Abstract

In the past two decades a substantial international literature on the economics of the arts has accumulated. Aside from the importance of the cultural contribution made by the arts, interest in the subject among economists has been elicited by some special attributes of the economics of the arts which have proved interesting analytically and whose analysis has had significant applications outside the field. Notable is the ‘cost disease of the performing arts’ which has been proposed as an explanation for the fact that, except in periods of rapid inflation, the costs of artistic activities almost universally rise (cumulatively) faster than any index of the general price level. Another major theoretical issue with which the literature has concerned itself is the grounds on which public sector funding of the arts can be justified.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

In the past two decades a substantial international literature on the economics of the arts has accumulated. Aside from the importance of the cultural contribution made by the arts, interest in the subject among economists has been elicited by some special attributes of the economics of the arts which have proved interesting analytically and whose analysis has had significant applications outside the field. Notable is the ‘cost disease of the performing arts’ which has been proposed as an explanation for the fact that, except in periods of rapid inflation, the costs of artistic activities almost universally rise (cumulatively) faster than any index of the general price level. Another major theoretical issue with which the literature has concerned itself is the grounds on which public sector funding of the arts can be justified.

Organization and Funding

The structure of the performance industry is similar in many of the industrialized countries. The largest enterprise in terms of budget and personnel is the opera, followed, in rank order, by the orchestra, theatre and dance. The theatres are the only group that contains a substantial profit seeking sector. All of the others, and many of the theatres as well, receive a substantial share of their incomes from government support and private philanthropy. The US, with its policy of tax exemptions, is probably the only country in which the share of private philanthropy is large, and there it exceeds the amount of government funding by a large margin. In many countries the bulk of such financing is provided by only a single agency, while in the US an arts organization whose application has been rejected by one funding source can usually turn to others for reconsideration.

The available statistical evidence suggests that demand for attendance is fairly income elastic but quite price inelastic, at least in the long run. This suggests that the widely espoused goal of diversity in audiences prevents ticket prices from rising more than they have, although fear that such rises will cause temporary but substantial declines in revenues and will reduce philanthropic or government support no doubt also plays a part.

In every country in which systematic audience studies have been carried out, the audience has been shown to be drawn from a very narrow range. It is far better educated than the average of the population, it has a far higher average income, it is somewhat older, and it includes a remarkably small proportion of blue-collar workers. Even free or highly subsidized performances affect this only marginally.

While total expenditures on ticket purchases have, of course, risen over the years, the pattern is modified substantially when corrected for changes in population, the price level and real incomes. Thus, in the US, the share of per capita disposable income devoted to admissions to artistic performances declined from about $0.15 out of every $100 in 1929 to about $0.05 in 1982. The latter figure has been virtually unchanged throughout the period since World War II.

The Cost Disease of the Performing Arts

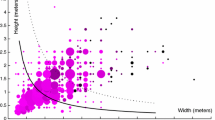

One of the special features of the economics of the performing arts that seems to colour their cost structure is their ‘cost disease’. This condemns the cost of live performance to rise at a rate persistently faster than that of a typical manufactured good. An illustration comparing the costs of watchmaking and of musical performance over the centuries shows the reason. There has been vast and continuing technical progress in watchmaking, but live performance benefits from no labour-saving innovations – it is still done the old-fashioned way. Toward the end of the 17th century a Swiss craftsman could produce about 12 watches per year. Three centuries later that same amount of labour produces over 1200 (non-quartz) watches. But a piece of music written three centuries ago by Purcell or Scarlatti takes exactly as many person hours to perform today as it did in 1685 and uses as much equipment.

These figures mean that while one has to work just about as many hours to pay for a ticket to an opera today as one would have in similar jobs 300 years ago, the cost of a watch or of any other manufactured good has plummeted, in terms of the labour time we must pay for it. In other words, because manufactured goods have benefited from technological advance year after year while live performances have not, almost every year theatre and concert tickets have become more and more expensive in comparison with the price of watches. This phenomenon has been called ‘the cost disease of live performance’.

To facilitate comparison with the discussion of the cost structure of the mass media that follows, it is helpful to describe the cost disease formally. Let

yit = output of product i in period t

xkit = quantity of input k used in producing i

ACit = average cost of i in period t

wkt = (real) price of k in period t

πit = yi/ ∑wktxkit = total factor productivity in output i

* = rate of growth, i.e. for any function, f(t)

f* = ·f/f.

Then we have:

Proposition 1

Let y1t and y2t be two outputs produced by single product firms. Then, if \( {\pi}_{1t}^{\ast}\le {r}_1<{r}_2\le {\pi}_{2t}^{\ast } \), so that output 1 may be called relatively ‘stagnant’ (and output 2 is relatively) ‘progressive’), the ratio of the average cost of output 1 to that of output 2, AC1t/AC2t will rise without limit.

Proof

By definition

so that

Here, of course, y1 may be interpreted as the output of live performance and y2 as the output of manufactured goods. It follows that the prices of manufactured goods can be expected to rise less quickly than those of concerts, dance or theatrical performances. Ticket prices must therefore rise faster than the economy’s overall rate of inflation, since the latter is an average of the increases in the prices of all the economy’s goods.

