Abstract

Ever since man engaged in recording and transmitting his thoughts and ideas in forms of cuneiform (ancient Mesopotamian script), hieroglyphs, or codex, the notion of information has been a significant factor in the development of his civilization and his cognitive faculty. Today, however, we have arrived at the point where not only the world we live in but the entire universe is seen in light of information to the extent that it’s sometimes hard to fathom, as Brown and Duguid observed: ‘it’s sometimes hard to fathom what there is beyond information to talk about’1. Physicists seem to suggest that everything we know of, from cats and dogs and trees and people, to stars, planets and galaxies are all just pieces of information, bits of code. Biologists exhibit the blueprint of life by transcribing genetic information from DNA to RNA and then interpreting (translating) information carried by RNA to synthesize the encoded protein. In fact the role of information theory in science stretches into Gödel’s Incompleteness proof, the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, thermodynamic entropy, memetics, bio-informatics, and the nature of information as an ontological entity distinct from matter or energy.2

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Preview

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes and References

John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid, The Social Life of Information, Harvard Business School Press, 2000, p. 15.

See James Gleick, The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood, 2011, Pantheon Books.

For instance, informational asymmetries occur in a great many contexts such as a bank does not have complete information about lenders’ future income; an insurance company cannot fully observe policyholders’ responsibility for insured property and external events which affect the risk of damage; an auctioneer does not have complete information about the willingness to pay of potential buyers; the government has to devise an income tax system without much knowledge about the productivity of individual citizens; etc.

Albert Borgmann, Holding On to Reality: The Nature of Information at the Turn of the Millennium, University of Chicago Press, 1999, pp. 218–19.

T. Roszak, The Cult of Information: The Folklore of Computers and the True Art of Thinking, Pantheon, 1986, p. 19.

Ibid., p. x.

Norbert Wiener, The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society, Da Capo Press, 1988, p. 95.

Ibid., p. 16.

Daniel Bell, ‘The Social Framework of the Information Society’, in T. Forester (ed.), The Microelectronics Revolution: The Complete Guide to the New Technology and its Impact on Society, MIT Press, 1980, p. 506.

See Michael H. Harris, Pamela C. Harris and Stan A. Hannah, Into the Future: The Foundations of Library and Information Services in the Post-Industrial Era, 2nd edition, Amazon already ordered, p. 4.

Cliffs. Notes.com. ‘The Structure of the Mass Media and Government Regulation’, 16 Sep 2012 at: http://www.cliffsnotes.com/study_guide/topicArticleId-65383,articleId-65497.html. Also see ‘Mind Control Theories and Techniques used by Mass Media’ at: http://lightoftruth.tumblr.com/post/24045001341/mind-control-theories-and-techniques-used-by-mass-media.

Chapter 4: What Information Society? by Frank Webster, p. 51 in “The Information Age: An Anthology on Its Impact and Consequences”. Edited by David S. Alberts and Daniel S. Papp. CCRP Publication Series. 1997.

Frank Webster, “Theories of the Information Society”, Routledge, 2007, p. 14.

Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes, Penguin, 1976, p. 163.

John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid, The Social Life of Information, Harvard Business School Press, 2000, p. xvi.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Indeed, in his book Information Anxiety (1989, Doubleday), Richard Wurman claimed that the weekday edition of The New York Times contains more information than the average person in seventeenth-century England was likely to come across in a lifetime.

John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid, The Social Life of Information, Harvard Business School Press, 2000, p. xiii.

The literature on this topic is not only immense but also diverse. For instance see the classic work by Howard Rheingold, The Virtual Community, Reading, Addison-Wesley, 1993. The reader is particularly referred to Chapter Ten, ‘Disinformocracy’. The electronic version of the book is available at: http://www.rheingold.com/vc/book/intro.html. Also see a book edited by Robin Mansell and Roger Silverstone called, Communication by Design: The Politics of Information and Communication Technologies, published in 1996 by Oxford University Press. I also suggest an article by Lawrence M. Krauss, called ‘War Is peace: Can Science Fight Media Disinformation?’, in Scientific American, November 20, 2009 (available at: http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=war-is-peace).

Ron Suskind, ‘Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush’, The New York Times Magazine, 2004. pp. 10–17.

See Brandon Smith, ‘Disinformation: How it Works, Personal Liberty Digest’, August 7, 2012 (available at: http://personalliberty.com/2012/08/07/disinformation-how-it-works/). I would also like to remind the reader of the English novelist George Orwell, who was remarkably prescient about many things, and one of the most disturbing aspects of his masterpiece 1984 involved the blatant perversion of objective reality, using constant repetition of propaganda by a militaristic government in control of all the media.

Ben H. Bagdikian, Media Monopoly, Beacon Press, 1992, p. 5.

American author and feminist Bell Hooks refers to cultural commodification as ‘eating the other’. By this she means that cultural expressions, revolutionary or postmodern, can be sold to the dominant culture (see bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation, South End Press, 1992). Any messages of social change are not marketed for their messages but used as a mechanism to acquire a piece of the ‘primitive’.

Henry Jenkins and David Thorburn, Democracy and New Media, MIT Press, 2004, p. 40.

Erik Brynjolfsson and Lorin Hitt, “Paradox Lost? Firm-Level Evidence on the Returns to Information Systems Spending,” Management Science, INFORMS, 1996, vol. 42, no. 4: 541–58.

Eitel J. M. Lauría and Salvatore Belardo, ‘Information or Informing: Does it Matter?’, in Ralph Berndt (ed.), Weltwirtschaft 2010: Trends and Strategien, Springer, 2009, p. 213.

Tefko Saracevic, ‘Information Science’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 1999, vol. 50, no. 12, p. 1054.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/wittgenstein/#Mea.

Wittgenstein elaborated on this case and observed, ‘Consider, for example, the activities that we call “games”. I mean board-games, card-games, ballgames, athletic games, and so on. What is common to them all? — Don’t say: “they must have something in common, or they would not be called ‘games’ — but look and see whether there is anything common to all. — For if you look at them, you won’t see something that is common to all, but similarities, affinities, and a whole series of them at that. To repeat: don’t think, but look! — Look, for example, at board-games, with their various affinities. Now pass to card-games; here you find many correspondences with the first group, but many common features drop out, and others appear. When we pass next to ball-games, much that is common is retained, but much is lost. — Are they all entertaining? Compare chess with noughts and crosses. Or is there always winning and losing, or competition between players? Think of patience. In ball-games, there is winning and losing; but when a child throws his ball at the wall and catches it again, this feature has disappeared. Look at the parts played by skill and luck, and at the difference between skill in chess and skill in tennis. Think now of singing and dancing games; here we have the element of entertainment, but how many other characteristic features have disappeared. And we can go through the many, many other groups of games in the same way, can see how similarities crop up and disappear.’ (See Ludwig Wittgenstein and P. M. S. Hacker; Joachim Schulte (ed.), Philosophical Investigations, Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, pp. 64 (66)).

Ludwig Wittgenstein, The Blue and Brown Book, Harper Torchbook, First edition, 1965, p. 5.

From a purely philosophical point of view the following argument can be put forward: by using language and terms to accomplish something implies that our conducts are some sort of encountering with the world, an action if you would, or in a Heideggerian sense, we are acting (being)-in-the-world. As a verb, as Heidegger indicates (see Martin Heidegger, Being And Time, Harper and Row Publishers, revised edition, translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson, 1962, see specially pp. 24–5), being-in is the disclosure of an already in place action since it points to movement, a change, a deed, a result, an action. (A verb can describe an action, e.g., run, the occurrence of an event, e.g., running, a state, e.g., having something, or a change, e.g., grow. A verb also means an action that is occurring, or the result of an action that has happened. In this sense, the verb to be means to exist, to live, to occur, to happen, etc.) Therefore action, as defined, is the key factor for being-in-the-world.

Indeed, there is a wealth of literature on how information is formed for specific purposes to persuade given persons. For instance see Brooke Noel Moore and Richard Parker, Critical Thinking, 9th edition, McGraw-Hill, 2012.

The term ‘persuasive definition’ was introduced by philosopher C.L. Stevenson as part of his emotive theory of meaning.

Henryk Skolimowski, ‘Freedom, Responsibility and The Information Society: The time of philosopher-kings is coming’, Delivered at the Educating the Information Society series, Eastern Michigan University, March 28, 1984, p. 493.

Alvin M. Schrader, Toward a theory of library and information science, Volume 1, Indianan University Press, 1983, pp. 99. On the similar subject, the interested reader is also refer to: Andrew Pope, ‘Bradford’s Law and the Periodical Literature of Information Science’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science, July/August 1975 , vol. 26, issue 4, pp. 207–13.

Henning Spang-Hanssen, ‘How to teach about information as related to documentation’, Human IT, 2001, 5(1), 125–43. (Original work published in 1970) Retrieved July 2012 at: http://etjanst.hb.se/bhs/ith/1-01/hsh.htm.

R. L. Ackoff, ‘From data to wisdom: Presidential address to ISGSR’, Journal of Applied Systems Analysis, June 1988, vol. 16, pp. 3–9. It should be noted that the ISGSR has changed to the ‘International Society for the System Sciences’.

However, Shedroff presents the model as overlapping circles but it also presents a similar learning or understanding process (see N. Shedroff, ‘An overview of understanding’, in R. S. Wurman (ed.), Information Anxiety 2, Que, 2nd edition, 2000, pp. 27–9.

R. L. Ackoff, 1988, p. 3.

F. Machlup, ‘Semantic quirks in studies of information’, in F. Machlup and U. Mansfield (eds), The Study of Information: Interdisciplinary Messages, John Wiley & Sons, 1983, p. 647.

L. Ma, 2012, ‘Meanings of Information: The Assumptions and Research Consequences of Three Foundational LIS Theories’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, vol. 63, no. 4, p. 721.

R. L. Ackoff, 1988, p. 3.

C. Zins, ‘Conceptual approaches for defining data, information, and knowledge’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 2007, vol. 58, no. 4, p. 479.

Thomas H. Davenport and Laurence Prusak, Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know, Harvard Business Review Press, 1st edition, 1998, p. 2.

Ibid., p. 3.

Ibid.

R. L. Ackoff, 1988, p. 3.

Information as thing merely implies that ‘information is additive and does not create a qualitative difference in the way the person receiving the information thinks’. However, information as process ‘states that information modifies the knowledge structure of the person receiving the information’. (see Amanda Spink and Charles Cole, ‘Information behavior: A Socio-Cognitive Ability, Evolutionary Psychology Journal, 2007, vol. 5, no. 2. p. 260.

Eitel J. M. Lauria and Salvatore Belardo, ‘Information or Informing: Does it Matter?’, 2009, p. 218.

Jean Tague-Sutcliffe, Measuring Information: An Information Services Perspective, Academic Press, 1995, p. 13.

C. E. Shannon and W. Weaver, The Mathematical Theory of Communication, University of Illinois Press, 1949.

H. Simon, The Sciences of the Artificia, MIT Press, 1969.

R. Sternbergand, P. Frensch, Complex Problem Solving: Principles and Mechanisms. Lawrence Erlbaum, 1991.

D. Halpern, Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinkin, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1989.

N. Chomsky et al., Chomsky: Selected Readings, Oxford University Press, 1971.

N. Chomsky, Language and Thought, Moyer Bell, 1993.

D. Schon The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action, Basic Books, 1983.

H. Mintzberg, ‘Brief Case: Strategy and Intuition: A Conversation with Henry Mintzberg’, Long Range Planning, 2 (1991), pp. 108–10.

E. Carayannis,. ‘An Integrative Framework of Strategic Decision Making Paradigms and their Empirical Validity: The Case for Strategic or Active Incrementalism and the Import of Tacit Technological Learning’. Working Paper Series No. 131, RPI School of Management, October 1992.

E. Carayannis,,’ Incrementalisme strategique’, Le Progres Technique, Paris, 1993.

E. Carayannis, and J. Jennifer,’ A Multi-national, Resource-based View of Training and Development and the Strategic Management of Technological Learning: Keys for Social and Corporate Survival and Success’, 39th International Council of Small Business Annual World Conference, Strasbourg, France, 27–29 June 1994.

E. Carayannis, ‘The Strategic Management of Technological Learning from a Dynamically Adaptive, High-tech Marketing Perspective: Sustainable Competitive Advantage through Effective Supplier-Customer Interfacing’, University of Illinois at Chicago/American Management Association. Research Symposium on Marketing and Entrepreneurship, Paris 29–30 June 1994.

E. Carayannis, E., ‘Gestion strategique de l’acquisition de savoir-faire’, Le Progres Technique, Paris, 1994.

E. Carayannis,’ The Strategic Management of Technological Learning: Transnational Decision Making Frameworks and their Empirical Effectiveness’, PhD Dissertation, School of Management, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY, 1994.

M. Dodgson, The Management of Technological Learning, De Gruyter, 1991.

M. Dodgson, ‘Organizational Learning: A Review of Some Literatures’, Special Issue on Evolutionary Perspectives on Strategy, Organization Studies, 14 (3) (1993), pp. 375–94.

E. von Hippel The Sources of Innovation, Oxford University Press.

R. Garud and M.A. Rappa,’ A Socio-cognitive Model of Technology Evolution: The Case of Cochlear Implants’, Organization Science 5(3), 1994.

M. Polanyi Personal Knowledge, University of Chicago Press, 1958.

M. Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension, Routledge, 1966.

I. Nonaka, ‘Creating Organizational Order out of Chaos: Self-renewal in Japanese Firms’, California Management Review, Spring 1988.

I. Nonaka, ‘A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation’, Organization Science, February 1994.

E. Carayannis, ‘Re-engineering High Risk, High Complexity Industries through Multiple Level Technological Learning: A case Study of the World Nuclear Power Industry’, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 12 (1996), pp. 301–18.

E. Carayannis and R. y Stokes, ‘A Historical Analysis of Management of Technology at Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik (BASF) AG, 1865 to 1993: A Case Study’, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, vol. 14, 1997, pp. 175–93.

E. Carayannis, ‘The Strategic Management of Technological Learning in Project/Program Management: The Role of Extranets, Intranets and Intelligent Agents in Knowledge Generation, Diffusion, and Leveraging’. Technovation, 18 (11) (1998), pp. 697–703.

Chun Wei Choo, The Knowing Organization: How Organizations Use Information to Construct Meaning, Create Knowledge, and Make Decisions, Oxford University Press, 1998.

Erik Brynjolfsson and Lorin Hitt, ‘Paradox Lost? Firm-Level Evidence on the Returns to Information Systems Spending’, Management Science, INFORMS, 1996, vol. 42, no. 4, p. 541–58.

