Abstract

This article reviews recent research emphasizing the potential importance of public capital (or infrastructure) to aggregate economic performance, and provides a survey of empirical estimates of the productivity of public capital and of the impact of public capital investment on economic growth.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Cobb–Douglas functions

- Endogenous growth

- Long-term economic growth

- Neoclassical growth theory

- Output elasticity of public capital

- Productivity growth

- Public capital

- Public finance

- Returns to public capital

- Total factor productivity

JEL Classifications

Public capital (or often ‘infrastructure’) encompasses the publicly provided capital facilities which form the basis for private sector economic activity.

Empirically, public capital typically is defined as a net (of depreciation) stock of non-military structures and equipment and is often decomposed into core public capital (consisting of transportation facilities – such as streets and highways, mass transit, rail, and airports, water and sewer systems, and electrical and gas facilities), and other public capital (comprising educational structures, public hospitals, courthouses and the like).

The Productivity of Public Capital

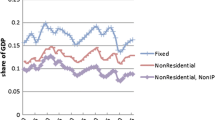

Beginning at the end of the 1980s, a significant research effort has focused on estimating the contribution of public capital to macroeconomic performance. The research initiative seems to have been the result of the recognition of certain facts about public capital expenditures in the United States. First, infrastructure capital accumulation, when expressed as a fraction of output, began to decline toward the end of the 1960s and, as a result, was seen as a potential factor in explaining the productivity growth slowdown of the 1970s and 1980s. Second, during the same period, the United States devoted a smaller share of output to infrastructure than did other industrialized economies (such as those in the Group of Seven), which was taken as possible force in explaining the relatively low rate of productivity growth in the United States vis-à-vis other countries such as Japan and Germany.

The first stage of the research effort centred on estimating the contribution of infrastructure to private sector productivity, where infrastructure is taken as another factor of production, along with private capital and labour, in an aggregate production function of the form

where Y denotes the aggregate level of economic output, A an index of total factor productivity, L, the labour force or employment, K private capital (usually restricted to business fixed capital), and KG the stock of public capital. The basic goal of the research was to ascertain the value of the output elasticity of public capital

in order to determine the ‘productivity of public capital’.

The early empirical results, typically employing level data in estimating a Cobb–Douglas production function, indicated (strikingly) high elasticity estimates, in the range of 0.25 to 0.50 for the United States and even higher for countries such as Canada and Sweden. These elasticity estimates, in turn, implied very high rates of return to public capital investments which some took as implausible. For example, Gramlich (1994) used Aschauer’s (1989) elasticity estimate of 0.39 to generate an estimate of the marginal productivity of public capital in the range of 0.70 to 1.00, which, in his view, was implausible since it implied that investments in government capital generate enough extra output to pay for themselves in a year.

Later, a number of researchers estimated the production function using first-differenced data, arguing that the initial results were ‘spurious’ because (a) variables such as output and public capital were first-order integrated series and (b) the production function did not serve as a cointegrating relation between output and the various factors of production (including public capital). These studies (for example, Tatom 1991) often generated much lower, and less reliable, estimates of the output elasticity of public capital.

Recently, Kamps (2004) has developed new estimates of public capital stocks for 22 OECD countries over the period 1960–2001, and has estimated the output elasticity of public capital. The point estimates are positive in 20 of 22 cases and statistically significant in 12 of 22 cases. A panel regression employing first-differenced data leads to a reasonable elasticity estimate equal to 0.22 which leads the author to conclude that public capital is productive on average in the countries comprising the OECD.

Public Capital and Economic Growth

The finding that public capital is productive is not, in and of itself, evidence that increasing public capital investment will raise long-term economic growth. There are at least three considerations which must be addressed. First, there is the question of whether a permanent increase in public investment will induce a permanent or transitory increase in growth. The traditional neoclassical growth model predicts that an increase in national savings and investment rates will have only a transitory effect on growth; more recent endogenous growth models, on the other hand, would predict permanent effects. Second, given the level of national savings, the effect of public investment on economic growth depends not just on a positive output elasticity of public capital, but on the relative marginal productivities of private and public capital; an increase in public investment at the expense of public investment will raise or lower the economic growth rate depending on whether the marginal product of public capital exceeds, or is exceeded by, the marginal product of private capital. Third, the effect of public capital on economic growth will depend on the method of public finance – whether by current taxes, debt, or (potentially) money creation.

One approach which allows tentative answers to all three questions is that of Aschauer (2000), who extends the Barro (1990) model of productive government spending to explicitly include public investment. This model, which assumes (a) that public investment is debt-financed and (b) a production function which displays constant returns to scale across private and public capital stocks (per worker) generates endogenous growth in per worker output at the rate

where y is the level of output per worker, (1/σ) the intertemporal elasticity of substitution, τ the tax rate necessary to service the public debt associated with public capital, and ρ a rate of time preference. Evidently, increases in the tax rate lower economic growth, while increases in the ratio of public capital to private capital raise economic growth. It turns out that increases in public capital will raise or lower economic growth depending on whether the tax rate is lower or higher than the output elasticity of public capital – that is, there is a nonlinear relationship between public capital and growth and an ‘optimal’ level of public capital. Using US state level data, Aschauer finds robust evidence that the relationship between public capital and growth is, indeed, nonlinear and that public capital is underprovided – that is, the ‘optimal’ ratio of public capital to private capital is in the range of 0.60 while the actual average ratio equals 0.44. As a consequence, a ten per cent increase in the public capital ratio is estimated to raise economic growth by approximately one percentage point per year.

Bibliography

Aschauer, D.A. 1989. Is public expenditure productive? Journal of Monetary Economics 23: 177–200.

Aschauer, D.A. 2000. Do states optimize? Public capital and economic growth. Annals of Regional Science 34: 343–364.

Barro, R.J. 1990. Government spending in a simple model of endogenous growth. Journal of Political Economy 98: 103–125.

Gramlich, E.M. 1994. Infrastructure investment: A review essay. Journal of Economic Literature 32: 1176–1196.

Kamps, C. 2004. New estimates of government net capital stocks for 22 OECD countries 1960–2001. Working paper 04/67, International Monetary Fund.

Tatom, J.A. 1991. Should government spending on capital goods be raised? Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 73(2): 3–15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Copyright information

© 2018 Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry

Aschauer, D.A. (2018). Public Capital. In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_2610

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_2610

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-95188-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-349-95189-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences