Abstract

Entry – and its opposite, exit – have long been seen to be the driving forces in the neoclassical theory of competitive markets. Long-run equilibrium in such a market requires that no potential entrant finds entry profitable, and that no established firm finds exit profitable. In conjunction with the price-taking assumption, the first condition requires that price be no greater than minimum average cost, AC , and the second that price be no less than AC . Hence, in equilibrium, price is equal to AC . There is very little more to the theory of equilibrium in a competitive market than this simple yet powerful story of no-entry and no-exit.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Entry – and its opposite, exit – have long been seen to be the driving forces in the neoclassical theory of competitive markets. Long-run equilibrium in such a market requires that no potential entrant finds entry profitable, and that no established firm finds exit profitable. In conjunction with the price-taking assumption, the first condition requires that price be no greater than minimum average cost, AC , and the second that price be no less than AC . Hence, in equilibrium, price is equal to AC . There is very little more to the theory of equilibrium in a competitive market than this simple yet powerful story of no-entry and no-exit.

Surprisingly, considerations of entry and potential competition, so central to the economist’s view of competitive markets, played almost no role in oligopolistic and monopolistic markets until the work of Bain (1956) and Sylos-Labini (1956) in the mid–1950s. One important strand of the modern literature on entry combines, in essence, their insights into the role of potential competition in oligopolies with Schelling’s (1956) ideas on commitment. This essay focuses on this strand of literature.

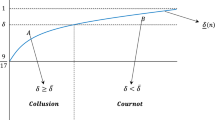

In reviewing Bain (1956) and Sylos-Labini (1956), Modigliani (1958) proposed what has come to be known as the limit-output (more commonly, limit-price) model, which is a formalization of one of the key ideas in these books. One version of this model has been the focal point of much of the recent literature on entry. Consider a market for some undifferentiated good, currently served by one established firm, in which demand and cost conditions are unchanging over an infinite time horizon. Now suppose that all potential entrants take the established firm’s output today, denoted by X, as the output which it will produce tomorrow and forever – the so-called Sylos postulate. Let X denote the smallest value of X such that the maximized profit of a representative potential entrant is non-positive. This value, X , is called the limit output (and the corresponding price the limit price) because, given the Sylos postulate, there will be no entry if and only if X ≥ X . (We assume for convenience that zero profit does not induce entry.)

Two important insights are already clear. First, potential competition constrains the ability of the established firm to exploit its position of market power since the no-entry condition (X ≥ X) places a lower bound on industry output in long-run equilibrium. Second, by producing at least X units of output, the established firm can deter entry. In one case central to the evolution of the literature, entry deterrence is also always profitable.

Suppose that the established firm’s average cost function is nowhere upward-sloping, and that the interest rate is not too high. In this situation, the established firm will always choose to deter entry by producing at least X . There are two sorts of solutions. If the ordinary monopoly output, M, is greater than or equal to X , then the monopolist will produce M, and we have what we could call natural monopoly, in the positive sense of the term. If M < X , the monopolist produces X to deter entry strategically, a case of artificial monopoly. When M < X the monopolist must choose between deterring and accommodating entry. Relative to the deterrence strategy – produce X today and forever – accommodation produces larger profit for the one established firm today (since today’s output will be M) but smaller profit tomorrow and forever (since price will be no higher than the limit price and the established firm’s output will be less than X ). If the rate of interest is not too high, it is obvious that the established firm will choose to deter entry.

The essence of both solutions is a message which the established firm wants to communicate to potential entrants. ‘If you enter, then my output will be (no smaller than) X .’ This ‘deterrence message’ has the property that it deters entry – if it is believed. It raises the obvious credibility question, ‘Would the established firm really produce the promised output post-entry’? Much of the recent literature on entry has implicitly or explicitly focused on this question. Four interrelated insights have emerged.

First, to answer the credibility question we can use Schelling’s distinction between threats and commitments (1956). The deterrence message is a commitment if, entry having occurred, it is in the established firm’s self-interest to produce X , or if the production of X follows automatically. Otherwise the message is a threat and is not credible. To implement this approach we need a model of oligopoly. Given such a model, all interested parties can compute the post-entry equilibrium, providing a direct answer to the credibility question.

