Abstract

Although inequality between persons can refer to a great variety of issues concerned with the disparate treatment and circumstances of individuals, economic discussion has focused on those aspects that relate to the acquisition and expenditure of income. As a consequence, the study of personal inequality has become largely synonymous with the distribution of income among individuals or households. Early contributors to this subject tended to provide an overall perspective on personal income distribution. In recent years, however, more attention has been paid to the particular dimension of inequality under investigation. Consideration has also been given to the precise way in which ‘inequality’ should be interpreted and measured, a trend most evident in the adjustments applied to observed incomes in order that the ‘true’ degree of inequality is revealed.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Although inequality between persons can refer to a great variety of issues concerned with the disparate treatment and circumstances of individuals, economic discussion has focused on those aspects that relate to the acquisition and expenditure of income. As a consequence, the study of personal inequality has become largely synonymous with the distribution of income among individuals or households. Early contributors to this subject tended to provide an overall perspective on personal income distribution. In recent years, however, more attention has been paid to the particular dimension of inequality under investigation. Consideration has also been given to the precise way in which ‘inequality’ should be interpreted and measured, a trend most evident in the adjustments applied to observed incomes in order that the ‘true’ degree of inequality is revealed.

An initial distinction may be made between those studies which examine the origins of income dispersion and those which are interested in its consequences. The principal concern of the latter is inequality in living standards, or levels of well-being, and here the appropriate methodology is well established. For each household we require a measure of the level of its resources relative to its needs. The resource variable is typically identified with income, so that income distribution is the traditional point of departure in the study of unequal living standards. Ideally, however, income should be interpreted in a broad sense to include not only monetary receipts, but also unrealised capital gains, non-pecuniary benefits and household production which is not marketed. In addition, a long run income concept such as ‘permanent income’ or ‘lifetime income’ is preferred to the short run concept (weekly, monthly or annual) which applies to most of the readily available data. These incomes should then be adjusted to allow for different household circumstances. One type of adjustment concerns family characteristics, such as the number and ages of family members, and is accomplished by the use of household equivalence scales. A second type of adjustment relates to the environment in which the household operates and covers such factors as the prevailing level of commodity prices; the shelter, heating and transportation requirements associated with household location; and the level of provision of public goods and services. The aim, as before, is to achieve comparability between households in different circumstances. Needless to say, while this programme of adjustments may be generally accepted as the ideal, most empirical studies of living standards fall a long way short of the target.

A much larger body of literature is concerned with the causes of income inequality. This work focuses on the experience of individuals in factor markets and covers a wide range of issues on which opinions seldom agree. It will be helpful to begin by splitting the income y of an individual into components and writing

where ri and xi are the ‘price’ and ‘quantity’ associated with the ith component of income. A decomposition of this form would be appropriate if the xi denoted the individual’s endowments of productive factors, such as labour, capital and land, and the ri represented the corresponding factor prices. This immediately suggests two principal causes of income inequality: differences in the endowments of productive resources which individuals own; and the structure of factor prices determined by the combination of institutional, market and social forces which we will call the common environment of individuals. Further refinement of this line of reasoning can be achieved by extending the coverage of the xi to include a variety of other characteristics, and by looking back towards the source of the characteristics: to inheritance, in the form of genetic traits, material wealth and family advantage; to innate and acquired skills; and to the choices individuals make in respect of occupation, location and workhours. There is also, inevitably, a portion of income, often attributed to ‘chance’ or ‘luck’, which is not systematically related to any of these factors.

Theories of income distribution differ not only in the particular influences and mechanisms that are stressed, but also in their view of what a theory of income distribution should set out to accomplish. One aim is to account for the overall degree of inequality at any date, and the pattern of changes in aggregate inequality that take place over time. Another topic of interest is the characteristic shape of the frequency distribution which incomes tend to follow. A third objective is to explain why different individuals happen to have different incomes. All three of these issues are valid concerns, and all would be addressed in a satisfactory general theory. On the whole, however, a distinct literature has developed on each of the questions. These are reviewed in turn below.

Changes in Income Dispersion Over Time

Explanations of changes in income inequality over time have typically drawn attention to the features of the common environment and to the consequent pattern of factor prices. Factor prices play a significant role in most of the discussion of income distribution prior to 1900, and even up to the middle of this century, as indicated by the selection of papers published by the American Economic Association in 1946. This is perhaps a reflection of the rigid social structure in the 19th century, which made it natural to assume that the resource endowments of individuals remained relatively constant over time. In those circumstances the first priority was to account for the level of factor prices or factor shares. Once this was done, aggregate factor payments could be allocated among individuals according to a prearranged pattern of entitlement. A theory of factor prices was, in effect, a sufficient explanation for the distribution of personal income.

The tendency to submerge the theory of personal income distribution within the grander themes of Labour, Capital and Land was not without its critics. Cannan (1905) was prompted to suggest that a student seeking an explanation for the riches and poverty surrounding him would return home in disgust from a typical lecture on the subject. He argued that more attention should be paid to the way that aggregate factor payments were shared between individuals, a suggestion taken up with enthusiasm by Dalton (1920) in one of the earliest and most outstanding volumes devoted to personal income distribution. The ideas of Cannan and Dalton had little immediate impact. But the importance they attributed to inheritance has certainly been echoed in subsequent research, most notably in connection with the sources of wealth inequality.

More recently, the explanation of long-run trends in income dispersion has been particularly associated with the work of Kuznets and Tinbergen, and again regards the common environment as the ultimate source of change. The programme of research that has developed from Kuznets (1955) is concerned with the relationship between economic growth and the distribution of income within countries, and sees demographic movements as a major influence on inequality. Countries begin with a fairly homogeneous population, largely employed in the traditional sector. In the course of development, individuals transfer into the modern sector causing income inequality to first rise and then fall, as the modern sector becomes dominant. Inequality within both the traditional and modern sectors may, however, remain constant. This suggests that observed variations in inequality could be spurious, reflecting the way in which data is recorded rather than a real change in the relative income positions of individuals. Other demographic factors, such as shifts in the age structure and household composition have also been cited as having a similar impact.

Tinbergen (1975) appeals to the common environment influences that determine the relative earnings of skilled and unskilled workers. In his view, the observed trend in income inequality is the outcome of a race between technology and education. Technological progress creates additional demand for skilled workers, while improved educational opportunities increases the supply. The direction of movement of the skilled–unskilled wage differential depends on the relative strength of these two forces. Over the course of this century, education has advanced faster than technology, driving down the relative earnings in professional and skilled occupations with notable consequences for income dispersion. The distinguishing characteristic of Tinbergen’s argument is the attention given to the operation of factor markets. Many other studies have been concerned with the role of education and training, but they tend to emphasize the process of skill acquisition and treat factor prices as exogenous data.

The Pattern of Income Frequencies

It has long been recognized that the density function for incomes has a characteristic shape, sufficiently regular and well documented to merit special attention. The major early contribution to this line of enquiry was undoubtedly Pareto, who, in a series of publications, including his Cours d’économie politique (1896), assembled evidence on personal incomes spanning more than four centuries and expounded his universal law of income distribution. Pareto noted that the data were closely matched by the formula

where y is a given level of income and N is the number of people with incomes above y. Furthermore, the slope coefficient α was always approximately 1.5. This, he argued, could not be a coincidence. The statistical regularity must indicate a natural state of affairs which would tend to reassert itself if, for any reason, the income distribution departed temporarily from its stable equilibrium.

Pareto’s results, and the inefficacy of redistributive policies which they seemed to imply, soon attracted both dedicated support and hostile opposition. The increasing availability of data eventually undermined the strong version of Pareto’s law. However the tendency for the upper tail of incomes to follow the Pareto curve (3) is well established, and remains one of the ‘stylized facts’ concerning the distribution of both income and wealth. Pareto also had a profound influence on many of the methodological developments that have subsequently taken place. His interest in the collection and summary of data, the parametric description of income frequencies, and the identification and investigation of observed statistical regularities, are all strongly echoed in later research.

Although high incomes tend to follow the Pareto relationship the Lognormal distribution is a better representation over the whole income range. This provides a clue as to how the observed pattern of incomes could arise. For just as normal distributions result from a large number of small and statistically independent effects which combine additively, so lognormal distributions emerge when the effects combine multiplicatively. More formally, if we replace income in (1) with the logarithm of income to obtain

and assume, say, that the yi are identically and independently distributed variables, then the income pattern will be approximately lognormal when n is sufficiently large. In this argument it is the statistical properties, rather than the origins, of the components yi that are significant. They may, therefore, be treated as unspecified random effects.

The notion that income distribution can be viewed as the outcome of a process governed by a large number of small random influences was developed by a number of authors, most notably Gibrat (1931) who formulated his ‘law of proportionate effect’, and Champernowne (1953) who demonstrated how the Pareto upper tail could emerge as a feature of the equilibrium distribution of a Markov Chain. Further modifications to these models were later shown to be capable of generating, as the limit of a stochastic process, a variety of other functional forms which have features in common with the lognormal and Pareto distributions, and which may be regarded as reasonable descriptions of the frequency distribution of income. As explanations of income inequality they have been criticized on the grounds that chance or luck, rather than systematic personal or market forces, appears to be the principal determinant of income differences. But the significance attached to this complaint depends on the question that is being addressed. If we are primarily interested in accounting for the overall features of the density function of incomes, it may be appropriate from an aggregate perspective to treat the incidence of personal success and failure as a random event, while simultaneously accepting that success and failure may be rationalized at the level of specific individuals.

Income Differentials

The dominant theme of recent research on personal income inequality is the explanation of income differentials – the reasons why particular individuals have different incomes. This work has several distinctive features. One is an increasing concern with empirical issues, and with the empirical evaluation of competing theories, facilitated by the availability of large-scale survey data and the means to process the information. Nowadays the question is not so often which factors have an impact on income distribution, but which factors have the most quantitative significance as explanations of observed income differences. Another distinctive feature is the emphasis placed on the distribution of earnings, again partly a result of the quantity and quality of earnings data. Earnings inequality is important, not only because wages and salaries form such a large proportion of income, but also because it reflects the extent to which labour markets operate fairly. As a consequence the explanation of the inequality of pay has become the main battleground for opposing views on the origins of personal inequality.

One method of approaching the question of earnings differentials is to regard the labour market as being composed of a set of individuals with different personal traits P, and a set of job opportunities offering various combinations of characteristics J. The process of matching people to jobs then generates a relation between personal traits, job characteristics and pay which is typically captured in an earnings equation of the form

where w denotes earnings or hourly wage rates, and R is a non-systematic or random effect. In this formulation, the coefficients α1 and α2 may be interpreted as the ‘prices’ which the market imputes to the various characteristics. Their values are often estimated from empirical data. Notice that equation (5) has similarities with (2) and, more especially, with (4). This indicates that the separate influences combine multiplicatively, rather than additively, as Gibrat had suggested earlier.

Many different views on the determinants of earnings can be accommodated within equation (5). One common argument claims that earnings are related to the ability or productivity embodied in individuals. Certain personal traits may therefore be valued because they indicate the actual productive performance that derives from either natural ability or the skills acquired as a result of education, training and work experience. Furthermore since perceived, rather than actual, productivity is rewarded in the market place, other characteristics may also be valued if firms believe them to be correlated with relevant variables that cannot be observed. This can account for the ‘prices’ imputed to educational credentials, family background, gender and race. There are, however, alternative explanations for sex and race discrimination: consumer and employer prejudice towards the goods and services provided by disadvantaged groups; and exploitation by firms of the different supply elasticities that arise from personal circumstances and role specialization within the family.

The structure of job opportunities and the prices imputed to job characteristics lead to a different set of considerations. One line of argument, associated with segmented labour market models and the Job Competition model (Thurow 1976), stresses the significance of the distribution of jobs across occupations and industries, which depends on the state of technology, the structure of markets and the other social and institutional factors contained in the common environment. It is this job distribution, together with customary wage and salary differentials, which is the principal determinant of earnings inequality. Personal characteristics appear to be important only because they are used by firms to ration entry into the more attractive jobs.

This argument suggests that the desirability of any given occupation is directly related to its imputed price. Exactly the opposite conclusion applies if the prices of the characteristics are interpreted in terms of Adam Smith’s (1776, Book 1, ch. X) concept of compensating differentials. For if individuals can choose to trade-off income against job characteristics such as occupation, location and working conditions, it is precisely those jobs with the least desirable features that need to pay more in order to attract an adequate workforce.

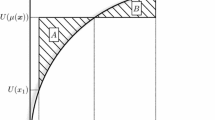

The notion that some part of earnings may compensate for other job features, and that the process of choice may help to explain observed income variations, has special significance in the analysis of personal inequality. This may be seen by considering a situation in which people are faced with a set of employment prospects each of which offers a level of income and a combination of other characteristics. If all individuals select from the same set of options, there is clearly no ‘true’ inequality in the sense of unequal opportunity. Yet people with different tastes will choose different alternatives, so observed incomes will typically vary. It follows that observed income dispersion may well exaggerate the true degree of inequality if some income differences are attributable to choice.

Individuals do not, of course, all face the same set of options. So different opportunities, as well as different choices, contribute to observed inequality. Much of the discussion of the determinants of earnings can be viewed in the context of the distinction between these two factors. Indeed, the most controversial aspects of the study of income distribution often reflect conflicting opinions on the relative importance of the ‘true’ component of inequality arising from different opportunities and the ‘spurious’ element of inequality that results from choice. Notice that choice is not the only mechanism that separates opportunities from outcomes. Chance also has a role to play if uncertain prospects are among the set of available options. It is therefore most appropriate to decompose inequality into three components: choice, chance and unequal opportunity. The influence of chance will, however, tend to disappear when we examine the typical experience of a group of individuals.

Those who stress the importance of unequal opportunity tend to focus attention on the contribution of natural ability, family background and discrimination. Here we might, perhaps, distinguish between two aspects of unequal opportunity: the unequal inherited endowments associated with natural ability and family background; and the unequal market treatment associated with discrimination. In contrast, the impact of choice is most clearly seen in the decisions relating to hours of work and geographical location. Individual preferences can also explain the choice of occupation and length of training. Thus, for example, a naive version of the Human Capital model suggests that the level of acquired ability is freely chosen under conditions of equal opportunity, so that the earnings differentials corresponding to education and training are purely compensatory. Refinements of the model, however, allow training opportunities to be influenced by ability and family background, and these factors, together with discrimination, are important elements of those arguments which emphasize the lack of equal and open access to training programmes. The impact of choice on skill levels depends, therefore, on the precise process by which skills are acquired and augmented.

The debate on the relative importance of unequal opportunity and choice for earnings inequality has its counterpart in the study of investment income, via the determinants of wealth distribution. Here, individual preferences are captured in the motives for saving: a desire to provide for retirement, to make bequests, or simply to practice thrift. Choices based on these preferences then determine savings behaviour and can account for some wealth differences in terms of past accumulation. Unequal opportunity, on the other hand, appears principally in the guise of material inheritance, but may also arise from the differences in incomes and family circumstances that affect the opportunities for saving.

Bibliography

American Economic Association. 1946. Readings in the theory of income distribution. Philadelphia: Blakiston.

Atkinson, A.B.. 1983. The economics of inequality, 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Cannan, E. 1905. The division of income. Quarterly Journal of Economics 19: 341–369.

Champernowne, D.G. 1953. A model of income distribution. Economic Journal 63: 318–351.

Dalton, H. 1920. The inequality of incomes. London: Routledge.

Friedman, M. 1953. Choice, chance, and the personal distribution of income. Journal of Political Economy 61: 277–290.

Gibrat, R. 1931. Les inégalités économiques. Paris: Sirey.

Kuznets, S. 1955. Economic growth and income inequality. American Economic Review 45: 1–28.

Mincer, J. 1958. Investment in human capital and personal income distribution. Journal of Political Economy 66: 281–302.

Pareto, V. 1896. Cours d’économie politique. Lausanne: F. Rouge.

Smith, A. 1776. In An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations, ed. E.R.A. Seligman. London: J.M. Dent, 1910.

Thurow, L. 1976. Generating inequality. London: Macmillan.

Tinbergen, J. 1975. Income distribution, analysis and policies. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Copyright information

© 2018 Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry

Shorrocks, A.F. (2018). Inequality Between Persons. In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_784

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_784

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-95188-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-349-95189-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences