Abstract

This study analyzes the relationship between information and communication technologies (ICTs) and labor productivity growth in sub-Saharan Africa over the period 1975–2010. The results show that fixed-line and mobile telecommunications have a positive and significant impact on growth after penetration rates reach a certain critical mass. The thresholds are identified using nonparametric methods. Penetrations rates of between 20% and 30% for telephones and 5% for internet usage trigger increasing returns. FDI and openness are found to improve productivity and to help ICTs boost growth. Financial development serves as a possible transmission channel for the growth-enhancing effects of ICTs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

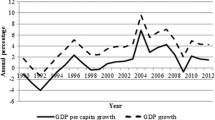

The revolution in information and communication technologies (ICTs) that gripped the developed countries in the 1980s and 1990s largely bypassed sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), leaving it on the wrong side of the global digital divide. At the turn of the century, fewer than two out of 100 people in the region subscribed to mobile cellular communication services, while only one in 200 people had access to the internet. However, over the past decade, SSA countries have experienced a dramatic surge in the usage of ICTs. By 2011, more than half of the population in the region had a mobile cellular subscription and about 13% of the population was using the internet (see Figure 1). Furthermore, the speed of internet access increased substantially from 80 Gbps in 2008 to roughly 15.7 Tbps in 2012, although the number of broadband subscriptions has been modest (International Telecommunications Union, 2012). Despite the fact that SSA still lags behind other regions regarding ICTs indicators, the rapid growth in penetration rates suggests that ICTs might play a role in improving productivity at the aggregate level.

The main objective of this paper is to evaluate the impact of ICTs on labor productivity growth in a sample of 43 SSA countries over the period 1975–2010. In particular, we estimate the effects of fixed-line telephone, mobile cellular, and internet usage on productivity growth by employing system Generalized Methods of Moment (SGMM). Some empirical studies (Roeller and Waverman, 2001; Sridhar and Sridhar, 2007; Gruber and Koutroumpis, 2011) have explored this topic by adopting an annual production function framework. By relying on annual data, this approach risks spurious estimates due to measurement errors and endogeneity bias (Waverman et al., 2005). Another group of studies has applied an alternative model based on Barro’s (1991) endogenous technical change approach (Waverman et al., 2005; Kathuria et al., 2009). It postulates that ICTs levels in a given year affect productivity growth over following periods, which addresses the main issues associated with the method based on annual data. Accordingly, in this study, we employ Barro’s (1991) framework and set the ICTs variables at their initial values at the beginning of each period.

Previous studies using cross-country data have established the presence of nonlinear effects of ICTs on growth (Gruber and Koutroumpis, 2011; Hawash and Lang, 2010; Vu, 2011), which are the result of network effects.Footnote 1 In line with the literature, we explore this aspect by including polynomial terms into the regression model. In addition, we use a nonparametric specification that is more flexible and has the added advantage of allowing us to determine the thresholds for the network effects.Footnote 2

Consistent evidence in literature points to the growth-enhancing effects of ICTs in developing (Roller and Waverman, 2001; Sridhar and Sridhar, 2007; Kathuria et al., 2009; Hawash and Lang, 2010) and developed (Oliner and Sichel, 2000; Oulton, 2002; Jorgenson, 2003; Jimenez-Rodriguez, 2012) countries. While evidence from SSA is still scarce, the few existing studies have found a positive linkage between growth and ICTs in SSA (Lee et al., 2012) and in African countries in general (Andrianaivo and Kpodar, 2011; Gyimah-Brempong and Karikari, 2010).

The nexus between ICTs and productivity change in SSA is worth investigating for several reasons. First, the rapid penetration of mobile cellular technology and the internet in these countries overlapped with a period of robust growth in the region. The boom in commodity prices on world markets has certainly benefited many African countries that are dependent on primary exports. Debt relief initiatives, better macroeconomic policies, and a more stable political environment have also played a role (World Economic Forum, 2013; Yonazi et al., 2012; Wamboye and Tochkov, 2014). But it is also reasonable to expect that the ICTs revolution has contributed to this growth experience in SSA.

Second, there is ample anecdotal evidence of highly successful business initiatives in SSA that rely on mobile cellular technology to boost productivity across entire sectors but estimates of these effects at the aggregate level are rare. Over the past decade, mobile financial applications have emerged across Africa that facilitate various financial transactions, such as storing and transferring money and paying bills. For instance, the mobile platform M-PESA, pioneered in Kenya, has spread across six other African countries and allows users to create e-bank accounts and complete financial transactions via their mobile phones. In Kenya alone, active bank accounts in M-PESA have grown fourfold since 2007 (Yonazi et al., 2012). Another sector that has been affected by the ICTs revolution is agriculture. In Niger, a new platform allows irrigation systems to be controlled remotely via mobile phone. Esoko, a mobile communication service from Ghana and its competitor, M-Farm, from Kenya, provide users with agricultural market information, such as up-to-date prices and their recent trends, weather forecasts and alerts, and crop production levels that help farmers improve their productivity.

Third, access to fixed-line telephones in SSA has barely doubled over the last four decades and is among the lowest in the world, with an average of one line per 150 people. Mobile communication, which requires significantly smaller amounts of investment in physical infrastructure (relative to fixed-line telephone), offers a unique opportunity to bypass many of the constraints that have prevented the diffusion of ICTs in developing countries. However, other barriers that are more relevant with regard to productivity gains remain. For instance, low levels of human capital, lack of healthy competition on the ICTs market, and lack of information-oriented business processes in SSA could hinder the adoption of modern technology (Kimenyi and Moyo, 2011; World Economic Forum, 2013). This raises an important policy concern on whether ICTs have indeed had a meaningful impact on the observed growth in SSA.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section and the section following it explain the methodology and data sources, respectively. The penultimate section reports the results and the final section concludes.

METHODOLOGY

The effects of ICTs penetration on labor productivity growth are estimated for a sample of SSA countries using the following baseline regression specification:

where y it is the natural logarithm of real output per worker in country i at time t. Country-specific and time fixed effects are denoted by υ i and η t , respectively, while ɛ it is the standard error term. Δy it stands for the average annual growth rate of output per worker in country i between the years t−τ and t, where τ takes the value of 3.Footnote 3 In line with the growth literature, we average labor productivity growth across 3-year non-overlapping periods to control for the reverse causality bias and to minimize the effects of short-run cyclical fluctuations and outliers.Footnote 4 All independent variables in the model are specified as initial values at the beginning of each 3-year period to capture the idea that they affect labor productivity growth over subsequent years.Footnote 5 We follow closely the standard growth literature (Barro, 1991; Levine and Renelt, 1992; Sala-i-Martin et al., 2004) in selecting the core set of growth determinants. Notwithstanding, our choice of variables is constrained by data availability, limiting us to those core variables whose meaningful data is available during the specified sampling period.

The main right-hand side variable is ICTs, which is measured by the number of fixed-line telephone subscribers, mobile cellular subscribers, and internet users, all expressed per 100 people. These three measures are used as proxies for technology adoption. As suggested by previous studies, we take into account the impact of network effects by including quadratic terms of the ICTs variables into the model (Hawash and Lang, 2010; Ketteni et al., 2006).

Long-term private international capital flows, such as foreign direct investment (FDI), have been viewed as complementary and catalytic agents in building and strengthening domestic factor productivity with inherent tangible and intangible benefits such as contributing to export-led growth, technology and skill transfer, and employment creation. In addition, human capital accumulation, proxied by education (EDU), directly adds to labor productivity and indirectly leads to efficiency gains through more rapid adoption of technology. A country with high levels of human capital is more likely to attract investors, to have the capacity to absorb new ideas, and to engage in research and innovations (Grossman and Helpman, 1991). While it is hard to ascertain the sign of the human capital proxy prior to empirical estimations, we expect FDI inflows to have a positive effect on productivity growth.Footnote 6

Trade openness (OPEN) encourages competition on the global market, which in turn drives the export sector to adopt the latest technology and the most efficient practices of production, thereby increasing labor productivity (Grossman and Helpman, 1991; Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 1995; Dollar and Kraay, 2004). In addition, with increasing integration in the global economy, countries can achieve productivity gains through specialization driven by comparative advantage. The sign of the coefficient on trade openness variable is, however, unpredicted prior to our empirical investigations.Footnote 7

Our regression model further includes a fiscal policy variable proxied by government consumption spending (GOV).Footnote 8 High budget deficits have been found to have negative effects on productivity growth (Fischer, 1993). As a fiscal policy instrument, government consumption expenditure can be used during economic downturns to stimulate aggregate demand and, hence, growth. Moreover, in some parts of developing countries, such as rural areas, where ICTs infrastructure-related development has lower private sector participation due prohibitive sunk costs, public sector participation implies increasing government consumption spending. However, if the spending is politically motivated or results in corruption, it could have negative consequences on the medium- and long-run productivity growth. The proportion of money supply (M2) in GDP is used as a proxy for the depth of the financial market development (FIN), which has been shown to accelerate economic growth (Beck et al., 2000; King and Levine, 1993). Furthermore, investment spending (INV) is included to capture the effects of overall domestic investment activities on labor productivity growth.

In addition to economic variables, we also control for the effect of institutional factors proxied by a measure of governance (INST). Good governance, political stability, and high institutional quality have been shown to provide conducive environment for economic and productivity growth (Acemoglu et al., 2005; Rodrik et al., 2004; Beck et al., 2000).

The model in Equation 1 exhibits a number of methodological issues. Endogeneity bias may arise due to the potential endogeneity of labor productivity growth determinants such as ICTs, human capital, and governance variables.Footnote 9 On the other hand, it is possible that low productivity growth may cause low investment in ICTs, while increased investment in ICTs may cause high productivity growth, or that both ICTs investment and productivity growth may be jointly determined by a third variable. In such instances, the model will suffer from reverse causality and simultaneity bias. Other biases that may affect the consistency of the estimates include the heterogeneity (omitted variable) bias and measurement error (in the independent variables).

A stylized approach in the literature to correct the endogeneity bias is to use lagged instrumental variables. However, the problem of finding appropriate and strictly exogenous instruments that are correlated with the endogenous X-variables but are uncorrelated with the model error term, still looms (Wooldridge, 2010). The System Generalized Method of Moments (SGMM) approach of Arellano and Bover (1995) and Blundell and Bond (1998), on the other hand, is used to control for the endogeneity bias, measurement bias, unobserved country fixed effects, and heterogeneity bias.Footnote 10 Relative to difference GMM and other instrumental variable estimators, SGMM is robust to weak instrument bias. It uses suitable lagged levels and lagged first differences of the regressors as their instruments. Additionally, all our samples meet Roodman’s (2006) requirement of large N and small T when using GMM as the estimation technique. In accordance with GMM estimation techniques, the Sargan test of over-identifying restrictions and the Arellano-Bond test that the average autocovariance of residuals of order two is zero are reported. In all specifications, time dummies are included to remove universal time-related shocks from the errors (Roodman, 2006).

We conduct other diagnostic tests. We test for unit root in each variable in the 1975–2010 sampling period using Im–Pesaran–Shin (1997) unit-root test. The null hypothesis of unit root in all panels is rejected only in the real GDP per capita growth variable. However, we could not reject the null hypothesis for the rest of the variables. To solve this problem, we take a first difference on the data. Unit-root tests based on the differenced data rejected the null hypotheses. Consequently, all our regressions are based on the equations with the unit-root corrected data.

DATA

The analysis is conducted using a sample of 43 SSA countries over two sampling periods: 1975–2010 and 1995–2010. Mobile cellular subscriptions and the number of internet users’ data are available from the early 1990s onwards. Consequently, the 1995–2010 sampling period includes the mobile cellular subscriptions and internet users as the two measures on ICTs adoption. In the longer sampling period (1975–2010), we measure ICTs effects with fixed-line telephones and the sum of mobile cellular and fixed-line telephone subscriptions. All three ICTs indicators are expressed per 100 people and the corresponding data were obtained from the World Bank’s African Development Indicators online database. Data on human capital (measured as the gross enrollment ratio for primary education), net inflows of FDI (as percentage of GDP), and financial deepening (proxied by money and quasi money (M2) as percentage of GDP) were downloaded from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators online database.

Output per worker is expressed in purchasing power parity terms and constant 2005 international dollars. Government consumption spending, trade openness, and investment spending are measured as percentage of GDP. All aforementioned variables were collected from the Penn World Table version 7.1 (Heston et al., 2012). Institutional factors are represented by the Polity Index reported by the Polity IV Project (Marshall and Jaggers, 2011). The index is measured on a scale ranging from −10 (strongly autocratic political system) to +10 (strongly democratic political system).

Table 1 contains the sample of countries used in the study. The descriptive statistics and correlation/covariance matrix for selected variables are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

Tables 4 and 5 report the results of the baseline regressions for the 1975–2010 and 1995–2010 periods, respectively. The estimated coefficients of the control variables are largely consistent with the findings in the growth literature. The results provide evidence of β-convergence among SSA countries as the initial level of real GDP per worker is negatively correlated with consequent growth across all models. Where significant, the coefficients for good governance, financial development and investment enhance growth, while government consumption spending retards growth. These findings are consistent with related literature discussed in the preceding analysis.

In Table 4, we report the estimated coefficients of the two ICTs indicators (fixed-line telephones and the sum of fixed-line and mobile cellular variables) for which data are available over the period 1975–2010. In particular, an increase by 10 percentage points in the penetration rate of fixed-line telephones decreases productivity growth by approximately 3.17%–3.42% per annum over the subsequent 3 years (columns 1 and 2). Doubling that rate increases growth by roughly 0.12%–0.15% annually over the next 3-year period. These increasing return effects on growth are also observed when the measure of ICTs is specified as the sum of the mobile cellular and fixed-line telephones. The coefficients of the linear and quadratic terms have negative and positive effects, respectively, with the magnitude of 1.72%–1.97% (linear) and 0.02% (quadratic), for every 10% increase in the combined number of subscribers of fixed-line and mobile cellular telephones (columns 3 and 4).

The social benefits of ICTs infrastructure and services, similar to education and healthcare, outweigh the private benefits, whereby their values increase with the size of the network. For example, the greater the number of people immunized for tuberculosis in a society, the lower will be the infection rate. Similarly, the larger the number of subscribers to, for example, mobile cellular services, the more information will be shared and the wider will be the usage of growth-enhancing mobile applications related to healthcare, banking, and agriculture. Also, in countries where investments in ICTs are predominantly driven by the private sector, the size of the network determines the quantity of ICTs-related investments and innovations, and the variety of services provided. By implication, the network effects are relevant to the effectiveness of ICTs on growth. Grace et al. (2003) warn that if indeed ICTs’ network effects are at play, some poor countries might fall into a poverty trap. This is especially true for SSA countries where many poor households have been found to allocate their limited resources toward mobile phones services at the expense of traditional necessities. Moreover, from a macro perspective, a certain network threshold is necessary to justify the initial ICTs investment-related sunk costs.

Our findings above reveal that indeed there exists a robust nonlinear relationship between growth and fixed-line and mobile cellular telephony, consistent with the literature on network effects (Roller and Waverman, 2001; Grace et al., 2003) and the conclusion arrived in Dedrick et al. (2013). Gyimah-Brempong and Karikari (2010) found network effects for fixed-line telephony in a sample of African countries, while Kathuria et al. (2009) reported such effects for mobile cellular telephones in a sample of 19 Indian States.Footnote 11 Therefore, our results imply that if SSA countries want to benefit from the productivity-enhancing effects of ICTs, they should boost investment in ICTs and other complementary infrastructures (Dewan and Kraemer, 2000). In addition, they should create universal service policies and appropriate competition-oriented regulation, which are necessary to lower the cost of the ICTs services and increase the subscription rate.Footnote 12

Furthermore, the estimates in Table 4 suggest that doubling the penetration rate of fixed-line telephones produces larger benefits for productivity growth than mobile cellular (columns 1 and 3).The higher returns can be explained by the strong correlation between fixed-line technology and other key infrastructure indicators, such as paved roads (0.81), water (0.65), and sanitation (0.85) (see Table 3). In contrast, the correlations between these infrastructure variables and mobile cellular are 0.43, 0.41, and 0.46, respectively. In general, fixed-line telephone access is more likely to be found in areas with well-developed transportation and sanitation infrastructure. This is especially true in SSA countries, where such infrastructures have a higher penetration rate than mobile telecommunication in urban rather than rural areas. In that case, the fixed-line telephone variable is acting as a proxy for a broad array of infrastructure development. Therefore, doubling the number of fixed-line telephone subscriptions signifies a general improvement in a country’s level of economic development, which, in turn, promotes other productivity-enhancing factors.

As previously noted, we evaluate the impact of mobile cellular subscriptions over the 1995–2010 period. Results in Table 5 support robust increasing returns effects similar to those observed with fixed-line telephone in Table 4. An increase in the penetration rate by 10 percentage points dampens growth by approximately 3.9%–4.1% per year over the subsequent 3-year period. In addition, the increasing returns to growth from mobile cellular telephone are robust across all specifications (columns 1–2). The magnitude of the coefficient for the quadratic term (0.05% growth increase for each 10 percentage-point rise in the penetration rate) is relatively smaller than the one for fixed-line telephones reported in Table 4 (columns 1 and 2), reinforcing the argument made above.Footnote 13

The other ICTs indicator, internet users, has neutral effects on labor productivity growth in SSA countries, which can be attributed to the relatively low number of current users, averaging 1.8% of the population (see Table 2). The technology transfer indicators, openness and FDI, have growth-enhancing effects that are robust across all model specifications for the 1975–2010 sampling period. A 10% increase in the GDP share of trade and FDI in GDP boosts labor productivity growth by about 0.84%–1.0% and 0.55%–0.60%, respectively. In the 1995–2010 period, the coefficient for FDI remains positive and robust, while openness is no longer robust, suggesting that the latter impacts growth over a longer period of time. Additionally, the magnitude of the effect of FDI inflows on growth increases in the 1995–2010 period when the internet users and mobile cellular subscription are included in the model as the only ICTs adoption indicators. For example, a 10% increase in the GDP share of FDI increases productivity growth by approximately 4.38%–5.10% per year for the next 3-years. These findings suggest the efficiency gains to FDI activities associated with ease of communication and accessibility of data via mobile cellular technology and the internet, which in turn positively impacts growth in these countries. Human capital, the technology absorptive capacity indicator, exhibits neutral effects on growth irrespective of the sampling period.Footnote 14

What is the transmission mechanism from ICTs to growth?

An area that has received little empirical attention in this line of literature is the channel(s) through which ICTs impact growth. As previously noted, ICTs, especially mobile cellular, which is popular in SSA countries relative to fixed-line telephone, may affect growth via a number of channels. Evidence of increase in employment (Chéneau-Loquay, 2008), tax revenues (GSMA, 2008), and exports (Clarke and Wallsten, 2006), among others, have been associated with the spread of mobile cellular and the internet in SSA, and in low-income countries in general. But the most intriguing of all is how mobile cellular technology has revolutionized banking and access to financial services in countries where banking infrastructure has been very weak and a large percentage of the population has been marginalized from traditional banking. The success and popularity of mobile banking platforms, such as M-PESA, Ezypesa, WIZZIT, and CELPAY in Eastern and Southern African countries, have made some scholars such as Andrianaivo and Kpodar (2011) to believe that financial inclusion is one of the major channels through which mobile cellular penetration impacts growth. For example, only 2 years after its launch of a mobile banking platform – M-PESA – in March 2007, Kenya’s Safaricom had a customer base of approximately 38% of Kenya’s adult population (Jack and Suri, 2011).

Consequently, following Andrianaivo and Kpodar (2011), we also report in Table 5 (columns 3–4) results in which the financial development variable is excluded from the regression models. We compare these results with those in columns 1–2 (Table 5) to assess the explanatory power of the mobile cellular variable. An increase in the explanatory power in models excluding the financial development variable signifies that financial inclusion is indeed one of the possible channels through which mobile cellular penetration affects growth in SSA countries.

Results reported in Table 5 (columns 3 and 4) show an improvement in the explanatory power of the mobile cellular penetration variable. For example, the coefficients for the linear and quadratic specifications are now significant at the 1% level, which contrasts with the 5% significance for the models in columns 1 and 2. In other words, when financial development is accounted for, it claims part of the impact of mobile technology on growth as reflected in the lower explanatory power of the mobile cellular coefficient. This concurs with the findings of Andrianaivo and Kpodar (2011), implying that financial deepening serves at least in part as a conduit for the effects of ICTs on growth in SSA countries.

Thresholds of the network effects

The results in Tables 4 and 5 have shown that the effects of the ICTs variables on growth are nonlinear. However, based on our empirical model we are unable to determine the thresholds for the increasing returns of ICTs. Furthermore, the quadratic term in the regression assumes the existence of only one threshold. To address these issues, we employ a nonparametric regression, which has the advantage of being very flexible in that it relaxes all assumptions about functional form and linearity. Its main disadvantage is the ‘curse of dimensionality’, which makes it difficult to fit a regression in the presence of too many predictors. For this reason, we focus on three conditioning variables that were found to be significant in the parametric model (FDI, openness, and financial development).

Given that the nonparametric regression does not yield scalar estimates of marginal effects, the results are presented in three-dimensional plots, whereby each axis denotes the average annual growth rate, the ICTs variable, and the conditioning variable, respectively. Furthermore, we show the corresponding two-dimensional growth curve profiles, which represent the nonparametric regression line of the ICTs-growth relationship for three different levels of the conditioning variable. These profiles allow us to identify the thresholds for reversals in the sign of the marginal effect.

The results for the combined variable of fixed-line and mobile cellular telephones over the period 1975–2010 are presented in Figure 2. The graphs are largely in line with the parametric results but provide a number of additional insights. For instance, higher levels of openness are associated with a stronger growth-enhancing effect of the ICTs indicator. In addition, the more open an economy is, the lower the threshold of the network effect. In particular, openness levels of 100% cause the marginal effect of ICTs to turn positive at around 80 fixed-line and mobile cellular telephones per 100 people. For levels of 150%, this threshold is reduced to below 60. More FDI also contributes to a larger marginal effect of ICTs on growth, but the threshold for the network effect remains mostly constant at around 30 subscriptions per 100 people. This is also the case when financial deepening is used as a condition variable. However, at moderate levels of financial development, ICTs seem to exhibit decreasing returns.

Results of the growth effects of fixed-line plus mobile cellular telephone using nonparametric regression, 1975–2010

Note: The 3D graphs on the left show the effects of fixed-line and mobile cellular telephones on growth, conditional on various factors. The plots on the right are the corresponding regression lines at three different levels of the conditioning variable.

Figure 3 presents the graphs for the 1995–2010 period. Each of the three ICTs variables is examined separately with FDI as the sole conditioning variable. The results indicate that fixed-line telephony does not benefit growth for higher levels of FDI. In contrast, the slope of the regression line for mobile cellular technology and the internet is generally steeper at higher levels of FDI. However, the threshold effects of the network effect differ between the two advanced ICTs indicators. For the internet, the threshold is 5 users per 100, while for mobile cellular it is around 20 subscriptions per 100. Given that the average number of internet users in SSA at less than 2 users per 100 is below this threshold, it is not surprising that we did not find a significant effect on growth in the parametric regressions.

Results of the growth effects of fixed-line telephones, mobile cellular, and internet using nonparametric regression, 1995–2010

Note: The 3D graphs on the left show the effects of fixed-line telephones, mobile cellular, and the internet on growth, conditional on FDI levels. The plots on the right are the corresponding regression lines at three different levels of FDI.

Robustness checks

We conducted several robustness checks but restrict our discussions to the notable results and abstain from reporting all the detailed estimates due to space limitations. For example, we estimated the baseline equation with the dependent variable averaged over 5 years using a longer sampling period, 1970–2010.Footnote 15 The increasing marginal effects of initial ICTs (fixed-line telephone and sum of fixed-line and mobile cellular) on productivity growth were robust but larger in magnitude than for the 3-year periods.

Next, under the assumption that improved infrastructure development boosts ICTs penetration, thereby enhancing the network effects, we controlled for the effects of infrastructure development. The results for fixed-line telephone (Table 6, column 1) and fixed-line plus mobile cellular telephone (Table 6, column 5) confirm our earlier argument that the fixed-line telephone acts as a proxy for a broad array of infrastructure development in these countries. For example, when the infrastructure development proxy is included in the model, the increasing marginal effects of ICTs are present but only the linear term is significant.Footnote 16 Additionally, the negative effects are lower in both cases by 7.3% and 18.3% for fixed-line and the sum of fixed-line and mobile cellular, respectively.Footnote 17 Moreover, increasing infrastructure development in these countries by 10% boosts productivity growth by roughly 0.3%–0.5% annually in a 3-year period.

Further, we interacted the ICTs variables with the governance proxy. As previously stated, good governance, associated with democratic leaning governments, is assumed to promote a regulatory framework that enhances competition, which is critical to the growth of ICTs market. As a result, we expect the ICTs effects conditional on governance to have significant marginal impact on growth with larger magnitudes in association with increasing democracy. Our findings show significant effects only in two of the four specifications. The first case with significant effects albeit at the 10% level is the interaction with the linear term of fixed-line plus mobile cellular variable (Table 6, column 6). The second case occurs in the model that includes the mobile cellular as the only ICTs measure (Table 7, column 2), which provides evidence of weak significant network effects at the 10% level for the linear term and 5% for the quadratic term. These results suggest that contrary to expectations, good governance has minimal impact on ICTs proliferation and mainly on the mobile cellular technology.

Existing research has shown that differences in legal origin are relevant for growth (Assane and Malamud, 2010; Beck et al., 2003) but their impact has not been explored in the context of ICTs.Footnote 18 La Porta et al. (2008, 1997, 1998) argue that a country’s legal origin can be a good predictor of the nature and efficiency of its institutions and policy formulation environment, which can have real consequences on the rate of adoption and diffusion of ICTs. French civil law, relative to the English common law tradition, for example, is associated with less-efficient contract enforcement, the heavy hand of government ownership and regulation, and possibly higher corruption. As a result, we evaluate whether the effectiveness of ICTs on productivity growth differ based on a country’s legal origin by introducing the British (dBritish) and French (dFrench) legal origin dummies in the baseline model as standalone arguments and by interacting them with ICTs variables. We expect the impact of ICTs to be larger in countries with British legal origin relative to those with French legal origin. Also, we expect the British dummy to have positive effects on growth. Results for fixed-line telephone (columns 3–4) and the sum of fixed-line and mobile cellular (columns 7–8) are reported in Table 6, while those for mobile cellular (columns 3–4) and internet (columns 7–8) are reported in Table 7.

Contrary to the expectations, both dummy variables, where significant, have a negative impact on growth, with the British dummy exhibiting a larger magnitude relative to the French dummy (Table 6, column 3 and Table 7, column 7). The marginal impact of ICTs conditional on legal origin provides somewhat a compelling picture, especially for the internet variable. First, the interaction terms of the dummies with fixed-line telephone (Table 6, column 4), fixed-line plus mobile cellular (Table 6, column 8), and mobile cellular (Table 7, column 4) have robust increasing marginal effects, with the level of significance and magnitude of the coefficients largely consistent with the results of the baseline regressions. Second, when these dummy variables are interacted with the internet users variable, significant effects are evident only in the case of the British interaction, albeit at 10% level of significance. Specifically, internet effects conditional on British legal origin exhibit robust increasing marginal effects on growth of SSA countries. These findings imply that legal origin matters when it comes to the impact of internet proliferation on growth in these countries, possibly in terms of the government investing in supportive infrastructure, enacting universal access policies and providing a competition-oriented regulatory environment.

We also explored other models in which we introduced different specifications of the mobile cellular and internet variables. First, we evaluated the mobile cellular effects on productivity growth without controlling for the impact of the internet users in the same model and vice versa. Given the high correlation coefficient (0.90) between the two variables, separating them enables us to minimize the potential multicollinearity bias that might be present in the baseline results reported in Table 5. Results from these new specifications (documented in Table 7, columns 1 and 5 for mobile cellular and internet users, respectively) do not differ, in terms of significance, from those in Table 5 (column 1). Specifically, we find evidence of significant network effects from the mobile telephony and neutral effects in the case of internet users. The only major difference is the level of significance for the mobile telephony coefficient, which increases from 5% to 1% when the internet variable is excluded from the regressions. These findings suggest a very minimal impact of the multicollinearity bias in the baseline results. After all, it is well known that this bias does not reduce the predictive power or reliability of the model as a whole.

Second, we specify the two variables as an interaction term and as a sum. These specifications are based on the assumption that the proliferation of advanced internet-enabled mobile telephony (first to third generation connections) in these countries enables the mobile cellular technology to offer more advanced mobile services above and beyond the traditional services of basic voice and text. Furthermore, the availability of communication media over the internet such as Skype, Google talk, and other chat room platforms provides an alternative to the mobile telephony especially for long-distance communications.

The results for the interaction (column 9) and the sum of mobile cellular and internet users (column 10) specifications reported in Table 7 provide evidence in support of significant network effects similar to those observed in other ICTs specifications. The effects of the interaction term are weak at best, with 10% and 5% levels of significance for the linear and quadratic specifications, respectively. On the other hand, the coefficients of the sum of the mobile cellular and internet users show significant effects at the 1% level. In terms of the magnitude of impact, a 10 percentage-point increase in the number of mobile plus internet users lowers productivity growth by 3.6% annually in a 3-year period. Doubling that number boosts productivity growth by 0.04% within the same period.

Fixed effects results

For additional robustness checks, we report results based on the fixed effects (FE) estimation technique. FE estimation captures country-specific factors influencing labor productivity growth not otherwise captured by the independent variables. One assumption of the FE model is that the time-variant characteristics are unique to each country and that they are not correlated with another country’s characteristics. This assumption holds if the countries’ error terms are not correlated. However, if the error terms are correlated, the assumption does not hold and the FE model cannot be used. Consequently, we conduct the Hausman specification test for selected models in Tables 4 and 5 in order to determine whether to use random or fixed effects. The test rejects the null hypothesis that the difference in random and fixed effects coefficients is not systematic in all the regressions. As a result, we report in Tables 8 and 9 estimates based on FE.

Results reported in Table 8 are based on models in Table 4 and the 1975–2010 sampling period. Those in Table 9 are estimated using the shorter sampling period, 1995–2010, with estimation equations corresponding to selected models in Tables 5 and 7. In the presence of endogeneity bias, we expect FE estimates of the endogenous variables to be biased upwards/overstated.

As expected, the signs on most of the coefficients in all the specifications in Tables 8 and 9 are similar to those in the baseline regressions reported in Tables 4 and 5. With reference to the ICTs variables, only the coefficients for the sum of fixed-line and mobile cellular are robust, exhibiting increasing returns (Table 8, columns 3 and 4), similar to those tabulated in columns 3 and 4 of Table 4. The magnitude in this case however is larger, consistent with the presence of endogeneity bias. It is also worth noting that the results in Table 8 for openness, financial development, FDI, and investment are similar to those in the baseline regressions in Table 4.

Moreover, the sign and robustness of the coefficients for the control variables (government consumption spending, FDI) and the ICTs measures (mobile cellular and internet) in Table 9 are largely consistent with those of the baseline models in Table 5 (column 1) and Table 7 (columns 1 and 5). Overall, these findings signify that our estimates are robust even when different estimation techniques are used.

CONCLUSION

Over the past two decades, the economies of SSA have experienced robust growth, which has coincided with the rapid spread of wireless communication technology. This suggests that the penetration of ICTs might have contributed to the strong economic performance in this region. This study explores the nexus between growth and ICTs by analyzing the contributions of fixed-line telephony, mobile cellular subscriptions, and internet usage on changes in labor productivity in SSA. In addition, we investigate potential channels for the transmission of the growth-enhancing effects of ICTs and test for the presence of nonlinearities in the model using parametric and nonparametric methods.

Our findings show that fixed-line telephones and mobile cellular technology have a positive and significant impact on labor productivity growth, but only after penetration rates reach a certain critical mass. In particular, an increase in the access to fixed-line and mobile communication technologies by 10 percentage points decreases annual productivity growth by between 3% and 4% over the subsequent 3 years. However, doubling that rate boosts annual growth by 0.12%–0.15% for fixed-line telephony and by 0.05% for mobile cellular. The presence of these network effects also explains why internet usage, which is still at relatively low levels in SSA, does not exhibit a significant effect on growth.

Using nonparametric regression, we identify the thresholds of the network effects for various ICTs indicators. For mobile cellular, the critical mass is reached at levels above 20 subscriptions per 100 people, while the penetration rates required to achieve increasing returns for the combined fixed-line and mobile cellular indicator are around 30%. For the internet, 5 users per 100 seem sufficient to trigger the network effect, but this is still more than twice the current average in SSA. Our analysis further shows that FDI and openness not only improve productivity but help ICTs boost growth.

Furthermore, the results suggest that financial development is a potential channel for the transmission of the positive effect of ICTs on growth. This concurs with evidence of the explosive spread of mobile platforms for financial services in SSA in recent years. In addition, we also show that institutional factors, such as legal origins, might play an important supporting role for ICTs to promote productivity change. For example, we found that internet effects conditional on British legal origin exhibited robust increasing effects on growth in SSA countries. This suggests that countries associated with the common law tradition relative to the civil law system are proactive in terms of their governments investing in supportive infrastructure, enacting universal access policies and providing a competitive-oriented regulatory environment.

From a policy perspective, our findings indicate that if SSA countries want to sustain their growth performance in the future, they would need to continue investing in mobile communication technology and its applications in the financial sector. Increasing the penetration rates triggers network effects, which in turn boost productivity. In this regard, there is still untapped potential, especially in the case of internet usage. Lastly, governments in SSA should continue their efforts to attract FDI, open their economies, invest in supportive infrastructure, enact universal access policies, provide competition-oriented regulatory environment, and improve their institutional environment in order to benefit from the ICTs revolution.

Notes

See Dedrick et al. (2013) and Papaioannou and Dimelis (2007) for an extensive review of the related literature.

Network effects exist if consumers’ utility of using a given product or service increases with the number of other users. These effects, especially in the telecommunication industry, not only increase the sharing of data as the network expands (direct network effects), but also enable the use of complementary services (indirect network effects) such as mobile internet applications (eg, e-banking, e-health, and other related mobile telephony platform applications). The economic growth effects arise from these direct and indirect effects. However, in general, the network effects impact growth through their influence on technology adoption and diffusion. Nonetheless, the bandwagon effect, which results from the network expansion, is expected to drive output growth (Economides and Himmelberg, 1995; Rohlfs, 2001; Shapiro and Varian, 1999). Other studies have shown that the presence of network effects can have a chilling effect on growth for a number of reasons. For example, if the required network threshold is not achieved, it can hamper technology adoption, growth of complementary services, and new innovations (Birke, 2009; Farrell and Klemperer, 2007; Shy, 2001; Stremersch et al., 2007).

Specifically:

The average annual growth rate of output per worker between the years t−τ and t is calculated as (y it −yit−τ)/τ.

The standard approach in growth literature is to average the data over 3–5 years. However, due to data limitations of most ICTs variables, this study restricts itself to a 3-year average to maximize the data points.

The only exception is the human capital measure, which is averaged over the 3-year period.

The role of human capital constraints has featured prominently in the debate on SSA countries’ inability to replicate East Asia’s growth miracle (Pack and Paxson, 1999; Wolf, 2007).

While the success stories from the export-led growth of East Asian economies lend some support to the beneficial effects of trade openness (Dollar, 1992), most SSA countries are net importers. Unlike East Asian countries, their export sectors are characterized by primary commodity production and agriculture-based manufacturing, with potentially neutral or detrimental effects on productivity growth.

In more general terms, inflation can be interpreted as a measure of macroeconomic stability, while government consumption stands for the importance of government spending/investment in the economy.

Several studies have attempted to establish the direction of causality between growth and ICTs. A number of them (Dutta, 2001; Perkins et al., 2005; Wolde-Rufael, 2007) have arrived at the conclusion of bi-directional causality for both developed and developing countries. Nonetheless, other studies have also established a one-way causality, from growth to telecommunications investment (Beil et al., 2005 for US).

GMM estimation technique has been employed in related studies such as Papaioannou and Dimelis (2007) to control for the endogeneity bias. However Papaioannou and Dimelis (2007) use difference rather than system GMM.

Andrianaivo and Kpodar (2011) did not detect the presence of network effects in a sample of African countries, attributing it to their sampling period. They argued that network effects could not be detected because African countries had not yet reached the necessary threshold by 2007, which marks the final year of their sampling period.

A study by Gebreab (2002) found that the number of mobile subscribers increases by approximately 57% with each additional service provider.

Using data from 63 developing countries over the period 1990–2001, Sridhar and Sridhar (2007) showed that mobile telephones had a bigger impact on output than fixed-line telecommunication, which contrasts with our results. However, their estimates are likely to be biased because they failed to include a quadratic specification in their model.

The neutral effects from human capital can be attributed to the proxy used, primary schooling, which captures low-skill effects on labor productivity, rather than a general impact of human capital. For example, it has been established that tertiary education rather than average years of schooling is important for internet diffusion in developing countries (Kiiski and Pohjola, 2002). Unfortunately, in this study, we did not have sufficient data on tertiary education for most countries in the sample. Thus, these results should be interpreted bearing the proxy used in mind.

Results based on this sampling period are not reported but are readily available from the authors upon request.

We used different proxies of infrastructure development for which meaningful data was available – water, sanitation, and roads – and the results were consistently similar. However, the reported results use sanitation (improved sanitation facilities as a percentage of the population with access) as a proxy of infrastructure development due to data availability for this variable compared to the other two variables. The water variable is defined as improved water sources as a percentage of the population with access. Roads is defined as the percentage of paved roads in the country. The data on all three variables were downloaded from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators online database.

On the contrary, the mobile cellular and internet effects remain unchanged relative to the baseline regressions. Results for the mobile and internet variables are not reported but are available from the authors upon request. Generally the internet effects remained neutral while the mobile cellular coefficient maintained robust increasing return effects at 5% level of significance.

In this paper we adopt a broader definition of ‘legal origin’, similar to La Porta et al. (2008), as a style of social control of economic life. This definition encompasses assimilation of legal systems, social institutions, and infrastructure introduced in the African countries through conquest and colonization.

References

Acemoglu, D, Johnson, S and Robinson, J . 2005: The rise of Europe: Atlantic trade, institutional change and economic growth. American Economic Review 95 (3): 546–579.

Andrianaivo, M and Kpodar, K . 2011: ICTs, financial inclusion, and growth: Evidence from African countries. IMF Working Papers 11/73, International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC.

Arellano, M and Bover, O . 1995: Another look at the instrumental variables estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics 68 (1): 29–51.

Assane, D and Malamud, B . 2010: Financial development and growth in sub-Saharan Africa: Does legal origin matter? Applied Economics 42 (21): 2683–2697.

Barro, R . 1991: Economic growth in a cross section of countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics 106 (2): 407–433.

Barro, RJ and Sala-i-Martin, X . 1995: Economic growth. McGraw-Hill: New York.

Beck, T, Demirgüç-Kunt, A and Levine, R . 2003: Law and finance: Why does legal origin matter? Journal of Comparative Economics 31 (4): 653–675.

Beck, T, Levine, R and Loayza, N . 2000: Finance and the sources of growth. Journal of Financial Economics 58 (1–2): 261–300.

Beil, R, Ford, G and Jackson, J . 2005: On the relationship between telecommunications investment and economic growth in the United States. International Economic Journal 19 (1): 3–9.

Birke, D . 2009: The economics of networks: A survey of the empirical literature. Journal of Economics Surveys 23 (4): 762–793.

Blundell, R and Bond, S . 1998: Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87 (1): 115–143.

Chéneau-Loquay, A . 2008: The role played by the informal economy in the appropriation of ICTs in urban environments in West Africa. Network and Communication Studies 22 (1–2): 109–126.

Clarke, GRG and Wallsten, SJ . 2006: Has the internet increased trade? Developed and developing country evidence. Economic Inquiry 44 (3): 465–484.

Dedrick, J, Kraemer, K and Shih, E . 2013: Information technology and productivity in developed and developing countries. Journal of Management Information Systems 30 (1): 97–122.

Dewan, S and Kraemer, K . 2000: Information technology and productivity: Evidence from country-level-data. Management Science 46 (4): 548–562.

Dollar, D . 1992: Outward-oriented developing economies really do grow more rapidly: Evidence from 95 LDCs, 1976–1985. Economic Development and Cultural Change 40 (3): 523–544.

Dollar, D and Kraay, A . 2004: Trade, growth, and poverty. Economic Journal 114 (493): F22–49.

Dutta, A . 2001: Telecommunications and economic activity: An analysis of granger causality. Journal of Management Information System 17 (4): 71–95.

Economides, N and Himmelberg, CP. 1995: Critical Mass and Network Size with Application to the US FAX Market, (August). NYU Stern School of Business EC-95-11, http://ssrn.com/abstract=6858, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.6858, accessed 6 June 2013.

Farrell, J and Klemperer, P . 2007: Coordination and lock-in: Competition with switching costs and network effects. In: Armstrong, M and Porter, R (eds). Handbook of Industrial Organization. Vol. 3, Ch. 31. North Holland: Amsterdam.

Fischer, S . 1993: The role of macroeconomic factors in growth. Journal of Monetary Economics 32 (3): 485–512.

Gebreab, FA . 2002: Getting connected: Competition and diffusion in African mobile telecommunications markets. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2863, World Bank: Washington, DC.

Grace, J, Kenny, C and Qiang, C . 2003: Information and communication technologies and broad based development: A partial review of the evidence. World Bank Working Paper, Technical Report 12, World Bank: Washington, DC.

Grossman, G and Helpman, E . 1991: Innovation and growth in the global economy. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

Gruber, H and Koutroumpis, P . 2011: Mobile telecommunications and the impact on economic development. Economic Policy 26 (67): 387–426.

GSMA. 2008: Taxation and the growth of mobile services in sub-Saharan Africa. Frontier Economics, http://www.gsma.com/publicpolicy/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/taxgrowthsubsaharanafrica.pdf, accessed 22 February 2014.

Gyimah-Brempong, K and Karikari, J . 2010: Telephone demand and economic growth in Africa. In: Seck, D and Boko, S (eds). Back on Track: Sector-Led Growth in Africa and Implications for Development. Africa World Press: Trenton, NJ, pp. 265–289.

Hawash, R and Lang, G . 2010: The impact of information technology on productivity in developing countries. Faculty of Management Technology Working paper no. 19, German University of Cairo: Cairo, Egypt.

Heston, A, Summers, R and Aten, B . 2012: Penn world table version 7.1. Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices, University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia.

Im, KS, Pesaran, MH and Shin, Y . 1997: Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Mimeo, Department of Applied Economics, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK.

International Telecommunication Union (ITU). 2012: Measuring the Information Society, http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/publications/mis2012/MIS2012_without_Annex_4.pdf, accessed 16 September 2013.

Jack, W and Suri, T . 2011: Mobile money: The economics of M-PESA. NBER Working paper no. 16721, National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA.

Jimenez-Rodriguez, R . 2012: Evaluating the effects of investment in information and communication technology. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 21 (2): 203–221.

Jorgenson, D . 2003: Information technology and the G7 economies. World Economics 4 (4): 139–169.

Kathuria, R, Uppal, M and Mamta . 2009: An econometric analysis of the impact of mobile phones. The Vodafone Policy Paper Series (9), pp. 5–20.

Ketteni, E, Mamuneas, T and Stengos, T . 2006: The effect of information technology and human capital on economic growth. Rimini Centre for Economic Analysis Working Paper 03–07, Rimini Centre for Economic Analysis: Rimini, Italy.

Kiiski, S and Pohjola, M . 2002: Cross-country diffusion of the internet. Information Economics and Policy 14 (2): 297–310.

Kimenyi, M and Moyo, N . 2011: Leapfrogging development through technology adoption. In: Foresight Africa: The Continent’s Greatest Challenges and Opportunities for 2011. Brookings Institution: Washington, DC.

King, R and Levine, R . 1993: Finance, entrepreneurship, and growth: Theory and evidence. Journal of Monetary Economics 32 (3): 513–542.

La Porta, R, Lopez-de-Silanes, F and Shleifer, A . 2008: The economic consequences of legal origins. Journal of Economic Literature 46 (2): 285–332.

La Porta, R, Lopez-de-Silanes, F, Shleifer, A and Vishny, R . 1997: Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Finance 52 (3): 1131–1150.

La Porta, R, Lopez-de-Silanes, F, Shleifer, A and Vishny, R . 1998: Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy 106 (6): 1113–1155.

Lee, S, Levendis, J and Gutierrez, L . 2012: Telecommunications and economic growth: An empirical analysis of sub-Saharan Africa. Applied Economics 44 (4): 461–469.

Levine, R and Renelt, D . 1992: A sensitivity analysis of cross-country growth regressions. American Economic Review 82 (4): 942–963.

Marshall, M and Jaggers, K . 2011: Polity IV project: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2010. Center for International Development and Conflict Management, University of Maryland: College Park, MD.

Oliner, S and Sichel, D . 2000: The resurgence of growth in the late 1990s: Is the information technology the story? The Journal of Economic Perspectives 14 (4): 3–22.

Oulton, N . 2002: ICTs and productivity growth in the UK. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 18 (3): 363–379.

Pack, H and Paxson, C . 1999: Is African manufacturing skill-constrained? Policy Research Working paper no. 2212, World Bank: Washington, DC.

Papaioannou, S and Dimelis, S . 2007: Information technology as a factor of economic development: Evidence from developed and developing countries. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 16 (3): 179–194.

Perkins, P, Fedderke, J and Luiz, J . 2005: An analysis of economic infrastructure investment in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics 73 (2): 211–228.

Rodrik, D, Subramanian, A and Trebbi, F . 2004: Institutions rule: The primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. Journal of Economic Growth 9 (2): 131–165.

Rohlfs, J . 2001: Bandwagon effects in high-technology industries. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

Roller, L and Waverman, L . 2001: Telecommunications infrastructure and economic development: A simultaneous equations approach. American Economic Review 91 (4): 909–923.

Roodman, D . 2006: How to do xtbaond2: An introduction to ‘difference’ and ‘system’ GMM in stata. Center for Global Development Working Paper 103, Center for Global Development Working: Washington, DC.

Sala-i-Martin, X, Doppelhofer, G and Miller, R . 2004: Determinants of long-term growth: A Bayesian averaging of classical estimates (BACE) approach. American Economic Review 94 (4): 813–835.

Shapiro, C and Varian, H . 1999: Information rules. HBS Press: Cambridge, MA.

Shy, O . 2001: The economics of network industries. Cambridge University Press: New York.

Sridhar, K and Sridhar, V . 2007: Telecommunications infrastructure and economic growth: Evidence from developing countries. Applied Econometrics and International Development 7 (2): 37–61.

Stremersch, S, Tellis, G, Franses, P and Binken, J . 2007: Indirect network effects in new product growth. Journal of Marketing 71 (3): 52–74.

Vu, K . 2011: ICTs as a source of economic growth in the information age: Empirical evidence from the 1996–2005 period. Telecommunications Policy 35 (4): 357–372.

Wamboye, E and Tochkov, K . 2014: External debt, labour productivity growth and convergence: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. The World Economy 37 (3): 1–22.

Waverman, L, Meschi, M and Fuss, M . 2005: The impact of telecoms on economic growth in developing countries. In: Africa: The Impact of Mobile Phones. Vodafone Policy Paper 3. Vodafone: London, UK, pp. 10–23.

Wolde-Rufael, Y . 2007: Another look at the relationship between telecommunications investment and economic activity in the United States. International Economic Journal 21 (2): 199–205.

Wolf, S . 2007: Encouraging innovation for productivity growth in Africa. Africa Trade Policy Centre Work in Progress no. 54, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Wooldridge, JM . 2010: Econometric analysis of cross-section and panel data, 2nd Edn. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

World Economic Forum (WEF). 2013: The Africa competitiveness report. The World Bank: Washington, DC.

Yonazi, E, Kelly, T, Halewood, N and Blackman, C . 2012: The transformational use of information and communication technologies in Africa. The World Bank and African Development Bank: Washington, DC.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Editor, Josef Brada, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wamboye, E., Tochkov, K. & Sergi, B. Technology Adoption and Growth in sub-Saharan African Countries. Comp Econ Stud 57, 136–167 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2014.38

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2014.38

Keywords

- economic growth

- information and communication technologies

- labor productivity growth

- sub-Saharan Africa

- nonparametric analysis

- network effects