Second, by virtue of being there first, the established firm has the opportunity to make irreversible decisions which alter its real economic circumstances in any post-entry oligopoly game. These irreversible decisions can sometimes make the established firm a more aggressive competitor post-entry, and therefore serve to make the deterrence message more believable. That is, the established firm has the opportunity to do some things prior to entry which cannot be undone subsequent to entry, and which affect the profitability of entry. It is convenient to refer to these irreversible decisions as commitments. As Spence (1977) observed, since the rate at which output is produced is reversible, producing the limit output prior to entry is not a commitment and therefore has no bearing on the credibility of the deterrence message. However, holding the capacity or capital to do so is – provided that it is specific. By acquiring specific capital, the established firm reduces its marginal cost, making it more aggressive in any post-entry oligopoly game. Inventory (analysed by Ware 1985) is a particularly illuminating commitment since it puts the firm in the position of having zero marginal cost post-entry (until its inventory is exhausted).

The third insight, which arises from the attempt to implement the first two, concerns the form of the game which established firms and potential entrants play, and the appropriate equilibrium concept which this form seems to imply. Even in the simplest of circumstances, any game involving established firms and potential entrants is a multi-stage game played out in real time with two important features: (1) commitments, which inevitably involve sunk costs, are made in earlier stages of the game; (2) the net revenues which justify these sunk costs are generated only in later stages. As Brander and Spencer (1983) observe, this form is an unavoidable feature of economic reality. Product development costs, for example, must be sunk prior to production; the costs associated with specific capital goods must be sunk prior to production, and so on.

A rational firm must therefore think of commitments in the way it thinks of other investment decisions. In particular, it must form expectations about how decisions with respect to today’s commitments will alter its net revenues tomorrow, and thereafter. In the presence of sunk costs, rational or consistent expectations are a desirable feature of any equilibrium concept. If firms’ expectations are not constrained to be rational, then any outcome is possible – that is, given an outcome, there is a set of expectations which will produce it. Rational expectations are then necessary to constrain results. See, for example, the discussions in Eaton and Lipsey (1979, 1980) and Dixit (1980) on this point. Given this view, Selten’s (1975) notion of sub-game perfection is the appropriate equilibrium concept in these entry games.

To convey the flavour of modern theories of entry and to see how rational expectations enter the analysis, it is instructive to write down a simple entry game and to consider the way in which one finds the perfect equilibrium. Most of the recent literature on entry has focused on exercises which involve one established firm and one potential entrant, and which are not a great deal more complex than the following illustration.

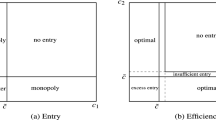

Consider an entry game played in three stages. In stage 1, firm 1 (the established firm) chooses the value of some commitment, c1. In stage 2, knowing the value of c1, which firm 1 chose in stage 1, firm 2 chooses a value for its commitment, c2. By appropriate choice of units, we can interpret c1 and c2 as costs, which once they are incurred are sunk. These sunk costs might, for example, be expenditures on advertising or on cost-reducing research and development. In stage 3, the two firms play a market game in which goods are produced and sold and the net revenues which justify the upstream sunk costs are realized.

To find the perfect equilibrium of this game we work backwards.

Given an oligopoly model which determines the equilibrium of the market game, the net revenue to each firm in stage 3 is determined by c1 and c2. Denote these net-revenue functions by ∏1(c1, c2) and ∏2(c1, c2) If, for example, the oligopoly model is the Cournot model, then in stage 3 each firm chooses its own quantity to maximize its revenues minus its avoidable costs. The net-revenue functions are simply revenues minus avoidable costs in the Cournot equilibrium.

FormalPara Stage 2If firm 2 is to have rational expectations, it must know ∏2(c1, c2). This, of course, means that it knows the oligopoly model which determines the equilibrium of the market game. In stage 2, knowing its net-revenue function and the value of c1, firm 2 chooses c2 to maximize [∏2(c1, c2)–c2]. The solution to this maximization problem determines c2 as a function of c1 : c2 = g(c1).

FormalPara Stage 1Rational expectations for firm 1 means that it knows both g(c1 ) and ∏1(c1, c2). In stage 1 it chooses c1 to maximize [∏1(c1, c2) – c2] subject to c2 = g(c1). The only endogenous variable in this maximization problem is c1 and the solution to it therefore determines a value for c1 say c*1. Firm 2 then chooses Π1 (c*1 , c*2 ), and in the third stage of the game the firms realize Π2 (c*1, c*2) and c* = g(c* ).

In this sort of game the established firm may or may not be able to deter entry, and if it is able, it may or may not choose to. Duopoly solutions will, however, be asymmetric. The established firm will rig the duopoly market structure to its own advantage.

Using this approach, or one that is in the spirit of this one, the recent literature on entry has focused on many of the commitments which established firms can and, indeed, must make. Advertising (Cubbin 1981), brand proliferation (Schmalensee 1978), the location of retail outlets (Eaton and Lipsey 1979), patenting (Gilbert and Newbery 1982), learning-by-doing (Spence 1981), the durability of specific capital (Eaton and Lipsey 1980), the exercise of monopsony power (Salop and Scheffman 1983) and, of course, specific capital (Spence 1977; Dixit 1980 and Ware 1984) are just some of the vehicles for commitment which have been considered.

This rich set of games and possible solutions brings us to the fourth insight in this literature. Implicit in this way of thinking about oligopolistic markets, and the role which entry plays in those markets, is much more than a theory of how one established firm strategically positions itself with respect to one potential entrant. There is, in this paradigm, a theory of market structure, a theory which remains largely unexplored.

Bibliography

Bain, J.S. 1956. Barriers to new competition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Brander, J.A., and B.J. Spencer. 1983. Strategic commitment with R&D: The symmetric case. Bell Journal of Economics 14(1): 225–235.

Cubbin, J. 1981. Advertising and the theory of entry barriers. Economica 48: 289–298.

Dixit, A. 1980. The role of investment in entry deterrence. Economic Journal 90: 95–106.

Eaton, B.C., and R.G. Lipsey. 1979. The theory of market preemption: The persistence of excess capacity and monopoly in growing spatial markets. Economica 46(182): 149–158.

Eaton, B.C., and R.G. Lipsey. 1980. Exit barriers are entry barriers: The durability of capital as a barrier to entry. Bell Journal of Economics 11(2): 721–729.

Gilbert, R.J., and D.M.G. Newbery. 1982. Preemptive patenting and the persistence of monopoly. American Economic Review 72(3): 514–526.

Modigliani, F. 1958. New developments on the oligopoly front. Journal of Political Economy 66: 215–232.

Salop, S.C., and D.T. Scheffman. 1983. Raising rivals’ costs. American Economic Review 73(2): 267–271.

Schelling, T.C. 1956. An essay on bargaining. American Economic Review 46: 281–306.

Schmalensee, R. 1978. Entry deterrence in the ready-to-eat breakfast cereals industry. Bell Journal of Economics 9(2): 305–327.

Selten, R. 1975. Re-examination of the prefectness concept for equilibrium points in extensive games. International Journal of Game Theory 4(1): 25–55.

Spence, A.M. 1977. Entry, capacity, investment and oligopolistic pricing. Bell Journal of Economics 8(2): 534–544.

Spence, A.M. 1981. The learning curve and competition. Bell Journal of Economics 12(1), Spring: 49–70.

Sylos-Labini, P. 1956. Oligopolio e progresso technico. Milan: Giuffre.

Ware, R. 1984. Sunk costs and strategic commitment: A proposed three-stage equilibrium. Economic Journal 94: 370–378.

Ware, R. 1985. Inventory holding as a strategic weapon to deter entry. Economica 52: 93–101.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Copyright information

© 2018 Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry

Eaton, B.C. (2018). Entry and Market Structure. In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_516

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_516

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-95188-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-349-95189-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences