Abstract

There is a long tradition in comparative research on industrial relations of analysis concentrating on differences and similarities between countries, that is, focusing on aggregates measured at the national level. But what happens if there are no (more) differences in industrial relations systems between countries? If there are not differences the question arises if comparative research is becoming meaningless? Concentrating predominantly on statistical and methodological aspects, it is argued in this article that over recent decades industrial relations systems have changed in such a way that the national level has become less relevant as a unit of analysis. It is explained that this development in the nature of the field affects the measurement of its indicators which form the backbone of any comparison. On the basis of an empirical comparison of key industrial relations indicators in the European Union member states, it is concluded that comparative research has not reached a dead end, but rather that the field might have to reconsider the relevant unit for analysis. It is shown that the relevant unit for analysis has shifted increasingly from the national towards the sectoral level. One consequence of this shift is that from a methodological perspective comparisons between sectors, rather than between countries, are nowadays often more informative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Comparative research in the field of industrial relations, that is, in social dialogue, has a long tradition. Very influential and important theoretical and empirical research that has been undertaken in the field has for the most part been of a comparative nature (e.g., Crouch, 1993; Hyman, 2001; Traxler et al, 2001; Marginson and Sisson, 2004; Meardi, 2013). From a policy perspective, the most-influential work which has informed (fundamental) public-policy decisions in the past has been predominantly comparative (e.g., Calmfors and Driffill, 1988; Soskice, 1990; Traxler, 1995). The results and conclusions on the basis of this comparative research arguably had an impact in the period of institution building in the early 1990s in former communist countries, and in recent years for the ‘Troika’ reforms in some European Union (EU) member states.Footnote 1

From a methodological perspective, the principle behind comparative research in the field is that differences in industrial relations institutions, actors, and processes, that is, industrial relations systems, are identified and then compared. Implications are then inferred on the basis of that comparison, of course, comparative research rests on the existence of differences between units of analysis. In the tradition of comparative research in the field it rests on differences between industrial relations systems in different countries. It is asked in comparative research whether or not a difference in industrial relations systems makes a difference on something else or not. A ‘classic’ example in comparative research is the question of whether different levels on which collective bargaining takes place in different countries (e.g., on the national, sectoral, or company level) has an impact on socio-economic aggregates. This includes, for example, the impact on the competitiveness of companies, the (un-)employment level, the income (in-)equality or the level of social unrest in countries. In this context, differences between industrial relations systems in different countries are put in relation to other factors in the countries and the question of whether or not there is a theoretical and empirical relationship is analysed. There are, of course, differing (and also competing) theories upon the causal relationships between different variables, as well as debates around the empirical support of different theories.Footnote 2 Independent from the discussion on which theories and empirical studies dominate the (current) debates, the crucial point from a methodological perspective is that if there are no differences in the explanatory variables, any observed differences in the explained variable cannot be explained (and vice versa).

There is no doubt that there are many differences between countries which are expressed by differences in various aggregates. For example, are countries differing in terms of their aggregate labour productivity as well as regarding their strike activity? A comparison between Finland and Spain in the past 15 years shows that labour productivity is higher and strike activity is lower in Finland than compared with Spain. However, in both countries industrial relations are very centralised (e.g., Aumayr-Pintar et al, 2014; European Commission, 2015). So the question arises as to whether or not industrial relations systems matter at all and whether or not country differences are adequately measured?

In this article it is argued that while differences in national-level industrial relations systems (still) matter, nowadays variables and indicators which are expressed on a sectoral level do reflect differences in industrial relations much more clearly than national-level variables do. With this in mind, this article questions and challenges the standard unit of analysis in the field with respect to its ‘usefulness’ for comparisons. This attempt might well be considered heretical, as for more than a century country variables and indicators have served as the standard unit of analysis in comparative research in the field. And there were good reasons why country variables and aggregates dominated the theoretical and empirical analysis in the past, not least of course the fact that industrial relations systems differed significantly across countries in the past. As a consequence it was possible to draw reliable and valid conclusions, and to make inferences on the reasons as well as the implications of differences in indicators between countries. As will be argued, industrial relations systems have changed over recent decades and so has the nature of the underlying data. As industrial relations systems became increasingly international, the concept of distinct ‘national’ indicators and data has also increasingly declined. However, as will be argued, this internationalisation has different consequences in different sectors of the economy and thus might explain why industrial relations systems adjusted to sector characteristics. It will be hypothesised that nowadays the sectoral context matters frequently even more than the national. In order to test this hypothesis we investigate and compare the data properties of sector and country indicators in the field of comparative industrial relations. To look at these issues in more detail we analyse key industrial relations indicators, that is, variables, in eighteen different sectors across twenty-seven EU member states.Footnote 3

‘This attempt might well be considered heretical …’

In terms of structure, the article initially discusses the reasons for the predominance of country comparisons in the field and explains why this predominance might need to be reconsidered. We then explain the empirical strategy and how we compare and measure differences in industrial relations across and between different units. This is followed by empirical analysis of the data properties of different units of analysis. Finally, the article concludes by pointing at the theoretical and methodological implications of a focus on the sector as an important level of analysis and as the relevant unit of measurement for social phenomena in the field.

THE RISE AND FALL OF METHODOLOGICAL NATIONALISM IN COMPARATIVE RESEARCH

In the majority of European countries, industrial relations systems emerged during industrialisation (Crouch, 1993; Bechter et al, 2011b). In this period trade unions and employers’ organisations were formed and they started to negotiate on work-related issues, that is, they engaged in negotiations that were then defined as collective bargaining. However, the first trade unions were formed on very regional and sectoral levels and they negotiated the first collective agreements with the employer side for this domain. This domain, with a relatively limited regional radius and sectoral outreach, reflected the relevant economic and social context in which industrial relations took place (Hyman, 2001). Therefore from a methodological perspective the first ever unit of analysis was the regional and sector level. But over time the context for industrial relations changed.

Along with the evolution and strengthening of nation-states in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the national economic and political context became increasingly important for industrial relations. Industrial relations institutions, actors and processes adapted, and transformed along with the changing context (Brandl and Traxler, 2011). The national embeddedness of industrial relations systems in specific national, economic, and political systems, and regimes became increasingly influential for shaping distinct national industrial relations systems. As countries developed differing economic and political systems over the early twentieth century, so too did industrial relations structures evolve in differing institutions. Given that the majority of nation states in Europe were politically independent and that almost all economies were highly closed markets, national differences in industrial relations could evolve independently from other countries. Moreover, industrial relations systems were shaped and formed by country-specific political and economic peculiarities and factors which interacted with the distinct needs of the individual national economy and society.

Consequently, the principle of methodological nationalism in research into these systems was the right way to understand and explain different industrial relations systems in different nation-states – that is, countries. As nation-states still exist and national political systems show significant differences between countries, the national context is, of course, ‘still’ relevant on industrial relations systems. Consequently, there are ‘still’ good reasons to rely on some research questions on the principle of methodological nationalism for the understanding of industrial relations systems, in particular to understand and explain the transformation of industrial relations systems over a long period of time. For this reason the most important text books in the field that are currently available ‘still’ make comparisons almost exclusively between countries (e.g., Ferner and Hyman, 1998; Bamber et al, 2010; Arrowsmith and Pulignano, 2013).

Even though there is no doubt that in Europe the political context for industrial relations continues to be predominantly shaped by national peculiarities and national factors, the relevance of the economic context has shifted in recent decades away from the national towards the international. In Europe, in part because of the enlargement of the EU and the introduction of the Euro, competition between countries has increased and national economies have become increasingly open and interdependent. The economic crisis which arrived in Europe clearly showed that European economies are not only dependent upon each other, but also upon global developments. Thus, it is evident that the international economic context has gained increasing relevance for national economies.

Even though there is little doubt that the internationalisation of economies has increased in general, one has to keep in mind that there are still differences in the degree of internationalisation across different sectors within countries. Not all sectors are (directly) exposed to international competition and there are sectors in national economies which do not face competition from abroad. A ‘classic’ example is the public sector within states, which is still very ‘national’ in its nature. The public sector predominantly (but not exclusively) serves national needs, is embedded in national societal and political contexts, and is frequently not exposed to international competition. However, as the last few decades have shown, the public sector has witnessed substantial changes and transformations that have made the public sector increasingly similar to the private. For example the ‘new public management paradigm’ became increasingly important in many countries and public services were increasingly outsourced to private sector providers and employee relations became increasingly private sector like (Bach and Bordogna, 2011). The railway sector provides a good example of this trend. Developments such as these in the public sector have gained additional momentum since the onset of the crisis in 2008 to such an extent that the public sector might soon lose its position as the ‘standard’ example for a ‘sheltered’ sector.Footnote 4 But despite these pressures and in the face of such a dire prediction, it is nevertheless the case that important segments of the public sector in many countries are still not exposed to international competition (e.g., public administration) and thus are still different in their nature to sectors which are highly integrated in international markets, that is, are very international. A manufacturing sector such as steel, for instance, shows the different dimensions of a highly international sector. The steel sector is characterised not only by the presence of many multinational companies who also compete on a global scale but in addition, the location of production is (often highly) transferable. To this end, many companies in this sector do re-locate their production from country to country and are not bound to any national ‘constraints’ (Bechter et al, 2011a).

Assuming that industrial relations systems transform according to the economic and political context as they did in the past (Crouch, 1993; Brandl and Traxler, 2011), these differences in the economic context of sectors can be used to explain differences in distinct sectoral systems. While it might be expected that this transformation materialises in international sectors, it might also be the case that in ‘local’ sectors no transformation takes place. At the same time it can be expected that transformation materialises to a greater extent in those countries that are more open than others as opposed to those countries that are (relatively) closed and ‘sheltered’ from international competition. Under the assumption that the economic, that is, market, context shapes industrial relations systems, it can be expected, in line with the Varieties of Capitalism approach (Hall and Soskice, 2001), that the transformation is stronger in countries in which market mechanisms are more important for the coordination of firm activities, than in countries in which non-market mechanisms are paramount.

This kind of development of industrial relations systems in different sectors within an economy was hypothesised for example by Katz and Darbishire (2000), Meardi (2004) and Bechter et al (2011a, 2012). In this literature various examples and scenarios of different developments in sectors are discussed and the causal relationships are explored. For example, employees in ‘economically prosperous’ sectors might become a member of a trade union in order to strengthen their bargaining power to increase wages because the economic situation allows higher wages. If this is the case, this is the explanation as to why in these sectors aggregate unionisation is high. On the other hand, it might be seen as senseless for employees in sectors that face tough international competition to be a member of a trade union because the companies in the sector cannot afford higher wages. Aggregate membership figures for this sector would show a low degree of unionisation. Similar incentives exist for companies to join an employers’ organisation if it is possible to define working conditions by collective agreements which all employers must follow. In any case, if there are differences in the economic context for sectors, different developments in industrial relations systems can be expected which are expressed in differences in the aggregate figures.

From a methodological perspective, the consequence of such a development along sectoral demarcations, and given that the economic situation is different between sectors, is that the variation in figures between sectors is increasing. However it would also mean from a national perspective that the differences would decrease. Now the important question is whether the sectoral or the national context matters more? Of course both matter, but which one ‘dominates’ the shaping of industrial relations systems more than the other one? In other words, the question is whether or not the increasing internationalisation has already blurred national systems, expressed by its different indicators, in such a way that differences have disappeared or not.Footnote 5

‘Now the important question is whether the sectoral or the national context matters more.’

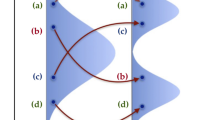

One important indicator of an industrial relations system is trade union density (Vernon, 2006), which is defined as the share of employees who are members of a trade union compared with all employees in the relevant unit. In Figure 1 histograms are presented that show the distribution of trade union density across sectors within a country as well as across countries within a sector. The histograms are used to illustrate the sector and country variation in a graphical demonstration of the distribution of data, that is, of how similar (or different) trade union density is in different sectors in a country and how similar (or different) it is in different countries in the same sectors. The variation is based on all EU member states (excluding Croatia) and eighteen sectors (see the appendix for details on the sectors). For reasons of space ‘only’ four sectors and countries are selected for illustration in Figure 1. The rationale behind the selection of the four countries and sectors is that typical country examples for different industrial relations systems are included and sectors that differ significantly regarding their degree of internationalisation are included. The selected countries correspond with the classification of industrial relations systems by the European Commission (2009): Denmark is an example of the ‘Nordic’ system, Greece of the ‘Mediterranean’ system, Germany of the ‘Continental European’ system, and Bulgaria of the ‘Liberal’ and ‘New Member States’ system. As regards the sectors, two ‘international’ and two ‘local’ sectors are included. While the Hotel, Restaurant and Catering (Horeca) sector represents a service sector which is very local, the sector also contrasts with Education as another local sector that is peculiar because it is part of the wider public sector and thus might show peculiarities. The other two sectors (Electricity Coastal, and Water Transport) are both deeply embedded in an international market but differ widely in the nature of their products. The idea behind the selection of the country and sector is based on the principle of (ideal) typical cases so that differences can be clearly illustrated and easily identified. In between the typical cases however, there are many other cases. In fact, both sectors and countries as units of analysis show a within-variation over sub-units. In some sectors, different economic sub-activities vary significantly regarding their degree of internationalisation. A good example is the banking sector where ‘the market’ in retail banking is very local, but marketing-related activities and investment banking are often highly international. Even though there is an additional within-variation in sectors, aggregate-sector differences in the local and international nature of different sectors are still relevant. The examples shown in Figure 1 illustrate these differences.

Histograms of trade union density for four countries and sectors.

(a) Bulgaria [9];

(b) Denmark [5];

(c) Germany [7];

(d) Greece [4];

(e) EDUCATION [7];

(f) ELECTRICITY [15];

(g) HORECEA [15];

(h) SEA [4].

Note: Bars show the absolute frequencies of union density intervals. For reasons of better illustration for all countries and for the ELECTRICITY sector 20 per cent intervals were chosen and for sectors, for all other sectors 10 per cent intervals were used. The maximum absolute number for each chart is shown in brackets. Lines indicate the fitted normal distribution. For further information on variables and sectors see Table A1.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the histograms are very different for the four countries and sectors. Figure 1 shows that in Denmark and Greece trade union density is very different in different sectors. In both countries there are sectors that are characterised by a density of more than 80 per cent while there are other sectors in which trade union density is not even 20 per cent. Thus the variation within both countries across different sectors is very high. While in Bulgaria the vast majority of sectors are not highly unionised. Consequently the country average is not only very low but also the standard deviation (over different sectors) is low. This is relatively similar to Germany where the majority of sectors show a density of up to 40 per cent. Even though the average trade union density in Germany is higher than in Bulgaria, the standard deviation is relatively low. By looking at variation of trade union density in the four sectors across twenty-seven EU member states again different forms of the histograms can be observed. There are sectors in which the variation across countries is very low such as in Horeca and Electricity. The histograms for both sectors show that trade union density is relatively similar throughout almost all EU member states. Although to a lesser degree, the histograms for the sectors Sea and Coastal Water Transport, as well as for Education, show that unionisation is very similar in the sectors across national demarcations even though the sector averages differ significantly.

By looking at the different histograms, that is, within unit and across unit variation, the methodological question arises as to what are the implications of these differences for comparative research in the field? For example, country averages, which are based on a high variation across sectors, might not be ‘representative’ or ‘typical’ for the situation in a country, as it does not reflect the situation for the vast majority of employees. In other words, if averages in the unit (e.g., country) show a high within-variation across another unit (e.g., sectors) any comparison might be impeded and blurred. The preferable unit of analysis is the one that shows the aggregates with the lower variation. Now the relevant question is which unit shows the lower variation across the other unit. Is the variation within sector (across countries) or the variation within a country (across sectors) lower? According to our discussion on the relevance of the country and sector context, we are able to derive the hypothesis that the sector context matters more nowadays than the country context and thus that the variation in industrial relations systems within a sector (across countries) is lower than within a country (across sectors). In other words, industrial relations systems are nowadays more homogeneous on a sectoral level than on a country level within Europe. However, as there are both differences in the economic context of countries and sectors, that is, the degree of internationalisation is different in different sectors and countries, there might still be significant differences across sectors and countries. Nevertheless, as the EU member states are already very international (or at least European), and ‘sheltered’ sectors are becoming increasingly ‘unimportant’ (e.g., the public sector is shrinking in almost all countries and the ‘new public management’ made the public sector increasingly private sector like), we might already expect that on average the sectoral unit of analysis shows a lower variation across countries than vice versa.

‘… the sector context matters more nowadays than the country context …’

Even though trade union density is a key indicator of an industrial relations system, we analyse this hypothesis on the basis of a larger set of indicators. Therefore, in the following we do not only look at differences in trade union density but also at other key indicators of a industrial relations system, that is, on the number of trade unions and employers organisations (as an indicator of the fragmentation of the system) as well as the representativeness of them. So in addition to union density, employers’ organisation density is also considered to complete the system. In addition, the relevance of collective bargaining, expressed by collective bargaining coverage, and the mode of collective bargaining, that is, what is the share of multi- and single-employer bargaining, is also analysed. Thus similar indicators of industrial relations systems as by Bechter et al (2011a, 2012) are used. However, in contrast to previous studies, a much larger set of sectors is considered and analysed which enables generalisable conclusions to be drawn here.

THE INDICATORS AND VARIABLES OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS SYSTEMS

Industrial relations systems are characterised by various dimensions of its institutions, actors, and processes. Consequently industrial relations systems are described by indicators, that is, variables, ranging from the representativeness and fragmentation of its actors (i.e., trade unions and employers’ organisation) to the mode and relevance of collective bargaining. For this reason, we analyse the variation of industrial relations systems within and across different units of analysis on the basis of six indicators. These variables used here are: the number of trade unions (#U), the number of employers’ organisations (#E), trade union density (UD), employers’ organisation density (ED), collective bargaining coverage (CBC), and the mode of collective bargaining (CBM). These six variables represent a kind of ‘standard’ set of indicators for industrial relations systems for which the importance is repeatedly argued (e.g., Clegg, 1976; Vernon, 2006; Traxler, 2010) which are usually used in comparisons and for various debates (e.g., Traxler et al, 2001; Marginson and Sisson, 2004; Bechter et al, 2011a, 2012).

The empirical analysis of the country and sector variation is based on data provided by Eurofound’s (2015) so-called sectoral representativeness (of social partners) studies, which covers sectoral and national data on industrial relations indicators for all current EU member states (with the exception of Croatia) and for more than thirty sectors. The representativeness studies provided by Eurofound are the only source which provides systematic and comprehensive information, and data on sectoral industrial relations indicators for all EU member countries. The reason why Eurofound provides this detailed sectoral information about industrial relations derives from the aim of the European Commission to monitor and evaluate the representativeness of social partner organisations which take part in the European Sectoral Social Dialogue. This ‘political’ rationale behind the data collection explains the intense efforts undertaken by Eurofound to collect the information. For example, a network of (national) experts who are familiar with distinct country and sector peculiarities is employed in order to generate comparable data. Nevertheless for many of these thirty sectors the availability of data on various important dimensions is very limited so that not all sectors were considered suitable here for the analysis. In addition, the sample of sectors provided by Eurofound (2015) includes sectors with a high number of employees as well as sectors with a relatively low number. In the sector sample covered by Eurofound there is also a bias towards agricultural sectors in the broader sense. The analysis here aims to compare sectors which differ in their degree of internationalisation as well as represent a broad variation of different sectors in an industrial economy. In addition, the selection of sectors that underpins this research is based on the principle that a high variance of sector-specific contextual properties is included. Such different sector-specific properties are usually different in manufacturing and service sectors as they markedly vary in their degree of internationalisation. This difference applies not only to the sector products, but also to the international transferability of the location of production. Given the availability of data therefore, the empirical analysis is based on data for eighteen sectors in twenty-seven EU member states which meet the selection principle outlined earlier.Footnote 6

The sectors can be classified according to the Nomenclature statistique des activités économiques dans la Communauté européenne, that is, the NACE code, which groups different economic activities. These economic activities do not necessarily match directly with the organisational domain of industrial relations actors in all countries and sectors. In fact, an exact overlap is the exception rather than the rule. For this reason Eurofound corrects sectoral data accordingly. For example, the organisational and institutional domain in some trade unions in some countries covers a number of sectors wheree in other sectors and in other countries there are different trade unions for different sub segments of sectors. Eurofound corrects for differences in different sectors and countries in order to allow cross-country and cross-sector comparisons on the basis of the same domain.Footnote 7

In order to test if the sample selection caused any bias in the results, various tests of robustness have been carried out by investigating a lower number of sectors as well as by considering further sectors. As all tests underline the results shown in the following, the empirical results of the theoretically most reasonable set of sectors for which data are available are presented.

In sum, 486 cases are considered and are available to test the respective unit variation (18 sectors × 27 countries=486 cases). Each of these cases is described by the six key indicators, or variables respectively, of the industrial relations system, that is, by #U, #E, UD, ED, CBC, and CBM. Compared with previous studies, this sample size is far larger (e.g., Katz and Darbishire, 2000; Meardi, 2004; Bechter et al, 2011a; Bechter et al, 2012) and thus allows a much higher degree of generalisability of the results.

THE VARIATION ACROSS COUNTRIES AND SECTORS

Given this definition of industrial relations systems and given the data available, the question of which unit of analysis shows the lower within-variation can be addressed. In other words, the question can be addressed whether or not the traditional unit of analysis, that is, the country level, is already so ‘blurred’ that the unit of analysis might be reconsidered. In order to measure the unit variation, the coefficient of variation (CoV) is used which is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean. The CoV is a normalised measure of dispersion of a frequency distribution and shows the extent of variability in relation to the mean of the sample. In the following empirical analysis, we investigate the CoV for all six industrial relations indicators for countries calculated across all eighteen sectors and for sectors across twenty-seven EU member states. One advantage of the CoV is that the interpretation is very simple: the higher the score, the higher the variation. Another advantage is that it is a normalised measure which is independent of the scale. For this reason, it is possible to calculate the average CoV over the six indicators and use it as a measure of the variation for the whole industrial relations system. In the following, the CoV for all member countries (across the eigteen sectors) is shown for all six indicators and for the average over the six indicators.

As can be seen in Table 1 the variability of each individual industrial relations indicator as well as for the system (i.e., the average of the six indicators) across different sectors within each country is very high in some countries but relatively low in others. In Poland, the variation in the industrial relations system is the highest which means that there are sectors in which the figures for all indicators are very high but there are also sectors in which the figures are completely different, that is, figures show very low values. This means that there are sectors in Poland which are (i) highly unionised, (ii) the majority of employers joined an employers’ organisation, (iii) there are many unions, (iv) employers’ organisations, (v) the mode of collective bargaining is predominantly multi-employer bargaining, and (vi) the majority of employees are covered by a collective agreement. It also means that it is completely the other way round in other sectors in Poland. Thus it would be difficult to speak of a ‘typical’ Polish industrial relations system, as any Polish average is ‘blurred’ because of the variation across sectors.

A similar high CoV can be observed for Latvia, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Malta, the United Kingdom, and the Czech Republic. But there are also countries in which the variation of the industrial relations system is very low, in particular such as Finland, Sweden, Belgium, Austria, and France. In these countries the industrial relations system has about the same characteristics in almost all sectors. This does not mean that the system is the same in all countries as the averages might (and actually do) differ significantly. Overall, countries with a Liberal and Mediterranean system show a higher within-country variation than countries with a Nordic and Continental European system of industrial relations. This result of different country variations is basically consistent with the ‘Varieties of Capitalism’ (Hall and Soskice, 2001) expectation that market mechanisms and the market context is more important in countries with liberal market economies than in coordinated market economies.

Analogous to Table 1, Table 2 shows the CoV for all sectors (across the twenty-seven countries), again for all six indicators and for the average over the six indicators.

Table 2 shows that industrial relations systems show a relatively high variability across countries in sectors Postal and Public Administration. This means that in these sectors industrial relations systems are relatively different between countries. But there are also sectors which show a (very) high degree of similarities in different countries. In particular in the sectors Metal, Electricity, Insurance, Banking, and Footwear, industrial relations systems have the same characteristics in almost all member states of the EU. Again, this does not mean that these sectors do not differ from each other but that in each of the sectors very similar industrial relations characteristics can be found in almost all EU member states. Overall, the international sectors show more similarities across countries than the ‘sheltered’ or ‘local’ sectors.

In Tables 1 and 2 differences in the CoV can be observed. However, the relevant question here is what is the implication of these different CoVs for the choice of the unit of analysis in comparative research. As explained earlier, a unit with a high CoV might not be ‘representative’ or ‘typical’ for the situation in a country or sector respectively. The preferable unit of analysis is the one that shows the lower CoV over all relevant countries or sectors. Figure 2 shows and compares the CoVs of the industrial relations system for both units, that is, for countries and sectors.

Coefficient of variation of industrial relations systems across countries and sectors.

Note: Black bars show the average coefficient of variation (CoV) for all six industrial relations indicators for countries calculated across all 18 sectors and the white bars for sectors across 27 EU member states. Dotted line shows the average CoV of the country unit (0.77) and the dashed line the average CoV of the sector unit (0.69). For further information on variables and sectors see Table A1.

As can be seen in Figure 2, the question of whether the variation within sectors (across countries) or the variation within countries (across sectors) is lower can be answered, as the CoV is significantly lower on the basis of the sectoral unit, compared with the country unit. The difference in the CoV is supported by a t-test which shows a significant difference (p-value<1 per cent). The difference is confirmed not only for the overall industrial relations system but also for each individual dimension. In order to test the robustness of the results regarding the selection of sectors, which was based on the principle that a high variance of sector-specific contextual properties is included, larger and smaller sector samples were tested which all confirm the analysis.Footnote 8

Therefore, the bottom line of the empirical analysis is that we are able to accept the hypothesis. The results show that the hypothesis that the sector context matters more nowadays than the country context is valid and thus that the variation of industrial relations systems within a sector (across countries) is lower than within a country (across sectors). Consequently the sectoral unit of analysis is preferable from a methodological perspective.

CONCLUSION

WHAT IS THE RELEVANT UNIT OF ANALYSIS IN COMPARATIVE RESEARCH?

‘… the sector context matters more nowadays than the country context …’

In this article we addressed the question of which unit of analysis offers more advantages in comparative research in the field of industrial relations. By doing so, we inevitably revisited the concept of national, that is, country, comparison in the field of comparative industrial relations research and the use of national data as well as the role of ‘methodological nationalism’. We explained the reason for the dominance of the principle of ‘methodological nationalism’ in past and current research and the predominant focus on country comparisons in the discipline, but raised the hypothesis that nowadays, from a methodological perspective, sectoral comparisons might be preferable for a number of research questions. We grounded this hypothesis on the basis of changes in industrial relations systems over the recent past which had implications for the nature of the underlying data used in research. It was empirically shown that (on average) sector industrial relations systems share more similarities across countries within a certain sector than country industrial relations systems across sectors within countries. In fact the empirical analysis showed that sector industrial relations systems differ more than country industrial relations systems. This empirical result confirms previous case study examples which argued that a number of sectors do not correspond anymore with ‘traditional’ national system characteristics (e.g., Katz and Darbishire, 2000; Meardi, 2004) and challenges to a certain extent the concept of the existence of distinct ‘national’ industrial relations systems.

However, the methodological implication is that sector comparisons of industrial relations indicators provide a ‘clearer’ picture of differences in different industrial relations systems compared with comparisons of national aggregates. The reason for this is that, on average, sector industrial relations systems show more similarities across countries that is, have a low variance across countries, than country industrial relations systems across sectors within the country. In other words the results mean that any country averages of industrial relations systems are more ‘blurred’ and vary to a higher extent, than sector averages. The difference in the variation is statistically significant so that (on average) the sector unit of analysis is preferable from a methodological perspective compared with the country unit. This result holds for the averages across sectors and countries but not necessarily for all sectors and countries.It is important to point out that the result that sector comparisons could offer ‘more’ advantages than country comparisons is not only a comparative one (country versus sector comparison only), but also an empirical advantage relating to statistical data properties and refers to an analysis of the data properties of sector and country indicators of six key industrial relations indicators, that is, variables.

‘This result does not imply that national comparisons and the use of data on a national basis unit has become “irrelevant” ’

This result does not imply that national comparisons and the use of data on a national basis unit has become ‘irrelevant’. For example, there are still countries such as in particular the Nordic states with clear national industrial relations systems that differ only slightly across sectors. There are similar differences in the variation of industrial relations systems across countries between different sectors. While on the one hand, ‘local’ sectors are still very much shaped by the traditional national context, international sectors however show a clear transnational profile and do not vary much across national borders. This result supports the relevance of the economic context as the prime mover for the transformation of industrial relations systems.

Even though the difference between the country and sector variation is (statistically) significantly different, the difference in the variation between the two units might be considered minor as it is impossible to assess the exact difference for different research questions as well as there is far more data available on a national level which allows the analysis of a far wider range of research questions. We agree with all the advantages of making country comparisons in comparative research and would underline the difficulties of this ‘methodological nationalism’ for future research. This is because it is very likely that in the EU the process of internationalisation of economies or markets will continue so that the process of transformation of industrial relations systems along sector demarcations will be further enforced. Thus sooner or later, the common practice of using the national level as the unit of analysis in research needs to be reconsidered and the focus on the sectoral unit will become inevitable in order to make inferences from comparisons. This implies that from a methodological perspective it appears to be advantageous in the field of comparative industrial relations research to increase data collection efforts on a sectoral basis. Given that both the national and sectoral level matter in the field of comparative industrial relations, the availability of data on both units would enable a combined analysis of both sections.Footnote 9 A combined analysis would permit a more integrated and comprehensive understanding of causal mechanisms evident on different dimensions in the field of comparative industrial relations.

Notes

For a recent and comprehensive overview of reforms and changes see for example European Commission (2015).

Good examples are the theoretical and empirical debates on the role of the institutional structures of collective bargaining by Calmfors and Driffill (1988), Soskice (1990), and Traxler (1995). For more information see Brandl (2012) and for the political implications see Aumayr-Pintar et al (2014).

For reasons of availability of data Croatia was not considered in the study so that only the remaining twenty-seven EU member states were analysed.

For an overview and discussions on the impact of the NPMP in various sectors and in particular in the railway and in other sectors see for example European Commission (2013) and Vaughan-Whitehead (2013).

See for example Doellgast and Greer (2007) for evidence of German industrial relations.

For details see Eurofound (2015).

For the robustness tests various additional (sets of) sectors available by Eurofound (2015) were investigated.

For such a data structure and research question the use of a Multilevel Analysis would be advantageous.

References

Arrowsmith, J. and Pulignano, V. (eds.) (2013) The Transformation of Employment Relations in Europe. Institutions and Outcomes in the Age of Globalization, Abingdon: Routledge.

Aumayr-Pintar, C., Cabrita, J., Fernández-Macías, E. and Vacas-Soriano, C. (2014) Pay in Europe in the 21st Century, Dublin: Eurofound.

Bach, S. and Bordogna, L. (2011) ‘Varieties of new public management or alternative models? The reform of public service employment relations in industrialized democracies’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management 22 (11): 2281–2394.

Bamber, G., Lansbury, R. and Wailes, N. (2010) International and Comparative Employment Relations, London: SAGE.

Bechter, B., Brandl, B. and Meardi, G. (2011a) From National to Sectoral Industrial Relations: Developments in Sectoral Industrial Relations in the EU, Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Bechter, B., Brandl, B. and Meardi, G. (2011b) ‘Die Bestimmungsgründe der (Re-) Sektoralisierung der industriellen Beziehungen in der Europäischen Union’, Industrielle Beziehungen 18 (3): 143–166.

Bechter, B., Brandl, B. and Meardi, G. (2012) ‘Sectors or countries? Typologies and levels of analysis in comparative industrial relations’, European Journal of Industrial Relations 18 (3): 185–202.

Brandl, B. (2012) ‘Successful wage concertation: The economic effects of wage pacts and their alternatives’, British Journal of Industrial Relations 50 (3): 482–501.

Brandl, B. and Traxler, F. (2011) ‘Labour relations, economic governance and the crisis: Turning again the tide?’ Labor History 52 (1): 1–22.

Calmfors, L. and Driffill, J. (1988) ‘Bargaining structure, corporatism and macroeconomic performance’, Economic Policy 3 (6): 13–61.

Clegg, H. (1976) Trade Unionism under Collective Bargaining: A Theory Based on Comparisons of Six Countries, Oxford: Blackwell.

Crouch, C. (1993) Industrial Relations and European State Traditions, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Doellgast, V. and Greer, I. (2007) ‘Vertical disintegration and the disorganization of German industrial relations’, British Journal of Industrial Relations 45 (1): 55–76.

Eurofound. (2015) European representativeness studies, available at: http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/eiro/representativeness.htm, accessed 12 March 2015.

European Commission. (2009) Industrial Relations in Europe Report 2008, Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2013) Industrial Relations in Europe Report 2012, Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2015) Industrial Relations in Europe Report 2014, Brussels: European Commission.

Ferner, A. and Hyman, R. (eds.) (1998) Changing Industrial Relations in Europe, Oxford: Blackwell.

Hall, P.A. and Soskice, D. (eds.) (2001) Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hyman, R. (2001) ‘The Europeanisation – Or the erosion – Of industrial relations?’ Industrial Relations Journal 32 (4): 280–294.

Katz, H. and Darbishire, O. (2000) Converging Divergences: Worldwide Changes in Employment Systems, Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

Marginson, P. and Sisson, K. (2004) European Integration and Industrial Relations. Multi-level Governance in the Making, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Meardi, G. (2004) ‘Modelli o stili di sindacalismo in Europa?’ Stato e Mercato 71 (2): 207–235.

Meardi, G. (2013) ‘Systems of Employment Relations in Central Eastern Europe’, in J. Arrowsmith and V. Pulignano (eds.) The Transformation of Employment Relations, London: Routledge, pp. 69–87.

Soskice, D. (1990) ‘Wage determination: The changing role of institutions in advanced industrialized countries’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 6 (4): 36–61.

Traxler, F. (1995) ‘Farewell to labour market associations? Organized versus disorganized decentralization as a map for industrial relations’, in C. Crouch and F. Traxler (eds.) Organized Industrial Relations in Europe: What Future?, Aldershot: Avebury, pp. 3–19.

Traxler, F. (2010) ‘The long-term development of organized business and its implications for corporatism: A cross-national comparison of membership, activities and governing capacities of business interest associations’, European Journal of Political Research 49 (2): 151–173.

Traxler, F., Kittel, B. and Blaschke, S. (2001) National Labour Relations in Internationalized Markets, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vaughan-Whitehead, D. (ed.) (2013) Public Sector Shock: The Impact of Policy Retrenchment in Europe, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Vernon, G. (2006) ‘Does density matter? The significance of comparative historical variation in unionization’, European Journal of Industrial Relations 12 (2): 189–209.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

bechter, b., brandl, b. measurement and analysis of industrial relations aggregates: what is the relevant unit of analysis in comparative research?. Eur Polit Sci 14, 422–438 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2015.65

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2015.65