Chaos Theory is a close relative of Catastrophe Theory, but has shown more potential in both, explaining and predicting unstable non-linearities, thanks to the concepts of self-similarity or fractals [patterns within patterns] (B.B. Mandelbrot) The Fractal Geometry of Nature, W.H. Freeman and the chaotic behavior of attractors (ibid.), as well as the significance assigned to the role that initial conditions play as determinants of the future evolution of a non-linear system (J. Gleick, Chaos, Penguin, 1987).

Shannon, C. E., Collected Papers, edited by N. J. A. Sloane and A. D. Wyner, IEEE Press, 1993, p. 180. Emphasis is added.

A. J. Ayer, ‘What is Communication?’, in Studies in Communication: Contributed to the Communication Research Centre, by A. J. Ayer, Colin Cherry, B. Ifor Evans, D. B. Fry, J. B. S. Haldane, Randolph Quirk, Geoffrey Vickers, T. B. L. Webster, R. Wittkower and J. Z. Young, London, Martin Secker & Wariburg, 1955, pp. 11–12. The book is available at http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=79561036.

Luciano Floridi, ‘Open Problems in the Philosophy of Information’, MetaPhilosophy, vol. 35, no. 4, July 2004, p. 563. Moreover, the reader should note that the term ‘Family resemblance’ as a feature of Wittgenstein’s philosophy owes much to its translation in English. Wittgenstein, who wrote mostly in German, used the compound word ‘Familienähnkichkeit’ but as he lectured and conversed in English he used ‘family likeness’ (e.g. The Blue Book, p. 17, 33; The Brown Book,§66). However in the Philosophical Investigations the separate word ‘ähnlichkeit’ has been translated as ‘similarity’ (§§11, 130, 185, 444) and on two occasions (§§9, 90) it is given as ‘like’ (see Wikipedia, under the heading ‘Wittgenstein family resemblance concept’).

Fernando Albano Maia de Magalhaes Ilharco, Information Technology as Ontology: A Phenomenological Investigation into Information Technology and Strategy In the World, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2002, p. 151. Accessed online at: http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/299/1/Ilharco_Information%20technology%20as%20ontology.pdf.

John R. Pierce, An Introduction to Information Theory: Symbols, Signals and Noise, New York: Dover Publications, 1980, p. 9.

Irvin John Good, The Scientist Speculates: An Anthology of Partly-baked Ideas, NY, Basic Books, 1963, p. 222.

Vincent Wen, ‘Are the truths of mathematics invented or discovered?’ at http://www.pdfio.com/k-1289294.html.

Vincent Wen, p. 2.

For instance see: Lana Ivanitskaya, PhD; Irene O’Boyle, PhD, CHES; Anne Marie Casey, ‘Health Information Literacy and Competencies of Information Age Students: Results From the Interactive Online Research Readiness Self-Assessment (RRSA)’, Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2006, vol. 8, no. 2; Henrik Serup Christensen and Åsa Bengtsson, ‘The political competence of internet participants’, Information Communication Society, 2011, vol. 14, issue 6, pp. 896–916.

For instance, see Ariel Rabkin, ‘Who Controls the Internet? The United States, for now, and a good thing, too’, The Weekly Standard, May 25, 2009, vol. 14, no. 34. It can be access at: http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/016/515zoozk.asp.

Of course, there are always winners and losers, however such outcomes neither occur by designed nor by random selection, but instead transpire by prevailing consequences.

Gibson would later describe cyberspace in No Maps for These Territories as an ‘evocative and essentially meaningless’ buzzword that could serve as a cipher for all of his cybernetic musings. As Thil further elaborates, ‘It did that and more, going supernova in his foundational, award-winning debut novel of 1984, Neuromancer. Gibson’s networked artificial environment anticipated the globally internetworked techno-culture (and its surveillance) in which we now find ourselves.’ (See Scott Thil (03.17.09). ‘March 17, 1948: William Gibson, Father of Cyberspace’, WIRED).

The same information-driven environment is characterized by a rapid evolution of data-driven decision-making toward the vastly more complex concept of computationally-intensive ‘big data analytics’ (S. Lavalle, E., Lesser, R., Shockley M.S. Hopkins., N. and Kruschwitz, ‘Big Data, Analytics and the Path from Insights to Value’, MIT Sloan Management Review (52:2) Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2011, pp. 21–32).

It should be noted however that we do not subscribe to the popular notion that the recent trends of change in governments, e.g., the Arab Spring, mainly occurred as a result of information technology. For one thing, information technology is a tool, and as such its effectiveness entails pre-existing conditions that it cannot furnish. A notion of regime change is different from change in government, which often occurs as a result of elections. More specifically, in our view, change in regime requires necessary and sufficient conditions, both of which cannot be facilitated by information technology.

http://futureculture.blogspot.com/2003_11_01_archive.html.

The reader should note that the main critique of etymology is an attack on a series of fallacious assumption about how names and things are related (See David Del Bello, Forgotten Paths: Etymology and the Allegorical Mindset, Catholic University of American Press, 2007, p. 59). According to Thiselton, these false assumptions include the following: ‘(1) that the word rather than the sentence or speech-act, constitutes the basic unit of meaning to be investigated; (2) that questions about etymology somehow relate to the real or “basic” meaning of a word; (3) that language has a relation to the world which is other than conventional, and that its “rules” may therefore be prescriptive rather than merely descriptive; (4) that logical and grammatical structure are basically similar or even isomorphic; (5) that meaning always turns on the relation between a word and the object to which it refers; (6) that the basic kind of language-use to be investigated (other than words themselves) is the declarative proposition or statement; and (7) that language is an externalization, sometimes a merely imitative and approximate exter-nalization, of inner concepts or ideas’(see Anthony C. Thiselton, ‘Semantics and New Testament Interpretation’, in New Testament Interpretation, edited by I. Howard Marshal, Exeter: Paternoster, 1977, p. 76). Michel Bréal underlined the importance of function over form, which is in part a synchronic and structural approach to semantics. In his critique of etymology, he stated, ‘Any one who takes his stand on etymology without paying attention to the Deterioration of meaning may be led into strange errors.’ (See Semantics: Studies in the Science of Meaning, Translated by Henry Cust, Published by William Heinemann, 1900, p. 103.) See also ‘The etymology fallacy’, The Economist Magazine, 2 August 2011 at: http://www.economist.com/blogs/johnson/2011/08/word-origins-and-meaning.)

Humberto R. Maturana and Francisco J. Varela, The Three of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding, Shambala, 1992, especially pp. 234–5.

Humberto R. Maturana and Francisco J. Varela, 1992, p. 26.

Fredrick A. Olafson, What is a Human Being? A Heideggerian View, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

J. L. Austin, Philosophical Papers. J.C. Urmson and G.J. Warnock (eds). Clarendon Press, 1961, pp. 149–50.

Hans Christian von Baeyer, Information: The New Language of Science, Harvard University Press, 2004, p. 20.

That is to say the task is to trace back the origins of the words identifying the phenomena, so that an analysis is not destined to bring back the meaning of the words per se, but rather to bring forth the meaning of things, ‘in the ante-predicative life of consciousness’.

Richard J. Boland, ‘The In-Formation of Information Systems’, in R. J. Boland and R. A. Hirschhiem. (eds), Critical Issues in Information System Research, John Wiley & Son, 1983, p. 363.

John D. Haynes, Perspective Thinking for Inquiring Organisations, Informing Science, 2000 pp. 98–101.

John D. Haynes, Perspective Thinking for Inquiring Organisations, Information Science Publisher, 2008, p. 99.