It is sometimes suggested that the mass media – film, radio, television and recording – can provide the cure for the cost disease, but recent analysis suggests that despite their sophisticated technology many of the mass media are in the long run vulnerable to essentially the same problem. As a matter of fact, the data indicate that the cost of cinema tickets and the cost per prime-time television hour have been rising at least as fast as the price of tickets to the commercial theatre. The explanation apparently lies in the structure of mass media production, which is made up of two basic components that are very different technologically. The first comprises preparation of material and the actual performance in front of the cameras, while the second is the transmission or filming.

Television broadcasting of new material requires these two elements in relatively fixed physical proportions – one hour of programming (with some flexibility in rehearsal time) must be accompanied by one hour of transmission for every one hour broadcast. However, since the first component of television is virtually identical with live performance on a theatre stage, there is just as little scope for technical change in the one as in the other, while the second component, on the other hand, is electronic and ‘high tech’ in character and constantly benefits from innovation.

Industries with this cost structure have been referred to as) ‘asymptotically stagnant’. The evolution of such an industry over time is characterized by an initial period of decline in total cost (in constant dollars) which must be followed by a period in which its costs begin to behave in a manner more and more similar to the live performing arts. The reason is that the cost of the highly technological component (transmission cost) will decline, or at least not rise as fast as the economy’s inflation rate. At the same time, the cost of programming increases at a rate surpassing the rate of inflation.

If each year transmission costs decrease and programming expenses increase because of the cost disease that besets all live performance, eventually programming cost must begin to dominate the overall budget. Thereafter, total cost and programming cost must move closer and closer together until virtually the entire budget becomes a victim of the disease, with the stable technological costs too small a fragment of the whole to make a discernible difference.

These results are encompassed in the following propositions:

Proposition 2

Suppose an activity, A, uses stagnant input x1 and progressive input x2 in fixed proportion v, so that x2t = vx1t. If w1t, the unit price of x1t, increases at a nonnegative rate no less than r1 and w2t increases at a rate no greater than r2, where r2 < r1, then the share of total expenditure by A that is devoted to x1t will approach the limit unity. Moreover, for any g such that 0 < g < 1, there exists T such that for all t > T

Proof

We are given

Then,

Along similar lines one can prove:

Proposition 3

Let A in Proposition 2 be supplied under conditions of perfect competition, and let its output, yt satisfy y1 = ux1t (u constant) and let its price be pt. The p* will approach that of the price of its stagnant input.

Corollary

The smaller the value of w2t, i.e. the more progressive is the progressive input of A, the more rapidly will the behaviour of A’s price approximate to that of its stagnant input.

Grounds for Public Support

Several economists have explored the grounds, if any, on which public support for the performing arts can be justified. They have examined all the usual criteria and found most of them weak. For example, income distribution concerns surely do not explain public financing of activities consumed largely by persons with incomes above the average. The beneficial externalities of attendance of the arts are not only difficult to document but are even hard to describe in the abstract. The same is true of the public good properties of performance. The best that has been done is to argue (1) that they have an ‘option value’ – even those who do not care to attend, themselves, may want to keep the arts alive for their grandchildren; and (2) that they constitute a partially public good through their part in the educational process and the (national) pride they engender even in those who do not attend themselves (or the embarrassment they avoid among those who do not want to belong to a nation of philistines). In the last analysis, it is simply argued that the arts deserve support because they are) ‘merit goods’ (to use Musgrave’s term). But that amounts to substitution of nomenclature for analysis. What the discussion comes down to is that the evidence suggests strongly that the public considers the arts worth supporting, and that in a democracy the public has the right to support what it wants to. Welfare theory has little to contribute here.

The cost disease analysis has been used by administrators throughout the world as justification for support but, of course, the fact that an activity is under financial pressure is, by itself, no valid reason for public subvention, as economic theory shows so clearly. However, if support is decided upon on other grounds, the cost disease analysis does legitimately help to give guidance on the amounts it will be appropriate to provide. It also warns us of the dangers of underfinancing as a result of what W.E. Oates has called ‘fiscal illusion’. The cost disease implies that the cost of performance will rise faster than the general price level. If so, when government support for the arts increases only marginally faster than the general price level, politicians are likely to conclude that, though they have increased the real level of support, the quantity and quality of activity the public is getting for its money is declining. Mismanagement and waste are then likely to be blamed and budgets may be trimmed, on those grounds, below the level that is called for by the public’s actual preferences.

Bibliography

Baumol, H., and W.J. Baumol (eds.). 1984. Inflation and the performing arts. New York: New York University Press.

Baumol, W.J., and W.G. Bowen. 1966. Performing arts: The economic dilemma. New York: Twentieth Century Fund.

Blaug, M. (ed.). 1976. The economics of the arts. London: Martin Robertson.

Feld, A.L., M. O’Hare, and J.M.D. Schuster. 1983. Patrons despite themselves: Taxpayers and arts policy. New York: New York University Press.

Netzer, D. 1978. The subsidized muse. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Throsby, C.D., and G.A. Withers. 1979. The economics of the performing arts. New York: St Martin’s Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Copyright information

© 2018 Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry

Baumol, W.J. (2018). Performing Arts. In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_1706

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_1706

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-95188-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-349-95189-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences