussed in the conclusion.

The next section presents the theoretical argument in greater detail and develops a set of expectations. After discussion of the research design, the electoral engagement of Danish interest groups is analysed.

A Cost-Benefits Perspective on Election Involvement

Accounts of the interaction between interest groups and public officials have increasingly focused on the costs and benefits associated with different political activities (see for example Hansen, 1991; Bouwen, 2004; Beyers and Kerremans, 2007; Braun, 2012). Here, a cost-benefit perspective is applied to the engagement of interest groups in elections. While the focus in the analysis is on the interest group side, the costs and benefits for political parties are also discussed because these may in turn affect the cost-benefit calculus of groups. If open support for a party may actually harm the party’s electoral chances, this will likely induce groups not to declare their support. The basic assumption guiding the discussion is that group engagement in elections can be seen as the result of a deliberate weighting of benefits and costs. In a parliamentary system as found in Denmark, the central actors are interest groups and political parties. Parties and interest groups see each other as a means to an end, and each actor seeks to use the other to fulfill their own goals (Heaney, 2010, p. 574). Depending on the balance between the potential benefits and costs, groups will choose a pattern of electoral engagement.

On the benefits side, a first observation is that political actors have much at stake in election campaigns. Parties want to win elections and are keen to muster the support necessary to do so. Interest groups care about who gets elected and are eager to secure good relations to elected officials after the election. For parties, the benefits calculus behind engaging with interest groups in elections boils down to a need to attract support and resources for election campaigns. Interest groups may, for example, provide parties with financial resources, policy expertise and general organizational support (Allern, 2010, p. 5). While the support of any specific group may not be crucial for the election outcome, parties are generally likely to appreciate group support.

For groups there are two potential benefits from engaging in elections: First, groups are interested in getting their political allies elected. Major policy change often depends on a significant change in the makeup of parliament, and many groups therefore have an interest in affecting the election outcome (Berry, 1984, p. 58). If an elected party representative is pre-disposed to support a particular group’s point of view, the group can look forward to more favorable policies without even lobbying for them. By helping to elect candidates who share their views, interest groups can thus change the government personnel and increase the likelihood that the policies they support will be implemented.

Second, groups may help candidates in order to secure political access after the election. American studies describe a phenomenon whereby groups help candidates who are very likely to be elected. Here, the objective is not to change the election outcome but to buy access – and hopefully favorable policies – once the representative is installed in office (Austen-Smith, 1987, p. 123; Rozell and Wilcox, 1999, p. 2). In Berry’s (1984) words, groups expect the cooperation with parties and candidates to extend past Election Day (pp. 58–59). This may also provide groups with an incentive to be engaged even if their contribution may not be likely to affect the election result. Overall, based on the discussion of the benefits associated with participation in elections, it can be expected that most interest groups are interested in the outcome of elections.

Whether this interest is transformed into electoral engagement depends not only on the possible benefits but also on the costs associated with being involved. For parties, the association with particular interest groups may affect voters in detrimental ways. Miller and Wlezien (1993) argue that citizens perceive social groups to be connected with varying degrees of intensity to different political parties. In turn, individuals’ evaluations of those groups influence their orientations toward political parties and candidates. While association with popular groups may lend parties credibility and legitimacy, it might also become a problem for parties if voters associate the party with groups that are unpopular in the population at large or among segments of voters that are important to the party’s electoral success.

Group support to parties can accordingly be seen as a two-edged sword where parties and candidates may benefit from group support but also risk being harmed by group baggage. According to Kirchheimer (1966, pp. 190–191), parties must increasingly de-emphasize their attachments to specific groups in favor of recruiting voters at large and must therefore modulate their interest-group relations to facilitate this aim. As the erosion of traditional bases of party support in socio-economic groups has continued in the decades after Kirchheimer’s observation (Stubager, 2008), this has become increasingly relevant. While political parties and – some – interest groups could historically be seen as manifestations of the same social cleavages, socio-economic changes throughout the twentieth century have had a profound effect on party – group linkages (Howell, 2001, p. 32; Schmitt-Beck and Tenscher, 2008, pp. 151–152; Stubager, 2008; Allern and Bale, 2012, p. 10).

Ties between groups and parties have generally declined across Europe, as both parties and groups have an interest in greater independence (Howell, 2001, p. 7; Thomas, 2001; Allern and Saglie, 2008, pp. 67–68; Allern, 2010, p. 5). For example, even though organized labor and social democratic parties continue to share interests, overly close ties to unions have become dysfunctional to the electoral success of the Social Democrats. Oftentimes, parties thus prefer groups to keep their support below the radar or even to stay out of election campaigns entirely (Magleby and Holt, 1999, p. 27; Russell et al, 2008). In an illustrative example, Russell et al (2008) describe how a campaign launched by hunting interests seeks: ‘a fine distinction between stimulating those voters receptive to the message without alerting those who disagreed with the message’ (p. 111).

To the extent that interest groups are engaged in elections to help their favorite parties they are likely to factor the benefits and costs to the parties into their calculations. In addition, groups face similar dilemmas themselves. By supporting a specific party or a number of candidates, groups risk losing credibility with other – and perhaps even future governing – parties and politicians (Allern and Saglie, 2008, p. 70). Aside from the incentives to support allies, groups therefore also have an interest in maintaining friendly relations with all candidates and parties (Key, 1947, p. 212; Berry, 1984, p. 58; Allern, 2010, p. 87). Open support to political parties also risks repelling members from affiliation with the group. This dilemma is likely to have become more pressing over time as an effect of the decline of traditional political cleavages based on socio-economic groups (Allern, 2010, p. 85). For many groups, this has meant greater diversity in the range of political parties that group members support. Even unions – who used to be part of the most institutionalized party – group relationship – risk alienating parts of their members if they are seen as tightly linked to social democratic parties (Howell, 2001, pp. 7–10; 193; Allern, 2010, p. 4). Interest groups must therefore acknowledge their members’ distribution of votes across the entire political spectrum and that the groups’ electoral engagement risks alienating members or potential members.

Expectations about level and type of engagement

There are several implications of the above discussion. First, for most groups, we expect the costs associated with electoral engagement to outweigh the benefits. Group engagement in elections may alienate group members, harm relations to other parties, and the open support of groups may not even be helpful to parties. Therefore we expect that the general interest in the election is for most groups not transformed into actual engagement in election related activities.

Second, to the extent that groups do choose to be electorally involved, their engagement may differ across different types of activities. Groups can engage in many different tactics during an election, some involving more costs than others. Allern and Saglie (2008, p. 75) point out two dimensions in the electoral involvement of individual interest groups: First, refers to the number of election-related activities groups are engaged in and how directly they seek to influence the electoral result; second the autonomy of the involvement in terms of the degree of independence from party electioneering. The hazards of electoral engagement are primarily associated with partisan election engagement. For both parties and groups it may therefore be optimal to keep group support under the radar (Russell et al, 2008, p.111). Tactics such as campaign contributions or endorsing specific candidates and parties, send a clear signal about party support. More subtle ways of helping parties such as assisting in the production of election materials or providing parties with volunteers from interest group core circles, reduce the potential risks.

Furthermore, direct support for parties is not the only way for groups to engage in elections. A particularly important channel is to engage in the public debate. Generally, the news media have come to play a very prominent role in electoral politics where parties focus on maintaining a favorable image in the media (Bowler and Farrell, 1992a; Norris, 2000). Interest groups – which are generally very active towards the media (Binderkrantz, 2005, 2012) – may also turn to the media to exploit the opportunities associated with the election. In fact, many American groups turned to this option in reaction to stricter campaign contribution regulations (Herrnson et al, 2000).Footnote 1 Attempts at influencing the media agenda in election campaigns do not carry the same costs as direct support for political parties. Rather than endorsing specific candidates or parties, groups can seek to influence the general agenda and emphasize group issues and angles. Without openly supporting parties, this may benefit parties with similar policy agendas. Group members can be expected to be favorably inclined toward attempts to place issues on the agenda as long as doing so does not directly harm the parties they support. The expectation is therefore that the level of non-partisan engagement is higher than the level of partisan engagement.

Variation across interest group types

While the discussion has until now focused upon the overall level and type of electoral engagement it is also crucial to discuss which types of groups may primarily decide to be engaged. Interest groups come in many shapes, and the cost/benefit calculus may depend crucially on the type of causes that groups seek to advance and on the composition of the membership. While it is not possible to map group membership – for example in terms of the party political affiliation of members – in an analysis of the full group population some general expectations based on the type of group may be advanced.

Notably, interest groups are differently positioned vis-à-vis the party-political constellation. Even though traditional linkages between groups and parties have declined over time, there are differences in how closely groups find their interests associated with particular parties or political sides. Some groups may see only one or two parties as the possible champions of their interests, while others may find allies in all political camps. For example, if there is a clear polarization among parties on the immigration issue, groups working for or against immigration will be particularly affected by the election outcome. The crucial factor is the party-political constellation and the positions of parties and groups regarding different issues. This logic affects both the benefits and costs related to electoral engagement. For some groups, achieving significant progress in politics depends entirely on the composition of parliament. Members of such groups are also likely to find electoral engagement legitimate as it is clear to them that some parties unilaterally represent the group interests.

The degree of alignment with the party-political constellation may vary systematically across different types of interest groups. Contextual knowledge is necessary in order to specify how this operates in a particular setting. Based on studies of Danish politics, two dimensions are relevant: First, the traditional economic left-right cleavage remains an important feature of Danish politics. Therefore, we expect types of groups associated with this dimension to be more active than other groups. This is the case for trade unions and business groups in general, but the effect is expected to be particularly marked for unions associated with the Danish LO, which typically represents blue-collar workers. For business groups it is less clear to single out specific types of groups with a particularly clear alignment with the left-right dimension.

Second, a new political dimension has gained in importance in Denmark and elsewhere (Stubager, 2008). The groups most clearly associated with this dimension are environmental groups and humanitarian groups working with refugees and immigration – that is citizen groups related to new politics. These groups are likely to have a particular incentive to be active because the two government alternatives had highly differing stances in regard to their issues. Consequently we propose that blue-collar trade unions and citizen groups associated with new politics are more active than other groups. While this may be relevant for all types of electoral engagement, the difference between group types is expected to be particularly large in terms of partisan engagement.

Research Design

The present analysis concerns the national Danish election held on 15 September 2011. The election was officially called on 27 August, when Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen took the floor in parliament and announced a national election to be held 3 weeks later. The existing government coalition consisted of Rasmussen’s Liberal Party and the Conservatives with support from the right-wing Danish People’s Party. While these parties aspired to yet another term, a Social Democrat-led alliance challenged the government. The challengers had long led in the polls, but excitement grew up to Election Day as the two governing alternatives moved closer in the polls. At the end of the day, the challengers won the election and a new government was formed with Social Democratic leader Helle Thorning-Schmidt as Prime Minister. The Socialist People’s Party and Social Liberals also joined the new government. This election brought an end to ten years of bourgeois reign and a major shift in political power (Kosiara-Pedersen, 2012).

The focus here is on the electoral engagement of interest groups. This issue is addressed through a survey of all national interest groups. Compared with previous research, which focuses narrowly on groups engaged in elections (Allern and Saglie, 2008; Binderkrantz, 2008; Russell et al, 2008), this approach provides a broader picture of the extent of group election involvement and the factors affecting this involvement. Interest groups are defined as associations of members or supporters working to obtain political influence. Group members may be individuals, firms, government institutions or other interest groups. Establishing a comprehensive list of national interest groups is no simple task (Halpin and Jordan, 2012). In the absence of any official registers of groups or lobbyists, several sources have been consulted in the compilation of the list of interest groups. First is a list of national Danish interest groups used in previous surveys and continually updated since it was first established in 1975 (see Christiansen, 2012). All groups on the list were checked to update address information and ensure that the group still existed. Second, all groups represented in public committees, participating in government consultations, approaching parliamentary committees or appearing in two major national newspapers in the period from 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2010 were added to the list. Third, searches of several lists of groups appearing on the Internet were conducted, and new groups found here were added.

The group survey was sent out in the beginning of October 2011, about 2 weeks after the election, and the last questionnaire was returned in February 2012. Groups were asked to let a person with thorough knowledge of the group’s political work fill out the questionnaire. To secure a high response rate, groups were initially contacted by e-mail. Non-responding groups were subsequently contacted by regular mail. During the survey, many groups were deleted from the initial list. Some turned out to be duplicates, others reported that the group no longer existed and the existence of many others remained unclear. After removing these groups from the list, 2541 groups remained, 1645 of which responded, corresponding to a 65 per cent response rate. The non-responding groups are similar to the responding groups with respect to distribution across different types of groups, but their presence in different political arenas is slightly lower. This possibly also means that the level of electoral engagement found among respondents is slightly higher than among non-respondents.

A crucial characteristic of interest groups is that they seek political influence – although this does not imply that influencing politics is necessarily their main or only purpose (for a contrary argument about how to define groups, see Jordan et al, 2004, p. 207). It can, however, be difficult to determine which groups are politically active. While establishing that major unions and business groups do indeed seek influence on behalf of their members is easy, determining whether an association of patients merely serves as a network for members or if it also tries to affect political decisions on health issues is less straightforward. The first set of questions in the questionnaire was therefore designed to distinguish between generally politically active and non-active groups. Specifically, groups were asked whether they worked to affect public opinion, the media agenda, the political agenda, bills and parliamentary decisions, administrative regulations or decisions made by the public bureaucracy. Groups replying ‘not at all’ to all these possible types of influence were excluded from the survey as were groups that contacted the researchers by phone or e-mail to inform us that they were not politically active. Once the non-political groups had been removed, 1109 groups remained for further analysis. All these groups could potentially be engaged in the election as they seek political influence to at least some extent. It is very unlikely that the groups excluded as non-political were engaged in the election in any way.

The dependent variable in the analyses is group involvement in the election. There are two aspects to this: the type of engagement and the overall level of engagement. Crucially, we distinguish between partisan and non-partisan engagement. For each type of engagement, measures are developed for whether the group engaged at all and for the level of engagement among those who did get involved. To address this, groups were asked about a range of different types of engagement in the election (no period was specified). Although groups may engage in a large number of different activities, we had to focus on selected activities because of the length of the questionnaire. These were chosen to include openly partisan and non-partisan activities alike. For example, ‘financial contributions to one or more parties’ were included as a partisan activity, while ‘sought media attention in relation to the election’ is an activity that can be used in a non-partisan manner. The exact wording of the questions can be seen in Table 2.

The empirical relevance of the distinction between partisan and non-partisan engagement was confirmed in a factor analysis.Footnote 2 The item ‘advertisements for example in newspaper’ was subsequently excluded from the index construction because it loaded relatively high on both factors and the Cronbach’s Alpha of the non-partisan index was higher without this item. Based on the remaining items, two indices of electoral engagement were formed. Each index was constructed by simply taking the mean score on the items and recoding it on a 0–1 scale. The indices had a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.71 (partisan) and 0.76 (non-partisan) respectively.

While different types of engagement are included, groups may conceivably be involved in activities not covered here. For example, we have not included the use of new social media or asked whether groups have used internal communication media to engage their members in the election. Even though some groups may thus engage in activities not included here, it is difficult to imagine large discrepancies between those types of activities and for example political support to parties or seeking media attention in regard to the election. It should be noted, however, that it is not possible to link the activities to specific parties. While this would have been interesting, it is considered sensitive information by many groups and has therefore deliberately not been included in the survey in order to ensure high response rates.

The crucial independent variables relate to group type. Blue-collar unions and citizen groups related to a new politics dimension are expected to have a particularly high incentive to be active. The categorization of groups is suited to testing the expectations and builds on conventional categories for distinguishing between interest groups (Schlozman et al, 2012). Among economic groups, we include business groups and trade unions (distinguishing between blue-collar and others). Our category of citizen groups includes both those seeking benefits for limited constituencies, such as patients or student groups, and those seeking public goods (Dunleavy, 1991; Schlozman et al, 2012, p. 31). To match the theoretical expectations, citizen groups are further divided into those related to new politics and other citizen groups. Finally, a category of ‘other groups’ is included in the analyses. Groups were coded into different types of groups based on their names, type of members represented and, if in doubt, on descriptions found on group websites. The coding of group types was done by the author with a reliability coding of 100 groups by an expert coder, resulting in a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.91.

Two control variables are included in the multivariate analyses. First, groups differ on the intensity of their political involvement and the range of policy areas they seek to influence (Halpin and Binderkrantz, 2011). Some groups engage in a very narrow set of issues and only occasionally seek political influence, while others regularly participate in political discussions across many policy areas. These latter groups are expected to have the most to gain from electoral engagement and therefore to be the most active. To construct a measure of the engagement of groups, they were asked about their level of engagement in 19 different policy areas and a scale of engagement was constructed. Groups received 3 points for each area in which they were ‘very’ engaged, 2 points for areas with ‘some’ engagement and 1 point for areas with ‘little’ engagement. The measure was re-coded to range from 0–1, 1 indicating the broadest possible engagement.

Second, group resources have often been found to affect group activity (Binderkrantz, 2005; Eising, 2007). In a cost-benefits perspective resources are relevant because they affect the opportunity costs related to electoral engagement. Groups facing severe resource constraints can be expected to be less actively engaged in election-related activities than resourceful groups. A measure of group resources was constructed based on the number of group employees involved in political work, including contact to civil servants, politicians or journalists as well as working with analyses or monitoring the political process. The measure was logarithmically transformed to obtain linearity and recoded to range from 0–1 (the highest number of political employees reported by a group was 280).

Interest Groups in a Danish National Election

This section analyzes the electoral engagement of interest groups. First, it addresses the descriptive issue of the relation between election interest and engagement. Second, the question of variation across group types in electoral engagement of a partisan and non-partisan nature is addressed in a set of multivariate analyses.

The electoral engagement of groups

As politically interested actors, interest groups are expected to monitor the election closely. The election sets the framework for policymaking in the coming period, and the election result may be decisive for interest groups’ chances of achieving their respective political goals. Table 1 displays group answers to a set of questions aimed at tapping the level of group interest in the election.

Overall, most groups are interested in the election. Only 11.2 per cent report that they had no interest at all in the election, while 20 per cent state that the election outcome was not important to them. The remaining groups are interested in the election outcome, but the intensity of their interest varies with about 30 per cent indicating that the election outcome was important ‘to a large degree’. The results also clearly indicate that many groups are perfectly aware of their political allies and enemies. More than half of the groups report that they agree more with some parties than others (at least ‘to some degree’). This analysis demonstrates the validity of the fundamental argument that interest groups potentially have something to gain from electoral engagement. While the main contenders at elections are political parties and their candidates, interests groups certainly also see elections as decisive events.

Next, we ask whether groups watch electoral battles from the sidelines or turn their electoral interest into active engagement. While benefits accrue to electoral engagement, the costs are expected to outweigh the benefits for most groups. Groups may harm relations to some parties by supporting others, they risk alienating members, and open support from interest groups may not even enhance a party’s chances of attracting votes. We therefore expect that most groups will refrain from engaging in the election and that among those who do get involved more groups will choose activities of a non-partisan than a partisan nature. To test these expectations, Table 2 reports the extent to which groups are involved in different types of electoral engagement.

It becomes evident that most groups do not turn their interest in the election outcome into active engagement. When asked about a range of different election-related group activities, 73–96 per cent of the groups report no engagement. In other words, Danish political parties cannot expect interest groups to rally around them come election time.

Some of the most public activities are least commonly used, less than 5 per cent of groups donate money to political parties or run ads. The level of engagement is higher but not impressive when it comes to other types of activity. About 17 per cent discussed the election campaign with one or more parties, and a similar number reports having developed material for use by all parties. These numbers are evidence of at least some election-related contact between interest groups and political parties – although even here the lion’s share of groups remains clear of contact. Among the most common types of engagement is seeking media attention. Roughly 27 per cent of the groups state that they have sought media attention in relation to the election (at least ‘a little’). While this activity does not necessarily entail partisan involvement but also includes attempts to place an issue on the election agenda, most groups still report not engaging in it.

The expected pattern of a difference between engagement in partisan and non-partisan activities is not readily evident. For example, about 19 per cent report that they supported one of the political sides in the election, making this the second most common type of engagement. Rather, the differences seem to relate to whether the questions concern rather diffuse types of engagement such as supporting a political side or seeking media attention or more specific activities such as placing ads in newspapers.

Explaining level of activity

Most groups refrain from getting involved, but some groups do engage in election-related activity. For example, about 170 groups had sought media attention, and about 75 groups discussed the election campaign with one or more parties at least to some degree. These groups may have influenced party platforms, the election agenda or even the election outcome. Identifying the factors distinguishing the involved from the non-involved is certainly not less interesting because the election is an arena for a minority of all groups. Is electioneering – as speculated above – mainly engaged in by those types of interest groups that are most closely aligned with party-political constellations, and are some types of groups more engaged in partisan activities while others choose non-partisan types of engagement?

Table 3 presents four different regression analyses. Because of the many groups reporting no engagement at all, a logistic regression has been conducted with a dummy variable for having a score different from zero as dependent variable. For groups with at least some level of engagement an OLS regression has also been performed. This enables an analysis of the factors affecting whether groups get involved at all and the factors shaping the level of engagement among those that do get involved.

The analysis largely lends support to the expectations of differences among group types. It is particularly notable that blue-collar unions and citizen groups related to new politics are more likely to be involved in both partisan and non-partisan engagement than business groups (the reference category). In terms of the level of engagement, blue-collar unions are more likely to exhibit high levels of partisan engagement, whereas citizen groups related to new politics are more heavily involved in non-partisan activities. In regard to non-partisan engagement citizen groups not related to new politics are also more likely to be active than business groups. The two control variables – number of political employees and broad political engagement – are both crucial for non-partisan engagement, while only the nature of a groups’ engagement affects partisan electioneering.

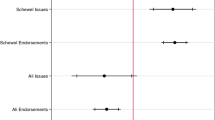

To provide a clearer impression of differences across group types, Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the electoral engagement of groups based on the regressions above. Figure 1 displays the predicted probability of being engaged in any kind of election-related activity of partisan versus non-partisan nature. Figure 2 displays the predicted level of engagement for groups that report to be involved at least at a minimal level.

Group type and predicted probability of partisan and non-partisan engagement.

Note: The figure displays the predicted probability of engagement for each group type based on the logistic regressions reported in Table 3. N for the distribution of groups in the survey: blue-collar unions=37, other unions=117, business groups=283, citizen groups new politics=76, other citizen groups=257 and other groups=339.

Group type and predicted level of partisan and non-partisan engagement.

Note: The figure displays the predicted level of engagement for each group type based on the OLS regressions reported in Table 3. N for partisan engagement: blue-collar unions=28, other unions=18, business groups=63, citizen groups new politics=29, other citizen groups=45, other groups=42. N for non-partisan engagement: blue-collar unions=27, other unions=50, business groups=85, citizen groups new politics=40, other citizen groups=112, other groups=66.

A first observation is that differences across group types are larger for partisan than non-partisan engagement. For example, while a blue-collar union has a two-thirds probability of being involved in partisan electioneering, other unions only have a probability of .1. In contrast, the likelihood of non-partisan engagement ranges between 0.25 and 0.5 (Figure 1). The same pattern emerges for predicted level of engagement among the active groups (Figure 2). Here, the average scores on the index for partisan engagement vary between 0.2 and 0.5, while the non-partisan scores are between 0.3 and 0.4. While the analyses above did not support the expectation of a lower level of engagement in partisan than non-partisan activities, differences between group types support the expectation that partisan engagement is mainly found among certain types of groups.

The specific patterns in regard to partisan engagement also largely supports the argument that groups associated with the party-political constellation will be more prone to develop this type of engagement. Blue-collar unions stand out in particular as they are much more likely than any other type of groups to be involved in partisan electioneering, but citizen groups associated with new politics are also more than twice as likely than other citizen groups to be among those involved in partisan activities (Figure 1). If they do become involved (Figure 2), only blue-collar unions stand out with a higher level of engagement than other group types.

Turning to non-partisan engagement, blue-collar unions and citizen groups (both those related to new politics as expected and other citizen groups) are the most likely to become engaged, and business groups less likely (Figure 1). The substantial differences in level of engagement are not very high with the two types of citizen groups being somewhat more involved than other groups (Figure 2). The level of activity in groups that do become involved seems to be more affected by other factors such as resources and the nature of their policy engagement.

Overall, the analysis lends support to the cost – benefit perspective. While an election constitutes a set-up with high stakes, the result of such calculations is, for most groups, to stay out of the way. There is an obvious paradox in this finding. On the one hand, groups report a high level of interest in the election outcome; on the other, almost three out of four groups do not engage in any election-related activities at all. Even though there is clearly something to be gained by seeking influence on the election outcome, most groups refrain from being active. The explanation is likely to be found in the costs associated with electioneering. First, active support from interest groups may not always benefit political parties and candidates (Miller and Wlezien, 1993; Russell et al, 2008). Second, groups face potential hazards if engaging in an election: they risk harming their relations to other parties, and their members may dislike partisan involvement (Allern and Saglie, 2008; Allern, 2010).

The alignment of groups to the party-political constellation also matters. Among the most active groups – particular when it comes to partisan engagement – are blue-collar labor unions. They are likely to calculate with more gains and fewer costs. First, their interests are clearly associated with the traditional left – right dimension in Danish politics, and it is therefore quite clear which parties will best advance their interests. Second, they have a lengthy tradition of supporting the Social Democrats in particular, and while many of their members vote for other parties, they expect their trade union to support the left-wing parties. A parallel reasoning can account for the relatively high involvement of citizen groups associated with the new politics dimension. These groups also represent causes that are clearly aligned with the party-political constellation and face fewer costs than other groups when declaring this publicly. Members of groups established in reaction to the incumbent government are not likely to have any problem with their group actively supporting the opposition. Moreover, for such a group substantial policy change in favor of the group position will require a change in government (Berry, 1984, p. 58).

More surprisingly, trade unions representing non-blue collar groups and business groups are not very involved in the election. In fact, ‘other unions’ are least likely to exhibit partisan engagement. Like blue-collar trade unions, their interests have traditionally been associated with the traditional left-wing dimension. Part of the explanation may be a division of labor whereby some of the larger groups are in fact active. Although examination of the names of the most active groups lends some support to this interpretation, more detailed analyses – based on, for example, interviews with selected groups – are required to investigate this and related questions. At a more general level, this finding supports the argument of a general dealignment among groups and parties with interest groups nurturing a wider set of political contacts (Allern, 2010).

Conclusion and Discussion

Elections are not only for political parties. Interest groups also have much at stake in elections, and some groups choose to engage in the election campaign. This article has presented the first large-scale study of the electoral involvement of interest groups in a Western European country. While previous analyses of election engagement have focused on active groups, this study is based on the entire group population. This has enabled a mapping of the puzzling match between a very high level of interest in the election and low level of election-related activity. Although they care about the election outcome, most groups prefer to watch from the sidelines. This is particularly notable because the analysed election juxtaposed two clear governing alternatives in combination with high uncertainty about the election outcome – thus the stakes were high for groups affected by the election.

A cost-benefit approach has been helpful in accounting for the observed pattern in electoral engagement. The most engaged groups were those who had most to win and least to lose because of their alignment with the party-political constellation. This pattern was particularly prominent in regard to partisan engagement, whereas a somewhat wider set of groups involved themselves in a non-partisan manner. However, the analyses do not constitute a definitive test of the theoretical perspective. Future research may help shed more light on the dynamics driving the involvement of interest groups in election campaigns.

First, parties have only been indirectly covered, based on the argument that interest group actions may partly depend on the costs and benefits for parties. A more detailed empirical mapping of the benefits and costs associated with the interaction between groups and parties would require investigating both types of actors.

Second, the article has focused on mapping the full universe of groups. This has come at the cost of using rather general survey questions and only conducting indirect tests of the alleged importance of the costs and benefits involved in electoral engagement. An interesting project for future research is a more direct mapping of the factors that may cause interest groups to stay clear of electoral engagement – for example the partisan composition of group members.

Another important project is to map the interaction between specific groups and parties. This will allow scholars to address the highly important question of the nature of alliances between groups and parties – and in particular whether the cost-benefit-based logic leads to a systematic bias in the level of group support with some parties receiving more support than others. Here, the present results indicate that the most active groups are those who find their interests clearly aligned with one of the political sides. This pattern of group engagement may thus contribute to a certain radicalization of electoral politics.

The choice of a single election in a specific country for analysis also raises the issue of generalizability. To what extent can we expect the results to be repeated in other contexts? First, the Danish 2011 election was a relatively close contest between two governing alternatives, and there is therefore reason to believe that group incentives to engage in the election were high. It is therefore likely that the low level of engagement in this election is generalizable to other Danish elections. When it comes to generalizability across countries, the results are most relevant for party-centered systems. In candidate-centered elections, the support of particular interest groups may have a larger effect on the election result and this may be one explanation for the higher level of election engagement in the United States. Second, the level of electoral engagement may also depend on the consequences for groups if their favored governing alternative does not win the election. Notably, Denmark’s relatively strong parliament and tradition of multiparty governments may offer groups valuable access points regardless of who wins the election.

While some contextual factors may thus lead to differences in electoral engagement, the decline in traditional cleavage politics has been described as a phenomenon that generally affects Western European countries (Kirchheimer, 1966; Allern and Bale, 2012). Interest groups in other Western European countries may therefore find themselves in much the same situation as Danish groups – with high interest in the election outcome but few incentives to become actively involved. While some variation may be found depending on the context, the overall pattern is likely to be generalizable at least to other West European countries.

Conversely, the specific pattern of engagement – the concrete activities engaged in and the type of groups mainly involved – is likely to vary between political systems and elections. One factor is the possible differences between national regulatory environments. In Denmark, for example, election ads are not allowed on television, and donations to political parties over EUR 7000 must be disclosed (Retsinformation.dk, 2013). Such regulation obviously affects the kind of activities groups engage in. The setup of the group system and the party-political constellation also vary from country to country. Nevertheless, the general logic can be expected to be the same: When there are clear links between the interests of particular interest groups and the dimensions in the party systems, these groups can be expected to be engaged. When relations are less clear, groups can be expected to stay low and prioritize the options for attracting members of different political leanings and for collaboration across the political spectrum.

Notes

Following the 2008 Supreme Court decision in Citizens United versus Federal Election Commission, case groups have again turned to direct support to candidates.

Two factors with Eigenvalues above 1 occurred and the loading of the items (oblimin rotated solution) confirmed theoretical expectations.

References

Allern, E.H. (2010) Political Parties and Interest Groups in Norway. Essex: ECPR Press.

Allern, E.H. and Bale, T. (2012) Political parties and interest groups: Disentangling complex relationships. Party Politics 18 (7): 7–25.

Allern, E.H. and Saglie, J. (2008) Between electioneering and ‘politics as usual’: The involvement of interest groups in Norwegian electoral politics. In: D.M. Farrel and R. Schmitt-Beck (eds.) Non-Party Actors in Electoral Politics. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 67–101.

Austen-Smith, D. (1987) Interest groups, campaign contributions, and probabilistic voting. Public Choice 54 (2): 123–139.

Berry, J.M. (1984) The Interest Group Society. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

Beyers, J. and Kerremans, B. (2007) Critical resource dependencies and the Europeanization of domestic interest groups. Journal of European Public Policy 14 (3): 460–481.

Binderkrantz, A. (2005) Interest group strategies: Navigating between privileged access and strategies of pressure. Political Studies 53 (4): 694–715.

Binderkrantz, A. (2008) Competing for attention: Interest groups in the news in a Danish election. In: D.M. Farrel and R. Schmitt-Beck (eds.) Non-Party Actors in Electoral Politics. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 127–149.

Binderkrantz, A.S. (2012) Interest groups in the media. Bias and diversity over time. European Journal of Political Research 51 (1): 117–139.

Bouwen, P. (2004) Exchanging access goods for access: A comparative study of business lobbying in the European Union institutions. European Journal of Political Research 43 (3): 337–369.

Bowler, S. and Farrell, D.M. (eds.) (1992a) Conclusion: The contemporary election campaign. In: Electoral Strategies and Political Marketing. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bowler, S. and Farrell, D.M. (eds.) (1992b) The study of election campaigns. In: Electoral Strategies and Political Marketing. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Braun, C. (2012) The captive or the broker? Explaining public agency-interest group interactions. Governance 25 (2): 291–314.

Christiansen, F. (2012) Organizational de-integration of political parties and interest groups in Denmark. Party Politics 18 (1): 27–43.

Christiansen, P.M. (2012) The usual suspects: Interest group dynamic and representation in Denmark. In: D. Halpin and G. Jordan (eds.) The Scale of Interest Organization in Democratic Politics: Data and Research Methods. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dunleavy, P. (1991) Democracy, Bureaucracy and Public Choice. Economic Explanations in Political Science. New York: Harvester/Wheatsheaf.

Eising, R. (2007) The access of business interests to EU institutions: Towards elite pluralism. Journal of European Public Policy 14 (3): 384–403.

Halpin, D. and Binderkrantz, A.S. (2011) Explaining breadth of policy engagement: Patterns of interest group mobilization in public policy. Journal of European Public Policy 18 (2): 201–219.

Halpin, D. and Jordan, G. (eds.) (2012) Estimating group and associational populations: Endemic problems but encouraging progress. In: The Scale of Interest Organization in Democratic Politics: Data and Research Methods. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hansen, J.M. (1991) Gaining Access: Congress and the Farm Lobby, 1919–1981. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Heaney, M.T. (2010) Linking political parties and interest groups. In: L.S. Maisel and J.M. Berry (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of American Political Parties and Interest Groups. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 568–587.

Hernsson, P., Burns, P. and Francia, P.L. (2000) Labor at work: Union campaign activity and legislative payoffs in the U.S. House of representatives. Social Science Quarterly 81 (2): 507–522.

Howell, C. (2001) The end of the relationship between social democratic parties and trade unions? Studies in Political Economy 65: 7–37.

Hrebenar, R.J., Burbank, M.J. and Benedict, R.C. (1999) Political Parties, Interest Groups, and Political Campaigns. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Jordan, G., Halpin, D. and Maloney, W. (2004) Defining interests: Disambiguation and the need for new distinctions? The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 6 (12): 195–212.

Key, V.O. (1947) Politics, Parties and Pressure Groups. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell.

Kirchheimer, O. (1966) The transformation of the Western European party system. In: J. LaPalombara and M. Weiner (eds.) Political Parties and Political Development. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kosiara-Pedersen, K. (2012) The 2011 Danish parliamentary election: A very new government. West European Politics 35 (2): 415–424.

Magleby, D. and Holt, M. (1999) The long shadow of soft money and issue advocacy ads. Campaigns and Elections 20 (4): 22–27.

Magleby, D.D. and Tanner, J.W. (2004) Interest-group electioneering in the 2002 congressional elections. In: D.D. Magleby and J.Q. Monson (eds.) The Last Hurrah? Soft Money and Issue Advocacy in the 2002 Congressional Elections. Washington DC: Brookings.

Miller, A.H. and Wlezien, C. (1993) The social group dynamics of partisan evaluations. Electoral Studies 12 (1): 5–22.

Murphy, G. (2012) Influencing political decision-making: Interest groups and elections in independent Ireland. Irish Political Studies 25 (4): 563–580.

Norris, P. (2000) A Virtuous Circle: Political Communications in Postindustrial Societies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Retsinformation.dk (2013) Bekendtgørelse af lov om private bidrag til politiske partier og offentliggørelse af politiske partiers regnskaber, https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=2409, accessed 15 August 2013.

Rozell, M.J. and Wilcox, C. (1999) Interest Groups in American Campaigns: The New Face of Electioneering. United States: Congressional Quarterly.

Russel, A., Denver, D., Cutts, D., Fieldhouse, E. and Fisher, J. (2008) Non-party activity in the 2005 UK general election: Promoting or procuring electoral success? In: D.M. Farrell and R. Schmitt-Beck (eds.) Non-Party Actors in Electoral Politics. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 103–125.

Schmitt-Beck, R. and Farrell, D. (2008) Introduction: The age of non-party actors? In: D.M. Farrel and R. Schmitt-Beck (eds.) Non-Party Actors in Electoral Politics. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 13–24.

Schmitt-Beck, R. and Tenscher, J. (2008) Divided we march, divided we fight: Trade unions, social democrats, and voters in the 2005 general election. In: D.M. Farrel and R. Schmitt-Beck (eds.) Non-Party Actors in Electoral Politics. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 151–182.

Schlozman, K.L., Verba, S. and Brady, H.E. (2012) The Unheavily Chorus. Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stubager, R. (2008) Education effects on authoritarian – libertarian values: A question of socialization. The British Journal of Sociology 89 (2): 327–350.

Thomas, C.S. (ed.) (2001) Toward a systematic understanding of party – group relations in liberal democracies. In: Political Parties and Interest Groups. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, pp. 269–291.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

This research was supported by the Danish Council for Independent Research, grant no. 0602-01212B.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skorkjæ Binderkrantz, A. Balancing gains and hazards: Interest groups in electoral politics. Int Groups Adv 4, 120–140 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/iga.2014.20

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/iga.2014.20