See Mary Garcia, Forms, University of Chicago, 2002, at: http://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/form.htm. ‘It should be noted that this latter definition of internal form between shapes leads to the notion of a form within a form, as the original interpretation of eidos is “shape”’.

Whatever traces of the great debates about the nature of form remain in our definition of information; they are indebted to both Plato and Aristotle.

The sound pattern is not actually a sound, but rather is the hearer’s psychological impression of a sound (something physical), as given to a person by the evidence of his/her senses.

See Wikipedia at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structuralism#cite_note-Blackburn-0.

See Daniel Chandler, Semiotics for Beginners, at http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/S4B/sem02.html.

His major limitation, which Saussure inherited, is related to the perception in which the world is viewed as an independently existing object, capable of precise objective observation and classification. In respect of linguistics, Hawkes observed, ‘this outlook yields a notion of language as an aggregate of separate units, called “words”, each of which somehow has a separate “meaning” attached to it, the whole existing within a diachronic or historical dimension which makes it subject to observable and recordable laws of change.’ See Terence Hawkes, Structuralism and Semiotics, Routledge, 2nd edition, 2003, p. 8. For a critical review of Saussure’s work see also; Noam Chomsky, Syntactic Structures, Walter de Gruyter, 2nd edition, 2002; and C.K. Ogden and I.A. Richards in The Meaning of Meaning, in which according to John Sturrok, Saussure is ‘dead and buried by page six’ (see http://www.lrb.co.uk/v06/n02/john-sturrock/where-structuralism-comes-from.).

According to Wikipedia, ‘In linguistics, a synchronic analysis is one that views linguistic phenomena only at one point in time, usually the present, though a synchronic analysis of a historical language form is also possible. This may be distinguished from diachronics, which regards a phenomenon in terms of developments through time. Diachronic analysis is the main concern of historical linguistics; most other branches of linguistics are concerned with some form of synchronic analysis.’ See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synchronic_analysis.

For instance, the structural relationship between the sound-image made by the word tree (i.e. the signifier) and the concept of a tree (i.e., the signified) thus constitutes a linguistic sign, and language in Saussure’s rational is made up of these.

Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics (Roy Harris, translated and annotated introduction), Open Court, 1st edition, 1983, p. 15.

Charles Sanders Peirce, Justus Buchler (ed.), Philosophical Writings of Peirce, Dover Publications, 2011, p. 115.

Susanne K. Langer, Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Symbolism of Reason, Rite and Art, NY, Mentor, 1951, pp. 60–1.

Susanne K. Langer, 1951, p. 60.

See Daniel Chandler, Semiotics for Beginners at: http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/S4B/sem02.html.

David A. Pharies, Charles Sanders Peirce and the Linguistic Sign, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1985, p. 15.

Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge, Penguin Books, 1966, p. 52.

Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, 1966, p. 56.

See http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/02/why-thousands-of-iranian-women-are-training-to-be-ninjas/252531/.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/blogpost/post/irans-ninja-army-is-made-up-of-3500-women/2012/02/06/gIQAUCsDuQ_blog.html.

http://nation.foxnews.com/iran/2012/02/06/does-irans-army-lady-ninjas-pose-security-threat.

http://www.cnn.com/video/#/video/world/2012/02/06/nr-iranian-women-ninja-warriors.cnn.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/shortcuts/2012/feb/19/irans-female-ninjas.

https://twitter.com/#!/lukekummer. Erik Wemple at The Washington Post also wrote on Kummer’s resignation, see http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/erik-wemple/post/the-dailys-relish-for-female-iranian-ninjas/2012/03/29/gIQA17ixiS_blog.html?wprss=rss_opinions.

It is also noteworthy that if one watches these videos it would be easy to realize that it is quite impossible to tell apart which part of the outfit is veil and which part is the ninja’s outfit. And this is key to my argument since the ninja’s outfit, in the context of Japanese culture, does not convey a symbol of oppression, but rather is perceived as a symbol of power.

In Saussure’s rationale the value of a sign depends on its relations with other signs within the system of language, while signification, or what is significant, clearly depends on the relationship between the two parts of the signs. Saussure uses an analogy with the game of chess to underline his point and stated, ‘A state of the board of chess corresponds exactly to a state of language’ and noted that the values of each chess piece depend on its position on the chessboard (see Ferdinand de Saussure, 1983, p. 88). The reader should also note the distinction between what is significant and value, Saussure notes that, ‘The French word mouton may have the same meaning as the English word sheep; but it does not have the same value. There are various reasons for this, but in particular the fact that the English word for the meat of this animal, as prepared and served for a meal, is not sheep but mutton. The difference in value between sheep and mouton hinges on the fact that in English there is also another word mutton for the meat, whereas mouton in French covers both’ (see Ferdinand de Saussure, 1983, p. 114).

Steve Woolgar used the term configuration to described a similar notion (see Steve Woolgar, ‘Configuring the User: The Case of Usability Trial’, in J. Law (ed.), A Sociology of Monsters, London, Routledge, 1991, pp. 57–99).

Raymond Williams, Culture and Society: 1780–1950, Columbia University Press, 1958.

I said gesture because both veil and headscarf have been a powerful symbol in Judeo-Christian faiths as well, and hence to peculiarize them only to one faithful segment is missing the forest for the trees. For instance see An Exhibition of “Veiled Women: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Women in Israel”; and Margalit Chu, The Power of Metaphor: Veils within Judo-Christianity and Islam, 1996 at: http://www.artpoetryfiction.com/essays/chu/veilsbody. html#prescript. Moreover, My intention here is not to argue for or against the nature of the veil, and more importantly such argument exceeds the scope of the present study. And yet, we argue that a sign of oppression like the veil should not be perceived as a natural part of any religion, but rather a direct consequence of manipulation of the faith. On this point, Karen Armstrong observed, ‘The women of the first ummah in Medina took full part in its [Islam] public life, and some, according to Arab custom, fought alongside men in battle. They did not seem to have experienced Islam as an oppressive religion, though later, as happened in Christianity, men would hijack the faith and bring it into line with the prevailing patriarchy.’ (See Karen Armstrong, Islam: A Short History, Modern Library, 2002, p. 16).

This is not a surprising observation since in the domain of politics, Machiavelli is well known for having argued that power depends upon legitimacy and social influence. In the case of Iran’s Army of Lady Ninjas, the act of legitimation becomes even more significant since discriminatory and prejudicial treatment of the entire population of the women of Iran must be justified and made to seem legitimate.

John D. Haynes, Internet Management Issues: A Global Perspective, Idea Group Publishing, 2002, p. 228.

Albert Borgmann, Holding On to Reality: The Nature of Information at the Turn of the Millennium, University of Chicago Press, 1999, p. 9.

Rolando V. Garcia, Drought and Man: The 1972 Case History, Volume 1: Nature Pleads Not Guilty, Pergamon Press, 1981, p. 7.

See Wikipedia under ‘Macy Conferences’.

It is called paradox because it underlines the pure version of quantum mechanics, which indicates that the cat exists in some indeterminate state, neither dead nor alive, until an observer looks into the box to see how things are getting on. ‘Nothing is real unless it is observed’.

Tom Stonier, Information and Meaning: An Evolutionary Perspective, Springer-Verlag, 1997. As a side note, I would like to point out that no one knows for sure if they were correct in using the verb instead of the noun. However, based on the connotations each implies, various questions can be raised such as: what impact would this apparently simple change have meant for the Information Communication Technology industry that today dominates all other sectors in terms of its share in Global GDP? What kind of paradigm shift would this change bring about? Would we still refer to the current era as the information age? How such a change would affect companies like IMB, Apple and Microsoft? And more importantly, what would such a change mean for the news industry both at the local and global level?

Stuart W. Pullen, Intelligent Design or Evolution? Why the Origin of Life and the Evolution of Molecular Knowledge Imply Design, Intelligent Design Books; 1st edition, 2005, p. 18.

Melanie Mitchell, An introduction to Genetic Algorithms, MIT Press, 1998, p. 67. However, Mitchell explained further that while the Lamarckian hypothesis is rejected by almost all biologists, she still believed ‘learning (or more generally, phenotypic plasticity) can indeed have a significant effects on evolution, though in less ways than Lamarck suggested’ (ibid.). She then provided an example to explained her position, ‘an organism that has the capacity to learn that a particular plant is poisonous will be more likely to survive (by learning not to eat the plant) than organisms that are unable to learn this information, and thus will be more likely to produce offspring that also have this leaning capacity. Evolutionary variation will have a change to work on this line of offspring, allowing for the possibility that the trait — avoiding the poisonous plant — will be discovered genetically rather than learned anew each generation. Having the desired behavior encoded genetically would give an organism a selective advantage over organisms that were merely able to learn the desired behavior during their lifetimes, because learning behavior is generally less reliable process than developing a genetically coded behavior; too many unexpected things could get in the way of learning during an organism’s lifetime. Moreover, genetically encoded information can be available immediately after birth, whereas leaning takes time and sometimes requires potentially fatal trial and error. In short, the capacity to acquire a certain desired trait allows the learning organism to survive preferentially, thus giving genetic variation the possibility of independently discovering the desired trait. Without such learning, the likelihood of survival — and thus the opportunity for genetic discovery — decreases.’ (Ibid., p. 67.)

‘It’s just a question of timing’ The Independent, May 19, 2004 at http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/its-just-a-question-of-timing-6169508. html.

However, there are those who believe, like W. H. Zurek, that when an interpretation occurs consciousness is at least ultimately encountered. In this respect, the perception of unique reality ‘would undoubtedly have to involve a model of consciences, since what we are really asking concerns our (observer’s) impression that we are conscious of just one of the alternative’. (See W. H. Zurek, ‘Preferred Sets of States, Predictability, Classically, and Environment Induced Decoherence’, in J. J. Halliwell, J. Pérez-Mercader and W. H. Zurek (eds), Physical Origins of Time Asymmetry, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 206.

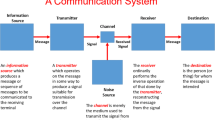

Claude E Shannon and Warren Weaver, The Mathematical Theory of Communication, University of Illinois Press, 1971.

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver, 1971, p. 4.

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver, 1971, p. 5.

John D. Haynes, Perspective Thinking for Inquiring Organisations, Information Science Publishers, 2008, p. 99.

Grandon T. Gill and Eli Cohen, edited, Foundation of information Science 1999–2008, Information Science Publishers, 2009, pp. 60.

Paul Martin Lester, Visual Communication: Images with Message, Cengage Learning, 2006, p. 73.

Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion, Greenbook Publication, 2010, p. 90.

Paul Martin Lester, 2006, p. 73.

Walter Lippmann, 2010, p. 92.

Floyd Matson, Broken Image: Man, Science and Society, G. Braziller, 1964. See particularly the first part, ‘The Great Machine’, in which Matson provides an excellent exposition of his argument. However, in later chapters Matson’s argument seems less convincing for a non-physicist like me. For instance, his interpretation of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle as restoring ‘indeterminacy’ to ‘nature’ — in the essence that indeterminacy means control by purpose rather than by cause — is less clear than his ‘the great machine’ exposition.

According to Kuhn, normal science ‘means research firmly based upon one or more past scientific achievement, achievements that some particular scientific community acknowledge for a time as supplying the foundation for its further practices’. (See Thomas S, Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 3rd edition, University of Chicago, 1996, p. 10.)

Ibid., p. 24.

Abraham H. Maslow, The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance, Harper and Row, 1966, p. 2.

Abraham H. Maslow, Motivation and Personality, Harper and Bros., 1954, p. 327.

Edward M. White, ‘Holisticism’, College Composition and Communication, vol. 35, no. 4 (December 1984), p. 400.

Abraham H. Maslow, The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance, Harper and Row, 1966, p. 72.

From purely personal experience I have observed that those who subscribe to a scientific method frequently see other approaches as irrelevant and even trivial. In my opinion, however, such judgment not only illustrates the fallacy of their paradigm, but also refutes its own philosophical objectives, which is to inform. As science removes itself from the area of everyday life through objectification processes, it inevitably creates a culture that is composed of fixed values and intellectual horizons. As a result, such culture does not inform our soul and intellect but rather is a mere reflection of inner inspiration and goal, that is, a faculty that only deals with internal representations, intents, and aspirations.

Abraham H. Maslow, The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance, Zorba Press 1966, p. 23.

Abraham H. Maslow, The Psychology of Science, 1966, p. 75.

See http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/2011/aug/15/information-paradox-simplified. It is noteworthy to add that the information should not be considered ‘lost’ if it is merely inaccessible in the same way that mass is not ‘lost’ when it falls into a black hole, or charge. Why do we think information is ‘lost’ when matter passes through the event horizon? This question begs further questions like ‘Is information something truly physical?’

The controversy over the black hole information paradox is described in detail in Susskind’s 2008 book, The Black Hole War: My Battle with Stephen Hawking to Make the World Safe for Quantum Mechanics, Little, Brown and Company; 1st edition, 2008.

F. Manuel, Isaac Newton, Historian, Harvard University Press, 1963, p. 138.

C. Shannon and W. Weaver, The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Original work published in 1948. It should be noted that Shannon and Weaver’s The Mathematical Theory of Communication is not actually a co-authored book. The book consists of two essays: Weaver’s ‘Recent Contributions to the Mathematical Theory of Communication’ and Shannon’s earlier paper, with the new title ‘The Mathematical Theory of Communication’. In fact as Lai Ma observed, ‘Most readings of information theory are based on Warren Weaver’s exposition of Shannon’s theory’ (see Lai Ma, ‘Meanings of Information: The Assumptions and Research Consequences of Three Foundational LIS Theories’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 2012, vol. 63, no. 4, p. 717).

In 1983, Shaw and Davis already stated that ‘[M]uch theoretical work in information science is based on the Shannon-Weaver model of communication’ (D. Shaw and C. H. Davis, ‘Entropy and information: A multidisciplinary overview’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 1983, vol.34, no. 1, p. 71). More recently, Kalbach (2009) claims that Shannon and Weaver are the ‘fathers of modern information and communication theory’ and that the concept of uncertainty in their work ‘underlies most aspects of our lives’ (J. Kalbach, ‘On uncertainty in information architecture’, Journal of Information Architecture, 2009, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 48.

The reader should note that the Shannon-Weaver Model will be analyzed in more detail in a later section.

For instance, John Wheeler’s proposal of it from bit (information is physical) argues that anything physical, any it, ultimately drives its very existence entirely from discrete detector-elicited information-theoretic answers to yes or no quantum binary choices: bits.

Lai Ma, ‘Meanings of Information: The Assumptions and Research Consequences of Three Foundational LIS Theories’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 2012, vol. 63, no. 4, p. 717.

A. F. Chalmers, What is This Thing Called Science?, Open University Press, 3rd edition, 1999, p. 104.

A. F. Chalmers, 1999, pp. 105. The reader should also note that For instance, the relative precision of the Shannon’s definition of information stems from the fact that the concept constructed within a well-defined role and closely-knit mathematical framework and logic.

Bertram C. Brookes, ‘The foundation of information science: Part I. Philosophical aspects’, Journal of Information Science, 1980, vol. 2, p. 127.

Ibid., p. 128.

Ibid., p. 130.

Ibid., p. 132 (emphasis added).

Ellen Bonnevie, ‘Emerald Article: Dretske’s semantic information theory and meta-theories in library and information science’, Journal of Documentation, vol. 57, no. 4, July 2001, p. 523.

Ibid.

Bertram C. Brookes, ‘Robert Fairthorne and the scope of information science’, Journal of Documentation, 1974, vol. 30, no. 2, 1974, pp. 142–3.

See Warren Weaver, ‘Recent Contributions to The Mathematical Theory of Communication’, in Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver, The Mathematical Theory of Communication, University of Illinois Press, 1971 (1963, 1949).

Hans Christian von Baeyer, Information: The New Language of Science, Harvard University Press, 2004, pp. 32–3.

Hans Christian von Baeyer, Information: The New Language of Science, Harvard University Press, 2004, p. 33. However, the term observer requires a bit of explanation. In quantum mechanics, ‘observation’ is synonymous with quantum measurement and ‘observer’ with a measurement apparatus and ‘observable’ with what can be measured. Thus the quantum mechanical observer does not necessarily present or solve any problems over and above the (admittedly difficult) issue of measurement in quantum mechanics. The quantum mechanical observer is also intimately tied to the issue of observer effect. A number of interpretations of quantum mechanics, notably ‘consciousness causes collapse’, give the observer a special role, or place constraints on who or what can be an observer. For instance, Fritjof Capra writes, ‘The crucial feature of atomic physics is that the human observer is not only necessary to observe the properties of an object, but is necessary even to define these properties. … This can be illustrated with the simple case of a subatomic particle. When observing such a particle, one may choose to measure — among other quantities — the particle’s position and its momentum’. However, other authorities downplay any special role of human observers, ‘Of course the introduction of the observer must not be misunderstood to imply that some kind of subjective features are to be brought into the description of nature. The observer has, rather, only the function of registering decisions, i.e., processes in space and time, and it does not matter whether the observer is an apparatus or a human being; but the registration, i.e., the transition from the “possible” to the “actual,” is absolutely necessary here and cannot be omitted from the interpretation of quantum theory’ (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Observer_%28quantum_physics%29).

In Everett’s view, the whole universe is a wave-function (the universal wave-function), describing a dizzying multiplicity of worlds. In this interpretation, observers are treated like computers, or as any other measuring device, as if their memories could be written out on magnetic tape. To understand the subjectively probabilistic nature of their experiences, one correlates the answer given by an observer with questions asked by a so-called external agency, who is likewise an observer and thus internal to the combined quantum system. Everett believed that this line of reasoning shows there is no conflict between the objective deterministic evolution of the wave-function and the subjective indeterminate experiences of an observer (see Wikipedia, ‘Quantum mind-body problem’ at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_mind%E2%80%93body_problem#cite_note-20).

David Bohm and Basil J. Hiley, The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory, Psychology Press, 1995, p. 285.

Murray Gell-Mann, The Quark and the Jaguar: Adventures in the Simple and the Complex, Little, Brown & Company, 1994, p. 155.

Ibid.

Jeremy Bernstein, Physicists on Wall Street and Other Essays on Science and Society, Springer, 1st edition, 2008. Also see David Bohm and Basil J. Hiley, The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory, Routledge (reprint edition), 1995.

Hans Christian von Baeyer, 2004, p. 33.

For instance see R. Lachman, J. L. Lachman and E. C. Butterfield, Cognitive Psychology and Information Processing: An Introduction, Taylor & Francis, 1979.

For instance see Annie Lang and Patrick Lanfear, ‘The Information Processing of Televised Political Advertising: Using Theory to Maximize Recall’, Advances in Consumer Research, 1990, vol. 17, pp. 149–58. The paper is available at: http://www.acrwebsite.org/search/view-conference-proceedings. aspx?Id=7010. See also interesting discussion in Kurt Lang and Gladys Engel Lang, ‘The Impact of Polls on Public Opinion’, American Academy of Political and Social Science, March 1984, vol. 472, pp. 129–42. The entire volume, in fact, is designated to issues of polling, politics and public opinion.

Daniel Bell, The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism, pp. xxv-xxvi.

Ibid., however the original quote comes from Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot, Project Gutenberg Consortia Center Collection, Accessed at http://ebooks.gutenberg.us/WorldeBookLibrary.com/godot.htm.

Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker: Die Einheit der Natur, op.cit. pp. 351–2: “1. Information ist nur, was verstanden wird 2. Information ist nur, was Information erzeugt.” (‘1. Information is only what can be understood and 2. Information is only what produces information.’). See Carl-Friedrich von Weizsacker, The Unity of Nature, Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1980.

Rafael Capurro and Birger Hjorland, ‘The Concept of Information’, Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 2003, vol. 37, issue 1, p. 362.

C. F. Weizsäcker, Thomas Gornitz and Holger Lyre (eds), The Structure of Physics, Springer, 2010, p. 214.

Hans Christian von Baeyer, Information: The New Language of Science, Harvard University Press, 2004, p. 18.

In this book the popular meaning of the term is quite appropriate. Webster defines mindset as a ‘fixed mental attitude formed by experience, education, prejudice, etc.’ Correspondingly, the mindset factor is the reason why people are predisposed to certain perceptions. I refer the interested reader on this topic to Glen Fisher’s book called Mindset published by International Press, Inc.

Prior to this date, a few isolated works had attempted to take a step toward a general theory of communication. However, these works failed to establish communication/information as an accepted field of research. Here I underline two examples. First, in 1935, the statistician Ronald. A. Fisher had proposed a measure of information in a statistical sample, which in the simplest case of a normal distribution amounts to the reciprocal of the variance (see Leonard J. Savage, ‘On Reading R. A. Fisher’, The Annals of Statistics, 1976, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 441–500.). Second, the work of Nobel Prize winner Dennis Gabor comes to mind, when he introduced in 1946 in his ‘Theory of Communication’ a method to represent a one-dimensional signal in two dimensions, with time and frequency as coordinates. Gabor’s research in communication theory was driven by the question how to represent locally as good as possible by a finite number of data the information of a signal. He was strongly influenced by developments in quantum mechanics, in particular by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and by the fundamental results of two papers published in the 1920s by Harry Nyquist and Ralph Hartley, who were both still research leaders at Bell Labs when Shannon arrived in the early 1940s.

The most common definition is ‘binary digit’, usually a 0 or a 1 in a computer. This definition allows only for two integer values. The definition that Shannon came up with is an average number of bits that describes an entire communication message (or, in molecular biology, a set of aligned protein sequences or nucleic-acid binding sites). This latter definition allows for real numbers. Fortunately the two definitions can be distinguished by context (see Tom Schneider and Karen Lewis, A Glossary for Biological Information Theory and the Delila System, at http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/glossary.html.

This is the main reason why Shannon’s information measures are most easily applied to a message that is composed of a string of binary possibilities.

Another example is if you ask for a milkshake and the waiter says ‘chocolate or vanilla?’ In theory he just wants one bit of information from you. He might ask ‘whipped cream?’; he wants another bit. ‘sprinkles?’; another bit. But notice that these two possibilities and another two and another two actually multiply for a total of eight. That is, the total number of possibilities is two to the power of the number of bits; here 2A3 = 8, or eight possible outcomes; (1) chocolate no whipped cream no sprinkles; (2) chocolate no whipped cream sprinkles; (3) chocolate whipped cream no sprinkles; (4) chocolate whipped cream sprinkles, etc. (See http://daniel-wilkerson.appspot.com/entropy.html.)

James Gleick, The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood, Vintage, 2012.

Shannon’s formula is C = W log2 (1 + S/N), where C is channel capacity measured in bits/second, W is the bandwidth in Hz, S is the signal level in watts across the bandwidth W, and N is the noise power in watts in the bandwidth W.

C. Shannon and W. Weaver, The Mathematical Theory of Communication, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, IL, 1971 (Original work published in 1948), p. 9. It should be noted that Shannon and Weaver’s The Mathematical Theory of Communication is not actually a co-authored book. The book consists of two essays: Weaver’s ‘Recent Contributions to the Mathematical Theory of Communication’ and Shannon’s earlier paper, with the new title ‘The Mathematical Theory of Communication’.

Hans Christian von Baeyer, 2004, p. 89.

As von Baeyer explained, ‘The result makes sense, because 6 is halfway between 4 and 8, and its log correspondingly falls between 2 and 3. The specific number can be verified by pinching a calculator: 22.585 = 6.000).’ p. 118.

See Hans Christian von Baeyer, 2004, p. 30. In short, you’ll get more. The nature of digital technology allows it to cram lots of those 1s and 0s together into the same space an analog signal uses. Like your button-rich phone at work or your 200-plus digital cable service, that means more features can be crammed into the digital signal.

For a better understanding of the differences between binary code and analog technology see: http://telecom.hellodirect.com/docs/Tutorials/AnalogVsDigital.1.051501.asp.

For instance, in 1981 a price of storing a Gigabyte was about $300,000. However, in 2010 the similar storing was estimated at about $0.10. See http://boingboing.net/2011/03/08/tracking-the-astound.html.

Humberto R. Maturana and Francisco Varela, Tree of Knowledge, New Science Library/Shambhala Publications, 1987.

Lauria and Belardo further observed, ‘In order for the communication between two entities, say two individuals, to be understood, that is to say, that in order for information to result from the informing process, it is necessary for the sender’s message to be correctly interpreted by the receiver. In order for this to happen, one of three conditions must be met: the sender and the receiver must have had similar experiences in a given domain; the sender must be able to anticipate what the receiver knows or does not know; the receiver must be able to ask the right question. The first condition is met when both the sender and the receiver have had similar experiences. In such situations, a degree of conformity exists between the tacit knowledge of both the sender and the receiver. This helps ensure the efficient and effective transfer of knowledge. The second and the third condition, we contend, can only be satisfied when either or both parties employ critical thinking.’ (See Eitel J. M. Lauria and Salvatore Belardo, 2009, p. 219–20.)

Wittgenstein explains, ‘So you are saying that human agreement decides what is true and what is false? — It is what human beings say that is true and false; and they agree in the language they use. That is not agreement in opinions but in form of life.’ See Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigation: The German Text, with a Revised English Translation, 3rd edition, Blackwell, 2001, p. 75.

Humberto R. Maturana and Francisco J. Varela, Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living, D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1st edition, 1980, pp. 27–8.

Fernando Albano Maia de Magalhaes Ilharco, Information Technology as Ontology, Doctoral Thesis, London School of Economics, Department of Information Systems, 2002, p. 144.

I define sensible information as equivalent of useful because information as such would lead to some intended consequences, while null information bears no consequences at all (see Hans Christian von Baeyer, 2004, p. 33).

C. Shannon and W. Weaver, 1971, p. 8.

See http://graham.main.nc.us/~bhammel/wilde.html.

The emphasis is added.

A specificity of information refers to the content of information and its degree of effectiveness. Thus, at the lowest level the most specific piece of information would be an individual response to information received.

For instance, firms can now serve personalized recommendations to consumers who return to their website, based on their earlier browsing history. At the same time, online advertising has greatly advanced in its use of external browsing data across the web to target internet ads appropriately (see Anja Lambrecht and Catherine Tucker, ‘When does retargeting work? Timing information specificity’ at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm? abstract_id=1795105.

For instance, Ted Brader, PhD, a University of Michigan political scientist, explores the power of political campaign to change people’s mind and behavior in his book, Campaigning for Hearts and Minds: How Emotional Appeals in Political Ads Work; or Frank Biocca’s book entitled Television and Political Advertising: Volume I: Psychological Processes; and Melanie C. Green’s book, Persuasion: Psychological Insights and Perspectives.

McLuhan’s exact quotation is, ‘the electric light is pure information. It is a medium without a message, as it were, unless it is used to spell out some verbal ad or name.’ See McLuhan and Lewis H. Lapham, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, MIT Press, 1994, p. 8.

Of course, this process can be interrupted or completely eliminated, if, and only if, the information content of news exhibits facts and not observation, opinion, or pseudo-truth.

Refers to ‘communications that incorporate multiple forms of information content and processing’.

Noise is generally perceived to introduce error, uncertainty, losses and inefficiency into any system.

Hans Christian von Baeyer, 2004, p. 121.

A random variable can be viewed as a mathematical abstraction for quantification of a ‘measurement’, ‘observation’, or ‘experiment’ in the real world. Mathematically speaking, a random variable is a function of a set what is called ‘probability space’ or a state you don’t know anything about. You could think of the probability space as the complete state of the world beyond your knowledge. For instance, your door bell rings, if you do not expect anyone, then whoever is outside ringing the bell is random to you. Another way to think about it is that mathematics is deterministic, so for us to be able to apply mathematics to this question, we have to squeeze all the randomness down into one thing, so we put it into the mysterious and unknowable ‘probability space’ and then think of our random variables as being deterministic functions of it.

Hans Christian von Baeyer, 2004, p. 119.

Heisenberg, in uncertainty principle paper, 1927, p. 185. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qt-uncertainty/.

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, University of Chicago Press, 1958, p. 261.

If all the microstates have equal mathematical or logical probability (equiprobable), the statistical thermodynamic entropy reduces to the form S = k log W, which is carved on Boltzmann’s tombstone. In this form, W simply implies the number of ways, which is shorthand for ‘the number of ways in which a system can be prepared without affecting the measured properties of the system’. For detailed and fascinating discussion of this topic see Hans von Baeyer, 2004, pp. 95–7.

The reader should note that by regarding information in terms of a specific arrangement relative to all probable arrangements, e.g., meaning, Shannon is able to describe information as a probability.

C. Shannon and W. Weaver, 1971, p. 49.

There are: (1) H should be continuous in the pi; (2) If all the pi are equal pi = 1/n, then H should be a monotonic increasing function of n. With equally likely events there is more choice, or uncertainty, when there are more possible events; and (3) If a choice be broken down into two successive choice, the original H should be the weighted sum of the individual values of H. (See Shannon and Weaver, p. 49.)

Despite all that, there is an important difference between the two quantities. The information entropy H can be calculated for any probability distribution (if the ‘message’ is taken to be that the event i which had probability pi occurred, out of the space of the events possible), while the thermodynamic entropy S refers to thermodynamic probabilities pi specifically. Furthermore, the thermodynamic entropy S is dominated by different arrangements of the system, and in particular its energy, that are possible on a molecular scale. In comparison, information entropy of any macroscopic event is so small as to be completely irrelevant (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entropy_in_thermodynamics_and_information_theory).

See M. Tribus and E. C. McIrvine, ‘Energy and Information’, Scientific American, vol. 225, no. 3, September 1971, pp. 179–88.

C. Shannon and W. Weaver, 1971, pp. 20–1.

Proofs of these statements are available at: http://www.lecb.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/information.is.not.uncertainty.html#tribus.

Glen N, Lewis, ‘The Symmetry of Time in Physics’, Science, June 6, 1930, vol. 71, no. 1849, p573. A classic example of a highly ordered, low entropy system — a glass of pure water — perhaps may also clarify this point. In this case, there is a trivial amount of uncertainty since it is easy to observed H2O molecules floating around. However, a system with higher entropy, like a mud pie, does not convey such certainty — the information that it is a mud pie does not enable us to confidently guess the identity of any one molecule, because mud consists of lots of molecules, all mixed up (see Robert Wright, Three Scientists and Their Gods, Harper and Row, 1988, p. 88).

Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics, Second Edition: or the Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, MIT Press, 1965, p. 11.

Jonathan B. Spira, Overload! How Too Much Information is Hazardous to your Organization, Wiley, 1st edition, 2011. Also see Richard Wurman’s book called Information Anxiety (Doubleday, 1989), in which he warned us ‘the greatest crisis facing modern civilization is going to be how to transform information into structured knowledge. Society faces an over-abounding of data that need to be evaluated and acted upon.’

For instance, educational or psychological materials suggest that information overload could be an underlying cause of adolescent suicides (Bem Allen, ‘Youth Suicide’, Adolescence, 1987, vol. 22, pp. 271–89), retarded reading skills (W. John Harker, ‘Implications from Psycholinguistics for Secondary Reading’, Reading Horizons, 1979, vol. 19, pp. 217–21; Russell Saunders, ‘A Modified Impress Method for Beginning Readers’, 1983, ERIC CD-ROM, ERIC 227457), or the inability to complete tasks (Frederik Bergstrom, ‘Information Input Overload, Does it Exist? Research at Organism Level and Group Level’, Behavioral Science, 1995, vol. 40, pp. 56–75).

Robert Asen, ‘Toward a Normative Conception of Difference in Public Deliberation’, Argumentation and Advocacy, 1999, vol. 25 (Winter), p. 125.

See Jürgen Habermas, ‘Further Reflections on the Public Sphere’, in Craig Calhoun (ed.), Habermas, and the Public Sphere, MIT Press, 1993, p. 437. The notion of the public sphere and Habermas’ analysis will be examined in later chapters.

Fernando Albano, p. 137.

G. B. Davis and M. H. Olson, Management Information System: Conceptual Foundation, Structure and Development, McGraw-Hill, 1985, p. 30.

Henry C. Lucas, Information System Concepts for Management, 4th edition, McGraw-Hill, 1990, p. 511.

Henry Jenkins and David Thorburn, 2004, p. 39.

C. Shannon and W. Weaver, 1971, p. 27.

Abraham H. Maslow, 1966, Foreword by Arthur G. Wirth, p. xi.

Abraham H. Maslow, 1966, p. 75.

Abraham H. Maslow, The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance, Harper and Row, 1966, p. 84.

Ellen Bonnevie, ‘Emerald Article: Dretske’s semantic information theory and meta-theories in library and information science’, Journal of Documentation, vol. 57, no. 4, July 2001, p. 521.

Fritz Machlup and Una Mansfield (eds), The Study of Information: Interdisciplinary Messages, Wiley, 1983, p. 660.

Ibid.

L. Qvortrup, ‘The controversy over the concept of information. An over-view and a selected and annotated bibliography’, Cybernetics & Human Knowing, 1993, vol. 1, no. 4, p. 4. The paper can be accessed at: http://www.burlgrey.com/xtra/infola/infolap3.htm.

Fred I. Dretske, Knowledge and the Flow of Information, Center for the Study of Language and Information, 1981 or 1999.

Yehoshua Bar-Hillel and Rudolf Carnap, An Outline of A Theory of Semantic Information, MIT Press, 1952. The book is available at survivor99.com.

Ellen Bonnevie, ‘Dretske’s semantic information theory and meta-theories in library and information science’, Journal of Documentation, 2001, vol. 57, issue 4, p. 522.

Ibid.

Fred Dretske, 1981, p. 45.

For instance see A. Scarantino and G. Piccinini, ‘Information Without Truth’, Metaphilosophy, 2010, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 313–30. On a different note, Israel and Perry observed that information is not a property of facts but it is context (or constraint) dependent, and point out the difference between what they called pure information and incremental information (see D. Israel and J. Perry, ‘What is information?’, in P. Hanson (ed.), Information, Language and Cognition, University of British Columbia Press, 1990, pp. 1–19). Later, however, they also make an additional distinction separating information content, which ‘is only information when the constraints and connecting facts are actual’, and information (see D. Israel and J. Perry, ‘Information and architecture’, in J. Banvise, J. M. Gawron, G. Plotkin, and S. Tutiya (eds), Situation Theory and its Applications, Stanford University Center for the Study of Language and Information, p. 147). Perhaps an example would make this point less ambiguous. Consider the following sentence: The clock indicates that it is six o’clock. According to Israel and Perry, ‘In an information report, the initial noun phrase is called the informational context. The proposition indicated by the information context they call the informational content.’ (see http://jacoblee.net/occamseraser/2010/10/03/notes-on-what-is-information-by-david-israel-and-john-perry/. In this context, the clock is the carrier of the information.

F. I. Dretske, Knowledge and the Flow of Information, MIT Press, 1981, pp. 63–4.

F. I. Dretske, 1981, pp. 80–1.

F. I. Dretske, 1981, pp. 91–2.

For a detailed discussion on the difference between truthfulness and truth see Bernard Williams, Truth and Truthfulness: An Essay in Genealogy, Princeton University Press, 2004. Chapter One of this book is available at: http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/s7328.html. See also Harvey Siegel, ‘Relativism, truth, and incoherence’, SYNTHESE, 1986, vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 225–59.

It should be note that this topic will be discussed in more detail under heading, ‘propaganda versus information’.

Luciano Floridi, ‘Is Semantic Information Meaningful Data?’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, March 2005, vol. Lxx, no. 2, p. 366.

Norma Romm, ‘Implications of regarding information as meaningful rather than factual’, in R. L. Winder, S. K. Probert, and I. A. Beeson (eds), Philosophical Aspects of Information Systems, Taylor and Francis, 1997, pp. 23–34.

Rafael Capurro and Birger Hjorland, 2003, p. 46.

Sandra Braman, ‘Defining information: An approach for policymakers’, Telecommunications Policy, 1989, vol.13, no.1, pp. 233–42.

Abraham H. Maslow, 1966, p. 77.

Copyright information

© 2014 Elias G. Carayannis and Ali Pirzadeh

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Carayannis, E.G., Pirzadeh, A. (2014). Information Culture. In: The Knowledge of Culture and the Culture of Knowledge. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137383525_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137383525_3

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-52133-3

Online ISBN: 978-1-137-38352-5

eBook Packages: Palgrave Business & Management CollectionBusiness and Management (R0)